The largest and best Agricultural College in the Balkans,. a branch of the Sofia University

CHAPTER V

Making a Living

B.

Village cooperative societies and the Agricultural Bank have changed the economic aspect of the villages and saved the poorer peasants from the clutches of heartless money lenders. There is no aspect of Bulgarian progress so heartening and reassuring as the persistence with which the Bulgarian peasants are themselves creating useful local institutions. Six decades ago "green interest" was the curse of Bulgaria. It was a predacieous and insatiable monster, literally eating the people up. In the spring, poor peasants, pressed by urgent need of seeds and food, borrowed wheat from certain usurers, usually saloon keepers, and in the fall when they threshed their harvest they generally paid their loan back, returning double for the wheat or corn they had received a few months earlier. Furthermore, there was no written contract and the usurers so manipulated the accounts that the peasants never got out of their clutches and the debts kept piling up and up until hundreds of them lost all their land. Now, thanks to the villagers' own initiative, which is supported by the state, that bane has been abolished.

Another matter to which the Bulgarian state has given special attention ever since its creation is agricultural education. It has in Sofia, as one of the departments of the State University, the largest and best equipped agricultural school in the Balkans, in which a staff of able professors are training a personnel of devoted agricultural experts both men and women to work among the peasants in all parts of the country. It also maintains a number of experiment farms which, by means of. countless trials, ascertain what seeds and what animals are .best suited to various parts of the country, and make practical demonstrations of the benefits of scientific farming. It has three secondary agricultural schools for boys and one for girls as well as one superior domestic science school for girls and eight practical agricultural schools for both boys and girls. These girls' agricultural boarding schools deserve special mention since they are designed to prepare their pupils exclusively for the best possible life in a village. They are not stepping stones out of the village, are not vestibules to office jobs nor to any kind of state service; rather they teach peasant girls under ideal conditions all that will help make them better peasant wives and mothers.

There are also 100 supplementary agricultural courses, which are maintained in the villages for peasant boys. and girls who have finished the eighth school year. They are of twelve months duration, divided into two equal parts, given in consecutive years, and their sole aim is to prepare the youth not for bureaucratic service but for a better type of village life.

There exists, in addition, a whole network of Agricultural "Kathedras", one in each county seat, supplied with trained staffs of farm agents, both men and women, who supervise the work of the peasants, give all kinds of advice, direct the fights against epidemics and pests, encourage the construction of model houses and barns and open special practical courses for village men and women. One of the most stimulating activities of the agents or "agronomes" working under the direction of the "kathedras", is the arranging of contests in stock raising, animal improvement, increased production and modern farm methods. The state encourages all who participate in these contests by giving seed, animals and building on very favorable terms, as well as by presenting all who exceed a certain minimum result with substantial prizes.

The largest and best Agricultural College in the Balkans,.

a branch of the Sofia University

There are stations throughout the whole of Bulgaria where villagers may take advantage of the services of superior breeding animals, free of charge. There are also special seed producing villages scattered here and there in which all the peasants receive special aid and are required under strict, expert supervision to plant only the best seed and tend their crops by the best methods.

The superior results obtained here convince hard headed peasants in the adjoining country of the economic advantages gained by using good seeds and modern methods. The state also through its agents exchanges good seed grain for ordinary grain without charging anything extra. It distributes too a large amount of farm machinery at cheap prices and on the installment plan, without charging interest. As a result of these efforts 300,000 iron plows are now in use in the country as well as 2,500 drills, 8,000 threshers and 30,000 iron harrows. Never has land in the Balkan Peninsula been plowed so deeply nor tended so well as at present by the Bulgarians. And it must be added, that to this improvement in the life of the Bulgarian peasants no one has contributed more than the 15,000 village primary school teachers and the 2,000 priests. Many of them have their own model farms which, though tiny, serve as effective demonstrations. They have the best gardens, get the best results from their bees, have the most productive hens, receive the most milk from their cows and show their fellow peasants how to adopt the same improved methods. They also lead in the formation of cooperative organizations and of all cultural societies and dissipate the aversion which the peasants tend to feel toward agricultural books and farm agents with white collars. "As nice as the pope's house" has come to be a proverb, nor is the teacher's inferior and these two little agricultural plants have influenced many villages.

