VI. Intelligence in the Muscovite State

Russia under Mongol Rule — Political Growth of the Moscow Grand Dukes — Reforms of Ivan III — Introduction of a State Post on Mongol Prototypes; Its Organization — Herberstein and von Staden on the Muscovite Information Service — Ivan IV's Reorganization of the Post Service — Treatment of Foreign Embassies — Opričnina and Secret Police.

After the Russian principalities had been finally conquered, the Mongol khans appointed princes and grand dukes by issuing a special document called jarlyk, which also contained an enumeration of the taxes to be collected from each principality and either sent or brought to the khans. These taxes were computed from the result of the census of the population made by Mongol officers. Both princes and grand dukes frequently made the long and dangerous journey from Batu’s Horde to the Great Khan at Karakorum. Carpini tells us that Michael, Duke of Chernigov, and his companion the boyar Feodor, were put to death by Batu because, for religious reasons, they refused to pay homage to the idol of Jenghiz Khan, their refusal being regarded as a sign of political disloyalty. The incident took place in September 1246 and, since then, both men have been honored as martyrs by the Russian Church.

During Carpini’s stay in Mongolia, Prince Andrew of Chernigov was also slain, and his young brother forced to take the widow as his wife. Even more tragic was the fate of Jaroslav I, Grand Duke of Vladimir (1238-1247) whose duty it was to be present in Karakorum at the election of Güyük as khan. The mother of the khan offered him a drink with her own hand as if to do him honor. He died seven days later in his lodgings. Carp ini says that his body turned bluish-gray in a strange fashion, suggesting that he had been poisoned.

300

![]()

![]()

301

Because of such journeys, the Russian princes and many of their boyars were familiar with the Mongol post service, not only in the Golden Horde, but also on the long road between Sarai, the capital of the Golden Horde, and Karakorum.

The question as to whether the Mongols extended their post and messenger system throughout the conquered Russian lands has not yet been satisfactorily answered. There are many indications that something similar had existed in Russia during the Kievan period. The chronicles often mention the obligation to provide guides, carts, horses, and other commodities to the envoys of the princes. The authorities of the communes were responsible for the supply of these services by the population. I. Ia. Gurl’and, K’voprosu, pp. 23-29, has collected enough evidence from chronicles and other documents to show that the princes sent messengers to the grand duke and to the other princes, and that communications between the capitals of the principalities existed. This, of course, does not mean that there was a regular post system with relay stations.

It is quite probable that the Mongols contented themselves with this kind of communications system, making the princes responsible for its operation for the use of their own envoys and officers. Among the many taxes imposed upon the inhabitants was that of the jam, the Mongol name for postal service. It seems, however, that the money collected was for disbursement to the general post service in Mongol lands. There is no evidence that the Mongols had asked the Russians to maintain a similar system, with relay stations, as in Mongolia.

At the beginning of the Mongol rule over Russia, the taxes were collected by Mongol officials called baskaks, but towards the end of the thirteenth century the grand dukes themselves were commissioned to collect the taxes in their principalities under the supervision of the Mongol commissioners. Later on it became their own responsibility entirely. From then on they not only supervised the conscription of recruits for the khan’s army, but were also responsible for the maintenance of communications between Sarai, capital of the Golden Horde, and the principalities, by providing horses and other commodities for Mongol messengers and officers.

This seems to be an adequate explanation of the problem of the post, because the jam as a tax is mentioned for the first time in a document of Vasilij I dating from the beginning of the fifteenth century.

After liberation from the Mongol yoke, which was facilitated by the slow disintegration of the Golden Horde into several khanates,

![]()

302

the grand dukes of Moscow were able to accelerate the unification of the other Russian principalities with their own. The principle of religious unity of all Russia was of help to them in this task, following the transfer of the Kievan metropolitan dignity to Moscow. The idea of the reunification of the Russian lands led Basil II. Ivan III, Basil III, and Ivan IV into the merciless annexation of independent principalities, into the victorious struggle with Tver’, and with the republics of Novgorod and Pskov.

