Generations come and go but the wooden plow remains. There are still 450,000 of them in Bulgaria

CHAPTER IV

The molding of the Bulgarian nation

A.

The Balkan Peninsula is a highway along which Europe and Asia have often marched pursuing each other and over which Civilization and Barbarism have frequently advanced and retreated. It has always been a thoroughfare. Never yet has there been a conqueror powerful enough to set up a sign, "No trespassers allowed here". Never has there been a single racial group strong enough permanently to dominate the entire Balkans. The Italian Peninsula belongs to a single nation while the Iberian is the possession of the Spaniards and their first cousins, but six people still struggle with one another for fields and firesides in the Balkans, while nearly as many Great Powers, after a long series of wars over the Balkans, are preparing for another European conflict for the sake of domination there.

Few are the areas on the surface of the earth over which so many foaming horses have tramped, carrying plumed warriors with flowing banners and dancing spears, and rare are the lands into which there have poured such impetuous invasions of colonizing plunderers and from which have streamed so many torrents of terror stricken refugees. The Bulgarians are the sediment left by these invading streams — a very rich soil. They are the children resulting from the forced marriages of many, more or less incompatible ancestors, who left them to be trained in the grimmest school which the centuries have maintained in Europe.

First there were the original inhabitants, the Thracians. We. say they were the original inhabitants, for every place must have original inhabitants as the all explaining First Cause, which no philosopher has ever found. At any rate, at the time of Christ, which is as good a time as any to speak of original peoples, that part of the Balkan Peninsula, which is now inhabited by Bulgarians, as well as large areas to the south and north, was occupied by a race called Thracians, one of whose chief characteristics was a devotion to the soil and a predilection for a settled, agricultural mode of life. These people were ruled at one time by Alexander the Great and his father Philip and later were subjugated by the Romans. Subsequently they came under the domination of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire, were pillaged by invading barbarians of various races from the north and in the fifth century saw their land overrun by hordes of Slavs who came down from the north and took possession of the whole area. At no time since that date has the Balkan Peninsula ceased to be largely Slav. These Slavs were of many different groups and without any question they were much influenced by the natives, upon whom they imposed themselves, as well as by later invaders, but still during all the intervening ages the language and essential characteristics of most of the Balkan peoples have remained Slav, though the political power and state authority, for centuries at a time, have not been in their hands.

Generations come and go but the wooden plow remains.

There are still 450,000 of them in Bulgaria

One of the first complete defeats of the Slavs in what is now Bulgaria occurred two centuries after their arrival, namely toward the close of the seventh century by another tribe from the northeast, the Bulgarians, who were of an entirely different origin, namely Turkish or Finnish. These were a fierce, martial people, well disciplined and fearless, whose chiefs ruled with an iron hand and led the invaders from victory to victory. They pushed their conquests to the gates of Constantinople and west almost to the Adriatic so that by 900 A. B. the greatest Bulgarian King or Tsar, Simeon, ruled over practically the whole Balkan Peninsula. Besides this he encouraged literature and spread enlightenment and definitely established in his realm the Christian religion, which his father, Tsar Boris the First, had accepted and introduced. This was the golden age of ancient Bulgarian prowess and culture, the millennial anniversary of which was celebrated with very impressive solemnities throughout the whole of the Bulgarian kingdom in 1929.

Yet in this rapid and sweeping conquest of the Bulgarians over the Balkan Slavs, the conquerors were really subjugated and the defeated were actually the victors, for the Bulgarians lost everything except their name. The language which persisted was Slav and not Bulgarian. The books of the golden age of the greatest Bulgarian Tsar, Simeon, were all in the tongue of the subject race and the language spoken by the Bulgarians today is the purest Slavic. But still it is not to be doubted that those restless, long mustached, stern visaged, old Bulgarian warriors who descended from the northeast on their panoplied horses, sweeping all resistance before them, imposing drastic laws, enforcing radical reforms, brooking no opposition, and insisting on grimly regulating the daily lives of their subjects left a deep impress on the spirit of the people. They brought in an active element which has not ceased to operate. To Slav dreaminess they added a practical bent, alertness and empiricism. They tempered Slav mysticism with programs of reform and left with their people a yearning for a just and ordered world here below, inhabited by a contented, prosperous and sober humanity, which supplemented the Slav longing to lose one's self in God. In addition, certain Bulgarians still have facial features which appear to be of Mongolian or Tartar origin and these may have been inherited from this energetic band of conquerors.

