II. ESTABLISHMENT OF A HOMOGENEOUS BYZANTINE SOCIETY

A. HERACLIANS AND ISAURIANS

1. Retrenchment

Justinian had accomplished his spectacular reconquest of the west at a very high price: the neglect of the Balkan and Asiatic provinces.

The most remarkable example of this was the Syrian campaign of the Persian monarch Chosroes who, in 540, sacked the great metropolis of Antioch. This neglect, compounded by the financial exhaustion ensuing from Justinian’s grandiose projects, was to bear bitter fruit in the seventh century. Furthermore, the centralizing forces so manifest in the artistic, legal, religious and political programme of Justinian failed to overcome the centrifugal tendencies in the west and above all in the east. The process by which the east disengaged itself from Byzantine Hellenism in the sixth and seventh centuries put the finishing touches to a development which had moved fitfully for a millennium.

It is ironic that the religious differences which became the focal points of strife between Constantinople and the non-Greek eastern provinces ultimately derived from the position of the theological schools of Antioch and Alexandria, both of which schools represented Greek metaphysical traditions. In spite of the condemnation of Monophysitism at Chalcedon (451), the succession of two Monophysite emperors (Zeno and Anastasius I) and the passivity of Justin I provided several decades of conditions favourable to the spread of Monophysitism in Egypt and Syria. Justinian was thus faced with a body of strongly-rooted sectaries and his task of bringing the Monophysites into the Church was further complicated by his need to placate the papacy and by Theodora’s unashamed patronage of the Monophysite clergy. Accordingly, there is an extraordinary range

57

![]()

and diversity in Justinian’s theological actions. He was, variously, a supporter of the decisions of the council of Chalcedon, a Theopaschite, and a Monophysite of the Aphthartodocetist persuasion, as he tried vainly to please one and all.

Monophysitism had the advantage of two very capable leaders in the sixth century who gave the sect articulate form: Severus who formulated Monophysite theology, and Jacob Baradaeus who erected the ecclesiastical structure of the Monophysite Church. In a period when the Chalcedonians occupied many of the bishoprics Jacob ordained Monophysite bishops for the same episcopal sees; and though they were unable to take over the sees to which they were appointed, he thereby created the skeleton of a Monophysite hierarchy which could, under more propitious circumstances, replace the Chalcedonian clergy. The emergence of Monophysitism gave further impetus to the development of Coptic and Syriac as liturgical and literary languages so that by the early seventh century the conflict brewing between Chalcedonian Greeks and EgyptianSyrian Monophysites was ethnic as well as religious.

The succession of the incompetent and brutal Phocas (602-10) marked the low point of the decline which followedjustinian’s death. An almost complete military collapse in the east and the Balkans, bloody repression of the eastern sectaries, and the suicidal strife of the Blues and Greens in the cities were rapidly debilitating and consuming the empire. The papacy alone rejoiced in the rule of the bloodthirsty Phocas. This was Phocas’ reward for taking the side of Pope Gregory I who had earlier protested against the assumption by the patriarch of Constantinople of the title oecumenical patriarch. However, the ease with which Heraclius, son of the Armenian exarch of North Africa, put an end to the reign of Phocas indicates that the Byzantines were sickened by him.

When Heraclius arrived in Constantinople the empire’s position appeared beyond redemption, for the Avars, with their Slav and Bulgar subjects, were overrunning the Balkans, and the Persians were advancing through the eastern provinces, until in 615 they had actually occupied Egypt, Syria, and Palestine. The Persians subjected Jerusalem to massacre and fire, carrying off to Ctesiphon the Holy Cross and the patriarch;

58

![]()

and in Egypt a Coptic governor now ruled the land under the aegis of Persia. With the encampment of the Persian armies under Shahen on the Bosphorus, Heraclius was virtually cut off from the principal sources of manpower and revenues in the greater part of the Balkans and the Near East. But C Constantinople, protected by God, the Virgin, and its impregnable mural and maritime defences, remained inviolate. So long as the enemy could not capture this nerve centre, the empire possessed in Constantinople a remarkable vehicle of regeneration. The wisdom of Constantine the Great in choosing this site for his capital was to be proved many times in the history of Byzantium.

Heraclius, however, found the situation so hopeless that he decided to abandon Constantinople for Carthage where his family enjoyed prestige and where eight decades of Byzantine rule had restored economic prosperity. But accident intervened. The ship which had been loaded with the palace treasures sank in a storm, and the patriarch Sergius bound the emperor by oath not to abandon the capital and offered the treasures of the Church to the state. Heraclius now concentrated on building up his military strength, postponing any move against the Persians until the day after Easter in 622 when lie sailed from Constantinople to Issus and there began a series of gruelling campaigns that were to last until 628.

38, 39, 40 Imperial portraits: gold solidus of Phocas (probably issued in 603); solidus of Heraclius (between 613 and 629), shown with his son, afterwards Constantine III; and a later solidus of Heraclius (between 629 and 631), now with a heavy beard and moustache, and grown-up son

59

![]()

This Perso-Byzantine war, accompanied by feverish religious passions and hatreds, is perhaps the first full-fledged crusade of the Middle Ages. The poet-chronicler, George of Pisidia, casts the emperor in the rôle of pious fighter for the faith as he describes how, on the eve of the first encounter between Heraclius and the Persian Shahr Barz in the Anti-Taurus,

Cymbals and all kinds of music gratified the ears of Shahr Barz and naked women danced before him, while the Christian emperor sought delight in psalms sung to mystical instruments, which awoke a divine echo in his soul.

In 623, while campaigning in Azerbaijan, the Byzantine troops systematically destroyed the fire temples of the Persians in city after city. In particular they destroyed Thebarmes, supposed birthplace of Zoroaster, in revenge for the Persian desecration of Jerusalem.

The great crisis came when the Avars laid siege to Constantinople in 626. Chosroes sent Shahr Barz with a new army to co-operate with the Avars in besieging the capital, and ordered Shahen (under pain of death) to hunt down Heraclius in the east. The emperor, refusing to abandon Anatolia and the gains he had made in four years of campaigning, set out for Azerbaijan where he received assistance from the Khazar khan. Meanwhile the siege of Constantinople was pushed forward throughout the month of July, at the end of which time the Avar khan arrived; but his great assault on the land walls was repulsed, it is said by a miraculous icon of the Virgin. All further efforts by both Avars and Persians failed before the spirited defenders (Constantinople was defended by only about 12,000 men) and finally the siege was abandoned. The composition of the famous Akathistos hymn (still sung in Orthodox churches during the Easter season) is traditionally associated with the patriarch Sergius and this successful defence of the city.

The end came in 627 when Heraclius inflicted a decisive defeat on the Persian forces in the region between Nineveh and Gaugamela where a thousand years earlier Alexander had destroyed the Achemenid empire.

60

![]()

41 The emperor Heraclius (610-41), son of the governor of North Africa, who replaced the incompetent and brutal Phocas. He saved Byzantium from the Persians, only to see the Arabs sweep away his Middle Eastern and North African possessions

In 628 the Sassanids, their power broken, sued for peace and relinquished all their conquests. Heraclius returned to Constantinople where he was received by the patriarch Sergius and the Holy Cross, recently recaptured, was raised in a joyous ceremony. A year later the emperor, accompanied by his family, journeyed to Jerusalem where he restored the Cross. Heraclius must have looked back to the year 622 as the turning-point not only in his personal fortune but in that of the empire. He could not know that this same date marked the reversal of fortune in the life of another man, a Semite of Arabia, who also abandoned his own city of Mecca, to go forth to a battle for dominion over men’s souls and minds.

61

![]()

The restoration of Byzantine power in the east was temporary and Heraclius himself saw the beginning of its collapse. The immense exertion which had led to his spectacular victory over the Sassanids simultaneously depleted the empire and contributed further to the weakness arising from sectarian and cultural pluralism. Heraclius and his successors made continued attempts to compromise with the Monophysites in a desperate effort to maintain some kind of internal cohesion in the critical areas. From 626 onward Sergius and Heraclius appealed to the Armenians and Syrians by enunciating the doctrine that, though Christ was both human and divine, He was possessed of only one energy. When this doctrine met with opposition from Chalcedonians the patriarch and emperor shifted their ground and declared in the Ecthesis (638) that Christ had one will (Monothelitism). But the results were no more satisfactory. As late as 648 the emperor Constans II attempted to hold the conflicting parties together by forbidding discussions of energies or wills in his Typicon, but again to no avail. When, in 680-81, the sixth ecumenical council condemned Monophysitism and Monothelitism and asserted two wills and two energies without division, alteration, separation, or confusion, Monophysitism was no longer a political problem. The Arabs, in conquering Egypt, Syria, Palestine and Armenia, had removed the Monophysites from the empire and relegated the question to the realm of academic theology. So long as the emperors had hopes of saving the eastern provinces they tried to satisfy the Monophysites; now it was no longer necessary.

2. The threat of Islam

The Arab conquests of the seventh century, which so altered the historical development of Europe and the Middle East, are as inexplicable and startling to us today as they were to the Byzantines. The new religion which the prophet Muhammed preached transformed much of Arabian society by providing it with religious bonds of unity and an élan vital which had previously been lacking. The Arabs had also acquired considerable knowledge of the outside world, whether as mercenaries of the Byzantines and Persians or as merchants in the carrying trade between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean.

62

![]()

When the Arabs finally spilled out of the Arabian peninsula they found the Byzantines not yet recovered from the Persian struggle and suffering from the internal convulsions of religious discord. The Persians, defeated by the Byzantines, had in addition suffered from a fossilized social structure that resulted in the jacquerie and communism of the Mazdakites.

Soon after the death of Muhammed (632) the Arabs began to raid the regions of both empires immediately to the north. Their attacks on Byzantine territory culminated in the battle of the Yarmuk (636), a crushing defeat for the Byzantines, which settled the fate of Syria and Palestine, though the Hellenic centres of Jerusalem and Caesarea did not fall until 638 and 640. The Chalcedonian patriarch of Jerusalem, Sophronius, received the caliph Umar in Jerusalem and served as his guide to the principal holy sites. The most uncompromising opponent of Heraclius’ attempt to placate the Monophysites with Monothelitism, Sophronius reaped the rewards of his obstinacy when he witnessed Umar reverently kneeling in the precinct of the Church of the Resurrection. This sight moved Sophronius to remark: ‘The abomination of the desolation which was spoken of by Daniel the prophet is in the holy place.’ In 637 the Arab armies defeated the Persians at Kadesiya, in 640 Amr ibn al-As invaded Egypt and one year later the acquisition of Syria, Palestine and Iraq was completed by the conquest of Mesopotamia. In less than a decade a little-known people had with ease terminated a millennium of Graeco-Roman rule in the Near East and had settled the fate of the Sassanid state.

The critical phase of the struggle between Byzantium and the new Islamic giant took place in the reign of Constantine IV (668-85), when the ambitious caliph Muawiyya set out to take Constantinople.

He sent his armies repeatedly into Asia Minor and, in a phenomenal display of adaptation, created an Arab naval power which soon occupied Cyprus, Rhodes, Chios and Cyzicus. His forces first besieged Constantinople in 669, but the major effort of the Arabs came in the five-year period 674-78. The Arab fleet based at Cyzicus and the armies which marched across Anatolia tried to storm the powerful bastion, but in vain, and both the Arab fleet and army suffered a humiliating disaster in which the dreaded Greek fire invented by a Greek from Syria made its debut.

63

![]()

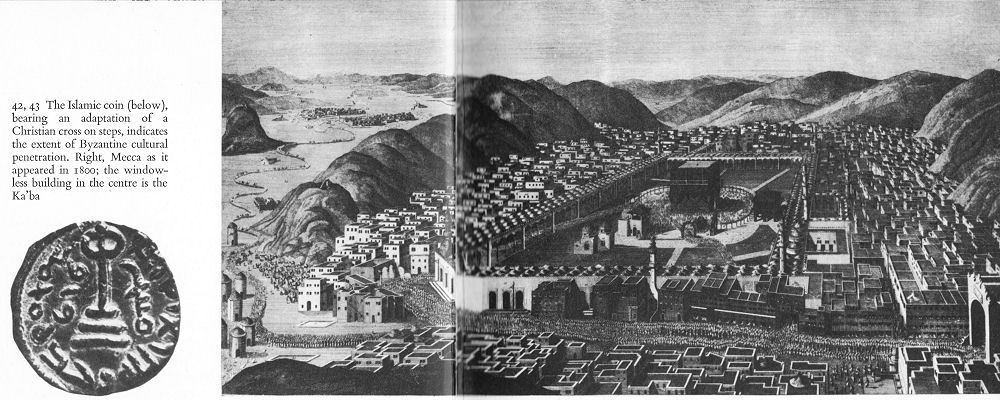

42, 43 The Islamic coin (below), bearing an adaptation of a Christian cross on steps, indicates the extent of Byzantine cultural penetration. Right, Mecca as it appeared in 1800; the windowless building in the centre is the Ka’ba

Constantine IV had providentially equipped his fleet with siphons for propelling the secret weapon, and Greek fire became one of the most dreaded weapons of the imperial fleets. This Byzantine victory was crucial for the history of both Christendom and Islam, far more so than the victory of Charles Martel at Poitiers (732). The empire was able to overcome the greatest military effort of Islam and thus to preserve the Christian character of European civilization. The defeat of Muawiyya turned the Arab power back to the Middle East whence it had come, and though the Arabs succeeded in taking Spain, Islamic civilization was eventually confined to non-European areas.

