The workshop of the "Cooperative Graphic", whose proprietors are making the cuts for this book

CHAPTER XX

And that's that

Well, thank goodness, this is finished! Lots of goodness on the part of lots of people! First, I am grateful to Mary Gall Markham who came from Geneva to Sofia and spent a very busy Easter holiday examining my manuscript and proof-reading the first hundred of these pages, as they came off the press. Of course, I dare not say that she detected all the misspelt words, but she unearthed a surprisingly large number. And she did valiant service, also, in reducing the interminably long sentences to approximate intelligibility. If, in spite of that, you got dazed in trying to wander through some of them, imagine what they must have been in the beginning.

I also thank Mrs. Alma S. Woodruff, an American educator in Sofia, for adding one more task to the 791 she already has by offering to read the proofs of a number of forms which came off the press while I was out of Bulgaria. Those sections after the hundredth page which have the fewest mistakes are the ones she did.

I am also very appreciative of the help given me by Mr. Assen Nicoloff, a teacher in the American College at Sofia, who supplemented my hands and feet and eyes in innumerable ways during the busy month we were getting the book out, doing everything from reading proof to chasing care-free celelebrities to their lairs in order to get their photographs.

The workshop of the "Cooperative Graphic", whose proprietors

are making the cuts for this book

My very special thanks and appreciation go to the Bulgarian artists, who gave me invaluable assistance in presenting Bulgaria to the readers of this book. They freely placed their work at my disposal and a number of them went to a great deal of trouble to help me gather material. The unflagging devotion of many of them to the highest ideals of beauty and masterly workmanship, in spite of the extremely difficult circumstances in which they are placed, has won my warmest admiration. It has been a great pleasure to me to help bring a number of their productions before the attention of foreign readers. I, of course, have used their pictures not primarily to show the artists off but to show off Bulgaria. I have attempted no exhibition of art but only of artistic features of Bulgarian life. It is a case of art not for art's sake but for life's sake. This book is about a nation and not about individuals and I have preferred to use an artist's talent to show what a Bulgarian plowman is like rather than to use a plowman to show how well a certain individual paints. Bulgarian artistic creations deserve a separate book.

I am, of course, very grateful to the men who made the 200 cuts for printing these illustrations. There were seven of them, namely the members of the "Zincographic Cooperative, GRAPHIC", and they may be pointed out as excellent examples of Bulgarian artisans. They own their own shop and do most of the work in it, spending much more time at their daily toil than their ten employees, because labor laws restrict the hours of workers to eight hours a day. This cooperative was founded in 1925 and has a capital of 3,000 dollars, contributed by the members themselves, who learned the trade as workers in other zincograph concerns. Each one of the seven has his special task but they all share profits and losses equally. There are more profits than losses since the firm has as much work as it can possibly dispose of; yet, because of heavy competition, the average monthly income of each of the cooperators does not, I surmise, exceed 50 dollars. Nevertheless, every one has a small house on the edge of town, sends his children regularly to school, belongs to a number of societies and, in spite of his long hours of work, has a remarkable knowledge of all movements and persons of importance in the country.

They appear to be reliable, work together very harmoniously and fill their orders with much punctuality. In their social and political conceptions they are probably found near the fringe of the left center, where pink begins to turn into red. They cherish a rather glowing sympathy for reformers but abhor the uncertainties and excesses of Communism. It is this type of progressive, hard working, independent small proprietors that have given virility and tenacity to the Bulgarian nation. They are as good as the next ones and have as fair a chance as anybody to get ahead. That is Bulgaria.

