VII. AT WORK

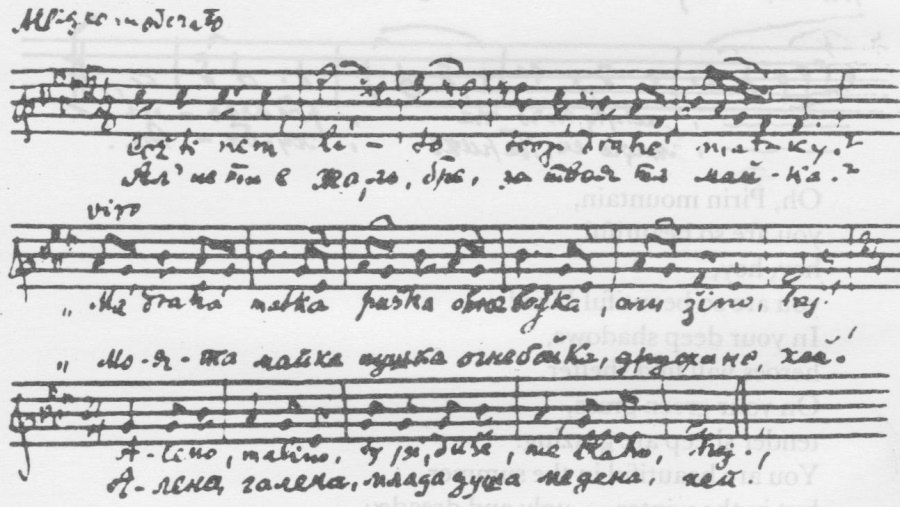

Songs 145

The train was entering the Kachanits gully, through which the Lepenets river, which had carved out a bit of the Shar mountain, flowed from the north. We were hurrying on to Skoplje. I was looking out through the window eagerly. The dazzling full moon had turned the mountain's scenery into a marvelous, enchanting, breathtaking view. Occasionally, the conductor pointed out some detail. For example, immediately after the narrow pass, we were supposed to see Mousa Kessedjia's grave. He was the tyrant that had tormented the region, until he had finally been caught by Krali Marko, and after a persistent battle, his throat had been cut. Mousa had the value of a saint and all who passed his grave threw a coin on it.

The grave appeared for a moment, behind the blazing furnaces of a lime factory. We saw nothing, nor heard the sound of the falling coin, probably because of the noise made by the train. But we stood on at the open window, caressed by the pleasant wind and spellbound by the beauty of the full moon, whose silver seemed to change into yellowish cream in the gorge.

We were released from our spell at the station, by a certain sound. The tracks had shortly left the gorge and entered the large Skoplje marsh (which was malaric, but now looked very beautiful). The sound — a melody — was slightly ruffled, just like the lake's surface when it is furrowed by a swan. We leaned out of the train, bathed in the moonlight, and listened carefully to the acoustic illustration of the magic evening. The melody was plain, but with its burning sensitivity could have melted even gold. We looked downwards and it carried us away completely. Who was singing? I wanted to find him. But the conductor stopped me, "We are leaving!" We could have thrown out our luggage and got off the train, and tried to find the singer, but that night I had to be in Skoplje. I accepted my fate, but decided to come back here from Skoplje. I was so excited that the conductor asked me, "What's wrong?" He had thought that I had lost something.

I disabused him and he did the same for me, "The local station-

![]()

146

master has a gramophone. When a train is leaving the station, he turns it on. That was a Turkish song. He likes them . . ."

Such was our work. Mixups like these were sometimes added to the numerous inconveniences and obstacles. Sometimes, I couldn't help being misled by Edison's wretched invention. I would inquire about the singer and would suddenly find out that it was a machine, the name of which was erroneously (quite often appropriately) pronounced by the Bosnians "gramophan".

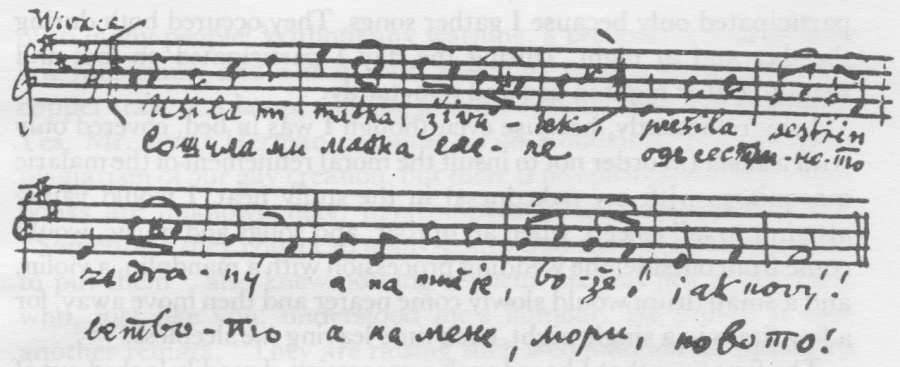

I wrote down the note of the songs best, when I was drawing. For example, in Bitolja, in Koukourechen street, I was drawing in a yard and nearby a girl, which was embroidering, was singing. The South Slavic songs were usually long, and while drawing, I could memorise the simple tune, while the long one I had to make out. When I was acquainted with the whole song, it was usually easy to attract the singer to sing it again for me, while I could write it down.

