PART THREE. Christianity and the Byzantine Withdrawal

I. Byzantium displaces Rome 237

II. The limes in the fifth and sixth centuries 237

(Castra Martis and Ratiaria; Bononia; Botevo; Novae; Iatrus; Durostorum)

11 THE NORTHERN FOOTHILLS (II)

(Nicopolis-ad-Istrum and Veliko Turnovo; Discoduratera; Storgosia; Sadovets; Vicus Trullensium)

(Abritus; Voivoda; Pliska; Madara; Shoumen; Preslav; Draganovets; Krumovo Kale; Tsar Krum; Marcianopolis)

I. Serdica and the central region 269

(Orlandovtsi; Ivanyani; Tsurkvishte (Klise-Kuoi))

II. Pautalia and the South-West 285

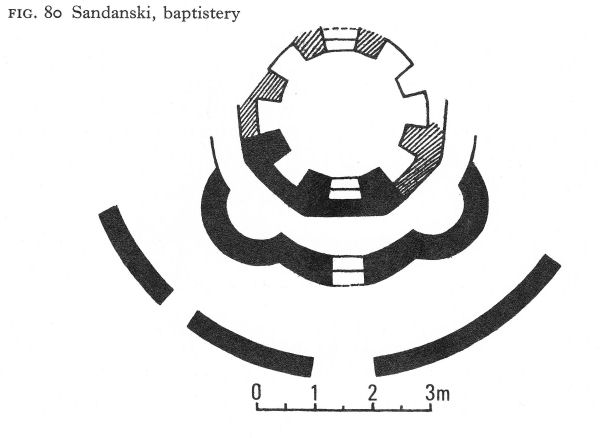

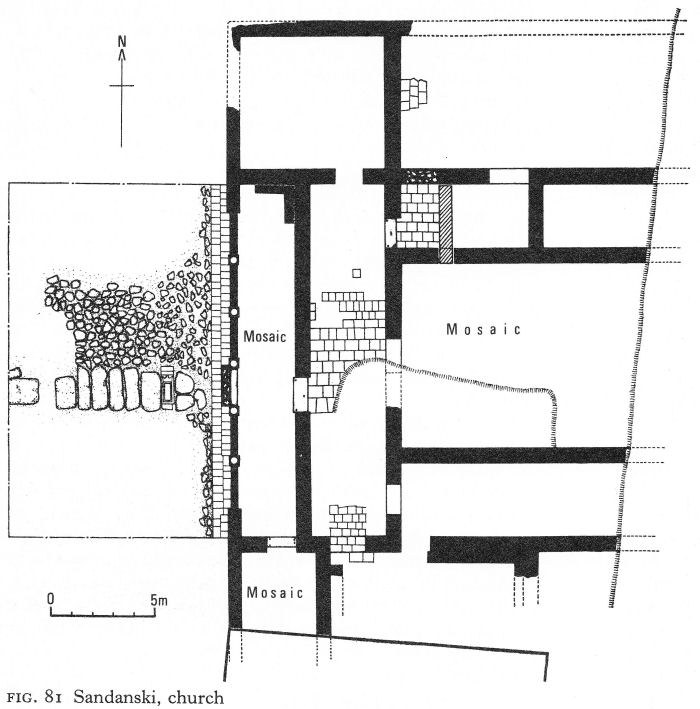

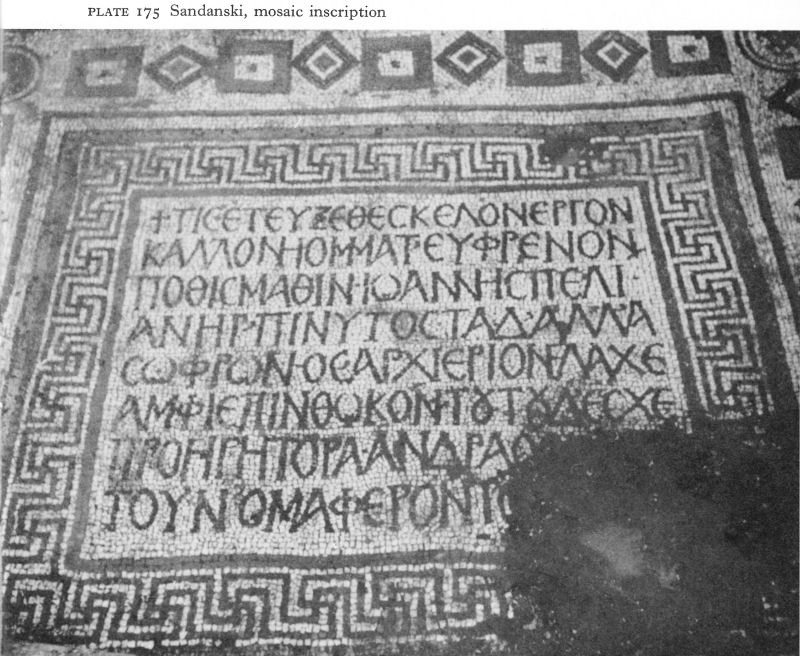

(Sandanski; The Mesta Valley)