In contrast to Syria, Palestine and Egypt where the Arabs had found a predominantly Monophysite and non-Greek population, Anatolia and the European provinces represented a predominantly

64

![]()

Greek-speaking Orthodox population. Consequently when the rapid advance of the Arabs halted on the borders of Anatolia and at the maritime borders of the Mediterranean islands, the geographic, political and ethnic boundaries coincided. Asia Minor remained an integral part of the empire, intimately involved in the annual raids and counter-raids of the two sides, while the Arab maritime advance halted with the conquest of Crete and Sicily in the ninth century.

The emergence of Islamic power, monopolizing Byzantine military efforts, was the ultimate cause for Byzantium’s loss of the west. In this sense the Arab invasion did result in the disruption of the unity in the old Mediterranean world. When the Arabs occupied the Byzantine territories, however, they adopted the urban civilization of Damascus and Antioch, of Jerusalem and Alexandria, so that Byzantine social, economic and cultural institutions continued after the conquest. But in the political realm there was a sharp break

65

![]()

between the Islamic and Christian portions of the Mediterranean. Furthermore, it was the Arab invasions which led the papacy to turn its back on Constantinople and to face northwest Europe, thus beginning the policy which led to the alienation of east and west.

3. The new Western empire

Less than half a century after Narses had re-established Byzantine rule in Italy, the Lombards conquered most of the peninsula. Although the emperors did not neglect Italy (Constans II even made an expedition to Italy in 663 in an effort to expel the conquerors) their life-and-death struggle with the Arabs and Bulgars made it virtually impossible for them to check the Lombards. Differences between the Churches of Constantinople and Rome appeared early because of the swift rise of the former as the most important of the eastern patriarchal seats, and by the eighth century the Iconoclastic controversy exacerbated relations. Nevertheless, the popes relied upon the emperors for protection against the troublesome Lombards. But the fall in 751 of Ravenna, the centre of the Byzantine exarchate in central Italy, and the inability of Constantine V to halt the Lombards because of his intensive military campaigns against the Bulgars and the Arabs, isolated the papacy. The result was that three years later Pope Stephen II journeyed beyond the Alps to meet the Frankish ruler Pepin - a step which started the famous partnership between the Carolingians and the papacy and culminated in Charlemagne’s coronation by the pope in Rome on 25 December 800.

44 Constantine V ‘Copronymous’ (741-75), under whom the persecution of icon-worshippers reached its height

66

![]()

45 Irene, widow of Leo III, was the only woman who ruled the empire on her own (797-802). She did little to enhance its power or prosperity, but re-introduced for a time the worship of icons

This act deeply disturbed the Byzantines because it violated the principle of one empire, and they attempted to oppose Charles’ usurpation. But in the hostilities which ensued Constantinople was forced to concede to Charlemagne the title of Basileus in 812. There was now an empire of the east and one of the west as well, and the Byzantine monopoly was broken. The emergence of the western empire is the most spectacular moment in the rise of a new society in western Europe. Just as the genius of Justinian had marked the emergence of Byzantine civilization in the sixth century, so the figure of Charlemagne helped to mould the civilization of western

67

![]()

Europe which began to take shape in his time. As the centuries passed the two societies grew apart in political, social, economic, cultural and spiritual life and their separate development is the basis of the difference between western and eastern Europe in modern times. By causing the papacy to seek out the Carolingians the Arab successes in the east played an important rôle in laying the foundation of western European culture. It was also other peoples of the east, the Mongols and the Turks, who at a later period effectively isolated the peoples of Byzantine culture from the culture of the west, and so sharpened the differences which are so apparent in the history of Europe during early modern times. Thus the impact of the Orient, Islamic and Altaic, has been one of the decisive factors in the whole development of east and west in Europe.

4. Disorder in the Balkans

In the Balkan regions Justinian’s neglect coincided with the mounting demographic pressure of new peoples. The lands to the south of the Danube, areas of pillage and raiding since the fourth century, had been occupied by Visigoths, Ostrogoths, Huns, Gepids, and Heruli, who had desolated the northern half of the peninsula, so that by the sixth century when the Slavs and Bulgars settled there they effected a major ethnographic change. The Slav and Bulgarian tribes which had made their way to the Danubian shores early in the sixth century took advantage of Justinian’s pre-occupation with the west to cross the borders and to raid imperial territory almost unopposed. The Bulgars invaded the Balkan peninsula in 540, ravaged Thrace, Macedonia, Illyricum, and pressed south as far as Corinth. The Sklavenoi similarly invaded Illyricum in 548, their raid culminating in the sack of Dyrrachium on the Adriatic. Their failure before the walls of Thessalonica two years later was the first in a long series of attempts by both Slavs and Bulgars to break out into the Aegean, and the loss of the city would have entailed serious consequences for Byzantine control in the Greek peninsula. The pressure of the barbarians over the years was such that the Thessalonicans attributed their salvation to the miraculous intervention of St Demetrius, their patron saint.

68

![]()

The Altaic people known as Kotrigurs invaded the Byzantine districts in 559, reaching Thermopylae in central Greece and the environs of Constantinople in the east. Justinian himself and the populace of the capital were panic-stricken, for there were no armies with which to defend the city. Fortunately Belisarius, who had been disgraced by the jealous emperor, hastily gathered a group ofpeasants and horses and succeeded in terrifying and driving off the Kotrigurs.

Thus, for the greater part of Justinian’s reign the Balkans were the scene of activity of various Slavic and Altaic tribes which raided the land sporadically without any overall supervision or direction. The appearance of the Avars on the Danube in 561 altered the situation radically. The Avars, like their predecessors the Huns, were an Altaic people who had abandoned the Asiatic steppe under the pressure of the newly-formed Oguz empire. Desiring lands in the empire and having beeri, refused by Justinian, the newcomers set out to take them by force. Much as the Huns had made military vassals of the Germans, so the Avars subjugated the Slavs and Bulgars and utilized their manpower in the conflict with Byzantium. The emperor Maurice temporarily halted the threat when for the last time he re-established the Danube as the imperial boundary in 599-600. But the rebellion of the army at the prospect of lengthy campaigns in the inclement Balkans followed by the chaotic rule of Phocas (602-10) decided the fate of the northern and central Balkans. The barbarians poured into the peninsula, destroyed Byzantine authority and began to settle on the land in great numbers. With the capture of the principal urban centres in the north, the newcomers destroyed the focal points of the Church and the administration in provinces which had previously suffered depopulation. Thus the invasions not only resulted in a drastic ethnographic transformation, but also obliterated Christianity and Byzantine civilization. Two and a half centuries were to elapse before the elements of Byzantine culture could again be introduced in the area now occupied by the Slavs and Bulgars.

Though the Avars succeeded in occupying much of the Balkans and even in taking the towns of the north, the walled urban centres of Thrace and Greece proved to be the final obstacle to their success.

69

![]()

Nevertheless, with their Slav and Bulgar auxiliaries they seriously threatened Thessalonica and Constantinople in the early seventh century and once more the fate of Byzantine civilization hung in the balance. Thessalonica, in particular, was exposed to the invading hordes because of its strategic location midway between Constantinople and southern Greece. The plight of the empire is dramatically recounted in the miracula of St Demetrius, the city’s patron saint:

Under the episcopate of John the people of Sklavenoi arose, an immense people composed of Drogouvites, Sagoudates, Velegazites, Vaiounites, Verzites, and other peoples. Having made and armed ships of a single tree trunk, they ravaged all Thessaly, the neighbouring isles and the isles of Helladicon, the Cyclades, all Achaea, Epirus, the majority of Illyricum and part of Asia, leaving behind them all of the cities and eparchies as deserts.

At this time, also, the Avars and their followers made a great effort to reduce Thessalonica in a siege which endured for thirtythree days. Thanks to the energies of its archbishop and also to the strength of the city walls, the city, flooded with refugees who had managed to flee from various parts of the Balkans, survived the attacks.

With their failure before Thessalonica and their even more dramatic defeat before the walls of Constantinople in 626, the Avar threat disappeared. The Bulgars and Slavs shortly escaped from Avar tutelage and the Bulgarian khan Kubrat established the Bulgars in the regions of the northern Vardar. During this period the rearguard of the Slav invaders, the Croats and Serbs, also entered the Balkans. Their settlements were of course densest in the northern Balkans, but Slavs settled extensively in parts of Greece as well. It was the less numerous Bulgars, however, who became the most powerful group politically. Constantine IV suffered a military defeat at their hands in 680, and was forced to cede the lands north of Mount Haemus to the khan Asperuch, though the empire enjoyed a respite during the reign of Constantine V who crushed the Bulgars

70

![]()

in repeated campaigning. But the recklessness of Nicephorus I, which led to his death and the defeat of his army in the mountainous passes of northern Bulgaria, enabled the Bulgarian ruler Krum to establish the Bulgarian state on firm foundations.

The centuries of barbarian invasions and the disastrous policy of Justinian and of some of his successors produced a completely new ethnographic and political pattern in the Balkans. The ninth-century map of the Balkans indicates how complete this change was. There were Croats in the west, Narentines in Dalmatia, Serbs and Bulgars in the north and east, and finally numerous Slavs who had settled in Greece where, however, they were eventually absorbed by the indigenous population.

5. Administrative change

The pressure to which the repeated blows of the barbarian peoples subjected Byzantium not only resulted in great losses but also stimulated great internal change and readjustment. This internal evolution indicates that even though Byzantine statecraft never conceived the possibility of altering the framework of autocracy, it was nevertheless capable of great institutional adaptability and resilience. For centuries the administration had been based on Diocletian’s separation of civil and military authority, and this arrangement had given the empire respite from rebellion. But the new situation, in which external forces threatened Byzantium with destruction, demanded effective military action. The separation of civil and military power, because of the paralysis of action which it entailed, had to be abandoned. The invasion of the Lombards and the incessant raids of the Berbers had prompted the emperor Maurice to reunite political and military authority in each area in the hands of one individual, the exarch of Ravenna and the exarch of Carthage. Thus began the militarization of the provincial administration, a process which was to lead to extensive social change as well. The process was carried further when, at the time of the Persian invasions of the early seventh century, Heraclius decided to militarize the administration in those Anatolian districts which were still controlled by the empire. As a result the strategos (general)

71

![]()

of a theme (province) became the supreme official in both the military and civil life of his theme. Furthermore, the creation of a theme entailed the settlement of troops in that particular province, who were supported by gifts of land. Henceforward the performance of military duty by the soldiers of the themes and their enjoyment of their freehold lands became inseparable.

The Arab conquests and the invasions of the Slavs and Bulgars led to a further development and extension of the thematic system, and eventually the militarization of provincial government came to comprehend the whole of the empire. Because of the loss of the major part of the Balkans, the themes of Anatolia became the principal recruiting ground of the Byzantine army, which they remained for the next four centuries. There is no doubt that the new administrative establishment was of great benefit to the empire for it actually created a new peasant army. The peasant soldiery, with its small landholdings from which it derived the wherewithal to equip itself, provided each province with an indigenous army ready at all times to meet the foe. The appearance of this new ‘national’ army was matched by a corresponding decline in the prominence of the foreign mercenaries who had been so conspicuous an element in the Byzantine armies during preceding centuries. The loyalty of the latter had never gone far beyond their pay, whereas that of the new peasant-soldier derived from emotional as well as economic sources. Furthermore, the elevation of a section of the peasantry into a military class, together with government support of the peasant as a free landowner and thereby a strengthening of the peasant class as a whole, helped greatly to revitalize the empire’s social structure. For in the centuries that followed, the emperors were able to restrict the power of the great landed magnates by supporting and utilizing the peasantry. The amelioration of the conditions of the peasant class was also a great boon to the imperial fisc as the peasants assumed a considerable portion of the tax burden.

6. Iconoclasm

If the invasions of Arabs, Slavs, and Lombards constituted a crisis for the body of the empire, the Iconoclastic controversy may be described as a crisis of the empire’s soul.