Of course, it wasn't always easy doing the two things at one time, especially since the tunes seemed so peculiar and so diverse to us.

Let us imagine Macedonia, whose Slavic half was full of scattered around alien islands, and all the towns had Albanian, pseudo- Rumanian, Turkish, Spanish-Jewish, Greek, and gypsy quarters. Most of them differed in their clothing and religion, and therefore in their music and songs. That is why we have to define the term Macedonian song.

I, myself, understand it as the songs, sung by its Slavic population, and the Slavic lyrics are usually enough for me to classify the song as Slavic. Given the existence of such a national diversity, it is difficut for me to usurp the right to determine what belongs to each people and what is a transitional form. But it is no ill fate when one finds some foreign elements in a song of a different nationality. They only show the degree in which the cultures have merged. When a lot of material has been gathered and studied, the solution will come by itself.

From this point o view, the Balkan peninsula is a peculiar place. The diverse cultural currents have not managed to eradicate the ethnical heterogenity. They have not led to the grey, insipid international dough that has been created in all parts that are under the influence of Western European culture. The Balkans are a land of classical individualism, of preserved and clearly outlined personalities, both separately and in combination. The Balkan Peninsula, unlike the Italian and Iberian peninsulas, has never had a

![]()

147

real center, and only the Romans, in ancient times, have conquered it. But the Romans had not been a people, but just an extraordinary cultural and political phenomenon with world power. Unwittingly and at random, they had destroyed nationalism and had replaced it with a forcefully imposed internationalism, whose powerful traces have still been preserved. They had strengthened their power-for as long as they could and had exploited the land. Nothing else had interested them. The Byzantines, together with the exploitation, were concerned only with the acceptance of their rule, which was sometimes quite symbolic. When the Turks, who could serve as an example of conservatism, had arrived later on, they had been content that all had not converted to Mohammedanism, and so an enslaved rayah, which they had needed so much, had remained. Basically, they had left everything as it had been, and their tastes and fashions had not been spread forcefully, but only because of the magic of their charm, picturesqueness, and elegance. Their influence makes one compare the East with the West. The former left everyone to itself and influenced only its feelings, while the latter grossly destroyed mankind's profile and attacked its mind.

The invasion of the Turks, who were full of hatred for the West, had placed the Balkans in a green-house, in which everything could thrive and be preserved.

Macedonia is the Balkan peninsula on a small scale. All its national groups are represented there, and approximately in the same proportion, at that.

Of course, it is necessary to define the term Macedonia, which is now more difficult that it was before the World War. Then, it was a while, and together with Old Serbia, under Turkish domination. One could then say: "Macedonia lies from the Shar mountain and the Serbian Kingdom to the north, to the sea to the south, and from Albania to the east, to the Rhodopes and the Mesta river to the west". But now Macedonia is divided into three parts, of which the smallest belongs to Bulgaria, the largest to Yugoslavia, and the rest to Greece.

The ethnographer's view cannot fight with politics, since the cases when the governed territories correspond to the language borders are extremely rare. The politicians would like to see the language globe as a few large fields, and those fields should be distributed among a few large landowners. But the ethnographer cannot agree to such desires, especially in the Balkans. Each region there is an individual whole,

![]()

148

including Macedonia, which has never stopped being such, even after it was divided, regardless of its internal diversity. It is an ethnographic mosaic, a marble, whose Slavic base is coloured by strips of other elements.

These strips have not merged, precisely because of the conditions in the Balkans. It is not the language barrier, which has prevented their merging, since the people, especially the men, are amazing polyglots. They differ tribally, in their religions, and in their costumes. The latter, especially, represents an insurmountable wall. One can say that the different costumes do not marry each other. There exists an antipathy, an animal, physical, material one.

It is impossible, though, to form any conclusions from this fact, far as the spiritual loneliness of the people is concerned. The fluid of the human spirit is almighty, all-penetrating. In this sense, one may say that interbreeding does exist there. It occurs in waves, unnoticeable from nearby, which manage to preserve the outer shape, but penetrate in its content, and possibly, might change it, just as it happens in the earth's crust. It is not a leveling influence (such is the influence only of Western Europe culture), but one with a limited effect, or rather a refreshing influence. As with the gardener, who artificially exchanges the pollen. The flower remains the same, and only the tint has changed.

