VIII. MISCELLANEOUS

Macedonia 171

As I hear, our Ministry of Railroads has decided [*] to introduce soaps and towels in the express trains, tentatively at first, to see if our educatedness can be complimented in such a way. The soap, just to be sure, will be sticky, so that no one will be able to put it in his pocket. Therefore, the trial will be made only for the towels (or may be, if the soap is liquid, a risk that someone might drink it, exists?).

This is not a laughing matter. It reminds me of Macedonia, an unfortunate land, because while all sorts of weird ideas of it exist, disturbing information comes (and still more doesn't come) from it all the time. The soap and towel matter intrigued me precisely because of it. No matter which inn we had spent the night in, there were always a few bars of soap and a couple of towels (once we even saw a common toothbrush) on the common washbasin in the corridor).

So people don't steal there. In countries where one easily takes a rouchnitsa [**], one never takes a rouchnik [***], except to dry his hands. In the "insecure" regions there always exists security. One might forget something, but it will be sent to him through mountains and valleys. "Order" is achieved only through education, when locks are introduced everywhere, mutual distrust is legalized, and suspicion becomes a basis of public peace and "security". And we are not offended by all this, but on the contrary, we are infinitely pleased by it. Mutual suspicion binds us into an indivisible whole, and we then take it with us to most inappropriate places. And that is why we are punished, as I was once myself. I am still ashamed of what happened.

I was leaving a Macedonian monastery, almost forgotten in the mountains and when parting I said to the abbott, "I still owe the mayor of the village D. 80 dinars for lending me horses. He didn't want to take the money beforehand, but said that I could pay him

*. Written in 1928. Author's note.

**. Rouchnitsa — a rifle (in Czech). Translator's note.

***. Rouchnik — a towel (in Czech). Translator's note.

![]()

164

when I returned. Since you advised me to travel along a different route, I sent it the day before by Risto (a twelve year old shepherd). But Risto hasn't told me yet whether he has given the money to the mayor, or ..." I couldn't finish. The abbott smiled so delicately, and waved his hand so softly, that it pierced me right through. I turned red, and I deserved it. Why, from my own experience and from what I had heard from others, I knew the Balkan people.

A pharmacist, who was a Dalmatian, was once telling me in Bitolja how during the fatal explosion of the arsenal, in 1922, all had to leave the city, while the explosions lasted. For three days and three nights they camped out of town. "We left everything unlocked, because we had no time to lock up. When we returned, everything was in its place and nothing was missing".

Of course, I once saw a man who mounted his horse and placed a rifle across his knees, in Strouga. I asked my innkeeper, "Why did he do that?"

"Because he has not only wealth, but enemies as well. You can travel around without a single worry. Nothing can happen to you" (i.e. I had neither).

It was true that the smell of gunpowder and the romance of the battles, of old, Medieval times, were preserved, due to the lack of a legalization of the relations between the people. Jurisdiction, especially in Turkish times, had not been developed enough so that the people could depend on it. They, as much as they had been able, had become used to seeking justice on their own. The spell of tragedy and great deeds, the dreams of courageous acts, which could not be achieved without bloodshed, still existed and were innate in everyone. Everything was gradated in martyr's aspirations. Not only the form of the crimes, which in their essence were a struggle, but the methods of political struggle, too, were derived from them. The vendetta, which was widespread among the Albanians, existed also elsewhere, and the charm of the folk songs still had a great impact on the life and rich, spiritual make-up of the people. They dreamed of great deeds and base treachery was unknown to them.

Once, I spoke to one of the local people, who was acquainted with our conditions, and I reproached him for the way they carried out their political arguments and struggles. He said, "And is it better in your country, when someone can he disgraced in a newspaper dispute, in a court trial, or in any other way, for an insignificant sum.

![]()

165

I didn't know what to answer. I only knew that the soap and the towel were safer there than they were in our country. The people there washed their hands with them, while here, they would sooner dirty them.

Actually, this chapter should have been called "The Given Name in its Ancient Form", which form is still preserved in the Balkan peninsula, mainly in its southern part. But since this work allows me to mention their famous Novaks, and since we have unanimously accepted the view that all the numerous Novaks are representatives of the branched Czech nation, I am using the more contemporary title in order to attract some attention to my story, which I suppose will be an interesting discovery for our Novaks. And, most probably, not a pleasant one. Even though I leave aside the doubtful problem of the origin of the Czechoslovak Novaks (still more the Lugii and Polish ones), I don't know if this narrative will please them. It is otherwise interesting, since from it one can conclude that there is no such thing as a common origin of Macedonian and Czechoslovak Novaks. And ours should know that-they can hardly serve as an example to the Macedonian Novaks. True, ours also have things to be proud of. There is hardly a ministry in our country which doesn't have one. (In one there were even two, which I already call a representation).

But this glory — let the gentlemen ministers forgive me — is nothing, compared to the historical fame of the Balkan Novaks, since as far back as 1883, a book (by an unknown author) with the meaningful title "Stazina Novak in Folk Songs". History tells us of Kesar (Caesar) Novak, the third highest, (after the Tsar) dignitary in the Byzantine Empire, who has left a lasting mark in the history of art, by building the wonderful church on the memorable island of Mali Grad, on Lake Prespa, where, in the beginning of our millennium, the seat of the glorious Bulgarian-Macedonian Tsar Samouil had been.

