50

PART I. BULGARIA, 1903.

CHAPTER IV.

. . hearked to rumour, and snatched at a breath,

Of ' this one knoweth' and ' that one saith, -

A COUNTRY with the prospect of immediate war hanging over it is generally supposed to show some signs of disquiet or unusual stir. Not so our placid Bulgaria. At night, sure enough, the existence of martial law turned all civilians indoors by eight o'clock, but by day - beyond running across a cavalry patrol or an infantry camp now and then - you could wander the country through and never suspect the finger on the trigger at Headquarters. The stolid tillers of the soil did not concern themselves with affairs of state. If there was to be a war, well and good; but there was no reason why the cows should not be driven out to graze in the morning and all the other little daily doings gone through, as they had been for a life long. So Ivan keeps his eyes for his own job, and gathers his fruit-harvest or follows his mild-eyed buffaloes down the road as untroubled as they.

The ceremony of departure in these parts is a heavy one, entailing on the traveller the consumption of a mystic drink known as Slivovitz (the

![]()

50

spelling must take its chance), in quantities according to the number of friends who share the sweet sorrow of parting. The stuff itself is a sort of plum-gin, colourless and very potent. The act of paying the bill produces a tray of it in little glasses at the personal expense of the landlord, and after the warriors, law-givers, and medicine-men on the premises have wreaked their hospitality on the wanderer, he finally escapes to his conveyance, content to watch the world go by, and with no desire whatever to walk up hills.

Antonio, in the blatant glory of a new snuff-coloured great-coat, put on an insufferable swagger until the cobbles of the town gave place to the easy dust of the country road, when the gorgeous garment was hidden reverently away. Along a wide valley we trundled, making out the Radomir road trailing up the distant hills on the left like a piece of white cotton. Over the banks the thick vines spread and crossed from row to row of sticks, half-hiding blue bunches of little grapes; on the other side, pears in ripe clusters hung out over the road invitingly. Standing on the seat we pulled these down in handfuls, whilst Antonio with native cunning plunged deep into the vineyard for grapes untouched by the dust of the road, which powdered everything for twenty yards back. Under the same old burning sun we travelled, coatless, on and on, whilst the bees buzzed round and the dust settled quietly on everything, covering all as the sand covers a ruined sea-castle. At a bend of the road lay a colour-picture that will stick in my mind's

![]()

51

eye always. A broad cabbage-patch of gorgeous purple dotted with orange-coloured flowers; in the midst a boy with orange flower in cap and bright red sash; behind him a white-washed house, red-roofed; green plants, sandy hill, and turquoise sky. Everything was in its place - there was nothing wanting. It was the most perfect nature-picture you could wish to see, and I have never spoilt the memory of it by trying to paint it.

Now and again we left the road and silently rolled and swayed over the bleached grass to cut off a corner. Then a "sloosh" as the wheels sank in a grey bog-patch, and the squashy, sucking sounds of sixteen legs pulling out of the deep slime. In one of these crossings was a country waggon, two wheels fast bedded in the mud and its load of corn sacks all slid over to the sunken side. In it stood an old wizened man holding with one hand to a corner-post and prodding the straining buffaloes with a long pole. The more they hauled, the deeper went the buried wheels, and further sagged the heavy sacks till the crazy side-rail creaked under them. Pulling up on the sound going, Antonio arose and yelled advice with much instructive gesture, till the old man, dropping his pole, grabbed his sacks and hauled them one by one on to the upper rail. As we left him his slanting floor was slowly levelling up on to dry land.

At midday we "outspanned" by a running stream under a wide acacia tree, and, stretched in the shade, watched the water flowing clear over yellow sand. A herd of swine, followed by a little

![]()

52

bare-foot girl, turned off the road and ploughed through the sand with inquisitive gruntings, jostling each other into the water. Their little herd-woman, grave with the responsibilities of her office, turned her shy dark eyes on the queer-looking strangers under the tree. Her white kerchief glared the whiter against the clear tan of her shaded face. She paddled down stream, cooling her dusty feet and kicking the water playfully on to a straggling pig.

Then came a string of pack-ponies, with wooden "hen-coop" saddles reaching right over the withers, and brown rugs covering the piled merchandise under a network of cross-cording. Beside them strode long spare men of the hill-breed in blanket kilts edged with black braid. Some of their leather belts had a wallet in front with a flap cover, from under which stuck out the ornamented handle of a long knife. Striding big and steady, these hardy rovers cover incredible distances with their pack-trains between dawn and dark, doing most of the carrying trade of the hill districts and those parts of the interior which have never heard a railway-whistle. For one still hour under the acacia the panorama of peace passed by, whilst the team kicked at the

![]()

53

flies and crunched their feed of corn from a rug on the ground. In all that day's trekking there was no sign of the cloud which overhung the country. All was calm, and quiet daily labour.

