CHAPTER XI

Getting into print

B.

Contemporary Novelists

|

|

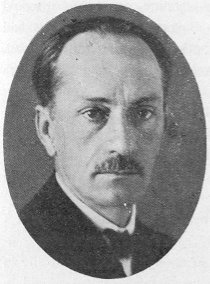

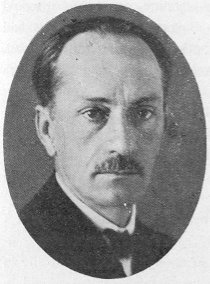

| Dobri Nemiroff, | Anton Strashimiroff,

|

| who is perhaps the leading Bulgarian novelist since the death of Ivan Vazoff. He writes of Bulgarian patriarchal life | whose fiery spirit and feverish pen are occupied chiefly with stories ot rebels and revolutionists, struggle and combat |

|

|

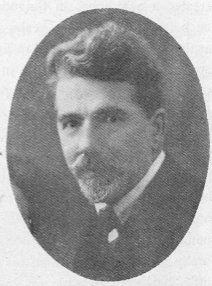

| Stilian Chilingiroff, | Anna Kamenova, |

| novelist, critic and poet, whose tireless pen has won distinction in many fields and left a whole library of interesting books | a critic and writer of outstanding talent, whose excellent stories of Bulgarian women are marked by understanding, sympathy and a very attractive style |

Pencho Slaveikoff, who was born in 1866 and died in 1912, created a new epoch in Bulgarian literature, or perhaps it would be better to say in the realm of Bulgaria's literary ideals and aspirations. Slaveikoff was an European; he was educated abroad, spent a large part of his life in western Europe and wrote much of his best work outside of Bulgaria. His tastes were cosmopolitan, his artistic aspirations as high as those of the world's best writers and his interests as broad as humanity. Pencho's father, who was a contemporary of Christo Boteff and a very famous Bulgarian patriot, endured almost countless hardships because of his political activities and Pencho himself had many noisy antagonists in his fatherland, at the hands of whom he suffered a number of galling humiliations. These bitter experiences naturally tended to strengthen his conviction that the artistic life in little, backward Bulgaria was too meager and limited a field to satisfy his artistic aspirations. In addition there were many upstart, talentless writers of vast pretensions in his country, whose swagger and self-assurance were very repulsive to him. Slaveikoff also had met many gifted artists in foreign lands and was very well acquainted with world literature, as a result of which the exaggerated patriotism of some of his fellow countrymen seemed rather grotesque and vulgar. He was convinced that the art of his newly liberated nation would be stifled and warped unless taken out of the mold of narrow, national interests. He thought that literature should not be the servant of politicians, parties, national celebrations, generals and patriots but a proud and independent mistress living in a tranquil villa somewhat removed from the dusty crossroads of every day Bulgarian life.

So Slaveikoff launched a crusade for a higher kind of art, for a purer form, for grander ideas, for a whiter beauty, for more aristocratic tastes. And, of course, when any one leads a crusade. toward a sacred city he meets enemies in the way with whom he must join furious combat, which Slaveikoff did with a grand good will, directing many of his spears against the national poet, Ivan Vazoff. Vazoff was a rather happy and optimistic man, joyously and exuberantly patriotic; he liked to have children declaim his poems, was pleased when the common people, easily understanding his songs, were moved by them and was gratified to be able to establish intimate and cordial relations with a -nation of forward striving, sincere people even though they were rather crude and simple. It was against this somewhat provincial, homegrown conception of art that Slaveikoff, aided by a number of very valiant and brilliant comrades, hurled his broadsides. He managed his campaigns from the heights of Olympus. He brought his munition from the best literary arsenals of the world. He carried on a "war of liberation", trying to free his people from what he considered paralyzing Balkan standards and to lead them up onto mounts of transfiguration, up to classical heights where beauty, rhythm and perfect form do not smell of the village barn nor wear the garish masques of peasant revellers.