Therefore all the mentioned Novaks are good people, since they have been sifted out by history.

The first among them had been, as far as I know, a famous blacksmith, He had been so deft that he had forged Krali Marko's famous, dramaturgical sword. When it had been ready, it had first

![]()

166

struck its creator, i.e. Marko had cut off the blacksmith's right hand and said:

Oh, blacksmith Novak,

you have to work no more.

Take these 100 doucats,

they will feed you for the rest of your life.

The sword also had an interesting fate, which is described in another song. It tells us that a young man, who was lying wounded, had asked a passing Turk for help. But the Turk, seeing his wonderful sword, had cut off the young man's hand. He had taken the sword to Istanbul, where he had boasted with it in the court. Marko, who had been a nobleman there, had also seen it. He had looked it over carefully and had read an inscription on it: Novak, the blacksmith, King Vulkashin (Krali Mrko's father), and Krali Marko. In the next moment, the Turk's head had rolled on the ground.

History seems to have quite a bad orientation for the rest of the Novaks, since whenever it is present at heroic deeds, it does not pay much attention to the system of chronology (which has at least a little importance in history) and gathers together representatives of different centuries. For example, present at Georgi Smeredevets's (Brankovich's) wedding in Dubrovnik were Novak, who was matchmaker or best man, Sibinyan Yanko (Jan Houniadi), Relyo Krilati, Milos Kobilich, Milan Toplitsa, and Krali Marko. The whole group is both a chronological and geographical omnium-gatherum. That, of course, is not the point here. What is important for us is to show to our Novaks in what company the song places our hero. Without exception, they all are distinguished heroes whose feats have shaken both Serbian and Bulgarian folk songs.

With the exception of the blacksmith, all the other Novaks have a surname, added to their given names: Starina (Old man), or Debeliak or Debelich (Fat man).

There is a song of a Starina Novak who had no sons, but only a daughter Yana. Once, when he was very old, he had been called to served as a soldier and his daughter had gone instead of him. She spent nine years there and no one had guessed that she had been a girl. In another, similar song, the girl is called Rouzhitsa. Someone had begun to suspect her, and an interesting check had been performed, so that her sex could be determined. But since the check had not gone beyond the limits of decency, the girl had managed to

![]()

167

keep her secret.

A Bulgarian song, written down by me in Bachkovo, in the Rhodope mountains, in which a girl was called Mariika, tells us what sorts of checks had been performed:

Who has ever heard of such a thing,

of a voivoda who is a girl.

with seventy heroes,

she is the seventy first.

Her name is Mariika.

The young men knew not what to do,

but they finally agreed,

"Lets go and check!"

They started making pipes,

pipes and motley distaffs!

"Ifour voivoda is a man,

he will grab a pipe,

but if she is a girl,

she will reach for a distaff."

But Mariika was smart.

She did not reach for a distaff,

but grabbed a pipe.

Starina Novak, who has been studied by historians, had lived in the Kachanitsa gorge, on the Lepenitsa river, near Skoplje. He was a Bulgarian and as a "haidouk" had attacked the Turks from the Bulgarian mountains. He had also fought against the Magyars, and during, a campaign against Zigmund Batori, had been captured, tortured, and finally burned.

All this can be read in many different books, of which I will point out Vuk Karadjich's glorious collection of Serbian songs (parts II and III) and Kachits-Mioshiche's "Viennats". I will now proceed with the most important part of my story, the part of the highest of the Novaks, the Caesar.

Caesar Novak!

I believe that the combination of the name Novak with the high title will seem funny to anyone, and not only to me. The name Novak somehow does not seem appropriate for the title Caesar. But why? Is it not worthy of such a title?

That is not the reason. We are accustomed to hearing Christian names together with ruler's titles, and not surnames, and the name

![]()

168

Novak is a surname in our country. That was why it sounded so funny when we called the Austrian Emperor "Prohazka". [*]

But with the southern Slavs the name Novak is a given name. And there is nothing wrong that it does not come out of the calendar. Such a thing makes no difference there. A priest is never taken aback, as he is in our country, when he hears an "un-Christian" name, whether it is Prjemisl, Libousha, or Vlasta. They have a lot of un-calendar names, especially in Macedonia: Grozdan, Nedelko, Tsvetko, Mille, Soloun, Tvirtko, Dragan, Predrag, Zlatko, Liuben, Rada, Roumena, Stamena, Sossanka, Dzvezda, Dardana, etc. The Bulgarian composer Dobri Hristov is well known in our country, but it is impossible for someone here to be called, for example, Vesseli Dostal or Popelka Koubatova, Kvet Nezavdal or Chervena Hlavsova. The parents will not allow their son to be christened Vesseli or Kvet, or their daughter Popelka or Chervena. Only through sympathy for the South Slavs have the names Zorka and Draga been adopted in our country lately. But in the Slavic south, the religious names have never been predominant. It is interesting that at the beginning of Christianity they had achieved some popularity, but mostly Old Testament names had been prefered, as Samouil, Aron, Simeon, etc. Constantine Jirecek believed that the belligerent Bulgarians had preferred the mighty heroes of the Old Testament to the gentle apostolic figures of The Gospel.

