II. THE GREAT EXPANSION BEGINS

1. The Settlement of Central Europe 29

Mount Říp rises all on its own out of the plain in central Bohemia and is entwined with legends of Old Father Czech, who alter long years of wandering from the homeland in eastern regions stood on its summit and identified the new home area of his tribe.

1. THE SETTLEMENT OF CENTRAL EUROPE

The eastern part of Central Europe, which was taken over by the Slavs during the migration of nations, used to be inhabited by Celtic and Germanic tribes in antiquity. Certain areas of the Czech lands were the original homeland of the Celts, and the mighty tribe of the Celtic Boii gave their name to the country, where it is used to this day (Boiohemum, Bohemia). They lived here for several centuries, and their political and cultural centre lay on Závist hill, south of Prague. At the turn of the era the Germanic Marcomanni and Quadi drove the Boii out of the Czech lands, and later these tribes moved further east, to Slovakia, where the Roman Emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius fought against them in the second century A.D. They were followed by other Germanic tribes from the Elbe region, among them chiefly the Lombards, some of whom stayed long enough, together with certain other Germanic inhabitants, to witness the arrival of the Slavs.

Not a single contemporary historian left any record of when and how the Slav tribes moved into Central Europe. There is only the indirect evidence provided by Procopius and Jordanes, mentioned in the previous chapter. It depicts the Slavs in the process of migration in the sixth century, but provides few concrete facts which might give a clearer idea oi this event, which had such an important part in shaping the later history of that part of Central Europe. Some of the Slav tribes had their own legends; they were handed on by word of mouth from generation to generation before they were written down and treated as a work of literature by a medieval chronicler. This is what happened to the collection of Czech legends, which were written down and re-composed in the early twelfth century by Prague chronicler Cosmas. He described the beginning of Slav settlement in the Czech lands in the following manner:

". .. At that time the surface of this land was covered with broad expanses of desolate forests, without a single inhabitant... When men entered these deserted places, whoever they may have been — unknown and accompanied by a few other people — seeking suitable places for human dwellings, their bright eyes saw mountains and dales, plains and hill-slopes, and I believe somewhere around Mount Rip, between two rivers, the Ohře and the Vltava, they first established settlements, built

28-29

![]()

dwellings and joyfully placed upon the ground their gods whom they had carried on their shoulders."

The restrained words in which Cosmas formulated his story show that he was trying to establish a historical hypothesis in its medieval form. He used certain local traditions that related the origin of the Czechs, and it was clearly linked to a definite place. With its striking outline Mount Rip, in the very centre of the country, offered itself to the idea of "Old Father Czech", the leader of the tribe standing on its summit after long years

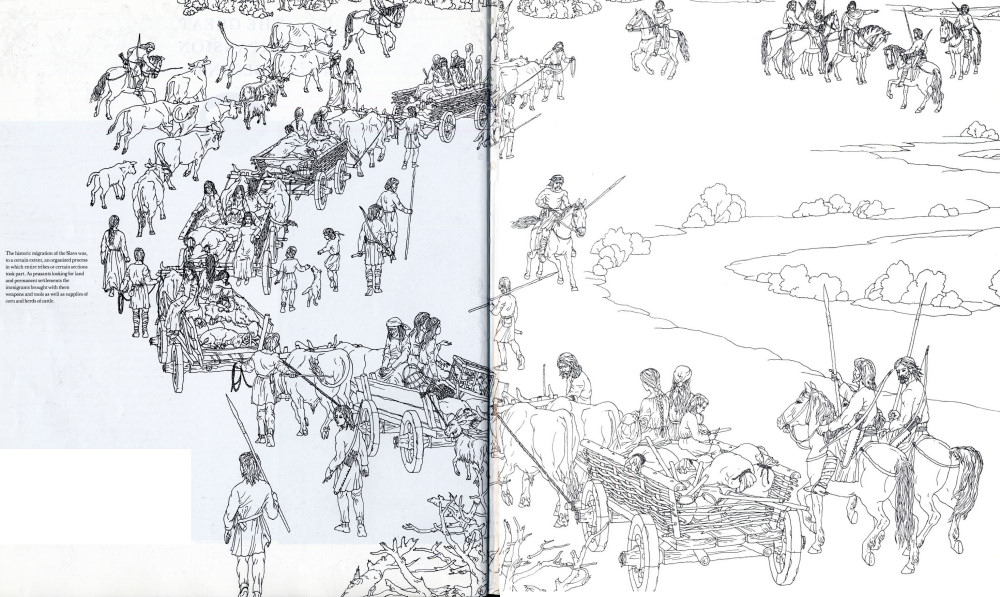

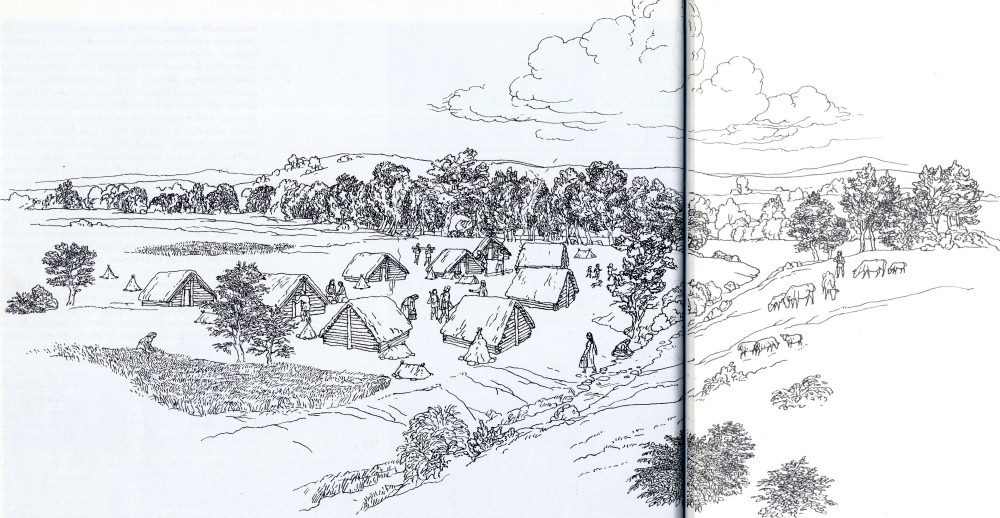

The historic migration of the Slavs was, to a certain extent, an organized process in which entire tribes or certain sections took part. As peasants looking for land and permanent settlements the immigrants brought with them weapons and tools as well as supplies of corn and herds of cattle.

30-31

![]()

of wandering and choosing the surrounding land as home for his people just like Moses long before, who from Mount Nebo set eyes on the Israelites'. Promised Land. This distant past was no more than a misty reminiscence, added to and embroidered with great fantasy. Only one thing is real in the chronicler's report — the fact that the ancestors had come to the country. But Cosmas did not know about their Celtic or Germanic precursors — they were only discovered by the sixteenth-century scholars who studied ancient writers — and he was, therefore, of the opinion that Old Father Czech settled in a deserted, forest-clad land that had not been inhabited since the time of the biblical flood. He did not even dare to guess where the multitude of Czechs had come from. He left that to later chroniclers, such as Dalimil in the fourteenth century, who, strangely enough, spoke of Croatia as the original homeland of the Czechs. If that is a reference to an older folk lore, it cannot mean modern Croatia, as Dalimil himself must have assumed, but Great or White Croatia. In the distant past this stretched to the north of the Carpathians, today's southern Poland and western Ukraine, from where the mighty Slav tribe of the Croats spread, some to the south, the Balkans, others to the west as far as eastern Bohemia. The Serbs, who were related to them, split up in the same manner as the Croats and told similar stories about their original homeland, as we can discover from reports by the ninth-century Bavarian Geographer.

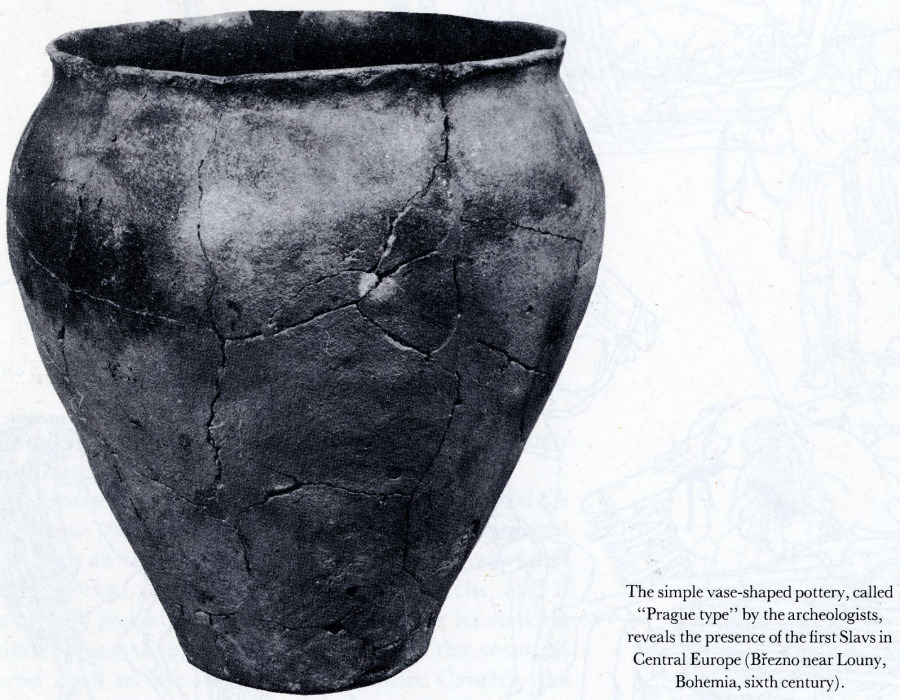

The simple vase-shaped pottery, called "Prague type" by the archeologists, reveals the presence of the first Slavs in Central Europe (Březno near Louny, Bohemia, sixth century).

It is thus possible to cull some truth from legends. But they cannot be taken as providing present-day historians with reliable facts. Their efforts largely failed in view of the complete lack of confirmed sources. Reports, or rather fragments of reports with references here and there, which have so far been found and analysed, often produce more questions than answers.

