Carnegie Endowment for International peace

Report ... to inquire into the causes and Conduct of

the Balkan Wars

CHAPTER II

The War and the Noncombatant Population

2. The conduct of the Bulgarians in the Second war

The charges brought by the Greeks against the Bulgarians are already painfully familiar to every newspaper reader. Unlike the Bulgarians, the Greeks welcomed war correspondents, and every resource of publicity was at their disposal, while Bulgaria itself was isolated and its telegraphic communications cut. That some of these accusations were grossly exaggerated is now apparent. Le Temps, for example, reported the murder of the Greek Bishop of Doiran. We saw him vigorous and apparently alive two months afterwards. A requiem mass was sung for the Bishop of Kavala; his flock welcomed him back to them while we were in Salonica. The correspondent of the same newspaper stated that he personally assisted at the burial of the Archbishop of Serres, who was savagely mutilated before he was killed. (Letter, dated Livonovo, July 23.) This distressing experience in no way caused this prelate to interrupt his duties, which he still performs.

There none the less

remains, when these manifest travesties of fact are brushed aside, a heavy

indictment which rests upon uncontrovertible evidence. It is true that

the little town of Doxato was burned and a massacre carried out there during

and after a Bulgarian attack. It is true that the town of Serres was burned

during a Bulgarian attack. It is also true that a large number of civilians,

including the Bishop of Melnik and Demir-Hissar, were slaughtered or executed

by the Bulgarians in the latter town. The task of the Commission has been

to compare the evidence from both sides regarding these events, and to

form a judgment on the circumstances which in some degree explain them.

The Greek charges are in each case substantially true, but in no case do

they state the whole truth.

In forming an opinion upon the series of excesses which marked the Bulgarian withdrawal from southeastern Macedonia, it is necessary to recall the fact that the Bulgarians were here occupying a country whose population is mainly Greek and Turkish. The Bulgarian garrisons were small, and they found themselves on the outbreak of the second war in a hostile country. The Greek population of these regions is wealthy and intensely patriotic. In several Greek centers insurgent organizations (andartes) existed. Arms had been collected, and some experienced guerrilla chiefs were believed to be in hiding, and ready to lead the local population. All of this in existing conditions was creditable to Greek patriotism; their race was at war with Bulgarians, and the more enterprising and courageous among them intended to take their share as auxiliaries Of the Greek army in driving the Bulgarians from their country. From a nation-

79 ![]()

alist standpoint, this was morally their right and some might even say their duty. But it is equally clear that the Bulgarians, wherever they found themselves opposed by the armed civil population, had also a right to take steps to protect themselves. The steps which they elected to take in some places grossly exceeded the limits of legitimate defense or allowable reprisal.

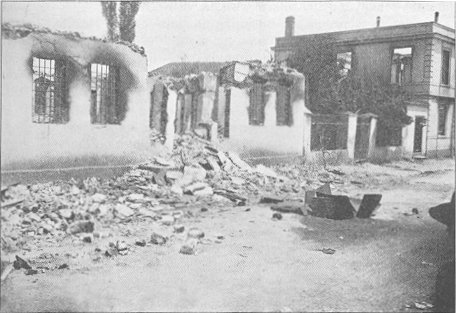

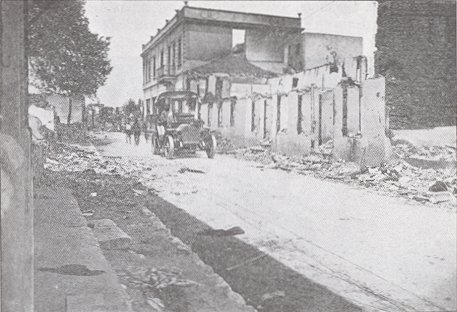

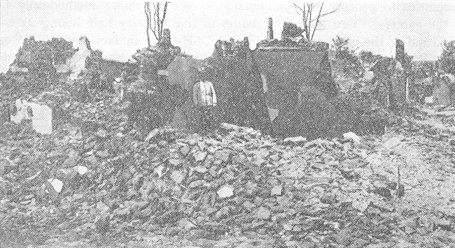

THE MASSACRE AT DOXATO

Doxato was a thriving country town, situated between Drama and Kavala in the center of a rich tobacco growing district. It had a large school, and counted several wealthy and educated families among its 2,700 Greek inhabitants. It was proud of its Hellenic character, and formed with two neighboring villages a compact Greek island in a rural population which was almost exclusively Turkish. A member of the Commission has visited its ruins. Only thirty homes are left intact among its 270 Greek houses. Enough remains of the walls to show that the little town was well built and prosperous, and to suggest that the conflagration must have caused grievous material loss to the inhabitants. The estimate of killed (at first said to number over 2,000) which is now generally accepted by the Greeks, is 600. We have had communicated to us an extract from an official Greek report in which 500 is given as an outside figure.

