6. BALKAN MUSLIMS IN THE HISTORY OF THE MAGHRIB, EGYPT AND SYRIA, AND THE INFLUENCE OF THE ARAB EAST IN THE COURTLY LIFE OF ALI PASHA OF TEPELENË

‘Pan-Islamism has always come from the very heart of the Moslem peoples, nationalism has always been imported. Consequently, the Moslem peoples have never had ‘aptitude’ for nationalism. Should one be distressed by that?’ (Alija Izetbegović, The Islamic Declaration)

1. Albanians and Bosnians in Algeria and Tunisia 201

3. Albanians and the Cairene Baktāshī tekkes 211

4. The history of Shaykh Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā and Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā 218

5. al-Hājj ‘Umar Luṭfī Bashārīzī 227

The Albanian and Bosnian communities in the Arab world, especially in recent times, were both influenced by, and made their own mark on, the history and the cultural life of the Maghrib, particularly Algeria and Tunisia, and on the life of Egypt, Syria and Lebanon. At the same time members of these communities were the agents of a continuous transmission of Middle Eastern Islamic culture, language and literature into the heart of the Balkans. Trends in Islam, the vicissitudes of Ṣūfīsm, the effort of the Arabs to achieve independence from the Turks or the West, were echoed or reflected within the towns, villages and citadels of Islam in the Balkan peninsula. The Balkan languages themselves, especially Albanian, illustrate this borrowed phenomenon.

An example of the borrowed influence exerted within the Balkans from Egypt and Central Asia in an earlier age can be seen in what is today Greek Macedonia, including such cities and towns as Yenice Vardar, Larissa, Salonika, Serres, Kavalla and Arta. The first of these cultural circles at Yenice Vardar was within a small sophisticated group and particularly among its lettered elite. It reveals the way the Ṣūfīs there were to transmit Egyptian and Persian influences within the interior of Macedonia. Machiel Kiel [1] has pointed out that in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries this Macedonian city, in its crucial central location, was essentially Turkish, though surrounded by a mixed

1. See M. Kiel, ‘Yenice-i-Vardar (Vardar Yenicessi Giannitsa): A forgotten Turkish cultural centre in Macedonia in the 15th and 16th centuries’, Stadia Byzantina et Neohellenica, 3, Leiden, 1971, reprinted in Studies on the Ottoman Architecture of the Balkans, Aidershot: Variorum, 1990, IV, pp. 308-16.

![]()

196

Turkish and Christian population, chiefly Bulgarian. It was an important Islamic cultural centre, noteworthy for its literary intelligentsia. Three of its members — Shaykh ‘Abdallāh al-Ilāhī, Shaykh Shams al-Dīn al-Bukhārī and the Ṣūfī poet Uṣūlī, — illustrate the unbroken relationship between Yenice, their home town, and Istanbul, Egypt and Persia at that time.

Shaykh ‘Abdallāh was born in Anatolia. However, his earlier years were partly spent in Samarqand, where he was accepted into the Naqshabandiyya Ṣūfī order. He then moved to Istanbul, where he became a professor in the Molla Zeirek madrasa. He actively propagated the Naqshabandiyya order, ably supported by Shaykh Shams al-Dīn al-Bukhārī, who was originally from Bukhara in Central Asia. The two men had met in Samarqand. Shaykh ‘Abdallāh al-Ilāhī’s reputation and devotion to the Naqshabandiyya earned him a measure of support among the citizens of the expanding Turkish urban communities in the Balkans. When he died in 1491, communities that followed his teaching had been founded in Macedonia and beyond, including Sofia. To the north such communities were to be observed in Skopje and in Bitolj, the hub of Balkan routes and a key centre for secondary contact within the Albanian interior. As Dukagjin-Zadeh Basri Bey has remarked: ‘Every road leads to Rome. In Albania-Macedonia one says “every road leads to Monastir [Bitolj]”. Monastir-Korça, Monastir-Elbasan, Monastir-Dibra form the hyphen that joins together the mass of southern, central and northern Albania.’

At this time, the Ṣūfī poet Uṣulī was born in Yenice Vardar. He moved to Egypt, which in that period had become a centre for several Ṣūfī orders.

As we have already seen, the last major Circassian Mamlūk ruler, Qānṣawh al-Ghawrī, had commercial and diplomatic contacts not only with the spice entrepots of the Orient but also with Ragusa and its merchants, whose fleet rebuffed the Portuguese and who had a marked sympathy for certain of the Ṣūfī orders, one or two of which bordered on heterodoxy. The orders were favoured during his reign. According to Muḥammad b. Aḥmad Ibn lyas, describing events before the Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1516, [2]

On the Sultan’s departure from Aleppo he went to Hailan and halted there . . . the Sultan said the morning prayers, mounted and proceeded to

2. Lieut.-Col. W.H. Salmon, An Account of the Ottoman Conquest of Egypt in the Year AH 922 (AD 1516), Oriental Translation Fund, New Series, vol. XXV, Royal Asiatic Society, London, 1921, pp. 41, 59, and 84.

![]()

198

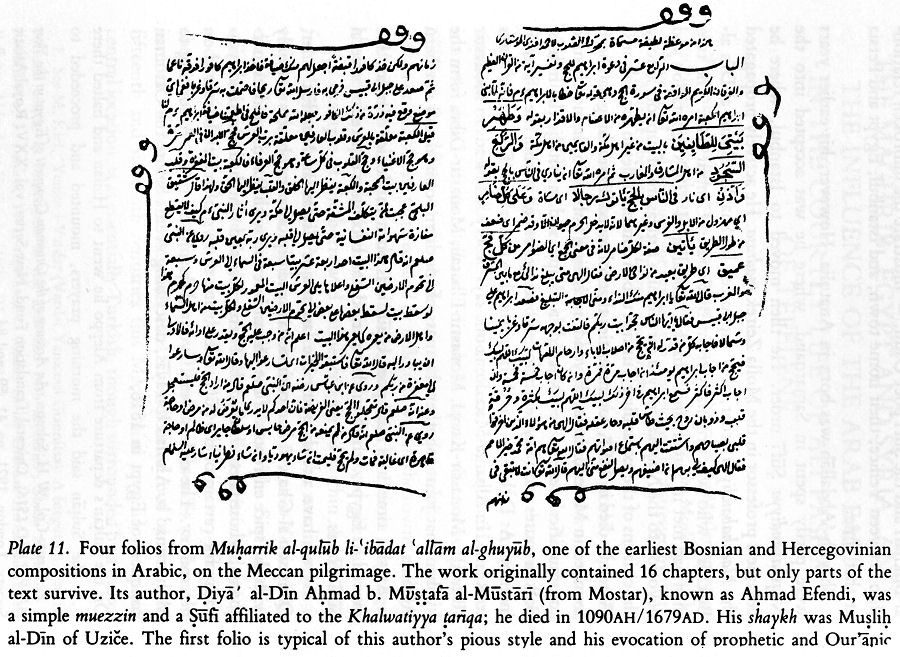

Plate 11. Four folios from Muḥarrik al-qulūb li-‘ibādat ‘allām al-ghuyūb, one of the earliest Bosnian and Hercegovinian compositions in Arabic, on the Meccan pilgrimage. The work originally contained 16 chapters, but only parts of the text survive. Its author, Ḍiyā’ al-Dīn Aḥmad b. Mūṣṭafā al-Mūstarī (from Mostar), known as Aḥmad Efendi, was a simple muezzin and a Ṣūfī affiliated to the Khalwatiyya ṭarīqa; he died in 1090AH/1679AD. His shaykh was Muṣliḥ al-Dīn of Uzice. The first folio is typical of this author’s pious style and his evocation of prophetic and Our’anic

![]()

199

recommendation of the duty of the hajj, citing Abraham for an example, and strengthening his argument and his case by seemingly fabulous reports of pilgrims and accounts of the undoubted blessings they received in consequence. The work refers to holy sites and localities in and around Mecca and Medina, and the significance of the performance of certain rites at certain seasons. The fragments of this work were preserved in the Gazi Husrev Library, Sarajevo, which recently suffered damage and destruction.

![]()

200

Zaghzaghin and Tell al-Far, where the alleged tomb of the Prophet Dā’ūd is. [ . . . ] He there mounted his charger, wearing a light turban and a mantle, carrying an axe on his shoulder; [3] he inspected the army in person; on the right wing was the Amir of the Faithful, also wearing a light turban and mantle . . . carrying an axe on his shoulder like the Sulṭān, and having over his head the Khalīfah’s banner. Around the Sulṭān, borne on the heads of a body of nobles, were forty copies of the Ḳor’ān in yellow silk cases; one of the these copies was in the handwriting of Imām ‘Othmān Ibn ‘Affān. There were also round him a body of dervishes, among whom was the successor of Seyyid Ahmed al-Bedawī founder of the Ṣūfī sect accompanied by banners. There were also the heads of the Ḳādiriyyeh sect with their green banners, the successor of Seyyidī Aḥmed al-Rīfa‘ī with his banners, and Sheikh ‘Afīf al-Dīn, attendant in the mosque of Seyyidah Nefisah with black banners.’

