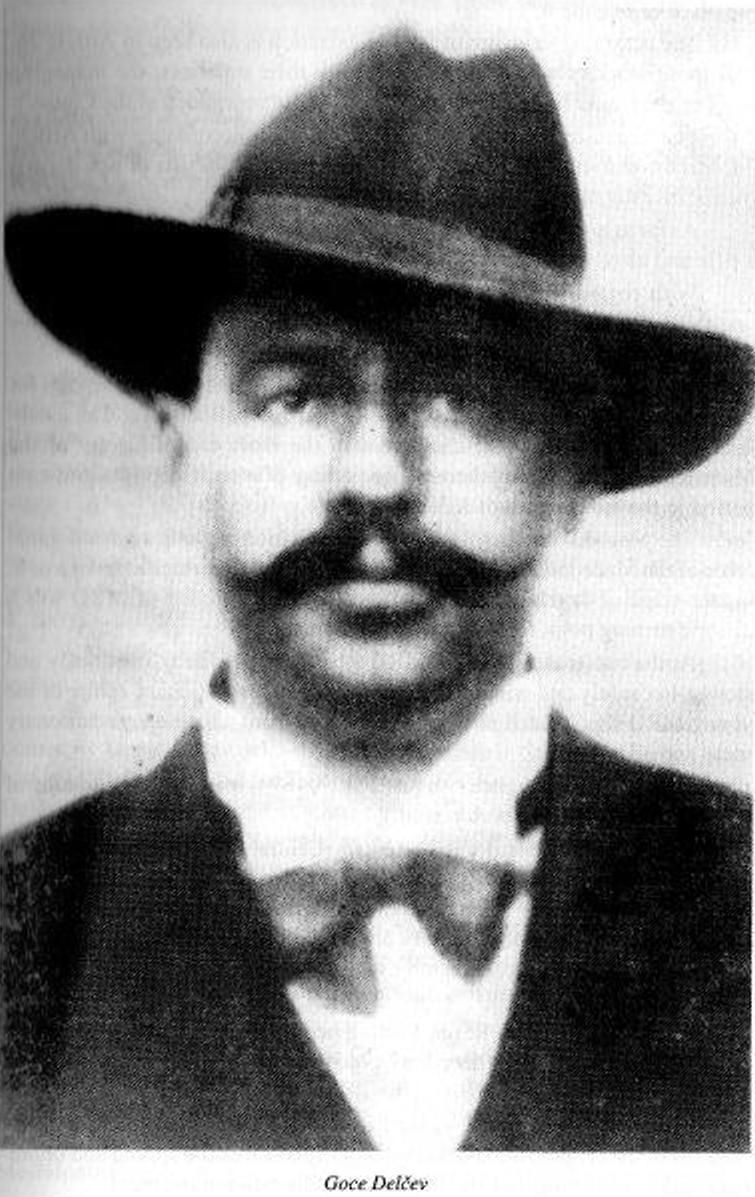

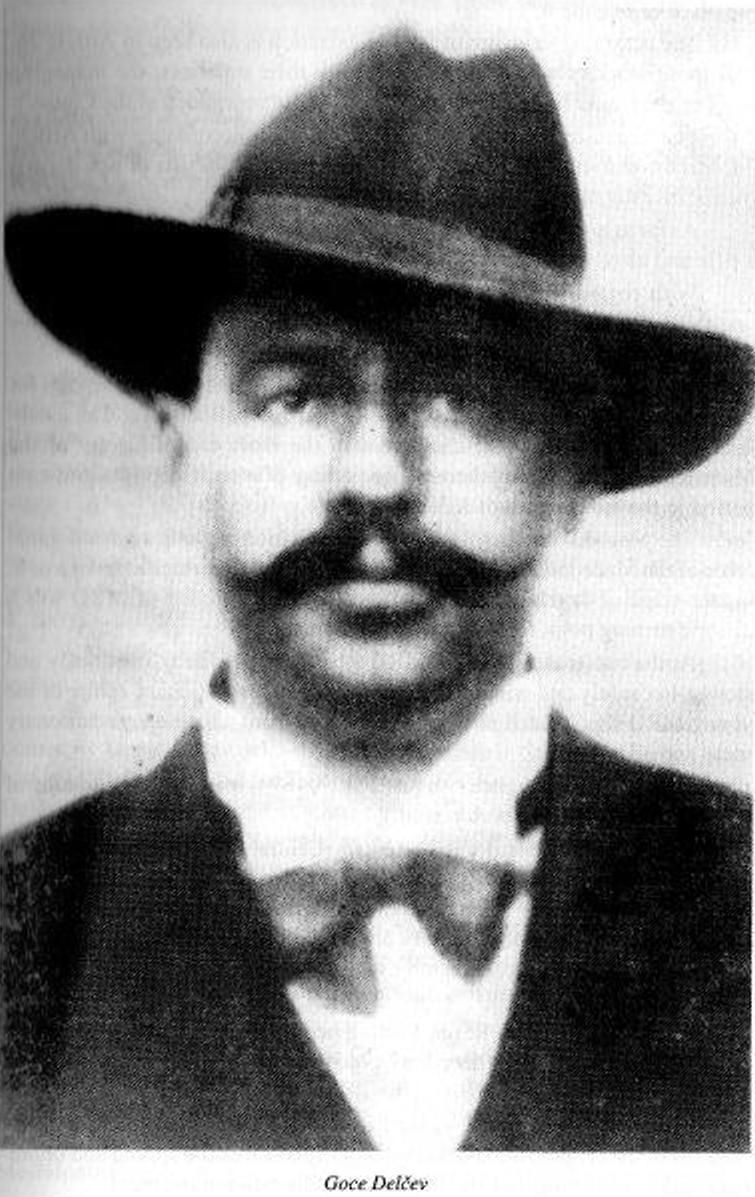

The soul of the Macedonian Organization

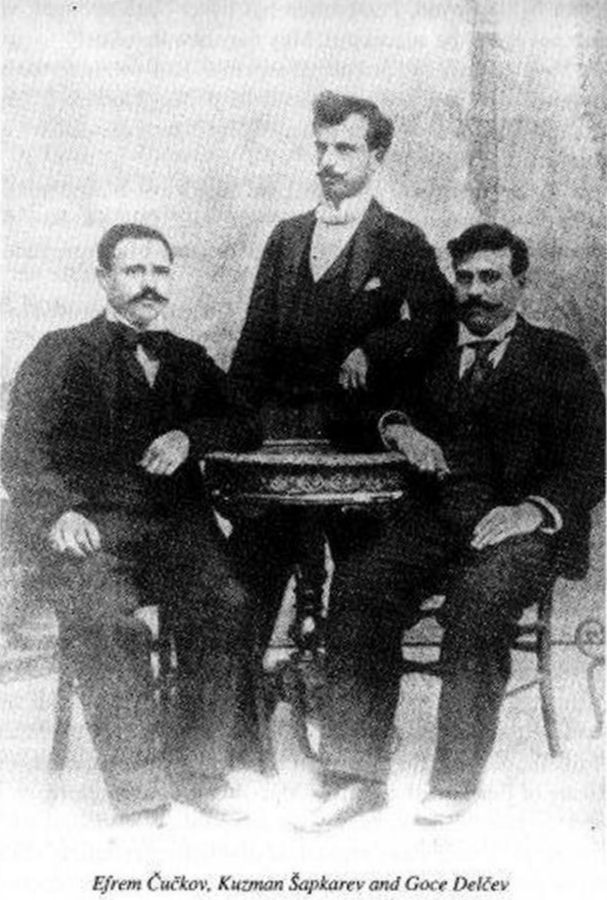

was Goce Delčev – that Balkan Garibaldi...

N. Rogdaev, Burevestnik 16/1909

Prologue

9

I. Roots

11

II. Growth

13

III. Outlook 29

IV. Stormy Years

32

V. Epilogue

120

Legacy

123

PROLOGUE

Rare and exceptional people are a dignity to the whole of

humanity. Goce Delčev is one of these.

Goce Delčev, the person and his work, is an inextricable part

of the recent history of the Macedonian people. His name personifies the

admirable achievements of the Macedonian Ilinden generation.

Goce Delčev emerged as the visionary, ideologist, organizer

and leader of the Macedonian national liberation movement towards the end of

the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th.

The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (MRO) was founded

in the 1890s, in circumstances of bloc division between the European

imperialist powers, semi-colonial status in the Ottoman Empire and

widespread religious propaganda from the neighbouring Balkan states

nourishing aspirations towards Macedonia. MRO appeared in the role of an

advocate and torch-bearer of the Macedonian national liberation movement

which thus embarked upon a new, higher stage of development. It emerged at

the right moment to prevent the dismembering of the living body of the

oppressed Macedonian people. At the same time, this emergence

"marked the beginning of a newer, more developed stage in the

process of the national establishment of the Macedonian people. With the

help of this movement, the Macedonian people stepped onto the Balkan

political scene as an active national and political subject, clearly

announcing their aspirations towards their own national territory and

seeking ways of shaping their future national

9

and political destiny" (M. Pandevski). [1]

Furthermore, the Macedonian national liberation movement

propagated and supported the establishment of a Macedonian nation-state. In

addition, with its democratic bourgeois character, the Macedonian national

liberation movement also had the characteristics of a social and economic

revolution, overthrowing the feudal constraints of the backward Ottoman

state. The highest achievement of this movement, the Kruševo Republic, was

also a combination of the creative role of Nikola Karev and the visionary

messages of Goce Delčev.

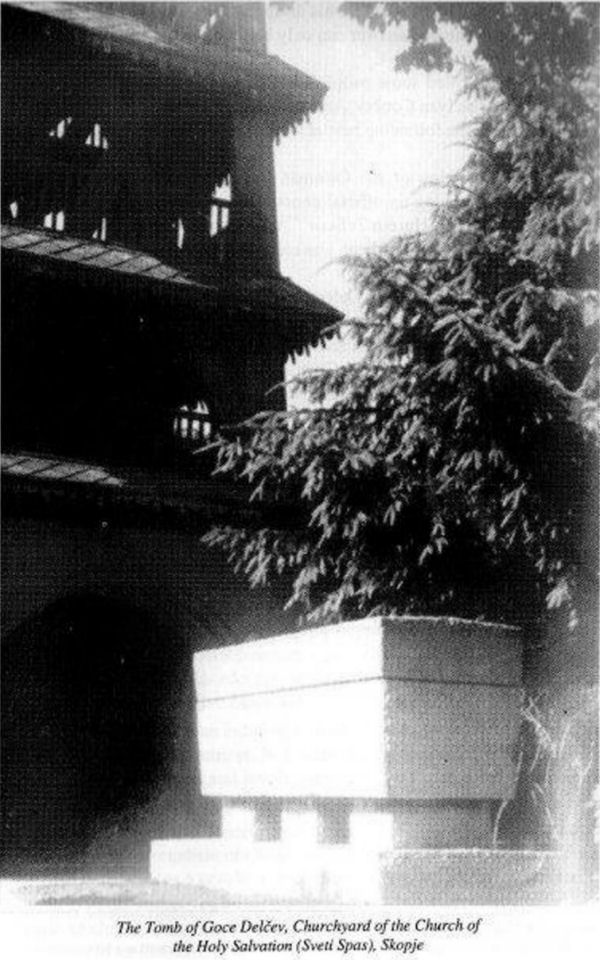

Goce Delčev enlightened Macedonia. He was a sublime offspring

of his time. His brief but impressive life, from his birth in Kukuš to his

death in Banica, was wholly dedicated to his people. He bequeathed the last

and most fruitful decade of his life to the Macedonian national liberation

movement, to the uncompromising Macedonian struggle for national and social

freedom, to his own people. His active presence on the Macedonian historical

scene in the turbulent period between 1894 and 1903 greatly enhanced the

Macedonian national liberation movement from the end of the 19th and the

beginning of the 20th century.

