Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER II

The War and the Noncombatant Population

3. The Bulgarian peasant and the Greek army

It required no artificial incitement to produce the race hatred which explains the excesses of the Christian Allies, and more especially of the Bulgarians toward the Turks. Race, language, history, and religion have made a barrier which only the more tolerant minds of either creed are able wholly to surmount. It is less easy to explain the excesses of which Greeks and Bulgarians were guilty toward each other. The two races are sharply distinguished by temperament. A traditional enmity has divided them from the dawn of history, and this is aggravated in Macedonia by a certain social cleavage. But for a year the two races had been allies, united against a common enemy. When policy dictated a breach, it was necessary to prepare public opinion; and the Greek press, as if by a common impulse, devoted itself to this work. To the rank and file of all three Balkan armies, the idea of a fratricidal war was at first repugnant and inexplicable.The passions of the Greek army were roused by a daily diet of violent articles.The Greek press had had little to say regarding the Bulgarian excesses against the Turks while the facts were still fresh, and indeed none of the allies had the right to be censorious, for none of their records were clean. Now everything was dragged into the light, and the record of the Bulgarian bands, deplorable in itself, lost nothing in the telling. Day after day the Bulgarians were represented as a race of monsters, and public feeling was roused to a pitch of chauvinism which made it inevitable that war, when it came, should be ruthless. In talk and in print one phrase summed up the general feeling of the Greeks toward the Bulgarians, "Dhen einai anthropoi!" (They are not human beings). In their excitement and indignation the Greeks came to think of themselves as the appointed avengers of civilization against a race which stood outside the pale of humanity.

When an excitable

southern race, which has been schooled in Balkan conceptions of vengeance,

begins to reason in this way, it is easy to predict the consequences. Deny

that your enemies are men, and presently you will treat them as vermin.

Only half realizing the full meaning of what he said, a Greek officer remarked

to the writer, "When you have to deal with barbarians, you must behave

like a barbarian yourself. It is the only thing they understand." The Greek

army went into the war, its mind inflamed with anger and contempt. A

96 ![]()

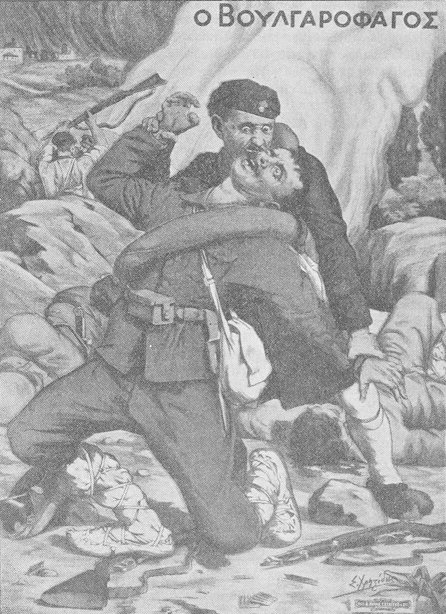

Fig. 12.-A popular Greek poster

97 ![]()

gaudily colored print, which we saw in the streets of Salonica and the Pireau eagerly bought by the Greek soldiers returning to their homes, reveals the dent of the brutality to which this race hatred had sunk them. It shows a Greek evzone (highlander) holding a living Bulgarian soldier with both hands, which he gnaws the face of his victim with his teeth, like some beast of prey. It is entitled the Bulgarophagos (Bulgar-eater), and is adorned with the following verses:

The sea of fire which boils in my breast

And calls for vengeance with the savage waves of my soul,

Will be quenched when the monsters of Sofia are still,

And thy life blood extinguishes my hate.

Another popular battle picture shows a Greek soldier gouging out the eyes of a living Bulgarian. A third shows as an episode of a battle scene the exploit of the Bulgar-eater.

As an evidence of the feeling which animated the Greek army these things have their importance. They mean, in plain words, that Greek soldiers wished to believe that they and their comrades perpetrated bestial cruelties. A print seller who issued such pictures in a western country would be held guilty of a gross libel on its army.