All this does not mean, of course, that the Bulgarian village is yet emancipated or that the peasants live as human beings ought to live. There are still 450,000 primitive wooden plows in constant use, much of the ground is only shallowly scratched and production continues to be comparatively low. But a great deal has been accomplished and the work has but just started. The crusade has only begun to move at full tilt. Only now is the whole intelligentsia of the land becoming convinced that Bulgaria's supreme need is for an elevated peasantry. Bulgaria is still far behind Denmark and Holland but she is moving toward them. She has definitely and resolutely chosen a very high ideal, and is working unwearyingly to reach it. In all the clatter, clash, brilliance and glare of modern life, among the parades, celebrations and adventurous triumphs, the humbler but most essential creators are often overlooked; among whom are agricultural reformers. Very few servants of humanity any place in the world are doing more valiant and heroic work than the Bulgarian experts who, situated in dreary villages amid rough toilers, have to overcome pests, droughts, devastating hails and floods. Working with dull people who through centuries of oppression acquired a suspicion for diplomaed officials, they are lifting a nation from 'too close companionship with animals and manure piles, up into a healthier, more human atmosphere. By introducing plows and threshers, pedigreed bulls and boars, good seed discovered in a thousand patient tests, fertilizer vats and chicken coops, laboratories and movie machines, cooperative societies and reading rooms, agrarian banks and farm clubs, they are steadily conducting what was a century ago Europe's most completely submerged nation out of the blighting rut of oriental lethargy up to a plane where in a few decades they may take a place beside Switzerland and Denmark, lands in which even villagers live as cultured and economically assured human beings, enjoying all the spiritual blessings the century has to offer.

* * *

The principal agricultural products of Bulgaria are cereals, tobacco, fruit and rose oil. Approximately 6,000,000 acres of land are planted to grain each year, yielding 1,400,000 tons of wheat, 234,000 of rye, 343,000 of barley and 465,000 of corn. Both the yield and the amount of land planted are somewhat less than formerly. This unexpected reduction, in spite of Bulgaria's constantly growing population, is due to two causes: first, the country lost some of its best agricultural land during the Balkan wars and the World War so it has not as many fields to plant to grain as before. 170,000 Bulgarian peasants occupying a former Bulgarian province, the Dobroudja, known as the "little America of the Balkans", are now raising wheat for Rumania. This is practically the only area south of the Danube with fields large enough to permit the use of tractors, gangplows and binders.

But there is also another reason why the Bulgarian peasants are giving less attention to their grain fields and more to orchards, gardens and tobacco. It is that the United States, Canada, South America and Australia, by their vast production of cereals which they export very cheaply to Europe, have made the raising o grain in the Balkans unprofitable. The Bulgarian villager cultivating ten acres of land divided into half a dozen widely -scattered fields, planting his wheat by hand and cutting it with a garden sickle, cannot compete with the gang plow and the gigantic, tireless reaper-threshers striding across the vast American plains. These overseas farmers are like armored knights on fire-belching tanks charging barefooted, openshirted peasants whose heaviest weapon is a homemade hoe and naturally the Americans are winning the victory. The good League of Nations has interfered and is trying to arrange an economic armistice, but the farmers of the new world will not sign up. So the Bulgarian peasants are relinquishing the sickle battle line and opening a new front where the clumsy gang plows and giant reapers will not be able to operate. They are beginning to raise more profitable farm products, which require increased toil but bring in larger returns.

