Meet Bulgaria,

R.H. Markham

CHAPTER X

Getting wise

A.

During the first two decades of the present century Bulgaria had far

more schools in proportion to the number of her inhabitants than any other

Balkan country. After the World War, which brought Jugoslavia and the Greater

Rumania into being, both those states began to open new schools with extraordinary

rapidity, making it possible for most of their young subjects to learn

to read and write. Yet in spite of this most commendable improvement effected

by her neighbors Bulgaria still leads the Balkans in the proportionate

number of children under instruction. In every town and larger Bulgarian

village there is a school; it is usually housed in a first class, modern

building and in most cases conducted by fairly competent teachers. The

tiny mountain settlements, made up of a few huts or of widely scattered

cabins, are without schools of their own, but most of them are within walking

distance of others, situated at convenient points, so that practically

every child in the country 1s able to get an elementary education. As a

matter of fact 90% of the children in Bulgaria of primary school age are

actually studying.

There are in all 6,850 primary schools, including kindergartens, 103

secondary, two normal and scores of professional schools of various sorts

and grades. There is also an excellent modern University with seven branches

or faculties, a state Conservatory of Music and an Art Academy. There are

3,780 university students of which 72% are men and 28% women. The largest

number are enrolled in the law department and after that come literature,

history and philosophy. 22,271 teachers— 10,914 men and 11,357 women —

give training and instruction to the 723,205 children in the primary schools.

For the 20,750 boys and 13,976 girls in the high schools there are 1,781

teachers — 915 men and 866 women. There are 305 professors in the university

of which only two are women. This educational system, ministering daily

to a seventh of the people in the country and using nearly 24,000 specially

trained employees is the largest enterprise of any kind in Bulgaria.

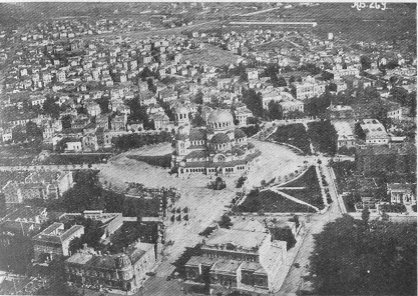

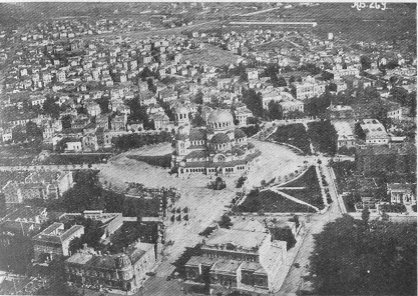

Sofia is the cultural center of Bulgaria and this church

is the cultural center of Sofia. About it are grouped the University, Academy

of Science, Musical Conservatory, Art Academy, Holy Synod, a large high

school, the state printing plant, the National Assembly and the Ethnological

Museum

And its creation is one of the finest achievements of the Bulgarian

people. For it must be remembered that a hundred years ago there was not

a single first class Bulgarian school in existence. The first secular book

to appear in the Bulgarian language came into being at the time of the

American Revolutionary War. It was written by hand and distributed, largely

surreptitiously, among a few enlightened people who had to copy it from

manuscript by hand. In 1806 appeared the first printed book in Bulgaria,

a collection of sermons prepared by the Bishop of Vratsa, who was then

in exile in Bucharest. Twenty years later, or approximately a hundred years

ago, the first text book in the Bulgarian language appeared, a rather simple

primer with a number of excellent observations on methods of teaching.

This does not mean that before that there were no schools whatsoever

in the country. There were, indeed, scores but they were of a very primitive

nature, largely unadapted to the needs of the people and taught by untrained

monks with a limited outlook and completely antiquated methods. They were

"cell-schools" located at various monasteries or in churches and most of

the instruction they furnished was of a religious or ritualistic nature.

