V. Intelligence in the Mongol Empire

The Rise of Jenghiz Khan (a New David?), Military Genius, Author of the Great Yasaq, Mongol Law Code — Conquest of North China, Manchuria, and Kara-Khitai — Jenghiz Khan, Muhammad II, Caliph Nasin — Conquest of Muhammad Khwarizmian Empire — Expedition of Jebe and Sübötäi in Caucasus and Russia—Jenghiz’s Organization of Intelligence, His Post Service — Chinese Post — Arabs on Chinese Intelligence — New Mongol Conquest in Europe, Asia, and China — Jenghiz’s Successors and the Post Service — Western Information on the Mongol Post, de Piano Carpini, Longjumeau, Rubruck — Marco Polo on the Mongol Chinese Post Service — Report by Oderic and the Arab Batuta on the Mongol Post — Organization of the Mongol-Chinese Post Service.

The geographical discoveries of the Arabs remained unknown to the west, which had an extremely vague knowledge of the lands beyond the Caucasus and in the Far East. This is illustrated by their belief that there existed in those regions a huge kingdom ruled by Prester John, a holy and righteous man whose power was immense and who would help the Christians in their war with the Saracens. During the Second Crusade (1147-1149) rumors that Prester John had already attacked the Saracens spread among the Crusaders and in Europe. The disastrous end of the Crusade showed that such hopes were vain and the belief in Prester John faded.

Another legendary account stirred Europe about 1221 when the Crusaders, after conquering Damietta in Egypt, were beleaguered in the conquered city by the Sultans of Egypt and Damascus. The report was spread by Jacques de Vitry, Bishop of Ptolemais, who wrote to the Pope, to the University of Paris, the Duke of Austria, and to Henry III of England that a new hope had arisen for the Christians.

262

![]()

![]()

263

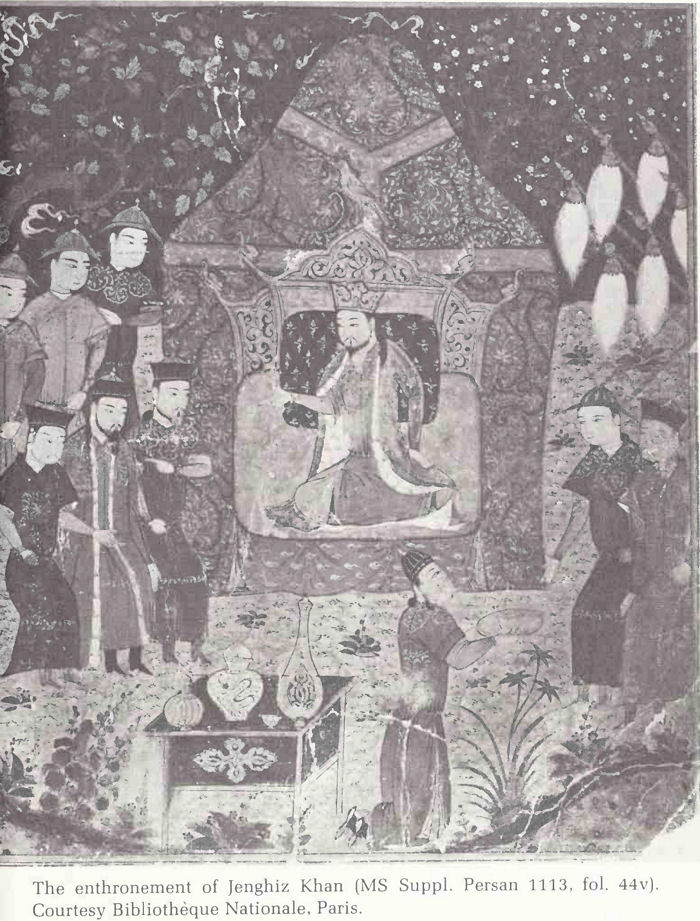

The enthronement of Jenghiz Khan (MS Suppl. Persan 1113, fol. 44v). Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

![]()

264

A new and mighty ruler, David of India, was about to invade the lands of the unbelievers with an army of unparalleled size, to help the Christians.

Actually, a mighty ruler was arising in the Far East, building an immense new empire. But it was not a new David. It was Temujin, the peerless son of Yesugei, baghatur (chieftain) of the Kiyats, a minor Mongol clan. He was born about 1167, in northern Outer Mongolia. The hardships he had suffered in his youth served to strengthen his native dynamic vigor, and he became a valiant young warrior who soon found a few faithful followers, and who displayed great courage and skill in the campaign against the Tatars and the tribes of Naimans and Märkits who had abducted his young bride. Thanks to his military valor and diplomatic talent, he succeeded in unifying the disorganized and impoverished Mongol tribes who were wasting their energy in mutual conflict. In 1206, at a solemn assembly of the nation (quriltai) Temujin Khan was proclaimed emperor and given the new name Jenghiz, which probably means strong, robust, or rightful ruler.

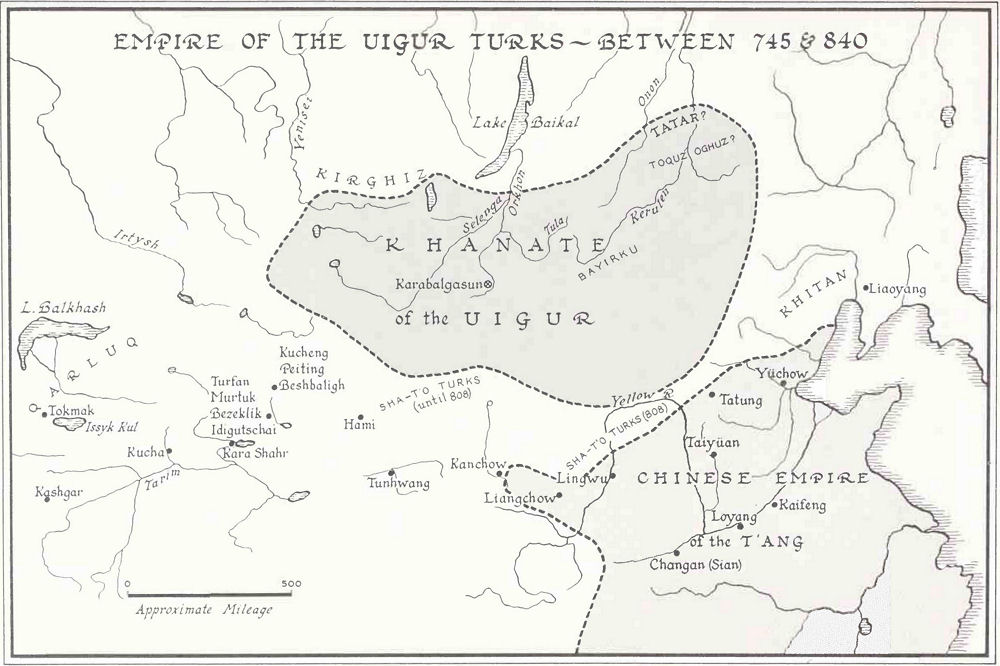

His first task was to strengthen the army. He chose the decimal system in military organization with units of ten, one hundred, and one thousand warriors. The ninety-five battalions of one thousand men, each commanded by his faithful followers, were completed by the imperial guard — the Bagaturs — ten thousand strong. His military genius forged the men of the nomadic tribes into a formidable, well-disciplined, and determined army ready for new conquests. Jenghiz did not join any religious group — although his people were under the influence of Shamanism — for his god was the “Eternal Blue Sky” which, he believed, had predestined him to become master of the whole world. Before any important decision he offered prayers and libations to the “Eternal Blue Sky,” but he never permitted the Shamans to influence the political life of his nation. He was illiterate, but after defeating the Naimans in 1214 he quickly grasped the importance of literacy which the Naimans had derived from the Uigurs. The latter, a Turkic tribe, had settled in eastern Turkestan (modern Sinkiang) in the middle of the eighth century and had attained quite a high level of civilization. They had their own alphabet, based on that of the Sogdian which, in turn, derived from Aramaic letters. Jenghiz ordered the captured secretary of the Naiman khan to teach a few selected and intelligent young men who were in charge of the administration of the Mongol Empire how to write.

![]()

265

So it happened that the Uigur script and culture were adopted by the illiterate Mongols.

Jenghiz also gave to his people a new Mongol imperial legal code which is contained in the Great Yasaq, regarded by the Mongols as the product of the divinely inspired mind of the founder of their first dynasty. No complete copy of the Great Yasaq has been preserved, but its contents can be reconstructed from the works of several oriental medieval writers. It appears that it was based on the old Mongol and Turkic tribal traditions which were gradually thoroughly revised and transformed by Jenghiz and his advisers, and welded with a monarchical concept of the state. Besides some general precepts, it contained principles of international law, rules for the organization and discipline of the army, administrative maxims, criminal, civil, and commercial laws. The Persian historian Rashid al-Din and the Arab writer al-Makrizi date the promulgation of the Yasaq from the great quriltai of 1206. This first edition was supplemented by new ordinances proclaimed in 1210 and 1218. Probably at the session of the quriltai in 1218 the basic laws promulgated in 1206 and supplemented in 1210 were systematized and approved in written code. It seems, however, that the Great Yasaq was only finally revised and completed by Jenghiz about 1226.

