4. MUSLIM HEROES OF THE BULGARS, THE TATARS OF THE DOBRUDJA, THE ALBANIANS AND THE BOSNIANS

Let us give thanks unto the Almighty who brings us forth from nothing into light!

The sun shines forth in all its strength, yet how meagre is the warmth it gives!

The wintry squall bends the elms at Jutbina. [*] A bitter hoarfrost carpets the terrain.

The snowy beech-trees bow to breaking point. Only the tips of maple-trees are seen.

Avalanches sound within the valleys. They tremble, roar and fill the deep ravines.

When the shepherdesses went to tend the sheep beside the river hank, they saw that the river bed was frozen. They traced their path to springs though these were all with hoar-frost covered.

Alarmed, the shepherdesses pondered, What will happen to our animals? When is it the Lord's will to melt the ice and snow?'

‘Good Lord' they cried, ‘who are these wayfarers princely clad? To us like knights they seem!

Have they not gone to scout those frosty tracts that block all channels?'

At this point Jera answered her companions, ‘Sisters, these are no nymphs who, but a while ago, next to the river stood.

Ti's Muyi who, with heroes of his own, goes forth to tramp the woodlands and to seek for game.’.

(From ‘The marriage of Halil’ in Ismael Kadare and Kole Luka, Chansonnier epique albanais, Tirana, 1983, pp. 156-7. For a full analysis of this folk-epic, see Maximilian Lambertz, ‘Die Volksepic der Albaner’, Zeitschrift der Karl Marx Universität, Leipzig, vol. 4, 1954-5, pp. 243-89.)

*. Jutbina is the fortress of the Albanian and South Slav hero Muyi Mujo, whose exploits, with those of other Muslim heroes of the Balkans, are described by Stavro Skendi in his Albanian and South Slav Oral Epic Poetry, American Folklore Society, 1954.

138

![]()

![]()

139

1. Oriental legends about the Arabian and Central Asian ancestry of the Bulgars and Arnauts 139

2. The folk epic, religious mission, miracles and many tombs of Sari Saltik 146

3. Krujë, Sari Saltik and Gjerg Elez Alia in Albania and Bosnia 155

1. Oriental legends about the Arabian or Central Asian ancestry of the Bulgars and Arnauts

Arabic writings of the ninth century and earlier, that recount stories of expeditions by Yemenite kings to conquer the earth’s four quarters, especially in Europe north of the Caucasus mountains, often furnish the framework for later simple or elaborated romances that provide an Arabian pedigree for Islamised peoples. These peoples were to be represented as defenders of the frontier regions of the faith in the steppes, the mountains and those plains that lay on the perimeter of the expanding, or contracting, Muslim world.

In the pictorial art and literature of medieval Europe, for example in the Hereford Mappa Mundi, such strange or grotesque peoples were deemed to be, at best, benighted — although Prester John, in Christendom, was felt to be a potential ally against the infidel. As soon as Islam had gained the allegiance or respect of such peoples, whether as ardent or reluctant converts (potorice) or as protected dhimmīs, Islamic scholars or story-tellers devised ingenious or bizarre games with tribal names and toponyms to show that ancient Arabs of noble blood had been there centuries before. Close by, they had planted colonies of their progeny, which would be ‘rediscovered’ at some later time. Subsequently, through faith in Allāh and His Prophet, they would be joined to the heartland of Mother Arabia. If not Arabia, then it was the ‘Arab’ seat of power in Baghdād, Damascus or Cairo that at a particular time in history came to represent the ‘Camelot’ of Arabian chivalry. Arab tribal honour had never been abandoned since ‘the days of ignorance’, but had been enhanced, purified and ennobled by the revelation of the true Qur’ānic faith by the mouth of its Arabian Prophet and through the incomparable and indeed inimitable diction of the Arabian tongue.

One such account is furnished by Abū Ḥāmid of Granada in the twelfth century. [1] Shaddād b. ‘Ād, the legendary Yemenite megalomaniac of pre-Islamic times, had a cousin named al-Ḍaḥḥāk b. ‘Alwān who commanded an army of 10,000 giants. One of his men, Lām b. ‘Āmir, was a believer in the Prophet, Hūd. This displeased al-Ḍaḥḥāk, but Lām eluded him by pretending to go on a hunt. He crossed the Caucasus and reached the land of the Slavs and the Hungarians (Bāshgūrd).

1. Gabriel Ferrand, ‘Le Tuhfat al-Albāb de Abū Ḥāmid al Andalusī al Garnāṭī, édite d’après les Mss 2167, 2168, 2170, de la Bibliothèque Nationale et le Ms d’Alger’, Journal Asiatique, July-Sept. 1925, pp. 129-31.

![]()

140

He arrived in a region west of Byzantium allegedly near the Black Sea. There he saw many trees and plants. He found springs of water and lush gardens and the air was cool and fresh. He discovered mines of blackish coloured lead (a commodity like wood that made the inner Balkan region economically important), and ordered that a dome of lead should be erected so that he could be buried within it. On a stone above his last resting-place were engraved some Arabic verses. These indicated that he was a believer in the Prophet Hūd, and explained how and why he had raised the dome of lead. They foretold that a Prophet (Muḥammad) was to be born and how Lām regretted that his mortal years had not been prolonged so that he could have met him in the flesh and given him homage.

Al-Ḍaḥḥāk, wrathful at being given the slip by his underling, sent an army led by two commanders in pursuit of him. One commander reached the Bulghār capital on the Volga, the other reached the Hungarians (Bāshghūrd). Al-Ḍaḥḥāk was slain. The Yemenite commanders, and their giants, settled among these northern peoples. Abū Ḥāmid reports how he had seen their enormous bones and teeth, and how the Qāḍī of Bulghār, Ya‘qūb b. al-Nu‘mān, had informed him that a giant sister of one such member of this ‘Ādite race — Abū Ḥāmid had met him and observed his strength — had killed her husband by hugging him to her chest in a way that recalled the embraces of a bear. [2]

Another, later account, that shares certain common diffusionist features with it may be read in the Arabic work entitled ‘A cogent demonstration of the lineage of the Circassians from Quraysh’. [3] This anonymous Mamlūk composition is a mixture of legendary Arab sagas that supposedly took place in the days of the Caliph ‘Umar. The source is given as an epistle or essay (risāla) written by a certain imām of a mosque in Ak Çehir in Turkey. He was named Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad al-Ṣafadī and he died in 980/1272-3. Part of this essay is about a noted Arab named Kisā b. ‘Ikrima b. Wadd b ‘Amr who, during horseplay, blinded another of the participants in one eye. Fearing the Caliph’s wrath and revenge, he fled with 30,000 men into Asia Minor and thence into Byzantine lands in the Balkans and in the Caucasus regions of the Black Sea near the southern borders of Bulghār, which is specifically

2. ibid., p. 131.

3. P.M. Holt, Studies in the History of the Near East, London: Frank Cass, 1973, pp. 220-30.

![]()

141

mentioned in the text. The area where he and his men were to settle was called Circassia. It was a landscape of watery glades, gardens and abundant produce. There they maintained the noble Arab virtues of pre-Islamic Arabia.