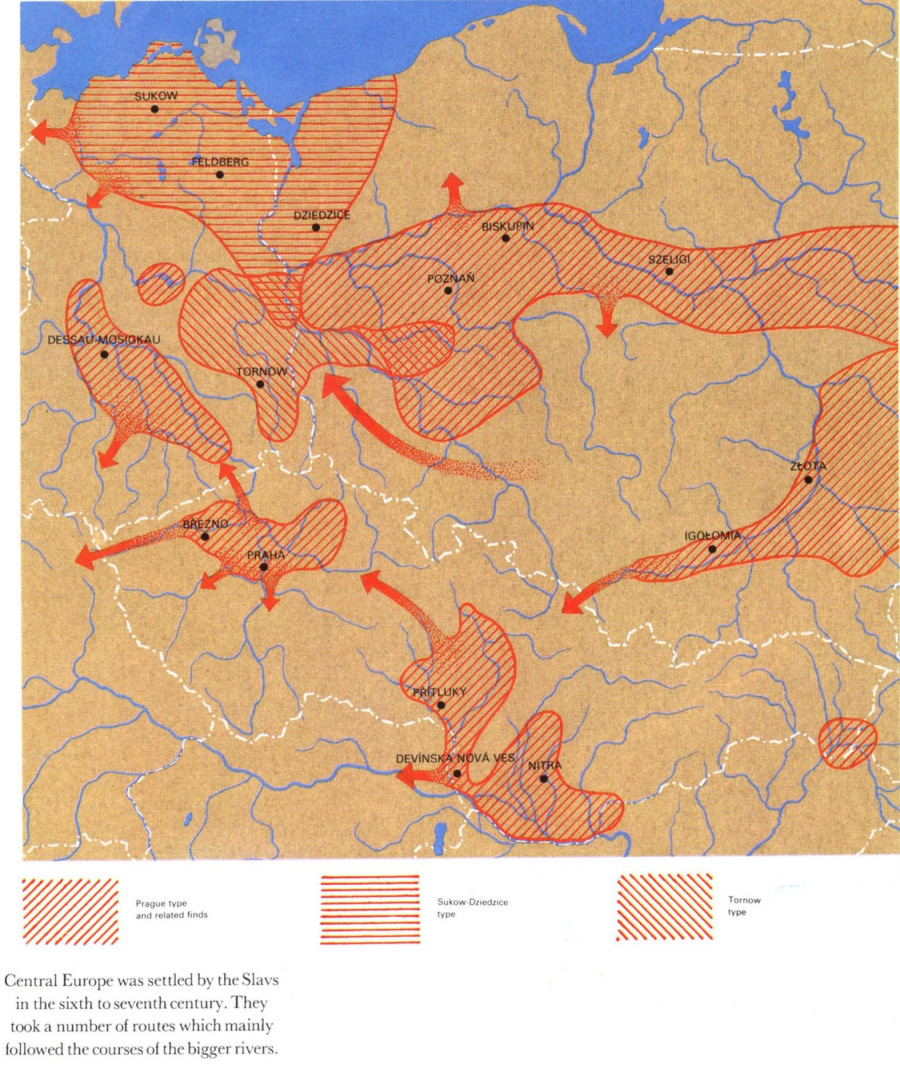

This almost hopeless situation changed greatly when archeologists joined in the discussions of the historians; their discovery of pottery provides concrete proof of the expansion of the Slavs. According to finds in the Prague region the pottery is known, since 1940, as the Prague type. Soon similar finds were made in Moravia, Slovakia, East Germany, and mainly in southern Poland and the western Ukraine (Korchak type), that is, on a territory that belonged to the eastern regions of Slav migration. The connection between these finds and the movements of the Slavs at the time of the migration of nations suddenly became clear.

Archeologists are not only concerned with pottery but with discovering the circumstances in which it is found: the sum total of facts and relationships investigated in the research then provides a better insight into the life style, work, dwellings and the level of culture. In the case of the Prague type it was a matter of finds of graves and of dwellings. In the graves the pottery most often served as urns, that is, to hold the burnt bones and ashes of the dead. Certain objects had been placed in these urns: clasps, knives, blades, combs, glass beads and the like. The urns containing these remains were buried in shallow graves or a barrow was raised above them. Where the dead had not been cremated, which was rare in the very early period, they placed an urn in the grave as a gift. In the dwellings, the remains of pottery vessels, together with other objects, lay scattered on the floor or in infills as waste, or they were left behind when the dwelling was suddenly abandoned or destroyed. The comparison with finds in other sites, with objects of the same, preceding and following periods, and those in neighbouring and more remote regions and then mapping all these finds enables the archeologists to do what the historians could never read in their records: to get an idea of the overall advance of Slav settlement.

Valuable data on the development of pottery of the Prague type were derived, for example, in investigations of the cremation cemeteries at Velatice near Brno, where on the basis of horizontal stratigraphy it became possible to prove a conclusive link between the Prague type and the other well-known Slav pottery. An important find was also made at Přítluky in southern Moravia, where more than four hundred graves were uncovered together with a settlement that occupied an area of roughly one square kilometre (0.4 square mile). The concentration of inhabitants, which this find proves, is quite exceptional since the majority of settlements and burial grounds of the Prague type were on a relatively small scale.

On the basis of the few accompanying objects the

32

![]()

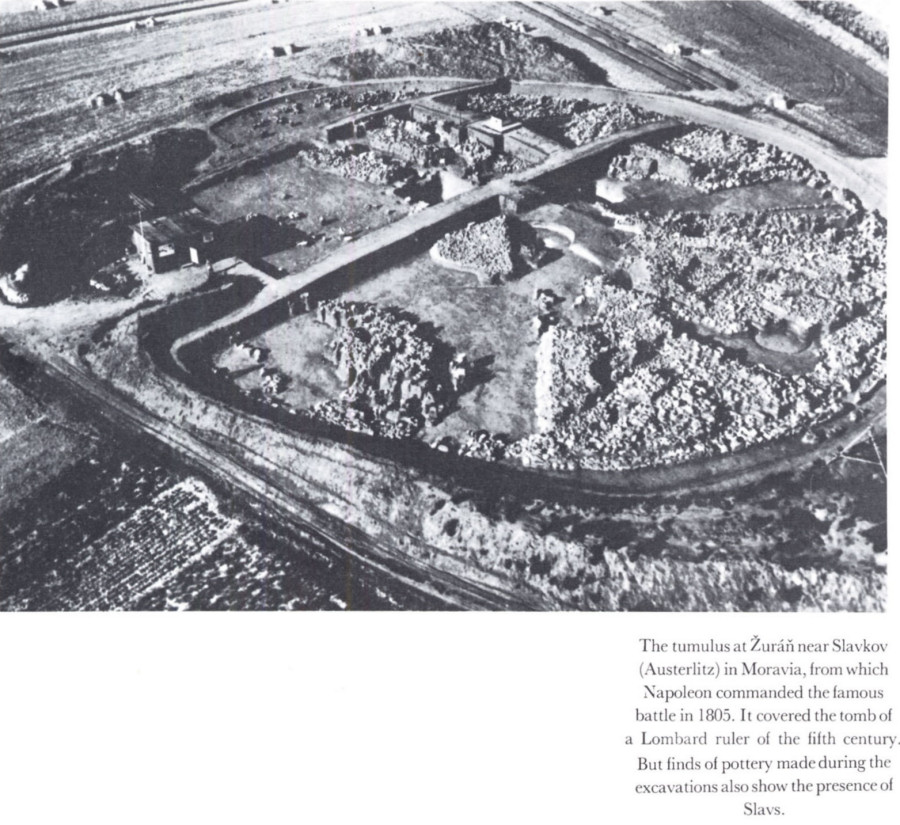

Moravian finds of the Prague type can be dated roughly to the period from the turn of the fifth to the sixth century into the seventh century. For a historian this fact is remarkable since, until the middle of the sixth century, he has to reckon with Germanic settlements in the southern parts of Moravia where the early Slav finds are concentrated. In the fifth century the Rugi lived here, who had spread this far from the Danube valley in Austria. After their utter defeat by the Goths in 488 the area of the Rugi was taken over by the militant Lombards, who were traced by the archeologists from finds of skeleton burials with tombs of warriors. An exceptional discovery of this type was the tumulus at Žuráň near Brno. In 1805 Napoleon set up his headquarters right on top of it and directed the famous battle of Austerlitz from there. He had no idea that below him were the tombs of other similar conquerors, who had penetrated into Moravia thirteen centuries earlier. It may well be that this is the burial place of a Lombard king and his wife; the rich dowry for the after-life had unfortunately been stolen, except for some small pieces. But what is interesting is that in one of the tombs, sherds have been found of a vessel that is very close to the Prague type. There have been several such cases, and this proves a certain form of Slavo-Germanic co-existence.

The tumulus at Žuráň near Slavkov (Austerlitz) in Moravia, from which Napoleon commanded the famous battle in 1805. It covered the tomb of a Lombard ruler of the fifth century. But finds of pottery made during the excavations also show the presence of Slavs.

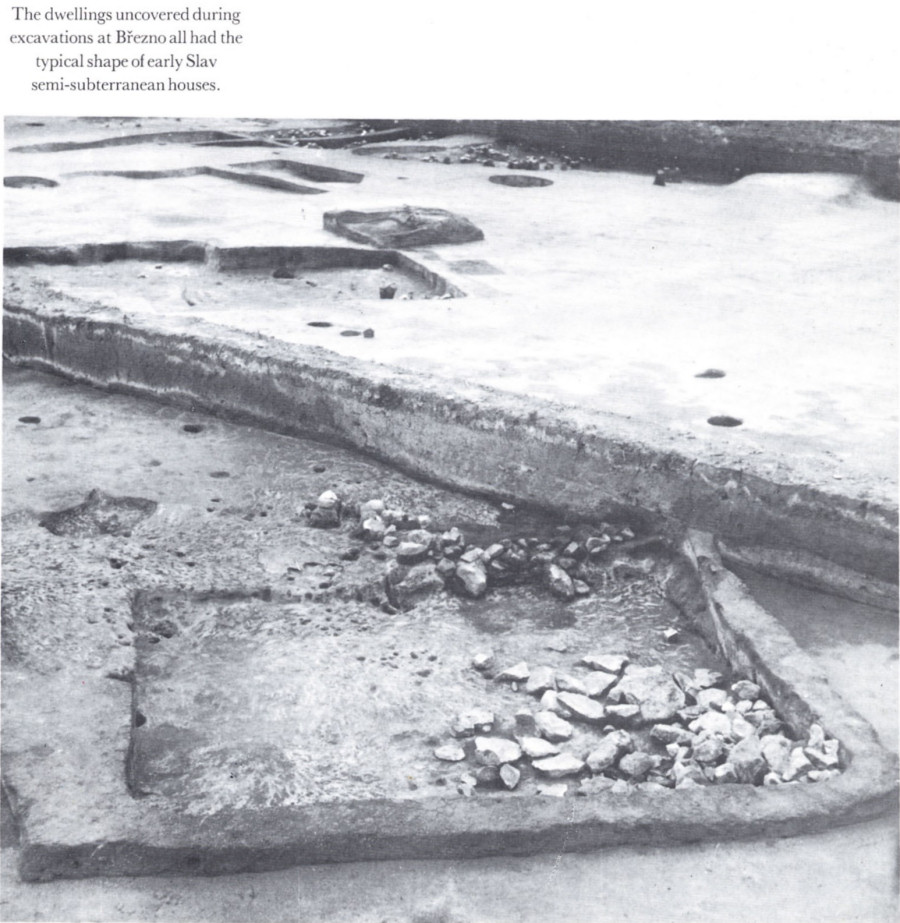

The dwellings uncovered during excavations at Březno all had the typical shape of early Slav semi-subterranean houses.