A large proportion, probably one-half, of this total consisted of civilians who had taken up arms. Women and children to the number of over a hundred were massacred in a single house, and the slaughter was carried out with every

Fig. 1.-Ruins of Doxato

80 ![]()

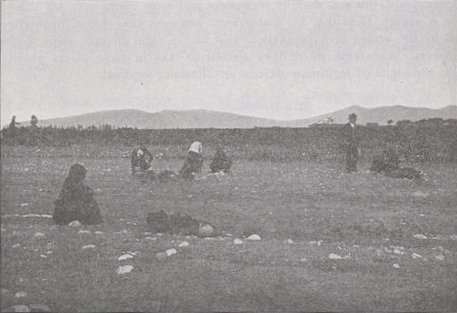

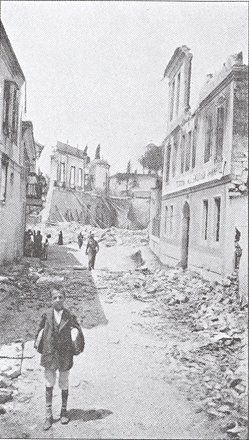

Fig. 2.-Finding the

bodies of victims at Doxato

conceivable circumstance of barbarity. We print in Appendix B (No. 14) a letter in which Commander Cardale, a British naval officer in the Greek service, describes the condition of the village when he visited it shortly after the massacre.

We print in Appendix B, Bulgarian accounts of the Doxato affair. Mr. Dobrev, who was the prefect of Drama and earned the good opinion of the Greeks by his conduct there (see the Greek pamphlet Atrocites Bulgares, p. 49), has told the whole story with evident frankness. (Appendix B, No. 16.)Captain Sofroniev of the Royal Guard, who commanded the two squadrons of cavalry which operated against Doxato, relates his own part in the affair clearly, and has shown us the reports of his scouts penciled on official paper. (See Appendix B, No. 15.) Lieutenant Milev in a communicated deposition describes his experiences with the infantry, and Lieutenant Colonel Barnev explains his military dispositions. (See Appendix B, Nos. 16a and 16b.) These four depositions leave no doubt in the mind of the Commission that the Greeks had organized a formidable military movement among the local population; that Doxato was one of its centers; and that several hundreds of armed men were concentrated there. Provocation had been given not only by the wanton and barbarous slaughter by Greeks of Moslem noncombatants, but also by a successful attack at Doxato upon a Bulgarian convoy. There was, therefore, justification for the order given From the Bulgarian headquarters to attack the Greek insurgents concentrated in Doxato.

81 ![]()

It appears from Captain Sofroniev's report that his men met with an obstinate resistance from these Greek andartes and that one of his two squadrons lost seventeen killed and twenty-four wounded in the attack. In the charge b\ which he finally dispersed them, he believes that his men killed at least 150 Greeks, and perhaps double this number. These were, he assures us, all armed men and combatants.

We find it hard to believe that an irregular and inexperienced force can have resisted cavalry with an obstinacy that would justify so large a slaughter as this. A woman, moreover, was wounded in this charge. (See Appendix B, No. 16.) Captain Sofroniev states that his men took prisoners. He consigned these prisoners to the charge of the Turkish peasants who had come up from neighboring villages, full of resentment for Greek excesses against their neighbors. He allowed these Turks to arm themselves with the weapons of the defeated Greek insurgents. He might as well have ordered the massacre of his prisoners. These Turks had recent grievances against the Greeks, and they had come to Doxato in the rear of the Bulgarian force for pillage and revenge.

The cavalry operated outside the village. The force which entered it was an infantry detachment comprised in great part of Bulgarian Moslems (pomaks). According to Mr. Dobrev, who is clearly the franker witness, it became excited when a magazine of cartridges exploded in the village, and began to kill indiscriminately all the inhabitants whom it met in the streets, including some children. It remained, however, only a short while in Doxato.