The excesses of the Greek army began on July 4 with the first conflict at Kukush (Kilkish). A few days later the excesses of the Bulgarians at Doxato (July 13), Serres (July 11), and Demir-Hissar (July 7) were known and still further inflamed the anger of the Greeks. On July 12 King Constantine announced in a dispatch which reported the slaughter at Demir-Hissar that he "found himself obliged with profound regret to proceed to reprisals." A comparison of dates will show that the Greek "reprisals" had begun some days before the Bulgarian "provocation."

It was with the defeat of the little Bulgarian army at Kukush (Kilkish) after a stubborn three days' defense against a superior Greek force, that the Greek campaign assumed the character of a war of devastation. The Greek army entered the town of Kukush on July 4. We do not propose to lay stress on the evidence of Bulgarian witnesses regarding certain events which preceded their entry. Shells fell outside the town among groups of fugitive peasants from the villages, while within the town shells fell in the orphanage and hospital conducted by the French Catholic sisters under the protection of the French flag. (See Appendix C, Nos. 30 and 31.) It is possible and charitable to explain such incidents as the effect of an unlucky chance. The evidence of European eye witnesses confirms the statements of the Bulgarian refugees on one crucial point. These shells caused no general conflagration, and it is doubtful whether more than three or four houses were set on fire by them. When the Greek army entered Kukush it was still intact. It is today a heap of ruins-as a member of the Commission reports, after a visit to which the Greek authorities opposed several

98 ![]()

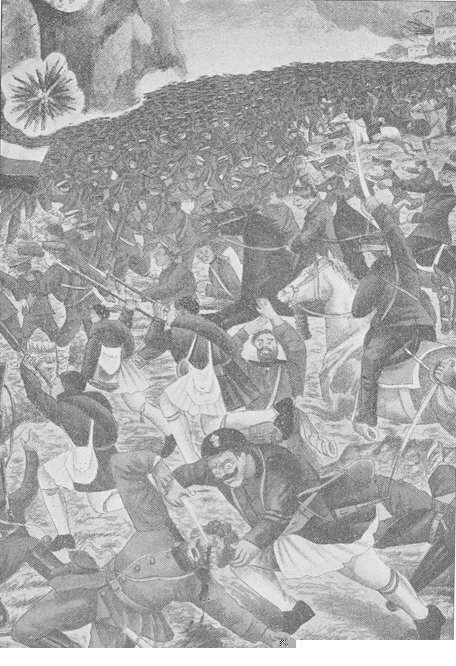

Fig. 13.-A popular Greek poster

99 ![]()

obstacles. It was a prosperous town of 13,000 inhabitants, the center of a purely Bulgarian district and the seat of several flourishing schools. The bent standards of its electric lamps still testify to the efforts which it had made to attain a level of material progress unusual in Turkey. That its destruction was deliberate admits of no doubt. The great majority of the inhabitants fled before the arrival of the Greeks. About four hundred, chiefly old people and children, had found shelter in the Catholic orphanage, and were not molested. European eye witnesses describe the systematic entry of the Greek soldiers into house after house. Any of the inhabitants who were found inside were first evicted, pillage followed, and then, usually after a slight explosion, the house burst into flames. Fugitives continued to arrive in the orphanage while the town was burning, and several women stated that they had been violated by Greek soldiers. In one case a soldier, more chivalrous than his comrades, brought a woman to the orphanage whom he had saved from violation. Some civilians were killed by the Greek cavalry as they rode in, and many lives were lost in the course of the sacking and burning of Kukush. We have received a detailed list from a Bulgarian source of seventy-four inhabitants who are believed to have been killed. Most of them are old women, and eleven are babies.