The principal new crop is tobacco. And here Bulgaria has been somewhat favored by political events, for although she lost much excellent wheat land she gained several territories very suitable for the raising of tobacco. They are situated in the southern and southwestern part of the country where small, sunny valleys abound amid high, rugged mountains. Here some of Europe's best tobacco is grown, rivaling that of Turkey, Egypt and Greece. Because of relentless competition Bulgaria is not always able to place her produce in the foreign markets and in consequence there is great price fluctuation which has discouraged

the peasants and prevents them from raising as much as they might. The amount of land sown to tobacco during recent years is as follows: in 1912, 22,145 acres; in 1914, 47,077 acres; in 1918, 100,738 acres; in 1923, 140,622 acres and in 1928, 75,090 acres. The annual' productions have been: in 1912, 5,772 tons; in 1918, 20,000 tons; in 1923,52,216 tons and in 1928, 18,000 tons. In Bulgaria itself excellent tobacco is sold very cheaply.

Preparing tobacco to dry

The people smoke it almost exclusively in the form of cigarets, which as a rule they do not roll themselves. A box of 100 cigarets of very good quality costs 36 cents. 24 of which go to the state in the form of revenue taxes and 12 to the producer. One may be surprised to learn that in a land where good cigarets are sold three for a penny very few women smoke. Women also drink very little of the excellent Bulgarian wine that is often sold for ten cents a quart.

Other products to which Bulgaria is giving attention are cotton, silk cocoons, practically all of which are sold abroad, oil bearing seeds, vegetables, fruits, and wine. She is now arranging the export of these products so that more and more of her fine tomatoes and delicious grapes as well as of her beans, rich in fat, are being marketed in the cities of Europe.

The state has arranged for the regular circulation of international chicken expresses from Bulgaria to Central Europe and if some day you should be travelling from London to Constantinople on one of Europe's finest trains, the Orient Express, you might meet at some station a giant engine pulling a long line of special cars full of very noisy passengers riding berth above berth and craning their necks far out of the windows utterly regardless of warnings, rules of etiquette and flying cinders, determined at all risks to see the sights. Those are the Bulgarian chickens taking their first trip to Europe. They are mostly roosters and retired old biddies for their more thrifty relatives are left back home to lay eggs, which are sent by millions up the Danube river, forming Bulgaria's third largest item of export. These eggs have done more than any other agricultural product except tobacco to keep Bulgaria's commercial account balanced and her money stable. The peasant women's little flock of chickens, which during most of the year have to scratch around and make their own living, are really one of the corner stones of the country's economic structure and by no means as fidgety a stone as you might surmise.

* * *

The most interesting and alluring of all Bulgaria's products, however, is not her mild, dreamy tobacco, nor her large, pink grapes, nor her flaming strawberries but her soft, golden colored rose oil. This is her most famous creation, the chief contribution of these stolid, quiet peasants to the brightness, brilliance and gaiety of the world's cities. Few of the dashing and beautiful women of the commanding salons in the chief metropolises of the proud western lands know that the basal element in their most exquisite perfumes and finest soaps and choicest lotions is the oil distilled from whitish-pink Bulgarian roses that are tended by darkly clad, moccasined peasants, gathered by barefooted girls wearing white headcloths and carried in huge gunny sacks fastened onto the backs of small, shaggy donkeys to many little stills where they are dumped into boiling retorts resembling Kansas milk cans crowned with large storks' heads having boundlessly long bills.

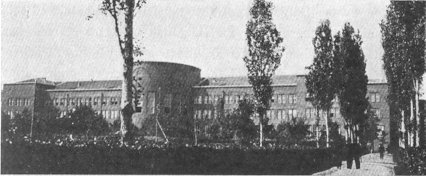

Picking roses for rose oil

Seventy five percent of the rose oil used in the world comes from Bulgaria. It is produced in the so called Rose Valley, which lies on the sunny side of the Balkan range, being formed by that mountain chain and a neighboring parallel ridge of hills known as "Sredna Gora" or the Middle Mountains. Many of the chief distilleries are near Shipka Pass and not a few of them are owned by Mr. Shipkoff, which is exactly as it should be, for Shipka means wild rose and it was in this wild rose district that the whole industry began. That is, began for Bulgaria or was introduced into Bulgaria.

