VII. THE CZECHS AND THE POLES - ORIENTATION TOWARDS THE WEST

1. The Bohemian State of the Přemyslids — the Heir to the Great Moravian Empire 174

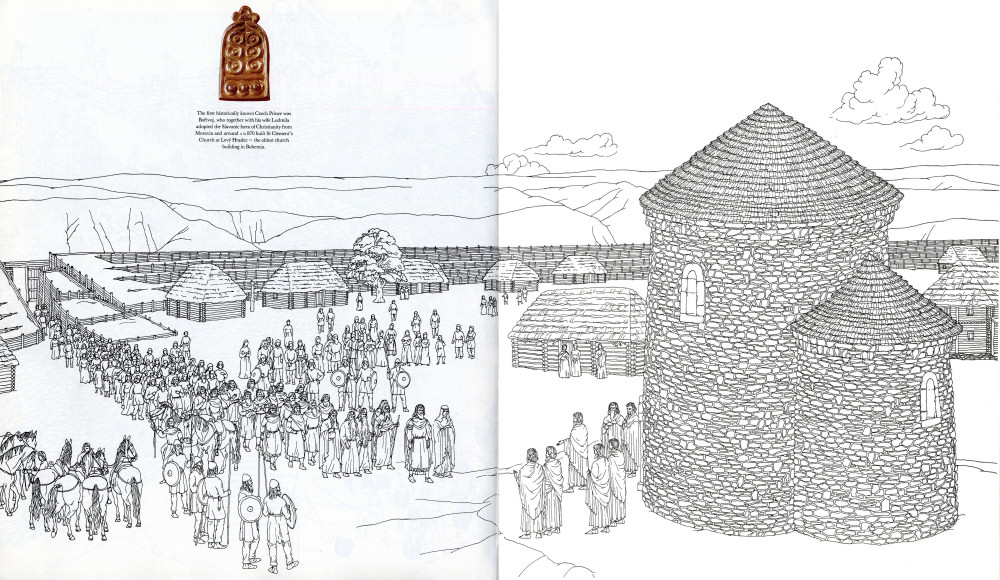

The first historically known Czech Prince was Bořivoj, who together with his wife Ludmila adopted the Slavonic form of Christianity from Moravia and around A.D. 870 built St Clement's Church at Levý Hradec — the oldest church building in Bohemia.

173

![]()

1. THE BOHEMIAN STATE OF THE PŘEMYSLIDS - THE HEIR TO THE GREAT MORAVIAN EMPIRE

Until the ninth century Bohemia lay beyond the mainstream of historical development, hidden behind its veil of border mountains and forests, still sunk deep in the mythical period of its development on which legends cast but a dull light. The territory was divided into natural regions inhabited by groups of tribes. Of greatest importance were the Czechs proper, who ruled in the strategic centre of the land on the lower reaches of the river Vltava and by stages built their main castles there: Budeč, Levý Hradec, Libušin, Tetín and Prague. The first records of the existence of the Czechs are to be found in the Moissac Chronicle, which describes a mighty Frankish expedition to Bohemia in the year 805 and calls the local Slavs "Cichu-Windones". (But there are still doubts as to the correct reading of this largely illegible manuscript from southern France.) Later records do not reveal a great deal more. They report simply the presence of Bohemians and Moravians at the Imperial Council at Frankfurt in the year 822 and the baptism of fourteen Bohemian princes at Regensburg in 845. But the number of the princes shows that the political organization of the Bohemians was still split up into groups. Apart from the Czechs, the only tribes who played an important role were the Lučané from northwestern Bohemia on the river Ohře, the Zličané in the fertile regions of the central Elbe valley, the Western and Eastern Charváti in north-eastern Bohemia (Czech Croats), and the Doudlebi in the south of the country. In addition there were a number of smaller tribes: in the north the Pšované, Litoměřici, Lemuzi, Děčané, and in the western part the Sedličané and the Chbané.

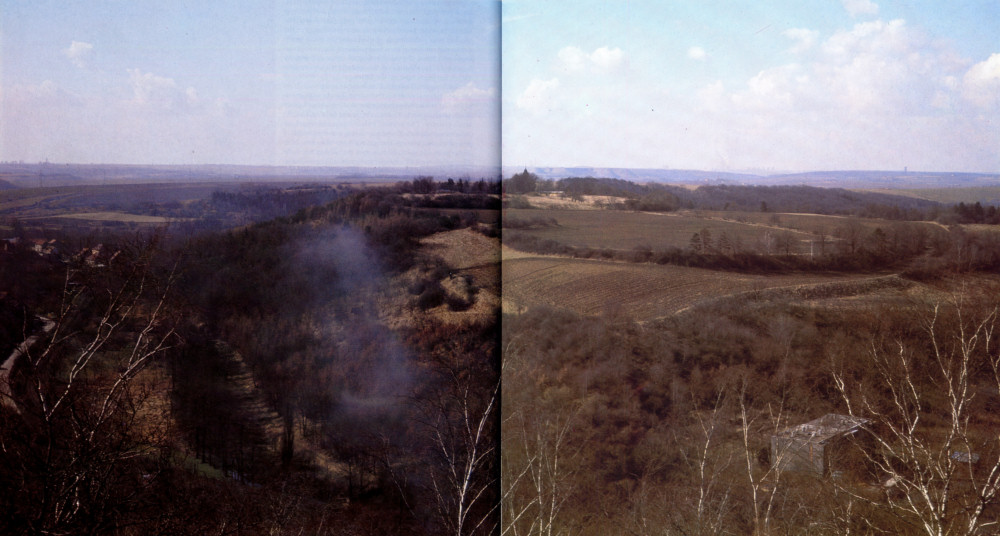

The hill-fort of Libušin was founded, so legend has it, by Libuše, the mother of the Přemyslid dynasty. Excavations have confirmed an old settlement from the sixth to seventh century, but the fortifications did not come into being until the ninth century when Libušin played the role of a border fort on the frontier of two tribal territories.

The legends recorded by chronicler Cosmas in the early twelfth century refer only to the tribe of the Czechs. They relate the story of an ancient ruler, Krok, and his three daughters. The youngest, Libuše, endowed with

175

![]()

the gift of prophecy, assumed the crown after her father's death. But the men were not satisfied with this woman ruler and forced Libuše to marry Přemysl, who thus became the founder of the ruling dynasty. Cosmas lists its members up to the historical period but does not say anything about them except for Neklan, under whom there was a big battle between the Czechs and the Lučané led by the ambitious Prince Vlastislav. This tribal conflict, which must have occurred some time after the middle of the ninth century, imprinted itself upon the memory of the people as an event with a fundamental bearing on the later development of Bohemia. It was one of the main stages in the process of unification. In the year 872 Western sources still speak of five Bohemian princes (Světislav, Vitislav, Heřman, Spytimír and Mojslav, and later Bořivoj was added to these). They were defeated by Archbishop Luitbert during a large expedition against Moravia under Carloman, but at that time the political core was beginning to form in the centre of the country and gradually all the other parts of Bohemia became attached to it.

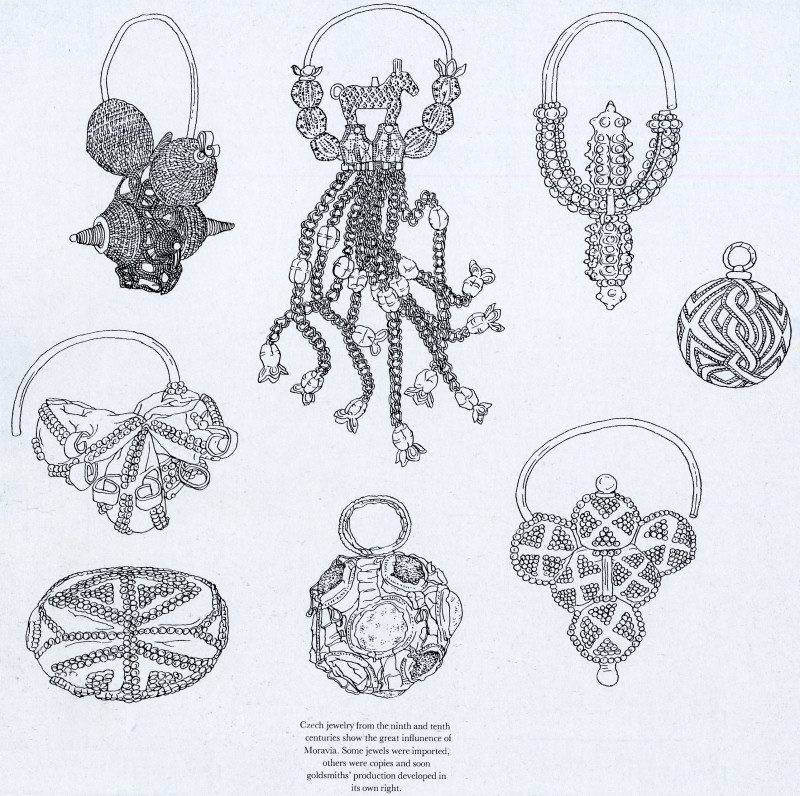

The unknown princess of the Lemuzi tribe, buried at Želénky near Duchařin Bohemia, owned gold and silver jewels of a Great Moravian origin: ear-rings, buttons, an ancient cameo set in a gold case hanging on a gold chain, and a unique silver plaque with a deer and falcon depicted in relief.

The first historical ruler appeared next on the scene. He was Bořivoj, who, so the old Slavonic legends relate, adopted Christianity from Moravia, perhaps from personal contact with Methodius, some time in the years

175

![]()

869 to 870. But not even Bořivoj's rule extended over the whole of the country. He probably commanded only its central and north-western parts. His baptism and that of his wife Ludmila brought about a pagan reaction, the rebellion of Strojmir or Spytimír, in which political aspects — that is, opposition to a certain dependence on Moravia — must have played a part. This gradually increased, especially under Svatopluk, and from 890 on it was acknowledged even by the Frankish Empire. This was, however, merely a short episode, for after the death of Svatopluk in 894 the Bohemian princes came to an agreement with Arnulf at the congress of Regensburg in 895 and renounced all dependence on Moravia. The subsequent political and cultural development of Bohemia assumed a definite orientation towards the West.

Old Kouřim was the residence of the princes of the

Zličané tribe in the ninth and tenth centuries, whose territory lay to the east

of the tribe of the Czechs. The wealth of the princes of Kouřim, rivals of the

Czech Přemyslids, is proved by the magnificence of the jewels found in the local

cemetery, including insignia of the prince's power (the spike of the flag-pole

and a silver-plated stick).

