214

PART II. MACEDONIA, 1904.

CHAPTER XIV.

But that we have we gathered

With sweat and aching bones.

WE were now, as near as could be reckoned, within about forty-five miles of Djuma-bala, our point, and shoved along hoping to make it the next night if the luck held. Once in the frontier-town one could take an "easy," collect information and consider the next move, whilst the authorities got over their excitement.

In the meanwhile we were making ourselves horribly conspicuous by prancing along a main trail with all this entourage, and soon looked likely to suffer for it. Travelling companions gathered to the number of about thirty, all keen on knowing our destination, and as much recent history as they could get at. This habit is one of the courtesies of the road in Turkey, where a native traveller would consider himself slighted at a want of interest in his doings if a chance companion forgot to demand a recital of his past and prospects. Sandy, worse luck, had not the gift of silence; knowing which we never entrusted him with any future plans beyond the name of the next village,

![]()

214

and for all he knew at any time we might be making for Siberia or the South Pole. About five times a day he took an oath of solemn silence as to our recent doings and the country we had travelled through, and just as often as a native ranged alongside we heard the whole blessed directory of placenames rolling off his babbling tongue, like a porter at Clapham Junction. When reproved he would put on a pained face: - "Mais, M'sieu, qu'est-ce qu'on peut faire? - 'Faut étre gentil, au moins!"

Half-a-dozen Turks rode up through the rabble, all stuck about with knives and pistols, and a bullyragging way with them. Although inclined to be familiar and asking Moro and myself a string of questions in Turkish, they showed an ill-natured objection to being called Bill and lightly bantered in English, turning huffy at last and refusing to speak. One of these rode a little Barb mare, with a foal running by her side. Her ears were clipped, and there was hardly enough of the near one left to call an ear. Sandy, who had long ago outgrown surprise at my ignorance, explained that the animal had obviously been sick. Naturally when a horse is sick you cut off bits of his ear, and it follows that in a beast of delicate health a great deal of ear is absent. I asked what, in the case of a confirmed invalid, would be the direction of the treatment when both ears had been pruned down to the parent stem, and was not surprised to hear that the tail was the next on the list for reduction. Should the malady stubbornly refuse to yield during the piecemeal removal of this appendage,

![]()

215

the victim is usually left to die in its own way, the resources of veterinary science being at last ex hausted.

A "Vlach."

In the case of bovines, as I shall show later, surgical treatment is not always resorted to

![]()

216

The Macedonian Veterinary Handbook, with a masterly simplicity, classes every ill known to the animal world under the one word "sickness," directing that the manner of dealing with it shall vary slightly according to the breed of beast smitten.

The mare with the two "off" ears was soon cantering up the road, with her master and his delightful friends very stiff at leaving no wiser than they arrived. All the same we were not sorry to find the trail by and by leading too far to the southward for our line, and persuading the disgusted Alexander to take to his sore feet again the trio struck out across a wide, shallow river - too dirty to drink - for the north-eastern hills.

The gods were with us that day, for as we rested on the new-found path another pack-train wormed its way up the hill, and again the suffering Sandy became "M.I."

Good fellows those Vlachs - a wandering tribe from Wallachia who roam the mountains from end to end of Macedonia with their rats of ponies, doing most of the carrying trade of the interior. Hillmen and horse-lovers - grave and little given to speech; striding in their white kilts and long blue coats, with a bird's-eye cloth wound turban-fashion round their heads. Generally they have well-cut features and a long fair moustache, and their blue eyes - puckered at the corners in a hundred wrinkles - look you straight and honestly in the face. They are mostly Roman Catholics, and are the only native people who do not

![]()