However, according to the risāla other Christian or pagan Arabs were to flee and settle in northerly regions in the early days of Islam. Two of the tribes specifically mentioned are the Banū Ghassān under Jabala b. al-Ayham — who, it is said, was given fiefs by Constantine II in Albania (Jabal Arnūd/Arna’ūd) and the Banū Mudlij who were settled in Spain. A third group had accompanied Kisā to Circassia. The risāla mentions that the Ghassānids were still represented by descendants in Albania at the time when its author Shihab al-Dīn wrote his work. Since the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus I (802-11), a contemporary of Hārūn al-Rashīd, was himself a possible descendant of Jabala al-Ghassānī (who, as the last Ghassānid ruler, had fled to Constantinople), it is not difficult to see how such a story originated, first in the Arab world and secondly within Ottoman sources.

We have seen how Krujë (Āq Ḥiṣār), in Albania, passed into Ottoman hands in 1396, during the reign of Bāyazīd. Both Yaqut Pasha and Hoce Firuz eased some of the tax impositions there. This is also recorded in 1431. [4] Hoce Firuz, in the last year of the reign of Bāyazīd, became beylerbeyi of Rumelia, Yaqut Pasha having previously occupied this post. After defeat by Tamerlane at Ankara in 1402, Ottoman influence weakened in Albania; the Venetians increased their pressure and captured the city of Shkodër. Betwen 1410 and 1415, Krujë was held by Nichita Thopia, but in 1415 Muḥammad Çelebi, having achieved Ottoman unity, turned his attentions to Albania, and especially the region of Krujë. In 1431 he revived the taxation concessions the town had enjoyed and it became the centre of a subașilik, although it may well have had this status earlier for a time. In 1438 Iskander Beg, the future Skanderbeg Kastrioti, held the post of subaș.

This campaign of Muḥammad I afforded Sayyid Aḥmad b. al-Sayyid Zaynī Daḥlān, [5] an opportunity to introduce in his Arabic writings

4. Elizabeth A. Zachariadon, ‘Marginalia on the History of Epirus and Albania (1380-1418)’, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, vol. 78, Vienna, 1988, p. 196.

5. al-Sayyid Aḥmad b. al-Sayyid Zayni Daḥlān, al-Futūḥāt al-Islāmiyya, ba‘d muḍiyy al Futūḥāt al-Nabawiyya, Cairo, 1323 AH, p. 81. For the factual history of relations between Byzantium and the Ghassanid Arabs see Paul Gombert, Byzance avant l’Islam, Paris, 1951, esp. pp. 249-70.

![]()

142

two legendary reports explaining the Arabian origin of the Albanians. He wrote:

Mention of the raid to the land of the Serbs, Bosnia and the Arnauts

In 863 [1458/9], he turned towards the land of the Serbs and made conquests there. In 866 [1461/2] he conquered the region of Trebizond and Sinope and brought its master captive to Constantinople. Sulṭān Muḥammad killed him. He had eight sons and [the Sulṭān] killed them [also]. The lord of Sinope was in correspondence with the king of the Persians and assisted him against Sulṭān Muḥammad. In the year 867 (1462/3) [the Sultan] turned afresh to complete his possession of the province of Bosnia and launched raids on the provinces of the Aflāq (Wallachians or Vlachs), the Bughdān (Moldavians) and the Ṣaqāliba. Then he directed his resolution towards the conquest of the country of the Albanians (Arnā’ūt). They are a race of Christians who possess a fortitude to withstand trials and tribulations. They take upon themselves hard labours. It is said that by origin they are from the Arabs of Syria, from the Banū Ghassān. They emigrated from Syria after Allāh had brought [the revelation of] al-Islām. They came from Syria and settled in this country. It is also said that by origin they are from the Berbers. They crossed the sea from the Maghrib in this direction. Then ignorance overcame them and they became Christians.

The Sulṭān entered the land of the Albanians, pillaged it and gained control over a number of citadels there. He ordered that a fortified castle should be constructed at a major frontier point to serve as a bamer between us and the infidels. He garrisoned it with men and called it Āq Ḥiṣār. Within it he deposited cannons and firearms sufficient to protect it. In the year 872 (1667/8), Sultan Muḥammad was angry with the lord of Konia and Laranda, and seized Karaman province from him. There he installed his son Sulṭān Muṣṭafā. Then he gained possession of obstinate fortresses such as Qal‘at Arklī and Qal‘at Āq Sarāy, Qal‘at Kūlak and Qal‘at Kūlī and appointed all of these to the possession of his son. In 875 (1470/1) he conquered the peninsula/island of Arghabūz, [6] one of the provinces of Venice, after descending in force on its people and slaughtering the majority of them. Then he conquered the rest of the land of the Albanians.

The story of the exile of the Banū Ghassān in Albania makes a pair with the account of al-Ṣafadī, source of the story of the Circassians’ origin from Quraysh. It is significant that Albania and Spain are mentioned together.

6. It is possible that what is meant is Hvar (Dalmatia), namely Vrboska, and the area of Korčula. J.A. Cuddon in his Companion Guide to Jugoslavia, London, 1986, pp. 105-14, has a number of references to folk memories (and dances) of Arabs, Moors and Turks in the area. Hvar was raided by Uluz-Ali (‘Ulj ‘Alī’, see Chapter 6) in 1571.

![]()

143

The reference to the Berbers, on the other hand, in the reports of Berber settlement among the Roman armies in the Balkans in ancient times, or else in some kind of way has come to be associated with the story of Arabs from Sicily or ‘Black Arabs’ in the area of Greece, Albania and parts of Yugoslavia. In either case, be it the Ghassānids or the Berbers, some allusion to population transfer and the settlement of mercenaries appears in the web of the narrative, however fancifully the tale is expressed.

An alleged kinship between the Albanians and some Caucasians on the one hand and the Banū Ghassān on the other seems to be a variant of a ruse employed far earlier by some of the Ṣaqāliba in Moorish Spain. Ignaz Goldziher pointed out in his article ‘Die Su‘ûbijja unter den Muhammedanern in Spanien’, [7] that the Ṣaqāliba were a very mixed group, although a genuine Slav element was to be found. Some of them may have stemmed from Balkan tribes. If Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī is to be believed, it is possible that some Bogomil or ‘Adoptionist’ elements were among them; ‘The Ṣaqāliba confess belief in the Creator whom they name ni‘am (perhaps derived from the Slavonic Bog?). He had a son. The world was inundated and the only person who remained was the Son of God (I think they mean Noah).’ [8]

Mixing and intermarriage as clients (mawālī) with the Arabs in Spain stimulated the invention of imaginative and fictitious claims to Arab ancestry. These were disputed although it was conceded that a number of the Ṣaqāliba were exceedingly skilled in Arabic language and grammar. Very popular was an alleged descent from Jabala b. al-Ay ham al-Ghassānī through a certain Mughīth. To cite the historian al-Maqqarī, ‘his true lineage is Mughīth b. al-Ḥārith b. al-Ḥuwayrith, b. Jabala b. al-Ayham al-Ghassānī.’

