CHAPTER IV

SLAVIC PERSONALITIES IN THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE

The year 717 A.D. marks the last attempt by the army and fleet of the Umayyad Caliphate, and indeed the last serious Arab attempt, to take Constantinople. [1] This action by the Umayyad Caliph, Sulaiman (715-717), [2] whose caliphate was already rife with the dissension which was finally to destroy it and with it the unity of the Arab empire, failed utterly in its objective. [3] The chief architect of this Arab failure was the Byzantine emperor Leo III (717-741). [4] Leo III's victory marks a new era in the history of Byzantium. [5] Not until the coming of the Seljuk Turks in the middle of the eleventh century was the empire again to face the serious threat of total Islamic conquest. [6] Imperial borders were to fluctuate and serious territorial losses were to occur, [7] but Byzantium remained the dominant power in the Mediterranean world. The critical age of Byzantium, when its very survival was open to question, [8] the age of shattering losses [9] and miraculous victories, [10] the age which had begun with the rebellion of Phocas in 602, was now definitely over.

The victory of 717 was not without significance

![]()

86

for the many peoples living within Byzantium's borders. For now day-to-day life within the empire was given a sense of security that it had not seen for over a century. [11] Aside from the stabilization of international conditions during Leo III's reign, [12] there was the advent of Iconoclasm, a movement which under Leo's guidance reflected the leadership of the emperor in matters of faith as well as law. [13] His ability to present himself as Defensor Fidei against Islam [14] may be later contrasted with the patriarch's inability to exclude iconoclasts such as the Paulicians from the framework of Orthodoxy. [15] Even in his forced conversion of the Jews, Leo III's iconoclasm seemed more to be directed toward gaining their influence against icons as supporters of the Mosaic injunction against idols. [16]

Constantine V (741-775), son of Leo III, not only proved an able continuator of his father's policies, but also introduced new elements into the life of Byzantium. [17] It was during Constantine V's active and auspicious reign that the largest Slavic population transfer took place. [18] Further, he focused imperial activities again on the West in a bid to reconquer lost territories. From 756 until his death in 775, the emperor worked relentlessly to destroy the Bulgar State. [19] To achieve this end, he endeavored to draw the Slavs into the Byzantine orbit and away from the Bulgars. [20]

Iconoclasm, Constantine V's other relentless

![]()

87

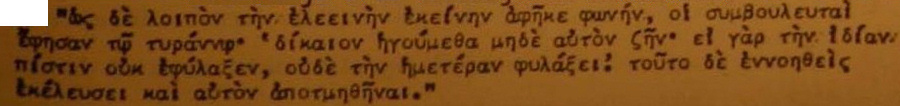

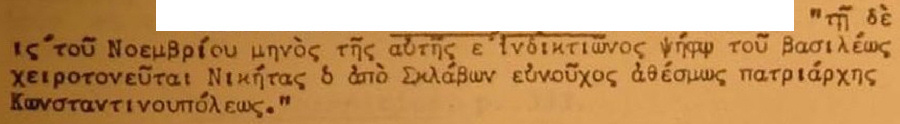

program, saw a significant Slavic addition in no less an ecclesiastical personage than the Patriarch of Constantinople himself. Motivated by political and ecclesiastical reasons, [21] Constantine V created a certain Nicetas, a Slav and a eunuch, [22] Patriarch of Constantinople, a Patriarch equal in standing with the Bishop of Rome, since Constantinople was the "New Rome." [23] Thus the highest ecclesiastical office in the empire was held, from 764 until 780, by a Slav.

What little is known about Nicetas indicates that, unlike several less astute predecessors, he was unquestionably loyal to his emperor. Before his accession to the Patriarchate, Nicetas had served as a Presbyter at the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. [24] Later, his adherence to the emperor's strong iconoclast and antimonastic views earned him, along with his temporal ruler, anathematization in the Acts of the Second Council of Nicea. [25] In spite of the rich epithets and curses heaped upon Iconoclasm, especially on that of Constantine V, neither the vituperous Theophanes [26] nor the more concise Patriarch Nicephorus mentions anything amiss in Nicetas' administration of the patriarchate.

The only close glimpse of this Slavic patriarch comes from the much later pen of Michael Glycas. Nicetas, according to Glycas, enjoyed the pleasures of eating and drinking. [27] When upon occasion he chanted, he did so poorly, due to his inability to pronounce diphthongs.

![]()

88

Once, after his mispronunciation of the name Matthew, [28] it was called to his attention that he separated his vowels. The patriarch's inability to elide his vowels occasioned his somewhat sharp answer regarding this Byzantine's zeal for ecclesiastical detail. Nicetas replied that those around him chattered too much and that in any case his soul had a great hatred for diphthongs and triphthongs. [29]

Glycas' anecdote has a ring of accuracy to it in spite of its eleventh-century authorship. As portrayed by Glycas, the person of Nicetas is that of one raised in a Slavic-speaking environment and later removed to a Greek-speaking one. Difficulty with the Greek of Byzantine chant would be less easily discerned in the twelfth century, since by then the Slavs themselves had acquired facility in chant and ecclesiastical usages. [30] For a Slav of the eighth century, raised in a somewhat new religious and linguistic environment, problems such as mispronunciation and embarrassed anger at correction were not only possible, but also likely to occur. The fact that Nicetas was a unuch in no way disgualified him for high position; on the contrary, it made him desirable for many key positions.

