PART II. MACEDONIA BETWEEN ROME AND CONSTANTINOPLE

IV. Roman Macedonia and the Mission of St Paul 49

V. The Centuries of Persecution and the First Gothic Invasions 66

VI. Political and Ecclesiastical Rivalries 73

VII. Renewed Gothic Invasions and the Appearance of the Slavs 77

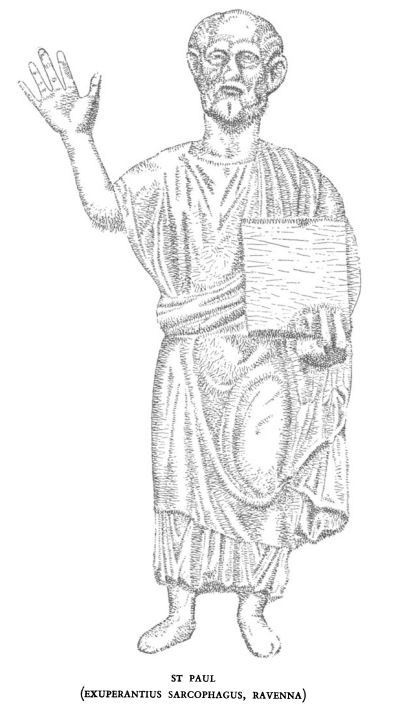

ST PAUL

(EXUPERANTIUS SARCOPHAGUS, RAVENNA)

Chapter IV. Roman Macedonia and the Mission of St Paul

The Parthian revival of the Persian Empire occurred in the third century b.c. In the course of the next century Rome began its expansion into the lands bordering the eastern Mediterranean. Attempts by the Macedonian kingdom to resist Roman domination were finally liquidated following Roman victories in 168 and 148 b.c. The Romans neither regarded, nor treated, their Macedonian rival lightly and set out systematically to eradicate every trace of its power and independence. Perseus, the last Macedonian king, was seized in 168 while claiming political sanctuary on Samothrace and, after the failure of the final bid to regain independence in 148, the whole of the surviving aristocracy and the chief military and civil officials were deported to Italy. The most important industries were forbidden; the country was divided into four parts, and Macedonians forbidden to cross from one to another. Thus trade, as well as political control, fell largely into Roman hands. Quickly and brutally, the proud motherland of the empire which had reached to India was converted into a stagnant backwater of the Roman Empire.

Yet, rich in agriculture and forests, and straddling the strategic land-routes connecting the Adriatic and the central Danube plain with the Aegean, Macedonia could not be left indefinitely to decay. With all Illyricum falling under Roman domination in 27 b.c., and with the subjection by a.d. 46 of the fierce Thracian tribes in the eastern Balkans, it ceased to be a frontier province, and, in the security of the pax romana, began to recover from the severity of its conquest. Except for occasional, small-scale Thracian invasions or uprisings, and episodes in the civil wars of the first century b.c., little occurred to disturb its peace until the Gothic irruption midway through the third century a.d. The recovery of the ancient Macedonian capitals of Aegae and Pella was perhaps slow, but Thessalonica, the seat of the provincial governor, steadily developed into a city of considerable commercial importance and, in common with other leading provincial centres of the Roman Empire, received valuable civic privileges, including the right of minting its money. It played a minor, but, on the whole, profitable part in the civil wars of the first century b.c. Pompey, fleeing from Rome, chose it as his residence and headquarters until transferring to nearby Verria. The Thessalonians, however, managed to avoid retribution through having firmly maintained a policy of neutrality. A few years later, through luck or judgement, the city materially improved its standing in the Roman world by coming out in open support of Antony and Octavius prior to their victory at Philippi in 42 b.c.

For Philippi, lying at the easternmost limits of Macedonia on a narrow neck of firm land between the hills and the marshes which then extended over the greater part of the Philippi plain, the battle between the rival Roman armies was of great consequence. The victors were quick to realise its strategic situation, vital alike for the protection of eastern Macedonia against still unconquered Thrace, for the maintenance of communications with the Roman provinces of Asia Minor through the port of Neapolis (Kavalla), and as a base for any future expansion of the Roman Empire towards Macedonia between Rome and Constantinople the east.

48

![]()

Reliable veterans from the victorious Roman army were given their discharge and awarded land on which to settle. Twelve years later Octavius brought over a still larger group of colonists from Italy. These newcomers quickly became, on both a large and small scale, the principal landowners in the region. With the administrative officials, they tended to remain a distinct group, not mixing with the Greek element, by whom the commercial life of the community continued to be maintained. The indigenous Thracians also continued as an important element of the population in the city of Philippi and, probably to a greater degree, in the countryside. Previously open to the influences of Hellenism, they were now no less susceptible to those of Rome; but, as archaeological evidence clearly shows, the traffic in ideas by no means flowed one way only. [1]

The heavy Romanisation of Philippi was probably exceptional among the predominantly Greek areas of coastal Macedonia, although at the same time Octavius settled other groups of Italian colonists at Pella, Dion (Dium), Cassandreia and at Dyrrhachium (Durazzo) on the Adriatic coast, to which the Roman administrative province of Macedonia temporarily extended. In general, however, the urban centres of the south appear to have continued to retain their Greek character, and to have received only small numbers of Italian settlers and officials.

Farther inland, among the mountainous ranges of the north and west, a different situation developed. In these wilder regions, even in the towns, Hellénisation had never been complete. Greek influence, while paramount and a strong civilising force, had had to contend with constantly shifting tribal populations and with cultural allegiances from beyond the Macedonian frontiers. These were principally Illyrian on the west and north and Thracian on the east. The lack of Illyrian or Thracian literature makes any estimate of their cultural contributions extremely difficult, but it was certainly far from negative. Scymnus of Chios, writing about a century before the beginning of the Christian era, calls the Illyrians ‘ a religious people, just and kind to strangers, loving to be liberal, and desiring to live orderly and soberly’. Other contemporary Greek or Roman historians are less complimentary, or more biased. One point upon which there is no doubt is that women were accorded an exceptionally favourable status in Illyrian society ; a queen, Teuta, was one of the principal leaders of Illyrian resistance against the Romans. While the historians unfortunately leave us in ignorance of the nature of the religion of the Illyrians, other evidence, including traditional tattoo markings in the more primitive parts of Albania, suggests a strong cult of sun and moon worship. [2] Certainly later, during the first two or three centuries of the Christian era, Mithraism exerted an exceptionally powerful appeal in Illyrian areas.

The Thracians are classed together with the Illyrians by the Greek and Roman historians as peoples who tattooed their bodies and offered human sacrifices, who loved singing, playing the flute, dancing and fighting. In their social customs, however, the Thracians appear considerably more akin to the Scythians. Their religion, as we shall see when considering the impact of Christianity, included a strong concern with a future life. Unlike the Illyrian religion, it exerted a profound and direct effect upon the Roman conquerors, and Romanised forms of one of its principal aspects, the Heroic Hunter or Thracian Horseman, appear on funeral steles throughout central and eastern Macedonia and even as far north as Viminacium (Kostolac) on the Danube near Belgrade.

After the Roman conquest of Macedonia the flow of independent Illyrian and Thracian influences into the province must have sharply declined. Moreover, forceful and ruthless Roman administrators, Roman garrisons, the privileged activities of Roman merchants, all possessing the prestige of a conquering race and backed by the Roman genius for civil administration, aided Roman influences to supplant those of Hellenism in the non-Greek parts of Macedonia. Two other factors played an important part in this process. The first was the Roman policy of awarding grants of land in strategic areas to veteran soldiers. The second was the system of Roman roads, which was rapidly developed as soon as the conquest of the Balkans and Asia Minor was complete.

1. P. Collart, Philippes, ville de Macédoine depuis ses origines jusqu à la fin de Vépoque romaine (Paris, 1937).

2. M. E. Durham, Some Tribal Origins, Lam and Customs of the Balkans (London, 1928), p. 101 et seq.

50

![]()

Two main strategic highways crossed the Balkan peninsula from west to east. The northern, Unking the Balkans with the Roman cities of northern Italy and southern Germany, left the Pannonian Plain at Sirmium (Mitrovica) and Singidunum (Belgrade), followed the Danube to a point near Viminacium (Kostolac, Drmno), and the Morava until Naissus (Niš). It then passed through Sardica (Sofia), crossed the Succi Pass to Philippopolis (Plovdiv), Hadrianopolis (Edime), Arcadiopolis (Lule Burgas), to Byzantium, slightly more than a month’s journey from Singidunum. The southern road was the Via Egnatia. From the Adriatic ports ofDyrrhachium (Durazzo) and Apollonia two roads converged at Clodiana and then passed through Scampae (Elbasan), Lychnidus (Ohrid), Heraclea Lyncestis (near Bitola), Aegae (Edessa), Pella, Thessalonica, then, via Amphipolis, Philippi, Neapolis (Kavalla), Akontisma and Thracian Heraclea to Byzantium. A network of subsidiary roads connected the two highways and other outlying centres. North to south, the Singidunum route was joined at Naissus by a highway from Ratiara (Vidin) on the Danube which passed through Ulpiana (Lipljan, some ten miles south of Priština). Here it diverged, one branch going west along the present Peć-Andrijevica road to Scodra (Shkoder, Scutari) and reaching the sea at Dulcigno (Ulcinj); the other, and the more important, continuing to Scupi (Skopje), Stobi and Thessalonica. From Stobi roads also ran south-west to Heraclea and north-east to Pautalia (Kustendil) and Sardica. These were by no means the only routes of importance; others connected them with the cities based on the Black and north Adriatic Seas. Apart from their importance in linking Italy and Asia Minor, they were the main arteries of commerce and defence for the Balkan region and, consequently, for the diffusion and protection of its Roman civilisation.