72

![]()

46 The Bulgars’ invasion of Byzantine territory; illustrations in a twelfth-century Slavonic manuscript. In the lower half, Krum, king of the Bulgars, is taunting the captured emperor Nicephorus I

73

![]()

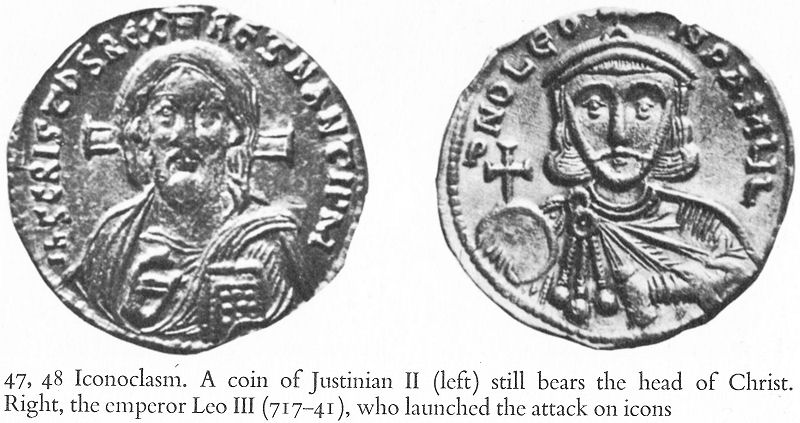

47, 48 Iconoclasm. A coin of Justinian II (left) still bears the head of Christ. Right, the emperor Leo III (717-41), who launched the attack on icons

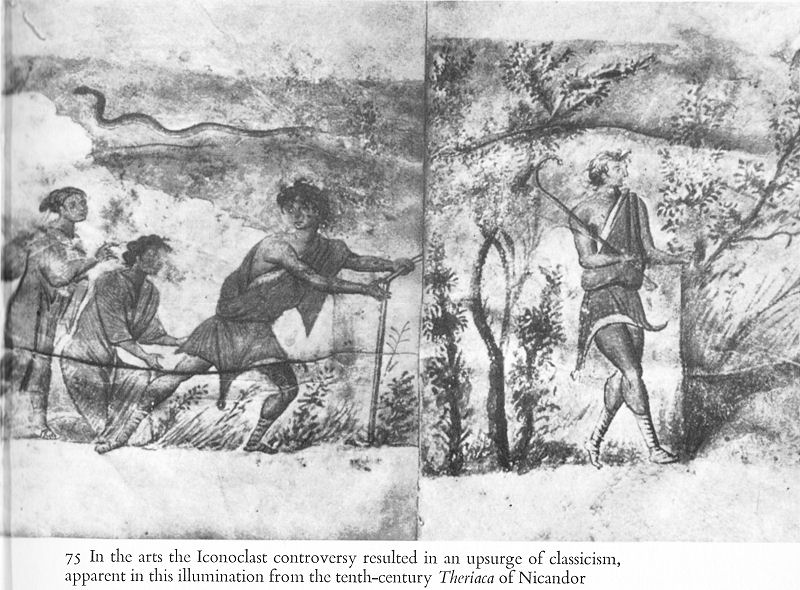

The quarrel over the admissibility of images in religious art erupted in the eighth century. By the time when Leo III began to attack the use of images as idolatrous, the importance of icons in Byzantine piety and art quite paralleled the Graeco-Roman reverence for and attachment to religious statues. The struggle between the Iconoclasts and the defenders of the icons became so vicious that it consumed society for more than a century. The Church’s admission of the image in religious art during the third and fourth centuries was of momentous importance, for had the Church not done so the Graeco-Roman artistic traditions would have largely expired and European art would possibly have taken a course similar to that of Islamic art. But in spite of the Church’s acceptance of these traditions there appeared early a voice in the Church which condemned images because they were related to pagan practice, and because their use contravened the Mosaic prohibition of the graven image. Nevertheless, an intensification of the cult of icons was discernible in the latter half of the sixth century when the disintegration of political affairs induced men to hope for miracles, magic and superhuman intervention. As the older tendency of the Greek and Hellenized populations to associate magical powers with physical images reasserted itself, the leaders of society did nothing to suppress it. Rather they 74 promoted this development by such official acts as canon 82 of the

74

![]()

council of 692 (which ordained that henceforth Christ might no longer be represented as a lamb but only as a human) and the placing of Christ’s image on the coins minted under Justinian II.

The reaction against the use of icons came to a head in 726 when Leo III (a Syrian by origin), at the urging of certain bishops and after a volcanic eruption which he thought to be the result of God’s anger, forbade their use as idolatrous. Their removal and destruction provoked a violent reaction against Leo in many quarters. The empire and papacy severed relations, the theme of Hellas revolted, and a cleric safely domiciled in the distant lands of the caliphate wrote a series of theological tracts defending the images. John of I Damascus established the basic theological position of Orthodoxy in supporting the icons and successfully defended their use against the charges of idolatry.

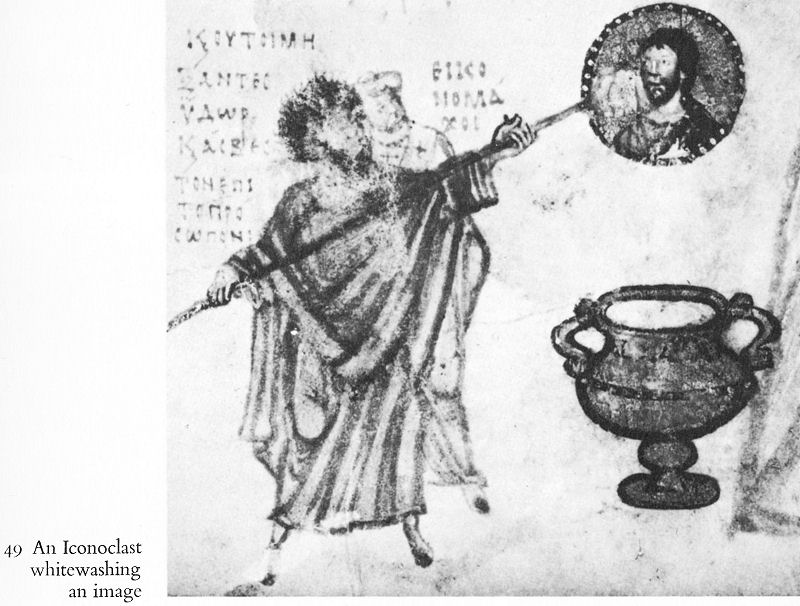

49 An Iconoclast whitewashing an image

75

![]()

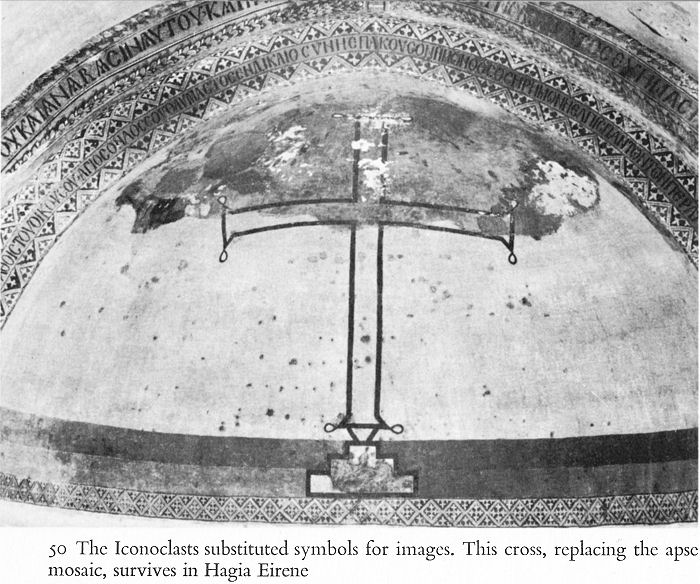

50 The Iconoclasts substituted symbols for images. This cross, replacing the apse mosaic, survives in Hagia Eirene

It was the Incarnation, he reasoned, which justified the making of images, for thus one can depict the human aspect of Christ. Further, the use of images could not be condemned on the grounds that pagans had also used physical likenesses of their gods, for on the same grounds one would have to condemn Christian exorcism and other practices. Finally, the icon was a record of past events, an imitation (just as man was made in the image of God), and was related to its prototype in a neoplatonic manner. The proper attitude of the beholder of the icon was respect and not, as the Iconoclasts had charged, worship.

The programme of the Iconoclasts attained its greatest successes under the vigorous son of Leo. Constantine, slanderously nicknamed Copronymous (Dung-name) by his outraged opponents, carried the attack to the heart of resistance by waging open warfare on the monastic establishments. He confiscated their properties, martyred some of the monks, drafted others into the army, and forced many to marry nuns. On the theological plane he shifted the Iconoclastic

76

![]()

arguments from the charge of idolatry and entered the realm of Christological controversy at the council of Hieria in 754. All who painted or worshipped images were either Nestorians or Monophysites because the human and divine natures of Christ were inseparably united. Anyone who believed he could depict the human Christ was a Nestorian; if he believed that it was the divinity, he was not only a Monophysite but had also violated the uncircumscribability of God. Constantine’s own theology was, however, slightly Monophysitic for he tied Christ’s humanity so closely to His divinity that He could not be pictorially depicted. The basic positions of both sides were thus formed by the middle of the eighth century, but the conflict continued after the reign of Constantine in a less acerbated form. The seventh ecumenical council of Nicaea restored the icons temporarily in 787, but their final restoration took place only in 843. The controversy, though of Christological significance, was of broader importance because, in assuring the continuity of the Graeco-Roman tradition in Byzantine art, the Hellenic spirit triumphed over this Judaic concept which would have given Byzantine society a more Oriental coloration. Byzantium thus withstood both Oriental military and intellectual advances.

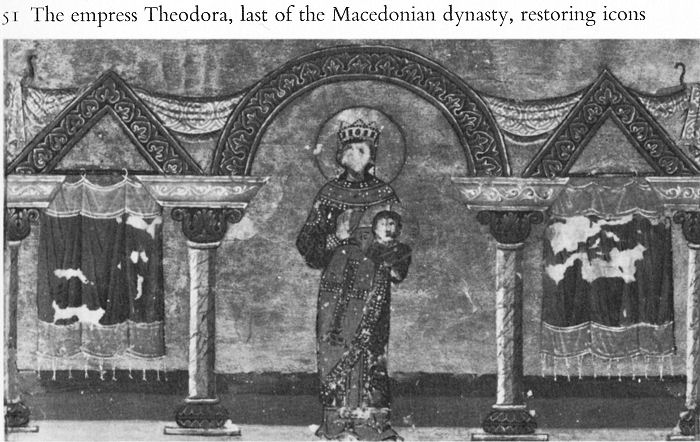

51 The empress Theodora, last of the Macedonian dynasty, restoring icons

77

![]()

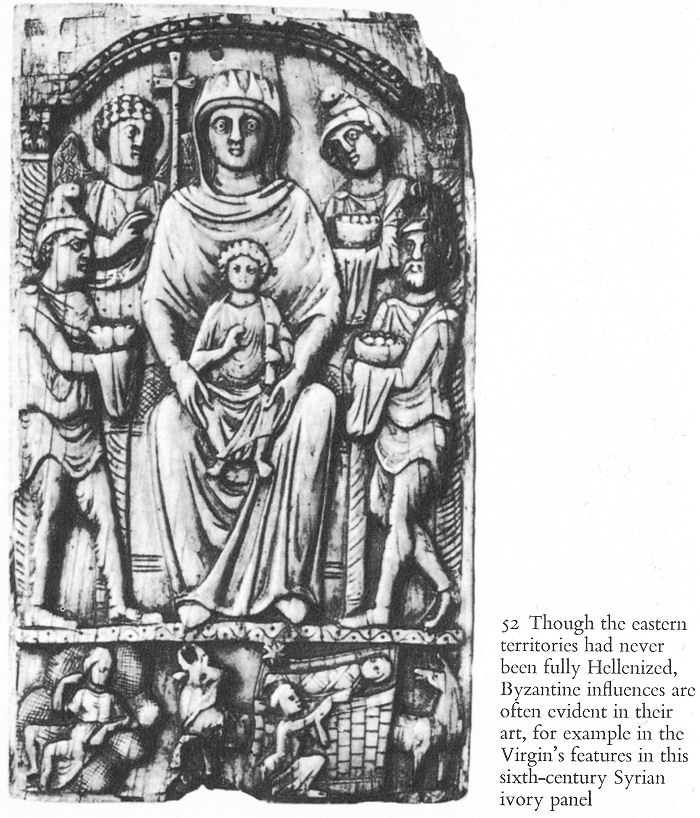

52 Though the eastern territories had never been fully Hellenized, Byzantine influences are often evident in their art, for example in the Virgin’s features in this sixth-century Syrian ivory panel

7. Cultural changes

The seventh century was, in many ways, the ‘Dark Age’ of Byzantium, for aside from the great losses which the empire suffered, there is also a void in contemporary literary remains. The Arab conquests had resulted in the loss of the Near East and North Africa, while the Slavs and Bulgars had occupied most of the Balkans. These tremendous losses had deprived the Byzantines of the important Balkan and Armenian military recruiting grounds, as well as the fruits of

78

![]()

Syrian industry and Egyptian agriculture. The loss of such great cities as Antioch, Damascus, Alexandria and Carthage altered the polycentric character of the empire, and Constantinople remained the sole urban centre of great size; thus Byzantine society became further centralized. This is markedly reflected in artistic and literary developments wherein John of Damascus represents the last afterglow of Byzantine cultural achievement in the lost provinces. The Greeks, Copts and Syrians of the lost provinces were now integrated into the Arab caliphate and subjected to a different culture. It is rather startling that the Egyptian and Syrian Christians, who resisted Hcllenization by rejecting the decisions of the council of Chalcedon and developing their own languages, were none the less slowly absorbed by the new masters of the Near East. The Arabization and Islamization of these peoples is one of the truly remarkable cultural phenomena in the history of mankind. The appearance of the Arabs on the eastern and southern shores of the Mediterranean led them to create a seapower which forced the Byzantines to share a condominium over the eastern waters, while commercially, the profitable carrying trade between the Far East and the Mediterranean now fell into Arab hands.

