5. ALBANIAN SUFI POETS OF THE NINETEENTH AND TWENTIETH CENTURIES AND THEIR IMPACT ON CONTEMPORARY ALBANIAN THOUGHT

‘Since my school days, in my free time, I have read works of honest authors and scholars about the great culture of the ancient Arabs and Persians and about their influence on the development of world science and culture. Amongst other things, this has aroused in me feeling of profound respect and admiration for these people and their liberation struggle.

‘One cannot reach a judgement about the present state of a people, about their patriotic and freedom-loving spirit, about the future which awaits them, without knowing and studying their past, their cultural and spiritual history, which in the case of the Arab and Persian peoples is truly brilliant.’ (Enver Hoxha in his Reflections on the Middle East, 1958-1983, Tiranë, 1984, pages 452-3)

1. The writings of Naim Frashëri 162

2. Naim Frashëri’s poem on Skanderbeg 166

3. Naim Frashëri’s Baktāshī works 169

4. The historical background to Naim's ‘Qerbelaja’ 174

6. The epic of Fudūlī and his influences on later Albanian literature 178

7. ‘Qerbelaja’ 182

8. Twentieth-century Ṣūfī poets of Kosovo 188

9. The Baktāshī legacy in the verse of Baba ‘Alī Tomori 190

10. The neo-mysticism of Hamid Gjylbegaj 192

Muḥammad Mūfākū, after his discussion of the post-seventeenth century cultural and commercial growth of such cities as Prizren, Monastir (Bitolj) and Skopje, remarks:

Besides these schools and colleges, the tekkes of the Ṣūfī orders played a major role in establishing Islamic Arabic culture in Albanian areas. It is worth pointing out that most of the Ṣūfī orders experienced an expansion and extension to the Albanian regions, so that traditions and practices became associated with and attached to them as time passed. In fact, these Ṣūfī orders were to bind together, lastingly, the Albanians and the Arabs. We have evidence indicating that some Ṣūfī from the Arab countries came to spread their Ṣūfī orders in Albanian areas. Later, Albanians used customarily to visit the Arab countries (Egypt, Syria and Iraq) to obtain diplomas to teach (ijāzāt) in the Arabic language from the mashayikh of the Ṣūfī orders there. Of interest to us is that the Ṣūfī tekkes in the Albanian regions were to enjoy a substantial cultural activity. Every tekke housed a library rich in Arabic, Persian and Turkish manuscripts. The dervishes of the order (ṭarīqa) learned these languages and used to copy out manuscripts in these languages. Likewise there were many poets of genius in these tekkes who wrote in the Arabic language.

161

![]()

![]()

162

these tekkes were a principal source for Albanian literature as well, since within them odes and lengthy epics in verse were composed and created. [1]

1. The writings of Naim Frashëri

A lofty level of Muslim humanism is reached in the Baktāshī writings of Albania’s leading poet Naim Frashëri (1848-1900). His idealism and national feeling stirred Albanians throughout the world.

Naim was one of a brilliant family which included three brothers who were to play an especially prominent role in the movement for Albanian cultural and political independence and in the revival of the Albanian language. He was born in the beautiful southern Albanian village of Frashër (the ash tree) which his ancestors had been given as a fief from Sulṭān Mehmed II. His father began in commerce, then later became a civil servant. Like every village boy he received a Qur’ānic education and went to the important local Baktāshī tekke.

According to Baba Rexhebi and Hasluck, [2] the Frashër tekke was founded in the time of ‘Alī Pasha of Tepelenë. It once contained a score of dervishes and housed the tomb of its greatest local scholar mystic, Tahir Baba Nasībī, who died about 1835. ‘Nasībī’, ‘the fortunate one’, became his nickname after it was reported that the door of the tekke of Hacibektaș in Asia Minor opened miraculously of its own accord in order to allow him to enter. Nasībī was a gifted poet, especially in his love poems (ghazal) in Albanian, Persian and Turkish, and he was also regarded as one of the three spiritual advisers of ‘Alī Pasha. Other eminent shaikhs associated with this tekke were Alushi Babanë, Abedin Babanë and Baba Mustafanë.

Like his brothers, Naim learnt Arabic, Persian and Turkish and became familiar with several Albanian masterpieces written in Arabic script. All these were to influence him, and he always retained a deep affection for Oriental literature. In 1865, having lost his parents, he left for Ioannina, where he entered the Zozymée gymnasium, one of the best in the Balkans. He developed a working knowledge of European

1. See Muḥammad Mūfākū, al-Thaqāfa al-Albāniyya fī’-l-Abjadiyya al-Arabiyya, op. cit., p. 97-8. See likewise the author’s comments on tekkes in Tārīkh Bilghrād al-Islāmiyya, op. cit., pp. 32-3.

2. Previous writers on Frashër, including Frashëri, are conveniently summarised and listed by Nathalie Clayer, op. cit., pp. 275-8.

![]()

163

literature including Voltaire and Victor Hugo, [3] studied Greek and Latin, and read works by Homer and Virgil. Yet he also cultivated his knowledge and deep affection for Persian, and he is said to have written a 200-page volume of original Persian verse composed in the style of his favourite poets. His fluency in Persian never departed, and it is not suprising that ‘Abd al-Karīm Gulshanī, who has published and assessed his Persian verse, has dubbed Naim as the ‘Muḥammad Iqbal of the West’. [4] His first dīwan of Persian verse reflecting his personal mysticism and lyricism is Takhayyulāt, published in 1885.

In 1871 he became a civil servant. After a period in the customs department in the towns of southern Albania and at the Albanian port of Saranda, he left in 1882 for Istanbul and worked as a censor in the Ministry of Education. While there he met Albanian patriots; he joined forces with his brother Shams al-Din Sami Frashëri (1850-1904), whose own efforts in the cause of Albanian literary and linguistic revival had drawn inspiration from the common Baktāshī background which they shared. This background was the inspiration of the eldest brother Abdul Frashëri (1839-1894), the true leader of the Albanian League. In his paper Ṣabāḥ (Morning, 1875), in the paper Ṭarābulus (founded in Tripoli, Libya, 1874-5) and in his play Seydi Yahya (1876) based on a plot from Arab al-Andalus, Sami exhibited a mastery of Oriental literature and language. Later he was to complete other compositions showing a command of Arabic grammar and vocabulary. This may be read in the history of Middle Eastern peoples within his Qāmūs al-‘Ālām, and in his commentary to the Seven pre-Islamic Odes (Mu‘allaqāt). His collection of verses allegedly composed by ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib shows by its title and presentation that its author was essentially Shī‘īte in his sympathies. [5]

3. Naim, like his brothers, was to use his education and background to the full in the League of Prizren. See Stefanaq Polio, ‘La Ligue Albanaise de Prizren et sa lutte pour la liberation et l’union nationales’, Etudes Balkaniques, Sofia, 1978, 2, pp. 3-18, and Veselin Trajkov, ‘La Ligue de Prizren de 1878’, Etudes Balkaniques, 2, Sofia 1978 pp.19-32.

4. ‘Abd al-Karīm Gulshanī, Farhang-i Irān dar qalatnrau-i turkān Ash‘ār-i fārsī-yi Na‘īm Frāshirī: shā'ir va nivīsandah-i qarn-i nūzdahum-i albānī (About Persian literature written in Turkish realms, and Persian poetry of the nineteen-century Albanian author Naim Frashëri), Shiraz, 1304 AH. This is the only printed study to my knowledge of Naim’s contribution to Persian literature.

5. On Sami’s contribution in Oriental languages see the article by Dr Ḥasan Kaleshi, ‘Le rôle de Chemseddin Sami Frachery dans la formation de deux pangues litteraires Turc et Albanais’, Balcanica, 1, Belgrade, 1970, p. 197-216.

![]()

164

In 1884 Naim Frashëri published the Albanian periodical Drita (Light), and two years later produced several major compositions and literary contributions that furthered the cause of the Albanian revival. The revival centred on the comprehensive struggle for independence or autonomy enshrined in the League of Prizren (in Kosovo) founded in June 1872 and led by his brother Abdul. A number of these works were planned as historical, geographical and science textbooks for use in schools. Others were collections of Naim’s own verse in Albanian, such as ‘Herds and Pastures’ (Bagëti e Bujqësi) and ‘Flowers of Summer’ (Lulet e verës) of 1890. The latter especially displays not only his deep love for Albania, but his seemingly ‘pantheistic’ or ‘monistic’ philosophy.

It is in these poems that a Ṣūfī mysticism is blended with a nature mysticism centred on Naim’s homeland. The defiant peaks of the Albanian mountains express the will of the people; they point upwards to the skies and ultimately to Heaven and Divinity. The woods, streams and valleys in his verses express his idea of the beauty of nature and the bliss of freedom that could be enjoyed by those who lived there among his countrymen. As Koço Bihiku remarks, ‘The pantheism of life in the bosom of nature no doubt stems from the illuminist convictions of the poet.’ [6]

In other poems God is identified with man himself, as well as with that divinely created environment that manifests His nature. Man may know the nature of divinity within the ‘ground of his being’, also within his body; and especially in the beauty of his own visage. Here Naim expresses those notions that were the ancient heritage of esoteric Islam (al-bāṭiniyya), but were to be forcibly re-expressed by the Ismā‘īlī and Ṣūfī Shihāb al-Din b. Bahā’ al-Dīn Faḍlallāh al-Ḥurūfī of Astarābād (born 1339/40), who was executed by Timur’s son Mīrān Shāh in Shirvān in the Caucasus in 1394. The nature of divinity in man was central to Faḍallāh’s massive Persian and Arabic Jāqidān-i-Kabīr and his other works. They were later displayed afresh in the verses of Qāsim al-Anwār (d. 1432), Nasīmī of Baghdād, or of Tabriz (martyred in 820/1417-18 possibly 807/1404 in Aleppo) by Rafī‘ī, or by Rūḥī of Iraq, and by a great number of Baktāshī and janissary poets (for example Ḥabībī and Rușenī). These verses were read and memorised and imitated in Kosovo and Albania (Plate 9).

