Prillep, Krali Marko's Birthplace

One understands three things from those words. First of all, Marko's fortress, the huge ruins over the basalt, two-humped ridge, which in the beginning of the Pelagonia plain ends the mountain range with Babouna; secondly, the old Prillep, stuck in the rocks, under the ruins, now called Markovgrad [*] or Markov Varosh; and finally, present Prillep, a town with 20,000 inhabitants, founded by the Turks at a half hours walk away, down in the valley (Turks have never liked climbing hills unnecessarily).

I was nearing it - stirred, mentally and physically.

Physically, owing to the narrow-gauge line Bitolja Gradsko, built in six months' time during the World War, so solidly, that even though it was still temporary, it had served well enough, without any basic repairs, and at the same time, so poorly, that the train whirled like a trinket and shook like a toy. "Are you going to travel with that Samovar?" I asked before I left Bitolja. "Why, it can topple over any time!" One shouldn't be afraid, because in such cases, with its slow velocity, it will just pour out its passengers carefully, if they don't jump out by themselves. But at least, the phournitsa (a small stove) created a happy mood, reminding us of Marko and his childhood, at the time that he had united the charm of a good-hearted child with such a strength, that God had had to take away half of it, "so that he wouldn't do anything to the world". The locomotive, looking quite new, attracted all sorts of animals at each station (at one, I counted 8 pigs, 5 ducks, a lamb, and 4 chickens). The bravest of them entered, or rather dashed, into the car, lead by the knowledge, acquired from experience, that after the feasts of the passengers, they could always find plentiful scraps. Just as Marko, who had easily pulled the huge stone, after sucking from the miraculous breasts of the wood-nymph, the little machine moved off with such a jolt, after being filled up with water, that everything inside lurched. The chickens fell off the car, like ripe, early pears, while the other frightened animals scattered in

*. Marko's town.

![]()

46

all directions, and we, like beans in the palm of a naughty boy, jumped around the car. We were subjected, not for the last time, to the humorous mood, towards which Marko had had a weakness, and which had found a good reception in his native parts.

Mentally, because of some fears. I wasn't afraid that I might meet the famous hero, since I didn't believe in the legends that he was still alive, but even if I did, I hoped it would happen when I could show him the songs of him, which I had colleted, or when I could ask him to pose, so that I could draw his picture (one could imagine how he would sham, since we know how he had looked from the songs, when he had stood face to face with the incomprehensible human stupidity. "Mrke brke nisko obesio" — his black moustache is drooping, of his black moustache is falling on his shoulders.

I was afraid of something else: wouldn't Prillep disappoint me? Fate Sometimes delivers disappointments together with pleasure. The Balkans have always been treacherous, as Saturn, who ate his own children. Only a few of the ancient towns had remained. Each people that had arrived here, including the Slavs, had readily destroyed whatever they had laid hands on, and what had been left, had been finished off by the medieval and contemporary crusaders. The flood of history, which worked here, was still going on like a ceaseless steam-roller. All the traces of the Turkish domination were constantly being destroyed everywhere, even the beautiful things that had been created, with a blind prejudice.

But we still had a long way to go, when my doubts started to vanish.

