17

PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER II.

In the din of a troubled year.

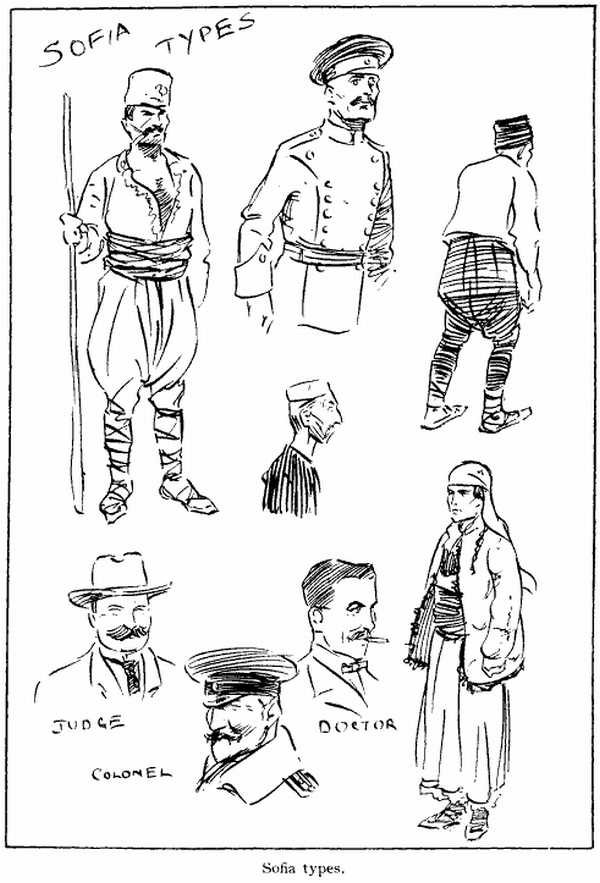

THE Capital of Bulgaria is young, well grown for its age, and mighty proud of itself. A trifle gawky yet, and having outgrown its clothes a little where its long limbs of electric-tram lines ramble out past scattered, half-built houses to the open country, and suddenly break off, wondering why they have come so far. The town is working all the time, and the main street is positively busy. It has a South of France look; white house-fronts, persienne - shuttered windows, and acacia trees shading the buzzing café-tables along the footway. Brown and grey-clad troops, officers on curvetting little Hungarian horses, dark-blue Mounted Police, and gay-coloured market-folk with their bullock-carts pass in the roadway; the noise of drums and bugles and the "clang, clang" of electric-tram gongs are in the air.

And at that time there was something electric in the air that had nothing

to do with the trams: a feeling that struck the new comer at once - the

town vibrated with it - and that was war. Nothing else was talked of in

the choked restaurants,

![]()

17

Sofia types

![]()

18

on the clustered pavements, or in the open streets. Groups of excited men chattered in low, quick speech out of doors; inside they huddled over the café-tables, heads together, hands talking as well as tongues, with suspicious glances at unknown neighbours.

Here were men who could give you twenty sound reasons why there must be war in a week, and you passed in a spirit of elation to others who proved by a score of incontestable arguments that no such thing could happen in the present decade. Newspapers were waved in support of some emphatic prophecy and promptly torn to ribbons by a frenzied opponent in an endeavour to "read between the lines" - certainly at this stage an easy matter.

Armed with a chit from a mutual friend setting forth our presumed respectability, we sought out a brother-correspondent, who was engaged in the rather heating occupation of sending red-hot news to a famous paper which likes it frizzling - and if it gets a little "overdone" sometimes, what matter? In the intervals of cook - er - corresponding, he hunted untiringly for aged coins, but even as the news was never new enough to please him, so the money was never old enough, be it never so battered and shapeless. He steered us through the turmoil of the tables, and with many bowings we became known to the great ones of those parts - two Judges, two Colonels and two Doctors. And here let me remark of these honoured titles, that no self-respecting Bulgarian is without one.