While the iconoclasts were to produce a Slavic patriarch, the iconodules were to acquire a Slavic saint. In the era which reestablished the verity of the icon as n expression of Orthodoxy, [31] a retired military man by the name of Ioannicius the Great [32] led a monastic revival which ultimately touched not only Byzantine Slav, but those

![]()

89

also outside of Byzantium. The entry of Ioannicius into the monastic way of life meant a significant victory for a shaky iconodule regime. [33] It was also particularly important for an age where the forces of monasticism had been seriously depleted by Iconoclasm. [34] Aside from having a bona fide military here to enhance their position, the iconodules gained an energetic monk.

Ioannicius came from the village of Marykates in Bithynia. [35] Evidence for his Bulgaro-Slavic ancestry comes from Constantine VI's (780-797) mention of Ioannicius' family name, the Voiladi. [36] As Professor Sp. Vryonis was the first to point out, it can be demonstrated that Ioannicius was of Bulgar-Slav origin because of the name Voilas. [37] Since his parents' first names were Greek, [38] the Voilas family, by then at least, was fully Byzantinized. It is highly probable that the Voiladi were survivors of Justinian II's transplant and purge.

Ioannicius, after a military career beginning in 773 and ending by 795, settled as a monk at Mt. Olympos in Bithynia. [39] His settlement at Mt. Olympos is hardly surprising, for Olympos had proven to be an intractable hotbed of monasticism throughout the iconoclast era. [40] The monastic movement in Bithynia had already produced saints, George Limneota [41] and the more fanatical Stephanus Iunior. [42] It continued to be an influential center of Byzantine monasticism for many centuries to come. [43] Ioannicius' settlement here indicates not only that Slavic colonists had been

![]()

90

Byzantinized, but were also already deeply involved in the mainstream of Byzantine life. While this member of the Voilas family had been outstanding as a soldier, he gained further fame as a monk, for his monastic activities are cited in several other Vitae. [44]

The relation of Ioannicius to Mt. Olympos and the location of this monastic center in an area heavily populated by people of Slavonic origin was not without significance for later developments. [45] A monastic center such as Mt. Olympos would have been a positive and moving force for the conversion of the Slavs in Bithynia. Interaction between Slavic transplant and the then greatest monastic center in Asia Minor brought results. [46] A monasticism which had been purged by the struggle with Iconoclasm and which converted Slavs settled in Asia Minor was obviously a monasticism capable of work farther afield. While the second phase of the iconoclast struggle was to absorb monastic energies during the early ninth century, [47] Byzantinization of the Slavs in Asia Minor had already taken place. What remained was for Byzantine Christianity to spread beyond imperial borders and into the remainder of the Slavic world.

In this context it is not great wonder that both Constantine and Methodius spent time at the Polychronion Monastery on Mt. Olympos. [48] Here stood the center of a monasticism renowned for its preservation of Orthodoxy. A monk from this great collection of monastic settlements

![]()

91

was already imbued with traditions proven successful in the conversion of Slavonic peoples. Constantine and Methodius satisfied, by their residence on Mt. Olympos, one of the highest aspirations of Byzantine monastic life, impeccable Orthodoxy. Equally important was their experience in Olympian monastic traditions — traditions which were to aid in the conversion of the Slavs, and which had been enhanced less than fifty years before by St. Ioannicus the Great.

The reign of Irene (797-802), famous for its restoration of icons and the revival of monasticism, also witnessed new measures against the Slavs of Greece. This, in part, was the reestablishment of imperial control over such areas as the regions around Thessalonica. [49] Irene's activities were also directed toward Hellas and the Peloponnesus, areas which were inhabited by Slavic tribes [50] that had not been particularly restive. The questions remain why, after Constantine V's successful Slavic policies, this conquest was necessary.

Irene made peace with the Arabs in 783 and then sent Staurikios, Logothete of the Drome, with a large army to subjugate the Slavs. In the words of Theophanes:

Be descended upon the region of Thessalonica and Hellas and subjugated all and made them subject to the empress. He also entered into the Peloponnesus and took many captives and spoils and brought that place under control of the Roman Empire.

Anno Mundi 6276 [784 A.D.]

In this year, in the month of January of the seventh Indiction, the aforementioned Staurikios returned from the territory of the Slavs and led in triumph the victory celebration in the Hippodrome. [51]

This is a marked regression from the diplomacy of Constantine

![]()

92

V, which could induce wholesale defection of Slavs from the Bulgars. It is even more remote from a reign which exerted so much control over Slavic chieftains that even the iconodule Patriarch Nicephorus was forced to record in his Brevarium that:

Constantine released the chieftains of the Slavs and regained those Christians from the islands of Imbros, Tenedos and Samothrace who had been their [the Slavs'] prisoners for a long time. He repaid them with silk robes, their number being about 2,500 and drawing each to himself, he presented each with a small gift and sent them away, each to go where they willed. [52]

Yet Irene was compelled to use considerable military force barely thirteen years later. It is quite likely that Irene's unusually incompetent reign broke the rapport which Constantine V had established between the empire and its Slavic peoples.

Staurikios' campaign against the Slavs did not, however, fully subdue them. Slavic restlessness was to take an interesting turn in 799 when:

In the month of March of the seventh indiction, Akamir, chief of the Velzitian Slavs, was urged by the Helladikoi to liberate the sons of Constantine, and proclaim one of them emperor. When the empress Irene learned of this, she sent to the patrician Constantine Serantapechon his son [i.e., the son of Constantine], Theophylact, who was Spatharius and a nephew of hers. He blinded all involved and overthrew the plot against her. [53]

It should be noted that this was not a rebellion in favor of Slavic autonomy, but an attempt to bring forward a possible legitimate heir to the throne. Akamir was not breaking with Byzantium, but seeking a more influential role within the empire. This seemed impossible under Irene.