The typesetters of the printing office "Stopansko Razvitiye'

at work

The printers who set up this book deserve nothing but gratitude. The concern for which they work is called "Stopansko Razvitiye". It is housed in a two story building, with the cases containing letters upstairs and the machines for printing the forms downstairs. These 400 pages were all set up by hand, as agile workers picked letters, molded on the end of tiny rectangular bars of metal, from high placed trays, containing 135 little compartments each, and placed them one snugly beside the other, in narrow, shallow, three-sided, brass "compasses", which they held in their left hands. All of these half million letters were put in the places where you have found them by three men and a woman, not one of whom can read a single line of English. You may realize what a difficult task it has been if you imagine yourself setting up 100 pages of the following type:

Господъ е пастиръ мой ; н![]() ма да

остана въ нужда. На зелени пасбища ме успокоява ; при тихи води ме завожда.

Освежава душата ми ; води ме презъ прави п

ма да

остана въ нужда. На зелени пасбища ме успокоява ; при тихи води ме завожда.

Освежава душата ми ; води ме презъ прави п![]() теки

заради името си. Да! и въ долината на мрачната с

теки

заради името си. Да! и въ долината на мрачната с![]() нка

ако ходя, н

нка

ако ходя, н![]() ма да се уплаша отъ зло.

ма да се уплаша отъ зло.

That was the first four verses of the Twenty-third Psalm in Bulgarian.

The presses and their masters

These printers have a 48 hours week. They begin work at eight in the morning, have two hours off for dinner and quit very promptly at six. On Saturdays they have one hour for dinner and quit at five. The quarters in which they work, though not new, are light and airy and kept very clean. There is an extremely small labor turnover, most of the employees having been with the company for many years. The boy for doing the odd jobs, who I suppose is "the printers' devil", gets five dollars a month, the head type-setter forty dollars and the head machinist a little less. All of them have the benefit of sick and unemployment insurance, to which they and the proprietor contribute monthly premiums. Rules defining the rights of the workers are posted in the shop and government inspectors come around frequently to see that they are enforced. At least they are supposed to. I have the impression that it is not much fun to be a printer, but these workers, in spite of their small wages, are not much worse off in their small shops than the slaves of the ruthless machines in the giant factories of the western world. They enjoy more holidays than their comrades in America and England. This book was on the press six weeks and in that time there were five full holidays besides the Sundays. Work on holidays and Sundays is strictly forbidden.

The girls who fold and assemble the forms

I should think that printers and writers would be in bitter conflict with each other for I suppose that most writers are very much inclined to alter their text after it is set up and even after it is tightly screwed into the form — in fact until it actually goes under the heartless cylinder and appears black on white to brazenly stare one in the face for ever after. Such alterations must irritate printers exceedingly and I understand that the Bulgarians have a good assortment of colorful words with which to express disapproval, but my printers used none on me, for which I am very grateful, especially since, being often absent from Sofia, I occasionally held up their work. They are not members of labor unions, because most printers' unions were Communistic and have been virtually outlawed.

* * *

This book is a quickly prepared journalistic creation, written on the wing at many different places and times. It is not a reference work nor annual nor study, but a collection of glimpses for people who have not had a chance so much as to glance at Bulgaria. I am not at all proud of that kind of writing nor do I recommend it. I used it because it was that or nothing. The way I earn my daily bread does not permit me to sit long in one place nor to delve deeply and leisurely into the treasures of cool, wise libraries. I wrote some of these chapters in Bucharest, others in Belgrade, several in Geneva, a good many in Sofia and parts of chapters in trains and at railroad stations. In looking over the manuscript later I wondered if those short, choppy sentences, that keep you hopping from one to the other as though you were crossing a muddy street on small slippery stones placed rather close together were written to the tune of jouncing, staccato car wheels and whether those long, long sentences which I cannot get through myself unless I take a strong running start were written in the quiet of a solemn Sofia .night when movement gives way to being and there is no beginning nor end, no long nor short, but just an oriental eternity resting in one place. 1 am sorry that I find no real data to substantiate this alluring theory.