![]()

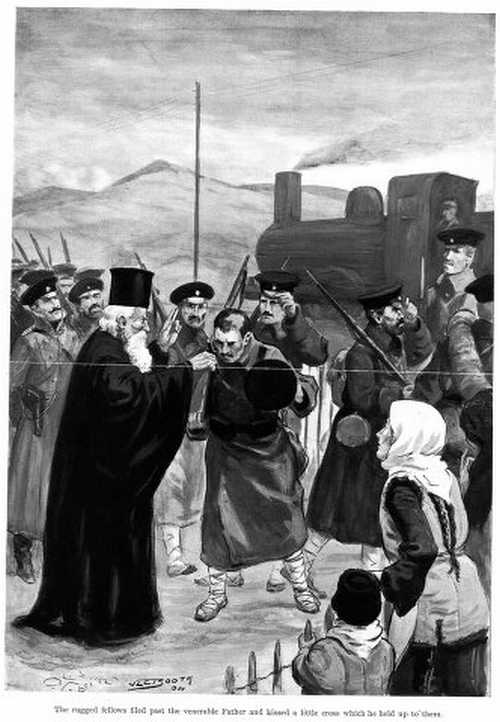

The rugged fellows filed past the venerable Father and kissed a little

cross which he held up to them

![]()

19

The army, of course, was hot for war, and the enthusiasm of our Colonels should have moved any Government to throw down the glove at once. All was ready - troops massed on the frontier, most of the reserves mobilized and the rest coming in; stores on the railways - in fact, barring a slight shortage of rifles (this we learned elsewhere) the military machine was in sound working order, with a great head of steam up, ready for the word "Go."

Naturally the soldiers were confident, and from what we afterwards saw of them and their organization I think they had good reason to be so. The whole population (with the possible exception of the merchants) was rampant for war. The doings of their Moslem neighbours over the border - the slaughterings and burnings - were nothing new; their own fathers had known that life, and the deep, inborn hate was always there. But Free Bulgaria has grown astoundingly and developed its muscles, and now it saw a chance of hitting back hard enough to hurt. The army went about its business quietly and with a good deal of secrecy. A Regiment of Reserves marched to a siding on the line before dawn the morning after our arrival. An old Exarchate "pope" (as their holy men are called) was waked and bidden to come and bless the troops. The rugged fellows filed past the venerable Father and kissed a little cross which he held up to them. Rough and untaught as they were, they knew it was the symbol of what they were going out for, and a tear stood in some of

![]()

20

their sun-wrinkled eyes as they gripped each other by the hand and climbed into the train. Of course there were the women and the youngsters, who have been there every time since first men went to fight.

Rather choky, those little plain Bulgarian women, left out of the calculations in this big, important business of the strife of nations, but showing mostly a straight back-bone, like the sorrow-hardened breed they are.

That afternoon we tried to get a look at Prince Ferdinand, and waited with a camera near the smart, plumed sentries at the Palace gates about the time he was due on his daily drive. But his Highness slipped us and went out by another gate, so we took a stroll through the baking streets. Suddenly, in a side-road, behold the royal escort sitting on their horses under some big trees which shaded the entrance to the royal menagerie and aviary, inside which was the Prince, looking at his birds. And there he stayed most of the afternoon and wore out the patience of two thirsty men who had come fifteen hundred miles to see him, so that they finally retired to seek cold liquids at their caravanserai.

Next day my friend the Judge took me to Dr. Tartarcheff, president of the Revolutionary Committee of the Interior, who was good enough to make clear a few of the many hidden things connected with that much-misunderstood organization.

