PART III. THE MONUMENTS

Chapter IX. The Monuments — I : Constantine to Justin I (Early Fourth to Early Sixth Century)

1. The ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica, Philippi 99

2. The ‘Agora’ Basilica, Thasos 106

3. The Rotunda of St George, Thessalonica 108

- The Martyr Saints in the Dome of St George 112

- The Architectural Compositions in the Dome of St George 113

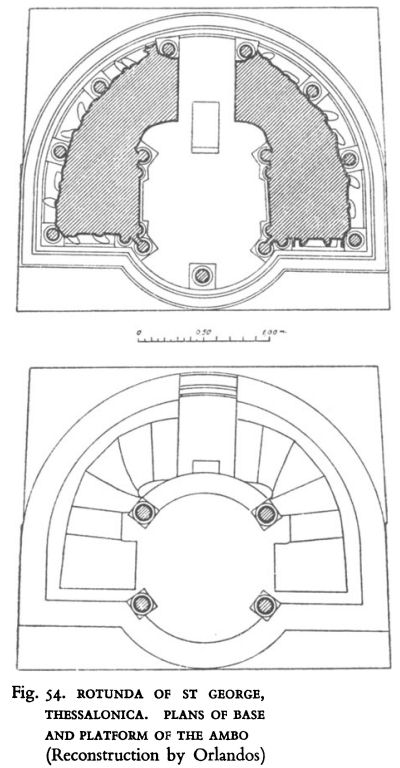

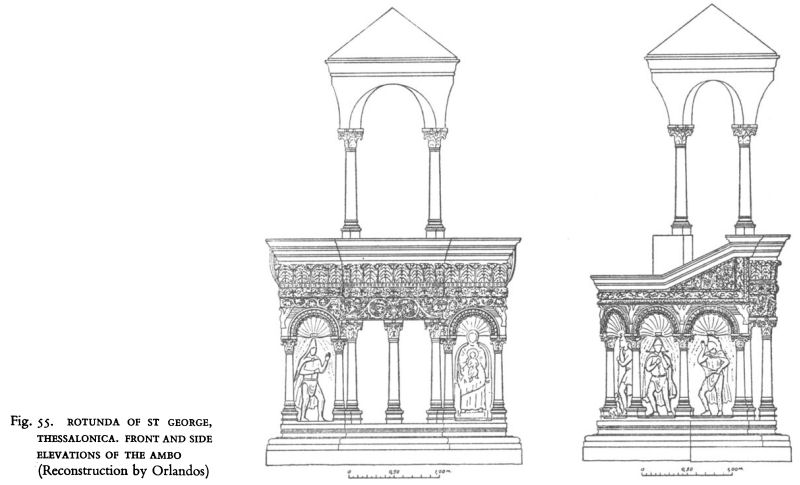

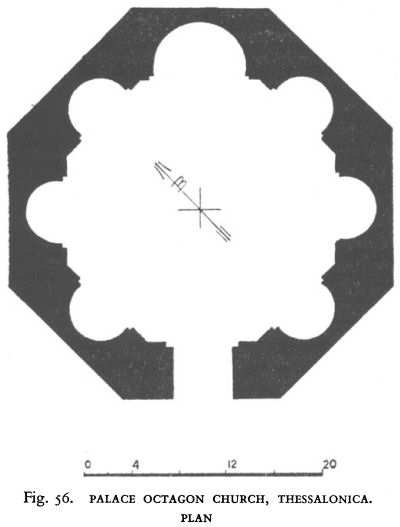

- The Ambo of St George, Thessalonica (Pls. 23, 24) 1214. The Palace Octagon, Thessalonica 123

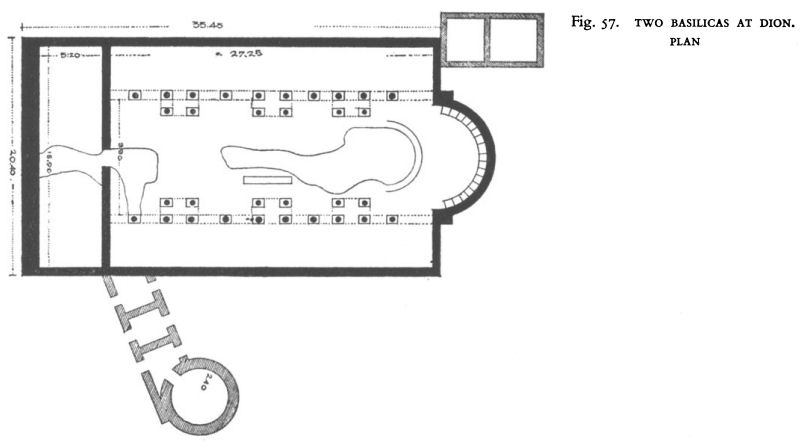

5. The Two Basilicas at Dion 124

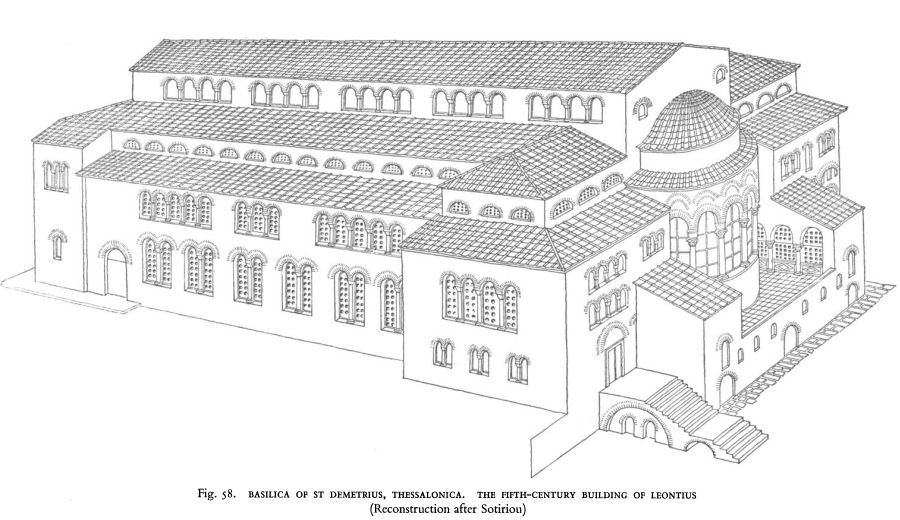

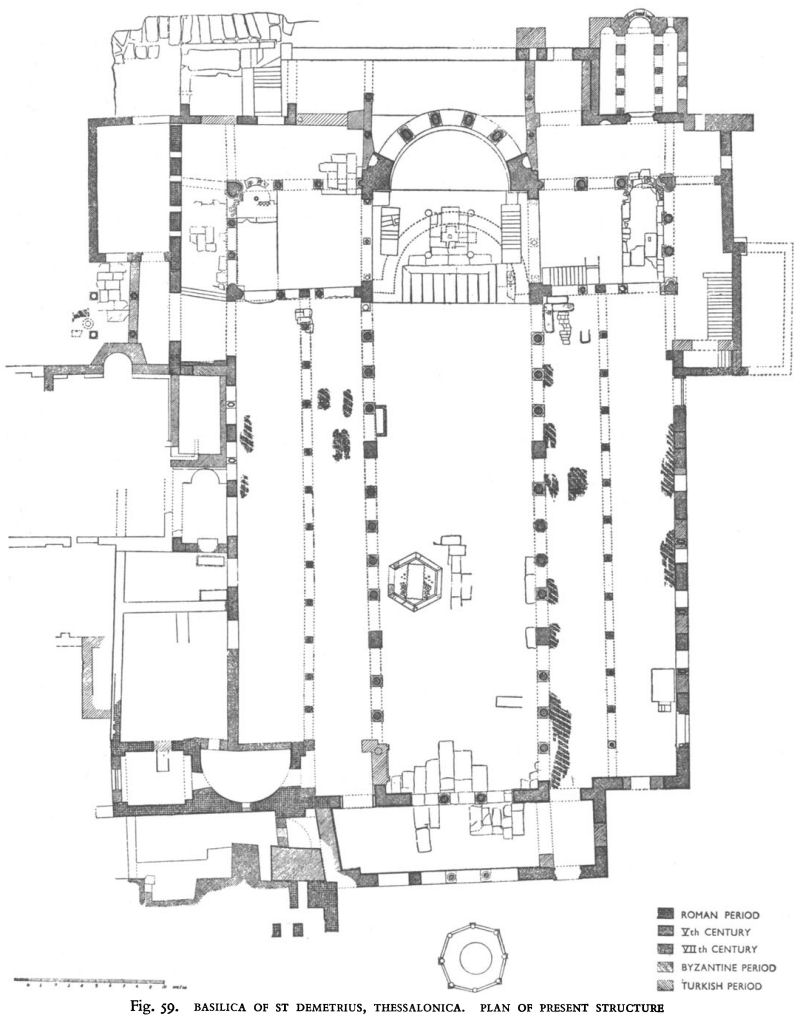

6. The Basilica of St Demetrius, Thessalonica 125

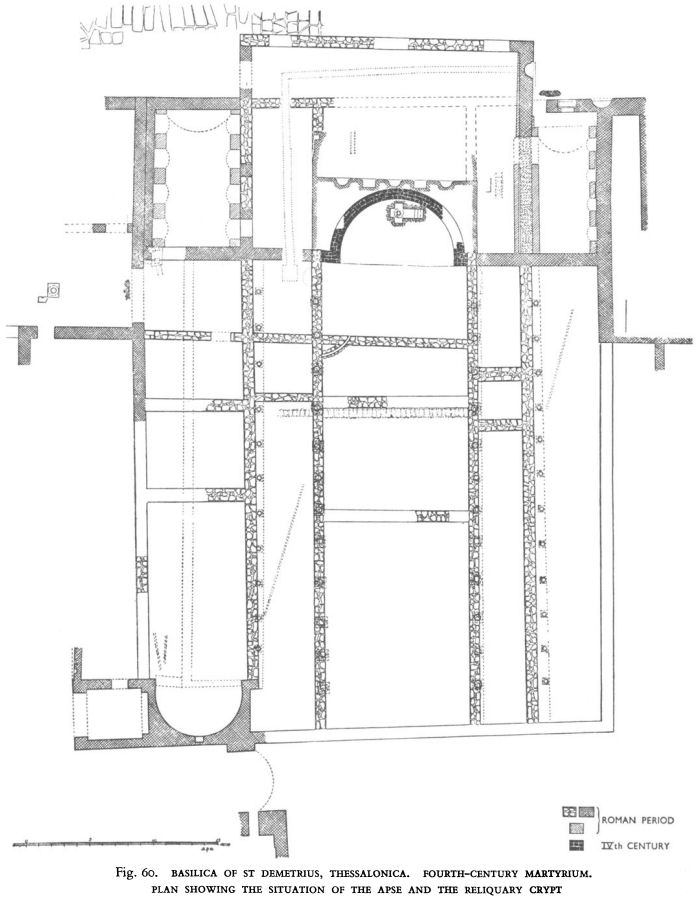

- The Fourth-Century Martyrium 128

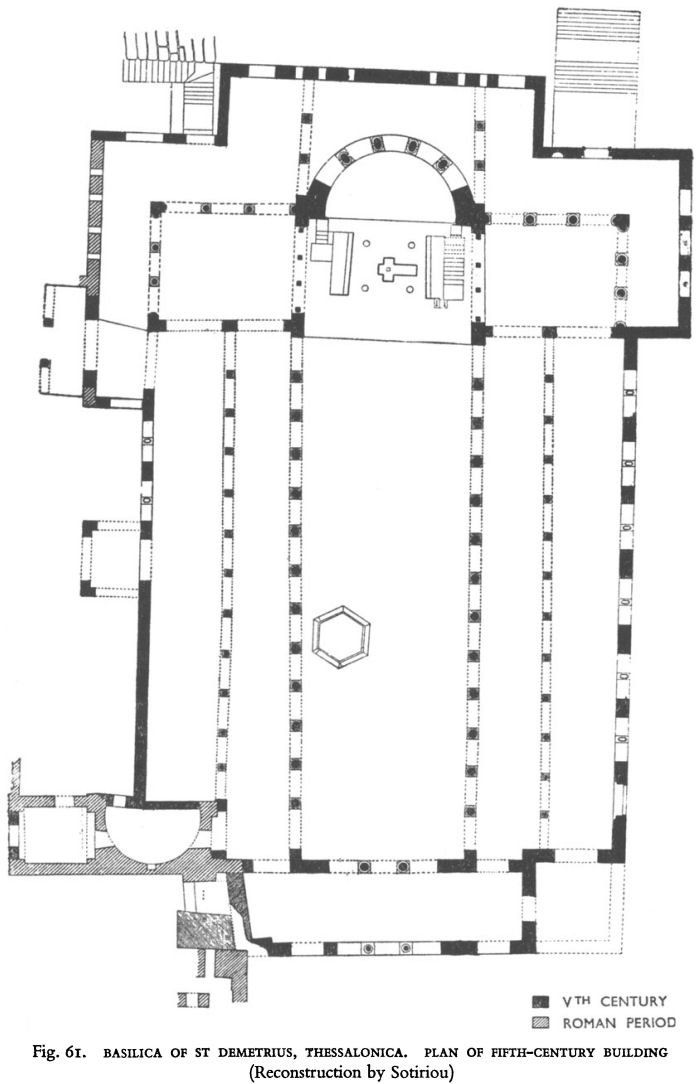

- The Fifth-Century Basilica 130

- The Crypt of St Demetrius 134

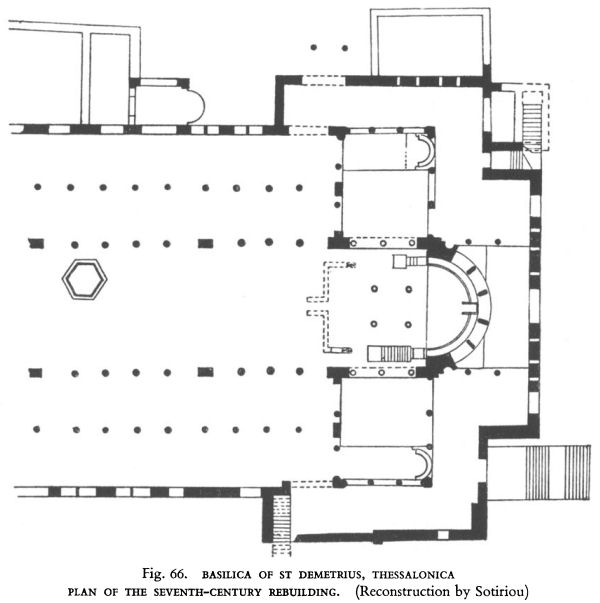

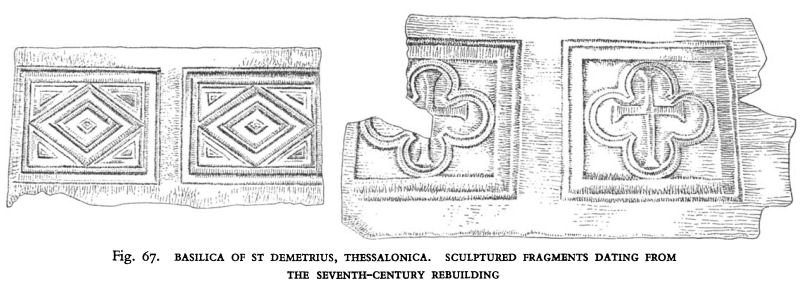

- The Rebuilding of the Seventh Century 137

- The Capitals of St Demetrius (Pls. 27, 28) 139

- The Mosaics of St Demetrius (Pl. 29-34) 141A. St Demetrius and the Angels (Fragment) (Pl. IV)