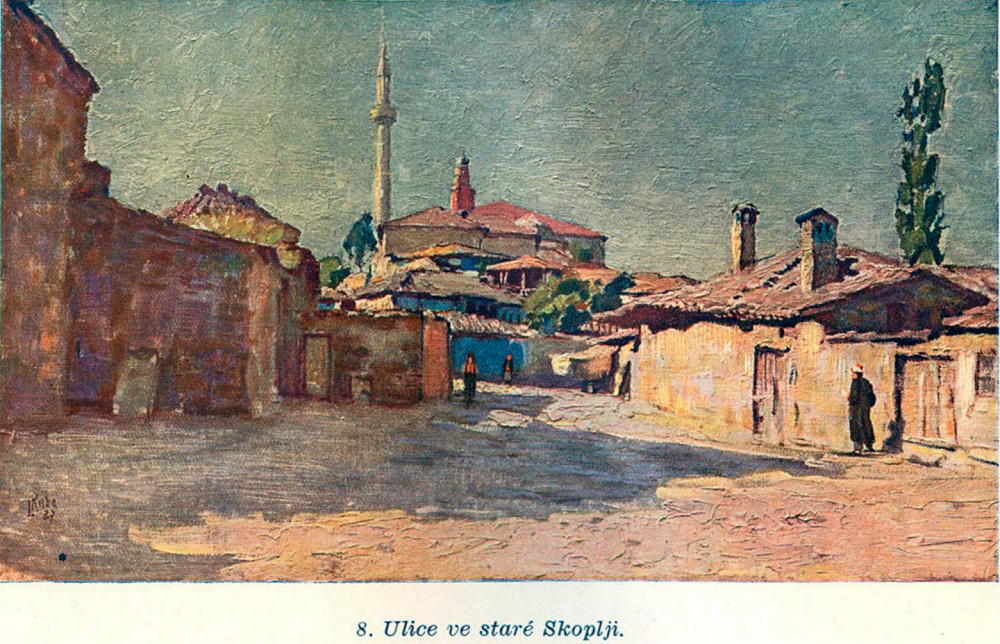

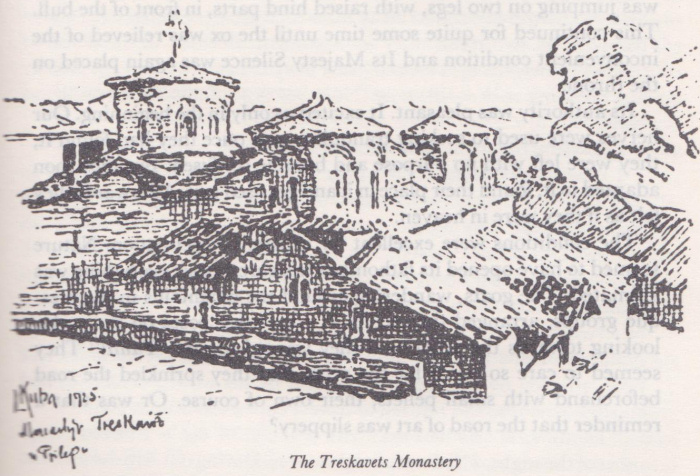

The Pelagonia valley, a compact, green corn area, between the magnificent limestone ridges in the distance, was barred by basalt rocks, which like an indented steel rasp, were stuck in the grey azure of the sky. The irregular ruins of the teeth resembled lined up soldiers. A white point gleamed on the height — the Treskavets monastery. Later, from the village, the features of the castle could be discerned. In the lowlands, enclosed by a huge amphitheater, the railroad coiled and twisted towards Gradsko, and on the green carpet below, we saw the smiling face of the town, a garden, which was a magnificent contrast to the gigantic rocky surroundings. A few broken down minarets, with clock and church towers, were sticking out of the dark-green surface of the dense trees, among which the familiar, charming, Greek-type houses, with their eaves hanging low, lay half hidden (they had numerous large windows, spacious verandahs, and wide, shady eaves).

--------

![]()

47

The whole town was like a park and that's how the Turks had wanted it. We looked over the enormous frying pan, open to the southwest. The place resembled the mountainous Italian towns, with its broken up rocks and dense shadows in the scorching sun. We foolishly asked, about some large rocks, believing them to be castles, which we couldn't find on the map.

There was only one castle, above the town, as a last bastion for the wild mountain range, spreading its gilded peaks, decorated with all sorts of bizzare heads (renamed into granny, frog, etc.), to the north. That was Krali Marko's castle.

We relaxed contentedly, Yes, the great hero, whose name and deeds filled the minds and the hearts of all South Slavs, could have been born here, the soil was as he had wanted it (he had refused to plough in a soft soil). As it is said in the song, he had helped his father (King Vulkashin) to clear the forests, and while the father had gone home at noon, to fetch a pitcher of water, the son had cut all the trees. We agreed that the castle, with its sharp, pointed rocks, whose enormous walls resembled fairy-tale dragons, was quite appropriate for the wood-nymphs that had followed Marko, mounted on stags, which they had lashed with poisonous snakes.

The image of the insidious King Vulkashin, who according to tradition had killed the entrusted him son of Doushan, Ourosh, merged from the bluish shadows. The glorious Bulgarian Tsar Samouil appeared. In 1014, his great life had ended here, when after losing the battle, he had seen the 15,000 blinded soldiers returning home and his heart went to pieces. And what was the history of this place? No one could tell for sure. Yet, it seems, that it became important from the moment, when the wretched mankind had invented weapons, as a cursed proof for the fact that our souls lack the necessary goodwill, and our speech the necessary clarity, so that we may live on good terms in this wide world.