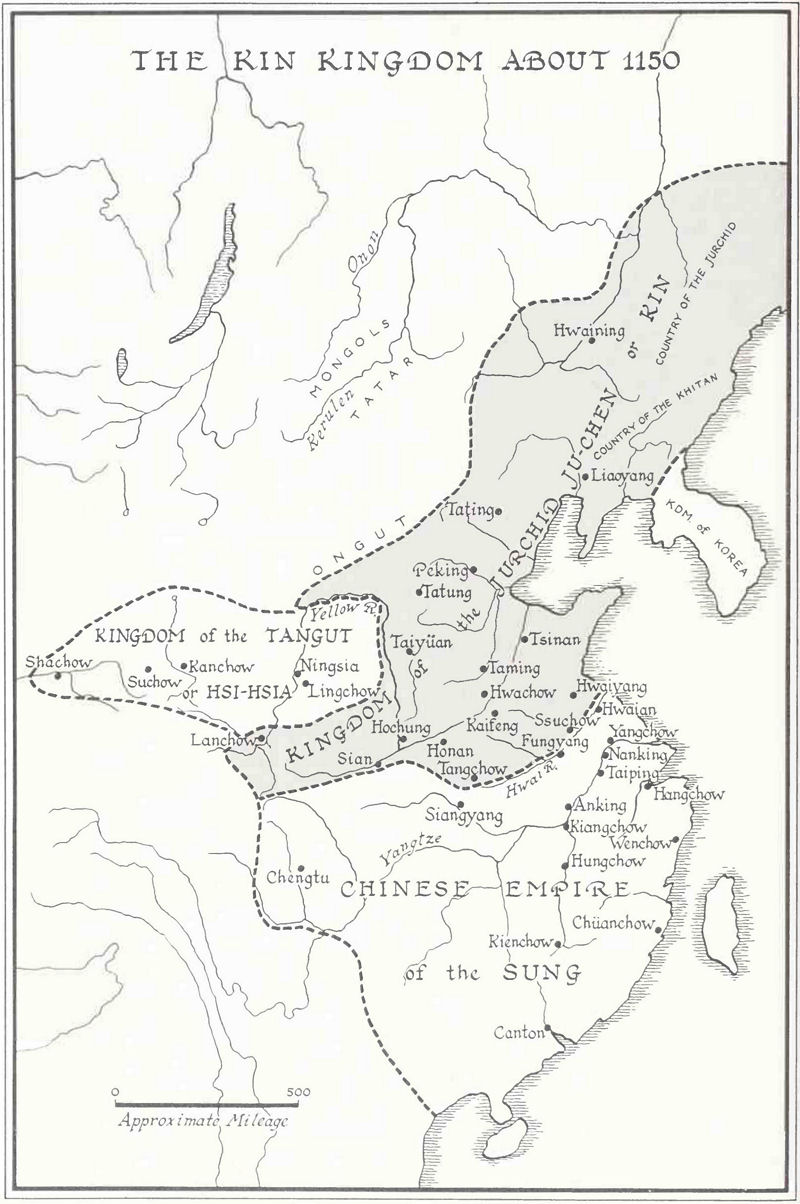

After completing the reorganization of the Mongol army and the administration, reinforced by the submission of the clans of the forest people and the Uigurs, Jenghiz was ready for conquest. He attacked the kingdom of the Tanguts (Hsi-Hsia), a people of Tibetan origin. They agreed to pay tribute to the Mongols. He contented himself with this act of submission, because his main goal was the conquest of the northern part of China controlled by the Kin (Chin) dynasty, the Tatars who had wrested northern China from the Sung. The campaign against the Kin began in 1211. Jenghiz proved once more to be a skillful military leader. Dividing his army, he attacked in several places at the same time, and his guard penetrated the Great Wall at a point where the enemy did not expect an attack.

The Mongols occupied the region north of Peking, seizing the imperial herd of horses. The Khitans of southern Manchuria revolted and submitted to Jenghiz. In 1214 the Kin emperor signed a peace treaty which, however, did not last, and in 1215 Peking surrendered to the Mongols. North China and Manchuria became integral parts of Jenghiz’s empire. Moreover, the Khan also had at his disposal a corps of Chinese army engineers and some well-trained Chinese civil servants.

![]()

266

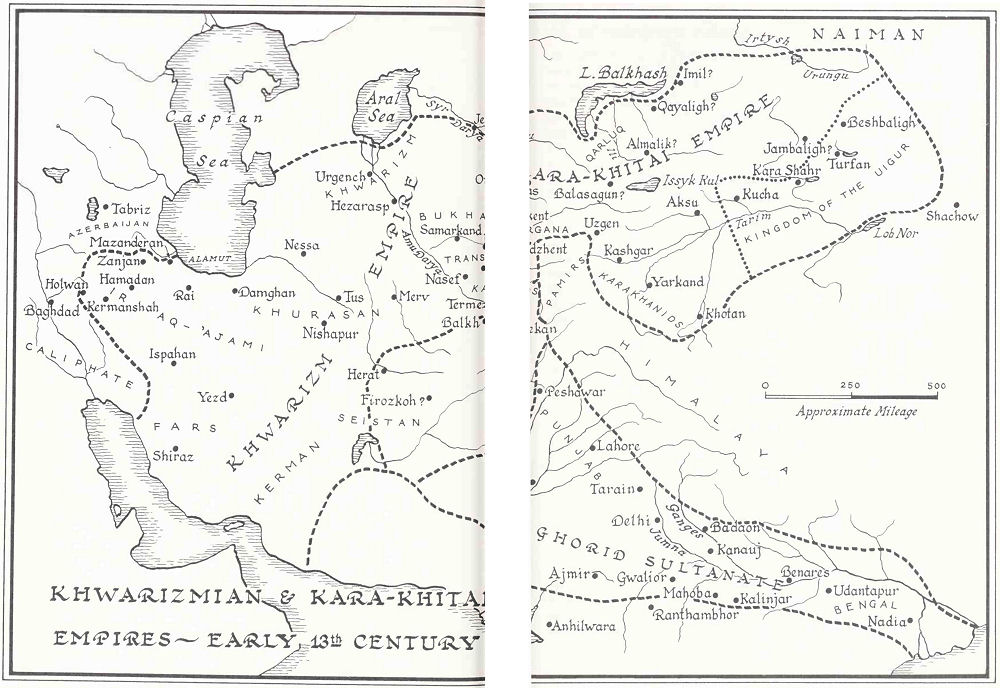

The Chinese engineers helped the Mongols build war machines for the conquest of fortified cities, an art which the Mongols did not hitherto possess. After conquering the Kin Empire, Jenghiz crushed the Kingdom of Kara-Khitai in Turkestan then ruled by Küchlüg, the son of the last Naiman khan previously defeated. Jenghiz’s noyan (general) Jebe cleverly exploited the religious situation in the kingdom where Nestorian Christians and Muslims were persecuted by the Buddhist rulers. After proclaiming religious freedom, Jebe won over the population to the Mongol rule and was able to send the head of Küchlüg to Jenghiz Khan as a proof of his victory.

After China and Kara-Khitai came the conquest of another empire formed by Muhammad II, of Turkic origin, who, from his original possession of Khwarizm in the Amur delta, whence his father had expelled the Seljuk rulers, had gradually extended his sovereignty over Turkestan, Afghanistan, and Persia. Thus he formed an imposing Khwarizmian Empire over which he ruled as shah. In this way he gradually attained a dominant position in the whole eastern part of the Muslim world and dreamed of the deposition of the Caliph of Baghdad, whom he hoped to replace.

After learning of the Mongol successes in China, Muhammad sent an embassy to Jenghiz bearing his congratulations. But his main objective, however, was to obtain intelligence on the khan’s forces. The embassy was well received, for Jenghiz Khan needed many Muslim products for the better equipment of his army. He was prepared to recognize the Khwarizmian shah as the ruler of the West while emphasizing that he was the ruler of the East. Jenghiz therefore sent an embassy to the shah composed of Muslim merchants, and a commercial contact was established intended to guarantee an unmolested caravan trade between the two empires.

But even the Caliph Nasir of Baghdad hoped that the great new ruler would save him from the danger which threatened him from the Shah Muhammad. He obtained his intelligence about Jenghiz Khan’s success and power from Nestorian Christians whose communities were dispersed far and wide throughout Asia, and the rumor that the great ruler was a Christian must have originated in this community. Through the mediation of the Nestorian patriarch residing in Baghdad, the caliph sent an envoy to Jenghiz Khan. In order to pass through Muhammad’s lands without being suspected, the messenger’s head was shaved. With a red-hot instrument his credentials were branded into his scalp, and a blue pigment was rubbed into the burns.

![]()

267

Empire of the Uigur Turks between 745 and 840

![]()

268

The Kin Kingdom about 1150

![]()

269

He was made to learn his message by heart and was sent through Khwarizmian lands only after his hair had grown long enough to cover the brand. He reached Jenghiz’s land, was caught by his guards and brought before the Khan. Jenghiz, who never lost an opportunity of obtaining additional intelligence on foreign peoples and lands, was pleased to learn from the envoy that Muhammad was not the uncontested ruler of the West, that he was not the head of the whole Muslim world, and that the Muslims were being invaded by white people from far-off lands — the Crusaders. But, although he had heard about the riches and beauties of Baghdad from the Muslim merchants, he was not interested in the caliph’s troubles, believing that commercial relations with the shah would be more profitable to him.

In the meantime, however, the situation on the eastern frontier of the shah’s empire had changed because of the unexpectedly rapid conquest of Kara-Khitai. This proved to be a shock to the shah, who began to concentrate his army in order to protect his country against possible threats from the victorious Jebe.

Upon reaching Samarkand after an unsuccessful campaign against the caliph, the shah received a message from the frontier fortress of Otrar informing him that the governor had captured a caravan of Muslim merchants coming from Jenghiz’s lands and that there were without doubt Mongol spies among them. Forgetting the commercial agreement with the khan, the shah gave the order to put them all to death. All the members of the caravan were massacred, together with Jenghiz’s personal envoy, and their belongings looted by the commander of Otrar. Only one man escaped, and he related what had happened to Jenghiz Khan, who threatened formidable vengeance, and began preparations for the conquest of the shah’s empire after the latter had refused to extradite the governor who had perpetrated the massacre.