53 Arabization in the provinces lost to Byzantium during the seventh century had a decided effect on the later art style. Even Christian subjects, such as this Nativity from a Syriac Gospel of c. 1216, show an eastern (perhaps Persian) influence in the treatment of the figures and their dress

79

![]()

Great as these losses admittedly were, there were compensatory factors. The Arab occupation of the Byzantine provinces in the Levant had relieved the empire of troublesome districts which had developed separatist tendencies. Constantinople no longer had to worry about enforcement of unpopular ecclesiastical decisions in Syria and Egypt, nor about the political loyalty of the Monophysite populations. As the imperial boundaries receded, retrenchment produced a comparative strengthening of the state. This was due to the fact that the new borders corresponded more nearly with ethnic and religious lines, for the inhabitants of the empire were now largely Greek-speaking and Orthodox. Effective political control by Arabs, Slavs and Lombards had halted in eastern Anatolia, Thrace, Greece, southern Italy and Sicily, in just those areas where the Greekspeaking groups were strongest and resisted linguistic Arabization or Slavonization. The Islamic threat greatly subsided as a result of tribal strife which led to the overthrow of the Umayyads and the eastward transfer of the capital from Damascus to the regions of the Tigris-Euphrates.

These great territorial losses finally gave the Byzantine empire a cultural homogeneity which the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine and the magnificent achievements ofjustinian had failed to produce. The effort to absorb the easternmost provinces had entailed greater assimilative powers than the empire could generate. Within the southern Balkans and Anatolia, however, Byzantine culture proved irresistible and by the sixth century the non-Greek languages of western and central Anatolia were dead or moribund. Lydian, Phrygian, Celtic, Lycian, Gothic, Cappadocian and Isaurian were first reduced to rural patois and finally extinguished before the language of administration, commerce and religion.

The large numbers of foreign groups which the emperors periodically settled in Anatolia similarly succumbed. The large settlement of Slavs in Greece caused the German historian Jacob Fallmereyer to remark that ‘not a single drop of pure Greek blood flows in the veins of the modern Greeks’. A number of modern historians, under the influence of nineteenth-century racial theories which associated creative genius and cultural accomplishment with ‘purity of blood’, continue to accept his conclusions.

80

![]()

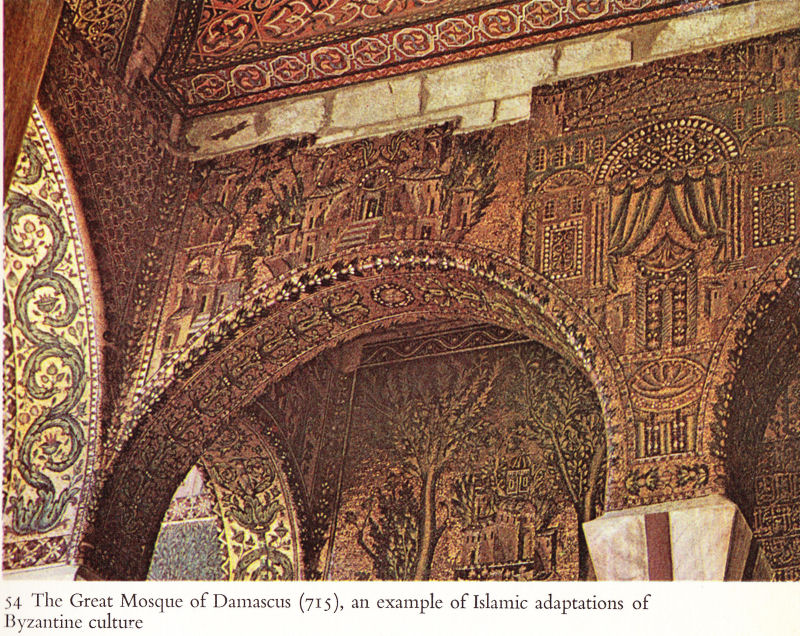

54 The Great Mosque of Damascus (715), an example of Islamic adaptations of Byzantine culture

However, the Mycenaean and classical Greeks were already products of ethnic mixture, so that even in antiquity the Greeks were not ‘of pure blood’, whatever that may mean. When the Slavic tribes came to Greece they settled in a society which was far more developed and so in the course of the centuries they were largely absorbed, Christianized, and Hellenized. In the Peloponnese they have left behind only their Slavic place-names and a few scattered notices in the sources as testimony to their former existence as a separate ethnic entity. Culturally, they seem to have had very little effect, a fact confirmed by the investigations of the Slavic philologist Miklosich who found only 129 words of Slav origin in the Greek language. In spite of the large number of Slavs who settled in Greece, investigation of the skeletons of ancient and modern Greeks has revealed a strong continuity in physical type. The physical anthropologist C. Coon was so struck by this evidence that he wrote in The Races of Europe:

81

![]()

It is inaccurate to say that the modern Greeks are different physically from the ancient Greeks; such a statement is based on an ignorance of the Greek ethnic character. In classical times the Greeks included many kinds of people living in different places, as they do today. If one refers to the inhabitants of Attica during the sixth century, or to the Spartans of Leonidas, then the changes in these localities have probably not been nearly as great as that between the Germans of Tacitus and the living South Germans, to cite but one example. . . . The Greeks, in short, are a blend of racial types. . . . The Nordic element is weak as it probably has been since the days of Homer. The racial type to which Socrates belonged is today the most important. . . . It is my personal reaction to the living Greeks that their continuity with their ancestors of the ancient world is remarkable rather than the opposite.

In the final analysis, however, it is the continuity of culture rather than physical type which is the critical factor, and the Slavs caused no break or alteration in this. The homogeneity which the empire now attained is reflected in the cultural transformation of the Armenians and Slavs who entered imperial service, as well as in the emergence of the new indigenous theme armies.

Byzantine society and economic life were undoubtedly affected by the loss of the urban centres of the Levant as well as by the violent destruction of city life by the Slavs in a large part of the Balkans. The complete disappearance of the towns in the empire would, of course, have meant the end of the Graeco-Roman traditions of Byzantine civilization. However, town life survived in the urban centres of Greece and Thrace where Sparta, Patras, Corinth, Athens, Thebes, Castoria, Thessalonica, Adrianople and Constantinople remained after the Slavic holocaust. But it was in Asia Minor that the Graeco-Roman towns remained, relatively speaking, shielded from ethnic migrations. Muslim and Christian caravans traversed the cities of the plateau, and merchant vessels visited the ports, so that the Anatolian towns served not only as administrative and ecclesiastical centres but also as focal points of commerce.

82

![]()

The village clusters were closely bound to their metropolitan centres where the farmers went to sell their grain, buy goods, and to petition the patron saint at his shrine and the judge in his court. The provincial towns were connected with Constantinople by commercial as well as bureaucratic and religious bonds. The survival of this urban society was accompanied by a money economy to which government expenditure further contributed. Annual governmental disbursement in military pay for Anatolia may have reached 1,000,000 gold solidi, and the farmers paid part of their tax in gold. The urban and economic character of the empire thus differed from that of the west where manoralism had replaced urbanism.

The survival of Byzantium under such difficult conditions is not the sole evidence of its vitality, for by the middle of the ninth century the empire began to reimpose its culture upon most of those areas which the Slavs had taken. At this time the Moravian and Bulgarian princes requested the emperor to send missionaries who would introduce Christianity to their kingdoms. There ensued a bitter competition between Rome and Constantinople over Slav souls, and though Constantinople was forced to abandon Moravia, it succeeded in converting the Bulgars to the Byzantine version of Christianity. Cyril and Methodius, known as ‘the apostles to the Slavs’, laid the foundations of Orthodox Slavonic Christianity by creating a Slavonic alphabet for the translations of the liturgy and Scriptures from Greek into a Slav dialect. This was the beginning of a process which was to spread Byzantine culture to the south Slavs, Rumanians and Russians. The rôle of the Greek Church in Slav civilization parallels the rôle of the papacy in western Europe.

B. MACEDONIANS

1. The Byzantine reconquista

The recovery from the crisis of the seventh century and the resultant consolidation in the eighth century produced a strengthened empire which was to attain new heights during the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056). Thanks to the patronage and guidance of the Macedonians the empire not only achieved spectacular military and social gains, but experienced a new literary and artistic flowering.

83

![]()

The initiative in these matters did not, it is true, come exclusively from the Macedonian dynasty, for Michael III and his advisers had already set out many of the directive lines which the Macedonians followed. In the two centuries after the accession of Basil I a new and glorious chapter was written in the pages of Byzantine military annals as the boundaries of the empire were expanded. The reconquista of the Macedonians was not as extensive as that of Justinian, but it had the virtue of being realistic. Warfare on the eastern frontier had become stabilized and by the ninth century had come to consist of raids and counter-raids, with the advantages often on the side of the Arabs. The development of this type of activity on the borders formed the milieu from which originated the medieval Greek epic, Digenes Akritas. Both in the epic and in the warfare against Islam one sees the existence and rise of the great military families of Anatolia, that is, the families ofPhocas, Argyrus, Sclerus, Ducas, Maleinus and others. The power of these provincial dynasties developed from a combination of high positions in the army and extensive estates in the Anatolian districts.

The Byzantine advance on the eastern front began when Basil I decided to put an end to the border principality of the Paulicians. A dualist heretical sect of Armenian origin which rejected the Old and much of the New Testament, denied the efficacy of the Cross, relics and icons, abhorred developed ecclesiastical institutions, the Paulicians had succeeded with the aid of the Arabs in forming an independent state. After the sect had been uprooted in Byzantine territory by the empress Theodora, the Paulicians had fled to the Arabs and eventually established themselves in the city of Tephrike, whence they raided the Byzantine empire regularly. Their most capable leader was a former imperial official, Chrysocheir, who had hesitated between loyalty to the empire and defection to the heretics. The patriarch Photius had watched over Chrysocheir carefully, admonishing him to remain faithful, but Chrysocheir finally opted for a life of heresy and freebooting. His military campaigns were far more dangerous than those of his predecessors. They carried him as far west as Bithynia and Ephesus where he stabled his horse in the 84 Church of St John (867-68), and his impudence was such that he

84

![]()

55 The Thessalonican brothers Cyril and Methodius, ‘the apostles to the Slavs’, are shown in this eleventh-century fresco kneeling before Christ in the presence of St Andrew, St Clement and angels

informed an imperial embassy which arrived in Tephrike in 869 that Basil should restrict himself to the European provinces and leave Anatolia to the Paulicians. One year later Basil managed to destroy a number of Paulician villages; but he suffered defeat before Tephrike and would have lost his life had it not been for the valour of an Armenian soldier, Theophylactus the Unbearable, father of the future emperor Romanus I Lecapenus. The event had a traumatic effect on Basil who thenceforth prayed daily in his chapel that he might not only live long enough to see Chrysocheir’s death but also that he might personally pierce the heretic’s skull with three arrows.

85

![]()

Two years later Chrysocheir was defeated and killed. The Paulicians fled eastward, Tephrike was occupied by the imperial armies, and a century later, when the advance of the imperial forces enabled them once more to establish contact with the Paulicians, John Tzimisces transplanted large numbers of them to Philippopolis, which from then on became the centre of these bellicose sectaries.

War against the Arabs would have followed the Paulician campaigns but for the involvement of the empire in Sicily, Italy and Bulgaria. The geographical location and extent of Byzantine possessions burdened the state with warfare on two very distant frontiers a thousand miles apart. In 904 the Arabs achieved their last great military success at the expense of Byzantium when the renegade Leo of Tripoli sacked Thessalonica and carried off into slavery 22,000 of its inhabitants.

With the accession of Romanus I Lecapenus, the offensive on the eastern front, which had lapsed with the end of the Paulician campaigns, was renewed. The architect of the new offensive in Anatolia was a Byzantine general of Armenian origin, John Curcuas, described in the sources as a second Belisarius and Trajan. His military talents and achievements inspired an eight-volume biography which unfortunately has not survived. Curcuas assumed direction of affairs in eastern Anatolia in 923 and for the next twenty years systematically pushed the Arabs back. His most significant victory was the recapture of the city of Melitene, which he Christianized by offering its Muslim inhabitants the choice of conversion or exile. More spectacular in the eyes of both Curcuas and his contemporaries was the return of the image of Christ on the silken towel which Christ is alleged to have sent to Abgar, the legendary king of Edessa. The Muslims of Edessa ransomed their city from the siege machines of Curcuas by giving him this celebrated image.

The momentum of the counter-offensive gathered strength under Nicephorus Phocas and John Tzimisces. Phocas, known as the ‘white death of the Saracens’, achieved the first of his spectacular victories with the reconquest of Crete in 960-61. Under the Arabs Crete had been a corsairs’ lair whence the islands and shores of the Aegean were raided, and its possession had made possible the action

86

![]()

on Thessalonica in 904. The reconquest was followed by the missionary activities of the Anatolian monk, St Nicon, who, after converting the Cretan Muslims, went on to Lacedaemonia to bring the faith to the unruly Slavs settled near Sparta. The expulsion of the Arabs from Crete and the occupation of Cyprus in 965 removed the danger of Arab naval raids on the Aegean and Anatolian coasts, and once more Byzantine naval power emerged as the decisive force in the eastern Mediterranean. In Anatolia Sayf ed-Daula made valiant efforts to avoid the final catastrophe which threatened the Hamdanid dynasty in Cilicia and northern Syria. But Aleppo, Sayf ed-Daula’s capital, surrendered a year after the fall of Crete and he himself lived to hear the news of the fall of Tarsus in 965. When the imperial troops entered this important Cilician city they quickly transformed it into a Christian town by again offering the Muslims a choice between exile and conversion, and also by bringing in Greek and Armenian colonists.