The shapely, diversified form of the Macedonian song, which is basically in one voice, but is rich in keys, is derived from here. The rhythms, whose richness originated in the west, near the Morava river in Serbia, which was the border of the former Bulgarian regions, and moved to the east, are numerous. In this respect, the Macedonian song is an inseparable part of the Bulgarian song.

The structure of the melodies and the verses is unrestrained and the metric versification inexhaustible. Melodically, the song is still alive, i.e. variable, while the lyrics are comparatively constant, since they are connected with a given territory or a given ritual. The songs which may be sung everywhere and by everybody are more variable and offer numerous versions.

I mentioned the pollination of the flowers with foreign pollen. Here, there also exists an element which performs the role ofa wild insect — the gypsies. Able to perform any work, they are musicians first of all. No one can do without them, neither Christians, Moslems, Albanians, or pseudo-Rumanians. A gypsy orchestra must participate in every

![]()

149

festivity, fair, wedding, or any other event. It can play for anyone. Actually, a gypsy, accompanied by a couple of his compatriots, can supply the whole Balkan peninsula with a musical mixture, which at present cannot be separated from the original.

But even they cannot do so, that everything which refers to music can merge together. The fact that their musical instruments are never used by the Slav or Albanian peasant is very interesting. They may listen to a drum or a zourla, but will never use them, just as a gypsy will never use any of their instruments. They are the bagpipe, with a wooden pipe (possibly double), the "doudouk" [*] and the "loukarina" [**], for the Slavic peasant, and the "kaval" [***] for the Albanian one.

The instrument, called in our country a "Serbian gousla" [****], is not met here at all. I also did not see any of the two versions of the "tamboura" [*****] — the "shargiya" or the "bougaria", except if they were used in Turkish homes, to which I had no access. But on the other hand, I discovered a small three-stringed instrument, which was spread all over the Balkan peninsula — from Dubrovnik, through Albania and Macedonia, as far as Bulgaria, where it was called "gadoulka" (which translated in Czech means houdelka, i.e. a small violin), while in Dalmatia it was called a "lyritsa".

The melodies of the southern peoples, despite the radiance and the warmness of the sun, are usually sad, compared to those of the northern peoples. The gayest local tunes would sound mournful to a northern man, and vice versa, our saddest songs are a clear sky compared to the dismal clouds of the passionate moans.

The Macedonian song makes no difference, but with it this phenomenon can be understood only partially. The great shyness of the women and the girls and the fiery songs of the soldiers are a witness to the conditions in which Macedonia and Old Serbia have existed — of all Slavic peoples they have longest been under Turkish domination. Macedonia's future fate was also unhappier. It had

*. doudouk — a wodden pipe

**. loukarina — a stringed instrument

***. kaval — a wooden flute

****. gousla — a rebec

*****. tamboura — a pandore (Translator's notes)

![]()

150

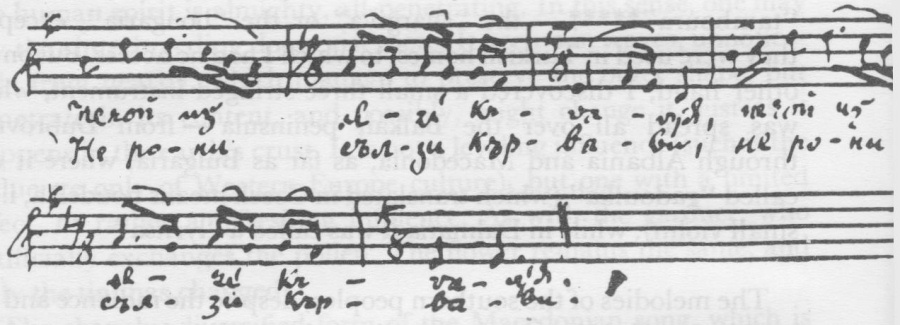

fought not only against the Turks, but against the Greeks as well. But the most painful part was that because of the vagueness of the language borders, it had been drawn into the fratricidal Serbian-Bulgarian War. It is easy for the passionate southern blood to find itself an attorney — gunpowder and lead. So we must not be surprised by plaintive songs, as this one, for example:

Three shots were fired,

three heroes,

Oh, my God,

have fallen,

three mothers,

Oh, my God,

are crying,

It is difficult to console the miserable girl:

Don't cry, young girl, don't cry!

Don't shed tears of blood,

don't shed tears of blood!

"How can I not cry and lament,

how can I not shed tears of blood?

We have just heard the sad news,

our father, the Turks have beheaded."