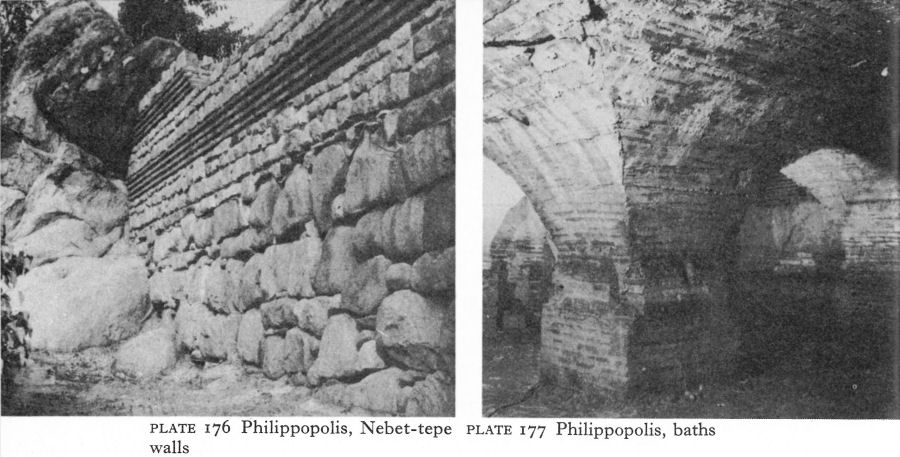

I. Philippopolis 291

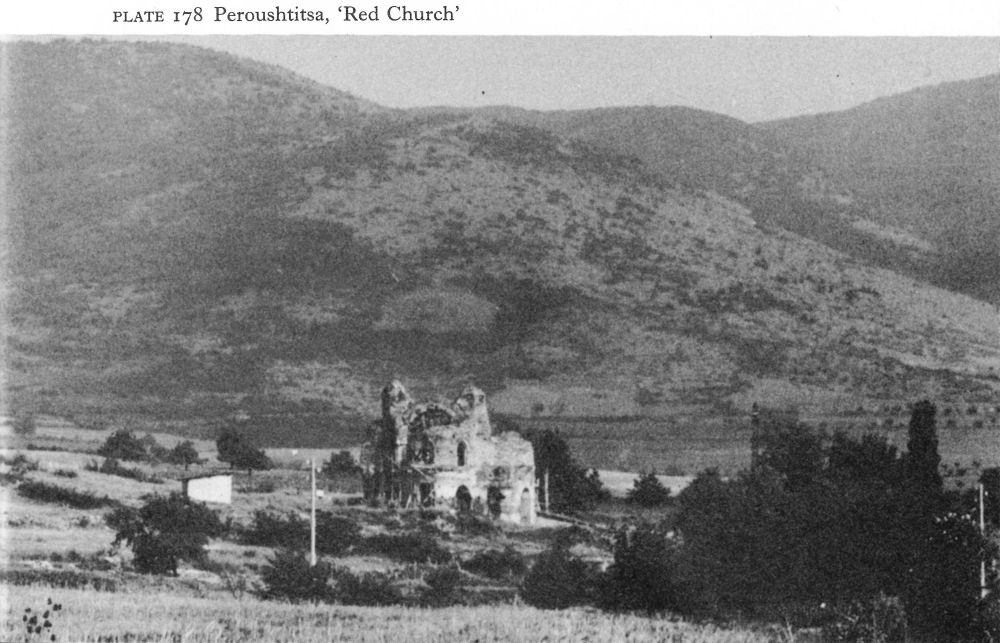

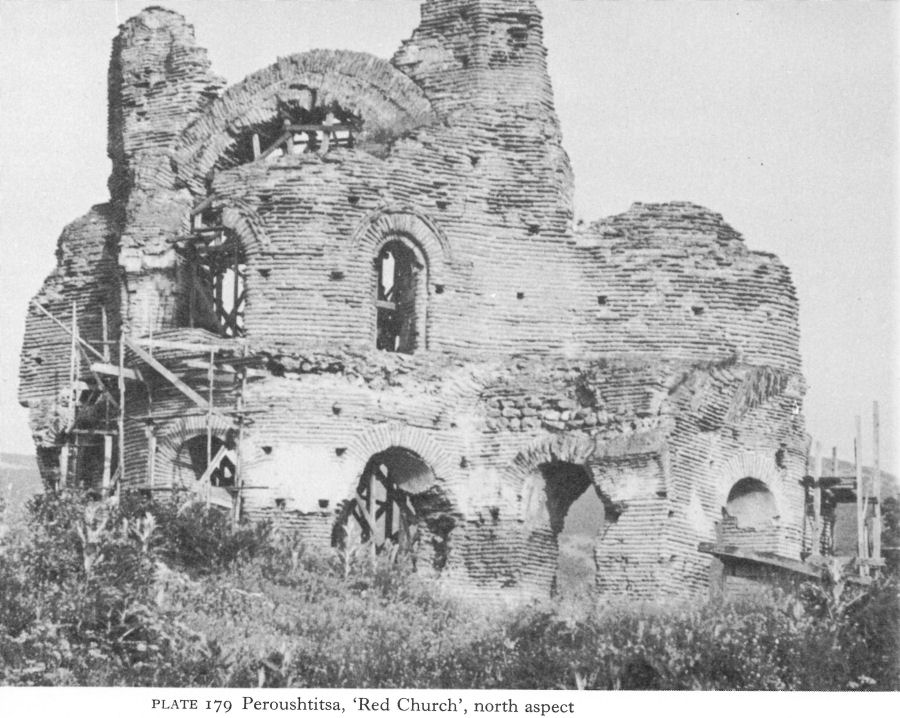

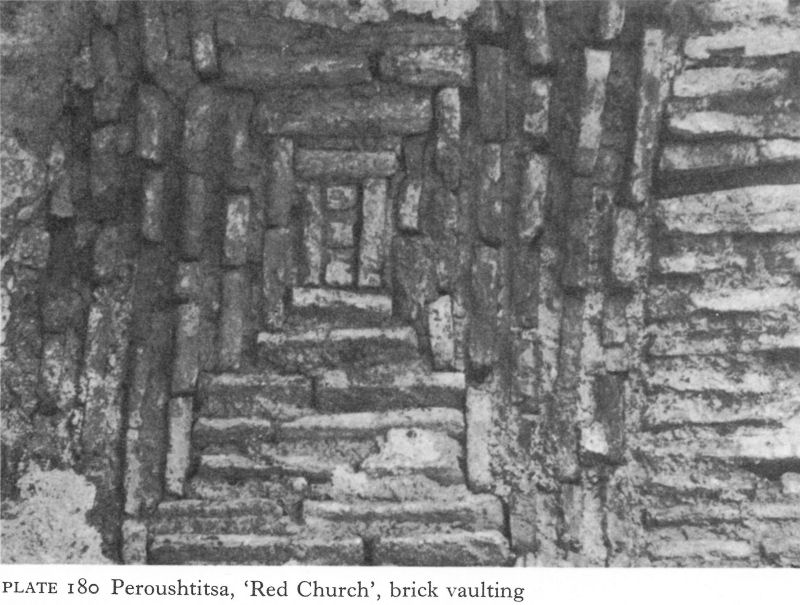

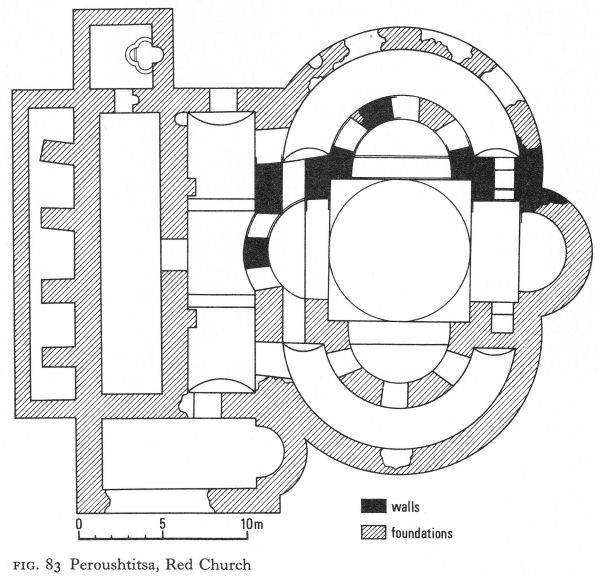

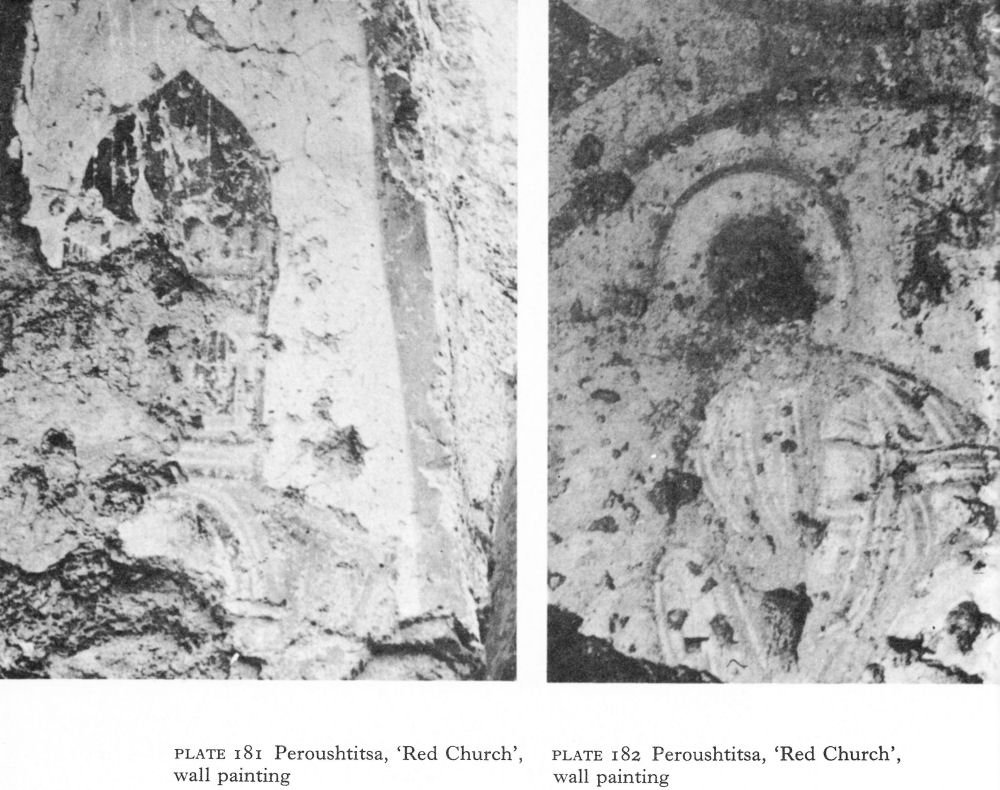