Another peculiarity is that the given, or Christian, name, whether it is secular or religious, is always the main one. One lives mainly with it. Ask anyone "What is your name?", or "What is his name?", and you will always be told the given name and not the surname. Just as it had been a long time ago in our country.

The leading politicians in Serbia are called, without exception, Velya, (Voukichevich) or Liuba (Davidovich). Friendship knows no other form of address. In Kossovska Mitrovitsa, in Old Serbia, the mayor, who was a former teacher, told me, "I once knew a Czech, the officer Zhizhka". He started rubbing his forehead and angirly exclaimed, "I've forgotten the surname!" Once, while riding on a train, I told a few peasants that I came from Prague. They immediately asked me if I knew a certain Pepa. "He is a good man. He comes each autumn to buy fruit. His name is Pepa." In Prizren, we asked for professor Kostich, an old man of eighty who had lived there all his life.

*. Prohazka — promenade; surname (Czech). Translator's note.

---------

![]()

169

But no one knew him. It was after I had said by chance Petar Kostich that the local man shouted out: "Ah, Petar!" And, of course, he knew him. Our compatriots also got used to using given names quickly. At a station near Skoplje, we visited the station master and told him that Mr. X had sent us to him. Mr. X was Czech engineer who had lived in Skoplje for the last 15 years. "I don't know him", shook his head our compatriot, when he heard the surname. We tried to describe him, since it was impossible that the station master would not know him. We also explained where he lived, but all was in vain. And suddenly, our compatriot exclaimed, "Frantishek! That's Frantishek. Now I see what he was trying to tell me, when he passed through the station today. I couldn't understand him. He must have been telling me of you!"

And, of course, there arose difficulties when I wanted to write down the name of the person I had drawn. I asked an old lady, "What is your name?"

"Soultana", she answered.

I wrote it down and asked, "and the other one?", but she looked at me in surprise. After some time, I learned that in order to ask for a surname I must ask a woman not what her name is, but whose she is. She is her husband's, and if he is called Krusto, she is Krusteva. The men had father's (middle) names. Tvirtko Ivanov's father, for example, was called Ivan. But that's not all. We have now reached the same stage as when a Russian has told us his given and father's names, Pyotr Ilich, for example. In order to find out the surname, i.e. the name of the family or the home, we must further ask and explain. My model in Galichnik, for example, had a full name Tvirtko Ivanov Ginovski.

We, the Czechs, may be particularly interested by the fact that very often the Macedonian surnames end in -ski. Therefore, they have Czech, and especially Polish endings, since this ending is not found among the rest of the Slaves. We didn't know that some years ago, when Rumelia was united with Bulgaria in 1885 and the name Dr. Stranski appeared, as that of chief executor of the coup, we thought at first that he must be one of the numerous Czechs, who were working there. The ending -ski is predominant among the Macedonians, just as -ich is among the Serbs and -ov and -ev among the Bulgarians and the Russians. And what seems odder, it is used among Slavs who are not neighbours, but on the contrary, are far apart, as the Macedonians

![]()

170

are from us and the Poles.

In Macedonia, of course, the Bulgarian endings -ov and -ev are also met fairly often, since the language of the Slavs there is closest to the Bulgarian, and up to the war they had considered themselves as a part of the Bulgarian people. Many of them had written their names Ivanov, Damianov, etc. This had been possible during Turkish times, but not now, in Serbia and Greek Macedonia. Everyone in Serbian Macedonia has been given an -ich at the end of his name by the authorities. Only the emigrants, who still can't return to their homes, have preserved their original names.

It is true that a hundred years ago the Serbian authorities had done the same thing, since the people had used only their given names at the time, and they had had to introduce some order. Anyone who had not had a surname at that time, had been asked "Who are you"? He had given either his father's name or his father's profession, and according to either of them had been written down as Pavlovich, Jovanovich, Kovachevich, or Popovich. Except that, all that .had been done with an administrative purpose, while now the authorities are changing even the surnames of the Albanians, and it is done with quite a different purpose - in order to give an outward Serbian appearance to Macedonia.

But let us leave politics aside and pay attention only to the fact that the paternal spirit is predominant there, according to which everything is the father's, including the wife and the children, as the system of names indicates. Otherwise, the people use only their given names, as it had once been in our country, during the time of Hus. He had lived only as Jan, while the surname Hus had appeared much later.

This was something that I might never had thought of, if a Macedonian peasant had not asked me once, "Do you have a king"?

"No", I had answered, "We have a republic and therefore a president".

"Why? Why not a king? Is it better that way?"