These relationships can tell us something about the arrival of the Slavs, about a period for which written records remain silent. A number of settlements and burial sites have been discovered in Slovakia. At the settlement at Výčapy-Opatovce vessels of the Prague type were found side by side with Hun pottery, which cannot be later than from the second half of the fifth century when the nomad empire of the Huns came to an end in the Carpathian Basin after their defeat on the Catalaunian Plains. The finds are concentrated in the fertile regions of south-western Slovakia, along the rivers Morava, Váh, Dudváh, Nitra, Hron and Ipel'. A little before that time Slav tribes moved into eastern Slovakia, where their pottery is found together with sherds of the barbarian Roman culture from the turn of the fourth to the fifth century (known as the PREŠOV TYPE). In this manner it is possible to document the shift of Slav settlement in Central Europe from east to west.

The living conditions in the most westerly regions — that is, the Czech lands and along the middle course of the Elbe (the southern part of today's German Democratic Republic) — are revealed, on two particularly important sites among many others, where archeologists have been concentrating their attention: Březno near Louny and Dessau-Mosigkau in Saxony.

At Březno a settlement from the end of the fifth and the first half of the sixth century has been uncovered. It belonged to the remnants of the Germanic inhabitants who had otherwise left the Czech lands as they moved further to the south-east and south-west. The people lived in huts of a rectangular ground plan, partly dug into the ground, with a wooden construction usually supported by six poles, in which case three of them are placed on each of the narrower sides. Their settlement gradually moved from its original place in an easterly direction to the right bank of a stream that flows into the Ohře. During the first half of the sixth century new

33

![]()

immigrants appeared, who, strangely enough, did not behave in a hostile manner, but settled by the side of the original inhabitants. There clearly was no reason for conflict between the peaceful farming people and cattle breeders, pursuits both people followed, in the sparsely inhabited regions of Bohemia where the soil lay fallow and there was suitable ground both for corn growing and pasture. The immigrants were the first Slavs, who did not greatly differ from their Germanic neighbours in their manner of living and level of culture and for that reason merged with them into one unit in the relatively short period of about two generations. They lived likewise in simple dwellings, partly dug into the ground, but of square ground plan with a trodden earth floor and usually a stone oven in the south-western corner, which did not exist in the Germanic huts. Vessels of the Prague type with or without decorations predominated in their households. The co-existence of the two peoples can be traced in mixed types of pottery and dwellings.

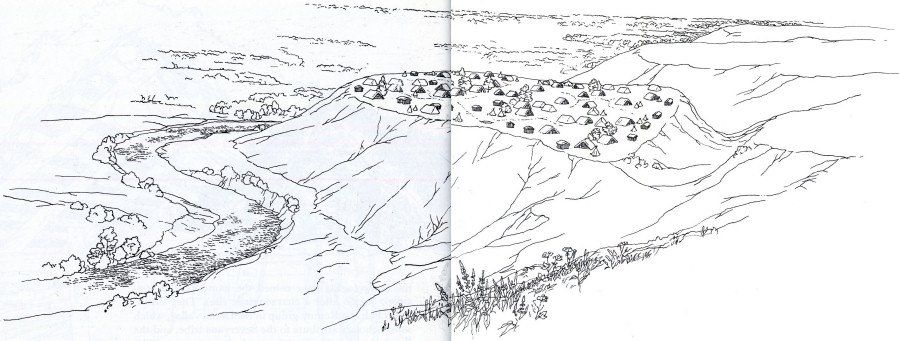

One of the main centres of early Slav settlement in Bohemia was the river Ohře. Archeologists have been investigating a settlement on the banks of the river near Březno, founded by Slav immigrants on the site of an earlier Germanic settlement some time in the second quarter of the sixth century.

The Slav settlement was likewise moved after a time, probably as a consequence of a cyclical, partially migratory agriculture in which certain areas of the tilled land were left to lie fallow after a certain period and the dwellings were moved closer to the fields then under cultivation. Seven to ten houses were grouped in a circle around an open central space (each settlement had roughly forty to sixty inhabitants), and all around were pits for supplies — deep pits of a circular shape that were used for underground grain storage. The corn found here, mainly wheat but also barley, rye, oats, millet and even peas, lentils and hemp, is proof of a more advanced stage of agricultural technique than the original inhabitants possessed.

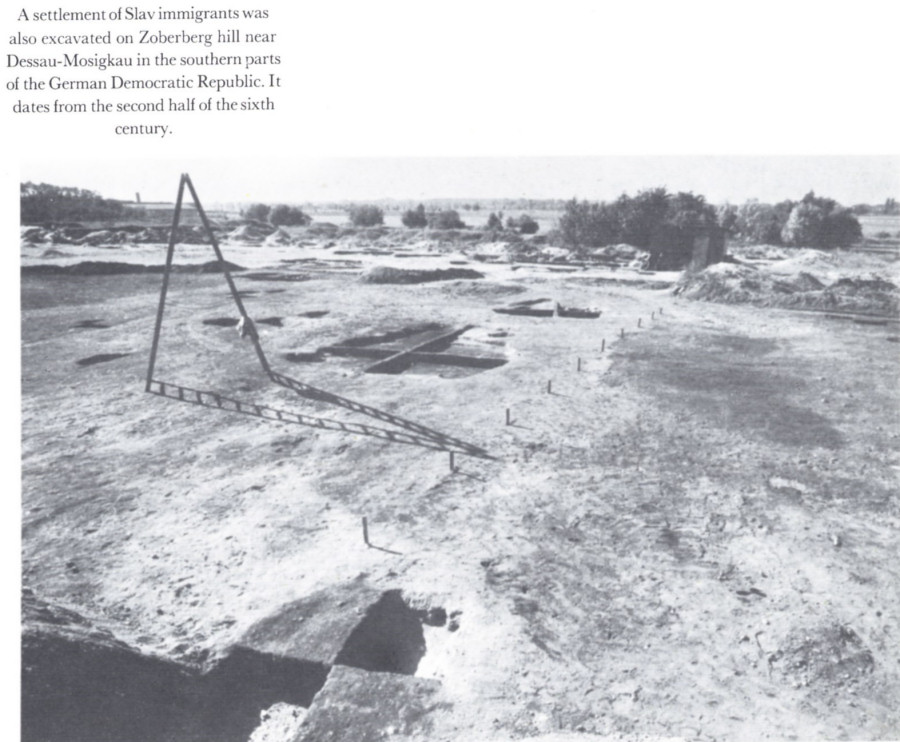

A similar village with an open central area was excavated in the years 1962—65 on Zoberberg hill near Dessau-Mosigkau in the south of the German Democratic Republic. Here, too, contacts with the original inhabitants were observed in finds of pottery and the construction of dwellings, and here, too, the settlement was gradually moved, in fact in five stages. Many other similarities can be found, with but one difference: everything took place at a slightly later date, the second half of the sixth century.

In this manner the archeological finds of the Prague type document the advance of Slav tribes from the east to the west: first they are to be found in eastern Slovakia (perhaps as early as in the first half of the fifth century); then in south-western Slovakia (second half of the fifth century); in southern Moravia (at the turn of the fifth to sixth century); later in Bohemia (first half of the sixth century) and finally between the Elbe and the Saale (second half of that century). What the contemporaries of this historic process — Procopius and Jordanes — did not reveal was shown by mute evidence in the hands of the archeologists.

Slav settlement in the north-western parts of Central Europe presents a slightly different picture; this is the

34-35

![]()

region between the middle and lower courses of the rivers Elbe, Oder and Vistula. This settlement is not recorded in any chronicle and is not even mentioned in legend, and so we have to rely only on the proofs provided by archeological finds, which have not yet given answers to all the questions.

The settlement at Březno comprised a group of seven to

ten semi-subterranean dwellings, forming a circle round an open space. Corn and

other foodstuffs were kept in covered pits which served as stores.

Here, too, Germanic settlements from the time of the late Roman period came to an end basically at the turn of the fourth to the fifth century. But in places enclaves of the pre-Slav inhabitants survived until the second half of the fifth or even the beginning of the sixth century: for example, in central Poland where a late Przeworsk-culture settlement was discovered at Piwonice; the same is true of Polish Pomerania. The territory further to the west was likewise depopulated in the fifth century — the tribes of the Angles and Saxons moved to Britain at that time, while the Lombards migrated to the south — but traces of Germanic settlement remained in western Pomerania in Mecklenburg and Holstein until the first quarter of the sixth century, in exceptional cases even until the beginning of the seventh century; in Brandenburg and the middle course of the Elbe the Germanic, settlement disappeared around the middle of the sixth century.

The migration of the local Germanic tribes made it possible for the Slavs to penetrate by stages, in larger numbers than elsewhere, and here they will have met the last of the Germans to leave. This' conditioned the unique features of Slavonic culture, which differs in some respects from the Prague type of the more southerly regions. In their settlements the archeologists have, for instance, found types of houses other than the semi-subterranean dwellings typical of the Prague-Korchak type: the people tended to live in log cabins above

36

![]()

ground, the interior was not dug into the ground, and only irregular trenches served for storage. In the first phase of colonization the local Slavs produced simple, hand-made and undecorated pottery, but of slightly differing shapes (known as the SUKOW-DZIEDZICE TYPE) than those customary on the territory of Czechoslovakia or southern Poland. Very soon more advanced pottery appeared, turned on a wheel, for example, the Feldberg type, or the bi-conical tornow type vessels found mainly in Lower Lusatia, Silesia and in the Oder valley. The original centre of these two types of ornamented pottery — dated into the seventh, in places even the end of the sixth century — is being sought in the region along the upper course of the Oder and in Silesia at the time of the migration of nations, where similar elements appeared within the late Przeworsk setting. It is from there that the main stream of Slavic colonization must have come to the regions between the lower Elbe, Oder and the Baltic Sea, the shores of which the Slav tribes reached in the course of the sixth century if we can believe the records of the Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta. The Slav settlement of eastern Germany, confirmed today by the large number of place names of Slav origin, took place from the middle of the sixth to the middle of the seventh century and the people remained here, despite centuries of dramatic struggles, until the Middle Ages, and in certain areas (Lusatia) they have remained to the present day.

A settlement of Slav immigrants was also excavated on Zoberberg hill near Dessau-Mosigkau in the southern parts of the German Democratic Republic. It dates from the second half of the sixth century.

