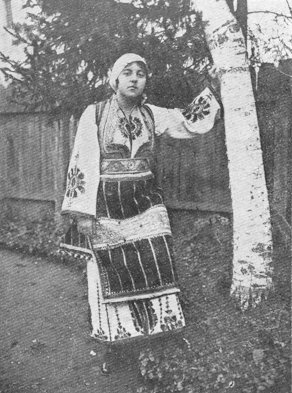

Macedonian refugee women who have attended a congress in Sofia to appeal to the League of Nations to intervene in behalf of their oppressed fatherland

CHAPTER IV

The molding of the Bulgarian nation

B.

Due to the fear which some of the great powers — chiefly England — felt because of Russia's success, as well as to the extreme dissatisfaction of the little Balkan states at the creation of a huge Bulgaria, which they asserted included lands belonging to them, the whole map of the Balkans was redrawn. The big, free Bulgaria was deprived of her liberty and cut into five sections, one of which was given to Serbia on the west, and another to Rumania on the northeast, while a third large district comprising the whole of Macedonia was given back unreservedly to Turkey and a fourth, southeast Bulgaria, was placed under Turkish supervision and control. The fifth part, which might be called Bulgaria proper, though it was certainly no more Bulgarian than most of the other districts, was left as an autonomous principality under Turkish suzerainty. Bulgaria had been reduced from the 100,000 square miles to 37,200.

This mutilation of the nation and the thrusting back under the abominable rule of the Turks of hundreds of thousands of Bulgarians caused the bitterest disappointment and resentment throughout the whole country and imposed upon the new state the supreme task of continuing to work for the freeing of all the 'Bulgarians and the unifying of them in a single independent kingdom. At that moment, according to Bulgarian statistics, there were 2,007,919 Bulgarians in the principality, 942,680 in Eastern Rumelia, the autonomous district left under Turkish supervision, 1,500,000 in Macedonia and Thrace, 200,000 in Serbia and 200,000 in Rumania. These latter did not constitute a burning political problem but the rest did. The determination of the freed Bulgarians to liberate and gather into a united, independent state their fellow countrymen separated from them by artificial boundaries has been the motive which has inspired and directed the whole of Bulgaria's foreign policy from that day until the present time.

The first step toward the realization of this national ideal was taken in 1885 when Eastern Rumelia revolted and declared itself annexed to the Bulgarian kingdom. This of course did not pass without international repercussions and Serbia, instigated by Austria, attacked Bulgaria to secure compensation for her neighbor's increase in size and strength. Turkey also would have attacked if England had not intervened at Constantinople and in consequence the new state with no army officers higher than a captain would probably have been overwhelmed. But freed from danger on the east Bulgaria very soon thrust back the Serbian invaders and would certainly have annexed territory given to Serbia by the Berlin congress had it not been for Austrian intervention. As a result of this revolution and war the Bulgarian principality absorbed a whole new province and recovered 942,680 people as well as increasing its prestige and greatly strengthening its self confidence.

Macedonia, however, was still unredeemed, so Bulgaria set about to prepare for the redemption of that Bulgarian land also. The realization of this liberating ideal constituted one of the chief motives stimulating the country toward the very rapid progress it made during the following quarter of a century. Naturally the Bulgarians in the newly created principality, rejoicing in independence and proud of having a state of their own after centuries of subjugation, were also attached to progress for its own sake and were eager to make up for lost time. They were determined to show their mettle by rapidly gaining a worthy place among the advanced nations of Europe. Yet behind the construction of railroads and roads, the improvement of agricultural methods, the opening up of a large number of schools, the creation of a press, literature, art, drama, and history, the elevation of the church, the formation of a strong, well governed state and the training and equipping of the best army in the Balkans was the conviction that the nation must move forward to a position where it would be able to fulfill its national mission, namely the freeing of all the Bulgarians and the uniting of them in a single, self-governing kingdom.