With the growth of the political power of the Muscovite grand princes, even the Russian political system underwent a slow transformation. The democratic traits of the political system during the Kievan period disappeared during the Mongol occupation; the most remarkable of these were the assemblies of the people (veche) which shared with the princes certain administrative and military powers. But the people lost all their privileges to the princes, thus confirming their power and enabling them to introduce in Moscow, and in the acquired principalities, an autocratic, monarchic régime. The ideological roots of the Muscovite autocracy are Byzantine and were spread by Russian ecclesiastics, but the experiences of the princes with the autocratic and tyrannical Mongol system had furthered the growth of Muscovite autocracy. The autocratic régime needed first of all a good army, and in this respect the Muscovite princes followed the Mongol pattern. The Mongols had allowed them to keep only their retinues, and so the grand princes not only kept their retinues but added to them men bound to military service and called, in Mongol fashion, dvor (court). After their liberation the princes not only continued to keep their military dvor, but they also retained the universal conscription introduced by the Mongols. Their army was divided into five divisions as was the Mongol army, and Mongol military tactics and weapons were also adopted. This reorganization of the Muscovite army according to the Mongol pattern gave the new autocrats considerable military strength, which contemporary Western rulers were unable to match.

Changes in the administration of Muscovy also often followed the Mongol pattern. The grand princes retained the Mongol system of taxation to which the population had become accustomed and which proved highly effective. Justice was administered in the cities by their lieutenants, and in the rural districts by district chiefs appointed by the grand prince, t hey were charged respectively with the general administration of the cities and rural districts. They were permitted to retain part of the court fees and allowed to “feed themselves” off their districts.

![]()

303

Ivan III the Great (A. Thevet, “Cosmographie Universelle,“ Paris, 1575).

![]()

304

Besides administration by state of officials, there also existed in Muscovy a manorial system to which the domains of the grand princes, the boyars, and the Church were subjected.

The creation of military fiefs was initiated by Ivan III, who distributed the conquered territory as an endowment to the members of his dvor, and to boyars who entered his service from other principalities or even from the remaining khanates. The endowments were known as pomestie and the new squires, having no other means of existence, were bound to render faithful and effective military service to the grand prince. Their sons were forced to enter military service at the age of fifteen years, and more land was granted only if the territory given to their fathers was too small for their sustenance. By this system Ivan III not only broke the power of the old nobility in the conquered territories, but also created a most reliable corps bound to support the centralized Muscovite government. This manorial system became the solid basis of the Muscovite military organization during the following three centuries.

In order to enhance their dignity the grand princes introduced a special ceremonial at their court, displayed especially during audiences granted to foreign envoys. It is often believed that this originated from the Byzantine ceremonial introduced into Moscow by Ivan III after his marriage in 1472 to Sophia (Zoë Palaeologus) niece of the last Byzantine emperor. However, the grand princess, who was educated in Rome, could have known very little of Byzantine ceremonial and, after her marriage, exerted little influence on Ivan III. The Muscovite ceremonial, described in detail by Herberstein, and also by a companion of Possevino sent by Gregory XIII to the court of Ivan IV, also called Ivan “the Terrible” (1577), recalls rather Mongol usage in which were traces of both Arab and Byzantine ceremonial. The papal envoys were received by Ivan IV in his summer residence at Staritza on the Volga river.

The new autocratic régime had need of good communications throughout its whole wide territory in order to obtain rapid information on the situation in the conquered lands, and for the expediting of the great prince’s orders to his land representatives. Ivan III understood well this necessity, and he therefore not only used what was left of the old Russian system of mutual communications, but reorganized it according to the Mongol system and extended it throughout his realm. The jam tax, introduced by the Mongols, was also reorganized. Instead of the provision of horses and carts by the people, a tax in money was introduced called jamskija dengi which was to be paid by all those subjected to tax and even by those who were relieved from general taxation.

![]()

305

After the definitive conquest of Novgorod (1478) and the incorporation of the lands of the former republic, “Lord Great Novgorod,” Ivan III saw that Moscow needed a speedy communications service with the annexed city, where the danger of a revolt by the disgruntled citizens who had lost both freedom and high position in the east was great. The only means was the erection of a post with relays well supplied with horses for the messengers to bring information, or to carry orders from their new master. Spaced post stations, or jami, were erected along the whole road. We learn of the existence of such a road from a travel document given hv Ivan III in 1489 to his envoy, Jurig Trachaniot, an educated Greek in Muscovite service, quoted by G. Alef. He was sent with the state secretary, Vasilij Kulesin, to the Emperor Maximilian with instructions to ascertain the conditions under which it woidd be possible to conclude an alliance with the Emperor against Poland-Lithuania. In the document is explained the manner in which both envoys were to travel and how they would be provided “from jam to jam” with horses, wagons (telegas with two horses), and with “korm” or provisions, a carcass of sheep, three hens, and bread being especially mentioned.

