III. DECLINE, 1057-1204

2. Victory of the military 123

3. Social and economic changes 126

On the death of Basil II (1025) the power and glory of Byzantium seemed to be securely established, for not since the Heraclian reconquests had the empire experienced a comparable expansion. The state’s boundaries stretched from the Danube to Crete and from southern Italy to Syria. The eastern waters had once more become a Byzantine lake where the Greek fleets cruised about freely from their advance bases in Crete and Cyprus. The brilliant victories of the late tenth and early eleventh centuries had brought peace to the empire, and greatly contributed to the cultural flowering of the eleventh century. The conversion of Russia had resulted in a parallel expansion of the Church, making it a formidable rival of the papacy. The great conquests had increased the wealth of the state, filling its treasury to overflowing. Because of the growth in revenues and the new booty Basil II had to build extensive underground vaults so that the treasury could accommodate this vast income. The peace and affluence which followed the death of Basil served as a powerful stimulus to art and literature both in the capital and the provinces. The activity of Psellus and his circle in Constantinople coincided with great architectural activity in the provinces.

1. INTERNAL PROBLEMS

Yet, within half a century of Basil’s death, both the Macedonian dynasty and the prosperity which it had created had disappeared. In the early years of the reign of Alexius I Comnenus (1081-1118) the empire had declined to a pale shadow of its former glory, its possessions largely contained by Adrianople in the west and the Bosphorus in the east. So complete was this decline that it is quite startling to the historian. Its cause was a remarkable confluence of internal ills which exhausted the body of the empire as it was being attacked from the outside by vigorous new forces. The most virulent of these illnesses was the strife between the civil bureaucrats and the provincial generals.

121

![]()

Since the very foundation of the empire by Diocletian and Constantine there had existed a sharp division between the men of the pen and those of the sword, a tension noticeable in other highly-developed empires, such as the Chinese and Islamic. The separation of civil and military power by Diocletian had tended to weaken the military class, but with the system of themes, and the subordination of both powers to the generals, the military class again became powerful. Their domination of society was further facilitated by the fusion of the strategoi with the great provincial landowners. The successes of Byzantine arms in the tenth and eleventh centuries bred a great arrogance in this military class and an ambition to overthrow the hegemony of the bureaucrats within the government. Thanks to his cruel vigour Basil II was able to bridle these ambitions through military action and unrelenting persecution; and the sequestered lands of the magnates constituted an important source of revenue for the imperial fisc under him. But Basil was succeeded by his incompetent brother Constantine, and when Constantine died, leaving three daughters as heirs, the lack of a competent male successor, who could control the military and their competition with the bureaucracy, brought disaster.

At first the bureaucratic circle of the capital, consisting among others of eunuchs, university professors and the aristocratic families of Constantinople, established its control over the organs of government and successfully frustrated the ambitions of the generals. The difference in character of the two groups manifested itself in rebellions of the generals and retaliatory persecutions by the civil officials. Upon the death of Constantine VIII the succession devolved upon his unmarried daughter Zoe, and the competition of the bureaucrats and soldiers centred about the choice of the empress’s husband. Though the legal fiction of dynastic succession was maintained, it was grotesquely perverted by the plots of the two factions contending to furnish their own candidates as prince-consort. Until 1057 the generals were repeatedly defeated, unleashing in the course of this thirty-years period at least one major rebellion annually.

So long as representatives of the dynasty survived, the bureaucrats were successful in maintaining their hegemony, for dynastic sentiment had taken firm root in the people of Constantinople.

122

![]()

This was manifested clearly when Michael V unsuccessfully attempted to put an end to the Macedonian line. The nephew of an obscure eunuch, John Orphonotrophus, who had succeeded where the powerful generals had failed (by promoting successive love-affairs between Zoe and his nephews), Michael V dared to banish Zoe from the palace. The wrath of the Constantinople guildsmen and citizens put a violent end to his attempted usurpation. The power which possession of the capital gave the administrative officials was dramatically stated by the general Cecaumenus, who advised his son never to rebel against the emperor since whoever possessed Constantinople would always prevail.

2. VICTORY OF THE MILITARY

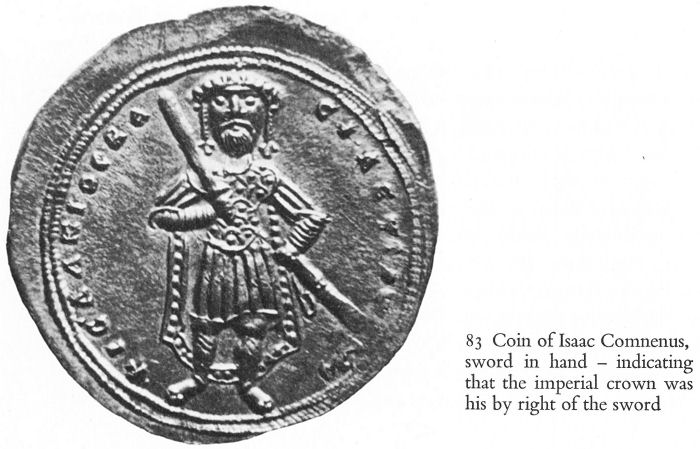

The first success of the generals took place in 1057 in the rising of Isaac Comnenus. It is significant that the principal Anatolian aristocrats joined the ranks of the revolutionaries in Asia Minor, but in spite of this formidable array the civil element might have remained secure in Constantinople had it not been for certain significant developments within the city. There the leader of the civil aristocracy, Constantine Ducas, had become dissatisfied with the control which the court eunuchs and officials exercised over Michael VI. Consequently he joined the conspiracy of Comnenus and, as he was married to the niece of the patriarch Cerularius, this no doubt helped to swing Cerularius to the side of the Anatolians. Psellus, head of the senate and the intellectuals in the bureaucracy, had been closely associated with Ducas in former years; hence it is no surprise that he betrayed Michael VI to the advancing armies. When Isaac Comnenus approached Constantinople the patriarch unleashed a rebellion of the guildsmen which culminated in the removal of Michael VI and the accession of a general to the throne. Isaac I could boast that he had taken the empire with the sword (he did so by depicting himself with sword in hand on the gold coinage), but the victory of the military was a hollow one inasmuch as the assistance of the bureaucratic leader Constantine Ducas had made it possible. When Isaac retired from the throne (1059) Ducas succeeded him and the bureaucrats

123

![]()

under the direction of Psellus pursued the military establishment relentlessly. Until the final victory of the military aristocracy under Alexius I (1081) the course of the struggle vacillated between the two sides.

The prolonged struggle between the generals and civil officials convulsed the empire at a critical period. The generals, frustrated by the officials in the capital, had recourse to the armies which they commanded and repeatedly denuded the frontiers of military forces in order to attack their enemies in the capital. They did this at a time when the pressure of the Seljuks, Patzinaks and Normans was increasingly threatening the frontiers of the empire. The employment of the armies in the political struggle not only diminished their numbers and effectiveness, but finally led to the systematic disbanding of the native levies by the bureaucrats who had every reason to fear them. The military service of the inhabitants in the border regions was commuted to a cash payment, and funds were generally withheld from the military so that by the time of Constantine X Ducas the bureaucrats had effectively destroyed the national armies and replaced them with mercenary Normans, Germans, Patzinaks and Armenians.