Macedonian refugee women who have attended a congress

in Sofia to appeal to the League of Nations to intervene in behalf of their

oppressed fatherland

Half a dozen appealing "Macedonian Problems". When well

fed and pleasantly situated diploma's sign treaties and agreements in European

capitals such mothers and their babies have to leave their firesides and

cradles and flee destitute across Balkan boundaries. It is estimated that

there are half a million refugees in Bulgaria

One of the chief considerations which moved the Bulgarians to prepare so feverishly for combat was the very evident fact that the liquidation of European Turkey was imminent. Every capable and well informed observer saw that something was going to happen in the Balkans. Certain terrific forces were pushing events toward an irresistible issue. A nationalistic tide was rising which was absolutely certain to overflow. For a century the nations in southeast Europe had been moving toward self-realization and aggressive self-assertion and after the beginning of the twentieth century this tendency was much accentuated. On the other hand, Turkey was considered by everyone to be the "sick one of Europe" and every year seemed to aggravate her disease. There was no reason why Turkey should remain in the Balkans. From every point of view she was out of place there. She was an invader and her Christian neighbors were determined to compel her to give up the land she had snatched more than half a millennium earlier and which she had filled with misery, ignorance, corruption and fear. The cordon of steel that Turkey still maintained about the last remnant of her European domain was soon to be brushed away as a rope of paper. So, naturally, every Balkan state was crouching, ready to spring upon the treasures destined to be left without an owner, especially since these countries considered those treasures their rightful possessions.

The Balkans at the beginning of the present century made one think of a prospective gold rush. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they resembled communities living on the edge of a large tract of very desirable public land that was about to be opened up and given to whomsoever managed to put their stakes down first. The only uncertainty was the date of the rush. The Balkan states adjoining European Turkey on the north, west and south bent all their energies to prepare for the great day and even took measures to hasten it, each believing that it had special claims on the territory toward which it was directing its attention and bayonets.

What were these claims? What was European Turkey and who lived in it? It was a pear shaped territory larger than any of the countries bounding it — Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro in the north and Greece on the south — extending from the Adriatic Sea on the west, clear across the Balkan Peninsula to Constantinople on the east. It was washed by four seas, contained much excellent land and was inhabited by such an intermixture of races that the French call one of their most mixed dishes' a "salade Macedoine". At the beginning of the present century it had a population of 6,000,000 people who were chiefly Albanians, Slavs, Greeks and Turks. It was divided roughly into three areas: in the western or larger extremity was Albania, after which came Macedonia bounded on the east by a narrow strip of land known as Thrace. On the lower part of the southern end also were Thessaly and Epirus. The Albanians maintained that their country and their people occupied a very large proportion of European Turkey; the Greeks asserted that most of the inhabitants of Albania, Macedonia, and Thrace were Greeks; Bulgaria declared that most of the area was populated predominantly by Slavs who were in every respect pure Bulgarians. The Serbs also presented certain rather belated claims and backed them with the prevailing Balkan methods. Thus it was plain that the Balkans were facing a double bloody operation: first the expulsion of the Turks who were no more inclined to evacuate that part of their empire, which was inhabited by two million Turks, than Great Britain would have been to relinquish Wales or America to give up Florida, and secondly the apportionment of the area among the Balkan peoples.

It must also be pointed out that the inhabitants of Macedonia did not

sit quietly as passive spectators watching the development of this terrific

drama.- They themselves became actors and attempted to determine the course

of events by maintaining schools, arousing the consciousness of the people

and forming revolutionary societies, the largest and strongest of which

was the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization which actually launched

two extensive uprisings in 1903. This conspiratory association was essentially

Bulgarian and was in conflict not only with the Turkish oppressors but

also with bands of Greek and Serbian revolutionists. There ensued years

of terror and confusion in Macedonia, marked with pillage and murder and

futile though heroic attempts on the part of subjugated people to gain

independence. The furious struggle was made still more savage by conflicting

states seeking territory and aggrandizement.