1. For reasons of space, this edition docs not contain

footnotes giving details of the literature used. Readers are directed to the

Macedonian edition of this book which contains a further 860 footnotes (See:

Димитар Димески: Гоце Делчев, Скопје 1992).

10

I. ROOTS

1. Goce Delčev was born in Kukuš, a well-known

centre of the Macedonian Revival movement, situated in the coastal region of

Macedonia, 35 kilometres north of Salonika.

In the late 19th century Kukuš had about 12 thousand

inhabitants. There were two thousand Macedonian families and only about two

hundred Turkish houses, as well as a few Romanies.

Renowned Macedonian revivalists such as Dimitrija Miladinov,

[2] Rajko Žinzifov, [3] Partenij Zografski and Kuzman Šapkarev left a deep

impression on this typically Macedonian region. It is not by chance that the

town of Kukuš has been immortalized in the excellent poem ‘Longing for the

South’ by Konstantin Miladinov. [6]

Situated close to Salonika — the Macedonian metropolis of the

time — the town of Kukuš was also known as a ‘political nest’. It was the

centre of the important Kukuš Union. A strong revolutionary upsurge was also

felt during the Great Eastern Crisis (1875-1881).

2. Dimitrija Miladinov (Struga, 1810 – Constantinople, 1862),

great Macedonian revivalist.

3. Rajko (Ksenofont) Žinzifov (Veles, 1839 – Moscow, 1877),

Macedonian revivalist and writer.

4. Partenij Zografski (sacral name: Pavel Trizloski, village

of Galičnik, 1818-1876), Macedonian revivalist and metropolitan.

5. Kuzman Šapkarev (Ohrid, 1854 – Sofia, 1909), Macedonian

revivalist.

6. Konstantin Miladinov (Struga, 1830 – Constantinople,

1862), Macedonian revivalist and poet. The international Struga Poetry

festival is held each year in honour of the Miladinov brothers.

11

There is no doubt, however, that this Macedonian lighthouse

of revival has been most celebrated in Macedonia and the Balkans as Goce

Delčev’s native town.

Obviously, this was the reason for the Greek army levelling

the town to the ground in 1913. However, this did not impede the spread of

Delčev’s charisma. The effect was exactly the opposite: the interest in the

fate of this small Macedonian town near the outskirts of Salonika became

even greater.

2. Goce Delčev came from the well-off Kukuš

family of Delčev. Goce (Georgi) Delčev was born on February 4, 1872, as the

first boy and third child in the large Delčev family which was to have nine

children. Goce had three brothers (Mico, Milan and Hristo) and five sisters

(Ruša, Coca, Tina, Lika and Elena). His father, Nikola Delčev, was also born

in Kukuš and his mother, Sultana Nurdžieva, came from the nearby village of

Murarci.

Nikola Delčev was engaged in trade and inn-keeping. He also

owned a flock of sheep. He was a prominent and highly respected citizen of

Kukuš, strict but righteous. His firm patriarchal attitude, however, did not

make his children weak as personalities. On the contrary, all of them grew

into freedom-loving, hard-working and self-conscious individuals. Their

amiable mother, Sultana (Nurdžieva) Delčeva, also had a strong and

beneficial influence on their upbringing

12

II. GROWTH

1. Goce Delčev spent half of his brief life in

his native town of Kukuš. It saw the first, almost idyllic period of his

childhood.

Some positive traits of Goce Delčev’s character became

apparent very early. For example, at the age of five, when his parents were

quarrelling. Delčev tried to protect his mother, showing a rare courage in

front of his strict father. His sense for protecting the opposed and the

weak seems to have developed at an early stage.

We know that Delčev had many friends as a child: Macedonians,

Turks and Romanies, making no differences between them. Here lay the roots

of his cosmopolitan breadth. Radical nationalism, chauvinism and ethnic

hatred were always foreign to him. On the other hand, his Macedonian

national feeling developed into a positive patriotism accompanied by an

international outlook.

Goce Delčev was a highly temperamental person: he would

easily burst into flames. He could not tolerate traitors even as a child. At

the age of 13, Delčev attacked a pupil from his school, a ‘traitor’, with a

small knife.

However, the young Goce was to draw a lesson from this

incident. He later developed a strong self-control. This is best illustrated

by the example of an insulting Vrhovist physical provocation at the

beginning of the century, when Delčev first pulled out his dagger, but

managed to restrain himself, threw the dagger on the floor and walked away

in a dignified manner.

The first stage of Delčev’s instruction is linked with his

native town of Kukuš. There Delčev completed his elementary education.

13

In the school year 1879/80 he was enrolled in the firs! form

of the Uniate School, but was later transferred to the Exarchal School.

Delčev was a good pupil. He was eager to team and developed a

love for books very early. Books drew him dose to the elder ‘learned’

town-dwellers — the teacher Hristo Bučkov, Dino Popgutov and Pone Ikiljulev

— who satisfied Delčev’s curiosity for knowledge by telling him interesting

stories and lending him books. He came across The Captain ‘s Daughter

by Pushkin. In addition, he read books from the junior grammar school

library, mainly world classics. The citizens of Kukuš could expand their

horizons by reading the works of Molière, Shakespeare, Lessing, Goethe,

Darwin, Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, Alphonse Daudet,

Pushkin, Gogol, Turgenev and Dostoevsky, the hagiographies of St Clement of

Ohrid, the biography of Alexander the Great, etc. There were also several

periodicals and newspapers.

In the school year 1886/87, in his native town of Kukuš, Goce

Delčev completed the third and last form at the Exarchal junior grammar

school with good grades. His hope to continue his education stumbled over an

insurmountable barrier: his father. According to Nikola Delčev’s unwritten

patriarchal rules, his first son had to inherit his father’s profession. He

considered the education Goce had acquired more than sufficient. Thus the

hunger for education of the disciplined son had to give way before the iron

will of the strict father.

So Goce Delčev became an apprentice in Hristo Basmadžiev’s

grocery shop in order to master the craft of trading. But soon afterwards,

instead of finding him in the shop, Nikola Delčev met his son in the street

bearing two jugs of water for the grocer’s wife. This unforeseen misuse of

Delčev’s apprenticeship was a harsh blow to Nikola Delčev’s honour, so Goce

found himself in his father’s inn. But his thoughts were drifting elsewhere.

Finally, his father’s blessing opened the way for his

education, thanks, above all, to Delčev’s older friends. So the Salonika

Grammar School did not remain only a vain desire.

2. It is an indubitable fact that Salonika — the

social, economic and cultural centre of Macedonia of the time — played a

special part in the moulding of the revolutionary climate in Macedonia.

The Ss Cyril and Methodius Exarchal Boys’ Grammar School was

the focus of revolutionary pulsation. Almost immediately after its

foundation in the early 1880s — in the school year 1882/83 — it was the

venue for certain revolutionary activities.

Prominent Macedonian and foreign teachers taught at the

Salonika Grammar School. The School itself, regardless of its Exarchist

‘Jesuit’ regime,

14

was a real nursery of revolutionary ideas. Banned books

circulated there, various plans were made and student rebellions were

organized. This School was the place where almost all the outstanding

Macedonian revolutionaries studied. Later, in the 1890s, they were to take

the leading role in the Macedonian national liberation movement.

Among the first students of the Salonika Exarchal Grammar

School were Ǵorče Petrov [7] and Pere Tošev. 18] As a result of the

well-known student rebellion in early 1885 they were expelled.

Three years later, in early 1888, in connection with a new

student rebellion, 19 students from the seventh form of the Salonika

Exarchal Boys’ Grammar School were expelled. One of the major reasons for

this was the demand of the students for the withdrawal of the Bulgarian

language and the introduction of the Macedonian "dialect" in instruction. As

a result, 26 students went to Serbia to continue their education, including

Dame Gruev, [9] Petar Pop Arsov, [10] Dimitar Mirčev, [11] Hristo Pop Kocev

[12] and Nikola Naumov. [13]

When Goce Delčev arrived in Salonika to continue his

schooling, the excitement among the older students over the above-mentioned

event had not yet subsided. This was in the school year 1888/89. Delčev was

enrolled m the fourth form. Three other boys from Kukuš were enrolled

together with him: Goce Imov, Goce Petkov and Hristo Tenčov. They were

accommodated in the Grammar School boarding house. This was the beginning of

the second, very important stage of Delčev’s education.

"All political, academic and cultural influences and aims

came through Salonika as the core, outlet and link of Macedonia with the

world. Hence this city became an attractive centre for the more alert

Macedonian forces who discovered the world there, receiving their essential

education, developing their fundamental principles and revolutionary

beliefs.

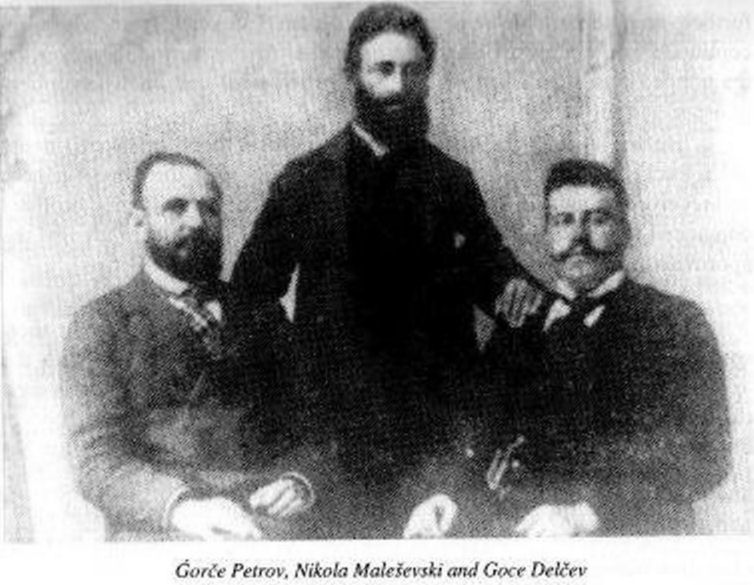

7. Ǵorče Petrov (village of Varoš, Prilep region, 1865 –

Sofia, 1921). Macedonian revolutionary and ideologist. Liquidated in Sofia.

8. Pere Tošev (Prilep, c. 1865/66 - Drenovska Klisura, 1912).

Macedonian revolutionary. Liquidated by the Turks on May 4, 1912.

9. Dame Gruev (village of Smilevo, 1871 – Petlec, village of

Rusinovo, 1906), leading Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of the

Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (MRO). Greatly honoured for its

establishment. Killed in battle against the Turkish army, December 23, 1906

10. Petar Pop Arsov (village of Bogomila, 1868 – Sofia,

1941), Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of MRO.

11. Dimitar Mirčev (Prilep, 1865 - Sofia, 1936), Macedonian

revolutionary. Secretary of Ivan Garvanov’s Revolutionary Brotherhood.

Secretary of the Central Committee of MRO during the January Salonika

Congress (1903).

12. Hristo Pop Kocev (Štip, 1868 - Sofia. 1933), Macedonian

revolutionary. Member of MRO Central Committee.

13. Nikola Naumov (Štip, c. 1871 – Sofia, 1934), Macedonian

public figure and journalist.

15

The Staff of the Ss Cyril and Methodius Salonika Exarchal

Grammar School, School Year 1888/89

[Therefore] eager for knowledge, Goce Delčev chose this city

and joined the vortex of new life with remarkable youthful vigour and

spirit" (H.A. Potjanski).

Salonika. Macedonia and the world now lay before Goce Delčev

as if on the palm of his hand. He was 16 at the time. He was older than the

rest of the students owing to the undesired break in his education, and was

thus more mature and more serious. At first he was rather shy. His best

friend was Hristo Tenčov [14] who later, in 1897, joined Garvanov’s

Revolutionary’ Brotherhood.

