Ruins of an old Roman gate in south central Bulgaria. From time to time many relics of ancient Rome are unearthed

CHAPTER XV

Getting into the band-wagon!

There are a great many political parties in Bulgaria and, as every place else in the world, they are in bitter conflict with one another. As one watches the fury of their onslaughts, the intricate combinations into which they enter and the compromises which they make he is inclined to conclude that the chief reason for their existence is to place their adherents in control of certain sources of wealth and in possession of jobs. The motto of practically everyone of them is, "You get up so that I can sit down". When out of power they eloquently espouse the highest principles and carry on holy crusades with most desperate heroism, accepting great risks and making enormous sacrifices but when they get power into their hands they commit most of the offenses which they execrated in their election campaigns. The party struggles have been so bitter and violent that every leading Bulgarian politician has at one time or another been in exile or in prison or both, not a few have been beaten or personally humiliated and many have been murdered. Partisan passions are furious and political methods are brutal. The caricaturists have made a big stick the symbol of one party and a hefty rail of another. The platforms in the names of which the parties so fanatically fight are practically identical and in scores of cases men who were yesterday political allies marching arm in arm are today ferocious opponents, hurling imprecations at one another.

The turbulence of Bulgarian politics tends to dishearten even the best friends of the country and as one observes the vulgarity of the party press, the brutality of party campaigns, the unscrupulousness of many party leaders, who place limited group interests above those of the country, one is inclined to lose faith in the ability of the people to govern themselves efficiently. They use up much of their best strength in futile conflicts, they poison idealism with political sectarianism and degrade real patriotism with partisan venality. Yet a broader view and a more detached estimate is reassuring. If one is in the stream of Bulgarian partisan politics or standing beside it, he is dazed and despondent but if he studies its course from some higher, more distant point of observation from where he can also see the political stream of other nations, he notes that, after all, Bulgaria's river is advancing, that it moves less and less in vain circles, that it is becoming calmer and more fruitful. One can even say that the bold and dangerous democratic experiment which Bulgaria dared to risk when it drew up its constitution fifty years ago is justifying itself.

Bulgaria at that time had just emerged from the Turkish Empire, by far the worst governed land in Europe, and the nation was completely without political experience so many mistakes and excesses were to be expected. There was no dominant class and no authoritative tradition to impose restraint. A society of very energetic but rather simple and untrained folks without any chiefs or captains was suddenly freed and told to govern itself. Naturally there was a frenzied scramble for the first places and most of the men who managed to get on top were soon yanked down to make places for others; [in the melee there was inevitably much shoving, yelling and pommeling. But it was no worse than politics in England a century or so ago and not much worse than the situation in America immediately after the Revolutionary War. In fact Bulgarian political excesses are no more flagrant than certain excesses that occur in the United States even now.

This is sad but it is also encouraging. Bulgaria is passing through a period of growth and is hopefully advancing. Many European countries have given up the democratic experiment. Bulgaria, in spite of all her straying, marches very resolutely along the path of popular self-government. And not only that. Though recently liberated and though oppressed by a terrible tradition of Moslem political violence, Bulgaria has maintained a fairer and more democratic government than almost any other state in southeast Europe. When viewed in the large, Bulgaria's parties show comparatively good records. Most groups of human beings make a bad mess of self-government. Bulgaria is no exception, but she has the satisfaction of knowing that she has not done so badly as many other peoples in similar conditions.

Ruins of an old Roman gate in south central Bulgaria.

From time to time many relics of ancient Rome are unearthed

Her many political organizations may be divided into three chief groups: the old "law and order" parties, the Peasant League and the Communists. Of course that characterization "law and order" is not altogether accurate. This group is sometimes known as the "citizens' parties", "the historical parties", "the old parties", and "the bourgeois parties". As a matter of fact they are for "law and order" just now, but when they were younger a number of them were considered radical, revolutionary, nihilistic and destructive. In the meanwhile, however, other more progressive and radical groups have appeared so that the old ones now seem staid and steady. They are three in number, the "Narodnyatsi", the "Liberals", and the "Democrats". The "Progressives" form a section of the "Narodnyatsi", the "Radicals" are an offspring of the "Democrats" and the "Liberals" are always divided into several quarreling factions. It is significant that all of these "old", "constructive" parties have names signifying advance and progress. No party has ever dared appear before the Bulgarian electorate and ask for its suffrage in the name of conservatism. The Bulgarian masses have always wanted leaders who at least made a noise like progress and reform.