The last great victory of Phocas’ armies was the capture of Antioch in 969. The restoration of this patriarchal seat and commercial centre to the Christian empire after centuries of subjection to the infidel was the most stirring accomplishment of Phocas’ reign. The religious passions of the combatants were the most salient features of the bitter struggle. For the Muslims the jihad or religious war was a duty enjoined by Islam. Phocas, highly religious and an ascetic, wished to have every soldier who fell in the wars declared a martyr for the faith, but was frustrated by the disagreement of the patriarch. Phocas’ bellicosity is vividly revealed in a letter which he sent to the caliph in 964:

In the fighting in the passes your men of arms have been chased like a troop of animals. We have reduced to impotence your peasants and their women. The tall buildings have been destroyed and their ruins, once flourishing centres, have turned into an uninhabited desert. Only the owl’s cry and its echo from the columns fill the solitude.

Antioch is not far . . . soon I shall reach it with a numerous multitude . . . O you who inhabit the deserts of sand,

87

![]()

maledictions upon you. Return to your country of Sana, your first home. Soon I shall conquer Egypt by my sword and its richness shall swell my booty. . . .

I shall conquer all the east and west and I shall send out in all places the religion of the cross. Jesus has His throne which is elevated above all the heavens . . . while your prophet has been buried in the ground. May his bones decompose into dust . . . and his sons be plagued by death, captivity and dishonour.

The death of Phocas at the hands of the empress’s lover John Tzimisces did not interrupt the war. Tzimisces completed the reconquest in 975 by his triumphal procession through Syria, and the cities of Damascus, Sidon, and Beirut all capitulated to him. Once again in control of northern Syria, the emperors now turned to the Armenian and Georgian principalities of northeastern Anatolia. These were largely assimilated as a result of the policies of Basil II and his successors, so that by the mid-eleventh century Byzantine military might seemed all-powerful in the east.

88

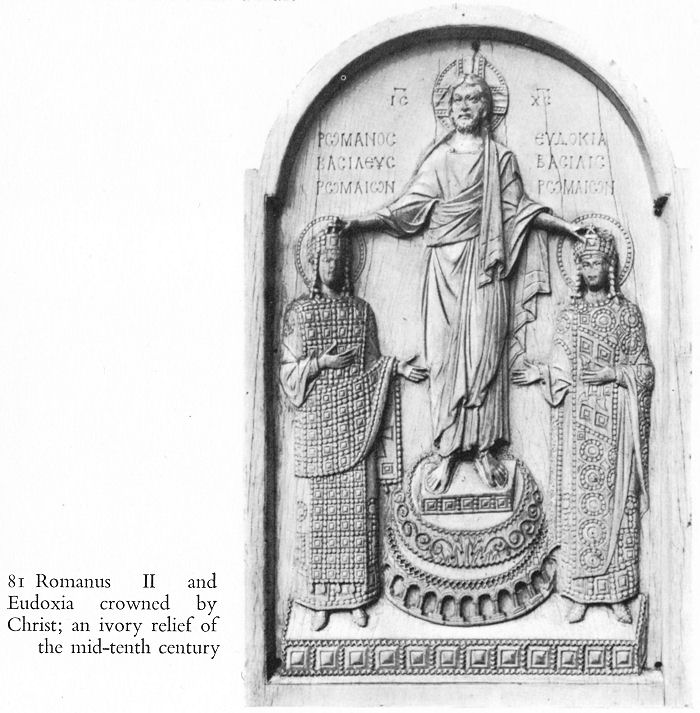

![]()

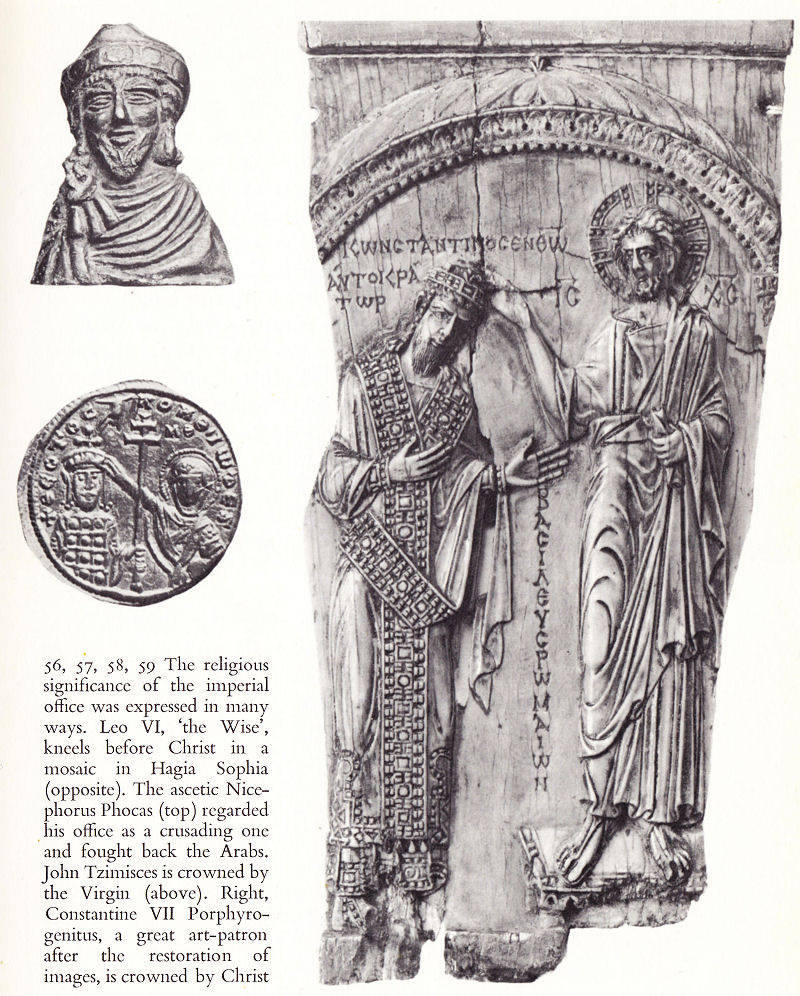

56, 57, 58, 59 The religious significance of the imperial office was expressed in many ways. Leo VI, ‘the Wise’, kneels before Christ in a mosaic in Hagia Sophia (opposite). The ascetic Nicephorus Phocas (top) regarded his office as a crusading one and fought back the Arabs. John Tzimisces is crowned by the Virgin (above). Right, Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, a great art-patron after the restoration of images, is crowned by Christ

89

![]()

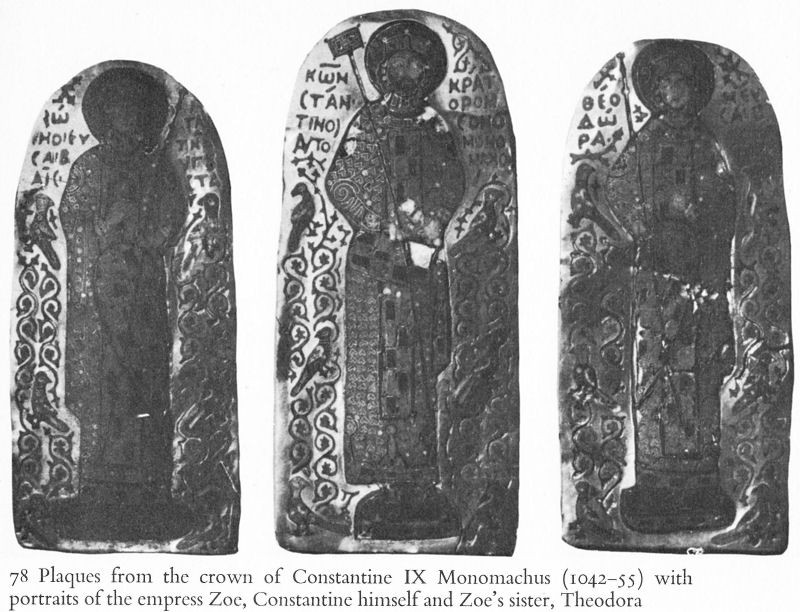

The victories in the east had their parallels in the Balkans where the reign of Romanus I Lecapenus once again marks a turning-point. Earlier it had been far from evident that Byzantine arms would be successful for Symeon, who succeeded his father on the Bulgarian throne in 893, defeated and terrorized the empire until his death in 927. Not only did he force the imperial government to pay tribute, but when the emperor suspended the payments he advanced with his army to the walls of Constantinople itself. The weakness of the Byzantine government at that time was such that Symeon obtained the title of emperor, was crowned by the patriarch, and arranged the engagement of his daughter to the young Constantine VII. But the revolution which put Romanus Lecapenus in charge of affairs in Constantinople was a setback for Symeon, whose aim seems to have been to replace the Byzantine by a Bulgarian empire. The arrangements Symeon had made for his daughter’s marriage, as well as his own coronation, were now cancelled and his frustration was completed when Romanus assumed the imperial title in 919 and arranged for the marriage of his own daughter to Constantine VII. Nevertheless, a compromise was reached five years later when Romanus met Symeon and accorded him the title of emperor, much as Michael I had done in the case of Charlemagne in 812, though it was made plain that it was not to apply to the Byzantine empire. Symeon then became involved with the Serbs and Croats, and when he died in 927 his son Peter, a more docile type, became an obedient son-in-law of Romanus I. Thenceforward Byzantine influence spread in the Bulgarian kingdom, though it was accompanied by the rise of the dualist heresy of the Bogomils.

In the reign of Phocas relations between Byzantium and Bulgaria once more became agitated and as the emperor was occupied with the Muslims he called on the Russian prince Svyatoslav for help. The latter defeated the Bulgarian armies on the banks of the Danube and by 969 had made himself master of the kingdom. This turn of events forced John Tzimisces to undertake the great expedition of 971 in which the Byzantine armies captured the Bulgarian capital of Great Preslav. Svyatoslav was forced to surrender at Silistria, and Tzimisces annexed Bulgaria and abolished the Bulgarian patriarchate.

90

![]()

Early in the reign of Basil II, however, the Bulgarians successfully revolted and formed a short-lived kingdom under the leadership of their tsar Samuel. Basil’s efforts to subdue Samuel and prevent Bulgarian expansion were seriously impeded by wars with Islam, but even more by the revolt of the two most powerful Anatolian families in 986. For a moment it seemed as if the armies of Bardas Phocas and Bardas Sclerus would succeed in removing the Macedonian dynasty and in splitting the empire into a European and an Asiatic state. Eventually, however, Basil terminated the civil war successfully, but only after an exhausting struggle and with the support of Russian troops. He then put an end to Bulgarian resistance, crushing the enemy forces at the Struma River in 1014. Legend has it that he blinded 14,000 Bulgarian soldiers after the battle, and that when Samuel saw the dreadful sight he fell dead. Within a few years the entire Balkan peninsula was either in Byzantine hands or acknowledged imperial suzerainty.

The renewed power and self-confidence of the empire and its rulers produced a new collision with the western empire under Otto I. When Otto was crowned emperor in Rome in 962, his assumption of the imperial title was considered in Constantinople to be an usurpation, and his military expansions into southern Italy further agitated the Byzantine ruler. It was under these circumstances that Otto sent his emissary, Liudprand of Cremona, to Constantinople in order to arrange a marriage alliance and a dowry which would bring Byzantine Italian possessions to the Ottomans. Phocas’ sense of imperial propriety was outraged no less than the sensibilities of Otto’s ambassador, who has left an acerbic, yet witty, account of his embassy to Constantinople. Liudprand’s account is something more, for it paints in bold strokes a picture of two societies which over the centuries have developed differently in every respect. Nicephorus Phocas repeatedly taunted Liudprand with the remark that his master was a king, not an emperor, and barbarian rather than a Roman, to which Liudprand variously replied that the title Roman was more appropriate to the inhabitants of Italy on the basis of language, or that the Romans as descendants of the slaves and murderers with whom Romulus founded Rome were inferior to the Lombards and Saxons.

91

![]()

His description of Phocas is an entertainingly vicious caricature:

He is a monstrosity of a man, a dwarf, fat-headed and with tiny mole’s eyes; disfigured by a short, broad thick beard half going grey; disgraced by a neck scarcely an inch long; piglike by reason of the big close bristles on his head; in colour an Ethiopian and as the poet says, ‘you would not like to meet him in the dark’.

