VI. AMONG NATURE

The Foal 133

The Buffalo 135

"We are savages", we were constantly assured by the local people. The townsman, shrugging his shoulders, would say the same thing, "We are a savage people". And because, if something happens here, it appears in all European newspapers (while our numerous cases are always termed as local), poor Macedonia has been glorified as a "dangerous zone" more than it deserves. At least I, myself, seek futilely both in my notes and in my memory a threat on my life, whatever it may be, I even find things, which absolutely contradict the legends, and I will describe one such occurrence now, at the risk of being laughed at, because of its insignificance.

My recollection is of a horse. The ordinary phenomenon had probably interested me, because fate had not wished me to be in contact with animals and to become acquainted with their inner selves, even though I have lacked neither the will, nor the feelings to do it. As a boy, I had started reading Brem, but soon the circumstances had turned my attention and activities in another direction and I had grown up with the views, of literature and the newspapers, that the animal was just a likeness of human degeneration. I had held that view for quite a long time, but once I visited a friend who had a dog was very surprised by the following incident: someone had started lamenting and crying jokingly, hiding his face in his hands, and the dear dog would have gone mad with sympathy and grief. It had fawned upon the wretched fellow, had whined sadly, and with its front paws had tried to pull his hands from his face, as if to console him. It had no need to read the Holy Scripture's words: "Weep together with the weeping". Little by little I was unable to read words like "swine", or "animal", or especially the diligently created, modern word "brute", and not feel them as an undeserved insult towards the innocent creatures, which possessed a great will to live, but the deliberate nurturing of passions, vice, and malice, and especially the invention of moral, ideological, or philosophical mottos, which would serve malevolence, just as the fig-leaf serves as a pretence to shyness,

![]()

134

were unknown to them. Even though the virtuous life of the animals, with which they were superior to man, lacked a subjective nature, and therefore a moral one, and had only a practical value and an objective significance, the use of words as "swine" (opposed to "humaneness") reminded me of the cry of the thief: "Catch the thief!"

These thoughts persistently imposed themselves upon me whenever I remembered that trip, accompanied by Nichola, through the labyrinths of basalt rocks, watching the beautiful horizons of the Prillep area.

Nichola had found the horses for the journey from Dabnitsa to the Treskavets monastery and was accompanying us in order to return the horses back. On the way, he acquainted us with his meager life, in which the new times had pressed him. The war had brought numerous difficulties and sufferings to the area, and not benefit, as to Middle Europe. After the war, some past difficulties had again awakened. Trade had received a new purpose and different centers. And the ordinary man, if fate had not placed him in a convenient spot, began to suffer. Nichola complained of the large taxes, sounding me out to see if I wasn't in a position to help. He described the great tobacco failure, which in 1925 had befallen the area and had brought great losses to the peasants. In such a way, he was placing me in an uncomfortable position, since little by little I had to dispel the hopes, which he had wrongly placed on me.

I started looking to the left, at the wide, rocky valley, where between the grey rocks and stones, bared in the course of time, there was still enough soil for a nice small meadow and a few beautiful trees, fan-shaped willows and tall poplars. The group was so picturesque that it highly interested me. In the middle a spring gushed forth through the rocks. It had managed to make its way between the stones. Next to it was a white horse, of the type to which only Cermark [*] could add a beautiful Macedonian woman.

The white horse saw us. It raised its head and turned its neck in our direction. Seconds later, it started neighing.

"It's a nice pasture," I said to myself. "It has grass, water, and coolness". I started looking for the herdsman who was taking care of the horse, but saw no one.

Nichola also looked at the horse, and interrupting his accounts and complaints, said, smiling with satisfaction, "That's my horse".

*. A Czech, nineteenth cen. artist. Translator's note.

![]()

135

"Your's? What's it doing there?"

"It's grazing."

"Alone?"

"Alone."

"Why?"

"The harvest has already passed and everyone is necessary at home, so I brought it out here. It will stay here until the first snow and will then come home."

"Alone?"

"Alone."

"And what if someone steals it?"

"Why would he do that?"

"Really", I thought, "this is a wild place!"

I looked at the horse, which hadn't stopped neighing after us. I now understood it. It was greeting its master, happily and eagerly. Even though it had only seen hard work from him and had not been fed well enough, it would obediently return from its "summer camp", as a conscientious clerk from his vacation.

This horse kept looking at us and neighing. But we went on without a word or a gesture. May be Nichola, just as myself, felt ashamed at our human helplessness to answer the affectionate greeting of the horse suitably.

