IV. Intelligence in the Arab Muslim Empires

1. The Patriarchal Period and the Omayyad Empire

Rise of Muhammad — The First Caliphs-Persian and Byzantine Traditions in the Administration — Efforts to Replace Byzantium-Reintroduction of Intelligence Service by State Post — Use of Secret Police — Nationalization of the Administration, Further Conquests, and Fall of the Dynasty.

Equality of Muslim Races, Awakening of National Sentiments, Golden Age of Arabic Literature — Last Attempt to Conquer Byzantium — Reorganization of the Post by Harun Al-Rashid, According to Main Sources — Six Main Postal Roads — Organization of the Barid (Post), According to Kudama — Postmasters in the Espionage System-Arabic Police-Post by Carrier Pigeons-Disintegration of the Caliphate-Intelligence Service and Propaganda by the Fatimids — Intelligence Service during the Seljuk’s Protectorate.

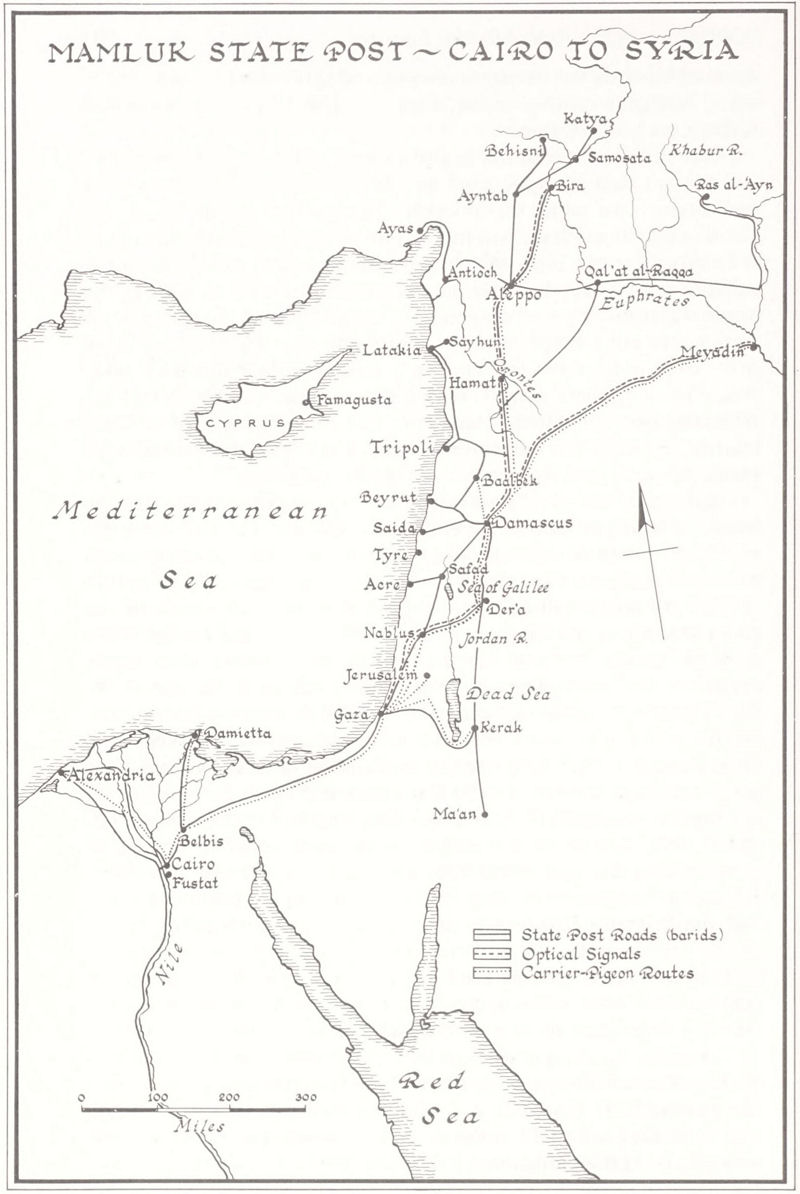

3. Intelligence in the Mamluk Empire

Baybars Becomes Sultan-Al-Omari’s History of Arab Post in His Al-Tarif-Al-Makrizi’s Description of Bavbars’s State Post — Postal Roads Described in Al-Tarif — Baybars’s Post by Carrier Pigeons-Al-Malik-al-Nazir’s Reforms-Transport of Snow by State Post-Decadence of the State Post Service and of the Mamluk Empire.

4. Arab Intelligence on Byzantium

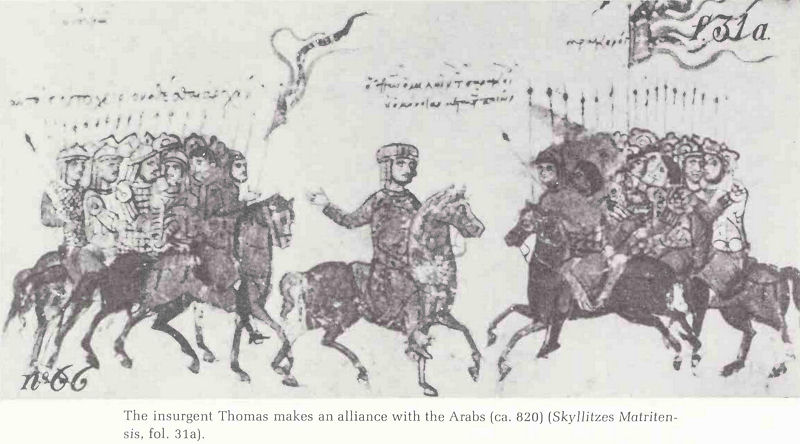

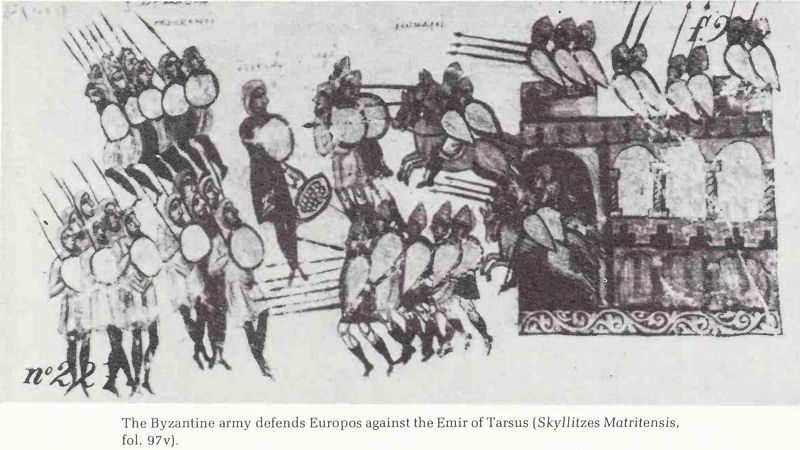

Christian Spies in Arabic Service — Byzantine Deserters, Arabic Security Measures on the Frontier — The Strategus Manuel — Al-Mas’udi on Exchange of Prisoners — Al-Mas’udi’s Story on Muawiya’s Revenge of Mistreatment of an Arab Prisoner — Arab Prisoners in Constantinople, and Their Information — Embassies — Arabian Geographers on Byzantium.

188

![]()

![]()

189

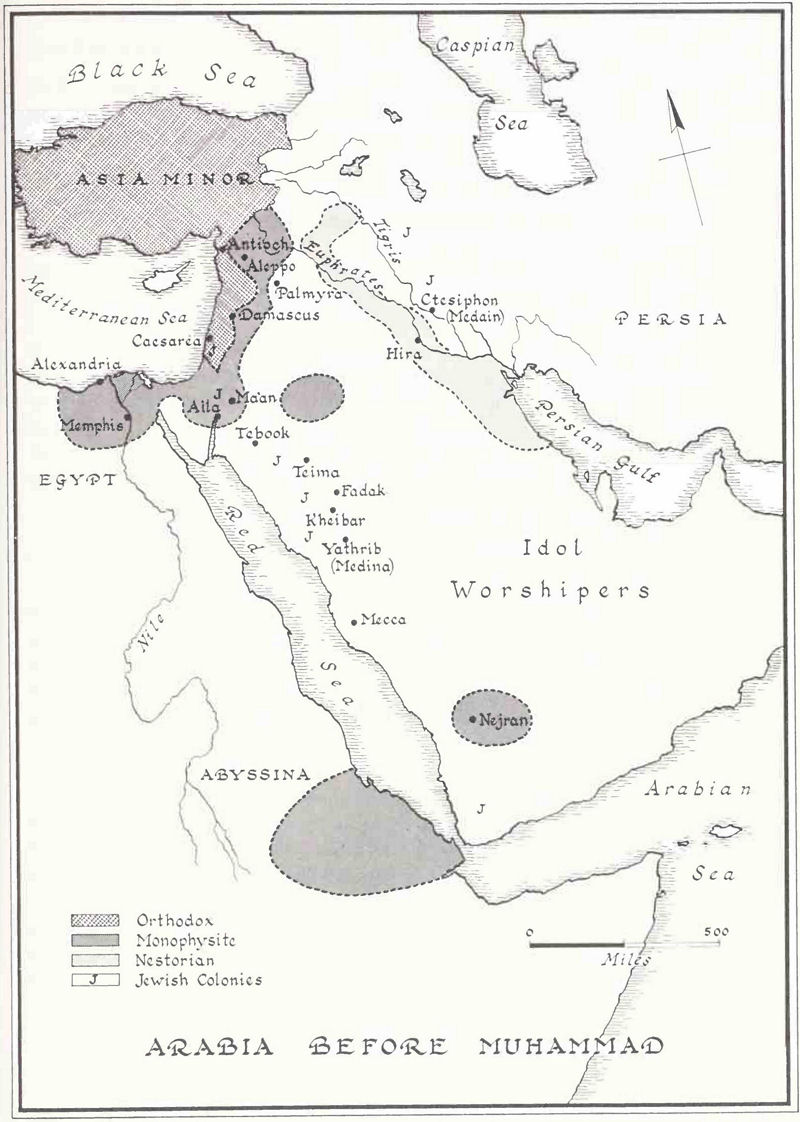

Arabia before Muhammad

![]()

190

1. The Patriarchal Period and the Omayyad Empire

The rise of the Arabs and the foundation of a new empire originating from the deserts of Arabia at the beginning of the sixth century is one of the most fascinating phenomena in world history. It was evoked by the prophetic visions of an extraordinary man, Muhammad, who was born in Mecca about 570. He was a true son of Arabia and, moved by the religious backwardness of his compatriots, who were still pagan and were leading a precarious existence amid the sands of their deserts, he devoted himself to profound religious speculation. In the course of his commercial travels on behalf of the rich widow Kadijah whom he had also married, he had occasion to become acquainted with all the varied elements of the religious life of Arabia — the paganism of the Bedouin and of the urban communities — but he was also in touch with Christianity and with Judaism. Some monotheistic aspirations were noticeable even among Arab pagans. The contact with Christian and Jewish teachings profoundly influenced his receptive mind. Rejecting all the pagan conceptions of the Arab tribes, he began to assert that there was only one God, Creator of the universe. Convinced that he was predestined by his Allah to convert his countrymen, he lived through a profound crisis during his retreat on Mount Hira. Here he thought he had visions and heard voices, especially that of the Angel Gabriel, inviting him to reform the worship of Allah according to the principles contained in a heavenly book (Al Kitab). He started to preach the repudiation of all native polytheism, exalting only Allah above all. He stressed the moral and social responsibility of men, the last judgment, the existence of hell and punishment of sinners, and of heaven for the souls of those faithful to Allah and his principles. He found his first adherents only among the poorer social classes, and the opposition of the wealthy aristocracy forced him to leave Mecca and to establish himself with his adherents in Medina. This “hegira” of September 622 marks a new era for his teaching and for the Arab world.

