|

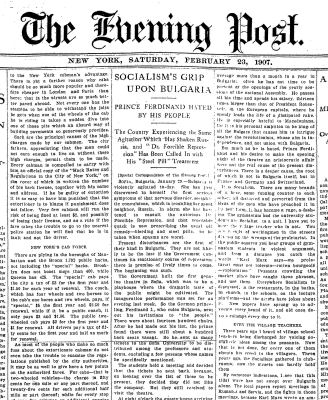

Socialism's Grip upon Bulgaria By Albert Sonnichsen

New York Evening Post (Saturday, February 23, 1907) Saturday supplement Pages 1 to 8

[Special Correspondence of The Evening Post]

Scans as a .pdf file (0.7 Mb) |

Prince Ferdinand hated by his people

The Country Experiencing the Same Agitation Which "Has Shaken Russia, and "Dr. Forcible Repression" Has Been Called In with His "Steel Pill" Treatment

SOFIA, Bulgaria, January 29. — Bulgaria is violently agitated to-day. She has just discovered in herself the first serious symptoms of that nervous disorder, socialistic convulsions, which is troubling her giant neighbor, Russia. In alarm she has hastened to consult the notorious Dr. Forcible Repression, and that venerable quack is now prescribing the usual old remedy — bleeding and steel pills, to be taken when spasms are worst.

Present disturbances are the first of their kind in Bulgaria. They are not likely to be the last if the Government continues its reactionary course of repression; there is promise of lively times to come. The beginning was such.

The Government built the first genuine theatre in Sofia, which was to be a playhouse where the dramatic taste of the public might be cultivated. The inauguration performance was set for an evening last week. So the German princeling, Ferdinand I., who rules Bulgaria, sent out his invitations to ''the people." There were about fourteen hundred chairs. After he had made out his list, the prince found there were still about a hundred back seats vacant. So he sent as many tickets to the Sofia University to be distributed among the professors and students, excluding a few persons whose names he specifically mentioned.

The students held a meeting and decided that the tickets be sent back, because, on looking over the list of those to be present, they decided they did not like the company. But they still resolved to visit the theatre.

At eight o'clock the guests began arriving in carriages. The ministers and their friends came in evening dress and tall hats — a very rare sight in Bulgaria. Their wives blazed with diamonds and bridled in Parisian gowns. There were high officials and military officers, loaded with glittering medals, gold, and silver trimmings, and clanking sabres.

THE CROWDS GATHER.

Meanwhile, thousands of students and factory workingmen had gathered in the street, and in the municipal park opposite, their comments being heard as the occupants of each carriage alighted.

"Ho! There goes the prime minister!!! shouted a student. "Does that high hat fit you better than the fur cap you used to wear?"

"You bureaucrat!" yelled another. "Don't you remember when you carried tripe home on a string from the market?"

The crowd yelled its approval of the remark and set up a shrilling of penny whistles. The prime minister was pale.

"Hurrah! Gel. Ivanoff!" yelled a voice in the crowd. "Does the sword-handle fit your hand better than the plough-handle?"

"Have you got the corns off your hands yet?"

Another thundering roar from the mob, and a storm of whistlings. The general half drew his sword, but stalked in. Then appeared another official who, a decade ago, had been a simple shepherd. The crowd began bleating like sheep, and some barked like dogs.

Suddenly there came a blare of trumpets, a trampling of horses, and the royal carriage arrived, containing Prince Ferdinand and his son, the Crown Prince Boris. The crowd grew silent. The prince was alighting. Then arose a tremendous roar. At first no words were distinguishable, but angry shouts rose above the tumult.

"Down with the prince! Vampire! Bloodsucker! Exploiter! Throw something at him!" -

BAITING A PRINCE.

The prince wheeled at the crowd like an angry wolf, but remembered himself, and hurried into the theatre with his son. A moment later the prime minister appeared, He called to the officer of the royal escort and a gendarme. The cavalry officer turned to his soldiers and shouted: "Sabres, draw! Charge!" And they charged.

Next morning the prince issued a ukase declaring the university closed for six months and all the professors expelled. In the afternoon the largest hall in Sofia, holding several thousand people, was filled to the windows by students, professors, workingmen, and women. The students declared they would come to the university, and the professors that they would teach them; the workingmen cheered their resolutions.