83 Coin of Isaac Comnenus, sword in hand - indicating that the imperial crown was his by right of the sword

124

![]()

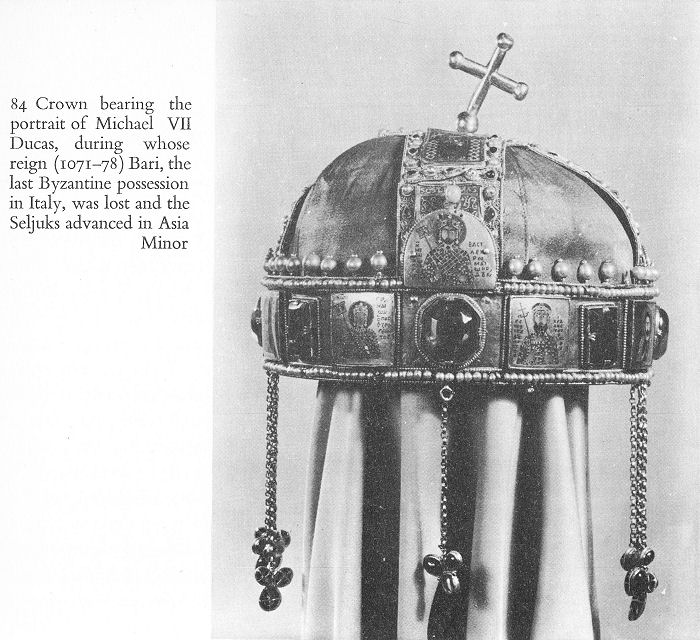

84 Crown bearing the portrait of Michael VII Ducas, during whose reign (1071-78) Bari, the last Byzantine possession in Italy, was lost and the Seljuks advanced in Asia Minor

This return to mercenary armies was a serious weakness which played a significant rôle in the collapse of the state. The loyalty of the mercenaries extended only as far as their cash subsidy, but the empire fell on hard times and more often than not the subsidies were not forthcoming. The foreign troops then began to victimize the empire they had been hired to protect, plundering the inhabitants and in some cases attempting to carve out states of their own. The hostility between the bureaucrats and soldiers found expression in the literature of the times. Cecaumenus, a rough, wily soldier who wrote in the vernacular rather than the cultivated language of a Psellus, admonished his son: ‘Do not wish to be a bureaucrat, for it is not possible to be both a general and a comedian.’ Another chronicler, writing of the reign of Michael VII and his teacher Psellus, was equally sarcastic:

125

![]()

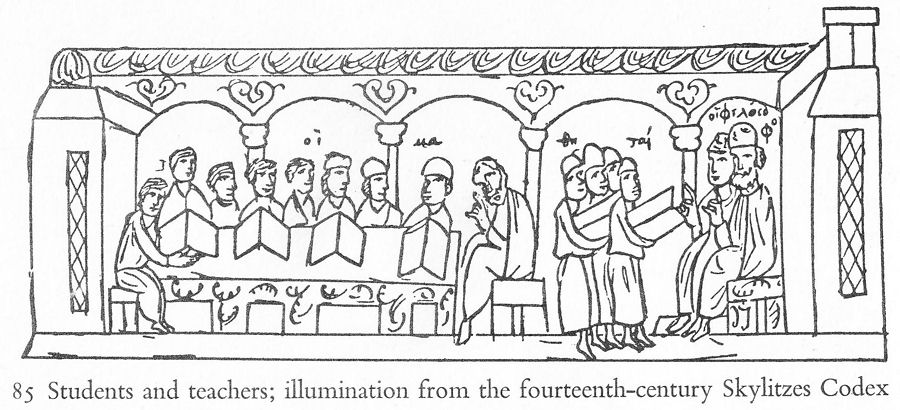

85 Students and teachers; illumination from the fourteenth-century Skylitzes Codex

[Michael Ducas] busied himself continuously with the useless and unending study of eloquence and with the composition of iambics and anapaests; moreover he was not proficient in this art, but being deceived and beguiled by the consul of the philosophers [Psellus], he destroyed the whole world.

The imbalance between sword and pen ranks foremost among the causes which led to the collapse of the Byzantine empire.

3. SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGES

Side by side with this rise of the generals there was a certain 'feudalizing' of the empire's society, for the generals were simultaneously owners of vast landed estates with large armed retinues of their own. The fusion of the landed magnate with the strategos was complete by the early tenth century and the generalship of an Anatolian province became virtually hereditary in families such as those of Scleras, Phocas and Argyrus. The expansion of these families' land-holdings and the growth of population in the provinces created a great land hunger in the tenth century which endangered the free communities of peasant land-holders. Though Byzantium's economy was based on a cash currency and men often became wealthy in shipping and industry, the principal form of investing capital was the purchase of land. In the case of the aristocrats this propensity for acquiring land was further stimulated by the fact that the government had excluded the upper classes from many business enterprises.

126

![]()

As the expansion of this class threatened to devour the free peasants the emperors issued a series of vigorous laws which attempted to halt this process and to stabilize agrarian relations between the two classes. Romanus I Lecapenus, who promulgated the first of these decrees, realized that the disappearance of the free villagers would undermine the entire fiscal, military and social foundations of the empire. He and succeeding emperors ordered the return of the land to the peasants, but the very frequency of these laws is clear proof of their ineffectiveness. It could not have been otherwise, for their implementation was often in the hands of the very class against which they were directed. The danger which such a landed aristocracy presented was made abundantly clear in the rebellion of Phocas and Sclerus against Basil II. The size of the magnates’ possessions was so enormous that Eustathius Maleinus, for example, could entertain Basil II with his army for an extended period of time.

Upon the death of Basil the last restraint on the magnates vanished and in the course of the eleventh century they effectively (though not completely) eliminated the free peasantry. It was upon the magnates that the general-emperor Alexius Comnenus, who succeeded in 1081, based his government. The result was that the army passed under aristocratic control. Already in the mid-eleventh century the emperors had begun to grant state properties in usufruct to those who had performed important services to the state. Such grants, known as pronoia, became the basis of military service under Alexius. The transformation of the pronoia into something comparable to the western fief created a military landowning society in Byzantium which differed from that of the Latin west only in that the elements of homage and sub-infeudation were missing. It is true that the emperors retained control o^er the pronoia system for a long time. But eventually it became decentralized, and when the Latins conquered the empire in 1204 the Greek aristocracy in many places recognized in the Latin barons and fiefs the counterparts of the Byzantine archontes and pronoiai.

The Macedonian expansion had once more brought large ethnic groups within the empire’s borders without being able to absorb them culturally.

127

![]()

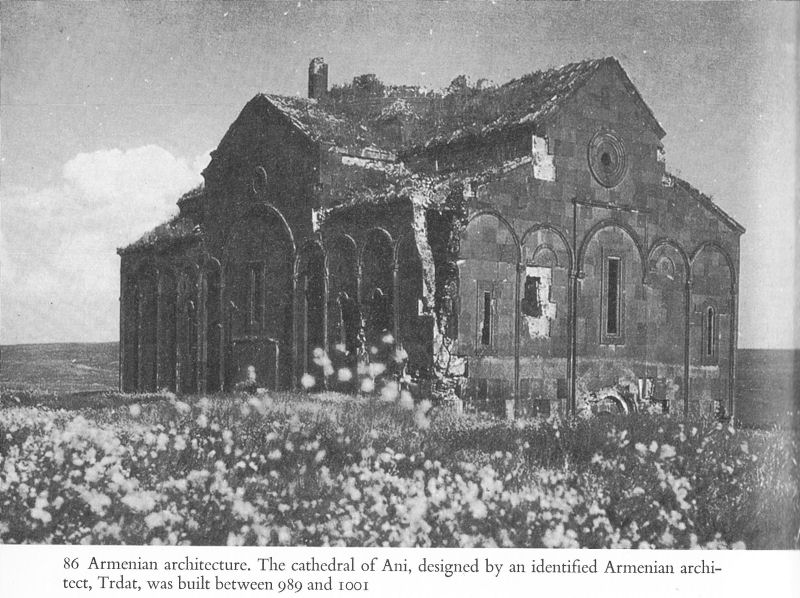

86 Armenian architecture. The cathedral of Ani, designed by an identified Armenian architect, Trdat, was built between 989 and 1001

Basil’s conquest of Bulgaria had culminated in the subjugation of the land, but even so there were a few rebellions on the part of the Bulgarians during the eleventh century. Further south there was an unsuccessful rising among the Vlachs in Thessaly during the reign of Constantine X, though this does not seem to have been motivated by ethnic considerations. More serious, however, were the ethnic problems which the emperors encountered in eastern Anatolia, for large numbers of Armenians and Syrians inhabited the regions which the Macedonian dynasty conquered. Moreover, the emperors colonized those areas which the Muslims vacated, such as Melitene and Cilicia, with Armenians and Syrians as well as Greeks. In the eleventh century the Turkish raids also drove large numbers of Armenians into Byzantine territory with the result that a large Armenian element settled in Cappadocia side by side with the Greeks.