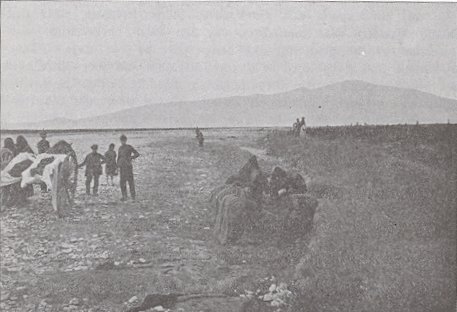

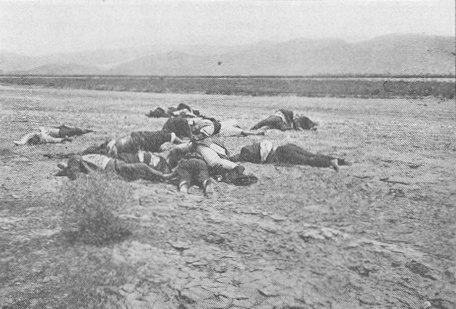

Fig. 3.-Gathering

the bodies of victims

82 ![]()

Fig. 4.-Bodies of

slain peasants

Lieutenant Milev's

account attributes this slaughter to the local Turks, and states that two

of them were executed for their crimes. He represents the inhabitants whom

his men killed as insurgents.

We can not explain this discrepancy. It is, however, clear that the systematic massacre was carried out by the local Turks who were left in possession of the place for the better part of two days.They pillaged, burned, and slaughtered at their leisure, nor did they spare even the women who had taken refuge in the houses of friendly Turks. So far there is little difference between Commander Cardale's version of events, based on local Greek sources, and the statements of our Bulgarian witnesses. What we heard ourselves in the village some weeks later agreed with what Commander Car-dale has reported. The Bulgarian troops, after a sharp engagement, began the killing of the inhabitants, but presently desisted. "The greater part of the massacre," as Commander Cardale puts it, "was done by the Turks." He quotes, without endorsing it, the statement of the survivors that the Turks acted under the "direction" or "incitement" of Bulgarian officers. We gather that he heard no convincing evidence on this head, nor did we meet with anyone who had personally heard or seen Bulgarian officers giving directions to massacre. That charge may be dismissed as baseless. But some part of the responsibility for ;he slaughter falls, none the less, upon the Bulgarian officers. They armed the 1'urks and left them in control of the village. They must have known what would follow. The employment of Turkish bashi-bazouks as allies against de-

83 ![]()

fenseless Christian villagers was an offense of which Greeks, Servians, and Bulgarians were all guilty upon occasion. No officer in the Balkans could take this step without foreseeing that massacre must result from it.

It is fair none the less to note that the Bulgarians were in a difficult position. They could not occupy the village permanently, for they were threatened by Greek columns marching from several quarters. To leave the Turks unarmed was to expose them to Greek excesses. To arm the Turks was, on the other hand, to condemn the Greek inhabitants to massacre. A culpable error of judgment was committed in circumstances which admitted only of a choice of evils. While emphasizing the heavy responsibility which falls on the Bulgarian officers for this catastrophe, we do not hesitate to conclude that the massacre at Doxato was a Turkish and not a Bulgarian atrocity.

THE MASSACRE AND CONFLAGRATION OF SERRES

Serres is the largest town of the interior of eastern Macedonia. The tobacco trade had brought considerable wealth to its 30,000 inhabitants; and it possessed in its churches, schools and hospitals the outward signs of the public spirit of its Greek community. The villages around it are Bulgarian to the north and west, but a rural Greek population approaches it from the south and east. The town itself is predominantly Greek, with the usual Jewish and Turkish admixture. The Bulgarians formed but a small minority. From October to June the town was under a Bulgarian occupation, and as the second war drew near, the relations of the garrison and the citizens became increasingly hostile. The Bulgarian authorities believed that the Greeks were arming secretly, that andartes (Greek insurgents) were concealed in the town, and that a revolt was in preparation. Five notables of the town were arrested on July 1 with the idea of intimidating the population. On Friday, July 4, the defeat of the Bulgarian forces to the south of Serres rendered the position untenable, and arrangements were made for the evacuation of the town. General Voulkov, the Governor of Macedonia, and his staff left on the evening of Saturday, July 5. The retirement was hastily planned and ill executed. There is evidence from Greeks and Turks, and from one of the American residents, Mr. Moore, that some of the troops found time to pillage before withdrawing. On the other hand, stores of Bulgarian munitions, including rifles, were abandoned in the town, and some of the archives were also left behind. We gather that there was some conflict of authority among the superior Bulgarian officers. (See evidence of Commandant Moustakov, Appendix B, No. 26.)