The degree of unification at the end of the ninth century can be judged from the fact that only two princes from Bohemia were present at the ceremony in Regensburg: Spytihněv, Bonvoj's successor, and an otherwise unknown Vitislav, probably the ruler of some tribes in eastern Bohemia who retained a certain degree of independence even in the tenth century, although nominally they acknowledged the sovereignty of the Czech Přemyslids. After the fall of the Great Moravian Empire in the early tenth century, the centre of events shifted to Bohemia, and the power of the Přemyslids reached far to the east into the areas of the vanished Moravian state. The cultural and political prestige of Bohemia grew in the eyes of Christian Europe when the first two Bohemian saints came from that dynasty: St Ludmila, the wife of Bořivoj, murdered at the instigation of her daughter-in-law, and her grandson St Wenceslas, the patron saint of Bohemia, who was assassinated in the year 929 (or 935) by his ambitious younger brother Boleslav. St Wenceslas, a remarkable and, for his time, a highly educated man, was already revered in the tenth century in a number of Old Slavonic and Latin legends, and soon both the West and the East paid homage to him. Furthermore, he became the symbol of Czech statehood. The crown of the Kings of Bohemia is, to this day, called the St Wenceslas Crown.

An important contribution to the development of the state of Bohemia was the foundation of the Prague bishopric in 973, under Boleslav II. Outwardly Bohemia was part of the Holy Roman Empire, but its internal political life was independent. This was underlined by the new ecclesiastical organization whereby its former dependence on Regensburg ceased. The first Bishop of Prague was Thietmar of Saxony, but he was followed by Adalbert (St Vojtěch), who was to become another Bohemian saint and gained merit from his Christianization of the Magyars and Poles.

Early feudal Bohemia rose in importance in the tenth century, but political duality continued until the end of the century since, apart from the ruling Přemyslids, eastern and southern Bohemia came under the sphere of influence of the Slavnik family. One of their descendants was Adalbert. The Slavniks maintained their own political and cultural contacts with, for instance, Saxony

176

![]()

and Poland, and they even minted their own coins. Their power was finally broken by the treacherous assassination of the entire family at their castle at Libice in 995. This bloody act removed the last rivals of the Přemyslids and completed the process of unification. At the turn of the tenth to eleventh century there was a temporary decline during which, for a time, Bohemia was ruled by Prince Bolesław Chrobry (the Brave) of Poland. But under Prince Oldřich (1012-34) and especially under Břetislav I (1034—55) the state of Bohemia, with Moravia now firmly a part of it, reached its basic form, which it kept throughout its further century-long development.

Jewels of that cemetery.

Archeologists have drawn a full picture of the early historical development of Bohemia. They excavated the main centres of the Přemyslids and their tribal rivals as well as localities not mentioned in written records. They have provided valuable facts about periods of which all previous knowledge came from oral tradition.

This includes a hill-fort that the chronicler Cosmas linked in his Legends with Libuše, who gave rise to the Přemyslid dynasty. This hill-fort really exists. It is called Libušin and is located on a spur of land west of a village of the same name. More thorough excavations have been carried out here than anywhere else in Bohemia. True enough, its fortifications were raised only in the historical period, probably in the last third of the ninth century, when Libušin served as a border fort along the tribal borders with the Lučané. But there have been finds of pottery of the Prague type, which shifts the beginning of settlement on the spur back to the sixth or seventh century, the very time to which the legend of Libuše refers. The place must then have served as a cult site. This is suggested both by its location on the top of a hill and the presence of a spring, which played such an important role in the cult of the early Slavs. Among the finds was a clay disc with the symbol of the sun — a cross inscribed in a circle. So it would seem that the legend of Libuše was inspired by some local tradition which survived in the minds of the people into historical times.

A similar case can be cited in regard to the legend of the war between the Czechs and the Lučané, which can also be pinpointed to an archeological site: hill-fort Vlastislav in the Central Bohemian Massif. Cosmas tells us that it was built by Vlastislav, the ruler of the Lučané, and he kept the local allies of the Czechs at bay from there. This strategic position is fully upheld both by the location of the hill-fort as such and the results of excavations, which brought proof of its function as a border fort at the time of tribal conflicts.

The northern neighbours of the Lučané were the Lemuzi. Legend relates that the founder of the Bohemian dynasty, Přemysl, came from their territory in the valley of the little river Bílina below the Ore Mountains. They were naturally allies of the Czechs in their struggle against the Lučané. The tribal centre of the Lemuzi was discovered at a hill-fort between Duchcov and Teplice, called Zabrušany. In the vicinity of this hill-fort — at Zelenky near Duchcov — a burial mound of an unknown

177

![]()

Lemuzi princess was excavated. It contained gold jewels which were worked in a style very similar to that of the Great Moravian Empire. Perhaps the princess who ruled over the Lemuzi and had her seat at the hill-fort of Zabrušany came from Moravia.

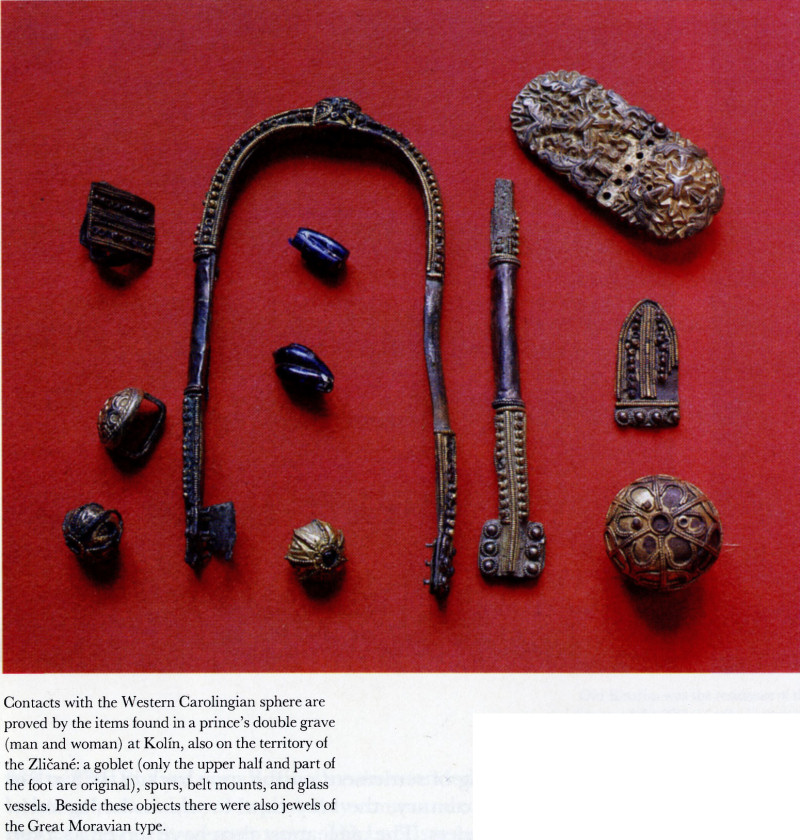

Contacts with the Western Carolingian sphere are proved by the items found in a prince's double grave (man and woman) at Kolín, also on the territory of the Zličané: a goblet (only the upper half and part of the foot are original), spurs, belt mounts, and glass vessels. Beside these objects there were also jewels of the Great Moravian type.

The centre of the second important rivals of the tribe, the Zličané, was the hill-fort at Kouřim. It lies on a spreading hill that forms part of the northern foothills of the Czech-Moravian Uplands. Kouřim is mentioned in the legends about St Wenceslas and St Ludmila, written by a monk named Christian probably at the end of the tenth century, when he talks about St Wenceslas's miraculous victory over the rebellious Prince of Kouřim. Long years of excavations at this hill-fort have brought to light triple fortifications with gates, a shrine with a little lake and a hall 89 metres (200 feet) long, which was the public chamber of the prince's palace. It must have served for assemblies, banquets and other festivities. This unique find in Bohemia has numerous contemporary analogies in Scandinavia and in Russia. Other valuable finds were made when a burial ground was discovered in which members of the prince's family had been interred.

The tomb of a prince was also found not far away, at Kolín, and in it jewels of the Great Moravian type as well as Carolingian imports including a chalice, spurs, stirrup mounts and glass vessels. This shows that the area must have had contacts with the West.

The original tribal centre of the Czechs was probably the hill-fort of Budeč near the village of Zákolany, 25 km (17 miles) north of Prague. It is mentioned in the earliest Czech legends, written in Old Slavonic and in Latin and dating from the tenth century. The second historical prince, Spytihněv, built a St Peter's Rotunda there some time after 895, which is the oldest stone structure still standing in Central Europe that has survived almost in its entirety. His successor Vratislav sent his under-age son Wenceslas there to study Latin under priest Ucenus (or Wenno) so that the first known school on Bohemian soil must have stood there. For a short time Princess Drahomíra lived at Budeč after a disagreement with her son Wenceslas.

178

![]()

Excavations, which have been in progress since 1972, have revealed that the inner part of the hill-fort was fortified some time around the year 800. Later the ramparts were twice enlarged and renewed, for the hill-fort was permanently settled from the ninth to the thirteenth century. The actual palace of the princes was separated from the inhabited area of the hill-fort by a palisade. Inside it stood the rotunda with an eastern and a northern apse — the latter probably serving as a burial chapel. Today a Romanesque tower stands on the foundations of this northern apse. Tombs with jewels of the Great Moravian type prove that burials took place inside and around the rotunda in the first half of the tenth century. The princes' palace has not survived, for its area was disturbed when a modern cemetery was laid out. But the seat of the prince's warden has been discovered. He assumed rule over the hill-fort when the Přemyslids went to settle permanently at Prague Castle. This residence was a complex of wooden and stone buildings surrounded by a palisade and linked by a paved road both to the settlement below and to the Church of Our Lady, which was built towards the end of the tenth century. Its foundations on a rectangular ground plan with an apse were discovered by the archeologists not far from the residence.