The disjointed way in which I have written has, I see, caused even more repetition than I dared fear but there is no way to disillusion myself about it since a number of these pages seem to take a most impudent delight in thrusting themselves before my eyes and presenting scattered sentences, paragraphs and sentiments that look as much alike as a whole family of twins. In Belgrade on Saturday I seem to have forgotten what I wrote in Bucharest on the proceeding Wednesday.

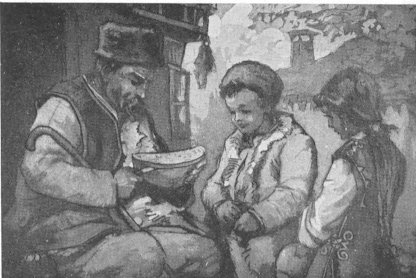

A folk legend illustrated by S. Badjoff

This wonder-child's halo made a wicked Sultan blind

Undoubtedly there are a disappointing number of mistakes in minor details and there are not a few words most ruthlessly chopped in two at the ends of lines, instead of being neatly and properly disjointed as expert proof-readers are able to do it. Such defects inevitably find their way into hasty work. They are the price that must be paid and to apologize for them is more or less of a superfluous affront. One must take his medicine. I had to write and print this on the wing or not at all and I am glad I tried it even though I must say that at the present moment I am tired of the sight of it.

The difficulty which a Balkan correspondent has, in concentrating for a long time on a single task and in doing all the verifying and harmonizing he would like to, is rather dramatically revealed by the fact that, during the short time this book was on the press, governments fell in. Albania, Bulgaria and Rumania, precipitating long and exceedingly important crises in the latter two countries, all of which events were in the news field of the author of this book and required much immediate and continued attention and travel.

You have undoubtedly noticed what quaint habits the Bulgarian quotation marks have. They refuse to look one another in the face. The way we have placed them makes one appear to be chasing the other, but, as the Bulgarians use them, one is perched up in the northeast corner, tail up, while the other is hunched down in the southwest corner, tail down, and they remain there sullenly back to back. Well that is enough of that.

And here is the end ... It is late Saturday night in Sofia. One beautiful spring week is silently flowing into another still more beautiful spring week. An hour or so ago the curtains of the Slate Theater went down on Wagner's opera Tanhдuser, which was excellently rendered, flooding the auditorium with abounding tides of compelling, appealing music and with high, absorbing thoughts. One thousand two hundred well dressed people, who constitute the Bulgarian elite and are trained to comprehend and appreciate the exquisiteness of melody and the imperiousness of sound, went to humble, heavily mortgaged homes of their own, grateful that the choicest treasures of human culture have been brought to their doors and relieved that they can sleep late tomorrow morning since it is Sunday.

A few hours earlier scores, of thousands of men, in many hundreds of stuffy coffee houses and saloons, vehemently excoriated King Boris because he did not solve the recent ministerial crisis by putting their parties into power and throwing the other fellows out. At about the same time on this same Saturday evening many thousands of youth went walking up and down the main streets of the 92 cities and hundreds of large villages, by twos and threes, joshing the girls as they passed, while an equal number of girls, who had put on their brightest clothes and gone out to be joshed showed that they enjoyed it by feigned frowns and half concealed grins.

Dinner time

Etching by P. P. Morozoff

Tomorrow morning the big and little bells will ring in 2,000 churches and heavy, black bearded priests, clothed in long golden robes will stand before gilt eikons of austere saints, will swing their incense lamps and chant soothing hymns in a stately language, which reverent multitudes of peasants end grandmas will listen to with awe and gratitude. In the afternoon there will be football games in all the cities, Sofia playing a championship match with a strong team from Jugoslavia. In the evening great throngs, including ss many school children as dare risk breaking the school laws, will go to the movies to see Charlie Chaplin and Greta Garbo. At the same time that the football games are going on in the cities flaming youth and "little maidens" will gather in 5,000 village squares and, clasping hands or holding one another by the belts, will weave long, sinuous circles, making their rythmic steps keep time to shrill songs or screeching bagpipes. And all day long'the valleys, gorges and mountain sides will echo with heavily shod, bare armed men and women seeking restful weariness amid nature's charms.

