227

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XV.

He shall mark our goings, question whence we came,

Set his guards about us, as in Freedom's name.

SITTING on the bed at the inn we gloated. The keen delight of the blockade-runner and of him who has done his opponent in the eye was ours, and we prepared to enjoy said opponent's discomfiture up to the top notch. Moro gave him a quarter of an hour to make his appearance - I allowed him twice as long. He was there in five minutes, in the form of a monkey-faced police officer whose countenance grew more akin to that of an astonished ourang-outang as his mind grasped the thing that had happened.

Keeping a tight hold on Sandy we served out to the man a few of the choicest items slowly and one by one, and let them soak in. Curiosity fought with politeness as his questions tumbled over each other and his eyes blinked and stared in bewilderment. "From Palanka - without teskari - and without escort!" It was too much for him to tackle alone, and in ten minutes he was bowing himself off to the Konak to get someone to help him unravel the mystery.

![]()

227

We dined sumptuously on roast lamb and pilaf (rice and gravy)-five days of eggs and bread are sufficient at a time-then, the beds being uninhabited, came sleep of the finest quality, and a great deal of it.

Two dowdy constables appeared to have spent the night on the billiard table below-stairs, but it was too lumpy to be a comfortable bed. They followed us sleepily towards the Konak. Hardly had we got under way when the street began to rock, and tiles and other bric-a-brac came rattling into the roadway. I stepped gingerly over a chimney made of petroleum tins. (The petroleum tin holds Turkey together as the raw-hide reim does South Africa.)

'Then come to Macedonia, where there's something in the air:Djuma seemed to have been quaking - off and on - for some weeks, and everybody who disliked bricks on the brainpan had gone into summer quarters under little arrangements of planks which leaned against the more solid of the garden walls. All the minarets had snapped off short like sticks of white Edinburgh rock, and any parts of them that had not gone through the roofs of the mosques lay about the front door in sections. A slight shock every other day kept up people's interest, which might otherwise have flagged.

If there ain't a revolution, there's a tromblemong de terre."

The Kaimakam held his court on a ring of cane-bottomed chairs in the open. He was a puzzled and uneasy man, but covered his feelings under

![]()

228

courteous enquiries, and by degrees we learned that we ought by rights to be dead several times over from a variety of picturesque causes which included brigands, murderous villagers, and other perils of the "Interior." The presence of a fatherly Colonel of the Line prevented our telling the great man that the only people who had caused us acute anxiety were his own soldiers. The fact was, he could make neither head nor tail of us, and we learned later from a friendly native that he viewed our doings with the keenest trepidation. Such a thing, he said, had never been done before, and he sincerely trusted would never be attempted again.

Every Kaimakam is responsible for the peace of his district, and if two Europeans were to disappear within his jurisdiction and the Turkish Government were made to pay compensation to the tune of some thousands of pounds, his subsequent place in the administration of his country would be a low one. We were suspected first and foremost of being in collusion with the insurgents with the object of bringing off a bogus "capture," and sharing the ransom to be extracted from the Government with the Revolutionary Committee at Sofia. Secondly we were accounted spies, who were stirring up the Christian villages against the Turks and reporting on the state of the country to Bulgaria. Many other deep designs were laid to our door, but finally they remembered that

"Allah created the English mad - the maddest of all mankind!"and left it at that.

![]()

229

They could not lock us up without complications ensuing, so turned their attention to the unfortunate Alexander whom they could and did get a "cinch" on, and on hunting the hostelry for him next morning it appeared that he had been borne off to gaol by the seedy constables. This was "most tolerable and not to be endured;" take away our mouthpiece and we ceased to live! But no sooner did the two madmen's shadows cover the threshold of the Mansion House than the prison gates sprang open and the criminal shambled out with a grin. He had been arrested because "no one there knew him," a terrible but hardly unexpected contingency a hundred and fifty miles from his home, so in case of his meeting any more people to whom he needed an introduction he was kept within hail after that.

My flannel trousers were now no more than honourable relics, so the local Poole was called in and manufactured a pair of tweeds (of the fashionable cut known as the "Djuma bloomer"), within two hours. I wear them yet - on dark nights.