The northern of the two great west-east highways was a pioneer Roman conception, for it lay off the paths of the early Mediterranean and Oriental civilisations. Parts of the Via Egnatia, on the other hand, retraced routes which had existed for centuries before the Roman conquest. They had been made use of by Xerxes in his attack on Greece and Alexander in his conquering expeditions to the east. Nevertheless, under the Roman occupation, the Via Egnatia attained a new efficiency and significance. The stretch linking

Dyrrhachium and Neapolis was newly laid and completed by the end of the third quarter of the second century b.c. Its extension to Byzantium had to wait for the conquest of Thrace in a.d. 46, but a terminus at Neapolis sufficed for the control of Macedonia and for access to Asia Minor by a conveniently short sea-passage.

The intensification of the struggle with Parthia following the accession of Trajan in a.d. 98 further increased the importance of the Via Egnatia, an importance which was maintained until the first half of the fourth century. Milestones, erected to commemorate substantial repairs, bear the names of the Emperors Trajan, Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Constantinus Chlorus and Galerius. Inns, or ‘Tabemae’, were from the beginning built at appropriate staging-points, and there occurred at least one instance where one of these, the ‘Tres Tabemas’ or ‘In Tabemas’, gave its name to the locality. An epitaph discovered near the site of ‘Ad Duodecimum’, a staging-centre twelve Roman miles west of Philippi, commemorates C. Lavus Faustus ‘institor tabernas’ — one likes to think of him as a discharged veteran of the eastern wars or, maybe, of misty Britain who had retired with his gratuity to keep his inn — and records for posterity that [sic] he gave good measure. Nero, in a.d. 61 ordered ‘tabemae’ to be erected along the newly built military roads of Thrace.

The Via Egnatia was a highway along which men, ideas, merchandise and loot travelled towards Rome from Asia, as well as expeditionary armies on their way from Italy to the eastern wars. In this it differed from die subsidiary roads leading into the interior. The countryside around Stobi, Scupi, Ulpiana and Naissus had lain too far north for the penetration of Hellenic influences ever to have been thorough. Nor did it carry a Greek population that was, except in the case of Stobi itself and, to lesser extents, Scupi and Ulpiana, much more than a trading-post. Now they were by-passed by the East-West traffic handled by the cities on the Via Egnatia. The retired Italian veterans and colonists tended to take a fuller share in the life of the community in these quieter, northern cities. Greek and Jewish inhabitants existed, who continued to use Greek as their language, but such centres grew up, or

51

![]()

were rebuilt, as essentially Roman cities, with the majority of their populations speaking Latin rather than Greek and worshipping a medley of Roman and indigenous gods.

Probably towards the end of the year a.d. 49, a small band of zealots, headed by St Paul, a Jew with Roman citizenship from Tarsus in Cilicia, took ship from Troas in Asia Minor, stopped for a night on Samothrace, and landed the next day at the port of Neapolis, the Kavalla of to-day. From here they immediately took the Via Egnatia, following it over the Symbolon Pass, and came to Philippi, ‘the chief city of that part of Macedonia’. [1] They carried the new gospel of Christianity.

Reasons of convenience probably dictated that St Paul, making for Macedonia, should travel by sea, via the great pagan island sanctuary of Samothrace, to Neapolis, and thence to Philippi. Thrace had been conquered only three years earlier and eastern Macedonia was still the terminus of the Via Egnatia and the easternmost point of Roman civilisation in Europe. Yet, in his choice of Macedonia, and particularly of Philippi as the starting-point for bringing the Christian gospel to Europe, Paul was accepting a challenge of no mean order.

It is not easy to sort out the confusing religious picture of Macedonia at the time of St Paul’s arrival. Nor would it be accurate to present one characterised by clarity. Each district differed from its neighbour, reflecting the individual peculiarities of its local cultural background and its accessibility to foreign influences.

A Thessalonian coin, dated to the late fourth century B.c., shows that Pallas Athene was worshipped there at the time of the city’s foundation. Another early cult was that of Hercules, to whom particular reverence was paid by the Macedonian kings. Pythian Apollo, on whose advice the Parians had colonised Thasos in the eighth century b.c., and whose worship was consequently particularly strong on that island, was also popularly venerated in Thessalonica, and was often associated on coins with one of the Cabiri.

The Cabiri were two deities of whom we have very little clear knowledge. They were associated with the Great Mother Goddess — Axieros, Cybele or Rhea — whose attendants or children they were. Pre-Greek in origin, they were identified by the Greeks with the Dioscuri. The cult of the Cabiri, with that of the Great Goddess, probably arrived from Asia Minor, whence it established itself upon Samothrace, Lemnos and Thasos, with the first-named as its leading sanctuary. Orpheus was said to have been its pupil there, and Philip II and perhaps Alexander the Great to have visited the island to become initiates of its mysteries. Certainly Alexander and his successors were munificent patrons of the Samothracian temples. On Lemnos the Cabiri were the smiths of the Underworld and it is in this quality that a Cabir sometimes appears on Thessalonian coins. They were also gods with special powers of rescue, particularly of seamen, and this aspect seems to have had a particular attraction for the Thessalonians, who adopted them, usually in a single personification, as the divine protectors of their city, regarding them in a somewhat analagous manner to the Tyches or Fortunes of Syrian cities.

On the evidence of coins of the period, other divinities popular among the Thessalonians included Zeus, Perseus, Artemis, Poseidon and Dionysus. Venus, Mars, Janus and Ceres were among those introduced by the Romans. Egyptian gods, too, had their adherents. An inscription refers to the ‘Great God Serapis ’. The cult of Isis has been revealed by the discovery of a statue of the goddess and the remains of a temple dedicated to her worship which, built during the third century B.c., still apparently warranted repairs in Christian times. The ‘Rosalia’, an annual floral ceremony or fête in commemoration of the death of Attis was celebrated in Thessalonica and Philippi, but opinions differ as to whether this was due to Roman influence or was an import from the shores of Asia Minor.

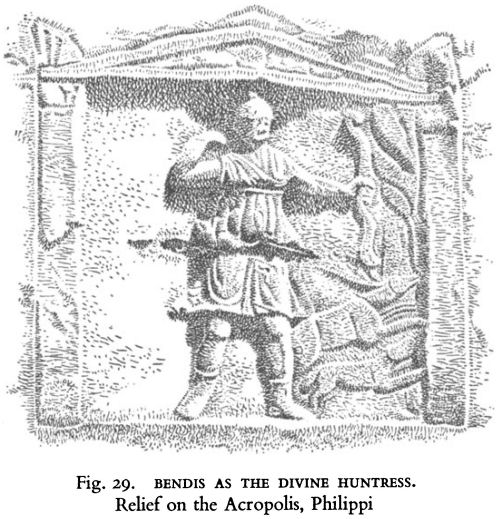

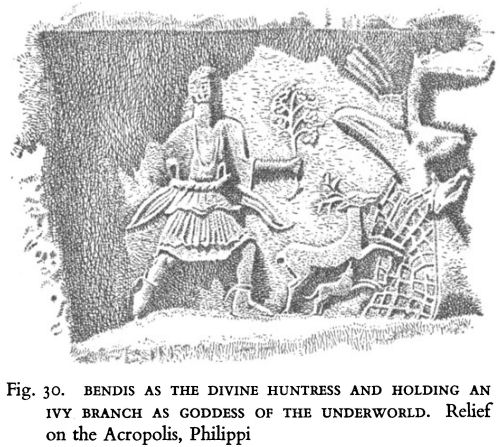

Throughout eastern Macedonia, as well as in Thrace itself, the religion of the native Thracians retained an undiminished vitality. Three iconographical aspects of this religion have survived in sufficient number and consistency of representation to leave us some indication of its essential features. These are the goddess Bendis,the Thracian Horseman, and, to a lesser extent, the Funerary Feast.

Bendis, whose worship was introduced to Attica from Thrace following a treaty between Athens and the Thracian king Sitalces in 430 b.c.,

1. Acts of the Apostles xvi, 12.

52

![]()

Fig. 29. BENDIS AS THE DIVINE HUNTRESS. Relief on the Acropolis, Philippi

Fig. 30. BENDIS AS THE DIVINE HUNTRESS AND HOLDING AN IVY BRANCH AS GODDESS OF THE UNDERWORLD. Relief on the Acropolis, Philippi

and who also appears in Italy as an Etruscan goddess, [1] possessed four distinct personifications. As a huntress goddess, she was armed with a spear or bow and attended by a hound ; in effect, a Thracian equivalent of Artemis-Diana with qualities that indicate a common origin. As a goddess of the underworld and of death, she appeared holding a branch of ivy, introducing a Thracian link into the chain of legends of a ‘Golden Bough’. As a moon goddess, portrayed with a crescent moon, she pointed to a relationship with the Great Mother concept that had been introduced to Thrace from Samothrace and Asia Minor and which was also reflected in certain aspects of Artemis-Diana. Finally, as the feminine hypostasis of the Thracian Horseman, Bendis could be presented standing with the serpent and an altar surmounted by a pine or fir cone or a flame. [2]

Sometimes one aspect emphasised, sometimes another, Bendis was essentially a deeply rooted expression in pagan terms of Thracian belief in rebirth after death. This was perhaps most obvious in the manifestation of the goddess as a deity of the underworld, the most purely Thracian expression of the four. Here her rites were often associated with Dionysus, to whom she would appear as either wife or mother, and to whom the ivy plant, a symbol of immortal life, was sacred» It was also, however, implicit in her appearance as the immortal huntress or the Great Mother.