The "Narodna" or People's Party is in many respects the most stable and conservative political organization in the country. It may be considered the extreme "right wing". Most of its supporters are satisfied people, fairly well-to-do, holding quite important economic and social positions. In this group are many bankers, not a few of the older and more substantial merchants, most of the wealthier villagers, including a majority of the peasant saloon keepers. This party has descended from the old Bulgarian "chorbadjias" who were the leading men in each community in Turkish times and who sometimes aided the Turkish authorities in the exploitation of the Bulgarian masses. For quite a while after the liberation of Bulgaria the best educated, the most cultured and the most gentlemanly people in the country were members of this party. They came more nearly forming a Bulgarian aristocracy than any other group. They are the "ins" in life, and being favored by inheritance or ability are very often the "ins" in politics. They have been in power oftener than any other group. They are considered crafty and calculating by their opponents and are often called "Byzantines" which means "Orientals". As a matter of fact they undoubtedly embody a very sound social and economic element and impose themselves largely because of their worth and ability. Strange to say, although they are the Bulgarian conservatives, they are not imperialistic nor over patriotic. They have always been advocates of peace and moderation and of an understanding between Bulgaria and her neighbors. Practically without exception they have been opposed to revolutions and revolutionists. They have wanted stability, tranquillity and order. This party roughly corresponds to the Republican Party in America, but because of the pressure of prevalent Bulgarian tendencies is not so conservative. Generally speaking, the most moderate political group in Bulgaria Way be considered more "to the left" than the most radical group in the United States.

The Liberal Party or Parties are composed of the aggressive Bulgarian patriots. It has been a bold, active and vehement organization. The "Narodnyatsi" have usually employed a certain amount of finesse, tact and subtlety but the Liberals depend on vigor and main force. At times they have been very daring and heroic, making the greatest sacrifices in defense of their cause but when in power they have been among the most brutal and tyrannical. The main source of their power has been patriotism. As long as Bulgaria was still actively engaged in liberating Eastern Rumelia and in trying to free Macedonia and as long as she had to struggle against Russian domination in her internal affairs this party had an attractive mission, appealing to heroic spirits; but now that peace is desired and crusades for liberating wars useless, the Liberals seem doomed to play an unimportant role. Since it was this party that placed Bulgaria on the "wrong side" in the World War, bringing her overwhelming defeat, and since its members are reputed to have used their patriotism as a cloak for flagrant corruption at very critical moments when disinterested patriotism was most needed, it has completely lost the popularity it had two decades ago. It will again come to the fore only if conditions in Europe so develop as to enable the Bulgarians to participate in another war for the liberation of Macedonia. This is the most brutal and ruthless of the "bourgeois" parties. The leader of one of its factions, Stephan Stamboloff, rendered Bulgaria very notable services during the first two decades after Bulgaria's liberation.

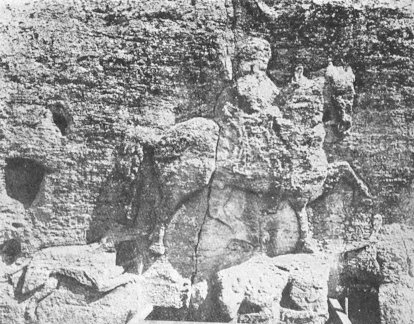

The most imposing, massive and mysterious ancient relic

existing in Bulgaria, a giant horse and horseman cut in the face of a sheer

lofty ridge of stones at Madara not far from the Black Sea port of Varna

|

|

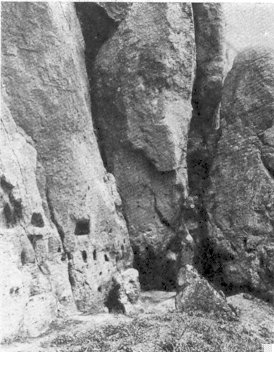

| Another view of the Madara horsemen with accompanying inscriptions | Caves in base of Madara cliff – once used as places of worship |