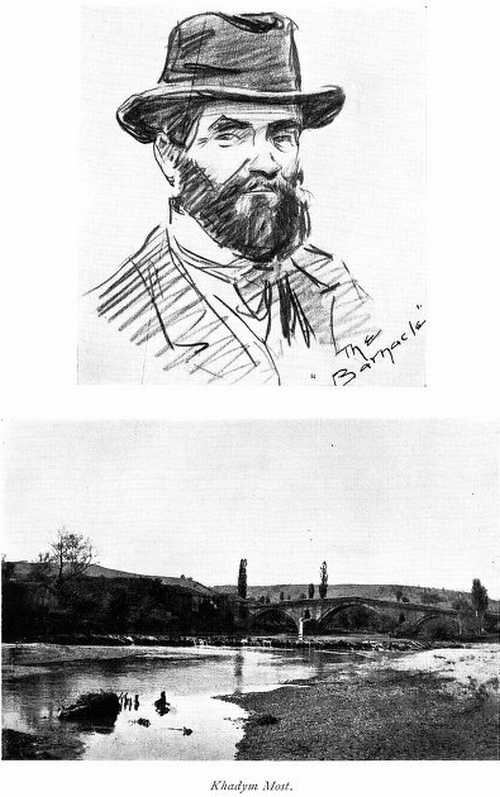

In the afternoon we rolled across an old Turkish bridge called Khadym Most, over the wide and shallow Struma river. Khadym is the Turk's name for the most beautiful woman in the harem, so it might be translated "beautiful bridge." A fine old grey structure, and an important strategic point on this main road to the capital. [Photo, page 56.]

Four o'clock found us taking the boulders of Dubnitza main street at the pulverising gallop reserved by Antonio for such occasions, which effectively shook the dust from the racked shandrydan and its bouncing hangers-on. No sooner were we inside the inn door than crowds of men, who all seemed to know us, came and clacked like looms without ceasing. Once again war and rumours of war. A village over the border sacked and burned, and the villagers straggling in by hundreds over the Rilo range to the monastery and the neighbouring towns. Insurgents and Turks hard at it, hammer-and-tongs; the Bulgars outnumbered and retiring on the border-line, or the Turks caught in an ambush and treated with great slaughter. War to be declared at once - they had it on the highest authority. A subaltern who had come in that very afternoon with the cavalry had seen a man who was reported to have said, etc., etc.

![]()

54

Among those whose rôle was to know more than they would say was one who stood out as an evident past-master of the art of wink-and-nod. He spoke American with a Bulgarian accent and introduced himself as a dragoman moving in the highest circles. This lofty profession apparently entailed the most strenuous physical exertion, as its present ornament's garments were rudely overused and his collar of that subtle grey hue obtained by a long estrangement from the wash-tub. In his moments of leisure, he explained, it gave him peculiar pleasure to offer his great store of knowledge to any Americans or English he should happen to meet. He loved America as his own home, and the qualities of the Anglo-Saxon race appealed to him irresistibly. By a slight oversight he allowed his drink to go on our bill and accompanied us into the street, where in the space of one minute he pointed out the Post-office, the barber's, the barracks, the town-hall, the best hatter's and the worst café, with a wealth of detail that commanded the admiration, if it slightly fogged the mind, of his convoy.

In the mysterious way known to his craft he divined the Oof-bird's great mission, and led him, with solemn winks of deep portent. to where should be revealed "the mammoth coin collection of this country, I tell you." Switching his attention back to Skip and myself his beard wagged down one smelling alley and up another until in a crowded half-hour I knew far more of Dubnitza than I do of any place I ever lived in. Slipping and

![]()