Ibn Iyās adds that ‘he had a great belief in the dervishes and the pious’. [3] However, even more significant, was the fact that he was inclined to ‘the Nasīmiyya’, and its beliefs, and that this preference was strengthened by his liking for foreigners and the stimulus of men from Iran and from the Caucasus and Ṣūfīs from those regions. Massignon spotted this fact. ‘The Turcoman sect of the Ḥurūfiyya, persecuted simultaneously among the Tīmūrids, the Osmanlis and the Mamlūks of Egypt survived among the Turks of Egypt and Anatolia thanks to the poetry of Nasīmī, which Sultan Qānṣūh al-Ghawrī admired.’ [4]

It was not only the appeal of the poetry of Nasīmī (d. 807/1404), the gnostic follower of the epiphanic and theophanic teacher and thinker Faḍlallāh of Astarābād, with poetic reflections and disclosures of the divinity in the physical form and facial features and members of man, but also the complex Qur’ānic cabbalistic schemes that were, in some respects, more typical of the founder-master than of Nasīmī, his chief disciple. Much of the speculative and the magical Ṣūfīsm was to be seen in the esoteric teaching of the first Khalwatī dervishes and men of letters who came to Egypt in the reign of Qānṣawh al-Ghawrī, especially Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Demirdāsh (‘iron-stone’) Shāhīn al-Khalwatī and Ibrāhīm b. Muḥammad Gülshenī. Uṣūlī was initiated into his order and remained in Cairo until his master’s death in 925/1528, when he returned to Macedonia, dying in poverty there in 1538. Imitating Nasīmī’s style, UsuiTs verse is marked by its Ḥurufī content,

3. On the type of axe described, see F. de Jong, ‘The iconography of Bektashiism’, Manuscripts of the Middle East, vol. 4, 1989, p. 21, and the details furnished in his article.

4. Louis Massignon, The Passion of al-Hallāj, Mystic and Martyr of Islam (transl. Hubert Mason), vol. 2, The Survival of al-Hallāj, Princeton University Press, 1982, pp. 253-4.

![]()

201

which the poet seems to have studied and absorbed in Cairo — not, however, through any schooling that emanated from the Baktāshiyya, which was destined to become the principal depository of such Ḥurūfīsm, but through the Gülsheniyya which was only one among other sub-orders that had also accepted Fadlallah’s speculations and saw their secret propagation as a duty. Uṣūlī’s death did not sever this connection between Cairo and Macedonia, since Sinecak of Yenice Vardar went to Cairo later in the sixteenth century and was initiated into the order of Ibrāhīm Gülshenī. He then performed the Meccan pilgrimage, and travelled extensively in Arabia and Persia before returning to Thrace. He was an acknowledged master of Arabic and Persian as well as Turkish.

1. Albanians and Bosnians in Algeria and Tunisia

At the time when the Ottomans established their rule in Egypt, three Levantine adventurers from the island of Lesbos established their power on the Barbary coast. Of these ‘Arūj, whom G. Yver, in his article on him in the Encyclopedia of Islam, suggests was the son of a Turkish captain, or a Greek or Albanian renegade, had been first favoured by an Egyptian prince following his captivity and escape from a galley belonging to the Knights of St John at Rhodes. [5] At the beginning of the sixteenth century, accompanied by his brothers Isḥāq and Khayr al-Dīn, ‘Arūj arrived in Tunis with a strong religious motivation for launching a jihād based on an Islamic state superimposed on effete Berber principalities in the western Mediterranean. The dreams of ‘Arūj were of wide extent. He conceived of attaining political sovereignty for his brethren within the central Maghrib, as far as Tilimsān.The menace of Spain spurred him on to his goal, although death at the hands of an expeditionary force, despatched by the future Charles V, put paid to his own and his brother Isḥāq’s ambitious endeavours. Khayr al-Dīn, in Algiers, was to replace him and he decided to seek the protection of Sulṭān Selīm. Algiers became an Ottoman frontier province and the Sultan sent 2,000 Janissaries and 4,000 other Levantines who were enlisted into the Algerian militia. These Janissaries were to form the backbone of resistance against the Spaniards and spearhead Turkish

5. On ‘Arūj and his brothers and their origins, see John B. Wolf, The Barbary Coast: Algiers under the Turks, 1500 to 1830, New York and London, 1979, p. 64, and Corinne Chevallier, Les trente premières annees de l’état d’Alger, 1510-1541, Algiers: Offices des Publications, 1986, pp. 26-36.

![]()

202

conquests deep into the Maghrib. The corps of the Janissaries was to provide the garrison into which groups of Turks, Albanians and Bosnians were absorbed, along with renegades, in this region of North Africa. It seems likely that the first 2,000 men were largely the offspring of Balkan Christians who had been taken from their homes as devshirme. Other recruits, who were to outnumber them, were probably landless Anatolians. The Janissary corps was extremely mixed in origin and was to be enlarged by numbers of renegade Christians.

Indeed North Africa was to attract numbers of Levantines, unemployed Rumelians and Anatolians, some of them peasants as well as renegades, who in aggregate formed a community superficially not unlike the ‘Ṣaqāliba' (Slavs) as an ethnic notion so defined in the Middle Ages by the Arabs in Spain and elsewhere.

According to J. Pignon, at the end of the sixteenth century the Spanish monk Diego de Haëdo, a slave in Algiers, noted the considerable number of Turks entering Barbary to seek their fortunes, like the Spaniards in Peru. Slavago, in his turn, has shown us how they abandoned their native hovels and their ploughs as they crowded into Barbary to enable themselves, for there they could found a household by marrying a Moorish woman and see their sons succeed them in the militia. He says that there was always someone waiting in the ports of More or in the islands of the Aegean, in Adalia, Cyprus or Cairo, for a boat to arrive which could carry him to Barbary.

However, the Turks of the Levant were not the only ones to appreciate these advantages. How much greater was the allure of the force of Janissaries for the numerous renegades living in Tunis; young captives converted in their childhood despairing of ever purchasing their freedom, or compelled by circumstances to renounce their faith — or even adventurers renouncing it voluntarily for the sake of their careers. The renegades, mostly from the coasts of Italy and Provence, were very numerous among the Janissaries and were certainly the most active. In 1682, during the conflict between Tunis and Algiers, out of thirteen leaders selected by the Divan to ensure that the town was well guarded and the troops properly led, twelve, including the commanding general were renegades. [*]

After 1568, Muḥammad Pasha decreed that Janissaries could go to sea with the corsairs and that Levantine and renegade marines could join the militia.

*. Jean Pignon, Les Cahiers de Tunisie, 15, Tunis, 1956, p. 307.

![]()

203

The latter was organised as in Tunis [6] in the ascending ranks. At the bottom was the joldac (yoldash, ‘comrade’ or private), then adabuch (sergeant), boulouk-bachi (captain) and at the top agha (commander). Janissaries married local women, and their offspring, the Coulougli (Kul-Oughlu), were to become an element of the population, among whom familial memories of Anatolian, Bosnian and Albanian ancestry and wider Balkan tribal connections were preserved and cherished, and have continued to be down to the present in the major cities of Algeria and Tunisia. [7] It is noteworthy that the offspring of merchants, pashas and men of religion are also included within this small community.

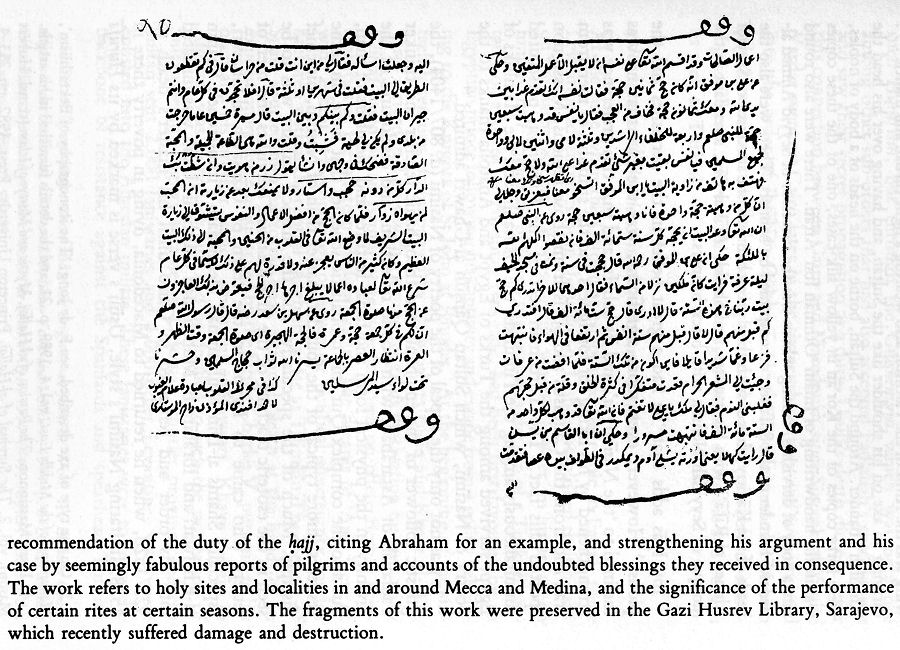

Algiers was to remain one of the most important North African cities where Balkan Muslims were to live, especially in the originally Berber district of Beni Mezerna, alongside Spaniards, Catalans, Maltese, Sardinians and more northerly Europeans. The spiritual heart of Algeria for the Janissary corps was the mosque that is still known as al-jāmi ‘al-jadīd (the ‘new mosque’, later la mosqueé de la pêcherie). Built in 1660 on the site of the madrasat Bū ‘Inān, it was the one Ḥanafī mosque in Algiers city, and was built solely for the non-indigenous population in Algiers, the Turks and the Kul-Oughlu population. Its cruciform plan reflects the influence of the Ottoman East. It is one of the few of its kind in Algeria, although there are examples in Tunis. The mosque of Ṣāliḥ Bey, in ‘Annāba, Algeria, built in the eighteenth century, is crowned with a pencil-like Salonica-style minaret that is unique in Africa outside Egypt and Libya, and its interior is graced by decoration around its prayer-niche (miḥrāb) in the style of Ottoman floral and decorative tiling that also exists in palaces in Algiers city.

Certain Janissaries of Balkan origin are listed in the registers of salaries preserved in the Turkish archives in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Algiers [8]. Composed in 1702 in the time of the Dey Muṣṭafā,

6. For the Janissaries in Algiers, see H.D. de Grammont, Histoire d’Alger sous la domination turque (1515-1830), Paris, 1887. For an account of the Janissaries in Tunis, see Jean Pignon, ‘La milice des Janissaires de Tunis au temps des Beys (1590-1650)’, Les Cahiers de Tunisie, 3me trimestre, no. 15, Tunis, 1956, pp. 301-26.