The plain fact is that at this central point the organization and discipline of the Bulgarian troops broke down. Some excesses, as one would expect, undoubtedly occurred, but the Greek evidence on this matter is untrustworthy. Commandant Moustakov believes that the notables who had been arrested were released. We find, on the other hand, in the semiofficial Greek pamphlet Atrocites

84 ![]()

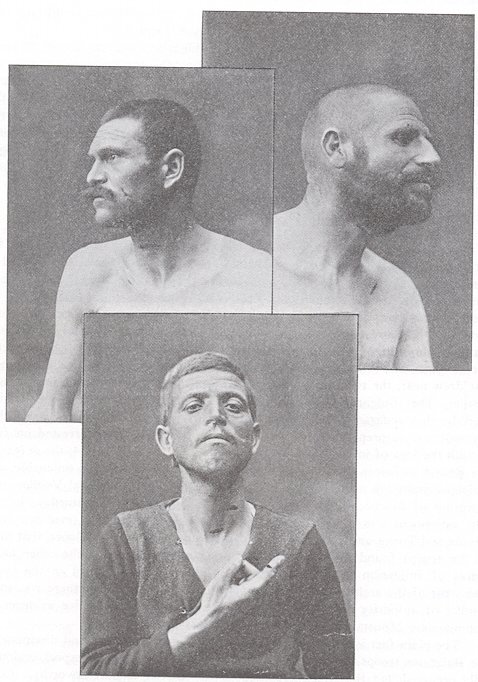

Fig. 5. - Victims who escaped the Serres slaughter

85 ![]()

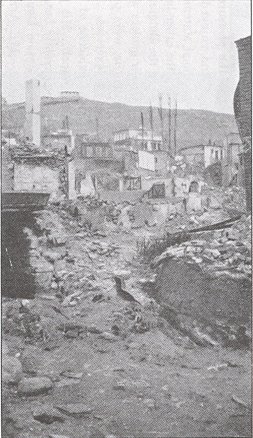

Fig. 6. - Ruins of

Serres

Bulgares, the

statement (p. 25) that the bodies of four Greek notables were found outside

the town killed by bayonet thrusts; among them was the corpse of the director

of the Orient bank. For this assertion the authority of the Italian and

Austrian consuls general of Salonica is claimed. (See Appendix B, No. 17.)

The member of our Commission who visited Serres had the pleasure of meeting

this gentleman, Mr. Ghine, alive, well, and unharmed, and enjoyed his hospitality.

Such discoveries as this are a warning that even official statements regarding

these events must be subjected to careful scrutiny. On the other hand,

there is no doubt that some of the prisoners who were in gaol when the

Bulgarians left the town, were slaughtered. This was done presumably by

their gaolers without orders. The imprisoned Bulgarians, including many

comitadjis,

were probably released; it is conceivable that they had a hand in these

excesses. The fact of a butchery in the prison is placed beyond doubt by

the evidence of Mr. Arrington, the manager of the American Tobacco Company's

branch. His porter

(cavass), a Greek, had been arrested some days

before, apparently because a rumor had got abroad that the famous Greek

guerrilla chief. Captain Doukas, was in the town disguised as the cavass

of a tobacco warehouse. Mr. Arrington demanded the release of his employee

without result. After the departure of the last of the Bulgarian troops,

Mr. Arrington visited the prison and found there a heap of thirteen corpses,

among which was his man, severely wounded. He died shortly afterwards in

hospital, but was able to tell his story. His Bulgarian gaoler had demanded

a ransom of ,?10 for his release and would allow him

86 ![]()

Fig. 7. - Ruins of

Serres

Fig. 8. - Ruins of

Serres

87 ![]()

no facilities to procure it from outside. "We do things methodically here said the gaoler. "You have four hours to live. Every half hour you will b beaten, and at the end you will be killed." He was in fact made to lie on hi back and was pinned to the floor with a bayonet. Mr. Arrington stated that hi arms and back, where he had been beaten, were "as black as his boots." The other twelve prisoners had evidently been treated with equal barbarity.