The Democrats and Radical Democrats are not so aggressively nationalistic as the Liberals and not so inclined to stand pat as the "Narodnyatsi". They are "outs" rather than "ins", they draw much of their support from the newer or younger intelligentsia, from persons of ideas and ideals, who have wanted to turn Bulgaria into an European state. The founder of the group, Petko Karaveloff, was one of the most forceful and capable men in recent Bulgarian history and during most of his very stormy career was fairly true to democratic ideals for the sake of which he made great sacrifices. Though minister and prime minister several times he never accumulated any wealth. Another leader in this group, the late Naitcho Tsanoff, was esteemed by all Bulgarians and is remembered as an unfaltering champion of fairness and honesty in politics. The present chief of the party, Alexander Malinoff, is considered one of the most honorable politicians in Bulgarian public life. The Democrats and Radical appeal to approximately the same class of people as the other bourgeois parties but are a little nearer to the masses, are guided by more progressive principles and have followed somewhat higher ideals. However, all of these parties are at one in believing that a small group of city intellectuals have the right to run Bulgaria and to direct the simple peasant masses. They have all been inclined to use the peasant votes as weapons with which to fight one another.

Not all of the peasants have been willing to play this humble role. Many of them long ago came to feel that whatever party won the elections it was the peasant masses who lost them. The agriculturists and shepherds became convinced that they were being fleeced by all the city politicians, of whatever name or color, and some of the more aggressive of them set out to form their own party, the People's Agrarian League. The movement started at the beginning of .this century and at first was one of the noblest and most idealistic social crusades which simple, exploited people ever launched. The earliest Agrarians were in reality apostles and missionaries to the people. What they were working for was peasant uplift and they hoped to achieve it by enlightening and disciplining the villagers and by drawing them into a strong and efficient peasant association which would be able to conduct the affairs of the country. They argued that Bulgaria was a peasant land and therefore that the chief attention should be given to the welfare of the peasants. They emphatically pointed, out that their movement was not a political party but an all inclusive social, cultural, economic and political society, capable of transforming the whole life of Bulgaria.

They hoped to bring about this reconstruction by constitutional and not by revolutionary methods. They held that they comprised the majority of the Bulgarian people and believed, therefore, that it would be easy for them, controlling Parliament, to make and enforce the laws. The principles which constituted their platform were very radical, some being excellent and many naive. They were opposed to liberal state pensions for comparatively young employees, to big salaries for the officials, to excessive expenditures for the army, to ministerial automobiles, to bureaucracy and every other practice that tended to favor a small group of city intellectuals. They wanted to distribute the few large holdings of land that existed in Bulgaria, to establish cordial relations with all Bulgaria's neighbors and in general to bring about a peasant Utopia. The founders of the movement were austere, devoted men, who went on foot from village to village preaching the new gospel and trying to induce the peasants to awake, organize themselves and become masters of their own fate. The evils against which the Agrarians fought were believed to be the creation of the city people, whom they rigidly excluded from their party, priding themselves on their own rusticity, simplicity and "wholesome ignorance". They thought their sound common sense was worth more than the "tainted learning" of the intellectuals. And they taught that in as much as the- interests of the town people were irreconcilably opposed to those of the peasants there could be nothing but war between the two groups. What the Agrarians wanted to do was to supersede all the old parties at the head of the government.