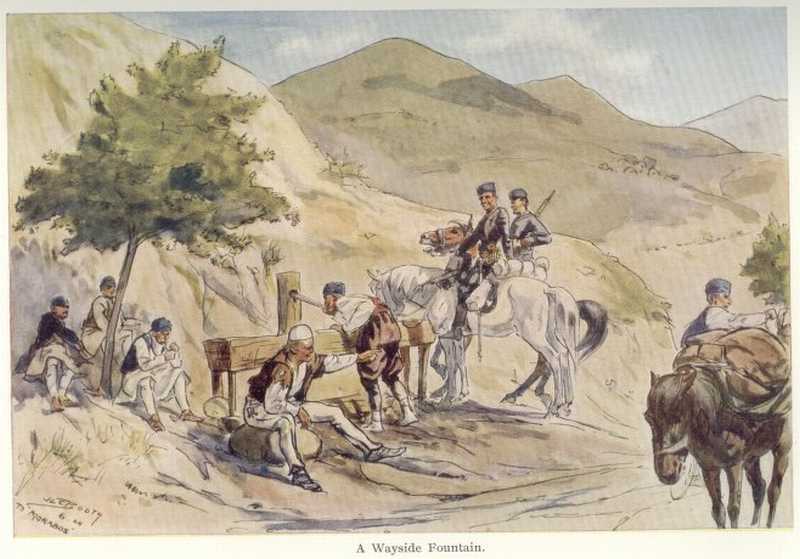

A wayside fountain (Coloured)

![]()

217

concern themselves with the race-wars of that turbulent land. They and their ponies are free of the whole of it, and they want no more.

The two obstinate foreigners who insisted on walking when they might ride puzzled them a good bit, but "live and let live" is their motto, and they said little beyond noting approval of our length of limb.

Four hours we clambered in the sun - the promised village always "just ahead" with the trail - thirst growing and thriving on the white dust that lined the throat and tasted sour on the dry tongue. Worse than blistered feet and chafing boots, that make you turn your feet sideways on the steep down-grades to save your crumpled toes. From every crest we searched the long descending trail for the little square fountain or the wooden trough that should be bubbling by the wayside, and once, unkindest cut of all, found one - tinder dry.

Chewing a leathery bread-crust from a forgotten pocket to create saliva, we went limping on till at last - there it was! A real running spout of cold water, sticking out of a tree stump and pouring into a trough. Of course we ought to have rinsed our mouths out and gone on, and of course we drank a quart apiece and bid good rules go to the devil. Here, whilst we rested, a gang of Arnauts [Albanians.] joined us - insolent rascals according to Sandy's translation; we gave them the cold shoulder and forged ahead. Serpentining through a rocky defile, where the going was execrable, we came out bang

![]()

218

in the middle of a picket of Albanian soldiers sitting under a big acacia.

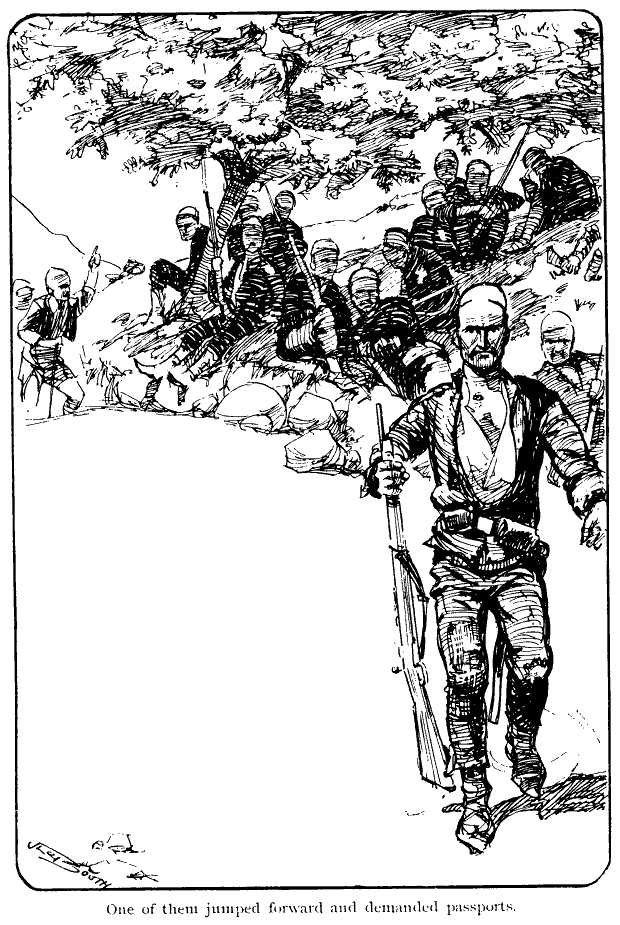

One of them jumped forward and demanded passports. I told him we only showed them to officers, on which he answered that there was no officer for miles, and he intended to see them then and there. The "high and haughty" seemed the game to play, so we cocked our hats, put on enough "side" for a sergeant-major, and started to swagger off up the track. I think the "grand air" might have succeeded, but at that moment the Arnauts from the watering-place arrived, and in six words had set the whole gathering against us. They all got on their legs and swarmed round growling, and for a few minutes things looked rather nasty. Suddenly - seeing bayonets and whatnots uncomfortably near him - a happy thought was born in Sandy's noddle.