The features of man are the mirror of divinity. In Faḍlallāh’s Jāwidān, which was studied and commented upon in Krujë, Ādam is the

6. Koço Bihiku, A History of Albanian Literature, Tiranë, 1980, p. 43.

![]()

165

prototype link between God and man (wholly opposite to the dualistic beliefs of the Bogomils). Ādam, in his corporeal form, was united to the Ka‘ba in Mecca. He was also a part of the physical world that was his home and his environment. To cite the Jāwidān, ‘God Almighty created the head of Ādam and his forehead from the soil of the Ka‘ba, his chest and his back from Jerusalem, his thighs from the Yemen, his legs from Egypt, his feet from the Ḥijāz, his right hand from the Muslim East and his left from the Muslim West’. [7] This sentiment may be observed in Naim’s verse. For him Albania’s soil is part of such a divine scheme for a particular people, and it is a part of the homeland. Stuart E. Mann has translated such verses in his Albanian Literature: [8]

When God first sought to show His face

He made mankind His dwelling place.

A man that knows his inward mind

Knows what God is. It is mankind. [9]

In this poem, as in several others, influences from Ibn ‘Arabī, Rūmī and from Nasīmī are apparent. Equally apparent is a non-sectarian, interfaith appeal that is not only a personal characteristic of this poet and his fellow nationalists, but is also typically gnostic, and heterodox.

Perhaps more than any other Anatolian sect, the Bektashis interpreted Scripture allegorically and effaced all sharp contrasts and vicissitudes, preaching as they did, their favourite theme of the unity of existence (waḥdat al-wujūd) and the identity of the external and the internal world. To the agonised man who had known decades of war, slavery, abduction, and all kinds of violence, the mystic offered hope and comfort, an escape from harsh reality. Thus, the Mevlana Jelaleddin Rūmī was regarded as a saintly figure by both Moslems and Christians, and his contemporary Haji Bektash Veli, the eponymous saint of the Bektashi order, could likewise attract worshippers from both religions.

7. This passage and others regarding Ādam’s head and body being materially linked to the substance of the Ka‘ba and the holy lands of Islam in East and West, proceeding from Mecca and Jerusalem are included in the opening sections of the copy of Faḍlallāh’s Jāwidān, Cambridge University Library copy (E. 1.9.27). See E.G. Browne, A Catalogue of the Persian Manuscripts of the Library of the University of Cambridge, pp. 69—86.

8. Stuart E. Mann, Albanian Literature: An outline oj Prose, Poetry and Drama, London, 1955, pp. 40 and 41. Naim’s poems were not unique in this but the quality of his verse combined with his other nationalist and educational activities placed him at the head of the avant garde.

9. These verses echo the Ḥurūfī-inspired verses of Nasīmī: ‘O thou spirit that is enshrined in physical form, Your face is that of sacred scripture, exalted be its state, Allāh is most great.’

![]()

166

Tolerance in all directions, common places of worship for Christians and Moslems, stories of mircales for the followers of Christ, and Mohammed indiscriminately, saints venerated by both peoples, and a persistent, if vague, identification of Ali with Christ and Haji Bektash with St Charalampos — these are some of the factors to which the Bektashis owe their success. [10]

The League of Prizren was eventually suppressed. The Baktāshī tekkes in the south of Albania suffered severely from Ottoman repression, the vandalism of Greek and Serbian irregulars and much Sunnite hostility. Yet the triumph attained by Naim and Sami Frashëri in founding an Albanian school in Korça, Sami’s invention of an Albanian alphabet, the broad non-sectarian message of the cause they promoted, with its ethical idealism, its stress on the unbreakability of a promise given (well manifested in Sami’s noteworthy drama in Turkish, Besa yahod abd-u-vefa, Istanbul, 1876) and the close cooperation with Hodja Ḥasan Tahsin, Jani Vreto, Postenani, Pashko Vasa, Gjirokastriti and many other like-minded men of letters — these efforts were not wasted. They are praised for their writings in Albania today. Some of their works that were published are regarded as representative masterpieces of Albanian writing that should feature in any serious history of Albanian literature, and indeed could hardly be omitted from it.

2. Naim Frashëri’s poem on Skanderbeg

Apart from his lyrics, Naim Frashëri’s most noted composition is his epic on the life of Gjerg Kastrioti, written in 1898 and held to be his most famous and greatest work. [11] Historia e Skenderbeut transcends religious boundaries. By the time Naim wrote his epic, Albania’s hero of the late Middle Ages and Krujë, his capital, had acquired a denominational significance for the Albanian Baktāshīs. [12] According to Stuart Mann, ‘Of all his works, Naim considered the Skanderbey epic to be his best.

10. Cited in G.G. Arnakis, ‘Futuwwa traditions in the Ottoman Empire; Ahis, Bektashi dervishes and craftsmen, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, XII, 1953, p. 243. See also papers presented to Simpoziumi per Skenderbeun, 9-12 May, 1968, Prishtinë: Institut Albanologjik 1969.

11. There are a number of editions in Albanian of Naim’s masterpiece. On the topic, as literature, see the articles listed by Robert Elsie. Dictionary of Albanian Literature, p. 126, under ‘Scanderbeg’.

12. On the history of Krujë tekke and the Baktāshī practice there see Nathalie Clayer, op. cit., pp. 325-39.

![]()

167

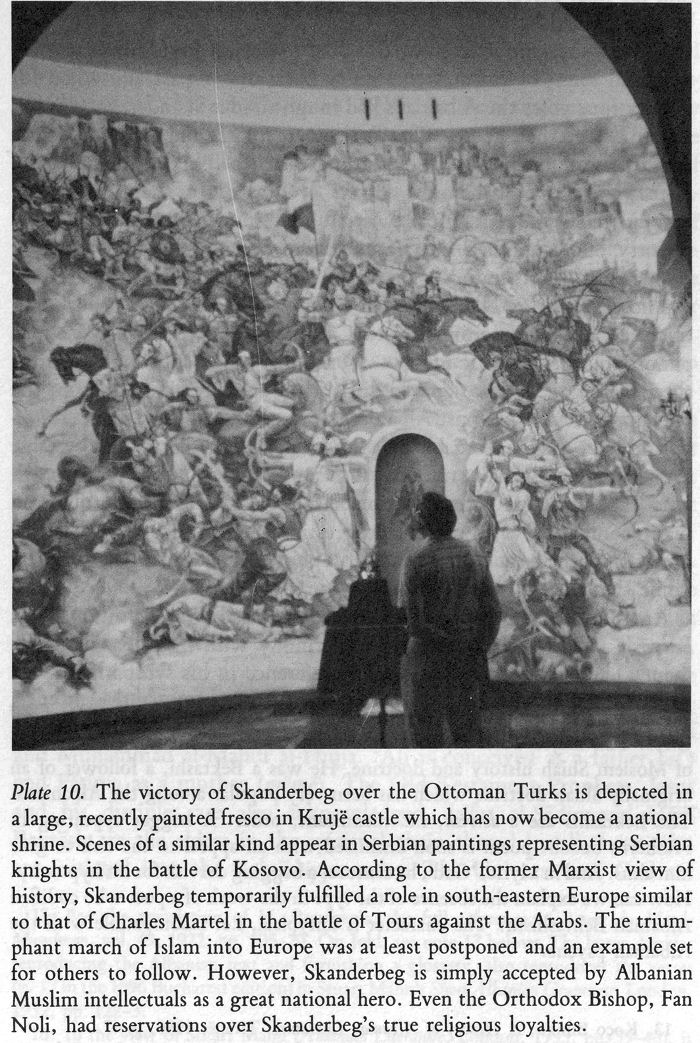

Plate 10. The victory of Skanderbeg over the Ottoman Turks is depicted in a large, recently painted fresco in Krujë castle which has now become a national shrine. Scenes of a similar kind appear in Serbian paintings representing Serbian knights in the battle of Kosovo. According to the former Marxist view of history, Skanderbeg temporarily fulfilled a role in south-eastern Europe similar to that of Charles Martel in the battle of Tours against the Arabs. The triumphant march of Islam into Europe was at least postponed and an example set for others to follow. However, Skanderbeg is simply accepted by Albanian Muslim intellectuals as a great national hero. Even the Orthodox Bishop, Fan Noli, had reservations over Skanderbeg’s true religious loyalties.

![]()

168

In his last moments he bade his nephew Midhat read it out to him for final correction, though the final version seems never to have been published.’

It was a supreme attempt by this poet to project his idealism, patriotism and sense of cultural continuity back into a past age when for twenty-four years the Albanians had fought under Skanderbeg’s leadership to defend their liberty. The Turks were not the only enemy; Venice and others are included too. According to Koço Bihiku, ‘the History of Skanderbeg’ is one of the most popular productions of the period of the national renaissance. Its most successful and inspired parts, such as the re-entry of Skanderbeg into Krujë, were committed to memory by the patriots, ‘who found embodied in it their most sacred desires’. [13]

Those works of Naim Frashëri which combine Ṣūfīsm (including traces of idealistic, as opposed to Cabalistic, Ḥurūfīsm) and Western philosophical and poetic ideas — works that are openly apologetic for the Baktāshiyya — have proved difficult to appraise. Indeed, from the prevailing view in Marxist Albania, they had to be dismissed as a cul-de- sac and were only redeemable by the nationalist heartbeat still detectable in the content. Even so, much of that content was out of keeping with what was viewed as positive national aspirations, and without question was incompatible with current progressive ideas and ideology. Significantly, a work about Naim contained a photograph of its title and cover, while the content was rigorously ignored.

Arshi Pipa however points out that on a broad level Naim Frashëri’s Baktāshī beliefs are always in basic harmony with his Albanian sentiment. These, if need be, may take preference in his sympathies.

