I. TRANSITION FROM ANTIQUITY AND THE EMERGENCE OF BYZANTIUM

1. Chaos of the third century 11

2. Reforms of Diocletian and Constantine 16

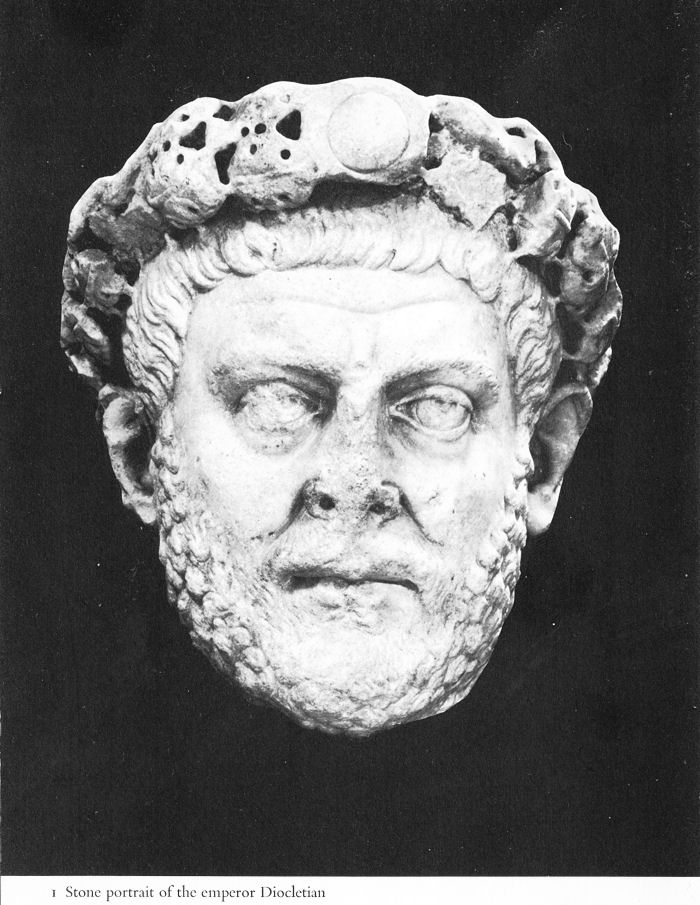

1 Stone portrait of the emperor Diocletian

1. CHAOS OF THE THIRD CENTURY

The Byzantine empire was born of the third-century crises which transformed the world of antiquity, and though the elements of continuity between the Byzantine world and the world of antiquity .ire clear and undeniable, so too are the differences. During the course ot this momentous transformation the empire lost its Latin-pagan appearance and gradually assumed a Greek-Christian form, though to be sure Byzantium, like the Roman empire, remained a polyglot, multi-national and polysectarian state during the greater part of its existence. The difficulties which the Roman empire experienced in the third century were largely the result of imperfections in the empire’s political, social and cultural institutions. It was these innate flaws, rather than the power of the barbarian nations, which prostrated the state and threatened to destroy it in the half-century which preceded the reign of Diocletian. Perhaps the single most serious defect in the whole system was the lack of a regularized imperial succession. By the third century the oft-repeated phrase ‘succession by successful revolution’, came to describe only too truly the established pattern in the accession to the throne of the Caesars.

Dynastic sentiment had failed to take root, and the emasculated senate was usually, though not always, powerless, so that the armies became the ultimate arbiters in the promotion and removal of emperors. Ambitious generals and rapacious troops combined to produce a period of short reigns and violent successions. In the half-century preceding the reign of the great reformer Diocletian there were about twenty rulers (most of whom died violent deaths) with an average reign of two and a half years. This situation had a highly deleterious effect. In so vast an empire the degradation of the ruler to the status of a tool of the armies and the accompanying

11

![]()

perversion of the military function were disasters of great magnitude. For the individual around whom the whole system revolved was divested of all respect and authority, and the armies were consumed in selfish enterprises at the expense of the defence of the frontier.

The lack of political stability undoubtedly further aggravated an economic malaise which beset the empire throughout the third century. The causes of this were far more complex than in the case of the political disturbances. The economic ills of the empire included such factors as an unfavourable balance of trade with the Orient, decreasing returns from taxation and disturbance of economic life by the increased civil strife and barbarian raids, the high incidence of the plague and depopulation, increase in the donations paid to the troops and rising administrative expenses. Government had recourse to debasement of the coinage whereby gold money virtually disappeared and silver coin was transmuted into copper money. This debasement induced a meteoric inflation with the result that society began to rely increasingly on a barter economy.

A profound transformation in the moral and spiritual life of the empire was also clearly apparent. The religions of the Greeks and Romans had exhibited their greatest vitality when the polis or civitas was still the focal point of men’s thoughts and actions. But even then the character of Graeco-Roman paganism had been more patriotic than ethical and spiritual. By the third century, at a time when municipal patriotism had been deprived of any substantial basis, Graeco-Roman paganism was largely an historical fossil which promised the individual little. The Oriental mystery cults, combining that mystery, pomp, and ceremony which so appeal to man’s emotional character, contrasted sharply with the prosaic indifference of much of Graeco-Roman paganism to man’s needs. The appeal of the eastern religions was not exclusively emotional because they also provided a rationale for living the ethical life in this world. Thus if a man shared in the cult of a particular deity and lived according to proper ethical precepts, he was assured of the reward of immortality in the afterlife. This offered further comfort to men at a time when society was coming apart at the seams, and rapacity was often as characteristic of government officials as of bandits and pillaging barbarians.

12

![]()

It has been plausibly supposed that the religions of the East became such formidable competitors to classical paganism not only because of their greater emotional and ethical appeal, but also because the cults had a superior intellectual level. With the rise of philosophy m the Greek world, knowledge had become the special preserve of the philosopher, and was divorced from religion. In the East, where the priestly classes remained a repository of both secular and religious knowledge, there was not this sharp separation between religion and knowledge. Even though it is true that philosophers did increasingly concern themselves with questions of religion, they did so on such an elevated plain that it remained beyond the comprehension of the masses.

Whatever the reasons, there is no doubt that by the third century the trickle of the Nile and the Euphrates into the Tiber had become a torrential flood, and the sects of Mithra, Christ, Cybele, the Jews, Isis and Osiris had spread throughout the empire. This dispersion or dissemination not only acted as a powerful catalyst in the religious and ethical domains, but was to have a profound effect on the political and artistic forms of the succeeding centuries. The revolution which the spread of the Oriental mystery religions effected in the world of the third century, has not attracted the attention its significance warrants. The triumph of Christianity in the fourth century obscured the importance of the third-century phenomenon in the eyes of Christian intellectuals, who were prejudiced against Christianity’s competitors.

In modern times, though scholars have appreciated the orientalization of Graeco-Roman paganism, laymen are much more familiar with the barbarian invasion from the north than with the religious invasion from the east. The barbarian penetration of the imperial borders was accompanied by wars, destruction and death, so that the phenomenon was then, and is now, more readily perceptible. Oriental religions triumphed in thousands of insignificant daily encounters, seldom accompanied by any spectacular acts. It is only at the end of this cumulative process that the effect was visible, and by then it had become such an integral part of society that it was taken for granted.

13

![]()

The internal disorganization of the empire greatly facilitated the onslaught of foreign peoples on the empire’s northern and eastern frontiers. In Europe the imperial defences along the Rhine and Danube were increasingly penetrated by the Germanic tribes. Beginning on a small scale in the reign of Alexander Severus, these raids attained major proportions by the middle of the century. Saxon pirates rendered the English Channel unsafe, while in 256 the Franks crossed the Lower Rhine, and in slightly more than a decade imperial troops were battling the raiders in both Gaul and Spain. The Alemanni crossed the Rhine in the south and reached as far as northern Italy before being halted. The most powerful of the Germanic tribes seem to have been those of the Goths who in 251 killed the emperor Decius and inflicted the most serious Germanic defeat upon the imperial troops since Varus’ legions had been destroyed in the reign of Augustus. Emboldened by their spectacular successes, the Goths not only extended their depredations to the heart of the Balkans (their allies, the Heruli, appeared before Athens in 269), but, taking to the sea, raided the coasts of the Marmara, Black, and Aegean Seas. Claudius Gothicus temporarily halted these attacks south of the Danube, but Aurelian withdrew the last Roman legion from Dacia in 270 and the Goths occupied it unhindered.

In the east the danger did not appear in the form of a new people, as it had in Europe, but in the form of a new dynasty. The Parthian state, which had arisen at the expense of the Hellenistic kingdom of the Seleucids, had by the early third century degenerated into a loosely-held congeries of vassal states. I11 the southern district of Persia arose a family of fire priests who successfully rebelled against the Arsacids and in 224-26 defeated the last Parthian ruler, Artabanus V, and destroyed the Parthian state. In 226 Ardashir, of the family of Sassan, was crowned shahanshah and a new era in the history of the Near East began, for the emergence of the Sassanids represented more than a mere change of dynasty. This neo-Achcmcnid state, which soon absorbed the former lands of the Arsacids, was a more centralized and powerful state than that of the Parthians - a fact which the Romans did not in the beginning appreciate. This new 14 monarchy represents the first stage in the process by which the Iranian people rejected the last vestiges of Hellenism.

14

![]()

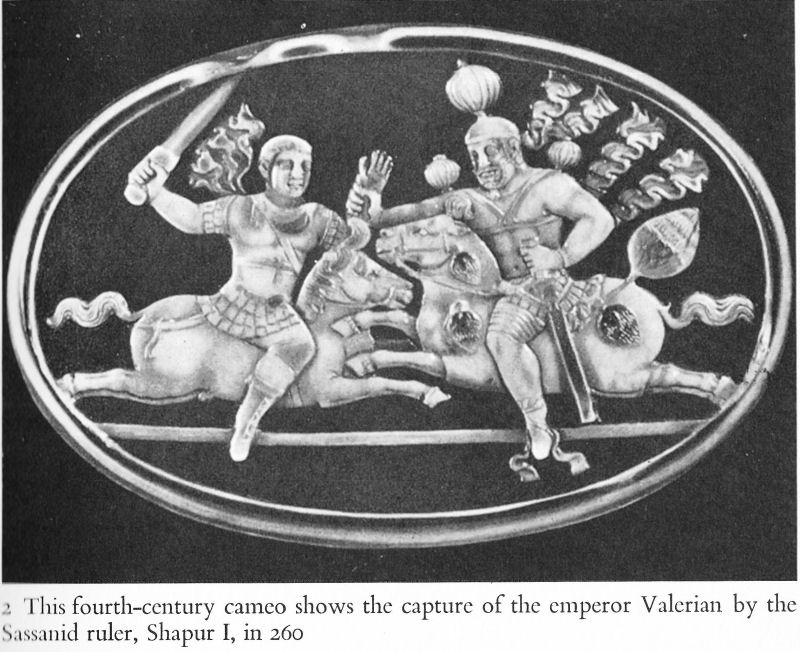

2 This fourth-century cameo shows the capture of the emperor Valerian by the Nassau id ruler, Shapur I, in 260

The establishment of Zoroastrianism as the official religion of the state, the appearance of a highly-developed hierarchical religious structure with a mobadhan mobad (a sort of Zoroastrian pope) at the apex and the establishment of a canonical text of the Avesta, were factors which gave the Sassanid theocratic state an external similarity to Byzantium. The highly stratified social structure with its rigid caste system, however, was immobilized to an extent far beyond anything Diocletian (the son of a freedman) could have conceived.

