35

PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER III.

Wards of the Outer March.

SUN, dust, grilling heat and a crowd of perspiring countryfolk; train-whistles, shouts, and the neighing of horses. We slung out of a stuffy train which had climbed laboriously for four hours to Radomir station - two huts at the end of the branch line. It was market-day at the village a couple of miles away, and the ground was paved with baskets and bundles, bouquets of chickens tied together by the legs, and man-traps of long-handled hoes. Boring through the odorous crowd - why will they wear sheep-skins in such heat? - we discovered in a maze of bullock-carts the crazy shandrydan bespoken the day before in Sofia, and sent on to meet us. In shape it resembled a Paris fiacre of great age and infirmity, its loose-jointed frame held together by knots of rope, and the aggregate of ailments possessed by the four sullen nags which drew it might have been lifted wholesale from a vet.'s list. These sorrow-stricken Galloways leaned against each other in a row with closed eyes, snatching a moment of repose before their thirty-mile flight. Our only excuse for hiring them was that all the others were worse.

![]()

35

On the box (so called) sat a swarthy ruffian who wore a drooping cigarette on his left ear and eyed us with disfavour. All being ready, he plucked from under him an awesome flail, and with a whoop that raised the birds, laid a succession of trip-hammer blows on the backs of the sleeping beauties. In one bound they were at full gallop, hurling themselves on three legs apiece through the crowd of waggons and wayfarers, with clashing bell-necklaces. Just as each of us had discovered something to hold on by we stopped suddenly in the village, where the Oof-bird, with the eye of an eagle swooping on its prey, dived into some mysterious purlieu in search of coins, leaving his travelling mates to sit and roast in the hard-seated conveyance.

Through the heat-shimmer of the sleepy street plodded a yoke of oxen with a high-piled waggon of hay. Round about were queer little woodwalled hovels with half-open fronts. A baker sat on a counter, under his wooden-flap awning, arranging flat brown loaves; opposite, a harness-maker pulled down an ox-yoke from his dangling stock-in-trade to haggle over with a fur-capped peasant. Suddenly a cavalry patrol turned the corner and jingled past at a trot in a cloud of choking dust.

"Snakes, man!" observed Skip, waking out of a doze. "I'd forgotten all about this old war. Wonder if those fellas know anything?" But we were powerless to ask, so dozed for twenty grilling minutes till the family-coach lurched

![]()

36

dangerously as the Oof-bird bounded in, disgust writ large upon his face. "Shah! " he growled, " I've been wasting my time." The two baked bodies whose time did not count made room, the triphammer descended again, and we were off for the frontier.

The surface of that road was calculated to smash an ordinary farm cart to splinters, but there was a sort of give-and-take about our miraculous rattletrap which allowed it to pass whole over the rocks and pits of which this important highway was constructed. It was continually climbing and descending steep hills, but on the scarce levels between we had time to look at a fine country. Sweeps of veldt-like sunburned land running back, bare and empty, to the foot-hills a couple of miles away. Gradually these closed in till we were rattling up a valley that might be Swaledale, only the oaks and beeches, thick on the hillsides, are about half the size of the Yorkshire trees. Below, among grey boulders, ran a stream that looked like trout, with good green turf along its sides. The hills opened out again, and heavy-laden plumtrees stood up over the big thistles and bramble bushes on the roadside banks. Blue-backed magpies searched the rye-stubbles; bright blue and orange moths danced above them. As we tramped through the dust of a stiff up-grade the little lizards darted across the baking rocks to hide in the cracks. Over all the fierce sun, which made climbing in English tweeds something of a labour.

The swarthy Jehu, who now bore by common

![]()

37

consent

the name of Antonio, showed a marked distaste for this hill-walking, answering

the loud commands to "Get down" by an active and engrossing pantomime representing

the process of a deadly combat, and the receipt by himself of a painful

wound in the right thigh. The Oof-bird's gestures promising ing the fliction

of an equally grave injury to the left limb, however, brought him to earth;

but, to do him justice, it was only when the rats bolted with the trap

that he forgot the limp and pursued them with the speed of a mountain hare.

