|

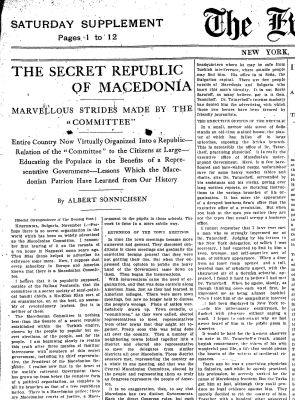

The Secret Republic of Macedonia By Albert Sonnichsen

New York Evening Post (Saturday, November 12, 1904) Saturday supplement Pages 1 to 12

[Special Correspondence of The Evening Post]

Scans as a .pdf file (0.8 Mb) |

Marvellous strides made by the "Committee"

Entire Country Now Virtually Organized Into a Republic — Relation of the "Committee" to the Citizens at Large — Educating the Populace in the Benefits of a Representative Government — Lessons Which the Macedonian Patriots Have Learned from Our History

KUSTENDIL, Bulgaria, November 1. — Perhaps there is no secret organization in the world which has been so widely advertised as the Macedonian Committee. I remember first hearing of it on the veranda of a tea house in Nagasaki some years ago. Then Miss Stone helped to advertise its existence some more. Now, I suppose that every schoolboy in Europe and America knows that there is a Macedonian Committee.

I believe that it is popularly supposed, outside of the Balkan Peninsula that the committee is a secret society of semi-political bandit chiefs, a Ku-Klux Klan sort of an organization, or, at the best, an assembly of revolutionary leaders. But it is neither of these.

The Macedonian Committee, is nothing less than the Senate of a secret republic established within the Turkish empire, chosen by the people by popular but secret elections, of the people, and for the people. I am beginning slowly to realize this truth after three months of familiar intercourse with members of this secret government, including its chief representative, the President of the Macedonian Republic. I realize now that in the heart of the world's rottenest Government there has grown up from below the complete form of a political organization, as complete in all its branches as that of a free republican nation. There is a Macedonian police; there are Macedonian courts of justice, a Macedonian militia, Macedonian schools and newspapers, and a Macedonian postal service, all existing in spite of the regular, recognized Government's mightiest efforts to destroy them.

DEMOCRACY BRED OF OPPRESSION.

Oppression breeds democracy among a people; this truth is strongly illustrated here in Macedonia and free Bulgaria, where the people are intensely democratic. But even ignorant democracy cannot organize political machines. The magic wand of education must strike the pregnant mass before it can form. It was America that applied the touch. What the committee stands for, all built up on thoroughly American principles, is mainly the result of American schools, of American education.

Fifty years ago the Macedonians were a people among whom education was unknown; their minds were on a level with the soil they tilled. They were submissive to their Moslem masters because they did not realize that resistance could bring them something better. For all they knew, it was a law of nature that Islam must rule Christianity all over the world. They were ideal slaves and the Turks liked them, because they were obedient. In those days there were no insurrections, nor were there massacres, for they were valuable slaves.

Then came the Americans, first as missionaries, but gradually developing into schoolteachers as well. They planted the first ideas of liberty and equal rights among the Macedonians. Now every Macedonian peasant knows more about American political institutions than the average Englishman.

In 1858 an American school was founded in Turkey in the vilayet of Adrianople. It was only the first of many others that followed; even up north, in what is now free Bulgaria, they sprang up. Thirty years ago two Americans came to Constantinople, where they founded an American college. Every year this institution, Robert College, has turned out between one and two hundred graduates, among whom Bulgaria has found some of her ablest statesmen. This is what the famous English journalist, W. T. Stead, editor of the Review of Reviews, said of Robert College three years ago:

"They have insisted that every student within their walls shall be thoroughly trained on American principles, which, since they were imported by the men of the May-Bower, have well nigh made the tour of the world. That was their line, and they have stuck to it now for thirty years. With what result? That American college is today the chief hope of the future of the millions who inhabit the Sultan's dominions. They have two hundred students in the college to-day, but they have trained and sent out into the world thousands of bright, brainy young fellows who have carried the leaven of the American town meeting into all the provinces of the Ottoman empire."

There, in Robert College, and in the numerous minor American schools throughout Turkey, was born the movement that has produced the Macedonian Committee. It was the town meetings that did it. The American college graduates who went to teach the village schools in the provinces were the moving spirits of those secret town meetings. Thus they communicated the new ideas to the many who could not go to the American schools. This is so recognized a fact that to the Turks the word "schoolmaster" has became synonymous to the word "comitaji," or revolutionist. And even the Turkish ambassador in Washington has repeatedly protested against the American schoolteachers as the fomenters of insurrection among the Christians of Turkey. In reply the directors of those schools each time effectively prove that never has one word been spoken against the Sultan's Government to the pupils in those schools. The work is done in a more subtle way.