Supported by his companions and by emigrants from Mecca, Muhammad revealed considerable diplomatic and political skill, when he succeeded in being accepted even by his opponents as their political leader.

![]()

191

The rejection by the Jews and the Christians of his invitation to adhere to his faith contributed to a more positive affirmation of his mission. He declared himself to be the last Prophet, who was instructed by Allah to purify the monotheistic belief of Abraham which had been corrupted first by the jews and then by the Christians. The Ka’ba, believed to be the altar built by Abraham, was promoted to be the central point of devotion, to which his faithful had to turn when praying to Allah. Pilgrimage to this center was introduced, and the Jewish custom of fasting was replaced by Ramadan. Muhammad was able to strengthen his position in Medina by conventions with the Bedouins and by the persecution and expulsion of the lews. The war with Mecca, waged with varied military success and astute diplomacy, ended with the acceptance of Muhammad in 630 and was followed by the recognition of his leadership by many tribes. When he died in 632 almost the whole of Arabia was unified under the religious and political leadership of Muhammad.

Nationalist sentiment and the religious zeal of the tribes called for foreign conquest. Rich booty attracted the poor Bedouins, and paradise was promised to those who should fall in the fight for the spread of Islam. The conquest of foreign lands was the task of the first caliphs. Abu Bakr (632-634) initiated the conquests with expeditions against the Persians and the Romans. Omar (634-644) defeated the Persians, subdued Iraq, and founded two new Arab cities, Kufa and Basra, in 635, the same year in which Damascus fell into Arab hands. In 638 Jerusalem was taken. In 640 followed the invasion of Egypt and the capture of Alexandria. A new city was founded called Fustat which later became Cairo. In 641 Persia was again invaded and the flight of the last Sassanid king brought the definitive subjection of Persia to the caliph in 643. During the reign of the third Caliph Othman (644-656), at whose behest the compilation and canonical fixing of the Koran was carried out about 650, the Arabs reached Armenia and Asia Minor in the north and Carthage in Africa. After Othman’s assassination Ali became caliph (656-661) but after some attempt at a settlement he was deposed by Muawiya, governor of conquered Syria (658), and founder of the so-called Omayyad dynasty which reigned over Arabia and the conquered lands for ninety years. This marked the beginning of the Arab Muslim Empire with Damascus as its capital.

Arab success was consolidated also by the establishment of an Arab naval force. This was initiated by Muawiya when he was still governor of Syria. In 649 he seized Cyprus with his navy and soon raided Sicily for the first time.

![]()

192

In 655 the Arabs won their first great naval victory when they defeated the Byzantine navy near Alexandria. This inaugurated Arab naval supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean. The previous balance of forces between East and West was thus destroyed. Nevertheless, the theory that this event had disrupted the continuing unity of the ancient world and exercised an almost disastrous effect on the economic and cultural development of med ieval western Europe, as propounded by the Belgian historian H. Pirenne, is overstressed. In spite of piratical incursions into Italy in the later period, the Arabs did not succeed in cutting off the Byzantines entirely from Italy. Commercial intercourse with the eastern lands occupied by the Arabs continued, although in a very limited way because of the insecurity of sea travel. It was, however, most unfortunate for the development of medieval Europe, that, at the same period, the “Illyrian bridge” between East and West — the Roman and Byzantine provinces of Illyricum where Latin and Greek elements were culturally intermingled — was destroyed by the invasions of the Avars and the occupation by the Slavs. These two facts, Arab control of a great area of the Mediterranean Sea and the disappearance of the “Illyrian bridge,” are responsible for the growing estrangement between East and West which resulted in western Europe having to develop on its own basis during the Middle Ages.

Some explanation is needed for the unbelievably rapid conquest of highly cultured nations in the Eastern provinces of the Roman or Byzantine Empire by a new race that had hardly been touched by this civilization and led a nomadic life in the deserts of Arabia. Persia never recovered from the blows inflicted on its shahs by the Emperor Heraclius. On the other hand, the Persian wars had exhausted the forces of Byzantium. Moreover, the Byzantine provinces were alienated from the empire by heretical movements which the emperors tried in vain to eliminate, reintroducing the orthodox faith by methods not always peaceful and humane. The Egyptian Copts and the Syrians, mostly Monophysites denying two natures to the incarnate Christ, were unmoved by the exhortations to fight the invaders. A similar situation arose in Iraq and Persia, mostly adherent to Nestorianism, denying to Christ the Son a divine nature after his incarnation. Moreover, the Byzantine army was not numerous enough to stop the sudden onslaught. Byzantium must have had almost no intelligence on what was happening in Arabia, although Christian communities still existed in southern Arabia, especially in Yemen.

![]()

193

The suppression of the imperial post in Africa by Justinian contributed to this lack of intelligence of Arab movements.

The Arabs, inspired by their new faith and convinced that it had been revealed to them by Allah through his Prophet Muhammad, were zealous to impose it on other nations. The Bedouins, used to a hard life in the desert and being excellent riders, were eager to obtain rich booty which would transform their simple life, and they became valiant warriors. The rapidity of their strategic movements can be explained also by the fact that the Arabs often used camels in their expeditions.

During the patriarchal period of the first four caliphs the problems of organizing and administering the new state were not yet actual. It was a period of military conquest during which the generals and tribal chiefs played the main role. For practical affairs they relied on the Byzantine or Persian administrative machinery as long as its officials were prepared loyally to carry out their instructions. When the era of conquest was ended, the administration of the new empire with all its problems was in the hands of the new dynasty of the Omayyads. At first they divided the administration of their empire into nine large districts along the lines of the provinces of the former Byzantine and Persian empires. But soon some of these were combined, and this operation resulted in the creation of five viceroyalties. The most important was al-lraq, which included most of Persia and eastern Arabia with Kufa as its capital, later Khorasan, Transoxiana with Merv and the two Indian provinces of Sind and Punjab were added; the remaining vice-royalties and provinces were. Western and Central Arabia; al-Japhah, the northern part of the land between Tigris and Euphrates, Armenia, Azerbaijan and parts of Eastern Asia Minor; Upper and Lower Egypt; Africa (west of Egypt) with Spain, Sicily, and the adjacent islands.

The viceroys had to appoint their own prefects for their provinces and had full administrative and military powers. The caliphs appointed judges-non-Muslims retained their own canon judiciary -and financial inspectors. A special dignitary was appointed to represent the caliph in the saying of official prayers.

The rulers of the new empire had to face immense problems in organizing its administration, ruling the conquered nations, and reconciling the universalist appeal of their faith with Arab nationalist pride and primitive tribal customs. Omar tried to organize the Arabs into a kind of religio-military commonwealth from which all non-Arabs should be excluded.

![]()

194

Taxes were imposed on the non-Muslim subject population, a “poll” tax and a land tax. Omar’s military constitution securing the ascendancy to Arabism was too artificial and his prohibition on Arabs holding property in conquered lands was rescinded by Othman. The five caliphs were forced to adapt their administration to the customs introduced by Romans, Byzantines, and Persians in the conquered lands.

Persian and Byzantine influence manifested itself also in the Arab division of the army. As in Persian and Byzantine times, the battle organization of the army had its center, two wings, vanguard, and rear guard. The only Arab innovation was that in the division of the army the tribal unit system was preserved, each tribe having its own standard. 01 course the non-Muslim population was excluded from serving in the army.

The new dynasty ended the patriarchal period of Arab history under the first four caliphs. In order to preserve the unity of the Arab people and its hegemony over its vast empire, it had to introduce a strongly monarchic element into the administration. The Omayyads were, of course, anxious to maintain their family’s preeminence in the Arab world and tried also to replace the old Arab principle of succession between brothers by direct hereditary succession.

The way to a monarchic system planned by them was not easy. They had first to combat the traditional Arab particularism, represented especially by the Bedouins who showed their repugnance to any discipline and government organization. Because the ancestor of the dynasty, Abu Sufyan, had for some time refused to join Muhammad, the puritans among the Arabs, called Kharijites, lacked any enthusiasm for a dynasty whose ancestor had participated so little in the original affirmation of their faith. There was also the legitimist party of the Shi’ites, composed of the faithful followers of the unfortunate Ali. Another danger threatened the Omayyads from the side of the Abbasids. who were descendants of the Prophet’s uncle, Abbas.

The Omayyads continued to struggle with the problem inherited from the patriarchal period, namely the reconciliation of the national sentiments of the Arab people, which provided tlie leading cadre of the immense new empire, with the universalist stamp of their religion. Fiscal interests aggravated this dilemma. According to Islamic theory new converts had to be freed from the taxes imposed on non-believers. Some attempts had been made to implement this principle, but Arab racial pride refused to bow to the idea that non-Arab neophytes should be put on the same level as the racial Arabs,

![]()

195

and down to the end of the Omayyad dynasty this problem could not be satisfactorily solved.

Fortunately, the dynasty found a firm foothold in the Syrian population, which Muawiya had been ruling for twenty years as governor appointed by Omar. He chose able collaborators, and with the help of one of them, Ziyad, whom he adopted as his brother, the first Omayyad caliph was able to restore order and obedience to the new dynasty. Muawiya showed extraordinary talent as a military organizer. He suppressed the archaic tribal organization in the order of the army as well as many other relics of the ancient primitive period, and created from the military raw material of his Syrians a first-class army-well-ordered, disciplined, and devoted to its Syrian caliph.