B. St Demetrius with a Woman and Child (Fragment) (Pl. IV)

C. The Various Scenes on the Arcades of the North Inner Aisle belonging to the Period Prior to the Seventh-Century Fire (destroyed in 1917) (Pls. 29-31)

D. The Medallions of the North Inner Aisle inserted after the seventh-century fire (destroyed in 1917) (Pls. 29h and c)

E. St Demetrius and the Builders (Pl. 32)

F. St Demetrius and a Deacon (Pl. 32)

G. St Demetrius and Two Children (Pl. 33a). St Sergius (Pl. 33 b)

H. The Virgin and St Theodore (Pl. 34)

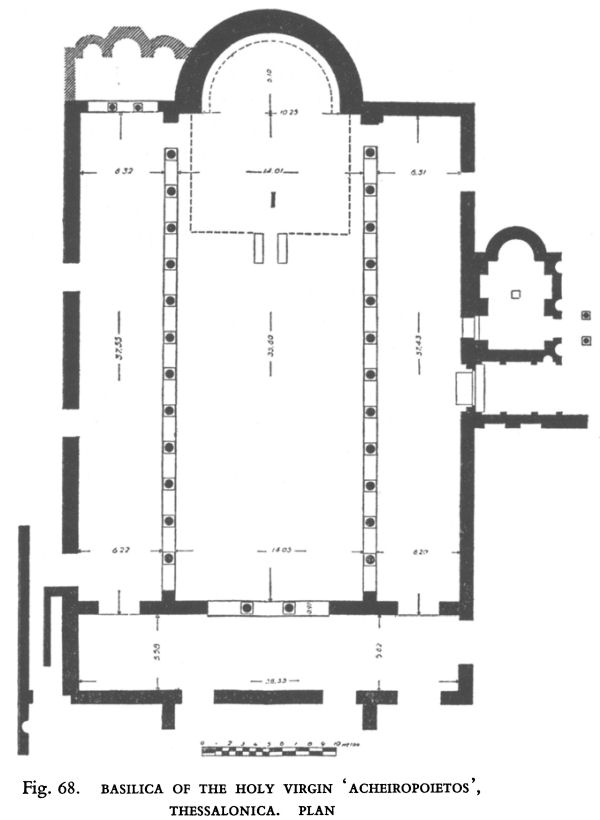

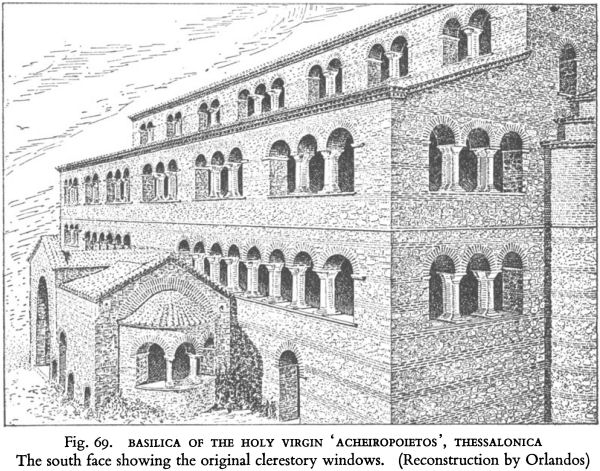

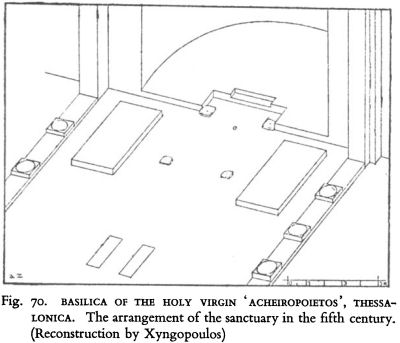

I. St Demetrius and the Four Ecclesiastics (Pl. 33)7. The Basilica of the Holy Virgin ‘ Acheiropoietos’, Thessalonica 155