II. Peroushtitsa 293

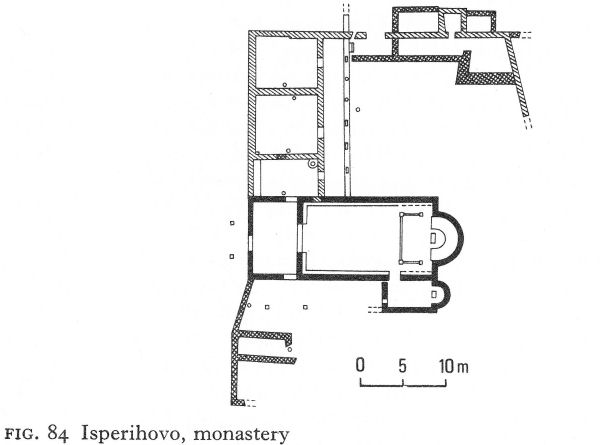

III. Isperihovo 297

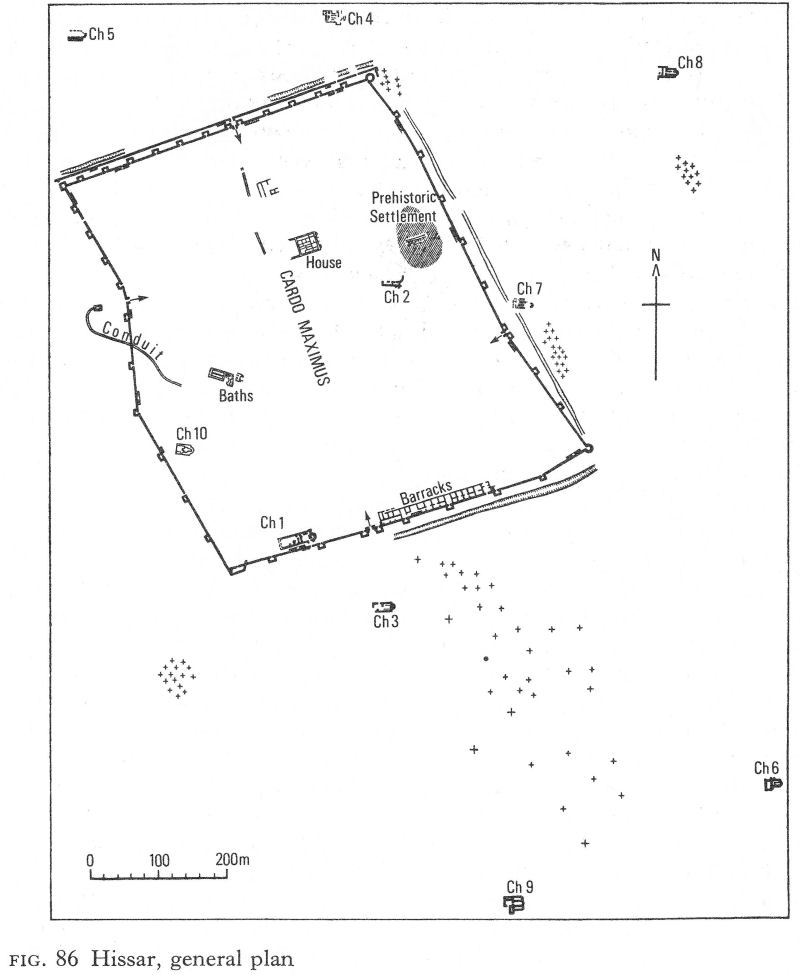

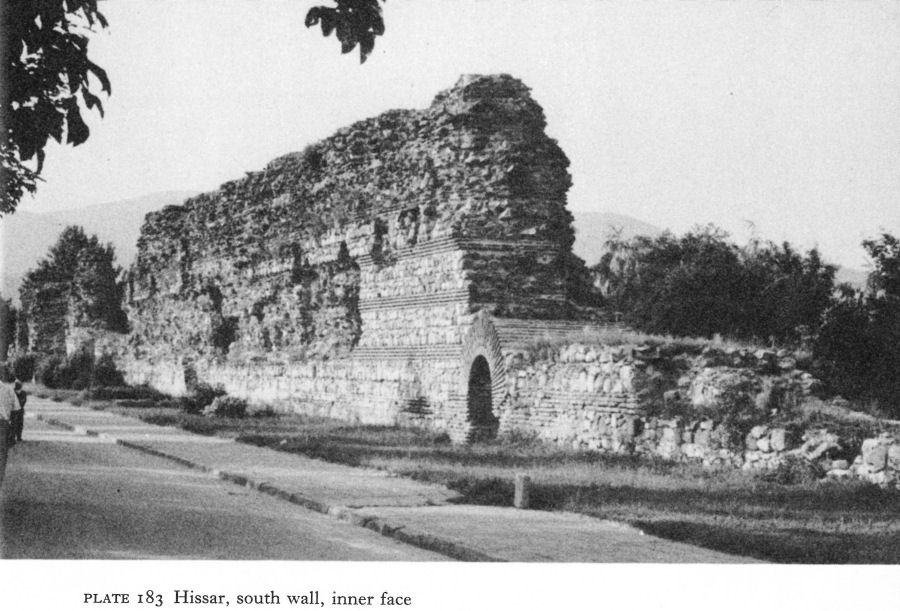

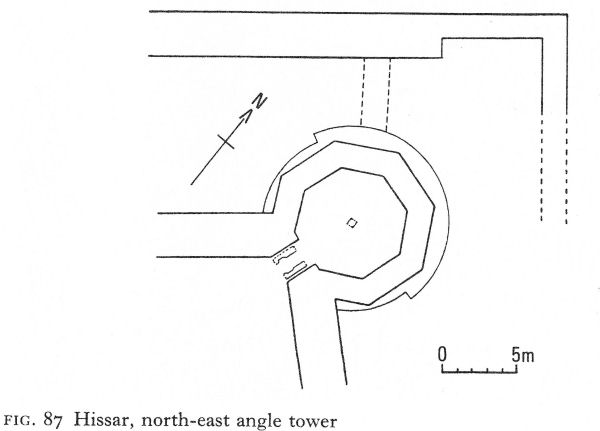

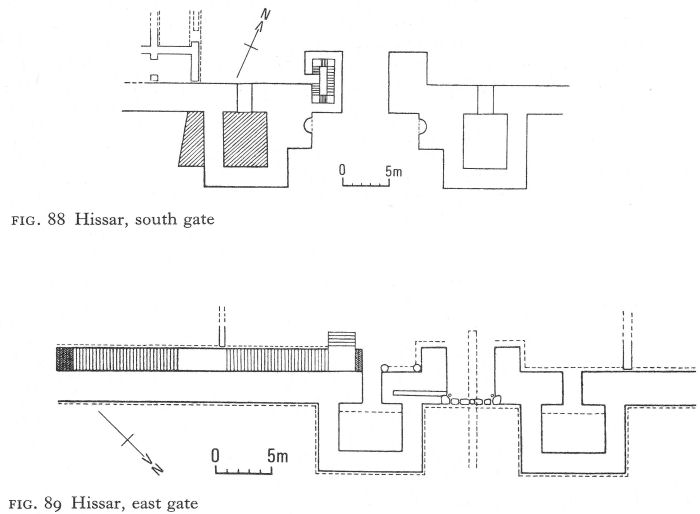