Goce Delčev was a good student in Salonika, just as he had

been in Kukuš. He was especially attracted to mathematics, mostly as a

result of his teacher, the mathematician Blagoj Dimitrov. [15] In addition

to the latter, Delčev had a high esteem for another of his teachers, the

poet Konstantin Veličkov. [16] Delčev spoke excellent Turkish, thanks, above

all, to the knowledge he had acquired in Kukuš. At the same time he was

utterly fascinated with Darwin’s theory.

Apart from his solid command of school subjects, Goce Delčev

constantly broadened his intellectual outlook. He dedicated almost all of

his spare time to the reading of books. The library had a good selection,

but he was not satisfied with that.

14. Hristo Tenčov, born in Kukuš. Macedonian politician and

medical doctor. From Aprit 1910 president of the National Federal Party (NFP).

Died in Sofia in the 1930s.

15. Blagoj Dimitrov (village of Embore, Kostur region,

1856-?), Macedonian educator and mathematician. Son of the distinguished

Macedonian author of textbooks, Dimitar Makedonski. Later became member of

the Macedonian Scholarly institute (MNI) in Sofia

16. Konstantin Veličkov (1855-1907), Bulgarian educator,

writer and politician. Minister of Education in the Bulgarian government of

Dr Konstantin Stoilov.

16

He also borrowed books from his school colleagues and even

ordered one of Ivan Turgenev’s books from Odessa by mail. At this time

Delčev became close to the most talented student of the Salonika Exarchal

Grammar School, Jordan Nikolov from Prilep, from whom he borrowed many

books, including works by Darwin, Pisarev and Flammarion. Goce Delčev knew

Pisarev almost by heart. In Salonika he also studied socialist literature.

At this time Delčev’s interest was mainly concentrated on

works of philosophy, history, revolution and natural history. He did not pay

much attention to belletristic literature, with the exception of poetry,

especially revolutionary poetry. He admired Hristo Botev’s revolutionary

poetry in particular.

It is known that Goce Delčev was a great admirer of the

immortal work of the pan-Slavonic educators Ss Cyril and Methodius. At the

moment when a student tried to ridicule the patrons of the Salonika Exarchal

Grammar School, Goce Delčev attacked him with the words:

"Sheep-head, remember that you must take your hat off

standing before those to whom you owe the tact that you can write your name

‘man’ even when you curse them!" (P.K. Javorov).

The Salonika Grammar School was well-known all around

Macedonia. There Delčev made friends with people from various parts of

Macedonia. It was in Salonika that he saw at close quarters the position of

subjugated Macedonia under the Ottoman Empire of Abdul Hamid. It was there

that his ideas for the struggle against tyranny were born. He wanted to

devote his life to this struggle.

"He repeated that freedom could be earned with sacrifices

full of blood, that those sacrifices must be made; but how?" (P.K. Javorov).

Goce Delčev’s first revolutionary gesture in public dates

from April 1889. At the celebration dedicated to the birthday of Sultan

Abdul Hamid II, []17] while all those present shouted "Çok yaşa!" (Long

live!), 17-year-old Delčev was the only one to shout "Aşaği!" (Down!). This

incident, which was ignored by the authorities, greatly strengthened Goce

Delčev’s reputation in the circles where he moved in Salonika. Words of

admiration could be heard everywhere in the grammar school: "The boy from

Kukuš spoke out for all of us today."

Towards the middle of 1889, six students of the Salonika

Exarchal Grammar School who had completed their education there — G.

Balasčev, [18]

17. Abdul Hamid II (1842-1918), Turkish Sultan (1876-1909).

Creator of the notorious ‘Regime of Oppression’.

18. Georgi Balasčev (Ohrid, 1869 – Sofia, 1936), Macedonian

public figure. Member of the Young Macedonian Literary Society (MMKD),

Sofia.

17

Sultan Abdul Hamid II

G. Belev, [19] A. Trendafilov, K. Karaǵulev, [20] D. Dimčev

and A. Čakarov — witnessing from close quarters the Exarchist

denationalization [21] policy, offered their services to the Serbian

propaganda hiding at the time under a Macedonist disguise, on condition that

they would be "teachers in Macedonia teaching in the Macedonian vernacular".

1. Georgi Belev, born in Ohrid. Member of MMKD. Later a

prominent activist and treasurer of the Supreme Macedonian Committee (VMK)

and one of Cončev’s men.

2. Kliment Karaǵulev (Ohrid, 1868-1916). Macedonian public

figure and linguist. Member of MMKD.

21. The terms denationalization and denationalize

are used throughout this book with the meaning of ‘obliterating the national

(i.e. ethnic) character of a people with the purpose of assimilation’

(translator’s note).

18

Half of them were founders of the St Clement Cultural and

Educational Association, Ohrid.

It seems that this act was not unknown to Goce Delčev.

Negotiations failed and they went to Sofia where they appeared among the

initiators of the Loza (Vine) journal movement.

These two fresh demonstrations of a pro-Macedonian national

character winch originated from the Salonika Grammar School (in 1888 and

1889) could not leave the more progressive students of the Salonika Exarchal

Grammar School indifferent.

A revolutionary spirit increasingly spread among the students

of the Salonika Exarchal Grammar School. In 1889, for example, three student

circles were active in the grammar school boarding house: the literary, the

philosophical and scientific, and the insurgent (revolutionary) circles. The

revolutionary circle was headed by Boris Sarafov [22] and Dimitar Pažev.

Other members of this circle included Goce Delčev, Hristo Čemkov [23] and

Atanas Murdžev. [24] The circle was a place where the works of Karavelov,

Botev, Zaharij Stojanov and Ivan Vazov were studied. The biographies of

famous revolutionaries such as Mazzini, Garibaldi, Washington, Lafayette,

Kostyushko, Dombrowski, Kossuth, Lavrov, Kropotkin, Bakunin, Stepnyak and

others were also analysed.

In the autumn of 1890, after Boris Sarafov and Dimitar Pažev

had left the school, Goce Delčev became the head of the revolutionary

student circle.

In 1891 Goce Delčev completed his sixth form. On the occasion

he was given the works of Aleksandr Pushkin, presented to him by the Vali

(Governor) of Salonika personally.

Seeing Goce Delčev’s imagination, sharpness of mind and

talent, as well as his knowledge of books, Dino Popgutov, a citizen of

Kukuš, prophetically told Nikola Delčev:

"You have an intelligent son, Koljo. He will he a great man!"

(K. Hristov).

Having completed his sixth form, Goce Delčev found himself at

a crossroads: whether to continue at the grammar school and become a teacher

or to go on with his education in some military academy. He found the latter

more attractive, as

"to be an officer looks as if you were preparing to join

immediately the struggle for what the Macedonian people had the right to.

22. Boris Sarafov (village of Libjahovo, Nevrokop region,1872

- Sofia, 1907), Macedonian revolutionary. Participant in the 1895 Melnik

‘uprising’. President of the Supreme Macedonian Committee (VMK), Sofia.

Member of the General Staff of the Second Revolutionary District during the

Ilinden Uprising. At the Rila Congress of MRO (October 1905) he was given a

suspended death sentence. Sarafov was liquidated in 1907 by order of the Ser

(Serez) circle.

23. Hristo Čemkov (Štip, ? – Prilep, June 1899), Macedonian

revolutionary. Took his own life when his attempt to form a revolutionary

detachment was revealed

24. Atanas (Tane) Murdžev (Prilep, c. 1875 - ?). Macedonian

revolutionary. Very active in the Sabler grenade factory. Later went over to

the Vrhovists.

19

An officer, as it seemed to many young Macedonians at the

time, was almost an accomplished leader, who would head and lead forward his

armed units" (K. Hristov).

Delčev’s dilemma was finally resolved before the persuasive

recommendation of his acquaintances, Second Lieutenant Dimitar Žostov and

cadet (Junker) Dimitar Atanasov, about the Bulgarian Royal Military

Academy in Knjaževo (Sofia). Moreover, Goce Delčev knew that Boris Sarafov

was also there.

Thinking of the usefulness of a military education for those

who would lead the future revolutionary struggle, and known for his

inspiring words, Goce Delčev managed to convince four of his student

friends, members of the revolutionary circle, to embrace this idea.

Of course, the dutiful 19-year-old son Goce did not want to

go to Bulgaria without his father’s consent. Once again Nikola Delčev was

consulted, this time through the mediation of Goce Imov’s grandfather. This

was the last time that Goce Delčev asked for permission from his parents to

carry out his intentions. From this moment on he took his destiny into his

own hands.

In July 1891 a small group of five school-leavers front the

Salonika Grammar School (Goce Delčev, Stamat Stamatov from Debar, Ilija

Konduradžiev from Prilep, Goce Imov from Kukuš and Stefan Strezov from

Koprivštica) went to Sofia. Thus the entire Salonika Grammar School

revolutionary circle joined the military academy in Sofia.

Some fifty young Macedonians, among others, followed the

three-year course at the Royal Military Academy. Delčev’s group belonged to

the 13th Class. The previous, 12th, Class included the former Salonika

Grammar School students Boris Sarafov, Georgi Apostolov and Dimitar Atanasov,

who welcomed the arrival of Goce Delčev’s group.

This was the beginning of Goce Delčev’s first three-year stay

in the neighbouring Principality of Bulgaria.

3. By Act No. 192 of July 23, 1891, Goce Delčev

became a cadet (Junker) in the Royal Military Academy in Knjaževo,

Bulgaria. This was the start of the third and last stage of his education.

Goce Delčev’s three years of education (1891-1894) in the

Principality of Bulgaria took place at the time of Stefan Stambolov’s regime

(1887-1894). [25] Only the last few months of Delčev’s education coincided

with the first months of Dr Konstantin Stoilov’s new government (1894-1899).

[26]

25. Stefan Stambolov (1854-1895). Bulgarian statesman.

Bulgarian Prune Minister (1887-1894).

26. Dr Konstantin Stoilov (1853-1895). Bulgarian statesman.

Twice Bulgarian Prime Minister (June-August 1887; 1894-1899).

20

Goce Imov and Goce Delčev as Cadets

21

Stefan Stambolov’s dictatorial regime, supported by Prince

Ferdinand of Coburg (Ferdinand I of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha), [27] stifled the

freedom-loving demonstrations in the Bulgarian society. On the other hand,

the merciless bourgeois exploitation of the broad masses of the Bulgarian

people created a grim picture in the young Bulgarian state.

Of course, the Royal Military Academy could not remain

outside contemporary Bulgarian social trends. An austere regimental

discipline ruled there, accompanied by harsh military training. The aim was

to create royalist machines whose only ambition would be the epaulets of a

colonel or general. Hence any freedom-loving thought and action was

eradicated. And this was precisely what the freedom-loving Delčev’s spirit

could not tolerate. All his illusions connected with this academy were

suddenly shattered.

Goce Delčev expressed his profound disappointment with the

following words: "Why did I not stay in Salonika, why did I not complete the

grammar school course, why did I not become a teacher?" This was the first

and only open regret Delčev expressed during his education.

But there was no way back. Ambition on the one hand, and the

usefulness of the military education, on the other, did not allow him to

step aside. Even Ivan Hadži Nikolov’s [28] attractive offer in Boris’s

Garden (Sofia, July 1893) in the presence of Kosta Šahov — to go back to

Salonika and head the future revolutionary organization for the liberation

of Macedonia — did not sway Goce Delčev’s determination. On that occasion,

Ivan Hadži Nikolov presented the following projection:

"1. The Revolutionary Organization should be established

inside Macedonia and be active there so that the Greeks and Serbs would not

designate it an instrument of the Bulgarian government;

"2. The founders should be local inhabitants and live in

Macedonia;

"3. The political slogan of the Organization should be the

autonomy of Macedonia;

"4. The Organization should be secret and independent, not

maintaining links with the governments of the neighbouring free states; and

"5. Only moral and material support for the struggle of the

Macedonian revolutionaries should be sought from the Macedonian émigrés in

Bulgaria and Bulgarian society."

