V. A MAJOR MILESTONE IN DEVELOPMENT

1. The Great Moravian Empire and its Centres 105

2. Pribina's Principality at Nitra and Mosapurc 119

3. The Croats and Serbs, their Political and Cultural Emergence 125

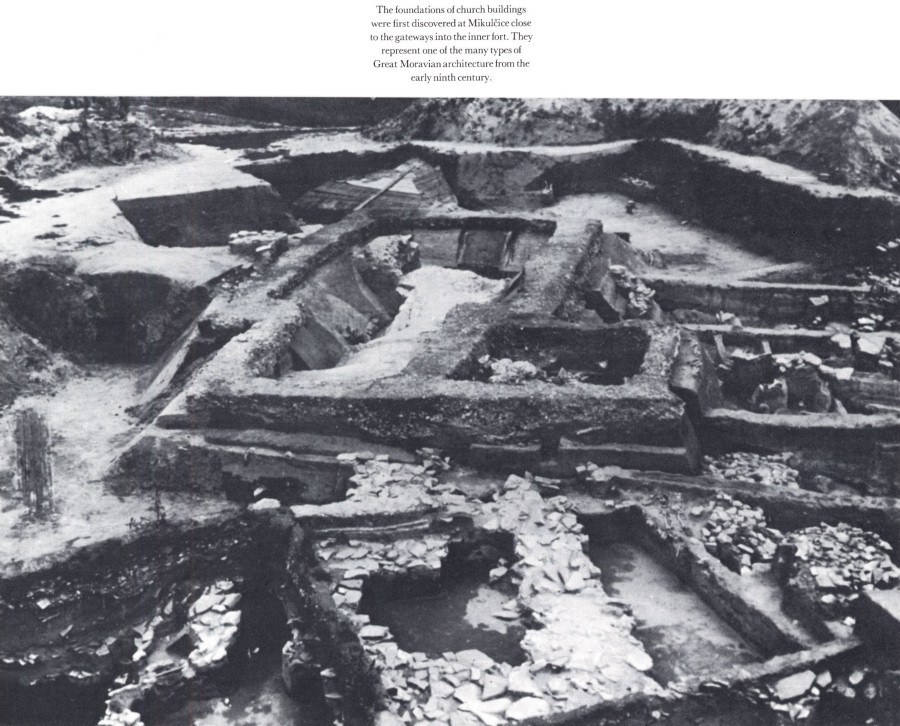

"Rastislav's ineffable fort", mentioned in the Fulda Annals for the year 869, has been excavated for several decades at hill-fort Valy near Mikulčice in southern Moravia. This complex settlement covering 200 hectares (about 80 acres) lay on an island formed by the river Morava.

The masses of Slav people who flooded a large part of Europe in the sixth to eighth centuries represented a mighty and ethnically almost unified group, but politically they were split up and therefore could hardly resist the militarily well organized nomads or the ambitious great powers such as the Franks in the West and Byzantium — the remains of the Roman Empire — in the East. Samo's Empire was only a temporary phenomenon, which came into being during the resistance to Avar oppression and disintegrated soon after the death of the man who had brought it into existence. It would seem that in the first few centuries of their history when the process of settlement was in progress, the Slavs did not have the conditions or the need for a permanent state organization. At most they established unions of tribes according to the local situation, which broke up naturally when those particular conditions no longer existed. Not until the ninth century did the time become ripe for basic changes in this respect — clearly since the colonization of the new territory had been basically finished by then, economic life was entering a new phase, and the settled area needed to be effectively defended against pressure from outside. For that reason the first Slavonic states emerged at that time in quick succession in Central, South-Eastern and Eastern Europe, and they showed themselves capable of more permanent existence.

1. THE GREAT MORAVIAN EMPIRE AND ITS CENTRES

In Central Europe there was a state whose core lay in present-day Moravia, but its sphere of influence went far beyond that territory, from which it derives its name — the Great Moravian Empire. It developed in the first half of the ninth century, soon after the Avars had been routed by Charlemagne, and it put up a barrier to Frankish expansion, which aimed at the lands beyond the Danube in the direction of the Carpathians. It soon became the centre of attention of Western chroniclers, such as the authors of the Annates Regni Francorum, Annales Fuldenses, and others, the writers of Church records, e.g. papal epistles or the manuscript on the conversion of the Bavarians and Carinthians, De conversione Bagoariorum et Carantanorum. The interest of Byzantine

105

![]()

When the process of colonization of new territories was basically finished the first Slav states appeared in the pages of history in the ninth century. The greatest of these were the Great Moravian Empire in Central Europe, the Bulgarian Empire in the Balkans, and Kievan Russia in Eastern Europe.

106

![]()

historians was no less great. The very term Great Moravia was invented by the Emperor and author Constantine Porphyrogenitus. Until not long ago these works were the only sources of information about the state that achieved such great political significance in the ninth century and became a centre of culture with an influence that spread over a large area to the other Slavs. In the last few decades, thanks to intensive excavations, another important source has been added, which not only complemented existing historical knowledge but considerably revised it in many respects.

The first figure to rise out of the darkness of history was Mojmír, the true founder of the Moravian state, who in the years 830—833 added the princedom of Nitra (today's south-western Slovakia) to his estate in Moravia; he expelled its ruler Pribina, an ally of the Franks, from there. By that time Christianity had come to Moravia through the Frankish missionaries, whose centre must have been the bishopric of Passau. The Moravian rulers soon realized the political danger of Christian conversion from that side, accompanied by the threat of loss of independence. For that reason Mojmir's successor, Rastislav (846—869), expelled the Frankish missionaries from his country and aimed at setting up an independent Moravian diocese. Since Pope Nicholas I did not approve his petition, he appealed to the Byzantine Emperor Michael III with the same supplication in 862. He was seeking support against both the Franks and the expanding Bulgarian Empire, whose frontiers ran alongside his own on the river Tisza. This was a brilliant diplomatic move, which was to have far-reaching cultural effects, for Rastislav requested that missionaries be sent who would be able to proclaim Christianity in the Slavonic tongue.

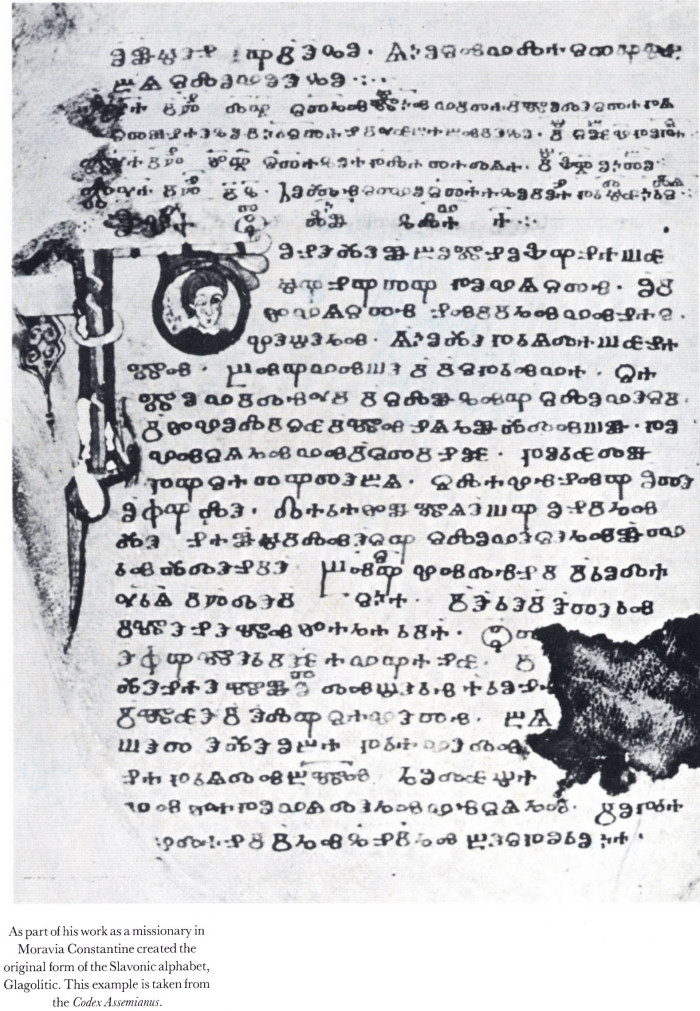

As part of his work as a missionary in Moravia Constantine created the original form of the Slavonic alphabet, Glagolitic. This example is taken from the Codex Assemiamis.

Emperor Michael and Patriarch Photius sent him the brothers Constantine and Methodius, sons of a high officer in Thessalonica. Both possessed a good command of the Slavonic tongue, for the population around Greek Thessalonica was predominantly Slav. The older, Methodius, entered a monastery after working as a clerk and became abbot at Polychronos. The younger, Constantine (later known by his monastic name of Cyril), was Photius's favourite disciple, and worked as teacher of philosophy at the patriarchal school attached to the Cathedral of the Holy Apostles. Both had experiences in diplomacy: Constantine had once accompanied Photius as ambassador to Caliph Mutawakkil. In 860 both brothers travelled with an important political and religious mission to the Khazars on the Crimea, where they gained respect, among others, by finding the relics of Pope St Clement. They made thorough preparation for their mission to Moravia. Constantine invented Glagolitic, a special Slavonic script, able to express the phonetic sounds of the Slavonic language, which considerably differed from the Greek. (Cyrillic, which to this day is used by the Serbs, Bulgarians and Russians, came into existence slightly later in the circle of Methodius's disciples in Bulgaria.) Liturgical books were translated into Slavonic, and divine service was held in the Slavonic tongue. At the time that was a dramatic innovation, since throughout Europe only the Latin or the Greek rites and texts were used — with the exception of England under Alfred the Great and Moravia under Rastislav and Svatopluk. This development, which was later approved even by the Pope, met with great success among the Slav population and soon drove the efforts of Frankish missionaries into the background. This naturally caused concern among the Frankish bishops, who after the death of Constantine in Rome (869) for a time abducted Methodius and unlawfully imprisoned him. Their action fits into the political context which was marked by constant Moravian- Frankish conflicts, with varying success on both sides.

107

![]()

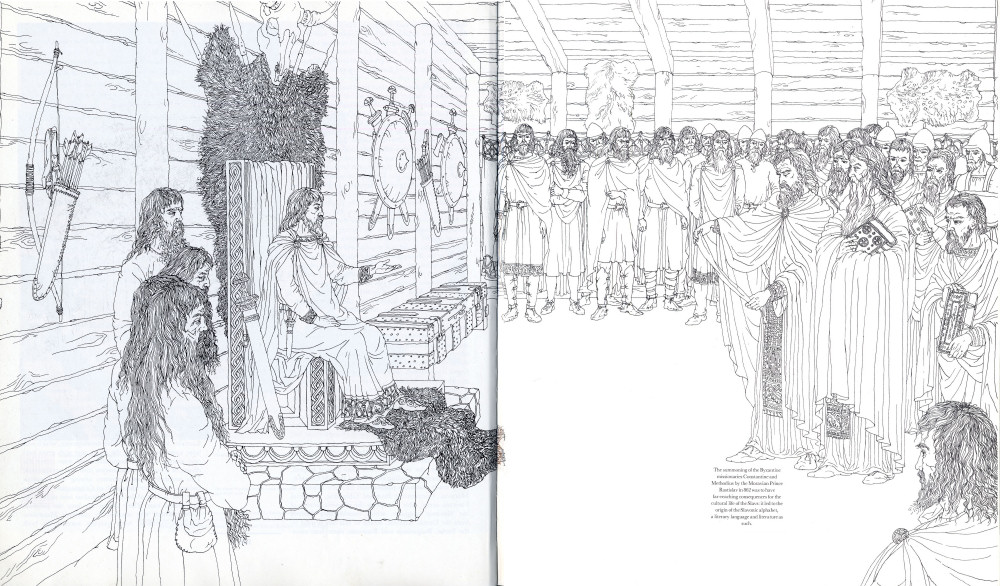

The summoning of the Byzantine missionaries Constantine and Methodius by the Moravian Prince Rastislav in 862 was to have far-reaching consequences for the cultural life of the Slavs: it led to the origin of the Slavonic alphabet, a literary language and literature as such.

The Moravian state reached the height of its power under Rastislav's successor Svatopluk (870—894), with whom the Franks were forced to conclude a peace treaty in 874, in which they acknowledged the independence of Moravia. At that time the Moravian estates stretched from the Elbe and Saale in the west as far as the upper Bug and Styr in the east and to the Danube and Tisza in the south. Decline, however, was soon to set in: a tragic conflict broke out between Methodius, who had been appointed Archbishop of Moravia, and Svatopluk. It came to a head after the death of Methodius (885), when his disciples were expelled from Moravia and the Slavonic liturgy was no longer permitted. The Slavonic priests, thereupon, continued their work in Bulgaria. With the death of

109

![]()

Svatopluk the decline of the Moravian state continued, and it was given its death stroke when the Hungarians invaded in the early tenth century.

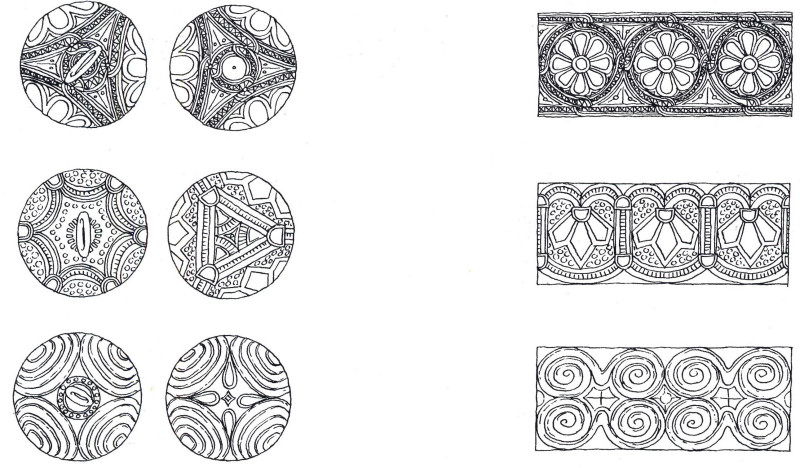

Gold and silver jewelry testifies to the high level of craftsmanship in the Great Moravian Empire. Highly individual forms were applied to belt mounts and strap ends (Staré Město).

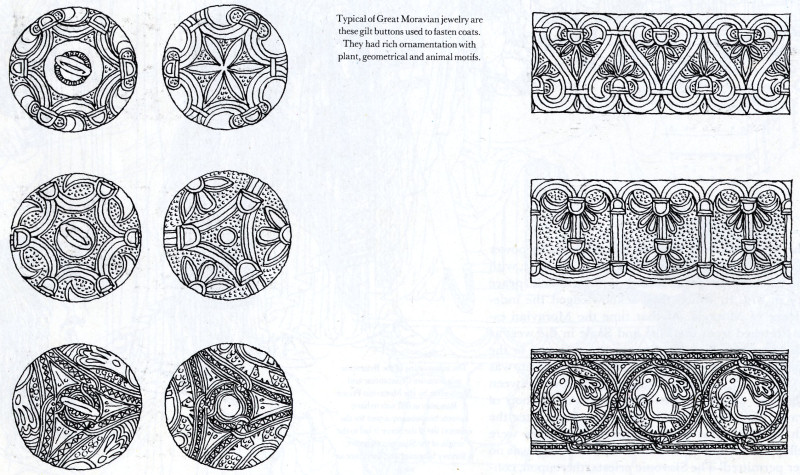

Typical of Great Moravian jewelry are these gilt

buttons used to fasten coats. They had rich ornamentation with plant,

geometrical and animal motifs.