![]()

93

Whatever had transpired previous to Irene's reign had now changed, because the Byzantinization of the Peloponnesus was now to rely more upon force than conciliation. [54]

It is most likely that Nicephorus I effected a final consolidation of Byzantine power in the more strategic regions of Byzantine Europe. Theophanes spitefully records that in the year 810:

Nicephorus, with godlessness, moved the soldiers — in everything seeing to it that Christians were humiliated. He moved them out of every Theme and arranged them in the Sklavinias as fell their lot. [55]

Thus, Nicephorus I secured the Sklavinias for Byzantium. He thereby removed the possibility of further Slavic uprisings in that area while he prepared to conquer Bulgaria. [56]

As has been seen, the reign of Irene was auspicious for monasticism and the rise of St. Ioannicius the Great. The monk St. Ioannicius was not the only member of the Voilas family to acquire standing during the reign of Irene. Another Voilas, Constantine, was, by the year 800, a patrician and a high court functionary. His name appears in a list of Irene's court entourage. His exact function in court is not known, but he was a participant in a spectacle which took place:

On the second day of Easter the empress went to the Church of the Holy Apostles. She was mounted on a golden chariot drawn by four white horses, which were held by four patricians; Vardanes — the Strategos of the Thracesion Theme, Sisinnios — Strategos of Thrace, Nicetaa — Domestic of the Scholarian Guard, and Constantine Violas, all of whom liberally passed out gifts. [57]

Thus established in court and by canonization, the Voilas

![]()

94

family was to continue well into the eleventh century.

By the beginning of the ninth century, Byzantinization of the Slavs settled in Asia Minor was complete enough for one of their number, a certain Thomas, to attempt the ultimate in Byzantine social advancement — the seizure of the imperial throne itself. The attempt was not without a degree of success, for the rebellion stirred up and led by him lasted several years. [58] All but one of the sources maintain Thomas' Slavic origin, although there exists the suggestion that he may have been an Armenian. This suggestion, put forward by H. Grégoire, is based upon the confused commentary of Joseph Genesies. [59]

The roots of the confusion most likely rest in the Eastern origin and support of this rebellion. It is known that Thomas received aid from the Arabs. Also, it is shown by the catalogue of the troops employed by Thomas that the majority of them came from Eastern frontier areas. [60] By this time the Arabs, most probably by way of the Caucasus, had transplanted Slavs on their western frontier in a way similar to that of Constans II. [61] It is possible that Genesios, being aware of Thomas' Slavic origin, had at one point accounted for the eastern nature of the rebellion simply by referring to Thomas as being a Slav from the Armenian frontier area. [62] Part of the reason for such an explanation is the fact that in Asia Minor, the area of maximum Slavic population density, the Opsikion Theme, did not support the rebellion of Thomas. [63] All the other

![]()

95

accounts attest to Thomas' Slavonic origin, and to the fact that he was born in Asia Minor in a Theme neighboring the Opsikion — the Anatolikon. [64]

The lack of rebelliousness by the population of the Armeniakon and Opsikion Themes puts to rest yet another theory. Je. E. Lipšits advanced the theory that the rebellion was led by Thomas and the Slavs in these Themes. [65] While Slavs participated in Thomas' rebellion, aside from Thomas himself, there is no record stating from where his Slavic supporters originated. [66] A claim that the Slavs of Asia Minor were, along with all the other ethnic minorities, rising up against their Byzantine overlords is patently false. These minorities all had members in important positions, the Slavs themselves supplying one patriarch, a monastic leader and a patrician within the previous fifty years. Whatever the actual causes for the rebellion were, they were not those of a Slavic peasant class in Asia Minor as Je. E. Lipšits once proposed. [67] Perhaps, since the rebellion seems to have moved from East to West, it had to do with the complex conditions in the East. Thomas' activities, besides from being the most serious rebellion since that of Artavasdus against Constantine V in 742-743, indicates the breadth of opportunity open to Byzantinized Slavs in Asia Minor. [68]

Whatever the side effects of Thomas' rebellion, they did not inhibit Slavic opportunity for advancement. The Slavs continued to obtain important posts under

![]()

96

subsequent emperors. [69] Perhaps the most important and most dramatic role was played by Damian, the Slavic Paroikomenos to Michael III (842-867). [70] Damian was, by 865, a person to be reckoned with in the imperial court. Through political astuteness he had risen to the rank of patrician, but now his skill as a politician was to achieve far more important objectives. In 857 he was a leading participant in the removal of Theoctistus and Theodora from the imperial regency and the accession to power of Michael III under the tutelage of Caesar Vardas. [71] Damian hastened this change of regime by letting Vardas into the city and by helping him seize control of the palace. [72]

Damian's alliance with Caesar Vardas was Damian's undoing. When Vardas, a skilled politician, sought total influence over the young Michael III, it was obvious that the one person who stood in his way was Damian. Vardas, the man most responsible for the renaissance of the University of Constantinople and the author of military effectiveness against the Arabs, [73] was finally successful in having Damian removed. [74] The pretext used by Vardas to set Damian aside was Damian's failure to rise in honor when Vardas was wearing the purple Skaramangion, an important imperial badge of rank. This, by Vardas' suggestion, was an act of Majestas. [75] Michael II, persuaded by the accusation, commanded his chamberlain, Maximian, to remove Damian immediately. Maximian, then, under imperial orders, brought Damian to the marketplace of St. Mamas, shaved his head,

![]()

97

and, placing him under guard, made him a monk. [76]

The sequel to Vardas' action was to prove disastrous for him. On the day that Damian was removed from office, a certain Basil, then Protostrator, was elevated to the position of Paroikomenos. [77] This Basil was the future emperor Basil I. If Damian was a stumbling block to Vardas' ambitions, Basil was fatal for them. As the continuator of Theophanes states:

Caesar [Vardas], perceiving this [i.e., the closeness between Michael III and Basil] was bitten by envy and was very fearful about his future. He accused and found fault in those who had counseled and incited him against Damian. Recalling this as being foolish and ill-advised, he said "You urged me to a decision against what I thought was right — throwing out the fox and introducing a lion instead, so that all of us shall be swallowed and devoured." [78]

The lion, Basil I, soon afterwards, in 866, with his own hand murdered Vardas. Damian, however, survived the murderous intrigues of the court. Having been forced to become a monk, he did well in his new estate. [79] A century and a half later, a pilgrim's guide to the great sights of Constantinople advises the prospective pilgrim to see the monastery built by Damian the Slav, a monument to this Slav's diverse capabilities. [80]

The next Slavs to achieve high court position did not enter or leave in such a respectable or innocent a fashion. During the erratic and fortunately short-lived reign of Alexander (912-913), Gavrielopoulos and Vasilitzes, both Slavs and possibly from Asia Minor, appear as important personages. [81] Their advent marks but one of Alexander's

![]()

98

excesses. They both adapted well to their new and improved circumstances and are known chiefly for their depredation of the imperial fisc. [82] Their deft rascality and skill at this form of personal enrichment gained for them a certain dark distinction in the ranks of Alexander's entourage. Wealth, however, only whetted the appetite of Vasilitzes.

Vasilitzes, cognizant of the poor health of his ruler, attempted to take advantage of Alexander's capricious nature to secure his own future position. By means of persistent suggestion he tried to persuade the emperor to castrate the young Constantine, son of Leo VI (886-912) and heir to the imperial throne, thereby elevating himself to the position of co-emperor. [83] What Thomas the Slav had attempted to take by force, Vasilitzes the Slav attempted to take by stealth. He almost succeeded. As one of the Chronicles states, it was only luck that saved the child Constantine. The advice proferred by the pro-Leo VI faction eventually held sway. At one time they suggested that the child was too young for such an operation; at another time they counseled Alexander that the child was sickly and would die, leaving the succession open in any case. [84]

These constant counterproposals restrained Alexander from taking the steps suggested by Vasilitzes. The death of Alexander in 913 put an end to the careers of both Vasilitzes and Gavrielopoulos, for a clean sweep was made of the palace. The continuator of George Hamartolos states:

![]()

99

Then those who were given command over imperial affairs took office in the palace — Constantine the Paroikomenos, Constantine, and Anastasius nicknamed the Stout; at the suggestion of John Eladas, the household of Alexander were driven out — to wit John the Rector and the aforementioned Gavrielopoulos and Vasilitzes and others. [85]

Thus the careers of the "Slavic fops," as Arethas later called them, ended. [86]

Several years later during the reign of Romanus I Lecapenus (920-944) , members of the famous Voilas family reappeared, this time in plots against the emperor. After the involvement of one Constantine Voilas in court intrigues was quickly foiled by Romanus I, Constantine Voilas soon found himself an unwilling monk at the famous establishment of his ancestor, St. Ioannicius the Great, on Mt. Olympus. [87] The plot of the other member of the Voilas family, Vardas Voilas, was far more serious. A combination of the surname Voilas with the Armenian name Vardas represents a merging of an important Slavic family of Asia Minor with the Armenian aristocracy. [88] The representative of such a combination would have been important on the basis of family background alone, even without official position.

Vardas Voilas, however, had an official position. He was Strategos, military governor of the Chaldean Theme, an important district in the Eastern frontier of the empire. In command of numerous troops, he joined forces with a certain Adrian and a very rich Armenian by the name of Tzantzes. Together they plotted a rebellion against Romanus I. These three, along with their supporters, were initially

![]()

100

successful. They seized a key fortress as a base for their operations. [89] But this good fortune was followed by disaster. Not only was Romanus I an able ruler, he also possessed able and loyal subordinates. The emperor immediately sent John Curcuas, then Domestic of the Scholarian Guard, against the rebels. As other campaigns were to prove, John Curcuas was probably one of the best imperial generals of the tenth century and the driving force behind a new era of Byzantine offensive against the Arabs. [90] Curcuas quickly crushed the rebellion, blinded many of the leaders, and confiscated rebel property. The hapless Vardas Voilas, spared blinding only because he had been a close friend of the emperor, immediately became a monk — a move not without precedent in the Voilas family. [91]

Romanus I Lecapenus proved to have other more loyal Slavic friends. Possibly the most important, as far as the Lecapeni family was concerned, was the Peloponnesian magnate Nicetas Rentakios. Nicetas and his family, deeply involved in Byzantine-Bulgarian relations, were quite influential in Greece. [92] Sofia, Nicetas' daughter, was given in marriage to Christopher, the third son of Romanus I. [93] With a daughter married to the imperial family and possessing substantial personal wealth, Nicetas claimed for himself pure Hellenic lineage. His specious claim was pointed out by the emperor Constantine VII, who declared in a somewhat elliptical remark, that such a claim was difficult in the light of so Slavic a continence. [94]

![]()

101

History was yet to bring about a final irony in relation to the descendants of Nicetas Rentakios. The issue of this marriage between Sophia Rentakios and Christopher Lecapenus, one Maria, played an important role in bringing about peaceful relations between Bulgaria and Byzantium. During the peace negotiations which followed Tsar Simeon's death in 927, it was decided that the new Tsar Peter would marry a princess of the Byzantine imperial family. Since the imperial family at this time was that of the Lecapeni, the daughter of Christopher and Sophia was chosen. In the fall of the year 927, Maria, having changed her name to Irene in order to signify the new peace (Irene = Peace in Greek), was married in Constantinople to Tsar Peter of Bulgaria. [95] In this way the Bulgarian royal family gained a true Byzantine princess not much different in ethnic background from a good number of nubile Bulgarian women.