The first important poem by an Albanian author is Naim Frashëri’s Herd and Crops. This major Tosk exponent of Albanian nationalism was also the poet of Moslem Shiah history and doctrine. He was a Bektashi, a follower of an originally Shiah doctrine which has been very popular among the Albanians. The Bektashis are a dervish, i.e. mendicant, order. A beggar appearing in Frashëri’s bucolic poem is soon dismissed with an appeal to the rich to give him alms. And in a lyric, ‘God’, he censures a begging dervish for his hyprocisy. How can we explain the absence of the type in the work of a poet who codified Albanian Bektashism? The character is untypical, i.e. incompatible with the Albanian psyche. [14]

13. Koço Bihiku, A History of Albanian Literature, Tirane, 1980, p. 47.

14. Arshi Pipa, ‘Typology and Periodization of Albanian Literature’, Serta Balcanica- Orientalia Monacensia in Honorem Rudolphi Trofenik Septuagenarii, 1981, Munich, pp. 248-9.

![]()

169

3. Naim Frashëri’s Baktāshī works

There are, however, two works in which Naim’s denominational loyalties are made abundantly plain. The first of these, Fletore e Bektashinjet (Bucharest, 1896, and Salonika, 1910), has been translated variously as ‘Baktāshī pages’ or ‘leaves’, and more closely as the ‘notebook’ of the Baktāshīs. [15] The book is a tract, some thirty pages of statement of belief, followed by ten poems by Naim on faith in God, the deity immanent in nature and the tragedy that befell ‘Alī’s descendants (Vjersh të Lartë). Birge was somewhat sceptical of its purpose and its true authorship and remarked: ‘The treatise translated by Hasluck needs to be treated with some care for it is quite obviously something prepared for those outside the order.’ [16]

Besides Hasluck’s English version, via Greek, it was translated into French as far back as 1898 by Faik Konitsa, himself a Baktāshī. A complete French translation, without the poems, by H. Bourgeois was published in the Revue du Monde Musulman in 1922. However, the most scholarly translation, this time accompanied by the full Albanian text and with very detailed notes on its language, was published by Norbert Jokl in Balkan Archiv in 1926. [17]

The work is a discourse about the characteristic beliefs of the sect. It opens with a statement of belief in God, in Muḥammad-‘Alī, the dual form of the ‘Alīd cult, then Khadīja the Prophet’s first wife, then Fāṭima his daughter, and the two sons of ‘Alī, Ḥasan and Ḥusayn. Next come the twelve Imāms — ‘Alī, Ḥasan, Ḥusayn, Zayn al- ‘Ābidīn, Muḥammad al-Bāqir, Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq, Mūsā al-Kāẓim, ‘Alī al- Riḍā, Muḥammad al-Taqī, ‘Alī al-Naqī, al-Ḥasan al-‘Askarī al-Zakī and Muḥammad al-Mahdī al-Ḥujja. ‘Alī is conceived as a father (at’) and Fāṭima as a mother (mëmë). The Old Testament Prophets, Jesus and his disciples are also acknowledged. Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq and Ḥājjī Baktāsh are the elders in the spiritual chain shared by all those who are initiated into the Baktāshiyya order. The Universe and God are indivisible,

15. For the translation of H. Bourgeois, the full reference is Revue du Monde Musulman, vol. 49, 1922, pp. 105-20. On Jokl, see note 17 below. The latter, besides reproducing the Albanian text and furnishing a glossary, also reproduces the verses (p. 17 in the 1896 Bucharest edition) in Stuart Mann’s Short Albanian Grammar, London, 1932, pp. 122-3.

16. In the view of Stuart Mann (Albanian Literature, London, 1955, pp. 39-40), it is a collection of poems and its message was aimed at attracting ‘Albanians to a liberal faith acceptable to Christians and Moslems alike’.

17. N. Jokl’s translation is to be read in Balkan Archiv, 11, Leipzig, 1926 pp. 226-56.

![]()

170

or at least completely interlocked or fused. After death man is transformed (perhaps reincarnated) in his body, yet he is always near to God — although God is hidden, — in a relationship like father and son. Monogomy is commended and divorce deemed a sad misfortune. Charity and love transcend religious differences. Great emphasis is placed on helping ‘the poor’. This latter also denotes the ‘faqīr', a novice in the order, whose role and status within the structured organisation of that order are given considerable prominence.

Markedly absent are references to the five pillars of Islam that are fundamental to Sunnite belief. Instead much of the prayer and almost all the fasting are centred around the massacre at Karbalā in Iraq, where ‘Alī’s son Ḥusayn met his death. This is introduced in two places. To cite Hasluck’s translation:

For a fast they have the mourning they keep for the passion of Kerbala, the first ten days of the month which is called Moharrem (al-Muḥarram).

In these days some do not drink water, but this is excessive, since on the evening of the ninth day the warfare ceased, and it was not till the tenth after midday that the Imam Husain fell with his men, and then only they were without water.

For this reason the fast is kept for ten days, but abstention from water is practised only from the evening of the ninth until the afternoon of the tenth.

But let whoso will abstain also from water while he fasts. This shows the love the Bektashi bear to all the Saints [18].

This same emphasis on the events at Karbalā is taken up again later:

The Bektashi keep for a holy-day Bairam [bajram], the first day of the month which is called Sheval [Shawwāl]. Their second feast is on the first ten days of the month called Dilhije [dhilhixe], here the text actually reads ‘on the tenth day itself of Dhū’l-Ḥijja, ‘Īd al-Aḍḥā [celebrated at the height of the annual pilgrimage by all Muslims] the New Day (which is called Nevruz) on the tenth of March and the eleventh of the month called Moharrem. During the ten days of the Passion they read the Passions of the Imams.

According to Muḥammad Mūfākū the festival of Nevruz among the Albanian Baktāshīs is held on March 21, celebrating the birthday of the Imām ‘Alī. The ten days of Muḥarram are those during which the events in Karbalā are recalled, in conjunction with other sad events involving sacrifice and relating to famous prophets and to imāms.

18. F.W. Hasluck, Christianity and Islam under the Sultans, vol. II, Oxford, 1929, pp. 558-9.

![]()

171

The ten days are divided up in the following manner. On the first night the sufferings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Joseph, Moses and Jesus are commemorated. On the second night the prophet is Muḥammad. The third night is devoted to the Imām ‘Alī, who fell ‘as a martyr in the path of justice’. On the fourth night the poisoning of Imām Ḥasan is the central subject of the lament. The fifth night is devoted to the life history of the Imām Ḥusayn. On the sixth night the subject is the hijra of the Imām Ḥusayn from Medina to Mecca. The seventh night is devoted to the history of Muslim b. ‘Aqīl, who was sent as an envoy to Kūfa by the Imām and who died a martyr there. The eighth night is concerned with the journey of the Imām to Kūfa. The ninth night tells of the arrival of the Imām Ḥusayn in the suburbs of Kūfa where he received a letter from Muslim b. ‘Aqīl who advised him to advance no further. The tenth, the final night, is about the battle of Karbalā and the death of the Imām Ḥusayn.

After the mourning the sweetmeat called Āshūrā’ (hashnreja) is prepared in the tekkes. This sweetmeat is now commonly eaten by Albanians many of whom are not members of the Baktāshiyya. After hymns, prayers and lamentations, sung or recited in recollection of the sufferings of the Imām Ḥusayn, the food is eaten, stories of the battle of Karbalā are re-told, followed by odes by the poets of the Frashëri family, especially those by Dalip and Shahin Frashëri. Their odes are recited aloud, although these latter are, in part, recited during the whole period of the ten days in Muḥarram. [19]

It is characteristic of Albanian Baktāshīs that these elements in the ‘Āshūrā’ that join them together with members of other denominations and faiths should be stressed. This same feeling is revealed, for example, in the following explanation of the feast’s meaning and significance by the Albanian Baktāshī, Sirrī Bābā, who wrote these words with a special reference to the Cairene tekke where he lived, and the Egyptian society with which he mixed. [20]

The day of the ‘Āshūrā’

The day of ‘Āshūrā’ is an honoured and respected day among all the people of the books of heavenly revelation, Muslims, Christians and Jews. On that day Allāh Almighty honoured, in varied miraculous acts, a goodly number of His Prophets. In ‘Āshūrā’, Allāh Almighty accepted the repentence of Ādam and David, upon whom be peace. In it, Allāh raised Enoch (Idrīs) to a lofy place in Heaven. In it, the ship and ark of Noah, peace be upon him, were fixed firmly

19. Muḥammad Mūfākū’s article on the Baktāshiyya in al-‘Arabī, no. 220, op. cit., pp. 66-8; see also Nathalie Clayer, op. cit., pp. 85-7.

20. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, al Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, pp. 49-51.

![]()

172

on Mount al-Jūdī after the end of the flood, and [the earth’s] inundation. In it, Abraham was born, peace be upon him. Right guidance was bestowed upon him in that day. In ‘Āshūrā’, Allāh Almighy saved him from the fire of Nimrod. In it, Allāh returned the sight of Jacob, may His peace be upon him. In it, Allāh brought forth Joseph, peace be upon him, from the cistern. In ‘Āshūrā’, Allāh took away the suffering and affliction of Job, peace be upon him. In it, Moses, upon whom be peace, had secret and spiritual communion with his Lord. In it, He aided him against Pharaoh, his foe, where he split the sea in twain for him so that Pharaoh and his soldiers were drowned. In ‘Āshūrā’, King Solomon, peace be upon him, was granted a kingship that was unattained by any ruler who came after him. In it, Allāh rescued Jonah, peace be upon him, from trial and tribulation and brought him forth from the belly of the whale. In it, our Lord Jesus was born, peace be upon him, and in it he was raised to Heaven. In it, our lord, Muḥammad, the blessing and peace of Allāh be upon him, was pardoned from all his sins that he had committed. In ‘Āshūrā’, our lord, the Imām, al-Ḥusayn, the son of ‘Alī, the satisfaction of Allāh be upon them both, was slain at the place named, al-Ṭaff [beside the Euphrates], at Karbalā, in Iraq, he and seventy men from the household of the Messenger of Allāh.