128

![]()

The presence of these new elements raised problems for the state not only because the Armenians retained their political and military institutions, forming a state within a state but also because both the Armenians and Syrians were Monophysites. The principal measure by which the empire attempted to absorb these new elements was ecclesiastical union, a policy which had failed to integrate the non-Greek elements of the east in the sixth and seventh centuries and which now failed again with tragic results. The main effort to bring about union took place in the reign of Constantine X Ducas (105967). First the Syrians were summoned to Constantinople, but when their ecclesiastical leaders refused to agree to union they were exiled. In 1065 h was the turn of the Armenian clergy and princes. Though for a moment it seemed as if the negotiations would succeed, in the end Kakig Bagratouni, the former king of Ani, refused to give his consent. But although the Armenians, in contrast to the Syrians, were allowed to return to eastern Anatolia, Kakig declared war on the Greek clergy and population and slew the archbishop of Caesarea. It was his intention to desert to the Turks, but he was slain by the Greeks before he could do so.

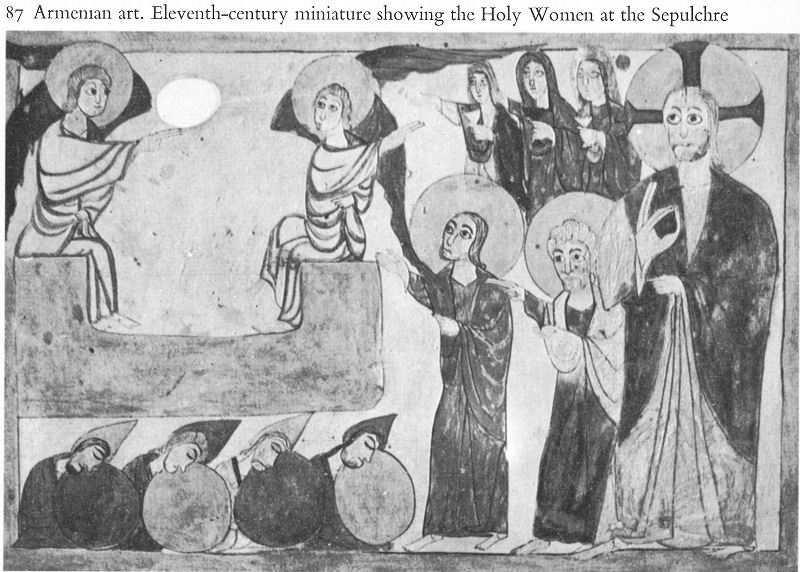

87 Armenian art. Eleventh-century miniature showing the Holy Women at the Sepulchre

129

![]()

A few years later the Greeks of Sebasteia complained to Romanus IV that they had suffered more from the Armenians than from the Turks, and the emperor had to exercise great caution in these areas lest they should attack his armies. The old Monophysite problem emerged once more, as it had in the seventh century, to threaten the security of the empire. The council of 1605 which so exacerbated relations between Monophysites and the Orthodox had a much more immediate and important effect upon the political fate of Byzantium than did the schism of 1054 between Greeks and Latins. The former played a critical part in the Turkish conquest of Anatolia; the latter became important only in the twelfth century and then partly as a result of the loss of Anatolia.

A growing economic illness, the basic cause of which are not clear, greatly complicated the empire’s difficulties. To what degree the growth of monastic and private estates reduced state revenues in the eleventh century it is difficult to say, but doubtless it played a growing role. There seems to have been considerable mismanagement of state finance after the death of Basil II due to the prodigality of emperors and empresses while the growth of the mercenary units in the army further strained the imperial purse. But perhaps the most serious decline in revenues arose as the Patzinaks and Seljuks raided the provinces and rendered them unproductive. If the causes of the economic decline are not clear their manifestation in the coinage is evident enough. From its institution by Constantine I until the early eleventh century the Byzantine gold solidus had undergone very little change, remaining stable for seven hundred years. In the first half of the eleventh century it suffered a growing debasement until by 1080 it contained only a very small percentage of gold. In a centralized state which relied upon money to support its military and bureaucratic structures the financial collapse was of course very serious.

4. THE EXTERNAL THREAT

As these developments undermined the empire, new peoples appeared on the far-flung borders and advanced while the empire progressively weakened.

130

![]()

Basil II had contemplated the reconquest of Sicily from the Arabs, but he did not live long enough to carry out his plans. The victorious campaigns of George Maniaces, which temporarily brought Syracuse and eastern Sicily under Byzantine authority, might ultimately have succeeded had the persecution of the military by the bureaucracy in Constantinople not caused Maniaces to rebel in 1043. This Byzantine general had, significantly, employed Norman mercenaries during his Sicilian campaigns.

Sixteen years later the Norman adventurers, under the leadership of Robert Guiscard, began to establish themselves as an independent power in the Byzantine lands of southern Italy. The political instincts of the Scandinavians, who had already intervened in Russia, France and England, made the Normans the most dangerous of all mercenaries and by the latter half of the century they threatened the Byzantine empire from within and without.

In the north the nomadic peoples of the Altai once more cast their shadow upon the Balkan provinces for the Patzinaks, a Turkic people who had played an important part in Byzantine diplomacy, crossed the Danube in 1048 and began to raid the empire. Constantine Monomachus eventually gave them lands in the Balkans where they were to exercise the function of border troops, and much to the disgust of the bureaucrats he raised the Patzinak chieftains to the rank of senators. The disturbances which they caused greatly increased when another Turkic people, the Uzes, invaded the Balkans as they sought to flee from the Cumans. Their depredations spread death and destruction so widely that the inhabitants seriously thought of evacuating the Balkan peninsula.

The most important of these nomadic peoples were the Seljuk Turks who began to plunder Anatolia in the first half of the eleventh century. The Seljuks, so named after an eponymous ancestor, were descended from the Oguz Turks who had established a great empire in Mongolia during the sixth, seventh and eighth centuries. After the break-up of this state various Turkic tribes moved westwards along the Russian steppe to the Balkans, or south of the Caspian to the borders of the Islamic world. The Patzinaks and Uzes are representatives of the Turkic peoples who followed the more northerly route, the Seljuks of those who followed the route to the Muslim lands.

131

![]()

Converted to Islam in the tenth century, the Seljuks entered the eastern lands of the Islamic peoples as the mercenaries of warring states. Under the leadership of Toghril they established a great kingdom in Persia and revived the caliphate at a time when it was very weak. The power of the Seljuk sultans derived from their nomadic Turkish tribes, but once the sultans had established themselves as the rulers of much of the Middle East the recalcitrant tribesmen were too difficult to control. Therefore they were shunted to the borders of the B yzantine empire where their bellicose nature and desire for booty could be satisfied at the expense of the Christian foe. Muslim authors bear ample testimony to the fear which those nomads inspired in the sedentary society of Islam, one Persian official even advising that the thumbs of the Turks should be hacked off so that the nomadic horsemen might not draw their dreaded bows.

5. THE CRISIS OF 1071

In 1071 the deteriorating internal and external conditions very nearly destroyed the empire. This was the year when Bari, the last Byzantine possession in Italy, was lost, thus ending the centuries of Byzantine domination in southern Italy, while at the other end of the empire the Seljuks defeated Romanus IV at the battle of Manzikert and began the conquest and settlement of Anatolia. This process, which was to last four hundred years, marks one of the great turning points of world history, since it was the basic factor in the transition from the Byzantine to the Ottoman empire. Romanus IV (1067-71), a representative of the Anatolian generals, had successfully plotted to gain the throne with the intention of rescuing the empire from the wretched state to which Constantine Ducas had brought it. His vigorous military expeditions against the Turks in Anatolia were the last glimmer of the warrior traditions of Basil II, but Romanus was too late. The armies which served him were composed largely of unreliable mercenaries, and the plots of Psellus with the Ducas family effectively frustrated his undertakings.

