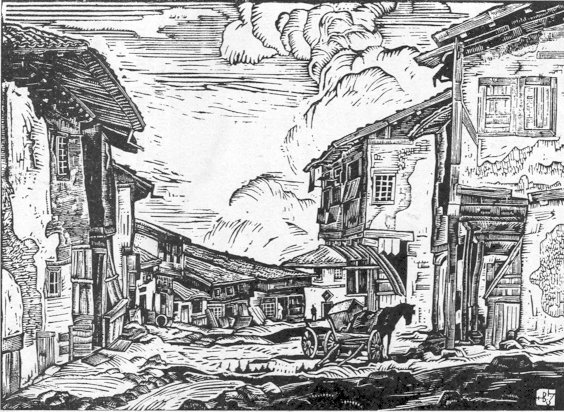

A street where artisans work, in the old town of Samokov. Woodcut by Vasil Zaharieff

CHAPTER XVI

Making things

A.

Industry in Bulgaria is a child — or stepchild — of the handicrafts. But it is a heartless progeny and, although still young and quite immature, threatens to drive its mother out of house and home. Which is really most tragic, since the mother, though modest, plain and old fashioned, was remarkably clever and irresistibly fetching in her day. Agile, buxom, resourceful and indefatigable she called the tune to which the Bulgarians danced for more than a century. Though decidedly domestic she was not afraid of the dark and continually travelled from one end of the Balkan Peninsula to the other. Though reverently observing the precepts of her ancestors it was she who brought Bulgaria into the new and modern world. The story of her development, domination and decline is one of the most fascinating romances that the Bulgarians have been the authors of. It is told with songs, the pounding of iron and brass, the knocking of looms, the creaking of spinning wheels, the tapping of wooden nails into tanned hides, the roaring of smelters, the puffing of forges, the gnawing of saws and the tread of heavily laden pack horses on mountain paths.

Over a century and a half ago the handicrafts and the guilds in which they were organized became the most important institutions in the social life of the people. They were a means of livelihood, a school, the chief support of religion, an economic organization and the main vehicle for social expression and control. The artisans and their unions dominated culture, morals, fashions, beliefs and economics. They were the channels through which all that was most vital in Bulgarian life flowed.

And indeed it did flow, for the artisans were very busy, active folks living beside restless streams that helped keep their simple machinery in motion and furnished them with the essential medium in which to soak some materials, wash others and dissolve still others and from very early in the morning until extremely late at night all these people kept pounding, hammering, kneading, rubbing, rotating, baking or boiling something.

You may take the city of Gabrovo as an example of one of the artisan towns and imagine yourself there half a century ago. It is in the midst of the Balkan range, strewn for miles along the rapid river Yantra, at a place where the stream flows through a long, narrow valley. Every workday in summer as the morning sky is greying and in winter at an hour when pitch darkness still fills the valley the inhabitants arise, and after pouring water over their hands and dashing it in their faces set to work — on empty stomachs. In many of the houses, lighted by tallow candles, looms begin to clank and spinning wheels to whirr. In scores of others potters kick the wheels of their molding tables and by revolving formless hunks of soft, grey clay through skillful fingers make jugs and jars and crocks and charcoal stoves.

In one whole quarter you hear the pounding of the kettle makers and see the glow of their forges through little windows. The flaming, glaring pits where iron is being smelted make another large section of the city resemble a colony of volcanoes. In another district hundreds of men sit cross-legged on low platforms, sewing fur caps and coats," while on the other side of the street men and boys sit sewing and pounding on shoes and sawing out wooden sandals. Further up the stream "tepavitsi" mills go whack-whack-whack, kicking thickness and consistency into home-spun cloth with their giant feet, and in the best section of town the tailors are making tight jackets and huge, baggy pants. Practically no one is idle. Rare is the house in which something is not being made.

A street where artisans work, in the old town of Samokov.

Woodcut by Vasil Zaharieff

And the hours of toil are very long, the working days averaging fourteen hours for everyone. The only rest periods are at meal times and they are brief. The Gabrovo artisans worked out the American system of taking their meals long before George Washington cut down the cherry tree. The breakfast, dinner and lunch, consisting largely of dry food, are usually gulped down in a hurry, often in the workshop, the boss and his men all sharing the same food. At night, they have a warm stew, topped off with sour milk, and they eat this meal more leisurely, squatting about a low table in the master's dwelling, which is above the shop.