At that time the insurgent bands were harrying the Turk across all Macedonia, controlled, to a

![]()

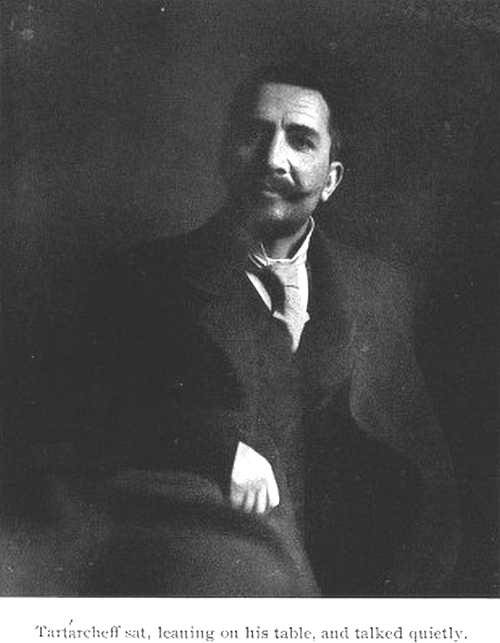

Tartarcheff sat, leaning on his table, and talked quietly

![]()

21

large extent, from Sofia. They worked at distances of hundreds of miles apart on a given plan, and arms were distributed to the villagers and general risings brought about to the hour, throughout enormous districts, by the workings of the Exterior Committee - the leaders in the field.

"We have done a great deal this year" - the Doctor spoke in French - " but not a tithe of what we shall do. We are bound to go on so long as we have money and arms-men there will always be. You think it a hopeless task, but you are wrong. Sooner or later - it may be this year or it may be ten years hence - Europe is bound to help us, and until that happens we will stop at nothing. The Macedonians are not fighting for franchise - they are fighting for life." Tartarcheff sat, leaning on his table, and talked quietly, as a man might explain why he bought a tweed suit instead of a serge one - without particular enthusiasm. It was well covered.

He showed me a copy of the insurgents' newspaper, L'Autonomie, a unique thing in journals. The "births, deaths and marriages" column was all deaths, and those of the most violent. The leading article commented on these and set forth a desire to kill and slay in return. The parliamentary news quoted the views of prominent senators on the probability of war. "Country Notes" recounted appalling barbarities inflicted on Christian villagers by the Turks, and the foreign telegrams showed what Europe thought about it. If this little Family Weekly could be translated

![]()

22

into English and sold in the Strand our dear old "Largest Circulation" would have to hide its diminished lists.

I asked after Saráfoff - best known and most active of insurgent leaders - who was at that time undergoing one of his temporary deaths in the newspapers, which published his obituary and revival alternately about once a month. The great little man, it appeared, was not only alive but kicking uncommon hard - pushing about among the Macedonian mountains and intruding on the privacy of the Turkish soldier out of calling hours, in his own unconventional way.