When in 1071 Romanus set out for his third Anatolian campaign, the progress of his journey was marred by ill omens at every stage.

132

![]()

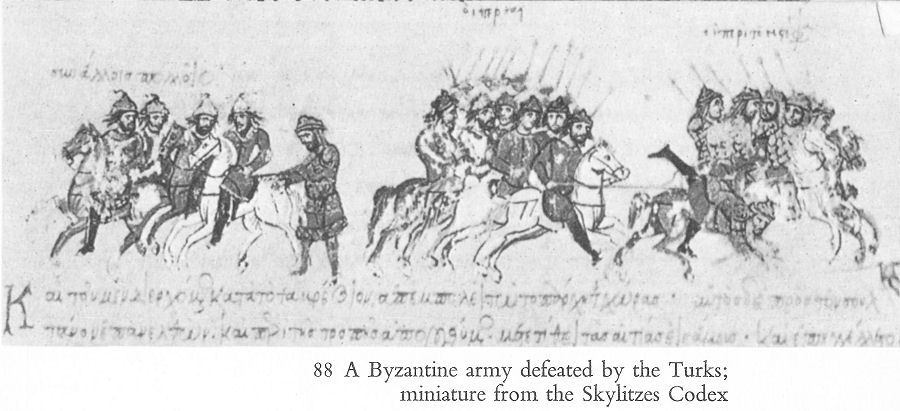

88 A Byzantine army defeated by the Turks; miniature from the Skylitzes Codex

First the imperial tent collapsed; then a fire consumed the royal stables; the Greeks of Sebasteia complained to him of Armenian treachery; on another occasion his foreign mercenaries attacked him; and finally his forces marched past a battlefield on which lay the bleached bones of a previously defeated Byzantine army. Romanus divided his forces into three groups, with one of which he encamped by the city of Manzikert in the vicinity of which, unknown to the emperor, were the forces of the Seljuk sultan, Kilij Arslan. The battle which ensued was a military accident. Neither ruler was aware of the presence of the other, and Romanus had fatally divided his forces. Even after the scouts on both sides had informed their rulers of the situation the battle could have been avoided, for Kilij Arslan asked the emperor for peace. Romanus, however, decided that he must settle the Turkish issue once and for all, for the Turks were elusive and it was hard to come to grips with them.

The events of the battle reflect only too accurately the evils which plagued the empire. The Armenian soldiers, as a result of religious animosity, deserted en masse on the field of battle, as did a small body of Patzinaks. But the most important factor in the Byzantine defeat was the premeditated desertion of the general Andronicus Ducas, nephew of Constantine X Ducas and a leading personality in the bureaucratic faction. He had decided to secure the future of his family (Romanus had exiled his father) and as commander of the rear-guard he spread the false rumour that the emperor had been defeated, and retired from the battle with his forces.

133

![]()

His withdrawal spread panic throughout the Byzantine army, and the emperor was taken captive and brought before the joyous sultan who treated him with honour.

Adronicus returned to Constantinople with news of the defeat and the bureaucratic faction proceeded to the coronation of Michael VII Ducas. Kilij Arslan had in the meantime released Romanus and the existence of two rival emperors plunged the empire into civil war just at the moment when Turkmen tribes began to enter Anatolia unopposed. During the next ten years the quarrelling bureaucrats and generals bid against each other for the services of the Turkmen chieftains in the civil strife, handing many towns over to Turkish garrisons and ensuring the success of the Turkish occupation. The loss of Anatolia to the Turks was to prove fatal to the empire, for without its rich provinces Constantinople remained a huge head deprived of the body needed to sustain it.

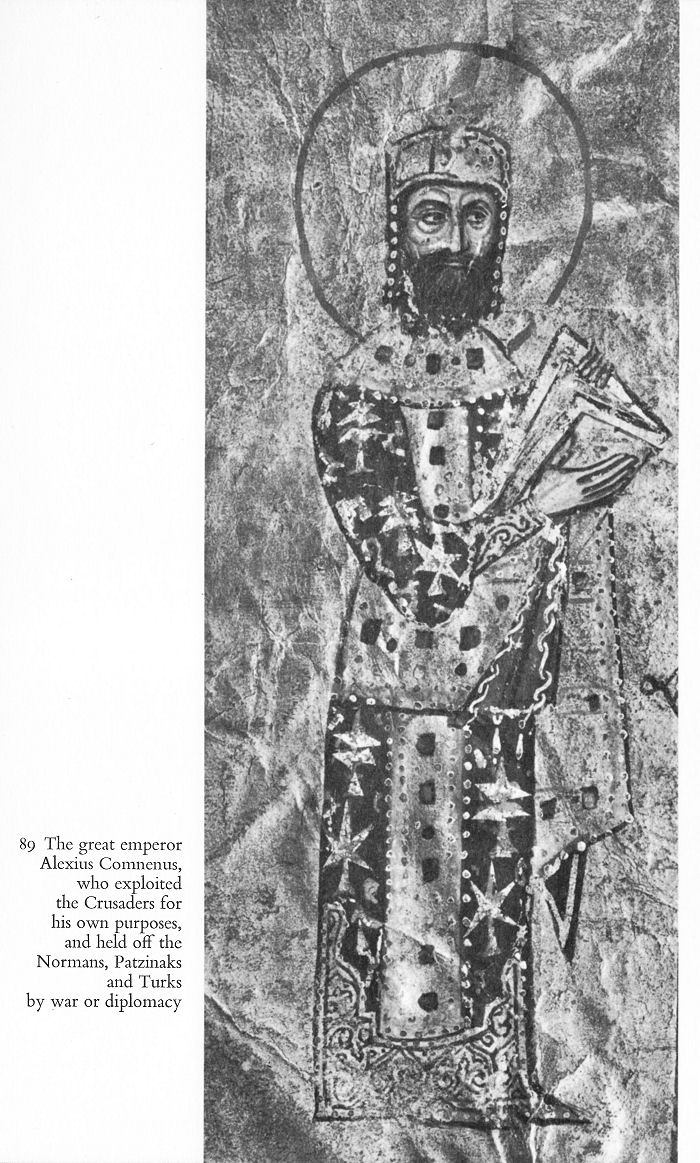

6. REVIVAL UNDER ALEXIUS I COMNENUS

When Alexius Comnenus ascended the throne he possessed an empire reduced to such pitiful straits that its days seemed numbered. That the empire was saved and its life prolonged another three and a half centuries is a remarkable testimony to the qualities of this soldieremperor. The Comnenoi not only saved the empire, bringing it a last glimmer of greatness, but they managed to do this with resources which were marginal at best, for Anatolia was largely lost to the Turks. No sooner had Alexius donned the imperial purple than he was faced by a Norman invasion which could easily have delivered the knock-out blow. By now Robert Guiscard had consolidated his hold on southern Italy, and decided to conquer Constantinople, for the Normans had undergone a certain measure of Byzantinization following their conquest of the former Byzantine province. The Norman rulers eventually adopted the Byzantine autocratic style in their architecture, representation on coins, etc. Meanwhile, Norman society in southern Italy was remarkably rich, drawing on Greek, Lombard and Arab elements. The Norman chancellery and coinage were trilingual, and this cultural pluralism manifested itself in practically every facet of society.