Everything is well organized and rigorously controlled. There is no racketeering nor contraband, no adulteration nor price cutting. Each craft has its guild, to which every master is obliged to belong and this organization lays down the law. It is conducted by an honorary president — a wise old master — and a paid executive secretary — a young, active master. The former pronounces righteous judgments and the latter puts them into force. The matters to which these guild heads give their special attention are inferior work, false measure, unfair competition, abuse of common machinery or sources of power, bad treatment of employees, working on Sunday and unbecoming conduct. This patriarchal guild president with the impressive title of "Oustabashiya" considers himself called upon to keep his fellow workers in the straight and narrow path both in the workshop and out of it.

On Sundays and the big. religious holidays all work is strictly forbidden. No new "maistor" may be received into a guild and open a shop without the consent of the old ones. Any proprietor who, by cutting the established prices, spoils a deal that his neighbor has made is punished. The heads of the guilds are judges, prosecutors and sheriffs. They are elected by their fellows but once elected have an astonishing amount of power. They run not only the union but the whole town as well. If they find that a "maistor" has beaten his workers too hard, or has not punctually paid them their salary of four dollars annually, or has over charged his customers or has given only 35 inches for a yard, they may at once summon the guilty party to the office, which is a little room in the church, and fine him or suspend him. And if one of these guild chiefs having gone out to execute justice does not find the offending "maistor" in his shop, he will merely take the missing proprietor's leather apron down from the peg on the wall and spread it over the work bench or the selling counter and that means the shop is closed. A prostrate apron is as good as a padlock and the culprit had better straighten matters out at once if he wants to keep his "maistor's" certificate and his right to do business.

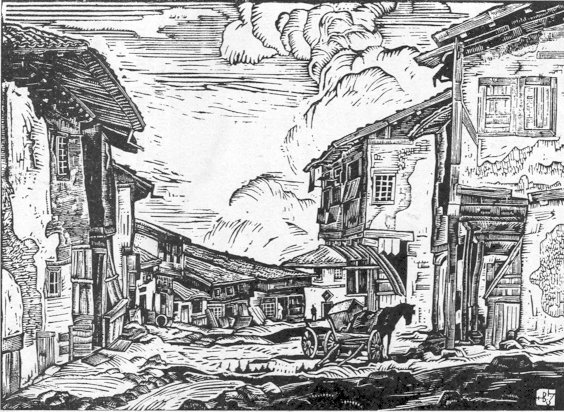

Houses of the most prosperous artisans, in the town of

Drenovo

The guilds really played the roles now taken by political parties, cultural societies, Y. M. C. A.'s, cooperatives, philanthropic associations and foundations. They supported the church, built and managed schools, helped the poor, advertised the home town, looked after the youth, kept the girls from going astray, bought raw materials and sold finished articles.

They also very carefully regulated the relations between the bosses and the workmen, though strictly speaking, in these workshops there was no such thing as employer and employee. There were instead, "maistors" and pupils. And it was the pupil, the "chirak" or apprentice, who had the hardest lot among all the hard lots. The school he had to go through was Spartan in the extreme — before he finished it, he, like the material he worked with, was beaten, kneaded, and molded into shape. Both the masters and the guild secretaries had a right to beat him. Everybody bossed him around. He usually slept in the workshop on a pile of cloth or a bag of wool.

These "chiraks" entered the service of some "maistor" at about the age of twelve. At first they carried water, ran errands, swept, scrubbed and did menial household tasks, but after the first six months they began to do "real" work and gradually advanced in the craft.

During the first two years they received no pay except their board and perhaps a pair of shoes. In frequent cases they even paid for the chance of becoming apprentices. It was like entering school. They studied as well as toiled. For the work of the third year they were usually paid something — from two to five dollars for the twelve months.

This marked the end of the hardest period of apprenticeship and after the third year most boys became "kalfas" or journeymen and their salaries were raised to four dollars anually. During the fifth year the "kalfa" got ten dollars and by the seventh up to twenty-four dollars annually.

By the end of that time if he was twenty years old and recommended by his "maistor" he might graduate into the guild as independent "maistor". When he paid his initiation fees he was given a certificate, permitting him to open a shop of his own and to engage little "chiraks" who helped him and learnt the trade. Of course the guilds were always careful to prevent any over-supply of "maistors".

It must not be supposed that the handicrafts were carried on by men only. To be sure the guild members were all males yet much of the work was done by women. They in fact were the principal factors in the making of cloth. During a fairly long period their looms and spinning wheels were responsible for a large part of the prosperity of the Bulgarian town people. They actually supplied the Turkish army with much of the material for its uniforms and laid the foundation for commerce and for a national spiritual awakening.