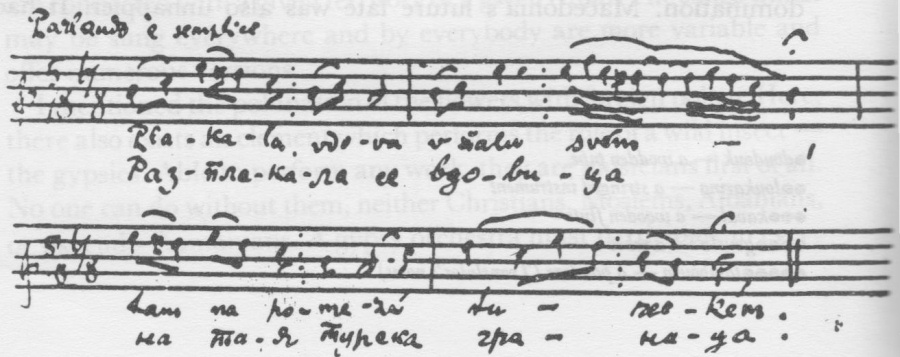

The next song describes the fate of the hero's wife:

---------

![]()

151

A widow was crying

on the Turkish border.

"Stand up, stand up, Oh, Stoyan,

look at your miserable wife,

look at those seven, eight orphans,

one still in its cradle!"

"I cannot get up, my dear,

a Turkish bullet prevents me it

went right through my hear."

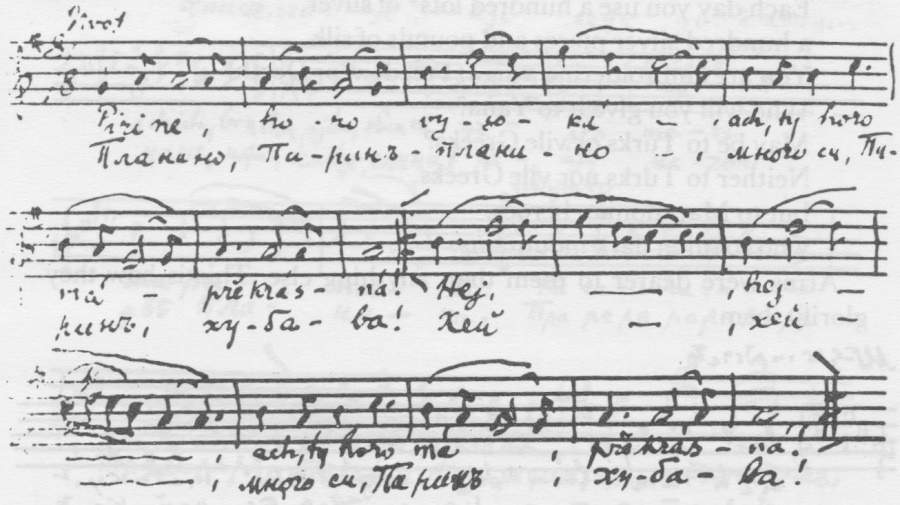

The "comitadjii" (insurgents) always gathered in the mountains in the spring. The Pirin mountain in Bulgaria has become famous song because of this. This song tells us about it.

Oh, Pirin mountain,

you are so beautiful,

hey, hey,

you are so beautiful Pirin!

In your deep shadows,

heroes will find shelter.

On your green grass,

tender sheep are grazing.

You are beautiful in the summer,

but in the winter — ugly and dreaded.

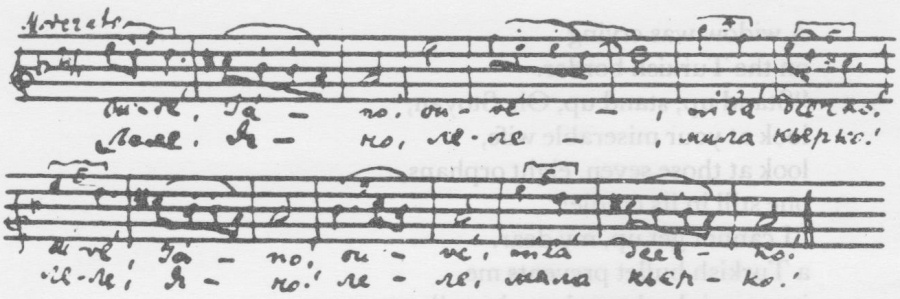

The next song gives an example, how the revolutionaries have created a political patriotic song by slightly modifying a folk song:

![]()

152

Oh, Yana, Oh, dear daughter!

You are always sitting by the window,

embroidering a Macedonian flag.

Each day you use a hundred lots [*] of silver,

a hundred silver pieces and pounds of silk.

You are embroidering a sign: Freedom or Death!

Who will you give it to Yana?

May be to Turks or vile Greeks?

Neither to Turks nor vile Greeks,

but to Macedonian heroes,

who roam in dark mountains.

Arms were dearer to them than anything else. This is how they glorify them:

*. Lot — an old weight measure. Author's note.

![]()

153

Don't you miss your mother?

"My mother is my blazing gun!"

Don't you miss your dear sister?

"My dear sister is my sharp sword!"

"Don't you miss your dear brothers?

"My dear brothers are the small bullets!"

Don't you miss your dear beloved?

"My dear beloved is the green forest!"