The special cultural status of this north-western Slav group in Central Europe shows a corresponding linguistic development, in the framework of which the Lekhitic group of the Slavonic languages later came into being; including Polish, Lusatian—Sorbian, the now vanished Polabian Slavonic and Kashubian. The early Middle Ages saw the first signs of differentiation among the Slavs, who after settling over a vast territory in Europe began to lose their unified language and culture and gradually split up into more or less big groups; and once independent states came into being, this led to the development of national tongues.

The Slav expansion to the west continued in the seventh and eighth centuries when it nearly reached to the mouth of the Elbe, as proved by recent finds of Slav settlements in Hamburg. They crossed the middle courses of the Elbe and Saale and penetrated to Thuringia and northern Bavaria. This remarkable influx of settlers might have gone even further if, at the end of the eighth century, there had not appeared a mighty barrier in the form of the Empire of Charlemagne who began to push in the opposite direction.

37

![]()

2. THE ADVANCE INTO THE BALKANS

There exist far better historical sources to document Slav settlement in South-Eastern Europe, for here they were advancing into the civilized world of the time — the cultural sphere of Byzantium. The Byzantine chroniclers recorded the exact year when the Slavs crossed the Danube and began raids into Macedonia, Thessaly and Epirus — that is, the territory where southern Yugoslavia, Albania and northern Greece lie today: it was in the year 517. These raids occurred on numerous occasions during the reign of Emperor Justin (518-527). For a time Justinian the Great (527-565), the outstanding ruler of Byzantium, managed to put a stop to the Slav influx. He permitted some Slav tribes, among them the Antes, to settle on Byzantine territory, and they became allies of the Empire — called foederati — as had been the age-old practice in ancient Rome. Nonetheless, the inroads of Slavs continued: in 536 they reached the coast of the Adriatic Sea, in 548 Dyrrhachium, and further raids continued throughout the fifties of the sixth century.

The beginnings of Slav settlement in Mecklenburg are represented by the hill-fort Alte Burg near Sukow, which was probably built already in the seventh century.

Events took a sharper turn when a new factor appeared on the scene: the Avars. These militant nomads of Asian origin, coming from the Eastern European steppes, were attracted by the Carpathian Basin in particular, where before them their relatives, the Huns, had settled and where two hostile Germanic peoples were living in the sixth century — the Lombards and the Gepids. The Avars helped the Lombards destroy the Gepids, and then the Avars occupied their territory, after the Lombards had decided to leave their uncomfortable new neighbours in 568 and move to northern Italy, where they founded a new empire on the ruins of the Roman Empire. The Avars then made the territory of what is Hungary today their centre, and from there they threatened Western and Southern Europe. They were aided in this by several Slav tribes either as allies or vassals. The tribes that remained on the side of Byzantium — e.g. the Antes along the lower Danube were destroyed by the Avars in a special campaign in the year 602.

In their raids against the Byzantines the Avars without intending to do so — contributed to further

38

![]()

Slav colonization of the Balkans. There was one great difference between the behaviour of the Avars and that of their Slavic allies in these raids: while the nomads, as was their custom, only looted, laid everything waste and then moved on, the Slav peasants settled for good on the territory they had attacked. In this way they gradually peopled all the former Roman provinces: Dacia, Moesia, Dardania, Macedonia, Dalmatia and Epirus. In 578 the Slavs even reached the Peloponnese, and from 581 on they began to settle on Greek soil to the horror of the Byzantines who found refuge only in the larger towns. We can well imagine the feelings of the inhabitants of the famous cities of antiquity, such as Athens and Thebes, when they observed with what disregard the barbarian intruders made their homes in their vicinity. It was only by a miracle, attributed to St Demetrius, that in 597 Thessalonica escaped destruction after a siege by the Slavs and Avars; while the Avars returned to their camps in the Hungarian Plain, the Slavs remained in the Thessalonican countryside as permanent settlers. Not quite three hundred years later this enabled the men of Thessalonica, Constantine and Methodius, to learn the Slavonic tongue and give it both an alphabet and a literary form.

Central Europe was settled by the Slavs in the sixth to seventh century. They took a number of routes which mainly followed the courses of the bigger rivers.

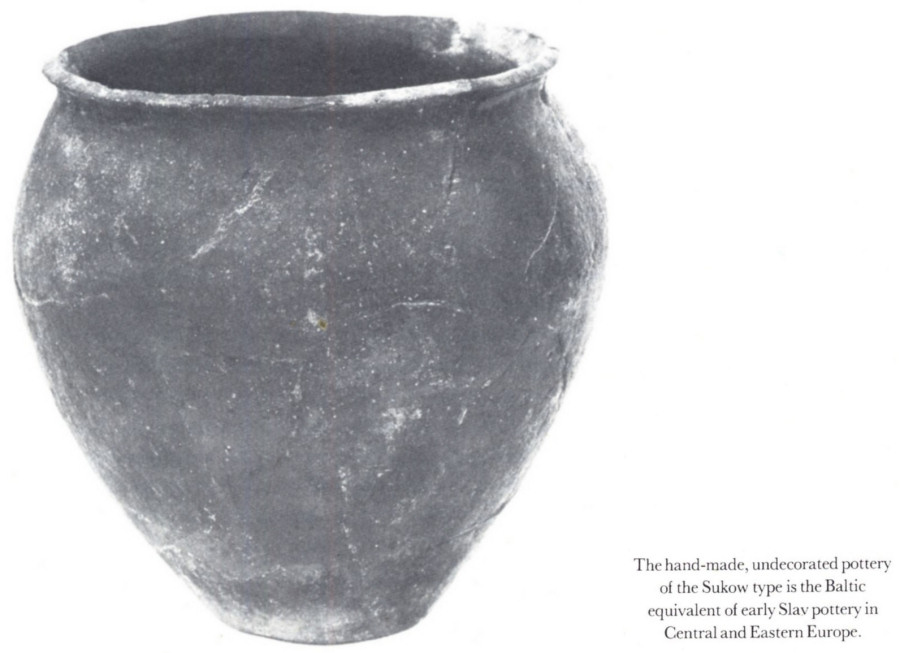

The hand-made, undecorated pottery of the Sukow type is the Baltic equivalent of early Slav pottery in Central and Eastern Europe

The Byzantine Empire was in a particularly difficult situation since the eastern border was threatened by the Persians during the reign of Emperor Maurice (582—602). It was only after the dangerous enemy had been defeated that the Byzantines could concentrate their forces on the Balkans again and they beat the Slavs and Avars on several occasions. The Danube once again came to form the border between different centres of power.

At the beginning of the seventh century another wave of Slav settlers came to the Balkans; they penetrated to the west as far as Venice and valleys in the Alps, south across the Peloponnese to the Aegean islands and to Crete and even reached the coast of Asia Minor. Today we have difficulty in imagining the vitality of those invaders, who had been completely unknown until they managed to flood such vast areas in large numbers within a few decades and push a wedge between the Roman west and the Greek east. The local inhabitants heaved sighs of relief only at the beginning of the ninth century, when Nicephorus I managed to defeat the Slavs in the decisive battle near Patras on the Peloponnese and

39

![]()

thus basically put an end to their occupation of Greece. The rest of the Slavs, however, stayed for a relatively long time; in the Taygetus mountains on the Peloponnese tribes of the Erzerites and Milings were still recorded in the fourteenth century, when the Turks arrived there. The territory of Bulgaria today and of Yugoslavia has remained Slav to the present day.

Now let us take a closer look at what archeology can tell us about the process of Slav settlement on the Balkan peninsula. The key area is the territory of present-day Romania, ancient Dacia, for the main stream of Slav colonists moved along the curve of the Carpathians and along the Danube.

The main flow of Slavs who colonized the Balkan peninsula moved from the Ukraine along the Carpathians and across the Danube. They went as far as the Adriatic Sea, the Peloponnese, the Aegean islands and the coast of Asia Minor.

At the time of the Roman Empire this was where the Dacians lived, against whom the Romans fought numerous battles, before they incorporated them in their empire at the beginning of the second century A.D. The province of Dacia took up only the western part of present-day Romania, and under Emperor Aurelian in the year 271 the impact of barbarian tribes forced the Romans to retreat across the Danube. The country was flooded by Iranian Sarmatians, Germanic Gepids and Goths, Turco-Tatar Huns and Avars, and mainly by masses of Slavs; they came to form the core of the local inhabitants from the sixth to the tenth century when, for so far unexplained circumstances, the remnants of the Romanized inhabitants — today's Romanians — began to gain the upper hand both culturally and linguistically. We have mentioned a report by Jordanes from the middle of the sixth century that Slav settlements ranged as far as the town of Novietunum which can be identified as Noviodunum, lying close to the widening delta of the Danube. Even today there is a settlement called Isaccea, where Romanian archeologists have found traces of an old Slav settlement on the ruins of an ancient town.

Until recently little was known about the scope and character of Slav settlement in Romania. Investigations by Romanian archeologists in the last few decades have provided more concrete ideas, even though the explanation of some new discoveries is still hotly discussed.