The first Sassanid rulers regarded themselves as heirs of the last Darius and desired to bring about a re-birth of the Oriental empire which Alexander and his generals had overthrown. Sassanid and Roman (and later Byzantine) armies soon clashed in the border regions of the upper Tigris and Euphrates, Syria, and Armenia. The significance of the change in dynasties became clear in 260 when Shapur I defeated the Roman armies and captured the emperor Valerian. The unexpected but timely appearance of Odenathus of

15

![]()

Palmyra and his queen Zenobia halted any further Sassanid conquests and the empire enjoyed a certain respite. Palmyra, as a traditional caravan city living from the proceeds of itinerant commerce and merchants, had become a blooming commercial centre of the typical oasis type, and its prosperity was evident in the thin veneer of Graeco-Roman culture assumed by its Arab inhabitants. By 264 the Arabs of Palmyra had defeated the Persians, restored the boundaries of the Roman empire and acquired the temporary gratitude of Rome.

Though the eastern and northern boundaries of the empire had been restored by the latter half of the century (with the exception of the withdrawal from Dacia), the pressures of Germans and Persians remained constant, awaiting the opportunity which the weakness of the empire would present in the late fourth and fifth centuries.

2. REFORMS OF DIOCLETIAN AND CONSTANTINE

It was indeed fortunate for the empire that two rulers of unquestionable ability assumed direction of affairs in these critical times. Diocletian (284-305), pre-eminent as an administrator rather than a soldier, had made his way in the Roman cursus honorum from the bottom to the very top of the official hierarchy. During these years in the imperial administration he had had ample opportunity to witness the evils besetting the state, and came to the throne rich in that experience so necessary to successful reformers. His successor Constantine, though he rose by violent means, also concerned himself with reform and his reign was in many ways complementary to that of Diocletian. The half-century of reform associated with the reigns of these two monarchs does not represent a sudden departure from the general development of the third century, for the immediate predecessors of Diocletian had already begun the task of taming the administrative, economic, and political chaos, and had attained some modest successes. But it was Diocletian and Constantine who realized the significance of the trend and brought to a successful conclusion this process of change by institutional reform on a large scale.

16

![]()

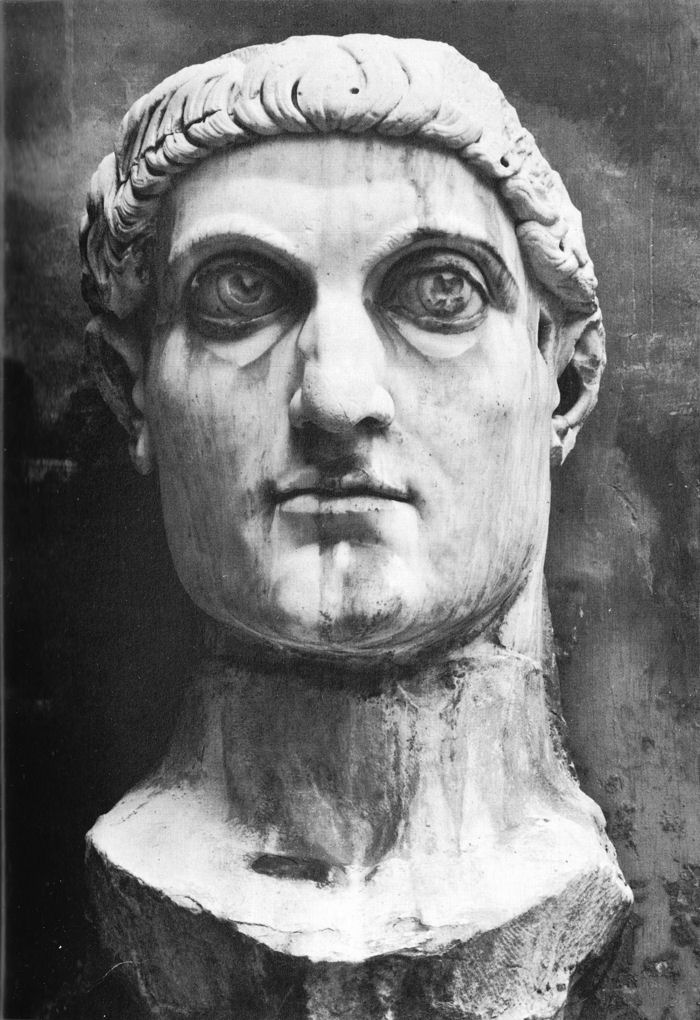

3 Marble head of Constantine, the first Christian emperor and founder of Constantinople

17

![]()

Their measures were not promulgated and put into effect throughout the empire at a given moment, but rather took shape in a piecemeal fashion during the five and a half decades which separated the accession of Diocletian and the death of Constantine.

It had become obvious to Diocletian that his great empire, so beset by internal problems and foreign attacks, could no longer be effectively wielded by a single ruler with the administrative means employed until then. He therefore created the institution of the tetrarchy in the hope that two augusti and two caesars would succeed where one augustus had failed. In 286 he appointed Maximian augustus in the west, and in 293, when he elevated Constantius and Galerius as caesars in the west and east, the tetrarchic reform was completed. This institutional advice was successful during the reign of Diocletian and provided the empire with more efficient government and defence against foreign attacks.

But the establishment of the tetrarchy had a bearing on another problem, the elevation and stabilization of the imperial office within the realm. Diocletian had supposed that the system of two superior rulers, seconded by their caesars and heirs, would largely put an end to usurpation by the ambitious. More significant in the attempt to create respect for imperial authority was the orientalization of the monarchy. This orientalization had been going on throughout the third century, and could be seen in the puerile efforts of Elegabalus or in the coinage of emperors such as Geta and Aurelian. Moreover, certain elements of absolute monarchy had long been present in Greek political tradition. In later times Justinian traced the origins of imperial sovereignty to the action of the Roman senate in 24 BC freeing the augustus from the compulsion of the laws and thus transferring sovereignty from the people to the ruler. But if even in this earlier period there was a divine element behind the auctoritas of the augustus, it was in the third century that the princeps was transformed into an Oriental, divine, absolute monarch. Diocletian’s arrangements completed the transformation. ‘ Proskynesis’ or ‘adoratio’ (the eastern ceremony of genuflection addressed to divinity), purple robes, jewelled diadems, belts, and sceptres became permanent parts of the imperial tradition. The emperor, ruler by divine grace, was the sole fount of law.

18

![]()

Seclusion of the monarch, an Oriental practice by which the person of the ruler was removed from contact with the profane, was carefully balanced by the splendid official ceremonials, at which his power and glory were displayed to the citizens and courtiers. Constantine’s conversion to Christianity, it is true, necessitated an adaptation of the imperial cult to the demands of a stringent monotheism. But the adaptation which resulted, Byzantine kingship, was to all purposes the same as that which emerged under Diocletian. The emperor (as the friend of Christ) and his empire (as a reflection of the heavenly kingdom) were divinely inspired and protected. The Oriental ceremonies attendant upon court ritual remained one of the most characteristic of all Byzantine practices.

Administratively and militarily the measures of Diocletian and Constantine were calculated to facilitate internal control and defence from foreign attacks. But the chief threat to imperial power was internal rather than external, and this problem was given preference. The greatly expanded bureaucratic apparatus was centralized in the imperial consistory, made up of the highest financial and administrative officials of the court, who addressed the emperor not only on routine administrative matters, but on high policy as well. In the provinces the reforms of Diocletian and Constantine weakened potential rebels by removing heavy concentrations of power from the hands of officials. As the power of any given official was directly related to the size and wealth of the area which he governed, the provinces were doubled in number and their size reduced. More radical were the complementary measures by which civil and military authority were thenceforth separated in such a manner that ambitious provincial officials who might contemplate rebellion were effectively hamstrung.

Nevertheless, the problem of defence against Persians and Germans meant that military considerations were not far behind considerations of imperial centralization. The old traditional military frontiers and policies of the Roman past were maintained. The emperor repaired the old border fortresses and town walls, new forts were built, and the limitanei (or frontier militia) retained their defence stance on the Rhine, Danube, and Euphrates. But as this older arrangement was no

19

![]()

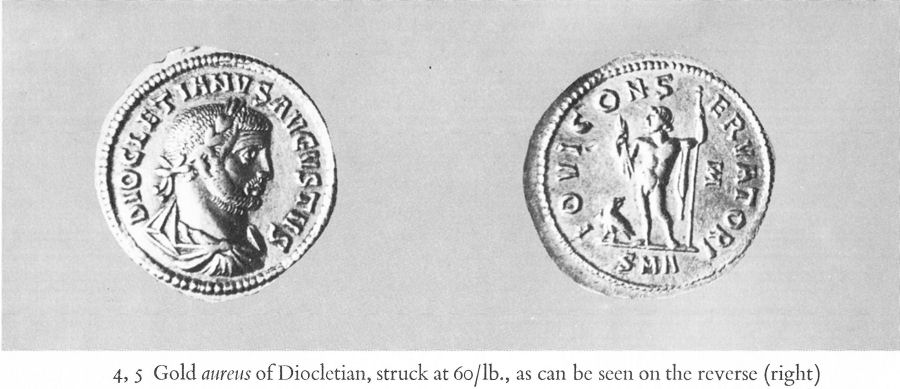

4, 5 Gold aureus of Diocletian, struck at 69/lb., as can be seen on the reverse (right)

longer sufficient to contain the attacks of Germans and Persians the military principle of defence in depth was adopted. The emperors created mobile field armies stationed in the heartland of the provinces rather than on the borders. Such armies in Anatolia or the central Balkans could protect provincial life from pillaging barbarians who had broken through the frontiers or be used to reinforce the borders. In the capital, new forces were added to the crack imperial troops who accompanied the emperor. Even within the armies, however, the principle of separation of powers, which sought to protect the emperor from insubordination, was operative, and superior command of cavalry and infantry was divided.

The reforms of the late third and early fourth centuries greatly increased state expenditure on account of the considerable increase in military and bureaucratic personnel. This situation caused Lactantius to complain that the number of beneficiaries had begun to grow greater than the number of taxpayers, and the increased financial outlay at the end of the century proved to be more than the already strained economy could bear. Debasement of the coinage

and inflation in the preceding period had created havoc with government salaries (which were largely fixed) and with prices. The famous edict of prices (ad 301) bears witness to the government’s concern and also to its failure to fix the cost of living. If the state were to survive, it was imperative that its economic life be brought into harmony with harsh reality, and this is precisely what Diocletian accomplished.

20

![]()

6, 7 The reformed coinage. Gold solidus of Constantine, struck at 72/lb., as indicated on the reverse

Realizing the inadequacy of the taxes which the government collected in cash, Diocletian developed the old levies in kind, the annonae, which had provided the armies with their physical necessities. The annona, formerly an extraordinary tax, was henceforth applied to the rural population on an annual basis.

The new system of taxation freed the government from the vicissitudes of monetary debasement and price fluctuations, for it now paid its officials and troops largely in foodstuffs and clothing. It also forced the government to keep the peasants on the soil to cultivate it and necessitated systematic assessments of the arable land, types of agricultural production, and population. The tax apparatus which arose was to have a long life in the Byzantine empire and was also to affect the tax structure of the Islamic world. The new system enabled the government to formulate an annual budget based on the agricultural produce of the empire. Yet it would seem that Diocletian and Constantine did not intend to abandon completely a money economy. Both instituted coinage reform with the issues of good silver and gold coins. Constantine took the gold coin of Diocletian (struck at 60/lb.) and struck the solidus (72/lb.) which was to become the money of international exchange par excellence until the eighth century when it would share that distinction with the gold dinar of the Arabs. Every five years the traders and craftsmen of the towns, who were free from the annona, paid a cash tax known as the chrysargyron.