Regarding Byzantium as the most dangerous enemy, he tirst completed the long cordon of fortifications near the Byzantine borders protecting Syria and Mesopotamia. Tarsus with its fortifications had to watch over the passes through the Taurus Mountains which separated the Arab lands from Asia Minor. It would serve also as a military base for Arab incursions into Byzantine territory.

While still insecure in his new position, Muawiya concluded a truce with the Emperor Constans II (641-668), promising yearly tribute to the emperor, as mentioned by Theophanes (ed. de Boor, p. 347). Soon, however, new hostilities started with invasions of Asia Minor by Arab forces. When he felt more secure in his position, Muawiya made plans to conquer Constantinople itself. In 669 his army, led by the crown prince Yazid, reached Chalcedon and took the city of Amorion. The energetic Emperor Constantine IV (668-685), however, forced the Arabs to raise the siege and regained the conquered city. A second attempt to take Constantinople was made between 674 and 678 during the so-called seven years’ war, waged mainly between tbe Arab and Byzantine fleets in the sea of Marmara. Rhodes and Crete were temporarily occupied. The newly discovered Greek fire raised havoc among the Arab fleet, and bands of freebooters from the Taurus Mountains called Mardaites (rebels) threatened Syria and induced the caliph to conclude peace with the Emperor Constantine IV. The Byzantine envoy called Johannes, an experienced statesman, accompanied the Arab envoys to Damascus and concluded a peace which was to last thirty years under very advantageous conditions for the Byzantines. Constantine’s victory over the Arabs and their capitulation to a Christian emperor provoked a great sensation among the Christian rulers of western Europe, who sent embassies of congratulation to the victor.

![]()

196

The Mardaites who had contributed to the glorious event were freebooters of uncertain origin, who lived almost independently on the heights of Mount Taurus. They were Christians and supporters of Byzantium, and were called by Theophanes (ed. de Boor, p. 314) “a brass wall of the Empire on the Taurus.” Already about 666 their hands pierced the Arab defenses and penetrated into Lebanon, becoming a nucleus around which many fugitives and Christian Maronites grouped themselves. They were called apelatai (outlaws) by the Arabs. A new invasion of Syria was made by the Mardaites in 689. The Caliph Abdalmalik (Abdul-Malik) (685-705) had to ask the Emperor Justinian II to withdraw his support from the freebooters. He agreed to pay a thousand dinars weekly to the Mardaites and accepted new conditions laid down by Justinian, who promised to settle the Mardaites on Byzantine territory. The majority of them evacuated Syria, but many stayed in Lebanon, where they strengthened the Maronite community which still exists in northern Lebanon.

The Caliph Sulaiman (715-717) made another daring attempt by sea and by land to capture Constantinople, in a siege lasting from August 716 to September 717. But the Emperor Leo III the Isaurian (717-741) was ready for the onslaught. He barred the way of the Arab fleet into the Golden Horn with the famous iron chain. With the help of the Bulgars he defeated the Arab army, and the Greek fire destroyed a great part of the Arab navy. A sudden tempest completed the disaster. According to Theophanes (ed. de Boor, pp. 395, 399), only a few Arab vessels were able to reach port in Syria. The Arab army had to content itself with yearly invasions through the Taurus passes into Asia Minor, but was unable to make any serious and stable progress on this front.

When surveying the policy of the Omayyads we are struck by their attitude towards Byzantium. Of course, for all Muslims. Byzantium (Bum) was the archenemy, an infidel power against whom the holy war had to be waged. The three daring attempts at the conquest of Constantinople itself may be explained by this attitude of the Muslims towards the infidels. However, there seems to have been more to the Omayyad frame of mind concerning Byzantium. The Omayyad caliphs apparently regarded themselves as successors of the Rūm and intended to establish themselves in Byzantium as heirs of its emperors. There are some aspects in their policy which point quite clearly to a kind of Byzantinization of their administration.

This can be easily explained. The most loyal supporters of the Omayyads were the Arab tribes already established in central and southern Syria before the Islamic conquest.

![]()

197

Many of them had been enrolled as auxiliaries of the Byzantines in their wars with Persia. They had been trained in Greek methods of warfare, and many of their chiefs had held Byzantine titles. This explains also why the Arabs had so quickly mastered Roman and Byzantine military art, a fact which helped the untrained Bedouin tribes in their astonishing conquest. Byzantine officials continued largely to direct the administrative machine in Syria during the first years of the Omayyad dynasty.

This certainly influenced to some degree the administrative policy of the caliphs. Other Byzantine institutions continued to exist in Syria and Mesopotamia. The caliphs appreciated their practical usefulness. We can see Byzantine inspiration in one interesting innovation by Muawiya. In order to regularize the official correspondence of the caliph with the viceroys and other functionaries, Muawiya created a kind of registry which should function as a state chancery. In order to prevent falsification of the caliph’s letters this bureau had to make a copy of every official document which was to be sealed before being dispatched. The copies of the original document had to be kept in the chancery. This system was improved by the Caliph Abdalmalik, one of the best statesmen of this dynasty, so that the Omayyads thus developed a state archive in Damascus, an act which recalls Byzantine practice.

An imitation of Byzantine practice can also be seen in the introduction of gold coinage by Abdalmalik. The first Arabic gold coins even bore the caliph’s effigy, which was not in accord with the religious tenets of the Muslims. Previously the striking of gold coinage had been the privilege of the emperor. Ihe Omayyads also kept the Byzantine revenue administration, and small adjustments to Byzantine practice are to be seen in Arab and Islamic ceremonial. Byzantine usage, namely defining legal norms by administrative rescripts, was also imitated by the Omayyads.

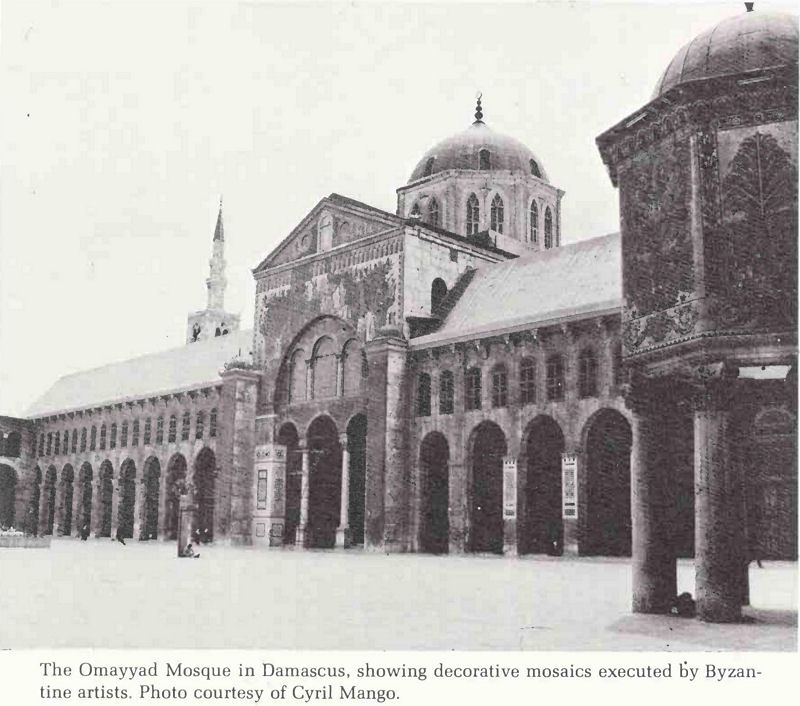

Another kind of Byzantine imperial legacy during the Omayyad period is to be seen in the erection of imperial religious monuments, especially the reconstruction of the Prophet’s Mosque at Medina, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, and the Mosque of Damascus. Recently H. A. R. Gibb has shown that the report of some Arab historians that the Caliph Walid I (705-715) had asked and obtained from the Byzantine emperor, probably Anastasius II, mosaic cubes and craftsmen to decorate the mosques of Medina and of Damascus is founded on a solid basis. Commercial intercourse between Byzantium and the Arabs does not seem to have been interrupted by the wars.

![]()

198

The Omayyad Mosque in Damascus, showing decorative mosaics executed by Byzantine artists. Photo courtesy of Cyril Mango.

![]()

199

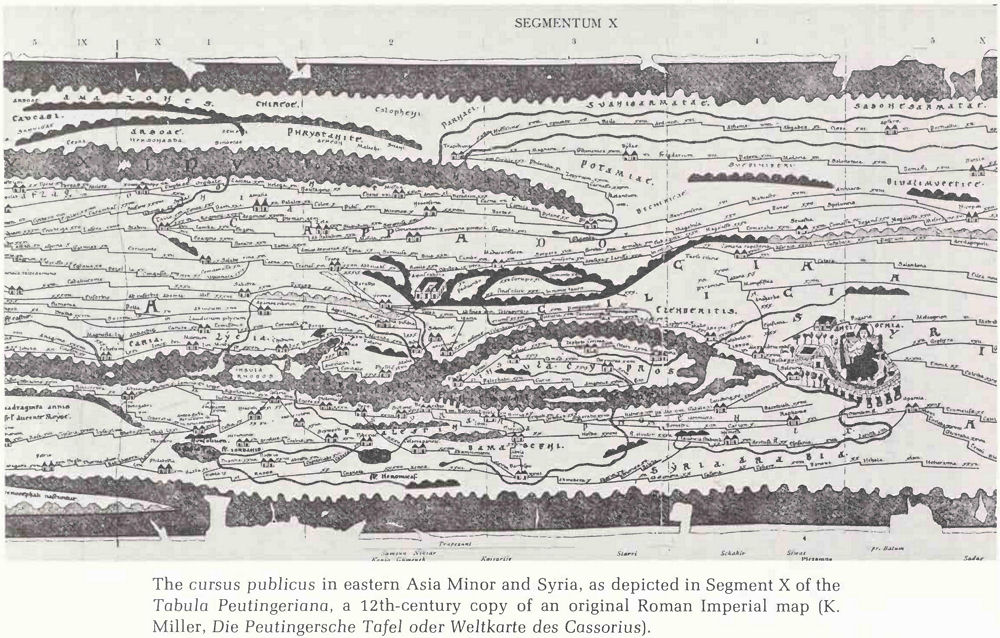

Far from suppressing what was left of the Roman and Byzantine cursus publicus, the Arabs imitated the emperors in taking care of the roads and using them for state affairs, as had been done by the Romans and Byzantines. They even imitated the Roman milestones. The Roman millia was transposed into Arabic as mil and the Arabic name for the cursus publicus — barid — is derived from the Latin word veredus, meaning horses used for the state post. Muawiya was the first to appreciate the importance of this Byzantine inheritance in lands conquered by the Arabs.