It is reported in the books of tafsīr that the day of the ‘breaking of the dam of the Cairo canal’ (al-zīna), [21] which Allāh Almighty made mention of in sūrat Ṭāhā, where He said, ‘Your appointed time is the day of ornature’ (al-zīna), is the day of ‘Āshūrā’. It is also said in the book, al-Durr al-manthūr fī’l-tafsīr bi’l-ma’thūr by Jalāl al-Dih al-Suyūṭī, that the Messenger of Allāh, His blessing and peace be upon him, said, ‘Whosoever fasts on the day of the “adornment” will make up for those fasts that he has missed within that year, and whosoever gives alms on that day will redeem for the almsgiving that he has missed during that year, that is to say, on the day of “Āshūrā”.' In another haḍīth it is said, ‘Whosoever is open-handed towards his family and his children on the day of “Āshūrā” then Allāh will be generous towards him, likewise, for the rest of the year’.

On this blessed day, food that is made from grains and cereals is cooked. The reason for that is that when the ship and ark of Noah, peace be upon him, rested firmly on Mount al-Jūdī on the day of ‘Āshūrā, Noah, peace be upon him, said to those who were with him in the ark, ‘Gather together what provisions you have left.’

21. E.W. Lane (in his Lexicon, vol. 1, Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 1984, p. 1280) explains that yawm al-zīna (as it appears in Sūrat Ṭāhā, verse 61) is taken to mean ‘the day of the bursting [of the dam a little within the entrance] of the canal of Miṣr (Cairo). The dam is broken when the Nile has attained the height of sixteen cubits or more. This day is said to be meant in Koran XX, 61.’ A J. Arberry (The Koran Interpreted, vol. 1, London, 1955) renders the verse as ‘Your tryst shall be upon the Feast Day’ (p. 342). The day of ‘zīna’ is otherwise translated as the day of adorned apparel.

![]()

173

This one came with a handful of beans, another brought with him a handful of lentils, another came with a handful of rice and barley and millet and wheat. Then Noah, peace be upon him, said ‘Cook it all’ and they did so. And all of them ate of it until they were satisfied. It was the first repast that was cooked on the face of the earth. On account o£that, the Muslims have adopted the cereal food that is given the name of ‘Āshūrā’.

The lords of the Baktāshiyya celebrate the memory of the martyrdom of al-Ḥusayn which took place on such a day as this in the year 61/683. They cook the ‘Āshūrā’ and distribute it as charity to the poor and needy who make for the tekke, arriving there from every direction. The Shaykh of the tekke [in Cairo] invites men of the royal palace and ministers and scholars and men of state and the ambassadors of states and leading men of the capital to partake of the food of the ‘Āshūrā’ at the tables that are set up in the gardens of the tekke. Then the Qur’ān is read and prayers are recited and the following formal prayers:

In the name of Allāh, the Compassionate, the Merciful.

Peace be upon you, O father of ‘Abdallāh, peace be upon you, O son of the Messenger of Allāh, peace be upon you, O son of the Commander of the Faithful. Peace be upon you, O lord of the trustees. Peace be upon you, O son of Fāṭima al-Zahrā, the mistress of the women of the world. Peace be upon you, for ever, as long as the day and the night remain. The misfortune that came upon you was of major and awful concern both for us and for the entire Muslim people. Your misfortune was a mighty event in the Heavens among all those in the realm of the Heavens. O Allāh, make me, with you, to be one who is acceptable with al-Ḥusayn in this world and the next. I ask Allāh, who has shown me an honour in having a knowledge of you and a knowledge of those close friends of yours, and who has blessed me in disavowing your enemies, that He will make me to be with you in this world and the next and that my foot of truth will be firmly fixed with you in this world and the next. I beseech Him, the Almighty, that He will make me reach the praiseworthy rank that is yours in the presence of Allāh. O Allāh, make my life-time to be that of Muḥammad and the family of Muḥammad, and my decease to be that of Muḥammad and the family of Muḥammad. O Allāh, give me the blessing of the mediation of al-Ḥusayn on the day of the attainment. Make us firm-footed in truth with Thee, along with al-Ḥusayn and with the companions of al-Ḥusayn who spilled their life-blood for the sake of al-Ḥusayn. Gather us together with al-Ḥusayn, O most gracious of the gracious. Peace be upon you, O Messenger of Allāh, peace be upon you, O Commander of the Faithful, peace be upon you, O Fāṭima al-Zahrā, peace be upon you, O Khadīja the greatest, peace be upon you, O Ḥasan, the selected, peace be upon you, O Ḥusayn the approved, peace be upon you, O martyr of Karbalī, peace be upon your grandfather and your father, your mother and your brother and upon your

![]()

174

family and household and your clients and your party and those who love you. The mercy of Allāh and His blessings and peace be upon those who were sent as messengers, and Thine angels who are brought close to Thy presence, and the saints of Allāh Almighty every one. Praise be to Allāh, the Lord of the Worlds.

Aside from its religious affirmation of faith, Naim’s work on his sect is of relatively little literary interest. It has to be seen as having a relationship with another of Naim’s last and most monumental works, his second great epic poem Qerbelaja. Passages in verse are found in both works. However, in the brief statement of Baktāshiyya belief that Fletore e Bektashinjet contains, there is enough evidence to show that national sentiment was never far from Naim’s mind. In this juxtaposition lies its originality, as Stavro Skendi [*] explains:

In the Notebook of the Bektashis (1896), Frashëri, who was himself a Bektashi, manifests such a great desire for the purity of language that he translated even the established Oriental terms of the order. Nor does he mention the mother monastery of the Bektashis, Pir-evi, in Asia Minor. As explained by his nephew, Midhat Frashëri: ‘He [Naim] tried hard to convey to the Bektashis that we need a Dede-baba [supreme abbot] from whom the babas [abbots] should receive their consecration and not go to Pir-evi [for that purpose]; and this Dede-baba should be recognised by all the babas of Albania as their spiritual head.’ The fact the Pir-evi was ignored by Naim Frashëri seems to betray his intention of creating an independent Bektashi order for Albania.

4. The historical background to Naim's ‘Qerbelaja’

Qerbelaja is Naim’s most direct confession of inspiration that the Albanians derive from the cultural, historical and religious legacy of Iraq and Iran.

The presence of the Baktāshiyya in Iraq’s holy cities, especially in the Shī‘īte shrines where resthouses for pilgrims were needed, is reported by Hasluck. [22] He mentions that the heterodox Kizilbaș of Asia Minor made the pilgrimage to Baghdād, Kūfa and Karbalā and that the Baktāshīs showed a special respect for the tomb of Gulgul Bābā in Baghdād,

*. See Stavro Skendi, The Albanian National Awakening, 1878-1912, Princeton University Press, 1967, pp. 123-4.

22. Hasluck, op. cit., p. 514. His comment on Damascus is hardly correct, even though at the time dervishes were held in a poor opinion. Hasluck also refers to a tekke in Kurdistan and one at Shamakhi in Shirvan, Azerbaijan, north-west of Baku. Azeri verse is influenced by Ḥurūfīsm.

![]()

175

the tombs of the Imāms Mūsā and Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq in Kāẓimayn and for Karbalā, Najaf and Sāmarrā’. Albanian interests were well served in Iraq, especially during the governorship of Āyās Pasha, who was of Albanian origin. His polite manners, lettered tastes and manly if ruthless virtues were esteemed. He was brother to Sinān Pasha, conqueror of the Yemen, and became governor of Baghdād in 952/1546 after the dismissal of Sūlāq Farhād Pasha.

Karbalā, sacred to the Baktāshiyya, as well as to all Shī‘ītes and indeed to a large selection of the Muslim world, is associated with events that followed the death of the Umayyad Caliph, Mu‘āwiya, in 680 AD. Ḥusayn, second son of ‘Ali, together with other members of the Arab aristocracy, had refused to take the oath of allegiance to Yazīd, Mu‘āwiya’s son. Invited to leave Mecca and take up residence in Kūfa, where he had support, he was intercepted by patrols sent out by ‘Ubaydallāh b. Ziyād, Yazīd’s governor. Ḥusayn refused to turn back towards Mecca and was therefore escorted as far as Karbalā some sixty miles south-west of modern Baghdād. There he was surrounded and, deprived of further supplies of water, confidently expected to surrender since his allies in Kūfa proved ineffectual. On the 10th of Muḥarram, October 10, 680, ‘Umar b. Sa‘d, the commander under Yazīd’s authority, called on him to surrender. Once again Ḥusayn refused. He was killed and his head was sent to the Caliph — who was filled with genuine remorse. This event was to herald a series of ‘Alīd rebellions and messianic movements. In 687 al-Mukhtār the Thaqafīte appeared in Iraq as a self-proclaimed ‘messenger’ for one of ‘Alī’s younger sons, Muḥammad b. al-Ḥanafiyya. Claiming to be inspired by Gabriel, al-Mukhtār preached — through a curious, allegedly revealed scripture based on the style of the Qur’ān itself — that the arrival of the Mahdī was at hand. After some striking successes, he won much of Iraq, although he could not win the Arabs of Kūfa. He was killed having fulfilled only in part the sacred duty to avenge the martyrs of Karbalā. It was left to Abū Muslim and others to take up this task.