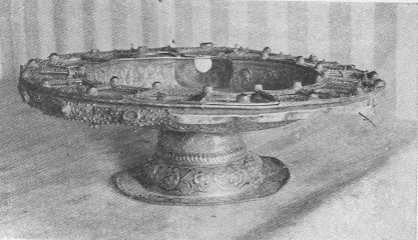

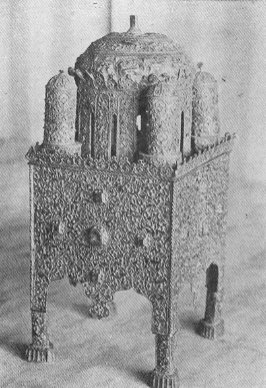

Gold fruit bowl such as craftsmen still hammer out

Slaveikoff was the Napoleon of Bulgarian literature in that he was proudly and imperiously determined to make all European capitals his own, and indeed he lived in many of them.

He might also be called the Browning of Bulgarian literature in that he wrote somewhat obscurely and deeply. His poems are hot easy to understand. They require thought, careful study and the proper mood. They are cold, filled with profound reflections, philosophical. Many of them are not for common people and Slaveikoff was glad they are not. He did not write down; he demanded that people take the trouble to come up to him if they wanted to understand him. He gave them solid food, served in great silver dishes on a marble table in an austere room. Indeed Slaveikoff's verses and songs may even be said to be of marble. They are rigid and cold and chiseled with great care; they are very deliberately planned and exquisitely wrought. They are model productions at which many generations will gaze in awe and admiration, but they lack the fire of Boteff and the captivating intimacy of Vazoff. Boteff wrote songs in order to make rebels, and Vazoff in order to make his peasant neighbors love and adore the rebels, but Slaveikoff wrote in order to show his naive countrymen what a model song is like as well as to leave in them an exalted, classical emotion. The writers before Slaveikoff made their readers intenser, more human. He believed in plain living and high thinking, but especially in high thinking. All Bulgarians believe in plain living.

And he was Herculean in his onslaughts. His attacks were furious, simply crushing his opponents. For he was a Goliath among Bulgarian writers. He was the most brilliant, with a knowledge and erudition greater than that of all the others put together/. His pretensions to supremacy were well founded. He really had won a position from which it was easy to attack, so his charges against his provincial colleagues were overwhelming. He called them "bean eaters", which might be better translated "rubes" or "clodhoppers". He cherished a furious disdain for them and thought they ought to stick to their hoes and leave pens alone. If they consented to do that he was glad to sing of them and their fellow peasants in classic fashion.

And indeed it was of the Bulgarian peasants that Slaveikoff did most of his singing. He was proud of his country, people and language. Almost everything he wrote was in Bulgarian. He felt himself a missionary to the "clodhoppers" and spent most of his energies in the struggle to transform them. But all that on his own terms, in his own Olympian way. He taught them from his high throne, using his sceptre rather freely. It seems to me that he had too little patience with his people; he expected too much from them; he was too implacable. He was indeed a citizen of the world but how could his fellow countrymen, who had spent all their lives in little towns and villages, suddenly rise above the tastes and habits of their provinces and neighborhoods? Nations cannot be made over so easily and a warmer, more forbearing love may transform "clodhoppers" faster than fierce lectures from proud city cousins. But in any case it is Sloveikoff's glory that he and his comrades have given to Bulgaria a higher artistic ideal which is becoming more and more dominant.

Many of Slaveikoff's best poems are inspired by classical figures of fact and legend. He was very fond of Heine. He has left a poem on Shelly entitled "Heart of Hearts". He has another on Beethoven, several dedicated to Goethe, one to Nietche and one is about Prometheus. He was greatly influenced and inspired by classic Greek literature and had unbounded admiration for Homer. One of his best poems is entitled Michael Angelo. Others are called "Truth", "Life", "Death", "Beauty", "Grief", and a whole series of them is about a group of imaginary poets. Many of them tend to be abstract; they have an uplifting purpose and deal chiefly with thoughts and spiritual forces. Slaveikoff does not describe so much the feats of his heroes as their love and fire, the will, force of character and invincible spiritual ideals which they embody. It was this that Slaveikoff was always looking for, namely the spiritual qualities of superior men. Such were the personalities whom he admired and he wished to pass this admiration on to his people. He was under the spell of inexorable standards, bound by the imperiousness of perfection and he wanted all other Bulgarian writers to accept allegiance to these same despots.

