3. ṢŪFĪ MOVEMENTS AND ORDERS IN THE BALKANS AND THEIR HISTORICAL LINKS WITH THE ṢŪFĪSM OF CENTRAL ASIA

‘It would be mistaken to think that in the hands of the theologians Islam has remained a closed book. Ever more closed to science and open to mysticism, theology has permitted many irrational — and to Islamic teaching — completely alien elements and even blatant superstitions, to be added to it. It will be clear to anybody who is acquainted with the nature of theology why it found itself unable to resist the temptation of mythology and why it even saw in this a certain enrichment of religious thought. The monotheism of the Koran, the purest and most perfect in the history of religious teaching, was gradually compromised and a repulsive commercialism appeared in its practice.’ (Alija Izetbegović, The Islamic Declaration)

2. Non-Shī‘īte Ṣūfī orders in the Balkans 100

3. The Qādiriyya 105

7. The Malāmiyya 115

8. Shaykh al-Ṭā’ifa al-Bayrāmiyya 118

9. The origins of the Baktāshīyya in Albania 123

10. When were the first tekkes built in the heart of Albania? 126

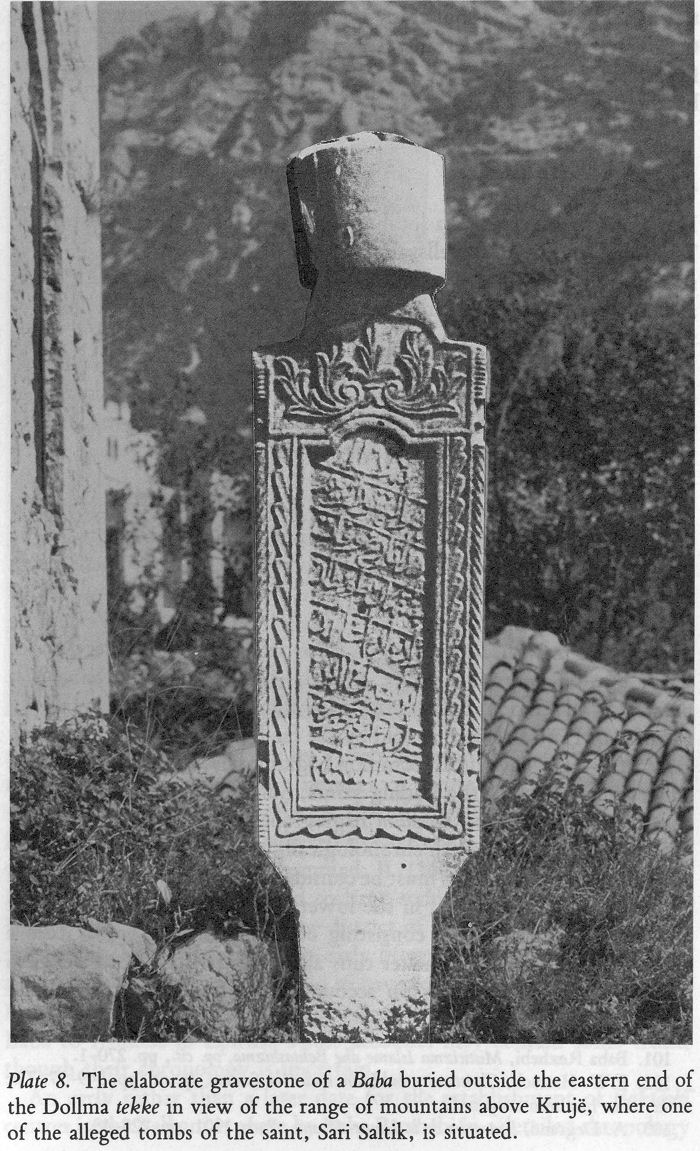

11. Krujë 129

To consider the impact and the influence of Ṣūfīsm and the Ṣūfī orders on the Balkan countries, some attention has to be directed, by way of introduction, to the Ṣūfīsm of Central Asia. Ultimately it is from that region, via Turkey and the Caucasus, that many of the ideas, practices and beliefs of Balkan Ṣūfīsm originally evolved under the impact of Iranian ideas. Central Asia occupies a prominent place in Islamic history and especially in the evolution of Ṣūfīsm. Particularly important are Khurāsān and Transoxania. [1] It was in this latter region of Central Asia that the study of Prophetic ḥadīth achieved its peak, and it was there that the most important early collections of ḥadīth were compiled. [2] Central Asia was also a major centre for the study of the Qur’ān and Islamic theology.

Ṣūfīsm, Islamic mysticism (taṣawwuf), owes a number of its most important concepts to pious men and thinkers in Khurāsān and Transoxania. To some it was indebted in matters of doctrine, to others in

1. On the religious beliefs peculiar to Central Asia, and more especially those factors that influenced the evolution of Ṣūfīsm (especially heterodoxy) see Emel Esin, ‘Eren’. Les Dervīš héterodoxe Tures d’Asie Centrale et la peinture surnommee “Siyāh- Ḳalam” ’, Turcica, vol. XVII, 1985, pp. 7-42.

2. As is confirmed by such names as Muḥammad b. Ismā‘īl al-Bukhārī, born in Bukhara in 194/810; Muḥammad b. ‘Īsā al-Tirmidhī, who died near Balkh in 279/892-3; and later Maḥmūd b. ‘Umar al-Zamakhsharī, born in Khwārizm in 467/1075.

82

![]()

![]()

83

those matters that related to the rules of practice (ādāb) in the dervish orders and the habit of the retreat (khalwa). [3] Crucial too were those matters of organisation and discipline within the brotherhoods (ṭuruq) as they subsequently evolved.

From Central Asia and later, likewise, from the Caucasus these innovations were adopted elsewhere. Great scholars such as al-Kalabādhī [4], al-Qushayrī [5] and al-Hujwīrī [6] were to record a transformation of Ṣūfī ideas, beginning with the simple monotheism and early asceticism of such men as Uways al-Qaranī and al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrī, [7] through the emotional and personal mysticism of love (maḥabba), in the verses of Rābi‘a al-‘Adawiyya, [8] to the gnosticism of al-Junayd and al-Ḥallāj, [9] and ultimately to that of the Spanish-Arab, Ibn al-‘Arabī, and Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, [10] especially the doctrine of the extinction of self within the divine essence (fanā’) and existential monism waḥdat al-wujūd — these latter earned for Ṣūfīsm the charge from the orthodox of exchanging monotheism for pantheism. To cite the respected Albanian Baktāshī shaikh, Baba Rexhebi,

Neither man nor any other creation can exist independent from God. All are simply mirrors which reflect their master, the creator, without whom they could not have existed. Neither man nor any other creation can exist independent from God. All are simply mirrors which reflect their master, the true God. Wahdat Wujud sees only one essence existing in the world, any other essence representing its creator:

The pantheistic [sic] notion of Al Arabi is clearly expressed in this excerpt:

You alone hold in yourself each and all creations.

3. A khalwa is a cell for private meditation and retreat among the Ṣūfīs. This is a central feature of the Khalwatiyya ṭarīqa (see article in the Encyclopedia of Islam) but it is important in other orders, such as the Kubrāwiyya ṭarīqa.

4. Muḥammad b. Isḥāq al-Kalabādhī (d. 996), an important Ṣūfī from Bukhara who was the author of Kitab al-Ta‘arruf li-madhhab ahl al-taṣawwuf.

5. Abū l-Qāsim al-Qushayrī of Naysābūr (d. 1074), the author of al-Risāla al-Qushayriyya.

6. al-Ḥujwīrī (d. 1071), the author of Kashf al-Maḥjūb.

7. al-Ḥasan of Baṣra (d. 728), one of the most noted of the earliest Ṣūfīs.

8. Rābi‘a al-‘Adawiyya (d. 801), famous woman mystic.

9. al-Junayd (d. 909-10) and al-Ḥallāj (martyred 922), whose life has been exhaustively studied by L. Massignon in his The Passion of al-Hallaj. See also Chapter 6 below, note 4.

10. Ibn ‘Arabī (Ibn al-‘Arabī) of Murcia (1165-1240) and Jalāl al-Din al-Rūmī (1207-73) are the most influential of the later Ṣūfī, especially in the Persian and Turkish Ṣūfī-influenced countries.

![]()

84

![]()

85

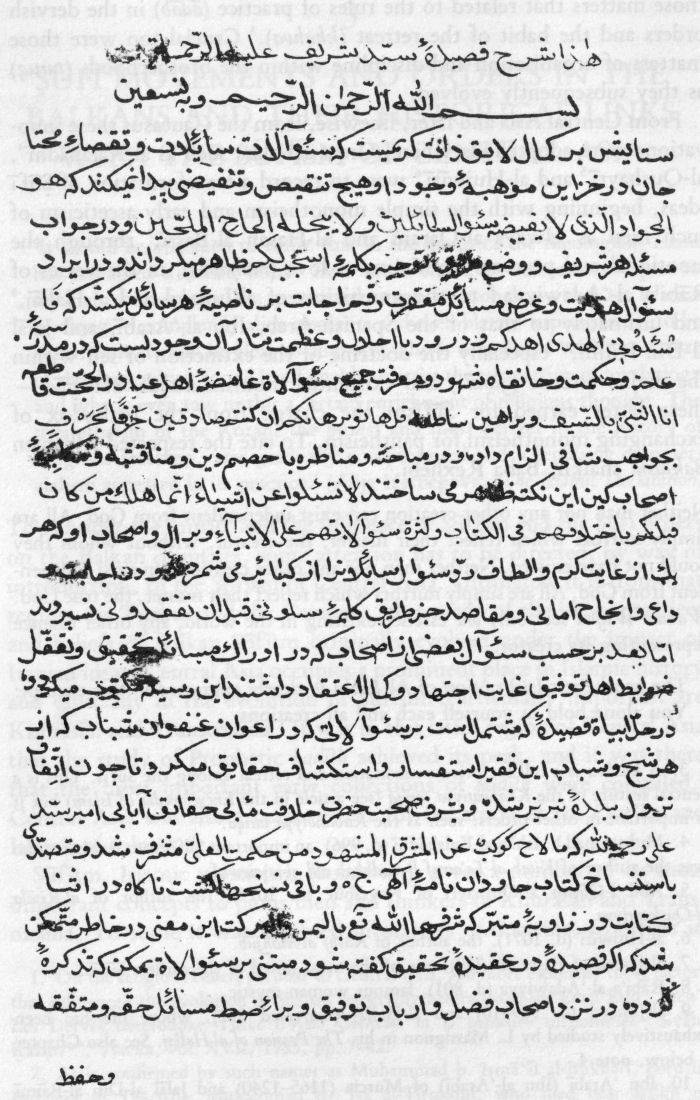

Plate 5. The opening and final folios, with colophon, of a commentary on Ḥurūfi verses of Sayyid Shārif by the Albanian Baktāshī dervish, Yūsuf b. Ḥaydar, possibly of Krujë. The ms. is dated 1240 AH/1824AD and is listed by E. G. Browne as OR, 26(9), in his catalogue of Oriental manuscripts in Cambridge University Library. The verses are part of a q̇aṣīda, or ode, entitled Jāwidān-nāma. There is no clear indication of where the copy was made. ‘Ārnā’ūdī is an unusual spelling of Arnā’ūṭī. Āq Ḥiṣār is an Ottoman name for Krujë. Photograph published by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

![]()

86

You alone inside yourself created all that exists today.