The main body of the Bulgarian garrison, with the headquarters, withdrew from Serres on Saturday, July 5. A panic followed, and a squadron of dismounted Bulgarian cavalry paraded the town to maintain order. The Greek irregulars and armed citizens were already under arms, and fired from some

Fig. 9. - Ruins of Serre

of the houses at this

squadron. It camped that night outside the town, and entered it again on

Sunday, but apparently without attempting to maintain complete control.

On Monday, July 7 (if not on Sunday), the effective authority passed into

the hands of the local Greeks. The Archbishop was recognized as governor

of the town, and at his palace there sat in permanence a commission of

the local inhabitants. Thirty armed Greeks wearing the evzone (highlander)

uniform, who were, however, probably irregulars (andartes), had

arrived in Serres, and one witness states that they were under the command

of Captain Doukas. A Russian doctor in the Bulgarian sanitary service (Dr.

Klugmann, see Appendix B, No. 22), who was left in the town, heard on Monday

a Greek priest summoning the inhabitants to the Bishop's palace, where

arms were

88![]()

Fig. 10. - Ruins of

Serres

distributed, first

to the Greeks, and later to the Turks. From Monday morning to Thursday

evening these Greek irregulars and the citizen militia which they organized

were in possession of the town. Thrice they were threatened by small Bulgarian

detachments, which returned and skirmished on the hills outside the town

and at the distant railway station. But these Bulgarian scouts were not

a sufficient force to enter the town. A telegram dispatched on Thursday

by :he Archbishop to King Constantine (see Le Temps, July 13), begs

him to hasten ;o occupy the town, which is, he says, defending itself successfully

against the

Fig. 11. - Ruins of

Serres

89 ![]()

attacks of the Bulgarians. He mentions that he is governing the town and states that it has been abandoned for a week by the Bulgarian authorities. He fears, however, that the citizens' power of resistance may soon be exhausted. These rather aimless Bulgarian attacks must have contributed to excite the local Greeks, and to inflame a spirit of vengeance.

The main concern of the Archbishop's Greek militia during this week was apparently to hunt down the Bulgarian population within the town and in some of the neighboring villages. It is conceivable that this measure may have been dictated in the first instance by the fear that the small Bulgarian minority inside Serres would cooperate with the enemy who attacked it from without. An armed Greek mob followed a few uniformed men from house to house, threatening the Bulgarians and all who should assist them to hide. Their houses were pillaged and their wives ill treated, while the men were arrested and taken singly or in batches to the Bishop's palace; there they were brought before a commission of laymen over whom a priest presided. Whatever money they possessed was taken from them by this priest, and the only question asked about them was, whether they were or were not Bulgarians. This process was witnessed by Dr. Klugmann, and the testimony of this Russian doctor entirely confirms that of our Bulgarian peasant witnesses. From the bishopric the prisoners were taken to the neighboring Greek girls' high school. In the school they were closely confined in several rooms by fifties and sixties. Fresh batches arrived continuously from the town and from the villages, until the total number of imprisoned Bulgarians reached 200 or 250. The gaolers were in part citizens of Serres, some of whom can be named, and in part uniformed irregulars. From the first they behaved with gross cruelty. The prisoners were tightly bound and beaten with the butt ends of rifles. The plan of the gaolers was apparently to slaughter their prisoners in batches, and they were led two by two to an upper room, where they were killed, usually by repeated wounds in the head and neck inflicted with a butcher's knife or a Martini bayonet. Each of the butchers aimed at accounting for fourteen men, which was apparently the number which each could bury during the night. The massacre went on in this leisurely way until Friday, the 11th. The prisoners included a few captured Bulgarian soldiers, a few peasants taken with arms in their hands (see evidence of the villager Lazarov, Appendix B, No. 20), and at least one local Bulgarian, Christo Dimitrov (Appendix B, No. 19), who was known to be an active associate of the Bulgarian bands. The immense majority were, however, inoffensive tradesmen or. peasants whose only offense was that they were Bulgarians. Among them were four women, who were killed with the rest. The only mitigating circumstance is that five lads were released in pity for their youth, after seeing their fathers killed before their eyes. (See Blagoi Petrov, Appendix B, No. 21.) We are unwilling to dwell on the detailed barbarities of this butchery, of which more than enough is recorded in the appendices.