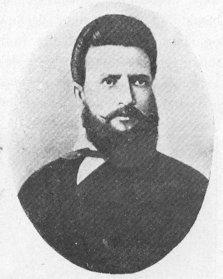

King Boris I, who after long and careful investigation,

chose the Eastern Orthodox form of Christianity for Bulgaria and introduced

it into the country in 862; he later abdicated and finished his life in

a monastery

This Bulgarian kingdom in time expended its force and lost its unity, succumbing to Byzantine supremacy and actually ceasing to exist in 1018, only 118 years after it had reached the height of power under Simeon. It was again revived in the twelfth century, after 168 years of complete eclipse, by a new native dynasty and although neither a strong nor compact state it survived the many catastrophies which threatened to overwhelm it, until the invincible Turkish hosts, sweeping across the seas which separate Europe from Asia, subjugated the whole .oi southeast Europe clear to the gates of Vienna. Bulgaria in its entirety was submerged. The light of Bulgaria seemed to have gone out. A little nation, consisting of no more than 2,000,000 souls was buried deep beneath a Moslem ocean and completely disappeared from the knowledge of the world. Not only was the state annihilated but the people themselves seemed to be obliterated.

Of course, they were not the only nation conquered and submerged by the Mohammedans. The whole Iberian Peninsula was under Moslem domination and France itself was very seriously threatened. Large parts of Italy also were held by the ruthless conquerors from Asia, while Rumania, Greece, Serbia and most of Hungary had become parts of the vast Empire of the Turkish Sultans. Rarely before had any throne, except the one at Rome, held sway over so large a part of the world. Yet of all the European peoples the Bulgarians were unquestionably in the direst plight. They were the most completely crushed and the most defenseless. It was over Bulgaria that the Turkish waves first poured in order to reach the rest of Europe, and it was there they remained longest — decades after they had receded from other lands. Bulgaria was the closest to the source of Turkish power and was buried the deepest. The Turks turned Bulgaria into a base of operation for winning and maintaining further conquest.

There was no coalition of European nations to come to her defence, no inspired monk to start a crusade for her deliverance, no power to form an alliance with. She had no aristocracy whatsoever to champion her, no clergy of her own, no schools and no body of literature to fall back upon. The teachers in her few monasteries were Greeks, all her higher clergy were Greeks, her economic masters were Greeks and her political rulers were Turks. The Bulgarians were tenders of flocks and herds, tillers of fields and gardens, the makers of shoes and caps and the peddlers of small merchandise. They were simple people who had no books to remind them of their past and they were urged by their spiritual and military masters to despise their origin and reject their very name. They were taught to accept a foreign parentage. And they lived four full centuries in darkness and obscurity, subjected to complete spiritual and political oppression.

King Simeon, the son and successor of Boris. He created

the Golden Age of Bulgaria's first kingdom

But even they at last felt breaths from the new winds that began to blow across the world and eventually developed into tempests resulting in the liberation of the thirteen American colonies and in the overthrow of the Bourbons in France. At about the time Patrick Henry was eloquently urging the Americans to seek Liberty or Death a no less determined, but milder Bulgarian hero, a monk in one of the famous monasteries which still exist at mount Athos, situated in one of those three fingers of the Chalcidicean Peninsula that dip down into the Aegean Sea, wrote a book in which he called upon the Bulgarians not to be ashamed of their nationality nor of their history, which he narrated in glowing terms. This devoted old monk was the spiritual Columbus of the Bulgarians. He discovered them anew and revealed them to themselves. His little history was the first tiny light in a very long and very dark Bulgarian night and it was the beginning of a new era, which dawned slowly amid tempests.