You are the greatest essence.

The essence of God is the essence of all creations and there is no other essence. [11]

This vision manifests a clear terminal line of development within Ṣūfī thought, though it would be wrong to maintain that one stage merely absorbed or displaced another. Ṣūfīsm can be described as containing within itself a variety of subtly differentiated and sometimes incompatible conceptions of man in relation to divinity. Resulting maladjustments were always potentially there.

A semi-constant tension that may subsist between an orthodoxy and mystical movements is not exclusive to Islam, although in certain dervish orders the cult of ‘Alī, the son-in-law of the Prophet, carried to an extreme, was one such major cause of friction. There were, however, other and deeper reasons. These have been defined sharply by Hans-Joachim Kissling in his article ‘The Sociological and Educational Role of the Dervish Orders in the Ottoman Empire’. [12]

From the viewpoint of religious sociology, there are irreconcilable differences which cannot be changed by the fact that occasionally all-embracing pantheism may be colored by a theism instilled from childhood or that it may use theistic terminology, since the pantheistic experience cannot be described otherwise. Permit me to give one example. A mystic entranced by the sight of the stars is no claim that a loving Father must dwell above. Or on our topic: the Islamic dervish does not mind merging the pantheistic all-god term haqq with the orthodox term Allāh, while the strictly orthodox Moslem will carefully distinguish between them. In monotheism the idea of a unio mystica is unheard of, for the monotheistic God is outside his creation, that is, in opposition to it. A union, however, is possible only between essentially equal, not between different, things. Even the attempt of Ghazzali or Qushairi to make mysticism palatable for orthodoxy by declaring it to be originally monotheistic cannot invalidate our statement. The unconscious obscuring of pantheistic sentiment by a monotheistic predisposition can be observed in any form of mysticism.

In the ninth century the Oguz Turks began to embrace Islam. However, it was the counsels of their poet-priest-magician ‘Qam-Ozam’

11. Baba Rexhebi, The mysticism of Islam and Bektashism, vol. 1, Naples, 1984, pp. 75 and 76, under ‘Pantheism: Wahdat-i Wujud’.

12. Published in Studies in Islamic Cultural History (a special issue of The American Anthropologist), ed. G.E. von Grunebaum, 56, no. 2, part 2 (April 1954), memoir no. 76, pp. 23-35.

![]()

87

that appealed to them more than the teachings of the Muslim faqīhs. The Old Turkoman religious traditions lasted long in their memory, subconsciously or consciously influencing the later Ṣūfīsm of the Yasaviyya, the first Ṣūfī order to be fully ‘acclimatised’ among the Turks.

Here the ceremonial dhikr and the samā‘ were adjusted to the ecstatic dances of the Shamanistic Turks. As the Turks moved westward into the Islamic heartlands between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, so these ideas were to be influenced by others which were preached by the Carmathian (Qarāmiṭa) Isma‘īlīs, with their division of Islamic religious teachings and beliefs into the esoteric (al-bāṭin) and the exoteric (al-ẓāhir). Sects emerged. Extreme ‘Alīd views among the Boghratch Turks, a long distance from the borders of Khurāsān and Transoxania in the eleventh century, allotted to ‘Alī the role of the Turkish Sun God, Göle Tengri. [13] Once Ṣūfīsm was institutionally realised within sundry orders (ṭuruq), so these esoteric beliefs aided in the formation and promotion of mendicant and dervish orders, such as the Qalandariyya and the Haydariyya.

Here [writes Fuad Köprülü] the role of the Turks is too important to be neglected. There was a [Ṣūfī] order which, deriving its origin from the Malāmatiyya [14] of Khurāsān (as represented by such great Ṣūfīs as Abū Sa‘īd Abū’l-Khayr and Ḥamdūn-i-Qaṣṣār) after Shaykh Jamāl al-Dīn- Savī (in the years 382-463/992-1070), and under the influence of diverse factors and in different Turco-Muslim regions, had developed, and took a more definite form under the names of ‘Abdālān’ [15] or Javāliqa’ (those clothed in flock or hair). Excommunicated by the orthodox theologians and even by certain mystics because of the scandalous customs of its adherents and because of their indifference towards dogma and religious duties, this order, which was very widespread in the Muslim world, from the sixth to the thirteenth century, gave birth to a series of secondary branches among which the ‘Ḥaydariyya’ order was especially worthy of attention. [16] Shaykh Quṭb al-Dīn Ḥaydar, a disciple of Yasavī,

13. This and other kindred topics are discussed extensively in Irène Mélikoff, ‘Recherches sur les composantes du syncrétisme Bektach-Alevi’ in Studia Turculogica memoriae Alexeii Bombaci Dicata, Istituto Universitario Orientale, Seminario di Studi Asiatici, XIX, Naples, 1982.

14. Keuprulu Zadé Mehmed Fuad Bey (see also p. 88 overleaf, note 22), ‘Les Origines du Bektachisme. Essai sur le dévéloppement historique de l’hétérodoxie musulmane en Asie Mineure’, Actes du Congrès International d’histoire des religions, Paris, 1923, vol. 2, 1925, p. 398. See also Claude Cahen, ‘Le probleme du Shi’isme dans l’Asie Mineure turque préottomane’, Le Shi’isme Imamate, Paris, 1870, pp. 115-39.

15. Fuad Bey, ‘Les origines da Bektachisme’, p. 398.

16. ibid., p. 399.

![]()

88

who was born into a princely Turkish family and who died after 618/1221 and was buried at Zāva near Nīshāpūr, had founded a zāwiya, or convent. Its fame was to last for centuries. He surrounded himself with numerous adepts who were recruited among young Turkish men. Between the Qalandariyya and the Ḥaydariyya, orders overtly esoteric (bāṭinī) in their tendencies, and the Baktāshiyya there was so much affinity that we see these terms employed as though synonymous in subsequent centuries. [17]

Later he comments:

The esoteric creed of the great orders and heterodox sects such as the Ḥaydariyya, the Baktāshīyya, the Ḥurūfiyya, the Ni‘mat Allāhis, [18] the Nūrbakhshiyya, [19] the Qyzyl-Bāsh [20] and the ‘Alī-Ilāhis [21] is only, in fact, an eclectic and syncretic system, heterogeneous and sometimes even incoherent, a kind of conglomerate of Muslim esotericism, of indigenous beliefs of Anatolia and Iran, with an infiltration of diverse schismatic forms of Christianity and philosophical and Ṣūfī ideas. Naturally, the character and proportion of these elements differ according to each sect or order, but whatever the result that future studies reveal, one can affirm that from this time onwards, the migration to the west of the Oguz nomads has contributed powerfully to the extension of heterodoxy in the countries of Anatolia and Iran and to the triumph of Shī‘īsm with the Safavids. [22]

Fuad Kopriilu relates the Baktāshīyya to the other heterodox Ṣūfī orders:

Although the Baktāshī brotherhood existed in the fourteenth century, it was not the most important among the analogous heterodox fraternities which were the continuation of Bābāism. It only acquired this importance between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, that is to say after having absorbed the other heterodox groups. The existence in the fourteenth century of the cult of Ḥājjī Baktāsh,

17. ibid., p. 400.

18. On the Ni‘mat Allāhī’s see Farzad Daftary, The Isma‘ilis, their history and doctrines, Cambridge University Press, 1990, pp. 462-7.

19. ibid., pp. 463 and 471.

20. On the Kizil-Bash (Kizilbaș etc.) see the article by R.M. Savory in the Encyclopedia of Islam (new edn), pp. 243-5.

21. There is an extensive literature on the ‘Alī Ilāhīs. See Matti Moosa, Extremist Shī‘ītes: The Ghulat Sects, Syracuse University Press, 1987. In this particular context, the reader is referred to Nikki R. Keddie, ‘The Roots of the Ulama’s Power in Modern Iran’ in Keddie (ed.), Scholars, Saints and Ṣūfīs: Muslim Religious Institutions in the Middle East since 1500, University of California Press, 1972, pp. 217-19.

22. Mehmed Fuad Köprülü, Les origines de I’empire ottoman, Paris, 1935, p. 123.

![]()

89

the successor of Bābā Rasūl Allāh, among the Abdāls and all the other groups stemming from Bābāism has prompted the belief that all the groups were Baktāshīs and has given the Baktāshiyya an exaggerated importance in the foundation of the Ottoman empire. Ḥājjī Baktāsh also had members of his sect in Western Anatolia. Let us add that these groups of wandering dervishes who exercised a major and a crucial influence on the religious life of the sedentary and nomad populations on the frontiers also played the most active role in the conversion of Christian populations. In the Islamisation of the Balkans during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, this decisive role of groups of heterodox dervishes appears very clearly. [23]

To balance this picture, something should certainly be said about the many other important and more orthodox Ṣūfī orders that entered the Balkans after the Ottoman conquest, for example the Naqshabandiyya which, like the Baktāshiyya, shares origins in the popular mysticism of the Turkic-speaking countries, especially in the Yasaviyya Ṣūfī order, though only so at a relatively recent date. [24] However, it is the Baktāshiyya that most obviously represents the surviving heterodoxy of the Central Asian Turkomans, the Iranians of Khurāsān, the Isma‘īlis and Carmathians, and, added to these, many of the customs and the beliefs which were indigenous to the pre-Ottoman Balkan peoples themselves. [25]

1. The Baktāshiyya

The Baktāshiyya, unlike other Ṣūfī orders in the the Balkans, though officially Sunnī, is essentially Shī‘īte. Members of this order believe that their founder, Ḥājjī Baktāsh, was born in Khurāsān in the thirteenth century. He was either taught by, or had a spiritual relationship with, Ahmed Yasavī (Aḥmad al-Yasawī), which took no note of the passage of time.

23. See also Keddie, ‘The Root of the Ulama’s Power . . .’, op. cit., pp. 212 ff.

24. In regard to Bosnia, the Naqsbabandiyya has been admirably covered by Ḥāmid Algar, ‘Some Notes on the Naqshabandī Ṭarīqat in Bosnia’, Die Welt des Islams, vol. XIII, nos 3-4, 1971, pp. 168-203.

25. These matters are extensively discussed in Mehmet Fuad Köprülü, ‘Les Origines de l’Empire Ottoman’, Etudes Orientates, III, Paris, 1935 and in his Les Origines du Bektachisme, Essai sur le dëveloppement historique de 1’heterodoxie musulmane en Asie Mineure’, op. cit.

![]()

90

All paths in Turkish Ṣūfīsm, it is said, lead back to Ahmed Yasavī, or Ata Yesevi, who is also called Pir-i-Turkistan. In the twelfth century Ahmed Yasavī created a genre of popular poetry the purpose of which was to convert the Turkic nomads to Islam. This kind of poetry was to be developed in most Turkic-speaking countries and reached its highest point in the verses of the thirteenth-century Anatolian poet Yunus Emre. Ahmed Yasavī founded the first Turkish ṭarīqa, the Yasawiyya, which spread in Turkish-speaking areas.