134

![]()

89 The great emperor Alexius Comnenus, who exploited the Crusaders for his own purposes, and held off the Normans, Patzinaks and Turks by war or diplomacy

135

![]()

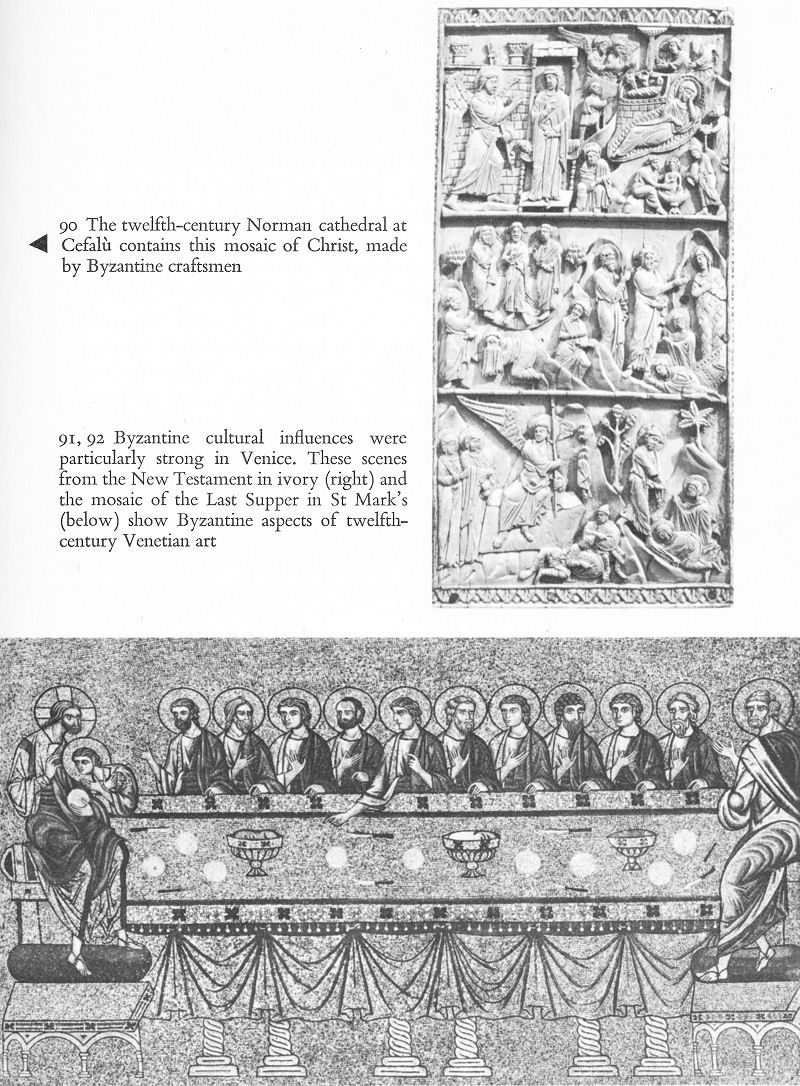

90 The twelfth-century Norman cathedral at Cefalu contains this mosaic of Christ, made by Byzantine craftsmen

The appearance of the Normans in Italy and the attempt of Guiscard to control both sides of the entrance to the Adriatic Sea greatly alarmed Venice which found its growing maritime power threatened. In consequence the Venetians were glad to accept Alexius’ proposal for an alliance against the Normans, particularly as the desperate need of the empire for naval assistance led Alexius to grant the Venetian merchants those formidable commercial privileges in the empire which lay at the basis of the rise of Venice’s commercial empire. Nevertheless, the Byzantine maritime city Dyrrachium, the starting point of the Via Aegnatia, fell to Guiscard in 1081 in spite of Venetian aid, and the advance of the Normans seemed irresistible. But a sedition, stimulated by Byzantium, forced Guiscard to return to Italy in 1082, and this diversion enabled the imperial forces to retake Thessaly, while Dyrrachium fell to the Venetians. The death of Guiscard (1085) provided Alexius with a badly-needed respite, for by 1090-91, the Patzinaks, allied with the Turkish emir of Smyrna, were attacking Constantinople by land and sea.

136

![]()

91, 92 Byzantine cultural influences were particularly strong in Venice. These scenes from the New Testament in ivory (right) and the mosaic of the Last Supper in St Mark’s (below) show Byzantine aspects of twelfthcentury Venetian art

137

![]()

The crisis was acute, but fortunately Alexius, having secured the alliance of the Cumans, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Patzinaks at Mt Levounion in an action which resulted in the almost complete extermination of these nomads. The emperor had weathered the worst of the storm. Alexius could now pause to marshal his strength for the reconquest of Anatolia where the various Turkish chieftains were quarrelling with one another.

The emperor’s plans were suddenly jolted when the advance elements of the First Crusade made their way through the Byzantine provinces to Constantinople. At an earlier date Alexius had appealed to the west for aid, but he had envisaged restricted numbers of mercenaries rather than the formidable crusading hosts which had been roused by Pope Urban’s preaching at the council of Clermont. In this new confrontation between east and west the differences to which Liudprand had earlier referred soon became painfully evident. Constantinople and Rome, the heirs of the Greeks and the Latins, developed from two different cultures, and historical forces had accentuated their basic differences over the centuries. In the absence of a powerfully organized and centralized state, the papacy had acquired considerably greater freedom of action and political power than had the Greek patriarchate, which was prevented by the existence of a strong secular power in Constantinople from executing the same ambitious policies as its western counterpart.

Friction between the two Churches existed from the fourth century, and as the centuries passed the differences accumulated. The Monophysite problem had resulted in the Acacian schism between pope and patriarch in the fifth century. Later, at the time of the Iconoclastic controversy, Leo III not only alienated the papacy by his proscription of images, but also proceeded to transfer Illyricum and southern Italy from papal to patriarchal jurisdiction. This combined with the Lombard pressures to turn the popes from the Byzantines to the Carolingians - a fateful step. The conversion of the south Slavs, begun under the patriarch Photius, once more led to a temporary break in relations between Rome and Constantinople. By 1024, however, there seems to have been an agreement between the heads of the two Churches that each should be supreme in its own

138

![]()

sphere, but the Cluniac movement had the effect of rejuvenating the papacy, providing it with a new élan. From the time of Pope Leo IX this new reformatory trend spread rapidly, and wherever its representatives went they enforced a stricter subservience of spiritual life to the papacy. As papal influence spread into the Byzantine regions of southern Italy it encountered resistance from the Greek Church. Finally, the presence of ambitious clerics on the thrones, of Rome and Constantinople furnished the spark which ignited the explosive differences separating the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. Pope Leo IX sent the haughty Cardinal Humbert as head of a legation to present the papal point of view to the patriarch Cerularius, who was himself one of the most powerful men ever to hold the patriarchal office. Cerularius displayed an equally imperious temper in handling both emperors and popes and the controversy between the two Churches quickly came to a head. It focused upon minutiae of dogma and ritual - celibacy of the clergy, the use of unleavened bread in communion, fasting on the Sabbath, and the famous clause filioque - all concrete points which the popular mind could readily grasp. The intransigence of both sides culminated in 1054, when Humbert arrogantly placed an excommunication of Cerularius on the altar of Hagia Sophia, and Cerularius in turn excommunicated Humbert and his retinue. Though there were no immediate consequences, the schism of the two Churches formalized the differences of east and west, and the political complications of the twelfth century arising from the Crusades soon gave real substance to this religious schism. It is only in the present generation that the Orthodox and Catholic Churches have agreed to withdraw the maledictions they hurled at one another over nine hundred years ago.

The Crusading mentality was coloured by the effect of these religious and cultural differences. Even in the First Crusade, which of all the Crusades was the one most nearly ‘pure’ in motivation, worldly considerations were present. The Italian cities observed the movement through the eyes of the greedy merchant, while the Normans intended to exploit the Crusade to acquire new lands and victories at the expense of Byzantium. Alexius, faced with the presence of powerful western armies, decided to use them to reconquer what he could of Anatolia.

139

![]()

93 The battle of Dorylaum, where Byzantines and Crusaders defeated the Seljuks. This victory enabled them to invade Cilicia (1104)

In 1096-97 the Crusading leaders gathered in Constantinople where the emperor finally persuaded them to swear an oath, agreeing that all lands formerly belonging to the empire which they might conquer would be returned to Alexius.

