|

THE CASE FOR AN INDEPENDENT MACEDONIA

Albert Sonnichsen

Scans as a .pdf file (2.5 Mb) |

(Geographical - The Land. - People in Relation to the Land. - Races Constituting Population. - Occupations. - How the People live. - Temperamental Qualities of the People. - Religion. - Education.) 2

(b) Comment on Histories and Literature on the Subject. 13

(c) Personal Narrative. 14

(d) Forms of Government. 14

IV. Proposals for Settlement 14

VI. The Question of Guarantee 17

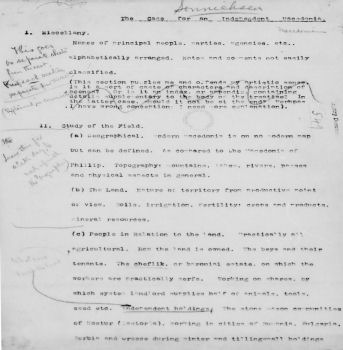

I. Miscellany

Names of principal people, parties, agencies, etc., alphabetically arranged. Notes and comments not easily classified.

(This section puzzles me and offends my artistic sense. It is a sort of cast of characters and description of scenes? Or is it an index, or appendix, containing details supplementary to the body of the treatise? In the latter case, should it not be at the end? Perhaps I have wrong conception: I need more explanation).

II. Study of the Field

(a) Geographical. Modern Macedonia is on no modern map but can be defined. As compared to the Macedonia of Phillip. Topography: mountains, lakes, rivers, passes and physical aspects in general.

(b) The Land. Nature or territory from productive point of view. Soils, irrigation, fertility: crops and products, mineral resources.

(c) People in Relation to the Land: Practically all agricultural. How the land in owned. The beys and their tenants. The cheflik, or baronial estate, on which workers are practically serfs. Working on shares, by which system landlord supplies half of animals, tools, seed etc. Independent holdings; The stone mason communities of Kostur (Castoria), working in cities of Rumania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece during winter and tilling small holdings in summer. Wandering pastoral communities.

(d) Races Constituting Population. Slavs: Bulgars, Serbs, Pomacs and large portion of Turks. Latins: Vlachs, or Wallachs. Albanians, Jews and Gipsies. Origin, language, or dialects, of each. Various estimates as to number of each race, or nationality.

(e) Occupations. The people are almost entirely devoted to agriculture. Bulgars, Pomacs, Turks and Serbs constitute peasantry. The Greeks are the traders in the large centers and the fishermen along the coast, also including a few peasant communities near Salonika. Vlachs are pastoral nomads and produce cheese and wool. Albanians have no communities in territory under consideration, but are wandering traders and clerks in government offices, etc. Gipsies are iron workers, village blacksmiths. Fee Jews are found outside Monastir, Serres and Salnika, and except in latter city, where are majority of population and cover all trades, they are usually merchants.

(f) How the People live. Village life. Construction of houses, from the two storeyed stone houses of Kostur to wattled huts of the Vlach nomads. Housing in

![]()

3

Monastir. House furnishings, etc. What the people ear. Family fire; monogamy the rule and strict observance of chastity by both sexes.

(g) Temperamental Qualities of the People

(Here my personal knowledge is largely confined to Bulgars, the only ones with whom I could hold conversation and with whom I came most in contact. I could also speak with the Jews, in Spanish, but saw little of them in Macedonia, but was intimately acquainted with them in Bulgaria.)

Bulgars very tolerant of other races, but suspicious of strangers. Absence of nationalist feelings, but strong love of the land. Dogged, stubborn, and no respect for authority, as such. The intellectuals, students and village schoolmasters, inclined toward socialism. But their idealism is less abstract than that of the Russians, whom they resemble in many regards. The Greeks: fanatical chauvinism of the intellectuals – their ancestor worship. Intollerant of all other nationalities, whom they term “kondricephalous,” meaning “blockheads,” a term that has become a slang expression among all peoples of the Balkans. The Turks: kindly, normally tolerant, ignorant, and susceptible to religious fanaticism when stirred from higher up. The Albanians: loyal, rough, simple, given to furious outbursts of savagery. Resemblance to Highlanders of the Jacobite period. Divided into Gegi and Toski, the latter, or the north, being more enlightened.

