Young King Marko's Towers

CHAPTER VII

Romance in the village

B.

The Bulgarian fairy stories are like American movies they usually end well. In this respect they resemble all fairy stories. They are really for children and children feel cheated at bad endings. They were brought into lonely villages from all sorts of places. Bulgaria was for centuries part of a vast Turkish Empire and a few of the people travelled widely to sell cheese, knives, flutes, bagpipes, cloth or grain, while others journeyed abroad and bought modern articles to sell to the neighbors back home; a still larger number went to work as gardeners or "maistor" builders and not infrequently some of the more vigorous men were taken far away into exile as revolutionists. They all knew some Turkish and also Greek and while visiting market places, resting in little wayside inns, riding in carts with other travellers or lying in jails they heard stories of princes and angels and heroes and witches. When they returned from their distant wanderings they were marked persons in their villages and received much attention which was not at all distasteful to them. So you may imagine one such at the bean-shelling bee. The whole village has crowded in to see him. There is no banter and sharp laughter, no song and teasing as usual but all are quiet, as the guest of the evening talks of the lands he has seen and relates the stories he has been told. He so mixes up the fanciful with the actual and what he saw with what he heard that reality and fiction blend into one, and spirits and men live together. On the following days as he meets with the men in the village saloon, he finds a still tenser audience. The tiny glasses are not refilled with the light yellow whisky and the pitchers of wine remain unemptied as men and youth lean over bare board tables in order to press nearer to their returned comrade and hear his wonderful tales. This pleasure which the Bulgarians have in listening has survived newspapers and radios and movies and very often today in the train or market place or saloon you will meet groups of eager men crowding about a fellow who is reading or talking. And in former years when a fairy story was lanched in some fortunate village you may be sure that inventive and enterprising peasants passed it on to their neighbors, brightened and enhanced, so that by the time it covered Bulgaria it was thoroughly localized. It was full of good advice and sound warnings, it left the bad people with their heads cut off, distributed bounteous rewards to the virtuous poor and brought the pious hero into possession of the fields, the hidden treasures and the bride.

Young King Marko's Towers

The fact that these stories were preserved for centuries in a bookless world of illiterate people shows that they were very popular, but still not so popular nor so original as the folk songs.

These are of two kinds, which we may roughly classify as heroic and domestic. Generally speaking the heroic were composed and sung by the men and the others by the women, though there were some sung by both, the girls taking one line and the boys answering with another. These songs without question were the finest artistic productions of the Bulgarian spirit up to the recent dawn of modern Bulgarian literature. They may be favorably compared to the folk songs of any other nation.

And it must be borne in mind that they are songs and not mere poems. They were sung to music and not recited. The producer of a song composed both the words and the melody. And the music though strongly influenced by the Orient is a distinctly national creation. It is the specific product of the Bulgarian spirit and is different from that created by other primitive peoples. The words themselves are quite simply constructed. The verses are ordinarily made up of short lines which as a rule do not rhyme. As in the songs of the American negroes, there is much repetition. An effect is produced by saying the same thing over and over again in slightly differing ways. One line frequently begins with a phrase with which the preceding line ends. It is due to this monotony of the words and the prevailing minor tones that Bulgarian folk songs leave an impression of sadness even on people who do not understand the words. Generally speaking, they are not gay. In this they resemble the melodies of the American negroes. But they also show a striking difference. The negro expects God to make it up to him in heaven, where all of God's children will have wings, but the Bulgarian's gloom is brightened by no such expectation. He sorrowfully accepts his lot and resigns himself to God's grim ways.

The heroic songs are, in my opinion, not as good as the domestic ones, although many Bulgarians are not inclined to admit it. However, this inferiority of the epic songs seems to me quite natural. The Bulgarian is by nature not a rover nor a fighter. He is a peasant, a tiller of the soil, a dweller in settled communities. His loyalties are rather narrow and he is not awed by royal authority nor by the glamour of courts. He tends to be more interested in his crops and animals than in military glory. Some people will consider this estimate a slander and others praise, but I think it is based on facts. The Bulgarian peasant did not pour out his soul in bewailing the fall of his kingdom.

He sang about very few of his kings. He immortalized no crowns and no sceptres. The old Bulgarian kingdoms during most of their existence were foreign to him. In this respect the Serb is somewhat different; he brought his genius to the highest point in the creation of epic songs. Serbian heroic folk creations have justly won the praise of all Europe.