We finally moved out of its view. We moved out owing it something, since man was not made in such a way that he could react to the "animal". He could not respond to the attention, with which the mute animal honoured him.

I saw it for the first time in Southern Bulgaria, in Rumelia. A whole herd, looking like a dark cloud, was resting on the shining Maritsa, which had spread out in the Plovdiv lowlands. Its soft bed had attracted the four-legged gentlemen, using to their hearts content its slime, which healed rheumatism. "The patients" weren't, of course, real patients, but were simply taking wise precautions. Mankind will be happy one day, when it can limit itself to such treatment only.

Since then, I have always connected their oval and somewhat flattened out shape with the image of the elongated horizons and the

![]()

136

southern, boggy lowlands. The artistic thought, expressed through their formation and style, was their yearning to merge with the horizon. In detail, they could be distinguished by their wide muffles, their set apart horns, their comfortable postures, and their wide steps.

Seeing a buffalo helps us orientate ourselves geographically. It means that we are somewhere in the southern half of the Balkan peninsula, since the buffalo wades only in the rivers, which flow towards the Aegean [*]. It cannot survive in our country, and it will not look so beautiful either. Its dark coat needs the hot sun, which makes its blackness gradate into green and violet gleams, with which the festive coat of the beast acquires the tenderness and charm of velvet.

This tenderness — appreciated and acknowledged by no one — penetrates through the whole being with such a force that even its meat has the taste of musk, which (figuratively said) harms it in many's eyes. In this respect, the buffalo, according to us, has gone a bit too far.

I believe, of course, that the human stomach's view is very narrow-minded and I do not share it. I am attracted much more by the expression and the outward appearance of the beast. Without exception, the buffaloes are serious and natural. It seems that they now what an important role they have played here, until the development of roads and railway lines. If the camel and the donkey had been the most important beasts of burden, on whose backs endless caravans of goods had traveled, the buffalo had been the most important hauling beast, since on the primitive roads it had been the only suitable animal to pull carts with large quantities of goods to faraway places. The oxen had been used on short distances, usually to neighbouring villages, while the long distances had been covered only by the buffaloes.

But the railroad and the car had displaced the buffalo. It awaited its fate calmly, preserving its dignity as an old pensioner. Whether it was rolling in the river or in the puddles, or grazing with majestic indifference, or slowly, as if at a funeral, was pulling the overloaded cart, it was always augustly calm, thus reminding of its Eastern origin. The Oriental law commands: "Be troubled by nothing and always preserve the expression of Ben Akiba, who was surprised by nothing". From this point of view, the buffalo could be placed on the same footing as the local "effendies," "imams," and "hadjis," and

*. With the exception of Old Serbia. Author's note.

![]()

137

could divide the glory of outward dignity with them.

In order to achieve such an expression more easily, nature had endowed it with a number of qualities.

I have already mentioned the coat, which resembled the broadcloth of our ritual costumes. If its skin was not .covered either with flakes of dried up mud or with fresh mud, the buffalo seemed to be wearing a long frock-coat or a "kaiserokk." The counselors at the Austrian court had worn them when they had made their reports to the ministers, and they weren't quite unlike the buffaloes, since they possessed the same gait-ceremonial and somewhat wobbly.

I must say that if the buffaloes didn't have the habit of rolling around in the marshes, I would have pronounced them as much bigger dandies than our cattle. Their horns, for example, were not pointed out from their foreheads aimlessly, like those of our oxen or exhausted little cows. With a moderate elegance, the wave of their horns was divided in two, just over their foreheads, and they were curved in the form of an S.

The decorative ears resembled a hanging tire with heavy, black tassels, as those we are used to seeing only on the funeral covers of first-class funerals, for which, by the way, the buffaloes were much more appropriate than the wild horses, which always seemed to be stomping restlessly with their hoofs, or impatiently jerking the reins.

Some of the buffaloes' other qualities, as the already mentioned horns, for example, could also help them perform such an honourable task — to accompany important or rich persons on their last journey.

Their white horns, sticking out on the dark background of their heads, had almost the same shape as the turned in, silver edges of the hats, worn in our country by those accompanying the coffin at a funeral.

Another thing that made the two of them look alike was the way they both walked self-confidently, with heads raised upwards. The people accompanying the coffin were not to be blamed for the proudness, which they seemed to manifest, of course. The reason was the very narrow band, which held their hats, and by raising their heads they could rest for a while.