Some one had seen refugees on the road from Barakova, on the frontier line, and for this spot we accordingly set out accompanied by many armed guardians, ahorse and afoot. These last started with such a swagger that it was considered well to take some of the head off them, and putting up best pace we soon had them cooked, with their tongues hanging out. This, in a way, squared accounts with the Palanka people who had been allowed to triumph over our supposed weakness.

![]()

230

At Barakova, where the road leads on to Rilo and Dubnitza, is a wooden bridge over the river which divides Bulgaria from Turkey. With a certain appropriateness the Turks' half of it is painted black and the other half white. Up and down adjoining planks in the middle pace the two hostile sentries - together, as comrades in the same squad. Part of the bridge had collapsed in the earthquake, but as each side swore it lay in the other's territory it stood very little chance of ever being repaired. A few huts and a low cook-house for the troops lay between the road and a standing camp. The tents were pitched upon circular mud walls two or three feet high, which made very comfortable dwellings of them, and the officers' tents had wooden doors and cushioned divans round the inside. It was midday, and the men were drawing rations, carrying on their heads trays with a roasted lamb curled up on each.

Lamb is the only meat the Turks eat; they never kill cow or calf for food, and of course the unclean pig is accursed. The troops get this meat ration once or twice a week in well-fed regiments; otherwise they live sparsely on pilaf and bread.

Over the river on the Bulgarian side was a gang of refugees resting on their way back to their Turkish homes. Our escort, fearing an escape of their two prisoners, at first would not hear of our going over the bridge, but after a good deal of trouble we got across, and the feeling of freedom which the society of those honest flat-capped soldiers inspired was strangely welcome. The

![]()

231

Turks who "shadowed" us became ill-visaged pigmies beside the big, hearty Bulgarian officer, pledging us at his garden table.

The ragged crowd returning into bondage squatted among their ponies and bundles on the ground. Among them were men and women I had seen at Samakov, strengthened and stiffened in the back by nine months of a freeman's life, and eager to be hewing timber and putting new homes together on the old wasted ground.

In a little while they lashed the packs on the

![]()

232

ponies, humped their bundles and plodded over the bridge in a shower of rain. One of the men wore a European straw hat he had picked up somewhere. At the Turkish post a mouthing importancy with papers appeared to bid them show their baggage, and there in the drenching wet their poor bits of belongings were opened and flung into the pools, to be mauled and sniffed at by a dirty gendarme.

A strong effort was made by the authorities to stop their obtrusive visitors sketching and photographing this incident, but the deed was done, and any little popularity we may have had vanished like the dew; the posting of some letters over the border had also helped to create a coolness. That was the only time I ever saw Turks turn their backs on a visitor and leave him to himself, so they must have been thoroughly disgusted.

In a little back street at Djuma there lived an old pope who had some refugees with him. Sandy discovered him and arranged an interview, but just as we were starting, a polite message arrived begging that the visit might be postponed for an hour, as the earthquake in the night had somewhat disordered his house. Eventually the disturbed establishment was reached, and having packed off the last surviving watchman shortly beforehand with a note to the Kaimakam we felt fairly sure of ten peaceful minutes. The holy man was very old and very fat; still blowing from the efforts of propping up his dwelling with poles. We sat on a sort of broad landing at the top of the staircase

![]()

233

with the floor on a slew, and the returned exiles wandered up.

A man in a skin cap had just come in from Dubnitza with his family. He had been sent by the Bulgarians in a carriage to the frontier, and there - having saved a little money - had hired horses and brought his weary women-folk into Djuma. His village was Bistritza - four hours away - where, since the people had been driven out, the troops had settled themselves in any houses that were not flat on the ground and gradually used them up for firewood. Their owners, now straggling back, were living four families in a house until they could rebuild the missing ones. The Turkish Government, said Skin-cap, gave 500 piastres (about £,4) to a family as a loan, to start them anew, and took a charge on their farms for repayment. Men whose houses had been effaced were given 50 piastres each (about 8s.) with which to rebuild them - "but there are plenty of soldiers on the road between the frontier and the village. He is a clever man who can get home with his fifty piastres!"

