I. IN OHRID AND ITS VICINITIES

Tale One 7

In Ohrid 10

Lake Ohrid 18

Lake Prespa 40

It is unbelievable: of all Slavic lands, Macedonia and Czechoslovakia, which joined hands for a great cultural cause, at the very dawn of our histories today are completely alienated. Our relations date as far back as the year 863, thanks to the Equal-to-the-Apostles Saints Cyril and Methodius, and their disciples Clement and Nahum.

These ties are now being renewed, not till a thousand years later, thanks again to the Macedonians. But instead of the Slavic Lithurgy, now they employ different means, which are more consistent with our times. First, they tried to glue together the damaged cause, using Turkish honey and "rakhat lokoum" (a relaxing Turkish delight and a sticky eastern sweet), then they used sheep's guts, which were sold partly to the sausage makers, for the production of sausages, and partly to the string producing factories, which pleased the harebrained idealists too. All the time, the Ohrid lake offers us therwise tempting necklaces, made of artificial pearls, which might sooner stand for Czech-Macedonian cooperation, since for their production our town of Iablonets supplies glass scales, as silvery and opal as the scales of the small fish (Alburnus belvica), and Ohrid is already full of them. But I feel that in this way, the cause will not be led off in a false and artificial direction, despite the fact, that we have sufficient quantities of artificial pearls.

In 1925, the Czech-Macedonian relations embarked on the third, essentially new period, and our sympathies turned into actions. First of all, Dr. J. Komarek arrived there, to study his namesakes [*], which together with tropical malaria caused many evils, and secondly,

*. Czeck Komarek means mosquito.

![]()

8

I myself arrived, to collect folk songs. Even though we felt on our own skins that the above-mentioned scientist was studying quite a burning issue, I believed that my task was more important, since it was also more urgent. Domestic and American capital was taking the utmost care of the mosquitoes, in the numerous, and sometimes magnificent tropical institutes and malaria stations, but I doubted that anyone had shown any interest in the songs until then. And, after all, they have been the only practical result of all scientific research. We were under the impression that we could catch malaria only from those mosquitoes, whose hind parts were raised when they stung. And who could possess enough calm and enough bad taste for such observations as these?

Therefore, there was nothing personal in the fact that I attached greater importance to my project, the more so as some events which occurred upon my arrival allowed me to do so. I was famous. At least along the Nish-Salonika railroad, almost at all stations, where the express train stopped at, I was cordially welcomed by gypsy brass bands, drums, and castanets. My fellow travelers assured me that the attention was meant for them too, and that this habit had been firmly rooted here ever since the World War I, but I stole it all for myself. I produced a notebook and took notes. As far as the melodies were not a foreign echo, it was worth it, especially the rhythm.

At that time I was on my way to Ohrid. I only stopped for three days in Skoplje, so that we (I and my son) could get used to the heat. We kept crawling in the thin shadows along the walls: we, the local people, the soldiers, the cattle and the dogs.

But our compatriots kept urging us on. "It might get even hotter," they said. "It ought to be hot here! It is situated very low, and in a hollow at that. Just hurry on to Ohrid. The altitude there is 700 meters and there is a large lake. It's pleasant. Even the ancient Romans...."—"and the young Roman ladies," I intervened—"went there for their holidays. On some days the temperature here goes right up to 60°C."

My eyes popped out (in Macedonian, the only thing you do with your eyes is: goggle), and asked fearfully: "I guess, you mean, 30 in the morning, and 30 in the afternoon?"

"No, at a time"

We sped along by car, for ten hours on end. It is difficult to use the word "straight", though. The road, with its many curves, wound like a lashing whip around mountains and valleys. The numerous stones

![]()

9

and holes threw us up into the air, and instead of sitting down again, we crashed down into the seats which despite all their softness seemed to be made of stone. At the curves, between Gostivar and Mavrovo Polle, we passed through the clouds of the same dust that we had raised below. When we finally saw the glittering Lake Ohrid, embraced warmly by the blazing mountain ranges, spiritually, we were cheerful admirers of their grandeur, but physically, we were dead beat. In the evening, it was easy to understand the joke, which was meant for us, from the next table: "Our roads are excellent, for aeroplanes."

The joke gave us the courage to ask, what those big fires were, that twinkle like stars in the Albanian mountains?

"The Albanian shepherds are cooking their supper."

It was difficult to go to sleep that night. On the one hand, while dozing off the car would keep racing violently, again and again, swerving over and along the steep edge of the precipice over the Radika river, and with a shudder each time, I would shake the nightmare and the uneasiness off, and on the other hand, my small room faced south and was like a crematorium, which made me start a mental argument Skoplje friends: "So it's cooler here, isn't it?"

In desperation, I lit the gas lamp, took out a list of addresses, and while crossing them out one by one, began writing postcards, sending my warmest greetings to friends of mine (those were the only greetings I could send).

Dead tired, I fell asleep late, with a lot of unanswered questions such as: how was I going to complete my work in this heat? What about the drawings and the songs? Could one do anything else here, except sweat?

But on the next day, when I was climbing up a steep street, under a vine arch and the bluish azure, which had found a place to show off, and was ploughing across the lake, visible through the houses, with their jutting out upper storeys, all my passions were quickly forgotten, and my spirits became radiant like the local sunshine especially so when presently I heard a song coming from somewhere. My first Macedonian song! I drew nearer stealthily, so that I wouldn't start the singer, and listened carefully to the notes, almost subconsciously, and in a short while I identified the melody and the words:

Oh, my mountain, you're so high,

my dear, you're so far . . .

![]()

10

I was amazed: that was one of our own songs! A song of which famous Czech scholars have been writing about for years, and still do, as of one exceptionally and purely Czech.

At that moment however, the fact that the song was neither only Macedonian, nor only Czech, did not disturb me at all, (since as early as 1834, it had been published in Moscow, in Maksimovich's collection of Ukrainian folk songs, in 1863, in four versions, in Roguer's Polish collection, afterwards, it was sung in Rumania, and may be elsewhere). At the moment, I accepted it as a special attention from this Slavic land, neglected by me for so long. I was not sorry that my notebook had remained unused. I would find another time to make up for it.

It was easy to get up early. The cock, which at daybreak announced in its esperanto the approaching sunrise right under my window, had enough strength only to unglue my eyelids, while shortly, the snow-white mosque, next to my window started glowing and the air quivered with the drawled singing of the muezzin, and through the open window I could clearly hear how he frequently drew breaths, in order to sing each sentence at one go and draw it out as long as possible.

I could not restrain myself. I went near the window and watched the priest; not that it was something new to me, but it had always been a pleasant delight. I experienced the efforts of the crier. The instant was marred only by my regret, that not being a Turk, I could not do it instead of him. I knew of no better human greeting to the playful day. True, our bell-ringing, as long as anyone does it anymore, also possesses grandeur, but what a performance it is, pulling the bell rope like a pig's tail or shaking it like a foot during a soccer game! The skillful Russian ringing, where the sexton stands on all fours, as if swimming in the air, and leads a whole "flock" of different sized bells, above him, below him, and around him, is still acceptable. So what can bring greater delight, than walk up the slender minaret and stand up in the peaceful calm of the night air, eager and happy to greet the waking world and the endless unknown?

The muezzin fell silent and I started dressing. In the meantime, his singing was substituted with similar melodies by the boys that carry

![]()

11

around the fresh bread: "Yes, buns, yes, warm buns, yes, yes ..." Added to this counterpoint of quarter notes was the faraway braying of a donkey and the piercing barking of a dog, the result being an uneven three-voiced singing that was no match for the magnificence of the glorious moment, but was a nice transition from the religious mood, which breathes each morning, to the daytime clamour, the din of everyday life, consisting of perpetual petty squabbles or more whopping scrimmages.

I saw no one when I went out. The "charshiya" (market place) was deserted. Only the coffee shops were beginning to open. An old "effendi (or gent)," whose asthma, most probably, did not allow him to sleep, was already sitting in one of them drawing on a long chibouk, with a cigarette stuck on one end, and occasionally sipping black coffee. A pig was rooting about in the deep holes of the rutty street, looking for goodies. It paid attention to nothing and no one, as I will, when I begin reading the proofs of this tale. A chicken, with carefree ease, without any fear of donkeys, mules, and people, and with scientific concentration and knowledge, was studying everything that could be subjected to analysis, which was in abundance, especially in the early morning. A few dogs, with the purposeless shyness of the unemployed, were wandering from corner to corner, as if looking for some "place". They lived in want, the poor souls. None of them had a master, and all they could do was to enjoy the happiness of freedom, which none of them thought of at all happy. Tempted by a boy's voice, a veiled Turkish woman, hiding her face with her yellow coloured fingers, opened the uncomfortable gates and had difficulty in choosing a loaf for her children, who were stretching their hands towards her. Otherwise, nothing much happened. Only the first rays, as arrows through a shield, spreading over Petrin, spyingly penetrated through the narrow streets, where, with a divine, unprejudiced equity, they clothed everything they penetrated in a golden fleece, including those things, which man, owing to the narrow-mindedness of his miserable attitude, calls disorder. And he would overgild and make an enchanting poem out of it, because the principle of reality is unknown to nature, and nothing makes any difference to it.