21

![]()

It was in the field of religion that the policies of the two emperors contrasted most sharply, for Diocletian remained pagan and Constantine embraced Christianity. The triumph of Christianity is to be understood primarily in terms of two historical facts. First, Christianity was one of those Oriental mystery cults which, as a result of their message and organization, and because of the peculiar conditions of the third-century Roman world, had played an important part in transforming the emotional climate of the Mediterranean lands. The victory specifically of Christianity, rather than of some other Oriental religion, was in large part due to the favour with which Constantine and his successors regarded it. Christianity had existed for some three hundred years prior to Constantine, and yet at the time of Constantine’s conversion, it was the religion of a very small minority in the Mediterranean world. Its victory was the result of state support, just as in Sassanid Persia, where the ruler supported Zoroastrianism, Christianity remained a minority religion, and in Egypt and Syria, where Christianity had spread and bloomed, the Arab conquest eventually entailed the decline of Christianity and the spread of Islam. In the same way, the Turkish conquest of Anatolia and the Latin preponderance in southern Italy and Sicily meant the replacement of Greek Christianity by Islam and Catholic Christianity respectively; while perhaps the most interesting example of the principle cuius regio eius religio was the Iberian peninsula where Christianity and Islam alternated in consonance with the pulse of Arab and Christian military successes.

From the end of the first century, until Constantine made Christianity the favoured religion, the reward which the state meted out to those who professed Christianity was death. In actual practice, however, though the legal status of Christianity did not change, the Christians were tolerated, and by the end of the second and the early third century they had not only successfully proselytized among the upper classes but had also become an accepted part of the empire’s society.

The ‘peace’ between the Roman state and the Christian Church was, however, violently disturbed by the events of the third century which brought to the throne men of a new breed. These were the

22

![]()

soldier-emperors from Illyricum who felt that in order to save the state the old religious practices and ways must be followed.

This revival of Roman paganism reactivated the waning hostility between the state and the Christians. When Decius persecuted the Christians in the years 249-51, it was not so much because he despised Christianity as a religion, but because the Christians refused to sacrifice to the gods, and he felt that the safety of the state could only be assured by prayers to the gods. Thus the Decian persecution was politically, rather than religiously, motivated. The Illyrian emperor Valens renewed discriminatory measures in an effort to destroy the corporate life of the Church. When he fell a victim to the Persians, the Christians could rejoice at their good fortune and Gallienus promptly returned the confiscated Church property. Thereafter state persecution of the Christians ceased until the reign of Diocletian and many Christians entered state service.

Diocletian himself observed the ‘peace’ with the Christians for the greater part of his reign. Probably he would have been satisfied with the status quo had it not been for his caesar Galerius. But the latter, supported by a circle of neo-Platonists, was a determined opponent of the Church and did everything in his power to persuade his augustus to move against the Christians. A series of incidents, rightly or wrongly blamed on the Christians, and the consent of the oracle of the Milesian Apollo, brought Diocletian round to the sentiments of his caesar. The emperor and Galerius issued four edicts between 302 and 305 which revived the state’s persecution of the Church. Christian churches, scriptures, and liturgical books were to be destroyed; Christians were henceforth forbidden to assemble and were placed outside the law; and all men, women, and children who refused to sacrifice were to be put to death. Many abandoned their profession of Christianity because of the fearful persecutions, but such a great number remained steadfast that they filled the prisons and jails, with the result that there was no room for criminals. In 303, when Diocletian celebrated his vicennial in Rome, he ordered that all the jailed Christians be forced to sacrifice so that the prisons might be emptied. Actually Galerius abandoned the persecution in 311, as a result of a fatal illness which he believed to be the vengeance

23

![]()

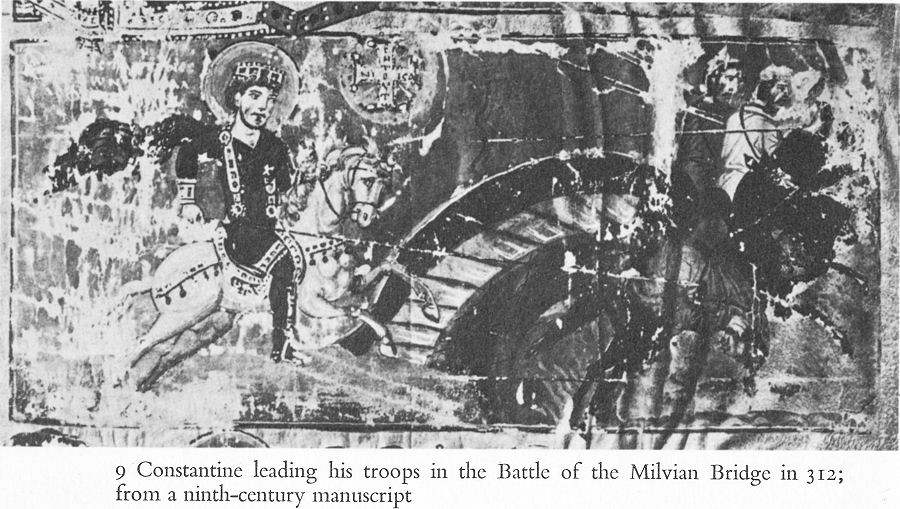

of the Christian God, and surprisingly issued an edict of tolerance. But the status of Christianity became definitive only when Constantine removed his political rivals, Maxentius in 312, and Licinius in 324. Anxious over the issue of the conflict with Maxentius, Constantine was satisfied that the Christian God had indicated His support in the approaching struggle. The appearance of the cross in the heavens with the legend ‘In this shalt thou conquer’, and the vision in which Christ instructed Constantine to manufacture the labarum, instilled Constantine with a confidence in Christ’s support which later seemed to him justified by the results. The emperor did not immediately accept the exclusive nature of Christianity; but the clergy were so pleased with the new turn of events that they did not object to the pagan practices which Constantine continued.

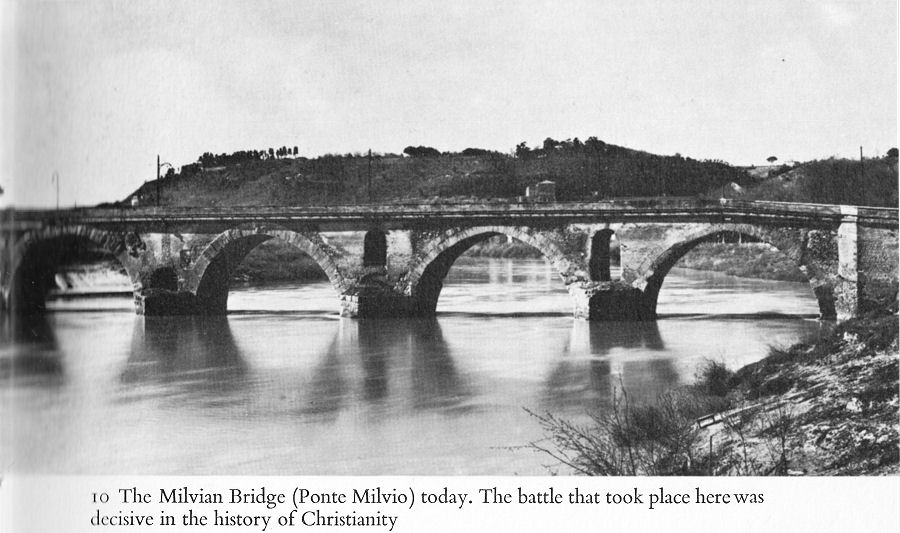

It was, of course, his defeat of Maxentius in the battle of the Milvian Bridge which marked the beginning of the ultimate triumph of Christianity, for even though it did not become the exclusive religion of the state, it now enjoyed imperial preference. Constantine became a lavish patron of the Church, supporting it with generous gifts and privileges, and simultaneously confiscating the treasures of the pagan temples.

The Church had miraculously acquired a generous patron, but it had simultaneously taken on a powerful master. The tradition of the Roman emperor as pontifex maximus survived, in a modified form, in Byzantine caesaropapism. Convinced that the unity and survival of his empire depended upon the unity of the Church, Constantine used the imperial power and prestige in an effort to heal the disputes which were now arising among the bishops. In an attempt to heal the Donatist conflict he received petitions from the bishops, called a council, exiled bishops, and made use of persecution. His behaviour in the Arian controversy illustrates how fully developed his caesaropapism was. It was he who initiated the call for an ecumenical council, brought the bishops to Nicaea and maintained them at state expense, presided over and directed the deliberations and enforced upon the bishops the theological solutions which he preferred. As in so many other institutional transformations, Constantine 24 left his indelible mark on the relations of Church and state in the east.

24

![]()

8 Constantine presenting a model of the city to the Virgin; detail of a late tenth-century mosaic in Hagia Sophia

25

![]()

9 Constantine leading his troops in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312; from a ninth-century manuscript

The emperor would remain the master of the Church. Though powerful patriarchs, weak emperors, and exceptional circumstances might temporarily redress the balance in favour of the Church, the survival of a centralized state enabled the emperor to control the Church.

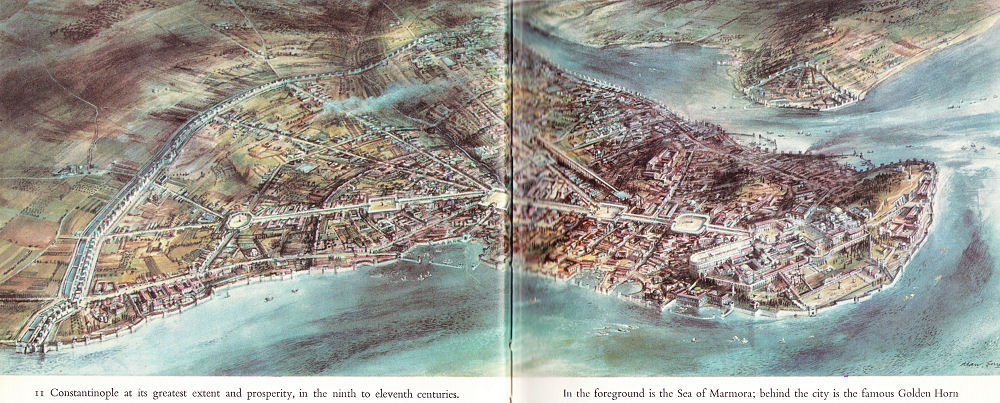

The most apparent manifestation of a change in the established order was the desertion of Rome as the imperial capital. Though Milan replaced it as the imperial centre in the west, the principal imperial residence came to be located in the east, Diocletian establishing himself in Nicomedia, and Constantine in Constantinople. The choice of these two Greek cities indicates that the empire’s political centre of gravity had shifted to the east. It was not until the reign of Charlemagne that a political centre of comparable magnitude would crystallize in the west. When Constantine traced the limits of his new city, he was laying the foundations for a metropolis which would become the largest urban concentration in medieval Europe, and which would leave its imprint upon history as few cities have. He decided that the New Rome should be inferior in no way to the Old Rome. He created a senate, provided the citizens with free

26

![]()

10 The Milvian Bridge (Ponte Milvio) today. The battle that took place here was decisive in the history of Christianity

bread and games, and built churches and public buildings on a lavish scale. He plundered the cities and temples of their marbles and statues in order to ornament his new capital.

Historical and geographical forces had made of Rome an ineffective capital. In contrast, Constantinople was strategically located midway between the critical Danubian and eastern frontiers and between the principal military reservoirs of the Balkans and Anatolia. The eastern provinces were more populous than those of the west, and urban and industrial development there was more vital. Commercially the new city enjoyed the best natural harbour of the medieval world. The Golden Horn, protected from the currents and winds, was a deep body of water which could accommodate large numbers of vessels. Located at the junction of water and land routes which connected east and west, south and north, the city was to be the greatest commercial emporium of Europe for many centuries. Chinese silks, eastern spices, Egyptian wheat, slaves from the west, and furs from the north indicate the international character of the market at Constantinople. The waters immediately adjacent to the city were (and still are) a rich fishing ground which yielded

27

![]()

11 Constantinople at its greatest extent and prosperity, in the ninth to eleventh centuries. In the foreground is the Sea of Marmora; behind the city is the famous Golden Horn

an ever-ready source of sustenance to the inhabitants and citizens. This location not only provided Constantinople with immense economic vitality, but also made it impregnable. Guarded as it was on three sides by water, and girt by an effective system of land and sea walls, the capital was secure against either land or naval attack. Throughout its long history, the empire was able to survive the virtual loss or at least the occupation of critical provinces by powerful enemies. The inability of the enemies to take this central bastion (with the exceptions of 1204 and 1453) enabled the Byzantines to bide their time until the opportune moment for a successful counterattack. One final condition which, along with the others, may have persuaded Constantine to found Constantinople was his desire to

28

![]()

break with the pagan past and to centre the empire in a new Christian foundation.