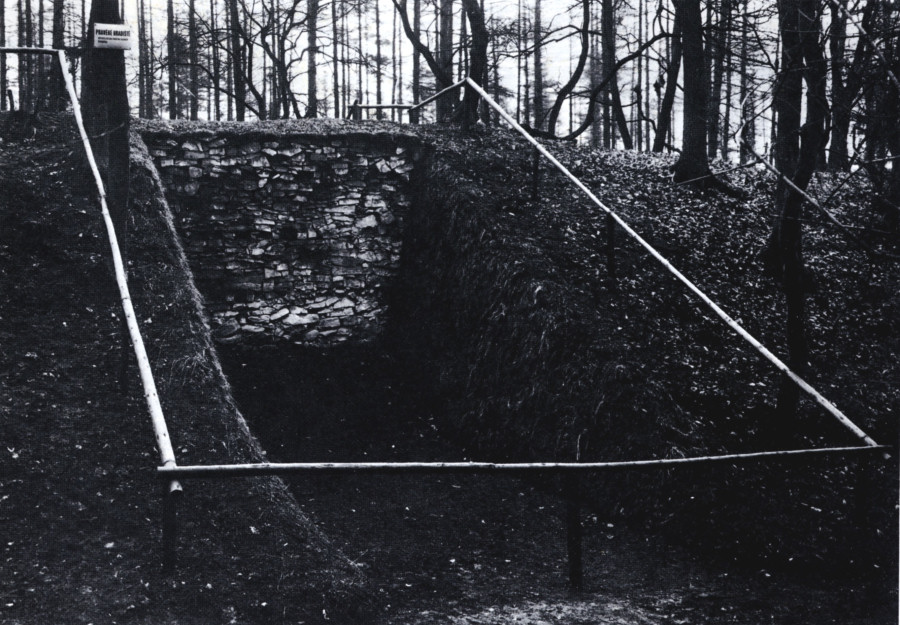

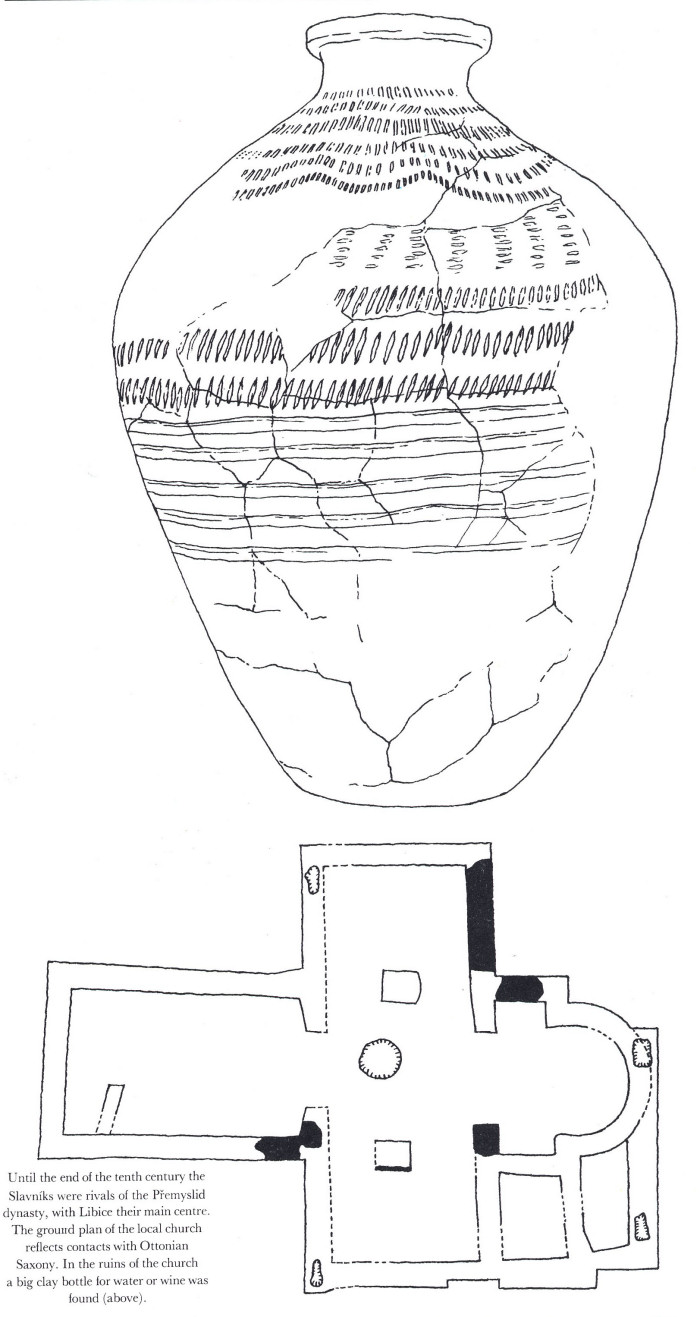

Until the end of the tenth century the Slavniks were rivals of the Přemyslid dynasty, with Libice their main centre. The ground plan of the local church reflects contacts with Ottonian Saxony. In the ruins of the church a big clay bottle for water or wine was found (above).

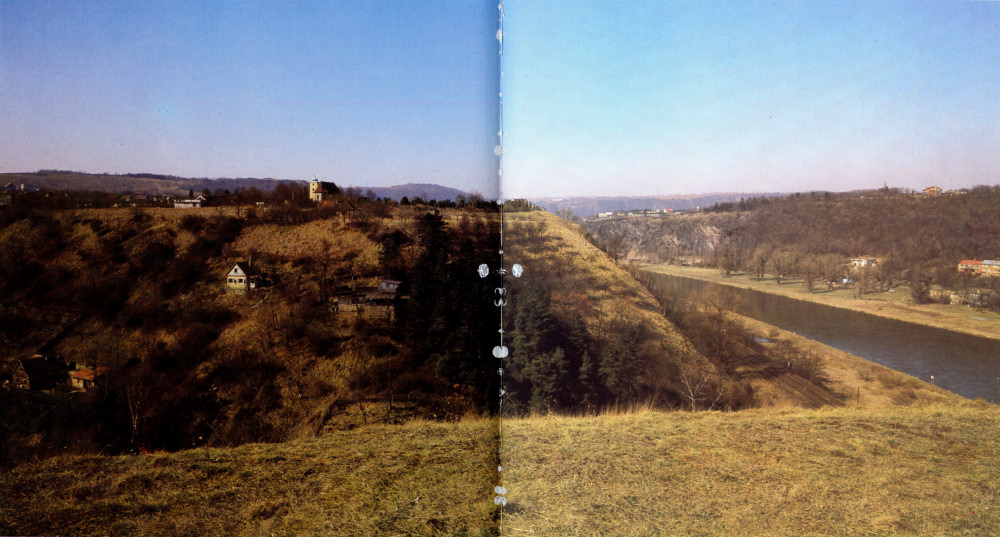

To the east of Budeč on the high left bank of the river Vltava rises another Přemyslid castle, Levý Hradec. Its beginnings likewise go far back into the mythical period, but it was established slightly later than Budeč. After being baptised by Methodius, Bořivoj built the first church in Bohemia there. In the year 982 the second bishop of Prague Adalbert was elected in this church. Excavations in 1947 — 54 have shown that a prince's fortified residence with an outer ward existed there between the early ninth and the first half of the eleventh century. The fortress was abandoned probably during the expedition led by Henry III against Břetislav I. The prince lived inside the hill-fort with his retinue, who had at their disposal log cabins with timber floors, each divided into two rooms with an entrance hall. In the outer bailey, separated from the castle by a ravine, stood simpler dwellings of peasants and craftsmen, built of posts and stakes interwoven with twigs. Only the homestead of a free peasant, which had several chambers and outbuildings, was above average. The prince's palace has not been discovered, but it is quite possible that it stood where traces of a burnt-down building have been found below the foundations of medieval homes. The remains of Bořivoj's Church of St Clement were uncovered inside the present Baroque church with its Gothic presbytery. It was a rotunda with a semicircular apse of the type brought to Bohemia when Christianity was introduced from Moravia. That influence is also suggested by jewelry with which the inhabitants of Levý Hradec were buried at Zalov near the hill-fort.

Originally the Přemyslids had several centres in central Bohemia where they resided in turn and which sustained their power. In the end they recognized the

179

![]()

The original tribal centre of the Czechs was probably the hill-fort of Budec, north of Prague. It still played an important role at the end of the ninth century and in the first third of the tenth, when written records mention it in connection with the first historical princes - Spytihněv, Vratislav, Wenceslas and Princess Drahomira.

180-181

![]()

quite exceptionally suitable position of one of these and made it their permanent residence while the others declined in importance and gradually fell into decay. That centre was Prague Castle. It lay almost exactly in the heart of the country and long-distance routes converged on it from all directions. Here the threads of the country's destiny became interwoven. According to the legends recorded by chronicler Cosmas, Prague was founded by Libuše herself. He adds that the Czech name for Prague, Praha, derives from práh (threshold) which a man was just building in his house on the site of the future castle when Libuše's men found him. It was regarded as symbolic of the fate and historic role of the city, which has always been the entrance gate for cultures from the east, west, north and south of Europe. Philologists, however, are inclined to see in the name of the city a term for a place that was "arid" or "bare" (Czech: vyprahlý). But this is not very certain either.

The most important building at Budeč is St Peter's Rotunda which was built by Prince Spytihněv around the year 900. While only the foundations of the other Czech churches of the ninth to tenth century have survived this building in its original core still stands right up to the vaulting (the tower was added in the twelfth century). Legend relates that St Wenceslas learnt Latin here as a young boy.

Excavations at Budeč led to the discovery of a fortified homestead with the remains of stone and timber buildings and a paved lane — the residence of the warden of the hill-fort who ruled here on behalf of the prince from the end of the tenth to the twelfth century.

The greatest hopes of uncovering the very beginnings of Prague, and in particular of Prague Castle, which is its core, rest with the archeologists. For five decades now they have been searching for traces, wherever this was possible in view of the density of housing construction in the modern city. The narrow, elongated spur above a bend in the river Vltava presented an ideal location for a fortified residence. At one point there rises a knoll

183

![]()

Another important hill-fort in Bohemia in the ninth and tenth centuries was Levý Hradec on the left bank of the river Vltava. It is linked with Prince Bořivoj and the first church building in Bohemia arose here. For that reason the hill-fort is considered a predecessor to Prague.

184-185

![]()

called Žiži, where, to judge by the name, sacrificial fires must have burnt on an ancient cult site. It was there that the ancestors of the Czechs buried their dead long before they adopted Christianity. They raised a barrow on one such grave to cover the bones of a warrior in full outfit. He was interred with his sword, an axe, a knife and a dagger and in addition there was a fire-steel to light a fire and a little wooden water bucket with wrought- iron trimmings. Later, when Prince Bořivoj adopted Christianity from Moravia, he intentionally built the first Prague church, consecrated to the Virgin Mary, on the pagan cult site.

Czech jewelry from the ninth and tenth centuries show the great influence of Moravia. Some jewels were imported, others were copies and soon goldsmiths' production developed in its own right.