(h) Religion. Simple faith of the Turks. Christianity among the Albanians. The Pomacs: Bulgars who are divided from the rest of the Bulgars by their religion and from the Turks by their speech. Religious fanaticism of the Greeks, not so much a question of faith as loyalty to the Church, a national institution. Bulgars indifferent, though peasantry not quite heretical. Bulgar intellectuals always atheists, as compared to Greek intellectuals, who never are. Temporal power of the Greek Church. Originally had complete sway over all Christian subjects of the Sultan. Bulgar sessession, followed by Vlachs. The Greek church attempts to counteract this tendency by means of terrorism. The massacre of Zagoritchni as an illustration. Attitude of the various churches toward the revolutionary struggle will be more extensively treated under historical section, “Bulgarophone Greeks,” or Greckomans.

(i) Education. Schools officially under jurisdiction of Greek Patriarch in the beginning. Later, when the

![]()

5

Bulgarian was accorded recognition, a few Bulgar communities were allowed to establish schools in which Bulgarian was taught. But in southwestern sections, about Monastir, all Christian communities had either to accept Greek schoolmasters, or none at all. The majority chose the latter course, especially after the insurrection of 1904, when the Greek schoolmasters and priests proved themselves spies for the Turks. “Karahoul” schools, or secret classes, wherein pupils took turns watching for approach of Turkish soldiers or other strangers from hill tops, while their mates attended secret class. Schoolmistresses disguised as peasant women, ready to turn to washing or cooking on approach of strangers. Higher education in Monastir. Serbian and Rumanian subsidized schools.

III. History and Politics.

(This, I think, should begin with a brief sketch of general Balkan history after the Treaty of Berlin. The stubbornness with which Bulgaria, under Stamboulov, resisted Russian intrigues, is extremely good substantiation on my argument for an independent Macedonia, showing the capacity of the people for self government and how all the races unite under democratic government, as they did in Bulgaria. The Serbian war of 1884 also shows basis for Bulgar hatred of Austria and kindliness toward England. I want to give a basis to my argument that Bulgars are all naturally pro-Ally and anti-German. Also want to show that Bulgaria was only Continental nation which never gave way to Russian

![]()

6

Government’s pressure to persecute refugees. Sofia University was founded by Russian exile, Dragomanov, and large part of faculty was composed of Russian exiles.

Young Macedonians come to Bulgaria to finish their education and return with socialistic or revolutionary ideas. Become schoolteachers in villages after Exarch is allowed to open Bulgarian schools.

Gotze Delchev and Damian Gruev, found the “Macedonian Committee” in the early nineties. Little notice taken of the Committee by outsiders in the beginning. Its policy, economic, rather than military; evolutionary, rather than revolutionary. Its immediate object was to establish order under Turkish anarchy by such means as the extinction of brigandage, regulation of relations between landlords and tenants, etc. “Macedonia for the Macedonians” adopted as a slogan from the beginning, because the founders, who were socialists, wanted to include all elements of the population.

Greek Church first to react against the organization. Calls attention of Turkish government to fact that “Bulgars” are organizing. Turks inclined to close their eyes to

![]()

7

Development of what they think is a movement against influence of Greek Church. Greek Church excommunicates members of the Committee, and Greeks leave it.

Progress of the Committee, or “Adrianopolitan and Macedonian Revolutionary Organization;” it becomes an underground, democratic government, based on universal suffrage. How authority is vested in committees, and never in individuals. Village, county, provincial and Central Committee. Annual congresses.

