Small town houses of the better sort — workshops downstairs, dwelling above

CHAPTER I

What is Bulgaria?

This little book is an introduction to Bulgaria. But not an "introduction" in the solemn, somniferous sense in which a learned professor uses the word when he writes an "Introduction to Philosophy" or an "Introduction to Ethnology". It is rather a sort of letter of introduction. But still not like most such letters either, for when a person presents a letter of introduction you may be pretty sure that he wants something of you. In this case Bulgaria is making no request. She doesn't even know I'm going to try to introduce her.

She is a good friend of mine and it is as though, while walking along the street with her, I should meet you, one of my acquaintances, and say, "Why, hello, Gentle Reader, I'd like to have you meet Bulgaria; I'm sure you'll find her a rather unusual and very charming acquaintance. She is .....".

Well, that is just what I'm going to write about now. What is she? What is it that is peculiarly Bulgarian? What are the most striking characteristics of this land and people, their mark or tone? What is it that distinguishes them from the other twenty-seven nations of Europe? What is it that I have in mind when in some other land I say "This makes me think of Bulgaria" or "In Bulgaria it's not like this?"

* * *

Bulgaria means a vast abundance of delicious things to eat. It means health and vigor, hard toil and strenuous amusement. Bulgaria has a clear sky and a bright sun. It has stern, forbidding mountains to master; deep, dark woods to wander through; a tumultuous sea, grumbling on a gentle shore, to bathe in and deep sinuous ravines to entice you along foaming streams up into wild, lonely solitudes.

Bulgaria is a myriad of little fields of many shades, waving one against the other; daisy filled meadows dancing about the feet of grassy hills; whole seas of flaming poppies streaming gaily over wide plains; green, purple laden vineyards marching in rigid rows up sunny slopes; verdant gardens crowding down to sluggish streams and creaking with clumsy, slow turning irrigation wheels; thousands of bashful red tiled villages, crowning hill tops, nestling in gullies, straggling through woods, clustering about springs and strung along rivers.

Bulgaria is flocks of black and white sheep grazing over mountain sides; stupid black buffalo almost imperceptibly moving along jolty roads, pulling squeaky wagons filled with heavy loads on the tops of which sprawl sleeping drivers; great herds of grey cows defiling from scores of little towns to the common grazing grounds each morning and returning in the evening, every cow going unerringly through the arched front gate of her own yard past a low, pink, wide roofed house to her stall in the stable near by; tiny, illkept, shaggy horses, tireless as hounds, gay with thick strands of blue beads and noisy with jangling bells, pulling clumsy carriages rapidly over mountain roads.

Bulgaria is a vast summer plain, buzzing and flashing with brightly dressed peasants as thick as bees in a clover patch near a cluster of hives. Oxen with hunched backs pull plows across small fields as women guide the animals and men the plows; babies hang in checkered, home spun hammocks on the branches of trees or on improvised shaded tripods; lines of moccasined women in hand-spun, home woven, black, one-piece, short-skirted dresses that are set off by wide red belts and beautifully decorated sleeves and fronts, work their way with giant, short handled, three cornered hoes across gardens and vineyards; grandmas with distaffs in belts watch the geese in grassy plots and with their nimble fingers make the innumerable filaments of the white wool which they are spinning blend rapidly into the ever lengthening thread as whirring water racing down the stem of a funnel; little boys carry water in jugs from the nearest spring and distribute it among the workers; large family clusters gather under the wide spreading trees that dot every Bulgarian landscape when the sun is at its highest and hottest, and eat bread, onions, cucumbers and sour milk, as tightly swaddled babies, wearing blue beads at their foreheads to counteract the charm of evil eyes, nurse and gurgle at young mothers' breasts.

Small town houses of the better sort — workshops downstairs,

dwelling above

Bulgaria is a golden harvest field covered with peasant boys and girls who gather ripened grain and nourish tender romances. The girls standing in long lines, with their backs sharply bent amid the waving oceans of wealth which tremble as ripened poppy petals ready to disappear before the sudden winds and devastating hail storms that often attack the country, cut with garden sickles those countless fields, a few stalks at a time, laying the grain in winrows behind them for boys to bind into sheaves and pile into shocks, in the broader plains threshers, driven by straw burning engines, thresh the wheat, while in the mountain villages horses or oxen, chased in ever shortening circles around a post in the middle of a threshing floor, tramp out the grain.