A recent story on this particular theme is told of Wāṣā Pasha, Mutaāarrif of Lebanon in 1883-92. Of Albanian origin, he was born at Shkodër in 1824. According to Muḥammad Khāṭir, [9] ‘Wāṣā Pasha was of Albanian origin, Catholic in religion. He was of the Mirdite clan which, our major historians confirm, traces its origin to 12,000 rebellious ones (marada) whom Justinian II evacuated from Lebanon.

7. Presented at the 12th International Congress of Orientalists in Rome, October 1899.

8. The evidence available is so scanty as to be highly speculative.

9. Muḥammad Khatir, ‘Ahd al-mutaṣarrifīn fī Lubnṣn (1861-1918) (The Age of the Mutaṣarrifin in Lebanon), Beirut: Manshūrāt al-Jāmi‘a al-Lubnāniyya (Dept. of Historical Studies), 1967, p. 139.

![]()

144

It is related that the Maronite bishop, Yūsuf al-Dibs, spoke frequently to Wāṣā Pasha about this link that tied him to Lebanon and he corroborated what he said, confirming that in this tribe there was an unbroken tradition from father to son that supported that genealogical tie between the Marada and the Mirdites.’

Philip Hitti, in his History of the Arabs, describes these Christian Arabs in the service of the Byzantine cause who were to take an active part in the early conflicts between the Byzantines and the Muslim Arabs.

A people of undetermined origin leading a semi-independent national life in the fortresses of al-Lukkām (Amanus), these Jarājimah (less correctly Jurājimah), as they were also styled by the Arabs, furnished irregular troops and proved a thorn in the side of the Arab caliphate in Syria. On the Arab-Byzantine border they formed ‘a brass wall’ in defence of Asia Minor. About 666, their bands penetrated into the heart of Lebanon and became the nucleus around which many fugitives and malcontents, among whom were the Maronites, grouped themselves. Mu‘āwiyah agreed to the payment of a heavy annual tribute to the Byzantine emperor in consideration of his withdrawal of support from this internal enemy, to whom he also agreed to pay a tax. About 689 Justinian II once more loosed the Mardaite highlanders on Syria, and ‘Abd-al-Malik, following ‘the precedent of Mu‘āwiyah’, agreed to the new conditions laid down by the emperor and agreed to pay a thousand dinars weekly to the Jarājimah. Finally the majority of the invaders evacuated Syria and settled in the inner provinces or on the coast of Asia Minor, where they became sea farmers; others remained and constituted one of the elements that entered into the composition of the Maronite community that still flourishes in the northern Lebanon. [10]

10. Hitti (Mardaites), pp. 204-5. See ‘Abbas al-‘Azzawī, Tārīkh al-‘Iraq bayn iḥtilālayn, Baghdād, 1949, vol. IV, p. 48, and Mūfākū al-Thaqāfa al-Albāniyya, p. 11. According to ‘Azzāwī, al-Wāli Āyās Bāshā (952-1046/1546-6) was of Albanian origin and rose to the Baklarbeyship — he was the brother of Sinān Pasha who conquered the Yemen for the Turks. He assumed the governorship of Baghdād after sacking Ṣūlāq Farhād Pasha, and then became wazīr, following the battle of Basra. According to the Ottoman archives, he assumed the post of governor of Diyarbekir in 956/1548, then Erzerum, and died in 967/1559/60. According to the Qāmūs al-‘Ālām (by Sami Frashëri), he was executed in Erzerum after facilitating the flight of al-Shahzāda Bāyazīd to Iran in 966/1558/9. He left several offspring: Maḥmūd Pasha and Muṣṭafā Pasha, and among his Mamlūks was the poet Ṣāfī Çelebi who died in 997/1588/9.

The ridiculous lengths to which an Arabic root for the Albanian name Arberi or Arbanese (which is quite distinct from the country’s name Shqipëria, as is found today) may be seen in an acid comment made by ‘Abbās al-‘Azzāwī in a footnote to his description of the governorship of Āyās Bāshā in Iraq. He remarks: ‘The origin of the expression Ārbāniyā or Ārbariyā, some pronouncing it in the former manner, and some in the latter; the Europeans say Ālbāniyā, and so it has come to us from their geographical and political translations. In Turkish it has appeared distorted, via the Byzantine Greeks who utter the word as Arbāniyā, or Arwāniyā, for the kingdom, and Arwānit for the people. The Turks pronounce it Arnārawīt or ‘Ārnāwud. Some of them have shown that its origin is found in a Persian word, ‘Ạrnabūd, meaning ‘It was no shame’, or an Arabic origin, ‘It is a shame for us to return’ [‘ār ‘alaynā an na'ūd]. Such is childish!’

An earlier European reference to these Arabian connections is to be read in ‘Notice géographique sur l’Albanie’ in Mémoires sur la Grèce et sur l’Albanie (1828), written by Ibrāhīm Manzour (Manṣūr) Efendi. On page xxv he writes:

The Albanians pretend that they are the descendants of the Arab tribe named Arnaboude [sic], expelled from Arabia at the epoch of the civil war which troubled this country, for the cause of ‘Alī, the son in law of Muḥammad. They base this assertion on the name which the Turks give to their nation, namely the word Arnaoude: but this reason is not admissible, considering that the name which the Albanians give to themselves in their own language is that of Chkipe (Shqip). Besides, their physique, their language, their customs and their usages have not, in any respect, the least analogy with the peoples of Arabia; also it is only as a consequence of their national pride that the Albanians give to themselves such an origin, which according to the ideas of Muslims in all countries is the most noble on earth, since the Prophet, his disciples, the Caliphs and all the evlias (awliyā’) (muslim saints) have been Arabs.

This story is of little interest in regard to general Arabian connections since there are widely differing theories among them as to how Arabia might enter into the obscure history of their origins. Significant though is the fact that the ‘Alīd and Carmathian affiliation is emphasised, immediately indicating that it owes its coinage to the Baktāshī, and not to the orthodox Sunnite element in its Muslim community.

![]()

145

The fanciful name- and word-play in such accounts as these is neither more banal nor more plausible than numerous others that one encounters throughout the Muslim world. However, if large numbers of ‘Slavs’ were settled in Syria and Asia Minor by the Byzantines, and if later some of them at least were transferred to remote areas of the Byzantine empire, frontier areas in particular, then it is not impossible that some Middle Eastern tales and oral traditions were carried with them. This was long before the arrival of the Ottoman Turks. Furthermore, all this folk epic soon attracted to itself other stories that may have come into the Balkans from Arab Sicily, Moorish Spain and the eastern steppes, brought by the Pechenegs, Khwārizmians, Cumans and other Oriental peoples. The Ottomans, on their arrival, found traces of these in Albania, in Bulgaria and within the mountain regions of Macedonia, Kosovo and behind the Dalmatian coast.