The most important archeological contribution to the problem of Great Moravia was made by excavations carried out at its very centre. In written sources there exist only vague clues, which did not make it possible to identify its precise extent. The Annals of Fulda Abbey, one of the important ninth-century sources, relate that in 869 the youngest son of the Frankish King Louis the German, Charles, "came with the troops he had been put in charge of to that ineffable fort of Rastislav's, so unlike all old ones". The writer does not mention whether Charles managed to capture the fort, whose mightiness amazed the Franks and the Alamanni. It is more likely that he was driven off and resorted to ravaging the surrounding countryside, which was regarded as victory. Two years later Rastislav's nephew, Svatopluk, set free from Frankish imprisonment, returned to Moravia at the head of the army of Louis' eldest son, Carloman, allegedly to put down the rebellious Moravians. But when they entered "Rastislav's old town"

110

![]()

— as the Fulda annalist called the unknown castle — he turned on the Bavarians with the aid of the Moravians and completely overwhelmed them.

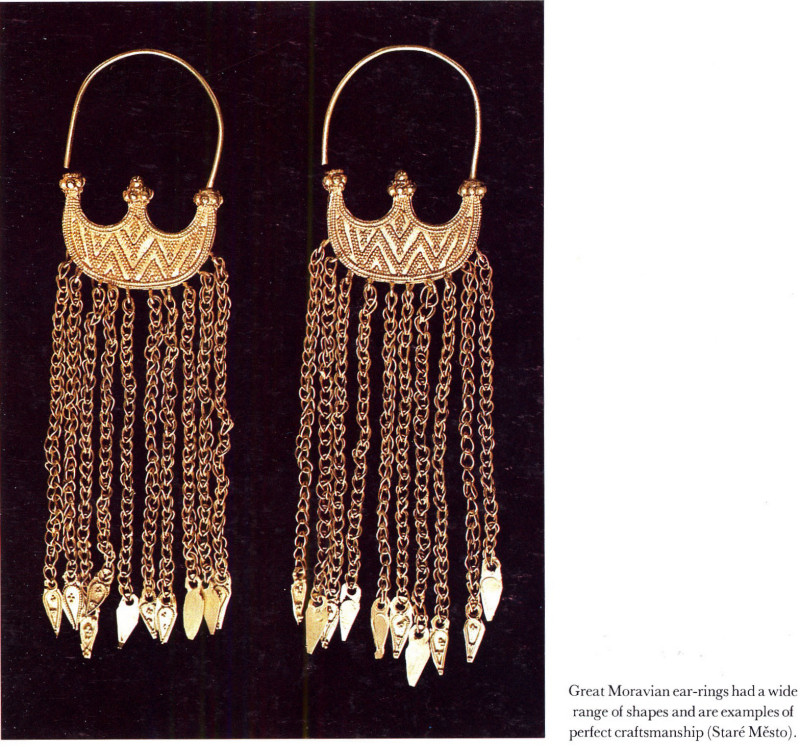

Great Moravian ear-rings had a wide range of shapes and are examples of perfect craftsmanship (Staré Město).

These are two important records of the existence of centres of the Great Moravian Empire. To them might be added one other older report, from the year 864, when Louis the German "besieged Rastislav in some town, which in the tongue of that people is known as Dowina". It must have been Devin, on the confluence of the Morava and Danube, where archeological excavations have, in fact, brought to light fortifications from the period of the Great Moravian Empire. But where was that "ineffable fort" and "Rastislav's old town"? Historians have long held discussions but matters did not become clear until modern excavations produced a better idea of that first political unification of the Slav tribes on the territory of Czechoslovakia.

The search for the "ineffable fort" takes us to the meadows and woods along the river Morava, where close to Hodonín the hill-fort of Valy near Mikulčice spread over an area of about 200 hectares (about 490 acres).

111

![]()

Today it is a Czech National Cultural Monument visited by large numbers of tourists. The complex was formed by the castle itself surrounded by a group of fortified settlements all lying on an island formed by the river. It had undergone a long development, at the beginning of which stood a simple village with pottery of the Prague type, which in the seventh and eighth centuries was replaced by a group of settlements with a castle fortified by a palisade. It was the seat of the prince and his retinue; their presence is proved by numerous finds of ancient iron and bronze spurs with hooks. At that time the inhabited area encompassed 50 hectares (125 acres), which for its period was quite an exceptional concentration of dwellings. The population lived in log cabins with trodden earth floors, occasionally also in semi-subterranean dwellings. In the earlier period they used pottery with a smooth black surface and polished patterns; later pots were made on the wheel and decorated with wavy lines. Apart from spurs, dating is made easier by finds of cast bronze trimmings with plant and animal motifs as well as other bronze jewelry, which are typical of the Slavo-Avar culture that flourished in the seventh and eighth centuries in the Carpathian Basin. These artefacts were not imported to Mikulčice but were produced on the spot, as shown by finds of small crucibles in stone ovens. A whole workshop has even been found with indications that copper, iron and gold were once smelted and worked there.

At the turn of the eighth to ninth century, when Charlemagne destroyed the power of the Avars, the hill-fort underwent far-reaching changes. It was surrounded by a stone wall, supported by a structure of timbered compartments, strengthened with stones and clay. For the first time here appeared a type of earthworks that developed in the Czech lands throughout the entire early Middle Ages. The surrounding settlements and seats of chieftains were similarly fortified, and this gave rise to the enormous fortified area, which in the Slavonic world can only be compared to Staré Město in Moravia and others at Pliska and Preslav, the main towns of the first Bulgar Empire.

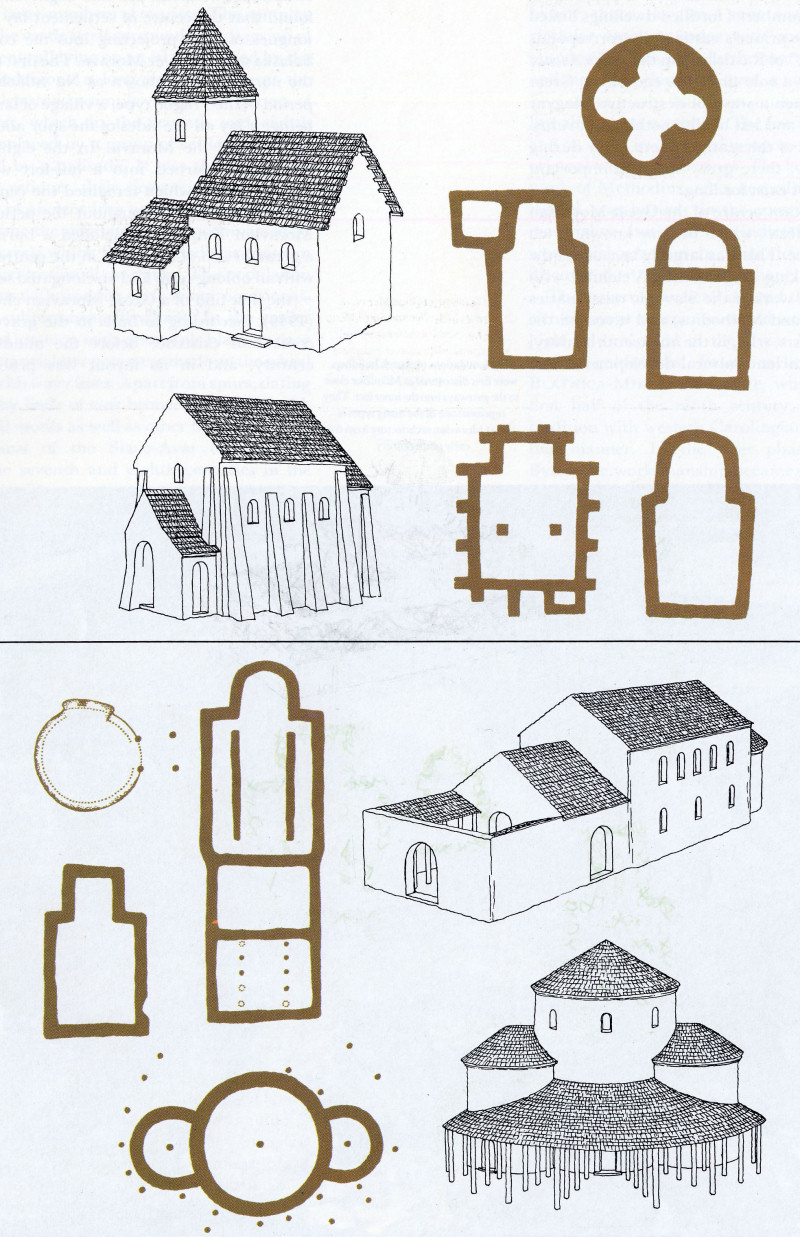

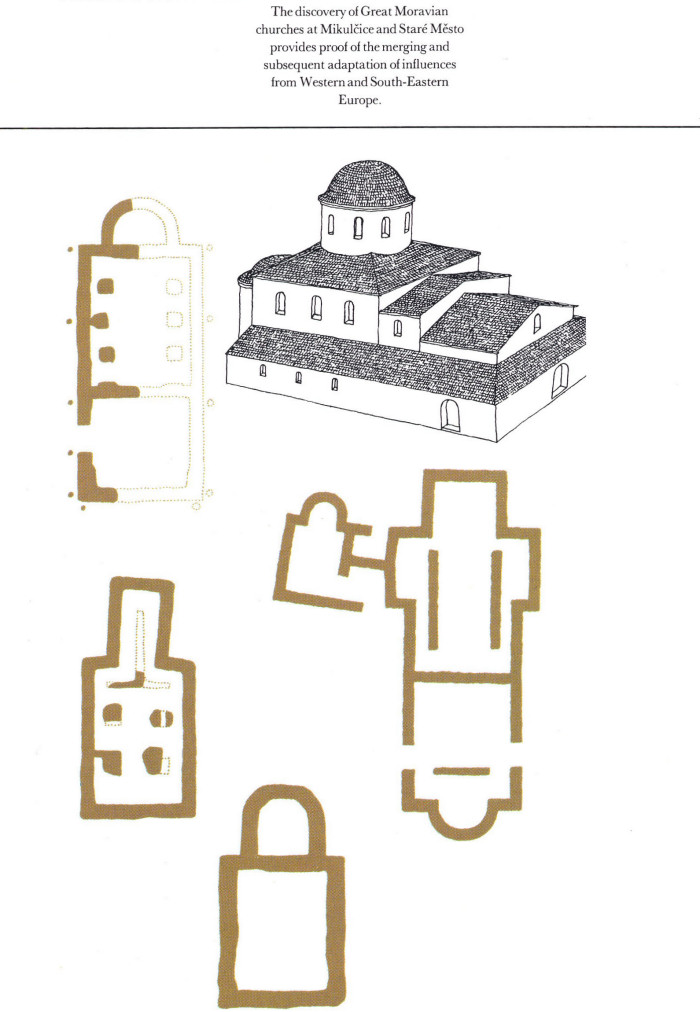

Until excavations were carried out at the Great Moravian centre at Mikulčice and Staré Město experts had been convinced that the first Great Moravian churches were made only of timber and that building began only in connection with the mission of Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius. The discovery of the first stone church at Staré Město was, therefore, taken to be an exception. But when such discoveries increased in number, it became necessary to make a new assessment as to the origin of stone architecture in the Czech lands. This was particularly necessary in view of the find of twelve churches at Mikulčice alone. They survived mostly only in negative (removed) foundations, but it became possible to reconstruct not only the ground plan but to a large extent also the original appearance of these buildings. They had a variety of forms: apart from longitudinal buildings mostly with a rectangular presbytery, there was also a square structure with a semi-circlular apse, rotundas with one, two and even four apses or conches, and, furthermore, a basilica with nave and aisles, an elongated apse, a narthex and an atrium. Five stone tombs had been sunk into the mortar floor, but all had been robbed. The few remnants of gold, gilt and or silver jewelry and weapons help one imagine the original wealth of offerings. The hope of discovering the tomb of Methodius, who, according to an old Slavonic legend, was buried "in the apostolic church", did not materialize, but there are indications that the basilica was a bishop's church; in its vicinity a baptistery was discovered — a christening chapel with a font.

There were graves all around the church, often with rich offerings of ornaments and weapons, as proof of the high cultural level of the Great Moravian craftsmen, mainly goldsmiths. In its earlier phase, called the BLATNICA-MIKULČICE GROUP, which developed in the first half of the ninth century, it linked late Avar tradition with western Carolingian influences in a creative manner. In the later phase, the influence of Byzantine worksmanship became stronger as a result of the contacts that Rastislav established. But in their workshops the Old Moravians re-worked all these foreign stimuli into a style of their own, which combined influences from South-Eastern and Western Europe.

A lively discussion arose about the origin of the Mikulčice churches, and no conclusion has so far been arrived at. Views have been expressed about the types with rectangular presbyteries having a connection with the Irish and the Bavarian missions. It has also been claimed that their southern origin from the Adriatic region, the land of the patriarchate of Aquileia and the Dalmatian coast is reflected in the basilica and the rotundas. There was talk about Byzantine influences — the tetrakonchos, basilica, etc. It would seem that all these three areas left their mark upon the appearance of this architecture; this is in conformity with Rastislav's epistle to the Byzantine Emperor Michael III, in which he writes that missionaries from "Italy, Greece and Germany" keep coming to Moravia. The variety of building styles is a significant proof of this. These influences, however, were modified, so that the Moravian architecture is only an approximation of the foreign patterns. Nowhere are there any identical types of buildings.

Stone was used to build not only churches but even palaces. So far only one has been unearthed in the inner fort near the basilica — it is a long building divided into sections with a mortar floor, stone fireplace and wooden posts. It must have served as residence for the prince, for the other inhabitants lived in log cabins with trodden earth floors, laid out in irregular rows along narrow streets. The total number of inhabitants of the entire settlement at Mikulčice has been estimated at two thousand, of whom more than three hundred lived in the fort proper. This will have been the residence of Mojmír

112

![]()

and of Rastislav, which, with its density of population, stone walls and the number of fortified dwellings linked into one unit with the prince's castle, fully corresponds to that "ineffable fort" of Rastislav's in the Fulda Annals. It continued to play a role until the end of the Great Moravian period, when a wave of destructive Magyar invaders fell upon it, and left behind nothing but ruins. On these, at the end of the tenth or more likely during the eleventh century, there grew up an unimportant village, which did not exist for long.

The foundations of church buildings were first discovered at Mikulčice close to the gateways into the inner fort. They represent one of the many types of Great Moravian architecture from the early ninth century.

The second important centre of the Great Moravian Empire was Staré Město, which became known much earlier than Mikulčice. This was largely because of the Church tradition linking neighbouring Velehrad with the beginnings of the work of the Slavonic missionaries Constantine (Cyril) and Methodius; and it roused the interest of archeologists, who, in the nineteenth century, found traces of an ancient cultural development. Systematic excavations did not begin until 1948. It was found that the centre of settlement lay on two parallel tongues of land projecting into the confluence of the Salaška and the river Morava. The first to be settled was the northern one, known as Na valách, where, at the period of the Prague type, a village of farmers came into being; it lay on the sides of the spur above the swampy lands along the Morava. In the eighth century this village was turned into a hill-fort with moats and wooden walls, which remained the centre of the Staré Město settlement throughout the period of the Great Moravian Empire. It included a burial ground with a great wealth of finds and in the centre stood a church with an oblong nave and an elongated semicircular apse — the first find of a Great Moravian church ever made (1949). According to finds in the graves it must have come into existence before the middle of the ninth century, and in its layout was probably linked to

113

![]()

114

![]()

a mission that came from the south-eastern Danube region.

The discovery of Great Moravian churches at Mikulčice and Staré Město provides proof of the merging and subsequent adaptation of influences from Western and South-Eastern Europe.