90 ![]()

We must here anticipate a part of the narrative to explain that in the early morning of Friday, July 11, a Bulgarian regular force with cavalry and light artillery reached Serres, engaged the militia outside the town, defeated it, and began toward noon to penetrate into the town itself. There were still sixty or seventy of the Bulgarian prisoners alive, and their gaolers, alarmed by the sound of cannon in the distance, resolved to finish their work rapidly. Two at least of the prisoners (Angelov and Limonov) contrived to overpower the sentinels and escaped. Some of them, however, were bound and others were too enfeebled or too terrified to save themselves. They were led to the slaughter by fours and fives, but the killing this day was inefficient, and at least ten of the prisoners fell among the heaps of corpses, severely wounded indeed, but still alive. They recovered consciousness in the early afternoon, to realize that their gaolers had fled, that the town was on fire, and that the Bulgarian troops were not far distant. Ten of them struggled out of the school, and eight had strength enough to reach safety and their countrymen.

The Commission saw three of these fugitives from the Serres massacre, (Karanfilov, Dimitrov, and Lazarov, Appendix B, Nos. 18, 19, 20), who all bore the fresh scars of their wounds. These wounds, chiefly in the head and neck, could have been received only at close quarters. They were such wounds as a I butcher would inflict, who was attempting to slaughter men as he would slaughter sheep. The evidence of these three, given separately, was mutually consistent, We questioned a fourth witness, the lad Blagoi Petrov, who was released. We were also supplied with the written depositions, backed by photographs showing their injuries, of three other wounded survivors of the massacre, who had found refuge in distant parts of Bulgaria which we were unable to visit. (See Appendix D, Nos. 56, 57, 58.) Among these was George Belev, a Protestant, to whose honesty and high character the American missionaries of Samakov paid a high tribute. The written depositions of the two men who escaped by rushing the sentinels, afforded another element of confirmation. Dr. Klugmann's evidence, given to us in person, is valuable as a description of the way in which the Bulgarian civilians of Serres were hunted down and arrested. The Commission finds this evidence irresistible, and is forced to conclude that a massacre of Bulgarians to the number of about two hundred, most of them inoffensive and noncombatant civilians, was carried out in Serres by the Greek militia with revolting cruelty. The victims were arrested and imprisoned under the authority of the Archbishop. It is possible that he may have been misled by his subordinates, and that they may have disobeyed his orders. But the fact that when he visited the prison on Thursday, he assured the survivors that their lives would be spared, suggests that he knew that they were in danger.

The last stage of the episode of Serres began on Friday, the 11th. Partly because they had left large stores of munitions in the town, partly because rumors of the schoolhouse massacre had reached them, the Bulgarians were anx-

91 ![]()

ious to reoccupy the town. Their small detachments had been repulsed and it was with a battalion and a half of 'infantry, a squadron of horse and four guns, that Commandant Kirpikov marched against Serres from Zernovo and at dawn approached the hills which command it. His clear account of his military dispositions will be found in Appendix B (No. 23). He overcame the resistance of the Greek militia posted to the number of about 1,000 men on the hills, without much difficulty. In attempting toward noon to penetrate into the town, his troops met with a heavy fire from several large houses held by the Greeks. Against these he finally used his guns. From noon onward the town was in flames at several points. The commandant does not admit that his shells caused the conflagration, but in this matter probability is against him. One witness, George Belev, states that the schoolhouse was set on fire by a shell. The commandant states further that the Greeks themselves, who were as reckless as the Bulgarians, fired certain houses which contained their own stores of munitions. It is probable that the Bulgarians also set on fire the buildings in which their own stores were housed. Both Greeks and Bulgarians state that a high wind was blowing during the afternoon. Serres was a crowded town, closely built in the oriental fashion, with houses constructed mainly of wood. The summer had been hot and dry. It is not surprising that the town blazed. We must give due weight to the belief universally held by the Greek inhabitants that the town was deliberately set on fire by the Bulgarian troops. The inhabitants for the most part had fled, and few of them saw what happened; but one eye witness states that the soldiers used petroleum and acted on a systematic plan. This witness (quoted in Appendix B, No. 17) is a local Turk who had taken service under the Bulgarians as a police officer while they were still at war with his country. That is not a record which inspires confidence. On the other hand, Dr. Yankov, a legal official who accompanied the Bulgarian troops, states that he personally made efforts to check the flames.