27. Ferdinand I of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (Vienna, 1861 – Coburg,

1948). Bulgarian ruler (Prince, 1887-1908. Emperor, 1908-1918). Abdicated in

1918 in favour of his son, Boris III.

28. Ivan Hadži Nikolov (Kukuš, 1861 – Sofia, 1934).

Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of MRO.

29. Košta Šahov (Ohrid, 1862 – 1916), Macedonian public

figure and journalist. Member of MMKD and the Loza movement.

22

Ivan Hadži Nikolov

Although Goce Delčev agreed in principle, he intended to

complete the military academy first and then start on the practical

realization of this idea. After the completion of the Military Academy

“I’ll be made an officer, I’ll resign from the officer’s

post. I’ll come to Salonika and we’ll form a revolutionary organization.

Having begun our work, we’ll earn authority and there will be no need to

look for another figure of authority."

But events took a swifter course and Delčev’s insistence on

completing his education prevented him from taking part as one of the

founders of the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (MRO).

23

Not ready himself to abandon the academy, Goce Delčev at

least tried to thwart other young Macedonians from enrolling there. It is

known that Goce Delčev strongly dissuaded his fellow townsman Petar Drvingov

[30] from doing this. Hence Stamat Stamatov assumes that

"even then the idea was ripe in Delčev that the intellectual

forces of Macedonia would be more useful in their native places rather than

in coming to Bulgaria".

Such ideas of Delčev’s were strengthened in particular by the

Macedonian Loza ("Vine”) Movement. Naturally, during the rare

occasions when he left the atmosphere of the drab barracks, Delčev joined

this progressive Macedonian circle. There he and Košta Šahov from Ohrid

became close friends.

It was a lucky event that the arrival of Goce Delčev in Sofia

coincided with the appearance of the Young Macedonian Literary Society. The

same intellectual forces which were later to establish or lead the

Macedonian Revolutionary Organization could be found within or around this

society.

The leading figures of the Young Macedonian Literary Society

included Košta Šahov, Petar Pop Arsov, Georgi Balasčev, Georgi Belov,

Kliment Karadžulev, Evtim Sprostranov, [31] Hristo Pop Kocev, Dimitar Mirčev,

Andrej Ljapčev, [32] Tomo Karajovov, [33] Angel Naumov, Naum Tufekčiev, [34]

Hristo Matov [35] and Ivan Hadži Nikolov.

In the beginning the society maintained close links with Dame

Gruev’s student Macedonian Society and later with Goce Delčev’s circle

active within the Sofia Military Academy.

In early 1892. the Lozars (members of the Movement)

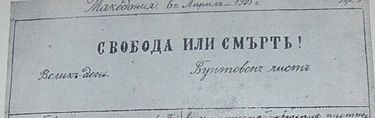

raised their voice against foreign propaganda through their Loza

journal, stressing the following:

"Only a strong resistance on our part can protect us from

ponderous encroachments. But in the present state of affairs we cannot

accomplish a similar feat; we need forces to do that, and our forces are

shattered and divided. Therefore we should unite, we should integrate them

into one

30. Petar Drvingov (Kukuš, 1875 - Sofia, 1958). Bulgarian

colonel of Macedonian descent.

31. Evtim Sprostranov (Ohrid, 1868 – Sofia, 1931), Macedonian

public figure. Member of the movement

32. Andrej Tasev Ljapčev (Resen, 1866 – Sofia, 1933),

Macedonian public figure. Member of MMKD. Went over to the Vrhovist ranks.

Later transformed into a Bulgarian statesman. Ljapčev became Bulgarian Prime

Minister (1926-1931). Publicly favoured Vančo Mihajlov.

33. Tomo Karajovov (Skopje, 1868 - 1951). Macedonian public

figure. Member of MMKD and journalist.

34. Naum Tufekčiev (Resen, ? – Sofia, 1919). Macedonian

public figure. Arms trader. Vice president of VMK. Killed in Sofia.

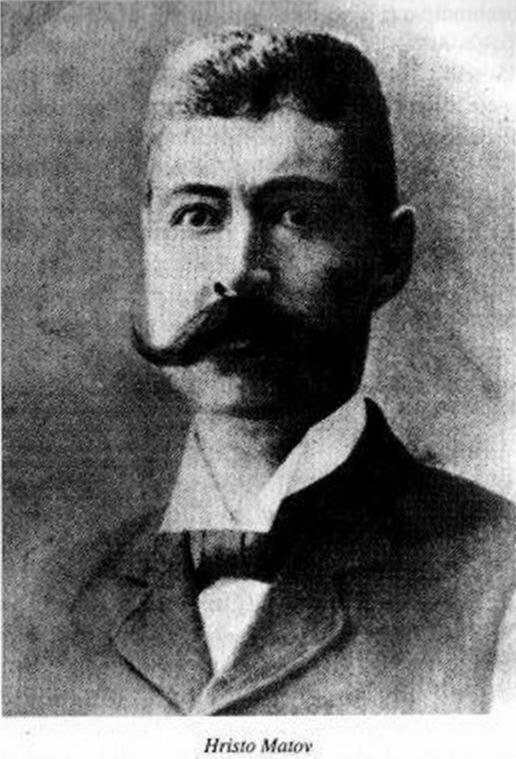

35. Hristo Matov (Struga, 1872 – Sofia, 1922). Macedonian

revolutionary. Member of MRO Central Committee. External representative of

MRO in Sofia following the Ilinden Uprising, ideational protagonist of the

conservative faction within the movement.

24

general powerful force — a popular force — if we want to

protect the future at our fatherland. This should be the aim of every

sensible Macedonian whoever he may be."

The Lozars tried to block the denationalization policy

of foreign church and education propaganda by putting forward their

strongest weapon – the language — through the choice of

"the Ohrid dialect, which will be the literary language of

the future Greater Macedonia",

to use the words of alarm of their open opponent Levov, [36]

a Greater-Bulgarian. Hence it was no wonder that Stambolov’s official

journal Svoboda, sounding a note of alarm, called them Macedonian

national "separatists", following which the Loza journal was banned

and the Lozars were persecuted.

In the Military Academy Goce Delčev withdrew into himself. He

was silent, modest and good-natured. He was a good student. He did not want

to expose himself too much on the professional military plane and maintained

a golden mean. By an order dated September 15, 1892, he passed into the

middle, and by an order of October 5, 1893, he entered the third and final

year of the Military Academy.

Here Goce Delčev became close to Minčev. Marin Peev was

another young man to join them. Several other cadets with open socialist

orientation gravitated around them. This group was designated as the

socialist circle. It is known that they ignored the strict academy ban on

reading newspapers, journals and books with a revolutionary content. Banned

revolutionary books circulated secretly among them, especially those of

socialist nature. Thus under Delčev’s

"pillow there were always works by Marx, Engels, Kautsky,

Shalgunov, Chernyshevsky, Dobrolyubov, Herzen" (V. Kocev).

Punishments did not prevent Delčev and his friends from

continuing this practice.

In June 1894, at the final year examinations, Goce Delčev

showed an average mark of 9.45 and his behaviour was assessed as excellent

12 (according to the 12-point system). So Delčev successfully completed his

education in the Royal Military Academy. After this he registered for

training in the 22nd Thracian Infantry Regiment in Tatar-Pazardžik. Only the

promotion of the cadets into their first rank as officers remained to be

carried out. And a scandal broke out precisely in connection with this.

In order to save money, Konstantin Stoilov’s new government

announced the postponement of the date for promoting the new class of

officers until January 1, 1895. This caused great indignation among the

cadets who had completed the academy. Two sharp anonymous letters arrived at

the addresses of the Minister of War and the head office of the Royal

Military Academy.

36. Levov, pseudonym of Lev Dramov.

25

This was interpreted as an attack on military discipline. In

order to discover and eradicate the culprits, three ‘suspicious’ cadets were

arrested (Vasil Minčev, Vladimir Kovačev and Marko Vankov), all close

friends of Delčev’s. Somewhat later Marin Peev was also arrested. Then Goce

Delčev unselfishly decided to take the blame on himself, declaring that he

had written the anonymous letters and that the arrested cadets were

innocent. He was not believed, but was arrested nevertheless, mostly owing

to his socialist orientation. Gospodin Željaskov was arrested together with

him.

In fact, the event with the anonymous letters was only a

pretext for settling accounts with these young people of a socialist

orientation. This is supported by the discovery during the 1896 manoeuvres

at Loveč that the author of the anonymous letters was one S.N., an officer

serving at Loveč.

The charge against Goce Delčev stated that he was not only "a

socialist but also that he spread such propaganda in the academy".

Order No. 107, paragraph 5 of October 6, 1894, of the Royal

Military Academy, by which the aforementioned six cadets were expelled, read

as follows:

"On the basis of the act of September 16. [old style,

author’s note] No. 133, the cadets of this academy, Vasil Minčev, Vladimir

Kovačev, Marko Vankov, Gospodin Željaskov, Georgi Delčev and Marin Peev, are

hereby expelled from this academy and transferred to army reserves as

privates. The first two have no right to re-enrolment and promotion to

officer’s rank, and the last four have the right to be re-admitted into

service, being responsible of writing an anonymous letter to the Minister of

War. Those who are allowed to be re-admitted into the army if they wish must

first join a military unit of their own choice, where they shall present

themselves for promotion to the rank of first officer."

The order was so rigorous that it insisted on "eradicating

the six men from the academy’s lists".

Peju K. Javorov [37] is categorical in maintaining that Goce

Delčev was expelled from the Royal Military Academy "as a socialist".

This turn of events did not disappoint Delčev; on the

contrary, it made him happier. He felt himself free as a bird. His

conscience was clear as he had been relieved of the constraints of the

training period with someone else’s help’. Broad revolutionary prospects now

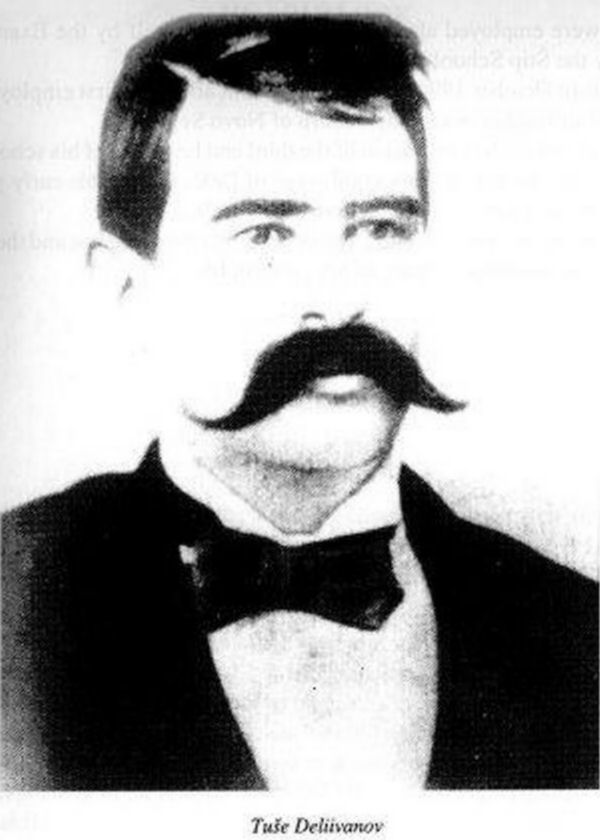

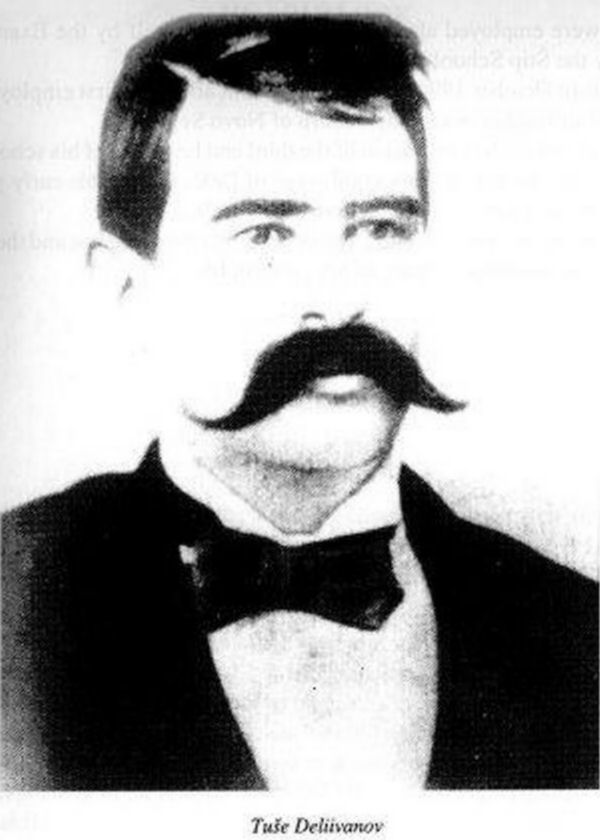

opened before him. It was then that Goce Delčev said to Tuše Deliivanov:

"Our slave-like position in Macedonia clearly sets out what I

should do... It is unforgivable for us, who have elevated ourselves

spiritually, to suffer, to endure any longer and wait for others to liberate

us."