The second Staré Město spur, called Na špitálkách location, lies further to the south; it, too, underwent a long development, during which several smaller villages gradually merged into a hill-fort covering thirty-two hectares (eighty acres), fortified with a palisaded wall on the western approaches. Apart from a number of sites that served as dwellings and workshops, archeologists discovered a cemetery with a church, which had a long nave with pillars, a shorter apse and a narthex on the western side, added at a slightly later date. Graves with gold and silver jewelry, which surrounded the edifice, date from the second half of the ninth century.

Other churches were discovered in the close vicinity of Staré Město. In the first place, a church of elongated ground plan with four internal pillars and a long rectangular presbytery in the village of Modrá, about four kilometres (about two and a half miles) to the north-west of Staré Město. Its style aroused great interest, as it is reminiscent of churches from the time when the Irish missions were active in Europe. Such a style might have been introduced by missionaries from Bavaria, where the building traditions from the period of the Irish missions in southern Germany were kept alive. According to finds in the graves it must have already existed in the first third of the ninth century.

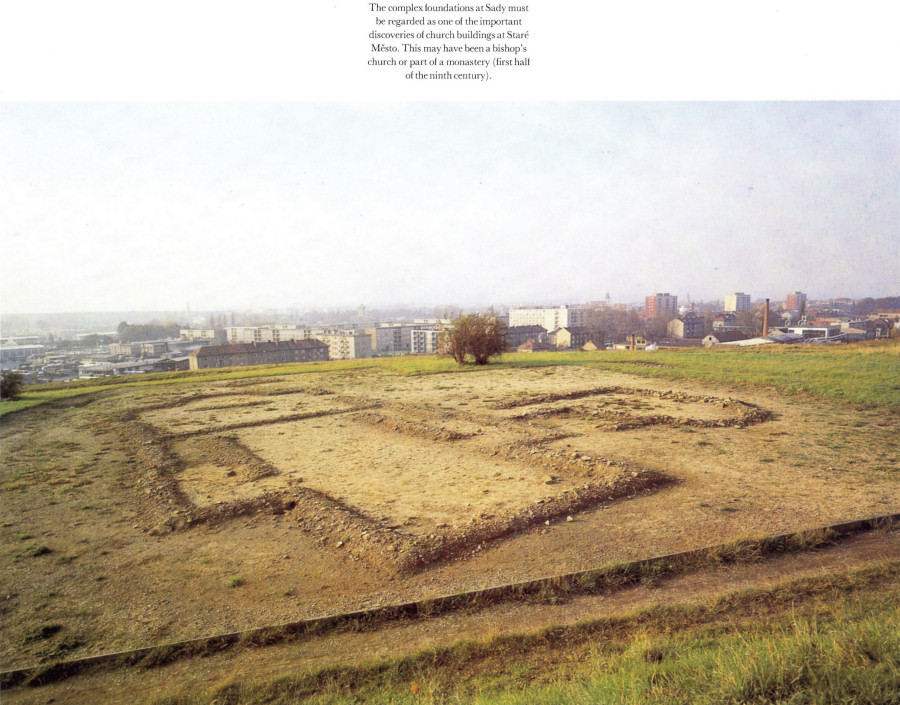

The most important ecclesiastical building that has so far been discovered in the area stands on a hill near the

115

![]()

village of Sady, some four kilometres (about two and a half miles) south-east of Staré Město. The church originally had a ground plan in the shape of an isosceles cross with a rectangular presbytery, and later a western nave was added with a semicircular apse (— perhaps evidence of a catechist school). In the final phase a funeral chapel was added to the northern wall of the transept with an elongated horseshoe-shaped apse. At that same time, a circular baptistery was built in the vicinity of the church. This entire building development took place between the end of the eighth and the last third of the ninth century. The oldest graves near the church contained weapons and jewels of Western origin, which is in accordance with the early Carolingian character of the original building. It may well be that it was founded by a bishop or was a monastery. This would be supported by the remains, close by, of wooden buildings with paved streets, a well and a wooden fence and finds of iron and bone writing tools, which were used to engrave wax tablets, or the find of a pewter cross with a Greek inscription.

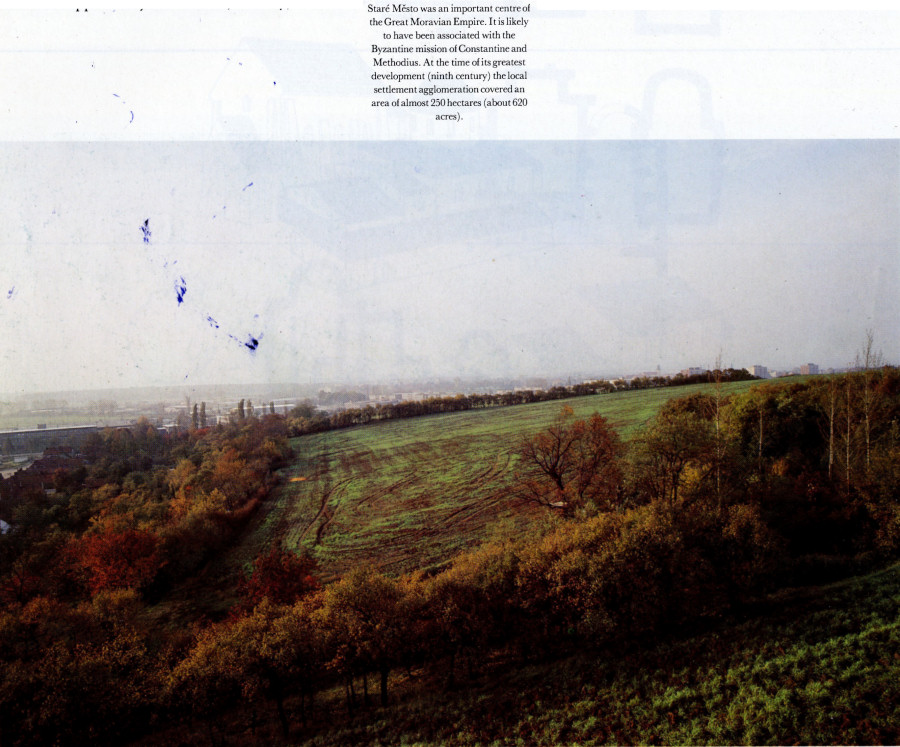

Staré Město was an important centre of the Great Moravian Empire. It is likely to have been associated with the Byzantine mission of Constantine and Methodius. At the time ofits greatest development (ninth century) the local settlement agglomeration covered an area of almost 250 hectares (about 620 acres).

There was also a rotunda in the Staré Město region, now below St Michael's Church in the area of Na dědině. It was of a different type from the one in Mikulčice (with a semicircular apse), but must relate to the missions that came "from Italy or Greece" even before the Slavonic missionaries.

The fortified town of Staré Město was surrounded by several villages in which craftsmen, such as metal-workers, smiths, founders, tanners and others, worked. The whole complex of settlements covered up to 250 hectares (over 600 acres), had a broad agricultural hinterland and well-developed forms of production specializing in luxury articles: gold and silver jewelry or fine pottery of

116

![]()

traditional shapes. The first indication of social distinctions appeared in the offerings in graves, in differentiated types of dwellings, and remains of ecclesiastical buildings in stone. These suggest that this centre must have played a leading role in the political and cultural life of the Great Moravian Empire. It is, therefore, highly likely that the brothers from Thessalonica devoted special care to the area of Staré Město, and Methodius may have been in residence here at the time when he quarrelled with Svatopluk. This is upheld also by the above-mentioned tradition of Velehrad, which, though of a later date, may have had ancient roots.

The complex foundations at Sady must be regarded as one of the important discoveries of church buildings at Staré Město. This may have been a bishop's church or part of a monastery (first half of the ninth century).

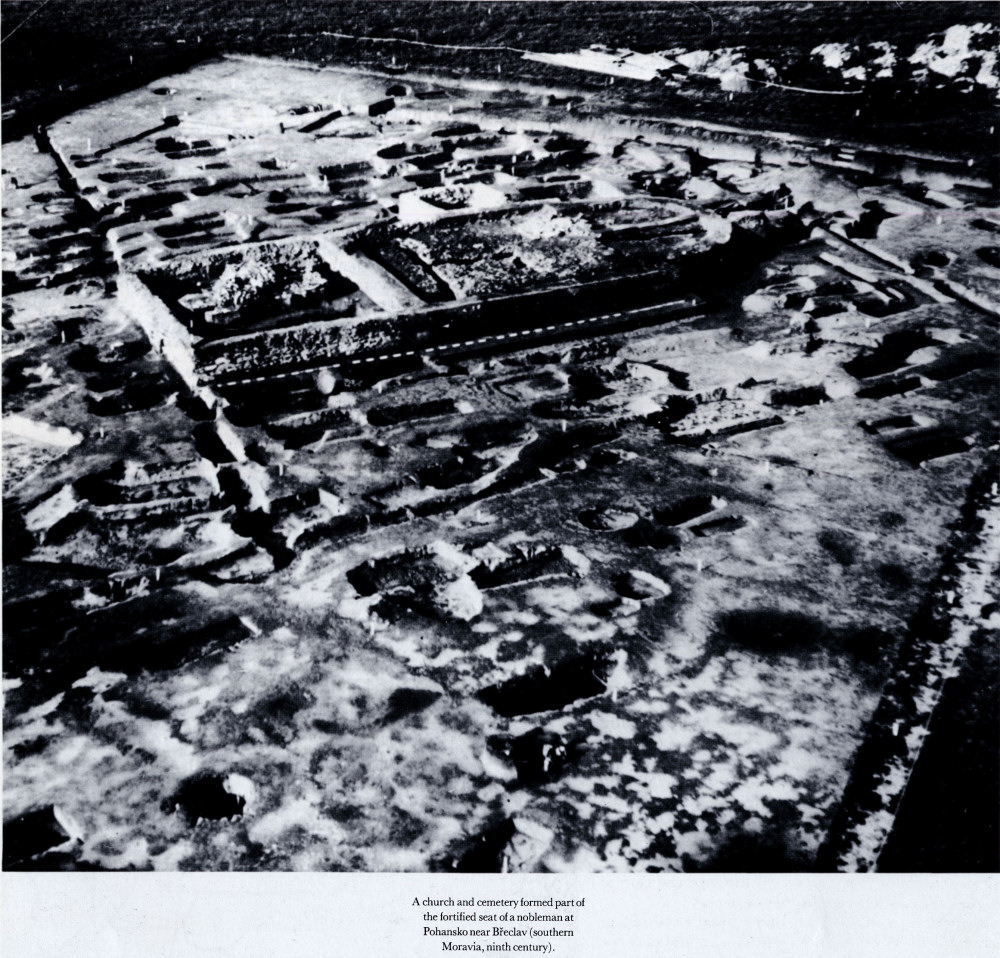

The Moravian princes must have had many other residences and centres on which their power was based. A number of these have been investigated by archeologists, even though they are on a smaller scale than Mikulčice or Staré Město. One is Pohansko near Břeclav, a hill-fort at the confluence of the Dyje and the Morava, where a homestead was discovered surrounded by a palisade, with dwellings on stone foundations and a church of elongated ground plan with a semicircular apse; in its surroundings was a cemetery with weapons and jewels of the Staré Město type. Higher up the Dyje, near Nejdek, there is another hill-fort with the name of Pohansko, where ninth-century dwellings have been unearthed. And even further upstream, in the village of Hradiště near Znojmo, further mighty fortifications were excavated, whose beginnings date from the eighth century. The grouping of these and other similar hill-forts suggests that the political and cultural centre of the Great Moravian Empire lay along the central and lower regions of the Morava. From there its influence spread in all directions, including the territory of today's Slovakia and western Hungary, ancient Pannonia.

117

![]()

A church and cemetery formed part of the fortified seat of a nobleman at Pohansko near Břeclav (southern Moravia, ninth century).

118

![]()

2. PRIBINA'S PRINCIPALITY AT NITRA AND MOSAPURC

An interesting development occurred in this area after the end of the Avar domination in the first half of the ninth century. A principality came into being with its centre at Nitra, whose first known ruler was Pribina. He worshipped pagan gods, but permitted Frankish missions since he had friendly relations with the Frankish Empire. When the Archbishop of Salzburg, Adalram, accompanied Louis the German on his expedition against the Bulgars, whose empire under Khans Krum and Omortag stretched as far as the Hungarian Tisza region, he visited Nitra on the way, since it belonged to the missionary sphere of the Salzburg metropolis, and he consecrated the first church there. This must have happened in the year 828 and it proves that Christianity existed among the Slav population of the Nitra region. This Christian core might well have been formed by small colonies of Frankish merchants. Pribina himself was not converted by Adalram.

That must have been the reason why the Franks did not come to Pribina's aid when Mojmír, the Christian prince of Moravia, attacked him after 830. He managed to expel Pribina, completed the unification of the Slav tribes on the territory of Moravia and Slovakia and thus set up a strong state. Pribina found refuge with Ratbod, the administrator of the Ostmark, where on order of Louis the German he was baptised. With Ratbod's aid, in about 840, he was given part of Pannonia around Lake Balaton as fiefdom by Louis the German. Here he built castle Mosapurc (urbs Paludarum, perhaps derived from the original Blatengrad) and eagerly devoted himself to the spread of Christianity — until 860, when he was killed during a Moravian invasion. He was succeeded by his son Kocel.

Even as part of the Great Moravian Empire the Nitra principality retained a certain measure of independence. During the reign of Rastislav it was administered by his nephew and successor Svatopluk, under whom Nitra in 880 became the seat of a bishop. According to an Epistle by Pope John VIII, this office was given to Viching, Svatopluk's confidant and an obdurate enemy of Methodius. There are no further written reports on the subsequent fate of Nitra, and so we are once again forced to turn to archeology for further evidence.

Systematic research into Pribina's seat at Nitra was started only in 1957. The seat comprises not only the area of today's town but also its surroundings, for it was shown that here was not only one castle, but a whole set of hill-forts, a system of fortifications protecting the entire Nitra countryside. The actual centre has not so far been definitely ascertained. It is not certain whether it was the hill-fort on St Martin's Hill on the slopes of Mount Zobor, which rises above Nitra, or a hill-fort in the centre of the town, where there are today modern buildings.

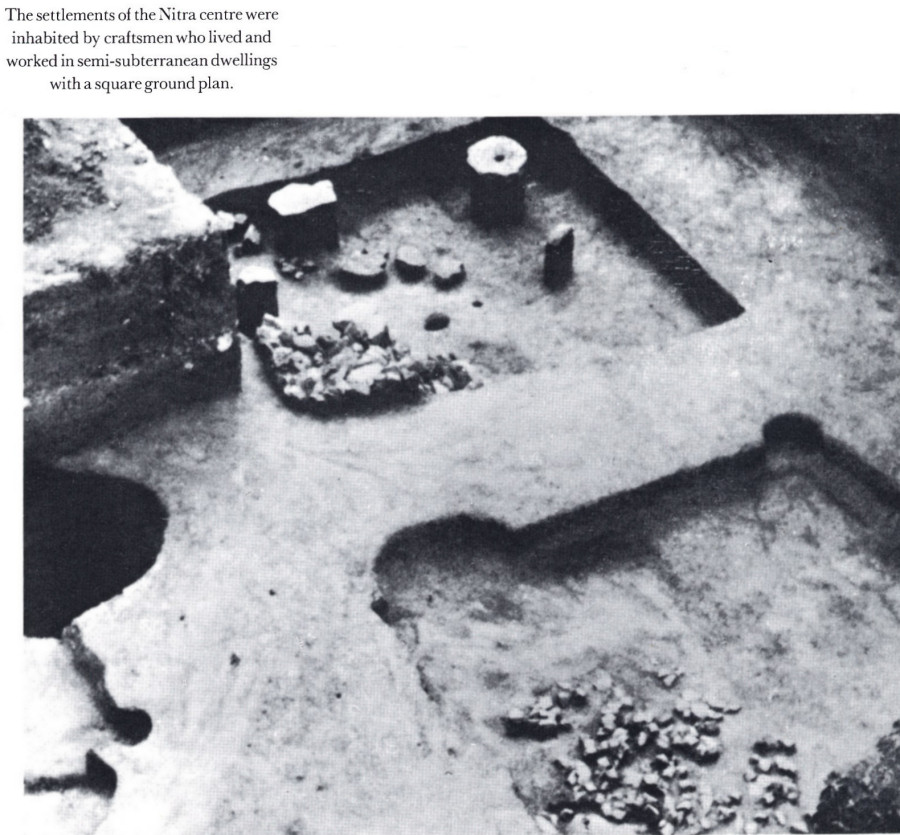

The settlements of the Nitra centre were inhabited by craftsmen who lived and worked in semi-subterranean dwellings with a square ground plan.

