The "labor boys" drain a swamp

CHAPTER VIII

Obligatory labor

Bulgaria has one institution found practically no place else in the world, namely obligatory labor service for the common good. It was introduced as a result of the war and in direct .consequence of the Neuilly Peace Treaty, which prevents Bulgaria from maintaining obligatory military service such as is practiced in other European countries. One of the purposes of this measure, undoubtedly, is to give the youth the physical training and discipline which they used to find in the army, in other words to afford a substitute for one of the useful functions of military training. But its principal aim is to mobilize the man power of the. country and to perform essential public works.

Obligatory labor service is of two kinds: regular and temporary. The regular service is performed once by all young men upon reaching the age of 18 and lasts for a period of 8 months. In some ways it resembles life in the army. Temporary labor service is performed every year by all adult Bulgarian citizens for a period of not more than 21 days. Both women and men are subject to it but as a rule only the men are called and they seldom serve more than ten days annually.

When one bears in mind that each year not less than 45,000 boys reach the labor service age and that there are always approximately three quarters of a million adults always subject to temporary service, he realizes how extremely difficult it is to organize such a vast army for effective work. To make this problem still more difficult, the 800,000 school children are required by the law to perform a number of days work for the common good each year.

It is plain that in order to work effeciently, the laborers must be both organized and equipped with tools. In addition, if they would make roads or bridges or straighten rivers or plant trees or repair buildings or whitewash walls they must have certain materials, but neither the state, the countries nor the communities are in a position to provide every man, woman and child in Bulgaria with hoes, shovels, axes, picks and other necessary implements nor can any social institution supply the culverts, cement, lime and lumber required for the desired constructions. And even if this were possible, where are the experienced engineers necessary to organize and direct such a horde of untrained and more or less unwilling workers. Manifestly it has not been easy to realize all the good intentions of this law.

Yet many of the difficulties have been overcome, order is being established and excellent results are being obtained. Naturally, least of all is accomplished by the school children, but even here there have been solid achievements. If you should pass through the long main street of Samokov, a city in southwestern Bulgaria and turned to the left as you proceeded you would notice a beautiful young pine wood, topping the whole crest of the range of neighboring hills. This is an artificial forest and much of it was planted by school children during labor days. In other places also trees have been set out, gardens planted, school and church yards tidied up, fences repaired, public buildings cleaned and whitewashed. And best of all hundreds of thousands of children at the- end of labor day returning the hoes, spades, picks and wheelbarrows to the places from which they have borrowed them feel that they have done something for somebody else.

More substantial achievements stand to the credit of the temporary labor service for adults, even though the law is not applied in all cities and villages. As a matter of fact it is a dead letter in many places. But when the local officials are energetic and efficient and all the men are required to do ten days service annually, many useful improvements are effected. A comparatively large number of towns and villages have been surveyed and the streets widened, paved and straightened; hundreds of miles of local roads have been constructed, not a few substantial bridges have been built, schools and reading rooms have been erected, water has been piped to many villages and a few cities, while in several districts electric light plants have been set up. Dikes have been made along low banked rivers and in at least one wide, low plain — near Sofia — a very extensive project for shortening a winding river and reclaiming land is being carried out. Hundreds of acres of trees have been planted by the temporary laborers and helpful public health improvements introduced.

The "labor boys" drain a swamp

On the whole, the experiment is encouraging. The last decade has seen a large number of public works finished in Bulgaria and an appreciable part of this advance is due to the temporary compulsory labor service, although a very much larger proportion to the regular labor service. It is the work of the labor boys or "troudovaks" that has definitely established the experiment as a useful venture and made it a permanent Bulgarian institution.

None of the 45,000 boys who annually reach the age at which they become subject to this service can escape the obligation. No youth can get a passport to leave the country or even to study abroad until he has discharged his labor duty or had it postponed or given a deposit to serve as a guarantee. In certain cases it is possible to give the state money rather than actual work.

The discipline of the "troudovaks", the treatment they receive and their method of life is not unlike that of military recruits. They are given grey uniforms by the state and on their caps is an official brooch, bearing the words "work for Bulgaria". They have their flags, their music, their songs and their bands. On entering the service they solemnly take an oath to be faithful to King and fatherland and conscientiously to discharge all their duties. They are organized in units, placed under rigid control and subjected to strict and regular training.

The labor units are designed to be both schools and work shops and they are. A great deal of attention is given to moral and physical education, The boys are taught a certain labor creed containing the highest ideals of loyalty, comradeship and service. They have their own publications, are given opportunities to hear interesting talks, to arrange entertainments, and in their daily life to learn of regularity,-honor, cleanliness and fidelity. Holiday rests are strictly observed and when possible the boys are permitted to spend the week ends at home.

'They live in camps rather than army barracks for they are always at the labor fronts. Sometimes their shelter consists of tents but more frequently of little wooden huts arranged in neat rows on some grassy plot beside a stream. It is a good deal like camping out, an obligatory adventure of youthful knights serving their fellows.