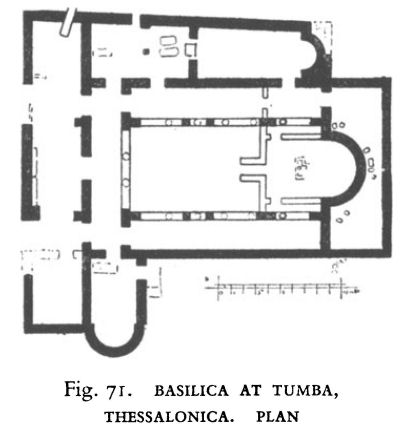

8. The Basilica at Tumba, Thessalonica 158

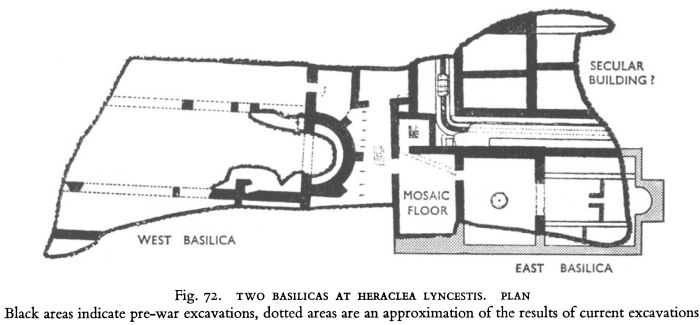

9. The Two Basilicas at Heraclea Lyncestis 159

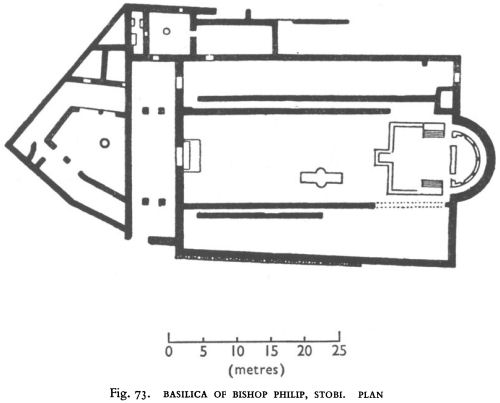

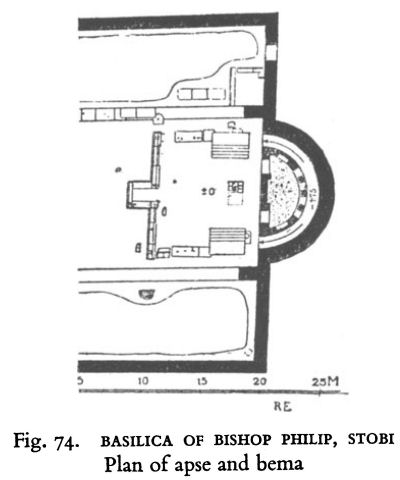

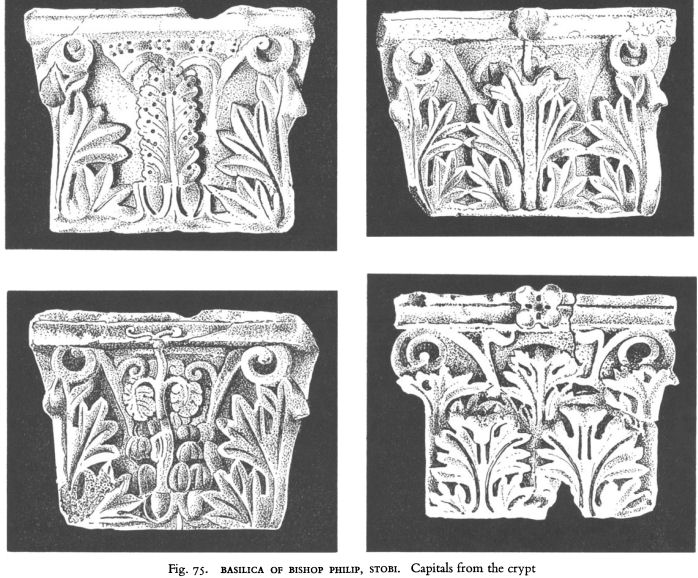

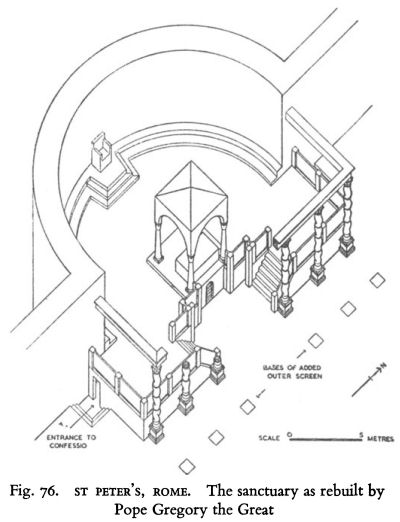

10. The Basilica of Bishop Philip, Stobi 161

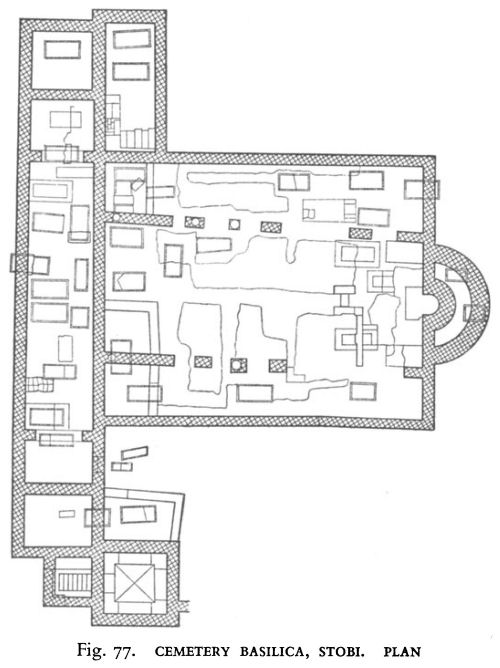

11. The Cemetery Basilica, Stobi 167

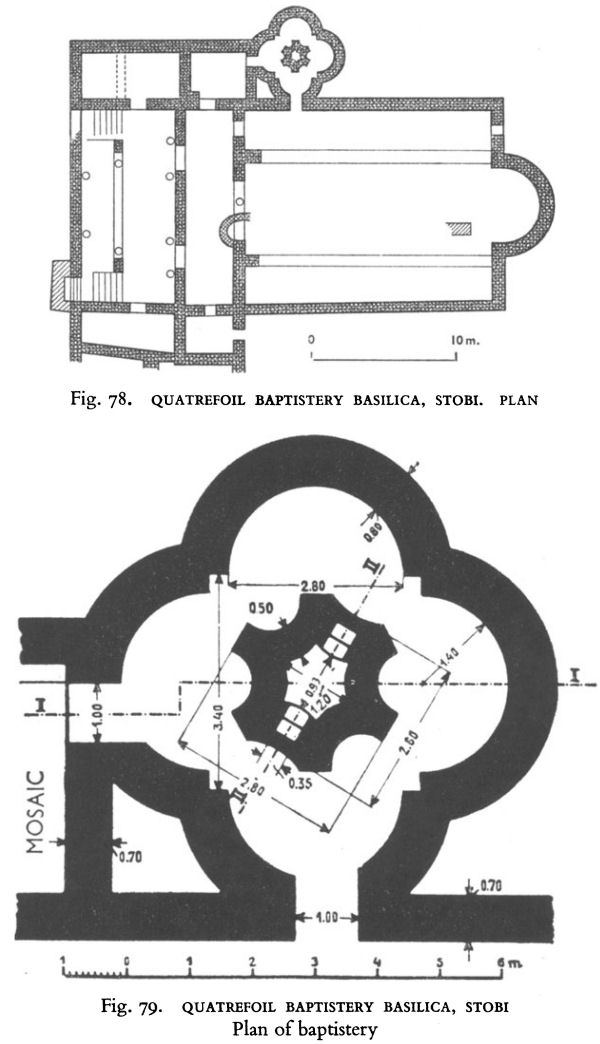

12. The Quatrefoil Baptistery Basilica, Stobi 168

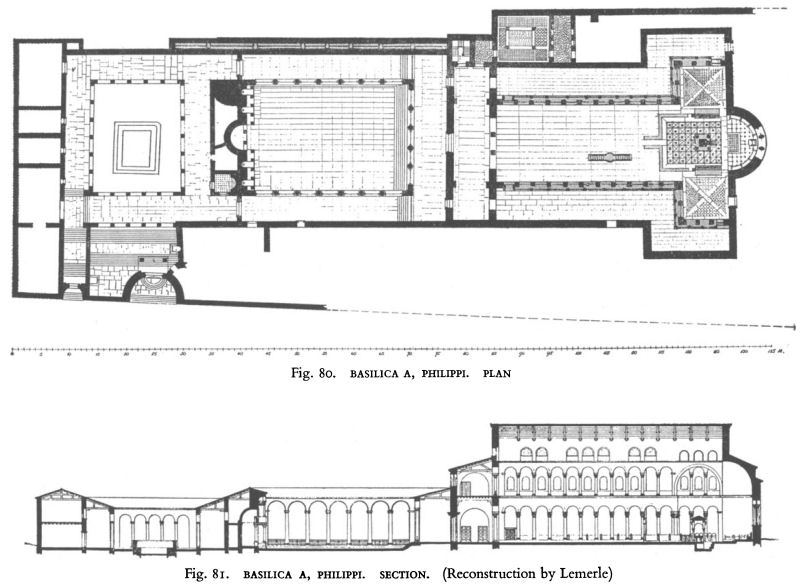

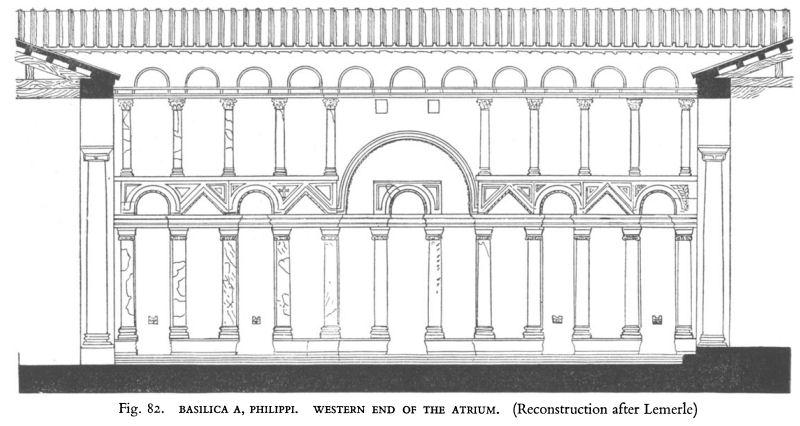

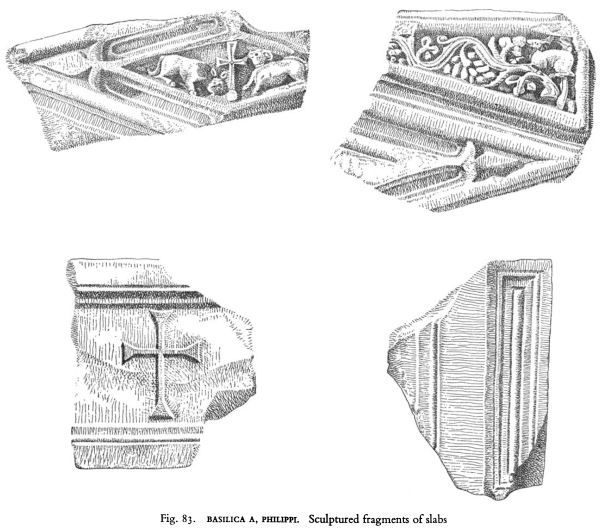

13. The Basilica A, Philippi 169

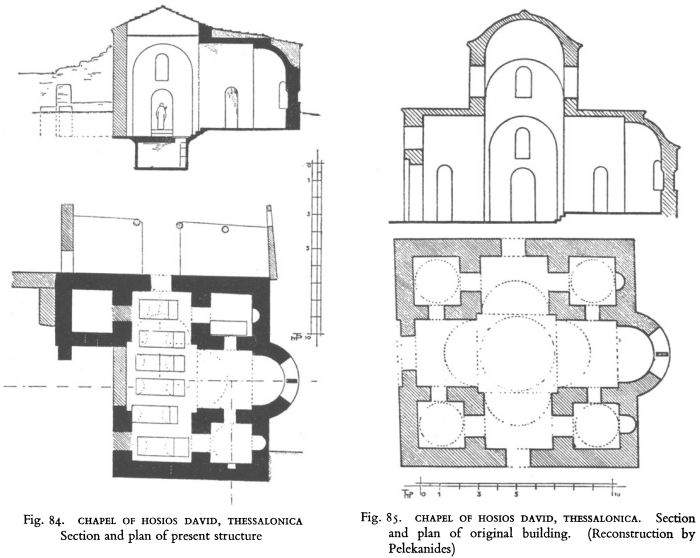

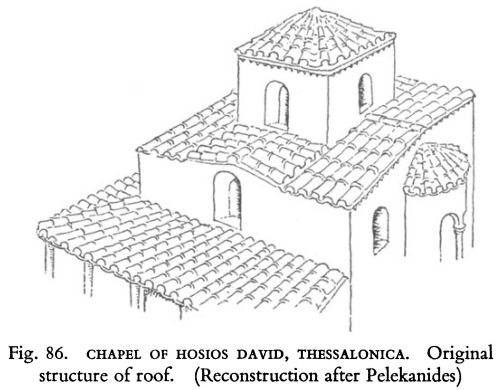

14. The Chapel of Hosios David, Thessalonica 173

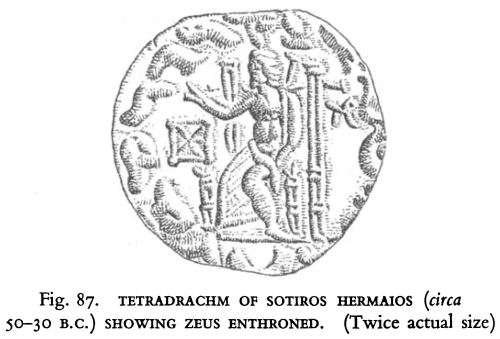

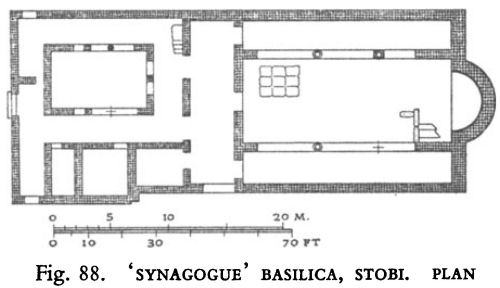

15. The ‘Synagogue’ Basilica, Stobi 179

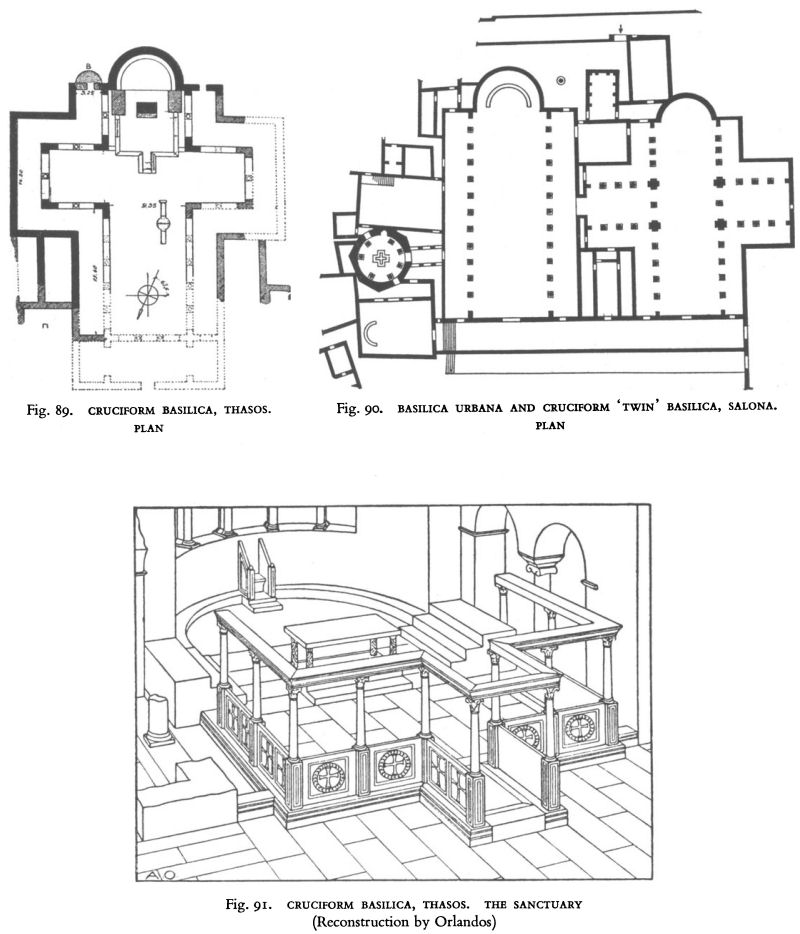

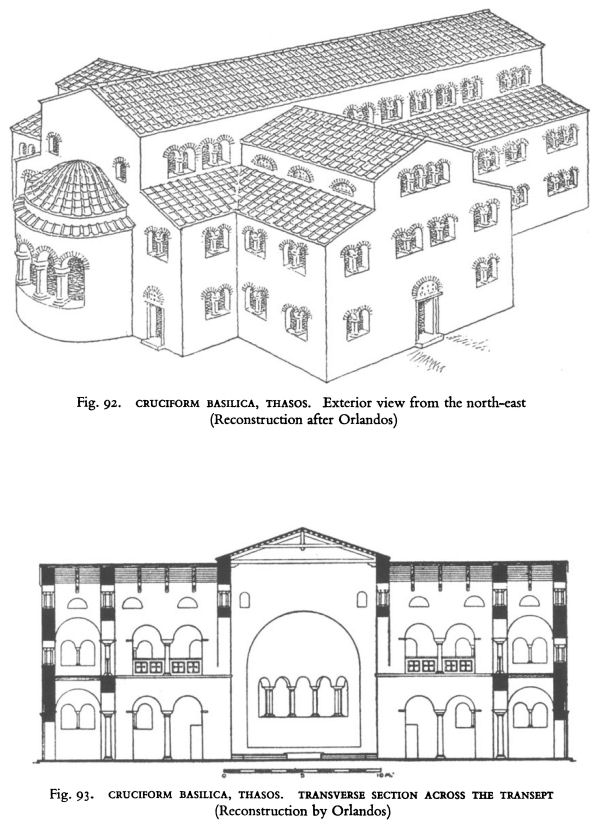

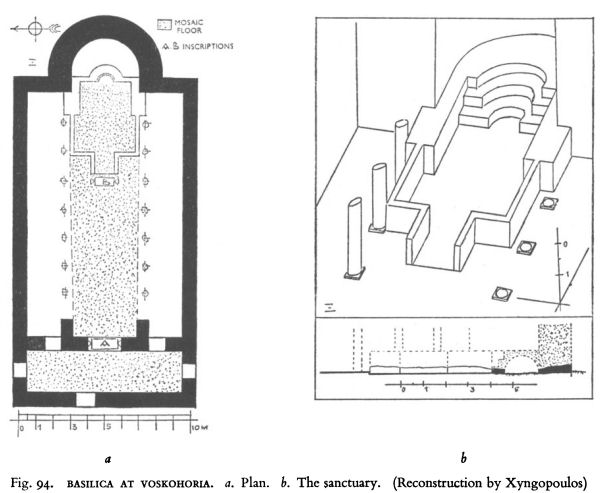

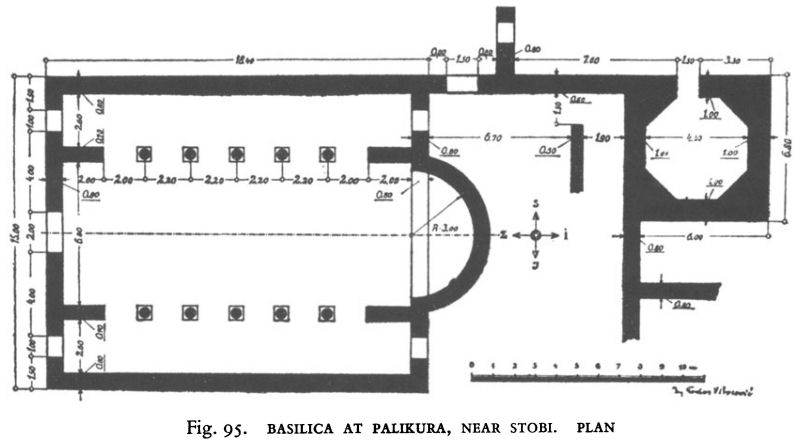

16. The Cruciform Basilica, Thasos 181

CONSTANTINE THE GREAT

(From a marble head found at Niš and now in the National Museum, Belgrade)

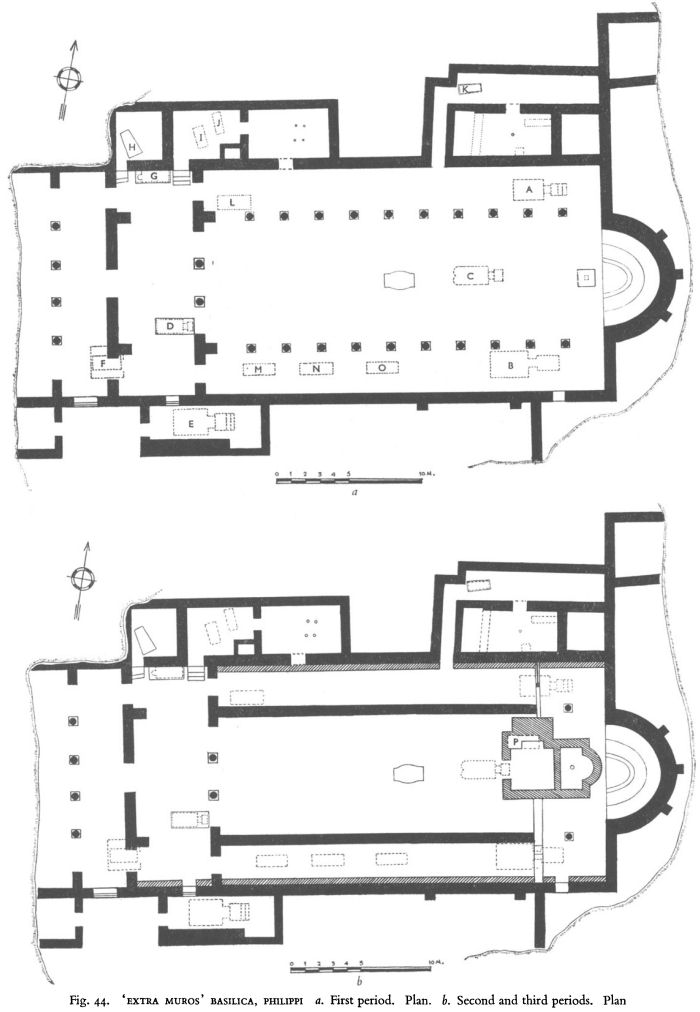

Fig. 44. ‘EXTRA MUROS’ BASILICA, PHILIPPI a. First period. Plan. b. Second and third periods. Plan

Chapter IX. The Monuments — I : Constantine to Justin I

(Early Fourth to Early Sixth Century)

1. THE ‘ EXTRA MUROS ’ BASILICA, PHILIPPI

(Plates II, 10-12)

It is appropriate that this survey of the Early Byzantine churches of Macedonia and the territory extending immediately to its north should start, chronologically and geographically, at Philippi, the first city in Europe to receive the Gospel of Christianity from St Paul. Here, in 1956 and 1957, on a site outside the old walls, a short distance from the Neapolis (Kavalla) gate, Pelekanides discovered and excavated a Christian basilica dating from the first half of the fourth century and probably from the reign of Constantine the Great. [1] One of the oldest churches yet excavated, prior to its discovery the existence of the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica had been unsuspected, no record or indication of it appearing in any documentary source.

The Acts of the Apostles tell us that, after Paul and his companions had spent certain days in Philippi,

‘on the Sabbath we went out of the city by a river side, where prayer was wont to be made ; and we sat down and spake unto the women which resorted thither. And a certain woman named Lydia, a seller of purple of the city of Thyatira, which worshipped God, heard us. . . .’ [2]

Collart, writing in 1937, suggested that the banks of a small river crossing the Via Egnatia two kilometres west of Philippi, which are still a popular walk for the villagers on Sundays and holidays, were the scene of this unpretentious start of Paul’s mission to the Philippians. [3] However, since the draining of the marshes, which formerly covered large areas of the plain, the local topography has been considerably modified and once existent streams and rivers are now either insignificant rivulets or have been drained away altogether. The new discovery of this early church, beside a tiny stream to the east of the city, proposes an alternative to the site put forward by Collart. For it is probable that succeeding generations of Philippian Christians would have kept in sacred memory the place of the apostle’s original ministry to their city and, with the Peace of the Church, would have erected a basilica in commemoration.