The true Byzantine prince and heir to the imperial throne, the scholarly Constantine VII, finally attained effective control of the throne in 944, after a thirty-one year minority. Having survived all attempts to remove or replace him, he was to remain the sole ruler until his death in 959. Thanks to his scholarly bent and literary output there exists rich information on the life and politics of tenth-century Byzantium. [96] Included in the mass of Constantine's writings is valuable information of the Slavs within the empire. Of particular interest is his

![]()

102

record of Slavic military achievements. The second part of Constantine VIIʹs De Ceremoniis Aulis, [97] and eclectic storehouse of information on far more than imperial ceremonies, yields important information on Slavic military units from Asia Minor. It is known that, at least from the ninth century, there were troops from the Opsikion Theme called the Slavesians. [98] While it is not possible to prove continuity between the ninth-century inhabitants of the Opsikion called "Slavesians" and the colonists of Justinian II, such is highly possible, Justinian II's massacre notwithstanding. This colony would, of course, have been augmented by Constantine V's transplantation. By the ninth century, the area of the Opsikion Theme did indeed contain people carrying the name "Slavesian," an appelation due most likely to the large numbers of Slavs settled there. [99]

Slavs from an unknown region took part in an expedition to Southern Italy in 880. [100] Later, according to Constantine VII, Slavic troops from the Opsikion Theme participated in the Lombard expedition of 953 and in the Cretan expedition of 949. [101] From Constantine VII's reference it is known that these troops were cavalry, and in the Cretan venture they numbered 220 horsemen as compared to the 1,000 mounted troops from the Anatolikon Theme, militarily the strongest. [102] Such a contingent was important. It testifies to the prosperity of the people in that region, since they could afford to send a contingent of such size, considering how expensive it was to equip

![]()

103

and maintain.

The only combat description which exists for these Slavic troops is in the Italian campaign of 880. Here, under the leadership of Procopius, the imperial Protovestarios, they received a severe setback in savage fighting against the Arabs, but were finally aided by the more successful troops of Leo Apostupes. [103] Their showing was not better or worse than other imperial soldiers. After the expeditions to Italy in 935 and to Crete in 949, the fate of the Slavs in imperial armies is unknown.

One spectacular Arab victory, that at Amorion in 838, was due to a person of possible Slavonic origin, a certain Voiditzes. [104] The name Voaditzes, and the confusion of the sources in explaining this name, indicate that Voiditzes might have been Slavic, since it is a Greek name with a Slavic diminutive ending. [105] Greek names with the "-itzes" formant are quite common, especially in sources like the life of St. Clement Ohrida, where the mixture of Slavonic and Greek is easily recognizable. [106] Even in the Byzantine court, to wit Vasilitzes, the "-itzes" ending played a part. In any case, it was Voiditzes who betrayed Amorion, home of the then reigning imperial dynasty, to the Arab Mutasim. [107] This indeed was a serious blow to the Prestige of the emperor Theophilus (829-842). Voiditzes, like another famous Slav, Nevoulos, was bribed. According to Michael the Syrian, [108] he gained 10,000 Darics for his deed. The hagiographic tradition of the Forty-two Martyrs

![]()

104

of Amorion, stated that Voiditzes did not live to enjoy his perfidiously earned treasures, but was executed in 845 along with those whom he betrayed. [109]

Voiditzes, like many other Slavs within the empire, had achieved an important position and as so many Byzantines, attempted to make the most of it. The history of the Slavs within imperial boundaries during the era 600-1018 provides examples of Slavic penetrations into every facet of Byzantine society. If a Slav had not attained the imperial diadem, it was not for want of trying. Their activity within the empire was that of any other Byzantine citizen. From this record it must be concluded that many Slavs within the empire had made the transition from outsider to citizen. This particular transformation from barbarian to imperial subject and the cultural implications of this, is, as the record of three centuries indicates, an important phenomenon.

105

FOOTNOTES

CHAPTER IV

1. The conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmet II Fatih (1451-1481) marked the success of Turkish rather than Arabic Islam. For this, see F. Babinger, Mehmed der Eroberer und seine Zeit (Munich: F. Oldenbourg, 1953) .

2. K. V. Zetterstein, "Sulaiman," E.I.1, IV, 518-519. Sulaiman (679/80-717) proved unable to lessen the problems which beset the Ommayid Caliphate. The actual attack was led by Maslama ben Abd al-Malik and Omar ben Hubaira. For more on the difficulties surrounding Sulaiman's reign, see M. A. Shaban, Islamic History A.D. 600-750 (A.H. 132): A New Interpretation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp. 112-137.

3. A good summary of the problems which beset the later Ommayids may be found in C. H. Becker, "The Expansion of the Saracens — The East," The Cambridge Medieval History, II (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1936), 362-364.

4. Brooks, "The Campaign of 716-718," pp. 19-33.

5. Ostrogorsky, History2, pp. 156ff.

6. The raid of Harun al-Rashid (786-809) cannot be seen as a real threat to Constantinople despite his success — cf. Toynbee, Constantine Porphyrogenitus, pp. 112-113 .

7. Most important was the loss of Sicily in stages to the Arabs — see Vasiliev, Byzance et les Arabs, I, 61-88, d II, 142-152. More temporary was the loss of Crete — Ibid., I, 49-61.