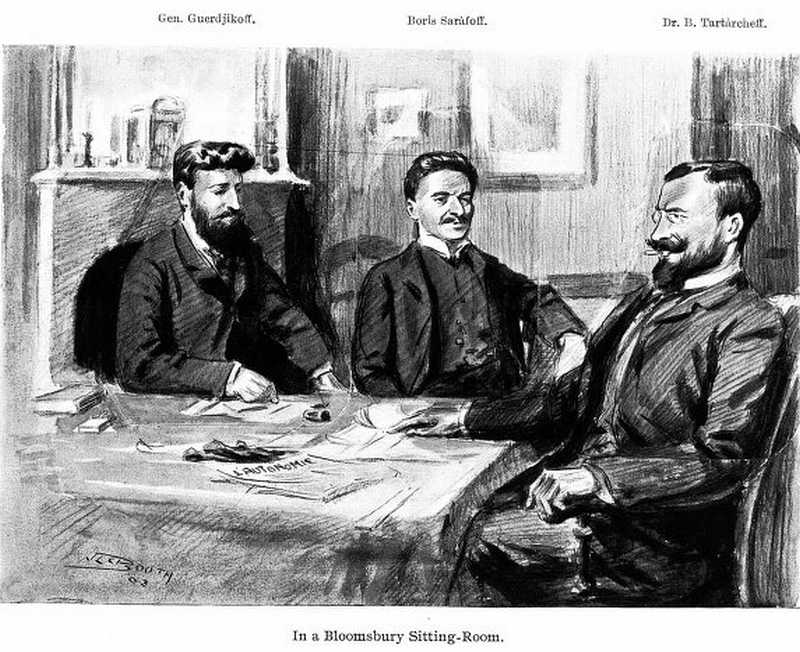

I always used to picture Boris Saráfoff (accent on second syllables) as a big black-bearded brigand with a fierce scowl, in a vague setting of lethal weapons of ancient but uncomfortable design. Some months afterwards, in a Bloomsbury sitting-room, I was introduced to a quiet little brown-faced man with a humorous twinkle in his eye and the Sultan's price on his head, who sat beside me that night at the Palace Theatre laughing at the antics of a couple of knockabouts. The rest of that little party were General Guerdjikoff (an insurgent leader with a big reputation) and Dr. Tartarcheff's brother, who is the Committee's agent in London.

Saráfoff's eye was caught by a mechanical cork-extractor in the bar. " Mais ils ont des machins pour tous-même pour ouvrir les bouteilles!" - said he.

His success as a leader is not difficult to under

![]()

Gen. Guerdjikoff. Boris Saráfoff. Dr. B. Tartarcheff.

In a Bloomsbury Sitting-Room

![]()

23

stand. He has a strong personal magnetism, and under his quiet manner and pleasing exterior he conceals a motive power and a tenacity of purpose that have carried him and his men through all their wild times.

The Doctor said, "No war." The Government would not come up to the scratch, and the insurgents would have to do the work by themselves in their own small way. So I went out to find one of those "war-in-a-week" men to talk to and gather consolation.

In the afternoon there was some gun-drill going on at the Place d'Armes at which I was not welcomed, so turned to watch a batch of young unbroken cavalry horses being shod. The blacksmith's forge was in a small shed, round which reared and kicked and plunged a dozen embryo chargers, hauling with them clusters of men who clung to reins, ears, mane and tail like hounds pulling down a stag. In front was an equestrian group which might have been carved in stone. Eight men leant inwards upon a young bay horse - motionless. One held its upper lip in the handles of a pair of blacksmith's pincers. Another hauled on a cunning rope-and-ring arrangement which, with one end tied to the tail, hauled the off-hind leg into a handy position for the smith to work upon. The others gripped where they could, and all strained forward, breathing hard, as the smith trotted up with the blue-hot shoe. The little horse, quivering with terror, showed a wild white eyeball and blew noisily through wide-stretched nostrils. As

![]()

24

the shoe sizzled on the pared horn he plunged with a snort and carried his hangers-on half-way round the shed, the blacksmith following with deep roars of Bulgarian blasphemy. The shoeing of a draft of twenty-five, I imagine, is a matter of some weeks.

The cavalry are all horsed from Hungary, and get a capital stamp of animal - the sort we were looking for in South Africa - fourteen-two to fifteen hands, and up to weight. Not that the average Bulgarian is a heavy man, but with his high Russian saddle and big "packs" he needs something sturdy.

By way of plunging into wild dissipation we went that night to a café-chantant, and suffered the most lugubrious performance that ever dared to call itself an entertainment. The audience (who had mostly the wisdom to stay away) sat at little tables up the sides of a dismal room and consumed turpentine-and-sugar at the price of Perrier-Jouet. To distract their thoughts from this Arcadian draught a succession of ill-balanced females, all too stout or too thin, appeared upon a gaudilydraped platform in dull flannel blouses, and crowed through a jangle of discords hammered out of a lame piano. As each finished her lamentable effort she wandered round the room collecting sous from the jays in a tin plate. At the end of twenty minutes, having thoroughly corroded our tongues at the trifling cost of some thirty francs, we tore ourselves from the merry revels, Skip in his disgust being with difficulty restrained from "shooting the lights out."