He was really a wonderful whip, and his handling of those four cripples

on the awkward down-grades would have turned Joe Selby green with envy.

He would pause on the top as one hangs at the dead point of a swing - and

with the same sensation - then let go with the swoop of a vulture down

a twisting mountain road where we swayed between pulverization on the bare

rock on the one side, and a sheer drop to perdition on the other. In full

flight he would rip across six loose gaping planks over some hideous abyss,

whilst an instant vision of one of those rattling feet put wrong sent iced

electricity down the spine. Far sooner would I loop the loop on a hand-barrow

than sit again behind that demon driver, gripping a rotten strap as my

last chance of life. When we arrived with a bump on the plain we mopped

our

consent

the name of Antonio, showed a marked distaste for this hill-walking, answering

the loud commands to "Get down" by an active and engrossing pantomime representing

the process of a deadly combat, and the receipt by himself of a painful

wound in the right thigh. The Oof-bird's gestures promising ing the fliction

of an equally grave injury to the left limb, however, brought him to earth;

but, to do him justice, it was only when the rats bolted with the trap

that he forgot the limp and pursued them with the speed of a mountain hare.

He was really a wonderful whip, and his handling of those four cripples

on the awkward down-grades would have turned Joe Selby green with envy.

He would pause on the top as one hangs at the dead point of a swing - and

with the same sensation - then let go with the swoop of a vulture down

a twisting mountain road where we swayed between pulverization on the bare

rock on the one side, and a sheer drop to perdition on the other. In full

flight he would rip across six loose gaping planks over some hideous abyss,

whilst an instant vision of one of those rattling feet put wrong sent iced

electricity down the spine. Far sooner would I loop the loop on a hand-barrow

than sit again behind that demon driver, gripping a rotten strap as my

last chance of life. When we arrived with a bump on the plain we mopped

our

![]()

38

brows and said it was exhilarating. So, I daresay, is a jump off the top of the Tower Bridge.

The sun was going down as we clattered up the cobbled street of Kustendil, its minarets standing out of a jagged line of roofs, deep purple against the glow.

The little inn, two-storied and white-faced, was a type of any other in the country. The wide street door opens into a long, low room with whitewashed walls, on which hang at different angles an oleograph of Prince Ferdinand and a print of some smoke-enveloped battle between Bulgars and Turks. A miniature billiard-table stands among its domestic brethren in the middle of a rough wood floor, and in the corner a bar, shelves and counter piled with fruit and crockery. This is the landlord's habitation, from which he seldom emerges. He allows himself a brief outing to greet honoured guests, and now advanced with smiles and bowings. Having responded in kind we fell upon a huge dish of grapes.

Two local cronies of the Oof-bird's presently arrived - need I say a Judge and a Doctor? - who spoke a mutual tongue and were promptly beset for news. The frontier, they thought, had reassumed such calm as it usually enjoyed, and the promising "brush" had failed to sweep down the line and raise the dust of warfare. Still, that same dust was of the nature of a trail of gunpowder, and a spark might start it. Every day more troops were quietly pushing up towards the border - we had passed a couple of batteries in camp by the roadside - and all things were possible.

![]()

39

By dinner time the room was filled with officers and local people, government contractors, and newspaper correspondents, and loud was the clatter of strange tongues round the long table. Confining ourselves to the less dangerous-sounding preparations on the menu we did well, and after a game of billiards - in which the great thing was to keep your ball out of the hole in the middle of the table - we climbed to our bedroom. Owing to a crowded house I was to share my room with a burly Colonel, but what a small share was mine I did not realise until I awoke after ten minutes' sleep, with a growing conviction that that room was one of the most thickly populated in Europe. The human inhabitant of the other bed - curses on his thick skin - snored like a hog, whilst I waged a hopeless war by candle-light.

A cold dawn found me dozing on a blanket on the floor, and the rhinocerous-hide Bulgar dressing with irritating energy.