The main fact on which we must insist is that the Greek army inaugurated the second war by the deliberate burning of a Bulgarian town. A singular fact which has some bearing on Greek policy is that the refugees who took shelter in the French orphanage were still, on September 6, long after the conclusion of peace, closely confined as prisoners within it, though hardly a man among them is capable of bearing arms. A notice in Greek on its outer door states that they are forbidden to leave its precincts. Meanwhile, Greek (or rather "Grecoman") refugees from Strumnitsa were being installed on the sites of the houses which once belonged to Bulgarians, and in the few buildings (perhaps a dozen in number) which escaped the flames. The inference is irresistible. In conquering the Kukush district, the Greeks were resolved to have no Bulgarian subjects.

The precedent of Kukush was only too faithfully followed in the villages. In the Caza (county) of Kukush alone no less than forty Bulgarian villages were burned by the Greek army in its northward march. (See Appendix C, No. 52.) Detachments of cavalry went from village to village, and the work of the regulars was completed by bashi-basouks. It was a part of the Greek plan of campaign to use the local Turkish population as an instrument in the work of devastation. In some cases they were armed and even provided with uniforms. (See Appendix C, No. 43.) In no instance, however, of which we have a record were the Turks solely responsible for the burning of a village. They followed the Greek troops and acted under their protection. We have no means of ascertaining whether any general order was given which regulated the burning of the Bulgarian villages. A Greek sergeant among the prisoners of war in Sofia, stated in reply to a question which a member of the Commission put to him, that he and his comrades burned the villages around Kukush because the inhabitants had fled.

100 ![]()

It is a fact that one mainly Catholic village (Todoraki) in which most of the inhabitants remained, was not burned, though it was thoroughly pillaged. (See Appendix C, No. 32.) But the fate of other villages, notably Akangeli, in which the inhabitants not only remained, but even welcomed the Greek troops, disposes of this explanation. Whatever may have been the terms of the orders under which the Greek troops acted, the effect was that the Bulgarian villages were burned with few exceptions.

Refugees have described how, on the night of the fall of Kukush, the whole sky seemed to be aflame. It was a signal which the peasants understood. Few of them hesitated, and the general flight began which ended in massing the Bulgarian population of the districts through which the Greeks marched within the former frontiers of Bulgaria. We need not insist on the hardships of the flight. Old and young, women and children, walked sometimes for two consecutive weeks by devious mountain paths. The weak fell by the wayside from hunger and exhaustion. Families were divided, and among the hundred thousand refugees scattered throughout Bulgaria, husbands are still looking for wives, and parents for children. Sometimes the stream of refugees crossed the path of the contending armies, and the clatter of cavalry behind them would produce a panic, and a sauve qui peut in which mothers lost their children, and even abandoned one in the hope of saving another. (See Appendix C, Nos. 33, 34, 35.) They arrived at the end of their flight with the knowledge that their flocks had been siezed, their crops abandoned, and their homes destroyed. In all this misery and loss there is more than the normal and inevitable wastage of war. The peasants abandoned everything and fled, because they would not trust the Greek army with their lives. It remains to inquire whether this was an unreasonable fear.

The immense majority of the Macedonian refugees in Bulgaria were never in contact with the Greek army and know nothing of it at first hand. They heard rumors of excesses in other villages; they knew that other villages had been burned; they fled because everyone was fleeing; at the worst they can say that from a distance they saw their own village in flames. It would be easy to ascribe their fears to prejudice or panic, were it not for the testimony of the few who were in direct touch with the Greek troops. In the appendices will be found a number of depositions which the Commission took from refugees. It was impossible to doubt that these peasants were telling the truth. Most of them were villagers, simple, uneducated, and stunned by their sufferings, and quite incapable of invention. They told their tales with a dull, literal directness. In two of the more striking stories, we obtained ample corroboration in circumstances which admitted of no collusion. Thus a refugee from Akangeli, who had fled to Salonica, told us there a story of butchery and outrage (see Appendix C, No. 39) which tallied in almost every detail with the story afterwards told by another fugitive from the same village who had fled to Sofia (Appendix C, No. 41). While passing through Dubnitsa we inquired from a group of refugees