And, due to a dramatic and disastrous succession of events, they succeeded in realizing this ideal at the close of the World War. The defeat, humiliation and economic burdens which that war brought to Bulgaria not only left the country in a very unsettled state but also brought the old political parties into discredit. They were held to be responsible for the calamity. All the wisdom of all the wise men, so carefully trained in the course of forty years, had gone for nothing 'so it seemed to be time to try the simplicity of the peasants. In any case it was not a moment for pondering but for deeds. The returning soldiers were actually in a state of revolt, and something had to be done to quiet the spirits of the masses. So the Agrarian League for the first time in its history was invited to participate in the government. It gladly accepted and having set its feet firmly in places of power soon shoved all the other parties out. It then held a number of elections, securing an increasing number of votes in each one, until by the spring of 1923 it held 212 out of 243 seats in the National Assembly. The hard hands of the men with the hoe held all the reins of state. Parliament was aflame with the wide red belts of the villagers. The city intellectuals were under the heels of pig skin moccasins. All of the old political chiefs were in jail or exile. Great was the triumph of the villagers. Shepherds and plowmen had replaced the professors. The Peasants' Prime Minister Alexander Stamboliisky boasted that they would rule forty years.

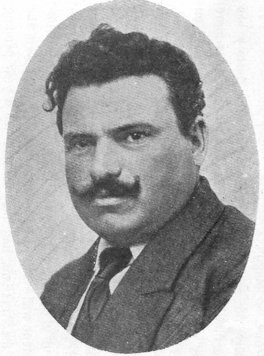

It was of course a foolish boast, but not alt of Stamboliisky's thoughts were foolish. He was an extraordinary man, and exercised a vast influence over the peasant masses. He was heavily built, broad shouldered, aggressive and domineering; bushy black hair crowning a fairly large head gave him a still more forceful appearance. He had a high school education and had studied abroad but knew no language well except Bulgarian. He was an unusually trenchant writer, though he had a limited range of ideas based on no new political philosophy, and was a compelling orator, filling his speeches with multitudes of striking and telling illustrations taken from every day life. He was absolutely sure of himself, firm in his convictions, quick in his ecisions, bold and daring in action, ready to take risks and undergo suffering. In 1915, he frankly told King Ferdinand that it would be a fatal error if he forced Bulgaria into the war on the side of Germany and assured the king that he would lose his throne if he took such a step. Because of such sentiments he was kept in jail during the war, but when the Bulgarian front collapsed he went almost directly from prison to a ministerial chair. At that moment Stamboliisky was not the head of the Agrarian League but the second in command under Dimiter Draghieff, an older, more idealistic and more moderate man, who had been one of the chief founders of the Peasant Movement. Stamboliisky's fiery temperament, extreme views and bold acts soon precipitated a conflict between himself and the older chief, in consequence of which Draghieff withdrew leaving the wilful demagogue complete master of the impetuous, inexperienced and impressionable peasant masses. Unrestrained, he went headlong to his destruction.

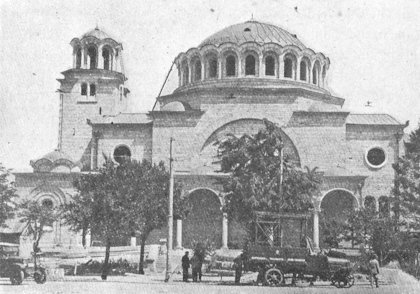

The new Sofia church "Sveta Nedelya" replacing one of

the same name, blown up by Communists on the Thursday before Easter 1925,

killing 150 people. The aim of the conspirators was to kill the King and

his Ministers, but the victims were all outsiders of no political importance

Stamboliisky's government passed many wise and helpful laws. Not a few of the things his party advocated would certainly have been beneficial to Bulgaria. His semi-revolutionary radicalism, his peasant origin and his unsparing opposition to the old parties, which had brought so much disaster to the country, attracted for a time many of the intellectuals to the peasant leader, so that if he had governed with moderation, using ordinary political acumen, he might really have brought in a new political era. But he threw all prudence to the wind, alienated his potential friends, dismissed his experienced and moderate political advisers, surrounded himself with incompetent boys, whose only qualification was that they constantly flattered him, and opened war on everything in Bulgaria that was not from and of the village. He aroused the bitterest opposition of the professors, business men, bankers, priests, army officers, journalists, Macedonian revolutionists and ordinary patriots. To the educated people of the country everything seemed to be upside down. The whole country smelt of the stable. All the rules of social organization were reversed. Ignorance was a passport to position and education was made a sign of incompetence. Anarchy also broke loose. Peasants used to take charge of the trains, they used to come in bands to Sofia, looting stores, devastating printing offices and firing their guns in the streets. In addition, a Peasant Guard was formed to counteract any hostile; move of the army officers and it appeared that Stamboliisky had entrenched himself in power both by means of ballots and bullets. All the former ministers were to be tried before a special court. It was rumored, in addition, the throne even was to be abolished. In any case, many of the patriots thought the situation so serious that they would be justified in risking their lives to change it.