A brisk gypsy boy picked up our bags. We followed obediently, while the garden town seemed to be showing its reverse, and not its facade. Its charms, hidden behind the garden walls, it offered only to its own, local people, while the streets were covered with a thick layer of dust, in which we were half-hidden. The innkeeper consoled us, poor fellows (and himself, along with us). "Wait till you've seen Skopje!". But he soon understood that here also, we, the prodigal worshippers would be remembered by nothing.

![]()

48

A very small area in the town center, whose lawn, white as straw, urged upon us the thought "why is it exactly under the sun that one tans?", was encircled with thick barbed wire, which could be seen everywhere—rolling about in the fields and mountains, together with shrapnels and other leftovers from the World War. The small padlocked gate barred us from seeing, whether it was a trench, kept as a memory of the military hurricane. But the huge board, nailed on high poles, notified us that it was the Wilson Park. Some flowers, which couldn't be found below, were drawn around the sign. We now understood what the padlock was for: to defend against the sunstroke, which the simple-minded foreigner might receive in the "Park".

It was not for the locals. They had more than enough natural pleasures at home, as we noticed whenever we looked in impertinently and greedily through the half open gates. The yards were fabulous gardens. Roses, basil, petunias, gloxinias, oleander, sunflowers, babiaks (sheeps' tails), mallows, sword lilies, creeping beans, clematis — all these were crossed and interwoven in the most charming fashion with grape-vines and tree branches, creating an enchanting garden, which merged with the houses through their balconies, alcoves, arbours, and most of all through their porches — rooms without outside walls, where one lived, slept, worked, feasted, and at the same time received and entertained guests. Everywhere one could see exquisitely arranged groups of people, covered by lights and scorched shadows, while the wonderful thickened ends of their distaffs, glowing like torches, were most impressive. It was like an instant kaleidoscope.

Why was it so fresh there, while in the American thinker's "park" it was a real Sahara?

Prilep

![]()

49

The "park" was a product of modern times, while the other of old, Turkish times, when the cult towards water had been everyone's credo. Everywhere around the buildings, thanks to the brisk Prilepets and Dubnishte streams, which joined in Prilep and divided it into three parts, abundant brooks flowed in paved ditches, deviating into each house.

There was enough water in the marketplace, as well. That was why the local "charshiya" was so charming, the cleanest in the Balkans. Everything shone. The multi-coloured products of nature glowed as if they were made of coloured glass. The red and carmine peppers and tomatoes looked as if the gypsy shoeblacks had shined them with the same virtuosity and care and with the help of the same polishes, waxes, pastes, deerskins and cloths, with which they gave an unbelievable lustre to our shoes.

When one adds the small shops with the copper cauldrons, braziers and brass querns, the silverware merchants, the embroidering tailors, the shoemakers, the saddlers, all arranged in lines according to their professions, so that (as we believed) the impression would not be spoiled, one could understand the joy with which the kids ran to and fro, the pride which each shopkeeper pointed towards his shop, and the pleasure, gleaming in the eyes of the inquisitive peasant, who walked around with his family and his horse, and with his costume enriched the picture of swarming Turks, Albanians, Rumanians and gypsies. All was an endless carnival and the shouts and the roars were its spell-binding fanfares.

We were amazed by that astonishing town. We couldn't stop wondering. A Serbian sign, placed upside down on a kiosk, which read: "Available Douvana No: 10", showed the unexpected (unusual in our country) readers' interest. It was not necessary to push up the little window in the post office, since one could easily get his stamps through the broken glass, without cutting oneself. In the district government's offices, my attention, as a gatherer of folk songs, was quite insistently called to the glorious Vuk Karadjich's collection, written "in our beautiful, state language" and published a hundred years ago. Later in the evening, in the Turkish bath, we faded in the twilight of the marble cell, resembling a Byzantine temple with its columns and arches. We poured water over our sweating bodies and absorbed the rich impressions of the interesting day, and at the same time expected the new one.

![]()

50

Sat Marko in a golden castle.

Its gates

were really exquisite,

decorated well, and very white.

The eaves of pure lead,

the windows shone lime mirrors,

shone afar, my son!