It had long thrived in the Orient, the people of which from time immemorial have been fond of roses. On all great occasions when Oriental kings or queens vied with one another in the display of extravagance, roses played an important role along with pearls and gold and canary birds' livers. Many may remember Weigall's description of the rose carpet which the fascinating and daring Cleopatra once spread for Antony, a guest whose goodwill she was very eager to capture. He says:

"Determined to win the fickle Antony back to her cause and that of her son, Cleopatra set sail from Alexandria, and passing between Cyprus and the coast of Syria, at length one morning entered the mouth of the Cydnus in Cilicia, and made her way up to the river in the shadow of the wooded flopes of the Taurus mountains.Across the water in which the last light of the sunset was reflected, the royal galley was rowed by banks of silver-mounted oars, the great purple sails hanging idly in the still air of evening. The vessel was steered by two oar-like rudders, controlled by helmsmen who stood in the stern of the ship under a shelter constructed in the form of an enormous elephant's head of shining gold, the trunk raised aloft. Around the helmsmen a number of beautiful slave-women were grouped in the guise of sea-nymphs '"and graces; and near them a company of musicians played a melody on their flutes, pipes and harps, for which the slow-moving oars seemed to beat the time. Cleopatra herself, decked in the loose, shimmering robes of the goddess Venus, lay under an awning bespangled with gold, while boys dressed as Cupids stood on either side of her couch, fanning her with the coloured ostrich plumes of the Egyptian court. Before the royal canopy brazen censers stood upon delicate pedestals, sending forth fragrant clouds of exquisitely prepared Egyptian incense, the marvellous odour of which was wafted to the shore ere yet the vessel had come to its moorings.

"At last, as the light of day began to fade, the royal galley was moored to the crowded quay, and Antony stepped on board, followed by the chief officers of his staff and by the local celebrities of Tarsus. His meeting with the queen appears to have been of the, most cordial nature, for the manner of her approach must have made it impossible for him at that moment to censure her conduct. Moreover, the splendid allurements of the scene in which they met, the enchantment of the twilight, the enticement of her beauty, the delicacy of the music, blending with the ripple of the Water, the intoxication of the incense and the priceless perfumes, must have stirred his imagination and driven from his mind all thought of reproach. Nor could he have found much opportunity for serious conversation with her, for presently the company was led down to the banqueting saloon where a dinner of the utmost magnificence was served. Twelve triple couches, covered with embroideries and furnished with cushions, were set around the room, before each of which stood a table whereon rested golden dishes inlaid with precious stones, and drinking goblets of exquisite workmanship. The walls of the saloon were hung with embroideries worked in purple and gold, and the floor was strewn with flowers. Antony could not refrain from exclaiming at the splendour of the entertainment, whereupon Cleopatra declared that it was not worthy of comment; and there and then, she made him a present of everything used at the banquet — dishes, drinking vessels, couches, embroideries, and all else in the saloon.

"On the following night, Cleopatra visited Tarsus and entertained the Roman officers at another banquet; and on this occasion she caused the floor of the saloon to be strewn with roses to the depth of nearly two feet, the floweis being held in a solid formation by nets which were tightly spread over them and fastened to the surrounding walls, the guests thus walking to their couches upon a perfumed mattress of blooms, the cost of which, for the one room, was some 250 English pounds."

Thus Cleopatra played the game of Empire on a carpet of roses.