37. Peju Kračolov Javorov (Čirpan, 1878 - 1914). Bulgarian

poet and journalist who participated in the Macedonian revolutionary

movement. Goce Delčev’s first biographer.

26

Tuše Deliivanov

At the time Goce Delčev still did not know of the already

established, strictly secret MRO. His companion in those "unpleasant" days

in Sofia. Tuže Deliivanov, [38] reveals Delčev’s intentions:

"He is to go to Macedonia and devote himself to revolutionary

activity, organizing the population for the struggle against the oppressors.

Here he could not find out anything definite about such activities in

Macedonia, nor did he meet anyone who could instruct him..."

The first step Goce Delčev made in this regard was to send an

application to the Exarchate for a teacher’s post in Macedonia. His fellow

townsman Deliivanov, encouraged by Delčev, did the same.

38. Tuše (Petar) Deliivanov (Kukuš, 1869 - 1950). Macedonian

revolutionary. External representative of MRO in the Bulgarian capital,

Sofia.

27

"After some ten days we were employed almost simultaneously:

myself by the Exarchate, and he by the Štip School Board," writes

Deliivanov.

Thus in October 1894 Goce Delčev learnt about his first

employment, in the post of teacher in the Štip suburb of Novo Selo.

This marked the conclusion of the third and last stage of his

schooling. This was also the end of the second stage of Delčev’s life, his

early youth, which covered his education in Salonika and Sofia.

Goce Delčev was now at the threshold of the third, the last

and the most significant, revolutionary stage of his eventful life.

28

III. OUTLOOK

At twenty-two years of age, having completed his general and

military education, before starting his activity for Macedonian national

liberation, Goce Delčev gave the impression of a mature person with a strong

character and a well-formed progressive outlook.

"Goce Delčev’s intellectual development passed through

several stages. In Kukuš he acquired his basic knowledge of the world and

people. In the Salonika Grammar School he made this more profound and

succeeded in penetrating the spheres of science, literature and socialism.

In the Military Academy the breadth of his interest in a number of questions

was already clear, especially in the area of various political and socialist

doctrines" (H. A. Poljanski).

Goce Delčev was fascinated by the ideas of the French

Enlightenment, the French Bourgeois Revolution, the American War of

Independence, the 1830 and 1848 Revolutions and the 1871 Paris Commune. He

was especially interested in the struggle for liberation, starting from the

American War of Independence, through the Carbonari, the Italian national

liberation movement and its ideologist Mazzini, to the revolutionary

concepts of the liberation struggle of the Balkan peoples (Serbs, Greeks,

Romanians, Bulgarians). Of course, he was best acquainted with the most

recent, the Bulgarian national liberation movement. This was largely a

result of his three-year stay in the young Bulgarian state. Goce Delčev not

only studied the literature on this question, especially Zaharij Stojanov’s

Notes... and his biography of Vasil Levski, but also had the

opportunity of making personal contacts with Bulgarian revolutionaries.

29

Delčev’s primary interest was directed towards the national

liberation struggle of the Macedonian people, especially at the time of the

Great Eastern Crisis: the Razlovci Uprising, the Macedonian (Kresna)

Uprising and the Demir-Hisar Plot. As a matter of fact, he was later to have

contacts with the leader and ideologist of the aforementioned two uprisings

(Razlovci and Kresna), Dimitar Pop Georgiev Berovski, [39] having the

opportunity of hearing first-hand information on these glorious events in

Macedonian history.

Delčev was undoubtedly well acquainted with the major

demonstrations of the Macedonian national cause at the time. He was

personally close to the Lozars and the Macedonian Socialist Group in

Sofia. He was also very well acquainted with the biographies of Washington,

Lafayette, Mazzini, Garibaldi, Kostyushko, Dombrowski, Kossuth, Rakovski,

Karavelov, Botev and Levski, which widened his revolutionary vision.

Of course, in the overall building of his revolutionary

profile. Delčev’s activity in the Salonika and Sofia circles as well as his

close links with the Lozars and the socialists in Sofia w ere of

considerable significance. In this respect, his friendship with Košta Šahov

was extremely useful.

Goce Delčev was almost equally attracted to the natural and

social sciences. His interest ranged from mathematics and biology to history

and philosophy.

He came into contact with a large number of doctrines. The

scope of Delčev’s knowledge ranged from Darwin’s theory to Marx. He was

particularly fond of the ideas of the Russian revolutionary democrats

Dobrolyubov, Chernyshevsky, Herzen and Pisarev.

"He was also influenced by various revolutionary,

utopian-socialist, utopian-communist and anarchist ideas, in particular

those of Blanqui, P. Kropotkin, Mikhail Bakunin and S. Mikhailovich

Kravchinsky-Stepnyak."

Hence he was close to the movement of Spiro Gulapčev [40]

from Lerin.

Delčev’s ideological views acquired a socialist character

after he became acquainted with the work of Dimitar Blagoev [41] from

Zagoričani. This was also a result of his contacts with Vasil Glavinov’s

[42] Macedonian Workers’ Socialist Group,

39. Dimitar Pop Georgiev Berovski (Berovo, 1841 - village of

Dolna Grašnica, Ḱustendil region, 1907), Macedonian revolutionary. Leader

and ideologist of the Razlovci Uprising (1876) and the Kresna (Macedonian)

Uprising (1878 - 1879).

40. Spiro Gulapčev (Lerin, 1856 - 1918). Macedonian

journalist and public figure. Founder of the Siromahomilist movement

(movement for the protection of the poor) in Bulgaria.

41. Dimitar Blagoev-Dedoto (village of Zagoričani, Kostur

region, 1856 – Sofia, 1924), founder of the socialist movement in Bulgaria.

42. Vasil Glavinov (Veles, 1869 – Sofia, 1929), founder of

the Macedonian Socialist Group in Sofia (1893).

30

and particularly of his inseparable friendship with Dimo

Hadži Dimov. [43] On the other hand, it was thanks to Spiro Gulapčev’s

publications that he became acquainted with the creators of Marxism — Marx

and Engels — via some of their works.

Surrounded by the aforementioned Macedonians, outstanding

propagators of socialist ideas, and drawn by his intellectual inclinations,

Goce Delčev delved into the doctrine of socialism. A piece of public

information m this respect appeared in the Sofia Socialist newspaper

(October 4, 1894, old style):

"Six students who share socialist ideas have been expelled

from the military academy, under the pretext that they have written some

anonymous letter to the Minister of War. In fact, the aim is that the

despots over poverty get rid of the socialist infection’, which is dangerous

for them."

Here is Goce Delčev’s personal view of the socialists:

"These people carry out a real revolutionary task by

spreading socialist literature so that socialist ideas may penetrate our

ranks. They may play a revitalizing role, not a damaging one."

Yet Delčev’s inclination towards their ideas was mostly of a

declarative character. He was. above all, a classical national

revolutionary. Thus, according to Stamat Stamatov, Goce Delčev

“knew perfectly well that Macedonia would be liberated

neither by the theory of Darwin nor that of Marx".

Here is Hristo Andonov Poljanski’s [44] interpretation in

this regard:

"Delčev was aware that the concrete situation of Macedonia at

the time did not allow a stereotyped application of scholarly views and

revolutionary ideas which did not correspond to the concrete and specific

conditions prevailing in the Macedonia of that period. As a result, he acted

as a typical revolutionary democrat and tribune who. owing to the specific

objective conditions and circumstances, had brought the national liberation

revolutionary idea to the foreground. It was of an obvious and preeminent

significance before all other things."

It was this Goce Delčev, with his progressive ideological

views and military training capital, who found himself in front of the newly

opened transcendental doors of Macedonian history.

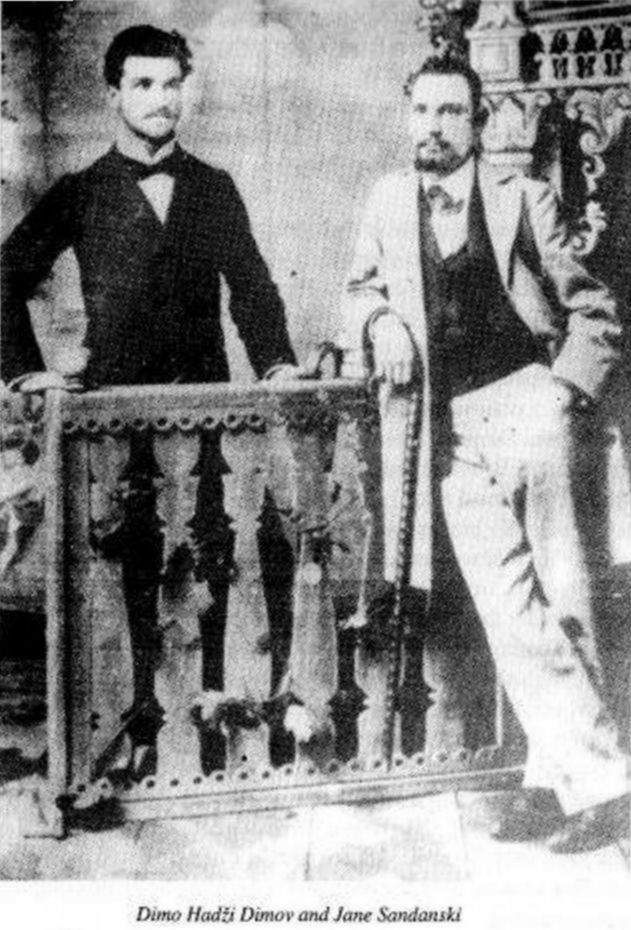

43. Dimo Hadži Dimov (village of GornoBrodi, Ser region, 1875

– Sofia, 1924). Macedonian revolutionary, journalist and visionary.

Liquidated in Sofia.

44. Hristo Andonov Poljanski (Dojran, 1927 – Skopje, 1985).

Macedonian historiographer. Rector of the Ss Cyril and Methodius University,

Skopje (1984-85). Author of a six-volume publication on Goce Delčev (1972).

31

IV. STORMY YEARS

The establishment of the Macedonian Revolutionary

Organization (MRO) opened a new chapter in more recent Macedonian history.

The agens movens in the foundation of MRO was the young Macedonian

intelligentsia. The chief proponent of MRO’s establishment was Dame Gruev.

The idea of the establishment of a revolutionary organization

became the basic preoccupation of a number of Macedonian intellectuals,

among whom Pere Tošev, Ivan Hadži Nikolov and Dame Gruev deserve a special

mention for their efforts.