It is decided to establish a department of foreign affairs, technically known as the “beyond the frontier committee,” whose purpose is to represent the organization to foreign governments, explain aims and to collect funds. Boris Sarafov is chosen as chief of this committee, with headquarters in Sofia. He is corrupted by Prince Ferdinand. Their mutual understanding. Sarafov’s high handed method in collecting contributions for the cause, backed by Bulgarian police. Sarafov causes the assassination of a Rumanian journalist who has criticized his methods in Bucharest. The Rumanian government demands his arrest and moves troops toward the Danube. Sarafov is arrested. The interior organization makes an investigation

![]()

8

and strongly condemns Sarafov’s methods, though still unaware of his understanding with Ferdinand.

At this juncture, before Sarafov’s successor can be appointed, occurs the famous Salonika betrayal, followed by the arrest of nearly all the principal leaders of the interior organization by the Turks. Astounding revelations as to widespread scope of the movement attracts attention of all Europe, especially of Greece, Serbia and Turkish government.

Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria begin sending propagandist bands across the frontier, to arouse “national spirit” of the Macedonians. Warfare between these bands and the armed bands of the Committee. At the same time Ferdinand quietly takes possession of the office, machinery and official organ of the “beyond the frontier committee,” and installs therein his own creature, General Tsonchev. Macedonians in the Bulgaria, numbering some 50,000, believe he is backed by interior organization.

The interior organization bands resist the invaders. The Greeks and Serbs are held back. But Ferdinand’s bands

![]()

9

make progress. The Macedonians fighting them have few arms and little ammunition, though they are backed by the populace. Sandanski and Tschernopeev the two most important chiefs opposed to the Bulgarian forces. They are driven back.

The Miss Stone affair. The money so raised saves Macedonia from Ferdinand and reestablishes the interior organization. European pressure forces a general amnesty and the leaders return after the Miss Stone affair.

Ferdinand determines to precipitate affairs. Sends Tsonchev across the frontier with a large force of filibusters and starts an uprising in Razlog caza. It fails, through lack of support by Macedonian peasantry. Next year, in 1904, the Committee precipitates an uprising in Monastir, to attract attention of Great Powers to Macedonian conditions. It is put down with severity. The reforms, foreign gendarmerie officers etc. At this juncture, during Monastir uprising, Sarafov, who has been taking vacation abroad, returns and offers his service as a military man to the Committee. He serves under Gruev’s command in Monastir with great gallantry and is forgiven for past misconduct.

![]()

10

The Monastir uprising is a failure, not only in a military sense, but in its diplomatic aims, failure of the reforms. Reconstruction. A new beyond the frontier committee is established in Sofia and a strong publicity campaign compels Ferdinand to change his tactics. Tsonchev recalls his bands.

Sarafov, protesting his loyalty to “Macedonia for the Macedonians,” is made “revizor”, or literally inspector, for the organization. Meanwhile, however, through his powerful personality, he has gained a following among the younger members. He begins sending armed bands across the frontier ostensibly subject to the orders of the Central Committee, but composed of young Macedonians who he has corrupted, either with money or favors, or with visions of a “Greater Bulgaria.” He is facilitated in this course by the ease with which he is able to procure manlicher rifles and ammunition. The older leaders realize that he has been again corrupted by Ferdinand, but can only agitate against him, on account of his popularity.

The matter is brought to an issue at the Congress, held in the Rilo Mountains, in 1906. Sarafov again protests his innocence of relations with Ferdinand. He is again elected

![]()

11

revizor, being paired with Garvanov, a leader known to be anti-Ferdinand, who is expected to act as a check on him. Partnership shown at this Congress. Questions at issue, “Evolution versus Revolution;” “Centralization versus Loose Federation.” Sandanski represents the socialistic party, which favors evolution, loose federation and is against a Greater Bulgaria. At his juncture Gruev is killed. He was against Sarafov, but not in favor of expelling him from the organization.

Sarafov corrupts Garvanov, his mate. Whereupon Sandanski has him assasinated in Sofia, at the same time sending a stern warning to Ferdinand to interfere no more in interior Macedonian politics.