I succumbed, as a child yearning for everything, and did not know what to begin with.

We arrived last night at sunset and I already felt, that I did not know where to start from. Everything was beautiful! I could have gone to

![]()

12

the nearby beach and contemplated the lake, which under the veil of the early morning mist still dozed in its bed among the mountains. In the town, I could have walked among the antique houses, that looked so youthful in their southern style, perched one over the other. I could also have climbed up, above them, to the ancient, scarlet, brick temple of Saint Cyril, from which a marvelous view of the whole lake opened up, and from where I could see the pear shaped Ohrid peninsula stemming from the lake. The uneven cobblestones threatened to make me reject the thought, but I hoped that among the tall houses, crowned with vines, I might be able to find gaps, through which the malachite lake glistened. It would be a pretence for a rest, since the climbing was quite inconvenient. I also felt like running towards the western end of the town, protruding from the rocky island, on which the poetic church of Saint Ivan Bogoslov stood out, like an old and wrinkled falcon and where I could carefully listen to the great, divine silence, which reigned over the surface, and I could look down into the precipice, towards the famous lake Ohrid springs, where people always went for water or their washing, as the folk song "Beliana was bleaching a sheet at the Ohrid springs" said.

I was also tempted by the dew — sprinkled valley, connecting the- town with the foothills of Petrin to the east, and forming real garden, full of branchy trees and lush vegetation, so rare in late summer, that just the sight of it in the heat was like a refreshing drink — at least for the eye.

Whither then? The sun advised me: hurry upwards, the earlier the better!

I decided to follow its advice. I stumbled in the narrow streets, where light-footed peasant women were hurrying with their burdens to the market, and at the same time, without stopping, were knitting socks. I found myself on the northeastern side of a two-humped peninsula, densely forested on its southern side, and barren, bald, and dry on the northern one. Its beauty was not marred, though. I looked to the north and to the east. The lake was edged on all sided by fields, still partly shaded by the mountains. I took the road by which we had arrived from the smiling town of Strouga, which was gleaming out white in the distance, below the Albanian mountains. That was the northern-most point of the lake.

I remembered all the details of yesterday's trip. A magnificent feeling recurred in me: when after a whole day's trip we turned into

------

![]()

13

the Strouga valley and glimpsed at the enormous lake! Cherni Drin, the wide mouth of lake Ohrid, was calmly flowing against us amidst the fresh alfalfa and the reed swamps. It was enjoined to flow into the gorge, which we had just left, but it had shyly reflected for a moment, wound, and divided into arms. Its "mouth" (that was what it was called there), by which it separated from the lake, was in Strouga. A wooden bridge, which once, while it had still been decorated with shops, could have been compared to Venetian and Florentine bridges, served as its Arch of Triumph into the town.

A street in Ohrid

![]()

14

On the other hand, the rows of antique shaped barks still stood at salute; they stuck out of the water as antediluvian hippopotami. They did not look very lively. Their sides were widened with beams, so that the fishermen could run to and fro when they cast or pulled up their nets. They raised their front parts inquisitively, like wooden rafts, reminding one of the local water-buffaloes, which raised their muffles, while bathing, in exactly the same manner, so that they would not swallow any water.

Our car shaking all over scared away the aquatic and wading birds into the dense screen of the lake: the careful storks and the elegant and diverse herons. We caught a glimpse of some albatrosses and pelicans as well. The rare animals reminded us of Herodotus's history, according to which even lions had once lived in the Balkan peninsula. We could only make a mistake with a play upon words, by saying: jelvi which we saw at every step. They were not very shrewd when they crawled out of the corn and sometimes allowed themselves to get run over and killed. Until not long ago, the tropical animals had been represented by the camels. For thousands of years they had been the main means of transportation along the Via Ignatia road, leading from Ohrid to Constantinople, but the new age deprived them of their means of subsistence.

The old times still manifested themselves in very diverse ways, though. In the fields and the gardens, for example, one could see from a far the large mill wheels. On the top, a man leaning on a wooden door drudged tirelessly (properly speaking: very tiredly). He went around in circles, drawing lake water for the dry fields. At the same time, one could see excavators working in the lake. They were digging the silted-up lake, so that the marshes could be drained and rid of the mosquitoes (or the malaria). Reluctantly we calculated in our minds, how fast would those wretched people have to go around, and how much more would they have to sweat, when the excavators had finished their work.

I climbed up towards the one-time castle and I met an old lady. The older women were dressed in dark, even black clothes. There was a preference for that colour generally, in Southern Europe. A silk scarf, whose ends were crossed at the back and wrapped the head in such a way, that they may be tied in a small knot above the forehead and drop along the back. I greeted and asked if I was following the right road towards Saint Clement.

![]()

15

"Yes, of course."

I thanked, and was about to continue, looking to my right and left, when the woman asked: "Bendisash Ohrid?"

I didn't know what "bendisash" meant, but I knew the word "benegisvan," which comes from Turkish and means: to like. So I had no difficulty in answering. My only thought was, should I shake my head or should I nod it, when I pronounced the word yes? In the Balkans it is done in the oriental manner-in exactly the opposite way. Nothing serious could have happened here, as it did to one of my compatriots in Serbia while traveling on an express train. Not knowing the difference, he had remained in his seat until the last stop, because the conductor had always shook his head, and another time he had got off, when the conductor had nodded his head. Still, it would have sounded comical saying, in the local meaning, different things with

Ohrid Architecture

![]()

16

my lips and my head. I managed my performance delicately. The old granny smiled happily. The people from the South, more than anywhere else, listen with pleasure to someone who is praising their native land. Immediately, she started a quick dialogue, which seemed to me a lecture in the local dialect, and I welcomed it. It was a pity that the neighbours soon took away the woman who was passing by me. "Sadi se zdravlye" (good health), I parted with a greeting, learned quickly yesterday. "Aerliya ti saat!" (happy times) answered the granny.

I neared the platforms stealthily, that connected the two parts of the peninsula, which in the past, at times of war had been converted into an island. Undoubtedly, the foundations of the medieval fortifications were much older, because the ancient fortress Lychnidos had been situated here, as far back as the third century B.C. For a hundred years it had belonged to the Romans. Christianity was introduced in the third century A.D. by the legendary martyr Erasmus, the first Bishop of Ohrid, whose success forced the Emperor Maximillian to kill 20,000 of his followers.

After that, the fortress had been revived by the Slaves. The great Bulgarian Tsar Simeon had his second capital in Ohrid, and a hundred years later, Tsar Samuoil (who believed himself to be a successor of Alexander the Great) raised Ohrid to the highest pedestal of glory. He had conquered almost the whole Balkan peninsula and had established a Bulgarian Patriarchate with 30 Metropolitans here. The wars, which he had constantly waged, had not prevented him from taking care of education, in all its spheres. He had tried to drain the drenched and malarious region, he had built roads and bridges, and had taken measures towards a flourishing economy.

Those were Ohrid's most glorious days. After that, neither the Bulgarian Tsar Assen II, nor the following (for a hundred years) Serbian domination could bring them back. Ohrid had declined, and it was a decline in the national sense, as well. Greek culture had increased all the time and had acquired greater power, which it had managed to preserve during Turkish times.

I walked around a Turkish tulba (grave), looking like a stone alcove, overarched over four pillars. It was desolate. A wandering swine was rooting in the dense weeds that were now taking care of the forgotten grave, as if with malice towards the deceased, for whom it had been an "unholy" (sinful) animal. For 504 years the crescent had

![]()

17

ruled here, and now this contemptible creature should dare do such things! The deceased did not resist. He couldn't. But such is the meaning of the Koran: submit to the new authority. One epoch devours another. Time is its own enemy, as man is of man, and the new generation of the old one.

The proof was everywhere. A square-shaped ruin, whose walls had overgrown with wonderful ivy, was standing in front of us. Its scratched face, at least the unveiled part, was begging for sympathy. But we ignored it. Not because it was the ruin of a mosque, which before that had been a temple of Saint Pantheleimon. Saint Clement himself had founded the temple, and in accordance with his will, he had been buried there. When the Turks arrived, in 1408, the Christians had to move the Saint and make place for Allah. They had first moved the relics in a temporary grave, but later they were laid to rest on the hill above, with the Virgin Mary, who had received the holy relics, but had lost her name. The church has been called Saint Clement since then.

At this point, the town descended down the steep slope, towards the shores of the lake. The millennial basilica Saint Sofia could be seen below, founded no one knows when, towards which men had always behaved as real masters, as they had behaved divinely towards the thousands of tenants, without ever evicting them. When the Turks arrived, the Christian God had to step aside, only to return half a millenium later. Gods are not supposed to loathe living one after the other. Mankind demands greater patience from them, than it demands from itself. And with full light, since it allots them more wisdom.

I walked past the palace, which had been destroyed, like everything else around. I saw the seat of the local bishop (boyar), the place from where until 1872 the Greeks had led the fiercest of battles against the Slaves. The danger no longer exists, thanks to the Bulgarian patriots, and especially to the Miladinov brothers, who helped win the battle in the sixties of the past century.