The pupils sat in bare, drab rooms and spent much of their time in learning

formal exercises by heart. In these "cultural hearths" the Bulgarian fire

smouldered but weakly yet they deserve the gratitude of the people for

preserving the sparks of a national consciousness at a time when all the

Bulgarians were in political bondage to the Turks and in spiritual bondage

to the Greeks.

Naturally an awakening people craved better schools, a few of which

they received from two different sources. First, a number of good Greek

ones were opened in various places in the country and later several excellent,

aggressively nationalistic Bulgarian schools were founded. The best known

of the latter was the High School at Gabrovo, in central Bulgaria, founded

in 1835 by Vasil E. Apriloff, a rich Bulgarian merchant living in Russia;

it was long maintained by him and his fellow patriots and played a notable

role in Bulgaria's awakening. It was followed by many other private and

communal enterprises of a similar nature.

Their appearance showed that the nation was being aroused from a half

millennial sleep. But progress was difficult, .for most of the Bulgarians

were peasants — very poor and backward, ignorant, timid and cowed, sharing

their wretched huts with domestic animals and completely shut off from

the outside world. Centuries of persecution, frustration and oppression

had constricted their souls, robbed them of hope and initiative and covered

them with such a dense apathy that they passed among their neighbors as

a dull and lifeless mass. Besides these villagers there were also artisans

and small retail merchants living in dreary, meager, more or less isolated

towns and travelling from place to place in the Turkish Empire to sell

their wares. And finally there were a few big Bulgarian merchants with

a knowledge of the outside world, although at that time most of the great

merchants in Turkey were Greeks.

Greece at that time set the fashion in the realm of culture, social

intercourse and business success, as far as the Near East was concerned.

Every Bulgarian merchant of any standing spoke Greek well and many of the

more cultured and better informed Bulgarians got all their knowledge of

the outside world through Greek channels.

In addition to this the Greeks had an absolutely unexcelled literature

and art while the Bulgarians had nothing. The Bulgarians were practically

without literature or culture, their language was reputed to be uncouth

and they were held in derision by all their more polished neighbors. It

seemed to the other Balkan peoples a joke to talk of the creation of a

Bulgarian culture. Even to many sincere well wishers of Bulgaria it appeared

preposterous to attempt to supplant classic Greek schools with those of

a nation of obscure Shepherds and clodhoppers. In the Bulgarian language

at that time "Bulgarian" was practically synonymous with villager or country

"jake" while the word "Greek" meant a man from the city. It was not easy

for these poor shoemakers and sellers of cheese and sheepskins to open

up "clodhopper" schools. And when they got them open it was still harder

to find teachers for them and to supply them with even the most elementary

text books. The wise laughed at these culture-spreading tailors; most of

the wealthy opposed them and the officials persecuted them, yet one new

school after another appeared, to kindle the fire of enlightenment, nationalism

and revolt among the youth. So great was the Bulgarians' desire for education

that by the time they were freed from Turkey they had nearly 1,500 schools

of which almost a score were of secondary rank, two being Junior Colleges.

After the War of Liberation the number of schools grew very rapidly

and, though for many years rather inefficiently conducted, they succeeded

in supplying one of Bulgaria's main needs, namely that of a set of state,

country and municipal administrators. The higher officials were trained

in Russia, France and Germany, but most of the clerks, assessors, teachers,

surveyors, inspectors, judges, prosecutors and other members of the new

state administration had to get their preparation at home and it was the

new schools that gave it to them. In addition, Bulgaria had to have an

intelligentsia: men to write books, publish papers, lead the political

parties, bring in the culture of the western world and guide a nation of

villagers along the path of progress, Bulgaria was the most submerged and

isolated nation in Europe, with no aristocracy and with practically no

middle class so she was in dire need of educated people to enlighten her.

These the rather primitive and insufficiently equipped schools attempted

to supply.