But there will still be people left not striving after amusement. They will assemble in halls and coffee houses in order to ease their consciences, find peace for their souls or further some crusade. Some will talk of temperance, others will sing the soothing assuagement of spinach, sauerkraut and similar vegetable dishes; many will plead the cause of peace and not a few will shout of the urgent need of wiping out the pacifists; small groups of undaunted women will appeal for equal rights and a number of tranquil, well fed people will explore rosy theosophic fantasies; while here and there in stormier meetings the shock troops of the political parties will launch their drives toward the ballot boxes in view of the coming elections; vehement men will raise their voices mightily, wave their arms, brandish their fists, shake their formidable mane-like hair or wipe the copious sweat from their bald pates and call upon their listeners to save the country from their rivals, vote for righteousness and bring home the bacon.

Finally, millions of tired children, ardent youth and rather wan and bewildered parents will go to bed in crowded rooms with the windows shut, all trying to believe they have enjoyed the holiday. Then Monday will come and 84,000 officials will take their canes or modest powder cases and go to their offices or class rooms. 700,000 children will wash their faces, eat pieces of bread flushed down by weak tea and trudge to big and little schools, as millions of barefooted, hard-handed peasants color fertile plains with the red and blue and green and orange of gay garments that defy drab toil. Babies will swing under wild pear trees, a myriad wild flowers will bloom, mothers will tote butter and eggs to markets eight miles distant, grinning goats will nibble tender twigs from verdant bushes, grandmas will watch grey cows in greening meadows, scantily clad children with running noses will joyfully chase one another down freshly plowed furrows and mother earth, fragrantly smiling as stolid men and women comb her black hair with wooden plows, will kindly prepare to create them another harvest to tide them over to another spring, which will germinate another harvest — as during 200 generations.

A windmill for grist

Etching by P. P. Morozoff

All this and a host of other things make up Bulgaria — love, fidelity, romance, violets, nightingales, swaddled babies looking like cocoons, inert buffalo, ambitious youth, church bells and flutes, much frustration and a little triumph, a few thrills and lots of duty. And through it all, behind the vehemence, the frothy politicians, the swinging hoes, the causes and crusades, the gloomy skies streaked by scant bars of radiance, -1 see a tenacious nation slowly toiling up, up, up, through long, hard centuries. It often falls, it is thrust back by striving neighbors mounting the same height and is trampled by greater powers, while its own members ruthlessly elbow and jostle one another in the hard ascent. Yet after every fall the nation rises and ever pushes up and up and up. It is today farther from the bottom that it ever was before and moving faster than at any other time toward the bright peak of culture, prosperity and righteousness, which no nation has yet attained. Before it approaches that destination it will have to elevate its peasants and lead them into the estate of fully enfranchized human beings, with ability to acquire and capacities to appreciate the treasures in the common warehouse of humanity. To that end Bulgaria is working. I wish her ever increasing success in her praiseworthy efforts and give my unbounded admiration to every conscientious teacher, priest and farm agent who is devoting his life to the task of making village life better.

A Bulgarian Madonna

By V. Dimitroff - the Maistor

It is they who are first among contemporary Bulgarian heroes, and I pray that the dainty and elusive nymphs who are reputed to dance with such joyous abandon on the greenswards amid the great forests and whose special duty is to bestow verdant crowns, gentle words and soft caresses on worthy patriots — after they're dead — will not fail to recompense the knights of village progress with copious outpourings of their choicest favors.

If such valiant people crave such recompense!

As for me I am sure I would.

But the cocks, who have served as time keepers for scores of generations of clockless Balkan villagers, are now raucously singing their third nocturnal chorus so I know the night is far gone and it is time to quit.

Therefore, as the Bulgarians say, "So long until this time next year!"

THAT'S ALL EXCEPT THE MAPS

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]