Liudprand put forward the ancient Roman view of the Greeks, and quoted Virgil’s opinion that ‘their tongues are saucy, but cold are their hands in war’. Not only were the Greeks cowards but they were fond of flattery and given to greed and lying. Nicephorus, victorious over the Arabs, had equal scorn for western military and personal qualities, saying that the westerners were debilitated militarily because of the heaviness of their armour and weapons. The long hair and more elaborate robes of the Greeks, so different from western styles, Liudprand associated with Greek effeminacy, and his reaction to Greek cuisine was choleric. It was bad enough to live in draughty unheated halls, but to be expected to drink resinated wine and to eat dishes at imperial banquets which were heavily doused with vile fish sauces and garlic was insufferable. The vitriolic comments of Liudprand constitute an important commentary on the differences between the societies and cultures of east and west, and give a preview of the relations between Greeks and Latins as they emerged in the later period of Byzantine history.

2. Economic life

The fortunate political and military developments of the Macedonian period greatly fostered economic prosperity. The expansion of the frontiers brought new agricultural lands, manpower and revenues, and the cessation of Arab raids with the establishment of security allowed the rural population to cultivate their land in peace. The free peasant communities remained important sources of agricultural production alongside the estates of the great magnates.

92

![]()

60 Basil II, ‘the Bulgar-slayer’, under whom the Byzantine state reached its last great peak of power

93

![]()

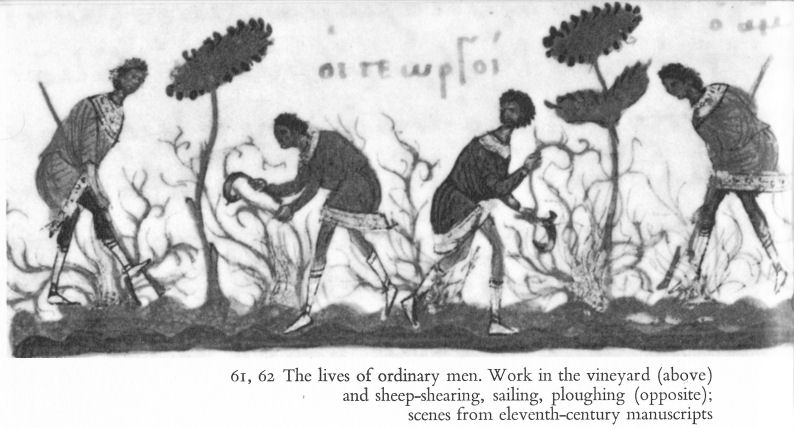

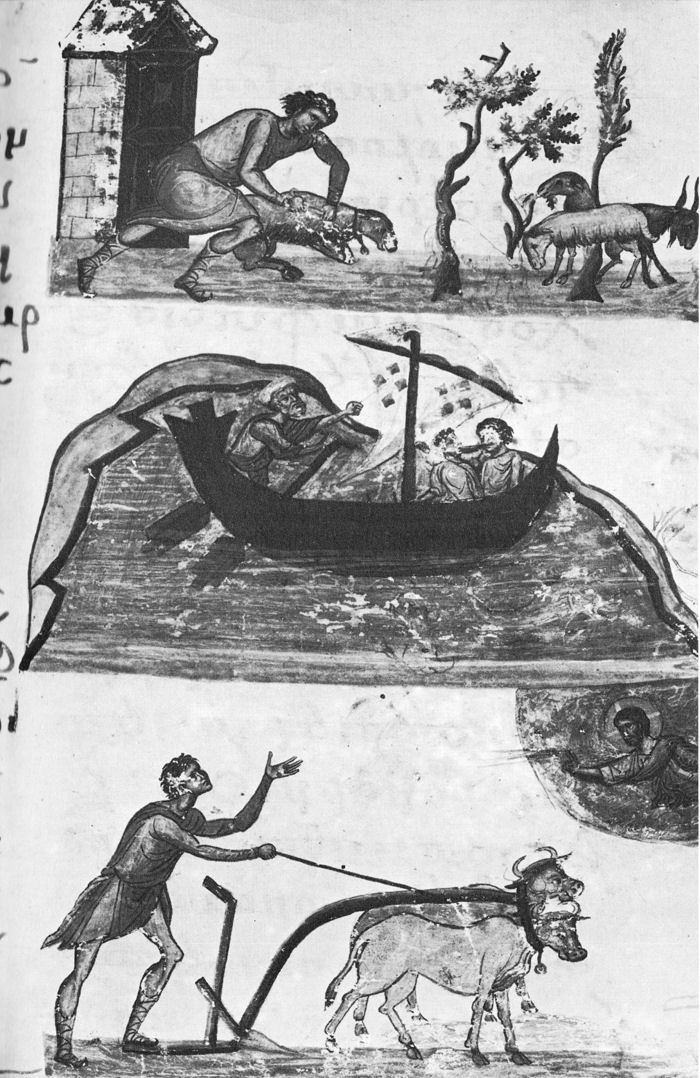

61, 62 The lives of ordinary men. Work in the vineyard, (above) and sheep-shearing, sailing, ploughing (opposite); scenes from eleventh-century manuscripts

The technology of farming had probably changed little (in contrast to developments taking place in western Europe) since late antiquity, though new crops such as rice and certain fruits had been introduced. The methods of farming and the crops themselves remained remarkably constant until the early modern period, and it is interesting that this persistence of Byzantine agricultural traditions is still reflected by the Greek loan-words in the spoken Turkish of Anatolia. The main products of the rural areas were, of course, cereals, vegetables, fruits, nuts, livestock, freshwater fish and timber. The river valleys of western Asia Minor, the Pontic and southern coastal regions, and Mesopotamia grew abundant wheat crops, whereas barley was the principal grain in many of the plateau regions. In the Balkans the centres of grain farming were Thrace and Thessaly. Greece and Anatolia were then, as today, productive of a wide variety of fruits, most of which were known in classical times though some (such as the banana) seem to have been introduced into Anatolia in the Byzantine period. The vineyards of Cappadocia were famous for their wines in the Middle Ages, and Liudprand, as we have already seen, commented upon the custom of putting resin in Greek wine, a practice known in both classical and modern Greece.

94

![]()

95

![]()

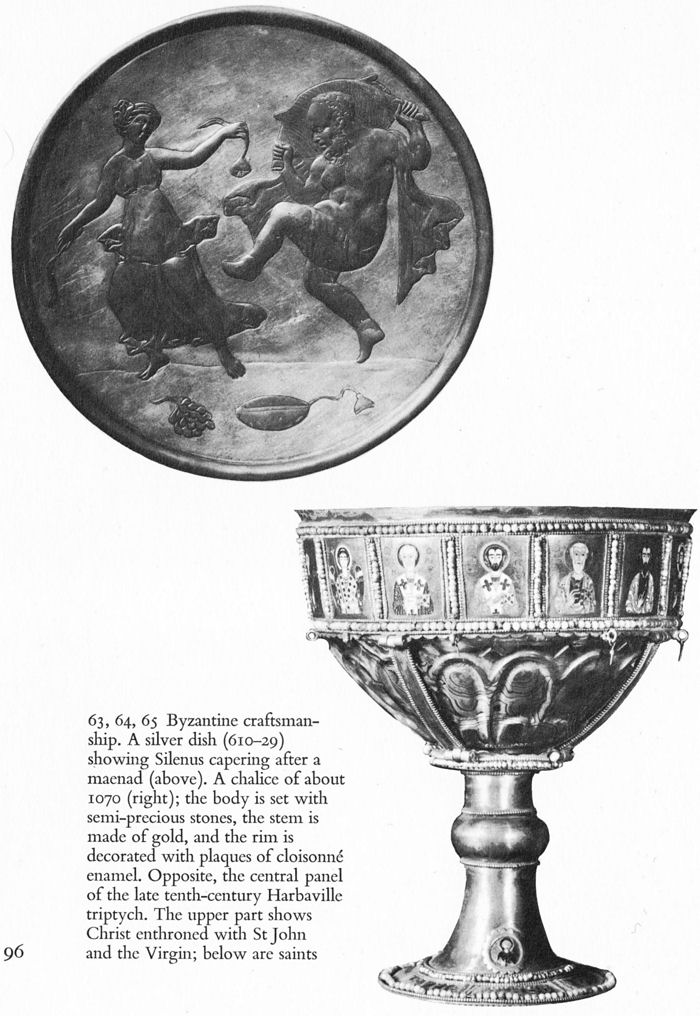

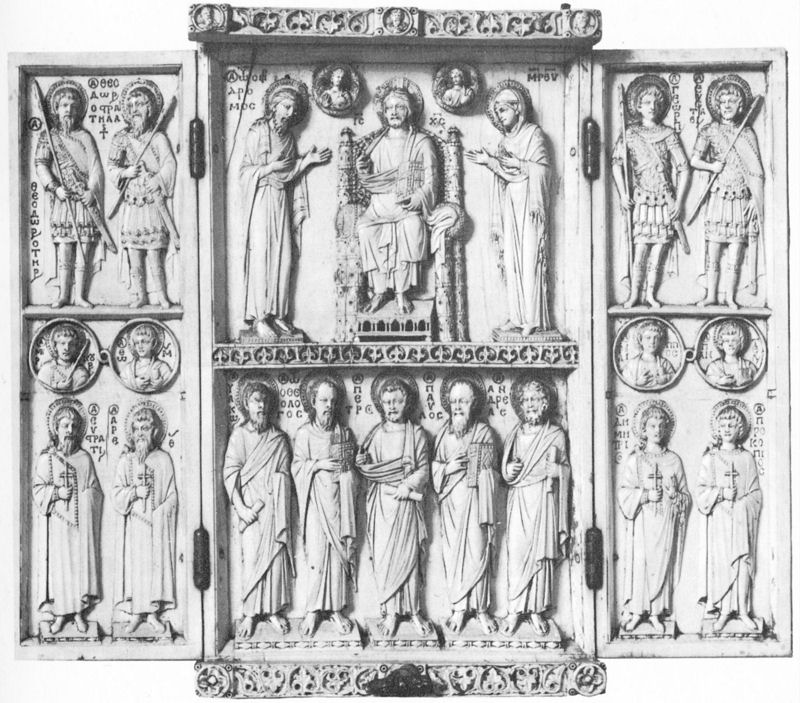

63, 64, 65 Byzantine craftsmanship. A silver dish (610-29) showing Silenus capering after a maenad (above). A chalice of about 1070 (right); the body is set with semi-precious stones, the stem is made of gold, and the rim is decorated with plaques of cloisonne enamel. Opposite, the central panel of the late tenth-century Harbaville triptych. The upper part shows Christ enthroned with St John and the Virgin; below are saints

96

![]()

Because of the survival of the Graeco-Roman urban centres the empire possessed a vast reservoir of craft skills which, when combined with the physical resources of the provinces, gave Byzantine industry the qualities of efficiency and excellence. Arab writers found the excellence of Byzantine craftsmen such that they could compare it only with the virtue of their Chinese equivalents; and a twelfth-century Latin author of a book on crafts included a number of technological processes of Byzantine origin. The regulative mentality of Byzantine statecraft intruded itself upon the organization of industry and was no doubt partly responsible for the high quality of the products, though regulation was used to control not only quality but also prices and the availability of goods.

96

![]()

The state, through its urban officials, exercised supervision of the craftsmen via the corporations into which they were organized. The guilds, directly descended from those of the Graeco-Roman world, had a limited membership and many of their members managed to accumulate considerable wealth and achieved social prominence. By the later years of the Macedonian period the guilds were playing the same rôle as had the circus factions previously in the political life of the city, rioting and removing monarchs and unpopular officials. The most famous products of Byzantine industry were the luxury goods which the imperial goldsmiths and weavers created in the workshops of the palace. These brilliant textiles and jewels were reserved for the imperial family or for official gifts to foreign courts.

Industry seems to have been significant not only in Constantinople but in the provinces as well, where the raw materials were conveniently at hand. The mines of the Chalcidice, Euboea, Laurium and Anatolia yielded the essential metals, stone, and alum. The tradition of cloth-making was ancient in the urban centres of Greece, Asia Minor, and the Aegean isles; and in Byzantine times Corinth, Patras, Thebes, Laodicea, Cerasus, and Nicaea were famous for the products of their looms.

Constantinople under the Macedonians was the greatest emporium in the Christian world, and attracted merchants and goods from Europe, the Islamic lands, India, and China. It was also the economic centre of the empire, drawing upon the production of the provinces for the sustenance of its citizens and the armed forces. Each provincial city served as the economic focus of its neighbourhood where the villagers sold their agricultural produce and bought the products of the local craftsmen. The local fairs (panegyreis), usually associated with the local patron saint, attracted both Byzantine and foreign merchants. At the great fairs of Trebizond, merchants from the east sold perfumes and spices and bought Byzantine carpets and brocades. Since these merchants plied the Anatolian routes all the way to Constantinople, the provincial towns profited from international as well as local trade. The combination of territorial expansion and commercial prosperity produced so much state income that Basil II was able to remit taxes for a two-year period.