"Aha!" says he, "vous dormez a la militaire?"

"Yes," I answered, "the bed was occupied."

"How occupied?" - his eyes opened wide. I explained in a word, and

from the way the creature laughed you might have supposed it was a joke.

Skip and the Oof-bird had enjoyed an untroubled night, and consequently I felt towards them that unreasoning grudge always harboured by the sleepless towards their more lucky companions. The Oof-bird had as usual been out on his consuming quest, and discovered before breakfast a coin of the most fabulous age and illegibility, which pro-

![]()

40

duced in him the effusive gaiety and loquacity of a hen with a new-laid egg. At 8.30 Antonio, who had been bidden to appear with the "barouche" at eight o'clock, was summoned and interviewed, by the aid of the Judge.

"Yes, everything was ready for a start, but there were still a few unimportant trifles to be done."

A visit to the stable-yard revealed the dusty vehicle, untouched since last night, and the four prize animals, unadorned, crunching wiry hay in the stable. We overturned the vials of wrath on the complacent Jehu and turned to inspect a "horse" ordered the night before, on which I proposed to ride to the frontier post of Guishevo.

It was a grand up-standing animal of nearly twelve hands high, that is to say (to the unlearned in horse-measurement) about up to a big man's waist. Over it towered an erection of great leather flaps and stuffing, culminating in two horse-hair sofa cushions between which the rider was supposed to wedge himself, the whole being known as a Russian saddle. The pony's spindly legs were finished off with donkey-hoofs, and it looked up to about seven stone with a light racing saddle. Its owner, however, swore by his grandmother's beard that the stalwart beast would treat my twelvestone-seven with amused contempt, and with the example of our four-in-hand in mind I agreed to put its sense of humour to the test. By this time a gentleman temporarily attached to our retinue as interpreter had shown up. He was a

![]()

41

most amiable person with a beautiful black beard, but as he only spoke French, at which neither of his carriage-companions were great hands, their journey promised to be a somewhat silent one. In due time an uproar in the stable-yard announced the starting of our team, which came limping and jangling round to the door, Antonio making a great show with the flail. With Bulgarian punctuality we started at nine, only an hour late. I mounted my pocket Pegasus, wedged myself between the horrible cushions, and with my toe-tips in a pair of child's stirrups, started after the party at a staccato semi-quaver trot.

From Kustendil to the frontier at Guishevo is about fourteen miles, over a road originally paved with foot-square blocks of stone, which now stuck out of the dust at all angles. Pear-trees and vines here took the place of the plums, and we were soon hard at work on a free fruit breakfast of the finest. A little way out lay a regiment of Reserves in camp, under rows of what Skip calls "dog-tents"- a length of canvas flung across a horizontal pole and pegged down at the sides, which are neatly turfed to keep out the draught. Inside is a thick layer of straw, on which there is room enough for three men to lie side-by-side. They were serving out the day's bread-ration - flat brown loaves with string-coloured crumb, of capital quality. These and the universal tchorba soup are what they live on, and the stiff and wiry look of the men shows how well it agrees with them. They swarmed out to the roadside ditch to look at us - men of all

![]()

42

ages,

from the wrinkle-faced peasant of forty-five to the short-service man of

half his age. The older men, called back to the ranks after fifteen years

of farm life, wore their coffee-coloured uniform slouchily, and some of

them "stood over" a little at the knees, but the others were well-set-up,

determined-looking fellows. All had a certain air of usefulness, and there

was not a stupid face amongst them. They wore thick white flannel leggings,

some with elaborate braidings and broad black bands criss-crossing over

them. The leather-thonged cowskin slippers of the Balkan peasant were universal

- only the Line are served out with boots.

ages,

from the wrinkle-faced peasant of forty-five to the short-service man of

half his age. The older men, called back to the ranks after fifteen years

of farm life, wore their coffee-coloured uniform slouchily, and some of

them "stood over" a little at the knees, but the others were well-set-up,

determined-looking fellows. All had a certain air of usefulness, and there

was not a stupid face amongst them. They wore thick white flannel leggings,

some with elaborate braidings and broad black bands criss-crossing over

them. The leather-thonged cowskin slippers of the Balkan peasant were universal

- only the Line are served out with boots.