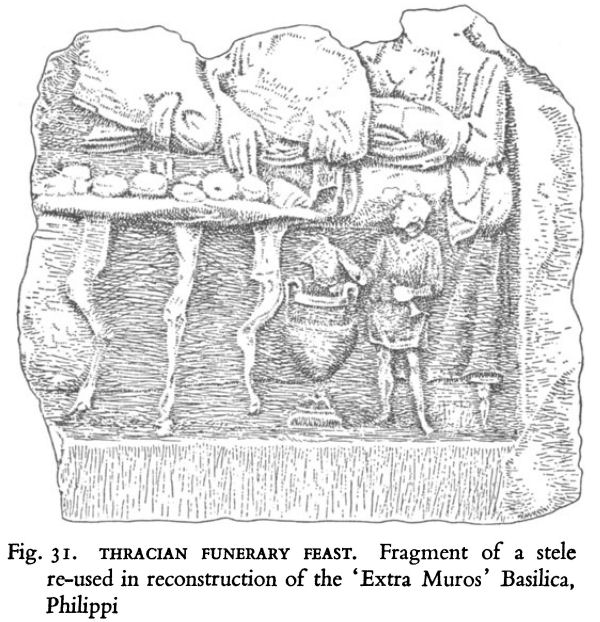

Similarly, the Thracian Horseman and the Funerary Feast were symbols of Thracian belief in an afterlife. The latter motif was common to other areas and combined a primitive pagan form of communion rite with the symbolic provision of food for the deceased.

Fig. 31. Thracian funerary feast. Fragment of a stele re-used in reconstruction of the ‘Extra Muros’ Basilica, Philippi

1. C. Picard, ‘Sur l’iconographic de Bendis’, Sbomik Gabriel Katzarov (Sofia, 1950), pp. 25-34.

2. L. Ognenova, ‘Some aspects of Bendis on the monuments of Thrace’, Bull. Inst. Arch. Bulgare XXII (Sofia, 1959), pp. 81-95 (Bulgarian).

53

![]()

Probably, as Evans has suggested in connection with Mycenaean steles, these sepulchral monuments were originally regarded as baetylic habitations of the departed spirits. [1] The Thracian Horseman, on the other hand, containing elements that are peculiar to Thrace, remains an enigma that still awaits a satisfactory explanation; but some account of it, however tentative, is essential if we are considering the possible legacies of paganism inherited by Christianity in Thrace and eastern Macedonia.

Although the concept of a mounted god or hero occurs elsewhere in the Ancient and indeed in the Modem World (Pls. 4, 6, 7, Figs. 33-37), the large numbers of such monuments discovered in Thrace, all bearing the sign of a clearly defined iconographical tradition, indicate that here it enjoyed a position of exceptional importance. Kazarow reports the existence of over a thousand in Bulgaria [2] and Collart some thirty between the Nestos and the Strymon in the neighbourhood of Philippi. [3] Yet outside territories once inhabited by Thracian tribes it immediately becomes rare and a short distance away is not to be found.

The Thracian Horseman monuments may be either funerary or votive. In the form that has survived to the present day, they are invariably relief carvings on marble or stone. They are small in size, seldom exceeding 0.40 metres in width or height (unless the great rock relief at Mađara (Pl. 7b) is considerably earlier than the ninth-century inscriptions beside it). Its two main iconographic types belong to two different periods. In the earlier, the Horseman is presented as a Heroic Hunter. Bareheaded, dressed in a short tunic and a chlamys which flies behind him in the wind, he gallops, almost always from left to right, towards a tree, around which a serpent is entwined. His right hand is raised and holds a spear or other weapon as if about to strike his quarry. A dog crouches beneath the horse, ready to attack a boar emerging from behind or from the roots of the tree. In the second and later iconographic type the dog and boar are omitted. Sometimes wearing a wreath on his head and sometimes clad in Roman military dress, the Horseman rides in a stately, ceremonial manner towards the serpent-entwined tree, before which now stands an altar surmounted by a pine or fir cone. No longer a Heroic Hunter, the Horseman has become a High Priest or a semi-divine personage participating in a solemn religious ceremony.

A number of variations occur in both types. In the first, examples have been noted in which the boar is omitted and, instead of a spear, the Hunter’s right hand grasps what appears to be a deer or goat at which two dogs leap from below. In a small number of cases the dog and boar together with an altar may appear on a single relief. In the second type, a person, perhaps a servant, is sometimes shown walking behind the Horseman; a seated or standing woman may replace the tree and serpent, and a child even be shown standing upon the altar. Crowding of the scene, however, generally signifies a late and degenerate form. Such examples, which, it would seem, depict living relatives of the deceased, should not be confused with the simple presentation of the Horseman and a seated woman in a clear priest-goddess relationship.

Although these and other exceptions must not be left out of account, the iconography of the two main types is so consistent, despite very varying workmanship, that it may be considered as symbolising a fundamental Thracian religious tenet, which was even strong enough to survive the introduction of new ideas and religious concepts following the Roman conquest of a.d. 46. The presence of these foreign influences in the later type means that it is primarily to the earlier that we must look to provide the surest clues to a satisfactory interpretation. Our first step is, if possible, to identify the Horseman. From the votive nature of the inscriptions accompanying some of the monuments it is clear that it would be wrong to regard him as simply an idealised portrait of a deceased relative, although in a less direct form this concept need not necessarily be entirely absent.

Throughout the latter half of the first millennium b.c. Thrace’s principal neighbouring civilisations were Greek, Scythian and Celtic.

1. A. Evans, Mycenean Tree and Pillar Cult (London, 1901), p. 21.

2. G. I. Kazarow, Die Denkmäler des Thrakischen Reitergottes in Bulgarien (Budapest, 1938).

3. P. Collart, op. cit. p. 299, n. 1.

54

![]()

The last was in a process of eruption and partial disintegration and, as far as can be seen, was then contributing little to Thracian development. On the other hand, particularly during the third quarter of the millennium, Greece and Scythia, both powerful possessors of mature cultures, were in a state of expansion. It was a formative period in the history of the Thracian tribes, who were beginning to achieve a rudimentary form of national consciousness. Greek and Scythian cults that reflected indigenous religious aspirations were thus well situated to exert considerable influence.

One such cult from Greece was that of Asklepios (Aesculapius). Bom of Apollo and a mortal mother, he became renowned for his powers of healing and even of restoring the dead to life. Eventually Zeus, fearing that he might enable men to escape death altogether, struck him dead with a thunderbolt ; but afterwards, on the request of Apollo, granted him the attributes of divinity. Farnell writes :

His incarnation is the snake, at Epidauros, Kos and Rome, and the snake-rod becomes the symbol of the physician ; but this mysterious beast was equally the familiar of the buried hero and of the nether-god. The case is different with the other animal that we now know to have stood in a somewhat mystic relation to him — namely the dog. In many of his shrines we have evidence of the maintenance of sacred dogs, in Epidauros, Athens, Lebena in Crete, and finally in Rome; and at Epidauros at least the animal was possessed of the divine power of the god and was able to work miraculous cures by licking the patient. . . . It is probable that already in Thessaly, the original home of the cult, the animal was closely associated with Asklepios ; for on a bronze coin of the Magnetes of the second century b.c. we see him at the feet of the god. [1]

Asklepios was also one of the heroes who participated in the great boar hunt of Calydon (Pl. 6a).

At a spring renowned for its healing qualities at Glava Panega in Bulgaria, Asklepios was worshipped in association with, and was even to some extent identified with, the Thracian Horseman. Thracian Horseman reliefs have been found there with dedications to Asklepios, and other reliefs which portray Asklepios alone or with Hygeia. [2] There were probably many such shrines, for towards the end of the pre-Christian period, the cult of Asklepios came ‘to overshadow the whole Graeco-Roman world; and when at last vanquished by Christianity it left its impress on the vanquisher’. [3] Its strength in Rome may be an explanation of the easy evolution of the second iconographic type of the Thracian Horseman, in which a compromise was reached between the earlier Hunter cult and the more sophisticated religious practices of Rome.

Asklepios, although especially associated with the serpent, the dog and boar, shared some of his attributes with other gods and heroes, among them his father, Apollo. Another was Attis, with whom a boar figured in the myths concerning his symbolism of rebirth. Consequently, in acknowledging points of similarity between Asklepios and the Thracian Horseman we must not exclude the possibility of other Greek influences. The boar, it must be remembered, was also sacred to Artemis and, among the Indo-European peoples generally, was regarded as a chthonic or infernal beast.

The horse and the tree, iconographically as essential as the rider and persisting for longer than the dog and the boar, loom less strongly in Greek religion, although they are not entirely foreign to it. On the other hand, the nature of Thrace’s Scythian neighbours offers a plausible explanation for the horse. Horses not only bore Scythian warriors to battle and were an important feature of their nomad economy, they were, as we have seen on page 19, interred, often in large numbers, inside the burial mounds of dead chieftains. Thracian princes affected a similar form of burial and Rostovtzeff has drawn attention to the close similarities in the contents and ritualistic observances of Scythian and Thracian tombs.