And the service they render is manifold. Well over half of the boys work on roads, some build railroads, others reclaim swamps and a few work on the state stock breeding farms. Large units work in the big state lumber plant on the shore of the Black Sea, others are engaged in arhaeological excavations and a fairly large number of "maistors" work in the state shoe and tailor shops.

Building shacks for earthquake victims

If one could cast an all-seeing eye over the whole of Bulgaria, exploring rivers, swamps, mountains and sea shore, he would discover that the "troudovaks" have written their name large in many places. They have built two new harbors on the Black Sea, bringing into touch with the rest of the country an isolated corner that during winter months has been almost completely cut off from the world since 1913, when it passed from Turkey to Bulgaria. They have pushed roads across the swamps south of the harbor of Bourgas, walled the capricious and occasionally furious Ogosta river at a point where it was eating away the land from beneath the village of Glozhene, and in a remarkably short time, they drained a large swamp lying in the rectangle formed by the parallel rivers Isker and Veet, at the place where they empty into the Danube. This achievement, on which the state as well as the district and communities concerned had been working for nearly two decades, presented many engineering difficulties which the "troudovaks" overcame in a brilliant manner, thus reclaiming 40,000 acres of exceedingly rich land.

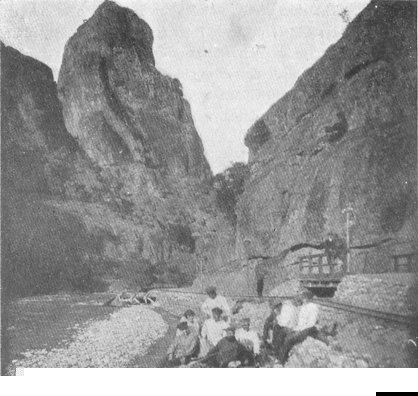

But the roads which the labor boys, working as living shuttles, have woven back and forth across the Balkan mountains, represent their greatest accomplishment so far. Naturally, when Bulgaria came into being as an independent state she at first confined hsr road building to the great lines of traffic and especially to the plains and valleys. Highways were more needed and were easier to build there and served larger and fast growing cities. Yet that policy left the little mountain towns which are scattered throughout the whole length of the Balkan range isolated and neglected. It was inevitable that they should decline in the face of the advancing plain cities, but the lack of communications added unnecessary impetus to this backward movement. And this was an especially keenly felt tragedy for it was these very mountain cities that had brought Bulgaria national consciousness, spiritual awakening and enlightenment. But since their inhabitants had to travel around three sides of rectangles or negotiate S-s and V-s in order to get to the market centers, business life in them could not keep up with the pace set by the plain towns and they could not prevent progress from rushing past them. Panting oxen pulling half filled carts along poor, circuitous roads winding about mountain peaks could not keep up with the horses trotting over the smoother roads of the lowlands. But the "troudovaks" have brought these proud old towns a belated reward. Through the Balkan Mountains, from the extreme west end of the range clear to the Black Sea on the east, at irregular intervals as passes permitted and traffic required, the boys have cut cross roads bringing them into far more direct touch with the rest of the world and opening a number of the most picturesque highways in the Balkans.

A moutain road built by the "labor boys"

But that range is not the only ridge of mountains in Bulgaria. It is the husband but there is also a wife, more beautiful even and taller than her man. They were once, many, many centuries ago the happy King and Queen of rich and level Thrace, but they offended the rather touchy gods on Olympus who punished them by turning the King into the Balkan range, classically known as Haemus, and his wife Rhodope into the wild and imposing line of mountains in Southern Bulgaria, one peak of which is the highest in the Balkans. Never have good roads pierced this forbidding range though half a dozen rivers at frequent intervals have cut convenient passes through it. But now at last the labor boys have begun excavations and are building automobile routes to the villages and straggling towns on the south side 'of the ridge. This army of recruits operating along a far flung front is using its powder and dynamite to bring prosperity and enlightenment to a long neglected no man's land.

A good deal has also been done by the "troudovaks" toward improving the Bulgarian railroads. Practically the whole of the Bulgarian railroad system has been created since the liberation of the country half a century ago. At that time there was not a single through line in the land. Naturally one of the first things the new state set out to do was to build new roads and the contracts and concessions for their construction usually provoked tempestuous political campaign. Nevertheless in spite of the rise and fall of government the work was pushed steadily ahead and by the outbreak of the Balkan Wars, which were a prelude to the World War, Bulgaria had 1,200 miles of railroads, forming a system that resembled a very short handled, long pronged Y. The stem was the trunk line coming in from Europe through Serbia, extending from the western Bulgarian boundary to Sofia, the capital. There it split into two branches one going north through the Balkan range and then continuing east to the port of Varna on the Black Sea, while the other ran east from Sofia on the southern side of the Balkans, terminating at Bourgas, Bulgaria's southern Black Sea port. The line north of the Balkan range also split into a Y sending a branch north to the Danube river and Rumania, while the line south of the Balkans likewise split, sending a branch southeast to Constantinople. These "splits" are described here geographically and not chronologically; for the lines and branches named were not constructed in the order I have given. In fact some roads I have called branches were originally main lines. Nevertheless the Bulgarian railroads before the Balkan wars represented a Y or a tree with a short trunk and two long main branches, each giving off another important branch. There were little twigs too shooting out here and there, especially from Sofia. This system of railroads though forming an excellent frame work left much of the country unserved and was in need of being filled in, with lines running across the