Abdalmalik saw the necessity for the new régime to enjoy a good intelligence service from all parts of the empire. Using the Byzantine and Persian post system, he therefore established a regular postal service to facilitate the prompt delivery of official correspondence and to obtain information on what was happening in the provinces. Following the Byzantine practice, he created numerous relays of horses between Damascus and the capitals of the provinces. The new Arab state post was also able to transport officials from distant provinces with great celerity. In cases of necessity even detachments of the army could be sent to their destination by the post organization. The Caliph Walid found the post very helpful in connection with his building operations. Omar II (717-720) is said to have erected special relays (khans) on the Khorasan road for the post.

We have little information on the organization and functioning of the Arab post system during the Omayyad period. It seems, however, that it was based on regulations which had been introduced by the Romans and Byzantines. The barid was intended to serve only state interests, and special permission for its use had to be given by the governors of the provinces. This permission had to be given in writing, a fact which recalls the Roman tessera and evectio. This can be concluded from some Arab papyri preserved in the John Rylands Library in Manchester and published by A. S. Margoliouth. The papyri date from a.d. 751-753. In these documents the postmaster of Ushman in Upper Egypt, who is given the title of sahib barid, is asked by his governor to let certain government messengers — one of whom was in the service of the governor himself—use the service of the barid.

Military operations were also aided by the barid. According to J. Wellhausen (p. 233), quoting Tabari’s Chronicle, Haijaj, viceroy in Iraq, sent an army in 669-670 against the T’u-chüeh king of Kabul (modern Afghanistan), who had refused to pay the tribute. As his campaign progressed, Abd-al Rahman, the commander of the army,

![]()

200

gradually established a regular postal service with relays and barid horses in order to ensure his lines of communication.

The difficulties which the first Omayyad caliph had to face, especially from the Shi’ites, had shown Muawiya how important it was to have good intelligence about any possible anti-dynastic movement. This necessity was especially understood by his adopted brother Ziyad. He was first appointed ruler of Basra, a center of Shi’ism. When elevated to the government of Kufa he became the absolute ruler of the whole eastern part of the empire, including Arabia and Persia. It was the most important but also most turbulent part of the empire. In order to exterminate all opposition to the caliph he organized a widespread intelligence and spying service. He chose 4,000 reliable men to act as his bodyguard, but also to serve as spies and as a secret police in his territory. The Shi’ite opposition was stubborn, and it was only thanks to this merciless secret police and spying system that the new dynastic régime could survive against all the intrigues and conspiracies.

These military attempts against Constantinople and the administrative adaptation of Byzantine usages and traditions both demonstrate that the first Omayyads adopted the pretext of being heirs of the emperors and were determined to replace them. From their capital they hoped to rule their inheritance of the Roman and Byzantine Empires.

This, of course, did not mean that they were neglecting their duties in promoting Arab national interests. This is illustrated by the innovations made by Abdalmalik.

The reign of Abdalmalik is characterized by a profound Arabicization of the state. He changed the language of the public registers from Greek to Arabic in Damascus, and from Pahlavi to Arabic in al-Iraq and the eastern provinces. This naturally caused a change in the personnel charged with the registers. The first caliphs kept in the conquered Greek lands those officials who wrote only in Greek, and in Iraq and Persia those who wrote only in Persian.

Under the reign og Muawiya some Christians occupied important functions in the administration and were received at his court. The most prominent among them was Sargun ibn Mansur, who held the office of finance administrator to the caliph. His son was a boyhood friend of the future Caliph Yazid and worked in the bureau of his father. The new course of affairs introduced by Abdalmalik put an end to their careers. Mansur’s son entered a monastery in Jerusalem and became one of the most famous theologians of the Eastern Church — St. John of Damascus.

![]()

201

One can suppose that some Christian or Persian employees who had learned Arabic continued to serve under the new regime, the more so as the old system was not changed. As there were not many Arabs familiar with administrative work, the change went on very slowly, and was continued under Abdalmalik’s son and successor Walid I (705-715).

Even when their first preoccupation was to conquer the residence of the emperors, the Omayyads did not neglect the extension of their power in the East. The conquest of the territory beyond the Oxus, started by Muawiya, was pushed as far as the river Jaxartes; the cities of Khiva, Bokhara, and Samarkand became centers of Muslim propaganda. The supremacy of Islam in Central Asia was thus established. In 710 an Arab army crossed the territory of modern Baluchistan and conquered Sind, the lower valley of the Indus with its seacoast. This was the beginning of the Islamization of the Indian border provinces, where the Muslim state of Pakistan was to be established in modern times.

Even more important was the reconquest and pacification of northern Africa by the governor Hassan, a conquest which was extended by the governor Musa as far as Tangier. The Hamitic Berbers, although in great part Christianized, were gradually Islamized and also Arabicized. Musa and Tariq, a Berber freedman, crossed the straits in 711 and began the conquest of Visigothic Spain. Gibraltarjebel Tariq, the Mount of Tariq — still recalls this deed. The conquest of the Iberian peninsula was the most sensational campaign of the Arabs. They even crossed the Pyrenees, but after the capture of some towns in southern Gaul they were stopped by Charles Martel in the famous battle between Tours and Poitiers in 732.

This happened during the reign of the last able and venerated caliph of the Omayyad dynasty, Hisham (724-743). He is rightly regarded by Arab historians as a true statesman of the Omayyad dynasty, on a level with Muawiya and Abdalmalik. It was also under Hisham that the change of Arab policy from the Byzantine tradition towards the Eastern was most clearly marked. Some of the other caliphs of the dynasty were unworthy of their high position. Following the example of Yazid II (720-724), they passed their time in hunting, drinking wine, indulging in luxury due to increased wealth, and enlarging their harems; they were more absorbed in music and poetry than in religious and state affairs. As there was seldom a strong hand on the throne, the typical weaknesses of the Arab nature — inclination to individualism, tribal spirit, and feuds asserted themselves increasingly.

![]()

202

The most dangerous feud existed between the North Arabian tribes which had emigrated into Iraq before Islam and the South Arabian tribes of Syria.

These tribes were never fully amalgamated and their jealous aspirations and ambitions poisoned Arab political life, precipitating the downfall of the dynasty. The situation was complicated also by the lack of any fixed rule of hereditary succession. In this way the initiative of Muawiya, who had tried to introduce the hereditary system in the succession to the throne, failed to break the antiquated tribal principle of seniority in succession. Of the fourteen caliphs of the dynasty only four had their sons as immediate successors.

The activity of the Shi’ites, always hostile to the “usurpers,” became very lively in Iraq and the majority of the population joined them, mostly in opposition to Syrian rule. National feeling formed the background to this development, the Persians regretting the loss of their national independence. Under the guise of Shi’ism. Iranianism was coming back to life. This development was accelerated by the fact that the Omayyads had not succeeded in granting to the non-Arab Muslims, who were mostly representative of a higher and more ancient culture than that of their conquerors, exemption from the capitation tax paid by non-Muslims.

Of course, this dissatisfaction spread from Iraq to Persia and to the northeastern province of Khorasan, while the extravagance of the worldly-minded caliphs provoked strong condemnation from the purists. They charged them with neglect of Koranic and traditional laws and were ready to give their religious sanction to any political opposition.

All these manifestations of dissatisfaction prepared the downfall of the dynasty. Its end was sealed when the Shi’ites of Iraq, Persia, and Khorasan made an alliance with the descendant of Muhammad’s uncle, also called Abbas, who became the head of the coalition. The well-prepared revolt started in 747 when the revolutionaries unfurled the black banner, originally the standard of Muhammad and now that of the Abbasids. The dissatisfaction had heightened during the reign of the dissolute successors of Hisham, and the last caliph of the Omayyad dynasty, Marwan II, was unable to stop the revolution. Abbas was proclaimed anti-caliph in 749 in Kufa. The last desperate stand of Marwan was crushed, and even Damascus capitulated in 750. The fugitive caliph was taken prisoner and killed in Egypt. The new caliph, founder of the Abbasid dynasty, disposed quickly and brutally of any danger of counter-revolution by exterminating every member of the defeated dynasty and all its branches. Only one youthful member, Abd ar-Rahman I, made a dramatic escape to Spain,

![]()

203

where he succeeded in establishing a new Omayyad dynasty which wrote some brilliant pages in Spanish Muslim history.

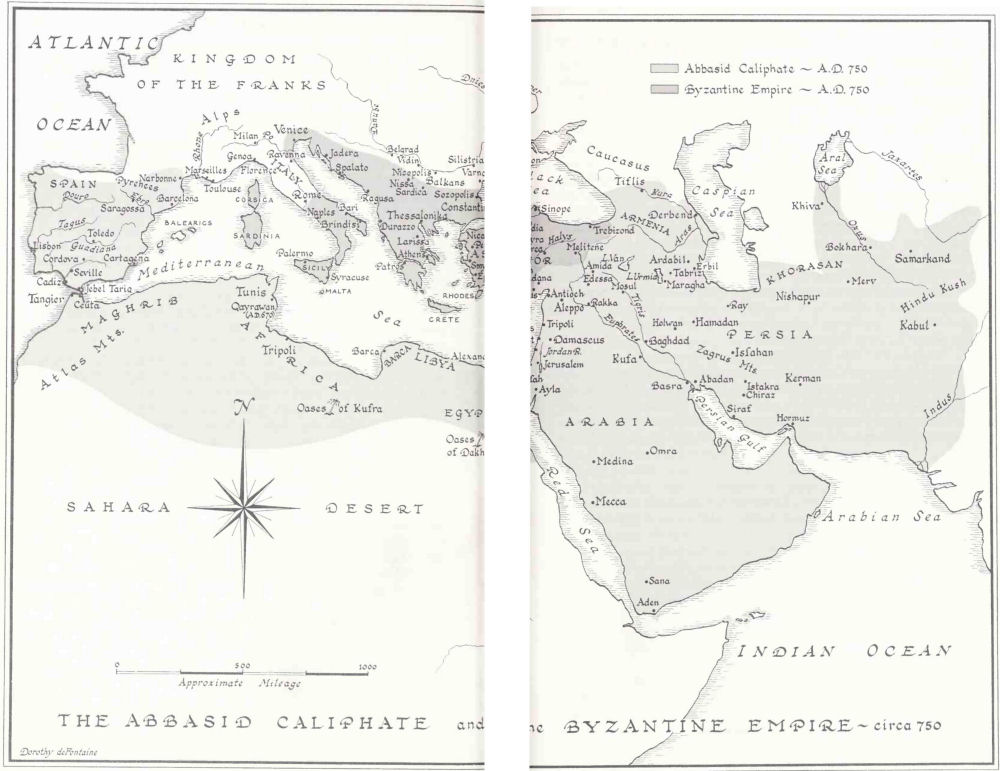

2. The Abbasid Muslim Empire

The Caliph Abbas, or Abu-l-Abbas al-Saffah (750-754), opened a new period in Arab history as the founder of a dynasty which reigned, even if it did not always rule, from 750 to 1258. The installation of a new dynasty was thought to have realized the true conception of the caliphate as a theocratic regime, replacing the Omayyad idea of a purely secular state. Such a characterization of the rule of the Omayyad and Abbasid dynasties was only partly justified. It is true that the religious character of the caliphate was emphasized by the new ruler who on ceremonial occasions began to don the mantle of Muhammad, and surrounded himself with men versed in Koranic and canon law. In reality, however, the Abbasids were as worldly minded as their predecessors, in spite of their religious veneer.