98

![]()

3. The rôle of the Church

In a society and period where religion and government were inseparable the expansion of the state’s frontiers produced a corresponding expansion of the power of the Church. In all the reconquered provinces of the east, Orthodox bishops once more sat on the episcopal thrones from which the Orthodox clergy had previously been banished. The patriarchal see of Antioch experienced a revival of its pre-Islamic glory, but Byzantium had to face again the Monophysite problem. The Christians of northern Syria, the districts of Melitene and Armenia were predominantly Monophysite, and as the emperors attempted gradually to enforce ecclesiastical union, the Armenians and Syrians became increasingly restless in the eleventh century. Within the empire the increase of population and prosperity resulted in the creation of new bishoprics and metropolitan provinces. After the conversion of the Bulgars in the reign of Michael III Christianity and Byzantine culture spread throughout the Bulgarian kingdom in the ninth and tenth centuries. The Church demonstrated its vitality within the empire by its Christianization of the Slavs in the Peloponnese and Anatolia and the Muslims in Crete, an essential process without which provincial society could not have become unified.

The greatest victory of the Greek Church, however, was the conversion of Kievan Russia in the reign of Basil II. The emperor, having received substantial military reinforcements from Prince Vladimir to combat the serious rebellion of Bardas Phocas in Asia Minor, promised to give the Kievan prince his own sister Anna in marriage, provided that Vladimir and his people were converted to Christianity. The Russian aid was decisive in Basil’s victory over the Anatolian rebels but the novelty of giving a daughter of the imperial house to a barbarian ruler was so distasteful that the emperor hesitated to fulfil his part of the agreement. When Vladimir attacked the Byzantine possessions in the Crimea, however, Basil gave way, with the result that Russia came under strong Byzantine influence at a time when the Russians were becoming civilized. The conversion of the Russians represents the greatest territorial expansion of Greek missionary activity, and Russian colonists were eventually to carry the Orthodox faith across Siberia to Alaska and California.

99

![]()

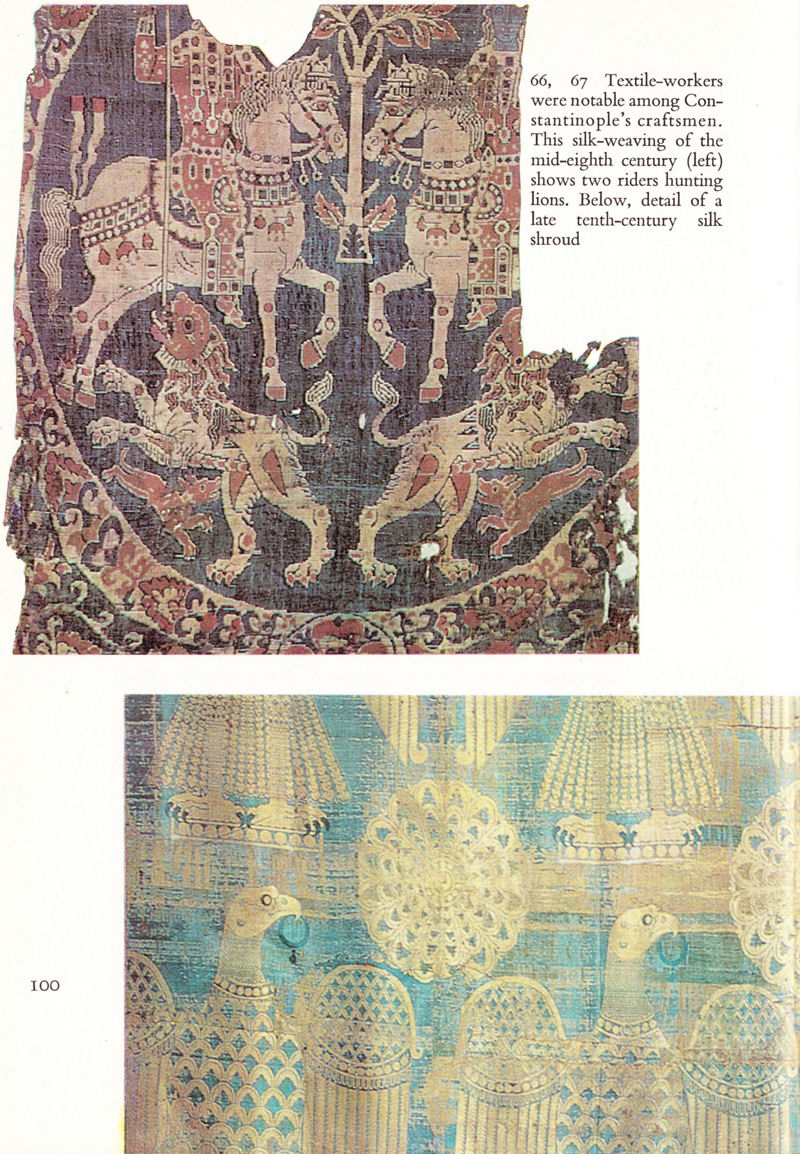

66, 67 Textile-workers were notable among Constantinople’s craftsmen. This silk-weaving of the mid-eighth century (left) shows two riders hunting lions. Below, detail of a late tenth-century silk shroud

100

![]()

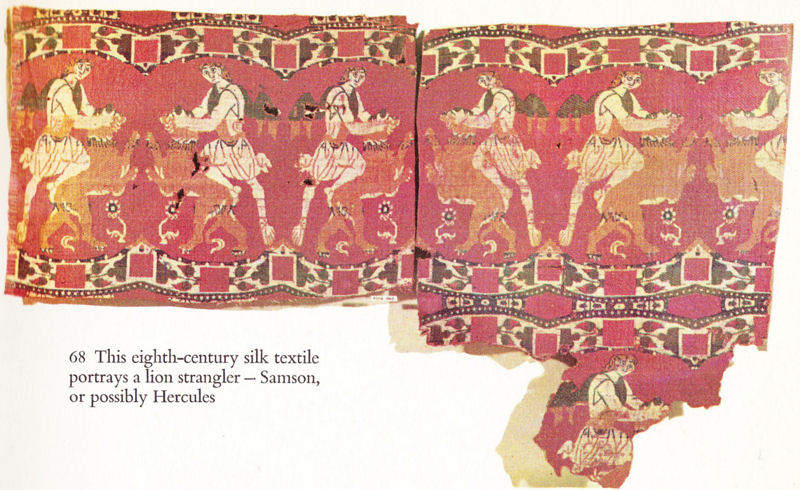

68 This eighth-century silk textile portrays a lion strangler — Samson, or possibly Hercules

The Iconoclastic controversy, which had been such a severe crisis for the Church, stimulated a final burst of theological speculation on the Christological issue, but thereafter the earlier theological vitality of the Orthodox Church gave way to a concern for the preservation of the faith in an unaltered form. Such further developments in theology as there were could not compare with the earlier theological accomplishments. On the other hand the monastic movement, which had borne the brunt of the struggle with the Iconoclast emperors, underwent a very intensive development and expansion in the Macedonian period. Mysticism, intimately related to the monastic life, remained an important element in Byzantine religiosity. The appearance of the great mystic, Symeon the New Theologian, symbolizes an intensification of personal religious experience at a time when theological originality had disappeared. Religious life became less intellectual and more emotional.

The traditional Byzantine sympathy and proclivity for the contemplative life waxed stronger after the martyrdom which the monks and nuns suffered at the hands of Constantine Copronymous and his agents. Increasing numbers of men and women sought the salvation of their souls in the monasteries which pious emperors, merchants, and peasants founded.

101

![]()

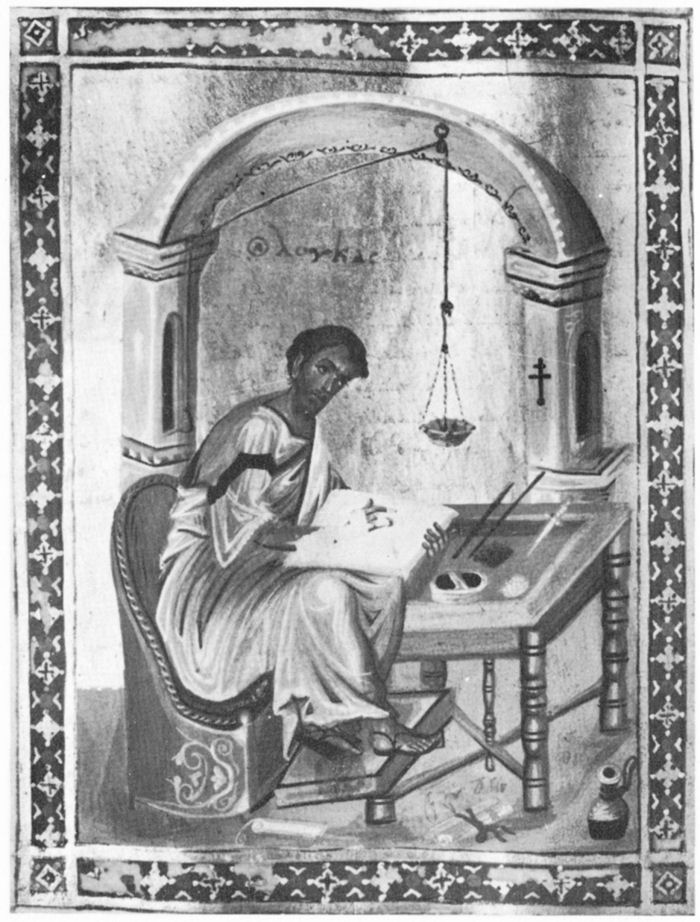

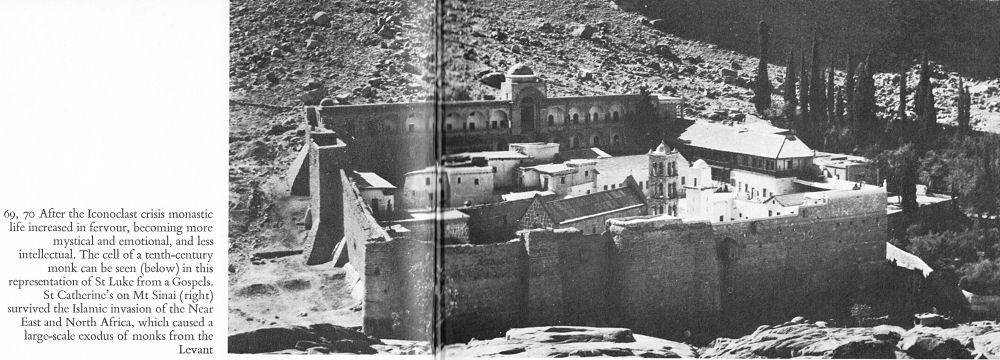

69, 70 After the Iconoclast crisis monastic life increased in fervour, becoming more mystical and emotional, and less intellectual. The cell of a tenth-century monk can be seen (below) in this representation of St Luke from a Gospels. St Catherine’s on Mt Sinai (right) survived the Islamic invasion of the Near East and North Africa, which caused a large-scale exodus of monks from the Levant

102

![]()

The rapid increase in monastic foundations meant not only that large numbers of men withdrew from the affairs of the world, but that the monastic properties became a liability to the imperial fisc. Hence the emperors of the tenth and eleventh centuries resorted to legislation and confiscation in an effort to restrict the harmful effects of monastic growth. The Arab conquest of the Near East had caused a profound shift in the geographical centre of Byzantine monasticism as monks in great numbers fled from the Levant and re-established themselves in those lands still remaining in the empire.

The consequence was a decline in the importance of the eastern lands as monastic centres. The monasteries of Palestine, which had replaced the Egyptian monasteries in pre-eminence in the fifth and sixth centuries, still attracted some religious men but largely because the foundations were located in the Holy Land. The monasteries of northern Syria, closer to Christian lands and somewhat isolated from the Muslims by their mountainous situation, maintained a more lively existence, to which the Byzantine reconquest of this region

103

![]()

gave a further stimulus. The most remarkable of the monasteries in Islamic lands was that of St Catherine’s on Mount Sinai. Monks had settled around Mount Sinai as early as ad 400 and over two centuries later Justinian built the present church and the walls which surround it. Geographical isolation and Muslim protection explain the survival of the monastery’s important collection of manuscripts and icons, but they render difficult any explanation of St Catherine’s importance in the history of pilgrimage. Its location in Muslim lands fortunately removed the monastery from the Iconoclastic measures which destroyed the icons throughout the empire. Consequently, the monastery today possesses the only extensive collection of Byzantine painting, a collection which enables scholars to study the traditions of Byzantine painting from the pre-Iconoclastic period to modern times.