Following Greek fashions had vanished, because it never was significant, except on the surface. In the marketplace, one could still see a small shop which resembled an office. The sign suggested that it was used by a lawyer with the Greek family name of Demosthenes. I remembered that yesterday in Strouga we found another such sign - insignificant in size, but with a great name on it - Aristotle. Hail, if

![]()

18

you are descendents from your famous namesakes! You must be busy enough carrying the burdens of your names! It should be comparatively easy for the first one, if he has decided to surpass his glorious namesake in his early period, when he was rather clumsy and couldn't make a decent speech.

A description? How on earth could one describe a mirror? It was only an image of the opposite side, wasn't it, and this one was just the light blue nothing of the vault of heaven. Therefore, we shall speak only of the frame of the mirror. In the distance it was blue—violet, while nearer brownish—yellow or grey—green, richly modeled by the famous masters of which we learn from geology. Time, unworthy of praise itself, had taken care of the finer decorations, since it could engulf anything, except itself. Here, it had managed to carve out a blend of exquisite lines, and, one must confess, with a worthy of recognition national and political impartiality (the western coast is Albanian, while the eastern one Slavic).

The natural amphitheater, stretching for 20 kilometers, is majestic. The azure surface smells of the sea and resembles a gulf. One's eyes wander along it without any obstacle. Why, if it was just an image of space? Our thoughts penetrate through it and disappear. They escape reality and wander in the past. They escape local boundaries and flow off towards all Slavdom. They flow to our native land, to the motherland in the north, from where they dream coming back here.

There was nothing odd. Two men, who once, as disciples of the Apostles Cyril and Methodius, had worked laboriously in our land for 15 years and had had the intention of becoming our compatriots forever, and could not have done so only because of Svatoplouk, rested here. Afterwards, for a quarter of a century, they had worked in this enchanted retreat and had developed the seed of Cyril and Methodius's language with such zeal, that they had laid the foundations of the Slavic — even the Pan-Slavic-alphabet.

The grave of one of them, the Temple of Saint Clement, rising above Ohrid, offered us a shade to rest in; the grave of the other, the Saint Nahum monastery, could be glimpsed at for a moment, immediately vanishing in the next, as a white spot on the opposite (southern) side of the lake.

![]()

19

We pressed close to the wrinkled walls of the old building, whose ancient tiles shone with all the colours of baked clay and variegated licnen. It was like a tangle, with its octagonal vault and interlaced bricks, and its appearance was moving, like an affable old lady. With its past, it was an age-old chronicle, which Byzantine architecture had supplied with a rare binding.

We remembered the fateful summer of the year 885, when Saint Methodius died in our country. After his death, his disciples had either been jailed or banished from the country. Three of them: Clement, Nahum, and Ahghelarii had started via the Danube and Belgrade for Bulgaria, towards its capital Preslav, where the newly converted Tsar Boris had happily accepted them, and a couple of years later, without Ahghelarii, who had died in the meantime, had sent them to the westernmost boundaries of his country, to Ohrid.

They had remained in the apostolic mission, which the Eastern Church respected as Sveti Sedmochislenitsi [*] (since, plus Cyril and Methodius, it added Sava and Gorazd), as first after the founders. Clement had been fated to perfect the written Slavic language, created by Cyril, and to strengthen and spread it around to such an extent that it would sound forever in the churches of Southern and Eastern Slavs (even in Rumania the Old Slavonic language had been dominant in the church and the state until the 16th century, and in literature until the 19th).

Had Clement anticipated the greatness of his cause?

Did Slavdom respect him properly?

In our country, in the Emausi (Na Slovaneh) [**] monastery, Church Slavonic already existed during Charles' IV reign, and in the land of Lugiicka, in the beginning of our century, Dr. Aronost Mouka found an Old Slavonic manuscript in the Germanized community Goswar, in Lower Lugiick, dated from the 16th century. Therefore, with the exception of the Poles, Cyril and Methodius' language was an All Slavic language.

Such was Clement's cause. And if Salonika had been the birthplace the first literary Slavic language, Ohrid had become its cradle. If Cyril had been the one that had planted the seed, Clement had cultivated it. He had had 3 500 pupils in Ohrid, who had copied and spread the holy books among the whole Slavic world.

*. Sveti Sedmochislenitsi — The Holy Seven. Transl. note.

**. Na Slovaneh — At the Slavs'. Transl. note.

![]()

20

The credit for substituting the difficult, original alphabet, the Glagolitsa (which is still preserved in the western, Catholic parts of the Southern Slavs, the Croats), with a more convenient one, later called Cyrillic, was ascribed to him. But further research showed that it had occurred in the eastern part of Bulgaria, in the court of Tsar Simeon.

Five branches had stemmed from the trunk: five modified provinces: Czech, Slovac, Serbian, and Russian, plus the original Bulgarian. History is still full of mysteries and unanswered questions. Some of the scholars maintain the view, that Church—Slavonic does not belong to any of the present Slavic nations, while Kopitar and Miklos claim that it is the language of the extinct Panonian (Hungarian) Slavs. They arrived at that conclusion, because of the closeness to the Sloven language, on the one hand, and on the other hand, because by chance, the holy brothers at Prince Kotsel's court on lake Balaton, had won over Clement, when stopped there during his journey to Rome. But the overwhelming majority of scholars believe that it was the language, which had been spoken in Cyril and Methodius's birthplace, Salonika, therefore the language of the Macedonian Slavs (Sloveni, who later on, together with the rest of their co-tribesmen, had adopted, according to their country, the name Bulgarian. That is why, the Old Slavic language is also called Old Bulgarian.

These mysteries are a constant subject for the research of scholars — linguists and historians, but they arouse the curiosity of non-specialists as well. The Polish Slav scholar A. Bruckner believes that one of the greatest and wisest acts of Svatoplouk, has been the rescuing of his country from the Eastern Church in favour of the Western, but he is probably too far carried away by his Catholicism; it is obvious that the Catholic Church, with its results among the Polish people, cannot be placed higher than the Orthodox priests. The friendly attitude of the Orthodox priests (clergymen) and believers has always had a benefecial influence on the souls of the people, in a democratic sense, with which the Balkans have always had a superiority over the rest of Europe, and which is one of its advantages and attractions. Even though Bruckner's view is controversial, one thing is certain: Cyril and Methodius' books had come earlier to us than they had to the Bulgarians; and if Clement could have remained in our country and worked without any obstacles for the same cause, as

![]()

21

in Ohrid, it meant that he would have worked in the center, and not in the periphery of the Slavic world, for the Slavs at that time had lived far as Hamburg and the Rhine. And it is also quite clear, that the Panonian Slavs, bordering the Slovins, would hardly have vanished forever, and that the Elbe Slavs would hardly have been assimilated so quickly, so that the continuous German territory can today reach a point. which is only five hours by foot from Prague. Our language would have acquired a different sounding — most probably it would have been the real Czechoslovak language, and undoubtedly, the Polish language would have been influenced, and the language division would have been smaller.

Such thoughts were haunting me, while my eyes wandered over the lake's surface.

Clement had been of an exceptional spirit. With his assistant Nahum, he had taken care not only of the schools and churches, but also of the mundane aspects of life: agriculture, fruit growing, the economic development of the country. The memory of him is so vivid among the people, that they think of him as the First-After-God. Even now, the local people are sworn in his name.

In the region of Ohrid, which had already been populated with Slavs for 200 years, the proper Slavic period, which had reached its zenith a hundred years later, under Tsar Samouil, had begun with Clement. The patriarchy, established by Samouil, had been entrusted to the born in Debarsko St. Ivan Bigorski, serving in the famous monastery of the same name, north of the Drina river, on a a woody, steep mountain slope. Ohrid's glory as a tsar's capital had not continued for long. In 1018, the Greek Emperor Basil II — Bulgarslayer, had destroyed Samouil's state, liquidated the patriarchy, and allowed only the priviledge of independence to the Ohrid church. Since then, Ohrid has not had Church—Slav leaders (until 1872, when the Bulgarians had acquired an Exarchate).

But Slavic literary tradition had been maintained. The famous Ohrid Gospel is an important record of Slavic linguistics. The Bologne Psalter was written during 1230-1241, and the Psalter of Branko Mladenvich in 1346 (during the reign of Doushan). As far as the 16th century, the famous local Archbishop Prochor, a Greek, had allowed the copying of Slavic manuscripts. The Greek language here had played a role similar to that of the Latin language in our church, and no other meaning can be ascribed to Doushan's

![]()

22

words, when he had called the local church "Greek". The accelerated Hellenization had started only in 1777, but it had been unsuccessful. The area, with minor exceptions, was Slavic, as was half of the town with its 15 000 inhabitants. The other half were Albanians, converted to Mohammedanism, a few Rumanians (Tsintsars), and least of all Greeks, who only provided the town with lustre, owing to their schools. Two young men, the Miladinov brothers from nearby Strouga, had managed to erase it quite quickly, when they had won over the craftsmen and the richer families, followers of Greek fashions. One could read an interesting sign in the church of our saint. Among the rich decorations, which filled the inside of the church from the floor to the dome, under the portrait of Ostoi Raiakovich, it was written that he had been a relative of Krali Marko.