Yet the Agrarian danger, though the most pressing, was not the worst. Bulgaria at that time had more Communists in proportion to the number of her inhabitants than any other country. The same humiliations, injustices and privations that had induced so many peasants to become members of the Agrarian League drove scores of thousands of workers, teachers, lawyers, small intellectuals and even young villagers into the revolutionary Communist Party which in 1903 had broken off from the Bulgarian Socialist Party, founded in 1890 to fight against the violence, tyranny and corruption of the old bourgeois groups.

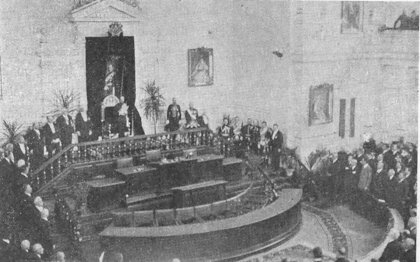

Interior of the National Assembly. King Boris is standing

in front of his throne reading an "address of the crown". The ten ministers

and speaker are standing solemnly in line on both sides of him. Below are

the chairs of the president and vice-presidents, the orator's tribune or

pulpit and the ministerial bench. The seats for the deputies are in front

of this bench, facing it. On the king's left sit the Agrarians, Socialists,

Communists and Artisans — "the left-wingers", that is the reds and pinks

— and on his right the "Democratichesky Sgovor", the bulwark of patriotism,

law and order — the "rightwingers"

After the World War the Communist Party was the best organized, best disciplined, most enthusiastic and most aggressive social and political group in Bulgaria. Its members were among the best read, the most widely informed and the most enlightened people in the country. They were obsessed with the consciousness of having a great mission to perform, were indefatigable in their propaganda and quivering with the expectation of a fundamental change in the social order. And they took their crusade very seriously; they meant business. They were out and out revolutionists. They expected to launch a general uprising, to seize the Bulgarian government, inaugurate a dictatorship, crush the bourgeoisie and divide the property of their wealthier neighbors. Communism was a religion, a culture, a social theory and a political campaign. It published widely read dailies, wrote and distributed far more books than any other group in Bulgaria, created a pleasant, captivating, enthusiastic social atmosphere for its members young and old, preached a new pedagogy, maintained an extensive cooperative enterprise, directed many labor unions and had far more fanatical rabid young disciples than any other religion or political movement.

There were not as many Communists as Agrarians but they were far better organized and far more enlightened and aggressive. They created the thought world in which a large part of the young Bulgarians lived. In addition they were of course in very close touch with Bolshevists in Russia from whom they received directions and large and regular subsidies. The people by the hundreds of thousands actually believed that the red sun was to rise over a red sea, that the heads of the rich people were to roll in the streets and that a new era of justice and general prosperity was to be ushered triumphantly in. Of course, millions of Christians also believe in a coming world cataclysm, a second coming, but the Bulgarian Communists believed in their approaching paradise in a very different way; they really expected it, nervously awaiting it as runners do the crack of the pistol and they were itching for the race to start.