The buffaloes were also far from showing any haughtiness, at least such was my opinion. At first, I had thought that the reason for the right angle between their muffles and their necks was the constant rolling about in the water. While in the water, they had to keep their

![]()

138

muffles raised, in order not to swallow any of it. There could be some truth in this, but I soon found another reason, much more significant and much more correct.

I made my discovery quite accidentally. The stiff collar of one of my new shirts had chafed the skin at the back of my neck and for a whole week I had to bend down or raise up my chin, in order to minimize the chafing. In such a way, I was considerably relieved. In this unenviable condition I once happened to walk beside a team of buffaloes, whose heads were fastened, as was always done here, in a double wooden yoke. The yoke consisted of two wooden squares through which the buffaloes' heads stuck out as- in a family portrait. This contraption, which could be of interest to western scholars from an archeologically-ethnographically-anthropological point of view, was' handed down from ancient times, but at the same time, the buffaloes were quite unhappy in it. It held them by a cervical vertebra so firmly, that instead of pulling the cart they pushed it. After some time a corn was formed on that spot and the friction from the yoke must have hurt much more than my collar. At that moment, I suddenly understood why the buffaloes folded their bodies and raised their muffles. In both cases, the cause and the effect were the same. Since

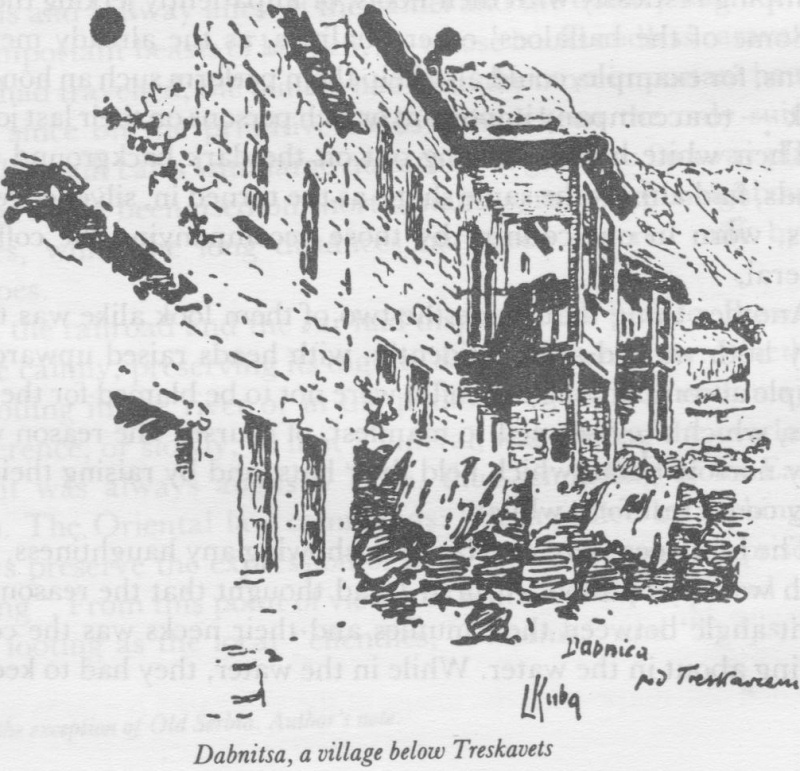

Dabnitsa, a village below Treskavets

![]()

139

then, I have looked on them not only with greater understanding, but with sympathy, as well.

After some time, respect was added to those feelings, since I found traces of considerable intelligence in them. Once during the midday heat, which had made me dull, I had difficulty in crawling through the red-hot streets, when it suddenly dawned upon me that I could walk pressed close to the walls. Their shadows were narrow and could cover only half of me, but still it helped. I moved on panting, with a bowed down head, when I almost collided with a buffalo. Its wide belly was pressed so hard against the wall that it seemed about to break, but just as me, the buffalo had wanted to escape the heat. We went on against each other and couldn't agree who should move aside. Since at that moment we had shown the same degree of intelligence, the question was reduced to the following — I had to defeat him with my moral superiority.

Another time, we were returning from a half-day picnic and a buffalo herd was walking alone with us. They were sate, while we were hungry, since they had been grazing all morning, while we had eaten nothing. In the town, they started disappearing one by one. Certain buffaloes stepped aside from the street and stopped in front of the buildings, raising their muffles as if checking the addresses. After that they started mooing, and when it didn't help, they pushed the door lightly with their horns and waited patiently, until someone opened it.