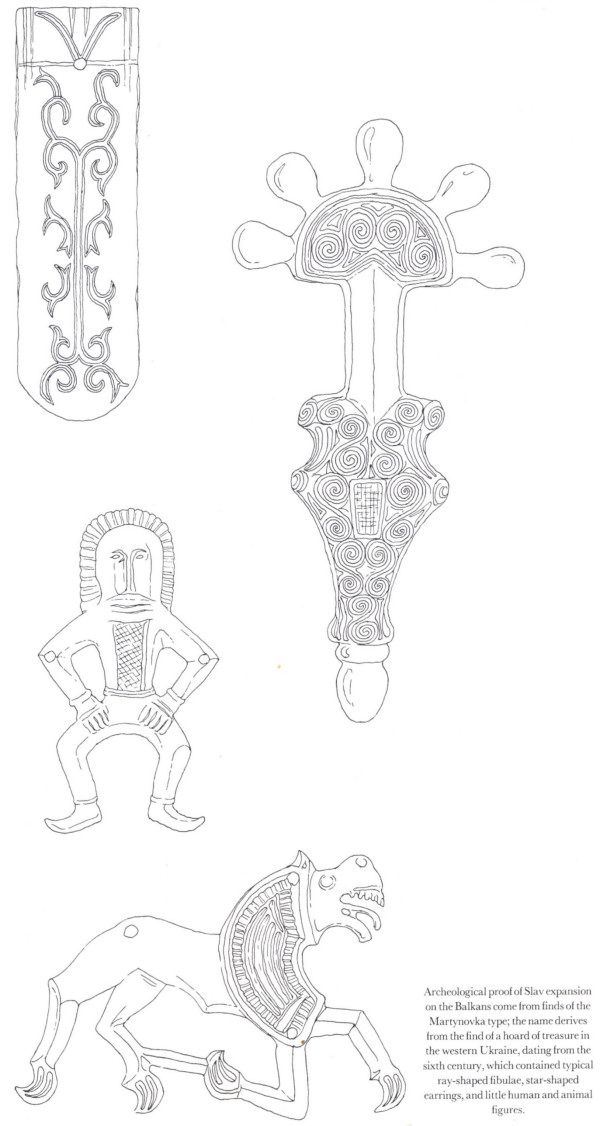

The oldest Slav finds were made in Moldavia, the northern part of Romania between the rivers Prut and Sereth. This territory lies in close vicinity to the oldest Slav group in the Ukraine, which we met in the Korchak and Pen'kovka types. It is understandable that the bearers of this culture penetrated to Romanian Moldavia already in the second half of the sixth century and left behind settlements with semi-subterranean dwellings and cremation burials of the same kind as Soviet archeologists found in the areas of the Dnieper, Dniester, Pripyať and Bug. The finds are dated by the ornaments of the MARTYNOVKA TYPE (called after a treasure from the Kiev region) which are a proof of Slav expansion to the Balkans and even by Byzantine coins, with those of the Justinian period dominating, from the second half of the sixth and the early seventh century. The inhabitants of these first settlements often chose boggy terrain surrounded by dense forests, which provided refuge in case of danger. The bearers of the Korchak and Pen'kovka types penetrated, towards the end of the sixth century, not only southwards to the Danube lowlands but across passes in the Carpathians even into Transylvania. These finds include certain elements from the northern areas of the Dnieper, Desna and Berezina, i.e. elements of the Kolochin-Tushemlya type, which clearly belonged to Slavonicized Balts; the migration of the Slavs must have involved tribes from the entire eastern Slavic territory.

Slavic finds from the seventh to ninth centuries are identical in character with contemporary finds to the east, known as the LUKA RAYKOVETSKAYA TYPE, which developed from the early Slavic pottery of the Korchak type. They are proof of permanent relationships with eastern Slav tribes, whose settlements at that time spread over the entire territory of what is now Romania.

The Western Slavs partly shared in the Slav settlement of Romania, when they penetrated from Central Europe to Transylvania. This can be proved by the burial ground with tumuli at Nuşfalău near Oradea with

40

![]()

typical pottery and objects of Slavo-Avar type from the eighth and early ninth centuries.

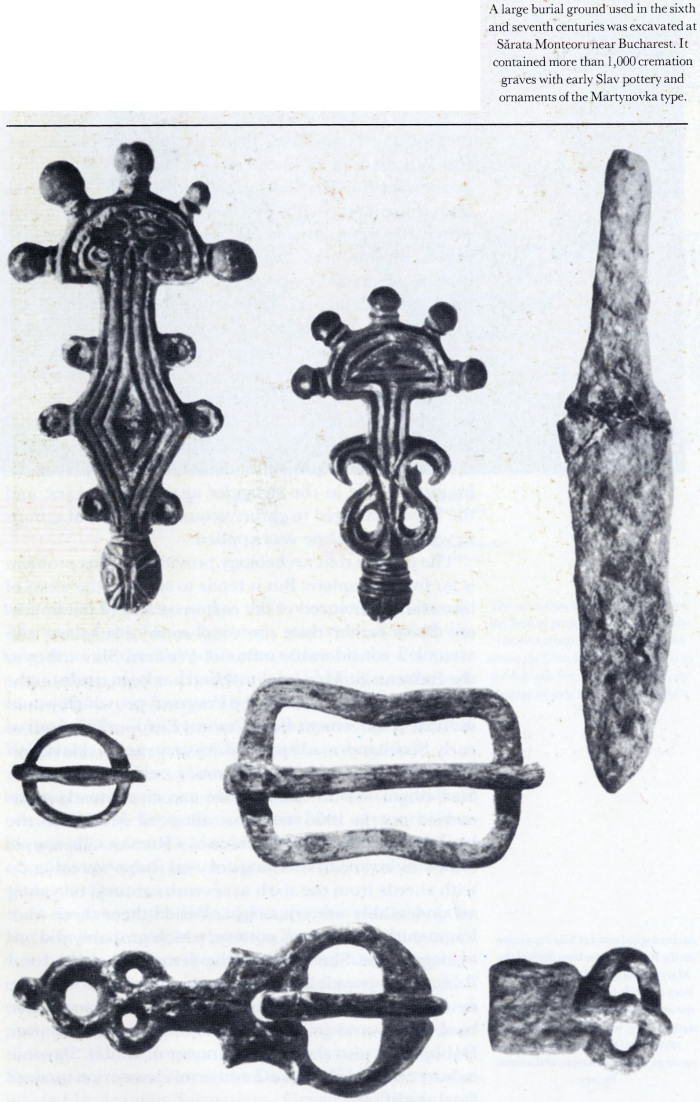

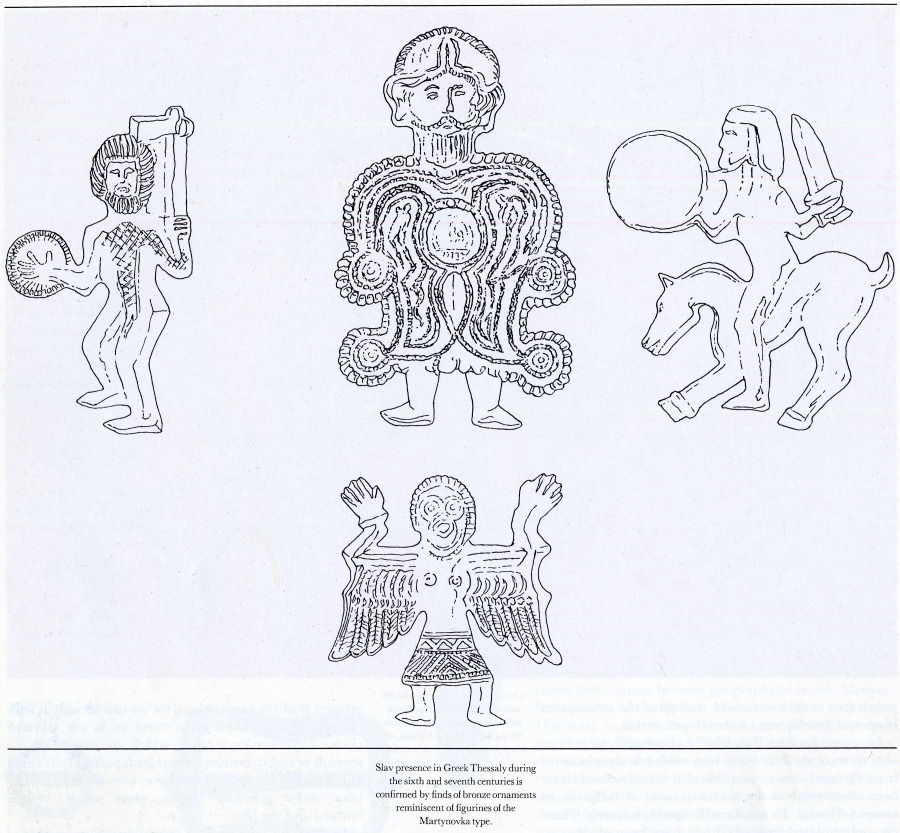

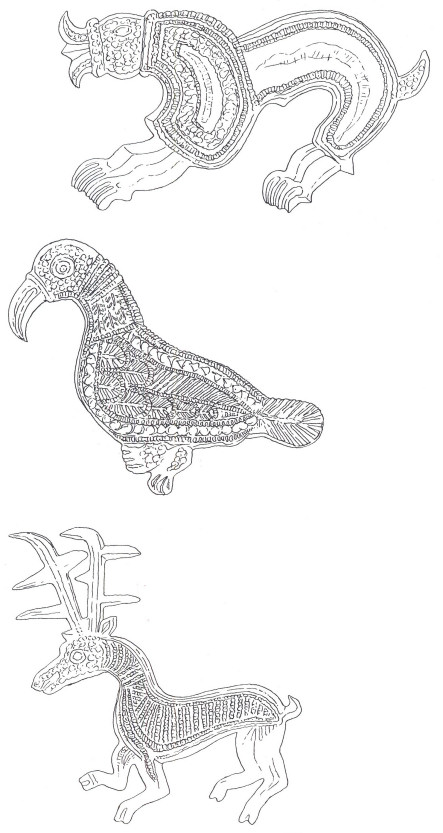

Archeological proof of Slav expansion on the Balkans come from finds of the Martynovka type; the name derives from the find of a hoard of treasure in the western Ukraine, dating from the sixth century, which contained typical ray-shaped fibulae, star-shaped earrings, and little human and animal figures.

The Romanian archeologists have tried to trace the process of how the Romanic ethnic group came into existence on the basis of a certain renaissance of provincial shapes of pottery, burial rites and some peculiarities of the ninth-tenth century dwellings, in which they see the first signs of the Romanization of the population. The origins of the Romanians have not yet been satisfactorily explained, but what is certain is that the Slavs must have played a major role in their genesis. This is shown not only by the large number of Slavonic words in the Romanian language and Slavonic place-names all over Romania, but also by archeological clues.

The beginning of Slav settlement in Romania is related to the penetration by the Slavs to the territory of present-day Yugoslavia. Historians and philologists are still engaged in a lively discussion on the share of Western or Eastern Slavs in this expansion, but it seems that those arguments are well founded according to which the main stream of migration arrived from the east across ancient Dacia in the middle of the sixth century. The starting point of a lesser wave of migration were the settlements of Croats north of the Carpathians in the upper Vistula valley, from where smaller tribal groups moved south. This movement was recorded as an old legend by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the middle of the tenth century. The fact that the Southern Slav tribes bear the name of that numerically relatively small Western Slav people shows that the Croats and with them the Serbs played an important role in the struggles against the Avars; and the Slavs managed to gather around them tribal groups to which their name was applied.

The picture that archeology provides on this problem is far from complete. But it tends to support the views of historians convinced of the eastern origin of the Southern Slavs rather than the conclusion of scholars who assume a considerable influx of Western Slav tribes to the Balkans. So far no definite find has been made on the territory of Yugoslavia of the Prague type, which would indicate a movement from Central Europe. The finds of early Slav hand-made pottery are very rare in this region and tend to resemble the Romanian, which is of Eastern Slav origin. As an example we can cite investigations carried out in 1966 near the village of Mušiči on the banks of the Drina. In the ruins of a Roman villa simple semi-subterranean dwellings of oval shape were dug up with sherds from the sixth to seventh century, revealing an undeniably eastern origin. Beside them there were fragments of a different pottery, which probably did not belong to the Slavs but to the remnants of the local Romanized population, who gradually merged with the new arrivals, the Slavs. Similar signs of symbiosis have been discovered in other places, e.g. at Žabljak near Doboj; they also show the character of a later Slavonic culture combined with a number of elements of ancient local tradition.