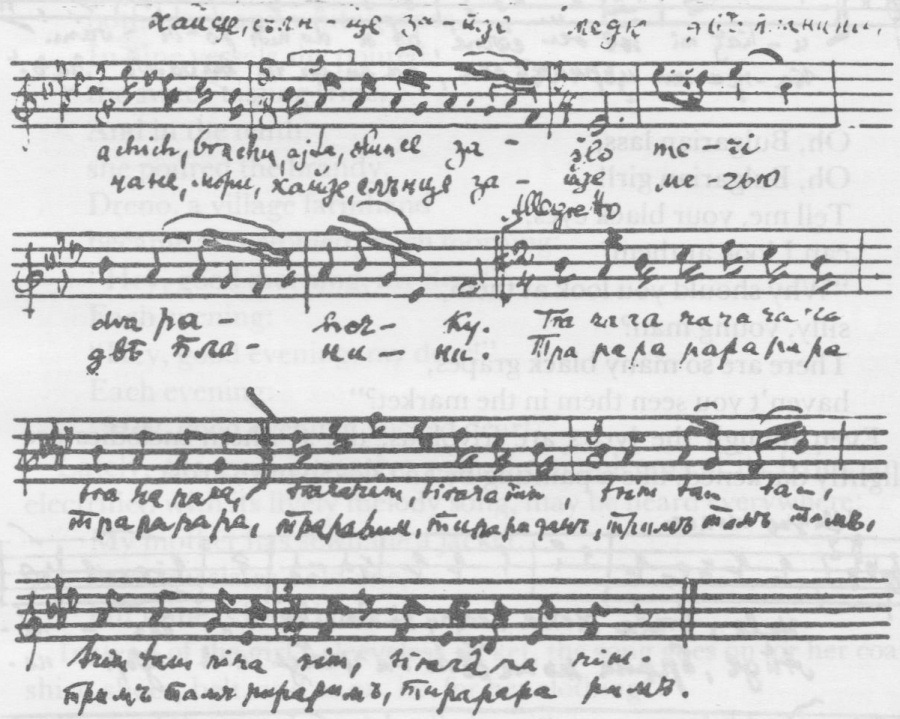

If the heroes are sometimes having fun, they sing a witty, mocking song, spread all over the Balkan peninsula — from Macedonia to Bulgaria. It is the song of the wounded hero, who is moaning with pain:

Come on, the sun has set,

between two mountains.

And between two mountains,

the meadow is green.

Lets go to the meadow

where the poplars are tall.

Lets go under the poplars

to see what is there.

Under the poplar,

Bogdan is lying ill.

His tooth is aching,

a filigreed tooth.

Come on, let's call

a strong barber.

Let him take pliers

from the blacksmith!

![]()

154

In order to pull out,

the filigreed tooth!

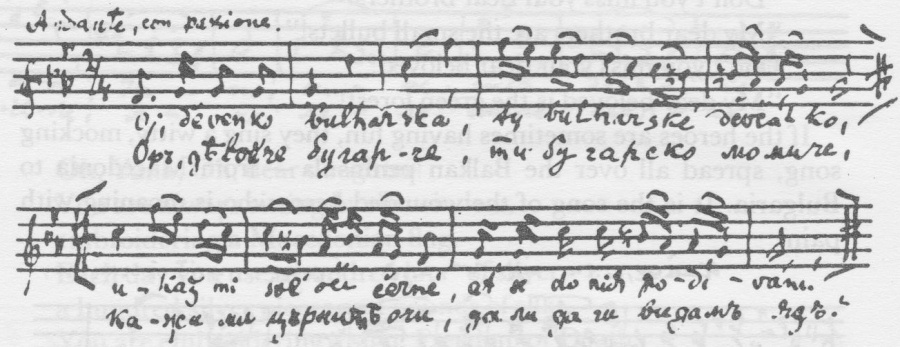

The comitadjiis may rarely hum a love song with an impressive melody, expressing the temperament of the southern people:

Oh, Bulgarian lass,

Oh, Bulgarian girl!

Tell me, your black eyes,

can I look at them?

"Why should you look at them,

silly, young man?

There are so many black grapes,

haven't you seen them in the market?"

Even though the lyrics are frivolous, the southern melodies are slightly darkened, like a painting by an Old-Spanish artist.