Three building phases were identified on the ‘Extra Muros’ site. The second, happening within a century or two of the first, restored the original basilica after it had been damaged by fire, but incorporated certain modifications.

1. S. Pelekanides, Η ΕΞΩ ΤΩΝ ΤΕΙΧΩΝ ΠΑΛΑΙΟΧΡΙΣΤΙΑΝΙΚΗ ΒΑΣΙΛΙΚΗ ΤΩΝ ΦΙΛΙΠΠΩΝ (ΑΡΧΑΙΟΛΟΓΙΚΗ ΕΦΗΜΕΡΙΣ, 1955), (Athens, 1960).

2. Acts xvi, 14.

3. P. Collart, Philippes, ville de Macédoine depuis ses origines jusqu’à la fin de l’époque romaine (Paris, 1937), p. 457 et seq.

99

![]()

In the third phase, which occurred during the mediaeval period, a much smaller and simpler church was erected in the middle of the ruins of its predecessors.

The fourth-century structure was basically a Hellenistic basilica. It had a nave and two aisles, a semicircular apse, galleries, a narthex and an atrium. Porticoes lined the atrium on its north, south and east sides (all trace of the western has disappeared), and three doorways, one sited centrally and two laterally, linked it with the narthex. A tribelon connected the narthex with the nave. Two other entrances, slightly smaller than and asymmetrically placed to those from the atrium, opened into the aisles. Colonnades, without stylobates, and running the entire length of the nave except for short projections from the western wall, marked the division between the nave and aisles. They also served to support the galleries, which were approached by a staircase situated in a small room north of the narthex, to which it was linked by a door at the western end of the joint wall.

The apse, supported by three buttresses, was lit by six windows, placed one to either side of each buttress. A synthronon of three marble-lined steps, each 0.20 metres high and, from the lowest, 0.40, 0.80 and 1.00 metres deep, respectively, provided presbytery seats around the wall of the apse. No signs of an episcopal throne could be observed and Pelekanides concludes that this was probably of wooden construction. A reliquary crypt, 1.40 metres square with a small rectangular hole in its centre, was found beneath the site of the altar. No remnants of an altar were found and only a little earth in the reliquary crypt.

The internal length of the nave and aisles measured 27.50 metres, the width was 15.60 metres. This ratio of approximately 2 : 1 was usual in the Hellenistic type of Early Christian basilica. The aisles, however, were relatively narrow, 3.20 metres from the walls to the axes of the colonnades compared with a similarly calculated nave width of 9.20 metres and a depth of 5.30 metres in the narthex.

A variety of annexes were attached to the north and south walls of the basilica. One group of two rooms was placed immediately east of the room with the staircase. A doorway opened from the narthex into the more westernly of the two which, measuring 4.40 by 3.40 metres, contained a small low-walled structure in its south-east corner. Another doorway led into the second room, 5.60 by 3.40 metres, which had access to the north aisle. In the eastern half of this room the excavators found the broken remains of a marble table-top and four small, slender pillars which had been its supports.

Pelekanides identifies these two rooms as an early form of diaconicon, to which the members of the congregation, entering from the narthex, brought their offerings, perhaps depositing them in or on the low-walled structure in the corner of the first room. The table in the second room, he suggests, was where ‘the priest, sitting with the archdeacon and the readers, inscribes the names of those who make oblations’.

A second group of annexed rooms was excavated at the eastern end of the basilica’s north wall. An entrance from the north aisle led into an L-shaped corridor, 1 metre wide along its western length and 2 metres along its northern. A doorway in the latter opened into a rectangular room, 6.10 by 3.00 metres, paved with tiles, 0.30 metres square. A small, slender, marble pillar, originally the single leg of a small table, was found in situ in its centre. A second room, 2.70 by 2.80 metres, lay to the east of the first, its eastern wall flush with the termination of the north aisle. No trace of a doorway to this room was discovered, and it was not possible to ascertain its purpose.

Pelekanides points out that in spite of the unusual nature of this north-eastern annexe, its proximity to the sanctuary presupposes an important purpose probably connected with the performance of the liturgy, at least at the time of the church’s foundation. The table on the single pillar, in conjunction with the position of this group of rooms, suggests, he says, a prothesis function. Here the prayers may have been recited for living and dead members of the congregation and from here the bread and wine may have been brought to the altar. Consequently, he concludes, we have in this basilica a form of pastophoria annexed to the north wall. Logical as this appears, we must admit that it is outside the normally accepted tradition of Early Christian basilicas in Greece and Macedonia. This, if it does not omit

100

![]()

pastophoria entirely, places them, Syrian fashion, at the basilica’s east end as an integral part of a tripartite sanctuary.

Although Pelekanides confines himself in his excavation report to a factual description and interpretation of the finds, in the several comparisons which he makes between the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica and the early churches of Salona he points towards an explanation of these seemingly anomalous pastophoria. A comparison of the ground plan of the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica with those of the basilica of Manastirine (Fig. 21) and the Basilica Urbana (Fig. 90), both at Salona, show that all three possessed northern annexes, and that in each case one was situated with convenient access to the sanctuary. In the Basilica Urbana, the room immediately north of the apse similarly contained a short single pillar, identified by Dyggve as being the support of a prothesis table. [1]

Salona, it will be remembered, received its Christianity from the great late third and early fourth-century missionary centre of Nisibis in Northern Mesopotamia. The parochial churches of the Tur Abdin in Northern Mesopotamia, ground plans of which are shown in Figure 16, are later foundations than the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica, but unquestionably they reflect the deeply rooted local tradition of ‘the latitudinal chamber, although the nave is actually disposed in the contrary fashion with relation to the apse’. [2] In her description of Mar Aziziel at Kefir Zeh (Fig. 16d) Gertrude Bell remarks that a door in the south side of the apse ‘leads into a small chamber which communicates also with the nave by a narrow door, and communicated with the narthex (along the southern side of the church) by a door now walled up. Above it is an upper chamber, approached by a wooden stair and containing an altar. Another small dark chamber with an altar lies still further to the east.’ [3] Of Mar Kyriakos at Amas (Fig. 16a), she comments : ‘as at Kefr Zeh, a chamber containing an altar lies to the south of the apse, communicating with apse, nave and narthex’. [4] If we simply read ‘prothesis table’ for altar we have the essential features of the north-eastern annexes of both the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica at Philippi and the Basilica Urbana of Salona.

While the Philippian and Salonitan annexes are placed against the northern walls of the churches, in these two Northern Mesopotamian examples the prothesis rooms occupy the south-east corners. Moreover, except for possible anterooms of the prothesis chambers, there appear to be no corresponding spaces for members of the congregation to bring their offerings in accordance with the diaconicon ceremony described by Pelekanides. In fact, the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica with its twin annexed pastophoria conforms more to the ancient Hittite form of the Hilani narthex than do the parochial churches of the Tur Abdin. The latter are, however, somewhat later. It is possible that the churches of the third and fourth centuries possessed such pastophoria. On the other hand, perhaps they were not essential to the Mesopotamian, liturgy. The placing of the prothesis on the northern side of the church — in Salona as well as Philippi — may have been due to the growing influence of Syria, which was developing as an increasingly powerful factor in Christianity during the fourth century.

In view of the powerful foothold known to have been established by Mesopotamian missionaries in Salona during the third century and maintained throughout the fourth, their presence at Philippi, an important city of a region that had long been peculiarly susceptible to Oriental influences, can hardly be surprising. In the Basilica at Tumba in Thessalonica a very similar arrangement of northern annexes was also excavated. Thus there enters a possible Mesopotamian factor into our consideration of Macedonian Christianity’s early history.

On the southern side of the basilica, against the western end of the southern aisle and the narthex, to which it was connected by a doorway, another annexe, 7.75 metres long and of uneven width, was sited over a crypt. The complete structure appears to have been built to serve a single funerary purpose.

1. E. Dyggve, History of Salonitan Christianity (Oslo, 1951), p. 27.

2. G. Bell, ‘Churches and Monasteries of the Tur Abdin and neighbouring districts’ (Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Architektur), (Heidelberg, 1913), p. 84.

3. G. Bell, ‘The Churches and Monasteries of the Tur Abdin’, in M. van Berchem and J. Strzygowski, Amida (Heidelberg, 1910), pp. 246-7.

4. G. Bell, op. cit. (Amida), p. 249.

101

![]()

West of it, along the south side of the atrium, was another annexed room, three metres wide and of unknown length.

Following a fire which caused considerable damage to the upper parts of the basilica, the opportunity was taken to bring it into line with somewhat later liturgical requirements. The free standing colonnades were replaced by pillars standing upon brick stylobates. These stylobates reached a height of 0.65 metres and extended uninterruptedly from the pier projecting from the west wall of the nave to a point 4.50 metres from the east wall. Here a partition, running the full width of the basilica, converted its eastern end into an inscribed sanctuary-transept. Remains of a low screen of marble slabs supported by small pillars were discovered in situ in the north aisle and possibly these were part of the original partition. The building of the later small church over part of the sanctuary and a wall extending from it into the south aisle destroyed all evidence of the central and southern sections. Other additions belonging to the basilica’s second period were seats along the walls of the aisles and the south wall of the narthex. These were 0.45 metres high and constructed of brick. In the north aisle the doorway into the north-eastern annexe was left, but that into the diaconicon was walled up — unless it had been done previously — and the seat continued across it. The diaconicon could now only be entered from the narthex.

The north-eastern or prothesis annexe had nevertheless lost its previously unrestricted access to the nave and sanctuary, for the new, relatively high stylobates and the eastern partition effectively blocked all passage between the nave and aisles. The annexe must, therefore, have ceased to serve a prothesis function. It seems unlikely that this was immediately transferred to one of the newly formed compartments at the eastern ends of the aisles in view of the fact that the tribelon and the narthex entrance from the diaconicon annexe remained. Thus, an Offertory Procession, starting from the diaconicon (now incorporating the functions of pro thesis ?), could have approached the altar by entering the nave through the tribelon. The influence of Nisibis had disappeared — to be replaced by that of Asia Minor, perhaps associated with the Patriarchate of Antioch.

If we compare the arrangement of the rebuilt ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica with that of the great Basilica A (Fig. 80), erected inside the city walls in the fifth century, we find a number of important similarities. Both had the same kind of tripartite sanctuary, that is to say three divisions which, although not structurally separated, were clearly defined. Both had the nave and aisles separated by high stylobates with no intercommunicating openings. Both had a northwestern annexe entered from the narthex. (In the case of Basilica A, this has hitherto been assumed, although with reservations, to have been a baptistery. [1] Both had tribelons and a triple entrance from the atrium into the narthex. Apart from the great scale and magnificence and the T-shaped form of transept of Basilica A, the main difference between the two churches occurred in the height of their stylobates. Those of Basilica A reached 1.70 metres, the height of a man, so that no one in the aisles was permitted a glimpse of the altar. In the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica only physical access was denied.

Inside the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica the decoration appears to have been simple and unassuming, although skilfully and carefully executed. Only some floor mosaics and fragments of sculpture have survived in pieces large enough for study. Nothing of significance has remained from the walls of the nave and aisles which were probably decorated with wall paintings. We have no means of telling whether painting or mosaic was used to ornament the apse.

Slabs of blue schist formed the floor of the aisles but mosaic was used for the nave and narthex. Almost nothing remains of the nave floor beyond small areas discovered at the bases of the north colonnade and the northern sector of the east wall. These revealed bands with a running flower pattern and a spiralling ivy branch bearing leaves in the semicircles formed by the spirals. Of the central motif, of which these fragments formed part of the border, only minute pieces of debris could be found.

The destruction in the narthex was much less, comparatively large areas of the floor surviving in an excellent state of preservation.

1. P. Lemerle, Philippes et la Macédoine orientale (Paris, 1945), pp. 332-44.

102

![]()

It was planned in three zones to correspond with the nave and aisles. The central zone was the most damaged but sufficient of it remained to show that it comprised a series of white tetraphyllia, or four-leaved crosses, edged with blue and set in a red field. The two lateral zones were more complex and were enclosed within borders consisting of three bands — a white, blueedged line, an ‘astragalos’ pattern on a red field and a blue Meander or curving wave design on a white field (Pl. 12b). Inside these borders series of squares enclosed individually patterned tetraphyllia alternating with circles framing various kinds of birds, dolphins and rosettes in the form of double Maltese crosses (Pls. II, 12d). Pelekanides draws attention to the skilful manner in which different colours and sizes of tesserae were used to avoid monotony and, in particular, to express a subtle sense of modelling in the plumage of the birds.

Unless the fire which partially destroyed the first basilica necessitated a major reconstruction in the nave, no alterations to the floor were made during the second building phase. On the other hand, some at least of the wall paintings were replaced by mosaics. Tiny pieces of plaster, to which a few tesserae have remained attached, are all that have survived of these.

Sculpture belonging to the first phase was also re-used in the second, even the bases of the pillars being re-sited on top of the new stylobates. Only one kind of capital was found, an Ionic-impost form with an ivy leaf between a leaf and scroll motif ornamenting its lower part and a Latin cross with splayed arms on the main face of the impost (Pl. 11a). Above these capitals had been an additional plain, abruptly inclined impost.

Part of the base and fragments of marble slabs from the ambo indicate that this possessed a double stair. As no traces of this could be observed Pelekanides concludes that it was probably constructed of wood. The surviving half of one of the marble slabs bears a relief showing a tree, under which a lamb is standing, its head turned to the rear and wearing a collar from which hangs a Latin cross. The shape of this slab indicates that it served as a balustrade of one of the stairs and, consequently, we may assume the presence of a similarly decorated slab correspondingly placed on the opposite side of

the ambo, an arrangement which would leave space for a centre-piece to occupy the curved side of the platform. The evidence of Crypt B, supported by that of the capitals, leads one to think that here was a cross, but this must remain conjecture for no part of the central slab was recovered.

Other pieces of sculpture found on the site included fragments of chancel stylobates and pillars (Pl. 11c, d, e), part of a lintel, decorated with a cross of similar design to those on the capitals, and a marble slab displaying an encircled monogram cross composed by six ivy leaves with, to either side, Latin crosses standing on ivy stems (Pl. 10b). The emphasis upon the ivy leaf as a decorative motif has perhaps a special significance in view of the locality’s earlier association with the Thracian goddess Bendis, to whom in her aspect of goddess of the underworld and immortality the ivy was a sacred attribute.

Sixteen funerary crypts were discovered beneath various parts of the floor. Several of these were constructed within a few decades of the church’s foundation and, with a single, much later exception, all probably belong to its first phase. Five of the earliest, Crypts A-E, were vaulted, the remainder had flat ceilings.

Crypt A (Crypts A-O appear on Fig. 44a, Crypt P on Fig. 44b) lies near the eastern end of the north aisle. A marble slab set into the floor covered three steps leading to a small rectangular opening, 0.50 metres deep, through which the east end of the crypt was entered at a height near the ceiling. The crypt itself measured 2.20 by 1.40 metres and was 1.65 metres high in the centre. A Greek inscription on the face of the floor slab read, ‘ Sleeping place of Paul, presbyter and doctor of the Philippians. Lord Jesus Christ God, Who created out of nothing, in the Day of Judgement remember not my sins and have mercy upon me.’