Balkans, through the Rhodopes and to many outlying points. And it is that work which many of the "troudovaks" are engaged in. Using a part of the recent refugee loan, specifically given for that purpose, as well as other sums taken from current budgets, the labor boys have already constructed a considerable number of new railroad lines, appreciably improving Bulgaria's network of communications, and this work is still going ahead with much vigor. At the beginning of 1931 Bulgaria had 1,815 miles of railroads, which means an increase of 480 miles during the 12 year period following the World War. Not all of this new mileage was laid down by the "troudovaks", but much of it was. It has cost on an average about 1,000 dollars a mile. It costs about a cent a mile to ride on them.

The "labor boys" construct a new railroad in southern

Bulgaria

But the labor boys not only dig into the future, creating new communications for coming generations; they delve into the past as well, establishing connections with very ancient epochs. One of their most interesting activities is that of excavating old historical sites. They are helping archaeologists learn more of the civilization created by the old Bulgarian Kings who swept into the Balkan Peninsula from the vague, mysterious, legendary North, set up flourishing capitals at Preslav and Aboba in northeast Bulgaria, left one of the most remarkable horsemen in Europe cut into the face of a grand ledge of rocks not far from Varna, and conquered almost the whole of the Balkan Peninsula. During every work season the "troudovaks" uncover part of these old capitals, constantly bringing to light new information regarding ancient days of regal splendor.

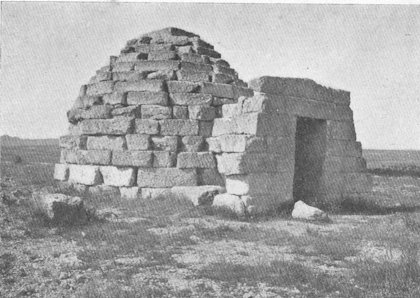

A grave originally covered by earth — such as were left

by very ancient inhabitants of Bulgaria living there a millennium B. C.

Some work has also been done on old Roman settlements of which there are not a few in Bulgaria and much has been accomplished toward uncovering the old burial monuments that dot some of the Bulgarian plains. These hills were erected before the Bulgarian Slavs or Romans came to the Balkans and are the creations of a people, older than the Greeks of ancient Athens but much influenced by Greek culture. Practically all these early inhabitants have left is dirt hills, at the base of each of which there always lies a decayed coffin containing a few metal ornaments and clay dishes. More has been done toward studying them since the "troudovaks" became archaeologists than at any other time. The labor boys, in well conducted work shops, make shoes and clothes not only for themselves but for a part of the state police force. This activity has enabled the state to effect a very appreciable economy, for the "troudovaks" have shown that they can make shoes and coats considerably cheaper than any private contractor. They tend extensive gardens producing large quantities of excellent vegetables. They conserve fruit and vegetables for use during winter months. They built tens of thousands of huts for the people made homeless by the earthquakes of 1928 and helped rebuild ruined towns and villages. And they conduct one of the most extensive and successful lumbering enterprises in the country.

Into the Rilo Mountains with the narrow gauge railroad

The Obligatory Labor Service is managed by a general superintendent at Sofia who is assisted by fifteen district superintendents. The chief receives ninety-three dollars a month and his assistants forty-three dollars. There are also a fairly large number of engineers in the service who direct the various projects, often aided by state or district engineers.

Whenever a town, village or county wants the "troudovaks" to help build a dike or road it applies to the proper district superintendent, assuring him that it will provide the labor boys with food and lodging. When the labor companies arrive, they are received with music and folk dances as boys going to the front and when they leave with their task accomplished, they are sent off with festivities, speeches, flowers and expressions of thanks, and it is said they more heartily enjoy the last folk dance with the local maidens than the eloquent addresses of the local fathers. It usually costs fifteen cents a day to feed a "troudovak".

At first the regular Obligatory Labor Service did not pay for itself.

It was a burden rather than a benefit to the state. So much had to be paid

for tools; transport, material, expert supervision, clothes and quarters

that the labor service cost the state more that it brought in. But experience

and an improved organization caused a turn in the tide and now the "troudovaks"

are a very productive source of income. The profit they bring the state

is steadily mounting with each year that passes. They are among the best

patriots in Bulgaria and as they stack their shovels at the conclusion

of their service deserve all the honors that we give to soldiers doffing

the garb of war.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]