The happenings in Karbalā and their aftermath, were to appear in poems by the fourteenth-century Anatolian epic poet, Sa‘dī. His Karbalā epic is divided into ten parts, corresponding to the ten days of mourning during Muḥarram. In the first seance, Ḥusayn is shown in Mecca. Invited to go to Kūfa, he leaves notwithstanding the counsel of his friends and well-wishers to remain. In the second seance, his companion, Muslim b. Aqīl, whom he had sent to Kūfa ahead of him, is slain. The thirst suffered by the martyrs now begins. The third séance shows the journey of Ḥusayn to Karbalā. In the fourth he digs a defence ditch

![]()

176

and pitches his camp. The fifth describes the death of Qāsim, son of a brother of ‘Alī, who had married the daughter of Ḥusayn. Seances six and seven are concerned with the deaths of Ḥusayn’s two sons, ‘Alī Akbar and ‘Alī Aṣghar, followed by Ḥusayn’s own death. The last three séances tell of the miracles of Ḥusayn’s head as it is carried to Yazīd. The young Imām, Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, is spared and bravely predicts the vengeance in the future for the slain in Karbalā.

5. The tekkes of Iraq

Karbalā had its own Baktāshī tekke (of the Dadawāt — likewise Baghdād, at Najaf, Kirkuk takiyyat Mardan Ali, and other cities). These were to play an important role as centres for religious and cultural activities. They provided hostels for pilgrims and became centres of meditation and literary activity, some of which, especially the verse, was to be coloured by Ḥurufī imagery and thought. Several of the Babas in Albania and Thessaly were either Iraqis or were resident or were trained in Iraq. For example, among the Babas of the ‘mother tekke’ of Durballi Sulṭān in Thessaly, a number of them from the Arab world, at least eight between 1522 and 1753 had come there from Iraq: Bābā Mūsā of Baghdād (1522-53), Kasim (Qāsim) Bābā of Baghdād (1627-43), Emin (Amīn) Bābā from Karbalā (1643-55), Zejnel Abidin (Zayn al-‘Ābidīn) Bābā from Baṣra (1660-3), Sejjid Maksud (Maqṣūd) Bābā from Baghdād (1694-1713), Ṣāliḥ ‘Alī Bābā from Baghdād (1713-25), Manṣūr Bābā from Baṣra (1725-36) and Selim (Salīm) Bābā from Baghdād (1744-53).

Ḥāwī al-Ṭu‘ma in his book Turāth Karbalā, [23] writes:

The Karbalā tekke of the Baktāshiyya order

This is located towards the eastern side at the entrance to the southerly gate of the shrine of (the Imām) Ḥusayn, and in proximity to the tomb of Ayat Allāh al-Shīrāzī, the leader of the Iraqi revolution (in 1920). This was once the haunt of Pashas and Mushīrs who came from Istanbul at one time or at another. So too came the poets of Karbalā. Among them I single out for special mention Shaykh Mahdī al-Khāmūsh (namely Abū Ziyāra, Shaykh Mahdī b. ‘Abūd al-Ḥā‘irī, made famous by the name of al-Khāmūsh), who was a preacher and poet and who was favourably attested to by the congregations of Karbalā. He died in 1332/1914/15. He used to make the tekke his goal in the age of Sayyid Taqiyy al-Darwīsh,

23. Salmān Ḥāwī al-Ṭu‘ma, Turāth Karbalā, 1st printing, 1383/1964, al-Najaf, p. 229-30 where the Baktāshī tekke is specifically described.

![]()

177

the head of the family of Āl al-Dadah who still survive, and also the two poets Shaykh Jum‘a b. al-Ḥā‘irī (Shaykh Jum‘a b. Ḥamza b. al-Ḥajj Muḥsin b. Muḥammad ‘Alī b. Qāsim b. Muḥammad ‘Alī b. Qāsim, who died in 1350/1931/32, one of the poets and preachers of Karbalā), and (secondly) Shaykh Muhsin Abū’l Ḥabb al-Ṣaghīr. All of that took place during the age of the late Sayyid ‘Abd al-Ḥusayn al-Dadah. It is well known that those conversations and evening seances of a literary nature occupied the first place in the meetings of the tekke of the Baktāshiyya order.

In a further note the author adds that this tekke was about 200 years old, that it had a dome covered with Qāshānī tiles and supported by a marble column. Within its precincts lay buried the poet Fuḍūlī (Fuẓūlī) al-Baghdadī, together with his son. The Āl al-Dadah were an ‘Alīd family, descended from the Imām ‘Alī b. Mūsā al-Riḍā. The family became custodians of the tekke in the nineteenth century, first of all Sayyid Aḥmad b. Mūsā Ṣādiq, then his son Muḥammad Taqiyy al-Darwīsh (d. 1314/1896/7) took over the custody of the shrine of al-Ḥusayn from his father. ‘Abbās, one of his sons, died in 1316/1898/9. The three offspring and the family farmed ‘dervish’ lands outside Karbalā. These sons were ‘Abd al-Ḥusayn (who was interned in Ḥilla in 1920 and died in 1948), Ja‘far and Muḥammad. What is left of the property of the tekke was looked after by an Albanian, Meḥmed ‘Alī.

Ḥusayn ‘Alī Maḥfūẓ writes that in his old age al-Fuḍūlī became a recluse. He spent much of his time attending to the shrine of al-Ḥusayn in Karbalā, a city he called the Elixir of Kingdoms. It is said that he took on the responsibility of lighting the lamps at the Imām’s tomb and died of the plague when it ravaged the city. He was buried in the cemetery of the Āl al-Dadah family in that part of the tekke of the Baktāshiyya to the south of the open court of the Raw da of the Imām Ḥusayn facing Bāb al-Qibla. His son Faẓl b. Fuḍūlī, who would appear to have died after 1014/1605/6, was also lettered, a highly talented writer of verse in Arabic, Persian and Turkish. He wrote histories on noted religious buildings and refutation of the sect of Kizilbașiyya (Alevi).

Spencer Trimingham maintains that Bālim Sulṭān (d. 1516) was the first leader of a true Baktāshī organisation, and that it was during the sixteenth century (according to Baba Rexhebi [24]) that the first Karbalā Dede, Abdyl Mymin Dedeja, was put in charge of the Karbalā tekke,

24. Baba Rexhebi, Misticizma Islame dhe Bektashizma, New York, 1970, op. cit., p. 203-8.

![]()

178

which had been established there by Bālim Sulṭān himself. A direct link may be traced between Abdyl Mymin Dedeja, the great poet of Azerbaijan al-Fuḍūlī, and the Baktāshī Albanian poets of the nineteenth century who drew spiritual and patriotic inspiration from the tragedy of the Imām Ḥusayn.

6. The epic of Fulḍulī and his influence on later Albanian literature

The Azerbaijānī poet, Muḥammad b. Sulaymān al-Fuḍūlī al-Baghdādī (died 963/1555/6 or 970/1562/3), who was the greatest of poets in Turkish as well as a master in Persian and Arabic, is best known for his love poetry, which displays pathos and tender yet passionate feelings. His romance Laylā and Majnūn (composed in 963/1556), has been described as the most beautiful mesnevi in the Turkish language. But he is also noted for his poem Ḥadīqat al-Su‘adā’ (the garden of the blissful) on the martyrdom of the Imām Ḥusayn.

This work is partly a Turkish translation of the Rawḍat al-Shuhadā’ by the Persian Ḥusayn Wā‘iẓ al-Kāshifī, a resident of Herat (died 910/1505), a major writer, a scholar, an astrologer and a preacher, and it also has parts derived from the Kitāb al-Malhūf by Sayyid Riḍā’ l-Dīn b. Ṭāwūs. This contribution in prose to Shī‘īte literature was specifically written to be read, recited and pondered upon during ‘Āshūrā. It is the source of other compositions devoted to the theme of lamentation, not only for the death of the Imām Ḥusayn but also for the afflictions of the prophets, the martyrs and sufferers in every time and place. The composition is divided into ten chapters, to which is appended a conclusion and a colophon:

1. The manifestation of support by the prophets for Muḥammad.

2. The rudeness and persecution towards Muḥammad by the Quraysh, and the martyrdom of Ḥamza and Ja‘far al-Ṭayyār.

3. The death of the Prophet Muḥammad.

4. The life of Fāṭima.

5. The life of ‘Alī al-Murtaḍā.

6. The virtues of the Imām Ḥasan.

7. The miracles of the Imām Ḥusayn.

8. The martyrdom of Muslim b. ‘Aqīl and the death of several of his sons.

9. The arrival of the Imām Ḥusayn at Karbalā, the battle and his martyrdom.

![]()

179

10. The events that happened to the Ahl al-bayt in Karbalā, and the punishment that befell those who were compact breakers and seceeders. Conclusion, genealogies of the grandsons and descendants of the Ahl al-bayt.

1-4 are a preliminary to the Karbalā events.

Ḥadīqat al-Su‘adā by al-Fuḍūlī, which was written before 963/1555, had among its main aims to make the Turkish reader, as opposed to the Arab and the Persian, familiar with the deeds of the Karbalā martyrs and their sufferings. It had an appeal for the masses and not only for a lettered elite. It is not simply a translation of Rawḍat al-Shuhadā’, but surpasses its model in a number of respects; al-Fuḍūlī shapes his material as he wishes. The eleven parts into which the work is divided vary in some respects from those of its predecessor.

1. A statement of the circumstances and background of the prophets and their deeds, including Muḥammad.

2. The harsh treatment suffered by the Prophet Muḥammad at the hands of the Quraysh.

3. The death of Muḥammad.

4. The death of Fāṭima.

5. The death of ‘Alī’ al-Murtaḍā.

6. The circumstances of the Imām Ḥusayn.

7. The journey of the Imām Ḥusayn from Medina to Mecca.

8. The death of Muslim b. ‘Aqīl.

9. The coming of the Imām Ḥusayn to Karbalā.

10. The martyrdom of the Imām Ḥusayn.

11. The journey of the secluded womenfolk of the Ahl al-bayt from Karbalā to Damascus.

According to Ḥusayn Mujīb al-Miṣrī, Fuḍūlī’s work reveals a tendency both to simplify and to abridge the content of Rawḍat al-Shuhadā’. [25] It is a late work, composed at a time when he was drawn overwhelmingly to Shī‘īte piety and to an obsession with the ‘Alīd cause. His sympathies had been aroused by the example of the ‘Arna’ūdī Āyās Pasha, a devout follower of ‘Alī.