41

![]()

Strong relations to the southern Russian region are shown by finds of the Martynovka type, ornaments and jewels that are typical of local development in the sixth century on the territory of the western Ukraine. They include, first of all, ray-shaped clasps with masks, star-shaped ear-rings, metal figurines of fantastic animals or human figures, and even matrixes for making those metal ornaments. They are widespread in all places to which the Slavs penetrated in their expansion through the Balkans. In Yugoslavia they are concentrated in the Danube region.

A large burial ground used in the sixth and seventh centuries was excavated at Sǎrata Monteoru near Bucharest. It contained more than 1,000 cremation graves with early Slav pottery and ornaments of the Martynovka type.

A very important locality that documents Slavonic culture from the time when the Slavs occupied the Balkans is Caričin Grad near Leban in southern Serbia. Originally this was the site of a Byzantine town, probably Iustiniana Prima, which the Slavs conquered as they advanced, and in its ruins they founded their own settlement. They built the walls of their simple dwellings in the streets and ruins of buildings using brick and stone held together with daub. Most of their houses are single-storeyed, with an irregular square ground plan, trodden earth floors and an open fireplace. Similar examples of early Slav settlement in the ruins of ancient cities have also been found elsewhere, e.g. at Margum, a Roman town at the confluence of the Morava and Danube, at Crkvica in Bosnia-Herzegovina, at Gamzigrad, even in Belgrade itself, the site where once stood the ancient city of Singidunum.

Apart from this, the oldest records of Slavs in Yugoslavia are to be found in monuments of early Avar culture from the sixth to seventh century. Typical features include, apart from nomad weapons, ornaments of pressed metal, mainly of Byzantine origin and related to the Martynovka type. This culture bears signs of an ethnic conglomeration, including, apart from the Avars and Kutrigurs, the remnants of the Romanized population and also, to a large extent, the Slavs, who were the Avars' main allies in their struggle with the Byzantines.

On the territory of Bulgaria the Slavs entered a land with a thousand-year-old cultural tradition. From the Bronze Age this was the home of the Thracians, an Indo-European people close, on the one hand, to the Dacians and, on the other, to the Greeks with whom the Thracians had close contacts. These relations were strongest in the Hellenistic period, when during the reign of Philip II and Alexander the Great the whole of Thracia was under the rule of Macedonia. But influences spread also in the opposite direction: the cult of Orpheus and especially of Dionysus, so popular in the Greek world, is of Thracian origin. When the Romans came, two provinces were established after long and bloody battles under Emperor Tiberius; for long centuries their names became geographical terms: Moesia, to the north of the Balkan Mountains (then called the Haemus) as far as the Danube, and Thracia proper south of the Haemus, which like a backbone runs across the whole country from east to west. Thracia, with the river Hebrus (today Maritsa) as its axis, and Philippopolis (Plovdiv) its capital city, was richer and more densely populated than Moesia; as the latter lay open towards the north into the Danubian lowlands, it was often the target of barbarian raids from the north, who regarded the Roman provinces as full of tempting loot. A milestone in development was the year 395, when, after the split-up of the Roman Empire, the two provinces fell to the Eastern Roman Empire with Constantinople as capital city. But the Byzantines managed only with great effort to keep control over their realms against the constant pressure of the northern barbarians. When in 488 the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great left Moesia and moved to Italy, the land remained deserted. In the sixth century the Slavs

42

![]()

penetrated it with ease, and thus gave the subsequent historical development a decisive direction.

One of the best-known finds on the territory of northern Yugoslavia, indicating links between the Baltic Slavs and the western Ukraine, are silver jewels from a prince's tomb at Čadjavica (seventh century).

In recent decades Bulgarian archeologists have been able to trace the first Slavs who settled in their country from the sixth century on. Most of the sites have so far been discovered in the northern parts of Bulgaria, in ancient Moesia. In southern Bulgaria, formerly Thracia, only isolated finds of pottery have been made.

The oldest Slav settlements in this region also lay along the river, near lakes or in boggy lowlands. The dwellings were simple, as everywhere in the Slav world of those days: semi-subterranean or underground houses with a stone oven in one corner, the floor smoothed with clay. The pottery found in these dwellings is closer to Eastern Slav finds of the Korchak type in its general character than the Prague type of Central Europe. This provides an indication of the origin of the tribes that settled in Bulgaria. Even later, carefully fashioned pottery adorned with wavy or horizontal grooves is of the same origin, for we can identify it with finds in Romania (HLINCEA TYPE) or in the Ukraine (Luka Raykovetskaya type), which are dated into the seventh or eighth century. Apart from pottery only small objects were found in these huts: iron knives, awls of bone, stone grinding wheels, glass pearls, bronze buttons and the like.

In Bulgaria, too, we find the original Slav custom of cremating the dead. The ashes were placed in urns or simply in circular pits. The modest personal belongings of the dead were placed in the grave, e.g. knives, arrow heads, sickles, scythes, spindles, buttons, rings, bronze coins, ear rings, glass beads, etc. They represent the simple culture of the first Slav settlers on whom the proximity of the Byzantine civilization left its mark only after a certain lapse of time, after the stabilization of their settlements and the founding of their own state in a symbiosis with the Turco-Tatar Bulgarians at the end of the eighth century.

43

![]()

Slav presence in Greek Thessaly during the sixth and seventh centuries is confirmed by finds of bronze ornaments reminiscent of figurines of the Martynovka type.

44

![]()

3. SLAV COLONIZATION OF EASTERN EUROPE

The eastern Slav expansion is a chapter unto itself. It was not limited to a short span of time in the sixth and seventh centuries as in the case of the expansion of the Slavs to the west and south. It became an almost continuous process of infiltration into the sparsely settled regions of Eastern Europe and later Asia, lasting throughout the Middle Ages and the new era. At this point, we are interested mainly in the initial stage, the phase of the early Middle Ages.

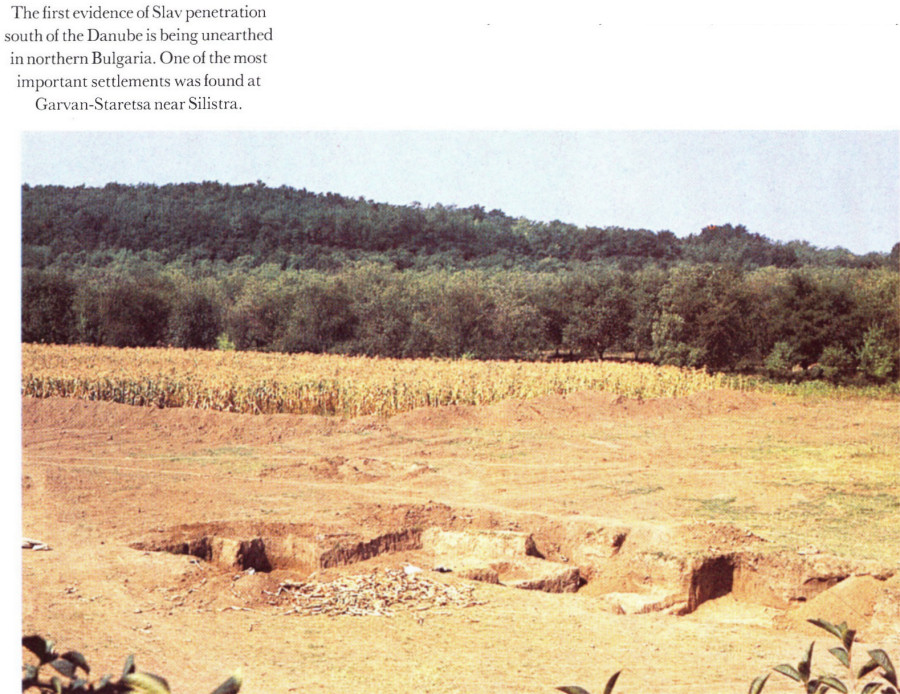

The first evidence of Slav penetration south of the Danube is being unearthed in northern Bulgaria. One of the most important settlements was found at Garvan-Staretsa near Silistra.

In contrast to the expansion into the Balkans there exist no written records to reveal anything about this early period. These regions were far too remote for Western European chroniclers of the seventh to ninth centuries, and they possessed but the vaguest ideas about them. Nothing more is to be found either in the works of Byzantine writers, who were geographically far closer. At the beginning they were interested only in the Slavs in the Balkans, with whom Byzantium had direct contacts. What was going on in the vast forest-steppe lands and wooded plains further to the north was none of their concern. The situation changed with the establishment of the Kievan state at the end of the ninth century, when Byzantium made close trade, cultural and military contacts with Eastern Europe. But even then the Byzantine chroniclers were more interested in other things than Slav colonization. There is only indirect evidence from the ninth and tenth centuries: the existence of certain Eastern Slav tribes was mentioned, e.g. in the writings of Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the tenth century, but they lacked detailed information about settlements. We can cull better knowledge from contemporary Arab sources, e.g. Ibn Khūrdādbih, Mas'ūdī, Ibn Fadhlan and others,

45

![]()

who mentioned the Slav penetration to the Don, Volga and the Sea of Azov in the ninth and tenth centuries.

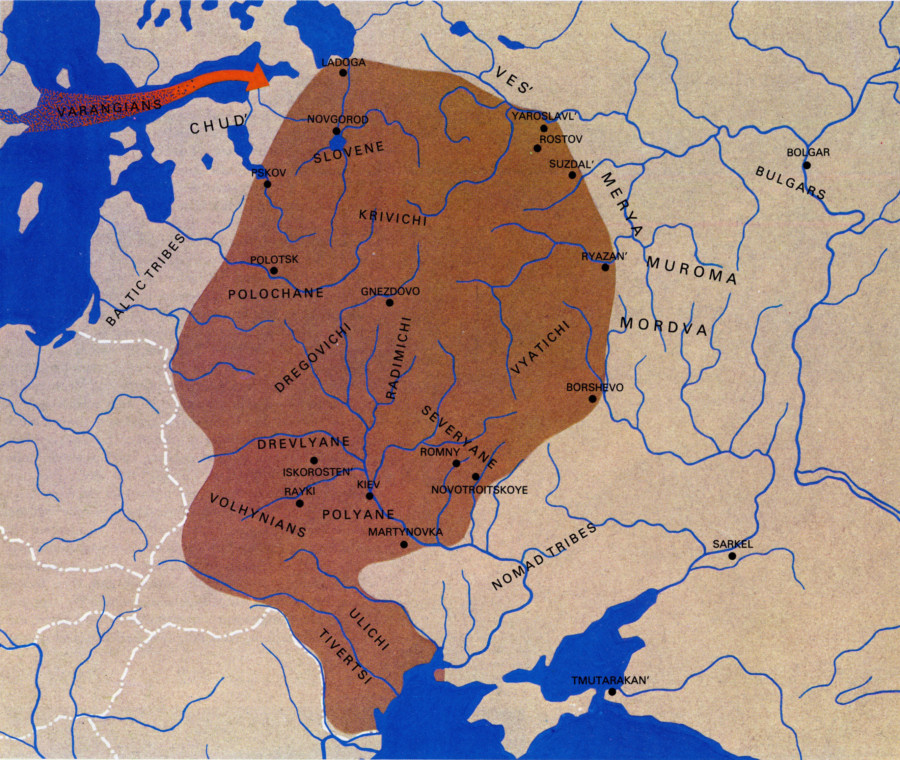

The longest process of resettlement was the Slav migration to Eastern Europe: from the original homeland between the Dnieper, Dniester and Pripyať settlement gradually spread to the vast forest regions inhabited by scattered Baltic and Finnic tribes and to the steppe lands of the nomad tribes reaching as far as the coast of the Black Sea.