In 1485 Ivan III annexed the republic of Tver’, and it was necessary to erect jam stations along the whole route from Tver’ to Moscow. In 1493, in the conflicts with Pskov, the same post system had to be extended to the Pskov frontier. The city was annexed by Basil III in 1510. Pskov and Novgorod also needed to observe the situation in Lithuania and Poland and inform Moscow of events in those countries. About the year 1501, jami were erected along the Možajsk road to the newly-conquered Lithuanian land, first via Kazena, and then as far as Dorogobuž. We learn from a document of 1504 that similar stations were built along the road from Moscow to Kaluga on the middle Oka, and later to Vorotynsk.

From the above-mentioned documents we also learn that the postal roads were placed under the care of overseers. To the envoy Trachaniot, Golochvastow acted as overseer, or pristav, for the route from Moscow to Novgorod; Surmin, another pristav, was responsible for the next stage from Novgorod to Reval.

These roads were most important to Ivan III because of military conflict with Lithuania. But the Mongol khanate of Kazan also required surveillance. Soon after 1490. Ivan erected post stations to Murom, and from there it was easy to reach Nižnij Novgorod by the river Oka.

It is evident that the jam system contributed in great part to the unification of northeastern Russia and facilitated the administration of Muscovite lands.

![]()

306

In his testament of 1504, Ivan III stressed the obligation of his son, Basil III, “to keep jami and carts on the roads in these places where there were jami and wagons during my lifetime.”

The creation of a postal system with relays was a grand achievement. It required planning, erection of relays, often the building of villages for the provisioning of the jami and their personnel with food, fodder, horses, and carts. The larger towns able to provide the necessary equipment for the jami were compensated by the treasury; it was the responsibility of the prince to supply horses by the hundreds for the messenger service. Use was made of the rivers for the messenger service and for the transport of envoys, boats and rowers being provided by the governors. During the winter months sledges were used on the roads instead of telegas.

In the capital special clerks were charged with the formulation of the road documents and to account for the numbers of passengers taking part in official missions. They estimated the number of horses, telegas, and boats necessary for such missions and calculated the quantity of both food and fodder required at each station. With regard to envoys from other nations, the clerks were instructed to observe their eating habits, as no pork could be offered to Mongols, and no alcohol to Muslims. The necessary papers, written in the name of the grand duke, were handed to the overseer, or pristav, who was given precise instructions as to how to guide the missions; he obtained clearances for travel through the provinces, and had the authority to requisition supplementary provisions. These overseers, because they were familiar with the customs of foreign peoples, were sometimes chosen as envoys themselves.

The administration of the post was organized according to the Mongol system; this is documented by the designation in Russian of the functionaries in charge of the upkeep of the post roads. The postmaster was called jamčik; the supervisor of bridges mostovčik; the inspector of the roads dorožnik; and the officer who cared for the river transport lodejščik; his colleague who watched over the beaches and the ports poberežnik. and the master of the post stations jurtči.

The Russians were thus the first European nation to establish a regular postal state service. This was something unheard of in western Europe, where knowledge of Muscovy and its régime was very slight, fortunately, we possess an important historical source on Muscovy of this period, written by Baron Sigismund von Herberstein, who twice went to Moscow as envoy of the Emperors Maximilian and Charles V.

![]()

307

His Herum Muscovitarum Commentarii, first published in Vienna in 1549, was the first description of the new state. It appeared in several editions in Latin, German, and Italian. It was mostly from Herberstein’s description that Western Europe learned the interesting details about Russia and her post installations. Fortunately Herberstein was well prepared for his embassies. He was born in Carinthia, where he was in touch with the Slovene population, a circumstance which facilitated his understanding of Russian. He was well educated at the University of Vienna and had served in the army, but from 1515 on the Emperor Maximilian used his services in diplomacy. His first embassy to Moscow in 1516 was less successful than the second, as Basil III did not accept the emperor’s invitation to enter into peaceful relations with the Polish king. His second embassy to Basil III in 1526 fared better, as he was of help in arranging an armistice between Poland and Muscovy. He stayed in Moscow for seven months during his first embassy, and for nine months the second time. He was both a sharp and intelligent observer, and therefore his account of Muscovite life in the sixteenth century is a masterpiece, full of interesting diplomatic, geographical, political, and folklore descriptions.