EXTENSION OF THE TOWN MEETINGS

In time the town meetings became more numerous and general. They discussed conditions in those meetings and gradually the conviction became general that they were hot getting their due. But when they expressed that opinion in public the heavy hand of the Government came down on them. Then began the insurrections.

With insurrections came the need of organization, and that was done entirely along American lines, just as they had learned in American colleges. There were more town meetings, but now no longer held to discuss the people's wrongs. Plans of action were definitely drawn up. Town councils, or "committees," as they were called, elected representatives to meet representatives from other towns that they might act together. Pretty soon this was being done all over the country. Then a number of neighboring towns joined together into a district and elected one representative to meet the delegates from similar districts all over Macedonia. Those district senators met, representing the country as a whole in one meeting, and that was the Central Macedonian Committee, elected by the people and representing them as truly as Congress represents the people of America.

It is no exaggeration, then, to say that Macedonia has two distinct Governments. Each the direct Congress rules, but each member is responsible for his vote to his constituents; he must vote as they instruct him. The committee cannot of itself declare an insurrection. When such a grave question comes up each delegate goes home to his district and learns the will of his constituents. Then the committee reassembles and votes.

The sole object of the committee has not been Insurrection. One of the first things it did was to establish a judicial system backed by police force. The laws of the Koran make it impossible for a "giaour" to get full justice in a Moslem court, his testimony is not even accepted there. The Turk always gained his case against his Christian neighbor, and in criminal cases the Turk was seldom punished. Now the Macedonian peasant has another source of justice to look to. He appeals to the local committee. In small matters the local committee decides. A demand Is sent to the Turkish offender to make reparation and pay a fine. He usually obeys promptly, for each municipal committee has its own police band in the neighboring mountains, ready to obey its bidding. And outside of I garrisoned towns Mustafa hits a holy horror of the bands.

In big cases, where a Turk has committed an outrage on a woman, or has denounced some member of the committee or the band, and if there is time, the matter is referred to the Central Committee. If the death sentence is passed, the culprit's doom is sent to the local committee. The band is summoned, its members draw lots, and the chosen than is the executioner. Some days after there is a report of murder being done in such and such a village, and the European papers say it is the work of bandits.

Nor is this system always levelled at the Turk. Two Bulgars in dispute invariably appeal to the committee before the Turkish courts. A Bulgar who has committed an offence against his neighbor gets his trial as well, and is punished. Nor are all Turks enemies of the system. American schools have had some little effect on them, too, as is proven by that big reform party, Young Turkey. There have been cases where Turks have appealed to the committee for redress, in preference to the corrupt courts of their own people.

Spies and traitors are most severely punished, for the big sums of money which the Turkish Government offers for information is tempting to many. But there have been just as many Christian traitors as Turkish spies. The Turkish peasants by no means hate the committee. The fight is between the two Governments, between the bandsmen and the regular soldiers.

There is an underground mail system established throughput all Macedonia which is better than the Turkish official post. A friend of mine in Salonica mailed me two letters at the same time, One by Turkish post, the other by the committee's courier system. The latter reached me twenty-four hours sooner. These couriers also act as guides to those travelling in unfamiliar districts oh business for tile committee. They know all the short cuts through the mountains, add they can always avoid the Turkish scouting parties. Through them, also, information of every movement of Turkish troops is supplied to every local committee in the land within a few days, and, incidentally, to the members of the Central Committee. Thus they can always choose upon a .favorable spot in which to meet.

Founded on American principles as it is, it is only natural that the committee should have its chief executive representing in his person the people of Macedonia as a whole. And so it has. He does dot rule them; he obeys their will, and deals with such situations as many arise on which there is no time to vote. He must have his permanent headquarters where he may be safe from Turkish interference, where outside people may find him. His office is in Sofia, the Bulgarian capital. There are few people outside of Macedonia and Bulgaria who know this man's identity. It is not Boris Sarafoff, as many believe, nor is it Gen. Tsoncheff. Dr. Tatarcheff's intense modesty has denied him the advertising, with which those two heroes have been favored by friendly journalists.