All gates were strong, of iron,

with gold ducats they were covered . . . . .

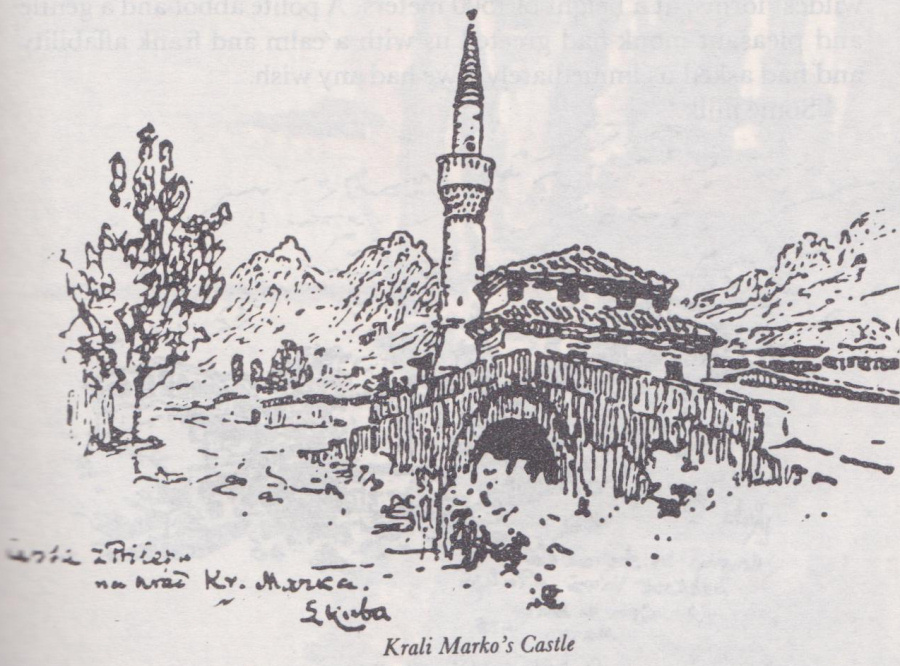

The ruins of this Balkan castle, the largest and with the thickest walls, were merely the coarse edge of the bluish-grey basalt ridge. They still overwhelmed and petrified one with their proportions, but did not fascinate him with their magnificence, now preserved only in the Bulgarian folk song. By 1670, when the Turkish historian Evlia Chelebi had visited these places, the castle had already been nonexistent. Only in the barn there had been grain in abundance, mainly millet (traces of it were still visible) and in the three preserved buildings a watchman had guarded the villagers' implements.

Inside the castle walls there were: the building that could be seen from far away, called The Loom, the destroyed church of King Vulkashin with mural paintings of angels, part of a chapel on whose walls the knights had scrawled illegible inscriptions, parts of columns and capitals. Everything had been so enormous that the decayed castle had a large free space in the middle, called charshiya (marketplace) even now. Everything had been gigantic, as Krali Marko, of whose so far recorded songs a whole library could be compiled.

We weren't surprised by the vast ocean of legends and myths, whose creators had always lacked strong enough exaggerations and words of praise. One could not be surprised by their imagination in that turbulent sea of rocks and stones that rolled together with the steep ledge towards the northern slope and stopped just before the place, where once the glorious city of Prillep had stood. Now it was an ordinary village, called Marcovgrad or Markovvarosh. One could only wonder that for the person of whom the song had such vast knowledge, history had almost none. We, who were standing in the heroic surroundings, felt the contradiction most keenly. The spot that

![]()

51

we stood on was a natural ruler's capital with its location, height and appearance. One could sweep with a glance and watch, even in the dark, the wide Pelagonia plain, and the majestic, surrounding, mountain ranges. Armed force had probably been present here from prehistoric times. We could not but assume that the ruins were not a record of the mythological hero, but that he, i.e. his imaginary figure, was a record of the place, which for a long time had been not only a natural military defensive point or springboard of aggression, but had also been endowed by nature with beauty and rich decorations, so that it could torment human imagination. We were ready to believe everything that we heard in the folk songs, which had always kindled their listeners' imagination, often giving them an impulse to create new ones. The vagueness of the historically obscure Krali Marco had facilitated the birth and the evolution of the legend.