The general impression conveyed by all the evidence before us, and especially that of the Russian Dr. Laznev (see Appendix D, No. 57), is that the Bulgarian troops were hotly engaged throughout the afternoon, first with the Greek militia and then with the main Greek army. The Greek forces advanced in large numbers and with artillery from two directions to relieve the town, and compelled the Bulgarians to retreat before sundown. Their shells also fell in the town. The Bulgarians were not in undisturbed possession for so much as an hour, and it is difficult to believe that they can have had leisure for much systematic incendiarism. On the other hand, it is indisputable that some Bulgarian villagers who followed the troops did deliberately burn houses (see evidence of Lazar Tomov, Appendix B, No. 25), and that a mob comprised partly of Bulgarians and partly of Turks pillaged and burned while the troops were fighting. It is probable that some of the Bulgarian troops, who seem to have been, as at Doxato, a very mixed force which included some pomak (Moslem) levies, joined in this work.

92 ![]()

The Bulgarians knew that the Greeks were burning their villages, and some of them had heard of the schoolhouse massacre. Any soldiers in the world would think of vengeance under these conditions. In two notorious instances leading residents were blackmailed. The experiences of Mr. Zlatkos, the Greek gentleman who acts as Austro-Hungarian consul, are related in Appendix B (No. 17a). His own account must be compared with the Bulgarian version, which suggests that some of his fears were baseless. The action of the Bulgarian commander in shelling the masses of armed peasants outside the town appears to us to have been questionable. Among them there must have been many non-combatant fugitives. His use of artillery against an unfortified town was a still graver abuse of the laws of civilized warfare.

To sum up, we must conclude that the Greek quarter of Serres was burned by the Bulgarians in the course of their attack on the town, but the evidence before us does not suffice to establish the Greek accusation, that the burning was a part of the plan conceived by the Bulgarian headquarters. But unquestionably the whole conduct both of the attack and of the defense contributed to bring about the conflagration, and some of the attacking force did undoubtedly burn houses. There is, in short, no trustworthy evidence of premeditated or official incendiarism, but the responsibility for the burning of Serres none the less falls mainly upon the Bulgarian army. The result was the destruction of 4,000 out of 6,000 houses, the impoverishment of a large population, and in all likelihood the painful death of many of the aged and infirm, who could not make good their escape. The episode of Serres is deeply discreditable alike to Greeks and Bulgarians.

EVENTS AT DEMIR-HISSAR

The events which took place at Demir-Hissar between the 5th and 10th of July possess a certain importance, because they were used as a pretext for the "reprisals" of the Greek army at the expense of the Bulgarian population. (See King Constantine's telegram. Appendix C, No. 29.) We shall have occasion to point out that the Greek excesses began in and around Kukush some days before the Bulgarian provocation at Demir-Hissar.

That Demir-Hissar was the center of excesses committed on both sides is indisputable. The facts are confused, and the evidence before us more than usually contradictory. This is not surprising in the circumstances. The Bulgarian army, beaten in the south, was fleeing in some disorder through Demir-Hissar to the narrow defile of the Struma above this little town. The Greeks of the town, seeing their confusion, determined to profit by it, took up arms and fell upon the Bulgarian wounded, the baggage trains, and the fugitive peasants. They rose too soon and exposed themselves to Bulgarian reprisals. When the Greek army at length marched in, it found a scene of carnage and horror. The Greek inhabitants had slaughtered defenseless Bulgarians, and the Bulgarian rear guard had exacted vengeance.

93 ![]()

We print in Appendix B (Nos. 27, 27a, 28, 28a) both the Greek and the Bulgarian narratives of this affair. The Greeks as usual suppress all mention of the provocation which the inhabitants had given. The Bulgarian account is silent as to the manner in which their reprisals were carried out. Both narratives contain inaccuracies, and neither of them tells more than a part of the truth. Nor are we satisfied that the whole truth can be reached by the simple method of completing one story by means of the other. The Greek account is the more detailed and definite of the two for the simple reason that the Greeks remained in possession of the town, and were able to count and identify their dead. The Bulgarians believe that about 250 of their countrymen, wounded soldiers, military bakers, and peasant fugitives, were slaughtered there. It may be so, but the total is conjectural, and no list can possibly be furnished. The Greeks, on the other hand, have compiled a list of seventy-one inhabitants of Demir-Hissar who were killed by the Bulgarians. We do not question the accuracy of this list. But there is no means of ascertaining how many of these dead Greeks were killed during the fighting in the streets; how many were taken with arms in their hands and shot; and how many were summarily executed on suspicion of being the instigators of the rising. Two women and two babies are among the dead. If they were killed in cold blood an "atrocity" was perpetrated, but during a confused day of street fighting they may possibly have been killed by accident.