Constantine’s dedication of the new imperial capital in 330 marked the end of half a century of momentous reforms. Those reforms, with their roots in the disorders of the third century, institutionalized the transitional trends in disintegrating Roman society. What emerged has been variously characterized as an absolute monarchy, an Oriental empire, a corporate state. It is undeniable that elements of each were present, for the divinely-ordered basileus (emperor) presided over a highly centralized administration which effectively regulated the economic and social life of each subject.

29

![]()

3. THE BARBARIAN, THREAT

The reformed and revitalized empire was to be put to an arduous and violent test by the crisis of the late fourth and fifth centuries. This was precipitated by the fear which the Huns spread among the Goths. These newcomers on the European scene were to be the first of a long line of nomadic conquerors that would terrorize the settled society of the Christian and Muslim worlds. Beginning with the Huns and lasting for a millennium, the continuous strife of the Altaic peoples in the wasteland of central Asia resulted periodically in the westward march of Bulgars, Avars, Patzinaks, Uzes, Cumans, Seljuks, and Mongols. These tribes of the Altai, who had been formed by the geographical, climatic, and political turbulence of central Asia, confronted not only the Byzantines but even the warlike Goths with a military system which was efficient, ruthless, and terrifying.

The Huns, forced to leave central Asia, first appeared in southern Russia where they dispersed the Alans and destroyed the state of the Ostrogoths. Finally they forced the Visigoths to seek refuge in the Byzantine empire after having defeated them at the Dniester River. In 376 the Visigoths petitioned Valens for asylum south of the Danube and the emperor, not realizing the problems which the presence of a whole nation under arms would cause, gave his consent. But when the Visigoths began to enter Byzantine territory, the imperial authorities were simply not equipped to handle the provisioning and policing of the barbarian hosts, and to make matters worse Lupicinus, the comes (Count) of Thrace, began to exploit the panic-stricken Goths and enslave their families in return for bread. The angered barbarians ravaged the Balkans and soon Valens faced them with his forces outside Adrianople in 378. The ensuing conflict, in which Valens and perhaps two-thirds of the imperial forces perished, was a shattering defeat for the empire, but the barbarians were unable to exploit their victory, and when they appeared before Adrianople, Perinthus, and Constantinople, the strongly walled Greek cities held them at bay.

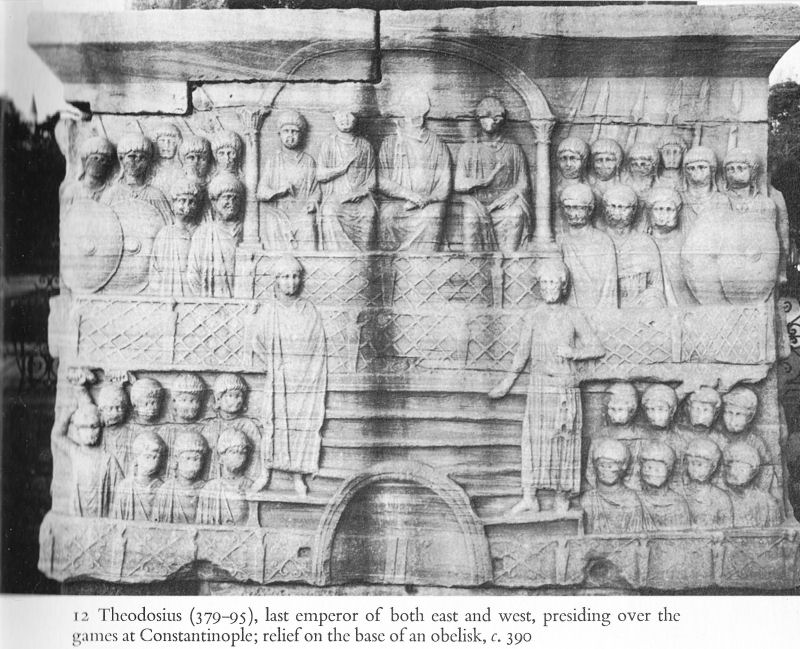

The accession of the Spaniard Theodosius I brought an energetic soldier-emperor to the throne who, though not successful in destroying the Visigothic menace,

30

![]()

12 Theodosius (379-95), last emperor of both east and west, presiding over the games at Constantinople; relief on the base of an obelisk, c. 390

provided the tottering empire with a badly needed breathing period. Secure in his possession of the walled cities, Theodosius had to restrict the Visigothic raids which were desolating the rural areas. In 382 he formally permitted them to settle in Lower Moesia as federate troops (foederati), and as they abandoned Dacia, the Huns occupied it unopposed. Theodosius, evidently an admirer of their martial qualities, took many of the Visigoths into the armies of the empire. But this was a dangerous step, the consequences of which were seen in the history of the next few years. The Visigothic king, Alaric, was able to attain the high office of magister militum by simply blackmailing the government with his raids in Thessaly and the Peloponnese. The quarrel between Arcadius, emperor of the east, and Stilicho (the Vandal general who

31

![]()

really ruled the empire in the west) over possession of Illyricum greatly improved the prospects of Alaric. For though Stilicho defeated Alaric twice in Greece and twice in northern Italy, because of the quarrel with Arcadius over Illyricum, he refrained from destroying the Visigoths. After the death of Stilicho, Alaric succeeded in ravaging Italy and in sacking Rome (410). This barbarian chief, who had paraded his hordes across the empire under the full light of history, hoped to cross to Africa and settle his followers there. But he died prematurely and one of his successors, Wallia, eventually led the Visigoths northward and settled them in southern Gaul, where the emperor commissioned him to drive from Spain the barbarians who had recently settled there.

These barbarians, the Suevi, Alans, and Vandals, had taken advantage of Stilicho’s preoccupation with Alaric in northern Italy and with the province of Illyricum to march through Gaul, ravaging and plundering, and make their way to Spain. Here the Vandal leader Gaiseric received an invitation from the rebellious Byzantine governor of Africa to support him, with the promise, in exchange, of half of the Byzantine provinces in North Africa. In 429 imperial vessels ferried the Vandals and Alans to the African coast, and by 439 Gaiseric had taken Carthage. His audacity grew rapidly with each success, culminating in the sack of Rome (455) and a raid on the distant Peloponnese (465).

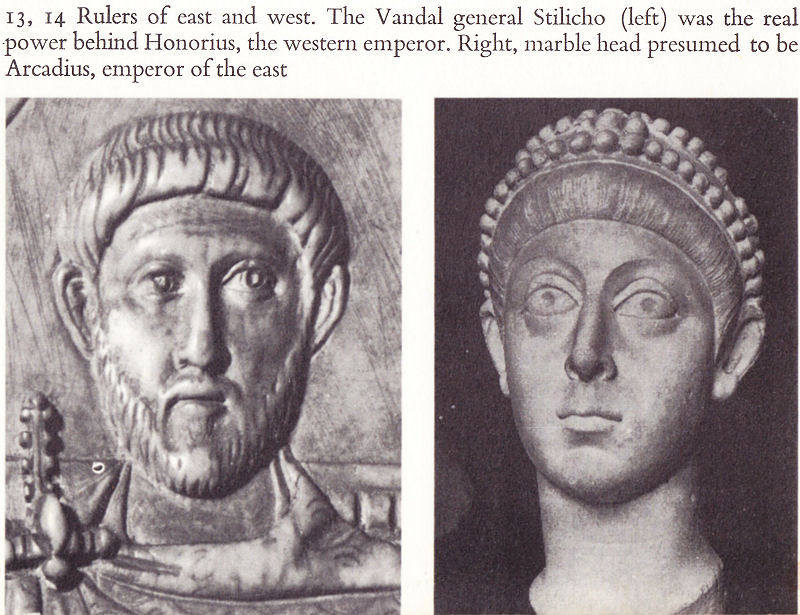

13, 14 Rulers of east and west. The Vandal general Stilicho (left) was the real power behind Honorius, the western emperor. Right, marble head presumed to be Arcadius, emperor of the east

32

![]()

15 This mosaic in the Church of S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna shows ships at Classis, the port of that city

33

![]()

The Italian peninsula, largely isolated by the establishment of the Visigoths in the northwest and the Vandals in the south, became an easy prey to another Germanic people, the Ostrogoths. This people had been settled by the imperial government as foederati in northern Pannonia on the borders of Italy after the breakup of Attila’s empire in 452. When in 476 the German Odovacer deposed the last emperor of the west, the Byzantine ruler Zeno commissioned the Ostrogothic leader Theodoric to invade Italy and to supersede the ruler there '... until he should come’. In fact Zeno did not come and by 493 Theodoric had formed the Ostrogothic kingdom. With the establishment of the Burgundians and Franks in Gaul and the Saxons in England, the dismemberment of the empire in the west was complete and a new host of Germanic kingdoms had arisen on the carcass of the empire.

It is significant that the Germanic threat had first appeared, in its most violent form, in the east. Both Visigoths and Ostrogoths had threatened the east; but in spite of their repeated successes, they were forced to move westwards, and although the west resisted, and might perhaps even have prevailed under Stilicho, after his death it collapsed. The reasons for the success of the east are to be sought in its greater material and spiritual resources. The Balkans bore the initial brunt of the furor Teutonicus, but the Germans were not able to destroy the wealth and manpower of Anatolia, Armenia, the Caucasus, Syria, and Egypt. The strength which the more developed urban society of the east gave the empire is impressive. This society also successfully resisted the internal penetration of the barbarians which threatened to Germanize the armies and bring the bureaucracy under its control. When the Goths’ general Gainas attempted to take over the government in Constantinople, he aroused a nationalism which matched in ferocity that of the nineteenth century. Synesius, a Greek intellectual from the province of Cyrenaica, admonished the emperor that to have Germans in the army was the equivalent of bringing wolves into the sheepfold. Elaborating on the old Hellenic theory that Greeks and barbarians were different in kind and their union unnatural, he suggested that if they could not be sent beyond the Danube whence they had come, they should be put to labour in the fields.

34

![]()

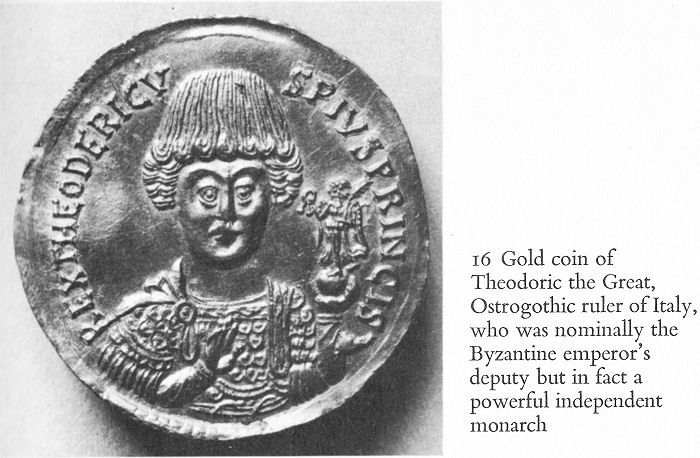

16 Gold coin of Theodoric the Great, Ostrogothic ruler of Italy, who was nominally the Byzantine emperor’s deputy but in fact a powerful independent monarch

The Goths of Anatolia, who had sided with Gainas, were defeated by the local inhabitants, and when Gainas and his Goths finally abandoned Constantinople, the citizens slew several thousands of the barbarians as they were departing.