The village, the one time Prillep, wasn't just can appendage to the mountains, but a city of which, as of Ohrid, it was said that it had had as many churches as were the days (i.e. the saints) of the year. We tripped over their abundant remains. Nine rare buildings, even though they were half destroyed, were a museum of art, presenting the transition from the Greek-Bulgarian architecture, from the time of the Assens (or before them), to the Serbian-Macedonian period. The archless basilicas passed into arched ones, trying to reach the cruciform Byzantine plan. The thin Greek bricks, which had taken a lot of the builders' time, had created different, as if woven, decorations and had joined the stone elements. Stones, cut in smooth lines, alternated with double rows of bricks, while the wide lines of the marble lime were not only an incomparable weld, but also an element, which decorated the St. Nichola church, whose wonderful facade was probably the oldest, St. Peter enchanted with its wonderful brick apse. The monumental, semi-demolished St. Anastasius, built of stone and brick, undoubtedly belonged to the Serbian period. St. Dimitar could be singled out with its preserved condition and slightly ascending dome.

The local Serbian teacher took us everywhere. We finished our tour in a shady shop, where we eagerly quenched our thirst with soda water. The lively man had traveled a lot. He had been to America and he introduced us to his neighbour, who had also returned from there not long ago. He earned his money abroad, like many of the local men, returning from time to time with some savings, in order to

![]()

52

use them for the good of his family and to repair his house. The neighbour greeted us affably, since in America he had met some Czechs and had liked them very much. He told us of the happiness he had felt abroad, when he had come to know them more intimately.

This provided an occasion to talk of the Czech people, since the teacher also loved it. He was interested in Slavdom in general. He had arrived at a certain view for our common future, "You, Czechs, are most educated among the Slavs, while we are most belligerent. If we unite, we can lead all Slavdom."

We thanked him for the compliment, but pointed out that the first delicate point of his theory was the unilateral answer that he had given to the question, what the priorities of his own people were. Then I added that he should distinguish between the state and the people, as differing concepts. The army was a state body and it could be of use to the people only if the cause had any cultural significance. Even though many present events were disappointing, mankind, on its own, was moving the center of gravity of its struggle in the cultural field. The Czech people was unanimous in one thing. Militarism was not its goal, but just a means of self-preservation. Even though it had been educated in an anti-militaristic spirit in Austria, it had shown during the World War what it was capable of on the battlefield. I even marred the teacher's happiness by saying, "Even though the military operations of the Serbian army during the World War received world-wide recognition, I cannot but place our actions higher. You have always had a military spirit, and an army for a whole century, while a military spirit we have never had, and our army had to be raised hurriedly in different parts of the world. Nevertheless, it performed wonders in Siberia, in France, and in Italy, as well". I also added that if we were going to speak of all Slavdom, we could not neglect its largest representative, the Russian people. "It is the largest mystery on the globe today, an enormous question mark, and the whole world is watching it intently . . ."

A bit surprised and shocked, the teacher sighed, "Of course, Russia!? But only at home. It doesn't even want to hear of us, abroad, immersed in chaos and need".

As if trying to excuse himself, he added, "How many of them we have here! We don't know what's going to happen to them. You'll meet one today, an abbot in the monastery, stout, frowning, gloomy, a grumbler. It's difficult to talk to him!"

![]()

53

We went towards the monastery, the only item that remained on our list.