|

|

Into the merits of this struggle I shall not enter nor shall I attempt any objective study of "The Macedonian Question". It is a very complicated and serious problem, which still jeopardizes European peace and deserves the attention of all persons interested in international affairs. But it itself would require a separate book so cannot be adequately treated here. it will suffice merely to say that the Bulgarians estimate that in 1912 there were 1,200,000 Bulgarians in Macedonia, comprising 52% of the population. They considered that the Macedonian towns of Prilep, Bitolya and Shtip are as purely Bulgarian centers as are Sofia, Philippopolis and Tirnovo. They looked upon the revolutionists fighting for Macedonian liberation with much the same admiration as that which they cherished for their liberating heroes, Levsky and Boteff, with the same admiration indeed which the Americans feel for their revolutionary leaders, who revolted against England and which the Italians cherish for Garibaldi.

The Bulgarians' conviction that the Macedonians form an integral part of their nation is substantiated by the testimony of a large number of informed and disinterested foreigners, by the language of the Macedonians, their cultural affiliations, their national allegiance, their songs, customs, architecture, monuments and place names and even by the formerly published opinions of prominent Serbian scholars. There are, of course, many sides to every complicated question and the Serbians have arguments, especially of a historical nature, with which to support their claims, but that does not alter the fact that the Bulgarians in most complete unanimity consider Macedonia as much a Bulgarian land as the Germans consider a German land the Rhine area which they recently took over from the French after a decade of foreign domination.

It is for that reason that the Bulgarian nation prepared with such energy, exaltation and confidence for the grand struggle which was to result in the liberation of their "brothers in Macedonia". One of the most important steps toward this crusade was the ret of September 22, 1908, by which the Bulgarian Principality was declared free from Turkish suzerainty and transformed into an independent Kingdom. Ferdinand, the ruler, was no longer a prince but a Tsar, the head of a sovereign state, capable of treating with its former master on equal terms. This was of course a revolutionary act, which under normal circumstances might have provoked serious international repercussions, but it synchronized with other important diplomatic steps taken by other European powers so that Turkey was not able to resist. Thus within 23 years Bulgaria had succeeded in inflicting two humiliations upon the Turkish Empire; one was the annexation of Eastern Rumelia, which had been under Turkish sovereignty, and the other was the conversion of the principality which was under Turkish suzerainty into a kingdom. The third and greatest revolutionary act remained; the driving of Turkey out of Macedonia, which formed an integral part of the Sultans' Empire.

And for that step Bulgaria prepared by forming a military alliance with Serbia and Greece. The terms of this agreement were vague but between Bulgaria and Serbia was signed a pact providing that all of eastern and central Macedonia, should go indisputably to Bulgaria, that a small district in northwestern European Turkey should go to Serbia and that the fate of the rest of Macedonia, in case of dispute, should be decided by the Russian Emperor. Greece signed no such definite agreement but trusted to her noted diplomatic agility to bring her a suitable share of territory when the final moment for the partition arrived. The military stipulations were a little more definite.

The necessary Turkish atrocities were precipitated in Macedonia in the late summer of 1912, to serve as a pretext for armed intervention on the part of the Balkan allies and after a brief exchange of notes the long awaited war, without the decency of a formal declaration, was launched by the Montenegran army, which began an attack on Turkish forces in August of that year. Determined not to let any member of the alliance gain an undue advantage, the other Balkan states rushed into the fray and a modern war on a large scale began, in which Turkey was attacked from three sides. The heaviest risks were taken by Bulgaria who also had to do the hardest fighting, but her army advanced with remarkable rapidity, winning one crushing victory after another. The Serbs, meeting smaller enemy forces, also reached their goal quickly and successfully so that within four weeks the Turkish armies were practically wiped out and the Balkans largely freed from Moslem tyrants. Up to that point military operations had been carried on with boundless enthusiasm and complete unity and if Bulgaria had made peace immediately she would certainly have gone a long way toward realizing her national ideals.