Features of the legends that surround the life of Ahmed Yasavī, and the feats he allegedly performed, have been influenced by the divine powers that mark out two legendary characters in very ancient Arabic literature. They are central to the seventh- and eighth-century Yemenite tales of ‘Ubayd b. Sharya al-Jurhumī, and Wahb b. Munabbih’s Kitāb al-Tījān (where references to contacts between the Arabs and the Central Asians may be found in sundry passages). The power of flight is associated with the pre-Islamic prophetic figure, Luqmān, a Macrobite king. He, however, could not fly himself, but his seven eagles could, at his bidding, and when they lost their power to do so this had some effect on his own physical powers and his life-span. One eagle died, only to be reincarnated in its successor. Also, in these works, kingship is favoured with an insight into the mysteries of the ‘fount of life’ (‘ayn al-ḥayāh, beloved by mystics) and into the paradoxes and seeming injustices of the world that are hidden from human knowledge. Guidance for the superman was to be found in the prized companionship of al-Khiḍr, ‘the green man’, the spiritual companion of the ‘two-horned’ king. [26]

Irène Mélikoff has shown that both Baktāshīs and Yasavīs shared a number of common practices. They used, or use, Turkish during their ceremonies instead of Arabic or Persian. Hymns are sung, and women participate in the ceremonies. Both orders share a belief in bird metamorphosis, a dove for Ḥajjī Baktāsh, a crane (turna) for Ahmed Yasavī. The Baktāshiyya was to compound its heterodoxy later, after the sixteenth century, with the addition of the Ḥurūfī doctrines propounded by Faḍlallāh al-Ḥurūfī (executed 796/1394) and with the adoption of the belief in the divinity of ‘Alī that characterised the Kizilbaș. Other beliefs such as reincarnation and sometimes metempsychosis may well have been a legacy from the pre-Islamic Turks, although they also figure

26. Such is the role of al-Khidr in the early age. On his Ṣūfī role see the article by A.J. Wensinck, al-Khaḍir in the Shorter Encyclopedia of Islam, Leiden, 1953, pp. 232-5.

![]()

91

prominently in the beliefs of the heterodox Druze and the ‘Alawites of Syria. [27] Ḥajjī Baktāsh came to Anatolia. His headquarters were established in that spot which bears his name today, Hacibektaș, between Kirșehir and Nevșehir (Suluğa Qara Ojük). [28]

The Albanian Shaykh, Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā in the following passage from his Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, describes the arrival and the settlement of Ḥajjī Baktāsh:

This situation lasted for the lengthy period in which he trod the ‘way’ until he arrived at Ṣūlīja Qarah Ūyūk (Suluğa Qara Ojük) which subsequently became famous by being called ‘the district of al-Ḥajj Baktāsh’ a locality named after his noble name. It belonged to the city of Qīr Shahr (Kerșehir) being a six hour’s travelling distance from it. He stopped there and he adopted it as his place of residence. He began to preach sermons of warning and to offer counsel. He disseminated religious knowledge, whether it be learning in the religious sciences or in spiritual gnosis. Students gathered about him for divine guidance in order to know of the essential reality of the divinity. The people thronged to that district to be blessed by him. So the sublime Baktāshiyya order was spread abroad in the entire land of the al-Rum. The number of those who were affiliated to it increased dramatically until the reputation of our lord reached the ears of Sulṭān Ūrkhān, the second Ottoman Sulṭān. He saw that he would be successful and would benefit through the prayer of the venerable Shaykh, so he left his throne and he journeyed in person to meet our lord and master. He enjoyed the privilege of kissing his blessed hand and he obtained his charitable supplications, and the divine blessing (baraka) came upon him. [29]

Well into the twentieth century, Hacibektaș retained its status as the great place of pilgrimage for Albanian and other non-Turkish Baktāshīs. G.E. White in an article ‘The Alevi Turks of Asia Minor’ in the Contemporary Review (Nov. 1913, pp. 690-8) remarks, after his visit to the tomb and shrine of the founder: ‘The purpose of the Dervish life is the rest, peace, satisfaction, that come on taking the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and withdrawing from the world. It was a surprise to find that out of about four-score dervishes resident at the tekke, nearly all are Albanians.

27. The principal studies of the Druze religion attach importance to this belief among them. A recent study by Nejla M. Abu-Izzeddin, The Druzes: New study of their history, faith and society, Leiden, 1984 (Chapter 13 on al-Amīr al-Sayyid Jamāl-Dīn, ‘Abdallāh al-Tanūkhī), reveals his Ṣūfī commitment. There was clear compatibility in both belief systems.

28. A comprehensive description of the tekke of Haci Bektaș is provided by Suraiya Faroqhi, ‘The Tekke of Haci Bektaș, Social position and economic activities’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, 7 (1976), pp. 183-205.

29. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, al-Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, ibid., pp. 6-7.

![]()

92

What are these Albanians doing, away over in Central Asia Minor? Yet, here they are, with others of Turkish or other nationality [p. 694].

According to the Vilâyet Nâme Manâḳib Hünker Hajji Bektaș-i-Veli, Ahmed Yasavī gave Ḥajjī Baktāsh a number of sacred tokens. These were a head-covering, tadj (Ar. tāj, ‘crown’), a Ṣūfī robe, hirka (Ar. khirqa, Ṣūfī mantle), a table or table-rug, sofra (Ar. sufra, table), a prayer-rug, sedjdjade (Ar. sajjāda, prayer-rug), a candle-stick, çerag (Ar. sirāj, lamp) and a banner, ‘alem (Ar. ‘alam. landmark, banner or flag). All these had been given to the Prophet by God, then to the Twelve Imāms, Ahmed Yasavī and finally Ḥajjī Baktāsh himself. [30]

Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā comments on the symbolic significance of this taj, and khirqa, in his Risala al-Aḥmadiyya:

As for the Baktāshī‘crown’ (taj), it denotes a white skullcap of felt [Plate 5]. It has twelve furrows and is called the Husaynī‘crown’. It is conditional on him who wears this noble ‘crown’ that there should be gathered within his person such qualities as to enable him to be fit for the honour of wearing it. These noble qualities are: knowledge, obedience, the asking for forgiveness, the remembrance and recalling of God, contentment, dependence on God, abstinence, piety, humility, generosity, patience and the giving of one’s approval to what is ordained and decreed. In this there is a pleasing reference to the number of the letters in the confession that ‘there is no god but Allah’, namely twelve letters — lā ilāha illā’llāhu. In ‘Muḥammad is God’s Apostle’, ‘Muḥammad Rasūl Allāh’, there are twelve letters also. As for the wearing of the cloak (‘abā) or the mantle (khirqa), it is among the praised traditions that are followed by the godly forebear. The conquering lion of God, our lord, ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, may God honour his countenance, undertook to clothe Ḥasan al-Baṣrī in the mantle or the cloak. [31]

According to Baba Rexhebi [32] Ḥajjī Baktāsh was born in 648/1247/8 at Nīshābur in Khurāsān, a direct descendant of the Prophet’s family. He studied under Loḳmān Perende the khalīfa of Ahmed Yasavī, was inspired by Ahmed Yasavī and went to Anatolia as a missionary, visiting on his way the tomb of ‘Alī at Najaf in Iraq. He prayed at his tomb for forty days and during the month of Dhū’l-Ḥijja he fulfilled the Meccan pilgrimage. Later he visited Palestine, Damascus and other sacred places. In 1281 he arrived at Soluğa Qara Ojük where,

30. ibid., p. 13. 31. ibid., p. 14.

32. Baba Rexhebi, The mysticism of Islam and Bektashism, vol. 1, op. cit., p. 99-101.

![]()

93

having won the hearts of local Ṣūfī’s, he organised his tekke which was to become the centre for his ṭarīqa. From there missionaries took his message to Arabia, Persia and the Balkans. He wrote two books, Maqālāt-al-Ḥājj Baktāsh and Fawā’id al-fuqarā’. [33] He died either in 738/1338 or in 1341 and was buried in the tekke which he had founded. [34] Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā also says in his Rīsala al-Aḥmadiyya [35] that the word Baktāshiyyah has numerical significance in regard to the decease of the saint. According to the numerical value of the Arabic letters in the Arabic alphabet (al-abjad), the sum total of the letters B-k-t-ā-sh-y-h amounts to 738, this number corresponding to the hijra date of the decease of Ḥājjī Baktāsh (1338). The intimate connection between the Janissaries and the Baktāshīs was to take place years after his death. It was this connection that vitally contributed to the spread of the order in the Ottoman empire. [36]

In the early sixteenth century, the second major Pīr (shaykh) in the history of the order made determined efforts to reform its organisation and the practice of its members, both of which had succumbed to unorthodox practices and rituals. This was Bālim Sulṭān who, to cite Ziya Shaqir in his Baktāshi lyrics (Bektași Nefesleri), was born at Ker in Anatolia in 1472, although other historians say he was born in Rumelia and give the date as 1452 or even later. He re-established celibacy. Sulṭān Bāyazīd invited him to be his guest in the Topkapi Seray, and during his stay the Sulṭān himself and high officials of the court joined the Baktāshī order.

Four grades of initiation were introduced by him into the ṭarīqa:

(1) Asik (Ar. ‘āshiq, lit. lover) or kalender, one who seeks to be fully admitted to the order and receives instruction before initiation.

(2) Dervish, one who had been admitted into the order.

(3) Baba (Bābā), one who after a period as a Dervish becomes the leader and instructor of groups of Dervishes and Asiks.

(4) the Dedebaba, who is the elected chief Baba and who, up till the abolition of the Ṣūfī ṭuruq in Turkey in 1925, was based at the tekke of Hacibektaș. A halife (Ar. khalīfa, deputy) was at times appointed between the grades of Dedebaba and Baba, having been selected by the former to exercise authority as his delegate.

33. ibid., p. 100, footnote 1. See the article in the Encyclopedia of Islam for further details regarding these works.

34. Baba Rexhebi, ibid.

35. Aḥmad Sirrī Baba, ibid., p. 9.

36. Vincent Monteil, ‘Les janissaires’ in L’Histoire, 8, Paris, Jan. 1929, p. 29.

![]()

94

Those Baktāshis who are ‘Children of the Way’ (Yol Evladi) and who believe that Ḥājjī Baktāsh never married and had no descendants maintain that true membership is gained by initiation at the ceremony of Ayin-i Cem [37] after a period of instruction from a mursit (Ar. murshid, guide). With them the Dedebaba is chosen for his paramount worthiness. On the other hand, the Yol Evladi, who claim descent from Ḥājjī Baktāsh, believing him indeed to have married and had a son, maintain a right to the leadership. Known as Çelebis, they are members from birth, and thus no special initiation ceremony is required.