The famous war with the great Muslim Empire began in the autumn of 1219. This attack on Muslim lands by a powerful leader gave birth to that legendary rumor which had spread among the Christians that a new David had appeared in the East, and, because he had attacked the Muslims, he must be a Christian who would therefore help the Crusaders to conquer the Holy Land.

Jenghiz Khan made good use of all the information he had obtained about Muhammad and his empire from his own spies as well as from the Muslim merchants. He learned that the shah was an intolerant man, that, although a Muslim, he had started a war against the caliph, ravaging the lands of Muslims and Christians, which had aroused hostile feelings against him from among his own subjects.

![]()

270-271

Khwarizmian and Kara-Khitai Empires, Early Thirteenth Century

![]()

272

He invaded the shah's lands not only from the north by way of the Syr Darya, but also from the east. After crossing the Pamir passes during the winter into the valley of Fergana, Mongol fighters led by Jenghiz’s son Jöchi used the same quick maneuvres they had employed before in China, the divisions being wholly dependent for their movements upon little banners and field insignia of various colors and shapes. This tactic helped them to attack, scatter, and reform tor a new onslaught before the shah’s men could comprehend the intention of the attackers. Jenghiz Khan’s other army, led by another son, Tolui, advanced against Bokhara and Samarkand. Bokhara was seized and destroyed, the citadel Otrar stormed, and the governor who had massacred Tenghiz Khan’s envoys was put to death under torture. Samarkand was taken and Jenghiz Khan sent two of his best officers, Jebe and Sübötäi, to pursue the shah, who had fled from Samarkand to the interior of his own country. However, the shah failed to organize any kind of resistance. He could not even kindle among the Muslims a religious feeling against the heathen attackers. It was generally known that the immediate cause of the invasion was the massacre of the Muslims who had been sent by Jenghiz Khan as ambassadors and merchants to the shah. The latter succeeded only in evading his pursuers. In the end, seeing that all hopes of escaping his pursuers were vain, he took refuge on a small island in the Caspian Sea, where he soon died on February 10 1221.

The son of Muhammad, Jelaleddin, endeavored to reorganize that part of his father’s empire which was still unconquered by the Mongols, but, in spite of his heroic attempts — he even won one victory over the Mongols — his lands were devastated in a war of annihilation. His courage saved him from death during the great battle with the Mongols on the Indus river. He found refuge in India, whence he returned after Jenghiz’s death to Afghanistan and attacked Persia; but, pursued by the Mongols, he was forced to flee to the Kurdish mountains where he was slain by a peasant.

Having completed their task after occupying the southern shore of the Caspian Sea and reaching Azerbaijan, the two generals Jebe and Sübötäi made some explorations beyond the Caspian Sea. With the permission of Jenghiz Khan they made an incursion into the Caucasus, defended by the Georgian Christian army, the Alans, and Cumans, and invaded Russia. In May 1223 the Mongols defeated the Russian princes together with their allies the Cumans, in the battle beside the Kalka.

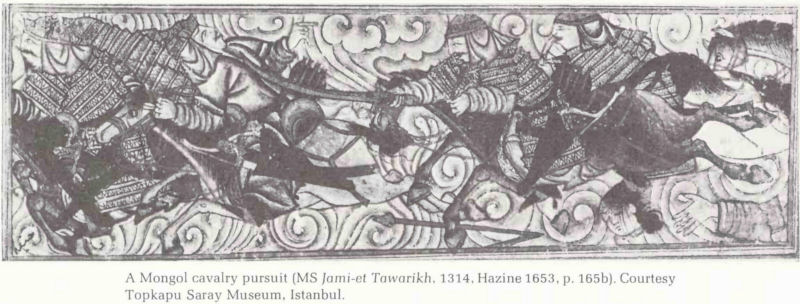

![]()

273

A Mongol cavalry pursuit (MS Jami-et Tawarikh, 1314, Hazine 1653, p. 165b). Courtesy Topkapu Saray Museum, Istanbul.

![]()

274

This was the tragic end of the legend that a new David had arisen who would help the Christians defeat the Muslims.

Before his death, Jenghiz Khan had been able to defeat and subjugate the Tangut realm of Hsi-Hsia whose ruler had refused to send auxiliaries to support the campaign against Muhammad II. He launched the expedition in the spring of 1226. Although weakened by a serious accident suffered while hunting, Jenghiz Khan managed to direct this destructive campaign and, in the summer of 1227, his generals captured the Tangut capital Ning-hsia. The Tangut king surrendered, but Jenghiz Khan, now seriously ill, was unable to accept either the surrender or the magnificent gifts brought by the defeated king. He issued the order, nevertheless, to put him to death.

From among his three surviving sons, Jagatai, Ogödäi (Ogotai), and Tolui, Jenghiz appointed Ogödäi as his successor, admonishing Tolui and Jagatai to live peaceably with each other. He died on August 8, 1227, after giving orders to exterminate all the inhabitants of the conquered city and advising his sons how to pursue the war against the King of Gold, the Mongol’s hereditary enemy, after his death.

So it happened that one single, ingenious, intelligent, but unscrupulous and barbarian ruler founded an empire which exceeded all other conquests previously made in the world’s history. Fire, blood, and ruins marked the path of the cruel Mongol hordes, and the subjected peoples were ruled with an iron hand by the conquerors.

One may ask how the scion of a barbarian nomadic nation could have obtained such an immense military and political success in such a short time. It was first of all the Mongol army, organized and trained by the military genius of Jenghiz and inspired with the idea that its leader was predestined by the “Eternal Blue Sky" to become master of the world. Jenghiz’s army was greatly superior to the armies of all his neighboring nations, even the experienced Chinese warriors.

The other important factor which facilitated bis conquests was Jenghiz s understanding of the importance of possessing good intelligence about any nation about to be conquered. The Mongols enjoyed commercial relations with China before the time of Jenghiz Khan, especially through the intermediary of the Tungus, and knew more about that country than European nations. However, Jenghiz’s best informers were the Muslim merchants, as they controlled all the trade between China and Central Asia.

![]()

275

They knew all the routes and, being highly cultivated, were good observers and were well acquainted with the economic and political situation of every district with which they traded. By reason of their trade they had numerous contacts in many quarters, and all the lands from Persia to China through which their caravans passed were well known to them.

Jenghiz Khan had had a long acquaintance with them, often entertaining them at his court, listening for hours to their information, and surmising how important their experiences would be for the achievement of his plans. They gave him freely all the information he needed because they saw that his strict régime would make the connection between distant countries easier, and that this would garner greater profits for their trade. This explains how the Muslim capitalist merchants became ardent supporters of the Mongol cause.

Besides this. Jenghiz Khan would send spies into the enemy lands he wished to subject, trying to obtain any possible information on the military strength of the neighboring nations and on the rivalries among the members of the ruling class, which his diplomacy could exploit to weaken the adversary. Numerous scouting parties preceded the main armies probing the terrain, observing the movement of the hostile army and reporting to headquarters all intelligence discovered.

Jenghiz Khan endeavored to gain intelligence not only about China and the Khwarizmian Empire, but also about the countries far beyond his immediate goal which could be attacked after those conquests already planned, or, perhaps, only under his successors. This is shown by his sending an expeditionary force of 30,000 men under Jebe and Sübötäi beyond the north coast of the Caspian Sea. He gave his two generals three years to investigate and conquer the lands beyond the Caspian Sea, to find out what kind of peoples dwelt there, how important their realms appeared to be, and how strong were their armies. We have seen how fateful this decision of the khan was to be for the Caucasian peoples and for Russia. During his stay on the shores of the Caspian Sea in winter quarters, Sübötäi sent spies into all neighboring territories. He tried to obtain all possible intelligence from prisoners, merchants, and other informers about the white race, about European peoples and realms. The intelligence obtained by him on Russia and Central Europe was so precise that Jenghiz Khan’s successors were able to draw up on this basis a complete plan for the conquest of Europe.

![]()

276

Sübötäi himself led the first part of this conquest, profiting from the intelligence he had gathered during the three years of his reconnaissance from the shores of the Caspian Sea.

Muhammad II, Shah of the Khwarizmian Empire, lost his battle and his life because of lack of good intelligence as to the Mongol strength. He obtained his first information on Jenghiz Khan’s army from the Muslim envoys whom the khan had sent to his court. From this information he concluded that he had a good chance of blocking the Mongol advance, because his army was larger and his realm had many strong and well-garrisoned fortresses which the Mongol cavalry could not conquer. He did not know that, in the meantime, Jenghiz Khan had acquired, with the help of Chinese engineers, heavy machinery, catapults, and artillery for the destruction of the walls of fortified cities. Instead of concentrating his troops against the advance of the mainstream of the Mongol army, Muhammad dispersed them in the fortified places, without paying sufficient attention to securing the communications between them.

Jenghiz Khan was, however, also well aware that a ruler needs to be well informed about the situation in conquered countries and that he has to be in continuous contact, not only with the generals of his armies, but also with his homeland. In conformity with this important objective the organization of post-horse stations (jami) along the imperial highways became a major task of the Mongol Empire. This organization was initiated by Jenghiz and is mentioned in his Yasaq. Each station or jam, erected at a distance of a day’s journey, had to be provided with horses (often as many as twenty), fodder, and food and drink for the travellers. An annual inspection of each jam was ordered. The service was free for the use of ambassadors and the khan’s messengers. Post service taxes and duties, and a levy of cattle and forage were imposed.