* * *

Bulgaria is a concert, a symphony and a choir. Harvest girls in the cool of the evening, slowly sickling their way back and forth across dry fields, sing folk songs in unison and harvest boys, working behind them, take up the strain and answer the song. Neighboring groups join in and pass the music along until the whole countryside — clear to the very rim of the land where a golden sun slowly drops into a golden prairie — echoes with couplets sung in tact with snipping sickles. On holidays the squares of the villages quiver with the trilling of tireless bagpipes, played by jolly men, about whom brightly dressed circles of happy boys and girls, clasping one another by the hands or belts, weave round and round in rhythmic, intricate steps hour upon hour. In other villages dark skinned gypsy minstrels arrive with tripping, laughing fiddles and the youth and maidens do their folk dances to livelier, jauntier music; while in the smallest settlements, where there is no native bagpipe "maister" and whither no gypsies wander, the young folks dance to their own shrill, monotonous music as the girls sing a refrain from one end of the revolving line and the boys answer from the other. On Saturdays and Sundays the woods and mountains resound with the voices of scores of thousands of tourists who with knapsacks on their backs tramp along secluded shady paths to little huts on distant peaks, where during long night hours beneath a moon riding over the tree tops they sing of forests, fatherland, revolutionists, war, love and freedom. While best of all, — by far the best of all -- little shepherd boys standing beside their flocks on lofty hillsides blow from frail and delicate flutes poignant, piercing melodies all atremor with the hopes and dreams and pains and sacrifices of unrecorded generations of obscure people who for more than a millennium, keeping flocks, tending gardens, making cheese and embroidering exquisite violets on home made kerchiefs, watched the Romans march in conquest over their plains, the Crusaders stream down their valleys, Barbarians sweep across their mountains, the Turks submerge their whole land in the oppressive darkness of subjugation, five centuries long, and Russian hosts come with the dawn from the East to deliver them. All the repression, suffering and aspirations of those ages vibrate in the shepherds' songs; each little flute pipes alone but through it pour the sighs and the prayers of a nation.

Thinking it over. Two villagers from Sofia district

Bulgaria is a workshop, a land of nimble fingered "maisters", who sit in small open rooms in the midst of boys and young men that are working and learning, in hope that they also in time will sit in their workshops as "maisters" among their apprentices and journeymen. If you want a new pair of shoes you will go into such a shop, step, in your stocking feet, upon a sheet of paper and let the "maister" take your measure. In another shop they will knit your sweater, in a third make your suit of clothes, and in a fourth prepare you a sheep skin cap. Similar shops make wagons, saddles, kettles, jugs, bracelets, bridal wreaths and all the other things a frugal peasant nation has need of. If you should go up into the mountains in the spring you would find hundreds of "mandras" where "maisters" make the Balkans' most delicious white and yellow cheeses from sheep's milk, while in Bulgaria's famous rose valley during the month of June other skilled artisans are distilling golden drops of rose oil from avalanches of pink petals gathered every morning with the dew still on them.

* * *

Bulgaria is a land of fashions where "the mode" holds sway with imperious authority. But it is not the mode of Paris or New York. 'Tis not a style panting after the latest novelty. Here grandma is supreme and not the flapper. If you should look at the old family album you would not snicker for the girls dancing on the village square to-day and dressed in their very best, might all be wearing the clothes of their mothers' great aunts. Yet each village of course has its own great aunt, and so its own styles. In some the village girls wear black skirts that are' long and pleated; in others white skirts of light material; some decorate their costumes with orange flowers, others with red robins; some insist on dark headcloths and others wear gay; some give handkerchiefs as wedding gifts and others towels; some wear small aprons aflame with color and others large aprons with only a row of flowers worked on the lower edge. But it is all just as it should be. It is all proper and conventional. It is what mother and grandmother wore and what father and grandfather approve of. Nor are fancy styles restricted to the women only, for in certain localities the men too are highly adorned. All sorts of jaunty figures are worked into their sheepskin coats; their wide and flowing shirt sleeves are sometimes fringed with lace, and their shirt fronts glow with exquisite hand worked decorations while the little wooden jugs they carry their wine in are sometimes as beautiful as a colored page from the Bible of a medieval monastery.