The largest number of facts can be found in local sources, unfortunately, however, of a relatively late date: in the Old Russian chronicles of the eleventh and the early twelfth centuries. In the spirit of the erudition of the monasteries of the time and following Byzantine patterns the writer deduced the origin of the Slavs from the scattering of the nations during the construction of the biblical Tower of Babel and placed them in the Danube region, from where they spread to their historic settlements. This seems to reflect the knowledge that the Danube was one of the main axes of migratory movements. According to the chronicles the Eastern Slavs soon split up into tribes. The location of their settlements reveals the range of Eastern Slav migration in the eighth to tenth centuries. One centre was formed by the Polyane in the middle Dniester region around Kiev. To the north-west of these, in the wooded lands along the Dnieper and Pripyať the Drevlyane lived in towns like Ovruch and Iskorosten'. To the north-east of Kiev, along the rivers Desna, Seim and Sula, were the scattered settlements of the Severyane. The Dregovichi lived between the Pripyať and the Dvina. Along the

46

![]()

Poloť, an upper tributary of the W. Dvina, lay the dwellings of the Polochane, with Polotsk as their centre. They were related to the Krivichi, who by stages came to occupy a vast territory in the river basins of the Dvina, Dnieper and Volga. The region east of the Dnieper was taken over by the Radimichi and Vyatichi tribes, whose original home had been the territory of present-day Poland. Further to the north were the Slovene who had their homes in the vicinity of Lake Il'men' where Novgorod was an important centre. The western fringe was held by the Dulebi, later Buzhani-Volhynians (this may have been one and the same tribe which merely changed its name). The southern end of the Eastern Slav branch was made up of the Ulichi and Tivertsi, who settled along the rivers Dniester and Prut, where the frontier with Romania runs today.

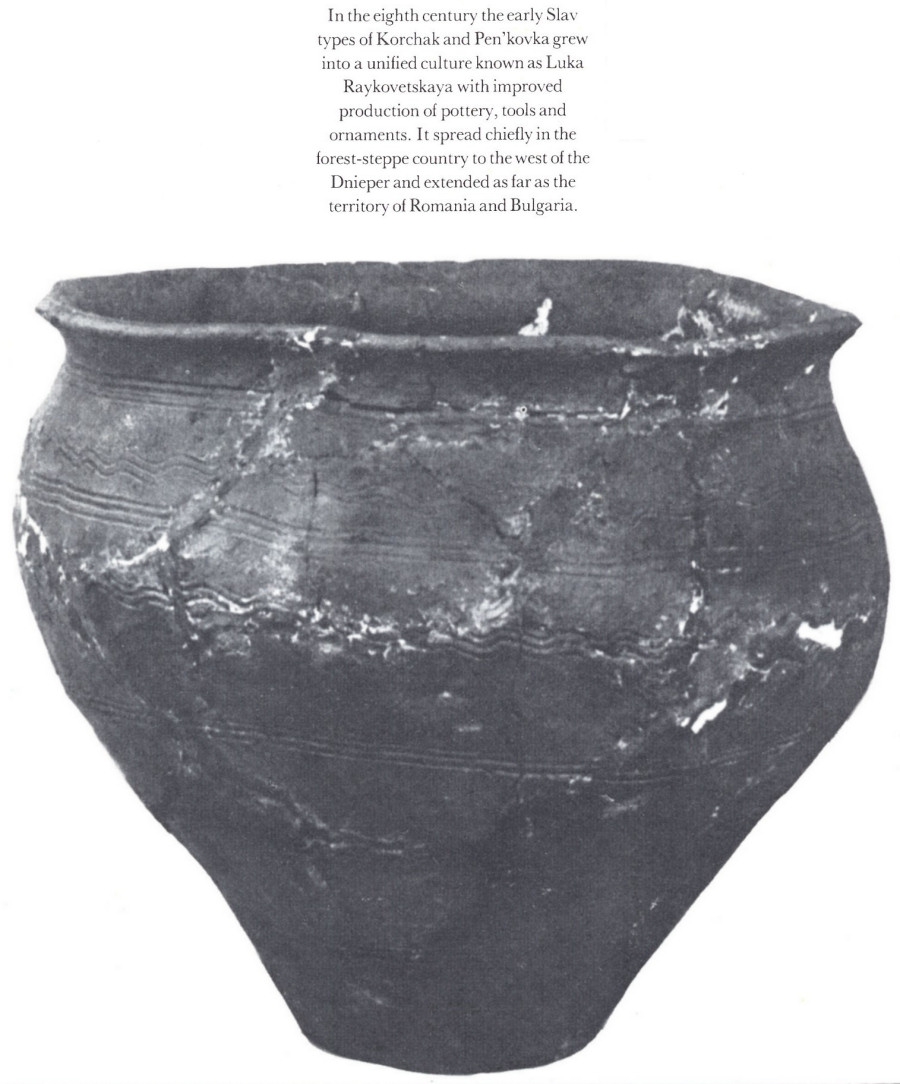

In the eighth century the early Slav types of Korchak and Pen'kovka grew into a unified culture known as Luka Raykovetskaya with improved production of pottery, tools and ornaments. It spread chiefly in the forest-steppe country to the west of the Dnieper and extended as far as the territory of Romania and Bulgaria.

Other important information provided by the chronicler deals with the neighbours of the Slavs — the Finnic tribes of the Ves' in the Byeloozero region, the Merya on the shores of Lakes Rostov and Kleshchino and the Muroma on the confluence of the Oka and Volga. These records lead us to conclude that during the eighth to eleventh centuries the Slavs spread from the original centre between the middle Dnieper, the right bank of the Pripyať and the Dniester to broader regions between Byeloozero to the north and the Black Sea to the south, between the Bug and Dniester to the west and the river basin of the upper Oka and the left tributaries of the

Dnieper in the east. That is all that can be deduced, though retrospectively, from written records, on the basis of data from the turn of the eleventh to the twelfth century.

Archeologists are able to trace the advance of Slavic settlement in Eastern Europe with more conviction although some of their interpretations remain questionable. What is certain is that the starting point of the expansion lay in the region of the early Slavic Korchak and Pen'kovka types between the middle courses of the Dnieper, Dniester and Pripyať. As has already been shown, the movements began while these cultural groups were still in existence and not only in a southerly direction to the Balkan peninsula but likewise to the east, i.e. to the left bank of the Dnieper and upstream along its tributaries from the left.

In the eighth century a new cultural group evolved from the Korchak and Pen'kovka type called Luka-Raykovetskaya after the important site at Rayki. There were typical open settlements of an agricultural people with the usual semi-subterranean dwellings and with the burial of cremated dead, as in the preceding period. Certain improvements had been made to pottery, tools and ornaments. The finds of the Luka-Raykovetskaya type were widespread in the forest-steppe lands to the west of the Dnieper, from where they penetrated to Romania and Bulgaria. A slightly different version appeared on the eastern bank of the Dnieper, for which

47

![]()

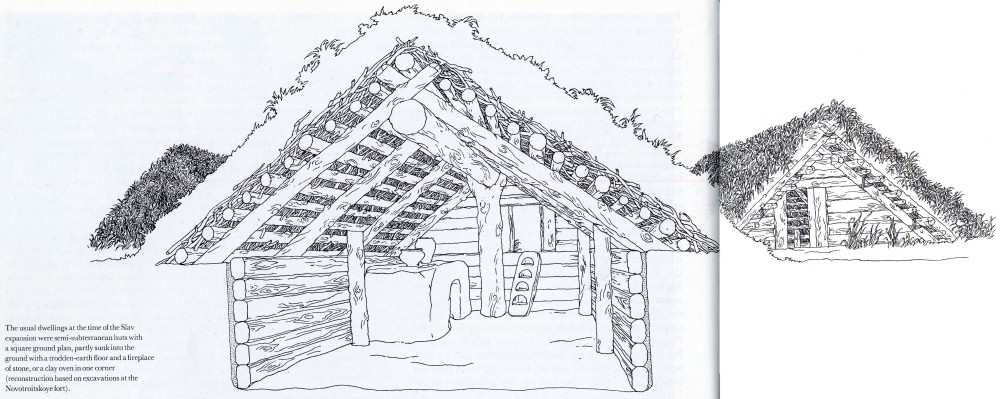

The usual dwellings at the time of the Slav expansion were semi-subterranean huts with a square ground plan, partly sunk into the ground with a trodden-earth floor and a fireplace of stone, or a clay oven in one corner (reconstruction based on excavations at the Novotroitskoye fort).

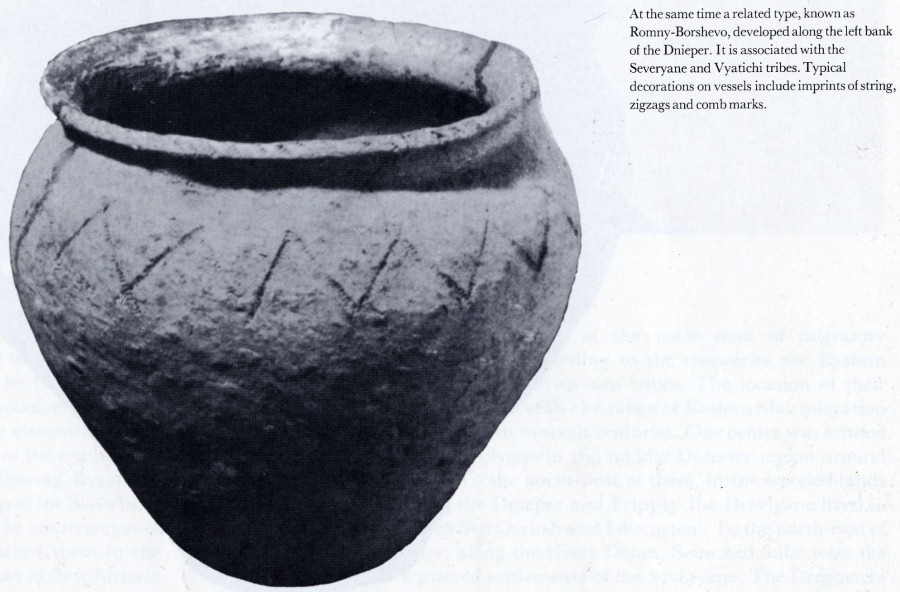

At the same time a related type, known as Romny-Borshevo, developed along the left bank of the Dnieper. It is associated with the Severyane and Vyatichi tribes. Typical decorations on vessels include imprints of string, zigzags and comb marks.