25. Dr Ḥusayn Mujīb al-Miṣrī, Fī l-Adab al-Islāmī, Fuḍūlī al-Baghdādī, amīr al-shi‘r al-turkī al-qadīm, Cairo, 1966, pp. 645-72 (esp. pp. 648-53). See also E.J.W. Gibb, A History of Ottoman Poetry, London, 1904, vol. III, Ch. IV, pp. 90 and 105.

![]()

180

Fuḍūlī encouraged him to take action against rebellious Basra in 1546, and on his way there. Āyās Pasha paid a visit of respect to the tomb of ‘Alī at Najaf where Fuḍūlī was residing at the time. Such an act by an Ottoman governor had no precedent. However, it was during the period of Āyās Pasha’s successor, Mehmed Pasha, that the poem on the Karbalā tragedy was written.

It is this literary and poetic expression of the Matam (Arabic Ma’tam), the recollection of the Karbalā tragedy, that distinguishes the Shī‘īsm (or somewhat more accurately expressed, Shī‘īte leanings) of the Baktāshiyya among the Albanians. It corresponds to the spectacular and dramatic expression of mourning and lamentation (ta’ziya) still to be witnessed in Iran and parts of Azerbaijan. [26] Persian and Turkish epic sentiments on this theme were to inspire the masterpieces ‘The garden’ (Hadika or Hadikaja) or ‘The garden of the martyrs’ (Ḥadīqat al-Su’adā’ in Arabic, Kopshti i të Mirëvet in Albanian) by Dalip Frashëri, nicknamed Hyxhrati, an uncle of Naim Frashëri. This is a landmark, and is arguably the first and the longest ‘epic’ known in Albanian literature. We know little of the life of its author. Dalip Frashëri was born in Frashër and played an important part in the life of the tekke there. He may have finished writing this poem on Friday 21st Rabī‘ II, 1258/1842. Its content reveals a blend of Arabic, Turkish and Albanian Islamic terms and idioms. The poem totals some 56,000 verses (adab). Centred upon the Karbalā story, it may be seen as an attempt by an Albanian to rival that task already undertaken by al-Fuḍūlī al-Baghdādī in his Ḥadīqat al-Su‘adā’. While the latter poet had both poetry and prose in his composition, Dalip Frashëri relied almost entirely on verse to achieve his intentions.

He divided his work into ten parts, preceded by an introduction. In the latter, the poet surveys the history of the Baktāshiyya among the Albanians, deriving information, apparently sent to him in Korçë, from Bābā Shemimi in Krujë and from Bābā Naṣibi (Nasībī) in Frashër. He outlines who were the sect’s important personalities, who of note joined the order and who took part in its propagation. Following this, he traces the history of the Arabs before Islam, then describes the events in the life of the Prophet, his death and all the major happenings that led to the Karbalā tragedy. The battle is described in detail and he eulogises

26. I. Lassy, The Muḥarram mysterices among the Azerbaijani Turks of Caucasia, Helsinki, 1916, furnishes in considerable detail the mysteries among another Shī‘īte community.

![]()

181

those who fell as martyrs, especially the Imām Ḥusayn.

This enormous poem shows the impact of the Baktāshiyya on Albanian life, including Albanian customs, festivals and sensibilities. An example is the habit, during the first ten days of Muḥarram, of refraining from drinking water. This was out of respect for the martyrs before the battle, and in their memory. The tekkes were chapels where a number of memorial services and vigils were held. Over ten days, the story of the martyrdom was retold during nightly gatherings. Verse was recited. At first, it seems, an attempt was made simply to translate al-Fuḍūlī’s Ḥadīqat al-Su‘adā’ into Albanian, so that it might be used on such occasions. However, Dalip Frashëri filled the need with a truly national and comprehensible composition. His tenfold division of the work was undoubtedly meant to facilitate its use in services held in tekkes and in homes during the Matam.

A second ode was composed by a younger brother of Dalip Frashëri and uncle of Naim, Shahin (Shahinin) Frashëri, and probably completed in 1868. Little is known of the author or the reasons for its composition. It is called Mukhtār Nāmeh (Myhtarnameja) and its content relates to al-Mukhtār, his rebellion in 685-7 and his ‘Alīd movement aimed at avenging the death of Imām Ḥusayn. It has 12,000 verses and is claimed by some to be the second epic in Albanian relating to the events of Karbalā and their aftermath. Undoubtedly, the work has as its starting-point the Persian epic on this theme, although Shāhīn Frashëri used a Turkish version as his model. It is one of the last major Baktāshī Shī‘īte works in Albanian to be written in Arabic script. After it the Baktāshīs relinquished the Arabic alphabet.

According to Muḥammad Mūfākū, [27] both these epics had a lasting influence on modern Albanian literature. They established the genre, the epic form employed by Naim Frashëri for his poem on Skanderbeg. It also made Karbalā an important event in the minds of all Albanians. Furthermore, the two poems were to inspire the major Islamic composition of Naim Frashëri, his own epic in Albanian on these same events, Qerbelaja. [28]

27. Conveniently condensed and summarised in Muḥammad Mūfākū, ‘Karbalā’ fī’l adab al-Albānī’, in Malāmiḥ ‘Arabiyya Islāmiyya fī’l-Adab al-Albānī, Damascus, 1991, pp. 31-65.

28. One of the earliest references to this work in the West is a comment made by G. Jacob in is article Die Bektaschijje in ihrem Verhaltnis zu verwandten Erscheinungen, in Abhandlungen der Philosophisch-Philologischen Klasse, XXIV (1909), Munich, p. 11. Jacob discloses that on p. 51 in the Zeitschrift Albania, 1898, which he had read in Strasbourg, he discovered a reference to ‘Qerbelaja’, poème religieux, par N.H.F. (Naim Frashëri), Bucharest, 1898: ‘C’est l’histoire religieuse des Bektachis racontée par un homme de foi et de talent.’ This book was unobtainable, which he regretted, although he could sense from the information that he had gleaned that even though the description of its content was not entirely correct, it was of some value in shedding fresh light on the history of the movement that was to evolve into a national branch of the Baktāshiyya. Albania was thus to become the most important centre of that movement, at least for a time.

![]()

182

7. ‘Qerbelaja’

When Naim was young he had heard Hadikaja and Myhtarnameja recited in his tekke, and he resolved in this major work to combine his own beliefs with his ardent nationalism, and to aim at a national epic that would appeal to all sections of Albanian society, despite the constant introduction of Baktāshī terms in his verse. He worked on its composition between 1892 and 1895, and it was published in Bucharest in 1898. Qerbelaja is in 10,000 verses.

Unlike its precedessors, its content is extended over twenty-five sections, or chapters, each verse rhyming in couplets without any break within each individual section. It therefore differs from Historia Skenderbeut, which is broken up into shorter sections.

Among the works most clearly reflected in the content of the Karbalā epic, works which Naim published at various stages of his career, are: (a) Fletore e Bektashinjet, which, in its pages relating to Baktāshī belief in the twelve Imāms, and in the succession to Hājjī Baktāshī, appears almost verbatim in Qerbelaja; (b) Naim’s monistic and monistically-influenced verse and the shared Ṣūfī belief in the unity of existence (waḥdat al-wujūd) and his essay on the Arabs; (r) Arabëtë, published in his Histori e Përg jithëshme për Mësonjëtoret të para (1886). A large part of this last essay is taken up with the disputes in the Caliphate, and in particular the conflict between ‘Alīa nd Mu‘āwiya and the events before and after Karbalā. The figures of ‘Alī and Ḥusayn (though quite contrary to the historical evidence) owe much to the heroism of the romantic era, including Naim’s own character-study of Skanderbeg.

In Part 1, the pre-Islamic Arabs are presented as a people, then it introduces the Prophet Muḥammad, his rejection by the Quraysh, his hijra, the victory of Islam, the death of Muḥammad and the differences within the Caliphate up to the death of ‘Uthmān.

In Part 2 allegiance (bay‘a) is sworn to ‘Alī, who is portrayed as an upholder of social justice, a prophet in all but name.

![]()

183

He is compared with noteworthy mystics such al-Ḥallāj and Muḥyi l-Dīn Ibn ‘Arabī and with earlier biblical characters, and stress is laid on the ‘father status’ of ‘Alī and the ‘mother status’ of Fāṭima in the Muslim community, a point already made in Naim’s Baktāshī leaflet.

In Part 3 the poem is concerned with the difficulties that arose following the allegiance given to ‘Alī, who only acted as he did in self-defence. The ‘battle of the camel’ is fought against Ṭalḥa and Zubayr in 656, in which ‘Alī was victorious and after which he was recognised as Caliph throughout Iraq.

In Part 4 the poem touches on the dispute that arose between ‘Alī and Mu‘āwiya and takes the story up to the crucial battle of Ṣiffīn. Mu‘āwiya’s troops are in dire straits without water but ‘Alī generously allows them to have access to it. For dramatic effect Naim extends the length of this battle to four months.

In Part 5, there is a description of the heroic feats of ‘Alī in the battle, mounted on his white mule, formerly the Prophet’s al-Duldul (duldyl), ‘the hedgehog’, and armed with his sword Dhū’l-Fiqār. He attempts to stem the slaughter and challenges Mu‘āwiya’s troops and their ruse in raising the Qur’ān aloft on their lances. This is followed by the mediation of Abū Mūsā al-Ash‘arī and the deception of ‘Alī by ‘Amr b. al-‘Āṣ.

Part 6, outlines the circumstances that led to the assassination of ‘Alī by Ibn Muljam. Naim links this event with plots by Mu‘āwiya. ‘Alī is buried in al-Najaf, though he ‘lives in the hearts of those who love him’. The numerous assassination attempts on the life of Imām Ḥasan are mentioned. He dies, poisoned, at the forty-first attempt.