![]()

146

2. The folk epic, religious mission, miracles and many tombs of Sari Saltik

The peripatetic warrior saint Sari Saltik was, and still is, revered in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, in parts of the Middle East and possibly as far east as Sinkiang. Like the story, widespread in the Balkans, European Russia and the Caucasus, of the entombed maiden or sacrificed wife encased in a castle wall while it is being built, the adventure of Sari Saltik varies wherever it is recounted. [11] Specific towns and specific topographical localities are associated with some aspect of his story. Sari Saltik, buried in his tomb or on some promontory, or concealed in some cave, is reported in widely separated regions of the Balkans where Islam has a following: for example at Blagay in Hercegovina, Sveti Naum in Macedonia and Peja (Peć) in Kosovo. He seems to have had a particular significance for the holy sites associated with the Baktāshiyya. [12]

The Arab traveller Ibn Baṭṭūṭa is the earliest known source of a reference to him in Eastern Europe. It is recorded in the Moroccan’s famous travelogue (riḥla). At one point, he describes the journey that he undertook to the lower Dnieper region of Russia and the Danube Delta region, between the Crimea and Kavulī (Jamboli), at the southward bend of the Tunja (Tontzos) river in Bulgaria. This took place in July 1332 or June 1334. H.A.R. Gibb has translated this passage:

We came to the town known by the name of Bābā Salṭūq. Bābā in their language has exactly the same meaning as among the Berbers [i.e. ‘father’], but they pronounce the ‘b’ more emphatically. They relate that this Salṭūq was an ecstatic devotee, although things are told of him which are reproved by the Divine Law. This town is the last of the towns possessed by the Turks, and between it and the beginning of the territory of the Greeks is [a journey of] eighteen days through an uninhabited waste, for eight days of which there is no water. A provision of water is laid in for this stage, and carried in large and small skins on the wagons. Since our entry into it was in the cold weather, we had no need of much water, and the Turks carry milk in large skins, mix

11. Admirably surveyed by Grace M. Smith in her article ‘Some Türbes/Maqāms of Sari Saltuq an early Anatolian Turkish Gāzī Saint’ in Turcica, vol. XIV, 1982, pp. 216-25.

12. This is a fact generally acknowledged, although the tradition of a tomb in such localities as Gdansk in Poland has yet to be explained. Babadag in Romania is unique among the others. This is a genuine türbe of antiquity and linked to local history in the Dobrudja and not the spread of the Baktāshiyya ṭarīqa.

![]()

147

it with cooked dūgī, and drink that, so that they feel no thirst. At this city we made our preparations for [the crossing of] the waste.

The evidence suggests that it is with coastal Bulgaria and the place called to this day Babadag, in the Dobrudja of Romania, that the saint’s activities ultimately came to have a particularly close association. Yazicioğlu ‘Alī, who wrote during the reign of Murād II (1421-51), says that ‘Izz al-Dīn Kaykā’ūs II, who was threatened by his brother, found refuge with his followers at the court of the Byzantine emperor. He fought the latter’s enemies, and as a reward the emperor gave them the Dobrudja. The Turkish clans were summoned, and with Ṣarī Ṣaltiq (Sari Saltik) as their leader, they crossed over from Üsküdar and then proceeded to the Dobrudja. Such a migration has the unmistakable character of a folk epic destan, and it recalls another westward emigration, that of the Banū Hilāl nomads into Tunisia and North Africa. That was a reward for services rendered to the Fāṭimid rulers of Egypt in the eleventh century, and at the same time a form of punishment of their enemies in North Africa.

The historicity of the migrating horde allegedly led by Sari Saltik is bound up with the whole question of the entry of sundry Turkic groups into Bulgaria and beyond. Tadeusz Kowalski broached the question in regard to the origins of the ‘Turks of Deli Orman and the Gagaouzes’. He quoted the views of the Škorpil brothers that the ‘Turks of the Deli Orman’ were descendants of the Proto-Bulgar Turks who had escaped Slavisation. His view was in part based on a tradition, dating to the Ottomans, that a more ancient Turkish population had reached the country from the north-east. Moškov (although he also included the Gagaouzes) proposed the region north of the Black Sea and the route across its steppes as the direction from which this people had come. Nevertheless, while the Gagaouzes belonged to an Oguz group that may have entered the Balkans about 1064, the Deli Orman Turks were, in his opinion, Pechenegs who had established themselves around 1055 in the neighbourhood of Silistria in the Dobrudja with the permission of the Byzantine authorities. There they had mixed with oguz elements. Moškov maintained that the Turks of Deli Orman had been Islamised before the arrival of the Ottomans.

Jirecek gave a similar explanation for the origin of the Gagaouzes, although he regarded them as Cumans, who had settled in great numbers in Bulgaria after the Mongol invasion. Moškov’s view was that they were also Oguz Turks. They had come to the Balkans in 1064. He maintained that a part of them had withdrawn north of the Danube into

![]()

148

Russian territory, where they had mixed with other Turkish elements and formed a group under the name of Karakalpak. They had embraced Orthodoxy. According to him, a part of these Karakalpaks had returned to northern Bulgaria during the Mongol invasion and, under the influence of the Turks of Deli Orman, had given birth to the Gagaouzes.

Kowalski casts doubt on the historical value of all these speculations, pointing out the fragile evidence frequently to be found in undocumented local traditions. He turned to language as a possible key to the sequence of the entry of these peoples. The story of the journey of Sari Saltik and the Islamic mission of his followers, combined with fragments from Ibn Baṭṭūṭa about him and his lost city in the steppes of Russia or in Romania or Bulgaria, has to be put into some sort of historical and cultural perspective. [13]

The detailed research undertaken by Profesor Paul Wittek and published in his articles chronologically equated the legendary with the historical. [14] He confirmed that the Gagaouzes were the ‘people of the Kaikaus’ who had derived their name from ‘Izzeddīn Kaikāūs II, the Saljūq, who had crossed the Bosphorus during the reign of the basileus Michael VIII (Palaeologus) and who, as a reward for his services, had been appointed ‘warden’ of the Dobrudja region and settled there (‘Sari Ṣaltiq of blessed memory too crossed over with them’) around 662/1263-4. However, within the Oguznāme by Yazicioghlu ‘Alī, completed in 1451 (drawing on Ibn Bībī’s history of the Saljūqs of Rum, and on oral traditions and legends) a number of references were included to the spiritual guidance, intermediary acts and miraculous feats of Sari Saltik. The latter are especially centred around the release of the brother of Mas‘ūd, the successor to ‘Izzeddīn Kaikaus. This brother had been imprisoned by the basileus and surrendered to the patriarch. Converted to Orthodoxy, he had become a monk and served the patriarch for some time at the Hagia Sophia. It was Sari Saltik who asked for his release, and the patriarch agreed to this because of Sari Saltik’s great reputation as a saint. The prince was later to become a dervish and a holy madman, having swallowed the saliva of Sari Saltik which contained a supernatural power given to him while he was a shepherd by Shaykh Maḥmūd Ḥayrān of Aksehir.

13. See Tadeusz Kowalski, ‘Les Tures et la langue turque de la Bulgarie du Nord-Est’, in Polskan Akademja Umiejetnosci, Mémoires de la Commission Orientaliste, no. 16, Kracow, 1933, pp. 8-13.

14. Especially in his article ‘Yazijioghlu ‘Ali on the Christian Turks of the Dobrudja’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. XIV, part 3, 1952, pp. 639-88.