When describing the functioning of the Muscovite post, he is well aware that something similar had existed under Imperial Rome, for when speaking of the ducal post stations he makes use of the Latin terms, referring to the ducal messengers as veredarii which means “rapid messenger.” “The duke.” he says, “has postal routes to all parts of his realm, in different places and with a sufficient number of horses. When an official messenger is sent somewhere he obtains a horse immediately without any delay. Moreover, he has the right to choose any horse he wishes.” The stations must have been provided with a great number of horses, for Herberstein confesses that when driving from Novgorod to Moscow the jamčik, or master of the post station, would offer him thirty, forty, and even fifty horses from which to choose, although the envoy and his suite needed only twelve. The animals were changed for fresh ones at any station, or jam and, again, the envoy and his companions were free to make their choice. Both messengers and envoys rode at full speed; should the animals become tired or lame, they were left on the spot and new horses were requisitioned from anyone on the road, or from any settlement. The proprietors of the animals were compensated by the government for their losses. It was the duty of the jamčik to find the abandoned animals and take care of them at this jam.

![]()

308

Thanks to such perfect organization of the Muscovite state post, one of Herberstein’s servants was able to ride to Moscow from Novgorod in seventy-two hours, which meant that he rode an average of 133 miles (214.03 km.) each day for three successive days. Such an achievement was not possible in the lands of contemporary western Europe. There are indications that even greater speed could be achieved along the Muscovite state post in emergencies, as we learn from other descriptions made by envoys and visitors. The adventurer Heinrich von Staden, who offered his services to Ivan IV and who resided in Muscovy between 1560 and 1570, speaks with respect of this organization. “The jami,” he says (p. 59), “are erected at different distances and provided with good horses. It is thus possible to reach any frontier of the state from Moscow in six days.” Von Staden speaks from his own experience. He effected his journey from Dorpat to Moscow (1,400 km.) in six days. In 1476 A. Contarini, a Venetian envoy, took eight days to travel from Novgorod to Moscow, but this was in pre-post days and travel was poorly organized, as can be concluded from his complaint. The introduction of the jam service by Ivan III after his definite conquest of Novgorod made travelling on this road quicker and more comfortable.

Ivan IV continued the building of jami although, as von Staden observes (p. 190), it cost him very large sums of money. The English ambassador, Sir Jerome Horsey (1587), when describing his embassy, speaks with great respect (p. 206) of the achievements of Ivan IV, enumerating his conquests. This ruler, he says, not only founded and endowed more than sixty monasteries, but he built altogether (p. 208) one hundred and fifty-five fortified places in all parts of his realm, well garrisoned with warriors. “He built three hundred towns in vast places and wildernesses, called jami of a distance of a mile or two in length; gave every inhabitant a proportion of land to keep so many speedy horses for his use as occasion requires.” It seems, according to this account, that the inhabitants of the new settlements with relay stations were given parcels of land in order to provide the jami with strong horses and good service. Gurl’and (pp. 176 ff.) calls them slobody.

This interest of Ivan IV in building new postal roads is explained by his policy. He was anxious to intensify commercial relations with England, and the discovery of the White Sea route by the English required the extension of jami in the north to aid English merchants whose wares were welcome in Muscovy, and who extended their commercial activities even to the territory of the khanates of Kazan and Astrakhan subjugated by the Muscovite ruler.

![]()