The jami were established along the road at every twenty-five or thirty miles. The imperial messengers called arrow-messengers (elci) rode with bandaged head and trunk in order to make known their character and the importance of their message, and were entitled to the best mounts as relays at the jami. How well this new Mongol institution functioned is illustrated by the ride made by Sübötäi from the northern coast of the Caspian Sea to the winter quarters of Jenghiz between Samarkand and Bokhara where Jenghiz was waiting for him. The khan urgently needed the report on Sübötäi ’s intelligence, collected on his rapid ride throughout the Khwarizmian Empire in pursuit of Shah Muhammad. Sübötäi, riding as an arrow-messenger on the new post road at the utmost speed, by day and by night, stopping at the jami only to exchange horses,

![]()

277

sometimes stopping to eat a meal or take a few hours’ sleep, covered the 1,200 miles separating him from his master in little more than a week. Sübötäi’s report that there was no new army in the west to be accounted for decided the further strategy of Jenghiz. He gave Siibötäi and Jebe permission to cross the mountains beyond the Caspian Sea, scout and raid the countries behind it, and return to Mongolia after three years through the Kipchak steppes. Following this decision of the khan, Siibötäi remounted and in a fortnight, using the relays of the post, rode back to join his troops on the Caspian Sea.

The question arises as to how Jenghiz Khan conceived the idea of organizing such an ingenious institution as a regular post with relays for obtaining rapid information, for nothing similar had existed during the time of the nomadic Mongols before him. Many think that he was inspired by the Chinese example.

It is true that the Chinese did have an imperial postal organization, but its origins cannot yet be traced with certainty. It must be connected with the development of communications by roads, or water, across the immense tracts of the Chinese lands. Huang-ti, one of the “Three Emperors" who must be regarded as rather mythical creations of Chinese prehistory, is supposed not only to have started the building of temples and houses, but also to have invented many means of transport, such as carts drawn by oxen, and travel by boats on the lakes and rivers of his empire. With the growth of the empire it became evident that the administration of the west and far distant provinces was impossible without reliable communications from the central power to and from them, by official couriers. This institution must have developed early, and gradually, but the history of its origin and development has still to be written. So far only a few Chinese and Japanese authors have tried to collect information on the Chinese state post at different periods, using only part of the documentation which is preserved, according to the bibliographical sketch given by P. Olbricht (pp. 21-36).

The first literary documents concerning the existence of a kind of post can be traced only to the time of the Chou dynasty (about 1122-256 b.c.), especially in its late feudal period. One of the Chinese historians, Lao Tsui, in his work published and quoted by P. Olbricht in 1940. recorded the existence of the couriers and envoys of numerous heads of small states to their princely assemblies between 722 and 481 b.c. But we cannot yet discern in this diplomatic activity any regular establishment, although the existence of temporary relays on some roads cannot be excluded.

![]()

278

Important progress towards more regular and stable communications between the governors of the provinces and the emperor was made by the Emperor Shi Huang Ti (247-210 b.c.). After abolishing the feudal system, he divided the country into provinces, governed by officers appointed by him and directly responsible to him. He constructed roads through the whole empire, in order to impose communications between the court and the governors. He is also praised as the builder of canals for water transport and as the constructor of numerous public buildings.

During the reign of the Han dynasty (202 b.c.-a.d. 9), a regular official information service by courier was organized on certain roads of the state post. On such roads relay stations were erected at certain distances for the couriers and official travellers, with full provisions for their comfort and for the efficiency of their service. The horses for the post station were provided by the state. The relay stations were administered by local authorities responsible to a central office. A special horse tax” was imposed on the population which had also to provide the necessary personnel for the functioning of the relays.

This organization of the post degenerated during the following period and was only restored during the reign of the T’ang dynasty (618-907). During the first century of their reign the emperors established a network of post roads through their vast territory, constructing relays at easy distances with luxurious lodging houses for the users of the imperial post. Communications by rivers and canals were also included in the network. Legal injunctions were issued for the maintenance of the post roads and relays by rich and influential local families. The horses were generally supplied by the state. The poorer population living near the relays supplied the necessary personnel to maintain the buildings, to care for the horses in the pastures, and to cultivate the land allotted to the post relays. The governors of the provinces financed the expenses of running the post. Special inspectors were appointed to survey the regular operation of the post. The whole organization was placed under the supervision of the ministry of war. It was only in the middle of the eighth century that special directors for the individual relays were installed. This organization of the imperial post, carried out during the T’ang dynasty, was the basis for the further development of the institution.

The first known Arab traveller to visit China during the reign of the T’ang dynasty was the famous merchant Sulaiman. The report on his travels to India and China was written in a.d. 851 by himself, or by someone to whom Sulaiman had recounted his experiences.

![]()

279

He must have known about the Chinese postal system, although he does not mention it in his description of China. However, in his account we read an interesting detail which shows us that the Chinese took wise precautions for the security of their country and kept a close check on all travellers. He relates:

Everybody who wants to travel from one province to another has to provide himself with two letters, one by the governor, the other by the eunuch of his residence. The one by the governor is a kind of a passport for travelling. It contains the name of the traveller and of his companions, and the name of the tribe to which he belongs. Every person who wants to travel in China, be it a Chinese or an Arab, or anybody else, is bound to have with him such a document to identify himself. The document issued hy the eunuch states how much money the traveller has with him and enumerates all the objects which he carries with him. Guards are posted on all roads, to whom these documents have to be presented. After examining them, they write down “this and this person, son of . . . passed through this post.” All this is arranged for the security of the travellers.

Similar procedure was prescribed for travellers by boat. These precautions and the use of passports in China must have been a very old custom. J. T. Reinaud, in his commentary to his edition of Sulaiman’s travels (pp. 41, 118), remarks (note 90) that passports and permits to travel are mentioned in Tcheoun-li, which was issued several centuries before this era. Sulaiman might have known that similar practices had existed in Egypt, where they were maintained even after the conquest by the Arabs.

Ibn Wahab, another Arab traveller, was perhaps the first Arab to obtain the privilege of using the comfortable transportation of the Chinese imperial post. His story is recounted by Abu Zavd al-Hasan, who had lived at Siraf, which was at that time an important commercial harbor, and who had completed Sulaiman’s description with other stories which were communicated to him by other sailors and merchants who had visited China and India, or who had heard about those lands from other travellers. Ibn Wahab had established himself at Siraf after the destruction of his residence in Basra In 870. He embarked on a boat about to sail to China and reached its capital. There he was received by the emperor after the latter had verified that Ibn Wahab’s family had been related to the Prophet. Abu Zayd describes the long conversation with the emperor according to Ibn Wahab’s account. After the audience the emperor presented precious gifts to his guest and granted him the privilege of the mule transport of the royal pelt.

![]()

280

According to Abu Zayd, Ibn Wahab returned to Iraq in 915.

In another passage Abu Zayd compares the Chinese post with the Arab post. He describes the imperial post in the following terms:

“The correspondence between the emperor of China, the governors of the cities and the eunuchs is transported on the post mules. The mules have their tails cut off in the same way as the mules in our country. These mules follow routes which have been determined in advance.”

Internal troubles caused by insurrection and struggles for supreme power in the ninth and tenth centuries wreaked havoc in the Chinese post organization, and attempts at a reorganization of the service could not stop the decay of the once flourishing institution.

The Sung dynasty (960-1279) tried to reconstruct the post organization on a new basis. The service of couriers was entrusted exclusively to soldiers, who acted as runners between stations erected at shorter distances. The runners transmitted not only military orders, but all the correspondence concerning the administration of the empire. Even letters of the employees in the relays to their families were delivered by this military courier service. Horses were later used for speedier communications. In some provinces the population continued to support the old postal system for local communication. But even this imperial postal system deteriorated, especially when the Sung dynasty found it necessary to yield to the pressure of the Kin (Chin) dynasty which dominated north China, and had to limit their rule to the south only. The Kin, however, continued to use the post service as it had been established by the T’ang.

It would thus seem natural to assume that fenghiz Khan simply imitated the post service system which he had found in China after the conquest of the Kin Empire. However, he must have had some knowledge of such an information system before he invaded China. We have seen that the Chinese post organization was known to Arab merchants. We can suppose that Ibn Wahab was not the only Arab to have had a personal acquaintance with this institution. Those Arabs who came to the court of Jenghiz Khan and freely gave him information on their experiences in China and Central Asia may certainly have remembered that such an organization had existed also in the Abbasid Empire. It is interesting to note that Abu Zayd had learned that the Chinese were marking the tails of the mules used in the post service in the same way as did the Arabs. Even before invading China Jenghiz Khan must have had in mind the establishment of an information system between his armies and the homeland,

![]()

281

on the basis of what he had learned from the Arab merchants. He profited, of course, from what he had found in China. In any case, the initiative for the establishment of the Mongol state post and information service has to be ascribed to Jenghiz Khan.