If one should go to the trouble of looking over the inspectors' reports

of those early days he would be distressed to learn how extremely simple

these first educational institutions were; he would be appalled at the

lack of discipline, the wretchedness of the buidlings and the ignorance

of the masters. Furthermore, if he should undertake to criticise the Bulgarian

intelligentsia, basing his strictures only on the estimates the Bulgarians

have written of themselves, if he should dwell upon the paralyzing beaurocratism

and the stifling red tape of the Bulgarian administration and if he should

be caught within the wheels of the state machinery often clumsily handled

by dull and heartless officials he might be inclined to think that the

Bulgarian schools have not done a very good job. Such simple things as

getting out a passport in Bulgaria or as entering and leaving the country

are accompanied by so many very tedious formalities, so much waiting and

the loss of so much time that the victim of these impositions is apt to

think the officials encumber the tax payers rather than facilitate them;

while, in addition, there has certainly been a tragic and disastrous estrangement

between the intelligentsia and the common people. The schools appear to

have prepared graduates to serve themselves at the expense of the masses

rather than apostles to devote themselves to the uplift of the masses.

Alexander Nevsky, Sofia, the, finest cathedral in the

Balkan Peninsula

Yet such a pessimistic estimate would be entirely unfair. One must bear

in mind the huge task which newly created Bulgaria had before her. At one

step she had to pass from the middle ages to modern times. She had suddenly

to discard the degrading traditions of Turkish anarchy and corruption in

favor of the effective methods of constitutional democracy. She had to

exchange pack horses for railroad trains and sheepskin caps for stove pipe

hats. And in this furious flight out of oriental darkness into civilization

there was no dominating tradition and no steadying aristocracy. Tradition

and authority were disregarded, and as in a gold rush, all the ambitious

people plunged forward so as to be at the head of the procession. Naturally

there was a vast amount of brutal shoving, many strident voices, intrigues

and shady combinations. The pictures which such Bulgarian authors as Aleko

Constantinoff, Stoyan Mihailovsky, S. L. Kostoff and Anton Strashimiroff

draw of the new Bulgarian intelligentsia struggling for places of power,

over-proud of its own scant culture and too strenuously endeavoring to

replace the peasant bagpipe and shepherd's flute with the lyre and harp

of classical culture are very sombre. But the fact remains that, although

the most recently created of all the Balkan states, Bulgaria has been one

of the best governed, if not the best, and that she has created in a remarkably

short time out of nothing a very creditable literature, an excellent theater,

a very good opera, a wholesome, well informed press, and an appreciably

improved standard of living. During these years not a few public men of

the type of the ancient Roman, Cincinnatus, have given their lives and

services to Bulgaria and there is no land in the Balkans freer from venality

and the baser forms of corruption. Facing the stupendous task of creating

competent and enlightened leadership for the newly emancipated nation of

peasants, suddenly determined to govern themselves along most democratic

lines, the poorly equipped and at first indifferently conducted Bulgarian

schools did not fail.

However, more than a decade ago it became plain to many observers that

although constantly improving in their technique the schools were not doing

all that they should for the nation. They were turning out graduates unfitted

to cope with life in Bulgaria. They were still creating officials for a

state already badly overstocked with officials. They were manufacturing

bureaucrats for a people already pressed by the. weight of bureaucracy.

So efforts have been made to bring about fundamental changes. This new

tendency in Bulgarian education is not due to any one group, party or individual,

but rather to the sound, practical instincts of all the thoughtful people

in the country, yet a person deserving mention as making a special contribution

to school reform is Stoyan Omarchevsky who was Minister of Education during

the time that the Agrarian League was in power, under the premiership of

the villager, Alexander Stamboliisky. Mr. Omarchevsky was for many years

a provincial school teacher and his close contact with the backward common

people, added to his wide reading, his alert disposition and his determination

to make the school system better serve the peasants, of whose party he

was one of the leaders, more than compensated for his lack of formal pedagogical

erudition and kept him close to reality. One of the chief changes he introduced

into the educational system was the lengthening of the period of compulsory

instruction from four to seven years. His aim was eventually to change

the direction of the whole educational enterprise making much of it more

practical and better fitted to teach the Bulgarian youth how to live and

work in towns and villages. He wanted the schools not to continue to turn

out state officials, lawyers and other professional men of whom the country

already had more than it could create jobs for, but to train boys and girls

how to get more wealth from Bulgarian fields, mines, forests and factories.

