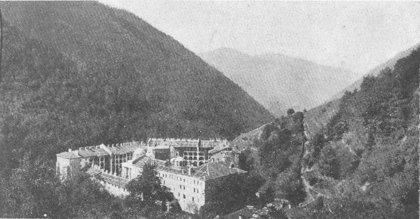

Rilo Monastery — Bulgaria's oldest, largest and most picturesquely situated cloister

CHAPTER II

The Country and what's in it and on it

One might say that Bulgaria constitutes the lower corner of the back yard of Europe, though that, of course, all depends on your point of view. Is New York or is San Francisco the key to America's back door? Does the world look East or West? Is it not the rising rather than the setting sun that our world faces? If so Portugal is in the lower corner of Europe's back yard and Bulgaria is the choice green lawn in her front yard.

In any case, Bulgaria constitutes a large part of the most eastern of the three peninsulas which Europe dangles in the green waters of the Mediterranean and related seas. The western one is Spain and Portugal, the middle one is Italy and the other one is the Balkans, which is the largest of the three and in beauty and wealth is in no way inferior to the others. Bulgaria does not embrace the most picturesque nor the wealthiest part of the Balkan Peninsula, for in Jugoslavia on the west there is a more enticing coast, a larger number of rugged mountains and a broader stretch of level plains, while in Rumania there is more mineral wealth and one of the most extensive expanses of rich agricultural land in Europe. But still Bulgaria is a favored land, one of the most desirable places in the world to live in.

It has the form of a quadrilateral and is about the size of the state of Ohio, containing precisely 39,649 square miles. On the north it is bounded for a distance of 246 miles by Europe's largest and best known international river, the Danube, which carries good sized boats clear to the very heart of Central Europe and when joined to the Rhine will bind Asia to the British Isles. The large and petulant Black Sea bounds Bulgaria on the east for a distance of 193 miles giving her two harbors and one of the finest beaches for sea bathers in Europe. Turkey and Bulgaria are contiguous in the southeast for a distance of 145 miles after which, on the south, Greece and Bulgaria have a common boundary 301 miles long. This ends at a point on the top of a lofty mountain range, Belasitsa, where Greece, Jugoslavia and Bulgaria meet. It is Jugoslavia that bounds Bulgaria on the west in a zigzag frontier 325 miles long, running from Greece on the south to the Danube river on the north.

The area on the surface of the earth, known as. Bulgaria has changed its size and shape many times during the last century, stretching out and contracting like an agitated amoeba — if that famous animal ever gets agitated. Many official and unofficial bodies and individuals have drawn Bulgaria's boundaries. The unofficial maps have been prepared in professors' studies or in diplomatic chancelleries and have always been comparatively large. The official maps have been traced on battle fields with bayonets and in most cases have been small and much hacked up. The one which Bulgaria is now wearing is among the most shrunken she has ever had to squeeze into and the whole nation complains that it is entirely too little — that it doesn't fit at all. It was presented to her in Paris somewhat over a decade ago and is of the same general style as those worn by Germany, Austria and Hungary. I am disclosing no secret when I say that there is no Bulgarian who believes that the map making season in the Balkans is closed.

* * *

Bulgaria is divided into two fairly equal parts by the long range of Balkan mountains which runs clear across the country from west to east, resembling an enormous whale lying on the surface of a turbulent sea with both its tail and head hidden beneath the waves. The northern half of the country is made up of fairly high rolling hills and most of it is cultivable. Its average height is under 1000 feet and only 3% of the total area is more than 3000 feet above sea level. Southern and southwestern Bulgaria, which comprise somewhat more than half of the whole country are much more mountainous. They contain one large, fertile and very productive plain, consisting of the fairly well watered valley of the Maritsa River and its tributaries, which because of its productivity resembles a vast garden, especially in the spring and early summer. Shaped like a wedge, it has placed its broad base upon the Turkish Republic on the southeast and, extending northwest almost to Jugoslavia, it pushes its sharp nose between the Balkan range above it and the massive cluster of Rilo Mountains below it. This last group of lofty peaks which, with the spurs running off from it, fills the whole southwest corner of the country, affords the finest scenery in Bulgaria. The chief of them all, Mount Mussalla, 9,800 feet high, towers above everything else in the Balkan peninsula except Mt. Olympus in Greece and Mt. Shar in Jugoslavia and imperiously directs the course of half a dozen large rivers, sending them at its will to the north or south or east or west. Within the recesses of this mountain cluster, not far from its grim and barren heights, are a number of small, very cold and very clear lakes, on the solitary shores of some of which are little huts to shelter daring tourists. In the narrow valleys and miniature plains on the sunny sides of these mountains is produced some of the world's best tobacco, while many large forests also abound on the lower slopes. At the foot of one of the deepest defiles, hard pressed on every side by converging mountains lies one of the oldest and most picturesque monasteries in the Balkan Peninsula.