101 ![]()

whether any one present came from Akangeli. A youth stepped forward, who once more told a story which agreed with the two others (Appendix C, No. 42) The story of the boy Mito Kolev (Appendix C, No. 36) told in Sofia was similarly corroborated in an equally accidental way by two witnesses at Samakov (Appendix C, Nos. 37 and 38), who stepped out of a crowd of refugees in response to our inquiry whether anyone present came from the village in question (Gavaliantsi). We can feel no doubt about the truth of a story which reached us in this way from wholly independent eye witnesses. These two incidents are typical, and must be briefly summarized here.

Mito Kolev is an intelligent boy of fourteen, who comes from the Bulgarian village Gavaliantsi, in the Kukush district. He fled with most of his neighbors in the first alarm after the Bulgarian, defeat at Kukush, but returned next day to fetch his mother, who had remained behind. Outside the village a Greek trooper fired at him but missed him. The lad had the wit to feign death. As he lay on the ground, his mother was shot and killed by the same cavalryman. He saw another lad killed, and the same trooper then went in pursuit of a crippled girl. Of her fate Mito, who clearly distinguished between what he saw and what he suspected, knew nothing, but another witness (Lazar Tomov) chanced to see the corpse of this girl (Appendix B, No. 25). Mito's subsequent adventures were told very clearly and in great detail. The essential points are (1) that he saw his village burned, and (2) that another Greek cavalryman whom he met later in the day all but killed him with a revolver shot and a saber cut at close quarters, while he spared a by-stander who was able by his command of the language to pass himself off as a Greek. The material corroboration of this story is, that Mito still bore the marks of his wounds. A shot wound may be accidental, but a saber wound can only be given deliberately and at close quarters. A trooper who wounds a boy with his sword can not plead error. He must have been engaged in indiscriminate butchery. Of this particular squad of Greek cavalry, it is not too much to say that they were slaughtering Bulgarian peasants at sight, and that they spared neither women nor children.

The evidence regarding Akangeli (Appendix C, Nos. 39-42, and Appendix D, No. 63, paragraph b) points to the same conclusion. In this Bulgarian village near the Lake of Doiran, refugees from many of the neighboring villages, who are said to have numbered 4,000 persons, had halted in their flight. A squadron of Greek cavalry, numbering about 300 men, with officers at its head, arrived between 3 and 4 p.m. on Sunday, July 6. The villagers with their priest went out to meet them with a white flag and the Greek colors. The officer, in conversation with the mayor, accepted their surrender and ordered them to give up any arms they possessed. The peasants brought bread and cheese, and thirty sheep were requisitioned and roasted for the troops. Some sixty of the men of the place were separated from the others and sent away to a wood. Of their fate nothing is known. The villagers be-

102 ![]()

lieve that they were slaughtered, but we have reason to hope that they may have been sent as prisoners to Salonica. While the rifles were being collected the troopers began to demand money from both men and women. The women were searched with every circumstance of indignity and indecency. One witness, a well to do inhabitant of Kukush, was bound together with a refugee whose name he did not know. He gave up his watch and five piastres and his life was spared. His companion, who had no money, was killed at his side. While the arms were being collected, one which was loaded went off accidentally and wounded an officer, who was engaged in breaking the rifles. Two youths who were standing near were then killed by the soldiers, presumably to avenge the officer's mishap. Toward evening the soldiers forced their way into the houses and began to violate the women.

Another witness, the butcher who roasted the sheep for the troops, saw two young women, whom he named, violated by three soldiers beside his oven. Infantry arrived on Monday, and shortly afterwards the village was set on fire. During Sunday night and on Monday morning many of the villagers were slaughtered. It is impossible to form an estimate of the number, for our witnesses were in hiding and each saw only a small part of what occurred. One of them estimated the number at fifty, but this was clearly only a guess. We have before us a list from a Bulgarian source of 356 persons from seven villages who have disappeared and are believed to have been killed at Akangeli. Turks from neighboring villages joined in the pillage under the eyes of the Greek soldiers and their officers. The facts which emerge clearly from our depositions are (1) that the village submitted from the first; (2) that it was sacked and burned; (3) that the Greek troops gave themselves up openly and generally to a debauch of lust; (4) that many of the peasants were killed wantonly and without provocation.