We possess no historical records of the time when Prague Castle was founded and can only refer to legends. Excavations suggest that it might have occurred roughly in the last few decades of the ninth century, but it may have happened much earlier. What is sure is that Prague Castle was already standing by the end of the ninth century. It was surrounded by fortifications with a wall of marl in front, supported by earthworks strengthened with wooden grating, which held the entire structure in place. The fortified area was divided into three parts, separated by earthworks with palisades and a moat. The prince's residence stood in the middle one, while the other two parts formed the outer wards.

186

![]()

Prague Castle came to the fore of Czech history only at the end of the 9th century. Around it there grew up one of the oldest and most beautiful cities of Central Europe, upon which centuries of history have left their indelible imprint.

187

![]()

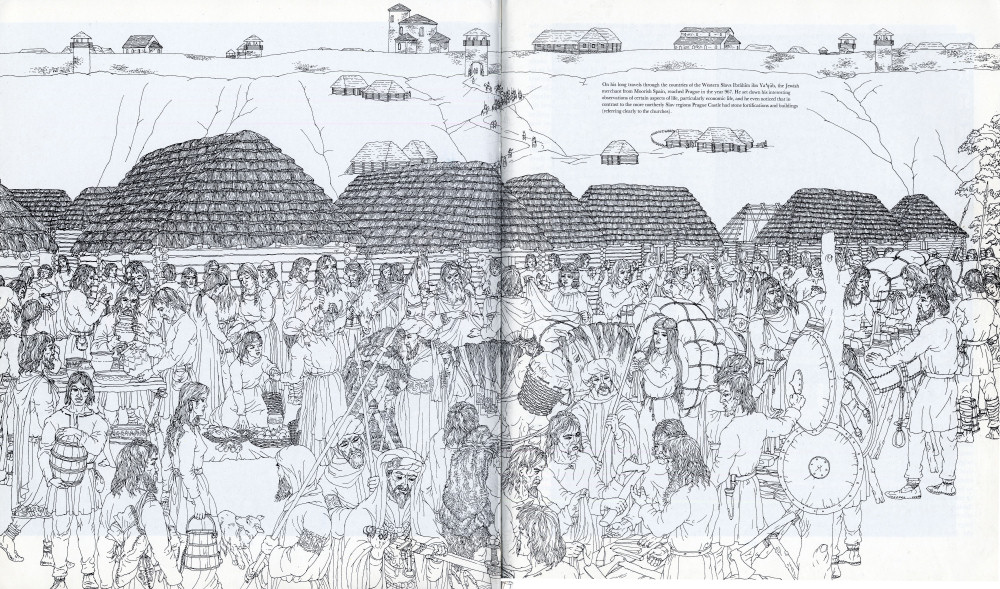

On his long travels through the countries of the Western Slavs Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb, the Jewish merchant from Moorish Spain, reached Prague in the year 967. He set down his interesting observations of certain aspects of life, particularly economic life, and he even noticed that in contrast to the more northerly Slav regions Prague Castle had stone fortifications and buildings (referring clearly to the churches).

188-189

![]()

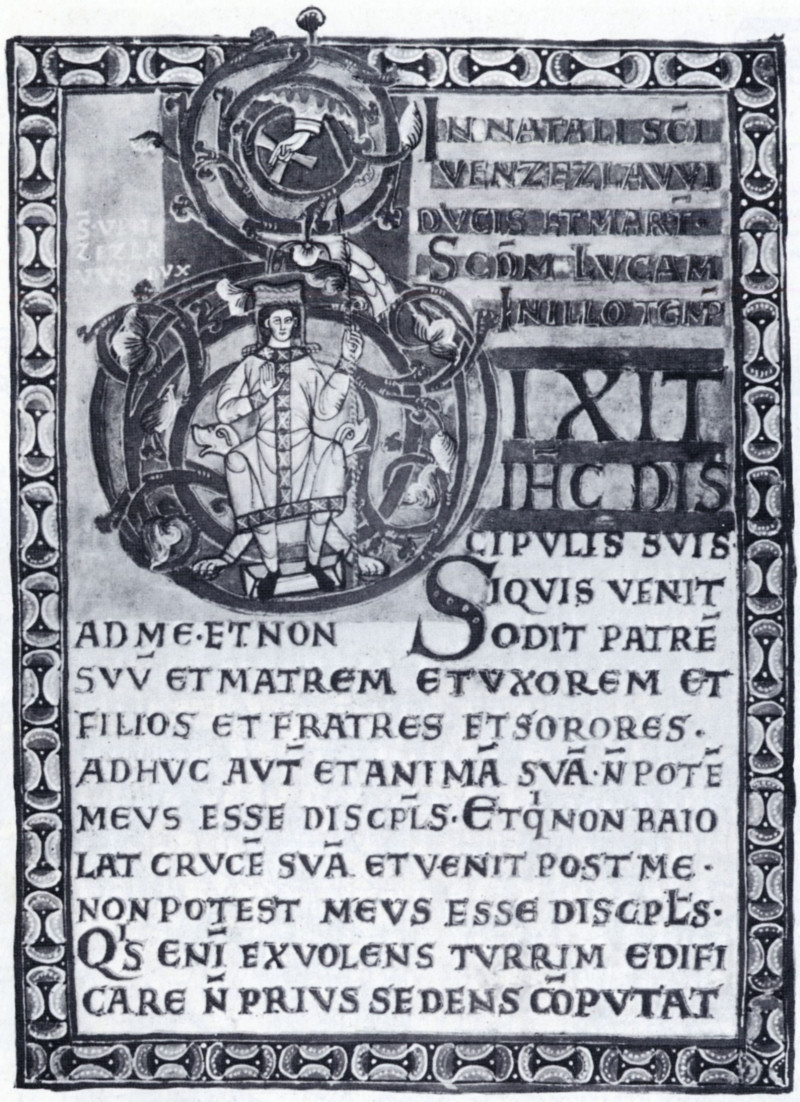

At the end of the eleventh century, during the reign of Vratislav II, the second castle in Prague — Vyšehrad — assumed the role of prince's residence for a short time. The famous Vyšehrad Codex dates from that period, and its illuminations are the work of the first Czech school of painting.

The prince's residence occupied roughly the same place as the royal palace today. In view of numerous reconstructions it has not been possible to discover its original form. We can only judge from the excavations that it must have been a log building on stone foundations, with clay tiles adorning the floors. If we are to believe the tenth-century St Wenceslas legend, it had at least two storeys. The prince himself lived humbly in those earliest times and this was even more true of the other inhabitants of the castle. Their simple log dwellings have been discovered in several places. These were the homes not only of the prince's servants and craftsmen but also of members of his retinue, the defenders of the castle, and of the priests, whose houses were sited in the vicinity of the churches.

Apart from dwelling houses and the necessary outbuildings, there were three churches on the castle premises in the tenth century. None has survived in its original form, and the archeologists have unearthed nothing but the foundations. The oldest was the Church of Our Lady, which, as the legendist Christian relates, was founded by Prince Bořivoj after he suppressed the pagan uprising led by Strojmir. This church was pulled down in the fourteenth century and its location was forgotten. It was not re-discovered until the years 1950—1 during excavations in the western outer bailey. The foundations reveal two building periods: the older church has a rectangular nave and an apse with three curved edges. A large stone tomb inside must have belonged to the founder, but it was empty. After this oldest church had been demolished, the inhabitants built a new and larger one in a different technique and with a fully curved apse. Here a tomb with the skeletons of a man and a woman was found. The man wore a belt of hammered silver plate, the woman had grape-shaped silver earrings and a ring with a loop worn in the hair — jewelry that was in fashion in the first half of the tenth century. There is every reason to suppose that the tomb belonged to Prince Spytihněv and his wife. Spytihněv probably renovated the older building erected by his father, Bořivoj, which had been demolished for unknown reasons. As a result, certain Latin legends speak of Spytihněv, who followed the Latin rites, as the founder of the church, while they say nothing about Bořivoj, who, in fact, adopted the Slavonic form of Christianity.

The second important building in the grounds of Prague Castle was the Church of St George, founded by Prince Vratislav inside the inner fort around the year 920. This church was never completely finished and only slight traces survive. A new church arose when Boleslav II built the first central Bohemian convent of Benedictine nuns for his sister Mlada, who became the first abbess. Boleslav's tomb was discovered in a place of honour in front of the altar. Other members of the prince's family were buried by his side, including his grandfather and predecessor, Prince Vratislav. The convent buildings were altered many times and only parts of the walls date back to the period of Abbess Mlada.

The third and the most important church on Castle Hill was consecrated to St Vitus. It was founded by Prince Wenceslas. It was built north of the palace between Žiži Hill and the stone throne on which, according to an ancient custom, the Bohemian princes were enthroned. The foundations of this church were discovered when the present-day cathedral building was finally completed in 1911. During later excavations it was reconstructed as a rotunda with four apses on the basis of the surviving fragments, even though two of

190

![]()

Only the St Martin's Rotunda at Vyšehrad survives from the period of Vratislav II. The remains of other buildings, the oldest dating from the end of the tenth century, have been uncovered during excavations.

191

![]()

them remain conjecture. When Wenceslas was assassinated by his brother Boleslav and soon came to be regarded as a saint and the patron of Bohemia, his remains were laid to rest here. In the eleventh century it was rebuilt as a Romanesque basilica and in the fourteenth century it was rebuilt again and became a Gothic cathedral, the main sanctuary of the nation. All the kings of Bohemia were crowned in the cathedral and the royal crown is deposited above the tomb of Wenceslas as the main national symbol.

The last survivor of the Eastern orientation of Czech Christianity was the Sázava Monastery, where Slavonic literature still flourished in the eleventh century. The expulsion of the Slavonic monks in 1096 put an end to that tradition and meant a definite leaning towards the Latin rites and the Western cultural orientation of Bohemia. Archeologists discovered the centre of a tetraconchial ground plan on the site of Sázava Monastery, for which the pattern can be found in Byzantine architecture. This helped clarify a unique chapter in the cultural history of Bohemia.

Prague Castle underwent far-reaching changes in the eleventh century thanks to the valiant Břetislav I (1034—55), who built new fortifications in an entirely untraditional manner. These were not the heavy old structures comprising clay-filled wooden galleries and a frontal wall of stone, but had a simple wall of roughly hewn marl held together with mortar. This was a novelty in the Slav region, which was adopted very gradually in other places and did not come into general use until the thirteenth century. Together with the fortifications the prince's palace itself was reconstructed in stone, but little of it remains. In the eleventh century the Bishop of Prague likewise lived in a stone building but only small parts of its foundations have survived. Another important change, in the eleventh century, was the reconstruction of Wenceslas's rotunda of St Vitus into a basilica with nave and aisles, two choirs and three towers. The work was begun by Prince Spytihněv II in 1060 and was finished by his brother and successor, Vratislav II. Excavations revealed its foundations below the cathedral. Its original appearance is given in a drawing in the fourteenth-century Velislav Bible.