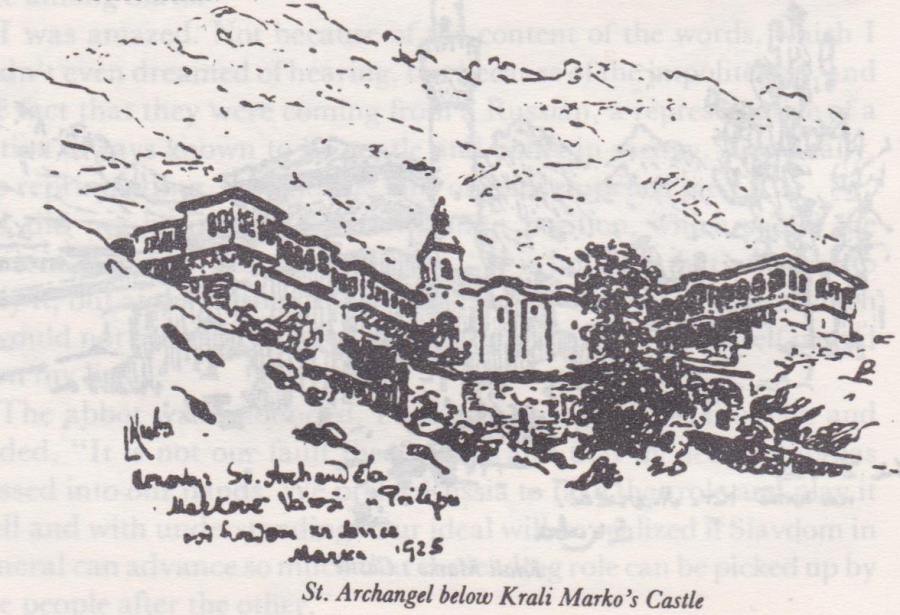

It was the St. Archangel monastery, founded, according to tradition, by Krali Marko. It attracted me chiefly by the paintings of King Vulkashin and his son Marko.

We walked along the buildings, adorned with golden garlands of dried tobacco leaves. Bare rocks towered above the town and allowed us only an occasional glimpse of the castle walls. But a few minutes later, the rocky confusion passed into a smooth wall, on which, like an eagle with outspread wings, the monastery gleamed; a white temple, resembling a birds carcass, stood in the middle, while the wings with cells and balconies on both sides, were like the wings of a bird.

I didn't know what the basis of the legend, was, that the hero of the South Slavs had founded the monastery. But if the building with its appearance didn't represent its patron, the winged St. Archangel, then it must have been an involuntary expression of the flight of the essence of Marko's poetic image. The impression could not be diminished even by the images in my mind of Ostrog in Montenegro, St. Petka in Ohrid, St. Illiya in Skoplje, and other southern monasteries, which also resembled aeries hanging from the rocky walls. This one, though, resembled an eagle about to fly off.

An outing from Priliep to Krali Marko's Castle

![]()

54

Two painted figures stopped us at the entrance of the temple. They were damaged (how couldn't they be, when for half a millennium they had been exposed to sun and rain) and redrawn, but most amazingly, the picture and its separate parts were preserved. The figure on the right was of a young man with a king's mantle and a large cross in his right hand, and a scepter in his left. The deacon's stole revealed that he was the patron of the church, while the short sign read: the pious King Marko. The figure on the left was of an old man with a majestic garb. The sign was illegible, but it was rightly believed to be that of Marko's father King Vulkashin.

Marko had come here to fast, to repent for his sins, to confess, and to take his Eucharist. Whenever he had prepared for his prayers, he had ordered his wife, "Prepare my church garb and my liturgical books!"

The voice of the abbot, who was singing his prayer, echoed from inside.

The singing stopped abruptly and the clergyman came out. He had a tall figure and a gloomy appearance.

The teacher introduced us, myself and my son, adding, "From Prague".

"So you are Czechs?" uttered the cleric unexpectedly, in a cold voice. At the same time, as if he had just come to his senses, he added reproachfully, "Yes, Czechs! You Czechs now want to play a leading role among Slavs!"

I was amazed. Not because of the content of the words, which I hadn't even dreamed of hearing, but because of the impoliteness, and the fact that they were coming from a Russian, a representative of a nation always known to be gentle and polite in society. And finally, the reprimanding, even hostile tone of voice stupefied me.

I did not hesitate to take an instant position, which suited the present moment. I answered firmly, "It is not true that we want to play it, but at the moment we are playing it!" It was a sentence which I would not have dared utter if the bitter man had not himself placed it on my lips.

The abbot was astounded. I took advantage of the situation and added, "It is not our fault that it is so and that the leadership has passed into our hands. We prefer Russia to take that role and play it well and with understanding. Our ideal will be realized if Slavdom in general can advance so much that the leading role can be picked up by one people after the other."

![]()

55

The abbot softened. He showed us around the church, whose interior, owing to the frequent restorations, was damaged, and once again proved the well known truth that the cares of enthusiasts often inflicted greater damages to cultural monuments than the enemies' raids or the influence of time, often slandered unjustly.

We started back towards present Prillep, founded by the Turks in the lowlands, "a cannon's shot away", as Evlia Chelebi had written.

Those were unforgettable days!