Crypt B, occupying a corresponding position in the south aisle, was slightly larger, 2.65 by 1.90 metres and 1.84 metres high. A marble slab set in the floor covered a small compartment that provided access, via a short and again small, arched opening, into the eastern end of the crypt, also near the ceiling level. There were no signs of steps to this crypt. The west, north and south walls and the vaulted

103

![]()

ceiling were decorated with paintings of large, thickly leaved wreaths encircling Latin crosses. The cross on the west wall was the most ornate, being blue in colour and embellished with pearls and precious stones (Pl. 12c). Those on the north and south walls had only a pearl decoration and on the ceiling the cross was a plain white. Pelekanides comments that similar crosses have been discovered in ancient Christian graves in Thessalonica and that such wreaths appear in a Salonitan crypt. Two skeletons were found inside and an inscription on the covering slab read, ‘Sleeping place of the most pious presbyters Faustinus and Donatus of the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church of the Philippians’.

The discovery of coins of Constantinus II (337—361) in the earth beneath the floor slab has particular importance in establishing the approximate date of the construction of this basilica. Together with the fact that the crypt was later than the basilica and was constructed to contain the remains of two of its presbyters, it indicates about the middle of the fourth century as the latest possible period for the foundation of the church.

Crypt C, sited on the axis of the nave, lay slightly to the west of A and B, far enough to have been beyond the sanctuary. Slightly smaller than Crypt B and possessing a similar entrance, it was distinguished by a double apse at its western end. A large number of skeletons were found inside and eighteen skulls were counted in the two apses. A Greek inscription reading, ‘ Sleeping place of the God-protected priests Gourasius and Constantius who died in Christ in the fourteenth indictio’, points to the conclusion that it was probably a privileged funerary crypt for priests attached to the church.

Crypt D was situated in the narthex near the southern opening of the tribelon. Smaller than, but otherwise similarly planned to Crypt B, its walls were lined with carefully laid marble slabs. Another marble slab over the opening in the floor, inserted to replace the original mosaic, had carved upon it a Greek inscription reading, ‘Here lies Andrew, called Comitas, the faithful tribunus notariorum, who was famous for his stature and beauty and much nobility was about him and he died at eighteen years on the first month day’. The exact meaning of the final phrase is unclear, but the office of tribunus notariorum was extremely high and Pelekanides suggests that this, coupled with the apparent youth of the deceased and the reference to much nobility, may imply a relationship with the imperial family.

Crypt E was situated in the southern annexe adjoining the narthex and the western end of the south aisle. Following the plan of Crypt A, three steps descended to a small compartment and short passage which opened into the vaulted crypt, 2.38 by 1.86 metres and 1*89 metres high in the centre. Fragmentary remains of wall paintings indicate that originally these probably covered all the walls. A few strands of gold thread were also discovered, showing that the deceased must have been laid to rest in a gold-embroidered garment. It seems likely that this whole annexe was built as a two-storied funerary chamber.

The remaining early crypts require little mention. Crypt F contained a re-used marble sarcophagus, a form of coffin most unusual in a crypt. Crypt G, at the north end of the narthex, is noteworthy for its Greek inscription which reads, ‘Sleeping place of Paul, priest of God’s Holy Church of the Philippians. And anyone who, after my burial, attempts to put here another dead person will be accountable to God ; because this is a “monosomon” (grave for a single person) of a high priest.’ Crypt H has a short Latin inscription ; one other funerary inscription in Latin was also found elsewhere in the basilica. These two inscriptions are additional evidence of the basilica’s foundation in the first half of the fourth century, a period which saw Greek oust Latin as the language of Philippi. A Greek inscription belonging to Crypt I referred to the deceased (as did that of Crypt H) as belonging to a ‘committee’. Crypt K, in the passage of the north-eastern annexe, was notable for containing coins of Arcadius (395-408).

No evidence of a baptistery was discovered. Pelekanides comments that the practice of baptism in a running stream, as John the Baptist had baptised Christ, and Paul, presumably, had baptised Lydia and her family, probably persisted in memory if not in practice into early fourth-century Philippi. Use of a baptismal chamber had been, at least in part, a device to evade the persecution which would have resulted from a public ceremony.

104

![]()

Particularly if the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica had been erected upon the traditional site of Paul’s first conversions among the Philippians, it would have been a natural reaction immediately after the Peace of the Church to have adopted the practice of John and Paul rather than to have continued with an artificial substitute.

This absence of a baptistery is, as Pelekanides remarks, an argument in favour of a Constantinian date for the foundation of the church rather than one in the mid-fourth century. The selection of a site outside the city walls could also be adduced in support of a date preceding an official status for Christianity, but such a choice is more likely to have been the consequence of the traditional sanctity of the site, although this factor is conjecture and not an established fact. Certainly, however, the Philippian Christians who built the church were neither particularly numerous, wealthy nor influential. It was small and many of the materials were taken from earlier, pagan buildings. Such a state of affairs tallies with conditions shortly after the Peace of the Church and before 324, when Christianity was declared by Constantine to be the state religion, rather than with the middle decade of the fourth century when even the inherent strength of Philippian paganism could hardly have stood in the way of a more splendid building.

The first ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica appears to have lasted into the reign of Theodosius II (408-450), for coins of this emperor were found in parts which remained unreconstructed but which were covered by additions or repairs belonging to the second phase. The next evidence of a numismatical nature comes from coins of the early years of Justinian I (527-565) discovered in the new brick stylobate dividing the nave from the north aisle. The inference that the partial destruction by fire and the subsequent rebuilding occurred during the latter half of the fifth century and the first three decades of the sixth is supported by the architectural and historical evidence. More precisely, Pelekanides points out that the date of the burning was probably 473, when Theodoric Strabo unsuccessfully attacked Philippi and ‘burned up what was outside the city but did no other harm’.

If this date is correct and if we may rely upon the evidence of the Justinian coins, more than half a century elapsed before the church was reconstructed, although temporary repairs possibly enabled it to continue in use in so far as the general state of insecurity permitted. Probably the reconstruction was an early result of Justinian’s firm measures to defend the Balkans against the Slav, Avar and Bulgar invaders. This view is supported by the fact that the second phase reflects none of the new ideas gaining strength in Constantinople, although these were to appear in a tentative manner soon afterwards at Philippi in Basilica B. On the contrary, it followed with striking fidelity the lines of Basilica A, probably erected a little less than a century before and, we surmise, destroyed by the earthquake of 518. It is, however, interesting to note that Basilica B (Fig. 97), probably started shortly before the middle of the sixth century and perhaps intended as the successor of Basilica A, also retained the principle of an inscribed eastern transept by making the stylobates and colonnades of the nave turn outwards before reaching the east wall of the basilica.

The next and last piece of numismatical evidence is a coin of Leo VI (886-912). It was found in Crypt P, a grave that extended beneath the sanctuary (Fig. 44b). This situation and the fact that its walls were built of broken pieces taken from the main building, including the threshold, jambs and lintels of what had probably been the main doorway, show clearly that by the end of the ninth or the beginning of the tenth century the basilica no longer existed. Which of the many Slav, Avar and Bulgar raids and invasions of the sixth, seventh and eighth centuries was responsible for the final destruction is impossible to say with certainty, but Pelekanides argues convincingly for the second of the two Bulgar invasions of the first half of the ninth century, when, in 812 and 837, they occupied Philippi. The siting of a grave so that it impinged upon the area of the bema suggests that several decades at least must have elapsed since the church’s destruction, long enough for the ruins to have lost the distinctive character of their various divisions, but before the traditional sanctity and associations of the site had become dim. A Bulgar inscription of 837 found among the ruins of Basilica B (see p. 193) certainly provides a degree of circumstantial support for this view.

105

![]()

The third and final phase of the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica was a small single-naved church with a rounded, protruding apse (Fig. 44). It was situated in the bema of the old basilica and the line of its north wall required considerable modification because of Crypt P which lay beneath. The walls were built from various parts of the earlier building, including pillars, bases, capitals, stylobates and marble slabs. A small pillar served as the base of the altar. Built presumably when security, although neither prosperity nor fame, had returned to Philippi, it maintained pathetically and humbly the proud apostolic tradition of the site — until the period of Turkish domination, when the region became inhabited by a solely Moslem population, and the church and the local Christian traditions passed into oblivion.

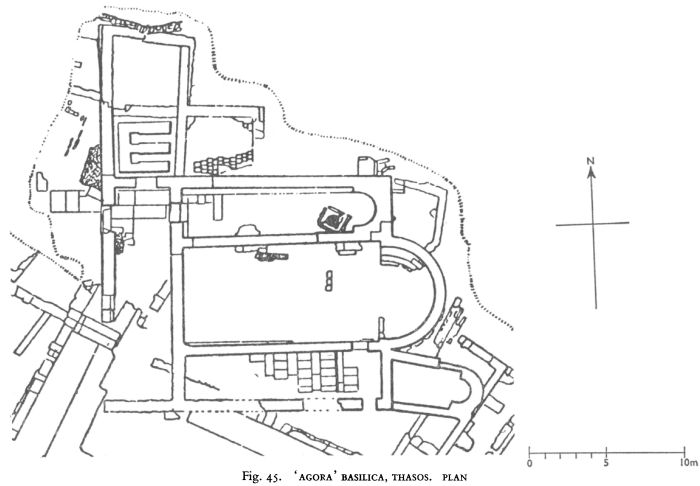

2. THE ‘AGORA’ BASILICA, THASOS (Pl. 13)

Remains of a small early-Christian basilica were discovered in 1949 in the north-east part of the agora of the ancient city of Thasos, on the island of the same name. This church probably dates back to some time during the fourth century, although between its foundation and the end of the seventh century it underwent considerable changes. [1]

The structural elements of the original basilica consisted of a nave, approximately 13 metres long and 6.65 metres wide; two aisles, each 2.70 metres wide; a narthex, 3.50 metres deep; and a semicircular apse that was 5.70 metres in diameter. The full length, including the exterior walls, was about 21 metres. The excavators have shown that one of the post-fourth-century alterations was the raising of the level of the floor. This fact needs to be remembered when viewing the ruins to-day, since both early and later stages exist side by side.

Fig. 45. ‘AGORA’ BASILICA, THASOS. PLAN

1. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique, lxxv (Paris, 1951 ), pp. 154-64; X. I. Macaronas, Archaeological Reports, ΜΑΚΕΔΟΝΙΚΑ (1941-52), vol. 2 (Thessalonica, 1953), pp. 667-8 (Greek).

106

![]()

The fourth-century church was paved with white marble slabs, apparently taken from nearby buildings, which seem to have been the principal source of building materials. Columns, about 2.10 metres or so high, on bases, stood on stylobates of stone or rubble, which were 0.45 metres high. These stylobates ended 0.65 metres from the east wall to allow access between the aisles and the nave. The bases of the pillars, two discs on a rectangular slab, were grooved as if to carry parapet slabs. A bench of rubble covered with plaster ran along the north wall of the north aisle and at its west end on either side of the doorway into the narthex.

The north aisle also had a door at its eastern end, and close to this, a large well. The south aisle had a door at the eastern end of its outer wall. The western entrances into the church from the outside were complicated by the presence of earlier buildings. Besides a doorway at the north end of the narthex, another was placed at the northern end of the west wall. This was slightly wider than that leading from the narthex into the north aisle (1.25 and 1.05 metres respectively) and was situated asymmetrically opposite it. A second western entrance into the narthex occupied a position a little to the south of the church’s axis. Beyond this another building obstructed convenient access.

Nothing remains of whatever entrance led from the narthex into the nave, nor from the narthex into the south aisle.

Three concentric steps, forming presbytery seats, back on to the semicircular wall of the apse. Only those in the northern part exist to-day, the others were probably destroyed about the end of the last century when a well was dug there. To the west these seats end in huge stone slabs taken from some old building, possibly an indication that the sanctuary did not extend into the nave. No traces of a chancel screen have been found in this part of the church. A silver reliquary is said to have been discovered and surreptitiously removed during the sinking of the well, but a search for the reliquary crypt which would have contained it yielded no results.

Half-way along the nave, near the northern stylobate, a tomb containing the skeleton of a man had been inserted below the surface of the floor and covered with five irregularly shaped marble slabs. While probably later than the original building, it is clear that this tomb belonged to an early phase of the church when the floor was at its lower level.

Also constructed at some date subsequent to the foundation of the church was an E-shaped hypogeum or crypt outside the north door of the narthex. The three sections of this triple crypt are each two metres long and 0.81 metres wide. The walls of marble and gneiss blocks are covered with greyish-brown plaster, on which appear jewelled Latin crosses with small round pendants at the ends of each horizontal arm. On the cross at the head of the central compartment was an inscription in black paint reading: ‘ΑΚΑΚΙΟΥ ΜΑΡΤΥΡΟΣ’ — ‘Akakios Martyr’.

The crypt was covered by marble slabs, apparently either taken from the chancel screen or from the parapets of the nave colonnades. They are solid pieces; one is ornamented with a Greek cross inscribed in a circle. Above these slabs the whole area covering the crypt was decorated with a rough mosaic consisting mostly of large white marble pebbles, but with a border of ivy leaves formed by pieces of blue slate.

Two rectangular enclosures, one to the east and one to the north, opened on to this mosaic floor. Other rooms appear to have existed to the west of the crypt.

Inside the narthex, on the red cement floor near the north door, a basket or sack was outlined with small white pebbles against a background of diamond-shaped lozenges with single pebbles in their centres. With this was an inscription reading : ‘ ΥΠΕΡ ΕΥΧΗΣ ΑΚΑΚΙΟΥ’ — ‘for the prayer of Akakios’.

The excavators point out that the style of the mosaic and the form of the letters of the inscription, as well as the type of jewelled crosses painted on the walls of the crypt, indicate a fifth-century date for the martyrium. The fact that this structure was later than the church is, therefore, a strong argument in favour of the latter’s fourth-century foundation. This dating is also supported by the evidence of the slabs. It is tempting, although not certain, the excavators add, to see this church as the one mentioned by Gregory of Nazianius, in connection with which a Thasian priest was entrusted with a mission to Constantinople in

107

![]()

order to buy marble slabs from the Proconnesus quarries, a mission for which, alas, he proved unworthy, spending the money in the capital on other, unspecified purposes.

Probably towards the end of the sixth century, perhaps at the same time as the raising of the floor, a prothesis chamber was constructed in the north aisle by blocking the east door and building in its place an inscribed apse. A diaconicon chamber, with a protruding semicircular apse, was built as a slanting projection from the east end of the south aisle. The new floor reached to the top of the stylobates and the presbytery seats, thus obliterating both these early features.