During the reign of Vratislav, Prague Castle lost for a time its leading position to Vyšehrad as a result of a conflict between the prince and the bishop. Vyšehrad was the prince's second residence in the territory of Prague. It came into being some time towards the end of the tenth century on a bluff on the right bank of the river Vltava. The original castle of Vyšehrad was destroyed when a fort was built on its site in the seventeenth century. Its short fame is kept alive only by the St Martin's Rotunda, remains of a few buildings that have been excavated, and particularly the famous Vyšehrad Codex, adorned with numerous illustrations, which are the work of the first known Bohemian school of painting.

In the twelfth century the prince's residence was again transferred to Prague Castle where further building alterations were undertaken. Again new fortifications were built and the oldest tower that survives from that period is the Black Tower. The palace was rebuilt in a style derived from the Palatinates on the Rhine. A fire at this time gutted St George's Convent but it was soon rebuilt as was the Bishop's Palace and certain other houses. Every century added new buildings, churches and palaces until the typical panorama of Hradčany Castle came into being, which rises high above Prague as the symbol of the millennium of Czech history.

192

![]()

2. THE PIAST STATE IN POLAND

The beginnings of Polish history are clouded in darkness for one hundred years longer than those of the Czechs and Slovaks. Around 963 Mieszko I appears in the full light of history at the head of a strong state, able to resist even the expansion of the mighty German Empire. What is sure is that a long process of unification must have preceded this, in which the crystalizing core, in the end, was the tribe of the Polanie, who gave their name to the rest of the inhabitants, just as the Czechs did in their area. This development must have already occurred by the ninth century, but we only know tribal names from that time, often distorted beyond comprehension, and legends about the origin of the Piast dynasty, from which Mieszko emerged.

Two important Western Slav states formed in the tenth and eleventh centuries — the Czech with the Přemyslid dynasty and the Polish where the Piasts ruled. Numerous archeological sites have built up a picture of their economic and cultural life.

Slightly more definite reports exist from the ninth century on for the southern part known as Little Poland (Małopolska, or Polonia Minor). In the second half of the ninth century, the time when the Great Moravian

193

![]()

Empire flourished, the Vistulanians (or Wiślanie) established their own state along the upper reaches of the river Vistula. They were known to the Bavarian Geographer, and the Anglo-Saxon King Alfred the Great (871—901) called the country to the east of Moravia "Wisleland". It is mentioned in more detail in the Life of Methodius, a legend from the end of the ninth or early tenth century. Reports point to certain contacts between Moravia and the Vistulanians but largely in the form of conflicts, for the mightier state to the north of the Moravian Gate was a somewhat disagreeable neighbour for the princes of Moravia. The land of the Vistulanians was crossed by trade routes leading from Central and Western Europe to Kievan Russia. This must have been one of the causes of the economic and political development of the Vistulanians.

The history of the Vistulanians was confirmed when archeologists excavated their main centres, which included Stradów, Chodlik and Szczaworyż. But the place of greatest significance was Cracow, which became the main centre of the Vistulanians. It is related that the town was founded by the mythical Krak, who was said to have been interred in an immense burial mound found south of the town. Archeologists, however, clarified the true function of this artificially raised hill 17 metres (56 feet) high. It was only a symbolical tomb or cult centre, which, according to finds made on the site, came into being in the seventh century. The beginnings of the settlement of the Wawel, the hill that dominates the entire surroundings of Cracow, date from that very period. The Vistulanian prince mentioned in the Life of Methodius must have had his residence there and after a battle lost to Svatopluk his estates fell to Moravia. This is confirmed by Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb, who mentions that the Bohemian Prince Boleslav also ruled over Cracow. This, in fact, is the very first mention of Cracow. Clearly Boleslav had inherited the estates from the Great Moravian Empire. By the end of the tenth century Cracow and the entire territory of the Vistulanians formed part of the Polish state. Cracow retained its significance even then. In 1000 it became the seat of a bishop. From the second half of the eleventh century it frequently served as residence of the Polish kings and played a highly important role in the cultural and political history of Poland. Factors contributing to this were its central location in a fertile agricultural area right on the trade route between Kiev and Prague, its proximity to salt mines and its highly developed crafts, particularly metalworking. Post-war excavations have shed light on the history of building in Cracow and the beginnings of stone architecture. At Wawel Castle the archeologists discovered the remain of a church of St Saviour and a rotunda consecrated to the Virgin Mary from the end of the tenth century. The church had a rectangular presbytery while the layout of the rotunda with four apses set in the form of a cross resembled the St Vitus's rotunda at Prague Castle. The remains of a basilica of the Saxon type were found in the western wing of Wawel Castle. It had a nave and side aisles and probably dated from the period of Bolesław the Brave. Apart from church buildings excavations uncovered also the foundations of secular buildings, among them a large hall with twenty-four columns, which must have formed part of the ruler's residence.

The central part of the country, known as Greater Poland (Wielkopolska, or Polonia Maior), proved of decisive importance for the development of the Polish state. This was the land of the Polanie. Their name appears for the first time in the tenth century, prior to that the tribe must have been known by a different name, if we are to believe the facts given by the Bavarian Geographer. For in his work reliable information is

194

![]()

intermingled with reports that are highly questionable. He enumerates the tribes that lived on the territory of Greater Poland, among them the Glopeane and the Lendizi (Lędzianie). The Glopeane were perhaps associated with Lake Goplo in the Kujawy region; this would make them Goplanę. The Lendizi can be linked with Ląd, Lednica island, or with Lake Jelonek near Gniezno, whose northern parts were likewise called Lednica. In every case this refers to the territory of what later became known as Polanie, with whom the Lendizi can be identified. Their centre was Gniezno, while Kruszwica was the main seat of the Gopłane.

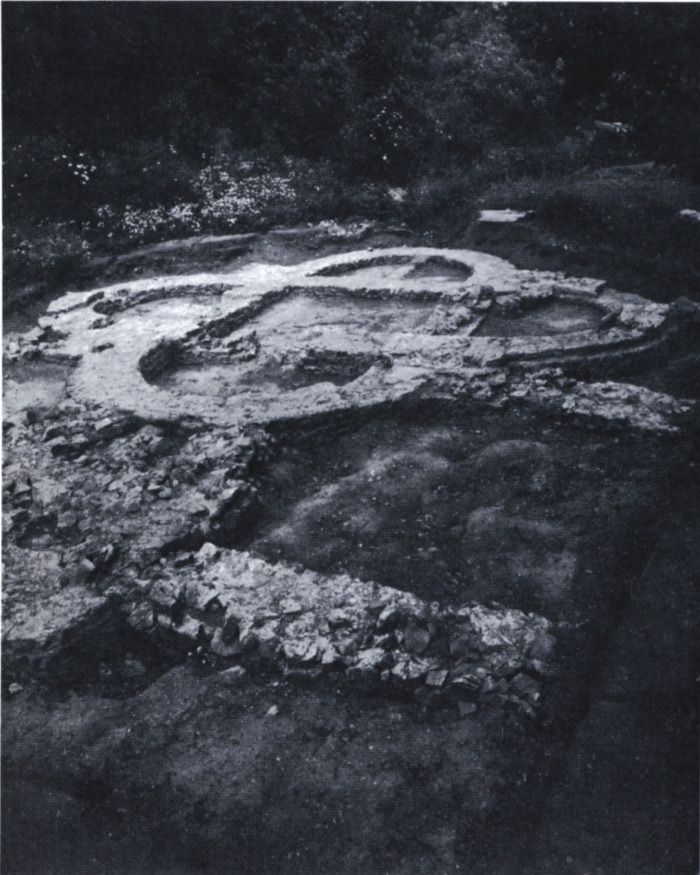

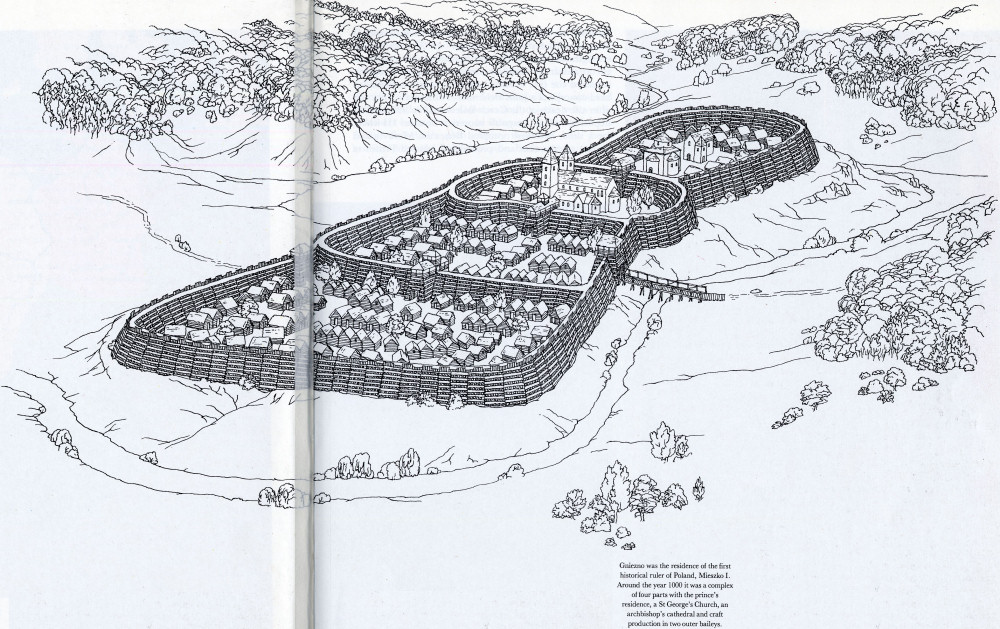

Gniezno was the residence of the first historical ruler of Poland, Mieszko I. Around the year 1000 it was a complex of four parts with the prince's residence, a St George's Church, an archbishop's cathedral and craft production in two outer baileys.