This does not mean that Slaveikoff wrote no lighter, more colorful songs.

A fairly large number of his productions are lyrical. Some of them have

a musical "catchy" lilt and many contain deftly drawn pictures, but the

greater part are serious, sad and sombre with a chaste and stately form

that adds to their alluring gloom. These poems, as much of Slaveikoff's

work, are highly individualistic and often treat of graves, death, sorrow

and missed opportunities. He has often been accused of being a melancholy

poet but since the Slavic soul likes to enshroud its smiles with sighs

these are among the most popular of Slaveikoff's songs. He writes of true

love frustrated but not quenched, of aspirations thwarted but not relinquished

and his tone is so exalted and refined that these accounts of village episodes

make one think of classic Greek drama or of religious hymns. The gods and

muses seem to hover closely about Slaveikoff's songs. He himself calls

some of them psalms and that characterization reveals his ideals. His dirge

over his own approaching death is considered by some critics to be the

finest poem in the Bulgarian language.

|

|

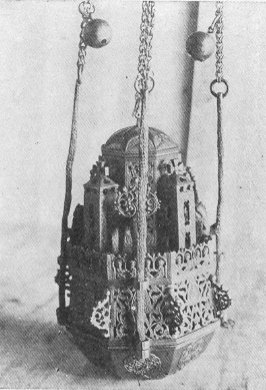

| An incense lamp | A treasure box |

Slaveikoff's most important work is his long "Kurvava Pesen" or "Song of Blood", which was practically the last thing he wrote. It consists of a prologue- and nine songs and is divided into three parts covering eighty pages. It is a description of the struggle of the Bulgarian people for liberation from the Turks and records in much detail the formation of rebel bands, their encounters with the Turkish armies and their complete defeat. Yet it is far more than a poetical account of heroic deeds. Slaveikoff was never satisfied with mere acts. He always wanted to join them up with some great spiritual power and invest them with special meaning. And in this epic song, the crown of all Slaveikoff's work, the main hero is the mountain itself, the Balkan Mountains. This is highly characteristic of the poet and also in perfect keeping with tradition, for the Balkans and rebel life in the woods have always exercised a magic spell upon the Bulgarian people. The Balkans are enshrouded with a mystery and a power, a sympathy and a charm which endow them with a personality and make them seem divinely human to the people living about them. For centuries the Balkans were the friends and champions of the oppressed Bulgarians. This strange, romantic relation afforded Slaveikoff a perfect hero for his song. The principal characters are Spirit and Deed, The song shows how Spirit finally triumphed even though Deed was often thwarted.

This epic has not the captivating swing nor the easy charm of Vazoff's series of songs about the Bulgarian revolutionary heroes. It is somewhat more symbolic and more difficult to read. It is perhaps more finished and probably more carefully worked out; it is a profounder, more artistic creation. It may be compared to the great poem "The Woodland Wreath", written by the Montenegran Prince Bishop, P. P. Nyegosh, in 1847, which is certainly one of the finest poetical creations of any of the Balkan peoples. Slaveikoff's "Song of Blood" is one of the things that has given Bulgarian literature a place among the leading civilized peoples and was one of the productions that once enabled its author to dare to consider himself a candidate for the Nobel Prize.