The east had survived because it had the men, the resources, and the will to survive. The west, unequal to the east in manpower and wealth, was further debilitated by the breakdown of the administration and the military machine.

4. CRISIS OF THE FOURTH AND FIFTH CENTURIES

Free of Germans, the east was, however, faced with religious problems which nearly succeeded in destroying it where the Germans had failed, and which were absent in this high degree in the west. Christianity had experienced a remarkable expansion following the conversion of Constantine, for in the century that followed his death, all rulers, save Julian, were dedicated Christians, Furthermore, the evolution of ecclesiastical institutions prior to 312 had endowed Christianity with a well-developed administrative mechanism, the efficiency of which played an important rôle in its resistance to persecution and then its spread. This apparatus, with the episcopacy at the top and descending through the various lower clerical orders, constituted a hierarchic pyramid which the neophyte had to ascend from the bottom in order to attain any high office. Though many of

35

![]()

the bishops conceived of their function in the light of the Old Testament, the influence of the imperial administration upon the structure of the Church is obvious.

If, however, the spread of Christianity implied its worldly involvement, reaction to this situation, combined with the asceticism in the New Testament, gave rise to monasticism. The heremitic monasticism of St Anthony and the cenobitic foundations of St Pachomius in Egypt represent the crystallization of these ascetic tendencies within the Church. Though both types of monasticism remained popular in the Byzantine empire, it was fortunate that St Basil adopted the Pachomian version, and this ensured that the energies and power of the monastic movement would contribute to society at large.

A further result of the growth of the Church was the rivalry of certain episcopal sees within the Church structure. One of the great problems of any federation is the difficulty of reconciling the theoretical equality of all members with the realistic fact that obviously some members are more important than others. In the fifth century this rivalry became quite bitter as the bishops of Alexandria and Rome resented the rapid rise in prominence of the bishops of Constantinople, and the Antiochene bishops attempted unsuccessfully to put an end to the pretensions of the episcopate of Jerusalem. Behind the ensuing struggle between the Churches of Constantinople and Rome was the principle that the rank and importance of a bishopric in the ecclesiastical administration depended upon the size and importance of the city in the civil administration.

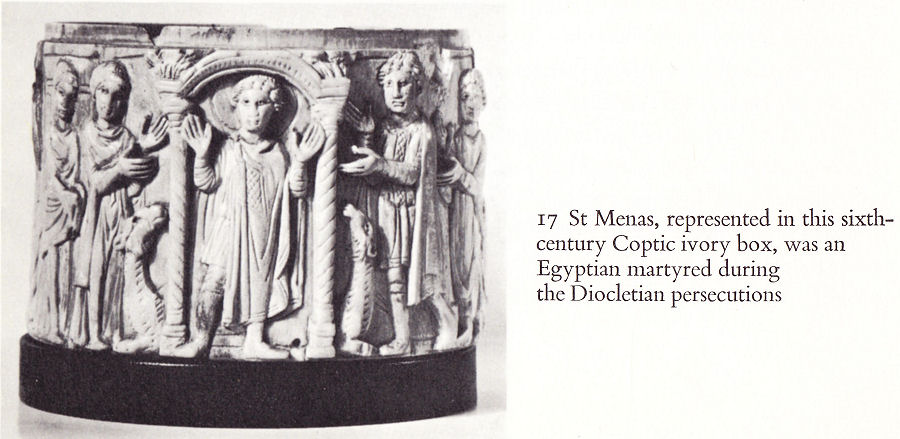

17 St Menas, represented in this sixth-century Coptic ivory box, was an Egyptian martyred during the Diocletian persecutions

36

![]()

18, 19 Profane and sacred aspects of Coptic art. Wool embroidery of a dancer (left); wall painting of the Virgin and Child (right)

Just as the bishops of Old Rome had enjoyed a position of ecclesiastical pre-eminence because Rome had been the capital of the empire, so now the bishop of Constantinople claimed to enjoy a similar position because he was bishop of the New Rome. It was in response to these claims of Constantinople that Pope Damasus expounded the doctrine of Petrine supremacy in the late fourth century.

The great intellectual achievement of the Church in the fourth and fifth centuries was the definition of Christianity through the formulation of a theology. Modern man for the most part considers theology as little more than the irrelevant speculation of the priestly caste, neutralized and bypassed by the advance of scientific thought.

37

![]()

But Byzantine society was theologically oriented. Theology seems to have been the favourite topic of conversation even with the ordinary citizens of Constantinople. Gregory of Nyssa remarked that when he went to the capital, the citizens were talking unintelligible theology.

‘If you ask someone how many obols a certain thing costs, he replies by dogmatizing on the born and unborn. If you ask the price of bread, they answer you, the Father is greater than the Son, and the Son is subordinate to Him. If you ask is my bath ready, they answer you, the Son has been made out of nothing.’

The Greek passion for logic and speculation is abundantly evident in the theological controversies of the period and it might even be said that theology represented a Christian sublimation of these Greek traits. The acts of the first four ecumenical councils are the conclusions which Greek theologians, utilizing Greek logic, extrapolated from Christian teaching. The effort to define Christianity in these councils, however, was as important politically as it was religiously, for it eventually resulted in the disaffection of Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. Thus when Constantine had stated that God demanded the unity and the well-being of the Church as the price for the empire’s prosperity, he had been, in a sense, prophetic. For in the Byzantine empire the existence of one emperor, one administration, and one church constituted the bonds which held the multi-national populations together. The Trinitarian controversy, which the Alexandrian priest Arius provoked when he stated that Christ was less than God, consumed theologians and emperors for over half a century. The Council of Nicaea condemned the doctrines of Arius in 325, but since Constantius supported him the government did not renounce the heresy until 381 when Theodosius I called the ecumenical council of Constantinople. Here the theologians formulated the basic creed recited in the majority of Christian churches today. In asserting the full divinity of the Trinity, the bishops condemned a certain Apollonarius of Laodicia, who had declared that Christ was not fully man.

Arianism gradually subsided in the east, but was soon followed by the Christological controversy, and this new debate, arising from the different teachings of the two theological schools of Antioch and

38

![]()

Alexandria, became further complicated by the ecclesiastical ambitions of the various participants. Cyril, the patriarch of Alexandria, launched a bitter attack upon Nestorius, the patriarch of Constantinople, which culminated in the council of Ephesus (431), over which Cyril, supported by his unruly Egyptians, presided. Not surprisingly, he condemned Nestorius, and in so doing, formulated the view that in Christ there occurred the union of two natures, the human and the divine. Though Nestorius himself evidently did not subscribe to the views with which Cyril charged him, the heresy to which he lent his name emphasized the human nature of Christ at the expense of the divine. The other extreme of the Christian position, emphasizing the divine at the expense of the human, was the salient characteristic of the other Christological heresy, Monophysitism. Cyril’s Egyptian followers distorted his doctrine of the union of the two natures and declared that though there were two natures before this union in Christ, afterwards there was only one nature, the divine. It was the fourth ecumenical council at Chalcedon which condemned the Monophysite doctrine and insisted upon the completeness of Christ in both his humanity and divinity. The council censured Euytches, the propounder of the Monophysite doctrine, and his supporter, the Alexandrian bishop Dioscurus.

The council of Chalcedon is a major landmark in the ecclesiastical and political history of the world. It completed the definition of Christianity which the councils of the preceding century had commenced, and it elevated the See of Constantinople to a position which overshadowed the Church of Alexandria and which claimed equality with Rome. The decisions of Chalcedon also had political consequences far beyond anything that the participants could have imagined. Monophysitism originated as the position assumed by certain theologians and bishops, but as a result of its spread in Egypt and Syria (those regions which had resisted complete Hellenization), it eventually became associated with non-Greek populations. The toleration which Zeno and Anastasius I accorded Monophysitism enabled it to take such firm root that the emperors of the sixth and seventh centuries vacillated between persecution and compromise in an unsuccessful effort to bring the Monophysites of these provinces back into the folds of the state Church.

39

![]()

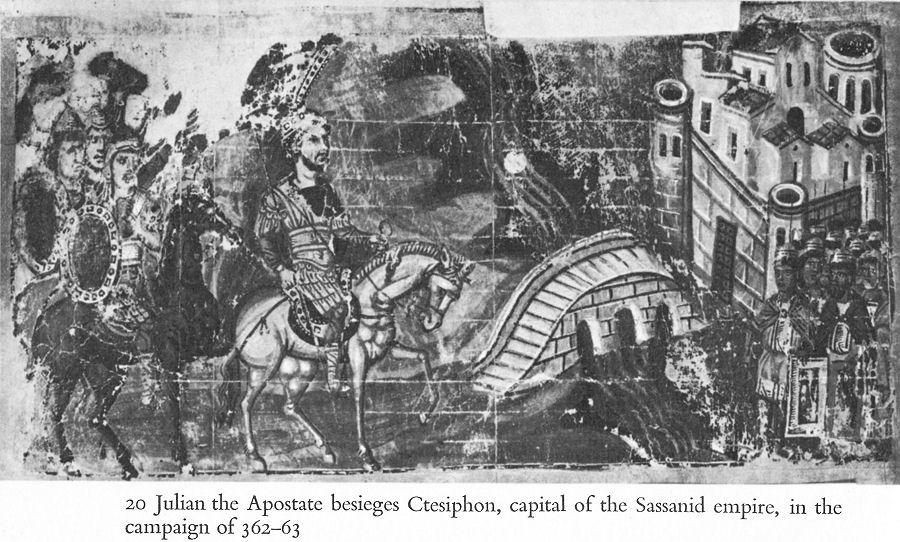

20 Julian the Apostate besieges Ctesiphon, capital of the Sassanid empire, in the campaign of 362-63

The long-term political effect of the Christological controversy was the promotion of disaffection and the development of cultural separatism within the empire.

In spite of the formal triumph of Christianity and state sponsorship the Byzantine Church retained a strong missionary spirit. The repeated anti-pagan decrees of Constantine and Theodosius I indicate that paganism was dying a slow death, and the revived opposition of Julian and the Roman senate to Christianity prolonged its existence. In the more isolated areas paganism persisted for many centuries, as was the case in the southern Peloponnese where the Greeks did not receive Christian baptism until the ninth century. Moreover, defeated paganism emerged quite often in the bosom of the Church in the form of heresies. The Church was not able to wean the people away from the pagan practices which had been intimately associated with everyday life, and our own celebrations of 25 December and the New Year, hagiolatry, and other practices are all evidence of the compromises which Christianity had to make. Even today in rural Greece the clergy still oppose the sacrifice of cocks by the peasants on the grounds that it is a pagan practice.

It was, however, in literature and learning that paganism won its most obvious victory.

40

![]()

When Christianity spread through the Graeco-Roman world, it entered a literary and intellectual domain which was superior to that of the Semitic Near East. As Christianity had very little with which to replace Graeco-Roman tradition in this respect, Christian intellectuals were torn between the Christian texts and classical literature. But in order to cope with the Mediterranean world, Christianity had to accommodate itself to the lettered traditions that prevailed there, and the very use of Greek in the New Testament is proof of this necessary accommodation. The Alexandrians, Clement and Origen, created Christian scholarship by adopting Greek critical and philological methods, and the Cappadocian fathers carried the process of acculturation to its logical conclusion. They accepted the value of Greek paideia but declared it to be incomplete. Christianity, they proclaimed, was the fulfilment of the paideia of the ancients, but they believed that the classics should be studied for their literary form rather than for their content. Christianity did bring new forms in certain respects—in ecclesiastical history, for example, and in hagiography, and hymnography - but the churchmen played a critical rôle in preserving the classics, copying and studying them and writing long commentaries on them. This they did until the end of the empire.