As the meeting broke up a troop of cavalry appeared. Some of the students fired revolvers. The soldiers clubbed right and left, with all the dexterity of Cossacks.

There have been no more demonstrations in Sofia. Every student that could be found was arrested and sent into the provinces. Some were drafted into the Army.

But though Sofia was practicably under martial law, in the province towns the excitement continued. Everywhere meetings are being held to protest against the unconstitutional behavior of the little Germar princeling whom the Bulgarian people detest, but whom Europe forces upon them. And, truly, of an unpopular European rulers, Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria is the most repulsive; in appearance, in character, and in his life.

He is middle-sized and tubby, fond of flashy jewelry and showy uniforms. His eyes are pale gray, high above flabby cheeks that hang in folds, but the most striking feature of his face is his gigantic eagle-beaked nose. Even the touched-up photographs of him, sold to tourists, betray his fondness for eating and drinking.

Prince Ferdinand does not spend on average more than a month in a year in Bulgaria; often he has not time to be present at the openings of the yearly session of the national Assembly. He passes all his time and spends his salary, thirteen times larger than that of President Roosevelt, in the European capitals, where he openly leads the life of a dissipated rake. He is especially hateful to Macedonians, for it is his personal ambition to be king of all the Bulgars that causes him to intrigue against the revolutionists, whose aim is independence, and not union with Bulgaria.

But much as he is hated, Prince Ferdinand and his desire to make the opening night of the theatre an aristocratic affair were not the real cause of the present disturbances. There is a deeper cause, the root of which is not in Bulgaria itself, but in France and Germany and Switzerland.

It is Socialism. There are many brands of it here, some running counter to each other; all distorted and perverted from the ideas of the men who have preached it in its best form. It has become a rage, a fashion. The gymnasium and the university students are Socialist to a unit. I have yet to meet the village teacher who is not. You see crowds of workingmen in the streets discussing the wrongs of the proletariat. In the public squares you hear groups of gymnasium students in violent argument, and from a distance you catch the words "Karl Marx says — we proletariat must not tolerate — rotten bourgeois, — exploration." Peasants crowding the market place have caught these phrases, and use them. Everywhere Socialism is discussed; in the restaurants, in the baths, in church, in the schools, on the lecture platforms — and the actors have jokes about it. New papers have sprung up to advocate every brand of it, and old ones, devote columns every day to it.

EVEN THE VILLAGE TEACHERS.

Three years ago I heard of village school teachers being discharged for voicing socialistic ideas among the peasants. Now that is not done, for every one of them shouts his creed to the villagers. Three years ago, the Socialists gathered in club-rooms; now the streets can hardly hold them.

By numerous indications, I see that this tidal wave has not swept over Bulgaria alone. The local papers report meetings in Rumania and Servia, and the fights in those meetings, because Karl Marx wrote an ambiguous sentence. But, more remarkable still, I meet the young Turks, who come stealing over the frontier, fugitives for calling the Sultan an exploiter. All those I have talked to call themselves Socialists. For a year past there has been a Turkish Socialist organ published in Bulgaria.

The renewed activity of the Turkish revolutionary organization, Young Turkey, proves that its numbers have been increased in Europe, too. A month ago they issued a circular addressed to "Our Christian Compatriots and Brothers," which said:

You are Christians; we are Mussulmans, - but we are all men, exploited alike by Sultan and pashas. Let us throw aside fanatical differences of religion, and join as brothers in the struggle to reconstruct our crumbling state, to save it from the greed of our oppressors, before the hour is too late, and European bureaucrats take the place of the pashas and our task becomes hopeless. Turn away from autocratic Europe, brothers; she will not help you. Put your trust in ourselves, and in a union with us, who will fight beside you, for the same end — independence and the right to shape our own national destiny.

Of course, not even all the leaders of this vast movement have an intelligent idea of what they really want; if they had, princes, kings, and Sultan would meet their end to-morrow. It is much like the Protestant movement in the early days; each strong personality forms a faction.

But they are all possessed of that sublime discontent that leads them on, though blindly, to better conditions. It does not matter that the Reds of Sofia think Socialism means seizing the possessions of the rich and dividing them up: they will never get a chance to do that. But when the Government tries to swindle them out of their votes, they resist furiously.