I hadn't known what to answer. The "why" had surprised me. All at once I had had to compare Macedonian conditions with ours! The man had really confused me. But in my confusion, something suddenly had flashed through my mind. To my surprise, I had felt that nothing else was possible. I had answered the peasant perfunctorily, but had tried even harder to answer myself. I had imagined that our

![]()

171

present president was a king. An objection had immediately sprung up — could we ever call him "King Masarik"? It was out of the question. We could call him by his given name, though. King Tomash seemed all right. Only the present title was suitable for a surname. A surname denotes present times, the opposite of patriarchal times. Times have their signs, which taken alone seem insignificant, but in reality are like buds. Even though they are quite small, they are a result of deep reasons. Such is development. May be for good, and may be for bad, but it never goes backwards. Patriarchal times have had their beauty. But in our country they have already passed. They will pass down there, as well. Our next president may be called Vomachka or Vokourka. And why not? But neither of them could be a king. Nor could any Novak ever be Caesar Novak. So may be the presidency awaits one of them. Who knows?

When, upon our arrival in Macedonia, my son had announced that all our turpentine had been spilt, I had been very angry at first, but I

Novo Selo, near Stip

![]()

172

had smiled when we had been able to buy some. The merchant, who had sold it to us, had said proudly, when he had heard where we come from: "And we, here, are descendants of Alexander the Great".

He might have been a disguised Greek, but to a certain extent he had been correct. It wad doubtful that the ancient Macedonians had been a Greek tribe (since Thucydides calls them semi-barbaric) but the dynasty of the Argeades, from which Alexander had descended, was Greek, at least from the cultural point of view.

So for truth's sake, if the above mentioned had not been, as far as time and greatness are concerned, a conqueror of the world, I doubt that anyone, except historians, would have had any idea of Macedonia. By the year 148, the Romans had erased it from the face of the earth, and as a state it has never existed since. But for Alexander, who died in 324 B.C., 33 years had been enough to engrave the name of his fatherland forever in mankind's memory, thanks to his political and military genius, his courage, and his numerous physical and spiritual advantages. He had been a student of Aristotle. He started building his glory from his childhood years, and his father, Philip II, a famous statesman, had once allegedly exclaimed with enthusiasm, "You, son, must find yourself a larger empire. My kingdom is too small for you!" He had said it as a "prophet, quite modestly.

More than 2000 years have passed since then, but the name Macedonia has been preserved in the memory of all mankind. Its territory is not large (approximately 60,000 sq. kilometers and with a population of 2.5 million and it has never since formed any political, or even administrative whole. During the Turkish domination, it had been divided in separate parts and had been attached to three Vilayets (provinces) — Salonica, Bitolja, and Kosovo, and the Istanbul newspapers had refrained from even mentioning the name. But the ban had been useless. The name could not have been erased from human thought or human language at all.

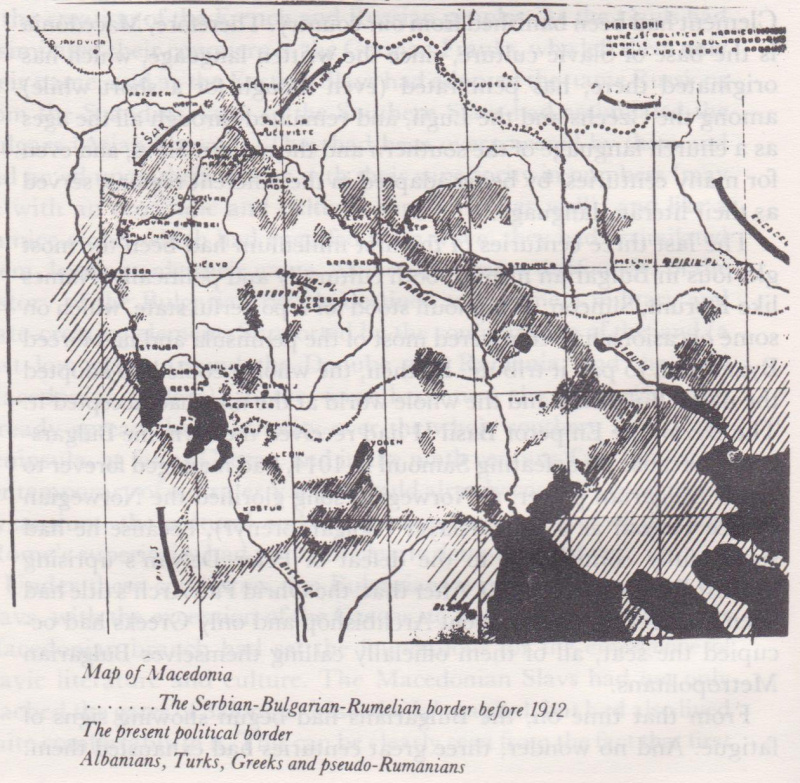

The configuration of the terrain, united its great diversity and contributed for the intransigence of the concept. It consisted of the valleys of the three major tributaries of the Aegean — Vardar, Struma, and Mesta, and had natural sea and mountain borders. To the east the Rhodopes and Rila were to the north Karadag, also called the Skoplje Cherna Gora, with the Shar mountain, to west the Albanian mountains and the Greek Pindus and Olympus.

From the ethnographical point of view, Macedonia is a continuous

![]()

173

Slavic territory, pierced by small islands of other national groups, of which the major ones are: Turks (500,000), Greeks (200,000), Albanians (100,000), Wallachs (60,000), Spanish Jews (70,000), and gypsies (50,000) [*]. The majority of the local Slavs, with the exception of an insignificant Serbian colony, have always been considered as a branch of the Bulgarian people.