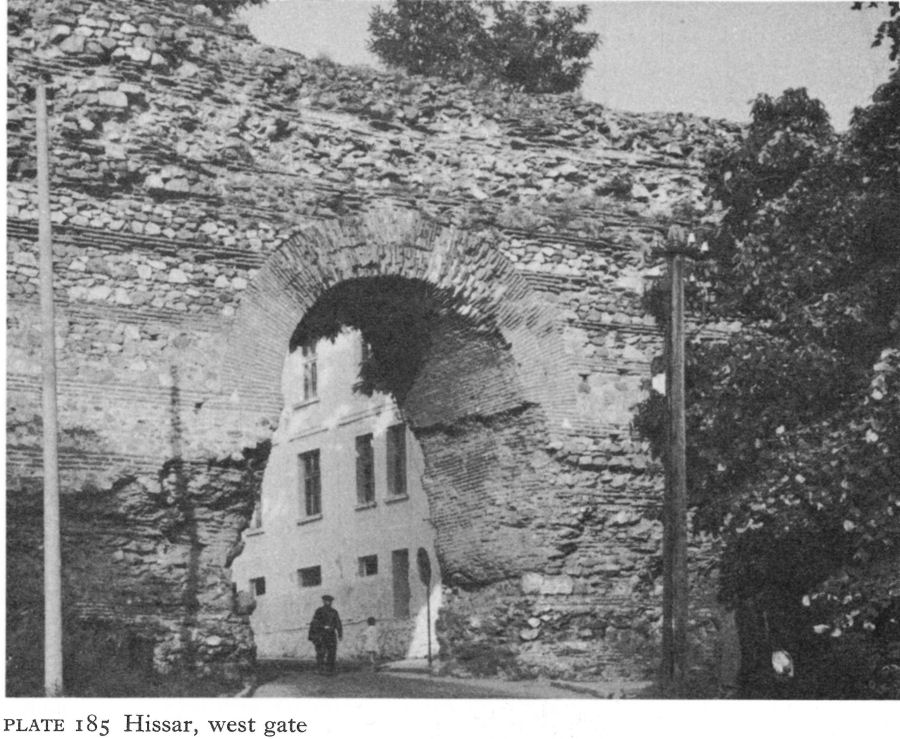

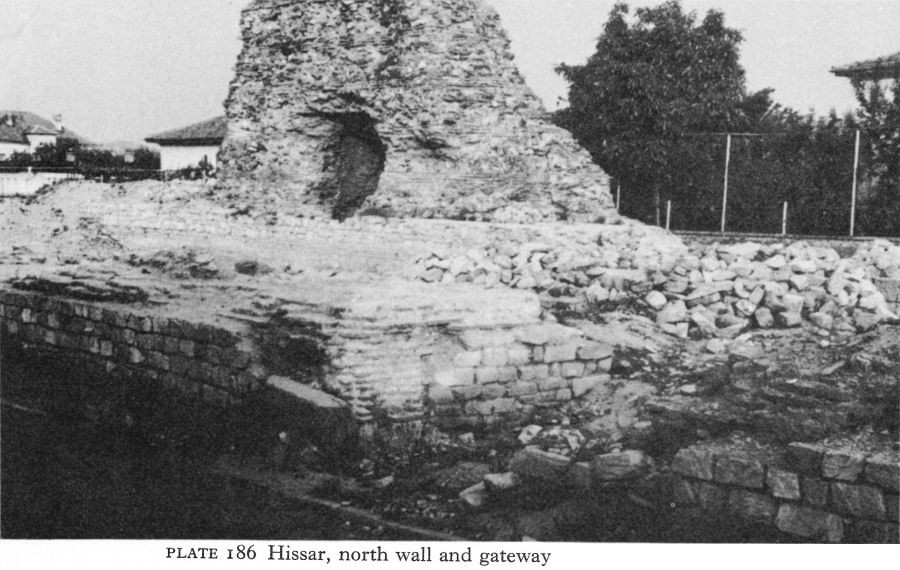

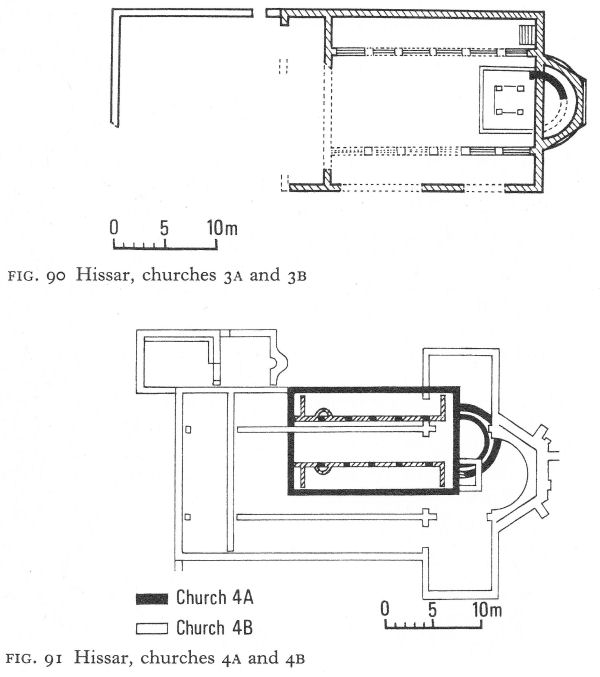

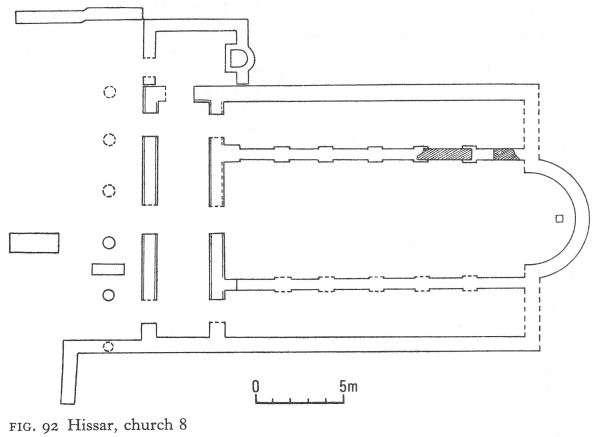

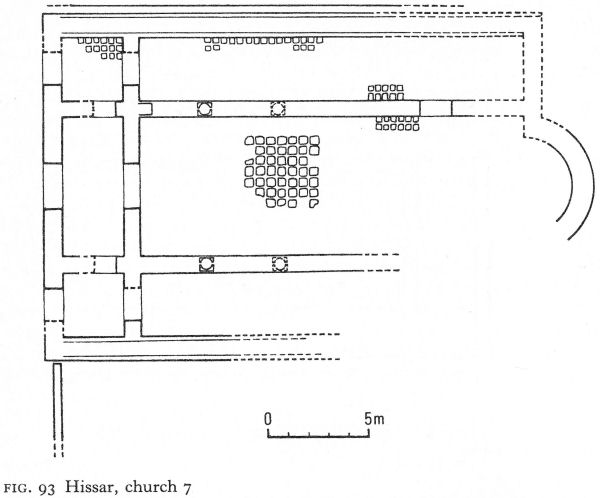

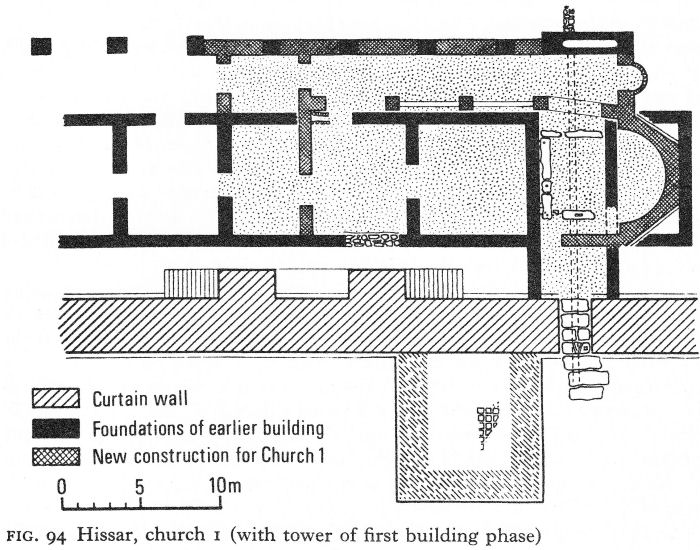

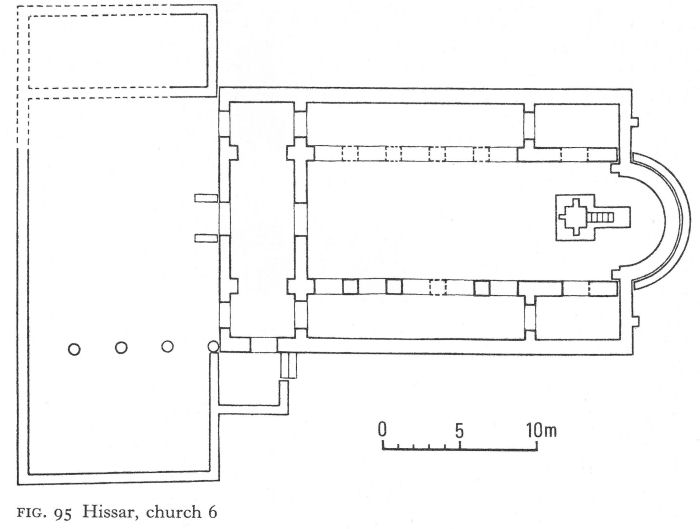