The hill-fort on St Martin's Hill, fortified with stone walls and a moat with mighty double palisades, encloses an area of twenty hectares (about fifty acres) and came into being in the period before the Great Moravian Empire — as shown by a cemetery with tombs of warriors from the eighth century, discovered below the hill-fort. Within the fort lived peasants and craftsmen, whose dwellings and workshops bordered a broad paved street. Beneath the former Romanesque church of St Martin on the hill-fort an older church was found with an elongated nave and three apses, two of which extended from the sides so that the resulting ground plan was that of a cross. Finds of coins of Charles the Bald date this architecture into the ninth century. But it cannot be said with certainty whether it is identical with that church which Adalram consecrated or whether this is a different one, not mentioned in the records.

The second hill-fort, in the town of Nitra itself, stood on a rocky height above the river Nitra, which provided natural protection with its flood meadows. Otherwise the hill-fort was protected by double earthworks, palisades and a deep moat. Recent construction work destroyed most of the remains of the fort but a ninth-century cemetery was found with silver and gilded jewels and iron tools of the Great Moravian type. From the large number of graves it can be assumed that there must have been a church in the western part of the hill-fort.

A whole series of hill-forts have been discovered in the surroundings of Nitra, which must have served as refuges for the neighbouring population and simultaneously protected the approach routes to the centre proper. The importance of the Nitra region is confirmed

119

![]()

not only by this remarkable grouping of hill-forts but by the concentration of unfortified peasant and craftsmen villages, twelve of which were discovered in the surroundings of Nitra alone. Beyond the Nitra region the princely power was based on an entire network of hill-forts strategically located throughout the whole of south-western Slovakia. In the middle Váh region this includes e.g. Pobedim, where swamps and strong fortifications protected a market and crafts centre with the seat of a feudal lord and another less well fortified settlement. A special role was attributed to a group of hill-forts in the vicinity of the Bratislava Gate, with its important crossings of the Danube, mainly the hill-fort at Devin, and one on the site of where Bratislava Castle now stands. Ancient Devin, at the confluence of the Morava and the Danube, served primarily military aims and is probably identical with that Dowina mentioned in the Fulda Annals in 864 as the place where Svatopluk's army managed to sink Frankish ships. Bratislava Castle is referred to in the Salzburg Annals as Brezalauspurc, and in 907 a decisive battle was fought below it between the Bavarians and the Hungarians. Excavations have uncovered fortifications of timber and earth, dwellings with stone foundations and the remains of a basilica with nave and aisles from the last third of the ninth century. The basilica stood on the highest spot of the hill-fort and indicates that Bratislava Castle was then of greater importance and not merely a frontier outpost.

Prince Pribina, as we have seen, founded Castle Mosapurc near Lake Balaton during his exile from Nitra. From there he ruled over Pannonia in dependence on the Frankish Empire. After his death his son Kocel succeeded him. Kocel played an important role in the missionary work of Constantine and Methodius and in the spread of the Slavonic liturgy and Slavonic literature. Kocel was a fervent Christian. His state comprised some thirty churches which fell under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Salzburg. Kocel was enthusiastic about the Slavonic script and the Slavonic cult and therefore received the two brothers from Thessalonica in very friendly manner when they set out from Moravia on their way to Rome; he detained them in his castle and had them teach fifty disciples. His aim was to establish an independent church province in Pannonia. Hence, after the death of Constantine in Rome, he requested the return of Methodius. He was sent to him by Pope Adrian II in 869 as his Legate and Archbishop of Pannonia and Moravia with residence in the ancient ecclesiastical centre of Srem (ancient Sirmium) in northern Yugoslavia. This roused the ill-will of the bishops of Bavaria, who imprisoned Methodius in the years 870—873. Kocel himself fell in the battle against the Croats in 876. His estate was later taken over by the Moravian Prince Svatopluk, who thus enlarged the frontiers of his Empire as far as the river Drava.

The centre of all these events was Pribina's Mosapurc in the swampy regions along the river Zala. The long years of effort on the parts of historians and archeologists were crowned with success when they identified a hill-fort near the village of Zalavár, some nine kilometres (about six miles) south-west of Lake Balaton, as Mosapurc.

The location of Pribina and Kocel's residence was very well protected by the many forks of the swampy river Zala, in which were islands suitable for habitation. The largest was called Vársziget ("Castle Island"), and another island inhabited in the ninth century was Récéskút. Archeologists concentrated on both places. They investigated the village of Zalavár, where they discovered a settlement with a cemetery from the tenth to eleventh century, i.e. the period when the land was occupied by the Magyars.

Excavations on Vársziget were impeded by the fact that the island had been inhabited until the seventeenth century, and consequently part of the oldest strata of settlement had been disturbed. But it was possible to distinguish remains of timber-fortified earthworks together with a gate on the eastern side. The gate was protected inside by a bastion of the same construction as those found in contemporary Bohemian hill-forts, with the one difference that no stone was used at Mosapurc. The dwellings were made of timber. They were semi- subterranean or on the surface, and probably made of logs, of which only post holes or pits with charcoal and ash survive. On the fringe a cemetery with Great Moravian jewelry was found. Its centre must have been further to the west, where Pribina's Church of Our Lady once stood, as written records reveal. Since the most easterly graves were dug into the ruins of burnt dwellings a fire must have occurred in the ninth century, probably during one of the Moravian attacks.

The most important discovery on Récéskút island was the foundations of a basilica with nave and side aisles and a three-conch presbytery, a square baptistery, added to the south-western corner of the church. This stone structure, built in the eleventh century, covered an older wooden church, where two phases were distinguished — the older from the turn of the eighth to ninth century, probably related to Western missionaries, and the younger, with a timber and stone construction, which must be identified with Pribina's Church of St John the Baptist. A cemetery lay adjacent to this church of the same type as the one found at Vársziget.

Mosapurc-Zalavár retained its importance as centre of Pannonia until the end of the ninth century, when new invaders appeared on the steppes of the Hungarian Plain: the nomad Hungarians. Like all previous nomads they came from the Ukrainian steppes through passes in the Carpathians and set up a base for devastating raids in the Carpathian Basin itself, mainly its eastern part. From there they attacked the whole of Central Europe as far as southern Germany and northern Italy. The Great Moravian Empire, torn by vehement disputes among Svatopluk's successors, was broken up; all the mighty and rich centres mentioned above fell into decay. What is remarkable, however, is that the one-time residence of

120

![]()

The residence of the exiled Nitra Prince Pribina and his son Kocel stood, in the ninth century, in the marshlands along the Zala near Zalavar not far from Lake Balaton in Hungary. It was known as Mosapurc.

121

![]()

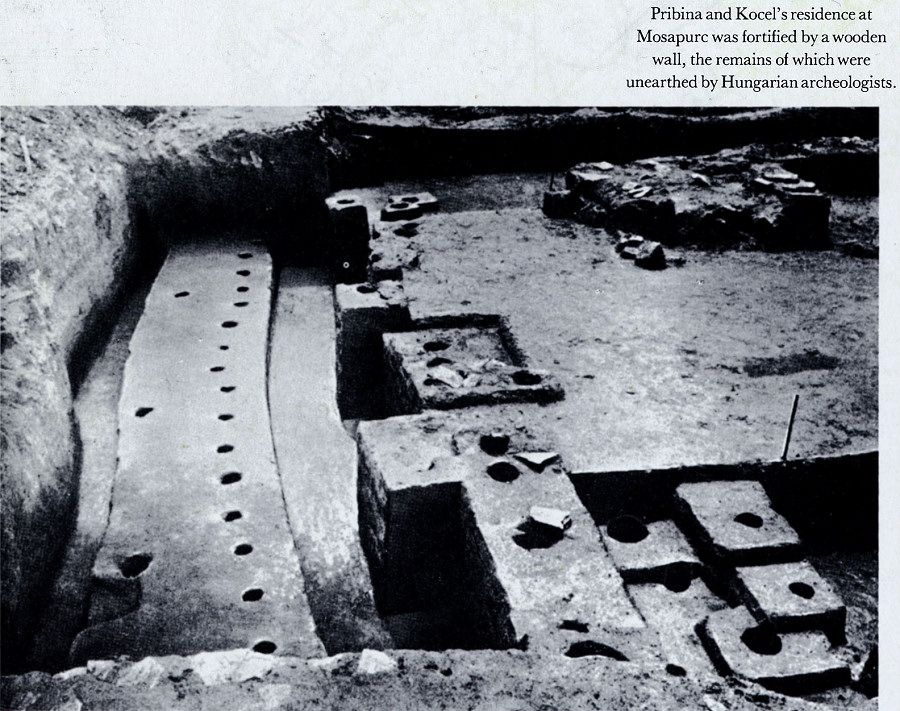

Pribina and Kocel's residence at Mosapurc was fortified by a wooden wall, the remains of which were unearthed by Hungarian archeologists.

A basilica with nave and aisles stood in the eleventh century on Récéskút island, which formed part of Mosapurc Below it the remains of a wooden church from the time of Pribina have been found.

Pribina and Kocel in the swamps of the Zala remained basically untouched by the Magyar raids. Excavations have shown that the Slav population did not abandon the site, even when they grew much poorer under the changed circumstances. Anthropologically and culturally they survived until the eleventh century, although elsewhere an intermingling of Magyar and Slavonic elements occurred, whose archeological expression is the BIJELO BRDO CULTURE. The local church also continued to fulfil its function; Christianity became cruder and certain pagan customs re-emerged in burial rites. When the Hungarian state began to form after the raids were over at the end of the tenth century, by which time the nomads had settled and adopted Christianity from the Slavs, a fortified monastery was built on Varsziget at Mosapurc under King St Stephen. Re mains of this were found during excavations. Furthermore, they unearthed a cemetery chapel, whose simple, elongated ground plan and semicircular apse follows the older Danube and Great Moravian tradition. Thus for two hundred years after the death of its founder Pribina's Mosapurc remained an important ecclesiastical and political centre, which contributed a Slav element to the cultural development of the Hungarian nation.

122-123

![]()

3. THE CROATS AND SERBS, THEIR POLITICAL AND CULTURAL EMERGENCE

The spheres of interest of the Frankish and the Byzantine Empires overlapped on the Dalmatian coast, inhabited largely by Slavs, in the ninth century. The Byzantine cities on the coast made a considerable cultural impact upon the local Slavs even if Dalmatia and Croatia ultimately became part of the cultural sphere of the West.

From the end of the eighth century on, the struggle for power between the Frankish and the Byzantine Empires took place on the territory of those Slav tribes which came to for-m the nations of present-day Yugoslavia. Until that time Byzantine influence had been predominant, interrupted only temporarily by the Avar invasion. But in the seventh century, under Emperor Heraclius (610—641), the Croats, with the help of the Serbs and the support of Byzantium, drove the Avars from the whole of north-western Yugoslavia and southern Austria, where the Slovenes then established themselves. Under Charlemagne (771—814) the Franks came to this area. The Croats living in Pannonia, led by Prince Vojnomir, helped them destroy the Avars, but then had to acknowledge Frankish sovereignty, as did Višeslav, prince of the Dalmatian Croats. The Franks then ruled over the whole of Istria and Dalmatia with the exception of the coastal towns and islands, which remained in Byzantine hands.

The Pannonian Croats rebelled against Frankish domination in 819. They were led by Ljudevit, who tried to rally other tribes to his side, including the Carinthian and Styrian Slovenes and the Dalmatian Croats, whose Prince Borna he defeated. The centre of this ephemeral state was Sisak near Zagreb. After several expeditions under Louis the Pious Frankish power was re-established, and Ljudevit, who had had to flee to the Serbs and Dalmatia in 823, was murdered. The Dalmatian Croats continued to have their local ruler, with his seat at Nin, where an independent Croatian bishopric came into being. For Christianity had already spread throughout this region in the seventh century under the influence of the coastal towns. The Byzantine towns along the Adriatic proved greatly attractive to the Dalmatian Croats and were of far greater significance than the nominal Frankish domination. The Dalmatian princes maintained friendly relations with the Byzantines and for that reason transferred their seat to Klis in the vicinity of Split, which was already the seat of an archbishop and the centre of Byzantine power on the Dalmatian coast.

No change occurred until 864 when Domagoj became ruler in Dalmatia and drove out Zdeslav, who was friendly with the Byzantines. Domagoj then rebelled against Carloman, the successor of Louis the German, whose army was defeated by the Croats in 876, at the very battle in which the Pannonian Kocel met his death while helping the Franks. Byzantium made use of the weakness of their Frankish opponents in 878 to realize its aims in Croatian Dalmatia, using the services of the exiled Zdeslav. But in the following year Zdeslav was defeated by Branimir (879—892), who, with Bishop Theodosius of Nin, led the anti-Byzantine opposition. The fate of Croatia was decided at this time — its

124-125

![]()

adherence to the sphere of Western culture, in which it remained throughout its further history, although the Slavonic liturgy penetrated here from Pannonia and has survived as a rarity to this day. A unified state linking Dalmatian and Pannonian Croatia was established by the Croats only in the first third of the tenth century — thanks to the decline of the eastern Frankish Empire and the ability of their ruler Tomislav (910—928), who became the first king of Croatia.

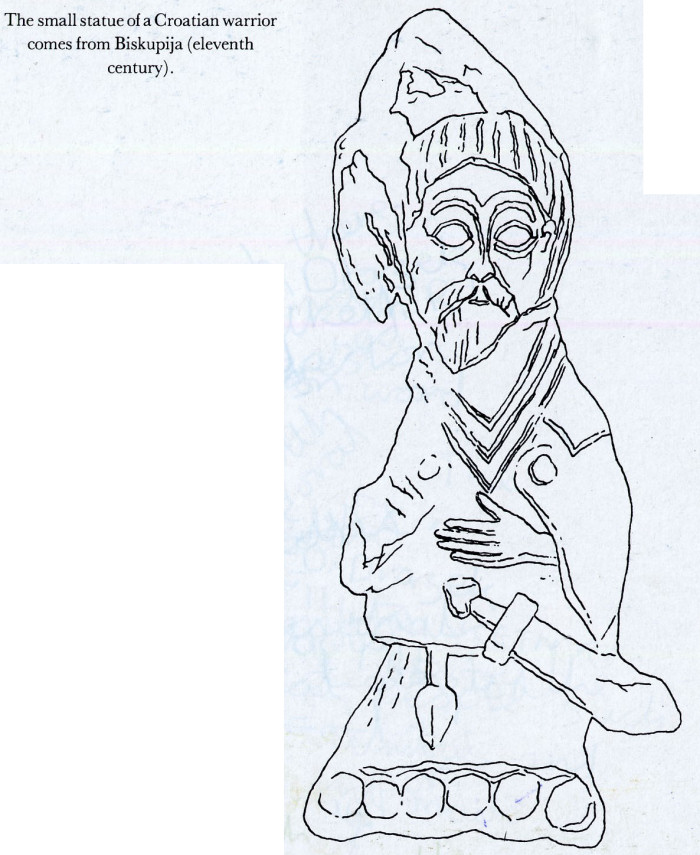

The small statue of a Croatian warrior comes from Biskupija (eleventh century).