We are astonished [he writes] to find that the horse trappings are almost the same in the Thracian tombs and in the tombs of South Russia. We find the same pieces ; frontlet, ear-guards, temple-pieces, nasal ; the same Oriental practice of covering nearly the whole bridle with metal plaques ; the same system of bits. Further, the two types of bridle ornament :

1. L. R. Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality (Oxford, 1921), pp. 240-1.

2. N. Vulić, Spomenik xcviii, 1941-48 (Belgrade), pp. 281-6.

3. L. R. Farnell, op. cit. p. 234.

55

![]()

round plaques embossed in the Greek manner ; and plaques in the form of animals, cast and incised in the Oriental fashion. Lastly, and this is the most important of all : all the pieces in the animal style find striking parallels in the Scythian horse trappings from Scythian tombs of the fourth and third centuries . . . some of these are almost duplicates. [1]

If Scythian influence was as strong as this evidence of the Thracian mound burials implies, it would have been unnatural indeed to have portrayed otherwise than mounted a god, a hero or even a dead relative to whom respect was being accorded.

Nevertheless, the horse would not have become a fundamental item of Thracian funerary iconography simply through a tendency to copy Scythian customs. It had been generally regarded as an animal with divine attributes by the Indo-European peoples and, as we have already noted in Chapter I, the solar chariot was a symbol shared by Greece, Rome, Persia and India. Salin has summarised the symbolism of the horse in terms which, although intended to be general, are fully applicable to the reliefs of the Thracian Horseman :

Companion of the nomad, the horse, after the cervidae it succeeded, was taken by him as a totem at a time when zoomorphism preceded anthropomorphism. But he is also the companion of the dead man, whom he accompanies into the tomb for the supreme journey : the myth originates from the burial of the dead with the horse (or chariot) ; it will not be limited to one people, one religion or one age. ... In the first place, in fact, it (the horse) is the sacred animal of those religions which are essentially chthonian ; represented alone, it is the image of death. But it also evokes the presence of the dead man beside whom it was buried ; it protects him ; and finally becomes confused with him : as the mount of the heroised horseman, it bears him on a posthumous ride towards the empyrean, the sun or the moon.

Thus the horse becomes a symbol of immortality ; from being chthonian it becomes uranian, and with this conception are associated the allegorical designs linking or substituting for one another the horse and the bird, opposing the horse to the serpent according to a symbolism which evokes the eternal combat of two opposed powers : the sky and the earth.

In short, the horse, whose power is on the frontier of two worlds, appears as the protector both of the living and the dead. . . .

The horse is a mount for the hunter who fights against monsters — and this is the victory of Good over Evil ; but he also leads the infernal hunt ‘in which the Beyond is let loose’, which may make the horse a demon. Thus it is sometimes beneficent and sometimes maleficent. [2]

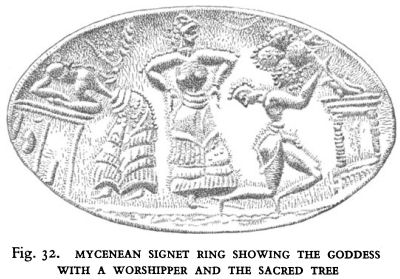

The tree poses a wide and a particularly confusing range of questions. Does it represent the Tree of Life ? Is the serpent entwined around its trunk linked with the Oriental myth that gave us the story of the Garden of Eden — here expressing a Thracian combination of Greek and Oriental ideas of rebirth ? Is it a relic of tree worship, a widespread form of primitive religion particularly among the Celtic peoples with whom Thrace had close contacts and whose period of cultural influence antedated that of the Scythians ? Does some connection exist between it and the ancient oak grove oracle of Zeus at Dodona ? Or has it Mycenean associations ? Mycenae and Mycenean Crete, where the serpent was also sacred, provide precedents of religious ceremonies in which a human figure approaches a sacred tree to pluck its fruit. Discussing a gold signet ring (Fig. 32) from a Mycenae chamber tomb, Evans comments :

The subject will be best understood if we regard it as divided into separate scenes. To the right, the Goddess is thrown into an ecstatic state by the fruit of her sacred tree, a branch of which is here again pulled down for her by the male attendant.

Fig. 32. MYCENEAN SIGNET RING SHOWING THE GODDESS WITH A WORSHIPPER AND THE SACRED TREE

1. M. RostovtzefF, Iranians and Greeks in South Russia (Oxford, 1922), p. 89.

2. E. Salin, La Civilisation mérovingienne (Paris, 1959), vol. iv, pp. 148-9 (trans.).

56

![]()

The other side of the subject depicts a similar figure in a mourning attitude, leaning over a little enclosure within which stands a small baetylic pillar while from the upper part of the balustrade is suspended a diminutive Minoan shield, seen in profile, clearly belonging to the youthful personage. . . . We seem in these cases, indeed, to have actual illustrations of an aspect of the religion so prominent in the later cult of Adonis and Attis, the child or favourite of the Goddess, cut off before his prime by some untoward accident which in Crete, as in Syria, seems also to have been due to a wild boar. [1]

In the light of our present knowledge we can do little more than guess at the symbolism of the snake-entwined tree. That it implies Greek influence seems likely, for on reliefs from the remoter parts of Thraco-Moesia it is frequently omitted.

So far we have been considering the potential impact of foreign influences, but these must not obscure the most clearly evident fact of all — the essentially national character of the monument. Can we find a native Thracian figure — man, hero or god — capable of amalgamating Greek, Scythian and other ideas into a Thracian mould ?

Casson has pointed out that the Horseman cult ‘seems in origin to have some sort of connection with the legend of Rhesus ... a great Thracian hero whose very presence inspires awe and fills the air with splendour and the clash of arms’. [2] Rhesus was the semi-divine son of the River Strymon and one of the Muses. A mighty warrior, famous for the beauty and fleetness of his white horses, he arrives belatedly at Troy as an ally of the Trojans, after delays due to Scythian wars on his northern borders. According to Homer and as dramatised by Euripides, he was slain in his sleep by Odysseus and Diomedes, son of Tydeus, on the night of his arrival and was buried on the fields of Troy.

The most remarkable passage in Euripides’ play, suggests Porter, is the ‘allusive and obscure’ prophecy by Rhesus’ mother of a posthumous existence for the dead hero that was quite alien to Homeric tradition (w. 962-73). The passage is translated thus :

He shall not descend into the dark earth ; this much I beg of the Nether Bride, daughter of Demeter, the goddess who giveth the fruits of the earth, to send up his soul from the dead. And she is my debtor to show manifest honour to the kinsfolk of Orpheus. And although to me he shall be as dead henceforth and as one who sees not the light, for neither shall he meet me any more nor look upon his mother’s face, yet he shall he concealed in the caverns of the silver-bearing land, a Spirit-Man, beholding the light, even as the seer of Bacchus made his habitation in Pangaeum’s rock, a god revered by those who understand. [3]

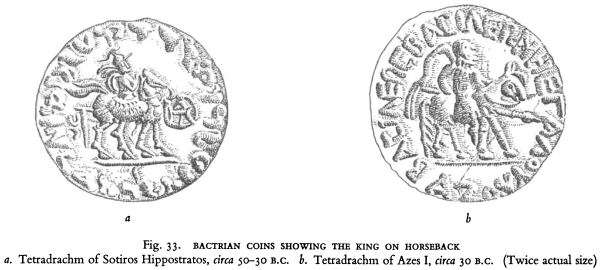

From a Greek writer comes an interesting epilogue to the Trojan episode. We are told by Polyaenus that Hagnon, attempting to found an Athenian colony at Amphipolis in 437-436 B.C., sent an expedition to Troy to bring back the bones of the Thracian hero in order to bury them within the precincts of the colony, presumably as an act of propitiation to the local gods or to impress the fierce Thracian tribes of the neighbourhood. A coin of Seuthes I, King of Odrysian Thrace 424-405 B.C., which bears a Thracian Horseman on the obverse, shows that the symbol — and, in consequence, whatever myth it represented — had become a factor in the national consciousness before the end of the fifth century b.c. (Pl. 6d). Four centuries later, in a somewhat more sophisticated form, it was appearing on coins of the Hellenistic kingdom of Bactria (Fig. 33).

Among the Thracians a primitive legend seems to have existed that Rhesus was killed in Thrace fighting the savage Diomedes, son of Ares, perhaps a reflection of the wars between the Thracians and the first Greek settlers. [4] Philostratus, writing in the first half of the third century a.d., speaks of a shrine of Rhesus on Mount Rhodope. Although he accepts Homer’s version of the Thracian hero’s death, he implies a local ignorance of it :

Rhesus, whom Diomedes slew at Troy, is said to inhabit Rhodope, and they recount many wondrous deeds of his ; for they say that he breeds horses, and marches in armour, and hunts wild beasts ; and, in proof that the hero is a hunter, they tell how the wild boar

1. A. Evans, The Earlier Religion of Greece in the Light of Cretan Discoveries (London, 1931), p. 31.

2. S. Casson, Macedonia, Thrace and Illyria (Oxford, 1926), p. 248.

3. W. H. Porter (ed.), Euripides : Rhesus (Cambridge, 1916), p. xvii.

4. W. H. Porter, op. cit. p. xxv; Pauly-Wissowa, RealEncyclop., s.v. Diomedes.

57

![]()

and gazelles and all the beasts of the mountain come by twos and threes to the altar of Rhesus, and are offered in sacrifice, unbound and unfettered, and yield themselves to the knife ; and this hero is said to ward off plague from his borders. [1]

Fig. 33. BACTRIAN COINS SHOWING THE KING ON HORSEBACK a. Tetradrachm of Sotiros Hippostratos, circa 50-30 B.c. b. Tetradrachm of Azes I, circa 30 b.c. (Twice actual size)

The concept of a legendary king, a father figure of his race and so developed into a heroic or semidivine ancestor of the whole Thracian people, is in fundamental accord with the view expressed by Vulić that the Thracian Horseman is ‘an ancestor, a heroised ancestor, or, still more likely, heroised ancestors’. [2] To such could be attributed all the qualities which the Thracians considered appropriate to a god and with him every Thracian could identify himself in his anticipated after-life when, with the Hero’s aid, death could be vanquished. It was a natural corollary, to which the accretion of the Asklepian attributes could have made an important contribution, that such a hero might be expected to provide certain forms of protection during the mortal existence of his followers. That these mortal forms included defence as well as healing is shown by inscriptions in which the epithet προπυλαίος is used to invoke the Horseman’s aid, and by the incorporation of Horseman tablets in fortified city gateways. [3]

Thus, it is likely that the Thracian Horseman was a composite figure, essentially Thracian and centred on the legendary personality of King Rhesus, but to which Greek, Scythian and probably other myths made important contributions. On the basis of our present knowledge it would probably be unwise to attempt a much closer definition or, indeed, even to regard this suggested identity as more than tentative.