Slaveikoffs influence has been on the whole very useful. Though he was too drastic and somewhat too highbrowed and though he failed to introduce enough warmth, color and pulsating life into his poems, nevertheless he forced upon his people new standards that are raising Bulgarian literary productions onto a higher level. Of course, guide posts and measuring rods will not enable uninspired scribblers to write great songs but they certainly do help the gifted and inspired to write better songs. It is very plain that mere imitation is folly and that any literature in Bulgaria that completely separates itself from Bulgarian soil is doomed to complete sterility, but by employing universal norms and models and by working with vital, breathing, passionate, aspiring, dramatic human material which Bulgaria offers and of which its writers form a part they will be able to produce better songs and stories than their fathers did and it is Slaveikoff who more than any one helped them to find this better way.

Outstanding Short Story

Writers

|

|

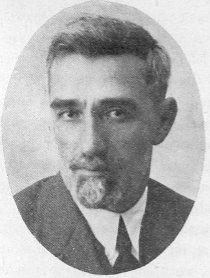

| Elin Pelin | Iordan Iovkoff |

| whose realistic, accurate, concise portrayal of village life secured him the place of Bulgaria's first story teller for many years | who writes of hopes and aspirations. The clearness of his style and vivid humanness of his narrative have placed him at the head of the best |

|

|

| Angel Karaliicheff | Fannie Popova-Moutafova |

| most promising young writer with style and diction very close to that of the best folk creations | whose long historical novel and collections of short stories are graphic, dramatic and full of pity for thwarted people |

* * *

One of his chief comrades, and in some respects even his chief, was Dr. K. Krusteff, who for more than a decade was Bulgaria's leading literary critic and for seventeen years the editor of "Thought" (Misel), the most important Bulgarian literary magazine, in which many of Slaveikoff's best works first appeared.

Another member of this group was the gifted prose writer, Peiu Todoroff, who wrote a number of the most perfectly constructed short stories relating to peasants, shepherds and little people that have yet appeared in Bulgaria. He deals chiefly with what these characters believe or have heard or seem to be or with the way in which they are driven on by inexorable fate. His writings are rather mysterious, symbolic and obscure. He seems at times to be straining for effect, to be trying too hard for originality, to be too intent on making plain and simple things seem cosmic and spooky. Yet his diction is beautiful, his sequence of words in many cases is more musical and captivating than the best of songs and his pictures are extremely impressive. His style serves as a model for many contemporary Bulgarian short story writers, practically none of whom has succeeded in equaling him, which-is probably a good thing. Too many Todoroffs would be a misfortune. His stories are marvelously polished gems but too many gems repel and the purer they are the colder they seem.

Aleko Constantinoff, a politician and journalist, who wrote at the same time as Todoroff, was a brilliant and facile author.

The portraits on the opposite page are by Boris Gheorgieff and the foto of Dora Gabe by B. Karastoyanoff.

A Page of Poets

|

|

| Teodor Trayanoff | Ludmil Stoyanoff |

| an active dynamic singer whom a critic calls "the prophet of his people whose faith is leading them to brighter days". Style more European than Bulgarian | poet, essayist and critic as well as fearless fighter for more justice and equality in social relations. His verses are marked by the perfection of their form |

|

|

| Emmanuel Pope Dimitroff | Dora Gabe |

| called by one critic "the greatest and most inspired lyric poet of Bulgaria in whose songs flows a living stream of mysticism, bearing waves of celestial music" | a singer of sad, appealing songs, filled with yearning and noble resignation, and the author of fascinating half-real, half-dream stories for children |

He was the creator of the Bulgarian "Babbitt", who is popularly known as "Bai Ganyou" or "Uncle Ganyou". Mr. Constantinoff, or Aleko as most Bulgarians affectionately call him, had a very intimate knowledge of the traits and qualities of "Uncle Ganyou" and has described the adventures of this rather typical, unsophisticated and more or less unbathed Bulgarian in a number of fascinating books of satire and humor that have become classic. The verve, guilelessness and pat characterizations of these hasty journalistic sketches have won for their popular arid beloved author a place among the best Bulgarian prose writers. His principal works are "To Chicago and Back" and "Uncle Ganyou".