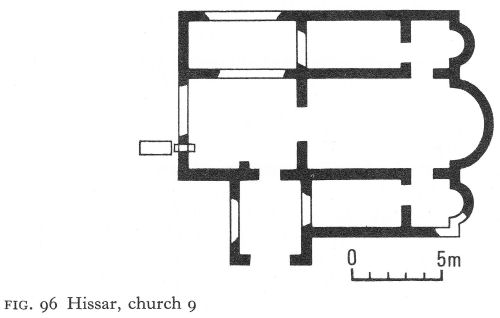

V. Hissar 300

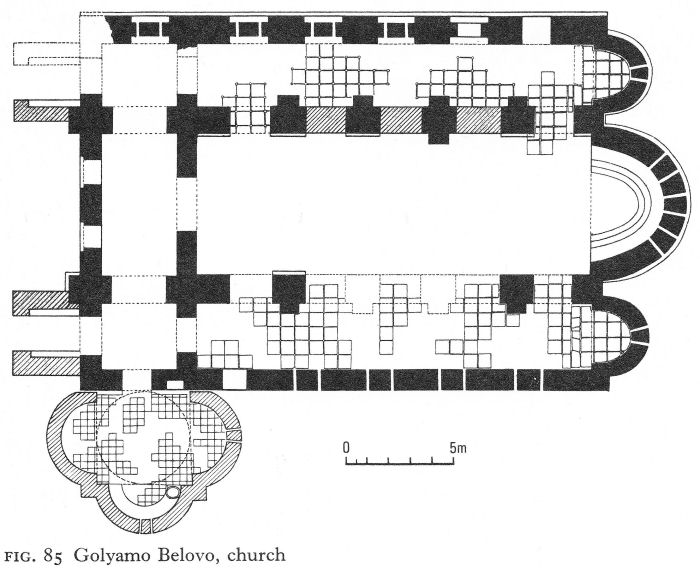

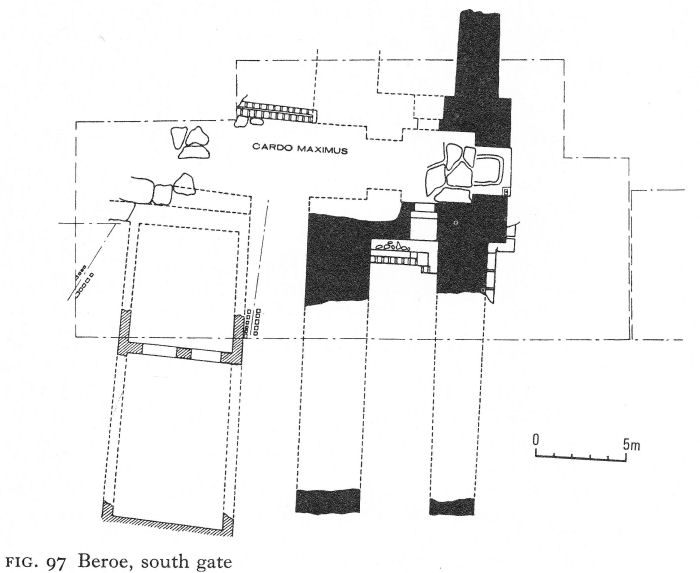

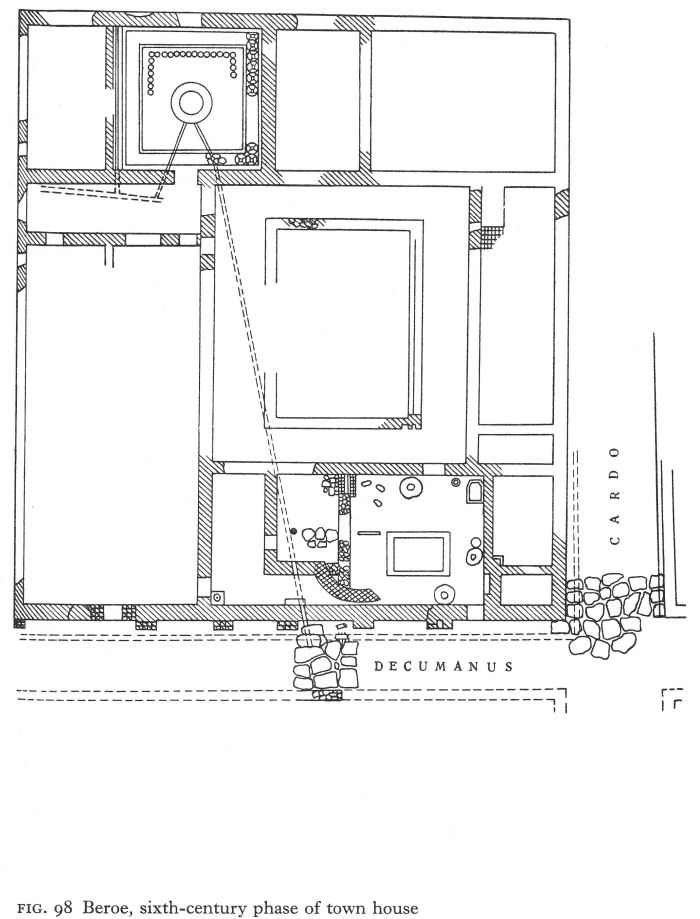

VI. Beroe 312

VII. Chatalka 315

VIII. The eastern Rhodopes 316

10 The End of the Limes

I. BYZANTIUM DISPLACES ROME

In the history of European civilisation, few centuries can have seen greater revolutionary changes than the fourth century - between the reigns of Diocletian and Theodosius I. Diocletian's reforms, aimed at consolidating the empire, instead formed the basis of its political division into east and west. This was promoted by Constantine's establishment of ‘New Rome’ at Constantinople and perpetuated by Theodosius’ bequest of the ‘Eastern empire’ to Arcadius and the ‘Western’ to Honorius.