8. Three attacks during this era were indeed serious enough to have possibly finished the empire. They were the Avar-Persian attack of 626/27, the Arab siege of Constantinople 674-78, and the Arab campaign of 716-718.

9. The loss of Egypt and Palestine to the Persians, their subsequent reconquest by Byzantium, and finally their loss again to the Arabs typifies the nature of Byzantine struggles during the early seventh century. The most recent account of this is

10. The defeat of Persia by Heraclius is the most dramatic change of Byzantine fortunes. See A. Pernice, Lʹimperatore Eraclio. Saggio dl atoria bizantina (Forence: Tipografia Galletti e Cocci 1905), pp. 111-182, and

![]()

106

Στράτος, Τὸ Βυζαάντιον, B., σ. 777-792. Of more lasting success and importance were the two determined defences of Constantinople against the Arabs in 674-678 and 717 (Ostrogorsky, History2, pp. 123-125 and 156-157).

11. Ostrogorsky, History2, pp. 157-160.

12. The repercussions of the 717 attack were particularly deep on the Arab world. The destruction of the Arab array outside of Constantinople undermined the strength of the Ommayid Caliphate by the partial removal of its mainstay, the army of Syria. This weakness on the part of Damascus played into the hands of the dissident elements in Iraq, thereby directing much of the Caliphate's attention elsewhere. For a more complete description of this important development, see Shaban, Islamic History, pp. 100-137.

13. Stephen Gero, Byzantine Iconoclasm During the Reign of Leo III with Particular Attention to the Oriental Sources (Louvain: Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, vol. 346, Subsidia, t. 41, 1973), pp. 48-58.

14. Ibid., pp. 32-47.

15. Ibid., p. 27, n. 11.

16. Bury's explanation (Later Roman Empire to Irene, II, 431) that Leo III's attempt at Conversion of the Jews was to obtain their help in suppression of the icon still remains a feasible theory. Alternative suggestions such as those offered by J. Starr, The Jews in the Byzantine Empire, 641-1204 (Athens: Texte und Forschungen XXX, 1934), pp. 1-10, and J. Scharf, "The Jews, the Montanists and the Emperor Leo III," B.Z., XLIX (1966), 37-46, also deserve serious consideration.

17. As is witnessed by Constantine V's settlement of eastern peoples in 745, 751, and 755. See Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 92-93.

18. For example, the 208,000 Slavs settled in 762 (Nicephorus, Brevarium, 68:27-69:2).

19. Zlatarski, Istorija2, I/1, 261-296, and Beševliev, "Die Feldzüge," pp. 5-17.

20. The defection of 208,000 Slavs hardly seems possible without some form of collusion on the part of Constantine V. Beševliev (ibid., p. 12) aptly remarks on Constantine V's use of agents against the Bulgars. The celerity of the Slav's move to Byzantine lands has all the marks of such an intrigue.

![]()

107

21. The previous patriarch, Constantine II (754-766) , was involved in a plot to overthrow Constantine V. He was executed for his complicity in this plot. See Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 146-147 and 149.

22. Theophanes, Chronographia, 440:11-13,

23. This understanding, while never accepted by Rome, was part of Canon Two of the First Council of Constantinople (381), and was the Byzantine view of the office. See Mansi, III, cols. 559 (Latin) and 560 (Greek), for the exact context of this phrase.

24. Nicephorus, Brevarium, 75:1-2.

25. Theophanes, Chronographia, 463:3, and Mansi, XIII, cols. 399 and 400.

26. On the sources treatment of Constantine V, see Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 10-21.

27. Michael Glycas, Annales, 527:13-528:1, "And then Nicetas, a eunuch, was brought forward by Copronymus. So a man who thought only about eating and drinking was made patriarch."

28. Ibid. , "ἀντὶ τοῦ εἰπεῖν ἐκ τοῦ κατὰ Ματθαῖον "ἐκ τοῦ κατὰ Ματθάϊον" ἔξεφώνησεν."

29. Ibid. , "πρὸς ὅν ἐκεῖνος ἔφη μετὰ θυμοῦ "φλυαρεῖς" τὰ γὰρ ὁίφθογγα καὶ τρίφθογγα πολλὰ μισεῖ ἡ ψυχὴ μου."

30. I.e., after the conversion of the Slavs in the ninth century. Slavic letters, especially in Bulgaria, reached a high point in the tenth century and continued to flourish well into the eleventh. This is best described in I. Dujčev, Iz Starata Bulqarska Knižnina, I (2nd ed.; Sofia: Hemus, 1943), 203-204, and E. Georgiev, Razvetut na Bulgarskata Literatura v IX-X v. (Sofia: B.A.N.. 1962), pp. 3-13 and 29-86.

31. This era was initiated by the regency of Irene beginning in 780. The iconodule position was officially confirmed by the Second Council of Nicea in 787 (Mansi, XII, cols. 951-1154, and XIII, cols. 1-489).

32. A.A.S.S., Nov. II/1 (1894), 332-435; M.P.G., 116, cols. 36-92; and excerpted by W. Weinberger in Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserliche Akademie des Wissenschaften. Hist.-Phil. Klasse, CLIX (1908), 80-85.

![]()

108

33. Vita Ioannicius, pp. 339-342.

34. Constantine V's attack upon monasticism had not been without effect upon the monastic population. See Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 165-167, and P. Charanis, "The Monk as an Element in Byzantine Society," D.O.P., XXV (1971), 66-67.