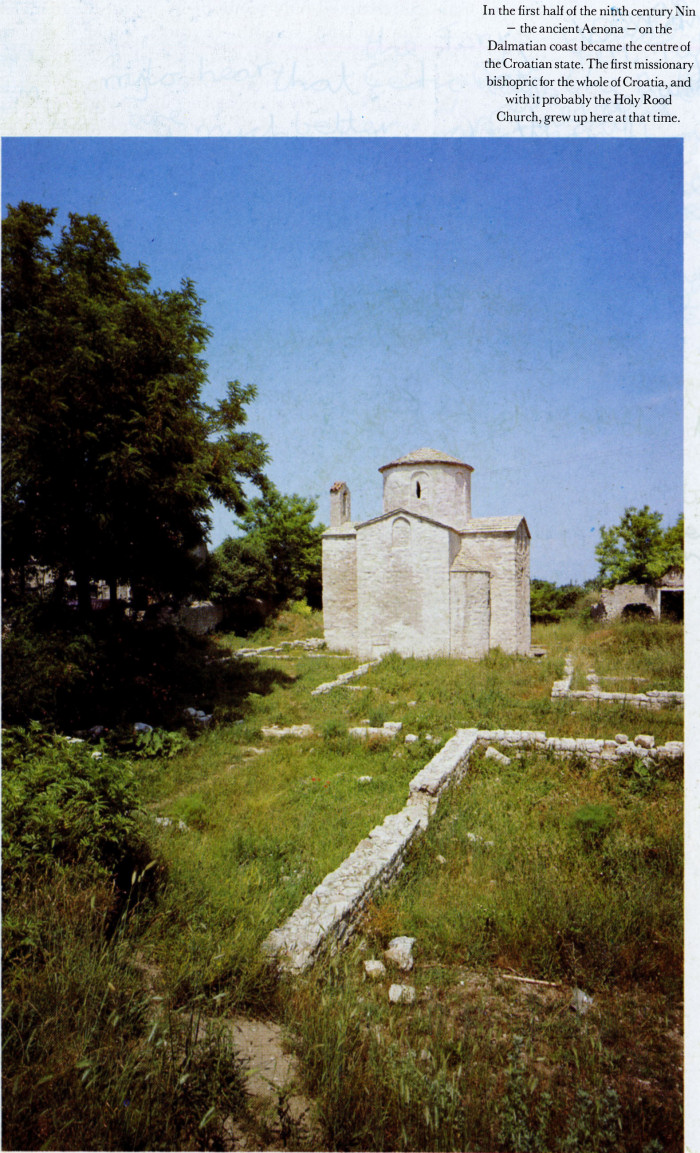

In the first half of the ninth century Nin — the ancient Aenona — on the Dalmatian coast became the centre of the Croatian state. The first missionary bishopric for the whole of Croatia, and with it probably the Holy Rood Church, grew up here at that time.

In the region of the Serbian tribes, then known by the name of Raška (Rascia), there was a different development. From the end of the eighth century on the dynasty of župans (regional administrative officers) ruled, which had been founded by Višeslav. It included names like Vlastimir, Mutimir, Strojimir, Gojnik and others. Throughout the ninth century these tribes, which later developed into the Serbian nation, acknowledged the sovereignty of Byzantium. The only exceptions were the militant Narentans who settled in the delta of the river Neretva and ruled over the adjacent islands (Brać, Hvar, Korčula, Vis, Mljet) and from there threatened the important sea-link between Venice and Byzantium. The Venetians therefore curried their favour, and in 830 they managed to persuade some of the Narentans to adopt Christianity. Mutual conflicts, however, did not stop. Not until 870 were the Narentans subdued by the Byzantine army which was fighting on the coast of Dalmatian Croatia at the time. At the end of the ninth century dynastic disputes arose in the Serbian region, in which both Byzantium and the rising Bulgarian Empire became involved, and it ended with the complete occupation of Serbia by the Bulgarian Tsar Symeon (893—927). Only the tiny princedom of Hum (Zachlumje), on the territory of what is today Hercegovina, remained to some extent autonomous. The other Serbian tribes regained their independence with the aid of the Byzantines and Croats under Ceslav (931—960). But they remained under Byzantine

126

![]()

The influence of the Adriatic coastal region spread as far as Central Europe and left a mark on the development of Great Moravian architecture. The precursor of the rotundas can perhaps be traced to St Donatus's Church at Zadar from the early ninth century.

127

![]()

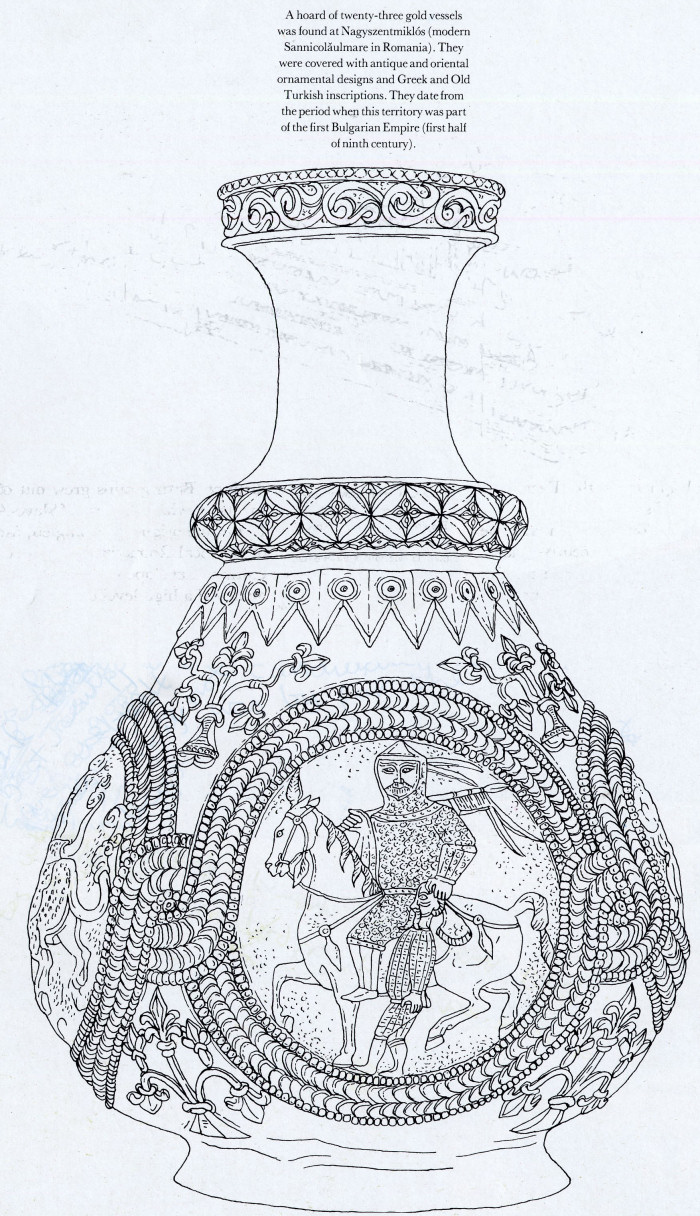

A hoard of twenty-three gold vessels was found at Nagyszentmiklós (modern Sannicolǎulmare in Romania). They were covered with antique and oriental ornamental designs and Greek and Old Turkish inscriptions. They date from the period when this territory was part of the first Bulgarian Empire (first half of ninth century).

128

![]()

sovereignty, in the cultural sphere of the East, and remained distinct from the Croats.

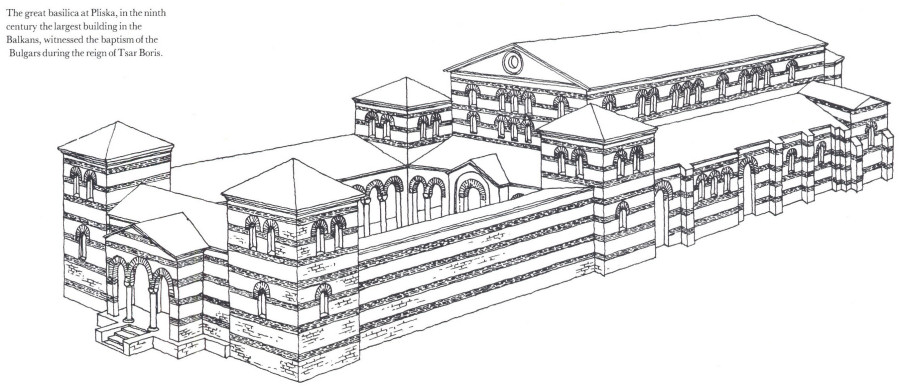

The great basilica at Pliska, in the ninth century the largest building in the Balkans, witnessed the baptism of the Bulgars during the reign of Tsar Boris.

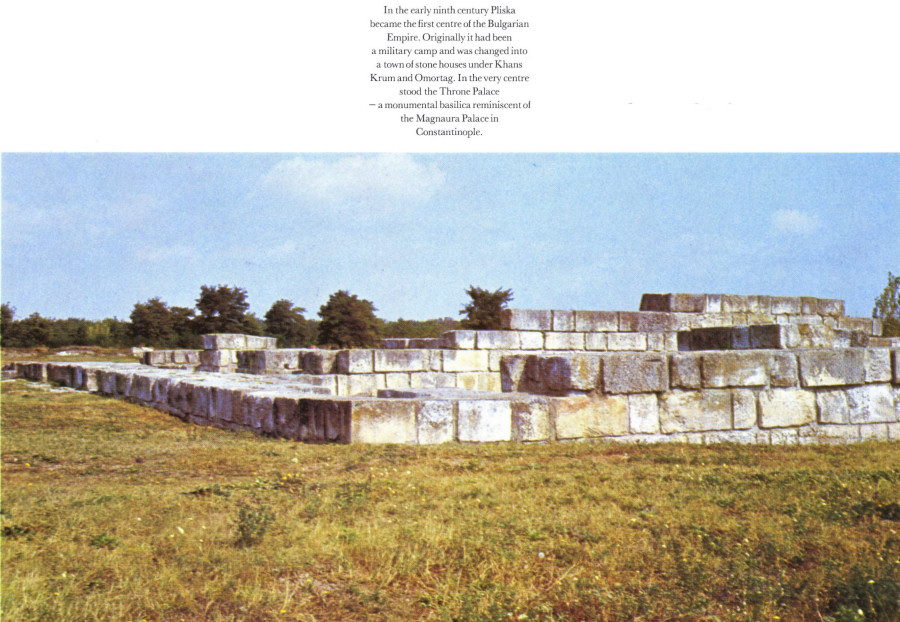

In the early ninth century Pliska became the first centre of the Bulgarian Empire. Originally it had been a military camp and was changed into a town of stone houses under Khans Krum and Omortag. In the very centre stood the Throne Palace — a monumental basilica reminiscent of the Magnaura Palace in Constantinople.

Certain features of this development can also be traced archeologically. In the ninth century local cultural groups formed, in which one might see proof of how the Croatian and Slovenian elements became distinct. Both groups grew out of these local developments, in which features of Slavo-Avar, Carolingian and Byzantine origin intermingled, including the traditions of the local Romanized population. The Old Croatian culture developed mainly in Dalmatia, where it achieved a high level e.g. in goldsmith work, and in the

129

![]()

fine arts and architecture, whose influences extended as far as the Great Moravian region. In seeking the pattern for the Great Moravian rotundas reference is often made to the Church of St Donatus at Zadar.

The Serbian region is not sufficiently known in this respect. But Slovenian culture from the ninth and tenth centuries is quite striking; it is called the KÖTTLACH CULTURE, after Austrian finds at Kottlach, or CARINTHIAN. Typical features are jewels adorned with geometrical, plant and animal motifs in multicoloured enamel. The centre of this culture was the region of the eastern Alps of Austria and Slovenia, from which it spread south to Istria and Friuli, and northwards to southern Moravia, where it is documented in the burial ground at Dolní Věstonice. Its influences can also be traced along the Danube as far as north-eastern Bavaria, settled by Slav tribes at that time.

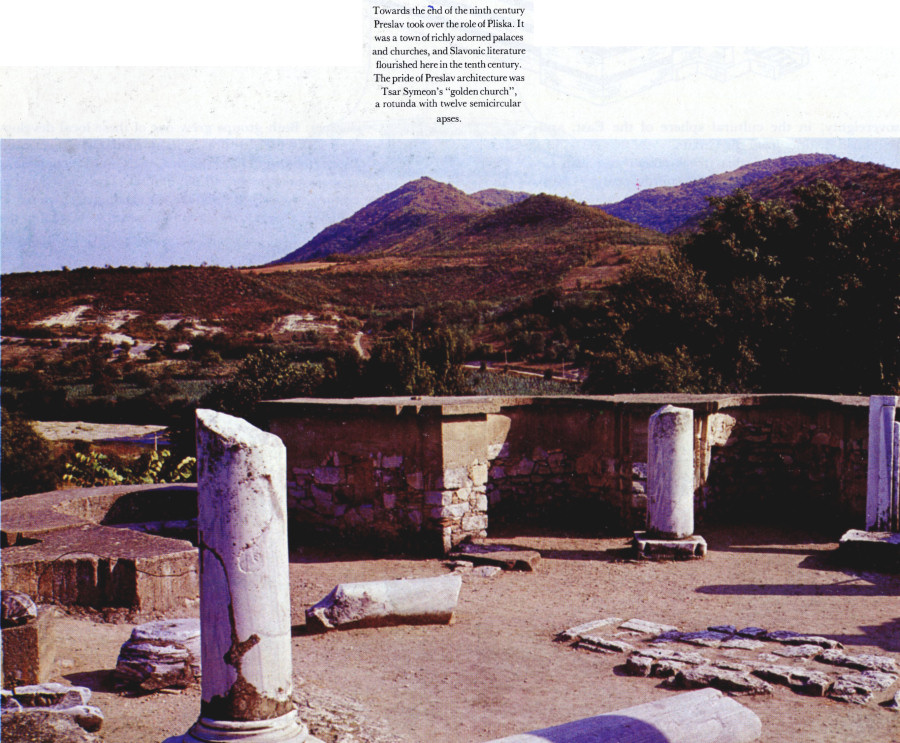

Towards the end of the ninth century Preslav took over the role of Pliska. It was a town of richly adorned palaces and churches, and Slavonic literature flourished here in the tenth century. The pride of Preslav architecture was Tsar Symeon's "golden church", a rotunda with twelve semicircular apses.

In the tenth century there arose by the side of these two cultures, in the northern parts of Yugoslavia, an independent style called the Bijelo Brdo culture (to which we have already referred) after the most important Croatian site. Here elements of Slavo-Avar, Old Croatian, and Kottlach origin merged with others from the Great Moravian Empire, and even from the Eastern Slavonic area into a new culture. Its development was aided by a historically new factor in the Carpathian Basin, the Magyars, who after heavy defeats had to come to terms with their Slav neighbours after the second half of the tenth century. Hence the whole of Hungary belongs to the sphere of the Bijelo Brdo culture, as do Slovakia and part of Romanian Transylvania, and its influence even extended to the neighbouring Slav regions. Typical features include necklaces and bracelets of twisted bronze wire, bi-partite metal pendants, bracelets with serpent heads, S-shaped ear-rings, and rings and ear-rings of every conceivable type. The traditional style of these Bijelo Brdo jewels survived on the territory of Yugoslavia into the late Middle Ages, and some features still exist in national folk art.