* * *

Elin Pelin, whose real name is Dimiter Ivanoff, has written some of Bulgaria's best short stories of village life. He is in every respect a realist but has tinged his realism with a great deal of sympathy and tolerance. He makes no attempt to gloss over faults and unsparingly portrays the avarice, pettiness, venality, superstition, drunkenness and brutality, which prevail among the peasants. He knows how limited their minds are, how vulgar are many of their tastes and how violently they quarrel over trifling causes and he relentlessly describes all these things. Yet he also appreciates the love whim peasants have for land, for their fields and growing crops, for domestic animals, children, and homespun, gay clothes; he is acquainted with their fears and their taboos has observed how rigidly they are controlled by inherited customs and by their elders, how passionately their youth give themselves to romantic love, how fiercely they take vengeance, how heroically at times they sacrifice. He also knows how mystically their work, holidays, business and games are bound up with the seasons, the elements, mountains, forests, great trees, storms, droughts, songs and traditions. And in graphic, concise and fluid language he makes stories of these things. He brings the reader very close to the lives of the peasant masses and inspires him with pity and sympathy for them. He is not a patriot as Vazoff nor a highbrow searching for a classic style as Slaveikoff. He is profoundly interested in the thoughts and fears, the work and play, the beliefs and hopes of the human beings who live in villages and constitute most of the inhabitants of Bulgaria and he narrates the little episodes in their life histories in a manner that almost no other Bulgarian story teller has surpassed. A few of his stories have been translated into English.

However, Elin Pelin has long ceased to write, even though he is but little more than 50 years old, so other masters have replaced him in the field of short stories, of which the chief is Iordan Iovkoff. He is the best story teller at present in Bulgaria. Iovkoff's productions are characterized by a sympathetic understanding of the folks he writes about. He does not, to be sure, idealize nor extol them. But he appears to like people. He doesn't find pleasure in bawling them out. He is kind and gentle with them. He looks for the good in them. His job is, of course, telling stories but he tends to look for savory things to tell stories about, such as sacrifice, love, bravery, daring, devotion. This does not mean that his narratives are dull or banal. On the contrary, they are very dramatic and moving, human and appealing. They draw the reader into the action and inspire in him pity, sympathy or admiration. They are not so brutal and hard as some of Elin Pelin's nor so cynical as those of many contemporary authors, nor so revolting as some Slav novelists like to write. They are very graphic and vivid accounts of the struggles and conflicts of little people trying to get along in a hard world. Iovkoff leaves the reader with an increased affection for the Bulgarians, although never for a moment does he toot them or carry on a propaganda in their favor.

Not far behind him is a young writer, Angel Karaliicheff, whose short stories appear frequently in the best Bulgarian literary publication, "Zlatorog". Karaliicheff's power is due to his masterly diction, the vivid interest which he always sustains and the almost magical suggestiveness of his style. He leaves many things only partly said. Every sentence seems to carry a host of implications; each tale seems to be accompanied by many other untold ones. Every word this young writer uses seems to be precisely for a romance, every gesture seems to half reveal some intriguing mystery. It is as though you were passing along a very beautiful road from which a large number of almost equally beautiful paths branch off. The existence of those paths may not actually make your road much more picturesque but it certainly adds much charm and interest to your walk. Of course this complicated style tends to check the movement of Karaliicheff's stories but he uses it very wisely, going directly to the end he is pursuing and shunning the alluring by-paths he creates, so his stories are concise, dramatic, well balanced and unified.

* * *

Bulgaria has a number of able novelists who of late have been rather surprisingly productive. Perhaps the foremost of them is Dobri Nemiroff, who has written half a dozen novels of which the best is "Brothers". It appeared three years ago and is an impressive description of what went on in a little Bulgarian town before the liberation. Few books give a vivider picture of life as it used to be in thousands of European cities before the arrival of trains, industry, armies and modern states, when taxes were paid in kind, rivers were crossed on improvised ferries, accounts were kept on notched sticks, loans were given without promissory notes and clothes, implements and furniture were made in tiny shops by hand.. This novel has been followed by a second describing Bulgarian life soon after the nation was freed and a third is now ready showing the Bulgarian as he is since being transformed by modern civilization.