140

![]()

In return the emperor would support the westerners in their march.

The bargain which the emperor had struck bore fruit when the defeated Turks surrendered Nicaea to the Byzantines. Shortly thereafter Byzantine forces drove the Turks from the entire western region of Anatolia, but the apparent harmony of Greeks and Crusaders was smashed when Bohemund claimed the city of Antioch for himself in 1098. The Byzantine reconquest of Cilicia (1104) brought Graeco-Norman antagonism to a head once more, and Bohemund, playing upon religious differences, spread propaganda stories that the Greeks had betrayed the Crusade and prepared to invade the empire from the west. This time, however, Alexius was in an entirely different situation from that in which Guiscard had found him in 1081. Bohemund was defeated in western Greece and forced to surrender, ignominiously agreeing to hold Antioch as a fief bestowed by the emperor. Though Alexius had successfully thwarted Norman efforts to destroy the empire, the Norman heritage was to remain a bitter one for the Byzantines throughout the twelfth century, culminating in the Norman sack of Corinth, Thebes, and Thessalonica.

7. ALEXIUS’ SUCCESSORS

After thirty-seven arduous years as ruler Alexius had greatly strengthened the empire and restored its glory, having found Byzantium virtually destroyed, deprived of its fairest provinces, and with the foes at the door. Through sheer ability he defeated the Normans, destroyed the Patzinaks, exploited the Crusaders, and forced the Turks to retreat. The position of the empire at his death, however, was not that which it had been a century earlier, for unfortunately the reconquest of Anatolia had been incomplete, leaving the central plateau in the hands of the Seljuks, and the defeat of Guiscard had been made possible by the commercial immunities that Alexius gave the Venetians in order to secure their assistance. The inheritance of John II and Manuel I Comnenus was thus an ambivalent one, compounded of empty glory and unpleasant reality. Though it is true that Venice had developed an efficient maritime enterprise by the eleventh century, it was the concessions which it acquired in 1082 that established the basis for its commercial empire and marked the start of Italian encroachment on the empire’s economic life.

141

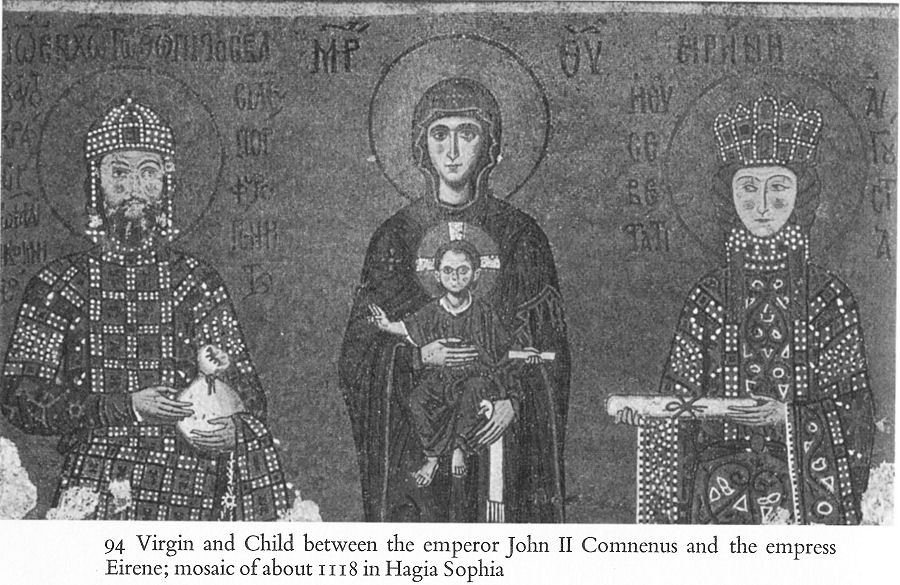

![]()

94 Virgin and Child between the emperor John II Comnenus and the empress Eirene; mosaic of about 1118 in Hagia Sophia

The emperors made repeated but unsuccessful efforts to throw off this stranglehold, but in the end the western merchants were like parasites devouring the empire’s strength.

Alexius had granted Venetians the right of trading in the ports of the empire duty free, a concession which put them far beyond competition from Byzantine merchants, who were still required to pay the formidable array of commercial taxes. The unfortunate result was not only that the carrying trade passed from the hands of the Greeks into the hands of the Venetians, but a rich source of revenue was forever alienated from the empire’s treasury. Alexius further allotted the Venetians a quarter in Constantinople and three quays with warehouses on the Golden Horn for their ships and merchandise. To the large numbers of western mercenaries who had previously come to Byzantium there was thus added a new influx of Latin merchants whose numbers in twelfth-century Constantinople would eventually attain tens of thousands.

142

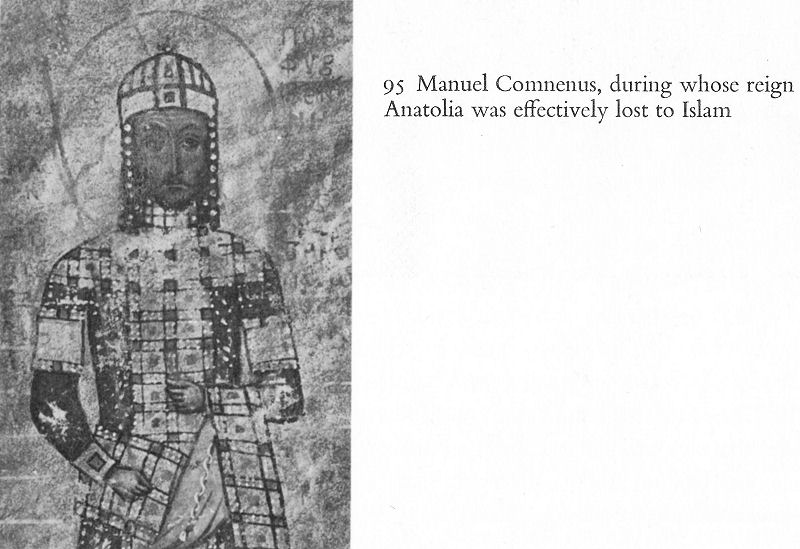

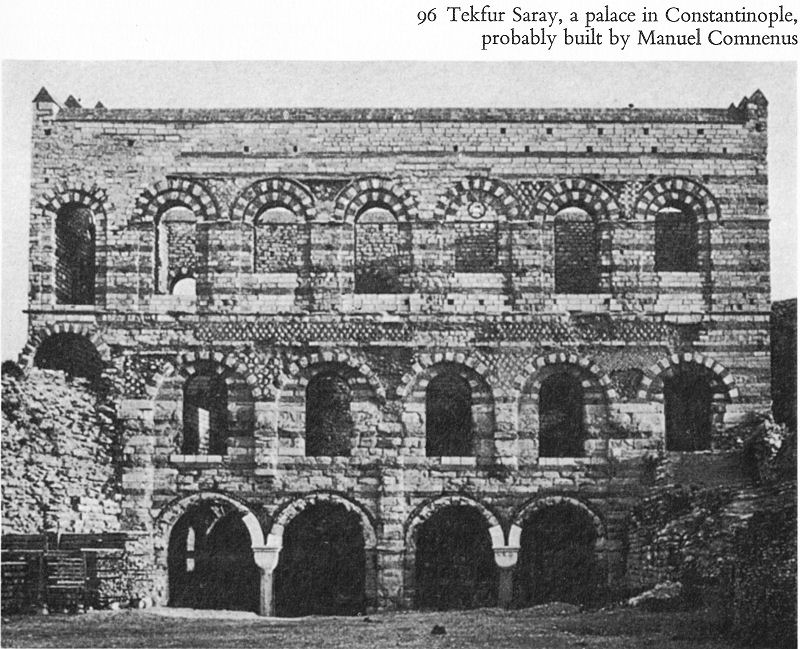

![]()

95 Manuel Comnenus, during whose reign Anatolia was effectively lost to Islam

96 Tekfur Saray, a palace in Constantinople, probably built by Manuel Comnenus

143

![]()

The fierce competition of Venice’s rivals, coupled with Byzantine fear of an exclusive Venetian commercial monopoly within the empire, led to the granting of similar privileges to Pisa and Genoa as the emperors attempted to play one Italian city off against another.