In Part 7, Mu‘āwiya asks all to swear allegiance to his son Yazīd (Jezit’ is synonymous with evil in Albanian). Imām Ḥusayn refuses and he flees from Medina to Mecca. The men of Kūfa ask him to join with them, but he is counselled not to go. He sends Muslim b. ‘Aqīl there with his sons, Ibrāhīm and Mukhtār. Muslim b. ‘Aqīl is isolated in the city.

Part 8, is an account of the confrontation between ‘Ubaydallāh b. Ziyād and Ibn Muslim.

Part 9, portrays the journey of Imām Ḥusayn to Kūfa. On his way he is stopped by the poet al-Farazdaq who begs him to return. He continues and learns of the death of Muslim b. ‘Aqīl and his two sons. He is stopped by al-Ḥurr b. Yazīd al-Tamīmī who is accompanied by 1,000 horsemen. The latter demands the return of the Imām, who is undecided but when darkness falls has resolved to continue to Kūfa.

Part 10 describes the arrival of Imām Ḥusayn in Karbalā.

![]()

184

He meets Ibn Ziyād and seeks permission to continue on his way. He is told that he may do so, provided he swears allegiance to Yazīd. The Imām refuses and Ibn Ziyād tells his men to surround him and his followers. They are cut off from the water of the Euphrates, but Imām Ḥusayn in this grave crisis sees visions and consoles his thirsty warriors. In a dream he meets Muḥammad, ‘Alī and Fāṭima, and sees God’s throne and weeping angels who await him.

In Part 11, before the final engagement, there are discussions between Imām Ḥusayn and ‘Umar b. Sa‘d who tells him to offer allegiance to Yazīd. In the enemy camp there is a dispute between al-Ḥurr b. Yazīd and ‘Umar, who withdraws and joins the Imām.

Part 12 is a description of the battle of Karbalā. Naim makes his first appeal to his fellow-Albanians to ponder on the events in Karbalā and to love its heroes.

Part 13 outlines the heroism of a number of the martyrs. The deeds of ‘Abdallāh b. Muslim and Muḥammad, the grandson of Ja‘far al-Ṭayyār.

Part 14 is a description of the frightful thirst endured in the heat of the sun.

Part 15 describes the exploits of Zayn al-‘Ābidīn, who falls sick after great gallantry but recovers in order to help Imām Ḥusayn.

Part 16 is the point where Imām Ḥusayn seeks to break out from his position and appeals to his foes.

Part 17 is the climax of the epic. Imām Ḥusayn, amid tears, bids farewell to his womenfolk and prepares to die while attacking his foes with great courage.

Part 18 introduces a comment by Naim on the significance of Karbalā. The Imām has fallen but the battle was not a defeat. Zayn al-‘Ābidīn is brought to Kūfa.

Part 19, explains how the news of his death was spread abroad. Ḥusayn’s head is carried to Yazīd. He breaks its teeth with his whip. Those who witness it are appalled at this disrespect. Yazīd is punished for his misdeeds before he dies. Mu‘āwiya II expresses no wish to assume power and is assassinated.

Parts 20-24 are historical surveys, describing the fall of the Umayyads and the rise of the ‘Abbāsids in whom great hopes were placed but whose conduct of affairs reverted to the injustice and the abuses of the Umayyads.

Part 25 is a summing-up of the message of the epic. It is here that Naim Frashëri speaks in the first person. There are also open confessions

![]()

185

of faith in the creed of the Baktāshiyya, including the belief in the twelve Imāms and in Ḥājjī Baktāsh:

Besuatnë Perëndinë,

edhe Muhammet Alinë,

Haxhdien’e Fatimenë,

Ḥasanë edhe Hysenë,

Imamet të dymbëdhjetë

që ishinë të vërtetë.

Kemi mërn’ e at’ Alinë

q’ e njohëm si Perëndinë,

të parë kemi Xhaferë,

nukë njohëmë te tjerë,

kemi plak mi njerëzinë

Haxhi Bektashi Velinë,

Zotn’ e udhës së vërtetë,

q’ ishte si Aliu vetë,

se ishte nga ajo derë,

p andaj mori gjithë nerë.

The triple relationship (the expression ‘trinity’ is misleading) of Muḥammad to ‘Alī and to the incarnated Divinity is expressed in various ways, although in principle all are common to both Baktāshīs and Kizilbaș. The Muḥammad-‘Alī conjunction is a manifestation of the workings of the ‘light of Muḥammad’ (Nūr Muḥammadī). Both symbolise the trust and security that is found solely in the Godhead. [29] Both are located within the mystery of the creation of the world.

29. See E.G. Browne, A History of Persian Literature under Tartar Dominion, Cambridge, 1920, pp. 474-81. Time and God are the sole active force for good. ‘Time’ appears to indicate that period wherein God has acted and acts within history since creation began and throughout His universe, and in the manner expressed by the Persian (Ḥurūfī-influenced) poet, Qāsim al-Anwār. To cite Professor Browne’s fine translation of the latter’s verses:

In six days runs God’s Word, while Seven

Marks the divisions of the Heaven,

Then at the last He mounts His Throne’

Nay, Thrones, to which no limit’s known.

Each mote’s a Throne, to put it plain,

Where He in some new Name doth reign.

Know this and so to Truth attain.

God is the sole truth. In Mankind and Humanity God is manifested. Nowhere else can He be so closely found. He who loves Mankind in all honesty and with sincerity loves God, while he who loves not Humanity has no love of God in his heart.

![]()

186

Hence Muḥammad-‘Alī is synonymous with the divine aim that is the goal of man. There is no God but God, Muḥammad is His Prophet and ‘Alī is His friend (Watī Allāh / Veliyullah). Three names become as one name in the ultimate meaning of Love (maḥabba). This is vocalised in the dhikr (zikr). From this indivisible nomenclature is made manifest an in-dwelling and all-pervasive ‘Divine Light’, not only in ‘Alī who is the youth of valour, but likewise in his sword. ‘There is no sword, but Dhū’l-Fiqār.’ This manifestation is also to be observed in the twelve Imāms and their offspring. The names of those Imāms are sacred names that are to be learnt, repeated and used as an object of meditation, likewise the names of the ‘Fourteen Innocents’ who were begotten only to be martyred.

Muḥammad Mūfākū, in his articles devoted to Naim, [30] concentrates on the national sentiment that is condensed within the poem. He observes:

Undoubtedly Naim [Na‘īm] the poet, in these verses and others from his creative works and writings, exerted a major influence on the souls and hearts of the Albanians. Turkish authority, with success, employed the faith as an agent for its own ends in the Albanian regions, so that the word ‘Turk’ or ‘Turkish’, which became synonymous with being a Muslim, was applied in general to the Albanians. As a consequence there was no longer any meaningful existence for the Albanians as a people or for the Albanian language in the view of the Turkish authority. The latter fought fiercely against every attempt to open a school to teach the Albanian language, just as it waged war against every attempt to gain an independence that arose from the depths of Albanian national feeling, which became [in its eyes] a confiscator and an enemy of the faith.

However Nairn, as we see him, places matters in context by a logic that runs counter to this. With Naim no contradiction is to be observed in the essence of religion between love for the sons of men and the Albanians’ love of themselves. Just as ‘every sparrow has its nest, so has every people its homeland’. By this logic the Albanians had their homeland just as the Turks had theirs, and it was their right to enjoy it.

In the same way, Naim tackles the question of language: ‘Let us learn our language since God has given it to us.’ In this way he transforms the Albanian language, which must be learnt for it comes from God. Since it is a divine language, one has a right to protest against being taught another language, Turkish, which will cause one to forget one’s language that is divine in its source and in its inspiration. In this national spirit Naim closes his epic.

30. These views are reiterated in a number of Muḥammad Mūfākū’s writings, e.g. those articles concerned with Qerbelaja. The contribution of Naim is especially relevant in his article on the Baktāshiyya in al-‘Arabī, no. 220, pp. 67-8.

![]()

187

He tries to link Karbalā in some way with the future of Albania and the Albanians. He wants an Albanian to find his inspiration in the events which occurred in Karbalā for the interest and welfare of his homeland and his nationalism. ‘Let him die for the sake of his homeland, just as al-Mukhtār b. Abī ‘Ubayd al-Thaqafī died for the cause of Ḥusayn.’

O God, for the sake of Karbalā,

for Ḥasan and Ḥusayn

for the sake of the twelve Imāms

who suffered as they did whilst they lived,

Do not let Albania fall nor perish.

Rather let it remain for ever and ever

Let is attain its aspirations,

Let the Albanian remain a hero, as he once was,

In order to love Albania

Let him die for the sake of his homeland

Just as al-Mukhtār died in the cause of Ḥusayn

So that he can honour Albania.

Our final vision of the epic is from this angle. Whereby we esteem it a work of value. Without doubt Naim had a major influence on the hearts and souls of Albanians with this national spirit. He was aware of how he could arouse the reader who had become deeply attached to the events that took place in the epic, which was written to set the Albanians a lofty example. It has remained so in their minds down to the present day, repeated on several occasions and printed more than once. In this sense the epic remains alive.

To conclude, one has to point out that the battle of Karbalā made a big impact on Albanian literature. There were many poets who contributed their share to more refined and sensitive literature, who wrote at length in verse about Ḥusayn for them to be recited in memory of ‘Āshrūrī. Among these, on the purpose and cause of the martyrdom, was [the poet] Bābā Sersem ‘Alī who was born at the end of the fifteenth century [sic] and reached highest office in the time of Sulaymān the Magnificent, and the poet Bābā Qemaludin Shemīmī and others among the major Albanian names that merit independent study.