7. Albanian families still have descendants in the principal cities. The Bosnian community is particularly associated with Algiers (the shrine of Sīdī ‘Abd al-Raḥmān is frequently visited by women of Bosnian origin) and with Tlemcen (Tilimsān).

8. Details are given in J. Deny, ‘Les registres de solde des Janissaires conservés à la Bibliothèque Nationale d’Alger’, Revue Africaine, nos 304-5, 1920, pp. 19-46 and 212-60.

![]()

204

Plate 12. The ‘New Mosque’ (al-jāmi ‘al-jadīd, or mosquée de la pêcherie), the only Ḥanafī mosque in Algiers, specifically built in 1660 for the Turks, the Kul-Oghlu, and the Bosnian and Arnaut population, and members of the Janissary corps in the city. Its plan and design reflect Ottoman influences.

by the hand of al-Ḥajj Muṣṭafā Dā‘ī, they describe the serving or departed members whose names follow as ‘dervishes of Sulṭān Ḥājjī Baktāsh Walī, may Allāh sanctify and illuminate his tomb until the Day of Religion’. The Janissaries are listed according to rank and are sometimes identified within the 400 or more units (called odjaq) by their town of origin and their profession. All principal barracks are included: their inhabitants were ethnically mixed, but a few Balkan Muslims were listed among them:

![]()

205

Bābā ‘Azzūn barracks: no. 1, Arna’ūṭ Sha‘bān, Sha‘bān, ‘the Albanian’.

Ṣāliḥ Pasha barracks: no. 23, Veli (Walī) Dede. This name recalls a ‘marabout’ who was first of all chief cook at the Mevlevi tekke of Pera, and then became the Mesneviḥān in 936/1529-30. He later went to Algiers and died in 955/1548-9. There is a convent dedicated to Veli Dede in the village of Goeldjuk (Tavchjanli district, near Gallipoli).

No. 24, Qalābaq, a Janissary from Qalabaqa, a town in Thessaly, north of Trikkala.

Eski barracks: no. 3, Arnaghūdlar, ‘the Albanian’.

No. 4, Istankūlī, ‘the man from Kos or Tanco’.

No. 23, Qāzdāghlī, from the vicinity of Mount Ida, in the region of Troy.

While at times the Albanian Janissaries in Algiers were, as elsewhere, a very troublesome element in the population of Algiers, and in the eighteenth century mounted an unsuccessful coup during the rule of Bābā Muḥammad Torto, [9] in the sixteenth century they played a positive role in combating the Spaniards and administering the city. Also, together with Moroccans, Turks and Serbs, they established a foothold in Montenegro that was to last for centuries.

In the sixteenth century, one or two beylerbeys in Algiers were of Albanian birth. It is recorded that King Philip II, while in England in 1557 to visit Mary Tudor, wrote letters to Ra’īs Dragut and to Qā’id Muṣṭafā Arnā’ūt on hearing news of the death of Muḥammad Pasha, Āghā of the Janissaries. This Muṣṭafā was chosen as his successor. During the rule of Hasan-Veneziano (1577-80), who made many destructive raids on the Spanish coast, Cervantes was taken captive by Ra’īs Mami Arnā’ūt, whom the author of Don Quixote describes as large yet thin and pale, with a ruddy though sparse beard and burning eyes, a man both cruel and brave and endowed with boundless energy.

A decade later, the fourth beylerbey, in succession to Khayr al-Dīn, ‘Ulj ‘Alī Pasha, died. In 1569, he had taken advantage of the uprising of the Moriscos in Spain to capture Tunis from the Spaniards. Although its first recapture proved short-lived, it was decisive in the long term since in 1574 ‘Ulj ‘Alī again seized Tunis, together with La Goletta, thereby ending Spanish control and influence. This great man was responsible for major building projects in Algiers, including an extension to its harbour, and he had dreams of digging a canal between the

9. On the revolt of the ‘Arnaouds’, see Venture de Paradis (presented by Joseph Cuoq), Tunis et Alger au XVIIIe siècle, Paris: Sindbad, 1983, pp. 217-20. There is a detailed description of Janissary life in Algiers on pp. 159-95.

![]()

206

Mediterranean and the Red Sea in order to extend Ottoman maritime power in the East. Specifically for the Balkans, it was he who, perhaps more than any other North African ruler, established a corsair foothold in the peninsula of Ulcinj, today the most south-easterly point of Montenegro. This town had been subject to Arab attacks since the eighth century and was held by them for two centuries, after which it passed into the hands of the Slavs. Then in 1571 it was captured by ‘Ulj ‘Alī, ally of Selīm II during the war of the latter against Venice. Until 1878 the port remained a haven for corsairs, who extended their influence northwards towards Bar and the Rumije range. It was garrisoned by Moroccans, Algerians, Albanians and Turks.

Ulcinj was to become an important harbour for landing slaves from Black Africa. Some intermarried with Albanians and became an important major element in the town, and a tiny remnant of their descendants survived. Trade in slaves continued under the Montenegrin flag as late as 1914, and the names of several sea captains who brought negro slaves from Tripoli and elsewhere on the North African coast have been recorded. Some of these slaves, referred to as 'Arap’, were from the region of Bagirmi near Lake Chad. They spoke Arabic and retained a memory of some Sūdānic vocabulary.

Alexander Lopašić, who has made a detailed study of the descendants of freed slaves in Ulcinj district, writes:

The Ulcinj Negroes have been and still are Mohammedans by faith. Their women have always hidden and still hide their faces and decline to give up that custom. According to information which I received from the Albanians of Ulcinj, some customs of the Ulcinj Negroes are apparently either of Arab or African origin, since they are not Albanian. For example, trousers were not allowed to be left near the bed because otherwise the owner would dream while sleeping. This custom was told me by Rizo Brashnye who himself had it from his father and still observes it. He was further told by his father that if he wanted to do harm to a person he must appear in the dreams of that person. If a person appears in the dreams of another, the dreamer has only to turn the pillow over and then he himself will appear in the dream of the former one and then he will remain undisturbed. It is still remembered that Negroes brought to Ulcinj had scars on their faces indicating their tribes. Two scars indicated the town dweller, while one scar was the sign of people living in the country. It is known that Abdula Brashnye had two scars and Mohammed Shurla only one scar across the face. Negroes without scars on their faces were considered to be of lower rank. [10]

10. Alexander Lopasić, ‘A Negro Community in Jugoslavia’, Man, vol. LVIII, Nov. 1958, p. 171. Links between Ulcinj and Algiers are discussed in Muḥammad Mūfākū, ‘Al-Thawra al-Jazā‘iriyya fi’l-shi‘r al-Albānī’, in Malāmiḥ ‘Arabiyya Islāmiyya fī’l-adab al-Albānī, Damascus, 1990, op. cit., pp. 93-5. Two further, studies are Đurdica Petrović, ‘Crni u Ulcinju’, in Etnolški Preglad, 10, Cetinje (Montenegro), 1972, pp. 31-6 and Tih R. Djorjevic, ‘Negri i našoj zemlya’, Glaznik Skopsoj Naučnoj Društva, pp. 303-7.

![]()

207

Ulcinj was not devoid of a certain intellectual and cultural life. This continued till late in the Ottoman age (as it did in adjacent Stari Bar). For a time in the seventeenth century it was the place of banishment for the messianic Jewish leader, Shabbetai Zevi (1626-76):

Although they were still very strong in the Balkans and Asiatic Turkey, the Shabbateans were gradually driven underground but were not actually excommunicated. The borderline between the apostates and those who remained Jews sometimes became blurred although the latter were generally noted for their extremely pious and ascetic way of life. Shabbetai Zevi himself, who enjoyed the sultan’s favour, formed connections with some Muslim mystics among the Dervish orders. Letters between his group and the believers in North Africa, Italy and other places spread the new theology and helped to create an increasingly sectarian spirit. After a denunciation of his double-faced behaviour and sexual license by some Jews and Muslims, supported by a large bribe, Shabbetai Zevi was arrested in Constantinople in August 1672. The grand vizier wavered between executing or deporting him, but finally decided to exile him, in January 1673, to Dulcigno in Albania, which the Shabbateans called Alkum after Proverbs 30:31. Although allowed relative freedom, he disappeared from public view, but some of his main supporters continued their pilgrimage apparently disguised as Muslims. [11]

The town was the birthplace of Hafez Ali Ulqinaku (1835-1913), author of a large Turkish-Albanian/Albanian-Turkish dictionary, written in the Arabic script (1897), and of a mawlūd (poem in praise of the Prophet), published in Istanbul around 1878. Tiranë’s Biblioteka Kombetare contains a copy of an Arabic work entitled Jalā’ al-qulūb, by Isḥāq b. Ḥasan al-Zajānī, copied in 1224/1808 in Ulcinj.

Though ruined by earthquake and culturally decayed, Ulcinj is one of the best examples, at least in Yugoslavia, of a district that has maintained over a long period those links that have connected the Balkans with Istanbul and the maritime cities of North Africa. However to the Albanians, who have long regarded it as an integral part of their homeland, the town has inspired, in at least one of its men of letters, a spirited defence. The lyric poet Filip Shiroka (1859-1935, pseudonym Gegë Postripa), who lived most of his active life in exile, first in Egypt and later in Lebanon, working as a railway engineer, wrote verses

11. Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 14, 1972, pp. 1220-54.

![]()

208

entitled in Italian All’ Albania all’ armi (Albania take up arms) praising the struggle to defend Ulcinj from Montenegrin assaults that took place in 1880. The town was therefore notable for more than merely having once been a nest for North African corsairs.