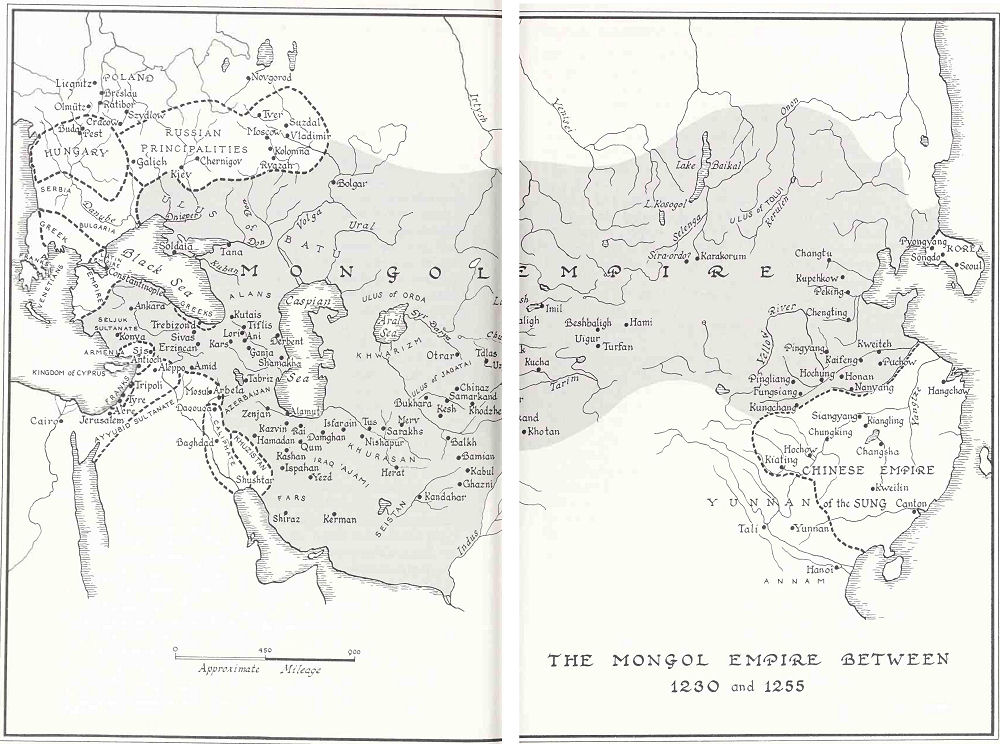

It is not our intention to describe in detail the further expansion of the Mongol Empire. A short sketch should be sufficient. Ogödäi (1229-1241) continued the conquests and devastations. Between 1230 and 1234 the Kin Empire was definitely subjected, and further wars were decided upon at the Mongol quriltai in 1233 against the Sungs in southern China, against Korea, Western Asia, and against Europe. Batu’s campaign against Europe, under the command of Sübötäi, was the most devastating. The Bulgars on the Volga were destroyed, the Cumans were defeated, and part of them fled to Hungary where they mixed with the Magyars. From the Volga the Mongols invaded Russia, and subjected and destroyed its principalities during a winter campaign. In 1240 Kiev was conquered and devastated and its population massacred. In 1241 the hordes invaded Poland, Germany, and Hungary, alter defeating the Poles at Lignitz. The Hungarian King Bela 11 escaped, but was pursued as far as the Adriatic coast. Only the arrival of a messenger on the state post announcing the death of Ogödäi saved the rest of Europe from a similar fate. Batu had to return to be present at the quriltai which was to elect Ogödäi’s successor. On his way back he subjugated Bulgaria, Wallachia, and Moldavia (modern Rumania). He subsequently settled on the lower Volga, where a Mongol state was organized under the name of Golden Horde after the magnificent tent with a golden roof erected by Batu. It ruled over the whole of Russia to the Crimea, with its capital at Sarai. Its khans recognized the supremacy of the Great Khan but were almost independent. The new empire was also called Western Kipchak, because it ruled over the territory of subjected Cumans.

Ogödäi was succeeded by his son Kuyuk, who reigned only seven years. After his death dissensions between the houses of Ogödäi and Jagatai broke into open war, which ended in 1251 when Mongka, the eldest son of Tolui and nephew of Ogödäi, was elected khan. To quell disturbances in the province of Persia, Mongka sent his brother Hulägu with an army with the order to destroy the sect of the Assassins, who were regarded as the cause of the disorders. After securing the dismantling of fifty main fortresses of the sect, Hulägu’s army attacked the Assassins, and all of them, men and women, were mercilessly slaughtered. Hulägu thus crossed the mountains and arrived before Baghdad.

![]()

282-283

The Mongol Empire between 1230 and 1255

![]()

284

As the Caliph Mustasim had refused to surrender, the Mongols breached the walls, sacked the city, and executed the last Caliph of Baghdad. Hulägu continued the devastation of the former provinces of the caliph. Only in 1260 was the thrust of the Mongols in Africa stopped, when their army was defeated by the Mamluk Sultan Baybars, the ruler of Egypt.

Hulägu, hitherto a vassal of Mongka, was recognized as ruler of the conquered provinces. He assumed the title of Ilkhan and, although recognizing the khan as his sovereign, was practically independent.

At the same time, while Hulägu was conquering Asia, Mongka and his other brother, Kublai, were invading southern China. They advanced into Tonkin and even invaded Tibet. Kublai, educated by a Chinese wise man, forbade the destruction of cities and the massacre of conquered peoples. During this expedition Mongka died of dysentery.

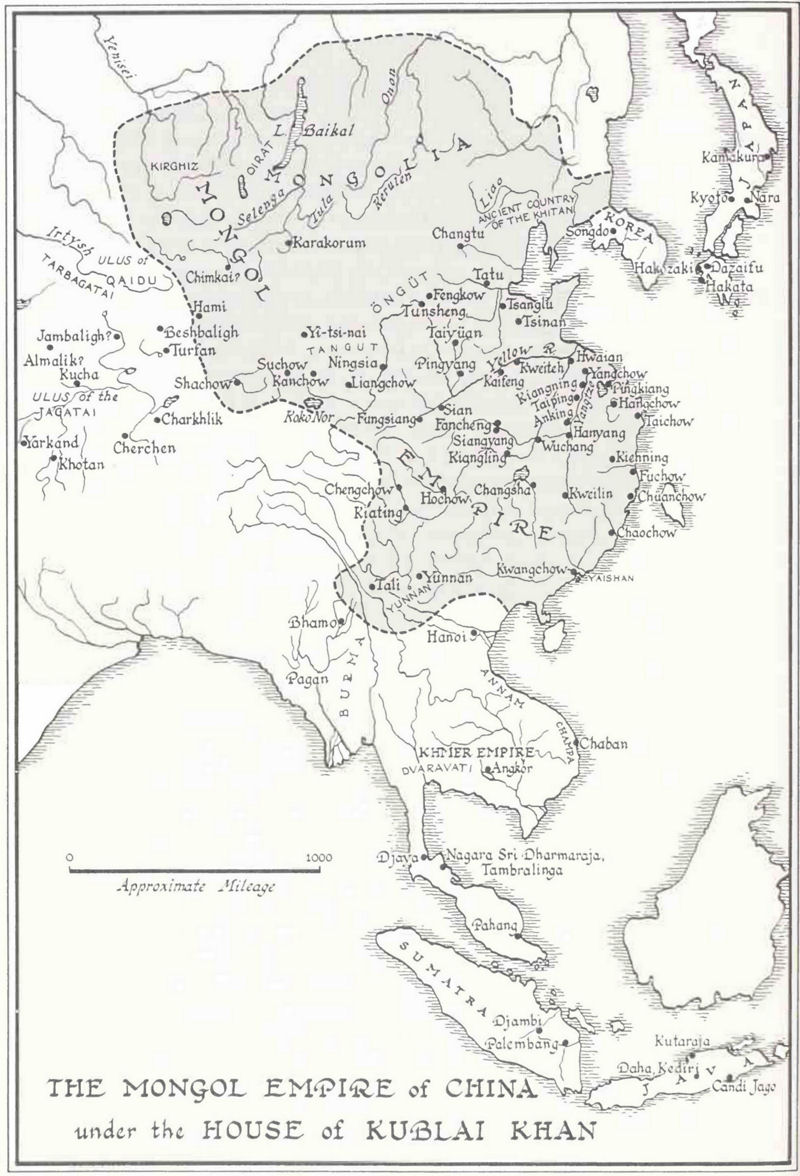

A new quriltai was assembled in great haste by the Mongolian chieftains, who distrusted Kublai; they elected Mongka’s youngest brother, Ariq-bögä, viceroy in Karakorum. Kublai reacted promptly. He had himself proclaimed khan by his army and the Mongolian viceroy of the Chinese provinces, and, to strengthen his position, had himself crowned as Son of Heaven by the Chinese princes, generals, and mandarins. He defeated the army of Ariq-bögä and also that of Qaidu, Ogödäi s grandson. Then he continued his great struggle against the Sung Empire. The Empress Mother, regent for the child-emperor, surrendered her capital, the famous Hangchow. The last resistance of some cabinet ministers, who had fled southeastward and had proclaimed the elder brother of the captured emperor as their ruler, was broken by Kublai’s able general, Bayan. The defeat of the rebels’ fleet, which, in desperation, had drowned their emperor, put a definite end to the Sung Empire in 1279. The whole of China was united under one foreign ruler and was to remain united down to modern times.

The Mongol Empire, united with China, was manifesting a more stable and firm state organization. The Chinese Yuan dynasty, as distinguished from the Mongol Empire, was effectively founded by Kublai, although he only adopted the dynastic title in 1271. He ruled over China according to Chinese precedents and was called by the Chinese Shih-tsu. He transferred the winter capital to Yenching in 1260, where he constructed Khanbaligh or Tatu (Peking) in 1267.

Jenghiz Khan s successors continued to take good care of the state post, which was the means of their most reliable intelligence service.

![]()

285

Soon after his accession, Jenghiz’s successor Ogödäi issued two decrees, in 1229 and in 1232, concerning the service of couriers. After his victory over the Kin dynasty in 1234. he solemnly announced at the quriltai the main statutes of the postal service. Speaking of his exploits and confessing his mistakes — especially in too often becoming drunk, according to the report contained in the Secret History of the Mongols — Ogödäi declared that, besides the destruction of the Kin dynasty, the greatest of his achievements was the erection of new postal roads with jami throughout the whole empire, which shows how highly the Mongols appreciated this service. This reorganization seemed to be necessary following the extension of Mongol sovereignty over the whole of northern China. The new residence of Batu at Sarai on the Volga had also to be connected with the rest of the empire. Ogödäi seems to have appointed a special postmaster (Amir) to maintain the link with the khan of the princes of the dynasty. Ogödäi ordered two faithful followers of Jenghiz Khan — Aracin and Togusar — to survey the reorganization of the post, decided at this important quriltai. The report of the Secret History of the Mongols is also confirmed by the Persian historian Rashid al-Din. Ogödäi thus completed at this meeting the organization of the post, which he had initiated by his previous decrees mentioned above. Mongka paid special attention to the proper functioning of the post. He ordered that all revenues from the provinces should be used to pay the cost of the local armies and for the promotion and improvement of postal communications. As we will see, it was Kublai who brought the post organization to such perfection that its formation and functioning astonished his contemporaries, and is still recognized as an outstanding achievement by historians.