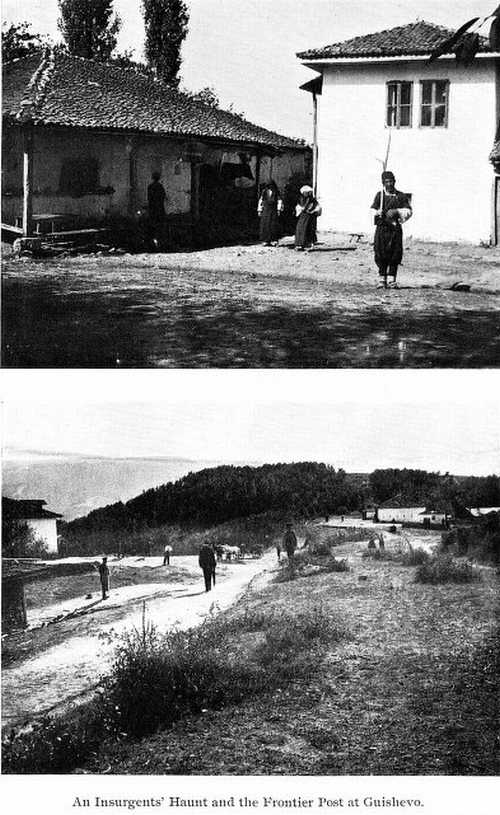

A mile or two further on a grinning peasant showed us a little white house and a low cottage, which had for long been the sheltering place of Dr. Romanoff and his band of insurgents [Photo, p. 46]. The proclamation of martial law in the district a couple of days before was the signal for their flitting, and they vanished into the hills. In this dark grimy hovel they sat on the uneven earth floor discussing their plans for the discomfiting of the Turks, and here they manufactured the dynamite bombs that have established such a terror in the

![]()

43

heart of the Moslem, whilst the women pounded the butter in their queer-shaped churns. These are like a very tall wooden bucket, narrowing towards the top, in which they puddle with a wooden staff.

Another hour's travelling through a flat country brought us to a little hamlet at the foot of the frontier range, from which the road to the top shot up abruptly. Here was a convenient rest house - what the Turks call a Khan [Pronounced "hahn."] the owner providing shelter but no food. Being forewarned we had brought our own, but as knives and forks were unheard of sat down and rent a cold chicken limb from limb with pocket-knives and fingers. It was here that I determined to get rid of the "Slav" element in my saddle, and soon discovered a buckle which, when loosed, freed the diabolical cushions from their resting place. This unorthodox proceeding was met by the strong disapproval of Antonio, but I stuffed the offensive things into the box of the shandrydan. Though shorn of its chief glory the saddle was now more adapted for human use. The only creature which could have bestrode it with any comfort in its early stage is a monkey. The Black Rat so far had gone surprisingly well, though not, towards mid-day, with the flippancy of the first few miles.

To the guard-post on the crest of the hill was about two miles of very stiff climbing for horses, so we left Antonio and his charges to follow at their leisure, bringing with them in lordly state

![]()

44

the interpreter, who politely demurred when the project of going up on foot was mooted. The sun beat straight down on the unshaded road as the three tramps plodded dustily upwards in shirt-sleeves, the Rat - coat-laden - following obediently. Half-way up the carriage passed us with its tender load lolling under an umbrella and complacently stroking its silky beard. Antonio, having caught the spirit of the thing, was walking of his own accord some little way behind. We sat down for a minute on the bank, and were hazily calling to mind the French for "lazy swab" when the team bore away a couple of points towards the side of the road where the turf dropped almost sheer to the bottom of the hill. The near fore wheel rose over the low bank, Antonio jumped forward with a blood-curdling yell - the umbrella rose in the air, and the form of the linguist translated itself to the road with a bound. He walked to the top.