35. Vita Ioannicius, p. 333.

36. Ibid., p. 338.

37. Vryonis, "St. Ioannicius the Great and the 'Slavsʹ of Bithynia," B., XXXI (1961), 245-248.

38. Ibid., p. 246.

39. Vita Ioannicius, p. 340.

40. There is only one study (unavailable to me) devoted solely to this important monastic center—R. P. B. Menthon, Un terre de legendes, L'Olympe de Bithynie. Ses saints, ses couvents, ses sites (Paris, 1935). A good general account may also be found in F. Dvornik, Le Légendes de Constantin et de Méthode Vues de Byzance (Prague: Byzantinoslavica Supplementa I, 1933), pp. 112-147.

41. Vita Georgius Limneota, A.A.S.S., Aug., IV (1739), 842.

42. Vita Stephanus Iunior Confessor (vel M.), Analecta Graeca, pp. 396-531; M.P.G., 100, cols. 1069-1186.

43. Dvornik, Les Légendes, pp. 112-147.

44. Vita Athanasis heguminae in Aegina insula, A.A.S.S., Aug., III, 173; Vita Eustrati hegumeni, pp. 367-400; and Euthymius iunior, pp. 168-205 + notes and pp. 503-536.

45. Vryonis, "St. Ioannicius," p. 248, for suggestion of other Slavs in Bithynia.

46. I.e., St. Ioannicus the Great.

47. I. Sokolov, Sostojanie monašestva vʹ vizantijskoj cerkvi s poloviny IX do nacala XIII veka (Kazan: Imperatorskago Universiteta, 1894), pp. 45ff., rightly speaks of the year 843 as the date for the permanent revival of monasticism. With the reestablishment of Orthodoxy came a new flourishing of Byzantine monasticism not fully possible during the years of the iconoclast struggle.

![]()

109

48. Malyševskij, "Olimp" na kotorom žili sv. Constantin' i Methodij," Trudy Kievskoj duhovnoj akademii, 1886/III, 549-586 and 1887/I, 265-297; Dvornik, Les Légendes, pp. 114-117 and 210-211; A. S. L'vov, "O prebyvanii Konstantina Filosofa v monastyre Polihron," Sovetskoe slavjanovedenie, XXXV/5 (1971), 80-86; A. E. Tachiaos, "L'origine de Cyrille et de Méthode. Verité et légende danj les sources slaves," Cyrillomethodianum, II (1972-1973), 98-140. For the actual text of the lives, see either F. Griveć and F. Tomsić, Constantinus et Methodius, or Kliment Ohridski, Subrani sučinenia, III.

49. It is difficult to believe that Thessalonica was in any serious danger of Slavic attack after Constantine V's transplantation of population into Thrace (Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 92-94) and his successful wars against Bulgaria, unless it was related to Irene's iconodule policy — a policy unpopular with the more iconoclast military units (N. Garsoian, "Byzantine Heresy. A Reinterpretation," D.O.P., XXV [1971], 97-98).

50. Bon, Le Peloponèse byzantin, pp. 27-70.

51. Theophanes, Chronographia, I, 456:25-457:6.

52. Nicephorus, Brevarium, 76:22-29.

53. Theophanes, Chronographia, 473:32-474:5.

54. B. Bury, A History of the Eastern Roman Empire from the Fall of Irene to the Accession of Basil I (A.D. 802-867) (London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd., 1912), pp. 375-381; Bon, Le Peloponèse, pp. 177-179; M. Ja. Sjuzjumov, "Pervyj Period ikonoborčesta," Istorija Vizantii, II Moscow: Nauk, 1967), 63.

55. Theophanes, Chronographia, 4 86:10-13.

56. For Nicephorus I's activities in other areas of Greece, see P. Charanis, "Nicephorus I the Savior of Greece from the Slavs (810 A.D.)," Byzantina-Metabyzantina, I (1946), 75-92.

57. Theophanes, Chronographia, 474:6-10.

58. I.e., 821-823. The best study is that of Lemerle, "Thomas le Slave," pp. 255-297.

59. Vasiliev, Byzance et les Arabes1, pp. 25-26. This is at variance with Vizantija i Araby, I, 21-43, which states that Thomas was a Slav.

![]()

110

60. Joseph Genesios, Regnum, p. 33 (Bonn). Of the peoples mentioned in this enumeration, 11 are definitely of eastern origin, the other 4 refer to western neighbors of the empire. Vasiliev (Vizantija i Araby, I, 28, n. 4, and Byzance et les Arabes, I, 32, n. 2) discusses this list and makes several conjectures as to the meaning of the more anachronistic names. Taking this into account it is worth noting that 10 (11) of the 13 (14) eastern names identify people then existing, while only 2 of the 4 western names (Slavs and Goths) refer to contemporary peoples.

61. V. V. Barthold, "Slavs," E.I.1, IV, 467-468. Arabic sources explicitly state that these Slavs were imported from Khazaria by way of Khakhetia to the Cilician frontier by Mansur (754-775). See also Niederle, Slovanské Starožitnosti. II/2, 464-467.

62. This is not impossible considering the existence of "The City of the Slavs," Loulon, on the Arab-Byzantine frontier. See above, p. 67.

63. Genesios, Regnum, pp. 32-33.

64. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 50:17-51:1. For more on the subject of Thomas' identity, see J. B. Bury, "The Identity of Thomas the Slavonian," B.Z., I (1892), 55-60; M. Rajković, "O poreklu Tome, vodje ustanka 821-3 g.," Z.R.V.I., II (1953), 33-38; Lemerle, "Thomas le Slave," p. 284.

65. Lipšits, "Vosstanie Fomi Slavjanina," pp. 352-365. Lipšits has made some revision of her original theory in her later work Očerki Istorij, pp. 213-228, but still holds on to many of her 1939 suppositions.