A treasury, with rare antiques, may be found in the church. One is fascinated by the dimmed with old age shades of the frescoes, the golden iconostasis, the fantastic outlines of Archbishop Prochor's throne, especially if the Archbishop, in his majestic, violet uniform, is sitting on it. The frescoes, the icons, St. Clements coffin, the valuable embroideries, and the wooden statue of the saint — all create a pleasant atmosphere. The library, containing over 120 old, printed editions and manuscripts, is a permanent subject of research work for many scholars. Two of them are well known in our country. Both of them are Russians: the scholar and politician P.N. Miliukov, who had sometimes visited us as an émigré after the war, and the Byzantologist N.P. Kondakov, who had fallen in love with Czechoslovakia as a young man, during his first visit, and after the Russian revolution had sought here and found refuge and a career, and again three years later—his grave too, in our country.

Today, only modest traces are left of Ohrid's glorious past, which had belonged to the whole Slavdom; And no wonder. A thousand years have passed since the Christmas tree of Slavdom, lighted by Clement, had glowed here. When he died in 916 (six years after the death of his associate Nahum), the glorious light was already on the wane. Today, what is left is but a crematorium. A pile of ashes after the fireworks, that had cast its light far and wide.

I left Clement's grave and fixed my eyes on Nahum's in the distance, not noticing the beauty of the lake.

![]()

23

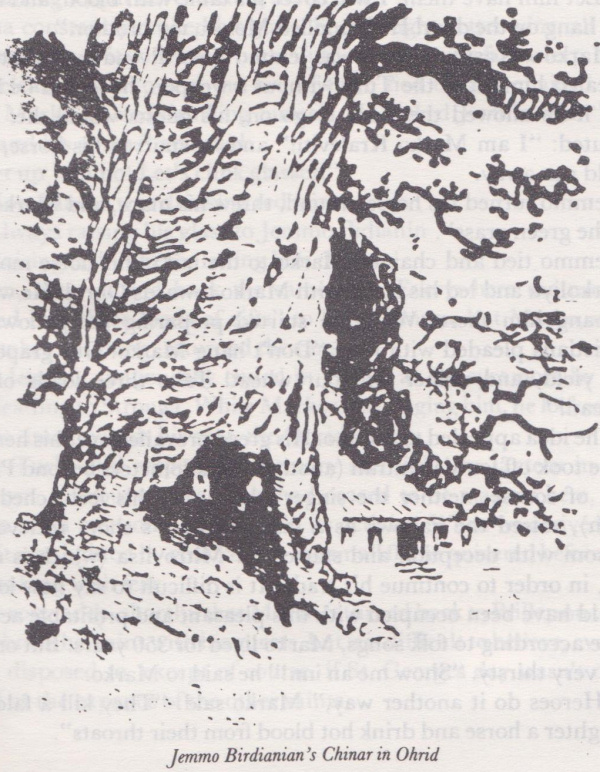

Jemmo Birdianin's "Chinar" (or Plane-tree)

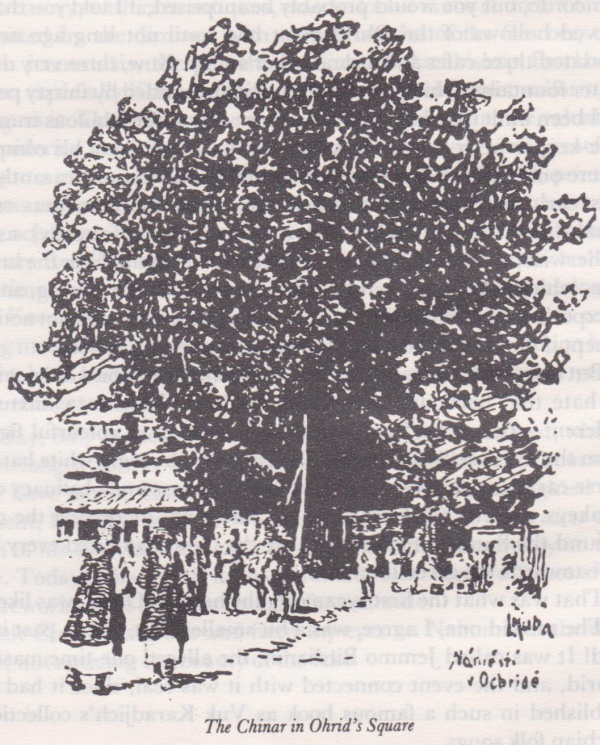

'Chinar' is a Turkish word and means sycamore (or plane—tree).

There were two of them in Ohrid. That is, there may have been more, but these two were-so big, that even Trieste's and Dubrovnik's famous sycamores, prescribed to the obedient tourists in Baedeker, could not rival them.

The larger one covered a whole square with its shadow. Those of you who are familiar with the South may exclaim: "We know what a square down there is like, like Piazza Grande in Corchulya, for example, which is no bigger than an anniversary postage stamp. I agree that Ohrid's square can hardly be compared to Place de la Concorde, but you would probably be surprised, if I told you that the carved hollows of the Ohrid giant had until not long ago accommodated three cafes and a shoemaker's shop. Now, three very decent water fountains, which were constantly surrounded by thirsty people, had been built in, while on the northern side of the fabulous trunk the cafe-keeper from across the street had a subsidiary of his company, where one could sit down and drink black coffee quite pleasantly, if it was early morning or late afternoon, when the numerous crows, inhabiting the hospitable crown, were still (or already) asleep. Otherwise, something very wet could start dripping from the branchy tree, which served as a public umbrella when it was raining, and the inexperienced foreigner could not avoid it, or might even not notice it, except if the bird decided on its own to sweeten his coffee.

But even such an inappropriate joke from the evil bird did not make us hate that harbour, open for all kinds of elements, a mixture of different patterns and costumes, a chaos of most colourful figures, from the lively seller to the tall dervish, with the high, white hat. The horse caravans, and especially the stubbornness and obstinacy of the donkeys, sweetly (at least for those watching) increasing the chaos around the Sunday market, because the thirst had lured every creature towards the green fountain.

That was what the first sycamore, the heart of Ohrid, was like.

The second one, I agree, was a bit smaller. But what a past it had! It was called Jemmo Birdianin, the alleged one-time master of Ohrid, and the event connected with it was real, since it had been published in such a famous book as Vuk Karadjich's collection of Serbian folk songs.

![]()

24

That sycamore was also carved out, but an old lantern was suspended (aslant, as if hanged) inside, and its light twinkled shyly.

It twinkled because of Jemmo Birdianin, who had been hanged on the tree by Krali Marko's own hands. The song, which told of this, had originated in Herzegovina, and presented us with basic data of Ohrid: that its lake boasted a lot of fish, and that the fish boasted with its taste, famous even in faraway lands.

The action started in the castle of Prillep, 120 kilometers to the east (we shouldn't be frightened by such distances; as we shall see, they mean nothing to Marko and his horse Sharkoliya).

It was St. George's day, and Marko was celebrating "krusno imme", the patron saint's day of his home. Such guests as befitted him had gathered:

The Chinar in Ohrid's Square

![]()

25

Two hundred priests and three hundred monks,

also twelve Serbian voivods (chieftains)

and other guests uncounted.

There was "a lot to drink and different guests", and only one shortcoming, which was soon noticed by a greedy monk with the words:

There is no fish from Ohrid.

This angered Marko. He ordered that his guests be given enough food and drink, while he went to prepare Sharkoluya and himself for the trip.

Mother Yevrosima, when she saw how he was girding himself, said anxiously: "Don't take any weapons with you! You are too used to blood. You may desecrate your patron's day".

Jemmo Birdianian's Chinar in Ohrid

![]()

26

It was difficult for Marko to start off without any weapon, but it was even more difficult not to obey his own mother. He started off barehanded.

He was nearing the river, when a horseman stepped on the opposite side of bridge. He crossed his legs and started toying with a heavy mace. He threw it up, above his head, and caught it "in his white hand".

They greeted each other. The foreigner asked: "Unknown hero! Aren't you from Prillep? Aren't you from the suite of Marko Kraleviti? Is Marko home? Does he have many guests?"

Krali Marko answered: "Unknown hero! Early this morning I was in the Prillep castle! Marko is doing honour to his saint, and glorious guests he has, uncounted!"

"Let him have them. I will cover his table with blood, and him, I will hang on the door! He has killed Mousa, my brother."

Marko was astounded. It was Jemmo himself! And now what? If he revealed himself to the Turk without a weapon, he would be killed, and if he allowed the Turk to go on, his guests would die. So he shouted: "I am Marko Kraleviti!" and he spurred his horse, so he could run away.

Jemmo turned his horse around, threw his mace, and Marko "fell on the green grass".

Jemmo tied and chained Marko to the tail of his horse mounted Sharkoliya and led his horse with Marko towards Ohrid. He wanted to hang him there. When he started preparing the gallows, the Christians pleaded with him: "Don't hang Marko! Our grapes will not yield, and neither will our wheat! Take three loads of gifts instead!"

The idea appealed to Jemmo. His greed prevailed over his heroism, so he took off for Valchitran (another 200 kilometers beyond Prillep, but, of course, neither the singer's head, nor his feet ached from them), raised the gallows as a fair merchant's shop, received the ransom with deception and started for Mitrovitsa (which is not so far), in order to continue his trade. It is difficult to say how long he would have been occupied with this pleasant and profitable activity, since according to folk songs, Marko lived for 350 years. But once he was very thirsty. "Show me an inn!" he said to Marko.