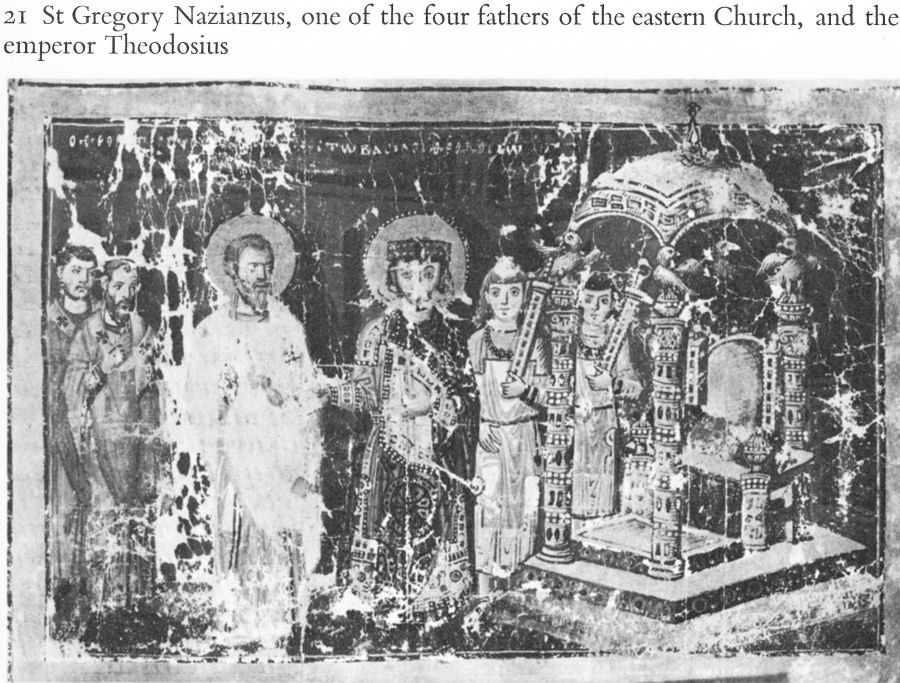

21 St Gregory Nazianzus, one of the four fathers of the eastern Church, and the emperor Theodosius

41

![]()

5. JUSTINIAN THE GREAT

Justinian (527-65), more than any other ruler, was responsible for establishing the finished forms and setting the tone of the Byzantine society which Diocletian and Constantine had established. His personality and genius inspired and permeated all the great achievements that were accomplished during his long rule. In this respect his rôle in the history of the time was perhaps more important than that of Pericles in fifth-century BC Athens or of Louis XIV in France. Of obscure peasant origins, Justinian nevertheless received an excellent education, and is perhaps the most remarkable example of that social mobility by which obscure but capable individuals could rise spectacularly in the Byzantine empire. Possessed of a lofty conception of his office, Justinian determined to reconstitute the empire territorially, to unify the quarrelling factions in the Church, and to simplify the legal accumulations of the past centuries. The union of these elevated ideals with Justinian’s inexhaustible energies (his subjects called him the sleepless emperor) resulted in the reconquest of much of the west, the codification of the law, and a phenomenal artistic accomplishment. His beautiful consort, Theodora, was perhaps of even lower origins (she was the daughter of a bear-tamer at the hippodrome). All agree that she was a powerful personality, and in spite of the rather poor press she received from the prejudiced Procopius, there is no doubt that she had a certain influence over Justinian. In fact the relationship of Theodora and Justinian recalls the association of Pericles and Aspasia. Though Justinian seems to have maintained his own policies in most matters, his determined wife often followed her own desires in such matters as the support of the Monophysite clergy. Perhaps her most decisive act was her intervention in the resolution of the court council that the emperor should flee Constantinople during the Nika rebellion of 532. Had Justinian followed the decision to flee, his reign would have terminated before the consummation of the works for which it is famous.

When the circus factions of the Blues and Greens rioted in January 532 they were carrying on an activity which had long been 42 familiar and dear to the inhabitants of the empire’s cities.

42

![]()

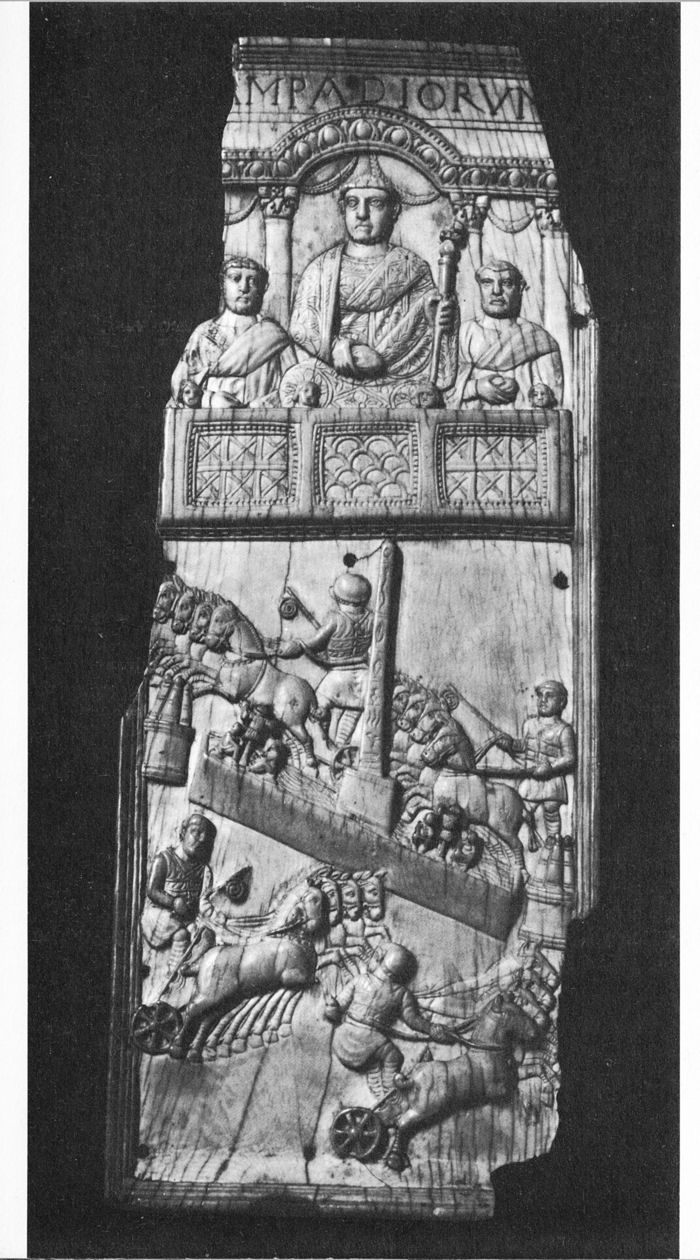

22 An aristocratic family watching the games at the Hippodrome in Constantinople

43

![]()

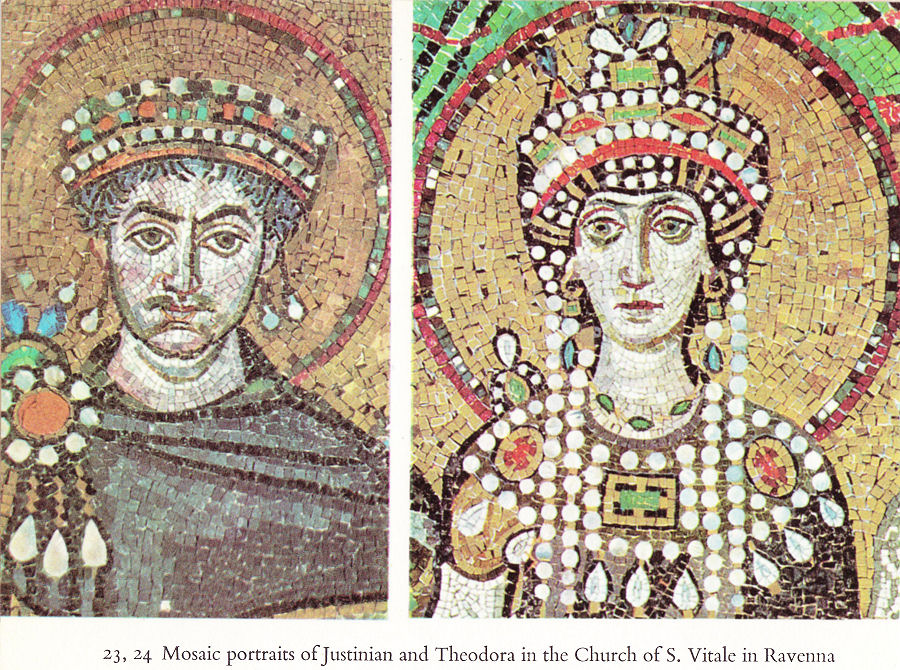

23, 24 Mosaic portraits of Justinian and Theodora in the Church of S. Vitale in Ravenna

From at least the first century sports organizations had existed which were responsible for the games in the hippodromes of the cities. With the passage of time increasing numbers of young men came to be associated with one or another of these circus factions. By the fourth and fifth centuries the competition of the two most important of these, the Blues and Greens, had become so violent that it was accompanied by riots and urban warfare. The factions, however, came to be much more than troublesome sport clubs, for with the barbarian invasions which threatened the cities, the empire armed the demesmen (citizens) and thereby converted the factions into an urban militia. In a sense these urban militia sports organizations became the last refuge of the liberties of the empire’s cities, and when Byzantine authorities spoke of ‘demokratia’, they usually had in mind the rebellions and riots of the Blues and Greens. Though the factions usually fought one another, they joined forces and almost overthrew Justinian in the great Nika rebellion of 532.

44

![]()

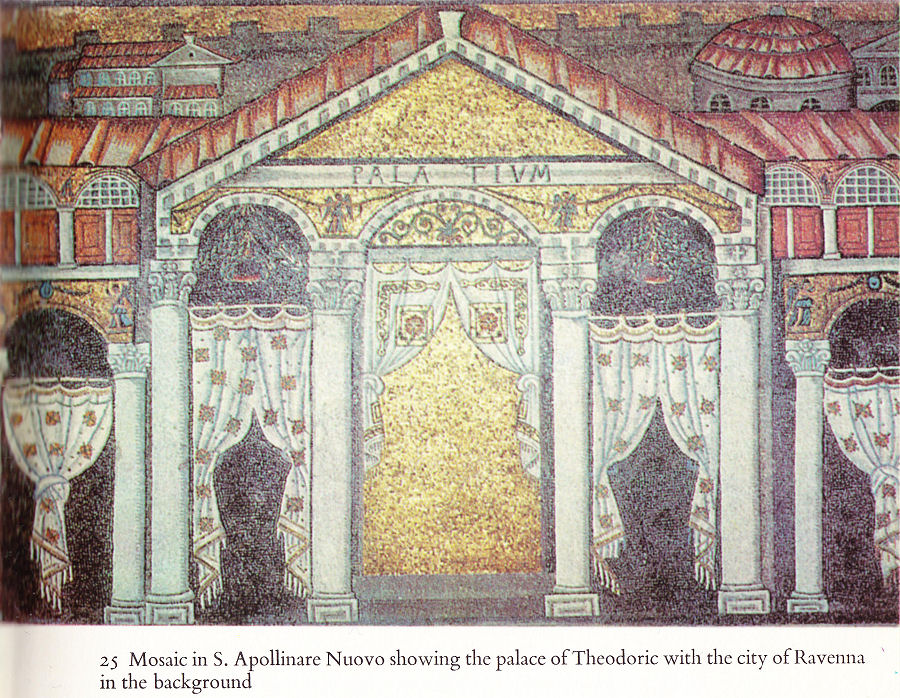

25 Mosaic in S. Apollinare Nuovo showing the palace of Theodoric with the city of Ravenna in the background

It was during these events that Theodora saved Justinian’s throne by urging him to fight to the end. The rebellion, which destroyed a substantial part of the city’s centre, was finally defeated in a blood bath during which, contemporaries report, 30,000 perished.