309

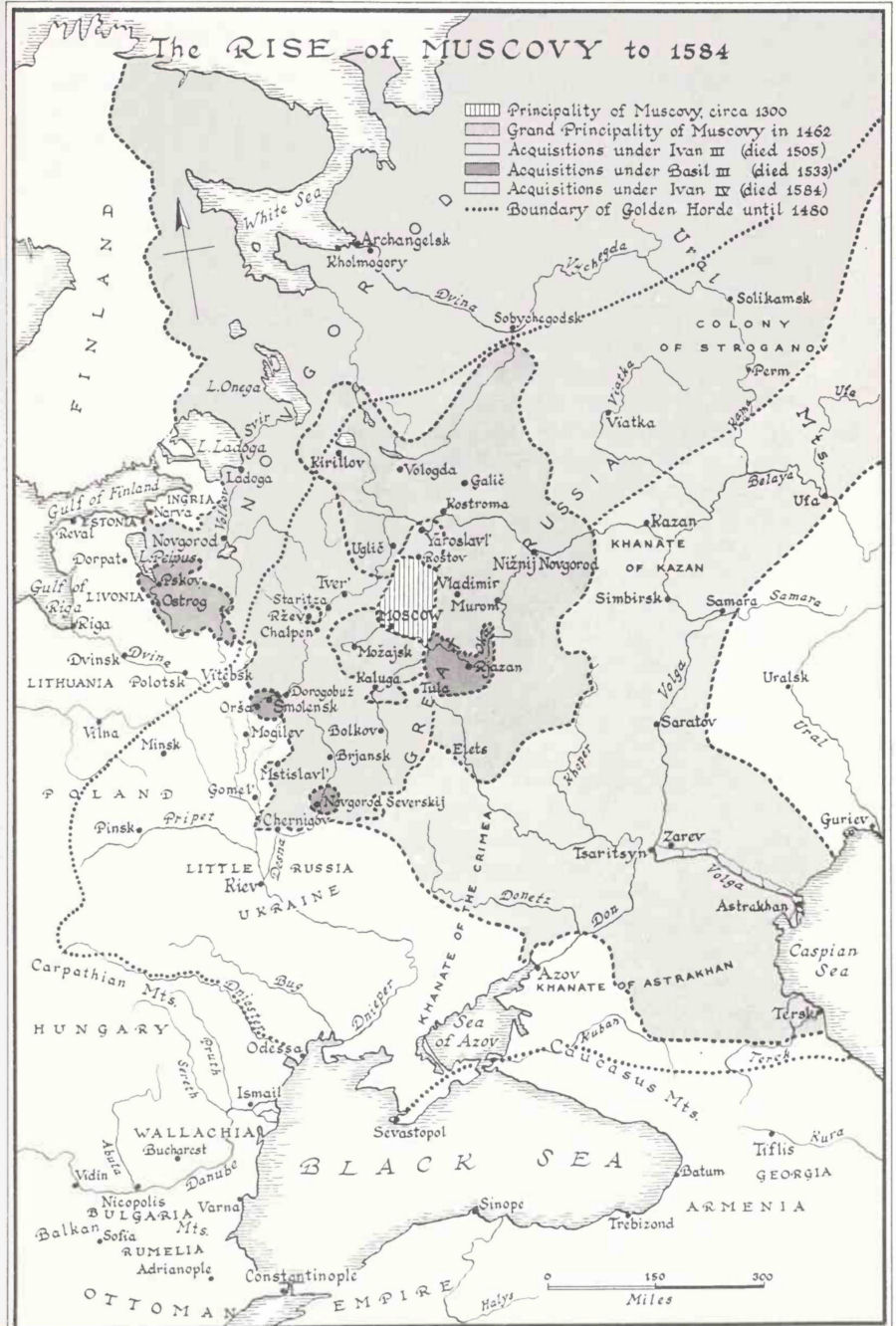

The Rise of Muscovy to 1584

![]()

310

The port of Archangelsk, through which English merchants penetrated into the interior of Muscovy, was open to navigation only during the short summer months; therefore Ivan IV desired to conquer Livonia for its Baltic ports. He prepared his campaign carefully, his first step being to extend the jam service to the frontier of Livonia. The Livonian embassy, which appeared in Moscow in 1554 to plead without result for a prolonged peace treaty, observed these preparations along the route to their capital. They saw newly-built post stations at every four or five miles to which huge stables were attached. Long trains of sledges loaded with materials for war were already moving down the new road.

Further preparations were being made for the attack on Sweden in 1555, the object being to forge a road to Livonia along the Gulf of Finland. Following this Ivan IV began his Baltic campaign in 1558 The Baltic war, however, proved to be very long and onerous, as Ivan IV battled not only the Livonian forces, but the Swedes and Lithuanians as well, both of whom were anxious to keep Muscovy out of the Baltic sea ports. The jam organization proved its usefulness to Ivan IV, as he was able to obtain information almost daily about the situation on the battlefield, and the lively diplomatic activity to which the conflict gave rise required the receipt and despatch of numerous envoys along the new jam post.