In the middle of the conference there was a trampling on the stair, and a red-faced police-sergeant arrived to bear away Sandy "to sign a paper."

"Why, yes," observed Moro, shutting up his note-book, "we'll go along too - we'd like to witness the signature."

So Sandy was not "jugged" that time.

In the meanwhile the wires were at work. The

![]()

234

Kaimakam was anxious to see the back of us. "Il donnerait une bonne pièce pour vous voir filer," said our native friend - but he was also anxious to hold on to Alexander and visit the sins of the masters on the head of the servant.

Our idea was to work across country to the southeastward down to Drama on the Constantinople-Salonica railway line, thus bringing in the famous Raslog district and some of the destroyed villages. The official idea inclined strongly to the main road down the Struma valley to the railway at Seres - a quiet route, and not liable to excite foreign visitors.

So we compiled messages to our Consuls which were carefully muddled in passage and arrived in Consulate Row in the form of transposition puzzles, bearing the mystic signatures, "Morabos" or "Botamore." The Mayor meanwhile loaded up the wires with long communications to his superiors containing business and compliment in a ratio of one in forty.

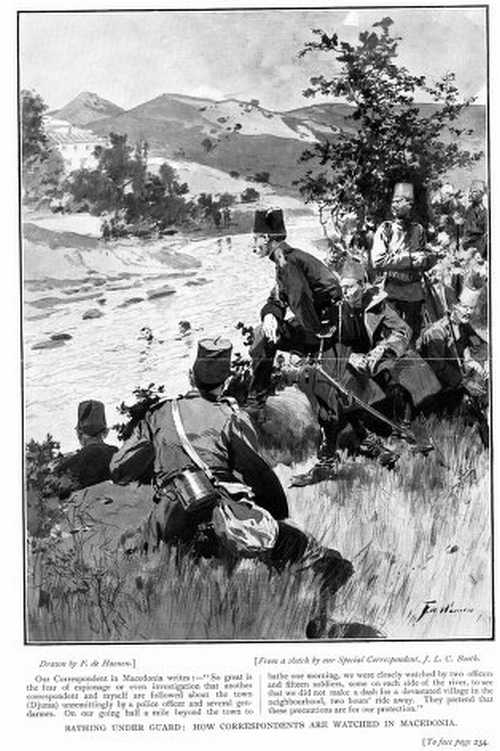

During this turmoil of telegraphy we started out one morning to bathe in the rippling rivulet which watered the outskirts of the town. But this would not do for Detective-Inspector Aziz Bulbul, following lest our erring feet should stray.

"Better not bathe here - horribly uncomfortable - good bath-house in the town."

"We are going to bathe here."

"But no! The children of these parts are evil and would cast stones at you, and that would be a cause of shame (une honte) to the Sultan."

![]()

Bathing under guard: How correspondents are watched in Macedonia. [To

face page 234.]

![]()

235

"We should hate to embarrass the Sultan, but we are going to bathe here."

"You cannot bathe. Kaimaknam Bey's orders."

"Tell Kaimakam Bey we wait here until he sends permission to bathe."

Exit Chief Constable, leaving posse on guard.

In five minutes he was back with a section of infantry and an officer, who spread themselves picturesquely over the landscape on both banks, whilst the two mad ones sat in the midst of the waters - at a depth of fully nine inches - consumed with great mirth.

Out of the wilderness, one evening, appeared two ladies on pack ponies, with an escort of twenty Zaptiehs. [Mounted Police.] They were Mrs. King-Lewis and a Bulgarian lady finishing a tour of the wrecked villages to the eastward, in which they had been distributing funds collected by the European Relief Committees - £500 or £600 a village. They were housed, roughly enough, in a tent near the Konak, and sat on tin boxes eating English biscuits. What such a journey must have been for two women one could dimly guess. An enormous weight of gold on their persons, wooden pack-saddles to travel on; heat and discomfort by day, verminous hovels to lie down in at night, and an utter want of privacy at all times. Worn out by want of sleep - an impossibility in those crawling dens - they had taken to the open and endured cold or drenching rain on the bare ground. Withal they were cheery and by no means missed the

![]()

236

comic points of their pilgrimage. Stout-hearted gentlewomen, who had not been slow to answer the ancient call "Come over into Macedonia and help us."