It would serve no purpose to encumber this account of the Greek march with further narratives. Many further depositions will be found in the appendices. They all convey the same impression. Wherever the peasants ventured to await the arrival of the Greek troops in their villages, they had the same experience. The village was sacked and the women were violated before it was burned, and noncombatants were wantonly butchered, sometimes in twos or threes, sometimes in larger numbers. We would call attention particularly to two of these narratives-that of Anastasia Pavlova, an elderly women of the middle class, who told her painful and dramatic story with more intelligence and feeling than most of the peasant witnesses. (Appendix C, No. 43.) Like them, she suffered violation; she was robbed, and beaten, and witnessed the dishonor of other women and the slaughter of noncombatant men. Her evidence relates in part to the taking of the town of Ghevgheli. Ghevgheli, which is a mixed town, was not burned, but a reliable European, well acquainted with the town, and known to one member of the Commission as a man of honor and ability,

103 ![]()

stated that fully two hundred Bulgarian civilians were killed there on the entry of the Greek army.

Another deposition to which we would particularly call attention is that of Athanas Ivanov, who was an eye witness of the violation of six women and the murder of nine men in the village of Kirtchevo. (Appendix C, No. 44.) His story is interesting because he states that one Greek soldier who protested against the brutality of his comrades was overruled by his sergeant, and further that the order to kill the men was given by officers. It is probable that some hundreds of peasants were killed at Kirtchevo and German in a deliberate massacre, carried out with gross treachery and cruelty. (See also Appendix D, Nos. 59-62.) For these depositions the Commission assumes responsibility, in the sense that it believes that the witnesses told the truth; and, further, that it took every care to ascertain by questioning them whether any obvious excuse, such as a disorderly resistance by irregulars in the neighborhood, could be adduced. These depositions relate to the conduct of the Greek troops in ten villages. We should hesitate to generalize from this basis (save as to the fact that villages were almost everywhere burned), but we are able to add in the appendix a summary of a large number of depositions taken from refugees by Professor Miletits of Sofia University. (See Appendix D, No. 63.) While it can not assume personal responsibility for this evidence, the Commission has every confidence in the thoroughness with which Professor Miletits performed his task.

This great mass of evidence goes to show that there was nothing singular in the cases which the Commission itself investigated. In one instance a number of Europeans witnessed the brutal conduct of a detachment of Greek regulars under three officers. Fifteen wounded Bulgarian soldiers took refuge in the Catholic convent of Paliortsi, near Ghevgheli, and were nursed by the sisters. Father Alloati reported this fact to the Greek commandant, whereupon a detachment was sent to search the convent for a certain Bulgarian voyevoda (chief of bands) named Arghyr, who was not there. In the course of the search a Bulgarian Catholic priest. Father Treptche, and the Armenian doctor of the convent were severely flogged in the presence of the Greek officers. A Greek soldier attempted to violate a nun, and during the search a sum of ?T300 was stolen. Five Bulgarian women and a young girl were put to the torture, and a large number of peasants carried off to prison for no good reason. The officer in command threatened to kill Father Alloati on the spot and to burn down the convent. If such things could be done to Europeans in a building under the protection of the French flag, it is not difficult to believe that Bulgarian peasants fared incomparably worse.