The formulation of these notions and the goal of these visions have to be considered as part of the movement that all the Frashëri brothers tirelessly served. Naim was keen to convince the Baktāshī Bābās in Albania that they needed a senior from among them to whom they could turn for guidance and teaching. Henceforth there would be no need to visit the tekke in Hacibektaj to be given instructions. They were in need of a contemporary ideology that would allow them to participate fully in the national uprising. His brother Abdul-Bej visited the principal

![]()

188

tekkes and obtained the support of Bābā Alushi to win the incumbents to his cause. Sami saw the transformation of the hierarchical structure of the Albanian Baktāshiyya into a political party organisation, and set forth a charter in his famous and much-read work (Shqipëria — C’ka qenë, c’është dhe ç do të bëhetë (Albania, what is was, what it is and what will become of it?), Bucharest, 1899. In the chapter reviewing the organisation of the religions in a future Albania, Sami Frashëri concludes that it should be conjoined to the Ministry of either Education or of Justice. Elsewhere in his book, Sami Frashëri adds that the heads of the religions in Albania — the chief mufti of the Muslims, the Orthodox Patriarch and the chief bishop of the Catholics — ‘will occupy a place of honour and respect but will only interfere in matters of faith and belief. This ideological evolution of the Baktāshiyya in Albania was to run parallel with another development that overtook the order in connection with its organisation. As it evolved within Turkey, the Baktāshiyya was a Ṣūfī brotherhood, whereas in Albania it was to be turned into a political party, with its own aspirations to power and an authority special to it. The Baktāshiyya in Sami’s scheme should adopt a ‘hierarchical’ party system in which the rank held by a member is graded and his status conforms with his seniority and the proportion and degree of his commitment and loyalty. The ranks were, in ascending order, ‘Āshiq, Muḥibb, Darwīsh, Mutajarrid, ordinary political party member, Bābā, Khalīfa, assistant to the Supreme Shaykh, and the Supreme Shaykh.

The Baktāshiyya found it necessary to clarify its identity over the language and the alphabet. From the start the Baktāshīs had adopted a firm stance, adhering to Albanian and hotly defending its non-substitution by Turkish. The Baktāshiyya shared in the battle to choose the Albanian alphabet. For a while, the Bābās welcomed the Arabic alphabet, but they retracted and reversed their position, demanding the Latin alphabet and consistently pressing for it until it finally prevailed.

8. Twentieth-century Ṣūfī poets of Kosovo

The continuation of the still living tradition of Ṣūfī verse in Albanian regions, especially in the Arabic script, may be seen among the poets of Kosovo. This is not surprising. The pervading influence of Turkish and Arabic idiom and vocabulary are observable at all levels and far more so than in almost any other Balkan region. Popular songs reveal it. As Stavro Skendi remarks,

![]()

189

I have noticed that the songs which have originated in Kosovo usually have more Turkish words than the other Albanian heroic songs. The Kosovo towns have been influenced more because they have been inhabited partly by Turks. Also, the songs of Kosovo have Turkish words — often of Arabic or Persian origin — which are altogether foreign to the Albanians of Albania proper. [31]

If one turns specifically to Arabic, the continuation of the composition — much of it centred on Ṣūfīsm — in Albanian, written in the Arabic script, marks out Kosovo from all the other regions of Yugoslavia after the First World War. Elsewhere, those who favoured the retention of the Arabic alphabet were defeated by the ‘Westerners’ who demanded its replacement by the Latin alphabet. In Kosovo, however, where the Albanian language was proscribed, the Arabic script was preserved, especially in the madrasas and the Ṣūfī tekkes. Those who maintained the tradition were either poet-teachers in madrasas or else shaykhs or dervishes from among the mashāyikh of the Ṣūfī orders.

Among those who continued to write in Arabic was Shehu Hysena Halwative of Prizren (1873-1926). After graduating in one of the madrasas he became an imām early in the twentieth century. He turned to Ṣūfīsm and was affiliated to the Khalwatiyya ṭarīqa. He obtained the ijaza and became the shaykh of one of the tekkes, after which his name became more generally known. Since no Albanian books or journals were printed, his poems were copied or memorised and became the property of Kosovans, some of them illiterate.

Ṣūfīsm was expressed in verse and there were other Shaykhs who were renowned for it. Amongst them was Shaykh Hilmi Maliqi (1856-1928), who was born in a village near Prizren. He moved to Rahovec where he too became an imām. Converted to Ṣūfīsm, he became a member of the Malāmiyya ṭarīqa; he was associated with Arab Hoxha (Muḥammad Nūr al-‘Arabī) and took the ijāza from him. His example favoured the spread of the Malāmiyya and a tekke was built for him in Rahovec where he remained till his death. This tekke was to become a cultural centre.

Shehu Hilmi’s wide interests in letters, philosophy and the natural sciences resulted in the tekke becoming a free school for the surrounding populations. The dīwān of verse attributed to him contains seventy-nine odes in which Arabic metres and rhyming letters are used. Sixteen other odes by him are preserved in his tekke. One of the odes, titled al-Risāla,

31. See Stavro Skendi in the Bibliography.

![]()

190

deals with Ṣūfīsm, and with historical, spiritual and emotional subjects. The poet, Hafiz Islam Bytyci (al-Ḥāfiẓ Islām Bytyashī), was born in 1910 in the village of Llapusha and completed his Qur’ānic education in Djakova. He died tragically when only twenty-four in 1934. He had composed love verse which eloquently reveals his knowledge of Oriental themes and imagery. Other noted poets include Faik Maloku of Prishtinë who became a director of a religious school in Podijeva and who died in 1935. His poetry extensively quotes Qur’ānic verses and Prophetic ḥadīth. Hafiz Imer Shemsiu was also born in Prishtinë. He directed a Qur’ānic school in Sazli and died in 1945, having composed a quantity of religious verse in Albanian in Arabic script. Shaip Zuranxhiu (1884-1951) was born in Mamushë near Rahovec, and was a pupil of Hilmi Maliqi and a member of the Malāmiyya order. To him are attributed seventeen poems in Albanian, twenty in Turkish and five in Serbo-Croat, all of a devotional nature. Sheh Osman Shehu (d. 1958) was shaykh of a Khalwatiyya tekke at Junik. His son Sheh Xhaferi composed a number of noteworthy poems, one of which, ‘Come, O brothers’ (Ehi Vllazën Ehi), expresses the true essence of Ṣūfīsm and especially the duality within it of the exoteric and the esoteric sciences. Muḥammad Mūfākū rendered part of it into Arabic, and the following English rendering is based on this and the original Albanian:

Let the eyes of your heart be opened

and, with the eyes of your brow,

direct your gaze towards the Ṣūfī way.

Thereby is disclosed that artery that goes forth

from the heart, and the artery, likewise,

that rises upwards to the forehead.

That man who, by perception, is not made cognisant of Reality,

shows that the artery of his heart functions no more. [32].

9. The Baktāshī legacy in the verse of Bābā ‘Alī Tomori

The religious and literary legacy of Naim was continued into the first half of the twentieth century by leading Baktāshīs in Albania and the Middle East. Among their number must be counted Baba Ali Tomori (d. 1947).

32. Information on Sheh Osman Shehu and his son Sheh Xhafari may be found in Muḥammad Mūfākū al-Thaqafa al-Albāniyya fī’l-Abjadiyya al-‘Arabiyya, op. cit., pp. 173-4, and in Hadjar Salihu, Poezia e Bejtexhinjve, 1987, op. cit., pp. 467-9 (verse 5 on last page).

![]()

191

Born near Tepelenë, he studied in Ioannina where he not only read in European languages but became devoted to a study of language in general. During sojourns in the tekkes he mastered both Turkish and Arabic. Apart from the tekke at Prishtë, where he studied under Baba Shabani, he journeyed to Cairo and became attached to the tekke there for some years. He returned to Prishtë and showed his affection for it by calling himself Varfë Ali Prishtë. Later he went to Tomor. During the First World War years he found life difficult owing to the destruction of the Albanian tekkes by the Greeks; nevertheless, he showed no hostility whatever to the Christian faith. In 1921 he attended the first Baktāshī Congress and thereafter devoted his life to the reform movement and to assuming the administrative responsibilities that were necessary to promote the progress and survival of his order and its following.

Despite these duties he found the time to write at least four books and a large quantity of lyrical and religious verse in Albanian on Baktāshī subjects. Foremost among the books were Histori e Bektashizmës, a history of the sect, published in Tiranë in 1929, [33]

33. On Baba Ali Tomori, see Baba Rexhebi, Misticizma Islame dhe Bektashizma 1970, pp. 367-72, and Nathalie Clayer, op. cit., pp. 409-11. Two of his poems are concerned with Baktāshī saints of the past, the first a panegyric in which their names are listed ‘Shënjorët e Shqipërise’ (Saints of Albania), and the second ‘Vjershëtorët Bektashinj’ (Poets of the Baktāshiyya). In the latter’s verses, names of outstanding poets are listed from the whole history of the sect.

The Baktāshī missionaries include: Ḥājjī Bābā of Khurāsān, who founded his tekke in the seventeenth century, Sari Saltik of Krujë, Bulgaria and Romania; and Shemīmī Baba of Krujë, who was spiritual advisor to ‘Alī Pasha and a promoter of the recitation of the Ḥadīqa by Fuḍūlī. Then came Ṭāhir Nasibiu, who founded the Frashër tekke in 1825 and was a master of Persian and Turkish; and then came Asim Baba and Arshi Bābā of Gjirokastër, Sersem ‘Alī of Kosovo who allegedly lived in the late sixteenth century and is buried in the Macedonian tekke of Kalkandelen, Gül Baba whose türbe is in Budapest, Kuzu (Kosum) Bābā of Vlorë, Bābā ‘Alī of Berat, Muṣṭafā (Xhefaj) Baba of Elbasan, Abdallāh Baba of Vlorë, Bābā ‘Alī of Berat, Abdallāh Baba Melçani the successor to Ḥusayn Bābā who founded the tekke in Melçan near Korça in the mid-nineteenth century, Baba Tahir of Prishtë tekke founded in 1860 near Berat, and Sanxhaktar Abbas Ali who founded the tekke on the slopes of Mount Tomor, one of the earliest in Albania.