![]()

25

The next morning, as none of the papers (contrary to custom) reported that war had been declared during the night, it struck me as a desirable thing to take some bodily exercise in the form of a walk to Dragaleski monastery, said variously to be at two, four and six miles' distance from the hotel. Going into Skip's room to present this proposition, I found him rolled up in his bed-clothes on what looked like a large table upside-down on the floor. This was none other than his bed, right side up but legless. In the silent watches of the night the two lower legs had suddenly crumbled away, leaving the recumbent figure at an angle of thirty. So being a man of resource and prompt action he quietly arose, tore away the two upper legs - thus reducing his bunk to a decorous level - and turned in, all snug and comfy. He did not receive the walki-dea with the enthusiasm the occasion demanded, so I set out alone. Any previous ideas I might have had about the road were washed out and completely effaced by the streams of information poured upon me by the hotel clerk, who, after the manner of his craft, endeavoured to describe two entirely separate routes in alternate breaths, and - most fiendish cunning of all - drew in green pencil a fearsome map, which looked like nothing but the Sultan's signature, on a piece of pink blotting-paper. Refusing this tempting gift I left him, and tramped to the outskirts of the town, where I seized a countryman and repeated "Dragaleski" with solemn emphasis until he pointed out a straggling track. He shouted after me accurate directions,

![]()

26

no doubt full of interest to anyone who understood Bulgarian.

The track went through a barrack-yard across which I was led by half a dozen friendly soldiers all talking at once, and by the time we reached the other gate we were on a footing of life-long comradeship and laughing hugely at each other's jokes (which is often much easier when you don't know what they are). Up a dusty rise, and from the top a clear view over five miles of country to a range of woody hills that grew bigger and bigger as they went back. A darker patch of trees where they joined the plain might be the monastery; nothing else looked like it. The country between was a rolling veldt of bleached grass and sandy earth; here and there a bush and a few cultivated patches towards which my track seemed to lead, but half a mile away it was lost in the plain. A Mounted Policeman cantered past with a puzzled glance at the camera and haversack. With a good breeze behind going was comfortable, and the direction easy enough to keep. The wheel-tracks, spread across a hundred yards of ground, showed that each man chose his own line and drove with the sole idea of making a point. Now and then the lines collected to cross a boggy bit, like a field of sportsmen cramming through a gateway, and promptly spread fanwise again. Bye and bye some white houses could be made out among the leaves ahead, and a stunted church-spire roughly tiled.

The belt of trees materialised into a plum-orchard heavy with blue fruit and bordered by a stream

![]()

27

running a great pace, in which two or three women were washing clothes. Their heads were covered with white kerchiefs and two wore sheepskin jackets. All had narrow blue petticoats and the native skin sandals laced with crossed thongs. They were not beautiful; indeed, I have seen very few Bulgarian peasant-women who were not extremely plain. They have mostly shrewd and kindly faces, though, and are wonderful workers, eminently useful at the few things they know. The village was spread about among the trees, each house standing in its own grounds, as the advertisement says. Little one-storied places with white-washed walls and red, overhanging roofs. Spying a table and stools outside one of them, I tackled a small boy in the doorway, and demanded food with gestures representing vigorous mastication. He was thoroughly scared and ran bawling into the house, but his mother had an instinctive knowledge of the sign language and the wants of wanderers, and produced some of the native sheep's-milk cheese which I afterwards grew to know well and value exceedingly. To the ignorant eye it seems nothing but a lump of wet white chalk, but fresh and in good condition it equals many a proud home product at fifteen pence a pound. Five farthings is the native price. With this, the good brown country bread and homemade red vino, a hungry man can do well.