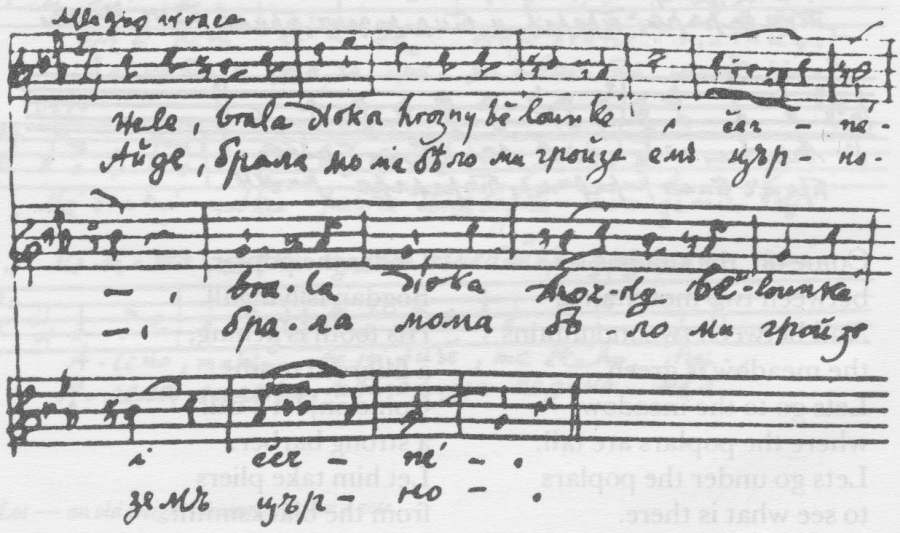

![]()

155

A girl picked white,

both black and white grapes.

In nine vessels she poured,

the sweet-tasting wine.

And in the tenth,

she poured the brandy.

Dreno, a village farmhand

became accustomed, Each morning:

"Hey, good morning, my dear!"

Each evening:

"Hey, good evening, my dear!"

Each evening:

"Hey, good evening, wicked dear!"

Lately, the gay, attractive with the simpleness of its lyrics, and electrified with its lively melody song, may be heard everywhere:

My mother has sewn me a jacket,

from my sister's old one,

but mine is brand new.

Instead of the girl's sleeveless jacket, the song goes on for her coat, shirt, shoes, belt, and so on, i.e. for her clothing [*].

Some of the songs may be called wedding songs, and I can speak of sleepless wedding nights with a full right, but I don't want to arouse any unrealizable hopes in the reader.

They portray numerous and endless processions through the winding and uneven streets of the spread out towns, in which I have

*. See "Macedonian Songs", for singing and piano, with full original texts and Czech translations by Jan Houdets (book XIV "Slavdom in my songs"). Author's note.

![]()

156

participated only because I gather songs. They occurred both during the day and at night. During the day I participated on foot and readily, but at night in bed and reluctantly.

I say reluctantly, because even though I was in bed, covered only with a sheet (in order not to insult the moral refinement of the malaria mosquitoes with my nakedness) in the stuffy heat, I would vainly attempt to fall asleep, when an uproar, and songs and music, would come from outside: the wedding procession with a mandolin, a violin, and a small drum would slowly come nearer and then move away, for a few times in a single night, each time leaving me sleepless.

The first time that I heard such a procession, I readily looked out of my window, and while still dozing I even thought of going out on the collapsed balcony, but I remembered the inn-keeper's warning. When later on, when I was desperately trying to cling on to the angel of sleep, and was already half asleep, and again heard the same two or three melodies, which by then I knew by heart, my passion for research began to dwindle. I did not accompany the tunes and the melodies with a specialist's attention, but with a grinding of my teeth and a quiet cursing instead.

I remembered my happiness, when in the morning I had learned that I would be able to see a wedding ceremony in Strouga, with a bitter smile. Now, tossing in the red-hot bed, I was straining my mind vainly, trying to solve certain human mysteries, as for example: why does the heat attract sleep during the day, but repulse it during the night?

And all that, had occurred on the day before the wedding, which would be on the next day, and would go on for a few days, and, Oh, God, for a few nights! What a disappointment! Or may be all that was supposed to make one's impressions of a wedding complete?

The wedding in Strouga (a town, situated on the northern shores of the wonderful and charming Lake Ohrid) started well and interestingly. It was a Sunday and the sun was shining, while the whole sky seemed to be laughing, and with it the whole town. The people, most of all the women, were standing on their doorsteps and at street corners, expecting the procession. It soon appeared and passed along.

It was still not the wedding. Only the bride's gifts were being taken to her.

I was so sorry that there was no master as our Ignat Herman to describe how a wedding in Strouga managed to capture the attention

![]()

157

of so many people! Without any warning, a procession, headed by a few musicians, and a man with a shining vase, a brass pitcher, a copper tray, or a lamp, walking proudly behind them would appear. Yes, Mr. Ignat Herman, a lamp! As on Kondelnik! It looks like a plagiarism of our gay creation, but there is no spiritual robbery. Your books are unknown here. My companion, who whispered to me, "Sometimes they collect so many lamps that they don't know where to put them", also knew nothing of them. He was just a jolly man, who, just like you, understood life's humour. He proved it with another remark, "They are raising such a commotion for those gifts now, but just wait till after the wedding, it will be much bigger then ..."