Rilo Monastery — Bulgaria's oldest, largest and most

picturesquely situated cloister

Bulgaria is well supplied with rivers, many of which run straight north from the Balkan Range into the Danube River while a whole network of others, like the fingers of a wide spreading hand, pour their waters out over the southern triangular plain and, emptying into the Maritsa, flow together into the Aegean Sea. Although these streams are used extensively by enterprising gardeners in a somewhat primitive way for irrigation and by an increasing number of electric light and power companies to drive modern turbines, much of the wealth they carry is still unutilized. They will eventually bring light to half the towns and villages in the country and before very long the me in river system, that of the Maritsa, will be used to irrigate thousands of acres of very choice land during the latter weeks of the summer season.

The principal natural wealth on the surface of Bulgaria are her forests which are found chiefly in the mountains in the southern and southwestern part of the country and are owned almost entirely by the State and communities. The Turks after their half millennium of domination left Bulgaria, as well as all the other countries which they subjugated, largely bereft of woods, while reforestration since Bulgaria's liberation has not yet gone very far. But still 10,630 square miles or 27% of the entire surface of the country, are covered with timber, which supplies the people with most of the necessary building material. Each year 2,218,653.8 pounds of lumber are exported and 124,550,978 pounds imported, most of the latter amount coming from the adjoining country of Rumania.

Much of the unwooded area of Bulgaria is cultivated, namely 14,971 square miles, or 38% of the total surface of the country. If, to this land actually under cultivation, are added the large communal grazing grounds it brings the total available surface for agricultural purposes up to 48%.

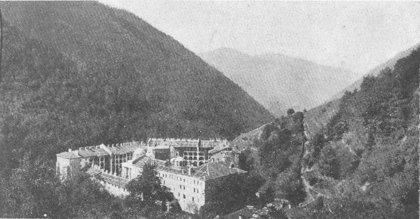

The Isker valley — north of Sofia

For the most part the soil is good and the climate healthful and fecund. Complete, crop failures never occur. There are no deserts and no waste areas. The yearly rainfall is 25 inches or about the same as in the State of Minnesota. In the matter of rainfall Bulgaria occupies a middle place among the European countries. The temperature of Bulgaria is much like, that of the State of New York. The summers are very hot in many places and the winters cold. Frequently the rainfall in Bulgaria's most fertile valley, that of the Maritsa River, is insufficient to make the land there yield its maximum production. For that reason it is to be supplemented with water stored in mountain reservoirs,.

Approximately half of the surface of the country is owned by private individuals, among whom it is very equitably distributed, and the rest belongs to the state, villages, cities, counties,. schools, and churches. The proportions are approximately as follows: communities own 25%, the state 8%, schools 1%, churches, monasteries and mosques less than 1% while 17% is not utilizable.

Bulgaria abounds in excellent summer resorts of which several are on the Black Sea, many in the mountains and a large number at mineral springs with which the country is richly supplied. More than a hundred of these, scattered throughout the whole of southern Bulgaria, are still largely unutilized and many of them have not y£t been even studied, but there are scores widely used by the local inhabitants and six which have been supplied with the best modern conveniences and are visited by thousands of people from all parts of the country, who find the greatest benefit 'in their healing waters. There are not a few places in Bulgaria where the women regularly do their washing at hot springs, several of which have been equipped with modern wash houses.

The country is rich in mineral wealth, most of which is still unexploited. There is salt in large quantities, vast deposits of coal, much lead and zinc, copper, oil, manganese and even silver. These deposits are all the property of the state which turns certain areas over to private companies for study and exploitation. The utilization of the subsoil wealth has not advanced very far yet, but is making rapid progress and proving to be the source of much wealth.

* * *

Most of the people in Bulgaria continue to live in the country. Altogether there are only 93 cities of which but ten have as many as 25,000 inhabitants. On the other hand there are 5,756 villages, which are inhabited by 80%, of the total population.