"The English passports with the great red affairs."

Excellent lad! It was a hundred to one they could not have read a Teskari if we had had one, and these many-folded documents from home were far more imposing. Out they came, and with drawn brows the unshaven ruffians studied Lord Lansdowne's signature upside-down. But the seals did it - "the great red affairs." Obviously nobody who bore such a sign as that on his person could be stopped by anyone under a General of Division. But they were loth to let us go, and shouted a volley of threats after us that contained no inducement to linger about for the next three

![]()

219

One of them jumped forward and demanded passports.

![]()

220

miles. From the top of a hill we looked back over the plain and made certain they were not following up with the intention of keeping their unspeakable promises.

A couple of hours later we fell in with a Bulgarian who lived hard by, and took his offer of shelter for the night. In a narrow hay-field where an old man wielded a queer-shaped scythe we plumped down and lugged off our boots. Moro's sole had been flapping in the air for miles, lashed on with relays of "morceaux de ficelle " from Sandy's endless coils. In the matter of raw toes we were about square, but I was "one up" on blisters. The Bulgarian came back with his wife - a real beauty - and three or four towzle-headed youngsters in simple garments created by cutting three holes in a sack and sticking head and arms through them. The woman was called Seraphim. She had a refined English face and shewed a beautiful set of teeth when she smiled. Her rough shapeless clothes looked incongruous, but it would have been a shame to put her small feet, tanned and well-shaped, into any sort of stockings and shoes.

The family cow was suffering from an overdose of green barley - she had spent the previous night in the old man's patch - and was at the point of death. The household was untiring in its efforts to save her life, and sat up all night, taking turns at rubbing her mouth with salt.

This exercise I put down to a praiseworthy desire to create a counter-irritant, and so take the patient's mind off the real trouble, but the family's genuine

![]()

221

disappointment at not reducing her distended carcase by scrubbing her nose raw showed their unshaken faith in the "cure."

But it aint no use to be doen' that,as old Skip used to sing. I suggested hot blankets as a preliminary, and was listened to with the silent tolerance one shows for a child's babblings, whilst Father fetched a fresh supply of salt.

Fur it's down in the stummick where the misery is at,"

Seraphim and a pretty daughter brought out a tin of fried eggs and a flat brown loaf to our tree in the grass, and these vanished at great speed. In eleven hours' trekking we had covered about thirty miles with no more than a couple of hardboiled eggs at mid-day, and by eight in the evening had honest appetites.

The old man with the prehistoric scythe, whose relationship was obscure, came and sat under the tree and chewed "Pioneer" with relish. He spat meditatively, and observed that he had had a shocking bad opium crop.

"If I had been a wise man I should have sown nothing but barley. But - who knows? - perhaps I shall not be able to reap as much as I have now. Do the strangers know the ways of the tithe-gatherer? He comes and looks at the crop, and he puts down on paper that it is worth so much, and one ok in every ten I have to give the Government. Ay, and much more than one ok. They won't let me reap it till the tithe-gatherer has seen it, and often he does not come till the corn

![]()

222

is over-ripe and rotting. Then I get nothing. If there is any good corn left it goes to the Government - I reap it and I get nothing. And this year the Turks will not let us get help for the harvesting; each man to do his own - no neighbour may help him."