The post institution had its center in Moscow and, according to von Staden, it was first called Jamskaja Izba. It was probably Ivan IV who reorganized the center, creating a special ministry of the post called Jamskoj prikaz, for this is the name given to it in documents after 1574. Its activities are now better known through the publication by Russian scholars of works concerning its functions, and of the verstbooks giving the names of stations and the distances from Moscow, together with indication of how many days were needed to reach their destinations. It seems that under Ivan IV the Jamskoj prikaz was in possession of a geographical work describing the roads and giving the distances of the whole state of Muscovy, the original of which is lost. It was compiled not only for the Jamskoj prikaz, but also for the war ministry, or Razrjadnyj prikaz.

The jam roads were also open to use by foreign envoys, as has been already mentioned. Von Staden described in a few words (p. 111) how the envoys of foreign states were greeted at the frontier by many officials and by the people. After a solemn reception they were given into the charge of an official, or pristav, whose duty it was to guide them through the inhabited country to where the grand duke awaited them. This was a precaution to hide from them the direct route and from seeing the poorly populated and waste lands.

![]()

311

They were strictly prevented from seeing strangers, and, should there be other foreign envoys staying at the grand duke’s residence, their presence and their names were kept secret from each other. The grand duke endeavored to obtain information from each of them, but kept them in ignorance of the situation in his own country.

The information given by von Staden is confirmed by Antonio Possevino, who was sent by Pope Gregory XIII to Ivan IV in 1581. In chapter II of his De rebus Moscoviticis Commentarius Possevino criticizes the reports of different envoys who speak of Muscovy as a very populated country, an impression created by the fact that when foreign envoys travelled to Moscow, the people from nearby villages were ordered to line the roads through which they passed.

There are several descriptions given by envoys and foreign merchants explaining how they were treated in Moscow. V. Ključevskij, using mainly the written accounts by S. von Herberstein (1517), Jakob von Ulfeld (1575, 1578), Possevino, Contarini (1473), Olearius (1633), A. von Meyerberg (1661-1663), A. Lyseck (1675), and B. L. F. Tanner (1678), gives a vivid picture of the activities of the envoys in the capital, their receptions by the grand dukes, and the diplomatic transactions with their Muscovite counterparts. The diplomatic receptions in Moscow followed an elaborate ceremonial, and the streets were full of people curious to see the foreigners. Muscovite cavalry in bright uniforms preceded the convoy, and companies of Muscovite streltsy (infantry carrying muskets) formed a guard of honor. The envoys were greeted in the name of the grand duke by the boyars wearing rich and expensive clothes. All this display was designed to impress the visitors with the fitness of the army and with the wealth of the ducal court They were lodged in a special house which, in the sixteenth century, was poorly furnished. Their suite obtained the necessary food, as well as fodder for their animals and wood for their kitchen. However, they were not permitted to go to the bazaar themselves to buy their own provisions.

A new building was erected during the first half of the seventeenth century, replacing the old one which was destroyed by fire. It was nearer to the Kremel (Kremlin), had three floors in a quadrangle. and a very spacious court inside. The tower above the entrance had three balconies from which the envoys enjoyed a beautiful view of the city. The house was richly furnished, and the food for the suites of envoys was prepared in three kitchens. For reasons of security the windows were small, with more iron and stone than glass.

![]()

312

The building must have been of a great size, for in 1678 it accommodated the 1,500 men who accompanied the Polish ambassador. The1 main entrance was firmly shut and well guarded by the streltsy who, sometimes, were also posted at the windows of the whole building in order to prevent any communication with the members of an embassy by curious citizens, or foreigners living in Moscow. Permission to leave the building was granted only for specific reasons, and it was necessary for a pristav to accompany the member of the embassy during his trip, thus “protecting” him from contact with the curious and from any foreigner. No one was permitted to leave the ambassadorial quarters before the envoy was granted his first audience by the grand duke. Any correspondence which the envoys tried to send abroad was censored, its contents copied for the archives, and the letters destroyed. It was exceedingly difficult for foreign merchants, and others, to obtain permission to see the envoys representing their own sovereigns, and the reverse also held true.

These limitations were relaxed to some extent during the second half of the seventeenth century, by which time the Muscovites had become accustomed to the presence of many foreign embassies, but even so the envoys and their suites were kept under discreet but strict surveillance, even when allowed to move about outside freely and admire the city’s monuments.