The Commission regrets that the attitude of the Greek government toward its work has prevented it from obtaining any official answer to the charges which emerge from this evidence. The broad fact that the whole of this Bulgarian region, for a distance of about one hundred miles, was devastated and nearly

104 ![]()

every village burned, admits of no denial. Nor do we think that military necessity could be pleaded with any plausibility. The Greeks were numerically greatly superior to their enemy, and so far as we are aware, their flanks were not harassed, nor their communications threatened by guerrillas, who might have found shelter in the villages. The Greeks did not wait for any provocation of this kind, but everywhere burned the villages, step by step with their advance. The slaughter of peasant men could be defended only if they had been taken in the act of resistance with arms in their hands. No such explanation will fit the cases on which we have particularly laid stress, nor have any of the war correspondents who followed the Greek army reported conflicts along the main line of the Greek march with armed villagers. The violation of women admits of no excuse; it can only be denied.

Denial unfortunately is impossible. No verdict which could be based on the evidence collected by the Commission could be more severe than that which Greek-soldiers have pronounced upon themselves. It happened that on the eve of the armistice (July 27) the Bulgarians captured the baggage of the Nineteenth Greek infantry regiment at Dobrinichte (Razlog). It included its post-bags, together with the file of its telegraphic orders, and some of its accounts. We were permitted to examine these documents at our leisure in the Foreign Office at- Sofia. The file of telegrams and accounts presented no feature of interest. The soldiers' letters were written often in pencil on scraps of paper of every sort and size. Some were neatly folded without envelopes. Some were written on souvenir paper commemorating the war, and others on official sheets. Most of them bore the regimental postal stamp. Four or five were on stamped business paper belonging to a Turkish firm in Serres, which some Greek soldier had presumably taken while looting the shop. The greater number of the letters were of no public interest, and simply informed the family at home that the writer was well, and that his friends were well or ill or wounded as the case might be. Many of these letters still await examination. We studied with particular care a series of twenty-five letters, which contained definite avowals by these Greek soldiers of the brutalities which they had practiced. Two members of the Commission have some knowledge of modern Greek. We satisfied ourselves (1) that the letters (mostly illiterate and ill written'> had been carefully deciphered and honestly translated; (2) that the interesting portions of the letters were in the same handwriting as the addresses on the envelopes (which bore the official stamp) and the portions which related only personal news; (3) that no tampering with the manuscripts had been practiced. Some minor errors and inaccuracies are interesting, as an evidence of authenticity. Another letter is dated by error July 15 (old style), though the post-bags were captured on the 14th (27th). We noted, moreover, that more than one slip (including an error of grammar) had been made by the Bulgarian secretary in transcribing the addresses of the letters from Greek into Latin script -a proof that he did not know enough

105 ![]()

Greek to invent them. But it is unnecessary to dwell on these minor evidences of authenticity. The letters have been published in fac simile. The addresses and the signatures are those of real people. If they had been wronged by some incredibly ingenious forger, the Greek government would long ago have brought these soldiers before some impartial tribunal to prove by specimens of their genuine handwriting that they did not write these letters. The Commission, in short is satisfied that the letters are genuine.

The letters require no commentary. Some of the writers boast of the cruelties practiced by the Greek army. Others deplore them. The statements of fact (see Appendix C, No. 51) are simple, brutal, and direct, and always to the same effect. These soldiers all state that they everywhere burned the Bulgarian villages. Two boast of the massacre of prisoners of war. One remarks that all the girls they met with were violated. Most of the letters dwell on the slaughter of noncombatants, including women and children. These few extracts, each from a separate letter, may suffice to convey their general tenor:

By order of the King we are setting fire to all the Bulgarian villages, because the Bulgarians burned the beautiful town of Serres, Nigrita, and several Greek villages. We have shown ourselves far more cruel than the Bulgarians. * * *

Here we are burning the villages and killing the Bulgarians, both women and children. * * *

We took only a few [prisoners], and these we killed, for such are the orders we have received.

We have to burn the villages-such is the order-slaughter the young people and spare only the old people and the children. * * *

What is done to the Bulgarians is indescribable; also to the Bulgarian peasants. It was a butchery. There is not a Bulgarian town or village but is burned.

We massacre all the Bulgarians who fall into our hands and burn the villages.