![]()

149

The demented dervish prince was caressed by Sari Saltik who called him ‘my dog’ (baraq). He was sent to Sulṭāniyya, and later died there. This city came to be associated with Baraqī and his disciples. Wittek points out the minor role played by Sari Saltik; furthermore, his people in the Dobrudja were said to have renounced Islam and forgotten it after his death. It is interesting that elements in this account correspond closely to the role played by Sari Saltik generally in the Balkan lands where stories about him were to be embellished, and attached to his peripatetic exploits and his numerous tombs, caves and tekkes. Wittek remarks:

Most interesting for our present study is the fact that Baraq presents a Christian as well as a Muslim aspect: born a Muslim prince, he is baptized and becomes a monk in the patriarch’s retinue, only to end as the founder of a mystic dervish order. The same is true also for Ṣari Ṣaltiq: he appears on the one hand as the spiritual leader of the Muslim nomad Turks and on the other hand he is regarded by the patriarch as a saintly man to whom unhesitatingly he entrusts the newly converted prince. This Christian aspect of Sari Ṣaltiq is clearly recognized in a fetwa of Abū’s-Su‘ūd, which has just come to light. This outstanding scholar and sheikhülislam of the 16th century describes Ṣari Ṣaltiq as ‘a Christian monk (keshīsh) who by asceticism has become a skeleton. [15]

Halil Inalçik relates these exploits to the historical events that seem to be the basis for some of the themes expanded in the folk-epic which stress the unorthodox beliefs of Sari Saltik himself. [16] Sari Saltik shares the characteristics that mark the heroic adventures of warriors of the faith in other epical tales and legends in the Arab and Turkish worlds, tales that were based on the expeditions (maghāzī) of the Prophet’s Companions and on those later Arab and Persian heroes about whom gestes were elaborated and recounted; superhuman characters such as Sayyid Baṭṭāl, Melik Dānishmend and Abū Muslim al-Khurāsānī. Here there is a close association with the Akhīs (the Akhiyat al-Fityān, plural of the akh, ‘the generous and the chivalrous’, one who in his person and status personified the ideal of Muslim chivalry) or with the artisan class. Sayyid Baṭṭāl, who also became associated with the Baktāshīs among the Turks, is not only an Arab hero of very great prowess, but also a lineal descendant of the Prophet and an adventurous ghāzī whose feats are directed at infidels whom he either converts or slays.

15. ibid., section 12, The Baraq Story, pp. 660-1.

16. Chapter XIX, ‘Popular Culture and the Tarikats-Mystic Orders’, in The Ottoman Empire: The Classic Age, 1300-1600, London, 1973.

![]()

150

But he is also scholarly and lettered. Like Abū Zayd al-Hilalī he is a master of disguise; he can appear as a monk and argue with Christian theologians. His feats are interlinked, through his warriors and his relations, with those of the revolutionary, Abū Muslim. [17] The episodes in the geste of Dānishmend are likewise to be included within the corpus of all these cycles of folk epics and feats of Muslim gallantry.

To such adventures can be added all that is recorded about the exploits of the warrior dervish Sari Saltik, under whose direction, as Alessio Bombaci describes, [18] a colony of Turcomans emigrated into Europe towards the middle of the thirteenth century. His exploits were narrated towards the end of the fifteenth century by Abū’l-Khayr Rūmī at the command of the Ottoman prince Djem. This took a written form although it would appear to have been based on some earlier corpus. In Alessio Bombaci’s view, the exploits of Sari Saltik show a marked resemblance to those of Sayyid Baṭṭāl. Early Arab and Muslim heroes and Persian champions, joined to all the wonders and marvels found in the One Thousand and One Nights, were here introduced. Saltik is mounted on Simorgh, the fabulous bird. He is anointed with the grease of the salamander, which assumes the form of a winged steed that is impervious to heat and is untouched by fire: it traverses the Mountain of Fire, and with its rider reaches the remotest land of darkness that is the kingdom of Ahrīman, the personification of evil. In Persian mythology he takes the form of the dragon-headed dīv. In the folkepic, which is set in the days of Osman, he predicts a glorious and illustrious future for his family. Elements in the story were to be adapted with little difficulty to folk-epics and heroic tales among Balkan peoples, but since in all traditions of folk-epic and popular romance this process is difficult to date one cannot say when a dragon-headed dīv was replaced by an Albanian hydra, or when Sayyid Baṭṭāl, dressed as a monk, may have become Sari Saltik, armed with his wooden sword and disguised as an al-Khaḍir or as a Christian saint.

Sari Saltik was incorporated into all the hagiographies of the Baktāshiyya, especially in the Vilāyetnāme of Ḥājjī Baktāsh.

17. The ‘epic’ facts of Abū Muslim are exhaustively surveyed in Irène Mélikoff’ Abū Muslim. Le ‘Porte Hache’ du Khorassan dans la tradition epique Turco-Iranienne, Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1962. See also La Geste de Melek Dānișmend, vol. 1, Paris 1960.

18. His name is spelt Sari Saltikh Dede. According to Alessio Bombaci, Histoire de la Littérature Turque (transl. by I. Mélikoff), op. cit., pp. 263-4. The adventures were narrated towards the end of the fifteenth century by Abū’ l-Khayr Rūmī, at the command of the Otoman prince Jem.

![]()

151

He came to be associated with certain spectacular feats: a flight over water on his prayer-rug, the conversion of the prince of Georgia to Islam, the cutting off of the heads of a seven-headed dragon in Kalagria (Kilgra near Varna in Bulgaria), and a lifetime spent in countless localities converting unbelievers (including the king of the Dobrudja) by his miracles and feats.

A number of such interconnected exploits, and the magical powers of Sari Saltik, may be traced in the corpus of the hagiographical lore of the Baktāshiyya, some of it Central Asian. Irène Mélikoff has shown how Loḳmān Perende (the flying Loḳmān), the master of Ḥājjī Baktāsh had the power to fly and to wander without head or feet. Sun-like, he was called Shams-i-Perende (the flying Shams). He had the power of ubiquity, appearing in different places at the same time. Ḥājjī Baktāsh also had this power, as also did Pīr Sulṭān Abdāl and Bābā Rasūlī. All of these men were seen in different places after their deaths. Sari Saltik’s bird-like flights, and his descents in Georgia, Bulgaria, Albania and Corfu are examples of Baktāshī hagiography.

The seven coffins of Sari Saltik match a story in the Vilāyetnāme about the dervishes of Khurāsān who sent seven of their numbers with the intention to invite Ahmed Yasavī to their meeting. They changed themselves into cranes, and then flew to Turkistan. Irène Mélikoff has drawn our notice to a comment made by Mircea Eliade that ‘the power of flying belongs to the world of myth; it is connected to the mystical conception of the soul under the form of a bird and of birds as guides of the soul’. [19]

The essential elements of the Sari Saltik cycle of stories, as they are retold among the Albanians and other Balkan peoples, as well as the Baktāshī Turks and Turcomans, are present in the high-medieval Vilāyetnāme of Ḥājjī Baktāsh. Leading motifs (such as have been identified and discussed in this geste) [20] include the first encounter between Ḥājjī Baktāsh and the shepherd, Sari Saltik, at Zamzam well, near Mecca and Mount ‘Arafāt, Sari Saltik gaining spiritual strength from the blessed eye of Ḥājjī Baktāsh, and the command given to Sari Saltik to go to Rum and to the Balkan regions. His receipt of a wooden sword,

19. Loḳmān Perende, the master of Ḥājjī Baktāsh, was a disciple of Ahmed Yasavī. According to Irène Mélikoff, citing Abdulbaki Golpinarli, there are three applicants to this title. She sees a connection between this title and that of turna, a ‘crane’. Many holy men had power to change themselves into a bird.