Tis a holiday and these girls are going to visit their

neigbors and sing "good luck" songs

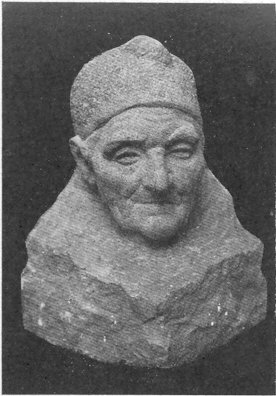

This does not mean that the Bulgarian does not like heroes. Everybody likes heroes. And blind Bulgarian minstrels often sang of them, to the accompaniment of their little, one stringed fiddles or "gouslas". They occasionally twanged the praises of their departed kings, submerged under the torrents of Turkish invasions but much more frequently and enthusiastically extolled the daring feats of the most popular figure in all Balkan folk lore, Young King Marko. No character in human history has fared so well in the hands of posterity as he. Marko was really a Serb but every single one of the Balkan peoples has adopted him as its very own, as its dearest hero. And not only did the Balkan singers carry his fame across all boundaries and make him indigenous in every land but they completely transformed him. As a matter of fact, Young King Marko from the beginning to the end of his career was anything but a noble character. He did all that a decent leader should not have done and besides committed the utterly unpardonable crime of actually going over onto the side of the Turks against his own Christian people. Yet by a marvelous artistic conspiracy the Balkan singers picked out this very ordinary roisterer and made him the chief actor in countless wonderful exploits. They turned him into a fascinating Richard the Lion Hearted or Aladdin.

Of course, squeamish people could find lots of fault with Young King Marko even after his ardent admirers have recreated him. This rollicking adventurer, adored through scores of decades by half a dozen nations, was no Sunday School boy. His fame certainly would not have lasted long in Kansas for he was a terrible drinker that was indeed one of his greatest accomplishments. He could outdrink them all and he never saw double nor lost his head. He also liked to jolly the girls and revelled in bluster, swagger and boasting.

But he was very good at heart, in fact, that was the whole secret of his charm he was a "good fellow". It goes without saying that he was rough and boisterous. He would be ashamed to say "isn't" in the place of "aint" and used words much stronger than "golly" and "gee whizz". He was very fond of making real, bloody killings and was forever saving poor Christian youth and damsels from Turks and Arabs. And he never missed a fight he was always too proud not to fight. Though he did sometimes get scared and regret that he had plunged into the combat so precipitously.

He was very good to his mother in his rough way and on the whole was very decent to women, though insisting of course on a bit of hearty flirting. He was quite given to lying and rather gloried in his triumphs along that line. He was even treacherous, if one could be considered treacherous then, in his dealings with Turks. His picture would be the last one that a school principal would hang up in the class room as an example to growing youth, yet you may be sure that growing youth adored him. He always rode a marvelous winged horse called Spot who was as much of a hero as the master. Marko carried an enormous club with spikes all over it, wielded a gigantic sword and had very capacious wooden wine flasks tied to his ponderous, heavily ornamented saddle. He had long ferocious mustaches and was a rough and ready knight that most men and boys would have gone a long way to see. He never was completely killed but has been hiding for several centuries in a cave in Macedonia from where he is to appear some day.

Even in a village there's a way to give your best girl

a thrill

Young King Marko was the Balkan movie star long before even Shakespeare was born. He was a Babe Ruth of obscure Bulgarian villages for a number of centuries. Every boy would have been glad to touch that big stick and hold old Spot's bridle reins. And in primitive lands human males never cease to be boys. Most of them do not even in civilized lands and times. Marko was a Douglas Fairbanks of his time. He gave the public all the thrills of modern movies: fighting. Spot's furious racing, cleverness, saving maidens, slaying villains, being good to mother, making justice triumph in the end. Watch those rough, unshaved, sheepskin clad men and their sons gathered in the market place about the blind minstrel. He sings a song or two to get warmed up and the impatient public cries, "Marko, Give us Marko". Then someone passes the singer a little red wine to loosen his tongue and as the crowd stands silently strained, in a -spirit of high expectation, Marko begins his exploits. You see him challenging some insolent old Turk who has stolen some helpless damsel. Resounding and picturesque insults are exchanged such as Goliath is reported to have flung at David. Then they separate for a moment. Marko gets some good advice from his uncannily wise mother, after which you hear the stupendous hoofs of old Spot tearing over mountain and dale toward the enemy. Now the battle is joined, swords meet swords; a whole company of villains set upon lone Marko who, aided by the miraculous movements of Spot, swings that awful spiked club, breaks a dozen heads, grabs the poor maid and rushes back to deliver her to her papa or sweetheart, who receive him with many lines of moving poetry and no end of good things for him and his horse to eat and drink. Such was Marko, the movie star of long ago, and those fascinating reels in which he acted have been preserved to this day.

Of course, there were other heroes too, for there is more than one Babe Ruth in baseball and more than one Douglas Fairbanks in the movies. Other very popular stars were the "haidouks" or mountain bandits, who were believed to be noble Robinhoods defying laws, killing rulers and robbing the rich for the common good. Since in those days laws were made and enforced by foreign oppressors no one seemed quite so adorable and inspiring as an outlaw. The pillars of society usually rested on subservient allegiance to foreign despots so the masses loved the brigands who ;were bold enough to tear them down. The highest civic duty was to be against the government and the "haidouks" who put this principle into practice got their names in all the papers, that is they were sung about in all the saloons and market places.