THE EXECUTIVE OFFICES OF THE REPUBLIC

In a small, narrow side street of Sofia stands an old-time stained house, the plaster of which has fallen off in large splotches, exposing the bricks beneath. This is ostensibly the office of Dr. Tatarcheff, practising physician. It is realty the executive office of Macedonia's underground Government. Here, in a few bare-floored and bare-walled rooms, unfurnished save for some heavy wooden tables and chairs, sits Dr. Tatarcheff, surrounded by his assistants and his clerks, poring over long written reports, or dictating instructions to the various branches of his organization. It has more the appearance of a decayed business firm's office than the executive office of a revolution. But when you look at the men you notice they are not the types that usually occupy a business office.

I cannot remember that I have ever met a man who so strongly impressed me as Dr. Tatarcheff. Judging by his letters to the New York delegation, of which I was secretary, I had expected to find in him a keen, brusque, and self-assertive sort of man of military appearance. When a door from an inner room opened and a tall, bearded man of scholarly aspect, with the abstracted air of a German scientist, appeared, I found it hard to believe I had met Dr. Tatarcheff. When he spoke, slowly, as though thinking over each word first, he impressed me as being almost bashful. When I told him of the sympathetic interest that had been displayed in New York towards his unfortunate countrymen, he flushed with pleasure without saying a word. I began to understand why we had never heard of him in the public press in America.

It would be hard for the keenest observer to note in Dr. Tatarcheff's frank, almost boyish countenance, the traces of his own wonderful past life, a life that would please the hearts of the writers of mediaeval romances.

Year's ago he was a practising physician in Salonica, and while he openly practised his profession, he secretly worked for the cause of Macedonian freedom. But the Turks got him at last, although they could produce no legal evidence against him. They merely decided to rid the country of him. Together with a hundred other suspected revolutionists, big heavy chains dangling from his wrists to his ankles, he was marched through the streets of Salonica to the steamer landing, where the exiles for Asia Minor embark. I was told by an eye witness how he burst out into a revolutionary song, and the others roared the chorus, in spite of blows from the gun butts of the Albanian guards.

After a long period of hardship and sufferings in the wailed towns of Asia Minor, Europe, after the Armenian massacres, forced the Sultan to proclaim a general amnesty, and Dr. Tatarcheff was set at liberty. But he dared not return to Salonica. He was assured by a Greek consul that in Greece he would be kindly received. So he sailed to Athens. But although the Greeks hate the Turks cordially, they hate the Macedonian Bulgars one degree more, because they combat the Greek propaganda in Macedonia. Dr. Tatarcheff was known as a member of the committee, and his friend the Greek consul sent word ahead that he was coming on to Athens. When the refugee landed he was arrested and thrown into prison in the city of the old philosophers. At first there was no specific charge against him, but finally he was accused of having murdered a Greek physician in Salonica some years before, through motives of professional jealousy. The charge was so preposterous that even the Turks laughed at it. Macedonian Bulgars brought the case before the Bulgarian Government, and a protest was made at once. Free Bulgaria demanded Dr. Tatarcheff's release.

Then the committee took a hand — Deltcheff was alive then. They did not fear that he would be officially tried and found guilty; they suspected other methods. A note was sent by the committee to the Greek Government, which practically read:

HOW DR. TATARCHEFF WAS FREED.

"If Dr. Tatarcheff, who is now imprisoned in Athens, should by any cause die in prison or in any other way disappear, each hair of his beard shall represent a Greek grave in Macedonia " At the same time the Bulgarian Government pushed its protests so far that relations became strained, and there was popular talk of war. Then the Greek Government was forced to release Dr. Tatarcheff.

From Athens he came on to Sofia, the Bulgarian capital, and there he has been ever since, save for occasional trips to Macedonia, as the "comitajs" travel, with steel passports last year Macedonia's great leader and organizer. Goetze Deltcheff, was killed in battle. Since, then Tatarcheff has been the head.

For reasons already stated, the outside world has popularly supposed Boris Sarafoff to be the representative of revolutionary Macedonia Years ago that was true, but now Sarafoff does hot stand so solid with the committee. He no more represents Macedonia than Forrest or Morgan represented the Confederacy in 1863. He is a brilliant guerrilla fighter, but he has little voice in the councils of the committee. Intelligent Macedonians are beginning to realize that continuous guerrilla warfare will not gain Macedonia her liberty, and, besides, Sarafoff has shown himself a than of little self-restraint at times. He is ambitious, and his ambitions do not always point along the same course with Macedonia's best interests. And lately he has lost much of his popularity. Now it may be said that Dr. Tatarcheff, the scholar, the man who looks upon war as the last reasonable resort for his country to appeal to for freedom, is most truly the representative of the Macedonian people. If war must do it, bethinks, let it be one bold stroke, one terrible struggle with a permanent end, and that is what he is now slowly but surely preparing for. That is why there is now quiet in Macedonia.