The first historical Polish Prince, Mieszko I, ruled from Gniezno according to reports by Western and Eastern sources (Thietmar of Merseburg, Ibrāhīm ibn Ya'qūb). He was a mighty ruler who commanded a retinue of 3,000 men. His original estates soon spread northwards (taking in western Pomerania with the town of Stettin) and to the south (the land of the Vistulanians, including Cracow and Silesia). Mieszko understood the political significance of Christianization introduced by missionaries from Bohemia, and he managed to have a bishopric established at Poznań in 968, which was directly responsible to Rome. He became the founder of a strong Slav state which played an important role in the history of Central Europe. This made itself known

195

![]()

already during the reign of Mieszko's outstanding successor Bolesław the Brave (992—1025), who strengthened the state by sound political and ecclesiastical organization (Gniezno was raised to archbishopric), assumed the title of King and very nearly realized his bold concept of a joint Bohemian-Polish state: this was after the death of the Czech Boleslav II in 999 and the deposition of his incapable successor Boleslav III when, for a time, Bolesław occupied Bohemia, Moravia and a part of Slovakia and proclaimed himself Prince of

Only remains of later alterations of the archbishop's cathedral at Gniezno, founded by Bolesław Chrobry (the Brave) around 1000, have survived together with a precious bronze door with relief scenes of the life of St Adalbert from the twelfth century.

196

![]()

Bohemia. But this plan was wrecked by the German King Henry II, who took the exiled Přemyslids Jaromír and Oldřich under his protection and helped them regain their princely throne. After the death of the otherwise capable Mieszko II (1025—34) it was, on the contrary, Prince Břetislav I of Bohemia, who attacked Poland, laid waste to Gniezno and took the relics of St Adalbert back with him to Prague. At that point the Polish Boleslaw's plan might, therefore, have been realized from the Bohemian side. But once again King Henry III of Germany blocked the plan as he was afraid of a mighty Slav state as his neighbour and therefore rallied to the support of the exiled Piast Kazimierz (Casimir) I. The two nations — the Bohemian and the Polish — were very close to one another, but thus remained separated, each within its own state.

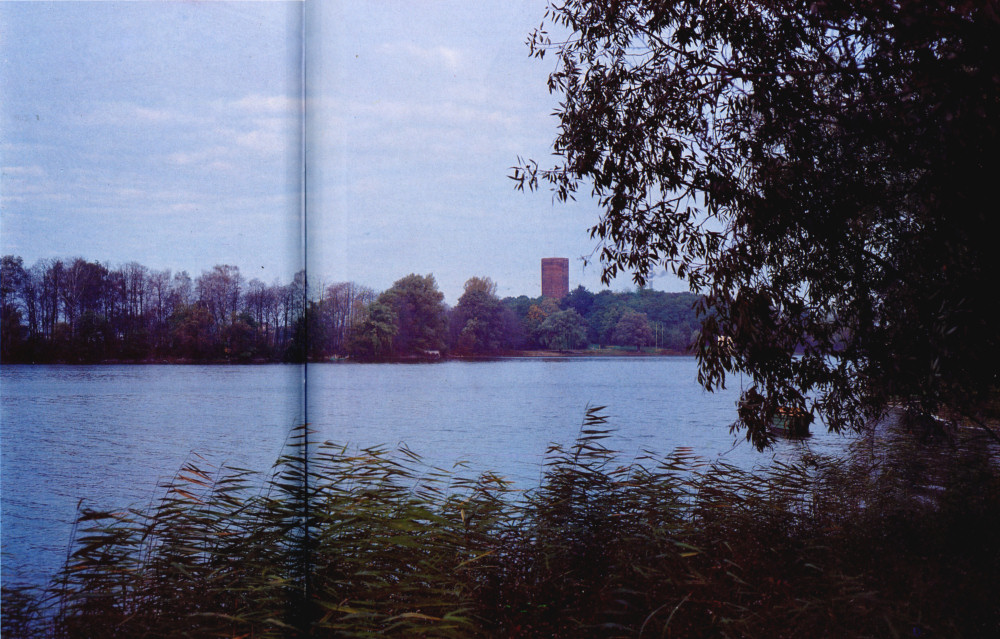

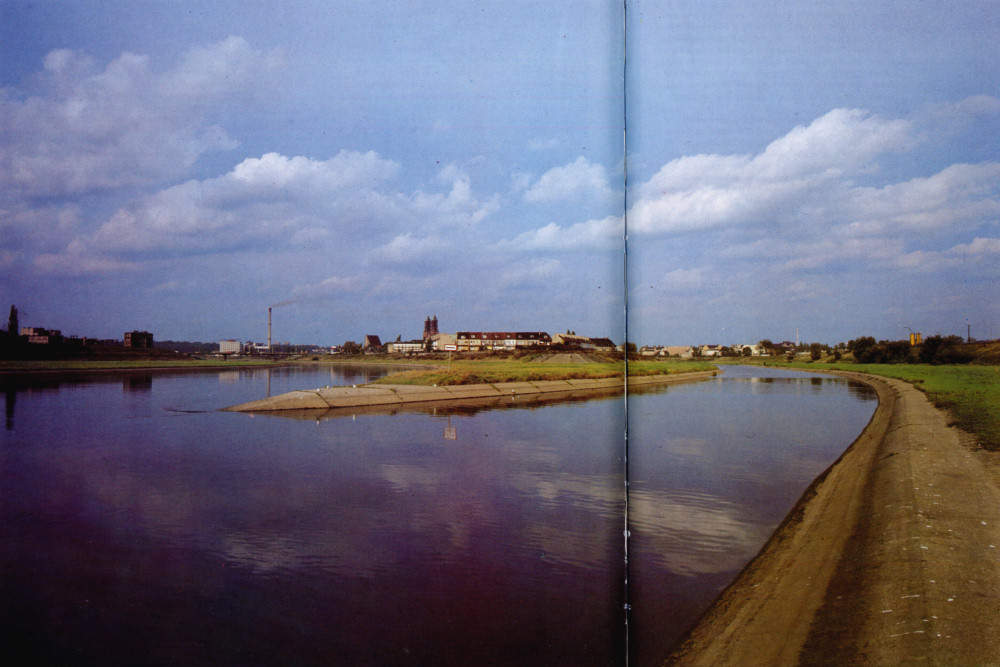

On a peninsula in Lake Goplo in the Kujawy region stood Kruszwica in the tenth and eleventh centuries, one of the centres that upheld the might of the Polish Piast dynasty.

In the tenth century Gniezno became the first capital of the Polish state, but all we know of its beginnings come from legends. The medieval chronicler Gallus Anonymus relates that originally a Prince Popiel lived

197

![]()

The collegiate Church of SS. Peter and Paul has survived of the original architecture of Kruszwica. It has the shape of a Romanesque basilica with nave and aisles and a transept, and a semicircular apse in the presbytery (twelfth century).

198

![]()

here, who was, however, exiled and his place was taken by a poor ploughman named Piast.

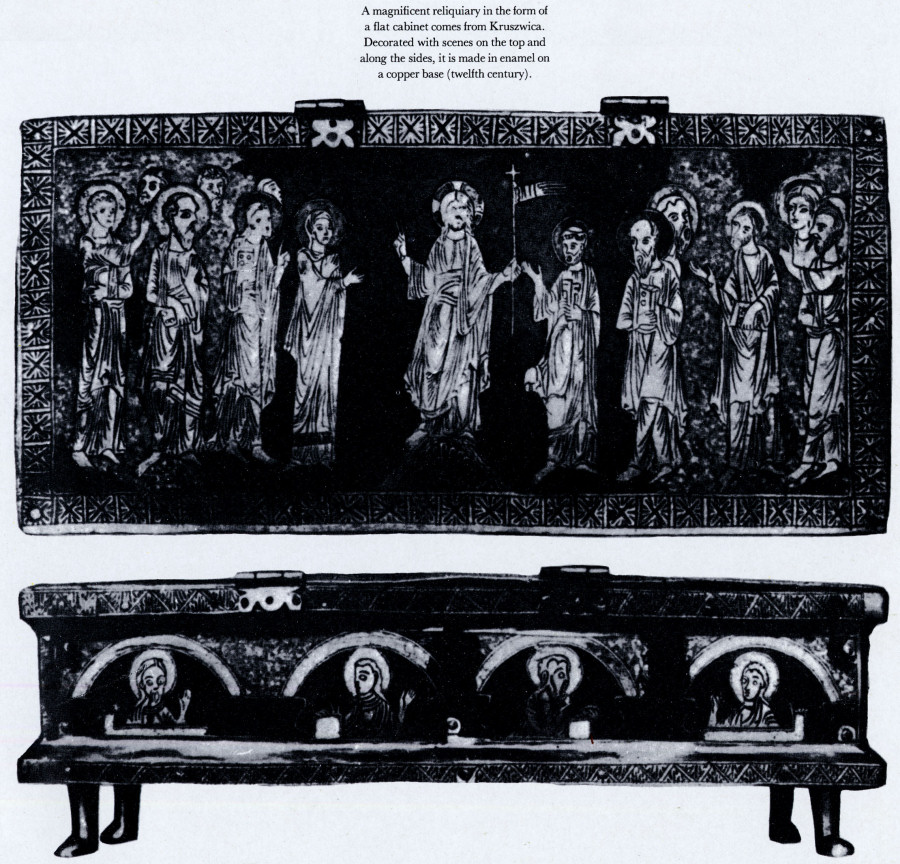

A magnificent reliquiary in the form of a flat cabinet comes from Kruszwica. Decorated with scenes on the top and along the sides, it is made in enamel on a copper base (twelfth century).

This story is highly reminiscent of that of Přemysl of Bohemia, who was likewise a ploughman. Piast became the founder of the Piast dynasty. The legend probably reflects developments on the territory of Poland some time in the second half of the ninth century. This period has been partly brought to light in the course of excavations. On a low hill called Lech Hill surrounded by marshy land between two lakes there stood a castle at the end of the eighth century. It had a fortified outer bailey and in front of this an open village spread along the lake shores. In the middle of the ninth century a change occurred which might possibly be associated with the arrival of the Piast dynasty. Part of the open village was changed into a second outer bailey, and the rest of the settlement was surrounded with a palisade. A whole group of settlements grew up in the vicinity, which served as the economic hinterland of the centre. The part that underwent the most dramatic redevelopment lay to the east of the castle, where several routes crossed. First there would have been a market centre here, and later a medieval town grew up on this site. The entry of Poland into history, in the second half of the tenth century, is also revealed in finds resulting from excavations. The old fortifications were renovated and the palisade of the settlement below the castle was replaced by regular fortifications so that a whole complex of four parts came into being. Its core was the residence of the prince with the first Christian church of St George. In the first ward Bolesław the Brave built a cathedral to commemorate the establishment of the Gniezno archbishopric in 1000. Craftsmen inhabited the remaining outer wards. The high level of their work is proved by numerous finds, among them articles of wood, leather and bark, which have survived thanks to

199

![]()

Poznań on Dome Island in the river Warta held an outstanding position in political and cultural life in early Polish history. It became the seat of a missionary bishopric in 968 with a St Peter's Church, remains of which survive beneath the present cathedral.

the favourable soil conditions. There exists a report by the Prague chronicler Cosmas on the rich loot that the Bohemian Prince Břetislav found at Gniezno during his invasion of Poland in 1039.