130

![]()

4. THE FIRST BULGARIAN EMPIRE

Out of a remarkable symbiosis of two entirely different ethnical groups on the territory of ancient Moesia and Thracia — the Turco-Tatar Bulgars and the Slavs — there arose at the end of the seventh century, under Asparuch, a state which throughout the eighth century was to cause the rulers of Byzantium great troubles. But it became a serious danger only in the early ninth century when the feared Krum (803—814) became Bulgarian Khan. He strengthened the organization of his state and laid the foundations of the Bulgarian Empire proper, which successfully competed with the two great powers of the time — the Franks and the Byzantines. In 811 he defeated Nicephorus, and later used the skull of the defeated Byzantine Emperor as a drinking cup when he feasted with his warriors. He subdued both Thracia and Macedonia, and the frontiers of his state extended to present-day Serbia and Hungary as far as the river Tisza. Krum's successor Omortag (814-831), like the later Malamir (831-852), put a stop to Frankish penetration of the Balkans and occupied part of Pannonian Croatia, including ancient Sirmium.

Under Boris (852—889) there was a strong cultural approach to the Byzantines. To curb the excessive influence of Byzantium in church affairs, Boris established contacts with Rome. His Empire became a source of conflict between the Eastern and the Western Churches until Boris, with the aid of the disciples of Methodius, found a compromise solution in the form of the Slavonic Church, which thereby became a permanent basis of the cultural development not only of the Bulgarians but of the Serbs, Romanians and Russians.

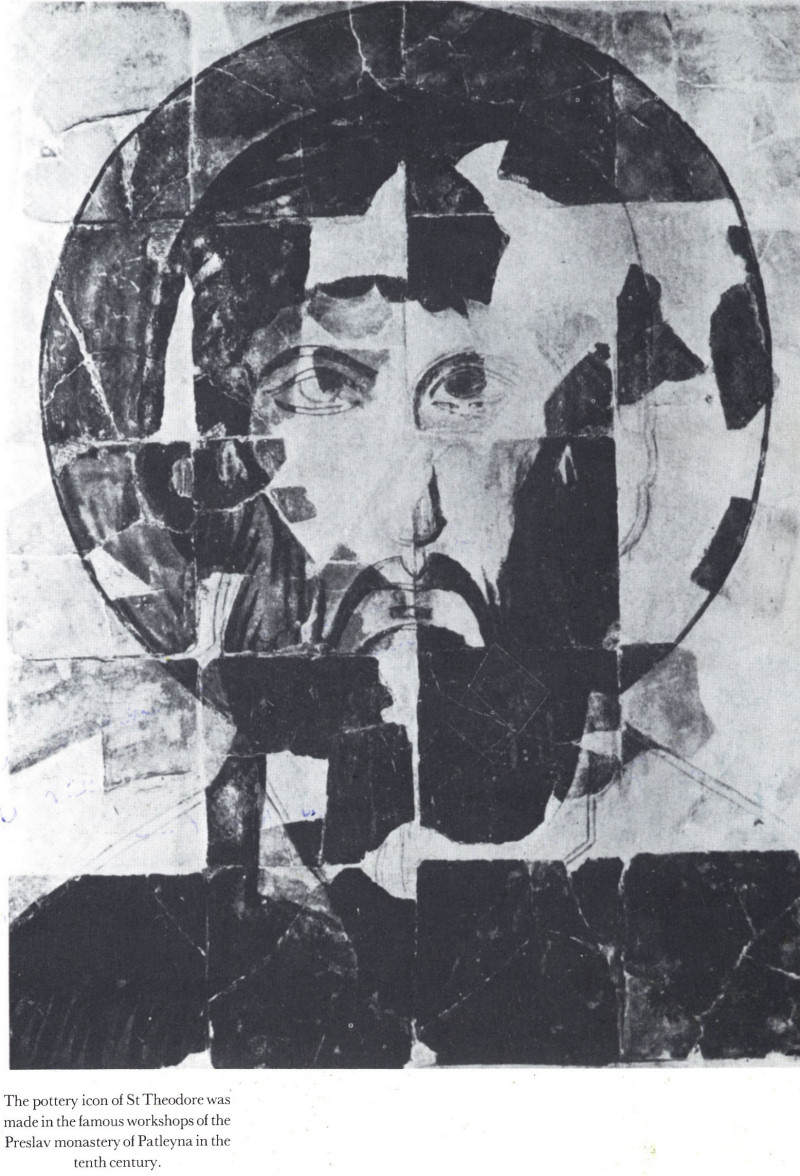

The pottery icon of St Theodore was made in the famous workshops of the Preslav monastery of Patleyna in the tenth century.

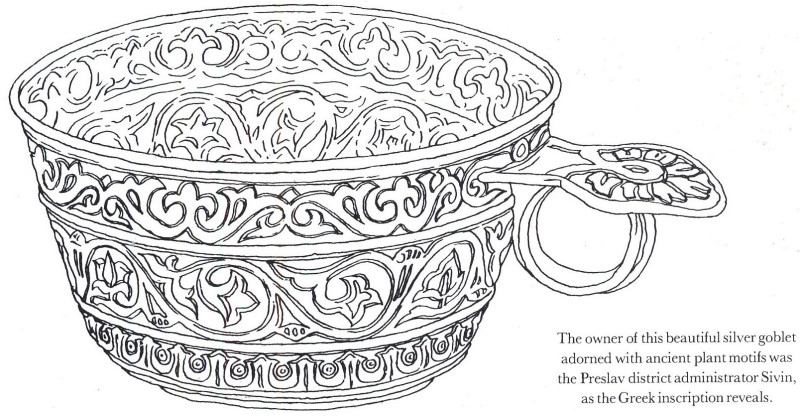

The owner of this beautiful silver goblet adorned with ancient plant motifs was the Preslav district administrator Sivin, as the Greek inscription reveals.

Boris's work was carried through to great effect by Symeon (892—927), who used his Greek education and knowledge of Byzantine diplomacy to strengthen his empire and turn it into a greater power, which began to overshadow even Byzantium itself. The Byzantine rulers vainly tried to limit his power, but even with the aid of the Magyars, Pechenegs, Serbs or Croats, their army suffered a number of humiliating defeats and Symeon very nearly achieved his aim of becoming Byzantine emperor himself. He at least managed to have

131

![]()

himself crowned as Basileus and co-Emperor with Constantine Porphyrogenitus — then still a minor. The ceremony took place at Constantinople in 913. His plans for the future were foiled by Constantine's mother Zoě, who became regent, and by his death, which occurred before he could set out to conquer Constantinople. Nevertheless, in 926, he succeeded in bringing about an important ecclesiastical and political development — the foundation of an independent Bulgarian patriarchy. Under his rule Bulgarian culture and Slavonic literature flourished, but none of Symeon's successors reached the same heights. The power of the Bulgarian state gradually weakened until, by 1018, the once feared Empire was no more than a Byzantine province.

The development of the first Bulgarian Empire is closely connected with two important centres, which for many decades have been the centre of intensive archeological work — Pliska and Preslav.

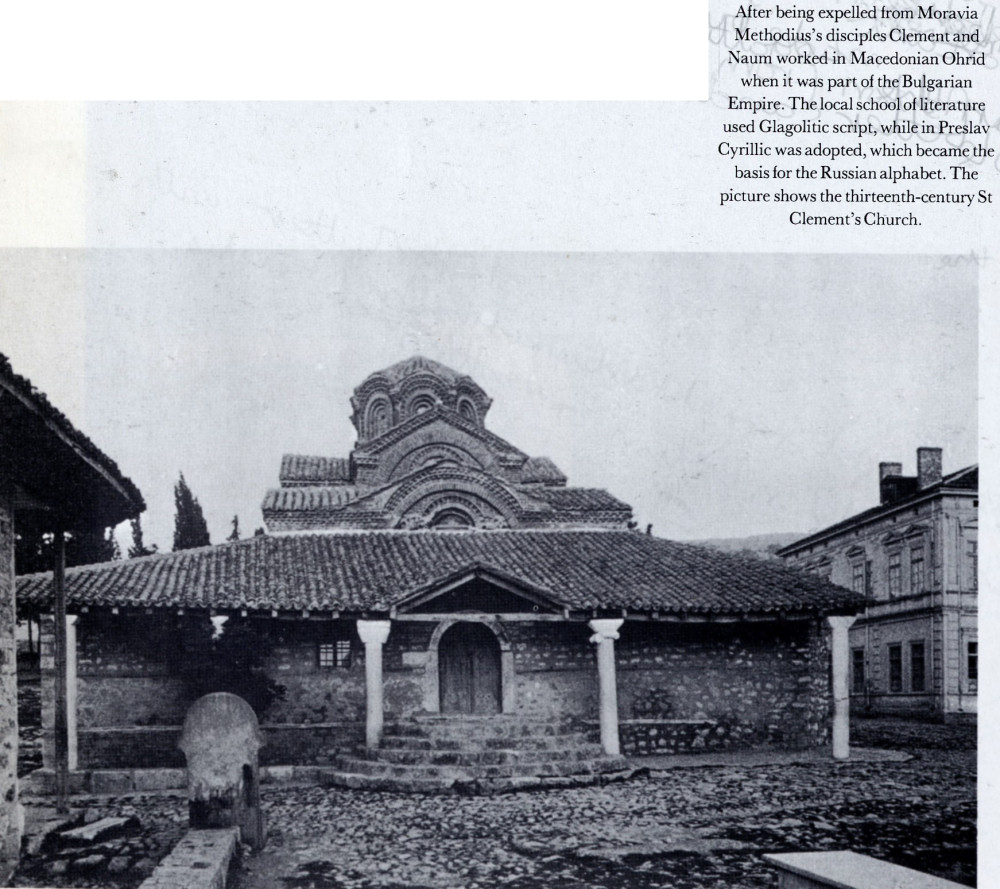

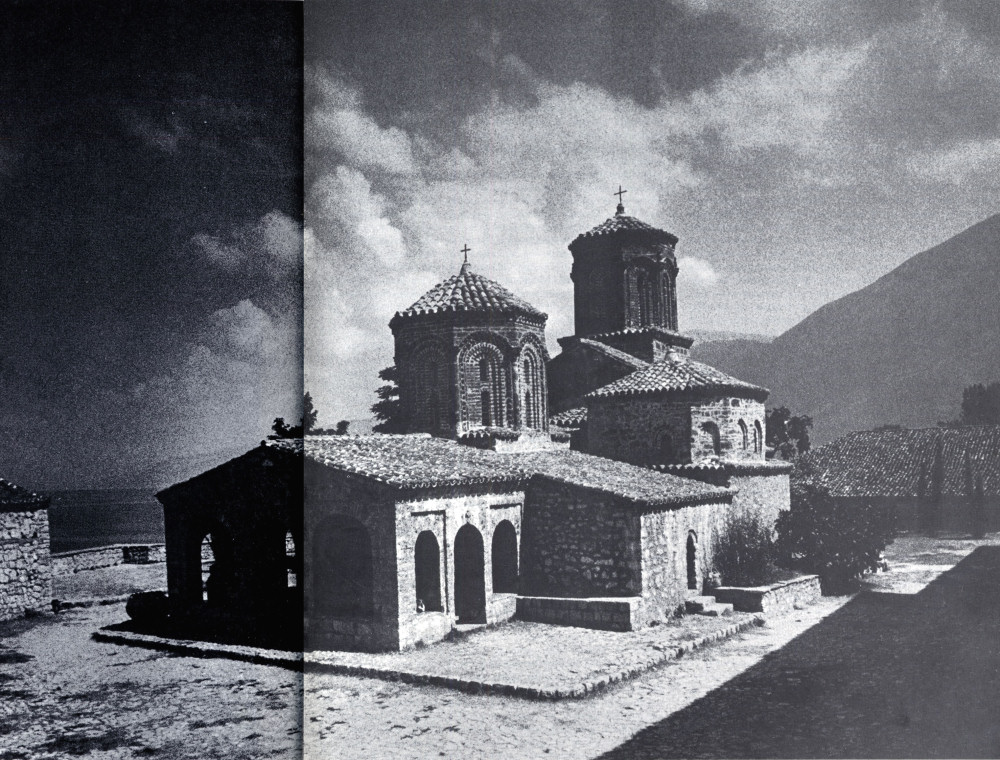

After being expelled from Moravia Methodius's disciples Clement and Naum worked in Macedonian Ohrid when it was part of the Bulgarian Empire. The local school of literature used Glagolitic script, while in Preslav Cyrillic was adopted, which became the basis for the Russian alphabet. The picture shows the thirteenth-century St Clement's Church.

According to an eleventh-century apocryphal manuscript The Vision of the Prophet Isaiah, Pliska was founded by Asparuch himself. But it would seem that originally only a large fortified military camp stood here, which was later turned into a proper town with the Slavonic name of Pliska. It must already have been in existence under Khan Krum (803-814). In 811 Pliska was destroyed by the Byzantine Emperor Nicephorus, but it soon rose again in new beauty, especially under Krum's successor Omortag (816—831). Throughout the ninth century Pliska had no rival, and when, under Tsar Symeon in 893, its role was taken over by Preslav, it still remained an important town until the end of the fourteenth century, when Bulgaria was occupied by the Turks.

132

![]()

St Naum's Monastery was founded south of Ohrid at the end of the ninth century, and the relics of this important disciple of Methodius are kept here.

133

![]()

The town was laid waste and became a wilderness, and its site was occupied only by a small village called Aboba. In 1886 the Czech scholar Konstantin Jireček recognized in the ruins around the village the remains of the first capital city of Bulgaria, and another Czech, Karel Škorpil, undertook the first excavations in the years 1899—1900. Surprising discoveries came to light of monumental architecture, showing an advanced building technology and such ostentation as was known at that time only in Byzantine towns. Excavations continued in the subsequent decades and assumed a large scale after 1944; they continue to this day.

The very size of Pliska, which lies close to the town of Shumen in north-eastern Bulgaria, is quite exceptional. With the outer wards forming an extended trapezoid ground plan, the longer sides 7 kilometres (4.4 miles) in length and the shorter 3.9 and 2.7 kilometres (2.4 and 1.7 miles), the town covered a total area of 23 square kilometres (9 square miles). This area was protected by simpler outer ramparts in the form of earthworks with a moat, such as nomad tribes used to fortify their military camps. Roughly in the centre lay the inner town with a stone wall, likewise trapezoid in ground plan, and in its centre stood the citadel surrounded by a strong brick wall. The walls were fortified with numerous towers — round at the corners, pentagonal in the centre. Furthermore the gates that led into the town from all four directions were each protected with four square towers. The greatest importance was attributed to the eastern gate, through which a wide street led to the palace. The walls were built of ashlar, laid alternately lengthwise and across, a technique known as opus implectum. This involved the stone blocks being used to face the outer and inner sides, while the interior of the walls was filled in with rubble and stones. On the other hand, the towers and gates were built entirely of ashlars, this style being called opus quadratum. This building technique was already familiar in Bulgaria in the Hellenistic period, so it must be assumed that its tradition was maintained by the Greek — and later Roman — influenced Thracian population.

Craftsmen and peasants lived in the outer town in simple huts or semi-subterranean dwellings, as known from the open villages in the Slav areas. There existed potters' workshops, metal founding, glass-making, goldsmithry, bone-carving, metal casting, all dependent on the ruling classes. With their poverty and low standard of living these people did not greatly differ from the inhabitants of the countryside.

But the inner town was a different world. Here stood the ostentatious homes of the nobility, the tsar and his boyars. First of all there was the big Throne Palace, a monumental building of two floors 52 metres (57 yards) long and 26.5 metres (29 yards) wide. It was built, according to a pattern from antiquity (it resembled the Magnaura Palace in Constantinople), as a basilica with a northern apse, and the tsar's throne stood on the upper floor. The Audience Room, inlaid with marble tablets, was reached by a stone stairway that led off the southern entrance hall. The walls were made of mighty limestone blocks, among which Roman tombstones can be found. The ceilings would have been vaulted in brick. The palace probably dates from the time of Omortag, since beneath its foundations the archeologists found an older, even larger building 74 x 59.5 metres (80 x 65 yards) in size, divided into sixty-four square sectors and with four towers. It had been destroyed by fire, and so we have every reason to suppose that it was Krum's old palace, which burnt down during Nicephorus's invasion in 811.