55

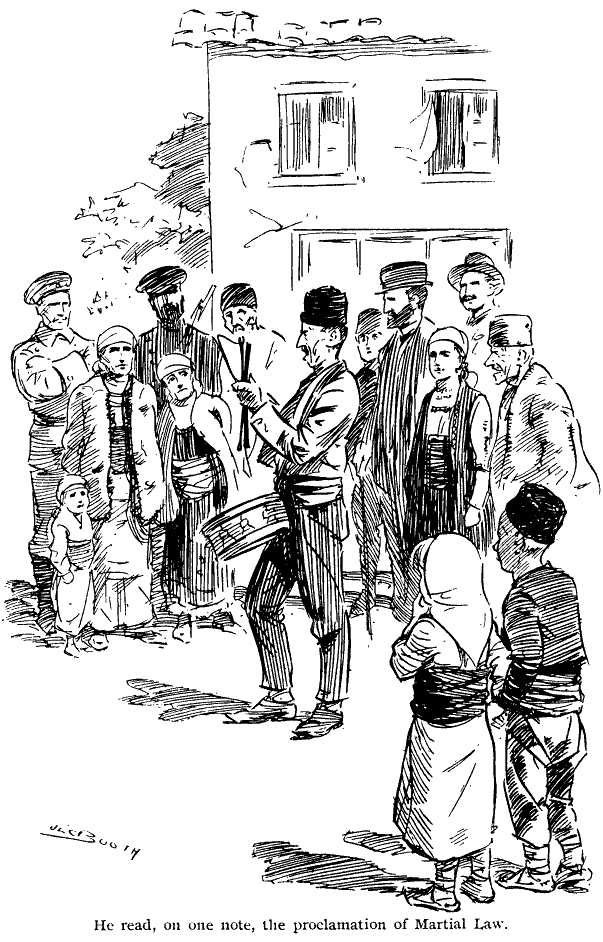

He read, on one note, the proclamation of Martial Law.

![]()

56

tripping over the great ankle-twisting cobbles of its dirty streets, we searched its dozens of potter's shops for anything original in design or work. Terra-cotta jugs, jars and pots covered the walls and the open fronts, but nothing could the grinning men-of-thumbs show that would be worth the carrying off. On the hatters' boards sat the round native fur hats on little brass blocks like squat coffee-pots, with a handle sticking out underneath. The temptation to wear a fur hat under that sun was easily overcome.

Skip, reckless as ever, plunged into the barber's darksome haunt and came out unrecognizable, followed by a hairy man demanding more money. Outside the hotel was a thin youth in short trousers beating a side-drum, to the roll of which came everyone within hearing, and stood round the drummer in an attentive ring. The children, inside the circle, held each other's hands and stared hard, whilst the sheepskin-coated women and old men (most of the young ones were out with the "bands") exchanged ideas as to what it was all about. Round the crowd hovered a few infantrymen and one of the Mounted Police. The crier stopped his drumming and pulled out a long paper, from which he read, on one note, the proclamation of Martial Law. The official voice and its message seemed to bring home future possibilities to the people, and the gathering broke up talking gravely. The women took their children by the hand and led them home, showing in their own faces a feeling of insecurity.

![]()

![]()

57

Having dressed for dinner (i.e. got out a clean handkerchief) we took seats at the banquet board. Here appeared a rubber-faced linguist about five feet high, who translated the menu and announced: "I am Russian officer and editor of influenceable militairy newspaper. I wrote also important book on the Russian-Indian question - frontier of the Himalayas range, you see. It has been greatly sold." The literary warrior beamed over a pale goatee beard, and wore with conscious pride a small star hanging out of the collar of his frock coat. He would like me to push the epoch-making treatise in London, and no doubt I could get it translated. I told him I felt flattered but far from hopeful, whereat he fell upon the Oof-bird and confided to him a secret about the "Russian-Indian question" of such scorching novelty that for five fiery minutes the correspondent's professional blood boiled within him, and he doubled out to the Post-office to flash the great news across Europe.

The cosmopolitan dragoman seemed to have formed an undying attachment for us, and in honour of his adhesive qualities was surnamed "the Barnacle." It was his desire to accompany us for the rest of our journey. The price per day for the monopoly of his talents was, he knew, ridiculous by the light of their unique brilliancy, but for people he took a fancy to no sacrifice was too great. We felt we could not allow him to make it.

For Antonio, the desire to dazzle the eyes of his Sofia admirers with the new coat had overwhelmed

![]()

58

every other, and he was paid off. With the aid of seven men talking four languages, temporary rights were acquired in a local framework on wheels and three equine mummies on the sworn undertaking of their proprietor that they were capable of hauling the same. Then wearily to bed.

An outside staircase from the yard led to the bedroom, and its window looked out on to a wooden balcony occupied by a flock of geese which flapped and cackled to the banishment of all sleep. In due time from Skip's bed came a muffled voice "Say, you fellas, why don't you chase those dam ducks out o' that?"

"Your job," yawned the Oof-bird; "you two both nearer the window than I am."

"If I move," said I, "this rickety bed of mine'll fall to pieces. Go on, one of you." Here ensued a mighty tramping on the staircase as half a dozen men advanced and drove the geese shrieking into the yard. But the cure was worse than the disease, for the new flock brought chairs, sat down on the balcony, and held a heated revolutionary meeting.

We woke to find Dubnitza in the throes of market-day, and after the solemn rite of Slivovitz had been celebrated, bored our way out of the town through a close-packed mob of ponies, oxen, waggons, sheep, fruit-stalls and some hundreds of queer-looking beings. Not least of these was our new driver, a person of most villainous countenance and a wall-eye. He was swathed from arm-pits to thighs in enough red cloth to carpet

![]()

59

the aisle of The Abbey, in the folds of which was concealed everything he owned.