The rise of Young Turkey: relations between Young Turks and Committee. Young Turk Revolution. Committee leaders join the Salonika Young Turk Committee. Sandanski heads Young Turk army into Constantinople and helps depose Abdul Hamid. But Young Turks are overwhelmed by reaction by masses of Asiatic Turkey. Sandanski and his colleagues return to the mountains.

![]()

12

Sandanski is approached by agent of Ferdinand, who promises a free, or independent Macedonia, backed by Bulgaria and Serbia, if he will join in military campaign against Turkey. The Committee, Macedonian underground government, becomes one of the Balkan allies against the Turks. Sandanski takes command of the guerella forces protecting the Bulgarian flanks against Turkish troops.

Austria’s interference, demanding an “independent” Albania, causes Serbia and Greece to demand a rearrangement of the treaty on which the war was fought. The Macedonians strongly object to either Greece or Serbia getting any portion of Macedonia. Sandanski’s influence, backed by the Macedonians in the Bulgarian army and government office, in precipitating the Second Balkan War.

The Treaty of Bucharest. Serbia and Greece begin nationalizing their portions of conquered territory.

Outbreak of the present war. Sandanski opposed to Ferdinand’s pro-German policy. Ferdinand has him assasinated and jails his sympathizers. Ferdinand swings Bulgaria over to Central Powers solely on Macedonian issue.

![]()

13

He is unable to lend his German allies a single Bulgarian soldier on any front not on Bulgar soil, or what the people consider Bulgar soil (Dobrudja is Bulgar by population).

In spite of this there is strong opposition still, which broke out no later than last year (1916), so violently that hundreds of leaders were executed.

(b) Comment on Histories and Literature on the Subject

(These I would have to go over again to refresh my memory. But I should judge that nine out of ten books on the Balkans are the results of superficial observation, all the more superficial on account of the restrictions which the Turks placed on foreign travelers. And of all these books on travel few treat of Macedonia itself, as that was the turbulent region and travelers were unable to penetrate the country at all.

Then there are the books treating of the political aspect. Those written by natives; Greeks, Serbs or Bulgars, are absolutely worthless as sources of accurate information, as will be obvious when comparing them. The Greek literature is especially untrustworthy.

Books written by foreigners. These, too, are unsafe because the facts were gathered from intensely prejudiced and interested sources, such as the official records of the Balkan governments. They are all incomplete. As an instance, there is not one book presenting the revolutionary struggle in Macedonia other than as organized brigandage. Books on Bulgaria are either violently pro- or anti-Bulgarian. On the economic or commercial aspects I believe the Austrian Government has published some rather trustworthy facts; the only accurate maps of the Balkans are Austrian. The London Balkan Committee published a great deal of material, but they suffered from too much neutrality. By that I mean that they glossed over the defects of all the parties concerned, except those of the Turks, to the extent of ignoring entirely then very important reasons for the antagonism between Bulgars and Greeks. Also, they were inclined to ignore the revolutionary struggle.)

On internal conditions in Macedonia itself I think I am safe in saying that there is absolutely no literature of an informative nature.

![]()

14

(c) Personal Narrative.

This, I suppose, would include a sort of a report on my travels among the villages, to indicate their race character. As a matter of fact, my line of travel constitutes a pretty accurate boundary line of the Committee’s territory, for I walked along the outer edge. Beyond were Greeks, Albanians or Grecomans. We must have a large scale map showing my route, with perhaps color indications of villages along the way.

(d) Forms of Government.

Nature of Turkish government in Macedonia. Negatively bad, except during uprisings. Trouble was there was too little of it, rather than too much. Some villages never saw a Turk, except the tax gatherer and his escort, during many years.

Bulgarian government. This is covered in the historical section, also Serbia and Greece, in describing activity of propaganda bands.

European Powers.

Does this mean their attitude toward the revolutionary efforts of the Macedonians? This needs discussion.

Internal or local. Does this not come under “Turkish government?”