2. Albanians in Egypt

Egypt is the most important Muslim country, after Turkey, with which the Albanians have had long and close contact. This was natural since the Albanian founder of modern Egypt, Muḥammad ‘Alī, [12] was intensely proud of his Arna’ūṭ origins. He arrived in Egypt as a young officer with the Albanian detachment in the Turkish expeditionary force. He looked fondly towards his home town of Kavalla in Macedonia, and seemed always to breathe some distant fresher mountain air beyond it, so that when he received Mr Barker, a former British Consul General in Egypt, at Alexandria in November 1826, he allegedly remarked: [13]

‘I will tell you a story: I was born in a village in Albania, and my father had ten children, besides me, who are all dead; but while living, not one of them ever contradicted me. Although I left my native mountains before I attained to manhood, the principal people in the place never took any step in the business of the commune, without previously inquiring what was my pleasure. I came to this country an obscure adventurer, and when I was yet but a Bimbashi (captain), it happened one day that the commissary had to give each of the Bimbashis a tent. They were all my seniors, and naturally pretended to a preference over me; but the officer said, ‘Stand you all by; this youth, Mohammed Ali, shall be served first. And I was served first; and I advanced step by step, as it pleased God to ordain; and now here I am.’

Albanians viewed the triumph of Muḥammad ‘Alī with pride.

12. This modernising autocrat is seen by P.J. Vatikiotis not as a nationalist but as ‘simply a Muslim ruler whose conceptions about society and the relations among men were basically religious, with a strong instinct for domination and command’ (The History of Modern Egypt: From Muḥammad Ali to Mubarak, London, 1991, pp. 68-9).

13. Cited in James Augustus St John, Egypt and Muḥammed Ali, or Travels in the Valley of the Nile, London, 1834, vol. 1, p. 543. An interesting study of Muḥammad ‘Alī as a man of vision is Anouar Abdel-Malek, ‘Moh’ammed ‘Ali et les fondements de l’Egypte indépendante‘, in Les Africains (Charles-André Julien, Magali Morsy, Cathérine Coquéry-Vidrovitch and Yves Person), vol. V, Paris: Jeune Afrique, 1977, pp. 231-59. There is a photograph of Muḥammad ‘Alī’s boyhood home at Kavalla in Greek Macedonia on p. 243.

![]()

209

M. Edith Durham, in her The Burden of the Balkans (London, 1905, p. 44), remarks:

Mustaffa Bushatli, Pasha of Skodra, the chief ruler in North Albania, then thought, as other people were obtaining recognition of freedom, it was a good opportunity for him, to strike. Albanian power at this moment was very great. Mehemet Ali an Albanian, had made himself master of Egypt, and threatened daily to yet further curtail the Sultan’s power. It is said that he not only encouraged Bushatli to rise, but supplied him with funds.

Again, on page 77, she comments on an Albanian who hated all the English that ‘he knew all about them, for he had lived ten years in Egypt. Had it not been for the English influence Mehmet Ali would have ruled the Turkish Empire and all would now be Albanian.’

This was an age when Albanians and Bosnians were posted to garrisons within the Nile regions, and [14] furthermore the bulk of the Albanian troops were uncultured, exceedingly unruly, and often hated. Yet the dynasty that Muḥammad ‘Alī established, the affection it had for Albanians and received from them, and the haven it afforded to them as exiles from Ottoman control, victimisation by Greek neighbours, or the sheer misery of Balkan poverty, meant that in time Alexandria, Cairo, Beni Suef and other Egyptian towns would harbour Albanians who organised associations, published newspapers and above all wrote works in verse and prose that include significant masterpieces of modern Albanian literature. Within al-Azhar and the two Baktāshī tekkes in Cairo, Qaṣr al-‘Aynī and Kajgusez Abdullah Megavriu, Albanians and Balkan contemporaries were to find inspiration for a mystical quest, and artistic and literary stimulus, that sent ripples, as on a pond, throughout Albanian and Egyptian circles in Cairo and distantly and remotely in towns of Albania, Kosovo and Macedonia.

Some of the outstanding literary figures of modern Albanian literature — for example, Thimi Mitko (d. 1890), the author of collections of Albanian folksongs, folk-tales and sayings, in his The Albanian Bee (Bleta Shyqpëtare), Spiro Dinë (d. 1922) in his Waves of the Sea (Valët e detit) and Andon Zako Çajupi (1866-1930) in his Baba Tomorri (Cairo, 1902) and his Skanderbeg drama — although they lived in Egypt for much of their lives, were essentially nationalists and not much influenced by

14. On Bosnians in the region of Nubia see Burkhardt‘s Travels in Nubia, London, 1819, pp. 134-5 (1822 edn, p. 31), on Ibrim, and within a wider context, V.L. Ménage, ‘The Ottomans and Nubia in the Sixteenth Century’, Annales Islamologiques, vol. XXIV, 1988, Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 1988, pp. 137-53.

![]()

210

the Islamic way of life that they saw around them. If anything, the rural and peasant life in Egypt acted as a spur to their absorption in popular traditions which, in their view, enshrined the soul of their people. The Albanians in Egypt were, without a doubt, influenced by the Egyptian theatre — but specificially by those elements not overtly infused with Islamic sentiments. Later writers became prominent figures among the Albanian community in Cairo. Milo Duçi (Duqi) (d. 1933) did so because of his office as president of the national ‘Brethren’ league (Villazëria/Ikhwa), and by his Albanian newspapers (al-‘Ahd, 1900, known in Egypt as al-Aḥādīth, 1925). He also wrote plays, especially ‘The Saying’ (E Thëna, 1922) and ‘The Bey’s Son’ (1923), and a novel Midis dy grash (Between two women, 1923). More recently still, it has been secular and Arab nationalist causes such as Palestine and Algeria that have inspired Albanian Egyptian writers.

Nonetheless, Çajupi’s poetic works (Vepra, Prishtinë, 1970) are more revealing about his religious beliefs than one might expect. In Baba-Tomorri (Cairo, 1902) he epouses, as was to be expected, his strongly nationalist sentiments. Equally apparent are his notions of religious tolerance. These show, on the other hand, the influence of the national poet Naim Frashëri. But Çajupi’s verses exude the same respect for other religions as his great predecessor, though, in his case, from an orthodox position within Islam. He deplores the fate of the Albanians, torn between Greek and Turk (each of a differing faith); nor does he conceal his strong dislike of the deceit that was so apparent in both church and mosque. On the other hand, both Muslims and Christians share a belief in One Lord (Te krishtër’e myslimanë gjithë një Perëndi kanë), and both are brothers to one another (jemi vëllëzër të tërë). Furthermore, albeit Sunnī, his reference to the single face of man, be he a Muslim or a Christian, as being the creation of a single shared God, reveals the inherited symbolism and poetic vocabulary which the Baktāshīs derived from the Ḥurūfiyya and from the all-pervading influence of the poetry of Nasīmī (Zoti kur bëri insanë, me një fytyre të naltë të krishtër’ e myslimanë i gatoi nga një baltë. Zoti me të math të vetë është një dhe i vërtetë si këtu si këtu dhe n’atë jetë. Si Ungjilli dhe Kurani, mos e ndajni Perëndinë). Born of the dust of the earth, descended from Ādam, as both Gospel and Qur’ān alleged, so the one shared God had only to will His human creation into existence (fa-innamā yaqūlu lahu kun fa-yakūnu).

However, the influence of al-Azhar on shaping the works of exiled Balkan writers cannot be denied. It was not confined to Balkan Muslims in Egypt who were Albanian. Bosnians were more directly inspired to devote their energies to matters that were markedly Islamic.

![]()

211

One relatively recent figure who resided for a long time in al-Azhar was Mehmed Handžić (Muḥammad b. Muḥammad Ṣālih al-Khānjī al-Busnawī, to give him his Arabic name), who was born in Sarajevo and died in Bosnia in 1945 — one in a long line of scholarly Bosnians who had thus sojourned in Cairo. His biographical dictionary on the scholars and poets of Bosnia (al-Jawhar al-asnā fī tarājim ‘ulamā’ wa-shu‘ arā’ Būsna) is highly regarded in Egypt (published as it was in Cairo, in Arabic, in 1349/1933). To this may be added his gloss and commentary on the Rislālat ḥayāt al-anbiyā’ by al-Bayhaqī, and on al-Kalim al-Ṭayyib by Ibn Taymiyya. These are characteristic of the solid traditional scholarship of Bosnia, which has included a remarkable variety of other literary activity.

Of the works of leading Albanian writers at this time, it would seem that those of Muhamet Kyçyku (Çami) (1784-1844) represent the influence of al-Azhar in its clearest form. He had come to al-Azhar from Konispol specifically for a religious education, and continued as a religious teacher from the time of his return home till his death. His study of both Arabic language and literature was to have a profound influence on his choice of poetic subject, first in a direct translation of the ‘Mantle Ode’ (al-Burda) of al-Būṣīrī (d. circa 1296), a panegyric of the Prophet with a message appealing in a popular manner to the believer in his miracles, and also in his other odes, especially the Qur’ānic-based Yūsuf and Zulaykhā’ (2,430 verses) and Arwā (856 verses), based on the Nights (although finding no place in the Mahdi edition), known under its Albanian title of Erveheja, [15] composed about 1820. It has been transformed into a play by the writer Ahmed Tchirizi from Kosovo, that evoked a number of kindred Albanian tales and romances about a faithful wife separated from her spouse, who maintained her loyalty against the unjust and the self-seeking conduct of others towards her.

3. Albanians and the Cairene Baktāshī tekkes

Both the Baktāshī tekkes were once significant landmarks in Cairo, and historically the most important centres of this specific Ṣūfī order in the Arab world. They were also centres for cultured individuals including noteworthy poets. They filled a role, though on a more substantial scale, of elite artistic circles that had once met and rectified poetic compositions within the pilgrim hostel tekkes of Baghdād and Karbalā.