In such cases, which may not appear so interesting, I was amazed chiefly by the fact that the buffaloes knew the numbers so well. A reader, who has seen a dog or a horse count, may look upon the fact with indifference. He should know, though, that the beast in this case had a far more difficult task, since for some unknown reason the addresses of the houses were nailed upside down. And while zero upside down was still a zero, what could the poor animal think when it saw a six or a nine, since each number was the opposite of the other?! But the buffalo, as it had been established, was never wrong: it was absolutely impossible for it to err.

I don't intend to defend the idea that the buffalo is intellectually superior to man. I found proof for the fact when we reached the inn where we stopped. Unconsciously, I turned around to look at the rest of the herd and to see if our action would arouse their interest. There was no such thing! Therefore, they lacked the ability to admit mental

![]()

140

maturity in others. It was an indisputable proof of their mental inferiority.

The first were above us and the second beneath us — that was how we approached the Treskavets monastery.

The peak seemed high as our Snezhka and the granite rocks betrayed their volcanic origin from far away, with their ferocity. They were in full contrast with the neighbouring mountains, composed of graphite and limestone, which watched the rocks and stones, resembling a petrified, satanic wedding, with their calm, simple fullnes. The rocks looked lordly and sublime, and alien and dreaded, may be because they were higher, or may be because the wide Prillep valley allowed them enough privacy from ill-bred, common people.

But the mountain attracted us. Its first terrace was in its southern part. It was indented by the ruins of Krali Marko's castle and looked like the smooth jaw of a skull with carved out molars. The old monastery, our goal, was on the second terrace, while Zlatovrukh's shield, with the golden apple, towered over the third one, hiding many legends and beautiful scenes. To its northwest was Babouna, where the last remnants of the Bogomils and the Patarens (Medieval religious visionaries, Predecessors of the Albigenses and the Waldenses) had led their final, desperate struggles and from where they had acquired their name Babouni.

The road was only for walking or riding. It looked as if it had been the site of a Cyclopes' battle. The scattered rocks lay in such unsteady positions that every time our animals touched them with their hind parts we were afraid they might roll towards the precipice. I almost wrote this story with a bombastic title: "Between the Sky and the Earth!" But in my notes I noticed the lines: " . . .seven eagles are constantly accompanying us as an escort of pilots. May be they will serve as our suite all the way to the monastery . . ." So I changed the title, guided by a speculation — a result of later reasoning — that for the honour we had to thank only our awkward riding, which had probably given hope to the birds of prey that in a short while they would be able to pick at us and eat us in some ravine. We were amidst the mountain range, riding in an undignified intimacy with those features that are believed to be an antipode of human intellect and

![]()

141

wit. But the circumstances did not permit us to dwell on questions of prestige. We were content that the donkeys were carrying us well. I told myself: "Modesty ennobles", and I proudly sat up on the ridiculed animal.

I couldn't even imagine that a day later, almost in these same places, I would be punished for evaluating the relationship between myself and the donkey wrongly and unjustly. I am ashamed to write of it, but I am doing it as a repentance.

Since we were received very warmly in the monastery, to which we had thought of making just an ordinary outing, and since I noticed that not only could I collect songs, but that I could make some drawings as well, on the next day I walked back to Prillep for my drawing equipment. Once there, I had difficulty in finding transportation, but I finally did and set off toward Dabnitsa, below Zlatovrukh, where the considerate priest had offered me not only lodging and a meal the day before, but had promised to give me a guide and a donkey on my way back, as well. I had planned to be in the monastery before sunset, with the donkey and the guide.

But I was disappointed. This time the priest just shrugged his shoulders and said, "Tomorrow is a market day in Prillep and I can spare no one".

It was a great shock to me. It was already five o'clock, in the second half of August, and I needed at least two hours to reach the monastery by myself.

"If you want to go alone, I will lend you my donkey and a boy from the monastery will return it tomorrow", said the considerate man.

"Alone? But how am I going to find it?"

"Don't worry, the donkey will."

And what about my things?" (I had canvases, frames, small boxes, an easel, etc.).

We will load them on the donkey."