There was, however, one fundamental difference between the empires ruled by the two dynasties. The Omayyad Empire was Arab. Its rulers failed to put forward the universal character of their religion, a fact which was to prove fatal to them. The Abbasid Empire was a Muslim Empire in which all who had accepted the Prophet’s faith were equal in rank, without distinction of race. The Arabs were no longer the dominant race, but only one of the many races of which the empire was composed. The center of the new political power was also changed. It was not in Syria, but in Iraq and Persia, where the revolution of the Abbasids had started. Not Damascus was its capital, but a new city. Baghdad. This city, built by Al-Mansur (754-775), brother and successor of Abbas, was near the old Sassanid capital. Ctesiphon, on the Tigris. Al-Mansur was also the real founder of the Abbasid Empire. He ruled as an absolute monarch and never hesitated to eliminate any kind of disloyalty to the new dynasty. The Shi’ites realized too late that the new caliphs were as deaf to their claims and as unscrupulous as their predecessors. New heretical movements appeared, brought about by the combination of extreme Shi’ite ideas with the ancient religious and social doctrines of old Iran. Al-Mansur himself massacred without mercy the members of one Iranian sect which claimed that he should be adored as a god.

![]()

204-205

The Abbasid Caliphate and the Byzantine Empire circa 750

![]()

206

The equality of all races of the Muslim Empire was bound to produce some effects which were dangerous to the orthodox Muslim faith. Old Iranian religious ideas were not completely forgotten, and many thinkers and politicians of Iranian stock were tempted to combine these with Muslim teaching, endowing them sometimes with social and political significance. Al-Mansur’s son Al-Mahdi (775-785) felt obliged to create a kind of inquisitorial organ in order to suppress heterodox movements and dualistic ideas of Iranian origin which were fermenting the intellectual classes of Iraq. Many intellectuals became victims of this persecution.

Soon another danger threatened to disrupt the unity of the immense empire. The principle of the equality of all races awakened national or tribal motives, and memories of national or tribal independence. This often provoked revolts against the monarchic caliphate. Harun Al-Rashid (786-809), one of the most celebrated caliphs, initiated a policy which was to lead to the dismemberment of Muslim unity, when in 799 he granted to the Aghlabids of Tunisia investiture as sovereign tributaries and vassals, making them in fact almost independent of Baghdad.

On the other hand the de-arabization of the empire opened the literary treasures and scientific and medical achievements of the Hellenistic and Syriac age of the newly Muslimized nations to the Arab world. An Arab literary and scientific renaissance resulted from the appropriation of these treasures by Arab intellectuals, who propagated these discoveries in their translations from Greek and Syriac. In one respect the Arabs could record a great national victory. Almost all the Muslirnized nations of the Abbasid Empire adopted the Arabic language and expressed their ideas and the achievements of their new culture in the language of their conquerors. The fusion of the old Arabic traditions with the talent of the conquered is well illustrated by the fact that Harun owed the greatness and fame of his reign to the assistance of his vizir Yahya al-Barmaki, who was from a family of purely Persian origin. The fame of Harun Al-Rashid penetrated to China, the far east, and into the west, whose greatest ruler Charlemagne entertained diplomatic relations with the great caliph.

A deep dynastic crisis arose after Harun’s death, owing to a fratricidal war between the designated heir Caliph Al-Amin (809813) and his brother Al-Mamun. Although this led to the destruction of a part of Baghdad besieged by Al-Mamun, the intellectual and cultural life continued to flourish under Al-Mamun (813-833) — half Persian through his mother — and his immediate successors.

![]()

207

Al-Mamun himself embraced the theories of the Mu’tazilitist rationalist school, which maintained that religious texts should agree with the judgment of reason and that the sacred books were created in the course of time. This cannot be interpreted as “free thought,” but rather as a philosophical and theological school which laid more emphasis on rational speculation than on the mere acceptance of tradition.

Justification for such a doctrine, declared to be a state doctrine in 827, was sought in the philosophical works of the Greeks. For this purpose Al-Mamun established in Baghdad in 830 his famous “House of Wisdom” which combined together a library, an academy, and a bureau for the translation of scholarly works. The translators were not interested in Greek literary and poetic works, but mainly in philosophical and scientific ones. From that time on translations were mostly centered in the newly founded academy. It was the most important scholarly and educational institution since the Library of Alexandria was established in the first half of the third century b.c. Even Syrians and Christian Jacobites participated in the translations. Through them Neo-Platonic speculations were introduced into the Arabic mind.

So it came about that towards the end of the tenth century the Arabs possessed translations of all of Aristotle and of other Greek philosophical works, at a time when the West was completely unaware of the Greek philosophical treasures. The Christian West became acquainted with Aristotle and Plato through Arabic translations emanating from Muslim Spain and Sicily.

During this golden age of the Muslim Empire many original works were also composed in Arabic, especially in geography, astronomy, medicine, and history. The old Arabic religious zeal also flared up again and turned against the infidels of Byzantium. The third Abbasid Caliph Al-Mahdi (775-785) renewed the old struggle, trying to regain the territory lost in Armenia during Arab internal conflicts.

The Arab army led by his son Harun, the future caliph, appeared on the Bosporus in 782, on the site of modern Scutari. The Empress Irene had to conclude a humiliating peace involving the p arm eut of large sums to the Arabs. Harun obtained from his father the honorific title Al-Rashid (the straightforward) for his deeds. When Nicephorus I (802-811) refused to pay the promised money, Harun invaded and ravaged Byzantine territory and captured Heraclea and Tyana (806). He imposed a new tribute on the emperor. In 838 Al-Mu’tasim (833-842) tried to obtain a foothold in Asia Minor. His huge army invaded Byzantine territory and occupied Amorion, the birthplace of the ruling dynasty.

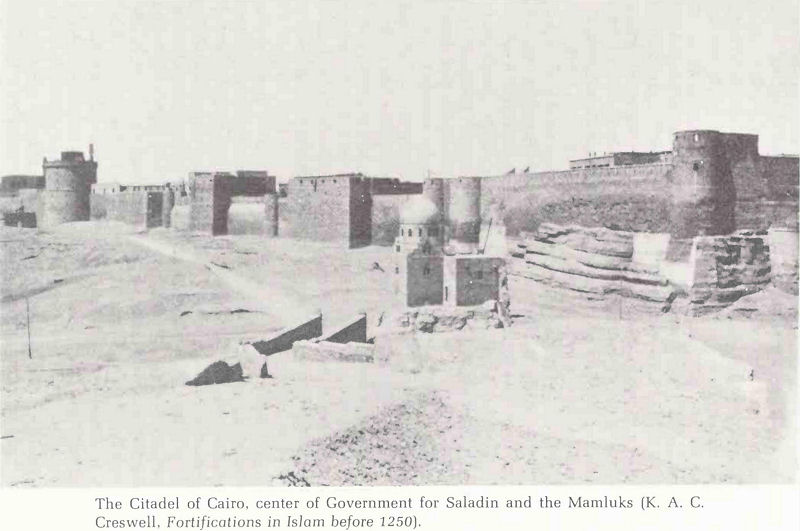

![]()

208

The attempt to reach Constantinople had to be abandoned because of alarming intelligence of conspiracy in Baghdad. This was the last serious attempt of the Abbasid caliphate to conquer Byzantium. After that the Arabs had again to limit themselves to yearly incursions through the Taurus passes into Asia Minor. The strength of the caliphate was waning because of the slow decomposition of the empire and the formation of petty emirates which were almost independent of the caliphs. The holy war against Byzantium was only continued by one of those emirs, Sayf ad-Dawlah (944-967) of Mosul and Aleppo in Syria. The lightning appearance of Basil II in 995 at Aleppo, coming suddenly from Bulgaria, re-established Byzantine supremacy over the emirate. Saladin (1169-1193), the greatest Arab hero in the holy war against the Crusaders, was more powerful and benefited at least from good communications inside Egypt. He is the real founder of the Avyub dynasty, named after his uncle who had brought him to Egypt. After establishing the Sunnite “orthodox” faith in that land and adding Syria to his dominions, in 1175 he was granted a diploma of investiture by the Abbasid caliph of all the western provinces with Arabia, Palestine, and central Syria. After strengthening his power he crushed the Crusaders in 1187, even capturing the king of Jerusalem. After a siege of a week the city itself fell into his hands in the same year. Other Crusader territories were also taken, and only Antioch, Tripoli, and Tyre remained in their possession. For his connection with Egypt Saladin could not rely on the old post organization, but used runners and speedy camels. During the siege of Akr (Acre) by the Crusaders Saladin used swimmers and pigeons for communications with the garrison. He tried to communicate with the caliph, asking for help, but none came.

After Saladin’s death a period of civil wars among the Ayyubids followed which were partly exploited by the Crusaders. In 1229 even Jerusalem was reconquered by the Franks. Jealousies and quarrels among the Crusaders prevented them from exploiting the weakened situation of Ayyubid Egypt. The last success of the dynasty in its struggle with the Crusaders was the defeat of St. Louis leading the Sixth Crusade.

During the Abbasid period the state post was more fully developed and became a significant feature of the government. Arab historians give the credit to Harun Al-Rashid for the reorganization of the post service (barid) on a new basis on the advice of his counsellor Yahya al-Barmaki, from a family of Persian origin. The barid was headed by a postmaster called Sahib-al-Barid.

![]()

209

The relays of the post were called sikka. In Persia relays were set up after each 12 kilometers, in Syria and Arabia only at a distance of 24 kilometers.