The formal requirements of Islam, especially the ‘five pillars’ (e.g. five regular daily prayers and pilgrimage to Mecca), were never given emphasis among them. Yet fasting during the first twelve days in Muḥarram is observed, preceded by the three preceding days of Dhū’l-Ḥijja. Almsgiving (zakāh) is extended to the helping of all who are in need. The Baktāshiyya were to conceive of Allāh, Muḥammad and ‘Alī in a triune relationship, the Prophet and son-in-law united together in a unity of personality. Baba Rexhebi, however, makes a clear distinction between them, Muḥammad was the bearer of the Islamic ‘light’ [38] while the Imām ‘Alī was inspired by the Prophet and offered by him the knowledge of this same mystical light. ‘Alī, ‘the king of saints’ (shaykh al-awliyā’), then entrusted the divine light to the Prophet’s children and to the remaining Twelve Imāms, until it reached Pir Hunqar Ḥājjī Baktāsh. Furthermore, Baba Rexhebi maintains that the order respects the rituals of the faith, and that there are two special prayers for the goodwill of the world (evrad, Ar. awrād, litanies), at dawn and dusk, and above all observes mourning (matam) for the martyrdom of Ḥusain, son of ‘Alī, at Karbalā. [39]

Baktāshīs hold their meetings in both home and tekke, with recitation and singing of verses occasionally accompanied by music. The meal held at these gatherings might be a sacrificial sheep, the drink wine or raki

37. On the overall organisation and ritual of the Baktāshiyya, including the Ayin-i-cem, one of the most lucid sources I know, and an excellent introduction for anglophone readers, in particular, is J.D. Norton, ‘Bektashis in Turkey’, in Denis MacEoin and Aḥmad al-Shahi (eds), Islam in the Modern World, London, 1983. Likewise Helmer Ringgren, ‘The Initiation Ceremony of the Bektashis’, in Studies of the History of Religions, X: Initiation, Leiden, 1965, pp. 202-8.

38. Baba Rexhebi, The Mysticism of Islam and Bektashism, op. cit., and L. Massignon, The Passion of al-Hallaj, op. cit., vol. 3, pp. 282-5.

39. Baba Rexhebi, The mysticism of Islam and Bektashism, vol. 1, op. cit., p. 99.

![]()

95

distributed by the saki (Ar. sāqī, wine-bearer). In the conversations that developed, sohbet (Ar. ṣuḥba, companionship), discussions would take place on religious and social matters, and questions would be answered by the Baba. Such teachings were based on the Maqālāt of Ḥājjī Baktāsh and were aimed at leading the follower successfully and progressively through the four gateways, Sheriat (Ar. sharī‘a, the canonic law of Islam), Tarikat (Ar. ṭarīqa, Ṣūfī way), Marifat (Ar. ma‘rifa, gnosis) and Hakikat (Ar. ḥaqīqa, the reality or essence of the Divine) attained by the lover (Ar. muḥibb). Each of these represented the observance of the revealed divine law, the path followed within the order itself, the mystical knowledge of God and finally the soul’s experience and feeling of oneness with the essence of Reality. [40]

An important belief, as in the other Ṣūfī orders, is waḥdat al-wujūd, the Oneness of Being, and the discovery of God’s reality within oneself. All creations are only His manifestations. [41] Baba Rexhebi, in explaining this, cites verses by the Albanian poet Naim Frashëri, of whom more later:

Në det të madh e të gjërë

Çdo valë që të sheh syri,

Esht’ atje deti i tërë,

Po valëtë mirë kqyri.

[In the vast ocean the eye sees in each wave all of the seas. Look then closely at each wave your eye can perceive.]

The Baktāshīs have recognised that women have rights equal to those of men, and their presence in the tekke is accepted as natural and correct. In this respect, as Irène Mélikoff notes, the order is heir to the teachings of the Yasaviyya [42]: ‘An important point in the description of the medjlis of the Yeseviye is that women were admitted to the meetings without wearing a veil and alongside men. This custom also exists among the Baktāshīs.’

The Baktāshiyya offered, and still offers, a doctrine that caters for all intellects and temperaments. As will be seen, it shares with other Ṣūfī orders a similar goal, although the path it discloses may differ and manifest contradictions.

40. This is lucidly explained by J.D. Norton in his article on ‘Bektashis in Turkey’.

41. Baba Rexhebi, citing Naim Frashëri (see Chapter 5, footnote 37), ibid., p. 123.

42. A reality confirmed by all Naim Frashëri’s Baktāshī writings (see Chapter 5).

![]()

96

Unique among these orders, as they reached the Balkan countries with the Ottoman conquest, was Baktāshī Shī‘īsm and the intensity of its devotion to ‘Alī. United as one with the Prophet, it is through him especially that the early Arab martyrs of the Muslim faith have made their mark on much of Albanian Islam. [43] To cite Baba Rexhebi:

Pathfinders discuss the sources of mysticism with believers by emphasizing the Islamic foundation of tassawwuf, the importance of the holy Quran, and the words of the Prophet. Not everyone can understand in depth the philosophy and science of Islam. Only the descendants of the Prophet are able to discern the subtleties of tasawwuf. The prophet Muḥammad has said:

I am the city of knowledge and Ali is its Gate.

To enter the garden of Islamic knowledge one must pass through the gate, the great Ali. Muḥammad has also said: ‘Ali is my hereditary successor.’ These words do not imply material inheritance, but they relate to the knowledge and the deference of the Prophet.

After the death of the Prophet, Ali founded the first religious school, madrassa, in Medina. There he began to teach the philosophy of Islam. After the martyrdom at Karbalā, the school continued to exist. Famous scholars like Imam Zaynel Abadin, Muḥammad Bakir and Imam Jafar Sadik were teachers at the school. Students from all over the Muslim world came to study its Islamic philosophy. Imam Jafar Sadik began the teaching of mysticism, which attracted many students, and it continued for centuries until the time of the Pir, Hajji Bektash Wali.

The believers of Bektashism revere the Prophet, the great Ali, and the Twelve Imāms. They believe that the road of Bektashism is the road of the great Ali.

Many of those features that characterised the Baktāshiyya in Turkey, were once to be found among the Albanians, although, as Margaret Hasluck discovered, [44] the Albanians impressed their own individual national character on the Baktāshiyya. As she explains:

Bektashism is a powerful factor in Albanian history and politics, conciliating the Christians enough to make them forget their age-long antipathy to Islam, yet remaining itself a very living force within that religion. It is by no means uninteresting to seek the explanation of such a paradox. In its organization there is nothing extraordinary. The rank and file are not outwardly distinguishable from other Moslems but recognise each other by a secret sign,

43. Baba Rexhebi, The mysticism of Islam and Bektashism, vol. 1, op. cit., pp. 108-9.

44. Margaret Hasluck, ‘The Non-conformist Moslems of Albania’, The Moslem World, vol. XV, 1925, pp. 392-3.

![]()

97

consisting, it is said, in a certain, apparently casual, touching of the chin. Above them are dervishes, conspicuous by their tall, ridged hats of white felt, and celibate or married according to the branch they choose: a single earring denotes a celibate. As usual with Eastern priestly castes, they are bearded, the Serbs rousing more resentment by shaving the abbot of Martanesh than by burning his tekke. Laymen live at home, but dervishes must reside in a convent (tekke), which the donations of the pious living and the legacies of the dead support; its essential feature is an oratory (ibadet hane) for common worship, and in it dervishes, as they die, are buried; a proper mosque is never attached.

Dervishes are appointed by abbots (Babas), who generally preside each over a tekke, and are themselves, if of the celibate branch, appointed either by the superior abbots called khalifehs, of whom three exist in Albania alone, or by the Akhi Dede, supreme head of the celibates, who lives in the central tekke in Asia Minor.

In Albania and other Balkan regions the Baktāshiyya has shown an eclecticism which perhaps surpassed limits observed elsewhere. Margaret Hasluck summarised its basic beliefs as faith, adoration and reverence centred around God, Muḥammad, Fāṭima, his daughter, ‘Alī her husband, and Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, their offspring. ‘Alī has a peculiarly close relationship with the Prophet; their personalities are fused, a personification of some higher spiritual being. The words of the Prophet are quoted, Anā wa-'Alī min nūr-in wāḥid-in — ‘I and Alī are from one light’, and Aḥmad Rifat’s claim (Mir’āt al-Maqāṣid) that man ra’ānī faqad ra’ā’l-Ḥaqq — ‘whosoever sees me beholds the Truth [God’s essence] and the Reality’, as evidence of some mutual theological analogy between the Baktāshiyya and Christianity. [45] Massignon [46] stresses the numerical and Ḥurūfī influenced character of this association. ‘The divine identity of Muḥammad and ‘Alī is a very old extremist Shī‘ite concept. It forms the basis of the Khaṭṭābiyya initiation (in jafr, the numerical value added together is equal to Rabb (Lord = 202)’. The alleged words of the Prophet are quoted.

The dual person of Muḥammad-‘Alī was believed by the Baktāshī Albanians to be represented on earth by every Baba who is thereby entitled to great veneration. A Baktāshī creed would include the twelve Imāms,

45. Similarities between Christianity and Baktāshīsm have mainly been observed in rituals, hierarchy, celibacy and external forms. Irène Mélikoff, in ‘L’Islam Heterodoxe en Anatolie’, Turcica, vol. XV, 1982, pp. 151-3, discusses the relationship between Jesus, Elias and ‘Alī.

46. The passion of al-Hallaj Mystic and Martyr of Islam, Princeton University Press, 1982, vol. 2, 'The survival of al-Hallaj’, p. 255, footnote 86.

![]()

98

Moses, Mary, Jesus and countless saints. Worship is a secret affair, peculiar to initiates. Public prayers are held in the oratory of the ‘parish’ tekke, at sunrise and at sundown and not at the statutory five times each day. The Baba sits in his special corner, reciting the prayers or portions of the Qur’ān, while the devotees sit in a semi-circle around him and bow their heads to him as ‘Alīs representative. Twelve candles for the twelve Imāms burn on a three-tiered altar. Prayer requires no genuflexions, and attendance at the tekke is only compulsory twice a year. Instead of Ramaḍān, the commemoration of the martyrdom of ‘Alī’s sons Ḥasan and Ḥusayn at Karbalā is observed. Metempsychosis is widely believed and universal love for mankind, male and female, and for one’s homeland has become an all-inclusive ethical ideal. Acceptance of suffering without retribution is advocated; all violence and injustice is to be avoided. Charity and hospitality should be shown to all. For initiation, firm sponsorship and a rigorous enforcement of vow-keeping is demanded and expected. Babas once received a severe training either under superiors at other tekkes or at Hacibektaș itself. The admission of a layman was a veritable rite de passage. Convents of married or unmarried dervishes were once known and were sited away from towns and villages. Pilgrimages to holy places were shared by both Muslims and Christians. They were held throughout the calendar: visits to Sveti Naum near Ohrid, to St Spyridon in Corfu and to St Elias on Mount Tomor, who was identified by Baktāshīs with their saint ‘Abbās ‘Alī. [47]

The eclecticism of the Baktāshiyya has prompted comparison with other extreme Shī‘īte sects (ghulāt) — such as the Nuṣayrīs, in parts of Syria and Asia Minor [48] — that are viewed as being on the very fringe of Islam. It is perhaps the Kizilbaș (Qyzyl-Bāsh) who survive in Bulgaria in Deli Orman, that are most often mentioned. However, the Baktāshiyya has not transgressed the bounds of orthodoxy in the eyes of the Muslim community as a whole. The Kizilbaș conceal their true identity, outwardly professing to be orthodox Sunnis to their Turkish or Bulgarian neighbours, or alternatively claim to be Baktāshīs, depending on who is addressing them. Both Baktāshīs and Kizilbaș venerate ‘Alī, who is inseparable from the Prophet Muḥammad.