There was a strong wind blowing in the mountains that day. It was quite violent and seemed to promise to knock me and the donkey down, if it could reach the spread out canvases. But I would have felt ashamed if I had declined the proposal, and since every minute was precious, we quickly loaded my things and tied them up. After that, I managed to mount the donkey with the common efforts of the monks. Then, they inserted my feet in rope stirrups, stuck the reins in my left hand and a staff, as a symbol of my ruler's power, in my right one. But

![]()

142

only as a symbol. In reality, they took me, or rather the donkey, as far as the mountain slope, so that the wise animal (as a proof that it was wise) could take me to the monastery and come back.

The picture lacked only a Don Quixote in front of me, in order to be complete. I set off, but was actually sent off. When all was over, it didn't seem so bad after all. As soon as it felt the path under its tender and at the same time strong legs, the intelligent animal started climbing quickly, with occasional snorts.

We traveled well, more or less. Only in those places, where the spring floods had erased the path and the smooth, steep stones made the donkey insecure, I sat breathless. In such cases I would start offering my advice, based only on human intelligence, of course, as to where the animal should step. But our opinions did not always coincide. It stepped where it wanted to, and with a snort, would suddenly make a small leap,- almost throwing me with the luggage up into the air.

The excellent animal, which by then I was worshipping in my soul, aroused only one doubt in me. I was afraid that it might tear up the canvasses, as it walked so near the rocks and the bushes.

But we reached the point from which the monastery could be seen, without any incident. It was at half-way and from there the road was level. The sun had already set and it was clear that we would not be able to reach the monastery before dark. But the wind had calmed down and did not threaten us any more, and I could contemplate the magnificent, golden, nocturnal sights on the horizon. Two huge rocks, whose fantastic shapes of fairy-tale frogs looked strangely alike, as a male and female mate, fascinated me most. I suddenly saw two small, wormlike creatures in the gorge between them. They turned out to be two young men, one of them being my son. They had gone out to look for me.

There was little hope that they would notice me and the grey donkey in the dusk, but I waved my hat anyway. I very much would have liked to meet the boys, and for a moment I thought that they had noticed me, but they soon disappeared. When a few minutes later I glimpsed my son, this time alone, and lost him again, all hope left me.

This did not spoil my good mood, though. I was certain that I would return safely, since only a quarter of an hour was left to the monastery. But suddenly, the donkey started turning to the right. We were close to the "frogs", which were already towering above us, as

![]()

143

huge castles, and I had remembered from the previous day that the road became steeper and curved a bit, but also diverged. The southern road led to Prillep. And if the donkey took that one? Why, it would prefer to walk downwards! And, after all, who had told it that it must go to the monastery? It continued turning towards Prillep and we left the monastery almost behind our backs! My attempts to make it turn right were futile. And the road had disappeared completely in the semi-darkness. I so much wanted to know if we were following the right direction, but I couldn't see the road at all, not only because of the darkness, but also because we had reached a large, stone platform.

I jumped off the donkey and tried to pull it by force towards the "frogs", next to which the road towards the monastery passed. Or was it possible that I was mistaken? I shouted and pulled the animal with all my strength, but the donkey wouldn't budge. The unequal struggle went on for quite a while and I finally had to sit down exhausted.

The donkey snorted happily, while I, aware of the ridiculous situation, had almost put up with the fact that I would have to spend the night under the open sky. But suddenly, I had a wonderful thought. What would happen if I tried to induce the donkey from behind? Even people were sometimes more reasonable to arguments coming from that direction, if, of course, they were convincing enough. I tried to win over the donkey with my fists, with my staff, and by pushing and shouting. And the stubborn animal finally gave in, slowly at first, but still we reached our road, which took us to the monastery's gates.

I was tired and sweating all over when I knocked. My throat felt as if it was in Sahra.

The doorman opened the gate and the smiling Brother Modest and my son greeted me. I immediately asked for some water, with a hoarse voice. For the first time in life, I knew what a dry throat meant.

I unloaded my things off my donkey almost to the monastery itself', I finished my complaint.

"I had to struggle with the donkey almost to the monastery itself', I finished my complaint.

"All that you have done has been unnecessary", Brother Modest said with a gentle smile. "You should have left the donkey alone and not interfered with it. It wouldn't have done anything wrong . . ."

![]()

144

"Only we, people, do", I murmured to myself.

"The donkey has really made a big turn at that place", went on Modest, "but it would never have set off for Prillep. It has enough sense not to".

My adventure amused us during supper. The donkey was the hero of the day.

I finally said, almost vexed, "All right, I know that we sometimes call a person a donkey, but why on earth is the donkey called so?"