This mosaic is a diagram of history.

In prehistoric times, the Thracians had lived in the eastern part of the Balkan peninsula and the Illyrians in the western. They had been divided by the diagonal line passing from Timok to Ohrid approximately. (Later, it had become the approximate border between the Serbian and Bulgarian tribes). The Wallachs, who have remained here and there, are a memory of the first inhabitants (they are probably Romanised Thracians). They are unevenly scattered in small regions. The Albanians live in the western part, in a compact group. They have penetrated the peninsula from the sea. The southern sea coast, with the Peloponnesus peninsula and the islands, had originally been the motherland of the blessed Hellenes. Their spiritual progress had been facilitated not only by the favourable climate and the possibilities open for shipping, but also by the contacts with the ancient Asian cultures. In such a way, this part of the Mediterranean had not only reached the highest point of cultural development during their age, but together with their early Roman subsidiary, had managed to erect the sound foundations of the whole later European culture including the present.

The northern peoples, towards the end of antiquity, had been attracted to the south, to the warm seas, and mainly to the cultural center which had existed there. The Western European peoples had turned towards the two peninsulas — the Italian and the Balkan, while the Eastern European peoples only towards the Balkan peninsula. (The crusades, even though they had had the same exterior and direct cause, had been nothing else, but a spontaneous response to the same aspirations towards the charming Southeast, whose smouldering spark had been inflamed by religious passions).

In the Balkan peninsula, the Slavs had come in small groups, as colonizers or mercenaries, reaching as far as Greece and Asia Minor.

*. The data is from before the war. All thefigures are approximate and are calculated according to the number of houses and households. Author's note.

![]()

174

The oldest record, a Slavic inscription with Greek characters, has reached us through Byzantium.

A great movement took place in the sixth century. The Slavs had come, as other peoples, holding weapons in their hands. Even now, the peoples cannot think of a more convincing reason for making such mass "visits". And if the remains of devastated long ago cities are now carefully unearthed and preserved in Skoplje, Gradsko, and Macedonia, it is nothing but a manifestation of some remorse for the sins, which our Slavs (together with the other peoples) have committed there.

The ancestors of the present South Slavs were the Slavs, who in the seventh century swept over the deserted Peloponnesus and had an independent state, and those, who in the thirteenth century had risen as a whole against the Frank feudal lords. The eastern and southern parts of the Balkan peninsula had had an interesting fate, reminding of the creation of the French and Russian peoples. As the Gauls had assimilated their conquerors, the German Franks, who left them only their name, and as the Eastern Slavs had adopted the lame Russians from the Scandinavians, so the Southern Slavs had assimilated the Bulgars (Asian Tartars). They had been overpowered by them and had acted upon their victors with their superiority in numbers (may be with an economic and cultural superiority, as well), and like a pumice stone, which had engulfed a sea wave, they had assimilated them, leaving only their name. Asparouh became the founder of the history of the Bulgarian people destined to become a military and state-creating element. Supported by the configuration of the land (a vast low plane around the Danube and Rumania, and the wide Macedonian valleys), in the seventh century the Bulgarians had already spread their authority over the whole southern part of the peninsula, as far as Greece, and in the ninth century Tsar Simeon, a contemporary of our ruler Vaclav, could already consider conquering Byzantium, the cultural and Christian-religious center of that age (Rome's superiority had not been clearly demonstrated yet.

Under these conditions, the Bulgarians were the first among the Slavs, with the exception of the Czechs, to adopt Christianity. Their Macedonian branch had set the foundations for the emergence of Slavic literature and culture. The Macedonian Slavs had not only reached the gates of Salonica, Macedonia's capital, but had also lived quite comfortably in it. This can be clearly seen from the fact that first

![]()

175

Slavic alphabet had been created there, and that the first, Slavic alphabet had been created there, and that the first, Slavic, religious books had been written there. And when the Prince of Moravia Rostislav, asked in 863 the Byzantine Emperor Michael III to send him Christian clergymen who knew the Slavic language, his wish could fulfilled immediately. Cyril and Methodius arrived in our country with the necessary books. It is clear that this work, through which the Slavic language had received not only an alphabet, but the possibility of expressing deeper religious-moral thoughts, should have been done much earlier. There exists a view among some scholars that the first Slavic alphabet, the Glagolitsa, had not been created by Cyril, but had existed much earlier.

The Bulgarian King Boris had been christened and had introduced Christianity in his country not long after the Salonica brothers had arrived in Moravia. Ohrid became the center of Slavic literature after Clement had been banished from our country. Therefore, Macedonia is the base of Slavic culture, since the written language, which has originated there, has penetrated (even though for a short while) among the Czechs and the Lugii, and remained through all the ages as a church language of the southern and the eastern Slavs, and even for many centuries, by being adapted in the different regions, served as their literary language.