While the Throne Palace played a representative role, the dwellings of the rulers of Pliska lay inside the citadel. There stood a smaller palace made up of two almost identical buildings, baths heated by a hypocaust as in the Roman period, another building, barracks for the castle guard, and a water reservoir. A peculiarity were secret passages, one of which linked the small palace with Krum's palace while the other led from the small palace into the outer town. In the pagan period a temple stood near the small palace, of which only the foundations in the form of two concentric rectangles survive. Another shrine was built outside the citadel, west of the Throne Palace; after the adoption of Christianity a basilica with nave and aisles took its place, and was known as the palace church.

In the outer town a total of thirty churches have so far been excavated, associated with the smaller boroughs, feudal mansions and monasteries. They are of two types: either basilicas characteristic of Pliska, or single-naved buildings in the shape of a cross. Most of them date from the eleventh to the fourteenth century. The oldest is known as the Great Basilica; it is 99 metres (108 yards) in length and 30 metres (33 yards) in width and is the largest building of its kind in the whole of the Balkans. It is associated with the baptism of the Bulgars, for it was erected under Tsar Boris I at a time when he was intending, in opposition to Constantinople, to adopt the Latin form of Christianity. Hence this monumental basilican shape, for which a predecessor must be sought in Rome (e.g. the Basilica of S. Giovanni in Laterano) rather than in Constantinople. The church was part of a monastery, which is probably the one to which Tsar Boris retired towards the end of reign.

Apart from the foundations of buildings archeologists found a rich selection of smaller objects in Pliska, mainly of glazed pottery; and apart from traditional Slavonic and Proto-Bulgar artefacts, there were also finds of weapons, iron tools, jewelry, statuary, engravings, and dozens of Greek inscriptions, mostly from the time of Khans Omortag and Malamir. All bear witness to the high level of culture of the inhabitants of Pliska.

A typical feature of the early Bulgarian towns is the scattered layout of buildings over a wide area, differing from contemporary Byzantine or Roman towns with houses close to one another along little streets. This is true not only of Pliska but of its successor in the role of capital city — Preslav.

Preslav assumed this role under Tsar Symeon soon after 893, who — legends tell us — built this town in twenty-eight years. In reality it must have been a matter of reconstruction, since excavations have shown the existence of a fortified palace (aoul) on this site a whole century earlier. This leaves aside the traces of settlement in antiquity, which included, among others, an early Christian basilica from the fifth century on Deli Dushka Height. The reason for the transfer of the capital city must have been Symeon's consistent Christian orientation, which was opposed by some of the boyars in Pliska. This came to a head after Boris entered a monastery and handed over the throne to his older son Vladimir, who stood at the head of the pagan reaction. His behaviour forced Boris to reassume the rule, remove Vladimir and place his younger son Symeon on the throne, who took his father's intentions upon himself and brought his work to a culmination. For, as we saw above, Boris, after hesitating between Rome and Constantinople, took advantage of the fateful opportunity that occurred when Methodius's disciples were expelled from Moravia by Prince

134

![]()

Svatopluk. In this manner he saw the fulfilment on Bulgarian soil of the wishes of Prince Rastislav who had anticipated support for the political independence of the Great Moravian state from the Slavonic inclinations of Cyril and Methodius's mission. But Svatopluk foiled the attainment of this goal. Methodius's disciples Clement, Naum, and Angelarius fled and with the others found a possibility to develop their missionary and literary work fully under Boris, thereby laying the foundations of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Clement was active in Macedonian Ohrid, then part of the Bulgarian state. The second most important centre of Slavonic literature came into existence in Preslav, where, under Symeon, the Slavonic language became the tongue of state and Church. Constantine created the Cyrillic script, a simpler type of writing than the Glagolitic alphabet of Constantine-Cyril, which the Ohrid School continued to use. Cyrillic became the basis of the Russian alphabet and the script of all Orthodox Slavs in the Balkans and in Eastern Europe.

In the tenth century Preslav became the centre of the Golden Age of Bulgarian literature. Apart from Constantine, later Bishop of Preslav, John the Exarch was working here, one of the most profile writers of his time, who, apart from his own works, devoted himself to numerous translations from the Greek. A monk named Khrabr became famous for his Concerning Slavonic Letters and there were many others. The works of John the Exarch have recorded for us the enthusiastic words of admiration which the magnificence of Preslav roused in every visitor. According to his report, even outside the town gates there stood large buildings decorated with stone, wood and paint. When a pilgrim entered the inner city and saw the magnificent palaces and churches, and interiors richly adorned with marble, copper, silver and gold "he went out of his mind in amazement".

Today only insignificant ruins have survived of all this glory, which generations of archeologists have been digging out of the ground. Thanks to their efforts it has been possible to reconstruct the fortifications, which in their outer line of an irregular pentagon encompasses an area of 3.5 square kilometres (1.3 square miles) while the inner walls protected the palace complex which covers 0.25 square kilometres (15 acres). Preslav was smaller than Pliska, with which it has a number of features in common, but differed in other respects. It was not built on a plain like Pliska, but, in the manner of Byzantine cities, on terraces above the river Ticha on the slopes of the Zăbuy Mountain. Hills protected it on three sides; only to the north-east it opened on a broad valley, surrounded by mountains in the distance, with the rocky massif of Madara the most outstanding point.

The fortifications were built using the same techniques — opus implectum and opus quadratum — as at Pliska. Here, too, in the inner town stood the two-storey building of the palace (35 x 22.5 metres or 38 x 25 yards in size), with walls of ashlar, which formed the inner and external sides of the walls and were filled in with rubble and mortar. Water pipes were let into the walls. The one standing column with an ornamental capital gives an idea of the magnificence that once stood there. Slightly higher to the west on a terrace rose the "Small Palace", a basilican type of building with an apse on the southern side; it had been altered several times, and its earliest form perhaps dated from the period of Omortag. Among other buildings in the inner town there was a basilica to the south of the palace and an enormous building, 107 metres (350 feet) long, along the southern fortifications. This was divided into eighteen equal sections, each with a separate entrance and may have served as a centre of trade.

In the outer town, especially in the northern section, were the workshops of craftsmen who worked precious metals, glass, iron and clay, all to a very high level. Preslav also had numerous churches and monasteries, scattered about the town and beyond the walls along the banks of the river Ticha. A true jewel of Preslav architecture was Symeon's "Golden Church", a rotunda with twelve semicircular niches and twelve marble columns (symbols of the twelve Apostles) which supported the cupola. On the western side there was a tripartite narthex with two towers, to which later an atrium was attached, and a pillared court with a well. The entire layout followed a late Roman style. Of the other churches in the outer town some were basilicas, some domed. The basilica with nave and aisles in the north-eastern part of the town (Cheresheto) was probably built entirely of wood.

Among the Preslav monasteries, Patleyna, lying 2 kilometres (about 1.2 miles) south of the town, deserves special mention. It became famous for its workshops which produced painted pottery, used to decorate the walls of the local church of St Panteleimon (of which the name Patleyna is a corruption). An icon of St Theodore, a rare example of the artistic style of the Preslav School, has survived in relatively good condition. In the monasteries there survived a number of inscribed monuments, documenting the original form of both spoken and written Slavonic. Preslav also has Greek inscriptions, which were put on luxury objects, such as on the bottom of a silver cup belonging to Governor Sivin in the ninth to tenth century, which is a magnificent example of Old Bulgarian metalwork influenced by Byzantium.

Preslav continued to exist for centuries. At the time of the Byzantine domination in the eleventh and twelfth centuries a military garrison was stationed here; after liberation in the thirteenth century the town became the residence of Peter, brother of Tsar Asen. But it held a secondary position, since the centre of the Empire had been moved further west — to Veliko Tărnovo.

135

![]()

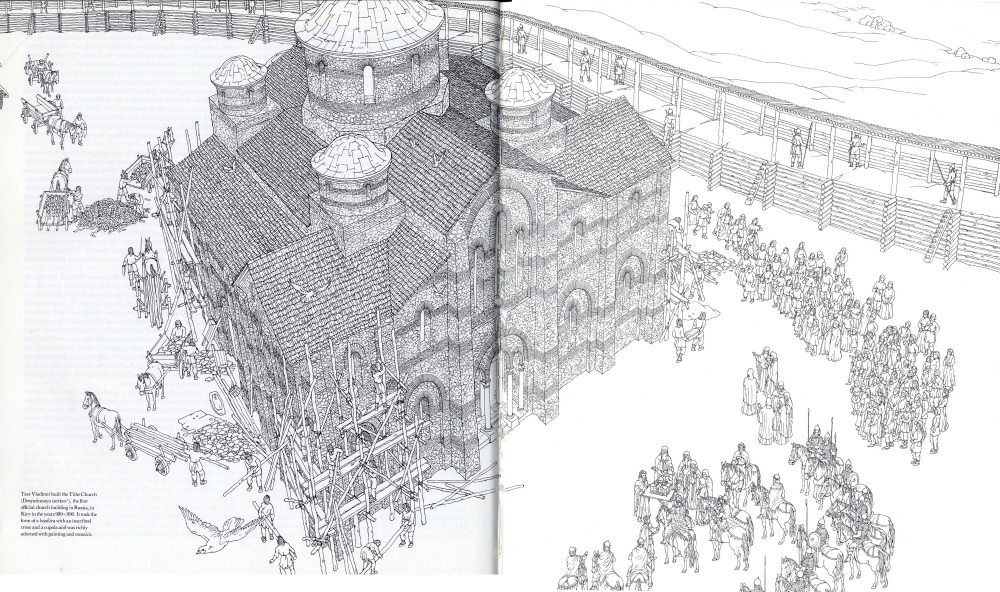

Tsar Vladimir built the Tithe Church (Desyatinnaya tserkov'), the first official church building in Russia, in Kiev in the years 989-990. It took the form of a basilica with an inscribed cross and a cupola and was richly adorned with painting and mosaics.

136-137

![]()

The present appearance of the Kiev St Sophia's Cathedral is only remotely reminiscent of the magnificent cathedral built by Yaroslav the Wise in the first half of the eleventh century.

138

![]()

5. THE EARLY HISTORY OF KIEVAN RUSSIA

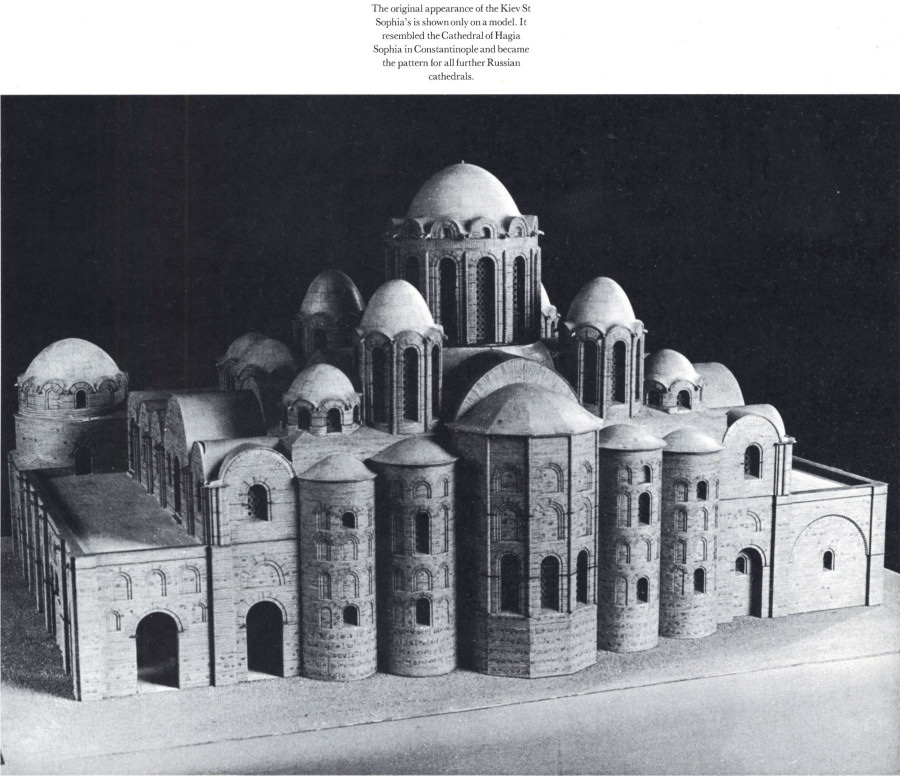

The original appearance of the Kiev St Sophia's is shown only on a model. It resembled the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and became the pattern for all further Russian cathedrals.

The broad stretches of the Russian lands are drained by innumerable rivers that merge into several mighty watercourses which ultimately flow into three seas: the Caspian, the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Most of the watercourses fall into these and, since time immemorial, they were the links between the tribes in the far North and the major cultures of the south. The Slavonic people loved these life-giving rivers and to this day show their respect in songs and herbs bearing the gentle names of "Mother Volga", "Father Dnieper", whose fertile banks have always been a source of food. And over long centuries the Slavs set out along them from their original home between the Dnieper and Dniester to the sparsely inhabited regions of Eastern Europe, while merchants came travelling on their waters from distant lands. One of the most important of the rivers was, undoubtedly, the Dnieper, running through the very centre of the Slavs' original homeland. To the ancient Greeks, who set up their trading stations and colonies along the Black Sea coast, the river was known as the Borysthenes. In the Byzantine period the Dnieper was a major trade route. Particularly in the ninth century, when the enterprising Scandinavian Varangians began their long-distance trade, most of the "routes from the Varangians to the Greeks" led down the Dnieper. Trade links spread along all its tributaries to the west and east. Soon suitable places on the edge of the steppe and the forest lands began to develop at points where the trade routes from Ukraine and Byelorussia crossed those to the Black Sea coast. In this manner the first state of the Eastern

139

![]()

Slavs arose and Kiev became its political and cultural centre. We call this state, which envolved in the ninth century, Kievan Russia.

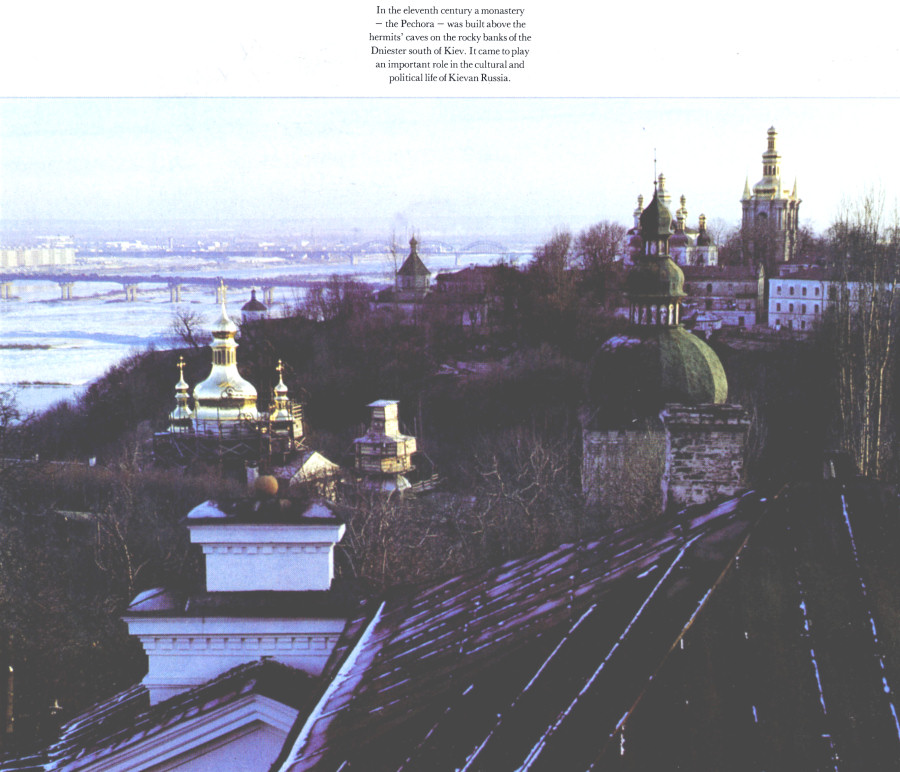

In the eleventh century a monastery — the Pechora — was built above the hermits' caves on the rocky banks of the Dniester south of Kiev. It came to play an important role in the cultural and political life of Kievan Russia.