Then came a couple of voluble engineers who talked in French and were laying a conduit from a mountain stream to Sofia; but I had not come

![]()

28

out to see waterworks, so wished them all luck with their pipe and pushed on up the hill to the monastery. Out in the open I met their stream, harnessed long ago by the natives into old hollow tree-trunks, laid lip to lip on rough stone-piles, with the water tearing and splashing through them like a mill-race. And these people in squash hats and little black ties were going to take it out of its old familiar tree-trunks and run it through a vile iron drain.

Over the hazel-trees ahead the monastery walls came into view like some old fortress, with little windows peeping high up along the top of them. The wind blew heartily, and the branches whipped and whistled to the rustling of the brown leaves as I climbed round the foot of the walls and found the ancient gateway with its high wooden gates open. At the top of the sloping courtyard, past a white chapel and little low-roofed house, stood a long two-storied building, white, with a brown wooden gallery running along its upper story, and a dark-red roof like the rest. I turned to the low house and stooped through a dark doorway.

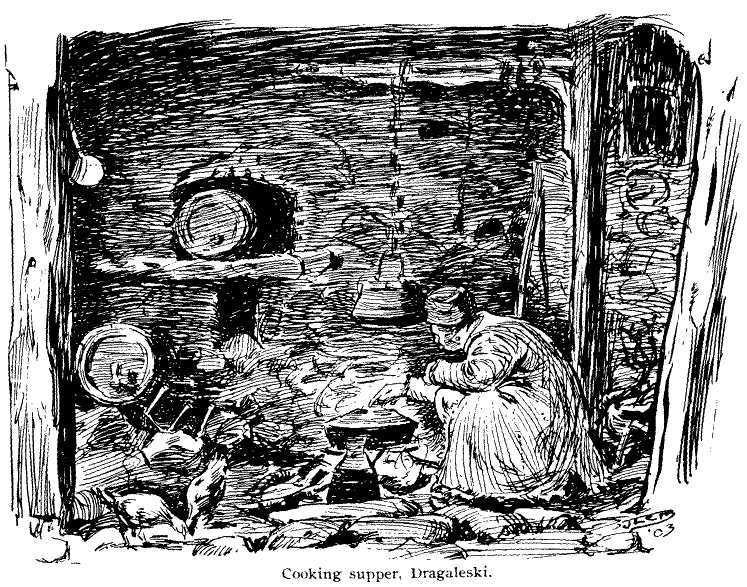

Inside was smoke - thick, stinging and impenetrable. Presently a dim light took the shape of a small open window, then a little flame showed on the floor, and gradually, as a dark scene on a stage slowly reveals itself, appeared the figure of a man bending over a wood fire in a great black stone chimney with rough wooden pillars rising round him, and a big cooking-pot hanging from a beam. Barrel-ends stuck out of black niches in

![]()

29

Cooking supper, Dragaleski

![]()

30

the chimney wall, and round the fire two or three hens pecked about in a jumble of big stones, pine-branches and iron cooking-stools. The floor was hard-beaten earth, out of which blackened pillars rose in odd places to mysterious beams above. The acrid smell of wood smoke pricked the nostrils as it tried to escape through a tiny hole in the roof, towards which the sides of the great chimney leaned, but the wind drove it down until some of it found its way out through the doorway and the tiny window. The man, in sheepskin coat and fur cap, offered his visitor a footstool, but by this time the visitor's eyes were smarting intolerably and he retired, to stand blinking in the courtyard whilst the wind blew the smoke out of them. By degrees the atmosphere cleared, and I accepted the rickety footstool, which had been built, with patient ingenuity, so that it should not stand up. However, with a stone and great caution I kept it on its pins for half an hour, and sketched the rugged chimney. Then a dark, burly figure appeared in the doorway and a round, grey-bearded face under the chimney hat of the Exarchate Church smiled over my shoulder at the sketch-book.