"Heroes do it another way," Marko said. "They kill a falcon or slaughter a horse and drink hot blood from their throats".

![]()

27

Poor Marko! His advice was ill-fated. The Turk drew his sword and shouted: "I shall cut your throat and drink from it, instead!"

Marko could use nothing but cunning. "I know an innkeeper, the cursed Yana," he said. "But she will revenge me. I have never paid when I have drunk at her inn."

Jemmo hurried towards her inn. She was standing at the door and Marko winked at her. She understood. She shouted happily to Jemmo: "Welcome you hero of the heroes! Oh, I thank God in heaven, that you have captured Marko. I will wine you for nothing, for three days and three nights". And she was already fulfilling her promise.

Thirstily drank his wine, Jemmo the Turk, Always raising his glass to Marko Kraleviti. Raising it, but never letting him drink.

Yana constantly refilled his glass. She brought better wine, all the time, and mixed it with some herb, until the Turk was fast asleep. She then released Marko and the two of them tied up and chained the Turk. Marko started drinking himself. He kicked Jemmo with "his shoes and his spurs," and said:

"Get up Jemmo! Let's clink glasses!"

Now Marko was drinking red wine,

Always raising his glass to Jemmo Bidianin

Raising it, but never letting him drink.

Then, they started back the same way. Everywhere the people "offered him three loads of gifts" to hang Jemmo, but Marko, who never takes anything, returned the ransom.

For Jemmo, the journey ended in Ohrid, at the sycamore by the road, leading to Strouga. While Marko was hanging him, he looked for the last time towards his seat, the Ohrid Castle.

The Turks still respect his memory and light the lantern in the sycamore. Of course, after they had ceased to be masters here, the lantern often met some obstacles in its activity. When we arrived, at dusk, it was lighted by chance, but the small flame quivered before us, as if shaking with fear.

The song adds, shortly, that Marko returned back to Prillep on time to celebrate his saint with his guests, but it is difficult to believe, even if one is disposed to, except of course, if St. Georges day wasn't continued at the expense of the other saints.

![]()

28

He also brought fish which he caught himself. He was luckier than we were. We also looked for it immediately, like that gluttonous monk. We even ordered it every day to the waiter, but in vain. The answer was always the same: "There is no fish.

If they weren't afraid of Marko, the way they weren't afraid of us, he also wouldn't have received any fish, because then, as today, it was sent further on immediately after being caught, even though there was no state monopoly on the fish, as there is now, when it may only be bought secretly from poachers.

Luckily, we found compensation (although not full). We bought a picture book with pretty and clear lithographic picture of all 17 kinds of local fish. We admired them with such interest, during lunch and dinner, that we could name all 17 of them, and in Latin at that. We knew, of course (from the text), the taste of each fish. I remember none of them now. The monk's verse, still rings in my head whose first half our waiter always managed to repeat with admirable consistency: There is no fish from Ohrid

It was a fire of the old type, of a decent calibre, without insured foundations, and without the participation of uniformed firemen. Things here burn in their natural, undistorted way, without the excessive piling up of artificial obstacles, that resist not only the raging flames, but according to the fantastic law of philosophy, of the ruling until not long ago crescent — the will of the almighty Allah — and therefore are a sinful creation.

A man like me could only stand abashed. I didn't understand. I came and saw how the youth of all local tribes and religions played soccer. Occasionally, with brisk movements, the young Turks aired their "shalwars" (Turkish trousers) in the shadow of the melancholy mosque, which watched the parabolic movement of the ball disparagingly, with the calmness of a sage, but gave immediate advice: "What would happen if instead of sports we set up a fire brigade!" It was right. Everything seemed to be built for a fire on purpose, only of boukhta [*] and wood!

But it didn't know that its undoubtedly sensible counsel was at the same time useless. A fire brigade, as a group for mutual assistance

*. boukhta — a type of Czech building material. Translator's note.

------

![]()

29

among neighbors and fellow-tenants, was impossible. Only a hired fire brigade could have existed.

The reason wasn't in any moral failure of the local people. It was in their composition, where social differences were not manifested as clearly, as tribal, national, and ethnographical ones. The numerous elements, living together for centuries and millennia, thanks to the differences in language, dress, customs, and religion, had remained permanently alien to each other, the more so that no political idea or state independence had ever united them. They did not lack feelings of humanness or unity, but a gulf of all sorts of prejudices had been created between them throughout the centuries and it hindered the cultivation of social relations. In addition to the Slavic majority, living predominantly in the villages, Albanians (former Illyrians), Tsintsars or pseudo-Rumanians, Greeks, Turks, Spanish Jews, and Gypsies had lived here for a long time. They all showed their different social status and different external attitudes, with identical internal pride. In a general sense, with the exception of the old guilds, they couldn't depend on a united life. And in no way was any reform or any modernization of anti-fire technique (as far as the setting, burning or the extinguishing of the fire was concerned) possible.

We witnessed, by God's will, such a respectable fire in the town of Strouga. On the outside, there was nothing special about it, for those, who remember the fire-fighting tradition at home, before insurance times: the mix-up (from the mothers), the shouting, the wringing of hands by the (sometimes prematurely) desperate women, the unpractical passing of water in unsuitable vessels, done with feverish speed by some and with icy indifference by others, the squabbles as to who should sprinkle with the hose, and so on. The houses, just as it used to be at home, quickly, by themselves, emptied out their colourful insides in all directions. I even saw a phenomenon which once, in Koutha Hora, had made us, students laugh, without considering the tragedy of the moment. Our teacher, who had been a little exalted, had rushed into the first floor of burning building and had tried to save everything that had come handy inside by throwing it out. This included some plates. And he had had such a presence of mind that he had first looked downwards, to make sure that they would fall on the ground and not on someone's head. The fire in Strouga was put out in the same way.

![]()

30

So everything occurred as at home, with a little local burns. The moving out here, for example, was easier, since the household belongings consisted mostly of clothes, carpets, rugs, and pillows. Thin women, who were invisible under their burdens, dragged them in huge bundles. The heavy, long chests, in which the things were kept, remained inside, since there was no one to carry them out, because the local men went abroad in large numbers to earn money. So when I and my son helped a few women to carry out their bundles, we were turned back into the burning house, with tears and pleas, and had to carry down, from the first floor, a two meters long chest, with which it was difficult to make a turn on the collapsing staircase.

The main spectacle was at the nearby marketplace, where the small shops spewed out enormous quantities of goods that had no end. Everything that could be saved, was carried to the bridge and the river, and in the night after the fire, the spilled coffee and rice in the crystal clear waters of Drina had so swollen up, that it looked like countless sea shells.

During the fire, the view from the bridge of the Turkish quarter on the other bank, was also interesting. All the Turkish women were dressed in dark, hooded cloaks and were twisting their heads like chickens, so that they could have a better look of the fire, through the slits of their veils.

A military detachment arrived from Ohrid with a sprayer, but only the heavy roof-tiles (Greek type) were to be thanked, in the heat and drought, that only four buildings were burned down.

I might have forgotten all this, had it not been for the old house of boukhta, whose peeled walls of unbaked bricks were swelling, because the rotten beams, placed crosswise and slantingly, were giving in to the weight of the Turkish tiled roof. The two Bulgarians scholars and writers, Dimitar (1810) and Constantin (1830) Miladinov had been born here. Also here, because of a report on him by the Greek bishop Mellenthius, Dimitar had been arrested by Turkish policemen, chained, and sent off to Istanbul. It happened in 1861, the same year that had promised to be a very happy one for the two brothers, since thanks to Bishop Strossmayer, their common work, the first of its kind in Bulgarian literature, with great importance for Slavic science, had been published in Zagreb.

![]()

31

"Bulgarian Folk Songs, Collected by the Miladinov Brothers", was a book, with whose partial translation Joseph Holecek began his work in the field of South Slavic themes (the heroic songs of the Bulgarian people).

The life of the Miladinov brothers, even though they had not fought with a gun or a sword, belongs to the great epos of the Balkan Slavs of the past century, because they are one of its cornerstones. They are among the first, most skillful scholars in the farthest removed Western Slavic region, on the Greek-Albanian border, where a means for liberation had yet to be found, since the usual formulas of a Southern revolt or guerrilla warfare had to be excluded. Here, plus the Turk as a political enemy, there existed another, more dangerous one: the Greek, who had the Church and the schools in his hands, and for centuries had Hellenized the Bulgarians from Epirus to the Danube.

The same fate awaited the two brothers, the oldest and the youngest of the six children of a local potter. Dimitar's daughter, now living in Sofia (an orphan since the age of six), says that her father would have most probably been Hellenized, had it not been for the fact that as a gifted child he was given, while very young, to the St. Nahum monastery, on the southern shores of Lake Ohrid, where thanks to the reading of Church Slavonic books, he had become conscious of his Bulgarian origin. But his real awakening had come later, when he, a grown up young man thanks to his savings and other support, was able to continue his studies in Yanina, the then cultural center of the Epirus Greek. The same thing happened to him, that had happened to Jan Kolar in Jena (and almost at the same time): the Slavic names of the rivers, mountains, and communities in this Greek region, reminded him of a sorrowful condition of the vanishing Slavdom, and his ties with expelled Italian immigrants helped him mature, a process which occurred in his soul. Dimitar returned from Yanina as a great Hellenist, but at the same time as a convinced fighter for the salvation of the oppressed Bulgarian national spirit.