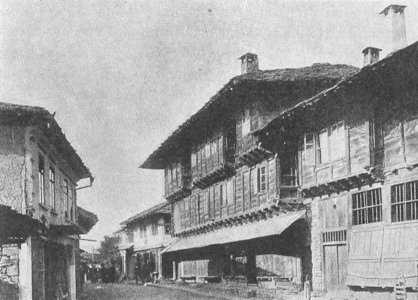

The raw material of Bulgaria's leading handicraft. In

the Rilo Mountains

Cloth making with them was not a pastime but an occupation. Practically all worked at it twelve or fourteen hours a day and so assiduously that whenever they left the house they tucked a distaff in their belts and spun as they walked or waited. When the girls went to parties they spun and shepherdesses never left for the mountains with empty hands. When at home the women spun on wheels and that yarn was always the best. In every house there were looms and the clanking of them was heard all day long. The three rest periods at meal times were usually less than half an hour each.

Along side of this making and selling of cloth other handicrafts sprang up and, in additon, an extensive trade was developed. There were makers of looms, of spinning wheels, and of carding and whipping devices. There were strange noisy little mills called "tepavitsi" for beating the cloth. Water by running down a race into them manipulated gigantic pairs of wooden legs that kept kicking the cloth against firm wooden blocks making it thick and fuzzy. After the kicking was over the cloth was put in wooden vats containing whirlpools that cleansed it.

Hundreds of people were engaged in gathering roots, bark, leaves and grasses to dye the yarn and other hundreds made great brass kettles to do the dyeing in.

A whole handicraft for making a sort of sacking for packing the cloth existed.

The manufacturing of black braid called "gaitan" for trimming the clothes developed into one of the most flourishing crafts in the Balkan peninsula. This "gaitan" helped make the Bulgarian artisans famous far outside their land and the creating of little water mills for braiding it came to be a very lucrative trade.

Even more profitable was the making of the cloth into suits, an exclusively men's occupation. First were the "abadjias", making rough native garments after old oriental models. Then came the "francterzias", making a specialty of more elegant women's clothes and they gave way to the "shivatches" or "pantalonjias" who made real European suits.

Certain Bulgarians travelled all over the Balkans selling the cloth, the braid and the garments. They visited all the annual markets and opened stores in the chief ports and largest cities. They were usually bachelors and returned home only at long intervals to get merchandise and see the folks. Some of these became the rich men of Bulgaria and the bearers of culture and progress.

Gaining an acquaintance with the outside world, they brought back books, new sorts of machines, new styles and ideas. They opened schools, served as unofficial Bulgarian diplomats abroad and started the revolutionary movement for ecclesiastical and political liberty.

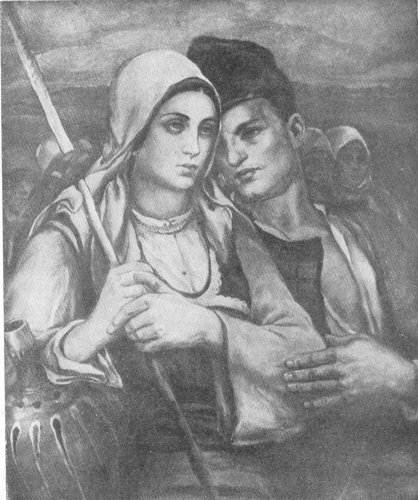

By N. Kozhuharoff

The boy is going abroad to work; that's why they're so

sad. If you're in love parting's hard whether you're prince or peasant

What an intricate life radiated from those clumsy, clanking looms! What a complex economic system the grandmas with distaffs in their belts supported! And what future songs, poems, books and constitutions all those illiterate women wove into their thick, brown cloth!

* * *

The buying of wool, dyeing it, spinning it and weaving it into cloth, making the cloth into garments and selling them was one of the most complicated, best organized, and most lucrative of all the Bulgarian crafts but another one of much importance also was the preparation of skins and hides and the converting of them into caps, coats and shoes. The materials for turning hides into leather were practically all of native origin and collected by the people, while the tanning itself was done in small primitive workshops. Shoe-making came to be a rather complicated trade and passed through several phases of development.

The simplest kind of footwear that was made were "nalums", which might be described as low and comfortable stilts. Westerners may think of stilts merely as toys for amusing restless boys but they are really very useful contrivances, forming an essential part of the equipment of Bulgarian shepherds and herdsmen, You may often see such persons striding over rivers and through swamps on them.