Father Paissy, the first herald of Bulgaria's awakening

This first ray, however, piercing through the window opened by "Father Paissy" came from a sun that was shining not for Bulgaria alone. Other lands covered by less dense Turkish clouds gathered still more of its light and heat. National awakenings began in the lands all about Bulgaria, in which bold revolutionists, operating as guerrilla bands from mountains, forests and gullies, launched desperate attacks against the cruel and corrupt Turkish tyrants. The liberation of Serbia on the west of Bulgaria began in 1804 and a part of Greece to the south of Bulgaria was freed in 1829. Rumania also, to. the north of Bulgaria, attained political unity in 1856 and secured a strong prince from "the Hohenzollern family in 1866 to serve as ruler, thus virtually putting an end to Turkish domination where it had never been so complete as in other Balkan lands. This concerted fight against the Turks continued for decades with much success, so that by the time the United States had ended their Civil War practically all the Christian peoples of the Balkans except the Bulgarians had acquired effective if not absolute independence. The Balkan Peninsula resembled a bay in early winter which has a fairly wide fringe of newly formed ice about its edges. This ice represented the lands out of which the Turks had been driven, while the water was what remained of European Turkey, namely, an area ab-)ut the size of the state of Colorado inhabited principally by Bulgarians, with a fairly large intermixture of Turks, Greeks and nomad Rumanians. The Greeks in this area, inspired and stimulated by their fellow countrymen in the liberated part of Greece, naturally kept up a constant agitation to drive the Turks completely out of Europe. And the Bulgarians also, some of the bolder and more enlightened of whom had sought refuge and bases of agitation in the freed countries adjoining their land, began a very vigorous and determined campaign for liberation, which they carried on by three different means: revolutionary activity, the establishment of schools and a fight for ecclesiastical autonomy. Their first great victory was attained in i870 when by a decree of the Turkish government the Bulgarian church was freed from the control of the Greek Patriarch at Constantinople and permission was granted for the establishment of a Bulgarian exarchate in the same city, the capital of the Turkish Empire.

A new Sofia church

This was the most significant national achievement which the Bulgarians had attained in five centuries. They had won their first independent institution and had an effective instrument to aid them in their further struggle. From then on, the Bulgarian leaders were in a position to use their church as an agency through which to teach the people that God also understood Bulgarian and would aid them, that they were not to be slaves forever and that they had the sacred duty to unite, arise, throw off the crushing yoke of Turkish oppression and take their place among the self respecting, self governing peoples of the earth. This victory, although of course arousing the bitter enmity of the Greek Patriarch who immediately anathematized the whole Bulgarian church and has never ceased to consider it schismatic, served as a powerful stimulus to the educational activity which the Bulgarians had already been carrying on with much success for years and new schools, maintained by voluntary contributions, were opened in ever increasing numbers, while books began to appear and a number of newspapers and magazines were printed — mostly outside of the country — and smuggled into the homes of the Bulgarian patriots.

Of course, as always happens under such circumstances, the most vigorous, decisive, uncompromising and popular leaders in the movement for liberation were the revolutionists, who lived in hiding, acted secretly, and tried to prepare the nation for an armed uprising against the Turks. These men were the heroes of the nation, the favorite subjects of folk songs and legends; the ideal of all the more spirited youth. They were not an absolutely new Balkan phenomenon, for there had long been mountain outlaws or "haidouks", a sort of rough and ready Robinhoods, who dwelt in mountain caves and from time to time wrought speedy and terrible "justice" on oppressive Turkish officials or heartless native money lenders. They were pictured as sacrificing everything out of love for their fellow countrymen and were believed to be the incorruptible champions of the masses. Many were the stories told and sung by the admiring Bulgarians of such implacable outlaws who, appearing in a thousand disguises, overcoming all difficulties, facing every danger and passing undetected among swarms of soldiers and policemen, triumphantly beheaded loathsome Turkish tyrants and rich Bulgarian traitors, and distributed their unearthed hoards of hidden gold among the poor and destitute, especially favoring orphans and widows. Hardly was there a secluded mountain road beneath the overhanging crags of which or behind whose sharp, wooded turns, famous "haidouks" were not reported by credulous travellers to lurk, relieving powerful heartless Turks of their lives and wealth. These mountain men, far from the heat of toil, roaming the woods in freedom, defying all authority, evading taxes, terrifying avaricious Bulgarians as well as domineering foreign lords, seemed to the common people the embodiment of justice, nobility and romance.