If Bulgaria had! But what monarch or general can stop in the moment

of victory? And besides, how could four ambitious and suspicious allies

agree to cease operations when all seemed to be in a position to make further

conquests? The Bulgarians hoped to take the important fort of Adrianople,

and some even dreamed of pressing on to Constantinople, while the Greeks

were determined to take several strong military centers still occupied

by the Turkish army. Consequently they kept on fighting until December,

when-an armistice was signed 'and representatives of the victorious Christian

powers and of the Turks met at London to draw up a peace treaty. Because

of the many conflicting interests and ambitions, negotiations went very

slowly and ended futilely for, when an agreement was finally reached January

22, a revolution broke out in the Turkish capital and the new self-appointed

government of young Turks repudiated the peace, renewing operations. As

a result of this new chapter in the war the Bulgarians, with some Serbian

aid, captured Adrianople and forced the Turks once more to begin peace

negotiations with the victorious allied powers.

|

|

| How would you like to have a rendevous here?

|

Another Macedonian woman whose fatherland the peace treaties cut into three parts, lying in three different states |

But by this time the allies had begun quarrelling and in more than one place had actually engaged in bloody skirmishes with one another. The Serbs had decided not to observe their treaty regarding the division of Macedonia and demanded, in consequence of what they considered changed circumstances, that the Russian Emperor apportion between Bulgaria and Serbia not only the so-called disputed zone, as the terms of the treaty provided, but the whole of Macedonia. The Bulgarian nation, army and government were opposed to this and in an atmosphere of extreme confusion when wild passions were raging in all the Balkan capitals and the allies were moving with terrifying rapidity toward a fratricidal war, the Bulgarian army, authorized undoubtedly by the Bulgarian King, Ferdinand, forestalled the conciliatory steps the Sofia government was inclined to make, by attacking without warning the Serbian army in Macedonia on the night of the 29th of June. This took the Bulgarian government completely by surprise but upon learning of the attack it ordered the Bulgarian army to stop military operations at once and called upon the Russian .Emperor to intervene and arbitrate. However, it was too late. Greece and Serbia had prepared for this very act and finding themselves in possession of the best possible justification for war, assumed the offensive and attacked the Bulgarian forces all along the line.

The Turks also attacked from the southeast while the Rumanians invaded the northern part of the country, so the Bulgarians capitulated in order to avert a worse calamity. Peace was made at Bucharest and according to the terms of the treaty Bulgaria gained some territory in the south and acquired a small portion of Macedonia, but at the same time lost to Rumania part of her original territory, a district in the northern corner of the country, known as southern Dobrudja, inhabited largely by Bulgarians and Turks and comprising 2960 square miles. Thus Bulgaria gained 8918 square miles of new land and lost 2960 of old; she acquired a new Bulgarian population of 400,000 persons and lost a Bulgarian population of 170,000. From the economic point of view the game was certainly not worth the candle, while from the nationalistic point of view the outcome of the great venture was a terrible catastrophe. The war had been for Macedonia, for the liberation of the Bulgarians in Macedonia, but there Bulgaria had failed. Of Macedonia, Bulgaria received 3100 square miles, or 10 %, Greece 15400 square miles, or 46 %, and Serbia 15000 square miles, or 44 %. 180,000 inhabitants, or 8 % of the total population went to Bulgaria, 1,000,000 inhabitants, or 42 % of all went to Greece, and 1,200,000, or 50 % to Serbia. The Bulgarians estimate that 700,000 Bulgarians were placed under Serbian domination and 250,000 under that of the Greeks. Thousands of Macedonians fled in terror from the lands occupied by Greece and Serbia and Bulgaria was filled with destitute refugees.