Of the 1,200 prisoners we took at Nigrita, only forty-one remain in the prisons, and everywhere we have been we have not left a single root of this race.

We picked out their eyes [five Bulgarian prisoners] while they were still alive.

The Greek army sets fire to all the villages where there are Bulgarians and massacres all it meets. * * * God knows where this will end.

These letters relieve us of the task of summing up the evidence. From Kukush to the Bulgarian frontier the Greek army devastated the villages, violated the women, and slaughtered the noncombatant men. The order to carry out reprisals was evidently obeyed. We repeat, however, that these reprisals began before the Bulgarian provocation. A list of Bulgarian villages burned by the Greek army which will be found in Appendix C (No. 52) conveys some measure of this ruthless devastation. At Serres the Bulgarians destroyed 4,000

106 ![]()

houses in the conflagration which followed the fighting in the streets. The ruin of this considerable town has impressed the imagination of the civilized world. Systematically and in cold blood the Greeks burned one hundred and sixty Bulgarian villages and destroyed at least 16,000 Bulgarian homes. The figures need no commentary.

THE FINAL EXODUS

No account of the sufferings of the noncombatant population in Macedonia would be complete which failed to describe the final exodus of Moslems and Greeks from the territory assigned to Bulgaria. Vast numbers of Moslems arrived on the outskirts of Salonica during our stay there. We saw them camped to the number, it is said, of 8,000, in the fields and by the roadside. They had come with their bullock carts, and whole families found their only shelter in these primitive vehicles. They had left their villages and their fields, and to all of them the future was a blank. They did not wish to go to Asia, nor did they wish to settle, they knew not how nor where, in Greek territory. They regretted their homes, and spoke with a certain passive fatalism of the events which had made them wanderers. They were, when we visited them, without rations, but we heard that the Greek authorities afterwards made some effort to supply them with bread.

The history of this exodus is somewhat complicated. It was part of the Greek case to assert that no minority, whether Greek or Moslem, can safely live under Bulgarian rule. The fact is, that of all the Balkan countries, Bulgaria alone has retained a large proportion of the original Moslem inhabitants. Official Greek statements predicted, before peace was concluded, that the Moslem and Greek minorities would emigrate from the new Bulgarian territories in a body. The popular press went further, and announced that with their own hands they would bum down their own houses. When the time arrived, steps were taken to realize these prophecies, more particularly at Strumnitsa and in the neighboring villages.

We questioned several groups of these Moslem peasants on the roadside near Salonica. (Appendix A, No. 4.) We took the deposition of a leading Turkish notable of Strumnitsa, Hadji Suleiman Effendi.(See Appendix A, No. 3.) We questioned the Greek refugees from the same town who were at Kukush.We obtained Bulgarian evidence at Sofia. (See Appendix D, No. 65.) Finally, we have before us the confidential evidence of an authoritative witness, a subject of a neutral power, who visited the town before the exodus was complete. From all these sources we heard the same story. The Greek military authorities in Strumnitsa gave the explicit order that all the Moslem and Greek inhabitants of the town and villages must abandon their homes and emigrate to Greek territory. The order was backed by the warning that their houses would be burned. Persuasion was used and was,

107 ![]()

in the case of the Greeks, partially successful. They were told that the Bulgarians would massacre them if they remained. They were also assured that a new Strumnitsa would be built for them at Kukush on a splendid scale and they were promised houses and lands. Some of the leaders of the Greek community eagerly embraced this policy and used their influence to enforce it. The Greek exodus was far from being spontaneous, but it was on the whole voluntary. Our conviction is that the Moslems yielded to force. It is true that they had had a terrible experience under the mixed Serbo-Bulgarian rule in the early weeks of the first war. But this they had survived, and most of them stated that Bulgarian rule, after this first excess, had been at least tolerable. Most of them departed in obedience to the order. Some vainly attempted to bribe the Greek soldiers. A few obstinately remained and were evicted by force. The same procedure was followed in the villages.