When, around noon, we had gathered in a large semicircle in front of the bride's home, a procession was formed. A patient horse stood in its middle. The bride's dowry was carefully arranged over it, with visible pomp. The carpets and silk covers, whose yellow and red colours shone brightly in the burning sunlight, were tied on one side; the trunk, containing the underwear and the clothing, on the other. On top of the horse, between the two, a few small pillows were placed. The name pillow was not quite appropriate, since they were used for sitting. A three year old boy, with full cheeks, was seated on them, so that the first-born child of the couple would be a boy (that was a remnant of the past, when a boy had meant Cupid).

When the couple appeared on the doorstep, the father threw sugar cubes and small coins over them, and the procession was divided in two. The horse, with the smaller group, took the valuables to the groom's house, while the bride and the groom went towards the church. Strouga's church was very big, but it was difficult to stay inside because of the heat and the crowd. We didn't wait until the end because the Orthodox Church had a weakness for long rituals. We stayed only for the consecration and the throwing of the wheat, and heard the questions and the advice, which were directed to both, but mostly to the bride.

It was interesting, since the role of ministrant was given to a boy, who resembled Jesus at the age of twelve, except that he did not seem to be as wise, and who with superhuman effort was trying to be serious. With a comic braveness and a charming self-importance, he was trying to alter his boyish alto into an old man's brass, and with an inexorable sternness, was telling the bride to obey her husband and to

![]()

158

always be faithful to him.

When we heard those facetious words, we were sweating all over in the heat and our strength failed us and we had to leave the church.

In the late afternoon, we were walking along the Drina, which flowed through Strouga, and unwittingly happened to pass by the couple's house. The young people were dancing a chain dance outside, in their honour, and the bride was looking through a window in her silk clothing. We couldn't guess what her feelings were, while she watched the fun outside, since her face was hidden by a long veil, which suited her.

A veil always suits a bride. It is a curtain, which hides the future of the young couple.

Soon, we were not able to see her any more. She was hidden in the dust, which was raised by the feet of the dancers.

When it started covering my notes, we set off homewards, in a sad mood. We were not moved even by the image of the day-dreaming bride, since we had been seized by a fear for our sleep. How were we going to sleep, if the weddings here lasted for such a long time? "Oh, not, southern nights," we sighed in advance, "so short, and still so long to live through!"

Our sighs were partly unnecessary. We had only one bad night. A fire, which destroyed for buildings, broke out on the next day, and the whole town was so frightened that everyone quickly forgot the wedding.

I could never have imagined that man could be so cruel, if I hadn't felt it on myself. Even though I was still seeing the terrified and desperate figures, when I fell exhausted in my bed in the evening, I almost said to myself, "Thank God that there was a fire . . ."

After all, we, people, are great miscreants!

The Artists Grievances and Idle Chats

Idle chatter? Why not? But grievances? Why? After all, from the very beginning I had achieved one success after the other easily, and had had only one fear — that I might stop working altogether!

What I am saying is no nonsense. Too much of anything, including success, is harmful. Once you have reached the peak, you have to start down the other side. It is the law of the turning wheel, relieved of the

![]()

159

depressing prejudice — which is "up" and which is "down" — which is also a certain state, even though it is inadequate for ordinary life, since it creates only confusion and disorder.

The clarity of this not very clearly stated thought suddenly struck me as I was reading this, I admit, rather confused, story.

I was going to visit places to which no artist had probably ever been, and I had no idea what would happen to my work. And there I was! Our luggage, covered with a thick layer of dust, was still tied to the car, when I suddenly had a model! And what a model!

It occurred during my first stop in Strouga, a town which was comfortably situated on Lake Ohrid. We had arrived from the north, through the valley, which had once been a battlefield for the Slavic- Albanian hero Skenderberg (as the remains of his castle indicated), and which was now a border between Albania and Yugoslavia.

We had hurried off early in the morning from Skoplje, on our way to Ohrid, and it was not surprising that we had stopped here. The more so that our driver had relatives here and we would be served fish. (All the way from Gostivar we had not seen a decent restaurant!)

Strouga, an ancient "panagiurishte" (market), would have been the most luxurious place in the world, if it had that which it lacked, and had lacked that which it had.

It was famous with its malaria, first of all. When I asked a local clerk how he managed to live here, he said, "Each month I receive 2500 dinars plus malaria". Then came the famous fish, mainly trout and eel, towards which one could feel not only love, but also respect, since they were subject to a state monopoly, and therefore twice as expensive and rare. One could eat only fish caught by poachers. Finally, Strouga was famous as a prototype of the Czech Varvazhov, whose women sand of themselves: We, the women are all beautiful, because we are from Varavzhov. Koulaskova is also beautiful, because she is from Varvazhov.

Such a statement was also valid tor all local daughters of Eve.

I did not dig into the validity of the statement, but I must admit that it was true for the first Strouga woman, which, figuratively said, fell into my lap (as an artist, of course).