15. See Chapter 2, notes 82-84.

![]()

212

Unlike the latter, the tekkes at Qaṣr al-‘Aynī and of Kajgusez Abdullah Megavriu [16] in Cairo were focuses of local life in a number of respects. Shaykh ‘Abdullāh al-Maghāwirī was a major interdenominational saintly figure of the Mamlūk age, adored by the pious in Egypt who had no religious reasons for seeking formal affiliation to the Baktāshiyya. Furthermore, the area adjacent to the tekke of Qaṣr al-‘Aynī was an administrative district, fortified in Mamlūk times, that was especially prominent during the lifetime of Muḥammad ‘Alī and his immediate successors. There is no conclusive evidence in support of his personal initiation into this particular order, although it has been claimed and may indeed be a fact. What is clear is that for a time the area surrounding the Qaṣr al-‘Aynī tekke was to be the haunt of Albanian, Turks and Persians in the Egyptian capital, and that some among them could be described as ‘Shī‘ītes’. The word almost certainly alludes to Baktāshī beliefs or sympathies, or else to the allegiance which some of them owed to the saintly memory of Ḥajjī Baktāsh Walī, particularly members of the Janissary corps.

During the rule of Muḥammad ‘Alī, the Albanians — typically — formed a distinct body within his army. Albanians had been mercenaries since at least the second half of the seventeenth century and on occasions had balanced or stiffened the unreliable Janissaries (of whom they had likewise formed an element). They were tribally mixed, yet each one was devoted and loyal to the tribe from which he originated. None displayed any special religious ardour, though whether the fact that they did not fast during Ramadan (as reported by Jabartī) was due to indifference or the allegiance of some, at least, to the practices of the Baktāshiyya, which ignored this obligation, is not clear. Muḥammad ‘Alī decided to select Qaṣr al-‘Aynī as the most suitable site for his distinguished ‘college’. James Augustus St John wrote in 1834 that it was built ‘on the right bank of the canal of Rhoda’ and ‘forms the most prominent feature of the scenery of the metropolis. To the right of the edifice is the establishment belonging to the sect of the Shiahs (probably the Baktāshiyya) formerly the palace of Mourad Bey, surrounded by a grove of enormous sycamores.’ [17]

16. On Kaygusuz Abdāl (Kajgusez Abdullah Megavriu), see in particular Dr Riza Nur (Nour), ‘Kaüghousouz abdal (Ghaïbi bey)’, Revue de Turcologie, vol. II, no. 5, Feb. 1935, pp. 77-98, and Baba Rexhebi, Misticizma Islame dhe Bektashizma, New York, 1970, pp. 183-98. For a description of the establishments see F. W. Hasluck, Christianity and Islam under the Sultans, vol. II, pp. 514-16.

17. James Augustine St John, Egypt and Mohammed Ali, or Travels in the Valley of the Nile, London, 1834, vol. II, p. 395, and Gaston Wiet, Journal d’un Bourgeois du Caire. Chronique d’Ibn Iyas, vol. II, Paris: SEVPEN, 1960, pp. 84-5.

![]()

213

Far earlier, in the later medieval period, the city had been noted for its Ṣūfī establishments, some of them ‘convents’. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa described them in the course of his Riḥla as separately managed by the various dervish orders, ‘mostly Persians, who are men of education and adepts in the mystical doctrines’. [18] After describing their social life and eating habits, he adds, ‘These men are celibate; the married men have separate convents.’

It was during this same period that other locations in and around Cairo were favoured as haunts for meditation and the siting of Ṣūfī establishments, including the burial-places of the saintly dead.

According to Dr Tawfīq al-Ṭawīl (al-Taṣawwuf fī Miṣr ibbāna ’l-‘aṣr al-‘Ūthmānī (pp. 67-78):

Perhaps the spread of the convents [zāwiyas/zawāyā] on Egyptian soil will help [us] to picture the plethora of the retreats with which the Ṣūfīs were acquainted in Ottoman days. But the zaiviyas were not the sole places where fixed retreats took place. Among the Ṣūfīs there were those who, in their sincerity and their devotion to God and His adoration and for the benefit of the soul, dispensed with a specific zawiya in which to dwell together with novices. Men such as these lived in caves, where they held their retreat and adored God and held their dhikr. Such caves were spacious and visibly kept in good order. The cave of the Sharīf Abu ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī was hewn into the mountain, levelled with symmetry. Other retreats were held in private dwellings.

The alleged retreat of Abu ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī was destined to become one of the most famous of all, a focal point, next to the Muḥammad ‘Alī mosque and the Citadel, for the Albanian and Turkish Baktāshīs of Egypt, and a city landmark. However, the occupant of the tomb in the cave was held in awe long before the Albanian community — deriving some advantages from the family traditions of Muḥammad ‘Alī and his descendants — became the ultimate trustees of its sanctity, sadly only to lose it forever with the demise of the Egyptian monarchy.

According to Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, who devotes a chapter to the history of Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī in his al-Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya:

The Baktāshī ‘Alīd ṭarīqa was unknown in Egypt until the visit of the perfect saint, the ascetic bestower of favour, Kajgusez Abdāl Sulṭān (Qayghusāz) renowned as our lord and master ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī, in the year 751/1388, in the age of the [Baḥrī Mamlūk] king al-Ḥājjī Ṣāliḥ [b. Sha‘bān, 1381-90].

18. For a general account in Arabic of Ṣūfīsm in Egypt at this period see Tawfīq al-Ṭawī1, al-Ṭaṣawwuf fī Miṣr, ibbāna ’l-‘aṣr al-‘Uthmānī, Cairo (n.d.), pp. 52-69.

![]()

214

Our Lord, referred to above, God bestow upon us benefits through his blessings and grace [barakāt], was the son of the prince of the town of ‘Alā’iyya [sir] (Adaliya). His original name was Ghaybī. When he was a youth around eighteen years old, he was very strong, with sinewy arms and was famous among his people and kindred for his knightly horsemanship and manly courage. He shot arrows with skill and smote with the sword. His intelligence was recalled on every tongue. He delved far and deep into the sciences, both exoteric and esoteric. In sum, he was a man of acute percipience, scholarly and distinguished, a man of mighty destiny and importance.

When he came to Egypt in that year, the common populace were aware of his status. Novices flocked to him and associated lovers of the Ṣūfī path [muḥibbūn] and the mass of human kind assembled with him in order to kiss his blessed hand and seek his grace and spiritual power and blessing through his prayer that was habitually answered. After he had resided in Cairo for some five years he journeyed to the Ḥijāz in 796/1393/4. He visited Medina the illuminated, noble al-Najaf and Karbalā. Then he returned to Egypt in 799/1396/7. In 806/1403/4, a special locality was erected for him and a tekke built for him, Qaṣr al-‘Aynī, which, still today, continues to be in the well-known locality adjacent to the hospital, on the southern side. He dwelt there. He acquired great renown and his brilliant miracles were manifested. Many people took a covenant from him. He died in 818/1444 and was buried, according to his injunction, in the existing cave which, at that time was a tekke of the Jalāliyyīn. The shaykhs who followed after him adopted this usage sanctioned by tradition. All of them were entered in the same cave, following the example of their mighty Shaykh. [19]

During this earliest phase of the Baktāshī presence in Egypt (certainly before the Ottoman conquest) it can be observed that a founder-figure already existed, that the order had a tekke in Cairo city and that it shared in the cave-cult of Egyptian Ṣūfīsm at that time. At a popular level its local founder was already entering the folklore, imagery and hagiographical repertoire of the story-teller, and nowhere more obviously than in the Mamlūk folk-epic known as Sīrat al-Ẓāhir Baybars. [20]

The presence of Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī in varied passages in the text of this work, as we now have it, together with his, admittedly secondary, background role among the personalities in it, at least established that the text was written no earlier than 1388, and probably much later. Futhermore, there are minor references to Ismā‘īlīs, to warrior ‘brethren’ armed with magical wooden swords, in the manner of Sari Saltik

19. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, al-Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, op. cit., p. 25.

20. Sīrat al-Ẓāhir Baybars, (al-Maktaba al-Mu‘allimiyya al-Kutubiyya, near to al-Azhar and Sayyidnā al-Ḥusayn), 1st printing 1326/1908, part 12, pp. 45-6. ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī appears at various points of the narrative in the Sīra.

![]()

215

(see p. 157) and to a King Ṣāliḥ, whose name recalls the ruler of Egypt, al-Ḥājj Ṣāliḥ. The latter was reigning when Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī arrived in Egypt. Alternatively, the name may refer to the Ayyūbid Sulṭān, al-Ṣāliḥ Ayyūb (d. 1249). King Salih has a companion named ‘Uthmān. These details suggest some Ottoman, or Baktāshī allusions; one can hardly call them influences. A far closer study might show deeper Qalandarī and Baktāshī influences at work. The following passage, for example, indicates how popular piety combined with Ṣūfīsm had given the saint a high place in popular esteem, despite the competition faced from other major saints:

Whereupon, King Ṣāliḥ (‘the pious king’) arose. He took ‘Uthmān by the hand and proceeded with him until he was nigh ‘the sea’. He pointed to it with his hand, then descended and stepped into it, ‘Uthmān being with him, up to their ankles in depth and they continued thus until they had passed over to the other side.