20. Described in Erich Gross, Das Vilajet Name des Haggi Bektasch. Ein Turkisches Derwischevangelium, Leipzig, 1927. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, al-Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, pp. 49-51.

![]()

152

a book, seven arrows and a flying carpet precede his adventures in Georgia and at the hill of Kiligra in Bulgaria. The rescue of a ruler, a prince or a princess, and the slaughter of a seven-headed dragon (which seems to match the seven bodies of Sari Saltik himself) all suggest a fusion with classical mythology in these regions, with the adventures of St George and with the Islamic cycles of rulers of the Yemen, aided by al-Khaḍir. These cycles were themselves Islamised fragments derived from the Alexander Romance, Pseudo-Callisthenes. Oriental thematic substance, the Turkish folk-epic cycles of Central Asia and Anatolia, all are combined here with early folk-lore and folk-epic of the Balkan peoples.

No town on the Russian steppes has so far been found where local legends are in some way connected with Sari Saltik and his followers. It was from the direction of Anatolia that he entered Bulgaria, and, as has been seen, any place associated with him must lie in, or around, the present-day town of Babadag in Romania. [21] If there is a tradition to be found among the Tatars, then this may tell of other journeys, migrations and wars of conquests. In a sense two people, the Turks and the Tatars, meet at the Danube’s mouth, and the tales converge there in a version given by Kamal Pasha Zadeh in his ‘History of the Campaign of Mohacz’, called by this title in the French translation by Pavet de Courteille and published in 1859. [22] In this account the army is Tatar and all its fighting men are believing Muslims. They had embarked at Sinope and Samsun and set sail for Rumelia. In the Dobrudja they became disciples of Sultan Sari Saltik and, having placed themselves willingly under the orders of this ‘possessor of the treasurers of piety, the pilgrim in the path and the terrain of holy jihād’, they followed his commands and made incursions into the country of the Bulgars and the Vlachs. Accompanied by knights of the Turkestani Oghuz, they captured abundant booty from the infidels.

The vast plain and steppe of southern Russia known as Dasht Qipjaq was ruled by one of the grandsons of Genghis Khan, Barakat Khan (Berke), whose ‘blessed head was the bearer of the glorious crown of al-Islām’. Mounting an invasion of Moldavia at the head of a horde, he achieved a resounding victory over the infidels.

21. For an effective argument in favour of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s town being Babadag, see J. Denny, ‘Sari Ṣaltiq et le nom de la ville de Babadaghi’ in Mélanges offerts à Emile Picot, Paris, 1913. See also G.G. Arnakis, ‘Futuwwa traditions in the Ottoman Empire’, op. cit., pp. 243-4.

22. M. Pavet de Courteille, Histoire de la campagne de Mohacz, Paris, 1859.

![]()

153

The Muslim armies encamped at Aq Kirman and Kiliya — the tombs and mausolea of their chiefs were to be seen near the Danube. Mention is made of Tarkhan Yazishi, Salpi (Yalpi?) Guli, Qutlu Bahaqatli Suwiy, each of these deriving its name from tribes that formerly resided there. The Oghuz occupied the right bank of the Danube and the Tatars the left; from there they launched further raids. At that time, a detachment of the army of Barakat Khan passed through Wallachia, traversed the Balkans and advanced towards the Hungarians who sorely defeated the outnumbered Muslims in the region of Mohacz. The old scores were about to be settled. [23]

Here there is a blending of Ottoman and Tatar traditions. They converge geographically at the Danube Delta, north of Babadag. The existing towns of the Bratul Chilia arm of the river in Romania, and Kilija and Ozero Jalpug and Ozero Katlabuch in Moldavia, give some clue to the geographical heart of these legendary and factual jihāds on the fringes of the Balkans.

The feats of Sari Saltik extend beyond the holy places of Islam in the Balkans. They take place in the heart of Catholic Christendom, even within northern Europe, and furthermore his exploits are concluded in the narrative with the last will and testament (waṣiyya) made by him before his death; the last instructions which he gave to his son and to his Ghāzīs. They were to prepare up to seven coffins in each one of these his body would appear. F.W. Hasluck takes up this story:

A certain dervish, by name Mahommed Bokhar, called also Sari Saltik Sultan, who was a disciple of the celebrated Khodja Achmet of Yassi [d. 1166/7 AD] and a companion of Hadji Bektash [d. 1326-60], after the conquest of Brousa was sent with seventy disciples into Europe. In his missionary journey Sari Saltik visited the Crimea, Muscovy, and Poland: at Danzig he killed the patriarch ‘Svity Nikola’ and, assuming his robes, in this guise made many converts to Islam. He also delivered the ‘kingdom of Dobrudja,’ and in particular the king’s daughter, from a dragon: this miracle was falsely claimed by a Christian monk, but Sari Saltik was vindicated by the ordeal of fire and the king of Dobrudja was in consequence converted to Islam. Before his death the saint gave orders that his body should be placed in seven coffins, since seven kings should contend for his possession. This came to pass; each king took a coffin, and each coffin was found when opened to contain the body. The seven kingdoms blessed by the possession of the saint’s remains are given

23. ibid., pp. 77-8. The rivers allegedly crossed by Ibn Baṭṭūṭa would seem to make best sense if they referred to the three main arms of the Danube in the Delta area or to these other waterways in Moldavia. See the article on Babadaghi by Bernard Lewis in the Encyclopedia of Islam.

![]()

154

as (1) Muscovy, where the saint is held in great honour as Svity Nikola (S Nicholas); (2) Poland, where his tomb at Danzig is much frequented; (3) Bohemia, where the coffin was shewn at ‘Pezzunijah’; (4) Sweden, which possessed a tomb at ‘Bivanjah’; (5) Adrianople, near which (at Baba Eski) is another tomb; (6) Moldavia, where the tomb was shewn at Baba Dagh; and (7) Dobrudja, in which district was the convent of Kaliakra containing the seventh tomb’. [24]

In the Ṣaltiqnāme the number of rulers — kings and beys — is increased to a figure of twelve: the Tatar Han and the kings of the Vlachs, Edirne, Bogdan (Moldavia), Russia, Hungary, Granada (in Spain?), Croatia (?) and Poland, although Sari Saltik had stressed that his real or ‘master’ coffin, or sarcophagus, would be at Baba Eski in Thrace. The enhanced number may not be unconnected with the magical number of the twelve Imāms, the twelve letters in the declaration of faith, the confession of the Prophethood of Muḥammad, and the recurrence of this number in so much of the numerical symbolism of the Ḥurūfiyya and the Baktāshiyya. [25] According to Margaret Hasluck, [26] the secret rites once performed by the Albanian Baktāshīs at sunrise and at sundown included the saying of prayers by the bābā, the recitation of the Qur’ān and the lighting of twelve candles for the twelve Imāms on a three-tiered altar. To this may be added further Ṣūfī and Eastern Christian parallels (one recalls the seven angels, seals and churches of Asia in the Book of Revelations). The seven bodies of Sari Saltik recall the notion of the seven abdāl (badal, substitute). Belief in this heavenly hierarchy dates back to the Ṣūfīs of the ninth century. They conceived of the cosmic order as possessing a fixed number of saints at any one time. However, the number varied; Ibn al-‘Arabī (d. 1240) established their number as seven, each corresponding to a prophet — Adam, Moses, Aaron, Idris, Joseph, Jesus and Muḥammad. Each exercised sway over one of the seven climes into which the world is divided. But there are other localities in the Balkans and in Asia Minor that perpetuate the memory of Sari Saltik’s resting-place, including Baba Eski, Iznik, Bor near Niğde in Anatolia, Diyarbakir and possibly other still unidentified or unlocated sites.