The Nika riots stand as a turning-point of Justinian’s reign; after their suppression Justinian embarked upon his reconquest of the west, the rebuilding of the capital, and the completion of the codification of the law.

In spite of the fact that the imperial collapse in the west had been complete, there were certain conditions favourable to the Byzantine reconquest. The indigenous population considered the Goths and Vandals as Arian heretics, whereas the emperor of Constantinople represented the religious establishment. Their settlement in Italy and Africa and their association with a more advanced society had

45

![]()

begun to transform many of the barbarian leaders, with the result that the successors of both Theodoric and Gaiseric were somewhat tamer. Finally, the complex system of marriage alliances, which Theodoric had arranged with the Vandal, Thuringian, and Visigothic kingdoms, collapsed and left the Vandals and Ostrogoths diplomatically isolated. After having concluded a peace with the Persians in the east, Justinian sent Belisarius to North Africa in 533. This brilliant general, with only 16,000 men, rapidly put an end to the Vandal kingdom, and by the following year returned to Constantinople where the Vandal king Gelemir and his treasures (which the Vandals had taken from Rome in 455) graced Belisarius’ triumph in the hippodrome.

The political situation in Italy greatly facilitated the Byzantine invasion of the peninsula, for not only had the Ostrogoths and Vandals turned against one another (as a result of this the Ostrogoths had, with incredible lack of foresight, permitted the Byzantine fleet to use Sicily as a base for the African expedition), but Queen Amalasuntha had close relations with Justinian. At the same time Byzantine diplomacy had assured papal support by the denunciation in 518-19 of the Henoticon (482) of the emperor Zeno. The Henoticon, an edict of Monophysitic nature, had alienated the papacy and caused a schism between the churches of Constantinople and Rome, which furnished Theodoric with a considerable diplomatic and political advantage in his relations with Byzantium. When the murder of Amalasuntha at the hands of an anti-Byzantine Gothic faction deprived Justinian of his principal pawn, he sent Belisarius to accomplish by arms what diplomacy had failed to do.

The invasion of Sicily in 535 marked the beginning of the reconquest of Italy which was to last for more than two decades and was to devastate the peninsula. The length and difficulty of the campaign was due to the meagreness of the manpower and financial resources which Justinian placed at Belisarius’ disposal. The inadequacy of Belisarius’ troops (he began the task with only 8,000 soldiers) enabled the Goths to carry on a protracted resistance and often to retake lands and cities from the Byzantines (Rome changed hands five times). Hence it was not until the middle of the century that the

46

![]()

eunuch Narses settled the issue favourably, by which time Byzantine arms had also utilized Visigothic dynastic disputes to regain a foothold in Spain.

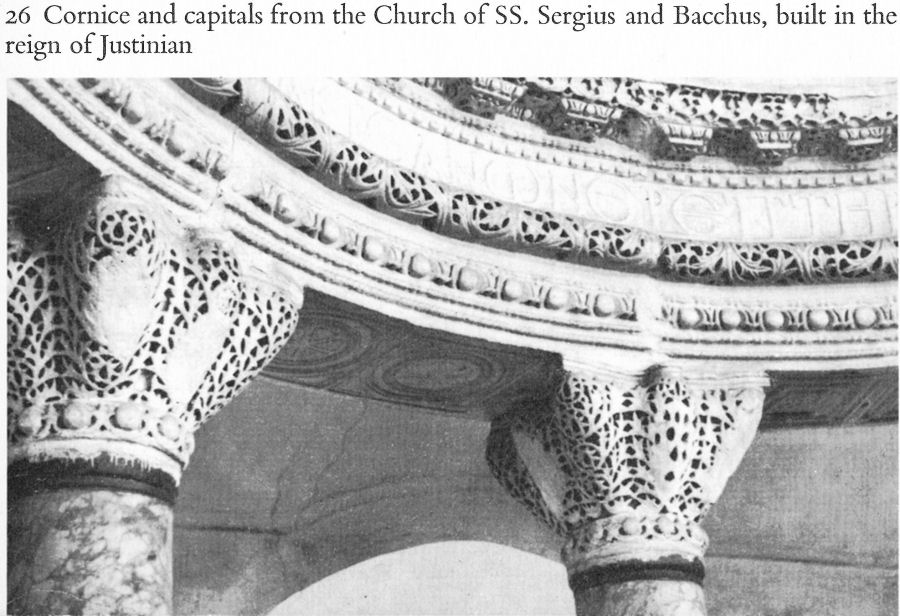

By exploiting the diplomatic isolation of his opponents in the west and by assuming a defensive stance in the east, Justinian had succeeded in converting the Mediterranean once more into an imperial lake, and the destruction of the two barbarian kingdoms had also brought a temporary lustre to the imperial name. Justinian realized his imperial and Christian ideals not only in the political action of reconquest but also extensively in his architectural and artistic embellishment of the empire. Byzantine art was heavily indebted to Helleno-Oriental developments in Anatolia, Syria and Egypt, but the product which emerged was no servile imitation. It remained faithful to the Christianized Greek spirit and contrasted sharply with Coptic and Syrian art. The political, religious and economic centralization of the empire in Constantinople was decisive in the character of Byzantine art, and the appearance of an inspired monarch with a handful of gifted architects and artists not only induced a crystallization but simultaneously produced the apogee of Byzantine art. Constantinople itself sent forth the architects and plans for churches, civic buildings, and fortifications to its provinces. Even in such a detail as the carving of capitals of columns the domination of Constantinople is reflected, for most such capitals were of a uniform Constantinople type and were hewn from the Proconessian quarries near the capital.

26 Cornice and capitals from the Church of SS. Sergius and Bacchus, built in the reign of Justinian

47

![]()

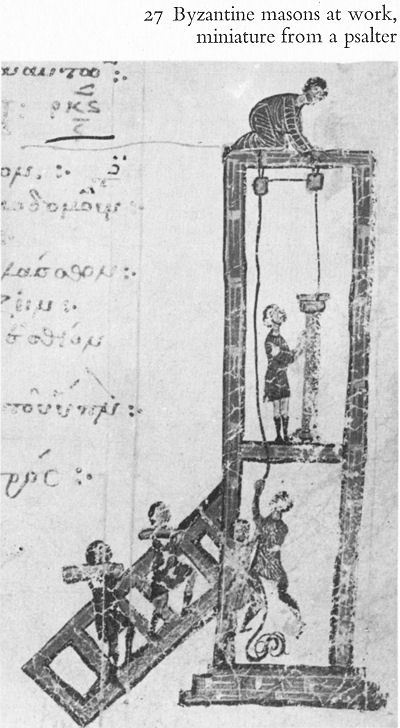

27 Byzantine masons at work, miniature from a psalter

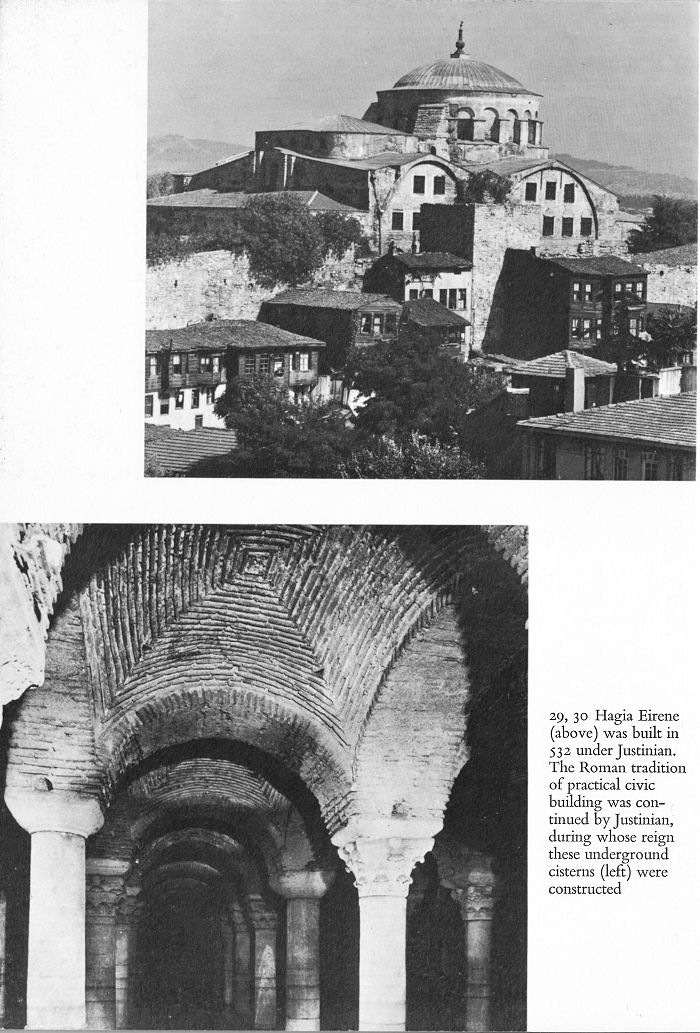

The Nika riots, by virtue of the extensive destruction which they caused to the capital, enabled Justinian to give full play to his passion for building and to provide the city with architectural monuments worthy of its status as the greatest city west of China.

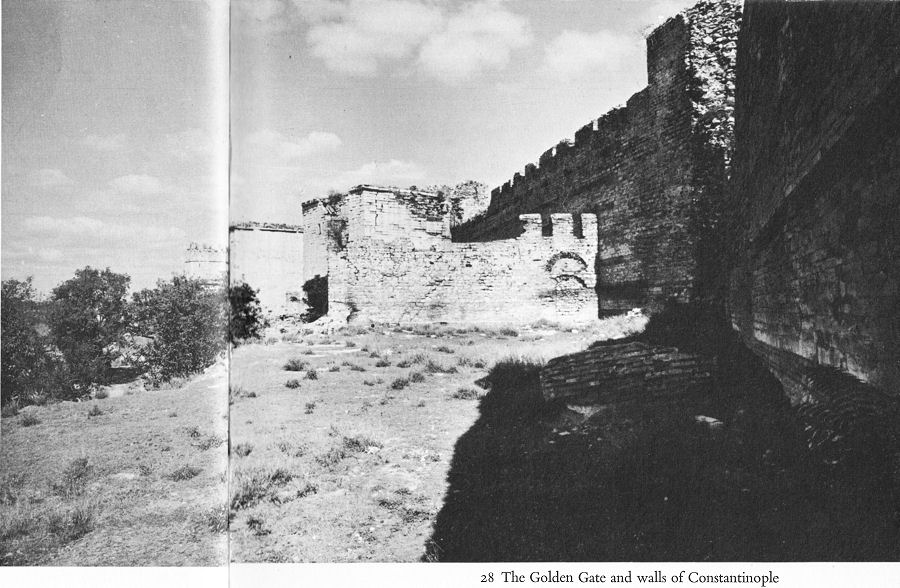

Constantinople had grown so rapidly after 330 that in the fifth century new land walls had to be built in order to protect the greatly expanded metropolis. As the disturbances of 532 had gutted extensive sections of the district near the palace, including Hagia Sophia and the senate buildings, Justinian determined to rebuild the church on a magnificent scale and for this purpose purchased the remaining 48 houses in order to demolish them.