It was a moment of overwhelming disappointment for Bulgaria. Her national unification for the accomplishment of which she had not only made feverish preparation during the three decades of her independent existence but for which she had plunged into a dangerous and exhausting war against a powerful empire had been, in the opinion of the whole nation utterly frustrated. Most of Macedonia seemed to them still in bondage. The great moment of the liquidation of Turkey had come and Bulgaria, who had planned to make good her claims to most of the freed territory, had been left with what seemed to her almost nothing. But the nation was weary and profoundly disappointed in its leaders who had so completely failed to take advantage of a very favorable situation, so when King '^Ferdinand called upon his people to preserve their battle flags for a better day his words found no response. The peasant soldiers returned to their neglected fields with bitter hearts and endeavored once more to set in motion the wheels of progress which had been stopped by the war. A nation which loves its plow much more than its sword hoped that it might never again see its countless yokes of gentle, grey oxen pull creaking farm wagons off to distant battle fields. It reopened schools, repaired dilapidated irrigation wheels and singing its sad, old songs once more began to make good things grow.

But the nation's leaders did not fail to keep the battle flags dusted and bright for another unfurling. And the day for that came sooner than they had dared anticipate. The shots with which the Serbian youth killed the Austrian Crown Prince and his wife at Sarajevo, thus precipitating a world war, again opened up the Balkan question and gave the Bulgarian people another chance to "free Macedonia", so on the first of October 1915, at the end of a long period of hesitation and fourteen and a half months after the beginning of the German invasion of Belgium, Bulgaria as an ally of the Central Powers began military operations against Serbia.

It is certain that the Bulgarian nation was not eager to go to war at all and especially not on the side of Germany and Turkey. Its sympathies, as far as it had any general interest in the war, were with Russia and England, because Russia was responsible for Bulgaria's liberation while many English and Americans had aided the country in moments of need. But the one consideration which determined the attitude of the Sofia government was the fate of Macedonia. Events were developing in such a way that sooner or later Bulgaria would probably have been compelled to relinquish her neutrality and take sides with one of the two warring groups and she was resolved to throw in her lot with those who promised her Macedonia. Because of the intransigence of Serbia, who was as determined to retain Macedonia as Bulgaria was to acquire it, the Entente was not in a position to give Bulgaria any assurances. Germany on the other hand, being at war with Serbia was not averse to paying allies with Serbian territories and so promised to give Bulgaria everything she wanted. In addition, the Bulgarian king was of German origin and at the time an anti-Russian government was in power in Bulgaria.

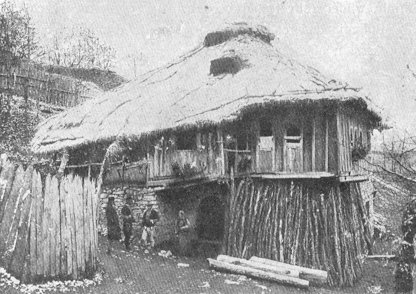

A primitive Macedonian house

So, taking advantage of what he and his advisers considered a favorable moment, as far as the development of military operations were concerned, Ferdinand issued a proclamation, stating that the world conflict was drawing to a close and calling upon his people again to take up arms in order to fulfill their national mission and liberate their brothers. Several political leaders had carried on a very vigorous opposition against this turn of events and done everything in their power to prevent it, some of them even going to jail. At the time of mobilization also there was a great deal of apprehension on the part of the government as to whether or not the nation would respond to the call to arms and there were many serious cases of insubordination. But in spite of their revulsion against another bath of blood and their extreme reluctance to point their guns at Russia and the democratic nations of the western world, the Bulgarian masses, in order to "free Macedonia", appeared at their places under the old flags of battle and attacked Serbia all along the line. Since a large part of the army of that valiant little state was engaged on the Austrian front, the Bulgarian soldiers gained a swift and comparatively easy victory and within a few weeks the Germans and Bulgarians crushing all opposition drove the Serbian soldiers, accompanied by a large civilian population, across Albania in a terrible winter retreat and occupied the whole of the country.