The last three centuries of the first millennium had been the most glorious in Bulgarian history, both culturally and politically. Names like Kroum, Simeon, or Samouil stood for a powerful state, which on some occasions had conquered most of the peninsula and had forced Byzantium to pay it tribute. By then, the whole people had adopted the name Bulgarian and the whole world at the time had accepted it. The Byzantine Emperor Basil II had received the surname Bulgarslayer, because by defeating Samouil in 1014, had managed forever to crush Bulgarian power. A Norwegian song glorified the Norwegian Prince Harold as a Bulgarslayer (Bolgarabrenyr), because he had successfully contributed to the defeat of Peter Delyan's uprising against Byzantium in 1040. After that, the Ohrid Patriarch's title had been changed to Independent Archbishop and only Greeks had occupied the seat, all of them officially calling themselves Bulgarian Metropolitans.

From that time on, the Bulgarians had begun showing signs of fatigue. And no wonder, three great centuries had exhausted them.

![]()

176

Not only had Delyan's uprising failed, but the same fate had befallen the interesting initiative, encouraged by the Macedonians. In the eleventh century, they asked the Diocletian Serbian Prince Mihail to give them his son Bodin for a king, on the condition that he would organize a campaign against Byzantium. Bodin was actually elected as Bulgarian Tsar, in Prizren, in 1071, but his campaign had failed. Neither the attempts of the Assens, allied with the Serbian ruler Neman, nor the efforts of Tsar Kalovan, could give back Bulgaria its one-time superiority over Byzantium. So, gradually, the preserved Serbian people had started rising, in order to pick up from the Bulgarians the historical task — the struggle with Constantinople. Stephan's grandson, Ourosh II, had managed to reach as far as Polog, beyond the Shar mountain, for a short while, and his grandson Dragoutin as far as Serres and Stroumitsa. But it was his brother Miliutin who had been fated to capture all of Macedonia. In 1299 he

Map of Macedonia

....... The Serbian-Bulgarian-Rumelian border before 1912

The present political border

Albanians, Turks, Greeks and pseudo-Rumanians

![]()

177

had made Skoplje the Serbian capital. It had remained as such for 72 years, until the last ruler of the Neman family had died, i.e. until 1371, when Tsar Ourosh, Doushan's son, died by some interesting accident a few days after the Chernomen battle on Maritsa, in which Ouroshe's co-ruler King Vulkashin died. If there exists a battle which deserves to be called fateful, it is this one. "The Turkish domination over the Southern Slavs began from that moment", said their historian, our compatriot Constantine Jirecek.

Macedonia fell first and was longest, oppressed until the Balkan war of 1912, or to be precise, until the battle at Koumanovo, when the Serbs, fulfilling their major task, had occupied Macedonia after routing the Turks, while the Bulgarians, even though they had been victorious everywhere, had to go on fighting, since fresh Turkish forces from Asia were being sent against them all the time.

Macedonia, which had given 40,000 volunteers to assist the Bulgarians, had finally been liberated from Turkish yoke!

But how?

The glorious moment forces upon us a comparison with the conditions that had existed a thousand years ago, when Macedonia had been the first to spread enlightenment and legal freedom among all Slavdom, on the conditions, under which it had existed during those 1000 years. While Serbia [*] had already been free for a whole century and had gradually achieved political independence and had strengthened all the time, Macedonia had been bound by Turkish chains.

Where had the difference come from?

The situation had turned around. The Northwestern Balkan Slavs had become the ones closest to the centers of enlightenment, which had moved towards the European west, while Macedonia, and together with it the whole Bulgarian people, had become the one farthest away from them. When in 1826 P.J. Shafardjik published "Geschichte der Slavichen Sprache und Literatur", he had mentioned only the literature of "Slavic Serbs of Greek faith", in which he had included the literature of 600,000 Bulgarians as well. For the outside world, the Bulgarians made themselves known much later, and the reason had been the fact that their fate had been much more difficult than that of the Serbs. The Serbs had suffered from the Turks only politically and economically, but had had a National Church and a National School. Besides that, the Bulgarians had also been

*. In 1830 it had received autonomy. Author's note.

![]()

178

oppressed by the Greek clergy. A Bulgarian school, such as the one that existed in Veles, in 1750, was a major exception. That was why the first struggles of the Macedonians had been against the Greeks.

It is interesting, that under such difficult conditions, Macedonia was the one that started to express its Bulgarian national spirit first, sending out its apostolic message after long centuries of silence.

In 1762, in Macedonia, in the Serbian monastery Hilendar on Mount Athos, Paissiy Hilendarski finished his history of the Bulgarian people, which may have little historical value, but for the people had been invaluable. It had been the call of one rising from his sleep. Through it, new Bulgaria had been revived. The book had served as a seed. In the beginning of the nineteenth century, a number of Macedonians proved to be good writers, printers, publishers, teachers, and later on politicians, rebellion leaders, and soldiers.

In 1814, in Buda, Hungary, the first book, by the Macedonian Hadji Yakim, was published. It was followed by other works by the same author, published with contributions from many towns and villages, of which, for example, Novo Selo, near Stip (a romantic spot near Krali Marko's castle), had collected 500 groshes for their publication.