Admiration for direct action prevailed throughout the Balkans, every boy yearned to join the revolutionists, and the outlaw chiefs or "voevodas" were transformed in the popular imagination from brigands into the bearers of liberty.

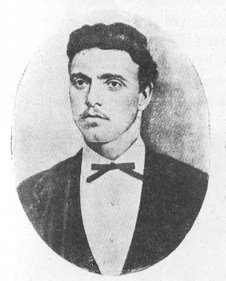

There was, of course, a sharp conflict between the revolutionists who hoped to liberate Bulgaria by persuading the concert of the powers to take diplomatic action and the revolutionists who had faith only in swords and guns. One group emphasized enlightenment of the natives and propaganda in foreign capitals while the other was all for conspiracies. The latter set the pace and dominated the trend of events. One of their chiefs, Vasil Levsky, after creating a fairly effective conspiratory network, which spread unseen over the whole country, and after repeatedly avoiding arrest in incredible ways was at last betrayed and executed in Sofia in 1873. Another more impulsive, and more romantic but less capable revolutionist, Christo Boteff, who was a poet of mre ability as well as-a restless, irrepressible, fearless outlaw, succeeded in forming a revolutionary band of armed Bulgarian youth in Rumania, who in 1876 crossed the Danube on a boldly commandeered Austrian steamboat, and pierced into the mountains of western Bulgaria hoping, like John Brown at Harper's Ferry, to start a general insurrection which would result in the driving out of the Turks. The band, however, was surrounded by Turkish soldiers and completely dissipated after many of its members had been shot, among whom was Christo Boteff himself. Because of his gripping, spirited poems, all of which were devoted to the cause of liberty, as well as because of his heroic life and dramatic death Boteff continues to be the most-popular and beloved figure in recent Bulgarian history and the mountain peak on which he fell has become a national shrine to which thousands of youth make pilgrimages every year.

Bulgarian Revolutionists

|

|

| Vasll Levsky | Christo Boteff |

| Bulgaria's foremost revolutionary hero whose exploits surpass the fantasies of the most gifted novelists. He was hanged in 1873 | the revolutionary poet. The most flaming character the Bulgarian nation ever produced. He was shot in a raid in 1876 |

|

|

| Todor Alexandroff | Ivan Mihailoff |

| who after the World War reorganized the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization to operate against Serbia and Greece andserved as its chief until he was killed in 1925 | who two years after Alexandroff's death assumed charge of the Organization and has converted it into the most powerful and deadly revolutionary instrument in the world |

Levsky and Boteff were but two of the chief revolutionary martyrs among a large number of others and as a result of their combined though not well unified efforts a general revolution finally broke out in April 1877 in the south central part of the country. Inasmuch as large numbes of well armed Turks had long been established as colonists in all parts of Bulgaria, all insurrections were doomed to certain failure and the April uprising, which was the most pretentious one the Bulgarians had attempted, was immediately put down with terrible cruelty. The most revolting massacre of Bulgarians took place in the village of Batack which was situated in the Rhodope mountains and isolated from the main lines of communications. Here the solid stone church was packed full of women and children, every one of whom was savagely butchered by Turkish volunteers or irregulars who gathered from neighboring vicinities. The village was then plundered and burnt. When the heartless executors withdrew, many of whom were not real Turks, but Bulgarian Moslems, not less than 5,000 dead bodies were left among the smoking ruins. These and similar outrages were brought to the attention of the western world by American and English journalists and scholars from Constantinople, Mr. Edwin Pears, Dr. Long, Dr. Washburn, Mr. Eugene Schuyler, and Mr. J. A. MacGahan who sent articles to the English "Daily News" and other papers. These revelations made a very deep impression in England and stirred the powerful statesman, William E. Gladstone, to launch a vehement public campaign against "the unspeakable Turk" which along with similar actions in other countries resulted in the creation of a powerful sentiment in favor of the Bulgarians throughout the whole of Europe. The diplomats of the great powers were aroused and seemed to be on the point of requiring the Turks to introduce radical reforms in their European provinces.