66. Joseph Genesios, Regnum, p. 33, gives no geographical location for the Slavs in Thomas' armies. It is more probable that, in the light of the Opsikion and Anatolikon Themes' loyalty to Michael III, the Slavs referred to are from Thrace where the rebellion ended. It was at this time that the Bulgar Khan Omurtag (813-831) was brought in on the side of Michael III, and helped put an end to this rebellion — Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 64:19-66: 11, and Zlatarski, Istorija2, I/1, 395-396.

67. Lipšits, "Vosstanie Fomi Slavjanina," pp. 352-355.

68. In relation to Iconoclasm, these two rebellions seem strangely similar in their ambiguity. For more on Artavasdus, see Lombard, Constantin V, pp. 22-30.

![]()

126

69. The continued existence of Slavs in high official positions after the collapse of Thomas' rebellion indicates that Slavs were not singled out for reprisals because they were not the central factor in the rebellion as Lipšits hypothesized ("Vosstanie Fomi Slavjanina," pp. 364-369).

70. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 234:7-235:16.

71. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 821:14-822:18.

72. Ibid.,

"Vardas Caesar had a liking for Damian the Patrician and Paroikomenos. He had influence over the emperor and persuaded him to let Vardas enter the city. Vardas, together with the Paroikomenos, by means of gifts from the imperial largesse made a determined advance into the imperial palace."

73. There exists no study devoted to Caesar Vardas, the men who played so important and tragic a role in imperial life of the ninth century. See Ostrogorsky, History3, pp. 222-232 passim.

74. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 234:15-20,

"Much slander was made against him [Damian] before the emperor. So persuasively was the denunciation crafted that it altered the imperial good will, and by these means employed against Damian, brought about the opposite of good will—with the result that he [the emperor] asked that he be relieved of the dignity of the imperial household."

This passage indicates that Vardas needed some time to achieve his aim.

75. Symeon Magister, Chronicon, 675:4-10, and Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 827:17-19, "Damian the Paroikomenos has disgraced me and you, his emperor, by not rising for me before the Senate." On the Skaramangion, see N. P. Kondakov, Příspevky k dèjinám středovekého umění a kultury = Očerki i Zametki po istorii srednevekovago iskusstva i kul'tury (Prague: Ceská Akademie Vèd a Umění, 1929), pp. 232-238.

76. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 827:19-22.

"The emperor, being angered, immediately commanded Maximian, a certain chamberlain, to seize Damian and take him away to the marketplace of St. Mamas, and there cut off his hair and make him a monk, and he ordered him held under guard."

77. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 235:3-5. "Contrary to all expectations, the emperor, after a short time, advanced Basil to the post of Paroikomenos, also giving him the title of Patrician." This action then was

![]()

112

on the part of Michael III alone, without any suggestion from Vardas.

78. Ibid., p. 235:10-16.

79. Ibid. , p. 234 :21-22, "Driven out, he lived alone after that time, but some high esteem remained his."

80. Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanum, II, 266:11-13. "The monastery of Damian, built by Damian, Paroikomenos and Slav, during the time of Theophilus and Michael."

81. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 379:2-5. "In a like manner Gavrielopoulos and Vasilitzes, from the Slavesian eagerly enriched themselves. ..."

82. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 872:11-12, "... of Slavic race, enriched themselves out of the palace revenues."

83. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 379:5-7, "They say that Vasilitzes, had counseled him [Alexander] many times to make Constantine a eunuch, and have himself elected as co-emperor."

84. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 872:14-16, "... but these counsels were dispersed by those working good for the line of Leo—it being suggested that he was a child or that he was sickly."

85. Ibid., 878:13-18.

86. Arethae, Scripta Minora, I, ed. L. G. Westerink (Leipzig: B. G. Teubner, 1968), 90:10, "Σκλαβηνὸν μειράκιον."

87. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 410:11-411:7.

88. Charanis, The Armenians, pp. 43-44.

89. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 896:9-12.

90. S. Runciman, The Emperor Romanus Lecapenus and His Reign (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1929), pp. 146-150.

91. Georgius Monachus, Chronicon, 896:13-897:2.

92. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 399:12-22.

93. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Thematibus, 90: 41-42.

![]()

113

94. Bury, History of the Eastern Roman Empire, p. 380, n. 2.

95. Zlatarski, Istorija2, I/2, 501-514.

96. Moravcsik, Byzantinoturcica2, I, 356-390.

97. See above, p. 29, n. 103.

98. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Ceremoniis Aulis, II, 666:15-16. Also see above, p. 79, n. 50, for the text and bibliography on the Slavesianon region.

99. See above, p. 65.

100. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 305:18-306:21; and Scylitzes-Cedrinus, Compendium Historiarum, I, 231-232; also J. Gay, L'Italie meridionale et l'Empire byzantin depuis l'avenement de Basil I jusgu'a la prise de Bari par les Normands (867-1071), I (Paris: Bibliothèque des écoles françaises d'Athenes et de Rome, Fase. 90, 1904), 112-114.

101. Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De Ceremoniis, II, 666:15-16.

102. Ibid., 666:13-14.

103. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 305:18-306:21; and Gay, L'Italie meridionale, I, 61-78.

104. Theophanes Continuatus, Chronographia, 130:10-22; and "Skazanija o 42 Amorijskih mučenikov," pp. 61-78.

105. See below.

106. M.P.G., 126, cols. 1194-1240, especially cols. 1217, 1124, and 1228.

107. Leo Grammatici, Chronographia, 224:9-225:3.

108. Michel le Syrien, Chronique, III, 98-99.

109. Skazanija o 42 Amorijskih mučenikov," p. 50:24-27,