Of course, the women in towns and villages do not need to be so much exalted as shepherds, since they do not ford rivers nor wade in swamps but they continually have to navigate through very slushy yards and along roads and streets filled with mud. So they use domestic stilts, that is, a pedal under each foot, the toe and heel of which rest on blocks two or three inches high and an inch thick. A strap over the toe of the pedal holds it onto the foot. In other words it is a high sandal. These "nalums" always sit just outside the door of the house and when the women leave they slip their feet under the toe straps and go clattering, clumbering off with a darting motion like that of skaters, but largely devoid of grace. On returning they leave their shoes at the door and step into the house in their stocking feet.

It goes without saying that a "nalum" is a crude and clumsy creation — it looks like a little board resting on two little boxes, although of course it is really sawed from one hunk of wood. Nobody enjoys ugliness, so the master craftsmen from the very beginning attempted to add a bit of form and beauty to these primitive clogs. They gave curves and grace to the stern, pointed the prow and spread out the support under the toe so as to make it resemble a very thick sole. They also painted the visible parts with some bright color, preferably yellow, and worked a few fancy figures in the toe strap.

Women of Dobroudja — a province which the peace treaties

gave to Rumania

In addition to that, under the influence of rich and dainty Turkish women who wore much lace, exquisite velvet jackets and rich silk bloomers, the sandal "maistors" replaced the toe strap with silk cloth, which was enlarged so as to cover the whole front of the foot, made the wooden part very fine and delicate, with high, slender heels and brightened it all with gold and ivory ornaments.

Then it was no longer a clumsy "nalum" but a "chehal", not a sandal but a slipper, or rather a half slipper consisting of a sole and a toe. And the best Bulgarian craftsmen made the Turkish belles hundreds of "chehals" which for brightness, grace and elegance were equal to the finest shoes made at present in the capitals of Europe.

The Bulgarian men have worn neither "narums" nor "chehals" but "tsarvouls" and "iminiyas", that is moccasins and coarse black slippers. The moccasins in Bulgaria are extremely simple — just a piece of tanned pig skin tied about the foot with leather thongs. The "iminiyas" required much more work, though they were little more than strips of sole leather sewed by hand to very simply constructed uppers. Of course they were fitted over wooden forms and usually assumed a shape almost as much like a shoe as like a flat boat. For decades they were the foot gear of the leading men in town. And the "maistors" who made them and tanned the leather for them were among the richest of the craftsmen.

But just when these shoemakers had climbed up to a quite stable social and economic world there drifted into the quiet, obscure, little mountain towns young artisans who had travelled and traded in Constantinople and Rumania and who thought that shoes could be made with wooden tacks. These rather slick and sporty boys were the joke of the country for a while with their strange tick-tack, tick-tack and their curious wooden pegs, which clearly could not hold two pieces of leather together and on rainy days would leave the rash people, who were so foolish as to trust in them, walking through the mud in their stocking feet — a prospective sight which caused the sewing "maistors" great hilarity, so that they often bantered the boys with such questions as: "Well, how are the little pegs makin' it today?"

But to their consternation the little pegs made it astoundingly well. They held best of all in wet weather and the shoes created by the peg "maistors" were cheaper, prettier and much more in demand than the old "arks" with the clumsy seams. So a revolution in shoe making followed and in all the shoe shops in all the mountain towns all day long you heard men pounding little wooden pegs into awl holes.

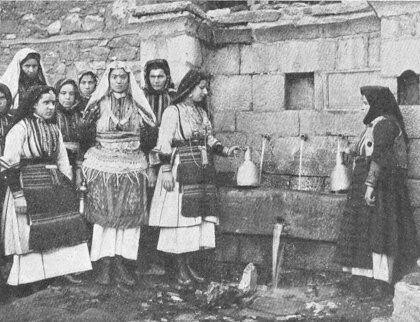

Macedonian women gather at the fountain

And these new fangled shoes made with wooden pegs had a wonderful quality;

they all squeaked enchantingly, so that for a time the Balkans resounded

with peg shoe choruses proclaiming that modernism had arrived. This, however,

seemed intolerable to the Turkish Pashas and Beys, who considered squeaks

a mark of aristocracy, so they decreed that all except the highest officials

must have their shoes desqueaked. Which of course gave the Bulgarians one

more reason for revolution. Such tyranny was almost as bad as the Stamp

Act.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]