As we have seen, there are not many Mongolian documents which illustrate the origin and functioning of the post and its importance in the administration of the state during the purely Mongolian period of the empire. Fortunately, we are in possession of some Western sources which fill this gap and help us to see how this organization worked. These sources are the accounts of western envovs who had travelled to the courts of the khans and who often left us picturesque descriptions of their experiences.

The appearance of the Mongols in the heart of Europe awakened the west to the horrible danger which threatened them from the Far East, where mighty khans were governing most of Asia and a great part of eastern Europe. The immediate threat was averted by the death of the Great Khan Ogödäi, but Batu remained encamped on the Volga, and a new onslaught on the rest: of Europe by the Mongols was possible following the election of a new khan and the reorganization of the Mongol Empire.

![]()

286

Western Europe was divided and split by the war raging between the Emperor Frederick II and the Pope. It was high time to obtain further knowledge of the Mongol rulers and their plans, and to approach the new khan in order to avert a new campaign against the west.

Pope Innocent IV, aware of this, sent a mission to the Mongols. Two Franciscans were chosen for this dangerous undertaking — Lawrence of Portugal and Giovanni de Piano Carpini; the latter described the journey in a long report. They were the first Westerners to undergo the watchfulness of the Mongol border guards. After traversing Galicia and Kiev, they were stopped in the Russian steppes by the Mongol advance guard and arrested. But because they claimed to be envoys of the Pope bearing a message to the khan, the Mongols, respecting the law stressed by Jenghiz in his Yasaq commanding respect for envoys, conducted them first to their commander Carenza. The latter gave them an escort which accompanied them to the residence of Batu on the lower Volga. Batu decided that they should go to the court of the new Khan Güyük in Mongolia, and Tatar guides accompanied them. They travelled rapidly, as Batu wished them to reach Karakorum to be present at the solemn inauguration of the new khan. It is evident from their description that they were led along the postal road, probably on the new branch erected by Ogödäi to link up Batu’s residence with Karakorum. Riding hard, they had fresh horses five or seven times a day, provided by the jami. From the lands of the Cumans, conquered and occupied by the Mongols, they reached that of the Kang-li Turcs, whence they entered the land of the former Khwarizmian Empire. Then they traversed the former Kingdom of Kara-Khitai, the country of the Naimans, and reached the camp of Orda, Batu's brother. From the city of Divult (Imil) they had again to ride hard for three weeks, arriving at the orda of Güyük on July 22. It was a remarkable achievement, and a very hard experience for the friars, possible only because of a generous supply of relay horses by the jami.

Carpini does not describe the Mongol post in detail, but he knew how it functioned. In one passage of his report he says,

“Whatever envoys the khan dispatches, to whatever place and wherever it may be, they are bound to give them without delay packhorses and provisions. Also from whatever quarter envoys come to him bearing tribute, they have likewise to be provided with horses, carts, and supplies. This post service is, however, only for official messengers, envoys, and embassies.”

![]()

287

The friars do not describe the return journey in detail, mentioning only that they travelled over open steppes for six months during the winter, suffering incredible hardship. Leaving Karakorum on November 17, 1246 they reached Batu’s ordo on May 9, 1247. They must have followed the same road through Asia, and it is rather surprising that they had often to sleep in the snow, or on the open plain, scraping out a place to sleep with their feet, as Carpini describes it. After a stay of a month at Batu's orda they were given a letter of safe conduct; after a journey of fifteen days, led by Mongol guides, they reached Kiev.

Giovanni de Piano Carpini’s mission was, of course, unsuccessful. In his missive to the Pope, the khan confessed that he did not understand why he and his people should become Christians. If the Pope wished to be at peace with the Mongols, then he and his Christian princes should submit to the khan in Karakorum and bring tribute.

The Pope’s envoys received the impression that the Mongols were preparing for a new invasion of Europe, and they refused to take any Mongolian envoys with them for fear that their role would be to gather intelligence about the West to help them in their campaign. The Pope decided to send a further embassy composed of five Dominican friars. They were to visit the nearest camp of the Mongolian army on the frontier of Asia Minor and present to its commander the Pope’s letter in which he requested the cessation of hostilities against the Christians. The friar Ascelin, leader of the embassy, got to the camp of Baiju in May 1247. He and his friars were threatened with execution for refusing to perform the usual act of homage, but they were saved by the timely arrival of a senior official and envoy of the Great Khan Eljigidäi, who was of the opinion that it might prove useful to enter into relations with the West. Ascelin was sent back with a letter containing the same invitation to submission. He was accompanied by two Mongol envoys, one of them a Christian. They were received by the Pope in 1248. At the same time, Eljigidäi himself sent two envoys — both Nestorian Christians—to the French King St. Louis to establish good relations with him, as the king was preparing a crusade against Egypt. His envoys met King Louis in Cyprus; in the letter they delivered to him, Eljigidäi declared that the Great Khan intended to protect the Christians and help them in the recovery of Jerusalem. Encouraged by such a message, Louis sent an embassy to the khan, composed of three Dominicans, whose leader was Andrew of Longjumeau who spoke Persian.

![]()

288

Among the rich presents which the ambassadors were given to present to the khan was a beautiful tent chapel in which all the mysteries of the Christian faith were depicted.

Unfortunately, by the time they arrived, the khan was already dead, and the envoys were presented to the Regent Oghul Qaimlsh, Güyük’s widow, at her court on the southeast of Lake Balkash. Their arrival was interpreted as an act of homage and submission, and their presents accepted as tribute, for the letter sent by the regent to the king contained the same demand for submission, with the threat of punishment should the king refuse.

The reports that there were many Christians living in the empire of the Mongols, as well as the rumor that even Sartaq, the son of Batu, had been converted, encouraged the King of France to send another mission of a decidedly more religious character to Sartaq and Batu in 1253. The envoys were two Franciscan friars, William of Rubruck and Bartholomew of Cremona, with a clerk and an Arab interpreter. Although a religious mission, the envoys also carried a letter to the Great Khan. They travelled by the old highway to Central Asia, through Constantinople and the Crimea. They reached Soldaia (Sudak) in May where they equipped themselves with carts and horses, and three days afterwards they reached the first Mongol frontier station. They were subjected to a strict investigation as to the purpose of their journey and the contents of their carts. Thanks to letters of recommendation given them by the Latin Emperor of Constantinople Baldwin II to a Captain Scatatai, a relative of Batu, they were permitted to continue their journey to the orda of Sartaq. On July 22, 1253, they reached the river Don and were taken across by villagers who were charged by Sartaq and Batu with such duties. This seems to be the first indication that the Mongols of the Golden Horde had made any arrangements to facilitate the travel of envoys and merchants to the ordas of their khans. No special provision seems to have existed for the stretch from the frontier station to this village, as one can conclude from the narrative of Rubruck. The regular state post station was at a distance of four days' journey from the Don. Then Rubruck says with satisfaction, “we got horses and oxen and went from station to station until arriving at Sartaq’s camp on July 31. They left their carts at the jam near the camp and rode to the orda of Batu, escaping bands of refugees who endangered their progress.

When they reached the Volga they were brought across the river in boats manned by the inhabitants of a village founded by Batu. This arrangement was similar to that described on the river Don.

![]()

289

Batu sent Rubruck to the Khan Mongka (1251-1259), son of Tolui, who had been elected khan instead of Giiyiik’s widow’s son. It appears that Rubruck, who also acted as Batu’s envoy to Mongka, and was provided with a guide by him, followed the same post road as Carpini and, with his companions, was provided with horses at the jami. The service was not always good, as they were strangers and the best horses were given to official messengers. Rubruck always had to be given the strongest horse because he was very fat and heavy. However, the friar complains that his horse did not always behave as it should and as he expected. He does not spare bitter words in describing the journey. They were also provided with food, but in the Mongol manner, which the friar did not like: some millet in the morning and a main meal with meat in the evening. Their guide was everywhere greeted with great respect as Batu’s envoy to the khan. They passed the Kirghiz Steppe and reached the city of Cailac, where they awaited instructions which Batu’s scribe was to deliver to their guide. The post road went through mountainous regions, and the only inhabitants they met were the men in charge of the jami. They often made two days’ journey in one. After passing through Dzungaria, the former country of the Kaimans, they reached the orda of the Great Khan. The officer in charge of the last jam wished to keep them on their journey for a fortnight in order to show them the immensity of the khan’s lands, but their guide prevented such a circuitous route, and they were allowed to continue on the direct route.

The return journey from Mongka’s orda to that of Batu lasted two months and ten days. They travelled through different regions but came across the same people. During the summer the roads went through far more northerly districts than when they had journeyed during the winter. Even this summer route was provided with jami, for Rubruck says that they did not rest during the whole journey except for one single day when they could not obtain horses. A military escort was given to him by Batu on the way to and through Derbent, because the Alans and the Lesgians in the Caucasus were still putting up resistance to the Mongols. Travelling through Georgia, Armenia. Persia, and Seljuk Asia Minor, Rubruck reached Tripoli in Syria.

When we compare the descriptions of the journeys of de Piano Carpini and Rubruck, we have the impression that there had been an improvement made in the organization of the post service in the years between 1245 and 1253. Rubruck, of course, complains of many things — the service given by the employees of the jami, about the horses, and about the food — but he seems to have travelled more comfortably than Carpini.

![]()

290

His complaints are probably exaggerated, because he hated the Mongols.