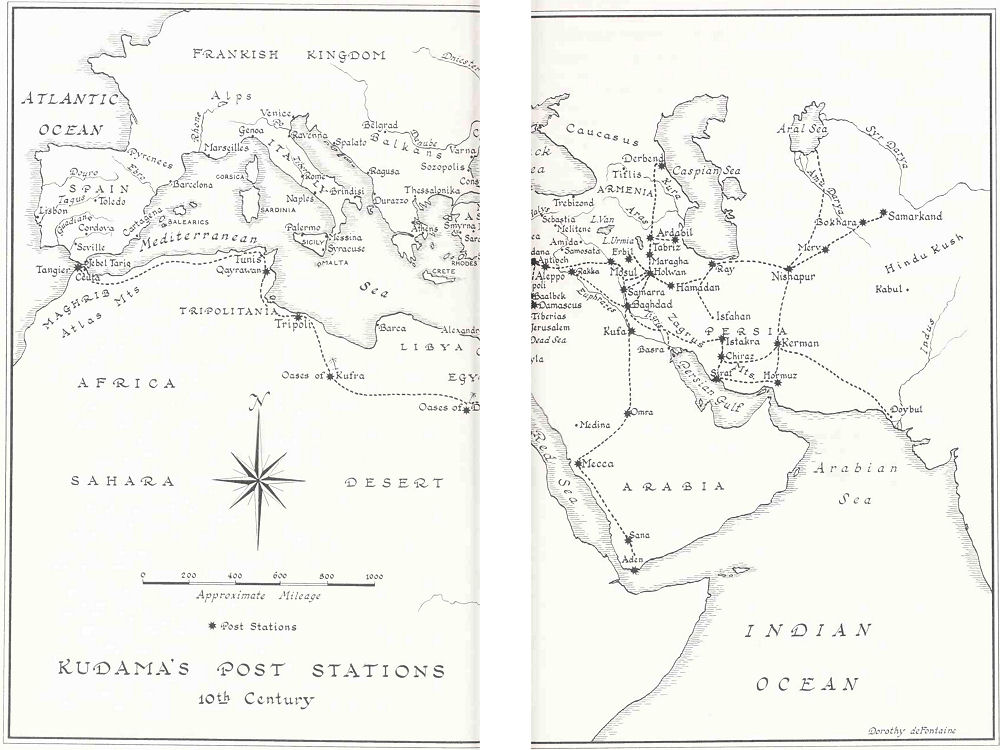

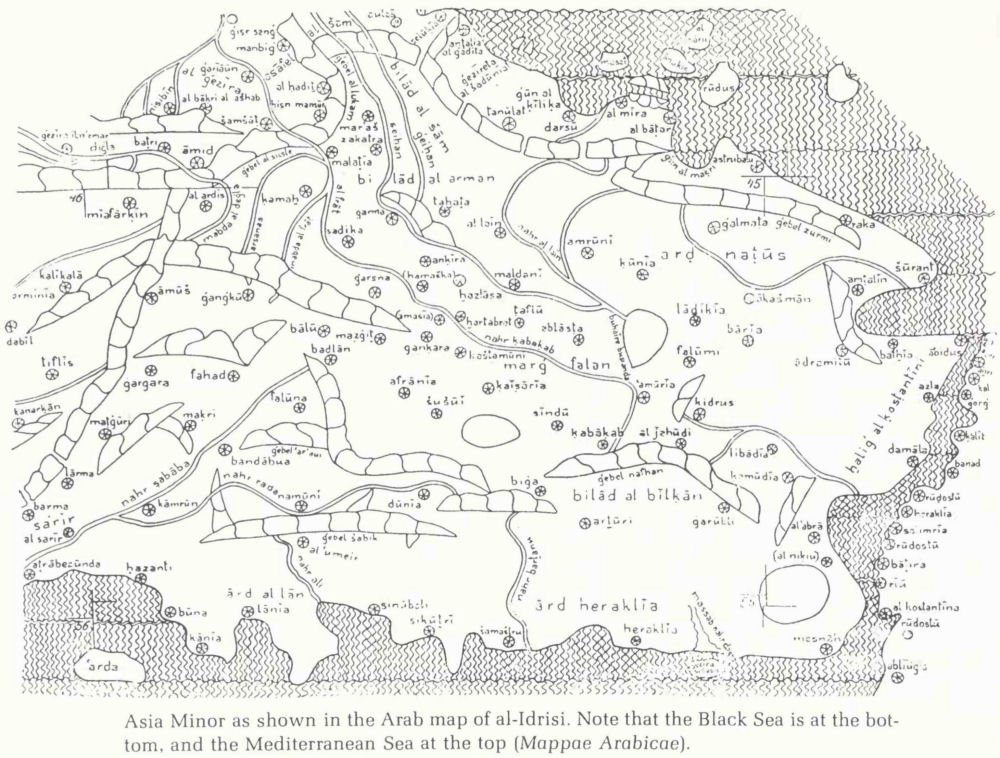

We possess some detailed information on the Abbasid state post. The most important source is the geographical treatise by Ihn Khordadhbeh called The Book on Roads and Provinces, describing the commercial roads and the postal stations of the caliphate. The author was himself a postamaster-general — Sahib-al-Barid — in al-Djabal, in the province of Iraq al-Ajami, comprising most of modern Persia. His work describes the world known to the Arabs of his time, treating especially the provinces of the caliphate and the division of the taxes, and giving a description of the roads. This book, translated into French by M. Barbier de Maynard in 1765, is based on official documents kept in the state archives.

His work, only fragmentarily preserved, was used by all Arab geographers, but gives little information on the organization of the post. It was originally intended to be an official handbook for the chancery of the government. The author died about the year 912. Ibn Khordadhbeh’s work is completed in some ways by the book On Taxes (Kitab al-Kharadj) written by Kudama, giving more information on the institutions of the state post and enumerating all its itineraries. Kudama occupied the important post of a hatib — scribe. He lived in Baghdad and died in 959.

Important information is also given by al-Mukaddasi (Mokaddasi) whose father was an architect. He visited almost all the dominions of the caliphate and described them with great precision. He is one of the best geographers of this period. He gave an account of his twenty years of travel in 986 in a book which could be translated as The Best Classification of Lands for the Knowledge of the Provinces.

Many other geographers used these three main works to give information on the Abbasid post roads. After examining all the works concerning the state post, A. Sprenger produced a detailed work in 1864 on the post stations and roads of the Arab Empire with precise maps of all roads.

Detailed descriptions of all the itineraries of the post service were kept at the post headquarters in Baghdad. They indicated not only the established stations or relays but also the distances between them. They could be consulted not only by the officials, envoys, and couriers, but also by merchants, travellers, and pilgrims to the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The geographers used them as their main source.

![]()

210-211

Kudama's Post Stations, 10th Century

![]()

212

The postal roads connected Baghdad with the farthest points of the caliphate empire, and it seems that the road system extended even to the vassal lands.

The most important postal roads deserve mention before the functioning of the post is described. The most famous road, important especially for commercial relations with the Far East, was the so-called Khorasan highway connecting Baghdad with the frontier towns on the Syr Darya and the borders of China. It went from Baghdad to Holwan (the ancient Media) and went on from there to the heights of Hamadan. This was the road which the Persian kings had followed when moving from their winter residence in Babylonia to their summer residence high up in Ecbatana. It went from there to Ray (near modern Teheran) reaching Nishapur, the former residence of the Sassanids.

The couriers of the caliphs rode with their messages as far as Nishapur. From there on the relays were under the protection of the princes of Khorasan. Kudama reports that the princes of Khorasan took good care of the relays of the state post through their territory. Nishapur was an important junction. One road went from there towards the northeast following the river Amu Darya to the east coast of the Aral Sea, another went through Merv, Bokhara, Samarkand, and thence, passing the Syr Darya river, to the borders of China.

A third caravan road led through Sedebestan and Kerman (modern Kirman) to the southern point of the Persian Gulf. From Hamadan (ancient Ecbatana) a side road led to the southeast, to Isfahan, the last post relays in the province Iraq al-Ajami where once Khordadhbeh had functioned as the supreme master of the Arab state post. From Holwan, which lies halfway between Baghdad and Hamadan, a road went through Maragha, Ardabil, as far as Tabriz. A branch from this road led to Derbil in Armenia, and another as far as Derbend on the Caspian Sea. Tabriz, Derbil, and Derbend were the last relays and, at the same time, important points of observation for the Arab intelligence service.

The post road towards the southeast went from Baghdad to Wasit in the region between the Tigris and the Euphrates, where it divided. One branch followed the Euphrates and ended at the port of Abadan. The other branch crossed the Tigris and entered Persia. Istakra and Chiraz were the last post relay stations. From these two cities roads went through Kerman to the delta of the Indus and, on the other side, from Chiraz to the ports of Siraf and Hormuz.

The most frequented road, which was used also by the state post, was the pilgrim road to Mecca.

![]()

213

It started in Baghdad, following the Euphrates, crossing it at Kufa, and soon afterwards entered the desert. The caliphs took good care not only of the relays of the post, but also of the comfort and security of the pilgrims. Numerous caravanserais were erected with wells and reservoirs of water. The Caliph Al-Mahdi (775-785) took special care of this “holy road.” He founded numerous eating houses, opened new wells, erected milestones, and garrisoned soldiers at different places for the protection of the pilgrims.

The central direction of the post in Arabia was at Omra, three days’ ride from Mecca. From Omra the road and the post followed the seacoast, turned to Sana, capital of Yemen, and continued as far as the port of Aden.

The relay road going from Baghdad through Samarra, Tekrif, and Mosul, and continuing to the northern boundary of the caliphate with Byzantium and Armenia, was also important. There were stations very near the boundary because it was very important to obtain as rapidly as possible any information on the situation beyond the frontier.

Perhaps even more important was the road which followed the Euphrates from Baghdad as far as Rakka, whence branches led to the fortifications on the northern frontier. Another important branch from this main road, at Balis on the Euphrates, reached Aleppo, turned towards the south, went through Antioch, Baalbek, Damascus, with a connection with Tiberias, and passed through Syria and Palestine as far as Rafah on the frontier of Egypt.

At the time when Khordadhbeh was writing his book, Egypt was almost independent under the Tulunid dynasty. When it was under the direct rule of the Abbasids their postal organization continued from Rafah to Fustat (modern Cairo) and Alexandria, following generally the old Roman cursus publicus. From Fustat the road traversed the oases of Dakhla and continued to western Sudan. From the coast the road passed through the oases of Kufra, then turned towards Tripoli, eventually reaching Qayrawan, near ancient Carthage, the former capital of the Aghlabids to whom Harun Al-Rashid had given modern north Atrica as vassals. Their territory comprised Tripolitania, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, and was called Maghrib. From Qayrawan the road went on to Tangier on the Atlantic Ocean. This road constituted the only land communication between Spam and the East.

Fortunately, thanks to the Aghlabid dynasty, the post and the roads in the Maghrib were kept in especially good order. The new rulers introduced order in the province and paid special attention to the roads.

![]()

214

They erected guardhouses along the coast for the protection of the post and of commercial communications.