48

![]()

28 The Golden Gate and walls of Constantinople

The new church which he constructed ranks, along with the Parthenon and St Peter’s in Rome, as one of the three most important buildings in European history, and is the most significant edifice in the religious architecture of eastern Europe and the Near East. Just as in the military realm Justinian was served by competent generals, so too in his building activities he enjoyed the assistance of talented architects, the best known of whom, Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, built this famous church. Justinian assembled marble and stone from the pagan monuments of Athens, Rome, Ephesus and Baalbek, and the quarries of Greece, Egypt, Africa and Asia Minor furnished new marbles. The splendour of the marbles was enhanced by the lavish application of gold, silver, ivory and semi-precious stones.

49

![]()

29, 30 Hagia Eirene (above) was built in 532 under Justinian. The Roman tradition of practical civic building was continued by Justinian, during whose reign these underground cisterns (left) were constructed

50

![]()

31 The Aqueduct of Valens, Constantinople, was built in 368 to carry water to the imperial palaces

Justinian and his architects, at the head of several thousand workers, terminated this Herculean labour in the relatively short period of five years.

At the inauguration ceremony of the completed church (27 December 537), the patriarch received Justinian at the church’s entrance and thereby initiated a new period in Byzantine ceremonial which was to last within the empire itself until 1453. Justinian entered the church and proclaimed aloud,

‘Glory to God who has deemed me worthy of accomplishing such a work! O Solomon! I have vanquished thee!’

Architecturally the great accomplishment was the raising of the enormous central dome (thirty-one metres in diameter) which the architects achieved by a series of devices transferring the great weight of the dome successively onto four pendentives and then onto four huge piers. The interplay of the light which entered through the windows in the dome and walls, with the

51

![]()

splendid marbles and mosaic decoration, and the spatial arrangement of the building, were to overpower and awe worshippers and observers for a millennium. Justinian supplied the capital with a new senate building, public baths and cisterns, and of course with other churches. Second in importance to Hagia Sophia was the Church of the Holy Apostles built in the form of the Greek cross and surmounted with five domes. In the provinces his artistic efforts are still to be seen as far west as Italy and as far east as Mount Sinai. Finally, the imperial architects of the period girt the frontiers with an extensive network of fortresses in the vain hope of holding the barbarians.

As famous as Hagia Sophia, but more significant historically, was the legal monument which Justinian bequeathed, with the assistance of the untiring Tribonian, to succeeding centuries. Though local practice and law were very much alive, the legal relations of Byzantine society formally rested upon the enormous legal repository which centuries of imperial edicts and the legal opinions of famous lawyers had created. Justinian accompanied the simplification and codification of the law with a reform in the textbooks and instruction of law in the schools.

The patronage of Justinian and the splendour of the age were also reflected in the intellectual activity of the capital and the provinces, an activity which was to be largely centralized in Constantinople after the loss of the eastern provinces to the Arabs. Procopius, in spite of his occasional slanders, is the dominant literary figure. In his history of Justinian’s wars he is a worthy continuator of the ancient Greek historiographical traditions. His analysis of the plague which decimated the empire in 542, so closely modelled on its Thucydidean counterpart, is illustrative of the inspiration which Herodotus, Thucydides, and Polybius furnished to Byzantine historiography and which accounts for its superiority to that of the medieval West. Because of this continuity Greek historiography has a record of longevity second only to that of the Chinese. Choricius of Gaza, too, followed the classical pattern in rhetoric by modelling his oratory on that of Demosthenes. In contrast to this archaistic classicism was Justinian’s closing of the ancient schools of philosophy in Athens.

52

![]()

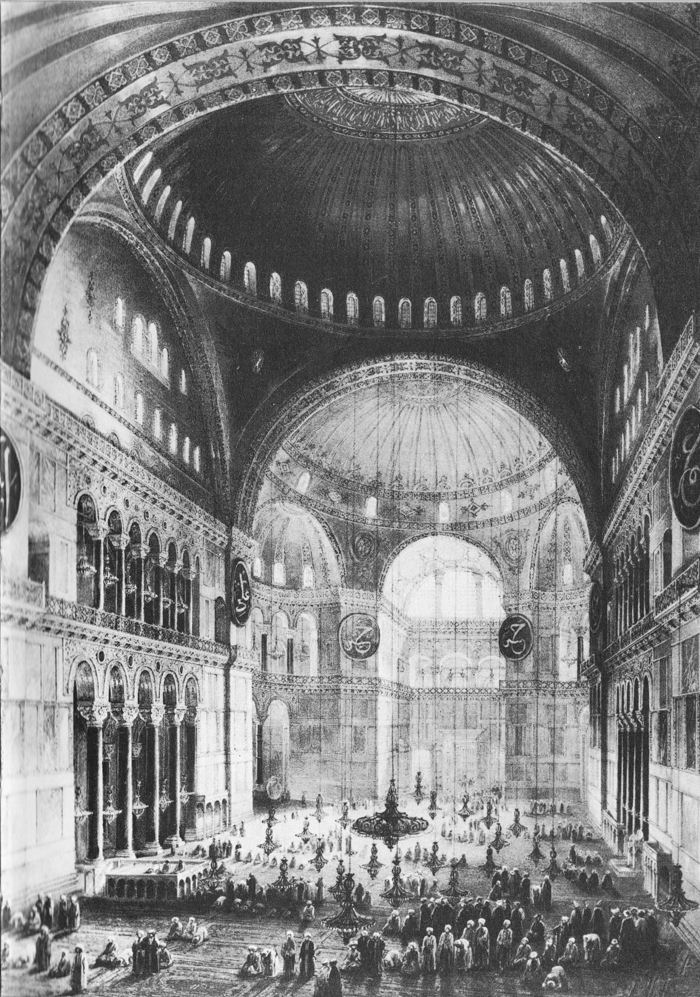

32 Interior of Hagia Sophia, after an engraving made about 1850, which gives a better idea of the scale of the building than modern photographs

53

![]()

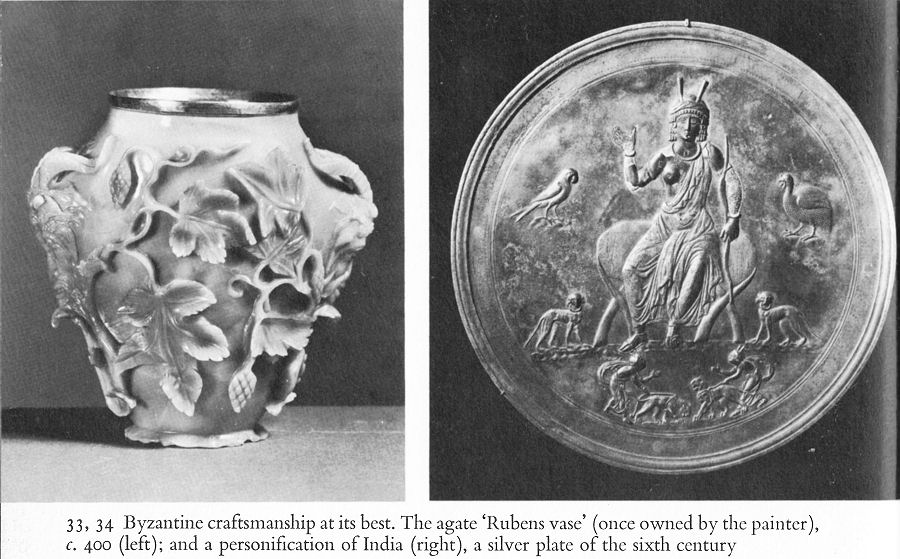

33, 34 Byzantine craftsmanship at its best. The agate ‘Rubens vase’ (once owned by the painter), c. 400 (left); and a personification of India (right), a silver plate of the sixth century

The greatest of the Byzantine hymnographers, Romanus Melodus, composed religious poetry in conformity with the spoken rather than written Greek, whereas the court poet, Paul Silentiarius composed his description of Hagia Sophia in classical hexameters. This development of two languages remained a characteristic of the Byzantine tradition until modern times. The progress of Greek as the official language of the government was well on its way by the end of Justinian’s reign, a process which harmonized with reality.

The evolution which took place in the three centuries between Diocletian’s accession and Justinian’s death had effected dramatic changes in Mediterranean society without causing any drastic and abrupt break with the past. The institutions which this evolution produced had attained political and economic uniformity, but in spite of Justinian’s activity they had not succeeded in producing a religious and cultural homogeneity. These disparate elements effectively hindered the integration of Byzantine society and thus greatly weakened it.

54

![]()

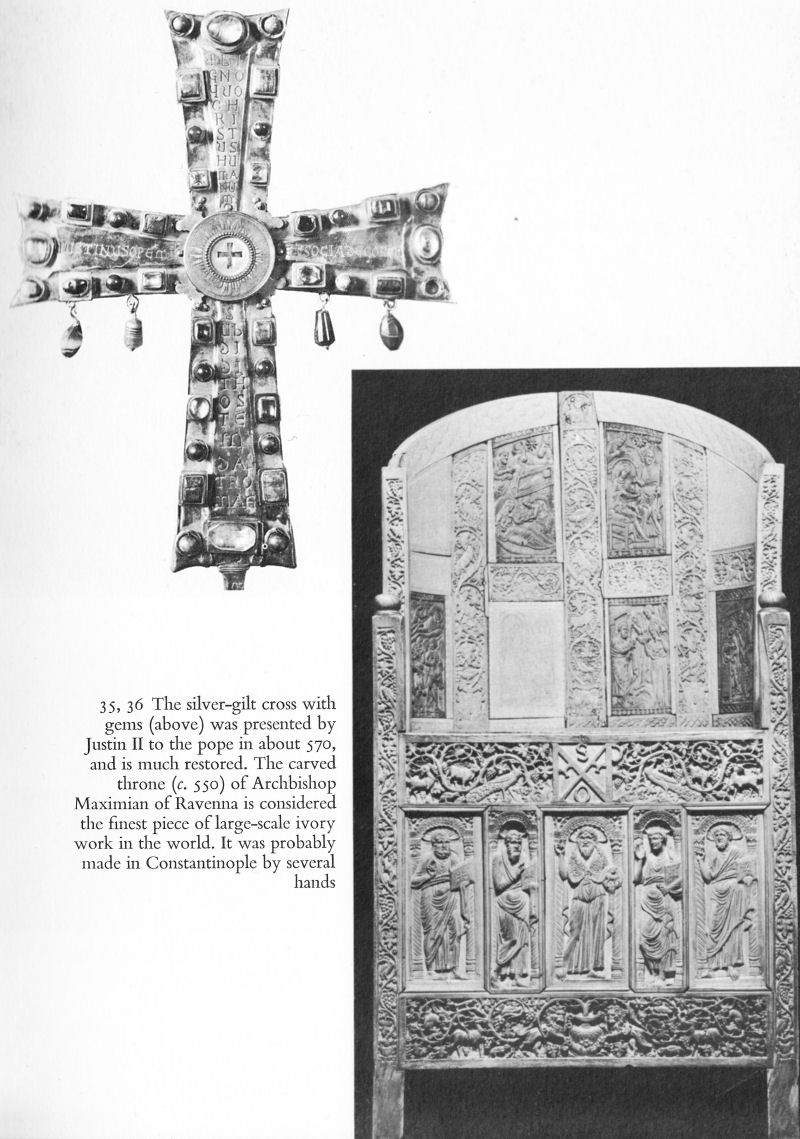

35, 36 The silver-gilt cross with gems (above) was presented by Justin II to the pope in about 570, and is much restored. The carved throne (c. 550) of Archbishop Maximian of Ravenna is considered the finest piece of large-scale ivory work in the world. It was probably made in Constantinople by several hands

55

![]()

37 This multi-solidus gold piece (now lost) was minted to celebrate Belisarius’ victory over the Vandals, but shows the glorified emperor Justinian in military dress