How can I describe thee, O! most worthy monk? Thine old rough-cut and kindly face, eyes of light-blue with a twinkle intensified by the deep crows' feet at the knowing corners; thy grand and honourable beard, spreading its iron-grey curls across a broad black chest - or would - be black, for thine ancient cassock had faded under many a summer sun and winter rain. Its green, uncertain edge

![]()

31

I flapped round thy broad half-boots in old and unmistakable familiarity.

We had, perhaps, six words in common, and those German; but what need to talk with such a man? The bright flame of charity and true hospitality burned within him, and he read each idea as if formed, like a yeoman-of-signals reading the rolled flags as they go aloft, not yet broken out. And how did he convey to me, later, that my supper would be ready in an hour, and that meanwhile I could walk round and look at this quaint little town of his, a hundred yards broad? Frankly I do not know, but remember that it was all clear. I went up into the woods and looked down on the red roofs, whilst a string of labouring buffaloes slowly hauled their screaming waggons up the track, and a wizened shepherd drove his bony flock within the walls.

Great rolls of dark, forbidding cloud came over the setting sun and spread across the sky. The last waggon stopped its screeching and the last sheep straggled in as the chapel bell began to swing in the wooden tower, and as it settled to a steady "tang-tang, tang-tang," the old tottering gates were shut-to for the night. Now the sullen clouds were overhead, and on to the dry leaves fell the first big drops of a heavy rain.

I slipped back through a postern door in the west wall and sat under a little thatched shelter outside the old house, smoking a pipe and watching the raindrops forming little dusty globes in the thick dust of the courtyard. Just as the ground had all

![]()

32

turned brown and slimy came a mighty slap on the knee, and there was that benevolent old face saying "supper," plainer than speech. I followed his broad back through low, skull-cracking doorways and dark passages till we came into a lighted room. No surely not a room - a chapel! Perhaps twenty feet by ten, and evidently no longer used for its real purpose. The floor at the east end was a few inches higher and had a short barrier at the "break" of it. Under the broad east window, where the altar must sometime have been, was a couch, and along the side-wall a table with white cloth spread ready for a meal. Above this, in a round-topped niche stood a statuette of the Virgin Mary, round the feet of which withered flowers clung and tin ornaments glinted. An oak-panelled confessional filled the other end, with blue and gold paper above it to the ceiling.

In came my cook-man with a great steaming bowl of tchorba - the native soup - thick, red, and very filling. A bottle of what Father Benvolio called Schnapps was on the table. Would he drink a glass with me? To be sure he would; so I filled him a bumper, and there, in that strangest of dining-rooms, we clinked glasses and pledged each other jovially, and I swear I waited for him to break into the Abbot's song from La Poupee.

But instead he broke into the confessional and lugged out from its recesses blankets and sheets and a pillow, explaining in his wonderful way that they were his own, and therefore quite safe. These he spread on the couch, and left me. May

![]()

33

he live long to trundle round the village in his old wide boots, for he was one of the best.

The wind battered the wet branches against the east window, and now and again a thresh of rain crossed it and showered the floor through a broken pane. The chapel was on the outer wall, and I could hear between the blasts the splash of water a hundred feet below. As I turned in and put out the smoky old lamp a couple of rats scampered along the skirting-board; but the couch was as comfortable as any spring bed, and I never slept more soundly.

In the morning it was still raining heavily, so after a cup of coffee in the Black Place I started on a run for the village, and was lucky enough to find a wandering carriage leaving empty for Sofia.

Skip was playing Patience, and life was for a space bound up in making the game "pan out." This done, I learned that there had been a brush between the Bulgars and Turks at a frontier post near Kustendil. "Three cheers for the gallant post-men, and long might they continue brushing! " Maps were hauled out, and the coin-collector called to a great war-indaba, at which it was proposed, seconded, and carried nem. con. "that the present company do put themselves with all dispatch into such vehicle, conveyance or other canasmus as shall most abruptly deliver them at the scene of the aforesaid brush."

"And plenty of bristle to it," added Skip, putting on his disreputable

straw hat at a determined angle.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]