The most common means of transportation on these roads was by camel. In cases of urgency, in particular in 914 when Baghdad tried to expel the usurping Fatimid dynasty in Egypt from that Province, a fast camel-post was created in order to give the capital daily information on the situation. Express messengers on fast camels are said to have been able to cover as much as 180 kilometers in a day.

Ihn Khordadhheh, who gave us a very detailed description of Arab post roads, said that in the whole empire there existed 930 post stations. According to the same author the government set aside 151,101 dinars in its budget for the maintenance of the state post. If these figures are correct, every post station had at its disposal about 166 dinars. Since the pay of an Arab soldier-who was, of course, very well paid — was 100 dinars, this indicates that the salary of the postmasters and their servants could not have been very high and the equipment of the stations must have been rather poor. It is, however, most probable that this information only concerns the province of Iraq including Kufa, administered by Khordadhbeh.

As in the Roman and Byzantine Empires, the state post was designed primarily to transmit only official state correspondence, but, according to al-Mas’udi (Meadows of Gold, VI, 93), private letters were also transmitted in exceptional cases. In Persia the relays provided the messengers with mules and also horses. In Syria and Arabia camels were mostly used. Only official personnel had the right to use the postal service, but private persons were also admitted to its use on the payment of high fees.

The postal headquarters were in Baghdad. In every city with state agencies a subaltern postmaster was appointed, whose duty it was to supervise the relays in his area and to take care that the official documents reached the next postmaster in due time. Others were charged with the care of the animals needed for the transport.

The duties of the postmaster general are described by Kudama in the following way:

The state post has its own Diwan [bureau]. The letters which are sent from the provinces of the Empire have to be transmitted to the superintendent of the Diwan. He has to dispatch them to the places to which they are addressed. He has to present to the caliph the reports of the postmasters and informants, or to prepare excerpts from them.

![]()

215

His duty is also to see that the postmasters and their employees get their salaries. In all relays he appoints the employees through whose hands the packets of correspondence have to be delivered.

Of course, we can hardly compare the roads and relays of the Arab posts with those of the Roman cursus publicus. The roads were not built with such durable materials as were those of tin Romans. Stone was not as easily available in the Arab lands. However, it does not seem that the postal roads were merely wide caravan routes with ill-defined boundaries, for there are passages in the description of the Arab post routes which indicate that they were carefully built of hard material. This material could only be brick. Bricks cannot be compared with the solid stone blocks of the Roman cursus publicus, but they were quite suitable for the Arab horses (which were not shod), for the camels, and also for the foot-soldiers. Of course, they were not suitable for carriage traffic, but the Arabs did not use carriages on their roads. This kind of transportation was only introduced into Asia by the Mongols, successors of the Arabs.

It may be that the relays of the Arab posts were not as well provided as were the relays of the Roman cursus publicus. However, it seems that their installations and provisions were quite adequate. From Kudama’s description of some of the stations, we can conclude that many were like small oases in the desert. He speaks of a building for the postmaster, surrounded by palm trees and water reservoirs; sometimes he mentions another construction for the caravans. The postmaster was responsible for the entertainment of official messengers, functionaries, and envoys; thus it was necessary to him to have rooms available at his station for them to spend the night, and to have supplies for their personal needs. The messengers were not supposed to carry provisions likely to slow them down while travelling, and the stations were generally far away from any villages or cities where provisions could be found. Because of the different climate, the stabling for the horses, mules, and camels would, of course, be more primitive than in the Roman relays. We have also to remember that sometimes small troop contingents used the post routes, thus requiring provisioning at some of the stations.

With regard to the rapidity of the transport it seems that the ordinary traffic travelled at twenty miles a day, and a courier bearing urgent messages could manage forty miles a day, the same speed as the best attained by a Roman cursus velox.

The postmaster general and his officers had other duties besides those of caring for official correspondence and of supervising the stations and their functioning.

![]()

216

The whole postal establishment was subordinated to an espionage system. The postmaster general was, at the same time, the chief of the Arab intelligence service. The geographer Kudama, in his detailed description of the Arab post system, preserved the formula by which a postmaster general was installed in his high function. The caliph stressed that his first duty was to report to the ruler from time to time about the situation in the provinces. With his subordinates he must supervise the activities of the officers charged with the collection of taxes, of the superintendents of state property, of the kadis (judges), and all administrative and political organs. He must also report on the situation of the peasants, on the prospects for the harvest, arid on the political tendencies of other citizens. He must also supervise the minting and circulation of money and be present when the guard of the caliph was being paid. The caliph exhorted the postmaster to accept from his subordinates only true reports, well founded on facts. Then followed in Kudama’s description the enumeration of his duties in the entire administration of the state post; at the end, the caliph asked for separate reports on matters under the surveillance of the postmaster. This meant that the reports were forwarded by the caliph to the relevant diwans (bureaus) of the government.

This shows that the function of the director of the post was extremely important; it is no wonder that he was called the “Eye of the Caliph.” One can also imagine how easy it was for the postal officials to augment their salaries by using threats or promises.

Not even governors of provinces were exempt from surveillance by this intelligence officer. One report addressed to Caliph Al-Mutawakkil concerning Muhammad Ibn Abdallah, governor of Baghdad, is preserved. The postmaster informed the caliph that in his pilgrimage to Mecca the governor had bought for 100,000 dirhem a most beautiful slave girl and brought her to Baghdad. He was so much in love with her that he was spending days and nights in her company neglecting his duties, especially the examination of complaints sent to the caliph. This could provoke a dangerous situation in the capital and the “most devoted servant” implored the chief of the faithful to intervene.

A postmaster from Khorasan under the Caliph Al-Mamun was present at the mosque when the governor, who led the official prayers, omitted to mention the name of the caliph. This generally implied the declaration of a revolt. The postmaster left the mosque immediately, in order to send a special messenger to the caliph with a report of what was taking place.

![]()

217

The governor, however, had observed that the postmaster left the mosque during the prayers and sent his men to arrest him, and the postmaster would have paid with his life for his faithful service if the governor had not been felled by a stroke.

Besides the secret agents of the post system the caliphs had a large contingent of spies and informers at their service. Al-Mansur, the most unscrupulous of the Abbasid rulers, recruited into his espionage system many merchants and humble peddlers who offered their merchandise to many citizens who were ignorant of the real purpose of their visits. He also had in his pay travellers acting as detectives for him. Other caliphs did the same, even Harun Al-Rashid. Al-Mamun is said to have had about 1,700 old women among others in his intelligence service in Baghdad.

These agents were entrusted with the supervision of officials and functionaries in the capital, even of the vizir. They seem to have been subordinated to a special director of intelligence called khaibar, who seems to have been independent of the postmaster general. This function was often entrusted to eunuchs or emirs who enjoyed the special confidence of the caliphs. Even when at war the caliphs took with them their khaibar and his chief agents.

The despotic government of the caliphs naturally needed a well-organized spy and intelligence service in order to preserve its existence and safeguard public order. Although the activity of the intelligence agents may often have been tiresome for the citizens, there are very few complaints about the existence of such a system. The population was used to surveillance and regarded its organizations as a necessary evil.

The Arab police do not seem to have been as inquisitive about the affairs of the citizens as was the intelligence service. The police department (diwan al-shurtah) was, of course, an important section of the government and its head was at the same time commander of the royal bodyguard who was often even appointed vizir. He was responsible for order and public security in the capital and the provinces. He could be described as the chief constable. His powers exceeded those of a kadi (judge) in one way. He could act on mere suspicion and threaten with punishment before any proof of guilt was evident. As a general rule only the lower classes and persons suspected of transgressions came under his direct jurisdiction.

There was a police headquarters in every large city. The head of the municipal police was called muhtasib and was appointed by the caliph, or his vizir, from among citizens of good standing. He held military rank, and besides his police duties also performed those of a magistrate.

![]()

218

He acted as overseer of markets and public morals. Among his duties was that of seeing that the Friday prayers in the mosques were regularly performed; he had authority to admonish those Muslims who avoided the prayer meetings, and to see that the general standards of puhlic morality between the two sexes were maintained.

Otherwise the government left private citizens, and even foreign travellers, generally undisturbed. In the eastern provinces there were, at least in the eighth century, no clerks at the gates of the city to register those who entered or left. A stricter control was exerted in the western provinces. In Egypt, from an early period on, citizens were obliged to he provided with passports. A governor’s order of about 720 forbade anyone to move from one place to another or to embark on a journey, if he was not in possession of this document; otherwise he would be arrested and his vessel confiscated. Under the governorship of the Tulunids in Egypt anyone wishing to leave the country had to ask the police for a passport for himself and even for his slaves. Several types of such passports are preserved in Egyptian papyri. The surveillance of foreign visitors seems, however, to have become stricter with time. Mukaddasi, a geographer from the second half of the tenth century, remarked that the arrival of strangers in the cities was carefully noted and that they could depart only after obtaining a special permit.

Another means of obtaining rapid intelligence was by carrierpigeon post. The Arabs must have developed this kind of letter transport at a rather early date, as it is mentioned in China for the first time about a.d. 700 and could have been introduced there only by Arab or Indian traders. The Romans used carrier pigeons for the communication of news, especially during the siege of cities and in horse races. But the Arabs seem to have discovered the use of carrier pigeons for themselves, as there are numerous indications that the carrier-pigeon post was well developed in the ninth and tenth centuries. It seems that Hamdan Quarmat, the founder of the socalled Quarmatian sect with communistic and revolutionary tendencies, was the first to organize this kind of post on a large and systematic scale. His followers sent messages in this way from all sides to his Babylonian base. During the war with the revolutionary sectarians (927) the future vizir Ihn Mluqlah put a man in Anbar with fifty carrier pigeons, whence intelligence was to be sent to Baghdad at regular intervals, but even this was unsatisfactory. Muqlah therefore established a pigeon-post at Aqarqut with one hundred men and one hundred pigeons ordered to bring him information every hour.

![]()

219

In 940, the secretary of the Caliph Al-Muttaqi (940-944) sent a treasonable message to the caliph’s enemy by carrier pigeon, but the caliph was fortunate enough to intercept the bird. At that time, the cities of Raqqah and Mosul had established a net of carrierpigeon posts, so that they were able to communicate with Baghdad, Wasi, Basra, and Kufa within twenty-four hours. This, and other evidence of the usefulness of carrier pigeons in Arab history were collected by A. Mez in his Renaissance of Islam (pp. 503, 504) from works of contemporary Arab writers. We shall see that this kind of communication was very popular among the Arabs even in later periods from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries.