One can see from these descriptions that the Muscovites treated the envoys in a fashion similar to that of the Byzantines and the Arabs. The principle was to endeavor to obtain as much information as possible from them and, at the same time, prevent them from seeing in Muscovy what the government wished to hide from them. The pristav who accompanied one of the envoys has been very well described by a Dutch ambassador named Brederode who says of him that he is pretending to be a master of ceremonies, but is in reality a spy.

All acts concerning relations with a foreign power and all reports made by the embassies were copied into volumes and kept in the prikaz of the embassies. The first collection of this kind dates from the early years of the reign of Ivan III, which contains documents concerning the relations with Lithuania, the Golden Horde, and the German emperor. Documents about Poland were preserved in a special Panskij prikaz; the treasury (Kazemyj prikaz) dealt mostly with eastern affairs and with embassies. It was not until the seventeenth century that special departments dealing with the affairs of European countries were gradually established.

![]()

313

The Muscovite diplomats often manifested a very astute attitude when dealing with foreign envoys.

Foreign merchants were also under strict control. They were interrogated at the frontier post and their merchandise inspected; if it was found to be welcome in Moscow, they were granted permission to use the jam post. A pristav accompanied them as a guard, thus preventing them from taking a different route and so, perhaps, observing things forbidden to foreigners.

We know little of the activities of the jamtchiks and their subordinates other Than their responsibility of keeping the post organization in good order. But, naturally, the grand dukes expected from them the same services as did the Mongol khans, namely, information as to the attitude of the population, keeping a watchful eye on the functionaries, denouncing any suspect attitude of those in high places, and similar reports. This institution enabled the grand dukes to keep the boyars under surveillance, and to command respect for the authority they wielded over the principalities annexed by Muscovy.

We do not find any information about the creation of a secret police to maintain order in the interior before the reign of Ivan IV. This supreme power over all subjects surprised Herberstein, as no western ruler would even dream of such an autocratic development. The Englishman Giles Fletcher, who visited Muscovy seventy years after Herberstein, called this power quite simply tyrannical. This development was due to the new concept of society and its relation to the state which was slowly introduced into Muscovy with the growth and spread of monarchic and autocratic ideas. All classes of the nation were bound to the service of the state. The former appanage of princes and boyars lost their privileges and became servants of the tsar. Attempts to resist this new régime were particularly extreme under Ivan IV, but he smashed this opposition with a violent blow directed against the princes and the old boyar families, by creating a new class of the opričniki, men who were wholly devoted to the tsar and chosen by him (1565). The opričniki, selected from among the dvorjane and the petty nobility, were settled on the hereditary lands of the old boyar families in the central part of Muscovy. The former owners were, in part, mercilessly exterminated and, in part, resettled in newly annexed territories on the borders of the state. This oppressive measure required the creation of a body of special guards, or political police at court, to combat attempts at treason.

![]()

314

A reign of terror was thus introduced by these brutal changes which lasted for twenty years. In this way the scheme of secret police was introduced into Muscovy which continued to function in various ways under the reign of the tsars.

As we have already said, the Russians were the first nation in Europe to have introduced a well-organized postal service in their state. However, it should be stressed that their postal system was not entirely an imitation of the Mongol practice. Ivan III built his postal system on the basis already formed by the Russian princes of the Kievan period. There appears to be an analogy between the Kievan practice and the communication system which existed in China during its feudal period, as described before in Chapter V. If the Mongols had contented themselves with the Kievan system of communications between the principalities, as seems most probable, then we have to assume that it was quite advanced. If the Mongols had not disrupted the development of Russia so thoroughly and for such a long period, we could assume that the Kievan communication system would have developed into something similar to that which the Mongols had implanted in their empire.

Imitation of the Mongol system accelerated this development, and it is the great merit of Ivan III to have seen its advantages and to have made use of the centuries-old experiences which other eastern nations had accumulated, and which the Mongols had inherited. It was also Ivan III who recognized the importance of a good intelligence service for the purposes of a centralized government — again the first European ruler to exhibit such wisdom and statecraft. Fortunately, the reign of this able ruler is now more appreciated by historians. J. L. I. Fennell, in his book Ivan the Great of Moscow, has described the statesmanship of Ivan III to western scholars. This ruler deserves more attention also for his achievements in the economic and material advancement of his nation. He laid the foundations for the expansion and grandeur of Russia and therefore he fully deserves the title, Ivan III the Great.