At home, in Macedonia, he had worked as a Greek teacher in different places. He reminds us of our revival leaders, who officially, had been exemplary German teachers, but privately — enthusiastic fighters. He had taught the Greek language at school, but Bulgarian language and national history and geography at homes, households, and shops, for which, with a full lack of books, he had had to prepare all by himself. Under his enchanting figure and apostolic zeal, Hellenism

![]()

32

had melted away in Macedonian towns and villages, as spring snow.

At the same time, Dimitar had become educator and guardian of his favourite, 20 year younger brother, the gifted Constantine. He had made an associate of him, but also, unfortunately, a comrade in the suffering and the martyr's death. Its reason had really been tragic. It was the Hatred of the Greeks, reaching its highest point, when to the Bulgarian consciousness of the two brothers, the Slavic one had been added as well.

In this sense, the year 1845 was fateful for them. The Russian scholar V.I. Grigorievich, went to Greece that year, to study the traces of one-time Slavic settlements there. While traveling through Macedonia, he had met Dimitar in Ohrid and had been amazed by his Hellenistic knowledge. Dimitar had become a conscious Slav then. He had traveled through Herzegovina, where in the town of Mostar he had been enraged by the haughtiness of the Greek clergy, and afterwards in Bosnia and Serbia. He urged the young people to go to study in Russia, and had later sent his own brother there. His view, that first an independent church and school must be won, had already become dominant and his belief grew stronger. That was why he worked most zealously in Ohrid, the seat of the Greek Metropolitans.

The famous Serbian writer Branislav Nushich, who visited Ohrid in 1892, wrote the book "A Region, Enveloped by Lake Ohrid" afterwards, in which he pointed out that he had found only twelve Greek homes there, with one boys' and one girls' Greek primary schools, while the Bulgarians had four boys' and two girls' primary schools and a high school as well. Nushich described Dimitar's great merits, and his flexibility, with which he had managed to win over the guilds and the rich Greek-following families, and acknowledged his efforts for the appointment of Bulgarian clergymen and the creation of an independent church. He added that Dimitar's activities had been facilitated by the awful attitudes of the Greek clergy, and especially the atrocities, performed by Bishop Melenthius, of whom the people had said that "he makes Ohrid's stones and Ressen's families cry". Nushich said that "the people were horror-struck with fear". Melenthius would make slanderous reports to the authorities, and afterwards would ask for a bribe, in order to help release the person from dungeon. He had made a lucrative business out of it with the Christians. The people had sent message after message to the Patriarch,

![]()

33

but nothing had happened. The Turks, themselves were sorry for the Christians, and had sometimes taken them under their protection. But the voice of the people had not been heard, since they had no leader. Nushich went on: "Dimitar took that task upon himself and performed it excellently". I would have added: heroically, as well.

But we must correct Nushich, since he used, perhaps by oversight, the Serbian spelling Miladinovich, instead of the Bulgarian one, Miladinov, and it is necessary to add that Dimitar had not only fought for clearing the church away from the Greek influence, but, and it was more important, he was a Slavic Revival leader of the Bulgarian people. And for that reason exactly, together with his brother Constantine, he had paid with his life, slandered as a dangerous element to the state who maintained ties with the Russians.

Milenthius otherwise known as a lecher, had performed his vile deed in the beginning of 1861. Dimitar was staying with his family in Strouga, when a warrant for his arrest had been issued, and through Ohrid, he was sent to Istanbul. He had already been tied up, when he had parted with friends and students, and as we heard, he had stated an assumption that he would never come back.

At that time, Constantine was finishing his studies in Russia, without any foreboding for what had happened. In the spring he started homewards via Vienna, where he met Strossmayer, whom he had shown his collection of songs, ready for printing. But it was written in Greek, while Strossmayer wanted to publish it in the Bulgarian alphabet. So Constantine went with him to Dyakovo and for three months wrote the manuscript. When it was published in Zagreb, in the summer, he presented the first copy to his well-wisher and hurried to Belgrade with the other one, to present it to the Bulgarian politician Rakovski, who was staying there at the time.

He was happy until he arrived, but he had heard from Rakovski that his brother was in an Istanbul prison. He hurried to Istanbul and asked to see his brother. Instead, he was arrested himself. He did not meet his brother until they were finally transferred to a military hospital, both seriously ill, some time in the end of December. Both of them died there. We don't know if they were able to recognize each other, as we don't know when exactly they died whether in the end of December or in the beginning of January, or where they had been buried.

![]()

34

Strossmayer heard of their arrests in October and immediately wrote to the Austrian Foreign Ministry and to the Embassy in Istanbul, and also intervened with the Russian Ambassador. But the insidious poisoners had anticipated it. To this we must add: probably. But we will not be unfair if we fail to do so. The Miladinov brothers' death, even if it wasn't caused directly by the Phanariots, among which we must include Mellenthius, was at least a result of their actions and a goal of their aspirations.

Who are the Phanariots?

Phanaer is a Greek quarter in Istanbul, where the Patriarch lives, and a Phanariot is a type of Greek, who began developing after the Turks' arrival in Europe, and means a sum of all possible human evils. It is necessary to state that to a large extent the Turks are to blame for his evolution. It had been beneath the Turks' dignity to study the languages of the conquered peoples, and so they had needed interpreters. The Greeks had served as such. The proud Turk had never concerned himself with financial questions and had never collected interest; the customs, the levies, the taxes, and later the monopolies and the leases had become to a certain extent a Greek privilege. So the real material oppressors, blood-suckers, and tormentors of the Christian population were the Greeks and not the Turks. Since the Sultans had not been able to imagine the Christians in another way, except as a unified church, like the Muslim one, they had presented the Greek Patriarch with total powers over all Christians in their Empire. It might be useful to determine one day, how much of the so called Turkish tyranny, may be attributed to the Turks, and how much to others.

The Serbian scholar J. Tsviich, while explaining that the Slavs in their majority had been shepherds and peasants, i.e. common people, says that the charshiya (the town marketplace) had been possessed by the Geeks, and he adds that the Turks, had been the ones to introduce honesty in trade.

So it should not amaze you, that when I arrived in Strouga, I immediately tried to find the Miladinov house. The man from Strouga, who promised to show it to me added unexpectedly, "But not before sunset".

"Why can't we see it now?

"We can, but someone might see us."

I was surprised. "What do you mean?"

---------

![]()

35

He raised his shoulders and said, "In Turkish times, we could celebrate the memory of the Miladinov brothers every year, but now Belgrade doesn't allow it".

I was troubled and shocked, How could it be possible? Their suffering, and their martyrs' death is respected by all Slavdom. Most probably, there is some administrative misunderstanding as a result of the last war, which will be removed, when the tension between Serbs and Bulgarians decreases.

I was a bad prophet. Four days later, on August 3, at 2 P.M., a fire broke out exactly in the same house. I can still see how one of the descendants of the Miladinov family was helping his pale and fainting, beautiful wife, out of the burning building.

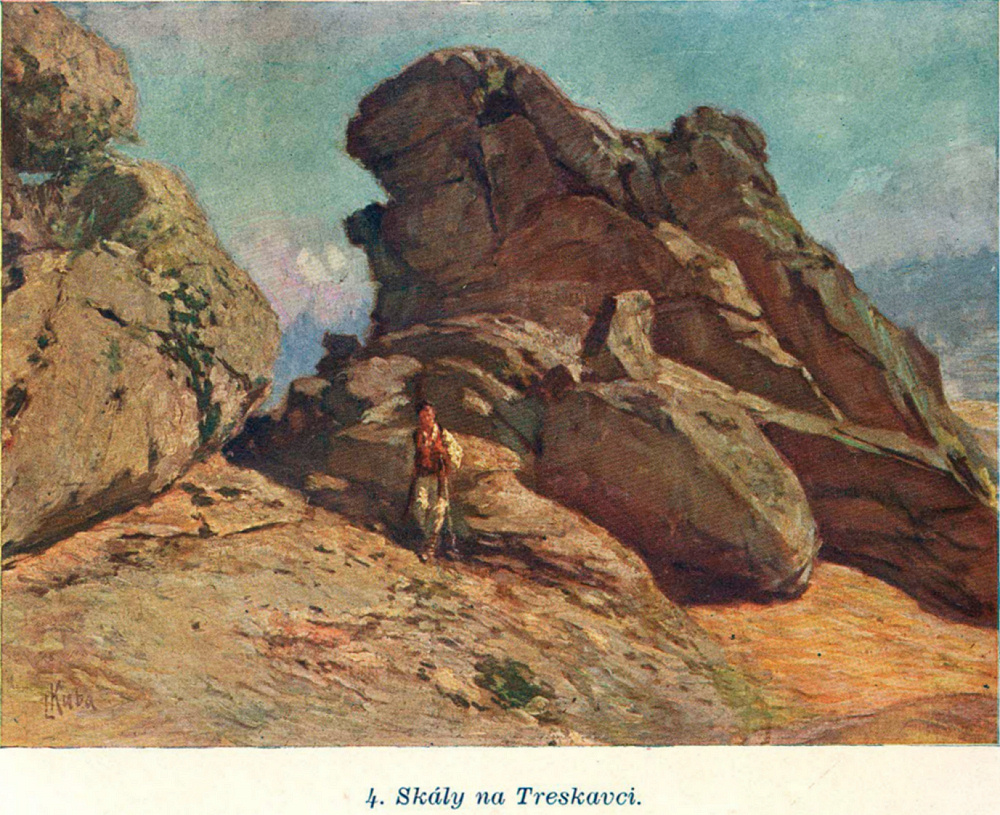

One had only to negotiate a couple of ridges, Boukovo and Giavato, which separated the Ohrid valley from the eastern, Ressen (Prispan) alley, and the latter from the Bitolja valley, and the whole distance was just 80 kilometers.