A Number of Statesmen

|

|

| Andrei Liapcheff | Alexander Malinoff |

| Chief of the party of "Democratic Concord" and the strongest political leader in Bulgaria. Firm, indefatigable, calm, resourceful | Leader of the Democratic Party and Bulgaria's most finished, refined, cultured politician. More nearly like an European than the others |

|

|

| Yanko Sakuzoff | Stoyan Omarchevsky |

| Founder and leader of the Socialist Party. In spite of his "redness" he has retained the goodwill and esteem of his nation | the most able among the leaders of the Peasant Party. Minister of Education in Stamboliisky's cabinet. Has wide connections in America |

The Communists and Agrarians were not allies but they were fighting

a common enemy, the old parties. Potentially these two radical groups maintained

a common front. In any case the numerical strength of one and the aggressiveness

of the other created an extremely dangerous situation for the people who

had always governed Bulgaria, so the bourgeoisie decided to resort to desperate

measures in order to overthrow the peasants and forestall the workers.

On the night of June the eighth 1923 a conspiracy led by professors and

officers arrested most of the Agrarian ministers and established a new

government under the Premiership of Prof. Alexander Tsankoff. Little violence

was necessary and there was not much bloodshed. Practically all of the

peasant leaders were seized and imprisoned, while Stamboliisky, who was

in his native village fifty miles from Sofia at the time, was captured

after a few days of fighting and put to death. The old political leaders

were released from prison where Stamboliisky had kept them for nearly a

year and the old parties merged in a new "law and order" organization,

known as "The Democratic Concord". They forgot the long and bitter conflicts

which they had waged with one another during many past decades, furled

their old banners, disbanded their old battalions and formed a common army

to fight the Green reformers and Red revolutionists. The peasants and workers

also joined forces in a "united front" and following directions from Moscow

launched a rather extensive revolution in September 1923, which after being

cruelly suppressed by "law and order" forces, both regular and volunteer,

was followed by terrible reprisals. Most of the revolutionary leaders fled

into Serbia where they found refuge, support and encouragement in a long

set of conspiracies against the Bulgarian government. Both sides were passionately

embittered and two turbulent years of latent civil war ensued, the cruelty

and violence of which culminated in the blowing up of the Sofia church,

"Sveta Nedelya", at a moment when it was filled with the most prominent

people in Bulgaria. They were attending the funeral of a general who had

been murdered by the conspirators for the purpose of bringing all the members

of the government under the large charge of high explosive that had been

placed in the cupalo of the building. This stupid and brutal outrage, committed

by a group of Communists, resulted in the death of 150 people, among whom

were none of the Ministers. Naturally it precipitated a furious outburst

of vengeance that ignored the forms of jurisprudence and summarily disposed

of most of the Communist and Agrarian leaders who were still alive and

in the country.

|

|

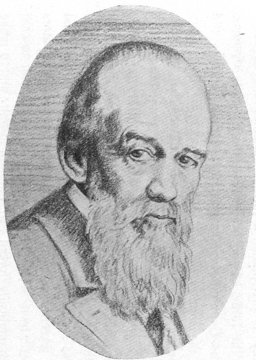

| Alexander Stamboliisky, the most striking political leader. A founder and former chief of the Agrarian League and for four years Prime Minister of Bulgaria. In June 1923 he lost his life in consequence of the bourgeois coup d’etat which thrust him from power | Crandpa Dimiter Blagoeff, the founder of for years the chief of Bulgaria’s revolutionary Communist Party. His doctrines and plans threw Bulgaria into turmoil and caused the death of many ardent followers but he survived the upheavals, dying in bed at a ripe old age |

Even before this, stringent laws for the Defence of the State and an enraged public opinion had outlawed the Communist Party and put the Agrarians under a rigorous political quarantine. Democracy in Bulgaria had almost gone bankrupt, bitter hatred obsessed both sides in the struggle, fear hovered over the land and order was maintained only by force. Parliament saw that the Tsankoff government, made up primarily of the conspirators who had overthrown Stamboliisky, could not put an end to civil strife, so it dramatically forced Mr. Tsankoff to retire and to make way for a more conciliatory cabinet under the leadership of a prominent member of the old Democratic Party, Andrei Liapcheff. He became Prime Minister in January 4, 1926 and announced a policy of "gentleness and kindness" in the colloquial words "so krotse, so blago".