John II Comnenus attempted to strike a balance between Turkish affairs in Anatolia and the affairs of the west, and he not only consolidated the Anatolian gains of his father but extended them at the expense of the Seljuks. The accession of the more flamboyant Manuel, however, upset this balance, largely because he was hypnotized by the west. He surrounded himself with Latins, adopted Latin customs (he loved to participate in western jousting tournaments), and took as his second wife a Latin princess. He became so deeply engrossed in Italian and German politics that he neglected the defence of the Byzantine Anatolian provinces, allowing Kilij Arslan to eliminate his Danishmend rivals and to make the Seljuk power once more a serious threat. Finally realizing the drastic changes that had taken place in Anatolia, Manuel set out with his armies to attack the Seljuk capital of Konya (ancient Iconium) in 1176.

As the Byzantine armies moved from western Anatolia into the mountain passes leading to the plateau they suffered continuous harassment from the numerous Turkmen tribes that lived on the borders between Seljuks and Greeks. Having arrived in the Phrygian pass of Myriokephalon, Manuel’s army suddenly found itself surrounded and the battle that followed was another Manzikert for the Byzantine soldiery, which suffered disaster in this critical encounter. The fighting was obscured by a raging sandstorm during which the slaughter of friend and foe became indiscriminate but after the defeated emperor accepted Kilij Arslan’s terms it became evident that in spite of their victory the Turks had also suffered heavy loss. The retreating Byzantines saw large numbers of dead whose facial skin and genitals had been removed by the Turks so that the Greeks would be unable to recognize the extent of the casualties which the Muslim Turks had suffered. Nevertheless, after this defeat the Byzantines renounced any hope of driving the Turks from Asia Minor and during the remainder of the twelfth century the Turkmen tribes, following the rivers from their sources in the mountains to

144

![]()

their outlets in the Aegean, mercilessly devastated the regions which the Comnenoi had so meticulously recolonized.

In the west, Serbs and Bulgars took advantage of the chaos which enveloped Byzantine political life in the last quarter of the twelfth century to establish their independence, and Frederick Barbarossa could count on the support of both the Anatolian and Balkan foes of the empire as he marched through these regions on the way to the Holy Land. The degeneration of the empire’s relations with the west carried over into the relations between the Latins and Greeks of Constantinople. Manuel, having previously concluded alliances with Pisa and Genoa, decided to strike at the Venetians within the empire, and on 12 March 1171 all Venetians in the empire were arrested and their ships and goods confiscated.

The affluence of the Venetians in Byzantium had created an intolerable situation and finally led to the breach between the empire and the republic. So oppressive was the economic hegemony of the Latins in Constantinople that the inhabitants of the capital sided with Andronicus when he marched on Constantinople in 1183 to seize power from Alexius II and his Latin mother. The riots which broke out in the streets culminated in a brutal attack upon the lives and property of the Latins in the city. There is no doubt that the events of 1171 and 1183 constitute an important landmark leading to the Latin conquest of the city in 1204. The Venetians had extorted the maximum in official concessions and commercial profit, in order to protect and increase their gains; all that remained was military conquest of Constantinople. It seemed momentarily that the Normans would anticipate the Venetians in this respect for they took the city of Thessalonica by storm in 1185 and subjected the inhabitants to merciless treatment. Though the Norman advance on Constantinople was halted, the fate of Thessalonica constituted both revenge for the massacre of the Latins in 1183 and a foretaste of what would happen to the Greeks in 1204.

8. FLOWERING OF THE ARTS

The era of the Comnenoi and Angeloi, an era of political decline, was nevertheless one in which the arts, especially literature, flourished.

145

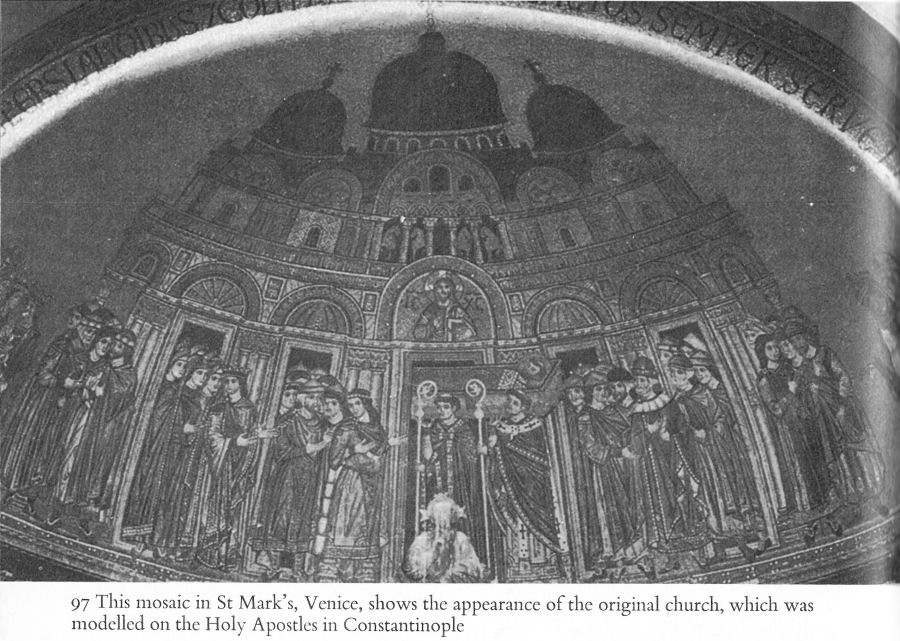

![]()

97 This mosaic in St Mark’s, Venice, shows the appearance of the original church, which was modelled on the Holy Apostles in Constantinople

Though artistic activity, because of less favourable political and economic factors, was not as extensive as under the Macedonians, Byzantine influence is to be seen in the art of Kievan Russia, Venice, Norman Sicily and the Holy Land. It is perhaps not the least remarkable phenomenon of the late empire that its political degeneration was accompanied by increased literary output and by the high quality, if not quantity, of artistic production. This is in itself an interesting commentary upon the supposed interrelationship between political success and cultural flowering which historians often presuppose.

In contrast to its political fortunes, the literary life of the empire under the Comnenoi and Angeloi represents both continuity with 146 and intensification of the literary life which had developed in the eleventh century.

146

![]()

98 Byzantine art exercised a profound influence over the art of Kievan Russia, particularly through this icon, the Virgin of Vladimir, painted in Constantinople about 1125 and subsequently taken to Russia

147

![]()

Even more than their Macedonian predecessors the scholars and writers of the twelfth century studied and imitated the classical authors, though the traditional religious literature also remained a constant element in the Byzantine cultural picture. It is true that the Church condemned John Italus for daring to equate philosophy with theology, but on the other hand the two greatest classical scholars of the time were archbishops. The erudition of Eustathius of Thessalonica, evident in his voluminous commentaries on the Homeric and Pindaric texts, constitutes a monument in the history of Greek scholarship and the aesthetic receptivity of these cleric-scholars to Greek poetry is clearly stated in the very first line of Eustathius’ Homeric commentary. ‘If anyone wishes to escape the power of Homer’s Sirenes perhaps it would be a good thing for him to smear his ears with wax in order to avoid bewitchment.’

f

Eustathius’ house in Constantinople had become a school in which he educated young men in the classics, his most cultivated student being the future archbishop of Athens, Michael Acominatus. This infatuation with the rich literary testament of the Greeks was an integral element in the Byzantine feeling of cultural superiority over the rest of the world. Anna Comnena repeatedly apologizes for defiling her history with names and words of barbarian origin, whereas Michael Acominatus is a medieval forerunner of those modern classicists who make their pilgrimages to the Acropolis and simultaneously berate contemporary Athenians for lacking the physical and intellectual qualities of Apollo and Plato. An Anatolian disciple of cultural Hellenism born in Phrygia, Michael journeyed to Athens to take up his episcopal duties there and greatly looked forward to his stay among the descendants of Pericles. But it soon became obvious to him, as he preached to the congregation in the Parthenon (now a church dedicated to the Virgin), that the Athens of Pericles was no more. His existence was none the less a pleasant one in contrast to that of another learned archbishop. Theophylact, who had studied at the feet of Psellus, suffered a veritable exile when appointed to the archbishopric of Ochrid in the mountains of the western Balkans. Of what use was literary culture when one was condemned to an audience of croaking frogs and stupid peasants?