When in the evening, we reserved a seat on the postage car, for the next morning, we asked once again, to make sure, when would we start. and the old postman, from whose bumptiousness it became clear that The Vienna Reparations Commission, Austrian Heritage, had assigned him from somewhere in Slavonia, smoothed out, without stopping his work, his huge moustache, unnaturally large for his small height, and added abruptly, "At five." Then, Raising his stern eyes, he added with an even sterner voice: "Come earlier! The car doesn't wait!" The last word he either cut into pieces, or accented.

At that moment, we didn't feel what a great truth that small man had uttered. The automobile really didn't wait, but we did, for two and a half hours. It was being repaired from the morning; not without reason and not uselessly at all, as we soon saw on the road.

When that contemporary coffin, with eight passenger seats (and certainly not for "wiser" passengers), finally arrived, among the eager candidates for free seats there ensued such a scramble, that we understood nothing. Why should one run in this hot climate towards the inconvenient circumstances which await him inside? No one will reach his destination faster. Why then hurry to get into the car?

![]()

36

But the moment the doors were shut behind me and the car started eastward, my joking mood left me. I had found the answer: in the constant collisions with the numerous stones, in the inevitable holes, the long vehicle, according to the law of the lever, jumped much more in its back part that in its front one. In the front it just hit you, but in the back it threw you up into the air. We fell very hard each time, as if we had neither artificial, nor natural cushions beneath us, the latter created farsightedly by nature. During the flight, our legs lost their support and couldn't soften the fall with any resistance. And this intermediate form between motoring and aviation would go on for five hours! Our first stop would be somewhere around Boukovo! Wonderful!

Under the circumstances, it wasn't surprising that we forgot to say farewell to the magnificent picture which Ohrid presented with the lake, from the eastern heights, and which we had admired during our outing to the St. Petka monastery, which was pressed like a swallows' nest to the mountain wall. On the other hand, while speeding along the encircled valley of the Kriva Reka river, we suddenly remembered that a disaster must have befallen the succulent peaches in our pockets, in the jostle during our rough journey.

The empty paper bag, by now containing almost only marmalade, created new difficulties. What could I do with it? It was impossible to throw it out, since the windows were closed, in order to protect us from the dust. And it was impossible to eat its contents, because of certain technical reasons. Who could guarantee that I wouldn't miss my mouth? And if I didn't, who could guarantee that I wouldn't bite off my tongue? Why, it was precisely because of all the jolting that we couldn't utter even a word!

The only thing left was to hold the treasure uselessly in my wet and trembling hand and to wait for a stop. Actually, we couldn't even think of eating. The land version of seasickness was trying to affect us all. It even succeeded with one of the passengers, because, whether he liked it or not, he quickly confessed to us of his breakfast or supper (which, of course, none of us had even dreamt of).

Such was our journey along the famous Via Ignatia. It wasn't built for us, of course, but for camels and mules, on which probably, the whole journey from Drach, via Ohrid and Salonika to Constantinople and back again was comfortable. For cars, it had great shortcomings, created only by our hurried decision.

![]()

37

We hadn't traveled more than half an hour, when the valley was filled with a loud sound, which seemed like a gunshot. The car stopped and we jumped out quickly and happily.

Strictly speaking, we didn't act correctly. It was widely known that attacks were quite a normal thing here, and therefore we should have crouched fearfully inside. Instead, we were all yawning and stretching ourselves outside. The driver announced that we had a flat tire and someone angrily, and I think quite frankly asked, "Isn't it a bit early for that!"

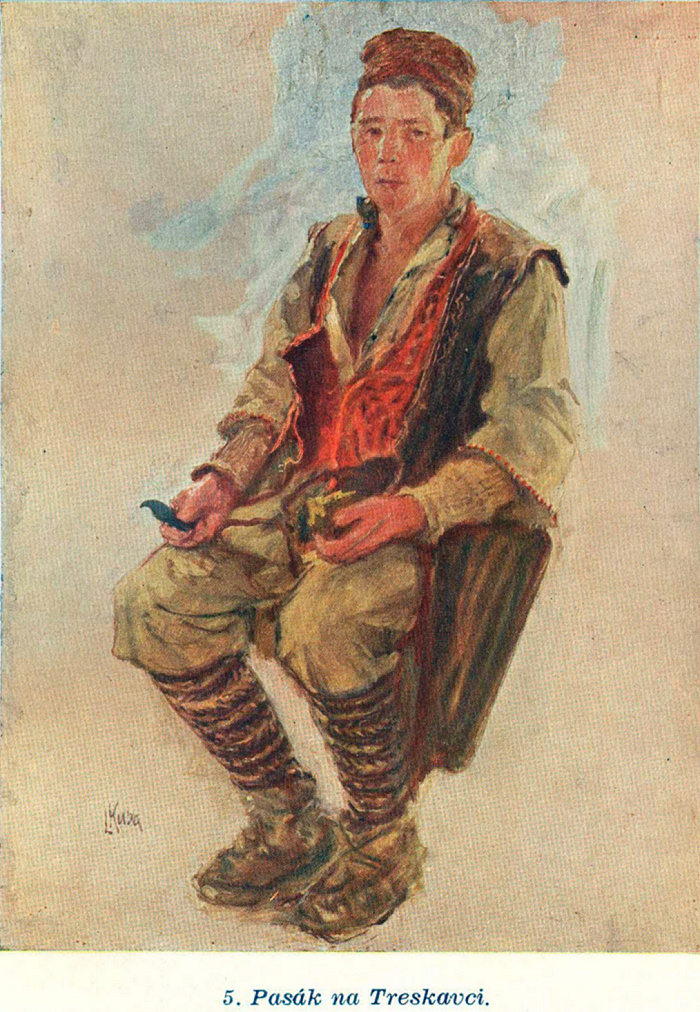

The conductor and the driver started working, while we scattered lazily beside the road, in the smoothed grass. We hid like a flock, which probably also rests in midday after grazing all morning. It must be very tiring to find something worth grazing here, for all the grass has withered, and the only things that haven't are the stones. The hot days can be endured only by the enormous sheeps' tails (babiak), diverged as candles from the Old Testament and glowing in the blazing sun.

We were not ashamed to steal mental property, so we comfortably imitated the postures of the four-legged creatures, as we watched, together with them, how the angry driver threw himself under the car, and lying on his back raised the lever, in order to be able to take out the wheel. He rolled about in the thick dust, as in fluff, and resembled a small animal sucking its mothers teats. The cows watched his actions with understanding, and probably, the only thing they wondered about, was the fact that when he finally came out, he was not refreshed and strengthened, but on the contrary, the poor man was very tired, and in the short while, with the exception of his hair and moustache, had turned white.

A shepherd came down the mountain slope, stuck one end of his staff in the ground, pressed his back on the other one, and watched the repairs quitely for half an hour. He received an award for his patience.

"Here! Make yourself a pair of rubber sandals!" said the driver finally, throwing him a piece of the torn, rubber, outer tyre.

We began cramming in car, and someone mentioned with a quiet sigh, "Yesterday they had flat tyres twice". No one reacted to this, not even with the quietest sound. It was not in our authority to decide, whether we would finish the journey at one go or with stops, and I swear, it was difficult to say which was preferable.

Soon, the car reached the curves and started upwards with a pitiful

![]()

38

whine, which increased proportionately with the distance, until we reached the top of the ridge at Boukovo.

We stopped there, this time not because of any reason of ours. A policeman asked for our passports. We were near the three borders: the Yugoslav, Albanian, and Greek. The representative of law and order took pleasure in our faces, while comparing them critically with the photographs, and we were delighted with the even more beautiful view: the enormous Prespa valley, towards which the road wound like a snake and stretched out into the hazy distance, where we recognized the center of the panorama, the town of Ressen. An enchanting stop!

But not for everyone. Our friend from Bitolja, not long ago, had gone through something quite different. He had started for Ohrid, and by a fatal accident, had forgotten to take the necessary identification papers. The policemen, with lengthy insistencies, had offered him hospitality, which our friend had been reluctant to accept. Finally, on the driver's advice, they had phoned Ohrid, after which he had been regarded as an incog in the car, and almost ceremoniously, had been sent straight to the superiors. So one of our not very shrewd compatriots had become a guest of the Yugoslav state, and in order not to bother with the officials' sleep, had spent three days as such.

None of us, though, was surrounded by such mysterious circumstances, which gave us a feeling of greatness. So we were soon allowed to continue with a gesture of cool respect.