Bulgaria had realized her long cherished ambition and was in possession of the whole of Macedonia. A year later Rumania entered the war and Bulgaria, 1 lunching a vigorous and very successful campaign on the northern front, drove the Rumanians and Russians back and occupied the whole of the Dobrudja. For the moment she had more than realized her national idea and controlled a territory much larger than she had received at the signing of the treaty of San Stefano. Elated by this victory certain imperialistic elements in the country aspired to unmeasured conquest and shamefully boasted that no land would be given up where a Bulgarian foot had trod, that the Central Powers and the Greater Bulgaria would become contiguous and that Serbia even would not be allowed to survive as an independent state. So quickly is liberating ardor transformed into imperialistic passion! The nation, as a whole, however, felt no such elation, no such hunger for conquest. They were not vitally interested in the terrific duel between the two powerful groups of great states and suspected that they were being used to serve the ends of other nations. They were also very apprehensive as to the final outcome.

Events proved the correctness of this feeling. Kept in the war two years after they had reached their objectives, the Bulgarian people, in the army and out, after being weakened by hunger and privations, began to lose their power of resistance and when they heard of Wilson's fourteen points considered that all reasons for further fighting were over. These points were based on the principle of national self-determination and one of them specifically provided that the Balkan peoples were to be permitted to determine their own national allegiance. Since the Bulgarian soldiers were confident that the Macedonians would decide to reject Serbian sovereignty and would declare in favor of affiliation with or annexation to Bulgaria, they considered their one great problem solved and their ideal achieved so they refused to fight any longer. The southern front was broken, the Bulgarian army dispersed or captured and a separate armistice signed.

The photographer forgot to say, "Now everybody smile!"

Bulgarians from Thrace, another lost territory

This was seven weeks before the collapse of Germany and the general armistice. The Bulgarians returned home embittered and demoralized but they still dared hope that at the peace conference which was later held at Neuilly near Paris the new Balkan, map would be drawn on the basis of nationality and that Bulgarian lands would not be placed under the domination of foreign states. However, when the peace treaty was finally completed in 1919 and the Bulgarians were called to sign on the dotted line they were again faced with a crushing disappointment. Not only was an additional part of Macedonia given to Serbia or Jugoslavia but sections of Bulgarian territory along her western boundary 600 sq. miles in extent were also taken away and given to Serbia, while the whole of Dobrudja was returned to Rumania, and other large areas were given to Greece. To be sure, it might have been worse. Germany, Hungary, and Austria had all lost proportionately more; had been punished more drastically. But the Bulgarians asserted that much of the land the other states lost were inhabited by foreign nationalities while Bulgaria was deprived of her own territories. One sixth of the whole nation, they stated, was cut off from the motherland.

Their sacrifices had proved to be in vain. Their hopes were blasted and their dearest dreams of half a century mocked. Weakened, defeated, impoverished and disorganized, they had to begin their struggle for progress all over again, but not with the ardor and hope of a half a century earlier. Closely pressed by enlarged and victory flushed neighbors, deprived of every means of defence in the midst of heavily armed powers, saddled with reparations and placed literally under the tutelage of foreign states, the Bulgarians felt almost as though they had entered another period of bondage.

Their king, Ferdinand, who was considered to be responsible for two

catastrophes, was compelled to flee and his son, Boris, without any disturbance,

ascended the throne in his place. A very turbulent period of political

turmoil and confusion ensued during which a revolutionary Communist Party

and a self-confessed, semi-revolutionary Agrarian Party dominated political

life until both were violently crushed by the conventional "law and order"

elements that by 1923 had again recovered sufficiently to direct the affairs

of state. Now a decade after the close of the war Bulgaria is recovering

her confidence and spirit, her national pride and her ambition to attain

a worthy place among the nations. She in devoting most of her attention

to cultural and economic advance and to political consolidation; is seeking

to unite the people within her bounds in ardent and constructive patriotism;

is trying to remake her public institutions so that they will be better

adapted to further the welfare and progress of all the people and is endeavoring

to find friends and well wishers in the outside world. Her youth seem to

be no less inspired by national ideals than were their fathers, who so

completely failed in realizing them, and the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization

still exists and very vigorously operates with the unabated hope of "freeing

Macedonia".

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]