The emigration began about August 10. On the evening of Wednesday, August 21, parties of Greek soldiers began to burn the empty houses of the Moslem and Greek quarters on a systematic plan, and continued their work on the following nights up to August 23. The Greeks evacuated what was left of the town on August 27, and handed it over to the Bulgarian troops. The Bulgarian quarter was not burned, since the object of the Greeks was to circulate the legend that the non-Bulgarian inhabitants had themselves burned their own houses. To estimate the full significance of this extraordinary outrage, it must be remembered that it was perpetrated in time of peace, after the signature of the Peace of Bucharest.

A similar emigration of the Greek inhabitants of Melnik also took place under pressure. Their houses, however, were not burned, and there are indications that some of them will endeavor to return when the pressure is relaxed.

We found some hundreds of the Greek fugitives from Strumnitsa. at Kukush. They are not, in point of fact, Greeks at all, but Slavs, bi-lingual for the most part, who belong to the Greek party and the Patriarchist Church. One woman had a husband still serving in the Bulgarian army; she at least was not a voluntary fugitive from Bulgarian rule. These people were camped amid the ruins of Kukush, some in the few houses which escaped the conflagration, and others in improvised shelters. They received rations, and hoped to see the "New Strumnitsa" arise on the ashes of what was once a Bulgarian town. From the windows of the Catholic orphanage the remnant of the genuine population of Kukush, closely imprisoned, watched the newcomers establishing themselves on sites which were once their own. The Greek authorities are apparently determined to dispose of the lands of the fugitive Bulgarian villagers as though conquest had wiped out all private rights of property. The fugitives from Strumnitsa are simple people. One man spoke rather naively of his first horror at the idea of leaving his native place. Later, he said, he had acquiesced; he supposed the authorities knew best. Another fugitive, a village priest, regretted

108 ![]()

his home, which had, he said, the best water in all Macedonia. But he was sure that flight was wise. He had reason to fear the Bulgarians. A comitadji, early in the first war, pointed a rifle at his breast, and said: "Become a Bulgarian, or I'll kill you." He forthwith became a Bulgarian for several months and conformed to the exarchist church. These "Greeks" will probably be well cared for, and may have a prosperous future. The Moslem fugitives furnish the tragic element of this enforced exodus. It creates three problems: What will become of these uprooted Turkish families? Who will acquire the lands they have left behind? By what right can the Greeks dispose of the Bulgarian lands in the Kukush region? The problem may solve itself by some rough exchange, but not without endless private misery and immense injustice.

___

In bringing this painful

chapter to a conclusion, we desire to remind the reader that it presents

only a partial and abstract picture of the war. It brings together in a

continuous perspective the sufferings of the noncombatant populations of

Macedonia and Thrace at the hands of armies flushed with victory or embittered

by defeat. To base upon it any moral judgment would be to show an uncritical

and

unhistorical spirit. An estimate of the moral qualities of the Balkan peoples

under the strain of war must also take account of their courage, endurance,

and devotion. If a heightened national sentiment helps to explain these

excesses, it also inspired the bravery that won victory and the steadiness

that sustained defeat. The moralist who seeks to understand the brutality

to which these pages bear witness, must reflect that all the Balkan races

have grown up amid Turkish models of warfare. Folk-songs, history and oral

tradition in the Balkans uniformly speak of war as a process which includes

rape and pillage, devastation and massacre. In Macedonia all this was not

a distant memory but a recent experience. The new and modern feature of

these wars was that for the first time in Balkan annals an effort, however

imperfect, was made by some of the combatants and by some of the civil

officials, to respect an European ideal of humanity. The only moral which

we should care to draw from these events is that war under exceptional

conditions produced something worse than its normal results. The extreme

barbarity of some episodes was a local circumstance which has its root

in Balkan history. But the main fact is that war suspended the restraints

of civil life, inflamed the passions that slumber in time of peace, destroyed

the natural kindliness between neighbors, and set in, its place the will

to injure. That is everywhere the essence of war.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]