Not all contacts with Bohemia took the form of conflicts. Christianity spread to Poland through the mediation of Bohemia, chiefly thanks to Dobrava (Doubravka), the sister of Boleslav II and wife of Mieszko I, and St Adalbert, the Bishop of Prague. He was originally buried in Gniezno after suffering a martyr's death in Prussia. His step-brother Radim (Gaudentius) became the first archbishop of the town. It is, therefore, not surprising that the first churches in that Polish centre were consecrated in the same manner as the oldest churches at Prague Castle, St George's and the Church of Our Lady. But nothing has so far been found of the original foundations of these buildings nor of the archbishop's cathedral. Only remains of later reconstruction were uncovered, including a coloured mosaic floor from the eleventh century and valuable twelfth-century bronze doors with relief scenes depicting the life of St Adalbert. Gniezno retained its important status into the thirteenth century when it became a typical medieval town.

Another pillar of Piast power in the early Middle Ages was Kruszwica, the centre of the Kujawy region. It stood on a narrow peninsula in Lake Goplo. In medieval legends it is linked with Popiel, who after being exiled from Gniezno died a miserable death here. Excavations begun in 1948 provide an idea of the development stretching back to the time before the Polish state came into being. Traces of life on the peninsula date back to the ninth century and the picture becomes clearer in the second half of the tenth century, when a castle with a fortified outer ward stood here and metalwork flourished. The wards were enlarged in the early eleventh century: a smaller outer ward by the castle with a church and a larger outer bailey with wooden dwellings of craftsmen. At the same time a group of settlements grew up on both shores of the lake. This underlines the growing importance of Kruszwica, which became the residence of a prince and under Mieszko II the seat of a bishop. The struggle between Władysław I Herman and his son Zbygniew in 1096 caused Kruszwica to lose its political significance. It retained only its economic importance, producing glass and clay articles with coloured glazes.

The third most important town in early Polish history was Poznań on Dome Island in the river Warta. In the north-western parts of the island a small castle alreadY existed in the ninth century, and an open settlement is recorded at the end of that century. But Poznań did not become a mighty fortified centre until the time of the Piast dynasty. Soon after the adoption of Christianity in 968, it became the seat of a missionary bishop and, for a certain time, it probably served as the residence of Mieszko. Tradition has it that Mieszko's Czech wife Dobrava had the Church of Our Lady built

200-201

![]()

there. In view of the densely built-up areas of the modern town it has not been possible to carry out full excavations in order to explain the topography in greater detail. But it is certain that a fortified outer bailey lay close to the castle on its eastern side. During the second half of the tenth century a bishop's Church of St Peter was erected here, of which the remains have survived below the present cathedral. Around it, as in the surrounding villages, stood the wooden houses of the craftsmen. The capital city of the Polish state was Gniezno, but Poznań held a leading political and cultural position far into the Middle Ages.

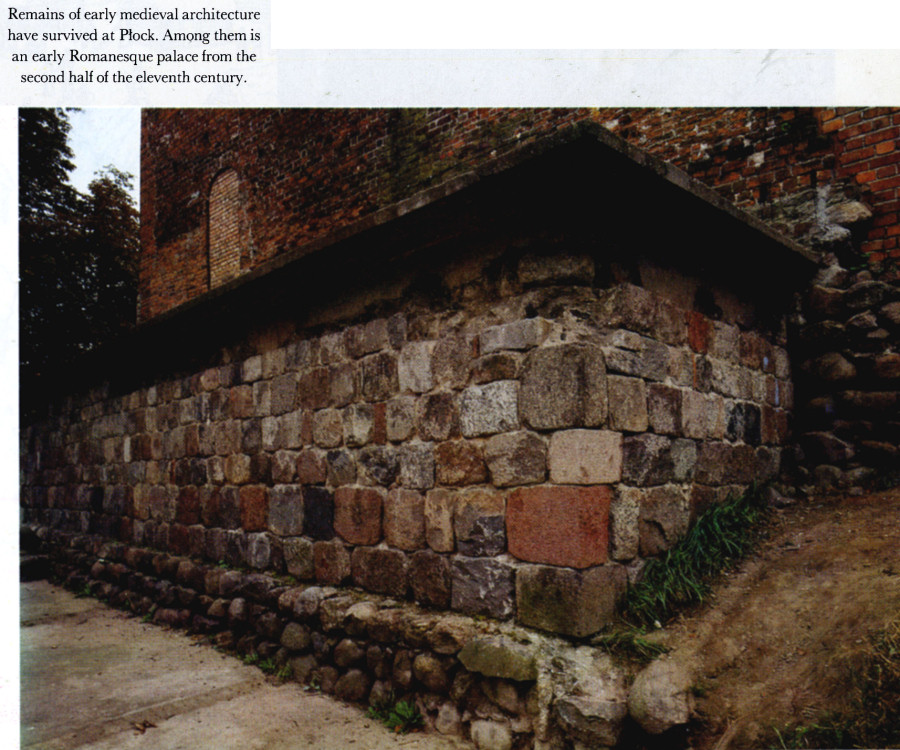

Apart from these main centres the power of the Piasts was based on a network of castles, whose significance was revealed only by excavations. Remains of stone architecture, both palaces and churches, survive in many of them. One example is at Płock in Mazovia where in the eleventh century the prince owned a palace built of stone. There were two rotundas there, to which a bishop's basilica with nave and aisle was added in the twelfth century.

In the very centre of Piast Poland there was another important locality — Łęczyca. It grew up on the site of an old palisaded and fortified settlement in the eighth century. Investigations point to an ancient tribal centre which was strongly fortified in the early twelfth century under Bolesław III Krzywousty (Wry-Mouth). The foundations of an eleventh-century monastery have been found close to the castle, on the right bank of the river Bzura.

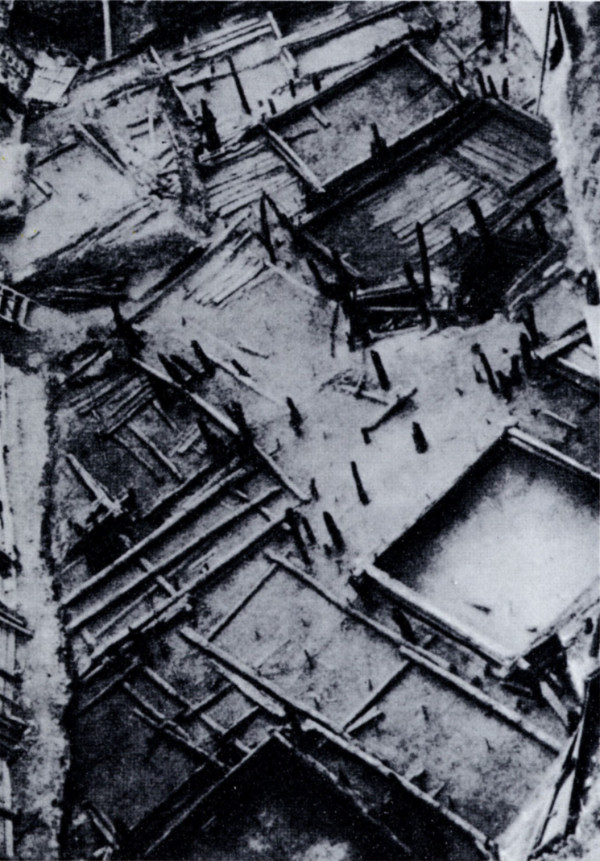

The intricate construction of the tenth-century fortifications at Poznań comprised a timber framework with chambers filled with stones. The framework was secured at this base by posts made from inverted sections of the trunks with the stumps of branches acting as hooks.

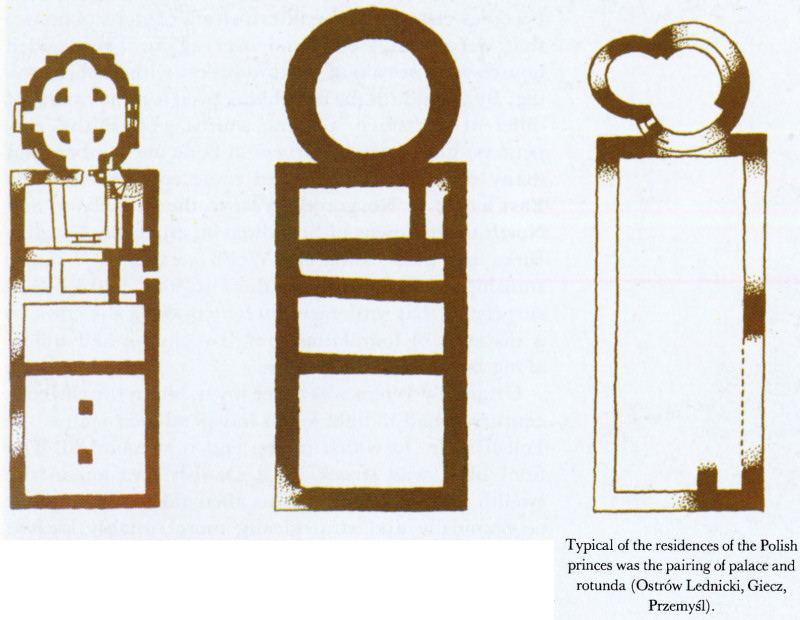

Some Polish castles can pride themselves even on bridge constructions, as German archeologists discovered in the Slav castle of Mecklenburg. The castle was built in the early tenth century on an island in Lednica Lake (Ostrów Lednicki) near Gniezno and was linked with the fortifications by a 600 metre (656 yard) long bridge. Apart from semi-subterranean dwellings excavations have brought to light the foundations of two interesting stone buildings: a church with a square nave, rectangular apse and attached dwelling places and a palace with a chapel with a central, cross-shaped ground plan and a cupola supported by four pillars.