The largest city is Sofia, the capital, situated in the western part of the country in a broad level plain at the foot of Mount Vitosha, which is 7544 feet high. Sofia is a very ancient settlement and trading center, known in ancient times under the name of Serdica. However, it fell into complete decay during

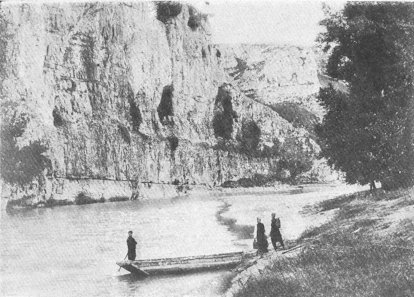

The National Assembly

the long Turkish domination and when Bulgaria was freed fifty years ago it was no more than a wretched, oriental town with uneven, crooked streets and small one story houses. But the last half century has completely transformed it and made it one of the largest and most attractive cities in the Balkans. It has grown with extraordinary rapidity during the last two decades increasing its population from 102,812 in 1910 to 154,025 in 1920 and has 230,000 at the present time.

The hub of what may be considered the cultural or civic center of Sofia is the large Parliament Building, which is surrounded at shorter or longer distances by ministries, foreign legations, the Academy of Science, the Holy Synod, the Cathedral of Alexander Nevsky, which is easily the finest church building in the Balkans and among the notable ones of Europe, the state printing plant, museums, and the university which will eventually consist of a number of large buildings, only one of which has so far been finished. Between this and the business center of the capital lie the King's palace and the wooded park which surrounds it, while in the outskirts of the town have grown up within the last few years various industries carried on by more than 200 factories. One of most striking buildings is the new National Theater, which has the most modern equipment in the Balkans and houses both the drama and the opera. Within the last five years a large number of enormous cooperative dwelling houses have been built, which are owned by the people who inhabit them, each family possessing a separate apartment. The highest structure in Sofia is the Vegetarian Home, a restaurant and apartment house, seven stories high, costing 60,870 dollars, just put up by a cooperative society composed of the followers of Tolstoy who founded the organization twelve years ago in an extremely humble way, largely for poor students and with a total capital of 3,261 dollars.

Sofia possesses a good street car system, has at its disposal an adequate amount of cheap electricity from two sources and is bringing down past Vitosha from the Rilo mountains, 50 miles away, an inexhaustible supply of the purest water. It is on the main international railroad line from London to Constantinople and will be on another important railroad line that will eventually be constructed from the Baltic Sea through half a dozen countries to the Mediterranean.

It possesses a number of well kept parks, one of which is a veritable forest and constitutes the most attractive city playground south of Bucharest and east of Lubliana.

Sofia's oldest cathedral, Saint Sofia, built in 1329

The life of Sofia accurately reflects the spirit of the people. It is free from extravagance and in none of the stores is there a lavish display of articles of luxury. It is not characterized by gayness and after midnight most of the streets are fairly quiet. Women of pleasure, found in such abundance in most European cities, are almost completely lacking in Sofia, though there are a few cabarets, patronized largely by foreigners. The gayest hour of the day is in the early evening when the shops and offices are closed and all the younger people in town put on their best clothes and turn out to walk up and down the finest street "Tsar Osvoboditel", at which time all vehicle traffic in this municipal boulevard is suspended, as two almost unbroken columns of youth circulate back and forth from the royal palace to Boris Park a mile distant. If you have a friend you wish to meet, you may be almost sure of finding him sooner or later in this evening parade or of finding someone who has seen him. It is after this evening walk is over, namely at eight or nine o'clock that the people of Sofia take their evening meal. And every city in Bulgaria has a similar main street where the inhabitants take the air in the evening, learning the latest news, seeing the latest styles and meeting the youth of the other sex that their friends have told them about.

Poganovski monastery — a relic of Turkish times

Another place in which you may be sure eventually to find your friend is at one or another coffee house. Each evening the writers meet in one, the journalists in another, the business men in others, and each political party in its appointed one. To walk down the "Tsar" with the crowd and to visit your coffee house is a part of the day's routine, the main part, in fact, for which the rest was made. As you swing a cane on the street, exchanging bright remarks with companions or, sipping a two cent cup of Turkish coffee, hear a colleague read a poem, excoriate one your rival has written or tell you of prospective contracts some ministry is about to conclude or assure you your party is about to come to power, you feel that you are a not insignificant part of the world that counts. Besides, it's exhilarating to see about you so many well dressed people, even though you know they've had those clothes for years and altered them every season, and it's the most delightful of harmless vices to sit on an accustomed chair at a little round table before a tiny cup o thick brown coffee with miniature rainbow bubbles on top and "hwoop" the hot, delicious liquid into your mouth with loud, appreciative suction. This evening stroll and the leisurely seance about the coffee cups greatly slow down the tempo of living and make you put off until tomorrow many things which you certainly ought to do to-day, but who knows how much more important those things are than a genial two cent cup of coffee. Perhaps it's no small attainment to sit before all those tasks feverishing trying to thrust themselves upon you and quietly to brush them back without even a dramatic gesture or the slightest qualms of conscience. At any rate, every nation in .southeast Europe tint has driven from its borders "the unspeakable Turk" has taken care to retain his leisurely cup of delicious coffee, which always makes your head ache.