The commander of the escort chucked his head and clucked to himself as he saw the English lady safely over the border next day, on her road to Sofia. "Mad - all mad - even their women!"

There is a story of a hot-tempered Irishman who made his way to the frontier one day, very sick of Turkey and eager to get out of it. At the post he found a police-officer of some cosmopolitan knowledge, who remarked "Where is your teskari?"

"Haven't got one."

"Where are you going?"

"To Hell."

"Then show me your excommunication papers," says the Turk, quite unperturbed.

For a week we looked up the Kaimakam once or twice a day, bailed out Alexander now and then, and held our bathing parade, which had now become a regular thing. Still the calm and placid Bey answered all enquiries as to permits with "pas encore arrivés, Monsieur," ordered coffee and talked most amicably. At last, when the souls of the waiting ones were growing sour within them, and the permanent smell of rotten eggs in the hostelry flavoured all one ate, drank, or smoked - at last, at the silent hour of two a.m., an orderly with a telegram blundered upon our slumberous solitude. A message in Turkish from my long-suffering Consul at Salonica: - "You can go by

![]()

237

your own road and take interpreter - have made it all right with authorities" - or words to that effect.

"Ce n'est pas ma faute!"

Next morning the missive was laid before the Smiling One at the Konak, who denied that there was any mention of our henchman in it. We might go, certainly, when his orders arrived, but the boy must remain behind. Feeling sure that the Kaimakam had allowed himself to overlook a word or two, the slip of hieroglyphics was borne off to the friendly native, who soon furnished a word- for-word translation in which Alexander figured largely. Returning with this revised ver-

![]()

238

sion to the Konak, the combined vials of Anglo-American wrath were overturned on the head of the Wily One, and Moro's command of the French language being unequal to the occasion, he delivered his opinion on the matter in New Orleans "straight cut." During this bi-lingual blessing the astonished official and his scandalised friends learned that to-morrow was our day for leaving Djuma, with or without ponies or escort, but certainly with our talking-machine, after which announcement we stalked haughtily from the shanty, whilst the Kaimakam followed to the door waving his arms and wailing, "Messieurs, ce n'est pas ma faute! - ce n'est pas ma faute!"

An hour later an apologetic myrmidon of the Police persuasion came to say that by a strange coincidence permission had just arrived from the Governor-General for our departure. He lingered awhile to paint the beauties of the main road aforementioned, and the official breast evidently harboured a dying hope that we might be lured back by that route.

That afternoon a General of great girth was expected in the town, and troops paraded in their best patches from dawn to dark; officers in sham boots rode passaging ponies on the toes of the front rank, trumpets howled, and the man of men - blowing through his nostrils like a pedigree Shorthorn bull - compassed the length of the street without falling off, for which all credit to him.

But to adorn his temporary abode the front windows of two Christian houses were cleared of

![]()

239

their rows of flowers by order of a throaty Colonel - everyone looking on - and the owners were made to carry them up to the General's house, well knowing they would never see them again. Not a very serious incident in itself, but the Turk draws no line between flower-pots and any other Christian property.

Betimes in the morning there was a sound as of merry roysterers below,

and coming down into the common room we found half a dozen shabby troopers

doing horse-tricks round the billiard-table, and catching one another mighty

cuffs on the back, bellowing in vast spirits. Outside, their little troop-horses

- buried in front and rear packs, coat-rolls, saddle-bags and oddments

- munched hay out of a trough. Some peasants held three miniature animals

who bore the stamp of sorrow strong upon them and were destined for our

use. The gear was slung on, the escort mounted and closed round, and through

a crowd of gay-coloured Tziganes, [Gipsies.]

green-turbaned Pomaks and all the rags and bones of a Turkish street, we

jogged out on the trail again.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]