47. On legends regarding ‘Abbas ‘Alī, see Nathalie Clayer, L’Albanie pays des derviches, op. cit., pp. 409-11.

48. This eclecticism is of course an outsider’s assessment. To many Baktāshīs their beliefs are seen to be orthodox and even a mirror of a truer Islam than is to be found in many other Muslim communities. On this point see Nathalie Clayer, L’Albanie pays des derviches, op. cit., pp. 77-9.

![]()

99

Both honour Ḥasan and Ḥusayn, for whom they mourn. However, the Baktāshīs recognise Abū Bakr, ‘Umar and ‘Uthmān as legitimate Caliphs. Both sects neglect the five prayers and the fast of Ramaḍān. The Baktāshīs, however, maintain that this is because they give emphasis to sincerity of faith and not to the religion’s outward observances.

The Kizilbaș differ fundamentally in some important respects. ‘Alī is a confessed incarnation of God who has revealed Himself in multiple hypostases. Before ‘Alī, Jesus was the greatest — Son, Word, Saviour and intercessor. God is conceived in three persons, with ‘Alī representing the Father, Jesus representing the Son, and Muḥammad, the Prophet, in the role of the Paraclete. Mary is the Mother of God. Below God are five beings — archangels that correspond to the five aytām of the Syrian Nuṣayrīs. Below these are twelve ministers of God, corresponding as they do with the Apostles and the naqībs of the Nuṣayrīs. Satan is not adored, but he is held to be incarnated. He appeared in the person of Yazīd, the enemy of Alī, and in his offspring. In nightly rituals, prayers are said in honour of ‘Alī, Jesus, Moses and David. Penances are imposed, demanded and acknowledged. Bread and wine are received after being blessed. Sometimes a sheep is slaughtered and its flesh partaken by the gathering. Several Christian festivals are observed, including Easter. Al-Khiḍr is identified with Elias. The highest priest, the Dede, is an intercessor between God and man, while the two highest patriarchs of the Kizilbaș are regarded as ‘Alī’s descendants. Many shrines of other faiths, or sects, are revered, including the tekke of Hacibektaș. Woven into the fabric of popular observance are pagan survivals, sun and moon cults, worship of rivers and streams, and adoration of sacred trees in high places. [49]

Although apparently on a smaller scale than in Bosnia and Kosovo, the activities of Ṣūfī orders were not unknown in Bulgaria in the years between the two World Wars. Tadeusz Kowalski observed:

The religious life of the Bulgar Turks equally offers a great number of curious phenomena which merit considerably more attention from scholars, as analogous phenomena have already all but disappeared completely in Turkey proper as a result of radical recent reforms. In the first place it is the matter of the religious fraternities of a mystical character. It is Hasluck who has first indicated

49. F. de Jong, ‘The iconography of Bektashiism’, Manuscripts of the Middle East, Leiden, 1989, pp. 7, 16 and passim. On the Baktāshī presence in Del Ormani see F. von Babinger. ‘Das Bektashi Kloster Demir-Baba’, Ostasiatische Studien, 1931, pp. 8-93.

![]()

100

the extent of Bektāshī propaganda in Bulgaria in former times. Following the information furnished by this author, there should be no more active Bektashī convents in this country. However, the facts furnished by him on this subject do not seem to be entirely exact and they call for some verification. The Muslims sectarians of Deli Orman, called Aliyans or Kyzylbaš, [50] seem to be in close relations with the Bektāshī movement. In his interesting study on the Bektāshī convent of Demir Baba, Babinger has recently touched upon the question of religious tendencies in this region, and has rightly insisted, as in his other works, on the importance of Shī‘īte propaganda amongst the Balkan Turks. It may be that the ‘athletic traditions’ that are so alive in the Deli Orman region, traditions that manifest themselves through the flights of popular athletes in the fairs and that are accompanied by diverse ritual ceremonies, are related in some way with the cult of Saint Demir Baba, mentioned above. There are beside the Bektāshīs other religious brotherhoods. I have visited myself at Ruscuk a small convent observing the Shādhilī rule. In all the country, one comes across sanctuaries, especially sacred tombs, of a two-way religious identity, tombs that are visited equally by Muslims and Christians.

Amongst the Turkish artisan, in towns such as Ruscuk, Razgrad, Sumen, Eski-Dzumaja, one finds the residue of an ancient organisation of corporations that are closely tied to the religious life. [51]

2. Non-Shī‘īte Ṣūfī orders in the Balkans

Džemal Ćehajić, in his far-reaching studies of the implantation of the Ṣūfī orders within the whole of what was once Yugoslavia, has emphasised the predominantly orthodox character of most of the mystical orders, especially in Bosnia and Hercegovina where the Baktāshiyya which Alexandre Popović regards as having once been the ṭarīqa, or order, ‘qui a été le plus répandu dans l’ensemble des pays du Sud-Est européen’ [52] made its mark early on, although it failed to maintain a dominance in the Balkans as a whole. [53] Islam spread in Bosnia and

50. See the comprehensive study of Krisztina Kehl (Bodrogi, Die Kizilbaș/Aleviten. Untersuchungen uber eine esoterische Glaubensgemeinschaft in Anatolien, Berlin, 1988.

51. Tadeusz Kowalski, ‘Les Tures et la langue turque de la Bulgarie du nord-est’, Polska Kracow: Akademja Umiejtnosci, pp. 9-10.

52. Alexandre Popović, ‘Les ordres mystiques musulmans du Sud-Est européen dans la période post-ottomane’ in A. Popović and G. Veinstein (eds), Les ordres mystiques dans l’Islam, Paris: EHESS, 1986, p. 66.

53. For English readers see the useful resumes by Džemal Ćehajić on ‘Bektashis and Islam in Bosnia and Hercegovina’ in Anali Gazi Husrev-Begov Biblioteke, books V-VI, Sarajevo, 1978, pp. 83-90, 97-8.

![]()

101

Hercegovina immediately after the conquest of these provinces by the Turks (Bosnia in 1463 and Hercegovina in 1464-5). It was vigorously promoted and from the earliest days of Islamisation a powerful orthodox theological school was active. With support from the Ottoman authorities, it fought all kinds of unorthodox practices.

The Ottoman governors and Ottoman feudal society pursued a policy of protection and support for Sunnite Islam. They established tekkes of orthodox dervish orders, especially the Mawlawiyya (which has now all but disappeared); the Khalwatiyya which is still alive in Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia, the Rifā‘iyya; the Naqshabandiyya (with its historical roots in Central Asian Islam like the Baktāshiyya), which is found to this day in Bosnia; [54] the Qādiriyya, and at a later period the Tijāniyya in Albania and other orders.

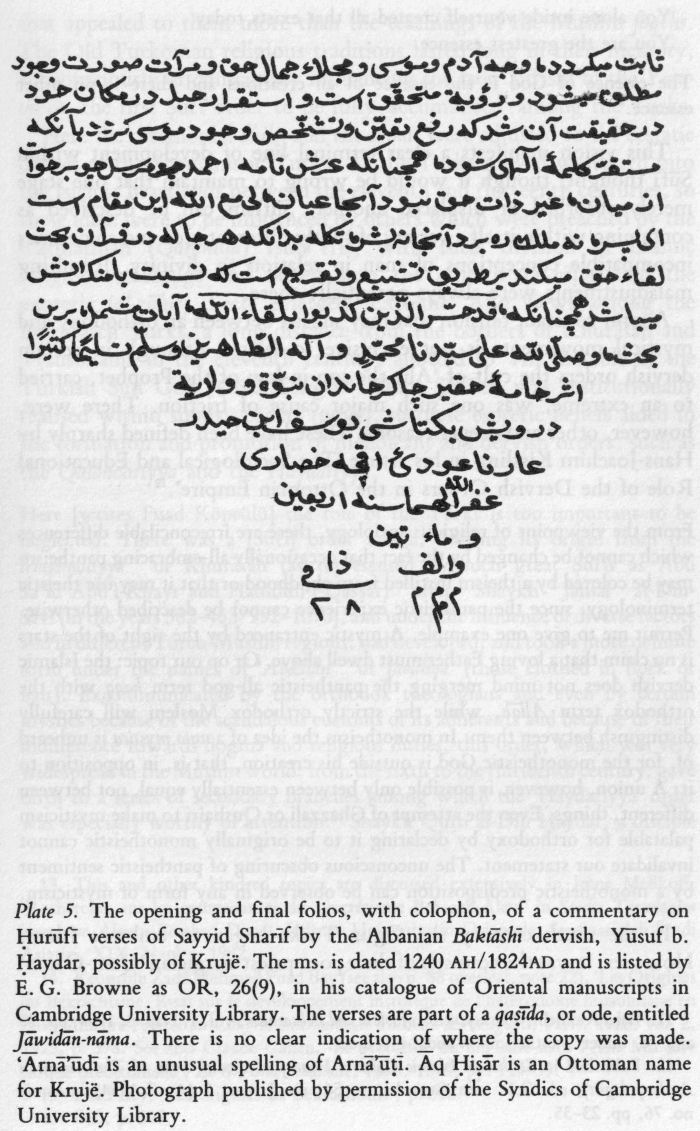

‘Īsā Beg Ishaković, the ‘duke’ of the so-called Western provinces (1440-6), established a Mawlawiyya tekke in Sarajevo in 1462. Skender Pasha, probably during his third governorship in Bosnia (1499-1505), founded a tekke of the Naqshabandiyya, likewise in Sarajevo, about 1500. The famous Bosnian governor (1521-41) and benefactor of Sarajevo, Ghāzī Husrev-Beg, established a Khāniqāh (Hâniqâh) of the Khalwatiyya order of dervishes in Sarajevo before 1531. In the seventeenth century the great tradesman Hadži Sinan-aga founded the Sinan-aga tekke of the Qādiriyya order that was named after him in Sarajevo. These three orders thus played their part not only in the diffusion of Islam and Ṣūfīsm in these regions but also as a defence against the spread of heterodoxy.

The dervishes themselves had a particular role to play in the foundation of these zaviyas (Ar. zawāyā), which over a period became the nucleus for larger settlements. This process began in the fifteenth century in Eastern Rumelia, where there was a settlement of populations in considerable numbers from Anatolia, especially in Thrace, Serres, Thessaly and Macedonia. The dervishes and their elders, the akhis (Ar. Ikhwān), in their numerous zaviyas, fulfilled their duty by offering travellers the services of wayside inns, around which settlements were to develop. To a lesser degree the same pattern of growth may be seen in Bosnia. Among the oldest in that region was the ‘Īsā Beg zaviya, founded in 1462, which according to its endowment (vakifname) was to be an inn and a public kitchen. The zaviya of Ayas Pasha was founded in Visoko in 1477.