It happened thanks to the innkeeper. When he heard that we were going to Ohrid, he proposed that we stay for a while in Strouga and

![]()

160

showed us his rooms. When I promised him that we would come back, he asked us how long we plan to stay. I told him that it depended on whether I would be able to work. He asked me what work I had in mind, and when he heard that I wanted to do some drawing and to publish a book of paintings from Macedonia, he suddenly became eager.

"You must draw my wife! You will be amazed to see how her Sunday clothes suit her!" And he immediately began describing her enthusiastically. "I will find you other people to draw, as well," he added, not sounding like a husband in love any more, but like an enterprising middleman.

I had liked the idea, and started looking around secretly, trying to spot my model, but all was in vain. Krusto prepared the fish and served his guests all by himself.

But there was no reason not to believe him and since our driver confirmed everything that he had said, I returned a few days later with my equipment.

Golubenka, that was the name of my model, was really a charming woman, with large, brown eyes and bravely arched, almost grown together eyebrows, leaning on the tenderly moulded nose, as on a large column. Her face had pleasant outlines, and the curving, red lines of her lips stood out.

She sat before me sideways, her hands on a brocade, blue apron with large, golden, acanthus leaves, her breasts were in a tight, red, sleeveless jacket, and her bell-like, wide sleeves were edged with heavy, golden embroidery. Her pink scarf was weaved into her hair and fell beautifully on her back. It completed the image, which both I and her husband watched with delight. Whenever his duties allowed it, he would come over to us, would sit down and watch the movements of my brush, in the air and on the canvas.

I began working zealously, since in such cases one never knows when the posing might abruptly cease, and I was very happy, when after almost two hours, during the break we took, my canvas aroused Krusto's and Golubenka's admiration.

With it, my happiness reached its peak. My successes continued, but the horizon of happiness began to cover with dangerous clouds. The spouses, after a short and quiet discussion, made a flattering, but at the same time murderous, offer — that I should sell them the painting when it was ready.

![]()

161

That was a heavy blow. Fate takes its revenge with pleasure, if we turn our backs to its smile. If I refused, Krusto probably would not find me any other models. But an evasive answer would also have undesirable consequences. Also, I didn't want to part with the good people with had feelings. It wasn't their fault that here, for a full day's hard work, the wages were ten dinars. Than what could I do?

It wasn't difficult to dissuade them. But what I had expected happened — in my room I had neither the necessary calm, nor the necessary responsiveness any more. And I, with a bad foreboding, speeded up my work and limited myself only to the most essential things, so that I would be left with that, which could later be finished without the model.

I had guessed correctly. She did not come in the afternoon and Krusto excused her. He seemed perplexed, though. I had been prepared for that and thought of going back to Ohrid. But Krusto, whether because he wanted to keep his word, or because the businessman in him prevailed, found me two interesting old ladies, one of whom I started drawing right away.

Again I had success, and again it was breathtaking and staggering! This time, it was even greater, since the granny looked upon me not as an artisan, but as a gentleman. For sitting comfortably for an hour, she would receive as much as a worker for a full day's work. She wanted me to give her the picture as a gift. She wouldn't take it for herself, but would give it to her children. So that they have a memory of me," she explained with a childish smile.

It was my second Pyrrhic victory in a day! I really had to leave! What would happen if I continued having the same luck? I would have to say good-bye to Macedonia altogether!

On the next day, I started drawing the other granny with great fear. I worked quite hesitantly. I was afraid of being successful again, and the innkeeper's attitude was becoming more hostile all the time. Unwittingly, I was slowing down my work, postponing the moment when it would be completed. At noon, I let the granny go and engaged her for the afternoon only because I wanted to delay the fate which was inevitably awaiting me.

But fate was merciful towards me. Unfortunately, it wasn't merciful towards the others. Towards them it was cruel.

We had just started working in the afternoon, when from outside we heard a commotion, screams, desperate shrieks, and shouts: "It's burning!"

![]()

162

It was the house across the street, which belonged to Krusto (he was running the inn under a lease).

Soon, four buildings had been engulfed by the flames. We saw how the innkeeper helped his mother and the fainting Goloubenka out of the burning building.

All his belongings were left inside. "My cow, as well", he told me on the evening after the fire. Everything kept falling out of his hands. He was trying to open a bottle of wine for one of his guests, when the bottle exploded in his hand, and pieces of glass cut his face, so that it was all in blood. He want to the basement for some cherry-brandy, which he made by himself, but he toppled the vessel, his candle went out and the brandy was spilled.

He sat beside me, pale, with deep-set eyes and a bandaged head, and said, "I dare not touch anything else today. Today is my day of misery".

We packed our things that same evening and left on the following morning.

When we were saying good-bye, no one even mentioned the drawing. Poor Krusto had other worries.

So "vis major" had helped me out of my difficult position.

It is rejected in literature, where it can bring no harm to anyone, but in real life it constantly rages. If I could, I would introduce the opposite order.

-----------