CHAPTER VI: BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adelung, Friedrich v., Kritisch-literärische Übersicht der Reisenden in Russland bis 1700, 2 vols. (Amsterdam, 1960: ist ed., St. Petersburg, 1846).

Alef, G., “The Origin and Early Development of the Muscovite Postal Service,“ Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, N.F. 15 (1967), 1-15.

![]()

315

Ammann, A. M., ''Ein russischer Reisebericht aus dem Jahre 1581,”

Ostkirchliche Studien, 10 (1961), 156-195; 283-300 (Possevino’s embassy).

Bond, E. A., Russia at the Close of the Sixteenth Century. The Hakluyt Society, First series, no. XX (1856); treatise by Giles Fletcher; travels of Sir Jerome Horsey.

Bruckner, A., “Russisches Postwesen im 17. und 18 Jahrhundert,” Zeitschrift für allgemeine Geschichte, vol. 12 (1884). German excerpt from J. P. Chruščova, K istorii russkich post, II (St. Petersburg, 1884).

Garpini, Johannes del Piano (de Piano Carpine), Sinica Franciscana, I, 27-130 (Quarrachi, 1927-42).

Contarini, A., Travels to Tana and Persia by /. Barbara and A. Contarini, ed. by W. Thomas and S. A. Roy, The Hakluyt Society, First series, no. XLIX (New York, 1873), 106-171.

Delius, Walter. Antonio Possevino, S.J., und Ivan Grosnyj, Beiheft zum Jahrbuch “Kirche in Osten,” Band III (Stuttgart, 1962).

Dvornik, F., “Byzantine Muscovite Autocracy and the Church,” Rediscovering Eastern Christendom, ed. by A. H. Armstrong and E. J. B. Fry (London, 1963), 106-119.

_____, “Byzantine Political Ideas in Kievan Russia,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 9-10 (1956), 73-121.

_____, The Slavs in European History and Civilization (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 1962), Russia: 212-232, 259-283, 362-389, 466-557.

Fennell, J. L. I., Ivan the Great of Moscow (London, New York, 1962).

Fletcher, Giles, see E. A. Bond.

Grey, Ian, Ivan III and the Unification of Russia (London. 1964).

Gnrl’and, I. Ia., K'voprosu ob’ istočnike i vremeni proischoždenija jamskoi gońby v’ drevnej Rusi (Jaroslavl', 1900).

_____, Jamskaja gońba v Moskovskom gosudarstve do konca XVII veka (Jaroslavl', 1900).

Hellmann, M., Ivan IV der Schreckliche (Göttingen, 1966).

Herberstein, Baron S. v., Rerum Moscovitarum Commentarii (Basel, 1571); English transl. by R. H. Major, “Notes upon Russia,” The Hakluyt Society, First series, no. XII (1852); reprint, 2 vols. (New York, 1965).

Horsey, Sir Jerome, see E. A. Bond.

Jenkinson, Anthony, Early voyages and travels to Russia and Persia, 2 vols., The Hakluyt Society; I, 72-73 (London, 1886).

Ključevskij, V., Skazanija inostrantsev’ o moskovskom gosudarstvje (Report made by foreigners on the State of Moscow) (Moscow, 1916).

Noerretranders, B., The Shaping of Czardom under Ivan Grozny) (Copenhagen, 1964).

Olearius, G. (1672-1715), English ed. by John Davies (London, 1666-69).

Possevino, A., De rebus Moscoviticis Commentarius (Anvers, 1587).

![]()

316

Staden, Heinrich v., Aufzeichnungen über den Moskauer Staat (Hamburg, 1964; 2nd ed. by F. T. Epstein).

Vernadsky, G., A History of Russia (London, Oxford, 1943-1959), 5 vols.; vol. 3, The Mongols and Russia; vol. 4, Russia at the Dawn of the Modern Age; vol. 5, The Tsardom of Moscow, 1547-1682.

Wipper, R., Ivan Grozny, transl. by J. Fineberg (Moscow, 1947).

Zimin, A. A., Opričnina Ivana Groznogo (Moscow, 1964).

_____, Reformy Ivana Groznogo (Moscow, 1960).