Dame Gruev belonged to the group of Macedonian intellectuals

that grew up fast thanks, above all, to his painful schooling odyssey in

Salonika, Belgrade and Sofia, experiencing most directly the harsh

denationalization approach of the Bulgarian and Serbian propaganda machines.

Dame Gruev embraced the idea of the establishment of a revolutionary

organization in Macedonia as early as 1891. He believed that the emphasis on

its liberation component would be the best way of blocking foreign

propaganda, especially Serbian,

"before Serbian propaganda becomes strong enough and succeeds

in dividing the people".

The aforementioned student Macedonian Society was Dame

Gruev’s first more serious step in this direction. The ideas and intentions

of this Macedonian student society were interrupted after the murder of

Minister Belčev and Dame Gruev’s arrest in Sofia. Somewhat later, this

Society, although without Dame Gruev, became the meeting-place of the

Lozars.

In the summer of 1891 Dame Gruev made a new attempt at

revolutionary organization in Bitola by establishing a ‘Teacher’s Union’

with "a purely revolutionary goal".

32

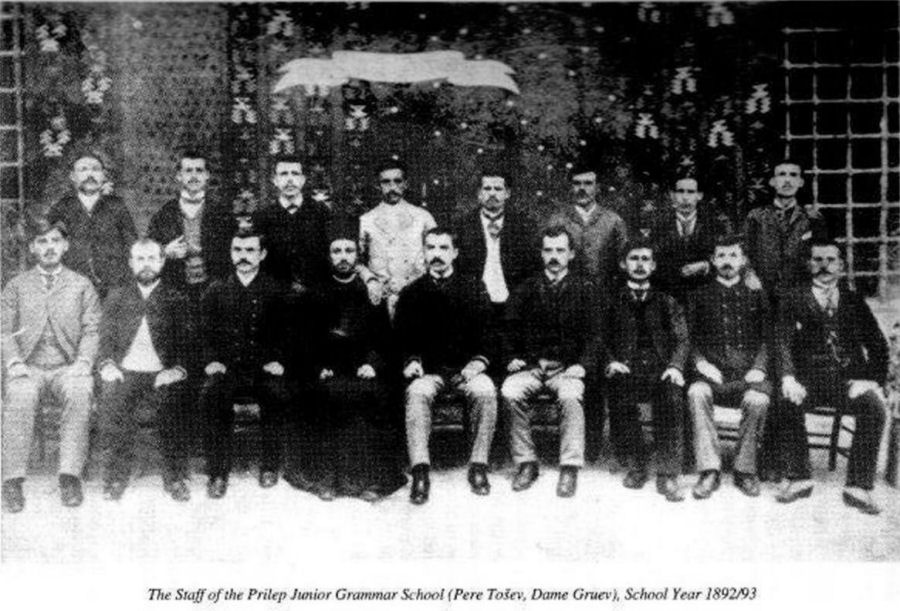

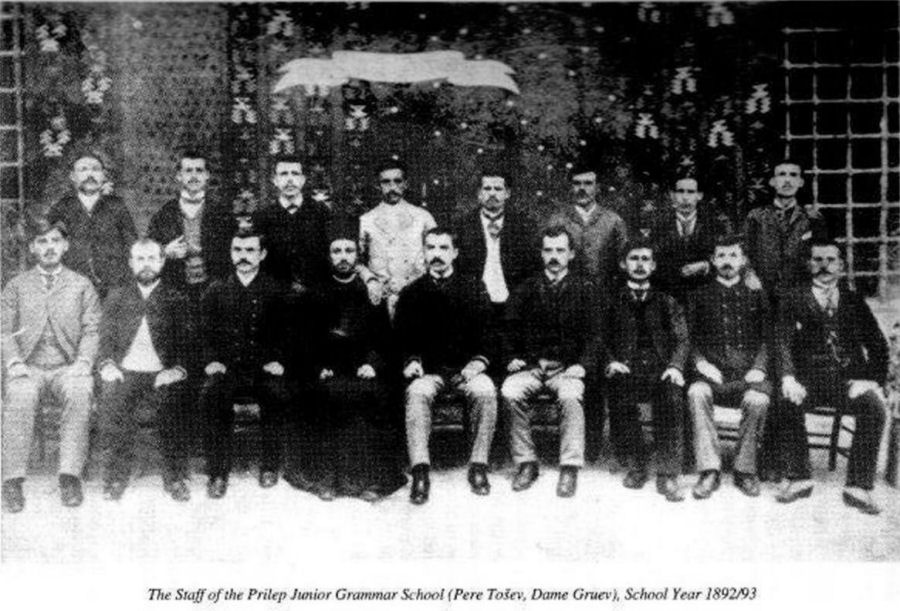

The Staff of the Prilep Junior Grammar School (Pere Tošev,

Dame Gruev), School Year 1892/93

33

But this attempt of Gruev’s failed because of Archimandrite

Kozma Prečistanski,’ an instrument of the Exarchate, the current president

of the Exarchal Church-School Community in Bitola.

The harsh Exarchal centralist and denationalization church

and educational policy in Macedonia was largely responsible for the cohesion

at the beginning of the last decade of the 19th century of Macedonian young

people and the middle class. primarily among craftsmen and the

intelligentsia, turning isolated instances of anti-Exarchist resistance into

a broad anti-Exarchist movement which opposed the Exarchate’s control over

the Macedonian church-school communities and its Greater-Bulgarian

orientation. The following question arose as an imperative of the time:

"Until when are we to be foster children? Are we not going to

stand on our feet again one day? Or should we perhaps continue to crawl?"

The arrival of Stambolov’s exponent Lazarov [46] at the head

of the Exarchate’s School Department in 1892 and his unscrupulous

aggressiveness in implementing the denationalization policy in Macedonia

contributed even further to the growth of the already tense anti-Exarchist

mood of progressive Macedonian circles. The anger of the Exarchate was to be

most felt by the Macedonian progressive intelligentsia which was financially

dependent on Exarchal donors who had come with money "to create Bulgarians

in Macedonia". The famed Macedonophobe Vasil K’nčov [47] openly declared

that he had come "to Bulgarize Macedonia".

Criticizing this shortsighted policy of the Exarchate

somewhat later, in 1894, Petar Pop Arsov said:

"The Exarchate gives money but buys wind, for ethnicity

cannot be bought with money!"

The penetration of Bulgarian teachers into Exarchal schools

in Macedonia, despite the existing overproduction of native Macedonian

teachers, the discrimination, harassment and expulsion of Macedonian

progressive ‘separatist’ teachers (e.g. Dimitar Conev, Ivan Hadži Nikolov,

Georgi Balasčev), the use of the Bulgarian language in Exarchal schools and

the incorporation of Macedonian church-school communities within the

Exarchal system were the main motives for the growing discontent of the

awakened Macedonian middle class and intellectuals whose edge was directed

against the Exarchist denationalization and

45. Kozma Prečistanski (village of Ortanci, Kičevo region, c.

1835 - 1916), church prelate of the Bulgarian Exarchate. Earlier prior of

the Kičevo monastery of the Holy Immaculate (Sveta Prečista), later

archimandrite and finally (after 1897) the Exarchate’s Metropolitan of the

Debar - Kičevo region.

46. Nikola Lazarov, head of the School department of the

Bulgarian Exarchate in Constantinople.

47. Vasil K’nčov (Vraca, 1862 – Sofia, 1902), Bulgarian

educator, scholar, public figure and politician. Victim of an assassination.

Killed as Bulgarian Minister of Education.

34

Greater-Bulgarian encroachment on the independent development

of the Macedonian society. Hence Petar Pop Arsov said:

"They give us money to destroy us... To the devil with such

money; they are not only destroying our communities, but they do not believe

us either and appoint all kinds of presidents, clergymen, managers,

teachers, etc., so that they can control (?!) the sums the sole motive of

Bulgarian propaganda... Yes, Bulgarian propaganda!"

The anti-Exarchist movement in Macedonia brought about a

growing revolutionary feeling among Macedonian middle class circles. Ǵorče

Petrov was right to interpret that movement

"simply as a reaction against the long standing aspirations

of the Exarchate to gather into its own hands the control of social life,

and besides, I consider it the first step towards independent activity in

the country. It imperceptibly grew into a revolutionary movement."

Thus, while the former attempts at revolutionary organization

ended at best as revolutionary aspirations, at the time when the necessary

conditions were created, in 1893, the efforts were crowned with the

establishment of the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. The principal

merit for its formation goes to Dame Gruev.

Dame Gruev’s return to Salonika in the summer of 1893 was

certainly of crucial significance. He became employed as a proofreader in

the printing shop of Kone Samardžiev. [48] a book seller and outstanding

example of the Macedonian conservative pro-Exarchal bourgeoisie. As a matter

of fact, Dame Gruev replaced Nikola Naumov.

Ivan Hadži Nikolov, fascinated by the idea of liberation

since his early youth, around 1892 became convinced that

"only a secret revolutionary organization will block the way

to foreign propaganda in Macedonia",

because the aspirations were for

"Serbia [to become] — a Balkan Piedmont and Bulgaria — a

Balkan Prussia".

With this in mind, in 1892 he probed the following

progressive Macedonian intellectuals in Salonika: Petar Pop Arsov, Hristo

Tatarčev, Dimitar Conev and Hristo Batandžiev. [49] But the fact that they

were few in number discouraged them from taking practical steps m this

regard. In search of an authoritative person, in July 1892 Ivan Hadži

Nikolov went to Sofia. It was on this occasion that his aforementioned

meeting with Goce Delčev in Boris’s Garden, through Kosta Šahov’s mediation,

took place. Goce Delčev accepted his idea in principle, but he preferred

48. Kone Samardžiev (Prilep, 1854 – Salonika, 1912),

Macedonian bookseller and publisher. Prominent Exarchist activist.

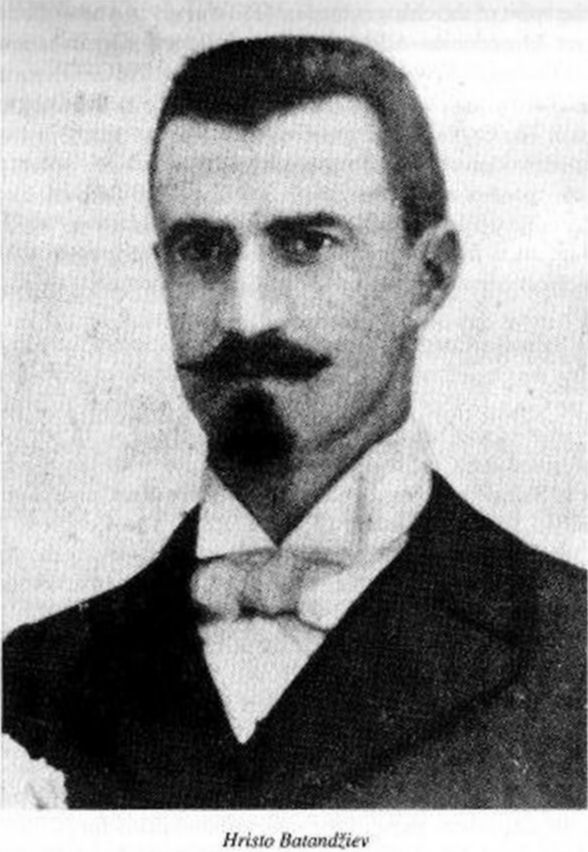

49. Hristo Batandžiev (Gumendže, Enidže-Vardar region, ? -

1913), Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of MRO. Resigned from MRO

Central Committee in 1899. Liquidated by the Greeks.

35

to complete his education in the Royal Military Academy

first. As a result, this attempt of Ivan Hadži Nikolov’s failed.