Whereupon, King Ṣāliḥ said to him ‘Close your eyes, O my brother ‘Uthmān.’ The latter closed his eyes and had counted seven steps when, behold, he found himself in a country known only to God. King Ṣāliḥ said, ‘Save me, O Overseer from among the mystic order of Watchmen’. Then, lo, a person drew nigh unto them, saluted them and pointed to ‘Uthmān, who fell to the ground in a swoon [of ecstasy] as though he had been slain. This was Sīdī ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī. He had observed ‘Uthmān, bestowing upon him an awesome glance. He said to King Ṣāliḥ, ‘Journey from here to the island of the [Ṣūfī] spiritual leader of the Invocation of the Age, and respond obediently to what he commands you to do.’ The King said, ‘To hear is to obey.’ Al-Maghāwirī said, ‘Journey forth with the Almighty’s blessing.’ He pointed to ‘Uthmān, who awoke from his swoon. King Ṣāliḥ said, ‘Let me have your hand so that we may pass over to the further shore.’ ‘Uthmān said, ‘Let me tarry longer than you. You cross over on your own, then I shall act likewise.’ The two of them waded out until they reached the given “island” about which they had been informed by Sidī ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī. They met the Pole of the saints who was there. He glanced at ‘Uthmān in a manner that was complete, a perfect gaze. Then he said to King Ṣāliḥ: ‘Know that Baybars is in Genoa. You must give him succour.’

From the existing accounts and descriptions from travellers — such as those by Evliya Çelebi (1671), in the Khiṭaṭ Tawfiqiyya by ‘Alī Mubārak, or by Carston Niebuhr and others [21] — it would seem that

21. See the description en passant of Qaṣr al-‘Aynī introduced in a discussion of Baghdād tekkes in Carsten Niebuhr’s, Voyage en Arabie et en d’autre pays circonvoisins, vol. II, Amsterdam, 1780, pp. 243-4.

![]()

216

in its heyday Rawḍa Qaṣr al-‘Aynī tekke, was an impressive complex of up to two domed structures with decorated marble facings and amply furnished with refectory and other facilities, and a fountain bearing an inscription dated the 15th Ramadan 1197/1782/3. Apart from this tekke, Baktāshī pilgrims, including Albanians, were also frequenting the higher Muqaṭṭam district, traditional site of the cave of Sīdī Abu ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī. They may have done this from as early as the sixteenth century.

Probably the most comprehensive description of the vicissitudes of the Qaṣr al-‘Aynī tekke is furnished by the Egyptian historian al-Jabartī, in Part 4 of his ‘Ajā’ib al-Āthār fi’l-Tarājim wa’l-Akhbār: [22]

In the middle of the months of Shawwāl 1201/1783/4, the construction of the tekke adjacent to Qaṣr al-‘Aynī, known as the Baktāshī tekke, was completed. Its story is that it was given as an endowment to a group of non-Arabs [a’āijim, Turks, Persians?], known as the Baktāshīyya. Circumstances had brought it close to ruin, and it had become extremely filthy. Its shaykh died and there was a dispute over who should merit the title of shaykh between a man who had originally been one of the private soldiers of Murād Bey, and a young man who claimed to be one of the offspring of the former shaykh who lay buried within the tekke. That [former] man got the better of the youth because of his relationship with the Amīrs. He travelled to Alexandria and, as his visit coincided by chance with the arrival there of Ḥasan Pasha, he had a meeting with him. He was clad in dervish attire. They have a liking for that mode and he became one of his intimate friends. This was on account of his being one of the people who adhered to [Ḥasan Pasha’s] belief. He accompanied him to Cairo and acquired both reputation and notoriety. He was called dervish Ṣāliḥ and began to construct the aforementioned tekke out of bribes received from the customs tax — he acted as a go-between for those who handled [the customs receipts] and Ḥasan Pasha. Thus with the endowment he built its fabric and its walls, and the garden walls encompassing it on all sides, and he raised a water tank in the entrance to the dome-shaped edifice. He prepared the arrangements for the tekke, the facilities and a kitchen and, on the outside, he built an oratory with the name of Ḥasan Pasha. When that was completed, he made a feast in celebration and invited all the Amirs. But rumours of intrigue and misgivings spread among them. They equipped themselves and after the ‘aṣr prayer rode with all their Mamlūks and their followers, armed and at the ready. He laid out a meal for them and they sat down to eat.

22. ‘Abd al-Raḥmān b. Ḥasan al-Jabartī, ‘Ajā’ib al-Āthār fī’l-tarājim wal-akhbār, edited by Ḥasan Muḥammad Jawhar, ‘Abd al-Fattāḥ al-Saranjāwī and al-Sayyid Ibrāhīm Sālim, Cairo text, Lajnat al-Bayān al-‘Arabī, part 4 (1958-66), pp. 41-2.

![]()

217

They were suspicious of the food, believing it to be poisoned. They arose and dispersed outside the Qaṣr and the moored boats. He made a warlike display (?) with a naphtha conflagration of touchwood and from gunpowder. They were suspicious of his eccentricity. They then rode during part of the night and went to their homes.

However one views the authenticity of this somewhat unsavoury and bizarre anecdote, it indicates the varied vicissitudes that befell the Qaṣr al-‘Aynī tekke. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā takes up the story a little later:

The situation continued thus until the time of Shaykh Ismā’īl Bābā (1239/1823) who was a contemporary of the governor, ‘Abbās Pasha I. (d. 1298/1881), when an order (1242/1826) was issued from the governor to evict the dervishes from Qaṣr al-Aynī, which was to be set apart for the Qādiriyya order. Shaykh Ismā’īl took his dervishes, who numbered twenty-six, and settled in Qaṣr Ismā’īl Pasha Sirrī al-Manāstirlī (Bitolj?). He stayed there for nine months. After this they changed from their dervish attire and adopted lay clothes. They left Egypt and travelled to Medina. The only one of them left in Egypt was Shaykh Ismā’īl Bābā together with a dervish called Ṣādiq. After a short time, the shaykh in question died. The tekke library remained in the Qaṣr of the said Ismā’īl Pasha, and eventually dervish Ṣādiq emigrated to Anatolia where he visited the tomb of our lord and master, the mightiest Quṭb, founder of our ‘Alīd order.

After dervish Ṣādiq had been favoured to pay this visit in this noble manner, he was appointed shaykh of the tekke in 1268/1851, having obtained a license (ijāza) from Shaykh ‘Alī Dede al-Sā’ātī. He came to Egypt, and bought a dwelling in Bāb al-Lūq quarter, adopting it as his residence and as a house of worship and for the assembling of the brethren. He resided there till 1282/1865, when Shaykh Ṣādiq Bābā was translated into close proximity to his Lord’s mercy. ‘Alī Bābā (1285/1868/9) succeeded him. He moved from that place to the existing tekke [located in a cave] of Sulṭān ‘Abdallāh al- Maghawirī by reason of the noble and gracious command issued by the ‘father of favours’, the dweller in the bowers, the Khedive most noble and proven, Ismā’īl Pasha, may God cause him to dwell within the expanse of His garden of Paradise and clothe him with happiness. The insignia of our ‘Alīd order have continued to remain in the tekke referred to up till the present time. [23]

It is now a closed tekke (vacated in 1957), once one of Cairo’s supreme beauty-spots, that was to become a show piece of the last three shaykhs of the order in Egypt, all of them Albanians. The first, Ḥaydar Mehmed Baba, born in Leskovicu, was de facto shaykh from 1303/1885

23. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, op. cit., p. 26.

![]()

218

although only officially confirmed as such by the Dede Baba in Hacibektaș in 1305/1903. It was his successor Mehmed (Muḥammad) Luṭfī Bābā (1265-1360/1849-1941) and Sirrī Bābā, who succeeded him in 1354/1935/6, who made the Muqaṭṭam tekke one of the most important Baktāshī tekkes in the world, visited by famous personalities and acting as a focus for Albanian cultural and political interests in the entire Middle East. [24]

However, the two short biographies found in the Risāla by Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā have a special interest in themselves, since they shed light on the circumstances of the order in the Balkans at that time and indicate motives why Egypt, in particular, became a magnet drawing men of religion to Cairo from that part of Europe.

4. The history of Shaykh Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā and Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā

Master of virtue and of guidance, Shaykh and Ḥājj Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā, was born in Gyrokastër, pertaining to the realm of Albania, in the proximity of Dūnāvāt (Denavet) in his father’s house in the morning of the second day of Ramaḍān, the honoured, in 1265/1849. His father named him ‘Islām’, and generally gave him this name until he was affiliated to the ‘Alīd Baktāshī order, whereupon he was named Muḥammad Luṭfī, as will subsequently appear. He grew up in this town in the personal care of his father, Yaḥyā Lāmaqū Efendi, who was a focus of attention among his people on account of the intensity of his piety, his abstemiousness and his God-fearing life. As he grew to manhood he read the Qur’ān in its schools, and the principles of the Islamic sciences. Thus he continued until the signs of intelligence appeared upon him and his father perceived an aptitude for using his initiative. So he gave him a love for trade and he became an associate in it. What marked his character was trust and self-restraint, fair dealing and upright conduct. His good conduct permeated him wholly.

When he was twenty-seven years old (1292/1874/5), he had become skilled in commerce and had grasped its principles. He sought his father’s permission to travel abroad. Together with his brethren in Gyrokastër, his birthplace, he rose and took up residence in the city of Shkodër, and engaged in commerce there. As he had a strong bias towards Ṣūfīsm and asceticism, he prepared to devote himself and his life to austerity, to piety and to worship. He found what he missed and what he sought for in Shkodër. In the year 1296/1878/9, early in his thirty-first year, he became an affiliate to the master of virtue,

24. Baba Rexhebi, Misticizma Islame dhe Bektashizma, New York: Walden Press, 1970, pp. 183-98.

![]()

219

Shaykh Ḥasīb Bābā, shaykh of the tekke of the Baktāshī hierarchy in Shkodër, when this tekke was a house for the teaching of true virtue, good manners and literature, just as it was a place where those of ascetic tastes assembled. From that time forward he was given the name of Muḥammad Luṭtfī and his guide was Ibrāhīm Bābā. Following his affiliation, he wound up his commercial activities and left his fortune there to his brethren.