Stilyan Chilingiroff, who began life as a shoemaker's apprentice and published his first strory at the age of twenty, has written more than forty books during the thirty years following and now in his fiftieth year is bringing out a large new novel graphically portraying life in a backward Bulgarian village. He has also distinguished himself in the field of poetry, the drama, short stories, history and pedagogy.

The state printing office. Until 1837 there was not a

single printing press allowed in the country

Not less productive is Anton Strashimiroff, one of the most restless, rebellious and untamed of all the Bulgarian writers. In his long literary career, covering more than thirty years, he has published more than two score books and repeatedly travelled throughout the country giving popular lectures. In his views on art as well as on politics he has followed a rather zigzag course but he has usually tried to be a champion of the oppressed. He has wavered from flaming patriotism to communistic internationalism and has passed from the position of a high state functionary to that of an almost open enemy of the state, but at no time has he lost touch with the masses of the people and especially with those who tend toward rebellion. A few years ago, when as a result of acute civil strife a large number of villagers and communists were killed, Strashimiroff was practically the only writer of any standing who lifted his voice in their defence and who attempted to record the tragedies of those hectic days in a novel. Since then he has written two other novels about uprisings and bloody strife, describing among other things the efforts of the Macedonian revolutionists to win freedom for their people. Strashimiroff's style is feverish, jerky, incomplete and not easy to understand. As a lecturer he gets a better hearing than most other literary men. He has the faculty of dramatizing dry facts and of making his opinions seem new, startling and important.

A new novelist of much promise is Mrs. Anna Kamenova Stainova, who writes under the pseudonym of Ann Kam. She has recently published a story entitled "Haritina's Sin", which in a leisurely, delicate and satisfying manner describes the life of the women in a small mountain town, most of the men from which work in foreign lands. No Bulgarian writer has better understood nor more sympathetically and beautifully portrayed the yearnings, loyalties and dreams of lonely women left stranded in obscure and isolated places. She understands their religious feelings, their rigid morality, their unfaltering fidelity, their inflexible adherence to customs, their resignation in the face of fate and their gentleness and sweetness of character. The Bulgarian woman, who is an unusually noble personality, has long been waiting for some novelist to do her justice and it seems possible that that author has been found in Mrs. Kamenova. She is certainly the best woman novelist.

It remains to mention two distinguished poets. The most gifted one after Boteff, Vazoff, and Slaveikoff was P. K. Yavoroff, who lived a stormy, unsettled, dramatic life, like many of his' fellow writers, and finally committed suicide. He was a contemporary of Slaveikoff and had the same views on art, but possessed much more fire, spontaneity and passion. In many respects he resembled the rebel Boteff. In fact, he was for a number of years a revolutionist and wrote poems of much power and beauty regarding the oppressed and downtrodden. Rebellion, however, and sterile denunciation of tyrants offered too limited a field for Yavoroff's artistic inclinations so he poured out his wild and impetuous feelings in dark and dismal songs, springing from his own despair and bewailing the pain, which evil and capricious moments brought him. The form and diction of these verses are of a very high order and they are among the most finished artistic productions in the Bulgarian language. They are concise, balanced, rhythmic, full of striking figures and carefully chosen words that carry new meanings and vague, ominous illusions. There is so much symbolism in Yavoroff's lines that often one cannot be sure what he wishes to say. Perhaps he loved strange figures, captivating sounds, impressive combinations of rich syllables and hazy intimations of catastrophe, agony, and abysmal wretchedness more than plain, clear statements. In any case there is fire, daring, abandon and music in his songs, even if the music is from dungeons, caverns and Gehenna. They sweep dispairing souls out on a vast, enticing ocean where heartless sirens calling to doom sing amid the haze. Despairing souls of a romantic nature like thus to revel in their wretchedness.