Three related iconographic forms, which, although present in Thrace, were rather symbols of similar concepts developed by neighbouring peoples, are worth noting briefly for the perspective in which they place the Thracian Horseman for us. The first presents a Horseman, his right hand raised, advancing towards a seated female goddess who holds a leafy branch. This scene is reproduced almost identically on a Thasian stele (Pl. 6b), considered by Collart to be the assimilation of two heroised dead into the Heroic Horseman-Dionysus and Bendis-Persephone, [4] and on a Scythian textile from the circa fifth century b.c. grave at Pazarik in the Altai (Pl. 6c). It appears again on a gold finger ring found in a Thracian mound tomb at Brezovo, near Plovdiv in Bulgaria. Here an intaglio design represents a mounted horseman facing a draped female figure who holds out a rhyton. Rostovtzeff explains this scene as a royal investiture or holy communion and comments that it is common on objects from fourth- or third-century Scythian tombs in South Russia. [5] Horseman reliefs bearing a female figure are relatively common in Bulgaria and, despite identifications with Asklepios and Hygeia, there

1. W. H. Porter, op. cit. p. xxv.

2. N. Vulić, op. cit. pp. 281-6.

3. S. Casson, op. cit. pp. 251-3 ; P. Collart, op. cit. p. 468 ; G. Seure, ‘Études sur quelques types curieux du Cavalier Thrace’, Revue des Études Anciennes, xiv, 1912, p. 382, et seq.

4. P Collart, op. cit. p. 437.

5. M. Rostovtzeff, op. cit. p. 89.

58

![]()

the symbol may indicate a closer relationship with Scythian than Hellenic origins. An analogous form appears in East Syria. In the Semitic example illustrated in Pl. ηα sun and moon symbols and a flaming altar are substituted for the goddess, and Arsu, the god of caravans, is the hero, here riding a camel. Parthian reliefs from the same region show the hero-god on horseback advancing towards an altar beside which stands a male god. In the relief from Khirbetel-Hamam the god holds out a wreath. [1]

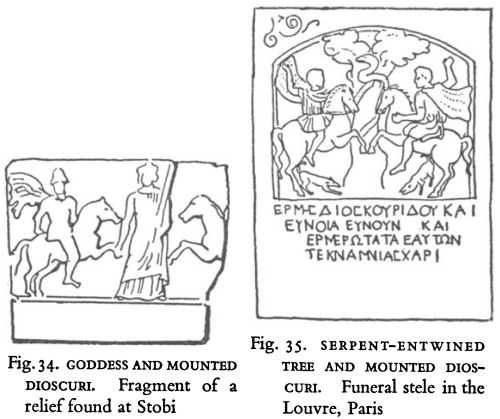

The second iconographic form is that found in south-west Asia Minor of Artemis flanked by the mounted Dioscuri (Pl. 4c). Evidence of this cult has been found at Stobi (Fig. 34) and elsewhere in Macedonia. Here, as in the Louvre stele displaying opposing Horsemen with dogs separated by a serpent-entwined tree (Fig. 35), it achieved a degree of integration with that of the Thracian Horseman. However, reliefs of dual Horsemen are relatively rare in the areas where the population contained a strong Thracian element, a point which leads us to wonder if the Thracian symbol of a single Heroic Horseman may have played a significant part in Thessalonica’s insistence upon a single personification of the Cabiri.

Fig. 34. GODDESS AND MOUNTED DIOSCURI. Fragment of a relief found at Stobi

Fig. 35. SERPENT-ENTWINED TREE AND MOUNTED DIOSCURI. Funeral stele in the Louvre, Paris

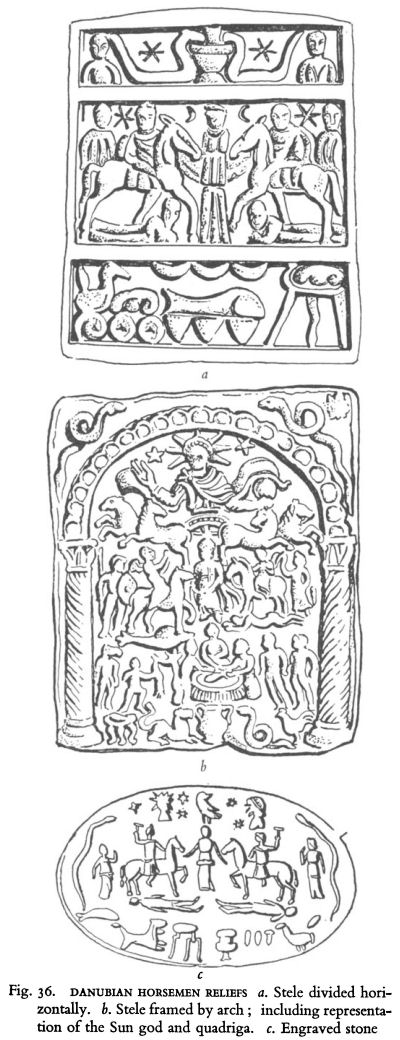

Fig. 36. danubian horsemen reliefs a. Stele divided horizontally. b. Stele framed by arch ; including representation of the Sun god and quadriga, c. Engraved stone

The third related form is that usually known as the Danubian Horseman.

1. The Excavations at Dura Europos (Preliminary Report of Sixth Session) (New Haven, 1936), pp. 228-38 and Pl. xxx.

59

![]()

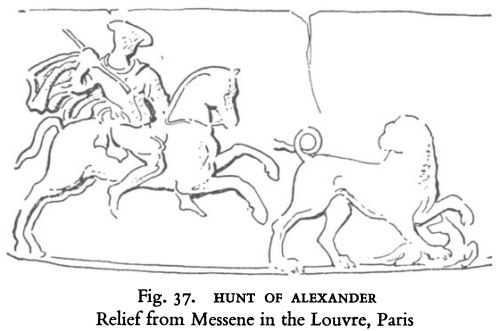

Here either two opposed Horsemen flank a Mother Goddess, as in the Pisidian Artemis (Pl. 4c), or a single one rides towards her ; but a customary feature is a recumbent man beneath the hooves of each horse. Usually the Danubian Horseman appears on steles accompanied by a hotchpotch of other expressions of beliefs in immortality (Figs. 36a-c). Like Ephesian and Pisidian Artemis, its origin is Asiatic rather than Hellenic and its iconography should not be confused with the well-known stele of Dexileos, where the figure of a rider striking down a barbarian figure beneath his horse’s hooves probably represents a triumphant episode from the deceased man’s life rather than a deeply rooted religious symbol. Such Greek sculptures as this stele and others of a like nature undoubtedly exerted a stylistic influence on the iconography of the Thracian Horseman — many of the finer examples of which may be attributed to Greek craftsmen — but style and concept must not be confused. More akin to the Horseman is the relief from Messene in the Louvre showing the Hunt (not the victory) of Alexander (Fig. 37). The victorious action of the Danubian Horsemen may be a reflection of that dualism inherent in the Iranian religion of which many of the inhabitants of the Danube valley were distant followers.

Fig. 37. HUNT OF ALEXANDER. Relief from Messene in the Louvre, Paris

Along the imperial frontiers garrisoned by legions which included troops from Thrace and Asia Minor and, occasionally, within Thracian territory, a Horseman, stylistically recognisable as of the Thracian type but trampling a defeated warrior beneath his horse’s hooves, appears on funerary steles. None of these examples, three of which occur at Philippi, possess the remaining iconographical features of the Thracian Horseman reliefs. Sometimes, as at Hexham in Northumberland, the triumphant Horseman is hardly recognisable as Thracian and perhaps has no connection. In an example preserved at Gloucester, however, the deceased is not only stylistically presented as a Thracian type, but is identified in the accompanying inscription as a Thracian cavalryman. In spite of this, the figure we see is that of a Roman soldier victorious over his barbarian adversary. It is in the tradition of Dexileos rather than the Thracian Horseman and, if any form of religious symbolism is present, it has little relationship with that of either Thrace or Greece.

Whatever else is open to doubt, the Thracian Horseman symbolised a powerful Thracian religious concept. Did it then leave an impression upon Christianity, either in association with cults such as that of Asklepios or in a more specifically Thracian form ?