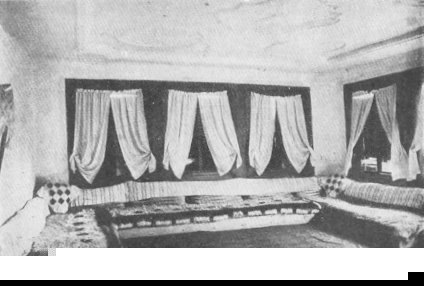

A guest room

All codes of conduct in Bulgaria are as rigid and inflexible as the dictates of style and fully as old fashioned. The Bulgarians are a solemn people and take life in dead earnest. "Thou-shalts" and "Thou-shalt-nots" have been impressed very deeply upon their hearts. They have the gloominess of the Slav and the grimness of a New England Puritan or of an Old Testament Jew. The sternness of Moses and the inexorableness of Amos have descended to them. They often seem to feel the burden of the ages and of the universe on their shoulders. Watch a line of old Bulgarian women sitting on the whitewashed stones in front of their houses on a Sunday and observing the life of the town as it passes up and down the streets. They are neat and stiff and proper, not animated even in their gossip. Their dresses are dark and their headcloths are dark with a little dark lace about the edges. When the Mayor or Colonel passes on the sidewalk, they all rise, bow and then solemnly sit down again. From their infancy up they have walked in prescribed paths and are proud that they have never failed to do their duty. And you may watch their husbands on the same Sundays in the coffee houses. They sit rigid, neat, stern, warmly dressed in thick baggy clothes with their sheep skin caps upon their heads, quietly fingering large yellow beads and decorously smoking cigarets. Now and then they take a noisy sip of dark Turkish coffee and from time to time pass severe judgment on some adventurous youth who has departed from the ways of his fathers.

Or you might visit a Bulgarian on his nameday. This is really the happiest occasion of the year, a much more important celebration than a birthday among Americans or English. The house is spick and span and the person of honor is dressed in his best to receive all his friends and neighbors. And they all come to see him too for not to 'go to see Peter on Peter's day, Mary on Mary-the-Mother-of-God's day and John on St. John's day would be an unpardonable slight. And when you arrive you will be met at the door by the host who will shake hands with you, bid you welcome and usher you into the guest room where you will shake hands with each one of a large number of other guests seated on long divans running about the sides of the room. When you have finished your greetings and taken your place among them the host will again welcome you and then after elling you that you are looking much improved they will all ask you how you and your folks are and give you their felicitations, whereupon you will inquire about them and their folks ' in the same solemn and decorous way. This will practically exhaust the conversation and you will continue to sit in the tranquil, rarified atmosphere of a Quaker meeting. Only you mustn't get nervous and feel that you have to say something in order to liven things up. That isn't at all necessary. They are all having a perfectly good time and sense no need of giggling or trying to make smart remarks about banalities. Shortly the hostess will give you a spoonful of delicious jelly or preserves which you will take straight, with a sip of water as they all politely wish you the best of health. Then the guests will leave, one by one, in the order in which they arrived and in the meantime others will come to take their places.

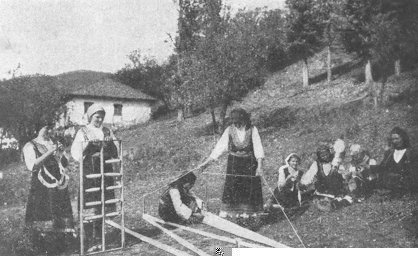

The Bulgarian women clothe the nation — or at least used

to until a few years ago

Frivolity is avoided and levity condemned. Go to a Bulgarian art exhibition and see the statues of typical Bulgarians as chiseled in marble by the sculptors who best know their people. What solid, massive characters you see! What determined faces, what devotion to the established order, what readiness to suffer for accepted ideals, how much squareness and fairness and rigidity! How little affectation, what a scorn of artificial beauty, what crushing condemnation of coquetry, what merciless rejection of girls that have strayed, what abhorrence of men who have broken their promises, what heroic acceptance of hard situations! These mothers completely wear themselves out to educate a son, girls endure unbelievable hardships to put a brother through school, children arise when fathers enter the room, wives arise when husbands enter, in public a bride would permit herself no more intimate expression of affection than to kiss her man's hand. These are the kind of people that pay their bills, build houses, accumulate land, open schools, erect churches, construct public fountains.

* * *

And the Bulgarians are economical. Their frugality is proverbial. To live well on little is a cardinal virtue. Extravagance is an unforgivable sin. To waste is both folly and iniquity. Lavish ostentation is sheer vanity. This frugality and economy has placed its stamp on every phase of Bulgarian life. "Skromnost" or modesty is a national ideal. Utility and practicality are its corollaries. On excursions many Bulgarians carry their shoes in their hands so as not to wear them out. When traveling the whole nation rides III class. In certain other countries the more prominent members of the intelligentsia would feel embarrassed to condescend to travel in a third class car, but a Bulgarian, imbued with the psychology of his race, even though he were a National Representative or university professor, would feel out of place squandering money in a second class car when he could get to his destination just as quickly on a third class ticket. Less perfumery is sold in Bulgaria than in the neighboring countries. There is less luxury, less money spent on amusements, less gaiety. There is no great white way and the night life is very much restricted. People go to bed and get up early. There are very few luxurious automobiles. There are no titles, no grand establishments. There are men of means but wealth is not displayed. The people make their clothes last many seasons. They eat simply and usually rent out the extra rooms in their houses. They go without extras. But not without essential things. They are solid folk and invest their money. They have a passion for owning something. They all try to buy a little land and build a house of some sort or a part of one. They insist on all sharing in the essential benefits. There are common grazing grounds. There are common woods. Train fares are low. Streetcar tickets are cheap. The State Bank until now has been at the disposal of common people. The Agricultural Bank is for the mass of peasants. The Cooperative Bank serves small store keepers and artisans. Thus they try to make the state serve everybody. All subsoil wealth, whenever it may be discovered, belongs to the state. Hidden treasures left by persons fleeing from invaders in the course of the last two millenniums are by law not the property of the one unearthing them but of the nation. Bulgaria is like a great family in which each member presumes that he has a right to an equal share of everything, and he does not hesitate to holler for it.