Whether Akakios was a local martyr or whether the martyrium held relics brought from another centre, remains an unsolved mystery. The name was not uncommon, but no known text mentions an Akakios who died for this faith in Thasos. Of those with this name who were martyred elsewhere, the excavators incline towards a Cappadocian soldier who was beheaded in Constantinople in 303. His cult was the most popular of all the saints bearing this name. Moreover, in the Synaxary of Constantinople is a mention of the relics of three saints — one a woman, one called Markos (possibly a mistake for Akakios ?) and one neither described nor named — being transported from Constantinople to Thasos, an incident which could provide a likely explanation for the triple form of the martyrium.

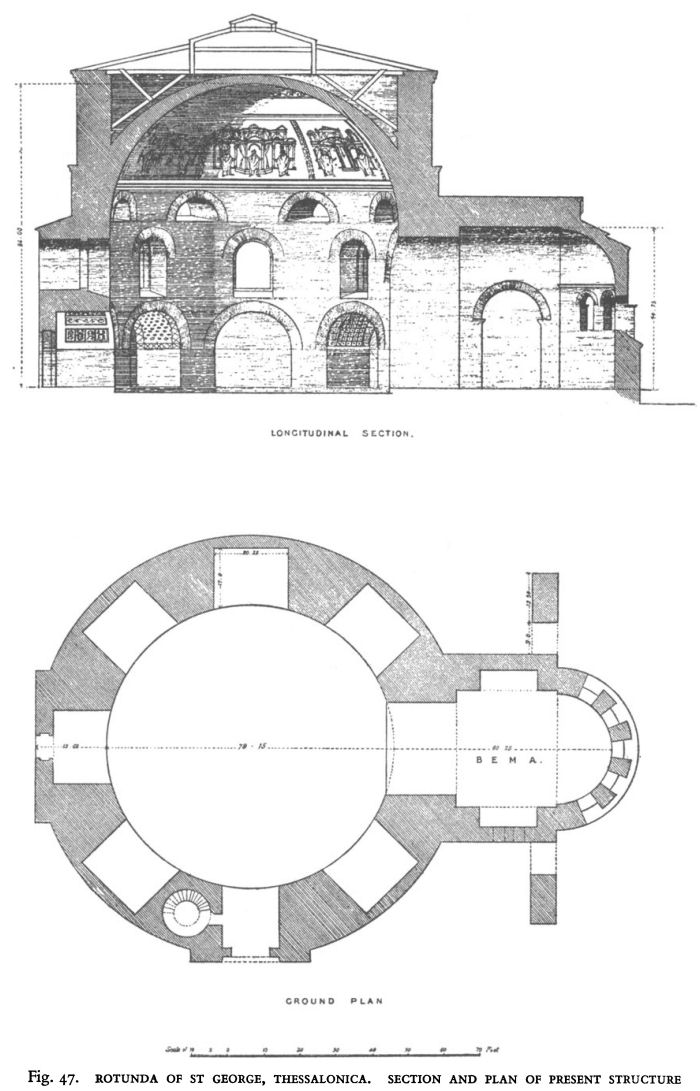

3. THE ROTUNDA OF ST GEORGE, THESSALONICA (Pls. III, 14-24)

- The Martyr Saints in the Dome of St George 112

- The Architectural Compositions in the Dome of St George 113

- The Ambo of St George, Thessalonica (Pls. 23, 24) 121

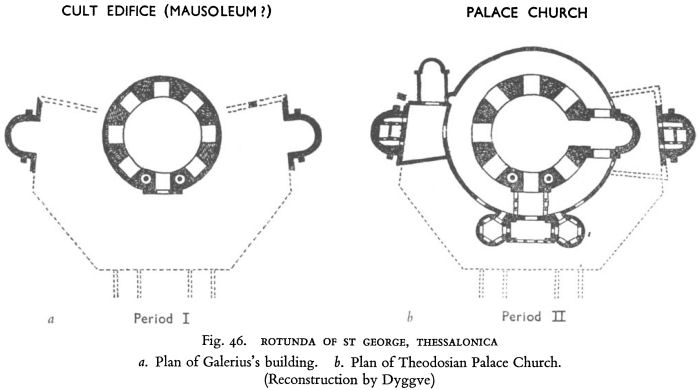

The Rotunda of St George, Thessalonica, was built by Galerius (died 311), and may have been intended by him to be his mausoleum. It was converted into a Christian church during the reign of Theodosius the Great (379-95), [1] that is to say, coincident with the important resurgence of Christianity in Thessalonica which had followed Theodosius’s conversion by Acholius and the subsequent imperial decree establishing Christianity, Orthodox Christianity specifically, as the only legally tolerated religion within the Empire.

Doubt has been expressed as to whether the church was originally named after St George. The sources are silent on the point, but in early Byzantine times the episcopal church of Thessalonica was reputed to be a large building, dedicated to the Holy Archangels or Asomati, in the same quarter of the city. No indication, however, has been noted near St George of an annexed baptistery, which would have been essential to the official church of a bishop. On the other hand, the newly discovered Palace Octagon Church possesses this very feature. Unlike St Demetrius, whose cult was already established, St George was unconnected with the city. However, although the latter’s prominent place in Western hagiography was only achieved after many centuries, he is shown on a fifthor sixthcentury icon of Sinai with the Virgin and Child and St Theodore. Thessalonica’s close association with Syria and Egypt in the fourth century may well have resulted in the dedication of the Rotunda to this eastern saint, although recently a new theory has been propounded that it was originally dedicated to Christ under the name ‘Dynamis Theos’. [2]

Sometime after the capture of Thessalonica by the Turks — between 1430 and the end of the sixteenth century—the Rotunda was transformed into a mosque. It is now a museum for Christian antiquities.

A considerable effort of the imagination is required to-day to visualise Galerius’s building in its original, early fourth-century setting. From its southern portico, a colonnaded avenue led to the emperor’s great Triumphal Arch, beneath which it intersected one of the city’s main streets and then continued south between the Hippodrome to its east and Galerius’s palace to its west. During the Theodosian alterations the confines of the Rotunda appear to have been enlarged and the church made the centre-piece of a great complex of ecclesiastical buildings (Fig. 46b).

It is difficult to say whether Galerius’s Rotunda was

1. H. Torp, ‘Quelques Remarques sur les mosaïques de l’église Saint-Georges à Thessalonique Acts of the IXth International Byzantine Congress, Thessalonica, 1953 (Athens, 1955), vol. i, pp. 489-98.

2. A. M. Amman, ‘Le Titre primitif de l’église de Saint-George à Salonique’, Acts of the Xth International Byzantine Congress, Istanbul, 1953 (Istanbul, 1957).

108

![]()

inspired by Roman models, such as the Pantheon in Rome and Diocletian’s mausoleum in Split, or by buildings encountered during his eastern campaigns in lands where circular structures had long been the appropriate and sacred form for temples and mausolea. Most probably East and West jointly and indivisibly contributed. In its building methods, however, the Rotunda is unquestionably Oriental. Instead of using concrete, as had been the practice in Rome for the past two and a half centuries, particularly for vaulting, the architect relied upon principles of Asiatic origin which had only appeared in the eastern Mediterranean during the second and third centuries a.d.

Fundamentally, the building’s plan is of extreme simplicity, a cylinder supporting a semicircular dome. The walls, 6.3 metres thick as far as the base of the dome, are pierced by eight bays. Brick is the material of construction throughout — for the thin dome, for the barrel-vaulting of the bays, and for the walls, which are filled with mortared rubblework bound with brick courses. The outside walls are continued, though considerably thinner, above the base of the dome to support the beams and rafters of the low pitched roof protecting the light and comparatively fragile dome. A protective timber roof over a vault was to become a common feature of Western mediaeval church architecture, but Galerius’s Rotunda and, later in the same century, the mausoleum of Sta Costanza in Rome, are two of the earliest known European examples of the practice.

During the conversion of the Rotunda into a church one important and permanent structural addition was made, the eastern bay being extended to form an oblong, apsidal-ended sanctuary. A second addition, since dismantled, was an ambulatory encircling the outside of the church and opening into each of the remaining seven bays. At the same time, the great dome, the ceilings of the bays and the apse were richly decorated with mosaics.

Excavations have also revealed that the church once possessed a towered portico at the south entrance, but it is uncertain whether this was part of Galerius’s original structure. If so, it would have provided another parallel with the Pantheon in Rome. The portico opened upon the colonnaded road leading towards the Triumphal Arch. Discussing the church’s entrances, Tafrali writes :

The monument was entered from two sides, the west and the south. In front of the doors were porches of later date than the building, porches which still existed in the tenth century. But once there must have been a third entrance on the north side, corresponding to that on the south,

Fig. 46. ROTUNDA OF ST GEORGE, THESSALONICA

a. Plan of Galerius’s building, b. Plan of Theodosian Palace Church. (Reconstruction by Dyggve)

109

![]()

Fig. 47. ROTUNDA OF ST GEORGE, THESSALONICA. SECTION AND PLAN OF PRESENT STRUCTURE

110

![]()

and which was later blocked up. By means of their porches, these three entrances and the bema which similarly protruded from the building’s circumference, formed the four branches of a cross ; their disposition proves the intention of the restorer to give the building . . . the form of a cross. In front of the church is the fountain surrounded by several columns of green stone from Thessaly. In the open space before the church one still saw in the eighteenth century an underground chamber, the purpose of which we are ignorant and which has since completely disappeared. [1]

Impressive now, in its original state, the mosaic decoration of the dome, the vaulted bays and the apse must have presented a profoundly stirring sight to the Christian worshipper ; and the Thessalonians were a people whose religious emotions were not difficult to arouse. The vaulted ceilings of the bays, extending almost the full depth of the walls, were richly ornamented with mosaics showing birds and fruit and geometric designs. The decoration of the dome, estimated by Texier and Pullan [2] to have used more than thirtysix million tesserae, comprised three zones, the middle one now almost entirely missing.

The lowest zone consisted of eight panels, regularly spaced on the sixty-five and a half metre circumference of the base of the dome. Seven have wholly or partially survived, the missing panel being situated above the opening leading to the apse. These seven remaining mosaics are among the greatest extant examples of early Byzantine art. Each presents two or sometimes three saints, chosen with regard to the calendar — the months of their festival being given with the saint’s name and description — as well as for their qualities of intercession. They stand, their hands raised in the position of prayer, in front of sumptuously embellished architectural compositions, of which there are four versions, each appearing twice. These compositions rise behind the saints in a manner reminiscent of the ornate and formal architectural backgrounds or scenae frons of Hellenistic and Roman theatres. Each panel is separated from the next by a stylised representation of the Tree of Life.

Traces of sandalled feet are all that remain of the middle zone to indicate that here were probably to be seen the apostles. In the apex of the dome, encircled in a wreath of foliage and fruits held by four archangels, was the figure of Christ. Unfortunately, nothing has survived of the mosaics in the apse, and our knowledge of them is limited to Colonel Leake’s tantalising comment that the Turks had not destroyed ‘a figure of the Almighty, which occupied a niche opposite to the door’, [3] and even this may have referred to a wall painting of much later date which restoration work has recently uncovered.

To appreciate the meaning and the intended effect of the surviving panels and the decorative patterns of the bays we must regard them, to the best of our ability, through the fervent, more or less unsophisticated eyes of a fourth- or fifth-century Thessalonian Christian, as well as in relation to their architectural position and to those parts which have since been lost. The ambulatory, now destroyed, encircled the outside of the building and opened into each of the barrel-vaulted bays. As worshippers entered the church, they passed from the ambulatory into the great round nave through the bays. Here their eyes would immediately have been drawn upwards to admire the luxuriant, geometric tracery and the richly ornamental representations of birds and fruit, reminders of God’s bounty and wonders on earth and many, if not all of them, possessing some religious symbolism. The bays, therefore, had an extremely important function. They were passages in which Christians living in the terrestrial world were prepared for the sight of the great vault of heaven represented by the dome. In Rome the ambulatory mosaics of Sta Costanza (circa 340) may have served a similar purpose and, in any case, a comparison of these two examples of fourth-century ecclesiastical art is of particular interest. The mosaics of Sta Costanza are pagan in spirit as well as in form. They are related, not to the humble Christian art of the catacombs, but to the decorative motifs that had been used upon the walls and floors of the imperial Roman palaces. The ceilings of the bays in St George are also imperial art, and in both form and subject they demonstrate a clear relationship to those of Sta Costanza.

1. O. Tafrali, Topographie de Thessalonique (Paris, 1913), p. 158 (trans.).

2. C. Texier and R. P. Pullan, Byzantine Architecture (London, 1864), p. 137.

3. W. M. Leake, Travels in Northern Greece (London, 1835), vol. iii, p. 240.

111

![]()

In spirit, however, they belong to an entirely different world, where paganism has been replaced by Christianity and the cool, clear marbles of Rome by the rich colour and ornate splendour of the East.

Reaching the central domed space, or nave, their eyes already uplifted by the ceilings of the bays, the Christian worshippers in St George saw first the martyr saints, whose martyrdom for their faith was, in several cases, so recent as to be only just beyond the memories of living men. Depicted in the act of intercession for the congregation below, these stood in front of the iridescent portals of heaven. Above them, in ‘vertical perspective’, were (we presume) the apostles, the chosen disciples among men of the Son of God. Finally, reigning above all Heaven and Earth, was the crowning glory of Christ Himself.

This was not the whole. We can neither, for instance, reconstruct in our minds the decoration of the apse nor sense the impact of the church’s architectural environment. Nor can we recreate the triumphant fervour of fourth-century Christianity. Even so, in the Rotunda that has been pagan temple, church, mosque, and which is now a museum, it is still not difficult to feel some lingering remnant of the awe that must then have overtaken Christian Thessalonians when they entered it to worship.

Before considering the significance of the architectural compositions in the dome we shall take the individual figures of the martyr saints represented in the foregrounds. In so doing, it is essential always to have in mind the splendour and exuberance of the whole scene ; the golden background, against which golden pillars, arches, friezes and cupolas gleam and sparkle with the fight of many coloured jewels ; rich curtains and the bright plumage of birds adding further exotic touches. It is Oriental rather than Occidental splendour, and, yet, with all the magnificence, there is a restraint which indicates an Orient that has felt the influence of Hellenism.

The Martyr Saints in the Dome of St George

The figures all stand in a frontal and ‘orante’, or praying, position. None have haloes. Beside them are written their names, their professions, usually soldier or priest, but with exceptions, such as Damian, who is described as a doctor, and Philemon, as a flute player, and the months of their festivals. Following the panels clockwise from the lost panel over the opening to the apse, the saints are :

1. An unknown saint who occupied a part of the mosaic that is now completely destroyed.

Leo, wearing a chlamys, was a leading citizen of Patara in Lycia. He was martyred in the reign of Diocletian for preaching Christianity and persistently refused to sacrifice to idols even under long and extreme torture.

Philemon, wearing a phelonion, was a flute player of Comana who, when ordered to play his instrument before idols, publicly declared himself a Christian and prayed that his flute might be destroyed lest it be used for idolatrous purposes. Legend tells us that his prayer was answered. Flames descended from the sky and consumed his flute, and afterwards he died a martyr.