Dr. William E. Russell, of New York, once Associate Director of the

International Institute of Teachers' College, visited Bulgaria at the time

Mr. Omarchevsky was in office and after making a very careful study of

the Bulgarian schools wrote a book on them, entitled "Schools in Bulgaria"

in which he said among other things:

"The most interesting feature of education in Bulgaria is

the adjustment of an entire educational system to a national end. This

is the lesson that America needs to learn. There is a process of education

and a purpose of education. Here is where Bulgaria has made her contribution.

So far as the process is concerned, the American student will find relatively

little of interest. But he will be compelled to bow in admiration before

Bulgaria when it comes to finding an explanation of what it is all about".

However the educational ideals of the more progressive Bulgarians

could not be realized at once. The overproduction of a white collared intelligentsia,

frantically seeking sitting down state jobs, is not a specifically Bulgarian

deficiency. It exists in most European countries and especially in the

newer states, creating a terrible crisis almost as acute as the present

general political and economic crisis. Because of the extreme seriousness

of this problem and its very deep seated causes it could not be solved

easily nor quickly. Bulgaria is still grappling with it, persistently endeavoring

to turn the stream of her school graduates away from state clerkships into

the channels of productive private enterprises.

One method she has adopted for bringing this about is the raising of

the entrance requirements for the higher schools. She is constricting the

little end of the funnel through which the diplomaed youth flow out into

"life", meaning clerkships. A few higher schools have been closed and from

now on there will be a somewhat more rigorous process of natural selection

of pupils. The aim is of course not to make the principle of selection

wealth or social standing but native ability. From now on it is not going

to be as easy to get a college education in Bulgaria as formerly. This

apparent restricting of opportunity seems to some people undemocratic and

youth who are shut out of the higher schools because of low grades appear

to be stranded at the cross roads. But the measure is undoubtedly a wise

one, for the energy of such young people must be turned into different

channels.

Of course in this case the supreme need is to produce the new channels

and that is not easy. It is far more simple to close schools that are turning

out too many intellectuals than to open new schools capable of preparing

the Bulgarians to produce wealth and happiness in 5,000 little villages

surrounded by small and scattered fields. The young people cannot become

doctors, for already many doctors are without patients. There are far too

many lawyers. There is not enough capital nor industry to give employment

to many more engineers and architects. Business, commerce and the banks

are already over supplied with clerks and accountants. So what shall a

Bulgarian youth prepare to be and do? Go back to the farm! But it consists

of twelve acres scattered among seventeen fields so there is not much opportunity

for a college graduate to satisfy his ambitions there. It is plainly a

very difficult problem, requiring patience, devotion and much heroism.

Bulgarian villages and agriculture will slowly have to be made over. And

it is to that end that Bulgarian pedagogues and statesmen are bending their

energies.

* * *

One means for bringing this about is the recent building of the best

agricultural college in the Balkans. It is part of the State University

at Sofia and is housed in a magnificent new building for the construction

and equipment of which the American Rockerfeller Foundation contributed

115,000 dollars. The first of its twofold purposes is to carry on extensive

and expert research in order to find out exactly what methods will best

enable Bulgarian peasants to get the largest possible returns from their

fields, gardens and forests. The institution is equipped with excellent

laboratories which facilitate a number of gifted scientists in investigating

all the chief problems connected with Bulgarian soil, plant pests, animal

diseases, stock improvement, seed selection and more productive cultures.

The second aim of Bulgaria's agricultural faculty is to train expert farm

agents, both men and women, to live in the villages among the peasants

and by instruction and example show the villagers how to live better and

work more efficiently. These agents form part of a whole network of peasant

helpers of which the ganglia are agricultural "kathedras" or chairs located

in the chief agricultural centers in Bulgaria.