Dascal Kamche from Ohrid had founded the first printing press in Salonica, while books had been printed in Istanbul, as well. Neofit Rilski had become the founder of Bulgarian pedagogy and had transferred his activity from Macedonia to Bulgaria. In Stip, where Bulgarian books had been written in the Middle Ages, by 1830 there had already been a school with 150 pupils, In the fifties, the Istanbul Bulgarians had sent the Hungarian emigrant, the Serb Georgi Miletich (from the family of the famous Hungarian-Serbian revolutionary Svetozar Miletich) there. He had quickly understood that the children's studies could not be conducted in the Serbian language, but only in the Bulgarian. In 1860, his wife founded a Bulgarian girl's school.

With the development of literature and schools among the Macedonians, it had become clear that they must rid the church of Greeks. In 1833 they drove the Greek priests our of the churches, and made demands for Bulgarian clergymen, and above all for a Bulgarian Metropolitan. Their demands were made in vain, but as a result of their struggle, four citizens had contributed 30,000 groshes for the foundation of a Bulgarian school. Koukoush, which is now in Greece,

![]()

179

and threatened in 1859 that it would adopt Catholicism (and had really carried out its threat afterwards) if it was not given a Bulgarian Metropolitan. In 1860, in Stip, the Greek singers were driven out of the church during the Sunday service. Dimitar Miladinov had struggled heroically in Ohrid, and together with his brother had suffered a martyr's death in Istanbul.

When finally, in 1870, Bulgaria acquired a national church, through the establishment of the Exarchate, there had been 178 schools in Macedonia, built by the people. Their number had soon risen to more than 600. Forces for a political and revolutionary activity had also been released. It had started as far back as the sixties, by the Bulgarians from Danubian Bulgaria and those abroad. Names like those of Illiya Markov from Behr, Georgi Izmirliev, nicknamed the Macedonian, etc. had appeared.

The Macedonian Revival had exerted an influence abroad, especially among Slavs. Shafardjik had corrected his views. The Serb Vuk Karadjich had become interested by Bulgarian songs in Macedonia. Shafardjik's map of 1842 (and other ethnographic maps following it) showed the Bulgarian people and its territorial distribution. The Belgrade scholarship holder, the Bosnia Serb S. Verkovich, had given most of his life in research work in Macedonia, and had become an apostle of its Bulgarian national spirit. In 1860, he gave his "Folk Songs of the Bulgarian Macedonians" as a gift to the Serbian Princess Julia Obretenovich. Towards the happy feeling of kinship, which had awoken in both Bulgarians and Serbs, the consciousness that a common enemy existed for both had been added. The idyllic times of Slavic unity had fully corresponded to Kolarov's ideals for a Slavic mutuality and they had reached their peak with actions, which reminded one of the offer made to Prince Bodin in 1071. The Macedonians, in agreement with the rest of the Bulgarian politicians, had offered Mikhail Obretenovich a confederation between the two peoples.

After the Herzegovina revolt of 1875, and later the Bulgarian and Macedonian uprising of 1876, The Russo-Turkish war of 1877 broke out and ended with victorious San-Stefano peace treaty. One of its articles speaks of liberated Bulgaria together with Macedonia. Bulgarian Macedonia was jubilant. It had achieved its goal.

During the Berlin Peace Congress that article had been fully re vised. And dreadfully, at that! The Bulgarian people were torn in

![]()

180

parts. The South Morava area, which until then was known as Bulgarian Morava in its eastern part with Nish, Pirot, Vranya, Zaichar, and Leskovets, was given to Serbia, while a Bulgarian principality was created only in the northern regions. The autonomous Rumelia was formed in the southern regions. Macedonia had remained under the Sultan. It had been promised "reforms".

The uprisings in Razlog, Prillep and Ohrid followed, and since then Macedonia had turned into a constant battlefield. The most educated Macedonians had become leaders of the bands.

The situation had worsened still. Thanks to the Salonica railway line, coming from Belgrade, a political interest towards Macedonia was aroused in Belgrade. After the Union of East Rumelia with the Bulgarian Principality in 1885, King Milan led the Serbian Army against Bulgaria, but the Serbs were routed at Slivnitsa. In such a way, Macedonia had acquired a new enemy — its former ally.

Since the promised reforms had not been carried out, while the economic difficulties of the Macedonians had increased (they had been oppressed by the landowners, the majority of which had been Turks, and by their servants, especially by the notorious Albanian field-keepers), the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization was founded in 1893. Its goal was the establishment of autonomy. A revolutionary wave had risen. At first, it had been aimed against the Turks, but when Serbian and Greek bands had invaded Macedonia, it had had to fight against three enemies too. From 1898 until 1902, 132 battles were waged, in which more than 500 Macedonians were killed.

Clouds began gathering over Macedonia. The only folk songs from that time were of bullets (lead). The songs told of Turkish, Greek, and Serbian bullets. A typical example of those times is the short song: Three guns were fired, three heroes, Oh, God, have fallen. Three heroes have fallen, three mothers are crying, Oh, God, crying.

A friend of mine, a Czech, who owing to his profession of a clerk knew Macedonia well, once told me, "There is not a more miserable mother in the world than the Macedonian mother. She lives in constant fear for the lives of her children".