54. See the studies by Ḥāmid Algar, Die Welt des Islams, vol. XIII, nos 3-4, 1971, pp. 168-203, and A. Popoviž and G. Veinstein, op. cit.

![]()

102

The dervish Muslihuddin founded a zaviya in Rogatica a little before 1489. About 1519, the Hamzevi zaviya was sited on the Srebrenica-Zvornik road. In Zvornik itself a public kitchen, together with a zaviya, was founded by Bahši-Beg in 1530. In the midsixteenth century a zaviya was founded at Prusac, and in the midseventeenth century the dervishes played a significant role in the Skender Vakif settlement. [55] The close personal connection between the ruler and the dervish goes back to the days of ‘Īsā Beg. According to Vlajko Palavestra, [56]

Isa Beg Ishaković, the second son of Ishak Beg, was governor of the Brankovic lands, and later Sanjak Beg of the Bosnian Sanjak (1464-8). In the spring of 1448 he stormed into Bosnia and, after laying it waste, permanently occupied the Vrhbosna district together with the castle of Hodidjed. In 1463 he played a decisive role in the destruction of the Bosnian kingdom. He laid the foundations of today’s Sarajevo, which took its name from his palace. In the summer of 1464 he was appointed Sanjak Beg of the Bosnian Sanjak for the second time. His name is mentioned for the last time in 1472. The present structure of the Sultan’s Mosque was built only in the 16th century, on the site of an older mosque which must certainly have been built before 1462, and which its founder ‘Īsā Beg later presented to the Sultan Mehmed II, the Conqueror, whence its name.

Ṣūfīsm, however, was not neglected by ‘Īsā Beg. Vlajko Palavestra adds:

In the western part of the old city of Sarajevo there is a mosque which is popularly attributed to a certain sheik of the Magreb. When Isa Beg came to Sarajevo he was accompanied by a dervish sheik from the western lands, from the Magreb who built a mosque on this spot.

Sarajevo became, and remained, a major centre for Ṣūfīsm and its orders. Even today the dhikr (ḥaḍra), the spiritual exercise designed to ensure God’s presence throughout one’s being (J. Spencer Trimingham, The Sufi Orders in Islam, p. 302: the ‘lauding of the Almighty’ or, as Shaykh Baba Rexhebi describes it, ‘a repeating of the names of God, by invocation either silent or vociferous’) is still regularly held in the tekkes of different orders. In the days of Asboth, who wrote in 1890, these services still maintained the ecstatic expression that survives today in Kosovo

55. On Skender Vekif, see Džemal Ćehajić, Derviški Redovi u Jugoslavenskim Zemljama, op. cit., pp. 41-4.

56. Vlajko Palavestra, Legends of Old Sarajevo, op. cit., pp. 39.

![]()

103

but is otherwise more characteristic of the Ṣūfī Orders in India and the Arabic Middle East:

The most frequent meetings of the dervishes also fall during the time of Ramazan: one Friday we witnessed the ceremonies of the Howling dervishes. Towards ten o’clock in the evening we started for Sinan-Thekia, which is situated tolerably high up upon the hillside on the right bank of the Miliaska. This Thekia — Dervish monastery — takes its name from its founder, the celebrated Bosnian Dervish Sheik, who was held in great respect, and was even credited with being a sorcerer. We found a quiet, deserted place, a building in ruins. We were cautioned to mount the wooden stairs with care, and to take our places quietly in the broad wooden gallery; not only because the ceremonies had already commenced, but also that the rotten timbers might not give way. The broad, dome-covered hall was only dismally lighted by a few tapers. Opposite to us there stood, in front of the Kibla (the niche for prayer), which faced towards Mecca, a haggard old man, with a white beard and gloomy visage, in a pale, faded caftan, and the green turban of the sheiks. Before him stood a circle of about twenty men in the dress usually worn by the Mohammedan middle classes in Sarajevo: respectable water-carriers, merchants and artisans. For just as Islam knows no ecclesiastical hierarchy, so the dervishes form no particular order, as our monks do, for example, even though they, like them, rely upon mysticism and asceticism. As a whole the ceremony differs little from what which I have seen in the heart of the Mohemmedan world. But a closing scene followed, which I had nowhere beheld before, and which in its affecting solemnity is unequalled. Whilst one of the dervishes commenced to put out the lights in rotation, the others, one after another, with signs of the deepest reverence, approached the ancient sheik, still standing before the Kibla, and bent low before him; after the salutation each was twice embraced by him, and whilst he who had bidden farewell withdrew in silence, the next advanced to the sheik. The simple naturalness, the deep affection, which was manifested in this silent scene, is quite indescribable. Upon the stage at the close of an act it would make one of the most effective of closing scenes. Yet where would one find so many actors who would, in the constant repetition of the same action, understand how to combine such free, dignified bearing with such reverent awe; the earnest dignity of the sheik with his fatherly affection? One light after the other had been extinguished, one dervish after the other had withdrawn, and ever gloomier did it grow in the dome-covered hall, darker the picture, more vague the dignified form of the sheik, until at last he stood there alone, hardly visible now, by the glimmer of the one remaining taper. My companions had already departed; but I could hardly tear myself away from the scene in which such deep, such true and noble sentiments had been displayed. [57]

57. J. de Asboth, An Official Tour through Bosnia and Herzegovina, London, 1890, pp. 206-9.

![]()

104

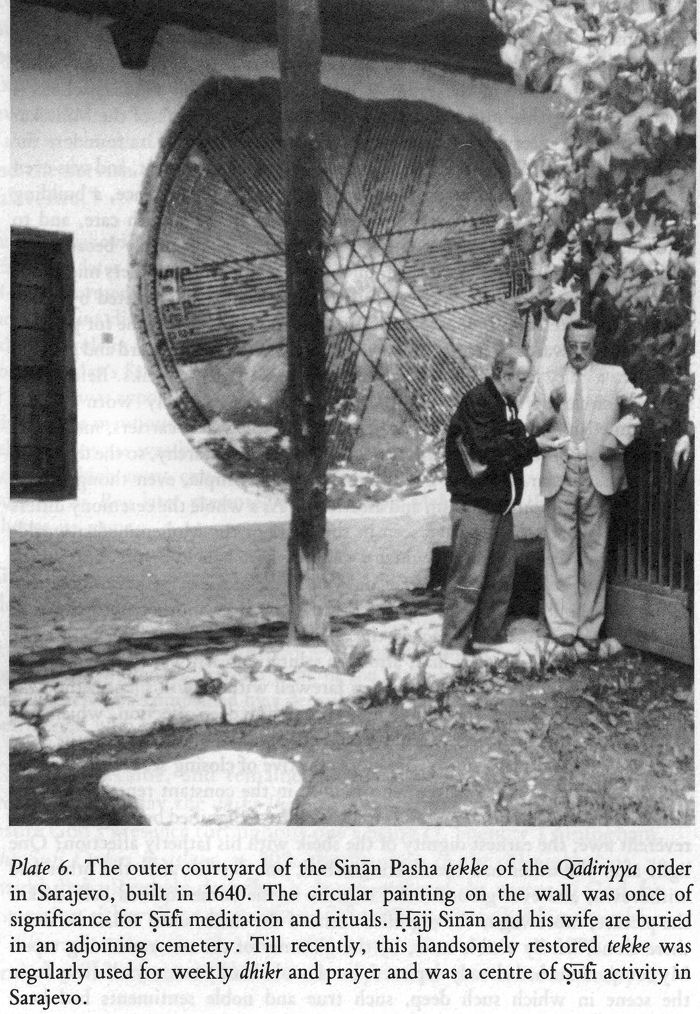

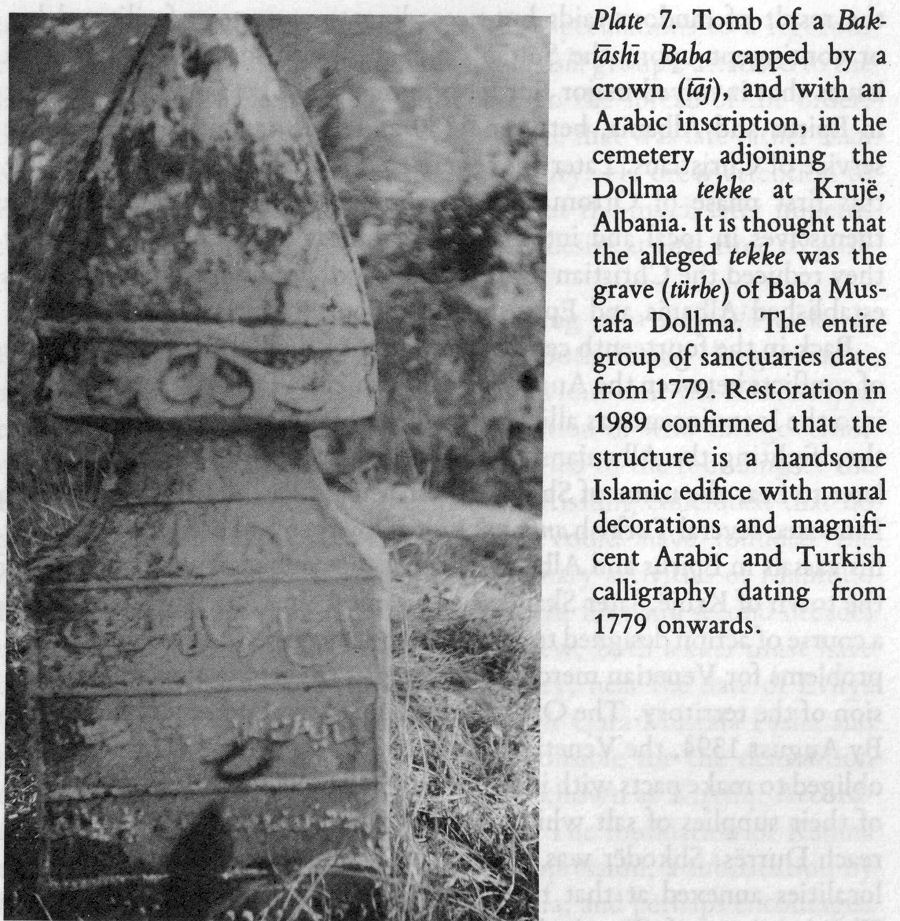

Plate 6. The outer courtyard of the Sinan Pasha tekke of the Qādiriyya order in Sarajevo, built in 1640. The circular painting on the wall was once of significance for Ṣūfī meditation and rituals. Ḥājj Sinān and his wife are buried in an adjoining cemetery. Till recently, this handsomely restored tekke was regularly used for weekly dhikr and prayer and was a centre of Ṣūfī activity in Sarajevo.