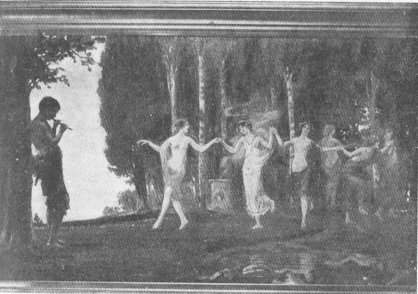

by N. Miliailoff

Bulgarian nymphs. Almost extinct, one seldom meets them

These heroic and masculine songs, however, were not sung so much nor by so many people as the domestic ones an enormous number of which have been preserved, covering every phase of contemporary life. Many of them, of course, were means of entertainment just as the men's songs, but on the whole they were far more than that. They were philosophy and religion; they were inspiration and comfort, instruction and reproach. They were used on every conceivable occasion, by individuals and groups, in choruses and as dialogues, solos and simple folk operas. They constituted the chief way in which a people expressed its feelings. Some of them are extraordinarily delicate and many of them are very clever. What surprises one is that illiterate people, so ruthlessly oppressed and living in such crude, hard environment, could experience such exquisite sentiments and express them so precisely and beautifully.

There are a large number of religious and mythological songs, connected for the most part with the many Bulgarian church holidays. Most of these are not mystical in nature and contain little theology. They are instead quite practical. One of their purposes was to see that folks gave the gods their due so as to keep them in good humor. These songs were for health and good crops, freedom from pests and calamities. They were also beautiful expressions of the pleasure coming from human fellowship at Christmas, of Easter expectations, of autumn satisfaction and of the joy of work in the summer fields. They were almost as much pagan as Christian.

Then there is a very extensive group of family songs dealing with births, weddings, death, journeys, family loyalties, harsh mothers-in-law and loving mothers. There are work songs for hoeing, mixing bread, going to and from fields, spinning, weaving and everything else. There are a few excellent nature songs of woods, mountains, rivers, winds and the sea. There are many very moving elegies for departed loved ones and a multitude of ballads dealing with accidents, calamities and family tragedies, some of which are of a high order.

But none of these are equal to the best of the love songs. It is these that represent the chef d'oeuvre of the anonymous Bulgarian folk genius. And they are of a distinctively feminine nature. They are mostly about "little maidens" and about "wild youth" too of course but in almost every piece you can see it is the "little maiden" who sings the song. She usually gives herself the best of the bargain, and if you have any feeling at all she inspires within you a warm admiration for the spirited girls in those obscure little villages. Of course many of these compositions, like the foolish English ditty, intimate that girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice while boys are composed of very much less desirable ingredients. The little maidens of Bulgaria did not sing anything quite as crude as that - but they leave you with the delightful impression that they were inspired by just such a sentiment. They make the boys out to be rather dull and sluggish and not quite aggressive enough at loving; they even call them pieces of cheese, clodhoppers, mud faces, crazy Jakes and other uncomplimentary things like that, which must have made a great hit at the husking bees. They also take great delight in singing songs in which the boys "get the mitten" in a very peart fashion and they rather enjoy describing how the boys simply burn up because of their love for the girls who, they say, cannot help it.

If this bear walks over you when his gipsy master first

brings him to your village, you will be cured of all your ills

The love in the best of these songs is an exalted and ideal emotion. It is free from all Orientalism and voluptousness. The body is not emphasized and never described in much detail. The loving itself is not dwelt upon. There is no philosophy, no transforming of love into a divine manifestation and no concupiscence; but rather rapture, thrill and ecstacy over the fact that two persons in love have come to possess one another through all eternity. The songs are usually short, direct, bright, vital with feeling. The boy is wildly enamored, noble, utterly devoted. The girl is pretty, infatuated and triumphant. The best songs of this type describe the frustration of love and the victory of the lovers in a united death. Here there is no coquetry and no flippancy but a majestic, overwhelming passion as exalted as in the finest classic poetry.

Of course, there is a good deal of flippancy in some of the love songs

for even the Bulgarian "little maidens" were modern as young women always

are. They liked to provoke the boys and tantalize them and make fun of

them. They liked to shake their heads and make the flowers in their kerchiefs,

quiver. They liked to swish their many pleated skirts and swing the white

water kettles balanced over their shoulders. They delighted in daring and

challenging and got a special thrill out of singing about their running

off with boys, not of course for the sake of an adventure but to defy obstinate

parents and to live with their lovers ever after. They never tired of singing

about dreams and about girls asleep in the woods or gardens, whom bashful

boys were too timid to kiss. How such a song must have taken on a winter

evening before a gathering of youth shelling beans in the weak and fitful

light of tallow candles! Some spirited girl leads the chorus and with more

ardor than melody all the "little maidens" join in the song about the "boy

who did not know how to love" but seeing his sweetheart asleep in the grass

passed by without daring to awake her with a stolen caress, as a result

of which she never spoke to him again as long as she lived. What laughter

that must have provoked! How the girls must have thrilled at their boldness

and how many of the "wild youth" must have gained new courage and decided

to "show those maids".

|

|

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]