The development of the state was determined by internal economic and social conditions and by external causes in the form of constant pressure from the nomads in the steppes, especially the Avars, Bulgars, Khazars, later the Magyars and Pechenegs, and others. For the Slav tribes, scattered into minor tribal princedoms, there arose the need for a more permanent unification, which would enable them to counter these internal and external pressures. Such was the situation when, in the ninth century, groups of Scandinavians arrived, armed military and merchant companies who followed the Volga and Dnieper in their search for a way to the rich cultures of the Near East. The customary routes between Western Europe and those areas across the Mediterranean Sea had been cut by Arab pirates. A mighty company led by Askold and Dir thus arrived in the Kiev region some time after the middle of the ninth century and formed an alliance with the local tribe of the Polyane, and they then became central to developing the organization of the state. What role the Norsemen played in this process has long been debated by historians and archeologists. What is most likely is that the Scandinavians simply took an active part in a process which was already in progress among the Slav communities and helped bring it to fruition. In no case was it a question of forceful domination, but a voluntary alliance, as between the Bulgars and the Balkan Slavs. Conjecture as to the origin of the name Russia, which soon came to be applied to the entire group of people and the whole country, has not yet been settled. It may have come from the Finnish Ruotsi for which a Swedish

140

![]()

forerunner is being sought, or perhaps it was a local tradition in relation to the river Ros', a tributary of the middle Dnieper, which seems to be suggested by certain Oriental sources. The Slavs themselves called the Scandinavians, most of whom came from Sweden, "Varyagi" (in Byzantine sources Varangoi), which is derived from varing or vaering and corresponds to the Slavonic term druzhina, "company", that is a group of armed men bound by mutual pledges and linked in a common undertaking, military or commercial.

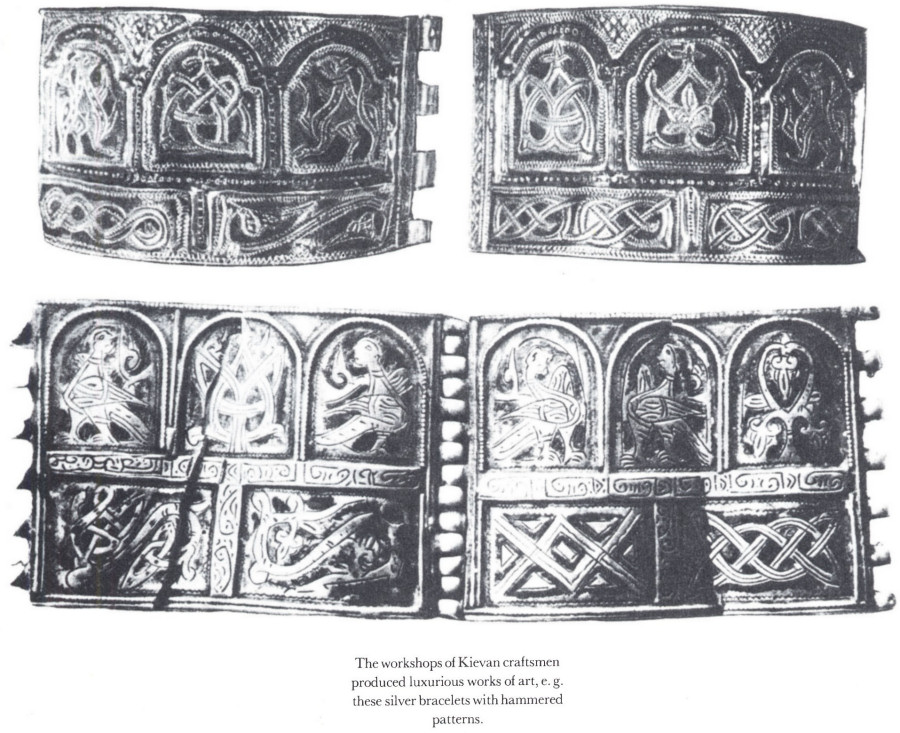

The workshops of Kievan craftsmen produced luxurious works of art, e. g. these silver bracelets with hammered patterns.

The alliance of the Varangians with the Slavs in the Dnieper region, the important north-south route to the Black Sea, soon became an unexpected threat to Byzantium. In the year 860 the Russians unexpectedly appeared in ships outside the gates of Constantinople and during the absence of Michael III, who was fighting the Arabs, very nearly took possession of the city. The Byzantines saw themselves forced to take account of this new political and military rival and concluded a treaty of friendship with the Khazars (here the Thessalonican brothers Constantine and Methodius played an important role) to keep them in check. Nonetheless, after this event, Kievan Russia became exposed to the strong influence of Byzantine culture; missionaries were sent, and in 864 a bishopric was established at Kiev. This development was forcefully interrupted by Prince Oleg of Novgorod, who some time around 880 conquered Kiev and suppressed the beginnings of Christianity.

The link between Novgorod and Kiev (Upper and Lower Russia) led to the origin of the Old Russian state proper, which by stages unified all Eastern Slav tribes. Its foundation is associated with the name of Oleg, who subdued the Drevlyane, Severyane and Radimichi, and eliminated the influence of the Khazars. He made closer contacts with the Byzantines, and in 911 (after a second unsuccessful attempt to conquer Constantinople in 907) concluded a trade agreement. Oleg's successor Igor vainly tried to break down the fortifications of Constantinople in 944. He had no choice but to continue to live in peace with his southern neighbour, whose influence strengthened particularly after Igor's death in 945, when the regency for the minor Svyatoslav was taken over by his mother, the energetic and prudent Princess Olga. Christianity began anew to penetrate to Russia; in Kiev the Cathedral of St Elias was built and Olga herself was baptised in Constantinople in 957. But when her son Svyatoslav ascended the throne (964—972) another anti-Christian reaction set in. Svyatoslav was an able warrior, who substantially enlarged his country particularly in an easterly direction. He subdued the Vyatichi, the last Slav tribe that had remained beyond the reach of the Kiev princes. He destroyed the empire of the Khazars, defeated the Bulgars in the Volga region and moved the frontier of his state as far as the Volga, the Caucasus and the shores of the Caspian Sea. His dream of founding a large Slav Empire, encompassing the Slavs

141

![]()

in the Balkans, failed, however, despite an expedition which he led against the Bulgars in the Danube region. He was prevented by both Byzantium, which realized the dangerous consequences of his intentions, and the invasion of the Pechenegs, during which he met his death.

His son and successor Vladimir (980—1015) gave Kievan Russia its final form. Once again, the rebellious Radimichi and Vyatichi were subdued and Vladimir extended the frontier of his country towards the west as far as Przemyśl and Grody Czerwieńskie in south-eastern Poland. During his reign Christianity was finally adopted in the Byzantine form, the ostentation of which impressed the mentality of the Scandinavian and Slavonic Russians. But under the influence of Bulgarian Ohrid the Slavonic liturgy was adopted and Slavonic became the language of worship. This helped the rapid spread of Christianity, the closer unification of the Eastern Slav tribes and the adoption of Slavonic ways by the Varangians. The results were similar to those in Bulgaria. Vladimir's work was brought to fruition by his son Yaroslav, who came to power after long years of struggle (1015 — 36) between Vladimir's sons. During his rule (1037—54) Kievan Russia flourished politically and culturally; the organization of state became firmly established and its borders were extended to the north and north-east. Literature, architecture, arts, and crafts developed and by establishing a metropolitan centre in Kiev the Russian Church became independent. These achievements were followed by a gradual decline. The extensive empire could not be kept together in permanent unity. After the second half of the eleventh century, independent princedoms gradually arose, most of which acknowledged the sovereignty of Kiev only nominally — except for several strong personalities, such as Vladimir II Monomakh (1113—25). This development was hastened by the invasion of the Polovtsi into the Ukrainian steppes, which caused shifts in population and the centre of the state was moved to the more northerly parts of Eastern Europe, which meant Kiev's decline. Its fate was sealed by the invasion of the Mongols in the first half of the thirteenth century.

Archeological excavations have greatly contributed to a better understanding of Kievan Russia and its centres, starting with Kiev itself. It is possible to observe archeologically how different cultural groups on the middle Dnieper, representing the local tribes, merged to produce the unified culture of the emerging state, and how the prerequisites for the rise of Kiev were formed long before the tribes actually unified. In this regard legends proved to be valuable; such as the legend of the oldest princes of the Polyane, recorded in the eighth century in the Armenian chronicle History of Taraun, attributed in part to Zenob of Glak (a legend more famously recounted in the Russian Primary Chronicle mentioned below). This tells of three brothers named Kiy, Shchek and Khoriv. The first is said to have given the name of Kiev. This legend is reflected in the archeologically proven existence of three great hill- forts on the territory of Kiev in the eighth to tenth centuries: on Andreyev or Kiev Hill (which later acquired decisive importance), on Kiselevka Hill and finally to the north-west of Andreyev Hill. These hill-forts bear proof of the local social and political

142

![]()

development, which was given a major boost by the arrival of the Scandinavians Askold and Dir, whose successors founded the first Russian dynasty.

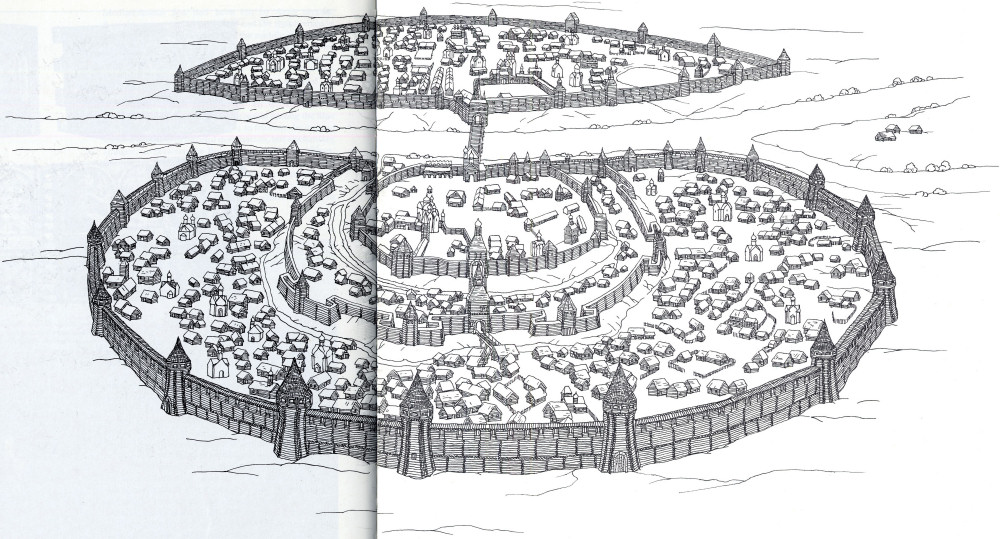

From the tenth century on Novgorod became the true metropolis of the Russian North. In the Scandinavian sagas it was called Holmgardr, and it served as a centre of long-distance trade and political and cultural life, and had an unusual city administration. The river Volkhov divided the city into two halves: the western called the Sophia Side and the eastern known as the Market Side.

Until the ascent to the throne of Vladimir the Great, Kiev Castle on Andreyev Hill was relatively small in size (2 hectares or 5 acres). Vladimir built a mighty and spacious castle with fortifications at the end of the tenth century, where his retinue of noblemen and boyars lived and, after the adoption of Christianity, the higher clergy lived too. Some time in the year 989 or 990 the Tithe Church (Desyatinnaya tserkov') was built in his residence, the first official church building in Russia, which,

143

![]()

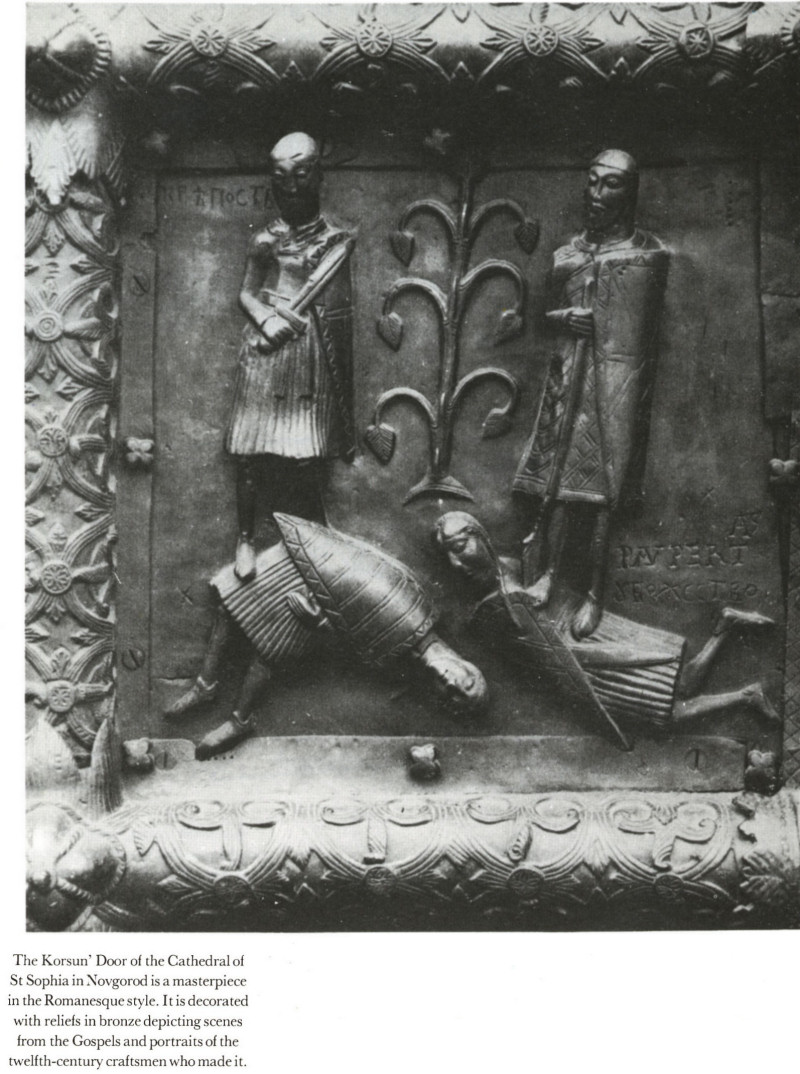

The Novgorod Kremlin is dominated by the Cathedral of St Sophia, which was built along the lines of the one in Kiev by Bishop Luka Zhidyata and Prince Vladimir Yaroslavovich in the eleventh century. Close to the cathedral stood the house of the bishop and later of the archbishop, the most powerful figure in the city from the twelfth century on.

144

![]()

at that time, served only the family of the prince. It was a basilica with an inscribed cross and cupola, erected by Greeks, and richly adorned with paintings and mosaics. The wealth of Kiev was ensured by merchants and craftsmen, who settled in the fast growing settlement below the castle called Podol, which lay to the north-east of Andreyev Hill and Kiselevka on the right bank of the Dnieper. This gave Kiev the typical polarity of the Hill as the residence of the prince and Podol as its economic hinterland.