On the other hand, signalling by fire was not used as frequently by the Arabs as it was by the Byzantines. They seem to have made use of it in former Greek provinces, hut they did not introduce this method in other, former Persian lands. This kind of signalling appears, however, to have been practiced by the able dynasty of the Aghlabids in north Africa. According to the Arab writer Abulmahasin (I, 174, quoted by A. Mez. p. 502), this system worked well on the coast, especially during the ninth century. It was possible to send a message from Ceuta to Alexandria in one night, and in from three to four hours from Tripoli. The signals were sent from towers put up by the Aghlabids and maintained by the Fatimids, their successors. This system ceased in 1048 during the revolt of the Arab West against the Fatimids, and the towers were destroyed by the rebellious Bedouins, according to the Arab historian Marrakeshi (p. 299).

The organization of the state post and of the intelligence service can only be sketched in broad outline because many of the caliphs changed features of them according to their whims, either prolonging the routes or shortening them, and altering the accustomed procedures. The political changes leading to a gradual disintegration of the unity of the Muslim Empire must also be taken into consideration. This began in the provinces on the borders of the empire and became more evident as the decadence of the caliphate became more pronounced. New dynasties arose in several provinces previously administered by emirs or governors appointed by the caliphs. As early as the ninth century the Tulunids governed Egypt almost independently of Baghdad (868-895). All these dynasties recognized the sovereignty of the caliphs of Baghdad, but almost the only symbol of this was the mentioning of their names in the official Friday prayers.

![]()

220

In spite of these defections and troubles the Abbasid Empire still presented a mighty political structure, as is illustrated by the description of the state revenues for the year 919 under the Caliph Al-Muqtadir (908-932). But after his death the degeneration of the caliphate proceeded rapidly. The contest for power in Baghdad by the vizirs, generals, and eunuchs, and the revolt of the heretical Quarmatians reduced the caliph to impotence. At last the powerful Iranian family of the Buwayhids — which had ruled in Persia since 932, although of Shi’ite belief—took the caliphate under its protection. In 945, one of the family of Buwayhids, Mu'izz al-Dawla, was given the new title of supreme commander (Amir al-Umara) and the Buwayhids reigned in the name of the caliphs until 1055. The caliph’s functions became purely honorific. In spite of this degradation the principle of the orthodox Quraysh Imam as the successor of the Prophet and symbol of the Muslim community remained firm. The caliph’s powers were thus reduced to purely “spiritual” ones.

One of the Arab chroniclers seems to indicate that the Buwayhids suppressed the state post in order to isolate the caliph even more, and to hide from him all that was taking place in the provinces. However, this seems improbable. The “protectors” were rather using the organization of the state post and intelligence service for their own purposes instead of leaving them under the control of the caliphs.

The greatest threat to the Baghdad caliphate was the appearance of a new dynasty, that of the Fatimids, first in modern Tunisia and later in Egypt. This dynasty was the more dangerous as its first ruler, Obaydullah Al-Mahdi, head of the Ismaili sect, had proclaimed himself a descendant of Ali and Fatima, Muhammad’s daughter. This gave rise to the name of the dynasty and enabled them to dispute the right of the Abbasids to be caliphs and imams. When, in 909, the founder of the dynasty appeared in what is now modern Tunisia, he claimed to be the only legitimate imam and caliph descending from Ismail, regarded by the defenders of Ali’s legitimacy as the seventh imam in line after Ali. Thanks to the propagandists of the Alidic movement, Obaydullah, with his messianic title Al-Mahdi, found numerous followers. This enabled him, thanks to the Ismailic propagandist al-Shi’i, to get rid of the Aghlabid dynasty and to found a state which became famous in Arab history. He first extended his power over a great part of the Maghrib between Tunisia and Ceuta, and his fourth successor, the Caliph Al-Muizz with his valiant general Jawhar, mastered the valley of the Nile (969) replacing the dynasty of Ikhshidids.

![]()

221

The general founded a new city near ancient Fustat to which the caliph transferred his capital, giving it the name of al-Qahira, which means “The Dominant" and which is the modern Cairo.

Following the example of his pharaonic and ptolemaic predecessors, the caliph sent his lieutenant Jawhar to occupy Palestine and Syria. During the reign of Al-Aziz (975-996) the Fatimid Empire reached its zenith. The caliph’s court was splendid with pomp and ceremony resembling in many ways that of Byzantium. The economic and financial situation permitted him to live in luxury and to build several new mosques, palaces, bridges, and canals. He employed Jewish practitioners as his financial experts and technicians, and was, in general, more tolerant to Jews and Christians than previous caliphs or than his successor Al-Hakim, notorious for his destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Al-Aziz also built a most efficient fleet, which dominated the Mediterranean and encouraged an active maritime trade, not only with the Italian city republics, but also in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. This flourishing condition of the Fatimid state was largely maintained, also during the eleventh century, under the caliphate of Al-Mustansir (1036-1094).

The thriving economic situation of the Fatimid state is illustrated to some extent by documents discovered in the Cairo Geniza, a kind of storehouse connected with an old synagogue in Old Cairo (Fustat) where documents and letters bearing the name of God were deposited. It was a repository of discarded documents, most of them written in Hebrew. This archive contained letters and documents from the period of the Fatimids in the eleventh century to the thirteenth. The records, deriving from all countries of the Mediterranean area, contained important information on the social, economic, religious and even political situation of this period, not only of the Jewish communities in the Muslim Empire, but also of its Arab population. The documents were recently described by S. D. Goitein in his book, A Mediterranean Society. The first volume is devoted to the economic foundations of this society. Thousands of letters are addressed to commercial partners and reveal that commerce and usury flourished in Tunisia and Egypt during the reign of the Fatimid dynasty. The letters were transported by private agencies which employed special messengers for this purpose, the couriers being called fayj. This was a commercial mail service which was, of course, different from the official barid, but was to a certain extent organized on the lines of the state post. The commercial mail service had no relay stations, but the correspondence preserved in the Fustat (Old Cairo)

![]()

222

Geniza reveals that it was well organized, and the names of several “postmasters” in Cairo who employed the messengers and organized quite regular services are mentioned in the letters. The commercial mail couriers utilized the regular caravan traffic and other means of transportation. It was customary for the same messenger to carry the mail the whole way to the city of the addressee, as did the barid messengers. These couriers were mostly Arabs, but Jewish ones are mentioned as being on the routes from Alexandria to Cairo, Egypt to Palestine, and possibly also on the road from Egypt to Tunisia. Special tariffs were introduced for the conveyance of the letters, and weekly services existed between Cairo and Alexandria and even Qus, the main city of Upper Egypt, although the connection with this city was rather slow. River traffic was organized for commercial purposes, and seafaring, favored by the Fatimids, connected Egyptian merchants with Spain, Italy, and the west.

At the end of the eleventh century the decline started, characterized by a dynastic crisis, the loss of the Syrian possessions, the loss of Jerusalem to the Crusaders in 1099, and intrigues provoked by courtesans, and by jealousy among Turkish, Berber, and Sudanese battalions of the palace guard. The caliphs’ power was soon limited to Egypt and, like the caliphs of Baghdad, the rulers of Cairo were reduced to being nominal potentates without authority. It was, therefore, easy for Saladin to reconquer Egypt after the death of the last Fatimid (1174), and to restore it to the nominal authority of the “orthodox” caliph of Baghdad. The success of the Fatimids was due not only to the ability of its caliphs, but also to their excellent intelligence service, They not only took good care of the towers used for fire-signalling, as mentioned above, but also of the state post with its information service in their territories. This is illustrated by the report that, when in 958 the Fatimid army had advanced as far as the Atlantic while conquering Morocco, the commander of the army Jawhar sent a live fish in a glass bottle through the state post to his caliph (A. Mez, p. 501). Moreover, the Fatimids also made use of an extensive net of secret intelligence and propaganda agents called duat who propagated the ideas behind the Fatimid pretensions in almost all regions of the Orient. By exploiting the situation created by the Quarmatians and Ismailis, they proclaimed themselves as imams installed from above and predestined to universal domination and to temporal and spiritual rule. The methods of their propaganda, based on intelligence obtained about the countries they were determined to bring under their domination, has been studied in detail by M. Canard.

![]()

223

In this work he quotes extensively from the writings of the poet Ibn Hani, and the geographer Ibn Haukal, which illustrate how the Fatimid agents prepared the way for the development of the new dynasty, and which points of their propaganda had most moved the Arabs, making them hostile to the Omayyads of Spain, to the Abbasids of Baghdad, and to the Ikhshidids of Egypt. Although their propaganda had some success even in Islamic Spain, it was the Omayyad dynasty in that country that kept the Fatimid at bay by occupying Ceuta.

In the meantime, a new situation was being created in Baghdad by the advent of the Seljuk Turks. About 956, Seljuk, the chieftain of the Turkoman Oghuz moving from the steppes of Turkestan, settled with his people in the region of Bokhara, and accepted the Sunnite “orthodox” Islamic faith. Slowly he extended his power over the neighboring lands. His grandson Tughril penetrated as far as Khorasan, and with his brother he conquered Merv, pushing deeper and deeper into the dominion of the Buwayhids, whose ruling house collapsed. In 1055, Tughril Beg with his Turkomans had reached Baghdad, where he was received by the Caliph Al-Qa’im (1031-1075) as a deliverer, and given the official title al-sultan (he with authority, sultan). After liquidating the short-lived revolt of General al-Basasir, who had embraced the cause of the Fatimids, Tughril initiated a new period in the history of the Baghdad caliphate and of the Muslim world. Fresh tribesmen flocked to his armies and, after recovering Syria from the Fatimids, the newly converted infidels launched into a brilliant conquest of new lands for the Muslim faith. Tughril’s nephew and successor, Alp Arslan (1063-1072) captured the Byzantine part of Armenia and, in 1071, destroyed the Byzantine army at the famous battle of Manzikert, a blow from which Byzantium never recovered. A great part of Asia Minor became the Sultanate of the Rum. Seljuks and the Turkish element slowly began to predominate in this previously Creek land.

The caliphate of Baghdad continued to exist under the protection of the Seljuk Turks. A kind of diarchy existed in Iraq, the caliphs trying to rule in harmony with their protectors, but conflicts were frequent between the two powers. In vain the caliphs tried at times to regain some freedom of action. On the other hand, the Seljuk Empire soon declined like that of the Abbasids. Its unity did not last long. The dynasty of the Alp Arslan was divided into several houses, each reigning over different dominions which soon withered away into a series of local dynasties, the so-called atabegs. They were only nominally vassals of the Great Sultan, but in reality formed a constellation of independent small emirates in Syria and Mesopotamia,

![]()

224

where they came into conflict with the Crusaders, in Armenia, and in other provinces. It can readily be imagined that in such circumstances the organization of the state post and intelligence service would only deteriorate. The new protectors of the caliphs failed to appreciate the importance of such institutions for the interests of the state, and they are said to have stopped the post in about 1063.