A poetess of not less fire and with an equal abandon though with not so great a mastery of words and phrases is Elizabeth Belcheva Bagriana, who is the leading poet writing in Bulgaria at present. Her songs are of an exclusively individualistic nature. For the most part it is her own happy emotions of which she sings. She enjoys nature, feels an affection for her people and is deeply impressed by what is sacred and high and eternal as well as by that which brings grief and deprivation but it is burning, passionate love that gives wings to her best lines, carrying them irresistibly over all obstacles and lifting them to the height of lyrical ecstacy. Many sad and many joyful songs vibrate in Bagriana's heart but only those kindled by love, fresh and boundlessly realized, attain inspired expression.

Another very well known and gifted poetess is Dora Gabe Peneva, who has less fire and abandon than Bagriana but perhaps more delicacy and finish. One of the best of her writings is a little book full of wilful, wistful, childish fantasies and dreams. Of late she has been devoting most of her talent to the creation of an artistic literature for Bulgarian children.

* * *

As one takes a cursory parting view of Bulgaria's literature he can not say less than that the nation has done very creditably here as in other respects. A society of peasants suddenly delivered from subjection to the worst power that ever dominated any part of Europe has succeeded in forming a fairly stable and democratic government. A once illiterate people has formed the best school system in the Balkans. Likewise a country without any written literary heritage of a stimulating sort, even though greatly engrossed in material struggles, wars and political conflicts has brought into being beautiful poems, choice short stories, impressive novels and promising dramas. Political disasters, crushing defeats in war, repeated national humiliations have tended to clog the springs of artistic inspiration and have left the more sensitive Bulgarians bewildered and despondent. But it is probable that this will cause them to delve deeper into the mines of their own spiritual riches, that it will open their eyes to the sterility of the foolish aping after current rages in the western literary world and that it will enable them to extract from the press of their own sufferings and aspirations the finest vintage they have yet given to the world.

Each year there are published in Bulgaria about 2,800 books of which 2,500 are originals and the rest translations from foreign languages. Generally speaking most of the world's best classics are now available in Bulgarian. Of the original books appearing annually 803 are reference works, 525 belles lettres and 260 on politics and economics.

There are half a dozen large book publishing firms not one of which is flourishing at present. Very few native authors make money on their productions. Not many books rejoice-in more than one edition, usually of about 2,000 copies. A book of 200 pages is sold for about half a dollar. The actual cost of paper and printing' for such a book is about 15 cents a copy.

At present 898 periodical publications are produced in Bulgaria, 500 appearing in Sofia, the capital, and the rest in the provinces. There are three first class monthly literary magazines published in Sofia and half a dozen weekly literary sheets. Generally speaking there is very much more interest in art, music and literature in Sofia than in any American city of the same size. Many more books are read in America but the intelligentsia there is not so passionately taken up with art problems, theories and pretensions as is that of Bulgaria.

Geo Mileff

poet, editor, martyr. He lost an eye in aiding his country

realise its ideals and his life in helping the thwarted masses attain theirs.

He fell victim of the civil strife raging in Bulgaria in 1925

Forty daily newspapers appear regularly in Bulgaria. The principal ones of course are those published in the capital, which are sixteen in number. Five appear in the morning, one at noon and ten in the evening. Most of them contain four large pages and do not carry so very much advertising, for the Bulgarians trade on a very narrow margin and do not like to lavish money on anything which will add to their expenses. Practically the only sensational paper is the "Outro" which comes out in the morning and is the most widely read publication of any sort in the country. The best morning paper is "The Zora", of which 50,000 copies are sold daily. It is well informed, avoids the wildest sensations, carries excellent, concise editorials, has a high sense of newspaper honor, indulges in far too many mother-in-law and extravagant wife jokes and is read by all the serious people in the land. The best newspaper published in the Bulgarian language is "The Mir" appearing in the evening in 18,000 copies. It is serious, fair, conservative, comprehensive and very dry. In all probability it would very soon go broke in America and the fact that it is one of the few self-supporting papers in the country is a daily demonstration of the seriousness of the Bulgarian people and of their desire for unbiased facts and general knowledge.