Past the barracks and cavalry lines, where rows of smart little horses were being vigorously groomed, and out over a stout stone bridge. About a mile down the road the trouble began.

The mummies were not "for it," a shambling run of ten yards or so being as much as they could manage at a time. Skip, mounting the box, seized the whip and whaled them with all-embracing sweeps. Twice in twenty yards the driver's fur cap spun from his head into the dust, and the long

![]()

60

lash accurately picked out the faces of the unhappy inside passengers. However, the beasts woke up a little, and under continued treatment maintained a steady average of three miles an hour as far as a little roadside inn. Here Skip with streaming face threw the broken whip in the road and rested from his labours.

The ugly jarvey stood himself a drink, which so emboldened him that he came out with the entire staff of the place and refused to go any further. He seemed nettled at having had to accept help with his team, but to show him the folly of hyper-sensitiveness about details I gave him a healthy shaking and left him on the box in a dazed frame of mind. The local people, who had at first got up a sort of indignation meeting on his behalf, now laughed it off and played the part of onlookers in the doorway. "Ugly" soon decided on "better go forward and die," and a little way up the road cut himself a faggot of stout ash staves with which he made strong play, the passengers taking reliefs of walloping by his side.

This day hills abounded, and the last hour before the midday halt was one long climb. Thick woods covered the hillsides, and sometimes the footpath led through them in the welcome cool. At the summit we sat on benches under a little plank shelter devouring hard-boiled eggs, and watching a bevy of starved hens fighting for the shells. A high wind blew across the path and whisked off the hay on which the mummies were browsing, so that "Ugly" and the landlord of the buvette were legging after

![]()

61

it all the time. Then the hay blew over the hens and the men fell over the hay and the dust rose over them all; and a kicking, swearing, clucking scrimmage raged in the highway. In the middle of it all the hen-owner trod on the horse-owner's fingers - I think on purpose - and the concentrated wickedness of all the fiends of hell twisted into "Ugly's" demon face. I saw myself in a vision driving the caravan into Samakov with the landlord's body, and the driver, trussed with his own sash, on the seat beside it. But the landlord, with the wisdom of blue funk, skipped behind our table and fussily jingled the glasses with an eye on the aggrieved haymaker, who glowered and fingered his carpet cummerbund with a wealth of "pointed" suggestion.

We let him stand out in the breeze for a while to cool off before starting on the long down-grade to Samakov. No need for the hedge-stakes here - the old barrow wagged and sagged through the dust, shoving the stiff'uns in front of it a good deal faster than they liked, and at half-past three they brought up, all sitting, at the lofty portals of the Hôtel Bulgaria.

The place was empty - not a Doctor, a Judge or a Colonel in sight. In this grave state of affairs the first thing to be done was to hire a prevotchek, otherwise interpreter. A Jew draper, bearing the honoured name of Koyoumdjiski, volunteered for this post, and proved the most useful man of his craft I ever talked through. He could reel off French, Spanish, Bulgarian, German or Turkish one

![]()

62

after the other or side by side, and unlike most of his kind did not carry on long conversations of his own with the third man. Take the average interpreter. Suppose you are interviewing some interesting but incomprehensible person, you will say to your mouthpiece "Ask him if he went to So-and-so." The average interpreter's words will flow like babbling brooks, and the words of the Interesting Person like rushing rivers. At the end of three or four minutes you will break in with " Well, what does he say?"

"He says 'No'."

But this man was a jewel of a Jew, and had the happy knack of telling you just what you wanted to know, without embroidery. We dived into the Turkish quarter, where the house-walls rise bare to little filagree-shuttered windows, high and few, and the doors in the garden walls are heavily clamped and barred. Up there were the harems of that legendary beauty which can never be proved by the shameless Giaour. Then the Jews' quarter, where you duck through a door in the street wall and come into an unexpected garden with green, shady trees and shingly paths. Then about the town by twisty streets and open places, but everywhere the same strange emptiness. After the crowded channels of Dubnitza, Samakov seemed deserted.

Even the café was held by a solitary gimlet-eyed man sipping coffee and reading a newspaper. The prevotchek nudged me and growled " Comitaji - revolutionaire." Here, then, we were

![]()

63

in touch with the insurgents - the men who were making things buzz over the border. Samakov, said the Jew, was the head-quarters of several bands, whose active members constantly slipped back to it by night to see their friends or to collect food and ammunition.

Skip looked at me - the same idea struck us both on the instant.

"What's the good of waiting for war - why not join the bands?"

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]