2. Onesiphoros, in a chlamys, and Porphyrios, in a phelonion, were martyred together. The former was a powerfully connected citizen of Iconium (Konia) where he received St Paul, and was baptised by him with all his household. He left Iconium to preach Christianity at Paros, where, with his servant Porphyrios, he was seized and tortured to death.

3. Damian and his friend Cosmas (whose inscription is now lost) both wearing the phelonion, were two natives of Arabia, usually jointly described as the ‘ Anargyriou’, or silverless ones. They travelled about the country curing the sick without charge, only asking that those they healed should embrace Christianity. Enemies denounced them as magicians to the Emperor Carinus. Arrested, they were ordered to renounce Christianity. The two refused, but managed to convince the emperor of their righteousness by curing him of an illness, whereupon the emperor, too, believed. Their pagan opponents, jealous of the honours they received, attacked and killed the two one day while they were gathering herbs on a mountainside.

4. An unknown saint wearing a chlamys, the inscription beside him has been entirely lost.

Romanos (only his forearm and inscription now remaining), a deacon at Caesarea in Palestine, was a native of Antioch, where, during a visit in the reign of Diocletian, he comforted a group of Christians who had been sentenced to torture, and rebuked their judge. For this he was thrown into prison and strangled.

112

![]()

Eucarpios, in a chlamys and described as a soldier, was martyred at Nicomedia, also in the reign of Diocletian.

5. The inscription regarding the first saint, who wears a phelonion, in this panel has been lost. The second, Ananias, also in a phelonion, was a Christian priest, who, during the Diocletian persecution, displayed such fortitude under torture that his warder begged to be baptised. Both were then bound to a wheel and placed upon a burning grate. The fire at once extinguished itself, and the seven soldiers responsible for the torture were inspired to accept Christianity. All nine were ultimately put to death.

6. Basiliscos, wearing a chlamys, was a native of the kingdom of Pontus and a soldier in the Tryonian legion. With two fellow Christians he was arrested during the Diocletian persecution and executed after a period of torture for refusing to sacrifice to Apollo.

Priscos, another soldier, also in a chlamys, was a Roman officer in the guard of the Emperor Aurelian. While serving in Gaul he was arrested, with many of his companions, for refusing to worship idols, and was martyred.

7. Philip, dressed in a phelonion, was bishop of Heraclea in Thrace at the beginning of the fourth century. When his church was ordered to be closed and its treasure seized, he persisted in holding services in its portico and in rallying Christians to their Faith. For this he was burnt at the stake.

The history of Thermos is obscure. He is classified as a soldier and wears a chlamys. Only parts remain of the third saint in this panel and the inscription is also mostly obliterated. Earlier photographs, however, indicate him to be Cyril. He wears a phelonion and may have been a Palestinian deacon martyred in the persecutions of the early fourth century.

The bodies and draperies of the saints are well executed, but the heads are outstanding work by one or more highly talented artists. Accomplished in much smaller tesserae than the costumes and the architecture, the faces are modelled with extreme delicacy and without the use of dark, heavy contours to delineate the features. Considerable variety is displayed. Some, Onesiphoros and Porphyrios, in particular, have close similarities with such works as the statue of the Good Shepherd from Palmyra (now in Berlin). Others, such as Ananias and his anonymous companion, have links with the school that produced the fifth-century sculptured head (Pl. 22f) found at Ephesus. More than one have resemblances with the work of the Fayum painters. For all their individuality, however, all possess a transcendental and hieratic quality. They are saints who, by virtue of their supreme sacrifice, have achieved the Heavenly and ineffable Peace of God. They are, in fact, prototypes of the long series of saints and fathers of the Church that have represented the idealism of Byzantine Christianity on the walls of churches from the fourth century until the present day. The iconographic break with the past which these figures represent is shown by a comparison with the fourthand fifth-century mosaics of the Roman churches of Sta Costanza and of Sta Maria Maggiore. In fact, Sta Maria Maggiore’s cycles of crowded Biblical scenes are not unlike in technique and are similar in educational purpose to the scenes on Thessalonica’s Arch of Galerius.

The Architectural Compositions in the Dome of St George

Two-storied, architectural compositions rise behind the martyr saints in each of the seven remaining panels of the lowest zone of the dome. Together with the lost panel, they give an effect of an octagon. There are four different architectural versions, the northern being repeated by the southern, and the western, presumably, by the now lost eastern panel. The repetition of the north-eastern, however, does not appear in the diagonally opposite position, but in the south-east, and, correspondingly, the north-west in the southwest. Each panel is separated from the next by a foliage and vase arrangement symbolising the tree of life in a highly stylised manner. While not identical, each of these follows a closely similar pattern.

Before discussing the variations in these architectural compositions it will be useful to take the features that are common to all. Most prominent, perhaps, is the glowing, golden nature of both the architecture and the background. This golden effect is intensified by the brilliant colours of the martyrs’ clothes, of rich curtains, and of the splendid plumage of peacocks and other birds, as well as by the fact that the architectural compositions are shallow façades, consisting for the most part of pillars and arcades,

113

![]()

through which the golden background is constantly revealed.

Yet, shallow as these architecturescapes are, they are far from appearing insubstantial. Well-proportioned marble pillars support massive entablatures. They are façades only in the sense that a city or palace gate is a façade — for the city or palace that is within.

In each case the central architectural feature is an apse, exedra or opening, flanked by one or two pavilions on either side. An upper storey consisting of a central superstructure and two subsidiary loggias produces the impression of an ornate, and even fantastic, towered façade. An often inaccurate use of perspective achieves a limited sense of depth, not unlike that of a relief carving. The rendering of architectural components also frequently appears careless. Symmetrical arrangement and an effect of exuberant splendour, rather than realism and exactitude, are the artist’s aim.

In three of the pairs of panels a round, rectangular or hexagonal ciborium stands in the centre foreground. The exception occurs in the panel opposite the apse ; here a low chancel screen takes its place.

Panels 1 and 7 (Pl. 17)

An unknown saint (now wholly lost), Leo and Philemon stand in the foreground of Panel 1 ; Philip, Therinos and Cyril in the foreground of Panel 7.

These two panels, the most classical of all, flank the missing composition above the apse. The central structure of the lower storey is an apparently unroofed exedra. In front of it, or projecting from it, is a rectangular ciborium with a triangular pediment above the entablature, which is common to the ciborium, the exedra and a pavilion on either side. A round, j ewelled candlebra hangs from the centre of the ciborium and in the tympanum two winged angels hold a round shield or clipeus bearing the head and shoulders of Christ. Between the ciborium and the adjoining pavilions the exedra reveals an arcade with turquoisecoloured curtains drawn back around the inner pillars to display lamps hanging behind. These two pavilions, which are surmounted by bow-shaped pediments, are each flanked by another pavilion, the entablature of which is slightly different, and which has a semicircular pediment and a scalloped tympanum.

The foreground pillars of the ciborium and the outer pavilions carry jewelled bands. The remainder are plain. The capitals are all Corinthian, but with a tendency towards a Composite effect.

Above the ciborium in the centre of the upper storey is a circular, domed loggia supported by four pillars. Behind it stand three loggias, the centre having a flat top and the two outer triangular pediments with scalloped tympana. A common entablature serves all three. Reddish-pink curtains, knotted in the middle, hang at the back of the outer loggias, but they are arranged with an eye to symmetrical presentation rather than to realism. All the columns in the upper storey are plain and have Ionic capitals.

Unlike the remaining panels, no birds figure in either of these two compositions.

Panels 2 and 6 (Pl. 16)

Onesiphoros and Porphyrios stand in the foreground of Panel 2 and Basiliscos and Priscos of Panel 6.

A wide, semicircular, semi-domed apse, ceiled with a sumptuous peacock-tail design occupies the centre of the lower storey. Mounted upon a pedestal in front of this is a hexagonal ciborium, with six spiral pillars supporting a deep entablature from which a hexagonal roof rises to a point. The entablature, plain in form, is decorated with three bands, the upper and lower having a lattice-work pattern, the centre a series of ‘ rayed suns ’. A low lattice-work chancel screen connects the pillars, but leaves the front open. A tall, bejewelled cross, upon the top of which a dove (?) descends within a rayed mandorla or clipeus, occupies the centre foreground.

Single arcaded pavilions flank the apse on either side. These, like the apse itself, have fluted pillars and capitals that verge upon the Composite. The arches of the pavilions and the arcades of the apse, two of which appear on each side of the ciborium, are all heavily jewelled. A frieze of stylised, opposed swans, with vases as centre-pieces, is the chief feature of the entablature, which is common to both the pavilions and the apse. Tall candlesticks, with lighted candles, stand in the centre of the pavilions.

Of the three loggias comprising the upper storey, the two outer stand above the pavilions on either side of the apse. In both cases four columns, on a deep base

114

![]()

or parapet, carry an ornate dome that curves upwards at its outer edges in defiance of all the laws of perspective. A lamp hangs from the centre of each. The central structure is set back, as though extending behind the apse. It is difficult to say whether it is an octagon or a hexagon, and its form is further complicated by two projecting pillars on either side. A triangular pediment rises above the cornice between the two foreground pillars. Two vases and two doves also appear upon the cornice and two phoenixes are placed just above the parapet between the outer loggias and the. central structure.

Contrasting with those of the outer loggias, the pillars of the central structure are plain. On the other hand, the capitals of the latter are similar to the capitals of the lower storey, while those of the outer loggias follow a more simple design.

Panels 3 and 3 (Pl. 15)

Damian and Cosmas appear in Panel 3 and Ananias and an unknown saint in Panel 5.

In this panel it is the upper storey which has an apsidal character, while the lower has as its centre-piece what appears to be an open rectangular loggia. In front of this loggia a circular ciborium stands upon a rectangular base. The ciborium has six pillars, the two in front ornamented with jewels and bands of pearls and arranged, not equidistantly, but three on each side. They support a high entablature displaying a Greek fret frieze. Above this is a ribbed cupola. Three steps lead up to a table or a backless throne, bearing an open, sacred book, beneath the ciborium. A curtain running between the two rear pillars backs the lower part of the ciborium, and a lamp or a wreath hangs from its ceiling.

The rectangular loggia behind is carried on four pillars, the two in the foreground being spiral and the two in the rear plain. The cornice is surmounted by a low triangular pediment. Two tall candlesticks with lighted candles stand one on each side of the ciborium in front of this loggia.

Flanking the central structure are two narrow pavilions, their foreground pillars decorated with bands of pearls and supporting, above their entablatures, low curved pediments with scalloped tympana. These, in turn, are enclosed by pairs of projecting

pillars, ornamented with jewelled bands. A common entablature serves the central structure and its two flanking pavilions ; another above the projecting pillars has a slightly different design.

The central structure of the upper storey consists of a semicircular apse flanked by porticoes. In the apse five arcades support a ceiling in the form of a scallop shell. An ornate lamp hangs from the ceiling in the centre, and turquoise curtains, knotted back, half-close the porticoes. The pillars are uniformly plain.

Outside the porticoes, and standing upon the lower pavilions and the enclosing pillars, are rectangular loggias. Crosses, Latin in their shape, but ansated in Oriental fashion, that is to say, with the ‘handle’ of the ‘P’ open at the bottom, and with pendants hanging from their arms, stand on each of the flat foreground cornices. Dark plumaged birds are placed on either side of the crosses. Exquisitely coloured peacocks stand beneath the crosses between the four fluted columns of each of the two loggias.

In the panels the capitals are Corinthian throughout except in the ciborium, where a slightly more simple form is preferred, and in the apse arcades of the upper stories. Here, in Panel 3, a simple, rather crude form appears ; in Panel 5 , two are simplified Corinthian and two are Ionic.

Panel 4 (Pl. 14)

(Panel 8, above the apse, has been entirely lost)

An unknown saint and Eucarpios stand in the foreground. Only the inscription and a forearm have survived of the figure of Romanos, originally in the centre.

The centre section of the lower storey is planned on lines similar to those of the upper storey in Panels 3 and 5. A central, arcaded apse, with a low curved pediment and a scalloped ceiling, is again flanked by porticoes. Here, however, the proportions are taller, the porticoes narrower, and the whole effect is more substantial as well as more ornate. The foreground pillars of both apse and porticoes carry bands of pearls. Dark plumaged phoenixes stand on the cornices of the porticoes.

Within the apse and extending forward from it is a low chancel screen. Unfortunately, only a small part of this remains, but it appears to have been hexagonal in form with an entrance in front. Romanos,

115

![]()

like his companion saints, was placed outside this chancel and on a lower level.

The pavilions that, one on either side, Hank the porticoes appear to be visualised on a quarter circle ground plan. The front and inside faces are straight, but behind this can be seen an unmistakably curved line belonging to the lower edge of the entablature. Moreover, in addition to the two foreground pillars, which support a triangular pediment, three more are visible behind. White, silken curtains, strikingly decorated with vivid, round patches of colour, half close the rear openings and fountains play inside. Spiral bands ornament all the ten pillars of the porticoes.

Much of the upper storey is missing. In the central part a long, flattened arch, from which hang a row of pendants, runs above and behind the vestiges of a triangular pediment, which surmounts an almost entirely lost architectural structure above the apse. An ornate vase stands at each end of the arch. On either side, above the lower pavilions, spiral columns carry a nearly semicircular arch, from which spring pieces of cypress-like foliage. Behind each arch is a glimpse of a flat-topped loggia. The entablature, uniform in all sections of this storey, carries a frieze of opposed swans. This is smaller than, but is otherwise identical with, those in Panels 2 and 6.

Corinthian-type capitals are the rule throughout this panel with the exception of the central composition of the upper storey. The one surviving capital of this is clearly Ionic.

Two distinct aspects of these architectural compositions emerge from the foregoing analysis. Firstly, the structures do not enclose a space as is normally the architectural function of a temple or a house ; they represent instead a magnificent façade, the three-dimensional presentation of which only the more emphasises the fact that it is intended as a façade. Secondly, the ciboria, the chancels and the various sacred symbols indicate a cult-purpose analogous to the sanctuary of a church.