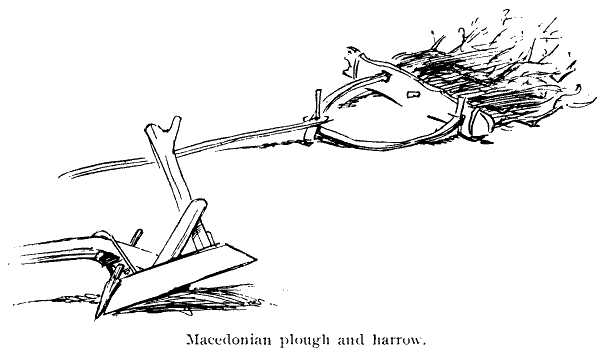

I figured out the price they got for their barley roughly, about nine shillings a quarter. Their implements of course are of the roughest. Harrows are made of thick brushwood kept in place by two cross-pieces of wood, with a single pole for a man to haul by. A plough, compared to this, is modern, and some have an iron coulter to "face" the wooden mould-board.

The old man wandered off to look after the cow, and pater familias took his place. He was the picture of the happy family man, with a cheery laugh and an easy acceptance of the little troubles of his life. Here was at least a Macedonian who lived the home - life like people in other lands; quietly, and unharassed by his rulers.

"What was that? Went to Bulgaria last year! Why did you do that?"

The same old story.

"Fear of death. The soldiers came once and were coming again; - I did not wait for them."

So much for the one untroubled peasant!

"And how did your wife and all these children stand the journey?"

" Oh - I left them behind."

"You did? And weren't you afraid of what the soldiers might do to them?"

![]()

223

"Ah, well! - one can always get another wife."

So much for the family-man!

He went into the cottage and gradually silence came down. The insects hummed under the trees, and the stars looked through the leaves. I did not watch them long . . .

Macedonian plough alnd harrow.

In the morning the cow was better - an undeniable advertisement for the salt treatment and the family had recovered their spirits. As we soused our heads in the stream a hardy man appeared with two ponies for our use. "Father" lent another, and after Alexander had been taught how to take a photograph of the gathering, we mounted the hen-coop pack-saddles, and with two natives leading pushed through a belt of trees for our last day's journey.

On the other side of the belt, within a hundred yards of our sleeping place, was a Turkish post.

If either had known the other was there we

![]()

224

should not have had such an easy night, but once more ignorance was bliss. The soldiers were half-asleep, there was no officer, and the all-powerful red seals waved in their faces again did the trick. Of course, if they had arrested us at this stage they would only have taken us into Djuma under guard, but it was our intention to go in as free men. Certainly our luck was holding.

The ponies travelled in a string - one behind another; before the leader walked one of the natives. They had always travelled so, and as soon as their guide disappeared they stopped. Like their masters they had no initiative, but went well enough when led.

All that scorching day we only passed one village. Creeping through its very outskirts, half-hid in green mealies, a Turk rode up behind and started bawling to the people. Some of them began to run towards us, and we bustled the ponies into a canter. There was a camp above the village and the long-delayed capture seemed to be due at last.

"Come along, let's have a ride for it, anyhow!"

"That is nothing, monsieur," said Sandy, " he is only telling them the cows are in the corn."

At mid-day we halted where a herd of goats were stripping the bushes under a big walnut tree. Hard by was an old water-mill, and the parchment-faced miller proudly showed his flat round stones that ground the corn between them. A wood-paddled shaft, revolving in the rushing water beneath the floor turned the lower stone. In Shetland I have seen the self-same mill, and a

![]()

225

miller in the same cow-hide charouks [Sandals.] tending it.

On the hillside some Bulgarians were "leading" hay. Never were known such people for thick clothes! Under a sun that turned white paper yellow in an hour, men and women struggled with the wiry hay in all their layers of winter wool. Of all the jackets and thick folds of cloth they abated not one. The white-cowled women - diamond patterns on their brown petticoats - heaped the hay with two-pronged wooden forks. Then came the men and thrust it into nets, whilst ribby ponies - buried under these - staggered across to where the stack grew by the straw-thatched hovels.

Riding and walking - a wonderful relish for walking those pack-saddles give you - a deserted sand-coloured country slipped past. Oak and ash grew thick on the hills, but no corn in the valleys, and never a hut in all the rolling miles of it.

About four the path turned a corner, and below us lay the Struma valley, and the wide eau-de-nil river flowing down to Lake Takinos, a hundred miles to the southward.

Here again was the hand of man, and the tobacco-fields and gardens parcelled the road-side. Among the trees of the distant plain showed, at last, the roofs of Djuma.

Down the long valley-road behind the plodding natives - hardly touched

by their thirty - five mile march and as the sun sank over the hills behind

us we rode into the town.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]