Yet this is, of course, the smallest part of the task of Bulgarian schools,

because after all these "experts" are state employees, with state or county

jobs, — still parts of the heavy bureaucracy, though in many ways most

useful parts. What the state chiefly needs is not to train farm agents

but to prepare the youth to work for themselves on their own land. The

aim is to tie the schools up to the land, to abolish the legend that a

diploma means an easy, more or less unproductive, routine state job. To

bring this about there are a number of lower agricultural schools for boys

and girls. Here are received only peasant children who are prepared exclusively

to return to their villages. A number of these girls' schools are among

the most inspiring institutions in all the Balkans. They take girls out

of the mud of a village and off of the floor of a peasant house but do

not separate them from their hens and pigs and bees. They do not teach

the girls to waltz and tango nor spoil them with longings to get into the

“high society” of the cities but show them how to make life in the villages,

even among the cows and pigs, fairly pleasant and even cultured. The girls

milk the cows and take care of the farm animals, they have a model dairy,

keep records of all the chickens, look after the bees, tend the vineyards

and make the wine; they learn to sew, to cook wholesome tasty food, to

preserve fruit and vegetables and to care for light sicknesses; they sleep

in beds, sing native songs, play native games and enjoy two or three happy

years, after which they go back to the village house. 1 hey soon marry

and spend the rest of their lives in trying to induce obstinate mothers-in-law

and fathers-in-law and rather domineering husbands to accept a few of the

newer, better methods. It is, of course, not an easy undertaking and seldom

do these girls succeed in introducing into their village homes many of

the beautiful things they learned in school, yet they make some progress,

helping Bulgaria to advance.

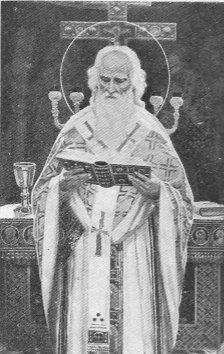

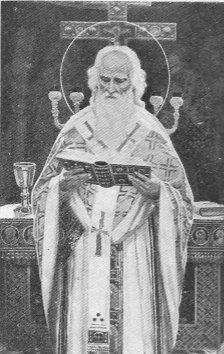

Painting by Anton Mitoff

Saint Clement of Ochrida, who lived in the ninth and

tenth centuries and was one of the most distinguished of Bulgaria's ancient

enlighteners. He was the pupil of two still more famous Bulgarian brothers,

Cyrit and Methodius, who created the Slavic alphabet and originated a large

school of gifted and indefatigable missionaries and teachers At that epoch

Bulgarian culture was almost exclusively ecclesiastical

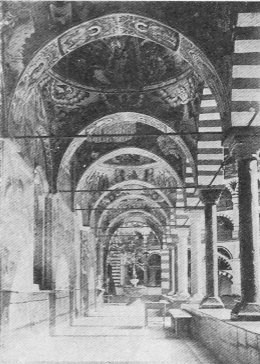

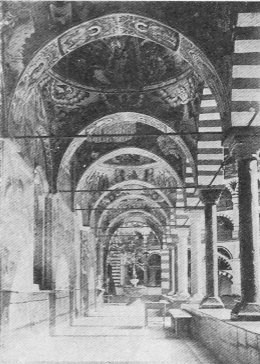

A cloister in Rilo Monastery. The interior walls and

ceilings of all Orthodox churches are covered with paintings representing

Biblical scenes. Many of them are beautiful and inspiring

* * *

Still more useful than these schools, because they reach a far larger

number of youth, are the 100 pro-gymnasium extension courses, located in

the larger villages. They are attended by boys and girls who have finished

their seventh and last year of compulsory education and are devoted entirely

to practical training and instruction in agriculture and domestic science.

They keep the youth in direct touch with peasant life and deal particularly

with the specific problems in the villages in which they are situated.

Each year exhibitions of the work of the pupils are given and every effort

is made to arouse an interest and to generate pride in efficient agriculture.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]