The case of the Bishop has naturally attracted attention. Of the four Greek Bishops who were said to have been killed in Macedonia, he alone was in fact killed. There is nothing improbable in the Bulgarian statement that he was the leader of the Greek insurgents, nor even in the further allegation that he fired the first shot. The Bishops of Macedonia, whether Greeks or Bulgarians, are always the recognized political heads of-their community; they are often in close touch with the rebel bands, and a young and energetic man will sometimes place himself openly at their head. The Bulgarians allege that the Bishop, a man of forty years of age, fired from his window at their troops. The Greeks admit that he "resisted" arrest. If it is true that he was found with a revolver, from which some cartridges had been fired, there was technical justification for regarding him as a combatant. The hard law of war sanctions the execution of civilians taken with arms in their hands. There is no reason to reject the Greek statement that his body was mutilated, dead or alive. But the Greek assertion that this was done by a certain Captain Bostanov is adequately met by the Bulgarian denial that any such officer exists.

Some of the men in the Greek list of dead were presumably armed inhabitants who engaged in the street fighting. Nine are young men of twenty and thereabouts and some are manual laborers. Clearly these are not "notables" collected for a deliberate massacre. On the other hand, six are men of sixty years and upwards, who are not likely to have been combatants. These leaders of the Greek community were evidently arrested on suspicion of fomenting the out-

94 ![]()

break and summarily "executed." It was a lawless proceeding without form of trial, and the killing was evidently done in the most brutal way. We are far from feeling any certainty regarding the course of events at Demir-Hissar. There was clearly not an unprovoked massacre as the Greeks allege. But there did follow on the cowardly excesses of the Greek inhabitants against the Bulgarian wounded and fugitives, indefensible acts of reprisal, and a lawless and brutal slaughter of men who may have deserved some more regular punishment.

The events at Doxato and Demir-Hissar, with the burning of Serres, form the chief counts in the Greek indictment of the Bulgarians. The other items refer mainly to single acts of violence charged against individuals in many places over a great range of territory. These minor charges we have not investigated, since they rarely involved an accusation against the army as a whole or its superior officers. We regret that we were unable to visit Nigrita, a large village, which was burned during the fighting which raged around it. Many of the inhabitants are said to have perished in the flames. We think it proper to place on record, without any expression of opinion, the Greek belief that this place was deliberately burned by the Bulgarians. We note also the statement made by a Greek soldier in a captured letter (see Appendix C, No. 51) that more than a thousand Bulgarian prisoners were slaughtered there by the Greek army. We have also before us the signed statement of a leading Moslem of the Nigrita district to the effect that after the second war the Greeks drove the Moslems from the surrounding villages with gross violence, because they had been neutral in the conflict, and took possession of their lands and houses.

It remains to mention the charge repeatedly made by some of the diplomatic representatives of Greece in European capitals, that the fingers and ears of women were found in the pockets of captured Bulgarian soldiers. We need hardly insist on the inherent improbability of this vague story. Such relics would soon become a nauseous possession, and a soldier about to surrender would, one supposes, endeavor to throw away such damning evidence of his guilt. The only authority quoted for this accusation is a correspondent of the Times. We saw the gentleman in question at Salonica, a Greek journalist, who was acting as deputy for the Times correspondent. He had the story from Greek soldiers, and did not himself see the fingers and ears. The headquarters of the Greek army, which lost no opportunity of publishing facts likely to damage the Bulgarians, would presumably have published this accusation also, with the necessary details, had it been capable of verification. Until it is backed by further evidence, the story is unworthy of belief.

The case against the Bulgarians which remains after a critical examination of the evidence relating to Doxato, Serres, and Demir-Hissar is sufficiently grave. In each case the Bulgarians acted under provocation, and in each case the accusation is grossly exaggerated, but their reprisals were none the less lawless and unmeasured. It is fair, however, to point out that these three cases,

95 ![]()

even on the worst view

which may be taken of them, are far from supporting the general statements

of some Greek writers, that the Bulgarians in their withdrawal from southern

Macedonia and western Thrace, followed a general policy of devastation

and massacre. They held five considerable Graeco-Turkish towns in this

area and many smaller places-Drama, Kavala, Xanthi, Gumurjina, and Dedeagatch.

In none of these did the Bulgarians burn and massacre, though some acts

of violence occurred. The wrong they did leaves a sinister blot upon their

record, but it must be viewed in its just proportions.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]