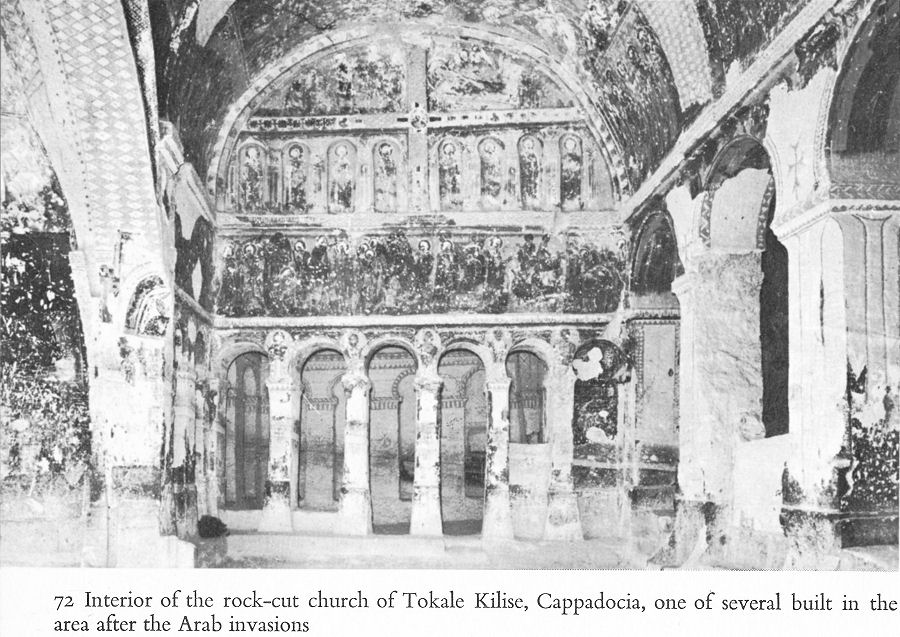

After the seventh-century Arab invasions Anatolia became the most important area of monastic activity (apart from Constantinople), and it remained so until the Seljuk invasions. Monastic foundations numbered hundreds, and Mount Olympus near Prusa and northwest Anatolia were populated by thousands of monks. The picture was the same throughout western Anatolia in the regions of Apamea, Ephesus, and Miletus. The most interesting physical remains of this vibrant monastic life are the conical troglodyte monasteries of Cappadocia some seventy miles southwest of Caesarea. Indicative of Anatolia’s importance is the fact that St Athanasius, the real founder of Athonite monasticism, was a Trebizondine and that St Symeon the New Theologian was a Paphlagonian.

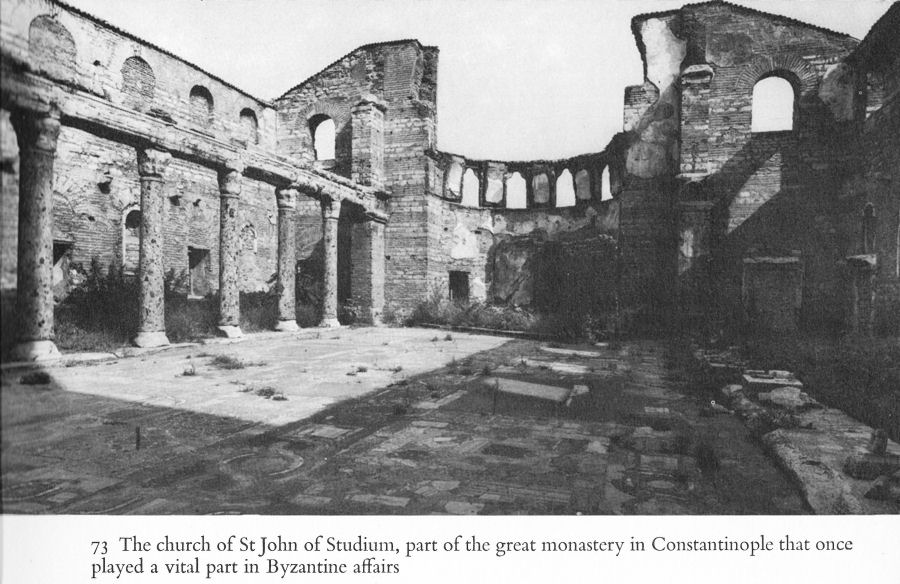

Constantinople had also become a very significant centre of monastic life since by the sixth century Egyptians, Syrians, Sicilians and Lycaonians had established religious houses for their compatriots in the city. The monastery of Studium had taken a commanding position under its abbot Theodore in the ninth century and his monastic rule exercised an important influence in the history of Byzantine monasticism. The vitality of this foundation is evident in the rôle which its abbots played in Church politics and in the 104 importance of its scriptorium. The founding of new monasteries

104

![]()

71 The monastery of St Catherine’s, built by Justinian, contains the only extensive collection of pre-iconoclast Byzantine images, including this sixth-century Virgin enthroned

105

![]()

72 Interior of the rock-cut church of Tokale Kilise, Cappadocia, one of several built in the area after the Arab invasions

accelerated in the eleventh century and one modern scholar has been able (without any claim to completeness) to identify some three hundred monasteries in Byzantine Constantinople.

The principal event in the history of Greek monasticism during this era was the emergence of Mount Athos as a new monastic realm. Holy men had practised asceticism on the Holy Mountain as early as the ninth century. There was even an attempt to establish a coenobium in 870, but the growth of monasticism was hindered by the naval raids of the Muslim pirates of Crete. Only two years after Phocas’ reconquest of Crete his friend Athanasius founded the Great Laura on Athos, and by the time Tzimisces issued the first document regulating life on the Mountain there were some fifty-eight settlements of monks. Within a century the number rose to 180, and this was further expanded by the appearance of large numbers of foreigners in the twelfth century. Russian monks appeared in the monastery of Xylourgou (1142), Savas founded a Serbian group at Chilandar (1198), the Georgian monastery of Iviron became prominent at an earlier date.

106

![]()

73 The church of St John of Stadium, part of the great monastery in Constantinople that once played a vital part in Byzantine affairs

Bulgars took over the Zographou monastery, and the Christian descendant of a Seljuk sultan founded the house at Koutloumousiou in the twelfth century.

The growth of Mount Athos coincided with the decline of Turkish-dominated Anatolia and increasing Christianization of the Slavs. The monks of Mount Athos maintained a certain ecclesiastical independence from the patriarchs in Constantinople until the period of the Palaeologues, an autonomy which was observed by the Turks and is still in effect today. Indeed, Athos remained the spiritual focus of the whole of Orthodox monasticism until the early twentieth century. In its monasteries the monks cultivated and kept alive the mystical and ascetic traditions of the Byzantine fathers, copied and preserved their literary compositions, and of course continued the Byzantine style of painting. As late as the eighteenth century Russian, Rumanian, south Slav and Greek clergy were inspired by the Athonite community. The Russian cleric Velichkovsky, reacting to Latin influence in Russian seminaries, sought and found in the libraries of Athos the Byzantine sources of piety. These texts and the Painter’s Manual were translated from the Greek into the various

107

![]()

languages of the Orthodox faithful with the result that Byzantine traditions of spirituality and art were temporarily renewed.

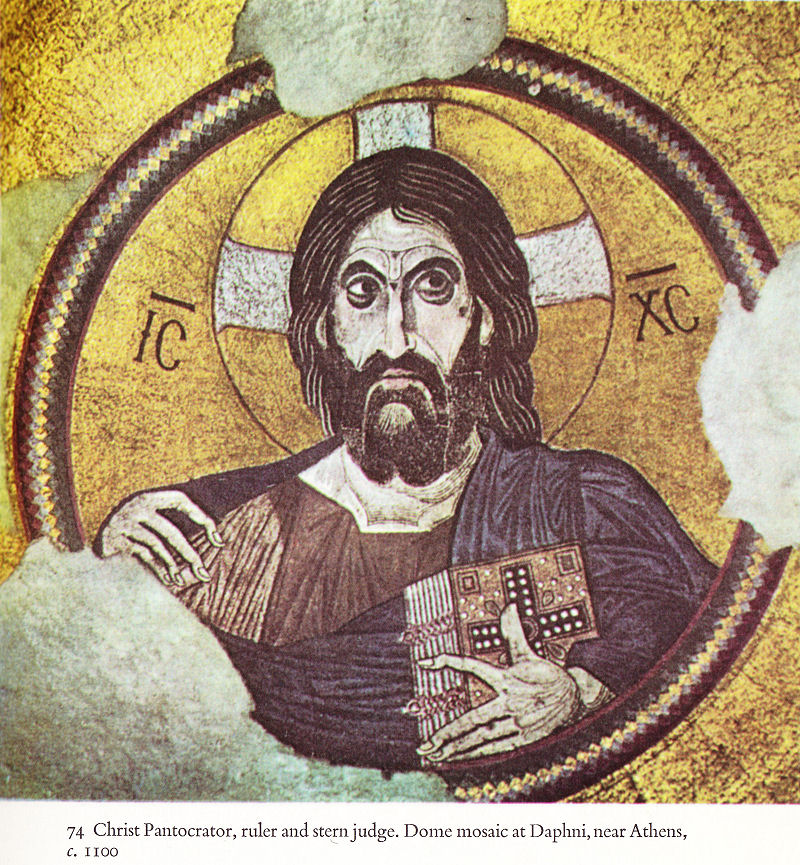

Of the monasteries in Greece and the Aegean islands the churches of Hosius Lucas (Phocis), Daphni, and Nea Mone (Chios) are well known for their exquisite mosaics, and the monastery of St John on Patmos (late eleventh century) for its manuscripts. The Greek monastic foundations in Sicily and southern Italy, however, were more remarkable. Their development apparently coincided with the settlement of monks who fled from the Arabs in the seventh century, and in a manner resembles the experience of Anatolian monasticism. These establishments, of which there were hundreds, developed their own hagiography and art, and helped to spread Byzantine civilization in the region. The most famous of these monasteries, inspired by St Neilus (d. 1004), was Grottaferrata, but other Greek monasteries existed as far north as Rome.

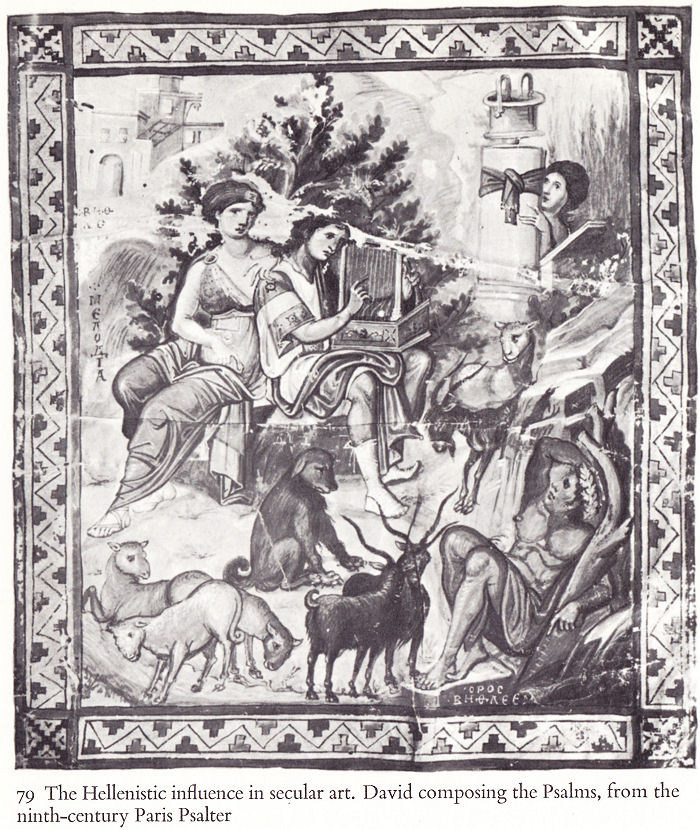

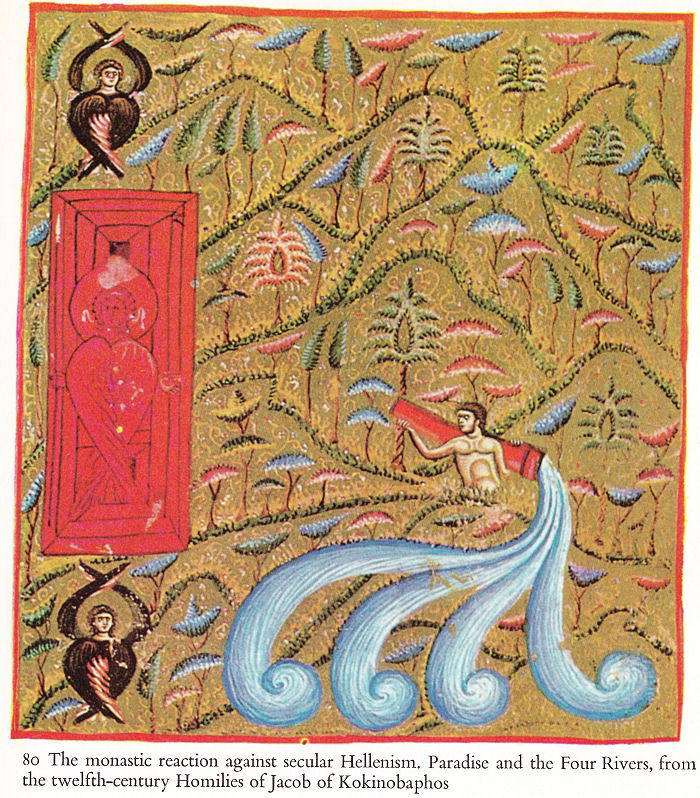

Though monasticism had obvious social defects and was intellectually obscurantist, it also had its meritorious side, for monasteries often provided charity and education to the Christians. The typika, which regulated the life of the monks in the various houses, often record that sums of money were set aside for the care of the poor, orphans, the sick, travellers, etc. Similarly, they describe the contents of the monastic library which were largely, though not exclusively, of a religious nature. The monks in the scriptoria were perennially busy copying manuscripts, and it is thought by some that the scribes of Studium were responsible for introducing a large-scale reform of Byzantine script in the ninth century. This conservative rôle of the monks in preserving literature was essential for Byzantine education and is responsible for having saved much of Byzantine writing from oblivion.