![]()

15

IV. Proposals for Settlement.

Six possible settlements considered:

(1). Macedonia divided between Serbia and Greece.

Various measures for mitigation of situation on native Macedonians. United States might insist upon prevention on “colonization” system, whereby Serbs or Greeks are imported and settled and encouraged to terrorize natives into leaving the country and lands, etc. Measures for communal autonomy. International commission or board to review all sales of land. Native courts of justice. Native school boards.

(2). Macedonia divided between Bulgaria and Greece.

Churched to have to territorial jurisdiction in Macedonian territory, first provision to be insisted on. Division of country into sections, or districts, according to race, and each to enjoy local autonomy, especially in matter of schools. Judges locally elected and police locally organized.

(3). Macedonia annexed by Serbia.

This settlement assumes a pretty complete victory for the Allies, in which case the U. S. would be in a position to insist on a larger measure of local autonomy for the population. Why such a settlement would be directly contrary to the principles ennunciated by President Wilson. An autonomous Macedonia, under Serbian government.

(4). Macedonia annexed by Bulgaria.

![]()

16

U. S. should insist on postponement on such a union, or annexation, for at least year, during which the Macedonians should be allowed opportunity to organize themselves, or to reorganize themselves, rather. Should insist on troops or occupation being under Macedonian commanders, of which there are many in the Bulgarian army, etc. etc.

(5). Macedonia as an Independent State.

The ideal settlement. French, British or American troops in occupation for a year, or until a constituent assembly could be called. Boundaries should be fixed by an international commission, or an American commission, preferrably, as more likely to inspire confidence. Community elections in disputed zones. Central Powers would insist on monarchial form of government, which should be resisted.

(6). Macedonia as a Separate Member of a Federal Union of the Balkan States.

This settlement would naturally evolve from a strict application of the policy that “all small nationalities shall have the decision of their own fates in their own hands.” What general conditions throughout the Balkans would be necessary as a basis for such an outcome. Greece perhaps excluded.

(Macedonia as a part of Bulgaria in a federal union of the Balkan states is inconceivable. Conditions favorable to a federal union would not allow such a union. On the contrary. Bulgaria herself would probably split between north and south.

![]()

17

V. Criticism of Proposals.

Objections against 1, 2 and 3, Why they would lead to future trouble, all the sooner because the United States was able to insist on provisions favorable to the condition of the population.

Settlement No. 4 considered, pro and con. Probably outcome of such a settlement favorable to Macedonians.

Criticism of 5. and 6. involving national independence of Macedonia, either alone or as a member of a federal union of Balkan states.

Are they a step backwards? Are the people capable of self government?

Bulgaria’s experience after liberalism as an example from the past. The natural antipathy of the people against the Teutons and the democratization of Russia two big factors in favor of these two settlements, as eliminating outside intrigues, etc. The character of the Macedonians, as illustrated in their organization of the Committee. Illustrated by personal observation, and observations of various authorities.

VI. The Question of Guarantee.

Each settlement taken up separately.

Why guarantees under 1, 2 and 3 are practically impossible. Guarantees in Macedonia have never worked. Real guarantees under these conditions would constitute so much outside authority as to be mutually exclusive on the part on one neighbor against another, in case of an independent Macedonia.

(a) fixing boundaries on basis of nationality.

(b) removing those elements in all the states of the Balkans, which have made for “national expansion.”

![]()

18

(c) encouraging the natural tendency of the peoples in all the states to express themselves through democratic forms of government, from constitutionalism up.

(d) disestablishment of all the churches.

Guarantee against Interference from Great Powers.

(a) strong autonomy for all the Austrian Slavic elements.

(b) elimination of Ferdinand from Bulgaria, (as ...ing his .... support).

(c) democratization of forms of governments in the Balkans.

(d) Balkan Federation of Slavic states.

(e) Internationalization of Constantinople and Salonika.

Guarantees against Internal Disorders.

Occupation of Salonika until Macedonian Government had been organized. There would be no guarantee under first three proposals.