148

![]()

The vernacular tongue, as well as classical Greek, found its exponents, and both types of language were employed to relate the sad state of Byzantine society. In spite of the influence of the language and spirit of the great pagan historians, the twelfth-century historians of Byzantium were anything but indifferent to the political and military realities of their time. Far from the spirit of antiquarianism, which preoccupation with classical antiquity so often inspires, Anna Comnena describes in bold strokes the military prowess of the Normans and Latins, filling out her story with detailed observations on Latin superiority in military technology. The historian Choniates stated, without apology, that the chaos of the late twelfth century in parts of Byzantine Anatolia was such that many Greeks preferred to live under the Sultan.

These historians trace the empire’s misfortunes clearly and objectively. The poets of Constantinople, though dependent on their tight-fisted patrons, could write social satire as readily as platitudinous encomia, and obviously did so with greater pleasure. Typical was John Tzetzes who recorded some of the flavour of life in Constantinople during the twelfth century. To him Constantinople, perhaps because of its cosmopolitan character, was a city of evil in which thieves and corrupters were canonized as saints. He boasts that on the streets of Constantinople he could greet Scythian, Latin, Persian, Alan, Arab, Russian and Jew each in his own language. The most remarkable of these poets, Theodore Ptochoprodromus, used the vernacular tongue for his stinging comments on social conditions.

The same language had been used by Catacolon Cecaumenus (he notes that he has been criticized for his uneducated Greek) a century earlier in the admonitions which he addressed to his own son and to the emperor. His son is to keep his wife in seclusion lest she, and the family honour, fall victim to the wily arts of the seducer. If he desires long life, he must not keep company with physicians. The poet warns the emperor, among other things, that the employment of barbarian officials will bring evil to the empire. But the vernacular tongue received more artistic treatment at the hands of Ptochoprodromus who used it to complain of perverted social values. In his poem ‘Anathema on Letters’, for example, he relates how, in spite of long years spent in study, he is in a perpetual state of hunger.

149

![]()

Uneducated craftsmen, on the other hand, are well paid, their larders stocked, and their tables graced by fish, stews, roasts, tripe, wine, pure wheat bread and Vlach cheese, while his own pantry is filled exclusively with papers. The artisans’ retort was that the poet, who was also a priest, should either satiate his hunger with his verses or else remove his vestments and do some real work, as they did. The complaint of this literary figure that the labourer makes more money is familiarly modern, as is also the anti-clericalism of the workers.

9. THE FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE

The ills of Byzantium, apparent in this literature, so weakened the empire that by the end of the twelfth century the end was virtually inevitable. Manuel’s schemes had destroyed the strength which Alexius I and John had so laboriously nourished. The Angeloi may have been the nominal successors to the Comnenoi, but they lacked the abilities which the extraordinary position of the empire demanded.

Henry VI, inheritor of a double portion of hatred for the Byzantines (he was a Hohenstaufen who had taken Norman Sicily), had prepared an expedition against the empire which halted only because of his premature death as the fleet was about to sail from Messina in 1197. Two years later at a tournament held on the estates of Count Tibald of Champagne a fiery preacher had inspired the nobles to take the Cross, an event which was very distant from Constantinople and not at all extraordinary in terms of Crusading precedent. The knights obtained support from Pope Innocent III and began to make plans for the invasion of Egypt. With the passing of time, however, direction of the Crusade came progressively under the influence of powerful anti-Byzantine forces.

On the death of Tibald in 1201 leadership of the movement passed into the hands of Boniface of Montferrat, a man with personal interests in both the Holy Land and Byzantium and a strong individual who ended any effective control of the papacy over the Crusade.

150

![]()

A friend of the German ruler, Philip of Swabia, he visited the latter’s court and undoubtedly had some interesting conversations there. For Philip, married to Irene, the daughter of the dispossessed Byzantine Isaac II, was also host to the young son of Isaac, Alexius. The Crusaders, once arrived in Venice, were unable to raise the 85,000 silver marks which the Venetians had demanded as the price for taking the Crusaders to their destination. But the wily doge, Dandolo, had a very interesting proposition by the acceptance of which the payment of the 85,000 marks could be postponed. The Crusaders should help the Venetians to retake the Dalmatian city of Zara from the Hungarians, and in return Venice would transport the Crusaders to Egypt. The Venetians thus harnessed the Crusaders to their own selfish interests from the beginning. The Crusaders were used to attack a Christian town while only a little earlier the Venetians had entered into negotiations with the ruler of Egypt which were meant to secure Egypt against attack by the Crusaders. After the capture of Zara, Alexius and the Crusaders struck the fatal bargain by which Alexius offered to pay the Crusaders the money owed Venice in return for their aid in restoring his father Isaac to the throne in Constantinople.

The combination of Byzantine dynastic politics, German schemes, and Crusader ambitions had fallen into the hands of Dandolo who now cleverly exploited them to the maximum on behalf of Venetian interests in Byzantium. The Crusaders and Venetians entered Constantinople in the summer of 1203, Isaac was restored to the throne and Alexius crowned co-emperor. But Alexius was not able to fulfil the promises he had made the Crusaders for he lacked money and the people resisted ecclesiastical union with the Latins.

The relation of Latins and Greeks now became greatly strained. The former pillaged the Greek villages in the city’s environs and burned a portion of the city itself, and the Crusaders and Venetians, having decided to abandon the struggle against the Muslims, made an arrangement for the expected partition of the Byzantine empire.

The future emperor, whom they would elect from their own group, would receive the two palaces of Constantinople and one-fourth of the city and empire, the remaining three-quarters to be evenly divided between Venetians and Crusaders.

151

![]()

In April 1204, after Alexius V had removed Isaac and Alexius IV, the Latins attacked the city and this time their victory was complete. The emperor, patriarch, and Theodore Lascaris, along with other Greeks, fled to Asia Minor and the Balkans to organize resistance there, and the Latin soldiery subjected the greatest city in Europe to an indescribable sack. For three days they murdered, raped, looted and destroyed on a scale which even the ancient Vandals and Goths would have found unbelievable. Constantinople had become a veritable museum of ancient and Byzantine art, an emporium of such incredible wealth that the Latins were astounded at the riches they found. Though the Venetians had an appreciation for the art which they discovered (they were themselves semi-Byzantines) and saved much of it, the French and others destroyed indiscriminately, halting to refresh themselves with wine, violation of nuns, and murder of Orthodox clerics. The Crusaders vented their hatred for the Greeks most spectacularly in the desecration of the greatest church in Christendom. They smashed the silver iconostasis, the icons and the holy books of Hagia Sophia, and seated upon the patriarchal throne a whore who sang coarse songs as they drank wine from the church’s holy vessels.

The estrangement of east and west, which had proceeded over the centuries, culminated in the horrible massacre that accompanied the conquest of Constantinople. The Greeks were convinced that even the Turks, had they taken the city, would not have been as cruel as the Latin Christians. The defeat of Byzantium, already in a state of decline, accelerated political degeneration so that the Byzantines eventually became an easy prey to the Turks. The Crusading movement thus resulted, ultimately, in the victory of Islam, a result which was of course the exact opposite of its original intention.