This improvement should be ascribed to the efforts of the Khans Tu'iyiik and Mongka, both of whom were anxious to make the post and messenger service speedier and more comfortable. But it was the Great Khan Kublai who brought this organization almost to perfection. We have a very eloquent description of the post and messenger service as it worked during the reign of Kublai, written by Marco Polo, a Venetian by birth who accompanied his father and uncle on their second journey to China. On reaching the Persian Gulf, they set out overland for China, arriving about May 1275. They were shown into the presence of Kublai, who was at his summer residence at Chan du. They left China in 1291, reaching Venice in 1295, after a twenty-five year absence. They certainly knew the Mongol-Chinese post service well, because they had the opportunity of using it. When the brothers, at the end of their first stay in China, were sent by Kublai to the Pope with the message that the khan needed about one hundred learned religious men well versed in all the sciences for the instruction of his people, the khan handed them the Golden Tablet which entitled them to use the official post service, “that wherever they went, they were to be furnished with all the necessary quarters, and with horses and men to escort them from one town to another.”

Marco Polo describes first the numerous postal roads leading from the residence of the khan to all the provinces and bearing the names of the provinces. At a distance of twenty-five miles from each other, he says, are stages called jami, which means horse-post station. When describing the stations Marco seems to exaggerate a little. He describes them as “large and fine palaces where ihe envoys lodge, with splendid beds furnished with rich silk sheets, and with everything else that an important envoy may need.” Such luxurious buildings might have existed at certain distances for “important envoys,” but hardly for simple messengers. Each station had three or four hundred horses. The distances between the stations in mountainous regions are, according to his description, greater, being thirty-five and even more than forty miles. But they are equipped as well as other stations, with the horses, officers, and staff needed for the service. They formed large villages. There are more than ten thousand such stations — Marco Polo calls them palaces — and more than 200,000 horses are kept there.

According to Marco Polo, the horses were supplied by the cities and villages near the stations.

![]()

291

The number of animals “to be provided by the cities is determined after inquiries made by men experienced in this matter. The cities kept the horses as well as the tribute owed to the khan. Generally only about two hundred horses are available at the stations, the other two hundred being out to pasture; they are changed every month. If the messenger must cross a lake, the neighboring cities must have in readiness three or four boats capable of making a speedy crossing. If he must cross a desert, taking several days, the city nearest the desert must supply him with horses and food and must escort him to the other side. The khan supplied horses only to those stations in uninhabited regions.

In this way, the messenger on horseback, when in great haste and bearing important intelligence, can cover 200 to 250 miles a day. He swathes his belly, binds his head, and must bear the tablet with the ensign of the gerfalcon to show that he must travel with the utmost speed. When approaching a station he sounds a kind of horn that can be heard a long way off, and on hearing the horn the staff of the jami saddle a swift horse in readiness. The messenger changes his mount and without resting sets off again at full speed to the next station, where the same procedure is followed. When riding through the night and if there is no moon, the men of the station must precede him with lights to his next stop. In this case, of course, his speed is reduced.

We learn from Marco Polo that, besides the horse-post, Kublai had introduced an information service by runners:

Every three miles between the stations, there is a small village where live toot-runners whose duty it is to carry messages to the khan. They wear a broad belt hung all around with bells so that they may be observed from far away. They always run at full speed for the three miles to the other runner stations. Another runner is waiting, takes from his colleague what he is carrying, receives a slip of paper from the clerk, and runs to the next station. In this way the khan receives news in a day and a night from places at a distance of ten days’ journey.

The runners sometimes have to deliver to the khan fresh fruit or vegetables from ten days’ distance away. At each runner-station a clerk is appointed who has to register the day and hour of the arri val of the messenger and of his departure to the next station. The runners are freed from taxation and paid by the khan. Special inspectors have to visit the stations every month to investigate how the runners perform their duties.

![]()

292

The Mongol Empire of China under the House of Kublai Khan

![]()

293

Marco Polo himself was often sent as khan’s messenger, or envoy, to different provinces and lands. When describing how he had performed his duty as envoy to a certain province. Marco Polo discloses that the khan’s messengers had another duty besides carrying the message. They were supposed to act also as spies and undercover agents to bring intelligence about the behavior of the inhabitants of the provinces through which they were travelling. If they reported that they had only delivered the message, the khan called them fools and ignorant men. He expected to hear from them all the news they had learned on their mission, together with information on the habits and customs of countries through which they had travelled. Marco Polo confesses that he knew about this and, when sent on a mission, he paid attention to all novelties, rumors, and strange things he might hear or observe, and the khan greatly appreciated his reports.

The first traveller to describe the lands of the Far East after Marco Polo was the Franciscan Friar Odoric. He was sent to the east about the year 1318 as a missionary. He stayed first for some time about 1321 in western India, and went from there to China overland, and reached Peking by way of the Great Canal. He stayed in China for three years. He returned overland across Asia, and died in 1331 at Udine in Italy. Because of his holy life he was beatified by the Pope.

In chapter 40 of Yule’s edition of his travels, Odoric describes the Mongolian state post in China:

And that travellers may have their needs provided for, throughout his whole empire he [the khan] hath caused houses and courts to be established as hostelries, and these houses are called jami. In these houses is found everything necessary for subsistence, and for every person who travels throughout those territories, whatever be his conditions, it is ordained that he shall have two meals without payment. And when any matter of news arises in the empire, messengers start incontinently at a great pace on horseback for the court: but if the matter be very serious and urgent they set up upon dromedaries. And when they come near these jami hostels or stations, they blow a horn, whereupon mine host of the hostel straightway maketh another messenger get ready; and to him the rider who hath come posting up delivereth the letter, whilst he himself tarrieth for refreshment. And the other taking the letter, maketh haste to the next jam, and there doth as did the first. And in this manner the emperor receiveth in the course of one natural day the news of matters from a distance of thirty days’ journey.

But the despatch of foot runners is otherwise ordered. For certain appointed runners abide continually in certain station-houses called chiclebes, and these have a girdle with a number of bells attached to it.

![]()

294

Now those stations are distant the one from the other perhaps three miles; and when a runner approaches one of those houses he causes those bells of his to jingle very loudly; on which the other runner in waiting at the station getteth ready in haste, and taking the hotter hastens to another station as fast as he can. And so it goes from runner to runner until it reaches the Great Khan himself. And so nothing can happen in short, throughout the whole empire, but he hath instantly, or at least very speedily, full intelligence thereof.

When commenting on Odoric s description of the Chinese post Yule quotes a passage from the report given to the Shah Rukh by his ambassadors who had visited the Chinese court about a century after Odoric. Their report confirms Odoric’s description, adding something which the friar may have overlooked. They say that between the jami many towers were located which they called kargüs. Two men were on duty at each tower and were relieved every tenth day. Their duty was to pass light signals from one tower to another in the case of urgent emergency, especially when an enemy army was approaching. “And so the signal passes from one to another till in the space of one day and night a piece of news passes over a distance of three months’ march.”

These pieces of information on the Mongol-Chinese post given by Western travellers are, in some way, expanded by the famous Arab traveller Ibn Batuta. He was born in Tangier in 1304, and spent most of his life travelling in Muslim countries, India, China, Russia, and Byzantium. The Indian Sultan Muhammad sent him as ambassador to the Chinese court in 1342, but, because of unforeseen difficulties, he only reached China in about 1347. His stay there seems to have been short, but his report gives a few details which complete our knowledge about the Chinese intelligence service during the Mongolian period and about the further development of post stations as hostels for travellers.

Particular importance attaches to what he says about the control of visiting foreigners in China. According to the translation given by Yule (II, 483 ff.) Batuta says,

“It is an established custom among the Chinese to take the portrait of any stranger that visits their country. Indeed the thing is carried so far that, if by chance a foreigner commits any action that obliges him to fly from China, they send his portrait into the outlying provinces to assist the search for him, and wherever the original of the portrait is discovered they apprehend him."

This custom must have been especially observed when envoys and their foreigners were admitted to an imperial audience.

![]()

295

Batuta himself discloses his surprise at having seen his own and his companions' portraits exhibited in the bazaar after his return from an imperial audience.

Strict provisions were made by the imperial police in the ports, as described by Batuta:

Whenever a Chinese junk is about to undertake a voyage, it is the custom for the admiral of the port and his secretaries to go on board, and to take note of the number of soldiers, servants, and sailors who are embarked. The ship is not allowed to sail till this form has been complied with. And when the junk returns to China the same officials again visit her. and compare the persons found on board with the numbers entered in the register. If anyone is missing the captain is responsible, and must furnish evidence of the death or desertion of the missing individual, or otherwise account for him. If he cannot, he is arrested and punished.

The captain is then obliged to give a detailed report of all the items of the junk’s cargo, be their value great or small. Everybody then goes ashore, and the custom-house officers commence an inspection of what everybody has. If they find anything that has been kept back from their knowledge, the junk and all its cargo is forfeited. This is a kind of oppression that I have seen in no country, infidel or Muslim, except in China.

To the post service Batuta devotes only a short but interesting chapter:

China is the safest as well as the pleasantest of all the regions on the earth for a traveller. You may travel the whole nine months’ journey to which the empire extends without the slightest cause for fear, even if you have treasure in your charge. For at every halting place there is a hostelry, superintended by an officer who is posted there with a detachment of horse and foot. Every evening after sunset, or rather after nightfall, this officer visits the inn accompanied by his clerk: he takes down the name of every stranger who is going to pass the night there, seals the list, and then closes the inn door upon them. In the morning he comes again with his clerk, calls everybody by name, and marks them off one by one. He then dispatches along with the travellers a person whose duty is to escort them to the next station, and to bring back from the officer in charge there a written acknowledgment of the arrival of all; otherwise this person is held answerable. This is the practice at all the stations in China from Sin-ul-Sin to Khanbalik [Tatu]. In the inn the traveller finds all needed supplies, especially fowls and geese. But mutton is rare.

This seems to denote a further development of the postal service for the profit of private travellers.