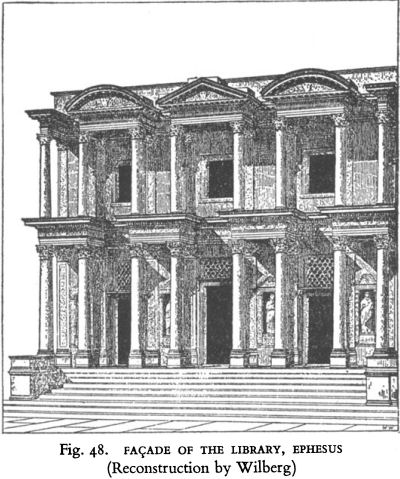

Fig. 48. FAÇADE OF THE LIBRARY, EPHESUS (Reconstruction by Wilberg)

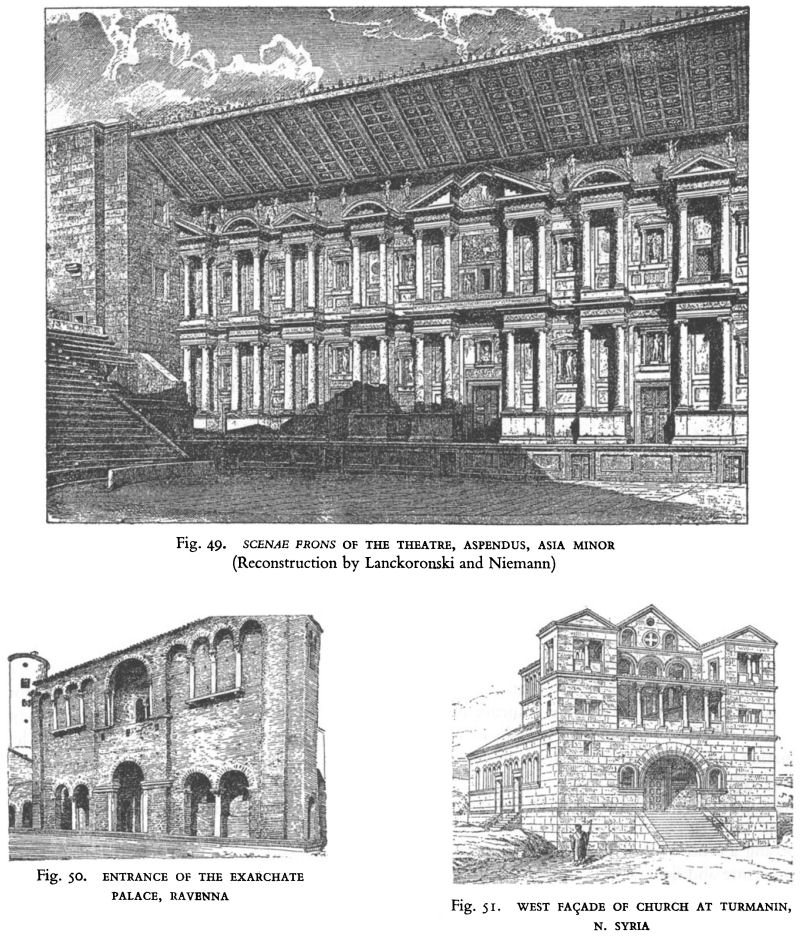

The architectural form shown in these panels had long been a familiar one to the Roman world. Some of the later rock tombs of Petra executed under strong Hellenistic influence, El Deir and El Khasne in particular ( circa late first or early decades of the second century a.d.), bear such detailed resemblances that it is almost tempting to think that the artist of St George had been inspired by them (Pl. 18). The same form was used in the frontages of such civic buildings as the Library at Ephesus (early second century a.d.) and the Agora at Miletus (first century a.d.). The Propylaeum at Gerasa also follows what are essentially similar lines. In first-century Italy it appears in Pompeiian fresco decoration, notably the Porta Regis mural of the Casa di Apollo, and in Rome in the Thermae of Titus and the Casa di Livia on the Palatine. Another example is to be found in the Paris and Oenone stucco relief in the Palazzo Spada, Rome, although, in this case, the version is more simple and practical and a complete house is indicated. The most widespread use of this architectural form, however, appeared in the scenaefrons of the late Hellenistic and Roman theatres. The theatre of Aspendus in Pamphylia in southern Asia Minor may be cited as an obvious example, but countless others can be recalled from the Mediterranean provinces of the Roman Empire.

The atrium of Basilica A at Philippi and the entrance to the Exarchate Palace at Ravenna show that the form survived into the fifth and early sixth centuries.

116

![]()

Fig. 49. SCENAE FRONS OF THE THEATRE, ASPENDUS, ASIA MINOR (Reconstruction by Lanckoronski and Niemann)

Fig. 50. ENTRANCE OF THE EXARCHATE PALACE, RAVENNA

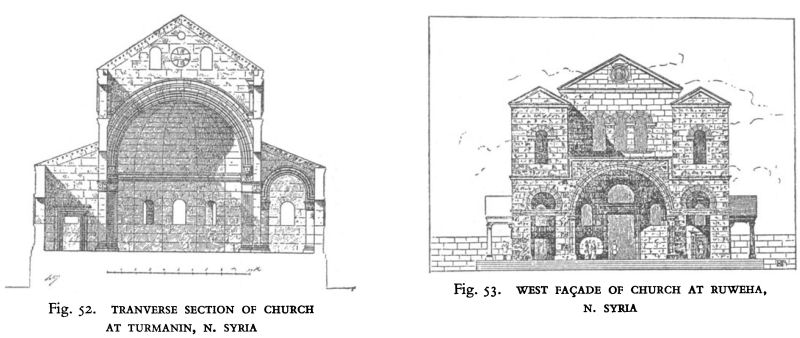

Fig. 51. WEST FAÇADE OF CHURCH AT TURMANIN, N. SYRIA

In a degenerated version it appears in the mosaic of Theodoric’s palace in S. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. In Syria, the ‘Hilani’ towered west fronts of the churches of Turmanin and Ruweha again repeat the essential features.

Palestinian Syria contains an example of particular interest, the mosaic representations of the early Church Councils in the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The mosaics surviving into our own century were executed in 1169 on the initiative of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel Comnenos when Palestine lay under Arab dominion.

117

![]()

Fig. 52. TRANVERSE SECTION OF CHURCH AT TURMANIN, N. SYRIA

Fig. 53. WEST FAÇADE OF CHURCH AT RUWEHA, N. SYRIA

It seems, however, that these replaced earlier mosaics which had probably been heavily damaged or defaced. In such circumstances the twelfth-century mosaicist may have only restored earlier mosaics, modernising here and there and, of course, inserting details of the Councils in place of representations of human or other living creatures in deference to the Islamic tenets of the occupiers (Pl. 18).

So little remains of Parthian and Sassanian architecture that generalisations have to be based upon a relatively small amount of evidence. Nevertheless, the popularity of this form of architectural façade cannot be questioned. It was a feature of the palaces of Hatra and Ctesiphon and was extensively adopted by the Arab conquerors. In all Persian examples, however, and even in many Syrian, the influence of the architecture of the ivan and the city gate shows in the dominating central — in later examples often sole — doorway (Pl. 18, Figs. 51, 53).

These comparisons apply to the St George compositions in their aspect of a two-storied façade comprising a central opening or exedra supporting a superstructure and flanked by porticoes and towered pavilions. In their other aspect, that of a structure serving a cult purpose, we find ourselves observing what is essentially, however extravagantly contrived, the principle of a wide central apse, flanked by a subsidiary chamber on either side. In fact, we have a fanciful but clear picture of that tripartite form of sanctuary characteristic of Syrian and Mesopotamian churches. In three versions a ciborium stands in the centre of the apse, in the fourth a chancel, ‘a fence of . . . lattice work’ to quote Eusebius’s description of the cathedral of Tyre, occupies this — the Oriental — position of the altar.

As far as we know, which is really very little, the full structure of the Oriental tripartite sanctuary was not introduced into Thessalonian church architecture for another century, when it appeared in the tiny Chapel of Hosios David. The Basilica of St Demetrius (412-13) effected a compromise between Rome and Syria, but a few years later ‘Acheiropoietos’ (circa 440) reverted severely and conservatively to the Occidental plan.

These facts and considerations of style imply that the St George mosaics were probably the work of an artist from the capital, not from Macedonia. In this case they not only are a revelation of the splendour and brilliance of Theodosian monumental art, they indicate the ascendancy which Syrian liturgical ideas had already achieved in Constantinople in less than threequarters of a century. Perhaps, too, they may convey to us something of the splendour of the sanctuaries of the great late fourth-century basilicas, as, for instance, Epidauros and Nicopolis B, not to mention the lost churches of Constantinople itself.

There was no conflict in this union of the towered façade and the cult purpose. The concept of the whole decoration of the dome was the creation of, in Lethaby’s words, ‘a localised representation of the temple of the heavens not made by hands’. The golden façades rising behind the martyr saints were the forecourts of Heaven, behind which the apostles walked in glory and, ultimately, Christ Himself, attended by the archangels, sat enthroned.

118

![]()

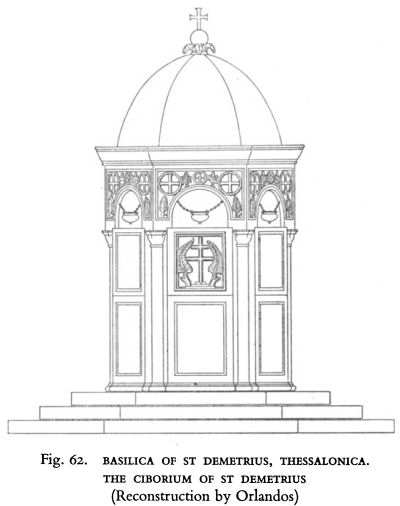

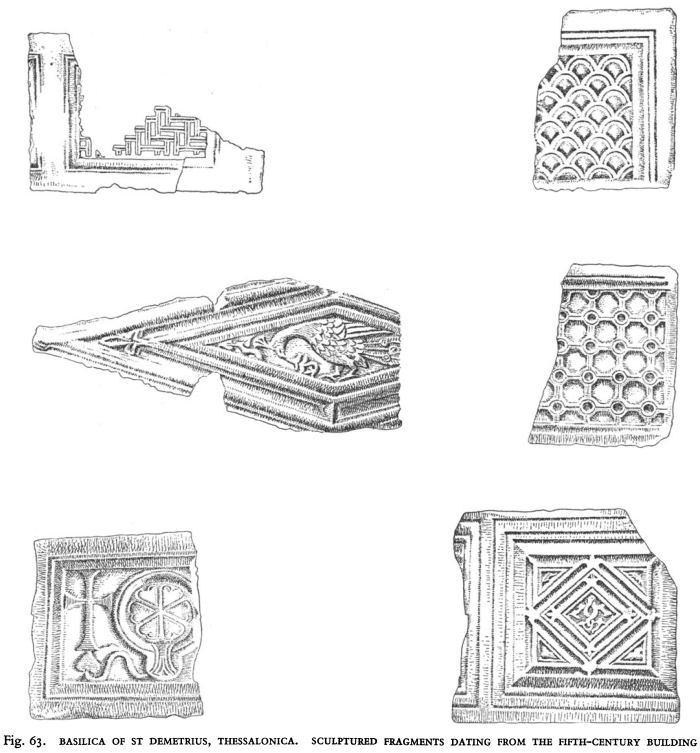

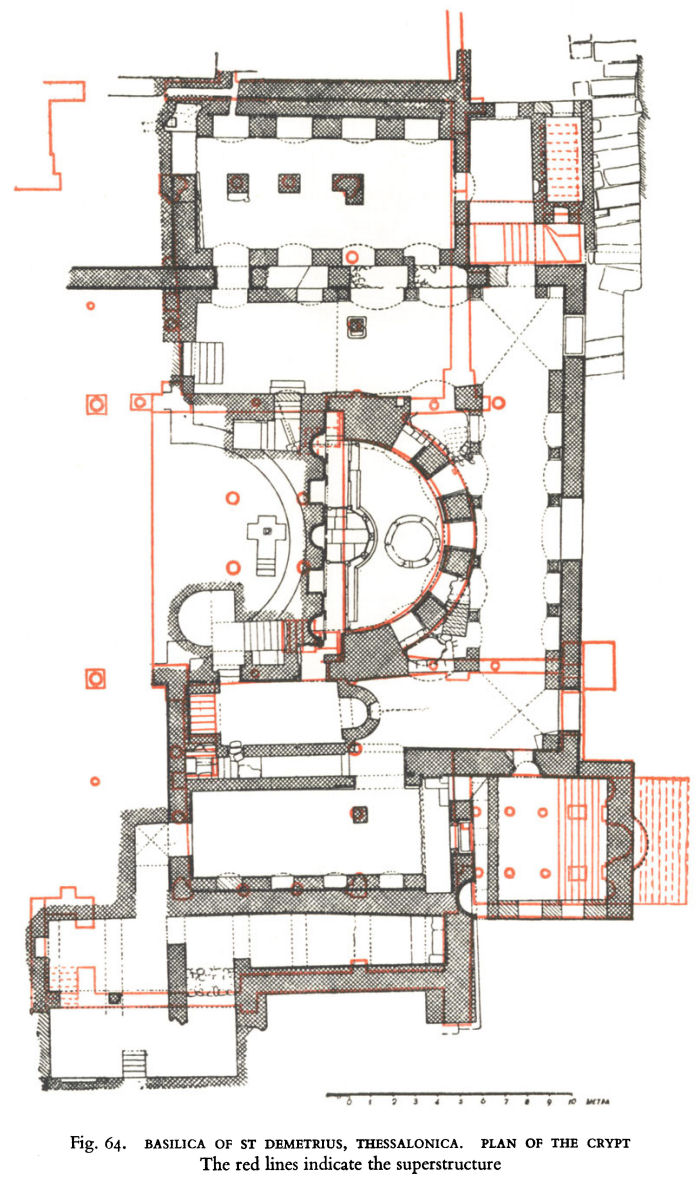

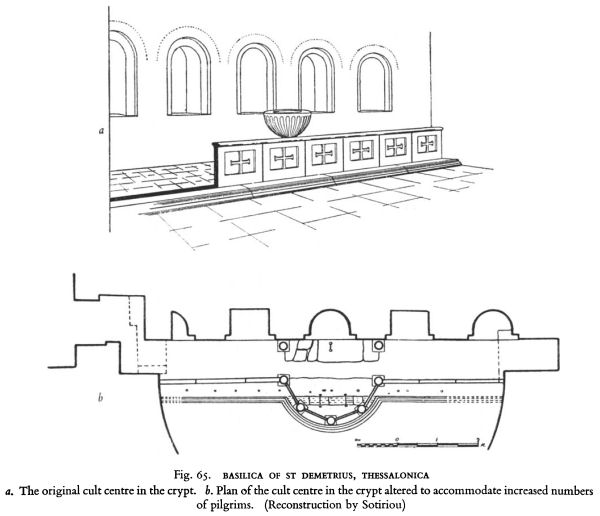

This was not simply the signification of a great and monumental work of art ; it expressed in visual terms the Church’s fundamental liturgical concept. The martyr saints, who had proved themselves by dying for Christ as Christ had died for men, appeared as the officiating priests in the Divine — here the Heavenly — Liturgy. Thus, the complete composition represented in early Byzantine terms the supreme experience of Christian worship. Such a concept was not necessarily common to the whole contemporary Christian world. Like the tripartite sanctuaries and the use of the dome to signify the sky temple, or Heaven, it was Oriental, that is to say, Syrian or Mesopotamian rather than Roman. The artist portrayed a religious experience, a ‘communion’ that was purely spiritual and which had rejected all hint of physical participation by the congregation. Contemplating it one recalls those essential points of difference between the Roman and Oriental liturgies discussed in Chapter II.