I woke up in a wide, spacious room, in which the first rays of the morning sun entered from two sides (directly from the east, and after being reflected by the orange coloured mountains, from the west), while my astonished ear heard an unusual melody. The golden tones were drifting in the air. what was it? A music clock?

I was still drowsy and couldn't collect myself. Truly, I was the victim of that vice, since each day we wandered from one place to another. The unknown world around was like a merry-go-round and

Krali Marko's Castle

![]()

56

in the morning it was difficult to tell right away where chance had allowed us a brief refuge. But here the doubts were greater. The incredible silence, mysterious and penetrating, increased them. And in its abyss, the sounds echoed even louder and I couldn't guess whether they were coming from metal strings or from bells. The alluring impression sooner lulled than cleared the senses.

Nothing was left to me, except to recount yesterday's events.

We had left the village of Dabnitsa, situated in a deep rocky valley, early in the morning. We had spent the night at the mayor's house, whose grey walls had been decorated with green fig-trees and chestnut trees. He had given us a dinner which had begun with a ritual — the washing of our hands. In the morning each of us had mounted one of the beasts that Christ had preferred to ride. The excellent animals had more intelligence than we had courage; it was enough to set them onto the path and they would start walking bravely along the rocky mountain slope towards our destination. The riding had otherwise been wonderful. Nature had frivolously squandered picturesque confusions of rocks, opening wide views towards the foggy ravines and the magnificent mountain slopes. Two hours later, very thirsty, we had arrived at the monastery; perched among basalt giants having the wildest forms, at a height of 1500 meters. A polite abbot and a gentle and pleasant monk had greeted us with a calm and frank affability and had asked us immediately if we had any wish.

Some milk.

St. Archangel below Krali Marko's Castle

-------

![]()

57

"We have none but we will provide it," they had answered.

And they milked a sheep. Then they gave us bread and we ate and drank. When they left us to take care of their duties we did not remain alone. A turtledove flew over to our table and started pecking with us. A lamb rubbed against us and licked our hands with its soft lips. The cook, a Don cossack with a giant's body and a kind-hearted appearance sat opposite us, leaned his elbows with rolled up sleeves on the table and with the palm of his hand propped against his wide jaw and happily watched us eat greedily, not knowing how authentically he resembled Repin's hot-tempered cossacks, prompting their answer to the Turkish Sultan, to the clerk.

These memories were accompanied by music. I already knew where I was, but I still didn't know what the ringing of the Lorettan bells meant. Where were they coming from?

Out of curiosity I went over to the bay window, which was more than a meter deep. I could see the Shar mountain, which was slowly dropping its bluish night garment and was putting on the orange brocade of its morning garb.

I looked down and I saw a carnival. A procession of cows was walking with dignity, as if during a religious service. The bells on their necks were swinging as if they were in the hands of ministrants. Could they comprehend that they were turning the everyday moment into a holiday?

I wanted to be on the porch where a wash basin was ready, but I stopped on the threshold, before a new glorification of the resurrected day. The eaves with Turkish tiles on the old church with four towers, immersed in the shade of the round yard, glittered like silver and gold fish scales and flirted with the colours of sea shells and pearls, and the colours of the rainbow. It was triumphant, optical symphony of the elements!

Everywhere there was silence and its likeness, since the dark spot — a monk — walked silently towards the church for his morning prayers and merged with the shade of the deserted yard. The blackness of his kamelaukion and monk's cassock did not come from a lack of dyes, as silence was not a lack of sound. I washed and dried myself in the blazing sunlight. Then I started my tour in the unknown surroundings.

It was as if I was in a bastion. The group of monastery buildings seemed to be a bastion of the Church, rather than a cloister for human

![]()

58

beings. Only the wooden balconies, encircling the yard as a cart basket, softened the impression.

The numerous doors of the guest rooms were silently closed. There were no guests, with the exception of two monks. It wasn't the anniversary of the monastery's patron day, when the place filled with people and was like a boiling cauldron. A fascinating hubbub would reign then and the monastery would need a whole year's rest to return to its everyday routine. That was why it was so violently silent. The hushed singing of the monks, which was coming from the cells as from a dungeon and was becoming excited, seemed only to make the silence more expressive.