Turning an upward corner we came suddenly upon a little low white block-house, in front of which stood a Bulgarian sentry leaning on a bayonetted Männlicher. As the man questioned us a blinking brown face looked out, disappeared again, and out straggled the guard. They made no attempt to fall in, but hung round whilst we enquired for the officer commanding the post. By ill luck he was absent, and without him no man might pass over the imaginary but important line to visit the Turks in their little similar white house forty yards away. Outside it their blue-clad, red-fezzed

![]()

45

sentry paced slowly, and three or four figures strolled out, squatting in the shade of the loopholed wall to examine the strangers. Behind them the oak-covered hump of a hill rose, and away across the valley to the south towered the bare heights of their first line of defence. If I had been allowed then a peep into the future, I might have seen myself, a few months later, dodging about those same hills chased by the Turkish police.

Along the crest past us wound a foot-path northwestward to another Turkish guard-house. Down this through the short oak scrub came presently five or six men in single file on their way to relieve guard.

![]()

46

They swaggered by within a couple of yards of us led by a short, lithe,

hawk-nosed man whose white cap stamped him an Albanian. A broad red sash,

cartridge belt buckled over it, covered all but the butt and muzzle of

a gigantic silver-plated revolver. On one shoulder he carried jauntily

his short blue jacket and a Martini-Henry rifle. He glared evilly from

under his scowling black brows. It appeared that we were honoured by being

taken for leaders of the Macedonian Committees, and nothing would have

pleased these warriors better than to get to work on us with their Martinis.

Having watched them safely off the premises it occurred to Skip and myself

to take a walk through the oak trees and reconnoitre the Turks' stronghold

on the hill, so off we started. The sergeant of the guard was not so minded,

and presently a soldier, followed by the panting man-of-tongues, arrived

at the double to hale us back. But the Bulgarian "Tommy," like his British

brother, is an obliging fellow, and we went on. He said it was the head-gear

that put the Turks off, in particular my tweed cap, which only insurgents

wear in that part of the world. The idea of swopping caps did not appeal

to the soldier, however, and we had to be content with crouching in the

bushes, cap in hand, fifty yards from the guard-house. There was not much

to be seen of it, but sufficient for the interpreter was the proximity

thereof. On the way back I took a photograph in which you see the Oof-bird

considering the possibility of hidden treasure, and one of the guard coming

to move us further into

![]()

An Insurgents' Haunt and the Frontier Post at Guishevo

![]()

47

Bulgaria. A little notice board - " Passengers are requested not to cross the line" - could be done quite cheaply and might avert possible death by lead-puncture. The grey-eyed sergeant - a man of much responsibility who carried it well - could hold out no hopes of his officer's return before dark. Alarm fires had been lit the night before in the Turkish valley, and firing had been heard to the westward, so the Captain had gone out to investigate. The famous brush had happened in that direction too, and the sergeant and his men had only had to stand by and wait for whatever luck they might have.

"Ah! the Turks over the way here?" - he smiled tolerantly - "Not bad fellows, but impatient - impatient. They shall have their beating, all in good time, you know - all in good time."

So here at least was no war. Antonio was dragged blinking from the depths of the guardhouse, and a brawny soldier-lad led out the Rat - perhaps he did not often see silver, but it is rather a queer sensation for a man to kiss one's hand. Jogging quietly down the hill I watched the rattletrap disappear round the corner like a streak and thanked my stars I was not in it.

We made Kustendil by sunset, and the Rat, to his everlasting credit, finished strong. Foregoing the temptations of the "middle pocket" billiard table, we held solemn conclave after dinner and decided to push on to Dubnitza, en route for Samakov, both frontier towns to the south-eastward. Certainly trouble was a long time coming, but

![]()

48

the Army, to judge by its representatives at Kustendil, was full of hope.

After dark an infantry escort marched silently past with half-a-dozen

refugees who had just come in over the border. As these slouched by in

the dim light of the soldiers' lantern, one of them plucked the hated fez

from his head and flung it into the gutter with a hoarse chuckle.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]