![]()

105

The part played by the tekkes (takiyya/takāyā) in spreading Arabic and Islamic learning generally in the region of Belgrade and in northern Serbia is important. Muḥammad Mūfākū, in his Tārīkh Bilghrād, al-Islamiyya remarks:

In addition to their social rôle, the tekkes had their cultural rôle as well. The tekke was a centre for the imparting of culture to those who were part of it and of its following. The dervishes used to hunt for knowledge in the Ṣūfī sources and devoted themselves to writing, especially in verse. Usually in every tekke there was a library which housed, as was the custom, manuscripts concerned with Ṣūfīsm. In these tekkes were found some dervishes employed in copying manuscripts. In a general way, Ṣūfī literature developed and flourished in these tekkes and the bulk of it was in verse. I have already referred in passing to the fact that the majority of the Ṣūfī orders and their well-known branches in the world of Islam exercised an influence and extended their presence in Belgrade. The number of tekkes at the beginning of the mid-seventeenth century reached seventeen, although the circumstances that swept through buffeted Belgrade during the war of recovery led to the uprooting of the tekkes as well as to the destruction of their manuscripts and, by the nature of things, their literature and culture. Nothing important from the legacy of these tekkes has been left to us. [58]

3. The Qādiriyya

A review of several of these other orders can offer a balanced picture of the relationship of Balkan Ṣūfīsm to that in the wider, especially Central Asian, Islamic world. The Qādiriyya, for example, is among the most widespread of all Ṣūfī orders. It was founded by ‘Abd al-Qadir b. Abī Ṣāliḥ Jangīdūst, who was born in Jīlān, Persia, in 470/1077. He came to Baghdād and spent most of his life as a Ḥanbalī preacher. After his death in 561/1166, his followers attributed to him mystical teaching. His ṭarīqa, after his death, grew into a major Ṣūfī order and came into favour in the Ottoman world at a relatively late date. As we have indicated, the Sinan Qādiriyya tekke was founded in Sarajevo in the seventeenth century. By repute a tekke was founded in Prizren, Kosovo, at the same time.

However, it is with another shaykh from Iran that the Qādiriyya in Kosovo associates much of its early history. This is said to have happened at the end of the succeeding century. Shaykh Ḥasan al-Khurāsānī came as a wandering dervish to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia, which at

58. Muḥammad Mūfākū, Tārīkh Bilghrād al-Islamiyya, Kuwayt, 1987, p. 51.

![]()

106

that time was the centre of a Ṣūfī order that had established its own tekke. Shaykh Ḥasan joined with the other shaykh already in occupation, who told him to take a stone and throw it as far as he could. There he would build a tekke. The stone fell at Prizren at a distance of some 100 kilometres. The stone is still preserved and the tekke has been continued down to the holder of the office at the time of writing, Shaykh ‘Abd al-Qādir. Apart from Prizren, Gjakova was important in the spread of the Qādiriyya in Kosovo. It is especially associated with the life of Ḥajjī Shaykh Islām who lived in the locality in the early part of the nineteenth century, who was a tradesman who became rich and bought land. He went on pilgrimage and visited Baghdād. However, on his way south he was lost in the deserts of Arabia and only survived through his miracles. The shaykh of the Qādiriyya in Baghdād became aware of his sufferings and sent two of his Arab followers to rescue him. He was brought to Baghdād, stayed there for six months and was instructed further in the Qādiriyya. He was given the office of khalīfa, and returned to Gjakova. He owned lands in a number of small villages, including Damian, Postosel and Radost but gave up his wealth on his return from Baghdād and distributed it to the Ṣūfī novices, the fuqarā’. He refused to give his wealth to his two sons, this being unworthy of his religious mission; rather it was his duty to teach them the truth, and stories grew regarding his miracles, and his ability to travel at great speed and to distribute largesse to the poor. He established a ‘holy family’ through his offspring by his two wives:

Born by his first wife

(1) al-Ḥajjī al-Shaykh Maḥmūd (Šejh Mahmud)

(2) al-Ḥajjī al-Shaykh Ṣādiq (Šejh Sadik)

(3) al-Darwīsh Zayn al-‘Ābidīn (d. 1977/8; at his death the branch came to an end)

(4) al-Ḥajjī al-Shaykh Ḥaqqī (Šejh Hakija, d. 1977)

Born by his second wife

(5) al-Darwīsh Yūnus (Yunis)

(6) al-Shaykh Ibrāhīm (Sejh Ibrahim)

(7) al-Ḥajjī al-Shaykh ‘Abd al-Raḥīm (Šejh Abdurahim)

(8) al-Shaykh Islām

(9) al-Shaykh ‘Azīz (Šejh Aziz) [*]

*. At the time of writing, he is in his thirties and is Shaykh of Gjakova tekke.

![]()

107

Al-Shaykh Ḥaqqī (Hakija) was born in Gjakova on January 13, 1913. He studied and traded, but on the death of his parents he had to devote all his time to the support of his family and became an imam in a local mosque and so continued for thirty years. During this time he was put in charge of the Qādiriyya tekke, and under his influence tekkes of the Qādiriyya were re-opened in Kosovo and in Macedonia. New ones were founded or old ones revived, including the Qādiriyya headquarters in Sarajevo after a long period of closure.

The Qādiriyya has played an important part in the encouragement of Islamic literature in Bosnia and Kosovo, such as the poet Dervish Muhamed Gurani, born in Sarajevo in 1713, who laboured hard to maintain the tekke there. Muḥammad Mūfākū lists four surviving tekkes of the Qādiriyya in Gjakova. [59]

One of the most representative of the Bosnian Ṣūfī poets, both in Turkish and in aljamiado (composed in Bosnian Slav, though written in Arabic script) was Ḥasan Qā’imī Bābā (born in Sarajevo about 1630 and died in 1691), long regarded as a senior Khalwatī figure, but whose Qadirī sympathies, and his affiliations, embrace a wider Ṣūfī circle; the close study of his dīwāns by Jasna Šamić shows this. [60] His first spiritual master was a shaykh of the Khalwatiyya resident in Sofia. Later, however, he became attached to the Qādiriyya and directed the Sinan tekke in his native city.

Dr ‘Abd al-Raḥmān Zakī in his article on the subject of the Yugoslav Muslims and their heritage (published in al-Majalla [sijill al-thaqāfa al-rafī‘a], no. 44, 1380/1960, p. 25) says of this building:

Let us pass on to the tekke of al-Ḥājj Sinan (died 1640) erected in commemoration of the Turkish conquest of Baghdād. Sultan Murād III helped in its building. Nevertheless, the credit for its erection and establishment goes to al-Ḥājj Sinān Āghā who was one of the wealthy merchants of Sarajevo. This tekke is built from hewn stone which has been cut and polished with care. The most important of its parts is the samahane wherein the dervishes used to sing their hymns and recite their spiritual and mystical poems and odes. Its ceiling has been adorned with calligraphic ornamentations and decorations of the names of the most important of the Ṣūfī orders.

59. Muḥammad Mūfākū ‘al-Tanqa al-Qādiriyya fī Yūghūslāfiyā’, in al-‘Arabī, no. 285, 1982, pp. 82-6 (esp. 86).

60. Jasna Šamić, Dîvân de Kâ’mî. Vie et oeuvre d’un poète bosniaque du XVIIe siècle, Paris: Institut Français des Etudes Anatoliennes, 1986.

![]()

108

Dr Šamić gives a vivid account of the origin of this tekke (first described by Asboth, above):

One of the most beautiful monuments of the 17th century was the tekke of Hajj Sinān (1640) of Sarajevo [Plate 6]. Evliya Çelebi, who passed through Bosnia in the seventeenth century (towards 1650), claimed it to be one of the best known and the most beautiful tekkes of the region, even in the Jugoslav countries as a whole. This tekke belonged to the Qādiriyya order. There exist two versions of the history of its construction. The first tells that it was built by the Sarajevo merchant Sinān Aga at the behest of his son Muṣṭafā Pasha, the silāḥdār of Sulṭān Murād IV (1623-40). According to the other version it was built by the silāḥdār, Muṣṭafā Pasha himself, in the name of his father, Sinān Aga.

In our day, it is to be found on a hill of Sarajevo, in the Sagardzije quarter, beside the ‘Vrbanjusa’ mosque and its cemetery. The building is of cut stone. The great door gives access to the court where are to be found the tombs of the Shaykhs; the türbe of Sinān Aga and of his wife are in the cemetery behind the court. To the right are found the rooms that the Shaykhs of the epoch used to inhabit. To the north of the tekke is the guest chamber, müsāfirhāne and the chamber where the sick are cared for; both are extended by a large semāhane. The miḥrāb is to the left, the stairway of the balconies of the semahane to the right. On the wall are suspended different musical instruments (nine percussion instruments, birbir halka, kudum, zil etc) and a great rosary (tesbīḥ). The traces of a rosette are left on the wall. On the floor several carpets and sheepskins act as the sajjāda (prayer-carpet). [61]

Having become involved in a riot, Ḥasan Qā’imī had to leave Sarajevo. He settled in Zvornik where he died about 1103/1691-2. He left his permanent mark through his verses and, personally, on the life of the dervishes there. His tomb is at Kula, a short distance from Zvornik. Near his tomb a Qādirī tekke was subsequently built. Ḥasan Qa’imī was reputedly the shaykh of another tekke on the left bank of the Miljacka in Cumurija street in Sarajevo, which was named after him. Originally his private house, it was transformed into a tekke in 1079/1667/8; the tekke belonged to the Khahvatiyya, but Jasna Šamić stresses that it is above all with the Qādiriyya in Zvornik that the name of Ḥasan Qā’imī is most firmly linked.

His major poetic achievements were two dīwāns in Turkish and sundry aljamiado didactic poems.The second dīwān, entitled Wāridāt (inspirations of a mystical kind), are predictions of future events — one of these

61. ibid., p. 244.

![]()

109

was the Ottoman conquest of Crete in 1669. However, the first dīwān contains a rich collection of symbolic Ṣūfī verse. The doctrine of Waḥdat al-Wujūd is revealed and great devotion is shown to ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī who is described as the ‘saint of saints’, the ‘spirit of the terrain’ and ‘the king of saints in West and East’. It will be through his help and ultimately the help of the Divinity that the ‘blond Europeans’ Banū’l Asjar will be ultimately routed. Ḥasan Qā’imīs poems are strongly rhythmic and they were intended to prepare the heart for participation in the dhikr within a Ṣūfī tekke. [62]

4. The Mawlawiyya

The Mawlawiyya became an important order throughout Balkan Islam and especially in the area of Bosnia and Hercegovina. According to Džemal Ćehajić, this may be observed in the influence of the thoughts of Rūmī on Bosnian poets and writers and in the way the order became influential in shaping Bosnian social and economic life. The presence of the order is recorded as early as the fifteenth century when its zavija was founded in Sarajevo (first at Šehovoj Korija and later at Bendbaša). Prominent in this activity was ‘Īsā-beg Ishaković, governor of the so-called Western Parts (1440-6) and the second Bosnian Sandžak-beg (1464-9). A tekke was built on the right bank of the Miljacka river on the borders of the city before the Bosnian campaigns of Sultan Mehmed in 1463. The building included a müsāfirhāna. This was an inn where poor Muslim scholars, military personnel and wayfarers were accommodated. Meat, rice and bread were cooked there and served free of charge, the remainder being distributed to the poor children of Sarajevo. Guests were entertained for three days. From the description of the Mawlawī zavija by Evliya Çelebi in his Siyāḥat-nāme, it would appear to have been an active and well-endowed religious centre. The Sarajevo chronicler Mulla Muṣṭafā Bašeskija recorded that the tekke was extensively restored in 1196/1762. Many of its activities continued till well into the twentieth century.