This pairing palace and rotunda appeared on several other sites in Poland. One was discovered at Giecz, a hill-fort on the left bank of the river Moskawa, which protected the southern approaches to Gniezno. Excavations have shown that the buildings remained unfinished, probably as a result of the invasion by Břetislav I in 1039, during which part of the population was forced to move tó Bohemia, where they founded the village of Hedčany. Another palace with a rotunda, also from the eleventh century, stood in the hill-fort of Przemyśl in south-eastern Poland. Here a building of an entirely different type was found, a church with a cupola on the Russian-Byzantine ground plan of a cross inscribed in a square. Remains survive below the castle. The hill-fort protected an important route to Kiev on the Russian-Polish border and therefore often changed hands.

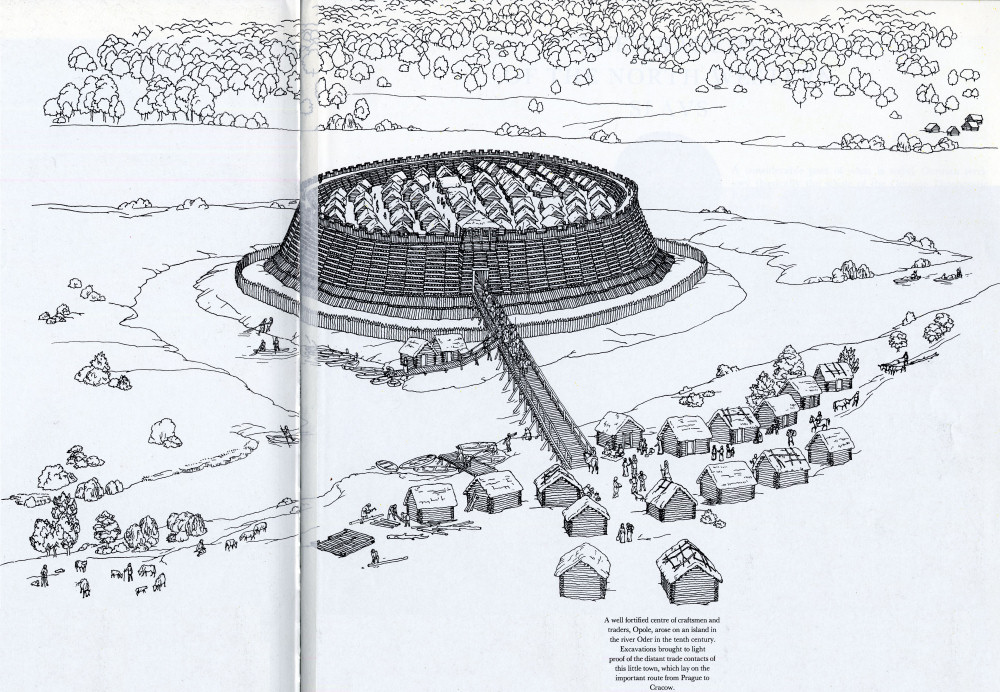

Along the same route from Prague to Cracow and Russia lay the important crafts and trade centre of south-west Poland, Opole. The little fortified town on an island in the river Oder may originally have been the centre of the Opolanie tribe. In the tenth century a settlement with timber-reinforced earthworks arose here. It had three gates and wooden houses laid out along regular timber-paved streets. The trade contacts of this settlement are shown in finds of Byzantine silk, pearls from the Persian Gulf, fragments of broken Arabian dishes, Scandinavian fibulae, Russian Easter eggs, whorls and little bells, Rhineland bronze dishes and Moravian graphite vessels.

The ports on the coast of the Baltic Sea lived a busy life. The Slav tribes which settled the south coast of the Baltic established a number of ports: Starigrad (later Oldenburg) and Lübeck in the west to Gdańsk in the east, but none outdid the fame of Wolin, the famous Vineta or Jomsburg of the Western chroniclers and Northern sagas. Chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote that this harbour town, which flourished in the ninth to eleventh centuries, was the greatest European town inhabited by Slavs. It stood on an island of the same name at the mouth of the river Oder. Long years of excavations by German and, after the Second World War, Polish archeologists have filled in considerable detail to support Adam's enthusiastic description. It was shown that the town once had mighty fortifications.

Remains of its harbour were found by underwater archeologists. According to written reports there was even a lighthouse.

202

![]()

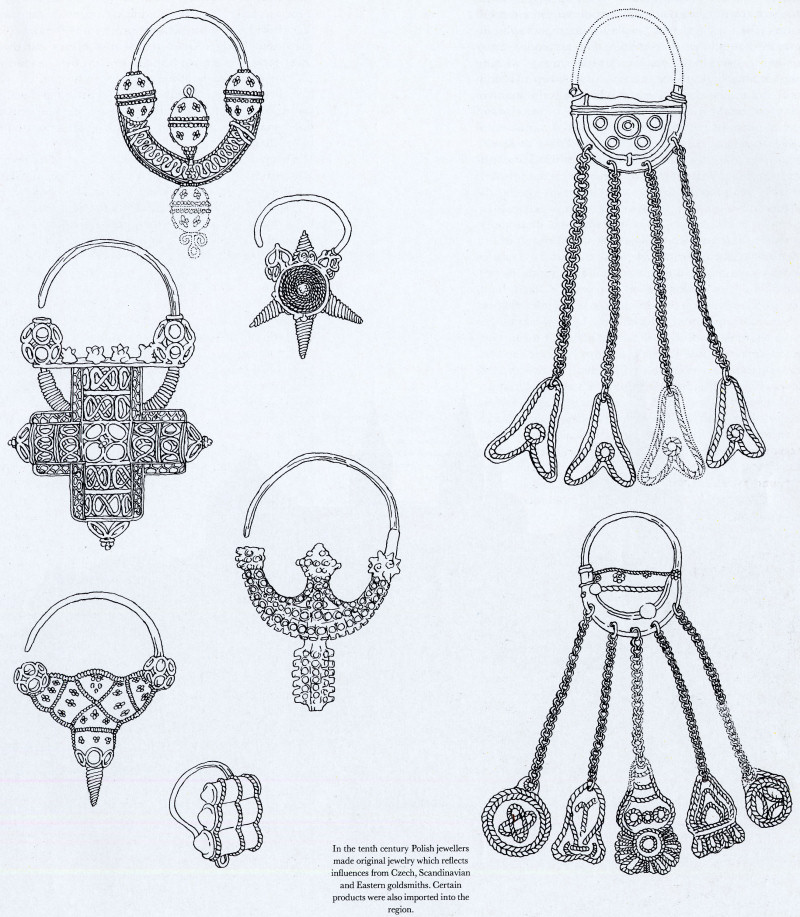

In the tenth century Polish jewellers made original jewelry which reflects influences from Czech, Scandinavian and Eastern goldsmiths. Certain products were also imported into the region.

203

![]()

Płock was the centre of Mazovia. It lay on a steep spur above the Vistula and was one of the many castles upon which the might of the Piast dynasty was based.

How intensive the settlement was becomes clear from the fifteen strata of ruins of houses that were rebuilt over and over again. The wooden houses were set along narrow streets with timber paving. By the side of the merchants lived a great variety of different craftsmen: potters, smiths, goldsmiths, carpenters, glassmakers, carvers in bone and amber, and many others. Finds revealed trade contacts with the East as far as Novgorod, West to the Rhineland, and North to the towns of Scandinavia, especially Swedish Birka on Lake Málaren. Wolin served as a major transhipment centre for all these regions, and it is not surprising that settlement stretched along the coast to a distance of four kilometres (two and-a-half miles) along both sides of the town.

Remains of early medieval architecture have survived at Płock. Among them is an early Romanesque palace from the second half of the eleventh century.

Originally Wolin was a free town, but in the eleventh century it had to fight for its independence against the Polish state, to which in the end it succumbed. The final blow was struck by a Danish invasion in the twelfth century. Its role was then taken over by the economically and strategically more suitably located Stettin (or Szczecin). This town dates back to the ninth century and its history is a record of its changing roles. Stettin was at times independent, at others dependent on the Polish or the Pomeranian state. Later it became one of the most important harbours in Poland. The fortified town spread over three hills; the highest, where later a medieval castle was built, had once been a shrine to Triglav, and subsequently a prince's residence stood upon it. Stettin flourished in the twelfth century and, to judge by the built-up area, it must have had a population of roughly 5,000, which was large for that time.

205

![]()

Typical of the residences of the Polish princes was the pairing of palace and rotunda (Ostrów Lednicki, Giecz, Przemyśl).

The log cabins in the little trading centre of Opole in Silesia were set out along streets with wooden pavements in the tenth to eleventh century.

The harbours along the coast of eastern Pomerania include Kamień, Kołobrzeg and Gdańsk. The oldest written mention of Gdańsk is to be found in the Life of St Adalbert of the year 997. The Bishop of Prague set off on his mission to the pagan Prussians from this town, only to meet his death as a martyr there. As long years of excavations have shown, the fortified town with a feudal residence lay originally on an island at the confluence of the Motława and the Vistula. The harbour was situated on the inner, western shore of the island facing the mainland, to which it was linked by a bridge. In the twelfth century a settlement grew up below the castle on the mainland shore, where the inhabitants built a harbour for trade and fishing. Excavations have revealed remains of its wooden piers. In the tenth and eleventh centuries Gdańsk with its timbered earthworks had about one thousand inhabitants living in wooden houses set along narrow streets. After a fire at the end of the eleventh century the whole town was rebuilt. In the twelfth century, when it was part of

206

![]()

the independent Pomeranian princedom, it grew considerably and became an important centre of craft production and international trade. Gdaňsk is one of the few ancient ports on the Baltic Sea that have retained their importance to the present day.

A well fortified centre of craftsmen and traders, Opole, arose on an island in the river Oder in the tenth century. Excavations brought to light proof of the distant trade contacts of this little town, which lay on the important route from Prague to Cracow.

The most recent Polish excavations have provided an idea of what the ships of the early medieval Slav seafarers on the Baltic looked like. They resembled Viking ships and even matched them in technical achievement. They were not as quick to manoeuvre as the Viking ships, from which their construction differed by having a flatter bottom. In this they resembled Friesian ships. The Slav ships had a smaller draught and the weight of the sails was shifted forward, which made them more stable so that they could stand up even to heavy seas. This picture was gained from wrecked ships, parts of ships and various tools that have been recovered, as well as by finds of models and even toy ships.

Seafaring, shipbuilding and the construction of harbours occupied all the Slav inhabitants of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. This applies to the Polish and Pomeranian areas, which are nowadays on Polish territory, and the western, now German parts, which were once inhabited by Slav tribes that have long since vanished.