In the year 1300/1882/3, when aged thirty-five years, he left Shkodër for the seat of the Sublime Caliph and sojourned in the tekke of Shāqūlī Sulṭān (the warrior) in the suburb of Mardyūn Kōy (Merdiven Keui) on the Asiatic side of the Bosphorus. He was admitted to membership of the circle of the perfect guide and active scholar, Ḥājj Muḥammad Dede Bābā, the shaykh of the said tekke; there he correctly engaged in obtaining his exalted pleasure and was guided by his sublime guidance. His esteem grew among his brethren and he stood out from them for his lofty qualities and praiseworthy features and his compliance in acting obediently so that our lord the Shaykh clothed him in honour, cared for him and clad him by his noble hand with the livery (khirqa) of nobility and the sublime crown [of the Baktāshiyya] which he placed on his head.

When he was forty-one years old (1309/1891/1), he began a life of travel for the faith and visited the holy places. He left Istanbul and he arrived in Karbalā and had the honour of paying a visit to the tomb of our lord and master, ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, the lion of God [in al-Najaf], may God ennoble his countenance. From thence he returned to Anatolia in 1310/1892/3 and stayed in the tekke of our lord, the Sulṭān of the gnostics, the proof of those who attain the Truth of Divinity (ḥaqīqa), the mightiest saint, and most generous succour, our Lord, Ḥājjī Baktāsh Walī, may his secret that is manifested be sanctified. He stayed there for three years and experienced outpourings of the spirit in the counsels of Ḥājjī Muḥammad Dede al-Malātiyyawī (from Malatya) and he attained the degree of tajarrud — unhampered single-minded devotion — due to the zeal of his guide, Ḥājj Fayḍallāh, through being stripped from all links that joined him to this world. After he had obtained this exalted rank he devoted himself solely to obedience and to continued reading and study and to worship and devotion. He was distinguished among his brethren due to his loftiness. He pursued the true path of sincerity and loyalty. He followed the Sharī’a and the Sunna of the Prophet — the blessing and peace of God be upon him — and he eschewed heresies and he opposed misleading beliefs and fancies until he became the light of the garden of the Truth and the light of the pupil of the eye of this Ṣūfī order. He loved the mendicant novices. He prepared food for them with his blessed hand and he personally served them at their table. In 1313/1895/6, when he was forty-five years old, he returned to ‘the house of happiness’ [in Istanbul] and stayed there a year. Then he journeyed to Rumelia to visit the noble tekkes there. He returned to Istanbul a second time.

When he was fifty, he put his trust in God and began to equip himself to

![]()

220

fulfil the duty of the Meccan pilgrimage. So he travelled to the Holy Land and attained his objective. He antimonied his eyes with the soil of the Ka‘ba, and performed the stages, circumambulated, and made the pilgrimage outside the annual season (‘umra). He then returned to Istanbul and spent two years there. In 1319/1901/2 he obtained the noble authority to teach (ijāza). His labours, which were to make him famous, took place in the (Istanbul) tekke. He clung stubbornly to fulfilling the principles of the order and its rules to perfection. His piety and asceticism were [with these above] responsible for his being appointed director of the office of shaykh of the ‘spiritual carpet’ (shaykh al-sajjāda) of the Baktāshī tekke in Egypt. In 1319/1901/2 he left Istanbul and arrived in Egypt. He was received with worthy hospitality because his lofty renown had preceded his arrival. The brethren and novices gathered around him and to this day he has continued to preach sermons and offer guidance — may God prolong his lifespan and bless us by his life among us.

Since he assumed the affairs of the tekke he has constantly striven to exalt its status, repair its monuments and conserve all his zeal and physical and spiritual energy to augment its splendour and beauty, and facilitate and embellish the path for the brethren — those who are affiliated and those who are associated as spiritual members (muḥibbūn).

A year following his attainment of the Shaykhdom, in Egypt, 1320/1902/3, a fearful explosion occurred in the powder magazine (al-jabkhāna) and in the ammunition that was stored adjacent to the tekke which caused the ruin of the tekke buildings and the total spoiling of its distinguishing features. Seeing the beautiful character that distinguishes our lord the Shaykh and the loftiness of his zealous endeavour, he was viewed with consideration by princes and ministers and leading men of state. He therefore submitted his case to the men of government and God blessed his charitable effort. What he sought, without trouble, was facilitated by God — that is the rebuilding of this tekke in which we take pride in being associates, for we have grown up within the perimeters of its flowing waters and spiritual blessings. No wonder, therefore, that his happy days were the most flourishing of the ages of this noble tekke, and that by virtue of his mighty endeavours the eternal monuments that we behold in every place, each and all offer the greatest evidence and proof of the same. He is a respected and patient shaykh. He has become famous on account of his moral life and the purity of his moral integrity. He loves welfare and does not spare himself in promoting it. He is mercifully kind and affectionate and he conceals no hatred for anyone. He is jealous and zealous and a fighter which he combines with praiseworthy qualities. In short, he is the bearer of the title of the perfect guide. We beseech God to supply him with favour and success. Owing both to the excess of his attachment to the ‘eye-lashes’ of faith and to his belief in love for the fatherland, he built in his birthplace (Gyrokastër) a large mosque where prayers are said and the Friday sermon is preached and the two great feasts are celebrated. Likewise, his is a deep love for the comfort

![]()

221

of his fellow-countrymen, causing sweet water to flow into the town. He has built a fountain for it. It has lasted to this day and is well known as the ‘fountain of Luṭfī Bābā’. He has been nicknamed ‘the father of the poor’ because of what he has spent at one time or another on the poor of the town in the form of gifts and financial assistance.

Not content with the great efforts that he has made in enhancing the tekke, he has added to them a major matter of pride, namely his grant to every dervish resident within it of 100 Egyptian pounds. He has made them secure from want and need. For our part, we are not capable of paying back to him what is due for his mighty services, or to recount his virtues and his mighty deeds of supreme worth. All that we have mentioned is but a drop from the sea of his goodly favour and his generosity. On the feeble author he bestowed the noble ijāza at the beginning of Rajab, in the year 1342/1923/4, and took him as his deputy and heir. He appointed him to be his successor as shaykh of the tekke. He [the author] asks the Almighty to keep him in perfect health and give us a blessing during his rich and fruitful life, so that his novices will not be denied the breath of inspiration from his holiness and his sanctity. [25]

Such writing expresses the sentiment of adoration that is so characteristic of the relationship between shaykh and novice. This is to be found among Balkan Ṣūfīs, as elsewhere in Islamic communities with a well-established tradition of lodges and of supportive communities.

Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā also devotes several pages in his work to his own autobiography, explaining how he came to join the tekke of Kajgusez Sulṭān, built around the cave-tomb of Abū ‘Abdallāh al-Maghāwirī. He remarks:

Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā was born in the village of Glina, adjacent to the town of Leskovicu (appertaining to the Albanian government) in the year 1313/1895. His father was the late Shāhīn Efendi, son of Aḥmad Jūjūl Efendi. He grew up in the town and spent his youth imbibing the sciences and sundry knowledge. When he was seventeen, he was initiated into the ‘Alī Baktāshī order, having obtained the pleasure of his father. Then he emigrated in the company of Shaykh Sulaymān Bābā, the shaykh of the Baktāshī tekke in the town of Leskovicu. [26]

He had an inclination for the ascetic life, worship and devotion, and his love for the people of God was a cause of his becoming joined to the Ṣūfī’s when still in the prime of youth, because he who is discerning and bright seeks perfection, while he who is ignorant seeks money. As has been said, ‘The love of the people of God is the key to Paradise.’

25. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, ibid., pp. 30-5.

26. On Leskovicu, see Nathalie Clayer, op. cit., pp. 346-7.

![]()

222

After he had stayed in an aforementioned tekke for one year, war was declared between the Turkish and Greek governments. The Greeks occupied the town of Leskovicu and launched raids on the adjacent towns. Before this disaster, they had impelled Shaykh Sulaymān to leave the town, and he emigrated with his dervishes to the town of Ioannina. After staying there for a short while, the author asked his shaykh’s permission to leave the tekke, and acquired from him a letter of recommendation to Shaykh Sha‘ban Baba, the Shaykh of the tekke in the town of Prishtinë. He travelled there and took the covenant from [the latter] in 1332/1913. The Greeks occupied this town as well, and the author was forced to emigrate yet again. He joined Shaykh Sha‘bān Bābā and travelled with him to Italy. He desired to be at a distance from the war zone. He took up residence in a hotel called Milano in the town of Salsāmājyūrī, [27] and the two of them were there for four months. After this they went forth from it to go to Cairo and stayed in the tekke of our lord Sultan al-Maghāwirī, may God be pleased with him. After a brief sojourn, Sha‘bān Bābā died and was buried in the noble cave [on the Muqaṭṭam] on the sixteenth day of Muḥarram 1333/1914. May God’s mercy for him be ample. When the shaykh of the tekke, through close contact with his novice Aḥmad Sirrī, discovered that he had potential gifts and a propensity to some attainment, he showed him honour. He taught him, and thereby [the author] obtained the divine outpourings of the spirit. Having stayed a little while, he was permitted by his shaykh to undertake a spiritual journey. He began with a visit to the tomb of the lord and supreme Pole, the founder of the order al-Ḥājj Baktāsh Walī, in the land of Anatolia. He remained there two years, during which he was privileged to be able to attend the councils of the chief men of the order. In 1341/1922/3, he decided to leave the town to go to Tarsus. When he arrived there, the shaykh of the tekke Ṣādiq Bābā had died. The brethren and novices were in a consensus over this affair, agreeing to appoint the author to be the shaykh over them. When the author beheld the unanimous opinion of the men of the order, he bowed to their wishes. He obtained a authority license from Shaykh Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā, one of the khalīfas of the order, and the Shaykh al-Sajjāda [28] in Cairo, following the rules of the order and its principles.