We squeezed together, as mosaic pieces, in the car, and allowed ourselves to be rushed towards the precipice, each one calculating quietly, approximately when should we arrive in Bitolja. There was some erroneous naivety, since we didn't include any accident in our calculations.

But after Ressen we again heard a shot, and the consequences were well know this time, the only difference being in the details. This time, it wasn't just a replacement of the inner tube, since there was no spare one, but its difficult mending. That was why the conductor and the driver arranged their instruments as in a field kitchen. A little later a policeman, who had thought it was a gunshot, came. He was disappointed, and before he left, he said sympathetically, "You have 27 kilometers to Bitolja".

"Are we ever going to arrive," remarked an anonymous passenger, looking desperately towards the conductor and the driver, who looked like cooks, and now even like bagpipers.

-------

![]()

39

The driver himself, when all was ready, thought it necessary to comfort us a little. He swore to his soul that we would arrive safely. The wheel, according to him, was double. It had two tyres, one beside the other, and the second one was still all right.

The car drove off, leaving a heap of cut off pieces on the road, like a traveling cobbler.

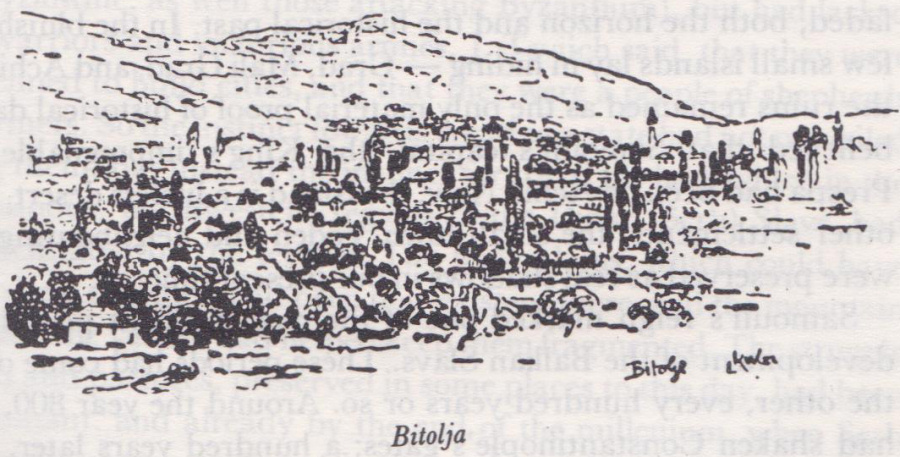

Just below the 2400 meter high Pelister peak, we topped the Giavato ridge without any incident, and arrived safely in the millionaires' village of Kozhani, whose sons assiduously earned the bread, and if fate willed, some capital, with which they improved their place of birth. With revived hopes, we continued towards Bitolja. A cheered up, young Turk heightened our spirits when he offered us fruits, which he had received from his mother (without a veil), after which he began singing passionately. He was helped by his desire and his high spirits. Suddenly the Turk's song stopped. There was another shot! But the car didn't stop. Only the conductor asked us to sit on the left side. We could fulfill his request, since half the people had got off at Kozhani. Only 15 kilometers were left. Still, were we going to reach our destination? I was asking myself in my heart. We reached it!

The second tyre was punctured just before Bitolja. The car leaned sideways and stopped. The heartbroken conductor asked us to walk to the post office, where we would receive our luggage.

It was noon, exactly, when wobbling beside the crippled automobile, along the muddy Bitolja streets, we arrived.

Bitolja

![]()

40

We almost missed it. Partly because in Ressen, the postal car only exchanges the mail, and partly, because the nailed windows were covered with a thick, impenetrable layer of dust.

Fortunately, soon after Ressen, before the lake had vanished from the horizon, we had a flat tyre, and while the driver and the conductor were heating the glue and cutting the tyre, as if they were preparing goulash, and were testing, repairing, and blowing what not, we, comfortably situated on the slope, managed to devote ourselves to our impressions of the magnificent view, and to historical memories, thankful to the accident, which the others cursed ceaselessly.

The poor present did not correspond with the great past of this Slavic road. Almost everything, made by human hands, was from the glorious age, which nine centuries ago had spanned over the whole Balkan peninsula, and had brought fame to the miserable and great Bulgarian King Samouil. We viewed the lake from the north. The valley merged with it, with an intermediate green strip, from which numerous branchy trees stemmed attractively.

The 15 kilometers long and 20 kilometers wide surface was shining, two and a half hours away from us by foot, surrounded by mountains on all sides.

To the west was the Galichitsa ridge, cutting off the neighbouring lake Ohrid, and to the east was the almost 2500 meters high Pelister, on whose slopes we were resting.

The lake was divided almost in the middle by the Greek border, and behind it was the real historic center. But in the fog, everything faded, both the horizon and the historical past. In the bluish haze, a few small islands lay in hiding — Grad, Mali Grad, and Achil, where the ruins remained as the only material proof of historical data. It is believed that Samouil's capital, the King's impregnable retreat Prespa had been on Achil. Now, the island is a lifeless desert. His two other settlements, the small town Voden and neighbouring Ohrid, were preserved as real shadows in our present time.

Samouil's reign marked one of the most brilliant periods in the development of the Balkan Slavs. These periods had come one after the other, every hundred years or so. Around the year 800, Kroum had shaken Constantinople's gates; a hundred years later, Simeon

![]()

41

had proclaimed himself Tsar of Bulgarians and Greeks; and around the year 1000, Samouil had united the Balkans — to the north, as far as Sava, to the east, beyond Sredets and Preslav, and to the south and west to the seas, with a Patriarchy and 30 episcopates.

But let us imagine the situation in the Balkan peninsula at that time.

According to the Greek concept, until the arrival of the Turks, the peninsula had always been theirs. By giving priority to cunning before wisdom in politics, the Byzantines had readily turned misfortune into success: when defeated, they had left "the territory to the enemy, as a willing gift", and when victorious, they had assumed that they had only an apparent vassal and whenever, as in the beginning with the Bulgarians, they had been forced to pay them tribute, they had considered it only as a redemption for peace. The "vassal" relationship had depended, of course, on how much luck the Greeks had had (or had not had) elsewhere.

Their cunning had not been advantageous for them. To the Bulgarians and the Serbs they had consigned the historical role, by all means to try to defeat and conquer the Byzantines.

The fact that the Bulgarians had made the first attempts in that direction, may be explained by a number of circumstances, of which the proximity of Constantinople was neither the sole, nor the decisive one.

When in the seventh century, the Emperor Heracles had ceded territories to the Slavs in the Balkans, he hadn't done it out of love, but because he had needed buffer states to repulse the raids of the nomads. However, the Slavs had served as mercenaries in the armies (the Byzantine, as well those attacking Byzantium), but had lacked great warriors and victorious armies. J. Tsviich said, that they were not inclined to build cities, and that they were a people of shepherds and farmers. So the instinct towards creating a state had not prevailed among them, but instead the instinct for tribal life had, which in the mountainous, northwestern regions of the Dinar (Serb) Slavs, had been facilitated by the terrain. The wide plains, which could have united them together, had been non-existent there, and the mountain peaks and the valleys had helped keep them fragmented. The struggle for land and pastures, preserved in some places to this day, had been predominant, and already by the end of the millennium, when Serb statesmen's names, such as Cheslav or Iovan Vladimir, with a conscious

![]()

42

goal towards unity had begun to appear.

Things were quite different with the Bulgarians. The original Slavic tribe on the fertile lower Danubian Moesia, and the wide plains of Thrace and Macedonia, interrupted only by two mountain ranges, the Balkans and the Rhodopes, Otherwise, enough territorial conditions for the unification of the people of eight tribes had existed. And when the alien, not numerous, but belligerent tribe of the Tartar Bulgars had conquered them, and afterwards imperceptibly merged with them, a new whole, refreshed by the bellicose element, capable of creating a state, and supported by nature in its enterprise, had appeared. They had widened their authority over Thrace and Macedonia with comparative ease, but when they tried to conquer the northwestern, mountainous corner and to subject the Dinar Serbs, their attempts were less successful and lacked constant results. In the ninth century, Mikhail Boris, the father of Simeon the Great, had already reigned over Ohrid, where he had sent Clement and Nahum, banished from our lands, as Christians missionaries.

When, by the end of the tenth century, Simeon's Empire had begun to decline, through the fault of his successors, the Greeks had managed to subject the eastern half, while in the western a ferment had remained, in the person of the mysterious Voivoda Nichola, chief of the Birzatsi tribe, which has preserved its name to this day and whose southern territory we had just passes through. Living just north of Lake Prespa, Nichola and his four sons started rebeling when the Empire had begun declining, and at the most difficult moment, the young Samouil, who had miraculously restored the great Slavic Empire, was enthroned. Its nucleus was in Macedonia, but the state had stretched from Greece to Sava, and from the Adriatic to Sofia. If Macedonia had ever become a political term, it would have been then. The moment had been ripe for the creation of a unified South Slavdom.

But it had never happened. During Samouil's reign, in 1014, his Empire received a heavy blow from the Greek Emperor Basil II Bulgarslayer, and in 1018 (during the reign of Samouil's third successor) it collapsed.