The tekke was one of the centres for the study and recitation of the Mesnevi of Rūmī. It was also actively encouraged at Mostar in Hercegovina. A number of leading Bosnian writers and poets were members of the Mawlawī order, and included some who wrote in Persian as well as Turkish.

62. ibid., p. 16, 17, 18, 19 and passim.

![]()

110

Their Mawlawī works pondered such themes as cosmic love, moral rearmament and aspirations of the soul towards absolute beauty. Characteristic of these writers and thinkers were their humanism and tolerance and the welcome they gave to converts. Ćehajić notes the success they achieved among Orthodox Christians in some areas of Bosnia and Hercegovina.

Four noted poets influenced by Rūmī’s teachings in the Muslim regions of Yugoslavia were Darwīsh Pasha Bāyazīd Agha-Zāde (Bajezidagić) al-Mūstārī (d. 1603), who wrote an equivalent of the Mesnevi together with poems in praise of Mostar, his home town; Ḥabīb Ḥabībī-Dede (d. 1643), who preached renunciation; Rajab-Dede ‘Adanī (d. 1684), who was head of the tekke in Belgrade and wrote rhymed glosses entitled Nakhl-i tajallī (the date-palm of transfiguration) to the love poems from Rūmī’s Mesnevi; and Ḥasan Naẓmī-Dede of Sarajevo (d. 1713), who was deeply influenced by the same work and whose own dīwān is devoted to dependence on God (tawakkul) and devotion to Him. [63]

In contrast to the Mawlawiyya, the Baktāshiyya had far greater importance and played a far more significant role in the religious and social life of Macedonia and Kosovo in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The link between the Baktāshiyya and the Albanians was one obvious reason. The Pashas who ruled Macedonia and Albania during these two centuries had close relations with the Baktāshiyya. Affiliated to it there were janissaries, — most čifluk [64] owners, army officers, craftsmen and some of the free peasants. However, only at this period did the Baktāshiyya gain a strong presence even if several of their tekkes had been founded earlier, at Kosovska Mitrovica, Kacanik, Krkler and in a number of the major towns of Macedonia and Kosovo.

5. The Khalwatiyya

The Khalwatiyya order has as its founder ‘Umar al-Khalwatī, who died in Tabriz in 800/1397. It derives its name from the ‘retreat’, khalwa or khalva (Ar. cell), that figured prominently in the much earlier

63. Much has been written in Bosnia on Rūmī’s verse, inter alia a short article by Džemal Ćehajić, ‘Some characteristics of the teachings of Galāluddin Rumi and beginning of dervish order of Mawlawis in Bosnia and Herzegovinia’ (with English summary) in Prilozi, Sarajevo, XXIV, 1974 (printed 1976), pp. 85-108.

64. Çiftlik — farm or privately owned estate.

![]()

111

Kubrāwiyya order in Central Asia. This was the practice of entering into a retreat for periods of up to forty days, and fasting from dawn till sunset in a solitary cell. The Khalwatiyya began as a sub-order of the ‘illumina- tionist’ Suhrawardiyya order, and it spread to Shirvān, adjacent to Bākū, and among the ‘Black Sheep’ Turcomans of Azerbaijan. After the conquest of Istanbul it gained a considerable following among the population and in the Ottoman military forces. Sub-orders were founded in many parts of Anatolia, Syria and Egypt. At first, activism and a dubious orthodoxy brought the Khalwatīs under the suspicion of the authorities and they were in disagreement on a number of issues with the ‘ulama’. However, by degrees, they moved towards a comparatively orthodox form of Ṣūfīsm. Its fortunes revived during the reign of Sulaymān the Magnificent (926-74/1520-74), and during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it produced a number of outstanding shaykhs and scholars. At the beginning of the latter century, out of the Qarabāshiyya branch of the order, there emerged Muṣṭafā Kamāl al-Dīn al-Bakrī, a Damascus shaykh (d. 1749), who undertook missionary journeys and many labours to gain followers and exert his influence in Syria and Egypt. While several of his predecessors openly adhered to the ideas of Ibn al-‘Arabī in regard to waḥdat al-wujud, he himself opposed monist, or rather theomonistic, views, and stressed the separate identities of God and the human soul. [65]

Apart from Bosnia and Hercegovina, the Khalwatiyya was, and perhaps still is, the most widespread order in Kosovo and Macedonia. Its members are divided into three principal branches, the Qarabāshiyya, with their asitane, or headquarters, in Prizren, the founder being Shaykh Osman Baba from Sereza, who established his tekke there about 1699/1700. It developed many branches in Albania and in the region of Skopje. The Jarrāḥiyya is named after Shaykh Nūr al-Dīn Dzerahi, who was born in Istanbul in 1673, went later to Egypt, but returned to Istanbul where he died in 1720. Several of its tekkes were established in Macedonia.

The Ḥayātiyya, the sub-order founded by Shaykh Muḥammad Ḥayātī, who was born in Bukhara [66] and allegedly reached Kičevo in

65. See the article ‘Khalwatiyya’ by F. de Jong in The Encyclopedia of Islam (new edn), pp. 991-2.

66. On the Ḥayātiyya in the region of Ohrid, Kičevo, Struga and elsewhere in the Balkans see the article by F. de Jong on the Khalwatiyya cited above and Džemal Ćehajić, Derviski Redovi u Jugoslavenskim Zemljama, op. cit., pp. 112-15. The most specific study is that by Galaba Palikruševa, ‘Derviškiot red Halveti vo Makedonija’ in Zbornik na Štipskiot Naroden Muzej, no. 1, Stip, 1959. I have been informed by the shaykh of the Ohrid tekke and his wife that there are a few small inaccuracies in the silsilas printed in the article which they checked with the tekke scrolls preserved in Ohrid.

![]()

112

Macedonia in 1667, is of considerable local importance. He later went to Ohrid, where he died at the beginning of the eighteenth century. F.W. Hasluck reports that the date over the gate of their ruined tekke at Liaskovik (1211/1796/7) seems to confirm the general accuracy of the chronology of their arrival in Macedonia. Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā in his Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya mentions that a Baktāshiyya tekke (founded by Baba Abidin in 1887) also once existed in this town which he spells Lasqūwīk (today Leskovicu), lying just within Albania north of the Greek border.

6. The Naqshabandiyya

The Naqshabandiyya was originally founded by the Khwājagān or ‘masters’, specifically of Bukhara, and by Bahā al-Dīn Naqshaband (1318-89). An early link between it and the Baktāshiyya is through the person of Ahmed Yasavī, who is revered by both. [67] It was introduced into Turkey by shaykhs from Transoxania. It also enjoyed the support of the Mughal emperors in India, and the Syrian lodges of the order were founded by a missionary from India. In the eighteenth century its reputation in Arab Asia was enhanced through the travels and writings of Shaykh ‘Abd al-Ghanī al-Nablusī, who enjoined its followers to observe to the letter the rules prescribed by the Sharī‘a and to engage in silent meditation (dhikr khafī), as had allegedly been laid down by ‘Abd al- Khāliq Gujduvānī (d. 1179 or 1189) whose practice in this respect differed from the Yasaviyya, where the dhikr of the ‘saw-mill’, the zikr-i-djahriye, was a public dhikr recited with a loud voice. [68]

The distinction between these two forms of dhikr reflects the origin of the disclosure of the dhikr by the Prophet to his Companions.

67. On the connection between Ahmed Yasavī and the founder of the Gujduvānī order, ‘Abd al-Khāliq Gujduvānī (d. 1179 or 1189), who established the ‘silent dhikr, see Irène Mélikoff, ‘Ahmed Yesevi and Turkic Popular Islam’, Utrecht Papers on Central Asia, Utrecht Turcological Series, no. 2, 1987, pp. 83-94. The Gudjuvānī order was the parent order from which the Naqshabandiyya of Bahā’al-Dīn Naqshaband (1318-89) issued.

68. ibid., p. 89. While the dhikr of the Naqshabandiyya is khafī, ‘silent’, the Yasaviyya is erre, ‘sawmill’, or jahriyya, ‘loud-voiced’.

![]()

113

According to Shaykh Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā in his al-Risāla al-Aḥmadiyya, the dhikr khafī was a tradition adopted from the Caliph Abū Bakr who, once meditating in a cave with the Prophet, received it in a state of deep meditation and prayer with his eyes closed. As for the dhikr jahrī, this was a tradition adopted from ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib who, after being told to be seated in the Prophet’s haḍra, was told to close his eyes and listen so as to receive the threefold dhikr of the kalimat al-tawḥīd, the forgiveness of the divinity, from the mouth of the Prophet. [69]

Much influenced by the laity, the Naqshabandiyya differed from other orders in having the character of a simple religious association. Unlike the Baktāshiyya, with its intense devotion to ‘Alī, the first link in the Naqshabandī chain of authority after the Prophet himself is the first Caliph, Abū Bakr. The order prides itself in its chain of authority (isnād) that shows that its way was that originally proclaimed by the Prophet’s Companions, the Ṣaḥāba. [70]

According to Ḥāmid Algar, who has written authoritatively on this ṭarīqa, [71] the Naqshabandiyya first appeared in the Balkans in the fifteenth century in the person of Mullā ‘Abdullāh Ilāhī (d. 896/1490-1) who was the founder of the West Turkish branch of the order. After journeying to Khurāsān and Transoxania, he became one of the pupils and novices (murīdīn) of the Pīr, Khwāja ‘Ubaydallāh Aḥrārt (d. 845/1441), in Samarqand. After severe khalwa, fasting and meditation at the tomb of the order’s founder he returned westwards, as khalīfa of his master, and led an active life in Istanbul. Later he moved to Yenice-i-Vardar in Macedonia although the expansion of his ṭarīqa in the Balkans cannot be said to have begun there.

The first Naqshabandī tekke in Bosnia was built in 1463 in Sarajevo by Iskender Pasha, Beylerbeyi of Rumelia and four times governor of Bosnia. Adjoining it he built a bridge and a miisafirhane to accommodate visitors to the tekke. Another Naqshabandī tekke was built in Sarajevo in the nineteenth century, and this, by means of spiritual welfare offered to others, carried on the work of Iskender Pasha’s tekke, which no longer survives. As Ḥāmid Algar shows, it is outside Sarajevo in other tekkes in the Bosnia region that the Naqshabandiyya has left a profound influence on the Bosnian Muslims. Several of these tekkes date back to

69. Aḥmad Sirrī Bābā, op. cit., p. 69.

70. R.S. Bhatnagar, Dimensions of Classical Ṣūfī Thought, Delhi, 1984, pp. 175-6.

71. ‘Some notes on the Naqshabandī ṭarīqat in Bosnia’, in Die Welt des Islams, 13, 1972, pp. 168-203, reprinted in Studies in Comparative Religion, 9, 1975, pp. 69-96.

![]()

114

the eighteenth century and are still active at the present time. [72]