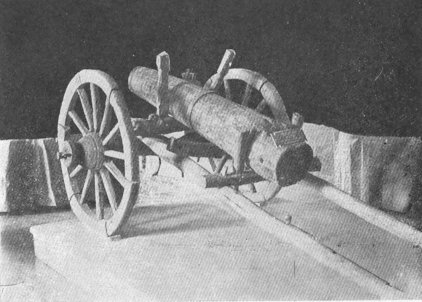

The famous cherry tree cannon, used by the Bulgarian

revolutionists in their uprising. Made of the trunk of a cherry tree it

did not prove effective. But it is symbolic of Bulgaria's struggle for

freedom. Too far from the western world to secure arms and munitions from

the Great Powers, the common people dared to try to liberate themselves

with scythes, hoes and handmade artillery

But Russia both profited from this move toward effective, concerted action and also forestalled it by declaring war on the Turks and crossing the Danube. With the press of Europe fulminating against the Turkish state and the Russian armies thundering against the Turkish fortresses it appeared that the day of deliverance for the Bulgarians had come and that a half millennium of subjugation was about to end. Very decisive victories on the part of the Russians, supported by large Rumanian contingents, made this supposition seem all the more probable and indeed on the 19th of February 1878, eleven months after the beginning of operations Russia, having annihilated the Turkish armies and crushed Turkish resistance, forced the envoys of the Turkish Sultan to sign the treaty of San Stefano at a little village not far from the walls of Constantinople, according to the stipulations of which the Moslem Empire, that had once dominated all of southeast Europe and terrified the whole Christian world, was pressed almost completely back into Asia. The Bulgarians' dream had come true. The day of liberation had arrived. By an eleven months' war and a single astounding treaty, the Bulgarians found themselves masters in a new state 100,000 square miles in extent, comprising practically all the lands inhabited by Bulgarians and larger than any of the other Balkan countries. Truly the last had become first. Three quarters of a century earlier the other Christian peoples of the Balkans had begun their struggles for liberation and in spite of all their sacrifices had won only partial freedom but behold Bulgaria as the result of foreign intervention had miraculously gained power and position of which the neighboring states had not even dared dream. The Greater Bulgaria was a fact. Yesterday's slaves had been lifted from their humiliation and given the hegemony of the Balkans. To a cautious and incredulous people it seemed too good to be true.

Alexander II, the Russian Tsar, who conducted the war

resulting in Bulgaria's partial liberation. This is Sofia's finest statue

And it was. This startling thrusting of Turkey from Europe and the phenomenal creation of a large new country filled Europe with consternation. It was unthinkable for a single power so drastically to change the map and equilibrium of Europe, so, as always happens in similar circumstances, the powers called a grand congress of the large and little states at Berlin in order to consider the new situation that hid been created, for in Europe the affairs of any two states are the business of all. This international conference of epoch making importance met in June 1878, and when it concluded its work and Lord Salsbury, the Prime Minister of Great Britain and the most influential figure at the gathering, had departed for London with peace and honor after proudly keeping the special train for the diplomats waiting at the Berlin station for half an hour, the treaty of San Stefano and Greater Bulgaria were less than scraps of paper.

A very beautiful monastery built at the foot of Shipka

Pass, where occurred one of the most decisive battles in the War of Liberation.

Here a group of Bulgarian volunteers especially distinguished themselves

by holding, though practically unarmed, a vital road against a whole Turkish

army

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]