The major Christian hero of Byzantine Thessalonica and its neighbourhood was St Demetrius, whose divine attributes, as we shall see when discussing the Slav invasions and the Basilica of St Demetrius, were healing and the protection of his followers. The cult centre of the saint was situated in the crypt of the basilica of St Demetrius in Thessalonica, the alleged scene of his martyrdom. He was claimed in similar terms by the Danubian city of Sirmium, although we lack details of his cult centre there. This plurality of cult centre and use of a crypt is paralleled in the cult of Asklepios, of which Farnell comments :

There was always great resemblance between the ritual at a buried hero’s tomb and that at the underground shrine of the earth deity or daimon ; therefore in certain cases it might be hard to determine whether the personage belonged to one or the other class ; and in the shifting popular tradition the one could easily be transformed into the other. . . . And here and there in the records of the ritual we may detect other chthonian features ; at Trikka, according to the hymn of Isullos, the shrine was a nether ‘aduton’, and the subterranean structure may have prevailed elsewhere, accounting for the rise of a legend that such and such communities possessed the tomb of Asklepios. [1]

1. L. R. Farnell, op. cit. p. 237.

60

![]()

At the outset of his spiritual existence as a Christian hero, St Demetrius was a divine hero in the pure Asklepian tradition and not a Christianised version of the Thracian Horseman. This was not surprising in such a predominantly Greek city as Thessalonica and in view of the pacific temper of Early Christianity. On the other hand, he was never accorded the serpent and dog as sacred animals. Were these discredited as being too obviously pagan symbols ? Nevertheless, we shall see when discussing the mosaics of the Basilica of St Demetrius that within a couple of centuries and probably earlier the saint had entered into mystic relationships with the Virgin and with a ‘lady Evtaxia’ comparable with those of Asklepios and Hygeia, the Thracian Horseman and Bendis, the Cabiri and the Great Mother Goddess, Dionysus and Persephone, Attis and Cybele, Apollo and the Earth Mother Goddess, the Scythian Horseman and the Great Goddess and their many variations. Perhaps this swing towards a relationship with a goddess was an indication of the influences from Asia Minor which were always strong in Macedonian religion, whether Christian or pagan, and which the Semitic fervour of St Paul only temporarily succeeded in replacing with a monotheism that was purely masculine. (In a discussion of Delphic cultural traditions, Dyggve suggests that the earlier Apollo-Earth Mother Goddess relationship at that centre was transformed into one between John the Baptist and the Virgin, and recalls that scented water was a feature of the pagan cult as well as of that of St Demetrius in Thessalonica. [1] Not until later, when the danger to Thessalonica from the Avars and Slavs became acute, did St Demetrius assume in a most splendid and effective manner all the apotropaic powers earlier attributed to the Cabiri and to the Thracian Horseman. Significantly, in Greek iconography he remained unmounted ; but the Slavs, with their ancient Scythian traditions, were quick to picture him on horseback.

Yet among the Slavs it was Cappadocian St George, rather than the Thessalonian hero St Demetrius, who inherited the iconographical form of the Thracian Horseman (Pl. 7d-f), as he did elsewhere those of Bellerophon, Perseus and other heroes. If Galerius’s Rotunda was dedicated to St George from its earliest period as a Christian church, this saint may originally have been a rival of St Demetrius for the role of Thessalonica’s Christian hero. The city’s fierce civic patriotism probably weighed the scales in favour of the local Greek martyr, but beyond the immediate environs a different situation prevailed. In the deeply rooted local traditions of a Heroic Horseman the Slavs found even centuries later the prototype for a hero in whom they could personify their own ideals. This Slav symbol took either the form of the mediaeval Serbian legendary hero Marko, whose character included barbaric aspects as well as idealism, but who was ready with his horse Sharatz to rise and ride to the assistance of his people in their time of need, [2] or that of St George, the champion of Christian virtue against the dragon, locally a synthesis of the boar and serpent as elsewhere it had succeeded such monsters as the Chimaera.

An important Serbian example of the influence of the Thracian Horseman in Christian iconography appears in the badly damaged wall painting of St George in the ruins of Djurdjevi Stupovi (the Towers of St George) (circa 1168), one of the first churches to be built by the Serbian king Stefan Nemanja (Pl. 7d). Sotiriou cites a mediaeval wooden icon of St George found at Thracian Heraclea as another example of local association of the two. He describes it as coarse local art and points out that with the horse’s movement, the saint’s cushioned hair and short trousers, it is more like the Thracian hero than St George fighting the dragon or any of the other saints portrayed in late Byzantine art. [3] Even in the figure of St George on the nineteenth-century iconostasis of the church of Sveti Spas in Skopje (Pl. 7f) the iconography has undergone remarkably little change.

Finally, we may note a non-iconographical point mentioned by Vulić in his study of the Thracian Horseman. At Glava Panega, the healing spring

1. E. Dyggve, ‘Les Traditions cultuelles de Delphes et l’Église chrétienne*, Cahiers Archéologiques, iii (Paris, 1948), pp. 15-16 and 28, n. I.

2. D. Srejović, Les Anciens Éléments balkaniques dans la figure de Marko Kraljević (Živa Antika, VIII, vol. i, Skopje, 1958), pp. 75-973.

3. G. A. Sotiriou, La Sculpture sur bois dans l'art byzantin, in Mélanges Charles Diehl (Paris, 1930), vol. 2, p. 177.

61

![]()

where the reliefs of Asklepios and the Thracian Horseman were discovered together, as late as 1907 peasants were still making pilgrimages to seek cures for their illnesses on St George’s Day. [1]

Thrace itself maintained a peculiar hold over Western imagination. Richard Johnson, in his sixteenth-century blend of ancient and mediaeval legend, The Seven Champions of Christendom, apportions major Thracian adventures to SS. Anthony, Andrew and Patrick. Moreover, after the more obviously fanciful details have been deducted, his descriptions of the country and its inhabitants are not without some relation to fact. It is of interest, too, to note parallels in Mummers’ plays that were still being performed in England in the first half of this century with similarly extant Macedonian versions of the St George legend. [2]

At the western edge of the plain of Philippi rises Mount Pangaeus, dominating the surrounding countryside. To its thickly wooded, mysteriously folded slopes and brooding peaks, legend attributed the birthplace of Dionysus. This part of eastern Macedonia had been one of the earliest centres of Dionysian worship, which perhaps spread from here to Greece. Developed locally as a Thraco-Hellenic cult, it profoundly influenced the religious thought of Greek and Thracian alike. The latter associated Dionysus with their belief in an after-life, not only in connection with Bendis, but, as can be seen on steles at Melnik and Thasos, sometimes actually identifying him with the Heroic Hunter. Inscriptions of the Roman period found in the neighbourhood of Philippi prove the existence of ‘thiasi’, Dionysian brotherhoods of a mystical character whose membership included Romans but were for the most part Thracian. Among these inscriptions is a child’s epitaph in late Latin which speaks of the bliss that awaited Dionysiacs in their future life.

In the shadow of Mount Pangaeus, itself an everpresent reminder of the ancient god, the worship of Dionysus presented a formidable adversary to Christianity. How strong must have been the atmosphere of paganism then can be glimpsed in the fact that even to-day one may climb the acropolis of the nearby island of Thasos and find in a grove of ancient olives a rock sanctuary dedicated to Pan, still (in 1958), after more than two millennia, undefiled by the carved initials of vandal sightseers. In the time of Paul, the older gods were not legends but a living, present force. Although the Roman colonists of Philippi had imported their own gods, it seems that not even Roman prestige and a population, the most powerful classes of which were Roman, influenced the religious beliefs of the indigenous inhabitants to any appreciable extent. Rather was it the reverse.

At a much earlier period, cults originating from Asia Minor and Egypt had attained an enduring place in the religious life of eastern Macedonia. Most prominent among them were the Great Mother Goddess (but not, as far as is known, the Cabiri) from Asia Minor and Samothrace, and Isis, Serapis, and Horus-Harpocrates from Egypt. But these had introduced no new religious principle in any way antagonistic to the indigenous beliefs. All shared, as a fundamental principle, a belief that the faithful would be rewarded by rebirth into Paradise. In some respects, these cults had prepared the way for Christianity, but they also presented grave dangers. Paul had probably sound reasons for adding to his epistle to the Philippians a warning note telling them to ‘beware of evil workers’. [3] And, with psychological genius he presented an ethical, Christian alternative to the thiasi :

Rejoice in the Lord alway ; and again I say, Rejoice.

Let your moderation be known unto all men. The Lord is at hand.

Be careful for nothing ; but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known unto God.

And the peace of God, which passeth all understanding, shall keep your hearts and minds through Christ Jesus.

Finally, brethren, whatsoever things are true, whatsoever things are honest, whatsoever things are just, whatsoever things are pure, whatsoever things are lovely, whatsoever things are of good report ; if there be any virtue, and if there be any praise, think on these things . . . and the God of Peace shall be with you. [4]

The Acts of the Apostles give the following description of Paul’s first visit to Macedonia :

1. N. Vulić, op. cit. p. 284.

2. G. F. Abbott, Macedonian Folklore (London, 1903).

3. Philippians iii, 2.

4. Philippians iv, 4.9.

62

![]()

Therefore loosing from Troas, we came with a straight course to Samothracia, and the next day to Neapolis ;

And from thence to Philippi, which is the chief city of that part of Macedonia, and a colony : and we were in that city abiding certain days.

And on the sabbath we went out of the city by a river side, where prayer was wont to be made ; and we sat down, and spake unto the women which resorted thither.

And a certain woman named Lydia, a seller of purple, of the city of Thyatira, which worshipped God, heard us ; whose heart the Lord opened, that she attended unto the things which were spoken of Paul.

And when she was baptized, and her household, she besought us, saying, ‘If ye have judged me to be faithful to the Lord, come into my house, and abide there.’ And she constrained us.