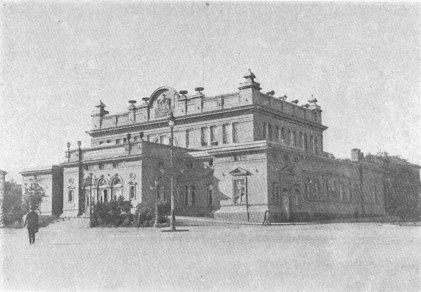

Philippopolis

The second city of Bulgaria — we may even call it the second capital — is Philippopolis, which is found in the south central part of the country, clustered in most confusing, labyrinthic streets about three rocky hills, rising sheer from the vast level Maritsa plain. It contains a large number of very large tobacco factories and is the center of trade in agricultural products.

A more interesting and livelier town, though by no means so wealthy, is Bulgaria's northern seaport and third city, its chief bathing place, Varna, on the coast of the Black Sea, with 69,000 inhabitants. For decades it was a very busy market place, into which enormous quantities of grain from the very productive plains of northeast Bulgaria poured on its way to the outside world. But when at the close of the World War, Bulgaria's amoebian map suddenly contracted, leaving the golden fields of Dobroudja in the hands of Rumania, Varna was left with idle wharfs and empty store houses. So she resolutely set about to transform herself from a city of profitable work into a city of lucrative play. Convenient and attractive casinos and bath houses were erected along the clean, sandy and very gently sloping shore of the Black Sea, making one of the finest beaches on any of the six seas washing the Balkan Peninsula. It is visited each summer by thousands of Czechs, Poles and Rumanians, while all the Bulgarian trains carrying passengers to Varna during the season for half a cent a mile are crowded with pupils, teachers, laborers, artists, writers, state officials, politicians and other folks with vacations, who covet brown skins and have faith in the magic power of violet rays. All this makes Varna the gayest and brightest place in Bulgaria.

Much livelier is it than its sister city 139 miles to the northwest, Roustchouk or Roussie with 46,500 inhabitants. This is a very tidy, self confident and attractive town to which English literary critics refer as a village when mentioning that it is the birth place of the famous writer Michael Arlen, but the people of Roussie would by no means be pleased to hear the fourth city of their kingdom referred to in that way. It is situated in the extreme northeast corner of the country on the Danube river and is Bulgaria's largest river port. It has clean streets, neat buildings and enterprising citizens and disposes of large quantities of most excellent farm and garden products which large numbers of Rumanians like to cross the river to buy because they are so very cheap. When the line of communication from Poland through Bulgaria to Greece is completed it will add to Roussie's importance and wealth.

The only other Bulgarian city with as many as 35,000 inhabitants is Bourgas, the country's second largest sea port, which is growing very rapidly and as a business center has surpassed its larger rival, Varna. Bourgas is on the coast of the Black Sea, south of the Balkan range, 155 miles north of Constantinople.

* * *

These are the chief Bulgarian cities — only one with a population of as much as 100,000 and only five containing over 30,000 inhabitants. The rest are country towns. And that enables you to picture Bulgaria — a peasant land, a country of fields and vineyards and orchards and gardens, the abundant products of which equal the best in Europe. It is a land flowing with milk and honey and with all other good things to eat. From the day in early spring, when the markets begin to redden with hand made willow baskets full of giant strawberries, clear through the rose season and the cherry season, through the wild strawberries and raspberries, blue berries and blackberries, through veritable floods of muskmelons and watermelons, apples, pears, apricots and plums too numerous to pick, through red "drenkies" from wild bushes for inimitable jellies and through all of the most exquisite sorts of grapes, which are found almost every where in great abundance — through all these seasons of delicacies up until the time snow falls, Bulgaria offers you the choicest things that sun and rain and soil can produce at prices found no place else in Europe.

Besides, her lofty mountain clusters, her proud peaks, her sheer grim

crags, her precipitous defiles, her grassy hills, dark, silent forests

and foaming cascades deserve all the songs of praise the Bulgarians sing

about them. And in addition, every passing year discloses large new sources

of wealth under the ground. Bulgaria is a very good place to live in, a

land which if one has once visited he loves to return to.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]