At that time the master of virtue and guidance, Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā, had reached old age. He was in pressing need for rest and devotion to worship, so he wrote to his spiritual son, the author, and asked him to come to Cairo to bear with him some of the affairs of the tekke. In view of the wish of the noble shaykh, the author resigned from the shaykhdom and, of preference,

27. The identity of this place is uncertain, although it could be Salsomaggiore, west of Parma (44.48 N-9.59 E).

28. Together with the term Ṣāhib al-Sajjāda, this title is defined by Hans Wehr, in a Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic as ‘title of the leaders of certain dervish orders in their capacity of inheritors of the founder’s prayer rug’.

![]()

223

chose to be a dervish. His love of being in charge did not dissuade him from immediately responding to the command of his master and guide. At once he set out from Tarsus, accompanied by the dervish called Muḥarram. He came to Cairo and was honoured to kiss the hands of his superior guide. On that occasion, the shaykh and Ḥājj Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā assembled the dervishes, the brethren and associates (muḥibbūn), and convened a council of high dignity. At the gathering he announced that he had adopted Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā as his general deputy while he lived, and appointed him to be the shaykh over the tekke after his death. The men of the order were confronted by this appointment, which had unexpectedly caused his people perfect joy and acceptance, and they warmly approved of it.

The shaykh, having obtained this acceptance from the dervishes and others, wrote down the noble licence and gave it to the author. That was at the beginning of Rajab 1342/1924. The following year, the author was struck by a malady which compelled him to stay in bed. The doctors advised him to go abroad for a change of air to improve and recover his health. So he travelled to Albania and stayed there for six months. Then he returned. After some time he went once more on his travels to visit Baghdād. Karbalā and al-Najaf before returning to Egypt. The fatigue of travelling had affected his health, the illness returned once more, and he was compelled to travel afresh in order to be cured. He left Cairo exhausted and arrived in Salonica. Near this city is the town of Katerini (Qatrīna) and by chance its shaykh, Ja‘far Bābā had died, and his place remained vacant. When the men of the order affiliated to this tekke knew of the author’s arrival in Salonica, they invited him to be the shaykh over them. He accepted and fulfilled their hopes. He obtained a licence from one of the khalīfas, who resided in Albania, and he was appointed shaykh. He stayed two years in the town until his disease abated and he regained his health. At that time he offered the affair [for decision] to his shaykh, Luṭfī Bābā, who issued his noble command that he should return. The command, having reached him, he forsook the shaikhly office and hastened back to Cairo. [29]

During the period in office of the last three shaykhs of the tekke, all Albanian, the buildings were transformed into a tranquil retreat that would attract artists, poets and writers, some Egyptian, others associated with the Baktāshiyya, which at that stage had become concentrated particularly in the Albanian countries. This atmosphere of the tekke under Ḥaydar Meḥmed Bābā at the beginning of the century was conveyed in the writings of travellers. Gaston Migeon, in his Le Caire, le Nile et Memphis (Paris, 1906, p. 83), wrote:

But today the monks [sic] are really of their epoch. They are no longer solitary, they receive visitors, and their order of its own accord seeks for contributions.

29. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, ibid., pp. 53-6.

![]()

224

A stone stairway leads up from the foot of the mountain to the gate of the convent. In a small court, which is cooled by a fountain, a monk welcomes you. He is clad in baggy trousers and a grey tunic, his head covered with a high hat of white cloth. His beard grows to a great length. A tame gazelle, gracious and lively, wanders in the courtyard with uneasy movements as if alarmed. A deep corridor is hollowed into the side of the mountain, where Baktāsh [sic] rests within a small sanctuary lit by several candles. The soil of this cave, dug into the hard sand, is covered with mats and carpets. On the wall are hung trophies — spears and axes, and ridiculous pictures.

One returns gladly to the few square metres from which these men have been able to make such a verdant corner within this arid solitude. In small gardens they have planted vegetables and flowers, in the shade of orange trees and cassias. And from there the view is so beautiful that the eye is not sated by the contemplation of it all.

Under both Muḥammad Luṭfī Bābā and Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, the Muqaṭṭam complex was to be graced with extra rooms, catering facilities, drinking fountains and basins of water, bearing inscriptions and dedications in Arabic and Albanian. Endowments grew and both the royal house of Muḥammad ‘Alī (the courtly circles surrounding King Fārūq) and the exiled King Zog I were to sustain the fabric and enjoy its tranquillity. The remains of the Albanian princess Rūḥiyya Zogu were transferred on 28 February 1950 from the crypt of Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, having been interred there on 28 February 1948, to a shrine close by which had been erected for her. [30]

However, one of the personal friendships that knit the life of the tekke to that of Egyptian littérateurs was that between Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā and the Egyptian poet Aḥmad Rāmī. [31] The two men shared a taste for

30. F. de Jong, ‘The Takīya of ‘Abdallāh al Maghāwirī (Qayghusuz Sulṭān) in Cairo: A historical sketch and a description of Arabic and Ottoman Turkish materials relative to the History of the Bektashi Takīya and Order preserved at Leiden University Library’, Turcica, XIII (1981), pp. 242-60.

31. The early life of Aḥmad Rāmī in Thasos is outlined in the study by Dr Ni‘mat Aḥmad Fu’ād, Qiṣṣat shā‘ir wa-ughniya in the series, Iqra’ (no. 368), Cairo: Dār al- Ma‘ārif, pp. 6-7. Aḥmad Rāmī made a noted translation of the Rubā’iyyāt by ‘Umar al-Khayyām. On the whole it received a welcome from his literary contemporaries in Egypt, among them S. Spiro Bey (himself an Albanian) who at the time was head of the literature department of the Egyptian Gazette. It can hardly be doubted that this masterpiece was one of the poetic interests shared by Aḥmad Rāmī and Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā in his Cairene tekke.

The Rubā‘iyyāt inspired other Albanians, and not only Muslims. Bishop Fan Noli, who had lived in Egypt and knew Arabic, Persian and Turkish, translated it under the pen-name of Rushit Bilbil Gramshi. Noli had a deep appreciation of, and sympathy with, medieval Persian thought, including philosophy and mysticism. For further details see Arshi Pipa, ‘Fan Noli as a National and International Albanian Figure’, Südost Forschungen, vol. 43, 1984, pp. 252-3 and passim; likewise ‘Il pensiero religioso nel paese di Skanderberg’, Il Pensiero Missionario, vol. V, 1933, pp. 299-301, footnote 9, from the introduction to his translation, Brussels, 1927.

A few further points might be made here. The Very Rev. Arthur E. Liolin, with whom I have corresponded on the circumstances that led to the adoption of the nom de plume of Rushit Bilbil Gramshi, has pointed out that the Vienna edition of Noli’s translation, was published in the very year 1926, when he was overthrown by Aḥmad Zogu. While in Germany, Noli concealed his identity.

The introduction (Hyrje) to the 1926 Vienna edition of Rubajatet e Omar Khajamit (i shqiperoj), pp. 5-21, discloses the varied reasons, all of them personal, why Noli undertook the Albanian translation, which has been called ‘the finest, with the possible exception of Fitzgerald’s’. The efflorescence of Persian culture (multi-variant and suffering the burden of hybrid creeds and influences) under the impact of Islam between the ninth and the fourteenth centuries stirred him, as it had stirred other Albanians (including Naim) before him. The appeal of Iran was always present among them and Noli dedicates his translation to Niẓāmī and Ḥāfiẓ. For Noli the language of ‘Umar (d. 1123) was of a unique beauty, and furthermore the composition had been distorted, misrepresented and sometimes mistranslated, its purity sullied by dross that was alien to the original. Noli viewed the Persian intellectual response to this Islamic impact that homed on Baghdād, as being first the emergence of a conforming and reconciling group of dogmatists and literalists; secondly, a school of neo-Platonic Ṣūfīs; and lastly a daring, indeed heroic company of rationalists and questioning men who wedded science (Noli praises ‘Umar’s scientific contribution) and philosophy. These latter — ‘Umar among them — had qualities that matched his own thoughts and sentiments, and for that matter those of other Albanians of the Rilindja.

![]()

225

poetry and the tekke furnished a milieu where congenial company could be enjoyed, accompanied by recitation of verse and meditation. Aḥmad Rāmī was also drawn to Persian as a language and made his own translation into Arabic of the Rubā’iyyāt by ‘Umar Khayyam. His version has been highly praised in some quarters. [32] Thus Professor C. Huart, in Paris, praised its closeness to the original. Professor ‘Abd al-Qadir al- Mazinī found the translation close, though weak in its poetic spirit. However, S. Spiro Bey, head of the literary section of the Egyptian Gazette and himself an Albanian, was struck by the simplicity of Aḥmad Rāmīs language: ‘He uses an easy simple language as adopted by Omar, so that the reader finds no difficulty in following the sense the Persian poet desired to convey.’

There were, however, other reasons that brought the two men together. The grandfather of Aḥmad Rāmī, Ḥasan ‘Uthmān,

32. Muḥammad Mūfākū, ‘Hal kāna Rāmī ḥaqqan min Shuyūkh al-Ṭarīqa al- Baktāshiyya’ in al-‘Arabī (Kuwayt), no. 260, 1980, pp. 40-2.

![]()

226

was an Albanian who had settled in Crete. He came to Egypt, rose to officer rank, and was killed in action in the Sūdān in 1885. Muḥammad Rāmī, the poet’s father, also joined the Egyptian army as a doctor, but died at the age of forty-seven. Aḥmad Rāmī spent part of his happiest earlier years on the island of Thasos near Kavalla. All these family circumstances meant that he shared common memories with Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā. Their literary tasks coincided, although whether Aḥmad Rāmī, as a poet himself, became anything more than an associate of the tekke is unproven, even though there is a suggestion that he was finally invited to join the Baktāshiyya.