48

![]()

the archeologists have coined the name ROMNY-BORSHEVO (again after a characteristic site). They distinguish in it the Romny group in the Desna valley, which some scholars attribute to the Severyane tribe, and the Borshevo group living to the north along the upper Oka which they identify with the Vyatichi tribe. The Romny settlements usually consisted of a hill-fort and an open settlement linked to it.

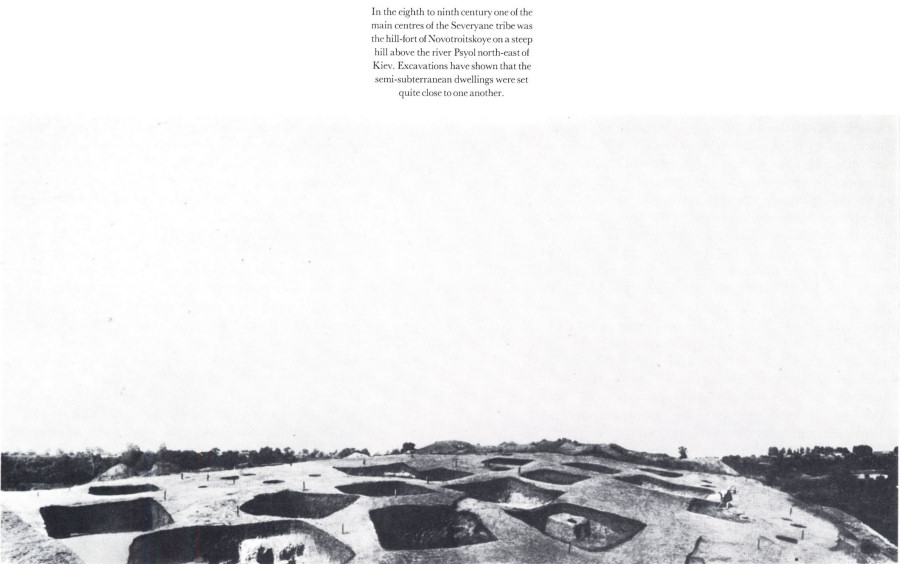

In the eighth to ninth century one of the main centres of the Severyane tribe was the hill-fort of Novotroitskoye on a steep hill above the river Psyol north-east of Kiev. Excavations have shown that the semi-subterranean dwellings were set quite close to one another.

The finds of the Romny-Borshevo type have made it possible for us to trace the gradual Slav colonization south-east towards the upper Don and north-east to the Volga. During the eighth to ninth century these tribes first moved to the rivers Psiol and Vorskla, then to the upper Don and the Seversky Donets, as revealed by the oldest layers of the Donets hill-fort at Kharkov. In the ninth to tenth century the bearers of the Romny culture reached the lower Don, the Sea of Azov and the Taman'. The Slavs who conquered the Khazar Sarkel in the tenth century brought with them Romny pottery. Later they had to abandon their hill-forts on the Don under the pressure from the Pechenegs.

From the area of the Borshevo variant (Vyatichi tribe) the Slavs penetrated to the Finno-Ugric lands in the forest zone, especially Mordva, where the important Slav centre of Staraya Ryazan' came into being on the site of an old Mordva hill-fort. In the different strata archeologists found typical Vyatichi ornaments, e.g. large ornamental rings with seven rays, rings, round rock-crystal beads, and the like. The Ryazan' land then become the centre of the Vyatichi, while their hill-forts on the upper Don were abandoned in the tenth century.

In the northern parts of Russia relations between ethnic groups underwent a very complex development in the early Middle Ages. The upper Dnieper region was ruled for centuries by Baltic tribes, to which the Kolochin-Tushemlya culture still belonged in the fifth to seventh centuries. In view of strong similarities of their cultural model with that of the contemporary Slav groups of the Korchak and Pen'kovka types, they must have been a part of the Balts that was very close to the Slav ethnic group with which they soon merged. The

49

![]()

actual Slavonic element came to the fore later, mainly in the ninth century. Prior to that (in the seventh to eighth centuries) a further wave of Baltic inhabitants came from the west, from Lithuania and Latvia; they used a special form of burial in "long kurgans", barrows, which grew in length with every fresh burial. These barrows had wrongly been considered typical of the Slav tribe of the Krivichi. In the middle of the ninth century armed bands of Scandinavians came from the north and settled on the confluence of the Dnieper and Svinka and together with the Slavs, Balts and Finns established a trade and cultural centre near Gnezdovo. From here the Old Russian settlements spread along the upper Dnieper, where the foundations were laid for the development of the Byelorussian ethnic group, with Smolensk taking over the role of Gnezdovo.

The north-western part of "Upper Russia" (the Novgorod and Pskov regions) was originally the domain of the Finnic tribe of the Chuď. In the sixth and seventh centuries the "Pre-Kurgan" culture belonged to this, but it has not yet been fully investigated. This was followed by the "sopki", tall tumuli that arose as one burial was placed on top of the other — by contrast to the "long barrows" which grew horizontally and spread to this area from the Baltic region in the eighth century. In the past the archeologists had wrongly linked these "sopki" with the Slovene, but they did not appear here until a little later with another culture, which built characteristic hill-forts, produced hand-made and wheel-turned pottery, possessed imports from the Orient and from Scandinavia, and used smaller circular barrows for burials. The Slovene came here in the eighth and ninth centuries following the river Lovať and occupied chiefly the southern regions by Lake Il'men'. This came to form the centre of their tribal lands as a starting point for further colonization. The original settlement was mainly of an agricultural character and introduced a higher stage of economic life — tillage-agriculture which was unknown to the original inhabitants. In the ninth century the watercourses grew in importance, facilitating trade contacts with the world at large. This can be shown by numerous finds of treasures of Arabian silver, which were accumulated along the watercourses and in the main centres, such as Novgorod, Ladoga and Pskov. The main stream of colonists to the east, the upper Volga region, and to the north-west set off from Novgorod in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. During the Middle Ages the ethnically and culturally mixed population of these regions, comprising Finnic, Baltic, Scandinavian and Slav elements, grew into the Old Russian nationality.

The extensive archeological research at Novotroitskoye has made it possible to reconstruct the original form of an Eastern Slav hill-fort, which was probably destroyed by raiding nomads in the ninth century.

The historical development of north-eastern Russia, the Rostov-Suzdal' land, can basically be reconstructed only from archeological sources. Originally three Finnic tribes lived here, the Ves', Merya and Muroma. Their culture with typical ornaments, bone products, bowl- shaped vessels, can be traced by archeologists on burial grounds of the sixth to eleventh centuries. In the ninth and tenth centuries a wave of settlers arrived from the region of the Il'men' Slovene, and later the Krivichi in the upper Dnieper region, who over the centuries mixed with the local Finno-Ugric population.

The ninth centre must be regarded as a milestone in development. At that time a centre of Slav settlement arose at Yaroslavl' on the Volga. Its early phase is represented chiefly by barrow burial ground from the ninth and tenth centuries. But we also know of fortified settlements, which became the centres of Slav expansion, e.g. Timerevo, which came into existence at the end of the ninth and the early tenth century when colonists appeared from the north-west. It flourished in the tenth century but, in the following century, gave way to the new centre at Yaroslavl'. The Sarskoye hill-fort (on the river Sara) developed similarly; in the tenth century it was a large production and trade centre of the Rostov region, with a mixed Slavo-Finnic population, with the Slavs forming the majority. The feudal city of Rostov then became the successor to the Sarskoye hill-fort. Another important centre was Byeloozero, which from the early ninth century on held the role of the terminal of eastern trade, where the main route turned back from the Volga to the west, to Novgorod and Ladoga. The Slavonic element did not become dominant here until the tenth century. The finds of pottery and ornaments show a mixed Slavic and Finno-Ugric style. This reflects the ethnical process of the birth of the Old Russian and later of the Great Russian peoples. Similarly along the upper Dnieper the Baltic substratum was overlaid by the Byelorussian nationality, while the

50

![]()

Ukrainian nationality developed in the original middle Dnieper region.

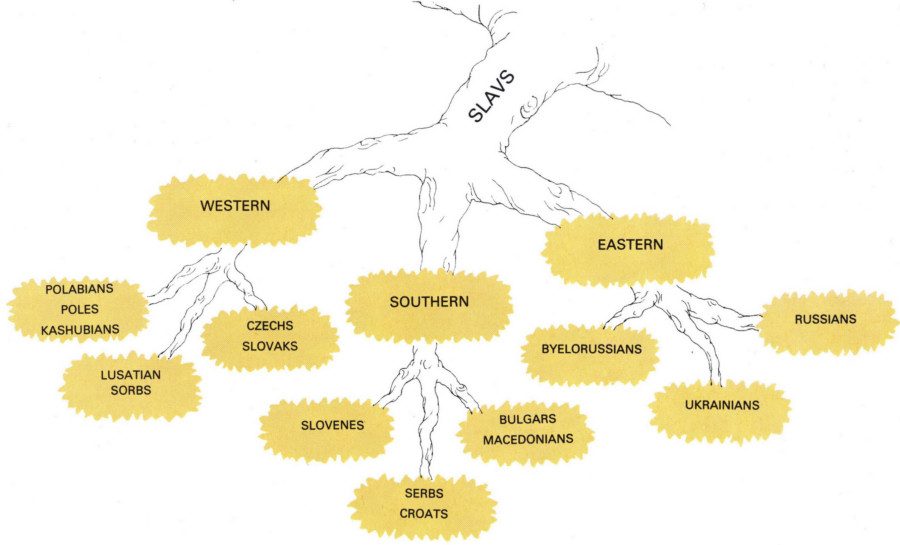

Once the migration process of the Slavs and the consolidation of their new settlements was finished, differentiation occurred among the originally unified ethnic group, which split into three main branches — the Eastern, Western and Southern Slavs — and individual national languages began to develop.

The establishment of the Kievan state at the end of the ninth century gave a decisive impulse to Slav settlement in Eastern Europe.