24. F.W. Hasluck, Christianity and Islam under the Sultans, vol. 11, p. 577.

25. For probably the most detailed study of the numerical design of the Cabbala of the Hurufī sect, see John Kingsley Birge, The Bektashi Order of Dervishes, London, 1937, 1965.

26. Margaret Hasluck, ‘The Nonconformist Moslems of Albania’, The Moslem World, vol. XV, 1925, pp. 392-3.

![]()

155

Babadag (Babadagh) ‘the mountain of the father’, has remained an important religious centre, in Muslim memory. In the Cairene journal Nūr al-Islām, published by the Mashyakha of al-Azhar (part 10, Shawwāl 1350/1932, vol. 2, p. 741-2) this locality was singled out for special comment:

The Muslims reverence the town of Babadag, on account of the presence there of the tomb (ḍarīḥ) of Sārī Salt? (sic) whom the Muslims consider as a Muslim saint and holy man. It was he who, after having colonised the Dobrudja, began to propagate Islam as far as Lake Ohrid in Albania. Muslim muftīs are represented in four localities in [Romania] Tulcea, Constanta, Silistria and Bazargik [now in Bulgaria]. In Romania there is a madrasa of the highest rank for teachers in the city of Majīdiyya (Medgidja). Among the tekkes, there are three, for the Qādiriyya, the Baktāshiyya and the Shādhiliyya’.

Degrand in his Haute Albanie — published in 1901, though written in 1892 — has one of the most comprehensive accounts of the destruction of a seven-headed hydra at Kalagria in Bulgaria, or at Krujë in Albania by Sari Saltik. His account, owing to its date, has special value. Others draw upon him. Almost every facet of the story — the destruction of the monster with a wooden sword, the rescue of a princess who identifies her rescuer from other suitors by means of three apples, the sojourn of a holy dervish in the cave, his flight by stages on a prayer carpet to Corfu, his forty identical coffins (corresponding to the Abdāl) — are all found. Of particular value is Degrand’s hearsay description of an alleged sarcophagus türbe of Sari Saltik in the mountain overshadowing Krujë. The pilgrim station and the narrative cohere in almost every detail, and furthermore the parallels between the Krujë story and those that mention Sari Saltik’s very similar exploits in Bulgaria or in Romania are well described. Variation and similarity may be explained by a stitching together of folk narrative derived from some Ur-narrative that reflects the Vilāyetnāme itself or its sources. This narrative has been employed to interpret local cults, whether in Romania, Bulgaria or in Albanian regions.

3. Krujë, Sari Saltik and Gjerg Elez Alia in Albania and Bosnia

F.W. Hasluck attributed the various episodes that involve Sari Saltik at Krujë to the Baktāshīs. A similar opinion was held by Ḥasan Kaleši, who gives by far the most comprehensive account of the local Albanian

![]()

156

traditions. [27] Machiel Kiel does not differ, but is cautious about attributing the substance of the Krujë traditions to the Baktāshī order and its dervishes per se. He suggests that the amalgam of Albanian folktale and Saltiqnāme might be accounted for by the presence (already at the beginning of the sixteenth century) of an Ottoman garrison in Krujë [28].

Mark Tirtja emphasises the continuity over centuries in the Krujë traditions. [29] On the mountain of Krujë a pagan rite was once practised. Later a church was built nearby in honour of Saint Alexander — who with Islamisation was replaced by Sari Saltik. Such a sequence of conversion is the norm in Albania on the summits of mountains and in forests, in groves near lakes and by sacred springs. Hasluck noted that at Krujë the dragon — in fact a hydra — lived by day in a cave and at night in a church. The Muslim champion, Sari Saltik, saved a princess in the manner of St George. Later, as a hermit, he lived in this cave until, when his life was gravely threatened by the local people, he made three strides — ‘marked by a footprint and a tekke at each stage’ [30] — that took him to Corfu, where he died. This must be a late development, since in Kiel’s sixteenth-century account Sari Saltik was allegedly buried at Krujë in his mountain shrine. This is where Babinger found the Turkish inscription dated 1104/1692/3. [31]

What looks like a borrowing from Baktāshī folk-epic may in fact be matched by the exploits of heroes in Albania, traces of which may date back to Illyrian times. Mark Tirta shows for example that the local Albanian hero Gjergj Elez Alia (who matches Muyi and Halil in the Albanian North) performs several of the heroic feats and possesses the superhuman powers of Sari Saltik. These must have been present in Christian Albanian heroic narrative centuries before Sari Saltik’s name was known in these districts. The hero and the dragon are closely linked in Albanian tradition.

27. Ḥasan Kaleshi: ‘Albanische Legenden um Sari Saltuk’, Actes du Premier Congres International des Etudes balkaniques et Sud-Est Européennes, vol. VII, Sofia, 1971, pp. 815-28.

28. Personal communication from Dr Kiel.

29. The subject is fully discussed in his ‘Survivances religieuses du passé dans la vie du peuple (objects et lieux de culte)’, Ethnographic Albanaise (Tiranë) 1976, pp. 49-69. A Marxist attitude is displayed throughout.

30. F.W. Hasluck, ‘Ambiguous Sanctuaries and Bektashi Propaganda’, Annual of the British School at Athens, no. XX, session 1913-14, London, p. 111.

31. On the mountain shrine and its tekke, see Nathalie Clayer, L’Albanie pays des dervishes, op. cit., pp. 336-9.

![]()

157

Both possess heroic and liberating virtues. However, the seven-headed hydra (possibly a symbol of a primeval matriarchy), which is slain by the hero and is in fact the ‘dragon’ in most of the Sari Saltik stories, though sometimes a monster of the sea, symbolises the fight of the Albanians against their enemies. The dragon-heroes have seven hearts, and it is hard not to perceive some connection between this and the seven coffins, each containing the mortal remains of Sari Saltik (later changed to twelve or forty). The Albanian hero casts the slain body of the monster into a well or into the sea — exactly what occurs in the stories at Krujë. The hydra’s body is thrown to Lezhë (a shrine of Skanderbeg), the dragon and the hero, according to Mark Tirta, being one and the same. ‘Some who are scientific have seen in the combat of Gjergj Elez Alia against the monster of the sea, the fight of the dragon against the hydra kuçedër.’ [32] The dragon is born in order to fight hydras, and he defends extended families which compose the community. He has wings beneath his arm-pits, and his weapons include the post around which the mill-stone revolves. He uses the great trees of the forest to fight the hydra; these may be compared with the wooden sword of Sari Saltik. The hero is aided by the fairy Zanës who are often forest-Amazons. They serve the patriarchal order and — like the Orös, the fairies of fate, destiny and luck — guard the family and the tribe. The Zanë or Xinë is also the mountain fairy, the muse of heroes. These two fairies between them are like the ḥūriyya, and the jinniyya even more, in pre-Islamic Arabia.