Most of the evening papers are party organs; practically all of them are subsidized and they are not so very widely read. The largest one is "The Democratichesky Sgovor" an official government daily. "The Slovo" is the bankers' publication and also represents a dominant party. "The Zname" is the Democrats' paper; "The Radical" that of the Radicals; "The Nation" that of the Socialists and "The Echo" that of the camouflaged Communists; a couple of "Independences" identical in form and in the vehemence of. their attacks, represent the two factions of the Liberal Party; the two "Agrarian Banners" are published by factions of the Agrarian League.

The press in Bulgaria is free; it is not controlled by the government nor by capital. Every one in Bulgaria with an idea, a grievance or an itch to write, gathers together a few dollars and starts a paper. If there are a sufficient number of other people who share his views ardently enough to pay a penny a day or week to read them, the paper lives; if not it dies and no one is worse off for the venture. The mortality of newspapers in Bulgaria is terrific. The fact that comparatively poor people can publish papers, pamphlets, periodicals and books greatly adds to the diversity of thought and enables almost everyone to see himself in print. There are few lands in which thoughts and views are more freely expressed.

Not many of the Bulgarian newspapers have staffs of foreign correspondents. Most of them get the larger part of their outside news from the Bulgarian official telegraph agency, from Bucharest by telephone and from foreign newspapers. The front page of most of the papers is devoted to editorials, political news and controversy and the other pages to stories, art criticism, chronicles and news of a lighter variety. Practically every sheet pursues some cause or other besides that of making money and expresses the views of some group. The Bulgarian papers are among the least sensational in the world.

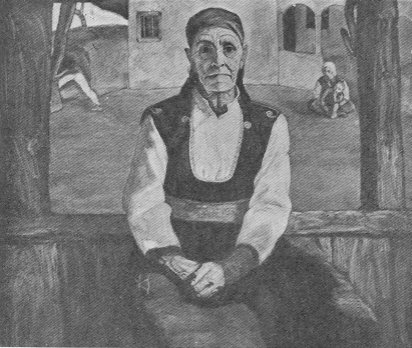

Painting by V. Stoiloff

Grandma goes calling

It may seem rather callous and thoughtless to drag the newspapers into this chapter on literature but it is not nearly so much out of place as one might suppose, for most Bulgarian writers have published their first productions in the papers and weekly magazines and received their first encouragement and stimulus from newspaper men. Bulgaria's newspapers continue to be her chief disseminators of culture.

The oldest existing periodical in Bulgaria is "The Zornitsa", a weekly started in 1876 by American missionaries. It was one of the first papers written in the Bulgarian language and for years had a wider circulation among the Bulgarians than any other publication. In fact in certain provinces the word "Zornitsa" came to be used as a synonym for newspaper. It is now the property of the Bulgarian Evangelical Society, appears regularly, is ably edited and still has many readers. The oldest existing daily paper is "The Mir" which began publication thirty seven years ago.

Up until 1837 there was not a single printing press allowed in the lands

inhabited by Bulgarians. After that a few simple machines were set up and

books and papers began to appear in increasing numbers. Between 1806, when

the first printed Bulgarian book appeared, and the establishment of the

first press 100 books were published. During the following forty years

over 1,500 came out or nearly 40 annually. After the liberation the number

immediately mounted to several hundred annually and is now about 3,000.

The number of newspapers grew in the same way. The first Bulgarian paper

that ever existed appeared in Leipzig, Germany in 1846 and was called "The

Balkan Eagle". It was followed by small transitory sheets published by

exiles, patriots and revolutionists in Smyrna, Constantinople, Belgrade

and Rumania and smuggled into the country. It was only after the War of

Liberation that papers began to appear with regularity in Bulgaria.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]