This desperate land had tried to focus some attention on itself with brave deeds and assassinations. Finally, in 1903, it rose in the famous

![]()

181

Illinden uprising (St. Illiya's day, July 20). It was the largest armed struggle ever carried out by a Slavic population (without a state of its own) against the Turks. 26,000 Macedonians fought against a Turkish army of 350,000. The former lost 1000 people and the latter 5000. The Turkish artillery destroyed a number of villages. 12,000 houses were destroyed, 5000 people were slayed. The struggle, which was led chiefly in the Bitolja area, continued for three months and achieved poor results. In a meeting in Mursteg, the Three Monarchs decided to create an international gendarmerie at Turkey's expense.

The participants in this commission, the Frenchman La Mouche and the Austrian A. Rapport, made interesting descriptions of their four year long work in their books "Quinze and d'histoire balcanique" and "An pays des martyres". The work of the commission had begun with the settling of the salaries and had continued with the creation of barracks. The commission would have been dissolved at one point because of the issue of uniforms. The Turks had not wanted to drop their fezzes. But just then, a much more serious event had taken place — The Young Turks Revolution.

Its seed had been planted on the shores of Lake Prespa, in the Ressen valley (therefore, in the same place in which the IMRO had been founded), by Nyazi Bey, who was born in Ressen. It ended with the reforms and all the rest. History began sliding down like an avalanche. The Italians invaded Tunisia, while the Balkan states allied for a final showdown with Turkey. The Balkan War, which was nothing but an overture towards the World War, began.

The end is well known.

In the Balkan War, after the complete victory over Turkey, the disagreements between Bulgaria and Serbia led to the uneven war between exhausted Bulgaria and its former allies, which Rumania had joined in the meantime [*]. Bulgaria was defeated. And it was again among the defeated after the World War.

The reason for the Serbian-Bulgarian discord was Macedonia. The Bulgarian claims over Macedonia, with the exception of the so called "contested zone" (which bordered on Old Serbia) were recognized by a treaty before the war. If the war ended victoriously, the Russian

*. Rumania's participation had been such that the Slavists Louis Leger and his follower La Mouche publicly renounced their Rumanian friends, until it would not correct its "Heroic deed". Author's note.

![]()

182

Tsar would be the one to decide whom the "contested zone" should be given to.

But the turn of events was such, that unfortunately, the Tsar's decision became unnecessary. The developments, from a Slavic point of view, were very painful. Bulgaria, which in the war had twice as heavy task, since only she was the one exposed to the constantly arriving from Asia Minor Turkish reinforcements, was forced, because of disagreements over Macedonia, after a six month exhausting war with Turkey," to oppose her former allies, joined by Rumania militarily and by Turkey diplomatically. The uneven struggle ended tragically from a Slavic point of view, with a loss of Bulgarian territories to Rumania, Greece and Turkey.

Macedonia received just the opposite of what it had dreamed and aspired for. Only an insignificant part was allotted to Bulgaria. The largest (but not the most ferule) part was taken by Serbia and, united with Old Serbia, remained under the name South Serbia. Greece, with the smallest number of military casualties, received the largest share, with the most fertile, southern Macedonian regions. It increased its population by more than 2 million, of which 300,000 were Macedonian Bulgarians, or "Slavic speaking", as Venizelos called them. From that moment on, not a single Bulgarian school remained either in the Greek, or in the Serbian parts of Macedonia. If in the Greek part, even though rarely, some books have been published in the Slavic dialect with Greek characters, in the Serbian part, where more than 600,000 Bulgarians had remained, the Bulgarian nationality not recognized at all. No Bulgarian books are permitted there. According to information from our Slavic review (1931, book 3, p. 226), the endings -ov and -ev of the Bulgarian names, have been replaced by -iades (e.g. Evtimov — Evtimiades) in the Greek part, and an -ich has been added to them (e.g. Popov-Popovich) in South Serbia. The phenomenon reminds one of the Lugii Serbs. While under German domination, they had been forced to adopt German surnames. But there are two major differences — they can use their own surname as well (in such a way everyone has two surnames), and secondly, everyone is free to consider himself a Serb, and that does not create obstacles for him even in his career as a civil servant.

So Turkey recognized the Macedonians as Bulgarians, Greece recognizes them as "Slavic speaking" at least, but Serbia denied them the right and forbidden them to call themselves Bulgarians. Under

![]()

183

such conditions, no wonder that many of them emigrate to Bulgaria. If some impartial onlooker ever reproaches them that in such a way they are hurting their own people, we must reject his reproach, since he is obviously unacquainted with the internal conditions.

Such ignorance is excusable in our country, since, for some unknown reason, nothing is written of the conditions there (often it is even prohibited).

By concealing our interests towards Slavdom, we readily vow that we have an impartial, unegoistical, and moral attitude towards all Slavic branches, and we always speak about the settlement of their issues according to the principle of absolute equity. It is desirable, but in reality it is not done.

If we begin writing of this error, which increases each day, it would mean that we must write quite a large book. So I am concluding by referring to Joseph Holecek's book "In Yugoslavia of 1924", in which he describes how he had been received by the present Yugoslav King. Even though Holecek knew very well that the Bulgarian nationality had been officially prohibited in South Serbia, he had spoken of the Macedonians as the western part of the divided Bulgarian people (p. 67). And the King had not protested!