The Bosnians have their own epic traditions about their Alija Djerzelez (also of Budalina Tale), whose name is almost identical with that of the Albanian hero. His exploits are especially associated with the district of Sarajevo, and with the illustrious Ghāzī, Husrev-Beg. According to Vlajko Palavestra: [33]

Alija Djerzelez, a well-known hero of Moslem epic poetry and a notable personage of the folk tradition, was, in the view of contemporary historians, an actual person. He was a warrior and hero of the Bosnian borderland. In reports concerning the Krbavska Battle [1493] an anonymous Turkish writer from the beginning

32. See the important article by Mark Tirtja, ‘Des stratifications mythologiques dans l’épopee légendaire’ in Culture Populaire Albanaise, Year 5, Tirane, 1985, pp. 91-102.

33. Vlajko Palavestra, op. cit., pp. 63-4. These passages are selected from a chapter on Alija Djerzelez (V: ‘Warriors and Heroes’), and other Bosnian heroes. It is told in Sarajevo that the Serbian hero, Kraljević Marko became the blood brother of Alija Djerzelez because they had both dreamt the same dream and went out into the world in search of one another. From being bitter enemies they became loyal allies.

![]()

158

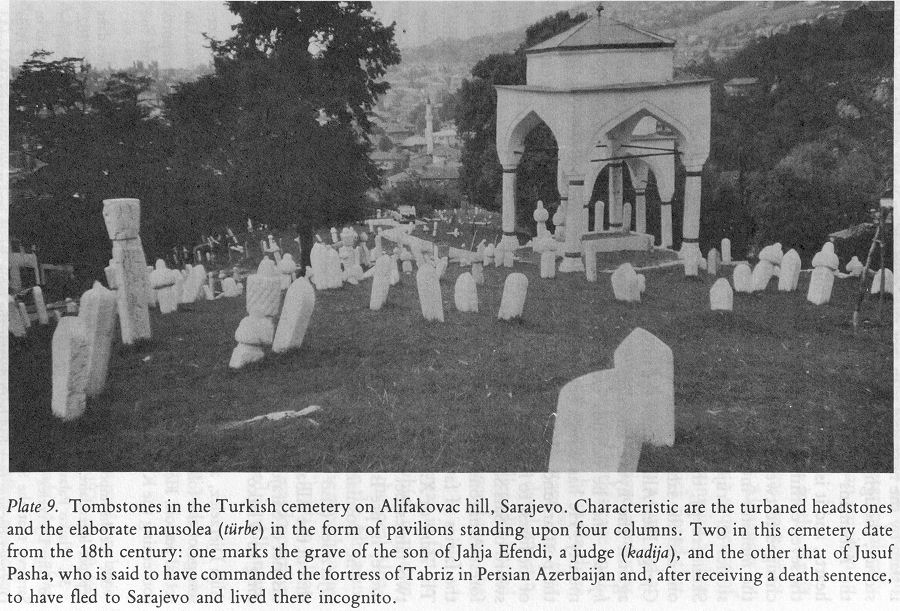

Plate 9. Tombstones in the Turkish cemetery on Alifakovac hill, Sarajevo. Characteristic are the turbaned headstones and the elaborate mausolea (türbe) in the form of pavilions standing upon four columns. Two in this cemetery date from the 18th century: one marks the grave of the son of Jahja Efendi, a judge (kadija), and the other that of Jusuf Pasha, who is said to have commanded the fortress of Tabriz in Persian Azerbaijan and, after receiving a death sentence, to have fled to Sarajevo and lived there incognito.

![]()

159

of the 16th century mentions a certain Gerz-Iljas, whom a commentator links with the epic Djerzelez. In a Turkish census defter [administrative register] of 1485, a timar [feudal property] of Gerz-Eljaz is recorded for the nahija [small administrative area] of Dobrun near the town of Višegrad. The famous hero, Gerz-Iljas, is also mentioned in the long account written by the Turkish historian, Ibn Kemal [1468-1534] of the fighting in the Bosnian borderland in the years 1479 to 1480.

The hero is linked to the battles fought by Ghāzī Husrev-Beg against his enemy, the armies of the alliance between the Hungarians, the Croatian, Ban Ladislave, of Egervar, Peter Doczy and Vuk Grgurević, the Serbian, who led a counter-offensive against Sarajevo in 1480. Ghāzī Husrev-Beg was rescued from defeat by an unknown warrior on a winged horse:

Some time later Husref Beg returned home with his army. When he went to his house, his wife asked him how he had fared. Husref Beg told her that things would have ended ill and the battle been lost, if an unknown warrior on a winged horse had not appeared, scattering and cutting down before him with his scimitar the entire army of Vuk Jajcanin. When they wounded me in my arm, Husref Beg said, that hero bound my wound with his scarf. There it is still, in my saddle-bags! His wife dashed to see, and, taking the scarf from his saddle-bags and examining it carefully, said, My God, I know whose scarf this is! I gave it to our servant Alija. And I know that these two days, when we have had the most work to do, when we have been threshing, he has not been here. Husref Beg quickly ordered that Alija be brought before him. Alija came, the same old Alija, seemingly wretched and dejected, but Husref Beg leapt to his feet, went to him, and sat him on the cushion beside him. Alija, he said, so many years you have served me and I have become indebted to you. I should pay you off, you should no longer be my servant. You are a greater hero than me! And, truly, he paid Alija well and bade him farewell.

From this moment onwards Alija began to wander the world and fight with the greatest heroes. They say that this is where his name originated, for Djurzelez means the warrior with the mace, or mace-wielder.

Vlajko Palavestra writes:

Until recently there were in Sarajevo those living who could remember a hollow elm tree at Klokoti near the town of Kiseljak, which Alija Djerzelez had struck with his mace while pursuing Vuk Jajčanin. There were until recently marks in the wall at the base of the minaret of the Ulomljenica mosque which were believed to be the fingerprints of Alija Djerzelez.

Various songs were sung and stories told about the death of Alija. Some said that he was killed at Gerzovo Polje near the town of Mrkonjić, in the rebellious Krajina, by Vuk Jajčanin himself. They say that he caught Alija at prayer, crept up

![]()

160

on him and cut him down with his sword. Although Alija realized that he would be killed he did not want to interrupt his prayer. One of the songs records that Alija was killed on mount Romanija by a haiduk [outlaw] named Sava of Posavlje, but this is highly unlikely. One should tell the truth even though it is not easy to discover it.

At Gerzovo Polje there is, still today, a türbe [mausoleum] beneath which, it was believed, Alija Djerzelez was buried (Plate 8). People would visit that türbe even from afar, especially on Alidžun (Ilindan) (St Elia’s Day, August 2) to commemorate this great hero. Old people used to say that the mace of Alija Djerzelez was preserved in Sarajevo in the tekija of the Seven Brothers, but that once, when Sarajevo was on fire, the mace was destroyed.