And on another occasion, another monarch, an Indian Prince also used roses in his politics. Wishing to beguile his somewhat pensive bride who felt that the rather common features of her lord were an insufficient recompense for her beauty, he placed her in a garden full of magic delights through which he sent little streams of rose water obtained by boiling tons of roses in great kettles. This little flood of fluid fragrance after gracefully spouting from a cluster of fountains, in whose fine sprays jetting lamps drew dancing rainbows, flowed slowly through the park in the cool of the evening into a hidden pool whence silent, unseen slaves pumped it back to the source to be used again. But even this did not bring satisfaction and sleep to the sulking beauty, so she stayed awake until the sun came up and took the place of the rainbow lights, at which time her downcast eyes, pining over a wasted night, spied tiny strings of golden beads, strewed along the sluggish stream of cold rose water. This was rose oil or essence of rose or attar of rose. In spite of her indisposition the princess reported her discovery to her magnanimous husband and thus brought an inestimable boon to spirited women who wish to enhance captivating forms with alluring aromas. A cheaper and simpler method was found for distilling the oil than running it through a cooling garden past a pouting bride and since then rose oil has been in much esteem.

In the eighteenth century when the whole of Bulgaria formed part of the Turkish Empire, a Turkish merchant familiar with the rose gardens in Asia passed in a carriage drawn by bead-bedecked, bell-jangling, little horses along the main highway that leads over the Balkan Mountains toward Rumania and when he came into the vicinity of the Wild Rose Pass, he was struck by the extraordinary abundance of the flowers and their extreme fragrance. They impressed him as being very similar to the oil-bearing roses on the other side of the Bosporus while the climatic and soil conditions about Shipka seemed to him ideal for a rose industry. So he induced some of the Turks living in the valley to set out roses and start a little distillery. The results proved very favorable and for many years this little valley has been giving humanity most of its rose oil.

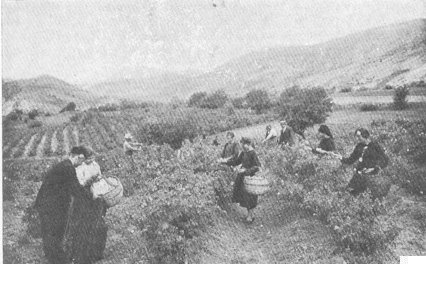

A primitive rose oil distillery

In Bulgaria 12,500 acres of land are devoted to rose culture. The gardens or fields are usually small and the rose bushes are planted in rows about a yard apart. They are allowed to grow nearly as high as an adult's shoulders and although carefully trimmed they bush out so as nearly to hide the ground. The flowers which belong to the varieties Rosa Damascaena and Rosa Alba, are small and unpretentious and are always picked before they open. The gathering time is very early in the morning. As soon as it is light enough to see, girls pull the blossoms from the bushes and put them into baskets from which they are poured into sacks and taken to the distilleries with the dew still on them. If exposed to the hot rays of the sun, they give less oil and of an inferior quality.

The old fashioned distilleries were very simple, easy to make and easy to manage. Rows of big, upright, closed kettles containing water were placed on bricks over a fire. The roses were dumped into the water and boiled. The steam passed through the head of the kettle and was conducted through long pipes lying in cool, running water. As it distilled, little yellowish green drops appeared on top, which were drained off into small receptacles. This was the rose oil and when it cooled, it congealed and assumed the appearance of salve or vaseline. Many of these primitive stills still exist, but more and more they are being replaced by factories.

In 1924, 6,000 tons of rose blossoms yielded two tons of essence, which

means that a ton of flowers produces much less than a pound of pure oil.

The boiled rose leaves are thrown away, as well as most of the rose water,

in spite of the fact that it is very fragrant. Rose oil costs three hundred

and fifty dollars a pound. Bulgaria produces approximately 6,000 pounds

yearly, sending most of it to France and the United States. Much of the

oil is put up in tiny bottles shaped like acorns which are dosed with a

metal cap that screws on very tightly since the essence evaporates easily.

One of Bulgaria's most [famous stories, inimitably told by her Mark Twain,

is about the peasant Bai Ganyou, who filled his saddle bags with tiny bottles

of rose oil and went to Europe to sell them. The best of all the unrivaled

preserves prepared by the Bulgarian women is rose-leaf "sladko". It is

made throughout the country in a multitude of homes and not merely in the

rose valley. Puddings in Bulgaria are often flavored with rose water.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]