Preparing the warp for the loom

But for that share he is willing to work. That is the nearest thing to aristocracy there is in Bulgaria, pride of workmanship. The Bulgarians are gardeners and extremely good gardeners. They go by the hundreds into all parts of southeast Europe in order to tend gardens and sell fruit and vegetables. They rejoice in their gardening superiority. They take pride in their ability to go into foreign countries and excel the natives in the natives' own home towns. They feel that they are master workers, that they know the secret of perfect tomatoes, strawberries, peppers and cucumbers. They possess a prowess and have gained an international reputation and they are not ashamed of their achievement.

They are also good peasants. Bulgaria is a peasant nation The chief work of practically all of the people is to produce things from the earth. And they take pride in doing it. The land they till is their own as well as the animals on it and the tools with which they work. And the Bulgarians are passionately attached to their land. They have inherited it for the most part from their parents and are dominated by a tradition that it is a sin to sell it. The village looks with disfavor on a peasant that disposes of his land and most every Bulgarian family feels that it is a calamity to part with a field. And even when a peasant rises in the world and moves from his village into town he continues to work a garden and keep a pig and cow. And it is probably the Bulgarian's love for the soil that inspires him to work it so well. He has turned his country into a garden, he]has made his plains and valleys the most beautiful and fruitful in this part of the world, has covered his land with passable roads, and is transforming squalid villages filled with wretched huts into modern towns. He goes to work very early in the morning, returns late in the evening and toils with energy and skill. The peasant and his family attend church, rest on holidays and fast in season. He sends his children to school, supports the village cooperative society and is a member of the Peasant Party. Although he has not had the privilege of learning of modern methods from a landed aristocracy as the peasants of Hungary, Poland and Rumania, and though last freed from Turkish rule, he has surpassed all his neighbors in many ways and is proud of it. He is famed for his diligence and in lands outside of Bulgaria you may hear the expression "To work like a Bulgarian".

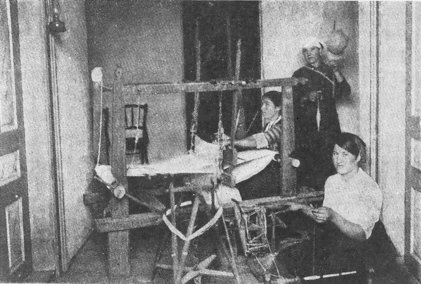

At work on the loom

* * *

These are some of the things that characterize Bulgaria, that constitute the Bulgarian spirit. What you find is not the gaiety of Rumania, the agility of Greece, the melody of Italy, the clarity of France. It is rose gardens, tomato patches, harvest girls, fields dotted with workers, bagpipes, sad songs which everybody sings, bewitching flutes, flaming poppies, hard earned money carefully spent, promises kept, duties performed, honor maintained, an honest measure delivered, a passion for education, a grim, mystic sense of obligation to play a role in the dramas of the onward moving ages.

* * *

In the descriptions or characterizations which follow I am not going

to toot Bulgaria or pat her on the back. No one is less her press agent

than I. After a long sojourn in the Balkans I have acquired a strong aversion

to petting the little nations and "sicking them on". A multitude of terrifically

powerful, volatile dements are very much mixed up in southeast Europe.

The great duty of all those working for the prosperity and happiness of

humanity is to search for a suitable medium which will hold these elements

in a stable solution, is to work out a fair and enduring equilibrium. Such

an equilibrium can be attained only through mutual compromises. It is dangerous

for any Balkan nation to acquire all that it wants in the way of territory

and power, to realize all its ideals, to make good all its "sacred rights"

because these sacred rights clash terribly. Therefore, I am not in favor

of a "Grand Rumania" or a "Grand Serbia" or a "Grand Hellas" or a "Grand

Albania" or a "Grand Bulgaria". I do not endorse all of Bulgaria's "inviolable

claims", nor those of any other nation. I am not pleading any Bulgarian

cause nor marching in any Bulgarian crusade. In spite of my own frugal

tastes I insist on indulging in the luxury of being very fond of many peoples.

And among them are the Bulgarians. I have spent years among them and always

enjoy returning to them. It gives me pleasure to tell you about them and

that's why I am doing it. I hope that they will succeed in arranging their

differences with their neighbors so that all the Balkan peoples may live

together in harmony, security and prosperity.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]