Dame Gruev, however, was not of the same opinion. He believed

that the conditions for the establishment of a revolutionary organization

were ripe. His optimistic prognosis was based on the extremely difficult

social and economic position of the Macedonian people, on the growing

denationalization activity of the propaganda machines, on the fervent

anti-Exarchist struggle, in particular on the strained atmosphere created by

Lazarov as the head of the School Department of the Bulgarian Exarchate

(1892), on the return of the Lozars to Salonika (1892), on the

Exarchate’s transference or sacking of several progressive Macedonian

teachers from the Ss Cyril and Methodius Boys’ Exarchal Grammar School in

Salonika, on the appointment of the former Bulgarian minister Mihail Sarafov

[50] as the principal of the Salonika Boys’ Exarchal Grammar School (school

year 1893/94), as well as on the appointment of the pronounced Bulgarian

Macedonophobe Vasil K’nčov as the chief inspector of the Exarchal schools in

European Turkey (1893). Dame Gruev simply felt the pulse of the time; it

proved that his persistence was not a vain effort.

Dame Gruev first joined the circle of the progressive

Macedonian teachers’ intelligentsia in Salonika. He came into contact with

his old friend Petar Pop Arsov who shared the same ideas and from whom he

had probably heard about Ivan Hadži Nikolov’s unfulfilled plans. Goce

Delčev’s name is likely to have been mentioned on that occasion. Dame Gruev

also became close to Andon Dimitrov, [51] a teacher of Turkish in the Ss

Cyril and Methodius Boys’ Exarchal Grammar School in Salonika. In August

1893 Dame Gruev met Hristo Tatarčev, [52] an Exarchal school doctor in

Salonika, for the first time. There is no doubt that he was impressed by

Tatarčev as a person, and talked to him concerning the organization of

future revolutionary activity.

On November 2, 1893, walking on the Salonika coast, Dame

Gruev and Andon Dimitrov met Ivan Hadži Nikolov. There they finally agreed

to hold a joint meeting.

The founding meeting took place on Saturday evening, November

4, 1893, in Hristo Batandžiev’s home in Salonika. On that occasion, the six

MRO leaders — Dr Hristo Tatarčev, Ivan Hadži Nikolov, Petar Pop Arsov,

50. Mihail Sarafov (1854-1924). Bulgarian public figure,

politician and diplomat.

51. Andon Dimitrov (village of Ajvatovo, Salonika region,

1868 - 1933). Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of MRO.

52. Hristo Tatarčev-Doktorot (Resen, 1869 – Turin, 1952).

Macedonian revolutionary. Coryphaeus of MRO. First president of the Central

Committee of MRO. Later, MRO’s external representative in Sofia.

36

Dr Hristo Tatarčev

Hristo Batandžiev, Andon Dimitrov and Dame Gruev - exchanged

ideas concerning the physiognomy and goals of the Revolutionary

Organization. The discussion covered a broad spectrum of issues ranging from

the struggle for the implementation of Article 23 of the Treaty of Berlin to

Ivan Hadži Nikolov’s already crystallized idea.

According to Hristo Tatarčev, the group was constituted as an

association without a written protocol and without electing a head such as a

president.

"At the meeting there were no formalities, vows or anything

similar so that the members could feel themselves bound to act for the

cause."

Yet the very fact that the group was constituted confirms the

founding character of its first meeting.

The second meeting, held in early January 1894, dealt with

the concrete establishment of MRO. Petar Pop Arsov was then given two

assignments:

37

(a) to prepare a Draft Statute of the Organization, and (b)

"to write a booklet entitled Stambolovism in Macedonia". Ivan Hadži

Nikolov’s proposal was accepted stating that

"Those who have chosen the Exarchate’s centralist policy

should be considered unsuitable, and those in favour of decentralization of

the church-school cause in Macedonia should be considered suitable... and

[as such, author’s note] should devote themselves to the revolutionary

idea".

This itself confirms how true was Ǵorče Petrov’s view that

the anti-Exarchist movement in Macedonia "imperceptibly grew into a

revolutionary movement". Once MRO was formed, it made its first steps

chiefly as an antipode to the Exarchate and its harsh centralist and

denationalization policy in Macedonia.

It is very likely that the Adrianople region was not part of

the plans of the chief MRO actors at the first two meetings.

It is rather difficult to follow MRO’s founding organization

in connection with its character, goals, name, the time and manner of

adoption of its first legal acts (Statute and Regulations) owing to the

different accounts of its protagonists, but primarily owing to the lack of

original protocol documentation. The only certain thing is that all of them

had "the principle of autonomy" in mind.

Of course, all dilemmas around the organizing principles,

character and goals of the Organization arising from the different accounts

of its founders were dispersed after the adoption of its legal acts — the

Statute (‘Constitution’) and the Regulations.

The Draft Statute prepared by Petar Pop Arsov was based on

the Statute of the Bulgarian Central Revolutionary Committee published in

Zaharij Stojanov’s [53] famous Notes...

The Statute was adopted at one of the subsequent sessions of

the six founders of the Organization. It is difficult to establish whether

the Statute was adopted without corrections, or with considerable

modifications, as can be concluded from Dame Gruev’s words:

"We grouped ourselves and we worked out a Draft Statute

together."

The Organization’s first statute was of a narrow,

nationalistic character, which was certainly the result of the ideological

intolerance, external influences and inexperience of its authors at the

time.

MRO Statute contained 14 articles divided into four chapters

covering the goal, composition and structure, as well as the financial

support and penalties of the Organization.

According to Article 1, the goal of the Organization was the

attainment of the "full political autonomy of Macedonia and the Adrianople

region",

53. Zaharij Stojanov (1850-1889). Bulgarian revolutionary and

statesman

38

Petar Pop Arsov

winch was a significant step forward with regard to Article

23 of the Treaty of Berlin. For the attainment of this goat, according to

Article 2, the Organization was bound to awaken "awareness for the

self-protection" of the population, to spread among them, in the press or

orally, revolutionary ideas and to prepare and incite a general uprising.

The organization was based on the centralist principle.

According to the Statute, it consisted of a Central Committee as well as

district, subdistrict and village committees (Article 5).

The conspiratorial character of the Organization was

reflected in Article 4 of its Statute:

"The members of each committee shall be divided into groups

led by a head appointed by the director.

39

Each member of the group, as well as the head, shall receive

a number given by the responsible committee. Each activist shah know only

the members of his group and the head, and the tatter shall know only the

director of the committee or the mediator."

In fact the groups were the basic cells of the Organization.

A managing body stood at the head of each particular local

committee. The managing bodies of the district committees were appointed by

the Central Committee (CC), those of the subdistrict committees were

proposed by the district committees and appointed by the Central Committee,

and the village committees were appointed by the subdistrict committees

(Article 6).

The final Article, 14 of the Statute, set forth the

following: "Detailed internal Regulations have been worked out on the basis

of this Statute." This was certainly an anticipation, as the Regulations

were prepared later.

The first Central Committee was constituted at the same

session as that at which the Statute was adopted. It was headed by Dr Hristo

Tatarčev as president and Dame Gruev as secretary and treasurer.

The Regulations contained 50 articles grouped into 11

chapters. They set forth the statutory (‘constitutional’) norms in detail.

The Regulations contained the following chapters: I. Composition. Structure

and Duties of Revolutionary Committees; II. Duties of the Managing Bodies of

Local Revolutionary Committees; III. Duties of the Members of Managing

Bodies; IV. Duties of the Heads of Groups; V. Duties of the Worker Members;

VI. Correspondence; VII. Secret Mail; VIII. Secret Police; IX. Penalties; X.

Armament, and XI. Financial Means of the Committee.

The Central Committee and the managing bodies of the local

revolutionary committees were composed of a president, secretary, treasurer

and several advisors (Article 1). Membership of the Central Committee was by

election. They were to be elected once a year with a majority of votes by

the directors of the district committees or their proxies.

The duties of the Central Committee members are specified in

Article 4. Of special interest is Item 5 of Article 4 which reads as

follows:

"It [the Central Committee, author’s note] shall direct the

contacts with external MRCs [Macedonian Revolutionary Committees, author’s

note] if there are any, and in agreement with them and the district internal

committees it shall proclaim the day of the uprising, it shall adopt the

plan of action and direct the movement directly or through a special

commission composed by it in agreement with the external committees."

This clause shows the extent to which the authors of the

Regulations, while the Organization was still taking its initial steps,

cherished illusions of external help, their eyes mainly turned towards the

Macedonian émigrés in Bulgaria. Hence they made the rank of possible

external Macedonian committees equal with that of internal district

committees,

40

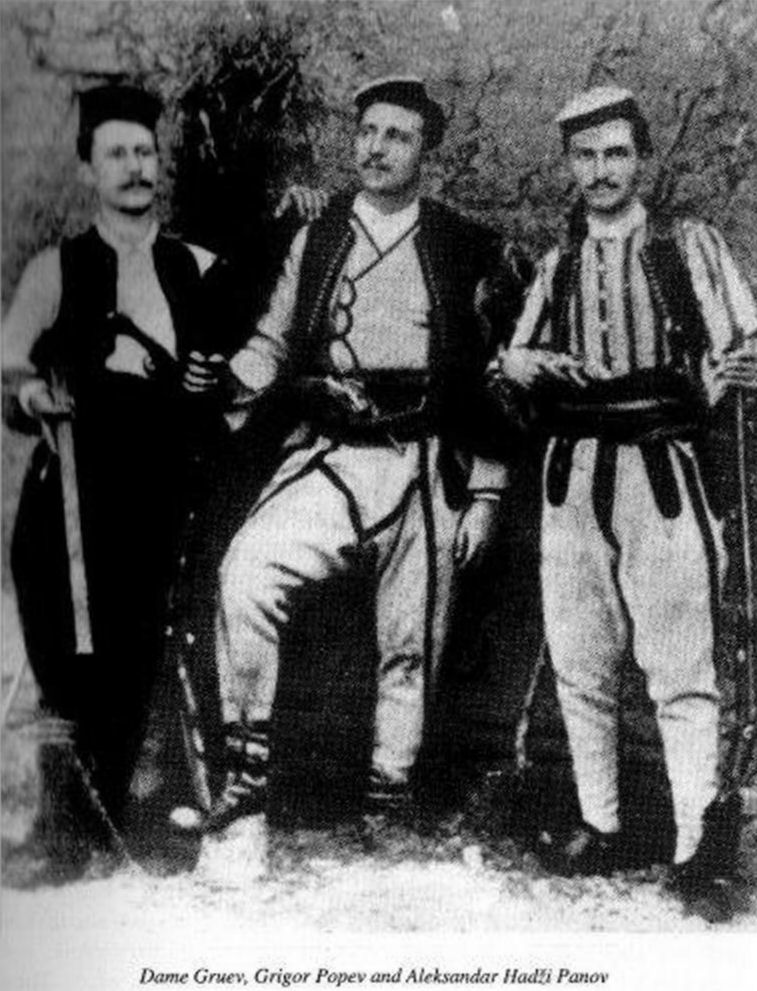

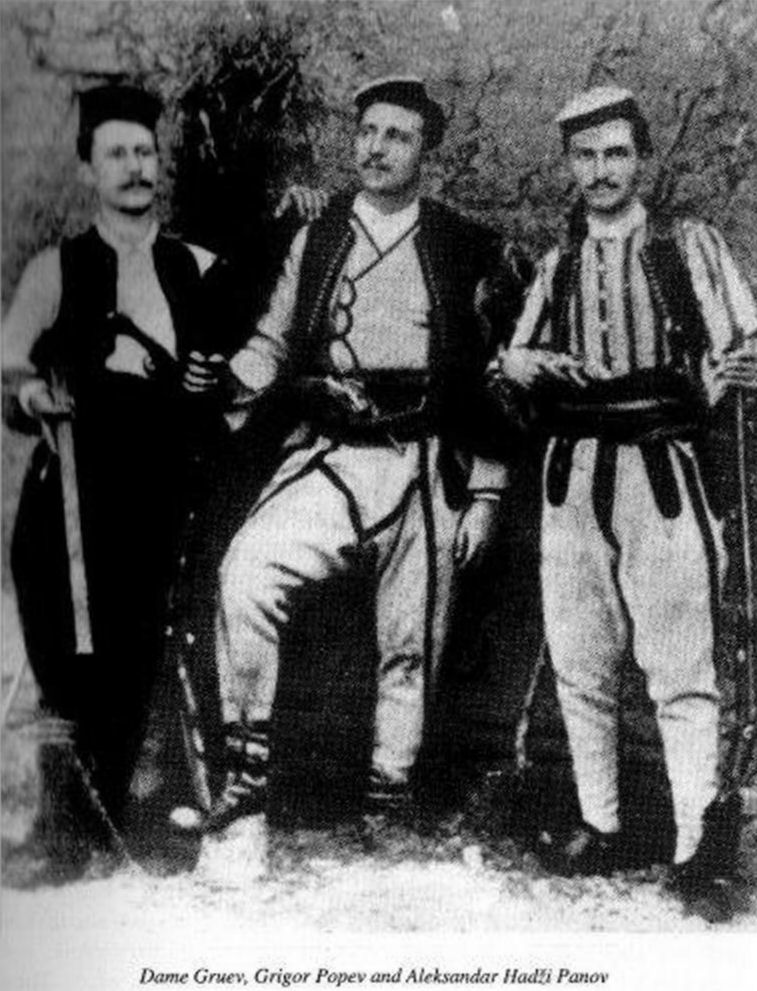

Dame Gruev, Grigor Popev and Aleksandar Hadži Panov

retaining, however, the right of the Central Committee as the

principal factor and coordinator of the future uprising.