I toured the century-old walls of the church, of which it was known that King Miliutin had renewed it at the beginning of the fourteenth century. The plaque, which had been built in the northern wall, read: In the month of January died God's servant Dabizhiv, Enochiar (manager of the roads) of Tsar Ourosh (Miliutin) of all Serbian, Greek, and Maritime lands. 6870 (1362).

What had been before that was not known. It was certain only, that the church and the whole monastery were much older. During Miliutin's time the churches had been built with a nave and two aisles. Here there were actually two basilicas, whose relationship was mysterious, since one was smaller and should have been, according to practice, older. But it was of a later period. The window of the older church was cut from a single stone, showing an Armenian influence found before Miliutin's time and maybe even before Slavic time. Some common characteristics with Bulgarian churches, as for example those in Stanimaka and Bachkovo, indicated the time of the Bulgarian Tsars, the Assen, whose authority had covered the region. The narthexes, originally designated for the "repenting" and chiefly for newly christened pagans, had already been included in the original plan. The mural paintings were from different ages. In the small church they were from the sixteenth century and in the catacombs (in the southwestern corner) from the fourteenth century. The mural paintings in the central dome were new. The shepherd filled in the scant data by telling me that the monastery had been empty and deserted for seventy years "because the Turks slayed the djatsi and the vladalye (the monks and the high-ranking)". The bloodshed had been awful. An animal had been created from the blood and no one had dared come near because of it. But once lightning had struck the

![]()

59

animal and had killed it. Nevertheless, no one had dared come for a long time, until one day a shepherd settled here and had became a monk.

Roman architraves with pieces of cornices and marble busts, and well known Roman sepulchral figures with broken off arms stuck out from the unplastered walls. The speculations that they were remains of Greek or Roman pagan deities did not seem odd to us, the uneducated. The place was so fantastically situated that it was equally appropriate for the religious sages and for the prudent servants of the pagan temples. Human nature worships the mysterious and strong effects, and under their pressure it is more susceptible to all religious flames.

Of course, the remains of classic buildings and statues were not a rarity in the Balkans and may be found not only on the walls but also buried in the ground. The Prague professor L.N. Okunyev recounted that he had found a graveyard in Macedonia, in which a peasant had used a Roman statue for a tombstone. He had only changed the name, because the existing one had not pleased him, but had been content with the resemblance.

The Treskavets Monastery

![]()

60

Everything was mysterious and unexplored. Some openings with plaster remains could be seen in the high, inaccessible walls. Maybe they had been death chambers for the condemned or for the willing hermits, or were remains of fortifications, since the monasteries had also been fortresses. Some inquisitive people had found out that human bones were withering away inside.

A few seats had been cut out into the rocks in front of the monastery. We sat in them after supper, with our hosts, and continued our great silence, which was an all powerful ruler here. Dusk was closing in on the mountains, but they took a long time to immerse fully in it.

We spoke almost in whispers, of King Miliutin's chainmail, which had been shown to us in the catacombs, or of King Doushan, whose royal decree was one of the rare records of the monastery's past.

Otherwise, the law of silence could be interrupted only accidentally, as when an irritated bull stuck his horns into the thigh of an innocent ox. Immediately, of course, a great din (human and animal) set in throughout the whole monastery. The ox groaned as if it was dying. While the cowherds yelled for help and ran to and fro with lanterns. The monks hurried to the barn, where the miserable animal was jumping on two legs, with raised hind parts, in front of the bull. This continued for quite some time until the ox was relieved of the inconvenient condition and Its Majesty Silence was again placed on the throne.

Its authority was pleasant. It excited us only in the beginning. Our nerves were used to seeking tranquility and once they had found it, they were left with no purpose and became confused. But they soon adapted to it, found their place in it and got used to it. Afterwards they felt as if they were in heaven.

The conditions were excellent for artistic preoccupation. Nature seemed to have opened its fathomless treasure-house; everything was animated. The goats, wandering around the mountains in picturesque groups, arranged themselves in coquettish poses on the rocks, looking towards the artist as if they wanted to say: "Paint!" They seemed to care so much for the artist that they sprinkled the road beforehand with small pellets, their own of course. Or was that a reminder that the road of art was slippery?

![]()

61

All this had quite a different meaning for the young Serbian artist, who had arrived almost at the same time as myself, and had brought twelve canvases on a donkey. When the mountain winds knocked down his model and shattered his easel on the rocks, he hurriedly left us and the monastery, leaving everything behind.