Practically no government chief in Bulgarian history has faced a more difficult task than Mr. Liapcheff and none has more conscientiouly carried out his mission. The new cabinet relied on exactly the same parliamentary support as its predecessor had, namely the "Democratic Concord", formed by a merging of the old "law and order" parties. Parliament consisted of a large government majority, a few Democrats and Liberals who had refused to join the "Democratic Concord" but who tended to favor the Liapcheff government, and of a small and vehement opposition made up of Agrarians, Socialists and camouflaged Communists. Parliament was really a battle field. On the right were the men whom the Agrarians had held in jail for a year pending trial before a special court and on the left were meager remnants of two powerful and militant parties, all of whose leaders had been killed, imprisoned or exiled by the men on the right or by the social groups and classes, which those men represented. Fierce passions tended to smother the spirit of constructive legislative activity. Scurrilous accusations were hurled back and forth, fists were vehemently shaken and deputies often started from their seats in the direction of their opponents. It was such spirits, in and out of parliament, that Mr. Liapcheff had to quiet. His aim was to prevent all excesses from the right and from the left without violating any of the regulations of the Constitution and without suppressing civil liberty. He tried to check new outbursts of passion and preserve comparative tranquillity so as to allow time and oblivion to heal old wounds.

And his efforts were not in vain. He is a man of vast patience, indefatigable industry and iron nerves. He is cheerful, calm, full of faith in his people and their reasonableness and always expects the best rather than the worst. He personally is incorruptible, asks little for himself, puts on no airs and is always at his post. By his calm facing of many crises, his patient solving of one grave difficulty after another, his minimizing of "red" scares and other real or bogey menaces, and his leniency and optimism he rendered his country a great service, doing much to restore democracy, to assuage hatred, dissipate Suspicions and revive confidence. He adhered strictly to the constitution, frustrated all tendencies toward a dictatorship, prevented extremist adventures and kept Bulgaria in the middle of the road. Bulgarian democracy is not yet out of the woods; political passions have not been extinguished and the great task of calming the right wing fanatics and of taming the left wing crusaders by transforming their vehemence and mass strength into a constructive reforming force has not yet been completely achieved, but the country is moving forward.

On the twentieth of April, 1931, after parliament had finished its regular four years term Mr. Liapcheff's government resigned for the purpose of facilitating the King in the creation of a coalition cabinet to conduct approaching elections. Alexander Malinoff was called by His Majesty and authorized to carry out this mission, but his repeated efforts to bring all the moderate bourgeois parties into a single government failed, so after a crisis lasting two full weeks Andrei Liapcheff's cabinet again assumed power. Since, for a good many vital reasons, large numbers of people in Bulgaria were tired of the government of Mr. Liapcheff and his party, after its eight years continuous domination, a Malinoff cabinet would have brought a feeling of relief, especially in view of the fact that Mr. Malinoff, chief of the Democratic Party, is the most finished, cultured and genial statesman in the country. He is known as a man of moderation and tolerance, tree from prejudices and red complexes and is believed to be sincerely enough devoted to his nation to place general interests above those of his party, so it was hoped by many that, if successful in forming a coalition government, he would be able to hasten the process of reconciliation between the Agrarians and the "Democratic Concord" thus making political life seem less like civil war. But his failure to induce the various party leaders to cooperate with one another under his leadership required the postponement of his mission and left a rather strained and somewhat uncertain political situation.

Nevertheless it is well to point out that politically Bulgaria weathered

the storm of the World War better than any of the defeated powers and is

essentially stable. Changing economic and social conditions, the awakening

of the peasantry, the creation of a small working class and -the rapid

growth of the intelligentsia necessitate certain fundamental political

adjustments which will not be easy. But little by little the peasant masses

will come to participate in the government of the state after they have

learned to make their party not the apotheosis of ignorance, but the embodiment

of efficient, trained peasant democracy. The future of Bulgaria depends

upon the ability of the peasants to form a wise, disciplined, moderate,

well led party. For this a vast amount of mass enlightenment is necessary.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]