District committees made contact with the Central Committee

directly, and subdistrict committees indirectly, via the district ones. They

were obliged, at the end of each month, to submit a report to the Central

Committee on their work and the situation in their territory.

"At the end of each year they shat! submit a detailed report

relating to:

41

"1. How many comrades/workers for freedom they have in any

specific town and village, and how many of them are capable of fighting

against the enemy with arms in their hands;

"2. The quantity of arms they have and the quantity they

need;

"3. The quality and activity of the secret police;

"4. The organization and activity of the postal service;

"5. The financial situation;

"6. The spirit of the members and opponents: and

"7. Existing Turkish armed forces: army, zaptiehs,

bashibazouks, etc."

The groups were the main cells of the Organization, and their

heads were the basic guidance staff. In accordance with Article 13,

"the heads of the groups shall be bound:

"1. To forward tasks given by the president or mediator to

their subordinates;

"2. To notify, once a week, the president or mediator of the

position of the groups in all respects: discipline, weapons, etc.;

"3. To care for and maintain in order the weapons of the

fighters;

"4. To gather their subordinates regularly once a week with

the purpose of instruction, and extraordinarily, whenever it shall be deemed

necessary; also to distribute and read revolutionary books, and to

strengthen in various ways their revolutionary spirit in general;

"5. To collect monthly fees and voluntary assistance from

their subordinates and hand them over to the president or mediator."

The reception of new members into the Organization was made

conditional on the "recommendation of an older member or the permission of

the president" (Article 14).

The insufficient strength of the Organization was compensated

for by a strong conspiratorial cloak. Thus, in accordance with Article 18.

"each member shall know only the comrades and the head of his

group... The workers should be sober, honest, reticent and incorruptible;

they should not drink nor should they talk to anyone about the revolutionary

cause, not excluding the closest friends, closest family members and

relatives. They should not have a threatening comportment towards anyone and

should systematically avoid anything that may arouse suspicion among the

people that they are members of the committee. Singing of rebellious songs

and outbursts of patriotic feelings are forbidden to the workers, not only

in front of people undecided as regards the cause, but also in front of

comrades in the cause."

The Organization attached great importance to discipline.

Hence, in accordance with Article 19,

42

Goce Delčev

43

"no worker under any pretext can refuse unpublished any duty

imposed upon him by his superiors, be it easy or difficult, in the place or

outside it."

The centralist structure of the Organization is also seen in

Article 26:

"All those workers who criticize and attack their superiors,

the managing body or the Cause in genera) shat) be considered renegades of

the Cause."

The Organization had its own secret police. In accordance

with Article 34. "each committee has its own secret police which consists of

two departments: investigative and punitive..."

As far as arms were concerned, "each member should be

provided with a rifle and also, wherever possible, with a revolver and

dagger..."

With regard to finance, the committees were obliged to

contribute one-third of the money collected into the treasury of the Central

Committee (Article 50).

The statutory norms established in this way opened good

prospects for the powerful structuring of the future organizational network.

The establishment of MRO was a crucial event in the more recent history of

the Macedonian people. It marked the beginning of a new, highly significant

period in the painful past of Macedonia.

The Macedonian Revolutionary Organization became an

avant-garde force of the Macedonian national liberation movement, which

entered a new, higher stage of development. Therefore the establishment of

MRO was a historic turning point for the Macedonian people.

At the outset the spread of MRO took place gradually,

cautiously and slowly, but safely and with no disturbances. The

revolutionary centre of the young MRO was located in Salonika, the city from

which its revolutionary ideas spread radially.

The Resen Conference (August 27-29.1894) marked the beginning

of a new stage in MRO’s development.

This Conference was initiated by the Central Committee of MRO

as a result of the growing need to exchange ideas with activists in the

field in order to surmount the initial weaknesses of the Organization, find

new elements of organizational activity and adopt the most adequate

solutions for further building, strengthening and expansion of the

Organization’s network.

At first glance, the Resen Conference may seem to have been

of a regional character, but its decisions exceeded the regional framework

and applied to MRO as a whole.

The Resen Conference, as the first conference of MRO, gave a

strong impetus to the Organization’s further activity towards the spread and

organizational reinforcement of the Macedonian liberation movement.

44

Following this Conference, new, fresh forces joined the

Macedonian national liberation movement, such as Pere Tošev, Goce Delčev and

Ǵorče Petrov, who introduced new meaning and vigour into MRO’s expansion

and development.

There is no doubt that Goce Delčev, alongside Ǵorče Petrov,

came at the head of the new revolutionary forces which had outgrown the

ideological views of MRO’s founders, reinvigorating and expanding their

ideological horizons by creating a new, more democratic concept for the

development of the Macedonian liberation struggle.

IV/1

1. An event of particular importance in the

history of the Macedonian national liberation movement is Goce Delčev’s

joining of the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

This marked the third, the last and the most successful,

revolutionary stage (1894-1903) of Delčev’s short life. It included two

sub-stages. The first covered Delčev’s legal activity as a teacher in Štip

and Bansko (November 1894 — November 1896), and the second, entirely

dedicated to the revolutionary cause, lasted until the end of his life

(December 1896 — May 1, 1903).

A historic meeting between Goce Delčev and Dame Gruev took

place in Štip in early November 1894.

Having arrived in Štip, Goce Delčev and Tuše Deliivanov were

welcomed by Dame Gruev, who worked as a teacher in Štip at the time. Gruev

had met Deliivanov before, but this was his first personal contact with

Delčev. Goce Delčev’s name, however, was not unknown to him. He had probably

heard of him in Salonika in the autumn of 1893, during the probing for MRO’s

foundation. He must have been informed at the time that Kosta Šahov had a

high opinion of Goce Delčev. Hence Gruev’s welcome was not accidental, and

even less accidental was his effort to discourage guests from visiting the

lodgings in which they stayed — in the house of the old village teacher Mite

Terancaliev — where Gruev himself used to live during his stay in Štip.

That same evening, at Dame Gruev’s provocative question as to

why he had left Bulgaria, Delčev answered fervently:

"Can there be any other place for a Macedonian than

Macedonia? Is there a people more unlucky than the Macedonians? And is there

a broader field for work other than Macedonia?"

45

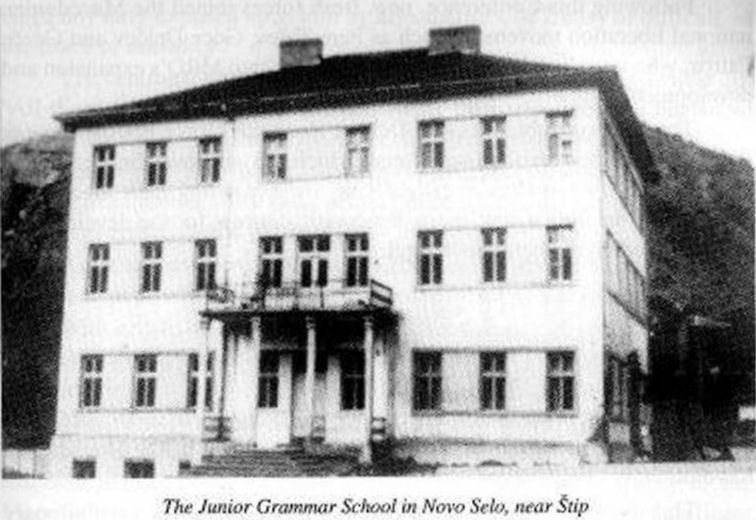

The Junior Grammar School in Novo Selo, near Štip

Delighted by Delčev’s liberation concept, Gruev opened his

heart wide with the words: "May you be welcome!", presenting him the

Constitution of the young MRO. The following day Goce Delčev took an oath

before the first man of the Organization, becoming a full member of MRO.

From this first contact between Delčev and Gruev, on the

threshold of Goce Delčev’s revolutionary activity, up to their last, which

took place in dramatic circumstances, nearly a decade later — at the end of

Delčev’s brilliant organizational work, on the eve of his tragic death — a

rare closeness and profound respect characterized their relations.

Delčev’s legal teaching activity in the two-form Novo Selo

Junior Grammar School was at a highly competent level. He taught four

subjects in the second form: Geometry, Natural History, Geography and

French. He was a strict and just teacher.

Delčev paid special attention to the training of adults. In

the evening and Sunday schools, together with his colleagues (Gruev,

Deliivanov, etc.) Goce Delčev covered important subjects from European and

American history, but above all from the history of the Balkans, managing to

encourage a revolutionary atmosphere in the town of Štip.

With his activity as a teacher, Goce Delčev intelligently

camouflaged his real revolutionary activity before the local Ottoman

authorities. His teaching was an excellent screen for the unobstructed

expansion and strengthening of the Organization’s network.

46

The young Goce Delčev proved an unrelenting agitator and

organizer. Dame Gruev was impressed:

"Delčev has immediately made an impression on me with his

openness and honesty. He was, in his first attempts at becoming a member,

even too open, so we had to restrain him to prevent him giving away our

weaknesses, the weaknesses of the Organization. He always tended to tell the

truth, believing that everyone should adopt the idea in the way he had

adopted it. He was very nimble."

Goce Delčev’s radius of activity covered only Novo Selo and

the surrounding villages, but his aspirations were much greater. Here are

the recollections of his colleague Tuše Deliivanov:

"Each Saturday evening he disappeared from Štip, sometimes

disguised, sometimes not, and returned on Sunday evening or Monday morning.

In two month’s time he had compacted his work and one night, sometime about

Epiphany, he complacently and smilingly said that we could even send

caravans to Bulgaria, and from Bulgaria to as far as Radoviš and Strumica."

Dame Gruev was a witness, in Štip, of Goce Delčev’s historic

role in the spread of the movement, reflected above all in the incorporation

of the rural areas into MRO and in the organization of MRO’s important

channel on the Macedonia-Bulgaria route. Motivated by Delčev’s tremendous

enthusiasm and vigour, in the school year 1894/95, together with Todor

Lazarov and TuŠe Deliivanov, and independently of Delčev, Dame Gruev

organized new people in the town of Štip and its surroundings.

"The whole town and Novo Selo were enveloped by revolutionary

fever,"

points Deliivanov. Therefore it was not by chance that Štip