And it came to pass, as we went to prayer, a certain damsel possessed with a spirit of divination met us, which brought her masters much gain by soothsaying : The same followed Paul and us, and cried, saying, ‘These men are the servants of the most high God, which shew unto us the way of salvation.’

And this did she many days. But Paul, being grieved, turned and said to the spirit, ‘ I command thee in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her’. And he came out the same hour.

And when her masters saw that the hope of their gains was gone, they caught Paul and Silas, and drew them into the marketplace unto the rulers.

And brought them to the magistrates, saying, ‘These men, being Jews, do exceedingly trouble our city.

‘And teach customs, which are not lawful for us to receive, neither to observe, being Romans.’

And the multitude rose up together against them : and the magistrates rent off their clothes, and commanded to beat them.

And when they had laid many stripes upon them, they cast them into prison, charging the jailor to keep them safely :

Who having received such a charge, thrust them, into the inner prison, and made their feet fast in the stocks.

And at midnight Paul and Silas prayed, and sang praises unto God : and the prisoners heard them.

And suddenly there was a great earthquake, so that the foundations of the prison were shaken : and immediately all the doors were opened, and every one’s bands were loosed.

And the keeper of the prison awaking out of his sleep, and seeing the prison doors open, he drew out his sword, and would have killed himself, supposing that the prisoners had been fled.

But Paul cried with a loud voice, saying, ‘Do thyself no harm : for we are all here.’

Then he called for a light, and sprang in, and came trembling, and fell down before Paul and Silas.

And brought them out, and said, ‘ Sirs, what must I do to be saved ?’

And they said, ‘Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved, and thy house.’

And they spake unto him the word of the Lord, and to all that were in his house.

And he took them the same hour of the night, and washed their stripes ; and was baptized, he and all his, straightway.

And when he had brought them into his house, he set meat before them, and rejoiced, believing in God with all his house.

And when it was day, the magistrates sent the serjeants, saying, ‘Let those men go.’

And the keeper of the prison told this saying to Paul, ‘The magistrates have sent to let you go : now therefore depart, and go in peace.’

But Paul said unto them, ‘They have beaten us openly uncondemned, being Romans, and have cast us into prison ; and now do they thrust us out privily ? nay verily ; but let them come themselves and fetch us out.’

And the serjeants told these words unto the magistrates : and they feared, when they heard that they were Romans.

And they came and besought them, and brought them out, and desired them to depart out of the city.

And they went out of the prison, and entered into the house of Lydia : and when they had seen the brethren, they comforted them, and departed.

Now when they had passed through Amphipolis and Apollonia, they came to Thessalonica, where was a synagogue of the Jews :

And Paul, as his manner was, went in unto them, and three sabbath days reasoned with them out of the scriptures.

Opening and alleging, that Christ must needs have suffered, and risen again from the dead : and that this Jesus, whom I preach unto you, is Christ.

And some of them believed, and consorted with Paul and Silas ; and of the devout Greeks a great multitude, and of the chief women not a few.

63

![]()

But the Jews which believed not, moved with envy, took unto them certain lewd fellows of the baser sort, and gathered a company, and set all the city on an uproar, and assaulted the house of Jason, and sought to bring them out to the people.

And when they found them not, they drew Jason and certain brethren unto the rulers of the city, crying, ‘These that have turned the world upside down are come hither also ; Whom Jason hath received : and these all do contrary to the decrees of Caesar, saying that there is another king, one Jesus.’

And they troubled the people and the rulers of the city, when they heard these things.

And when they had taken security of Jason, and of the other, they let them go.

And the brethren immediately sent away Paul and Silas by night unto Berea (Verria) : who coming thither went into the synagogue of the Jews.

These were more noble than those in Thessalonica, in that they received the word with all readiness of mind, and searched the scriptures daily, whether those things were so.

Therefore many of them believed ; also of honourable women which were Greeks and of men, not a few.

But when the Jews of Thessalonica had knowledge that the word of God was preached of Paul at Berea, they came thither also, and stirred up the people.

And then immediately the brethren sent away Paul to go as it were to the sea : but Silas and Timotheus abode there still.

And they that conducted Paul brought him unto Athens ; and receiving a commandment unto Silas and Timotheus for to come to him with all speed, they departed.

Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry. [1]

The traveller of to-day who takes a car or bus from Neapolis to Philippi must retrace much of the Via Egnatia along which Paul and his companions walked. At Philippi, where at least one inscription has been found referring to dealers in purple dyes, Paul, as had been his custom in Asia Minor, waited for the Sabbath before making an attempt to preach his gospel. For the first time, however, he was adventuring into a city where the Jewish population was negligible. There was no synagogue in Philippi, and so Paul and his companions ‘went out of the city by a river side, where prayer was wont to be made ; and (we) sat down, and spake unto the women which resorted thither’.

One feels that Paul must have attached a very considerable importance to Philippi to have acted thus. Was it because he had set as his lifework his mission to the Gentiles? Was it the influence of Timotheus, whose father was Greek? Was it because he found among certain of the Philippians an unusual sympathy towards his message? The last may or may not have been a reason for his stay in the city, but from the affection with which he afterwards always spoke of his followers there it would seem to be true. In his epistle to the community of Philippi, he almost goes out of his way to say : ‘ Now ye Philippians know also, that in the beginning of the gospel, when I departed from Macedonia, no church communicated with me as concerning giving and receiving but ye only. For even in Thessalonica ye sent once and again unto my necessity.’ [2] The Macedonian Jews were responsible for hounding him from Thessalonica and Verria, but he met with no such vindictive opposition in Philippi. Probably, as Lemerle has pointed out, most of the followers of Judaism were likely to have been Gentile converts to its principles rather than circumcised Jews. [3] Paul’s troubles in Philippi stemmed only from his having put an end to the lucrative profits which some men had been enjoying through their exploitation of a poor half-witted girl’s facility in telling fortunes. These accused him only of teaching (Jewish) ‘customs, which are not lawful for us to receive, being Romans’. In Philippi the chronicler of the Acts of the Apostles records no opposition to Paul’s preaching of the Christian doctrine of the resurrection.

In Thessalonica and Verria a particular welcome was given to Paul’s gospel by the Greek population, ‘devout Greeks’ as they are called on one occasion. The race of those who received him with such warmth in Philippi is not specified ; and nowhere are the indigenous Thracians or Illyrians mentioned. It seems a possibility that, particularly in Philippi, Paul made no distinction between the Greeks and the urban, Hellenised Thracians.

1. Acts of the Apostles xvi and xvii.

2. Philippians iv, 15 and 16.

3. P. Lemerle, Philippes et la Macédoine Orientale (Paris, 1945), p. 29.

64

![]()

Both were eligible for Roman citizenship. Both would speak Greek. Both, too, practised a synthesis of Thracian and Hellenic cults, which would have prepared them for Christian ideas. The status of women in Illyrian society may, too, have been the reason for the interest shown in Thessalonica and Verria by ‘ chief’ and ‘honourable women which were Greeks’. Educated, urban Illyrians, too, would have spoken Greek.

Macedonia continued to figure prominently in the missionary field after Paul’s departure. Within a year or so the province was revisited by Timotheus and Erastus. Meanwhile, Gaius and Aristarchus, the only two companions of Paul in Asia Minor who are identified in the Acts of the Apostles, were both Macedonians. The Acts contain no description of Paul’s second and third visits, made on his way to and from Greece;

but the names of those who accompanied him to Asia Minor on his way to Jerusalem include Sopater of Verria and Aristarchus and Secundus of Thessalonica, the other four being identified as coming from the Roman provinces of Asia.

A final point of special interest in the narrative of the Acts of the Apostles is that following his extensive travels in Roman Asia Minor and Macedonia, Paul reacted so strongly to finding Athens ‘wholly given to idolatry’. Until he reached Athens, his natural, traditional, Jewish aversion to graven images does not appear to have been seriously affronted. Here, however, Paul was moved to the first Christian expression of iconoclasm, later to develop into such a violent source of contention between the Greek and Oriental parts of the Byzantine Church.

Chapter V. The Centuries of Persecution and the First Gothic Invasions

With regard to Macedonia’s contribution to the evolution of Christian doctrine in its first centuries, it is significant, perhaps, that none of the early fathers whose writings were the basis of the formulation of this doctrine wrote from the province. Possibly there was no one with anything particularly constructive to add to that which was coming from other centres. Possibly there was no one with an exceptional gift of the pen. On the other hand it must be remembered that Macedonia and the Via Egnatia were of vital strategic importance to the Roman Empire during the second and third centuries. Roman control over the civil population would have been strict, and would have allowed little latitude to the activities of ‘subversive’ religions. Even so, Tertullian, writing his De Prescriptione Haereticomm at the beginning of the third century, rated Philippi as the leading Christian ecclesia of Macedonia and placed it on a level of orthodoxy and authority with those of Rome, Corinth and Ephesus :

Age jam, qui voles curiositatem melius exercere in negotio salutis suae, percurre ecclesias apostolicas, apud quas ipsae adhuc cathedrae apostolorum suis locis praesident ; apud quas ipsae authenticae litterae eorum recitantur, sonantes voces et repraesentantes faciem uniuscujusque. Proxima est tibi Achats : habes Corinthum ; si non longe es a Macedonia, habes Philippos ; si potes in Asiam tendere, habes Ephesum ; si autem Italiae adjaces, habes Romam.