![]()

296

The stations (jami) were for the officers and messengers who were bound also to supervise private traffic, and the inns erected near the jami for the comfort of the travellers. We have noticed a similar development in the history of the post in the Mamluk Empire.

Of course, the sources quoted above do not give details as to the organization and functions of the post. Fortunately, P. Olbricht, in his Postwesen in China, completed this information from Mongol and Chinese documents which are rarely accessible to western scholars. He gives a detailed survey not only of documents preserved in the Chinese archives, but also of Chinese and Japanese literature on the subject. He studies in detail the organization of the post as it developed on the basis of Kublai’s legislation and rescripts. We shall limit ourselves only to a short sketch of the most important features of the Mongol and Chinese post administration during the reign of Kublai.

It would appear that even in the post organization of the state. Chinese traditions prevailed, but the many Mongol titles in the administration show us that Mongol practice and tradition continued to exist, though mixed with Chinese customs.

It should be noted especially that the Mongol custom of entrusting high positions in the state organization to persons without mentioning the office they had to occupy, had survived down to the reign of Kublai. The imperial decree of 1264 refers only to the name of the man who was in charge of the Chinese post — Qomugui — without giving him a title. We also learn from this decree that the dignitary mentioned was in charge only of the post organization on Chinese territory. The old Mongolian post organization formed a separate entity, but we do not know the name of the man who was in charge of it. An attempt at a centralization of this organization was made in 1270, when a general commissariat for the administration of all posts was erected with three general commissars. The commissariat was under the direction of the war ministry, which existed from 1260. This ministry was the executive organ of the central bureau (chung-shu-sheng) where all administrative direction was concentrated.

The commissariat was transformed into an autonomous organ, called office of the couriers, in 1276. The war ministry, which had two separate files from 1270 on, one for the care of the post stations and the other for provision of horses needed in their service, continued to be an important mediator between the central bureau and the office of the couriers. In order to improve the courier service between the summer residence at Chandu and the winter residence at Tatu,

![]()

297

two special offices of the couriers had to be established in the two Mongolian capitals in 1279. The reorganization of the post service in conquered southern China was entrusted to four officers of the bureau of couriers, but these offices were abolished when the southern Chinese had become familiar with the Mongol breeding and care of horses.

Complaints about mismanagement of the post traffic induced the Emperor Yen-tsung to suppress the office of the couriers and to submit the whole post organization to the ministry of war in 1311.

However, in 1320, the competence of the office of the couriers was re-established and extended over the Mongolian and Chinese posts. From that date on until the extinction of the dynasty the office of the couriers was the only government authority for the imperial post. The regional administration of the different post stations and their staff was in the hands of officers presiding in the governmental districts or provinces. Difficulties which resulted from the unwillingness of rich families to provide the stations with necessary means and horses were the subject of many complaints directed to the office of the couriers or to the war ministry, and were objects of many imperial laws and decrees. These documents also regulated the positions and duties of the postmasters of different stations and of their staff, among which the administrator of the post warehouse occupied a very important place. Even before the conquest of China the Mongols had special controllers whose duty it was to inspect the different stations and control the activity of the postmasters and their staffs. This seems to have been a Mongol “invention” about which the Chinese did not originally know. The controllers resided in the capitals of the government districts and held much higher rank than the postmasters. They had to oversee the authenticity of the permits to use the post presented to the couriers, inspect the performance of their duties, watch over the use of the horses, see that the couriers and other users of the post did not transgress the permitted load of packages for their personal use, inspect the jami and the number of horses they must have ready, and prevent misuse of any kind. The controller himself, of course, used the state post, but had first to ask for a pass from the director of the governmental district. In spite of all these precautions misuse of the post could not be completely eliminated, but it has to be acknowledged that the Mongol-Chinese state post functioned well. The Mongols naturally profited by the experiences which the Persians had with their own institutions, and they accepted many Chinese customs in the organization of their state post, but only the Mongols with their strong measures and talent tor organization could have brought such an immense and complicated institution to such a state of perfection.

![]()

298

The fact that, alter the fall of the Mongol Empire and their expulsion from China, the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) continued to use it with great profit, only emphasizes the perfection of this Mongol institution.

CHAPTER V: BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abel-Rémusat, M., Nouveaux mélanges asiatiques (Paris. 1929), 2 vols. (Marco Polo, v. I, pp. 381-415; Sübötäi, v. II, pp. 89-99).

Berthold, W., Turkestan down to the Mongol Invasion, 2nd ed. (London 1958).

Boyle, J. A., Jnvaini, ’Ala UD-DIN ’Ata Malik (1226-1283). The History of the World Conqueror, transl. by J. A. Boyle (Manchester, 1958).

Contarini, Ambrogio, Travels to Tana and Persia by Josafa Barbaro and Ambrogio Contarini, transl. by Wm. Thomas and S. A. Roy, The Hakluyt Society Works, First Series, vol. 49 (1873).

Dawson, C., The Mongol Mission. Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the 13th and 14th Centuries (New York, 1955).

Dörrie, H., Drei Texte zur Geschichte der Ungarn und Mongolen: Die Missionsreisen des fr. Julianus, O.P. ins Uralgebiet 11234/20) und nach Russland (1237) und der Bericht des Erzbisshofs Peter über die Tataren (during the Council of Lyon, 1245),” Nachrichten of the Academy, Göttingen (1956).

Ferrand, G., Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine rédigé en 851 suivi de remarques par Abu Zava Hasan (vers 9161 (Paris 1922.

Gibb, H. A. R., The Travels of Ibn Batuta (1325-1354), 2 vols., Hakluyt Society Works (Cambridge, 1962).

Giovanni de Piano Carpini, Histoire de Mongols, transl. with notes by J. Becquet and L. Hambis (Paris. 1965).

Creat Yasaq, see G. Vernadsky.

Grousset, R., Conqueror of the World, transl. from the French by Denis Sinor and Marian MacKeller (Edinburgh, London, 1967).

_____, L’Empire des Steppes (Paris, 1939); The Empire of the Steppes, transl. by N. Walford (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1970).

_____, L’Empire mongol (Ire phase) (Paris, 1941).

Haenisch, E., Die Geheime Geschichte der Mongolen (Leipzig, 1948).

_____, "Kulturbilder aus Chinas Mongolenzeit.” Historische Zeitschrift, 164 (1941), pp. 21-48, Post, 37 ff.

Hartmann, R., “Zur Geschichte der Mamelukenpost,” Oriental. Literaturzeitung, 46 (1943), pp. 265-269 (review of Sauvaget’s work).

![]()

299

Ihn Batuta. Travels, see H. A. R. Gibt.

Komroff, M., Contemporaries of Marco Polo (W. Rubruck; John of Pian do Carpin: Friar Ođoric; Rahbi Benjamin of Tudela) (New York. 1928).

Latourette, K. S., The Chinese, Their History and Culture, 2nd ed. (New York. 1943); selected bibliography for each dynasty.

Marco Polo, The Description of the World, ed. and transl. by A. C. Monie and P. Pelliot (London, 1938), 2 vols.

Maspero, H., La Chine antique (Paris, 1927), Histoire du monde, vol. 4.

Odoric, Friar, see H. Yule and M. Komroff.

Olbricht, P., Dus Postivesen in China unter der Mongolenherrschaft im 13. und 14. Jahrhundert, Göttinger asiatische Forschungen, vol. 1 (Wiesbaden, 1954).

Olschki, L., Marco Polo’s Precursors (Baltimore, 1943).

Otte, Fr., “Die chinesische Reichspost," Sinica, 15 (1940), pp. 274-305, modern times.

Pelliot, P., Histoire secrète des Mongols (Paris, 1959).

_____, “Les Mongols et la Papauté,” Revue de l'Orient chrétien, 3e S. t. III (XXIII) (1922-1923), pp. 3-31; t. IV (XXIV) (1929), pp. 225-330.

_____, Notes on Marco Polo, ed. L. Hambis, 2 vols. (Paris, 1959-03).

_____, Notes sur l'histoire de la Horde d’Or (Paris, 1953).

_____, Shêng ivu ch'in chêng lu. Histoire des campagnes de Gengis Khan, transl. by P. Pelliot and L. Hambis (Leiden. 1951).

Poucha, P., Die geheime Geschichte der Mongolen, Archiv Orientalin, Supplémenta 4 (Prague, 1950).

Prawdin. M., The Mongol Empire, Its Rise and Legacy, transl. by Eden and Cedar Paul (London. 1940).

Reinaud, J. T., Hasan ihn Yazid, Abu Zaid. aI-Sirqfi. Relation des voyages faits par les Arabes et les Persans dans l’Inde et à la Chine dans le 1XV siècle de Père chrétienne (Paris, 1845).

Ricardus, Relatio Fratri s Ricardi (about 1235-6), Scriptores Rerum Hungaricarum, II, pp. 538-42 (Budapest, 1938).

Rubruck, William of, Itinerarium, see A. van den Wyngaert, pp. 147-332.

Secret History of the Mongols, see P. Pelliot and P. Poucha.

Spuler, B.. Die Mongolen in Iran (Berlin, 1955), pp. 422-430.

Sulaiman, see J. T. Reinaud and G. Ferrand.

Vernadsky. G., “The Scope and Contents of Chingis Khan’s Yasa,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 3 (1938), pp. 337-300.

_____, The Mongols and Russia (New Haven, 1953).

Wyngaert, Anastas van den, Jean de Mont Corvin, O.F.M., premier évêque de Khanbaliq (Pe-king, 1247-1328) (Lille, 1924).

_____, Sinica Franciscana, l. Itinera et relationes Fratrum Minorum Saeculi XIII et XIV (Quarrachi-Firenze, 1929), pp. 147-332.

Yule, H., Cathay and the Way thither; being a Collection of Mediaeval Notices of China (London. 1800).