If not in doctrine, certainly in other aspects an essentially Macedonian impact upon Christianity is evident. Thessalonica, as we have seen, was able to transfer the attributes of pagan heroes to its Christian patron saint, St Demetrius. The same city, with the enthusiastic support of the province as a whole, was also an early protagonist of the Virgin as the acknowledged Mother of the divine — as distinct from the human — Christ. Although partly inspired by political motives, the fervour induced by the Nestorian controversy points also to deeply rooted religious feelings. This is hardly surprising when the strength of the centuries’ long experience of variations on the Great Mother Goddess theme is recalled. We shall follow the translation of this emotion into Christian art when discussing the Thessalonian churches of St Demetrius and ‘Acheiropoietos’.

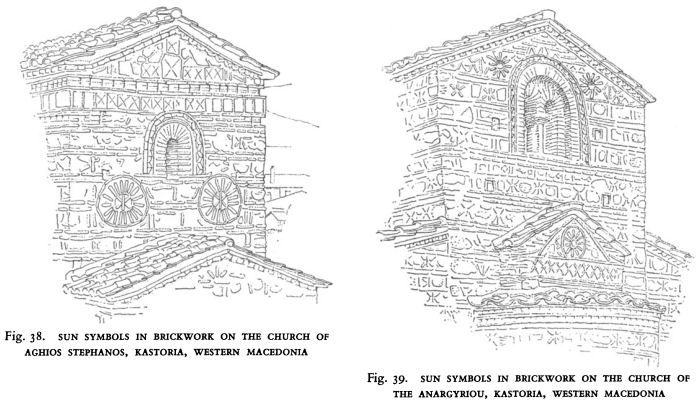

Clearly, the degree to which the pre-Christian religious beliefs of Macedonia affected Christianity during the formative first three centuries of its era must remain a question mark. It may have been considerable ; it is unlikely that it was negligible. Certainly, the dominant pagan influence came from the eastern or Thracian region of Macedonia rather than from the Illyrian west. There Mithraism, imported by Roman legionaries from the Orient, had succeeded easily and naturally the indigenous, primitive sun and moon cults and it continued to make progress until checked by Christianity’s official triumph in the fourth century. It would, however, be unwise to dismiss too lightly the possible influence of the native Illyro-Macedonian cults upon the local development of Christianity. Although Christianity’s victory over Mithraism also appeared complete, the persistence of sun symbols, not merely in the remoter parts of Albania, but prominently displayed in, for instance, the brickwork of the Kastoria churches of Aghios Stephanos (ninth century) and Anagyriou (tenth century)

66

![]()

Fig. 38. SUN SYMBOLS IN BRICKWORK ON THE CHURCH OF AGHIOS STEPHANOS, KASTORIA, WESTERN MACEDONIA

Fig. 39. SUN SYMBOLS IN BRICKWORK ON THE CHURCH OF THE ANARGYRIOU, KASTORIA, WESTERN MACEDONIA

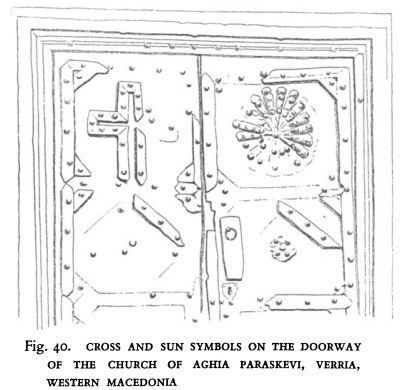

and, together with the cross, on the mediaeval wooden door of the Verria church of Aghia Paraskevi, indicate that the indigenous beliefs did not succumb so easily or quickly (Figs. 38-40).

However, probably an important result of St Paul’s influence on the early evolution of Christianity, the fundamental (though not exclusively) Thracian religious themes, Bendis the chthonic Great Mother Goddess and the Heroic Hunter, were not resurrected in Christian ideology and iconography for several centuries. Compromise played no part in this dynamic and fanatical apostle-martyr’s character, and his example and writings enforced a similar discipline upon Christianity. His reactions to the forces ranged against him in Philippi and other parts of Macedonia, the first impressions probably confirmed during his subsequent journeys, may have played no unimportant part in forming his fateful antipathies. They would have certainly been strengthened by the fact that, although a Roman citizen and the apostle of the Gentiles, he always retained in his heart the strict principles of an orthodox Jew, to whom the idea of a female goddess or a feminine influence in religion was foreign and sacrilegious.

Fig. 40. CROSS AND SUN SYMBOLS ON THE DOORWAY OF THE CHURCH OF AGHIA PARASKEVI, VERRIA, WESTERN MACEDONIA

During the second century a.d., Rome’s increasing activity on her eastern frontiers brought mounting prosperity for Macedonia. The theatres of Philippi and Stobi, both modelled on lines popular in Asia Minor rather than earlier European forms, date from this century. Stobi’s metamorphosis from a garrison town into a well-planned, prosperous, provincial Roman city probably occurred at this time. To an even greater degree the staging-points and cities of the Via Egnatia must have enjoyed a liveliness and wealth

67

![]()

that had never been theirs before — and which before long was to prove an all too great temptation and all too easy prey for invaders. Except for an occasional re-used slab, capital or pillar, and a few buildings excavated, nothing remains of this highway’s ancient prosperity — its destruction was so complete and the ensuing Dark Ages so long lasting. In many cases, Verria being an outstanding example, new cities have risen over the graves of the old and rendered archaeological excavation all the more difficult. In others, however, as financial grants slowly become available, the past is being gradually uncovered, revealing the mode of living of those who once earned rich profits from the commerce of the Via Egnatia.

In the second century and for much of the third the Macedonian economy was steadily expanding. Not until the second half of the third century did there appear even the slightest hint of the approaching disaster. There are no records of the progress of Christianity in the province at this time. Perhaps the conditions of prosperity were not particularly propitious. On the other hand, such tendencies as the increasing materialism and the custom of deifying the emperors may well have produced a concealed but strong reaction that would have favoured Christianity’s growth.

Whichever was the case, it was not until the fourth century that the Church in Macedonia emerged from its obscurity. In 325 the Council of Nicaea provides us with the first authentic record of the existence of a bishop of Thessalonica. The incumbent, Alexander, who was present at Nicaea, also attended the Council of Tyre in 335 where he was a staunch supporter of Athanasius, bishop of Alexandria, in his struggle against the Court-favoured views of Arius.

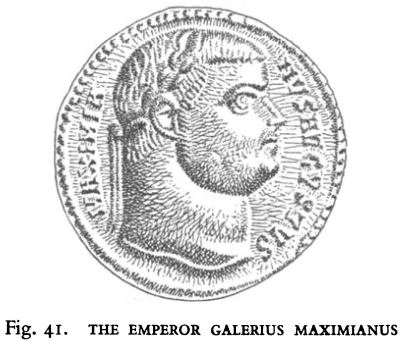

Fig. 41. THE EMPEROR GALERIUS MAXIMIANUS

Alexander attended, in the same year, the dedication of the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem. It was Alexander, too, who, we are told in a mediaeval account written by a monk named Ignatius, had earlier taken the courageous step of baptising the daughter of Galerius during the latter’s absence fighting the Sarmatian invaders. This incident is of interest not only in its presentation of a legend concerning the construction of one of Thessalonica’s churches (a legend not, in fact, supported by archaeological evidence) but in its story of Macedonian Christianity in the years immediately preceding the Peace of the Church. Ignatius tells us :

‘ It was during the years of the persecution. Impiety, having the Emperor as an ally against Christ, was flourishing and progressing, while piety was almost eliminated. Maximian (Galerius), the Christian-persecuting Emperor, was that notorious and faithful servant of the demons. He lived with his wife and children in the famous city of Thessalonica. At that time he was busy preparing war against the Stavromatai (Sarmatians). He had an only daughter, who became the fertile earth to receive the seed of divine instruction. She was called Theodora....’ Walking one day along the seashore beyond the city limits Theodora came to the quarter ‘where the persecuted Christians dwelt, because there the tyrants had sentenced them to live .... The young princess, with her whole retinue . . . arrived at the altar where the High Priest Alexander was carrying out his bloodless sacrifice. She stopped before the church and after listening outside for some time to the divine hymns, was carried away, and said to her retinue, “I wish to see and hear how the Christians praise their God and what are their chantings”.

‘She entered the temple with such discretion that the faithful there admired the shyness and the attention of the maid. When the time came for the reading from the Bible (it was the passage from the Final Judgement of the Lord in which He Himself will judge His creations and give each according to his works) and she heard the divine word, she received, like the noble earth, the seed deep within her heart so that it soon began to strike root in her soul. Already the divine fire was kindled within her, the fire which Christ came to bring on earth. She called one of her trusted servants and told him in secrecy, “Without anyone knowing, try to bring the bishop to me this evening”.’

68

![]()

That night, leaving her parents under some false pretext, Theodora met Alexander. He interpreted the Bible to her and gave her instruction in ‘the divine economy and the mystery of the divine human nature of Christ’. After he had explained the rite of baptism, Theodora exclaimed, “‘Here is the water, what prevents me from being baptised ?” The bishop, holding her head, christened her in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, in a big jar that was there for the collection of rain water.’ Because living with her parents prevented her from carrying out her Christian devotions, Theodora pretended illness and asked her father to build for her a house with a bath in the northern part of the city, near to some quarries, in order that she might forget her bodily sufferings. The house was quickly finished and there Theodora found greater opportunity to follow the instructions of her spiritual father.

Before leaving for his campaign the emperor visited his daughter to inspect her new dwelling and the bath which was still under construction. ‘But something made him wonder and he confided his thought to his daughter ; namely, how could water be found for the bath since the area was so arid and rocky. The quickwitted princess, however, replied, “He who has made all this will undertake to bring water even from very tar away .