Christianity emerged from its last and fiercest persecutions at the beginning of the century to gain official toleration in 311, imperial favour under Constantine, and religious monopoly under Theodosius. Its organisation was based on the civil structure devised by Diocletian and Theodosius. As the state religion, its churches replaced the pagan temples as symbols of both imperial and divine power, which were inextricably associated. Invariably among the most important and so most carefully built structures, the churches are often the main and sometimes, in the more vulnerable areas, the only archaeological evidence of fifthand sixth-century Byzantine civilisation.

Constantinople succeeded Rome as the political centre of the Eastern empire; but in the field of religion Rome retained its position of primus inter pares. Already the doctrinal differences were apparent which were to result in the schism between Catholic and Orthodox. Those harassed by invasions might be distracted by immediate issues of life and death or with eking out an existence oppressed by barbarians and by imperial tax-gatherers. But where men enjoyed sufficient peace to indulge in controversy religion was the burning issue of the time. Even a bishop, Gregory of Nyssa, commented in exasperation that in Constantinople

all places, lanes, markets, squares, streets, the clothes’ merchants, moneychangers and grocers are filled with people discussing unintelligible questions. If you ask someone how many obols you have to pay, he philosophises about the begotten and the unbegotten; if I wish to know the price of bread, the salesman answers that the Father is greater than the Son: and when you enquire whether the bath is ready, you are told that the Son was made out of nothing. [1]

II. THE LIMES IN THE FIFTH AND SIXTH CENTURIES

For what is now Bulgaria, the defeat and death of Valens in 378 ended an era of relative development and prosperity and the beginning of one of constant attack, insecurity, impoverishment, and changing population. The limes was no longer defended by the Romanised provincials who had replaced the Italic legionaries but, in increasing measure, by Gothic foederati. The new insecurity and its effects were especially apparent in the area between the Danube and the Stara Planina, which, with the rest of Dacia Ripensis and Moesia Prima, formed

237

![]()

![]()

238

the outer defences of the Eastern empire’s two wealthiest cities, Constantinople and Thessalonica. The major cities had remained intact, only their fortifications needed repair; generally opus mixtum with uncut stone was used. City-dwellers had suffered but had generally survived. But the countryside had been devastated. Many of the Thracian peasantry had fled their lands, been carried off as slaves, or killed. They were now replaced by defeated Visigoths, who also supplied recruits for the garrisons and the imperial army, in which they quickly rose to the highest posts.

Although during the first 40 years of the fifth century there was a degree of economic revival, the earlier prosperity was wrecked beyond recovery. The finds of fourth- and fifth-century bronze coins in place of gold and silver in the fortresses is indicative of the lower standard of living, even among the army. Taxation was increased to subsidise defence expenditure and this, together with the greed of officialdom during the latter part of the fourth century, had left most of the surviving peasants with little option but to accept the status of colon, or serf, on a large estate, to which they were legally bound by an edict of Theodosius I.

In the 440s the Huns struck briefly but disastrously. A far more terrible enemy than the Visigoths, they were now established in Pannonia and undisputed rulers of all trans-Danubia. Not only was the land once more laid waste, but with the help of siege engines, fortified cities, hitherto vulnerable only to treachery, were taken and sacked. Priscus has left a report of the attack on Naissus in 441:

. . . they brought their engines of war to the circuit wall - first wooden beams mounted on wheels because their approach was easy. Men standing on the beams shot arrows against those defending . . . the battlements, and other men grabbing another projecting beam shoved the wheels ahead on foot. Thus, they drove the engines ahead wherever it was necessary so that it was possible to shoot successfully through the windows made in the screens. In order that the fight might be free of danger for the men on the beams they were protected by willow twigs interwoven with rawhide and leather screens, a defense against other missiles and whatever fire weapons might be sent against them.

Many engines were in this way brought close to the city wall, so that those on the battlements, on account of the multitude of the missiles, retired, and the so-called rams advanced. The ram is a huge machine. A beam with a metal head is suspended by loose chains from timbers inclined toward each other, and there are screens like those just mentioned for the sake of the safety of those working it. With small ropes from a projecting horn at the back, men forcibly draw it backward from the place which is to receive the blow and then let it go, so that with a swing it crushes every part of the wall which comes in its way. From the walls the defenders hurled down stones by the wagon load which had been collected when the engines had been brought up to the circuit wall, and they smashed some along with the men themselves, but they did not hold out against the vast number of engines. Then the enemy brought up scaling ladders. And so in some places the wall was toppled by the rams, and elsewhere men on the battlements were overpowered by the multitude of siege engines. The city was captured when the barbarians entered

![]()

239

where the circuit wall had been broken by the hammering of the ram and also when by means of the ladders they scaled the part of the wall not yet fallen. [2]

In 443 the Huns made an attack on Ratiaria, but whether it was actually captured is not recorded. Naissus suffered again in 447 and in the following year Priscus passed through and ‘found the city destitute of men, since it had been razed by the enemy. In the Christian hostels were found people afflicted by disease’. His party halted ‘a short distance from the river - for every place on the bank was full of the bones of those slain in war’. [3]

The castellum of Asemus or Asamus (Musalievo), near the confluence of the Osum (the ancient Asemus) and the Danube, is unexplored. Priscus’ account shows that with courage even the Huns could be defied: Asemus is a strong fortress . . . adjacent to the Thracian boundary, whose native inhabitants inflicted many terrible deeds on the enemy, not only warding them from the walls but even undertaking battles outside the ditch. They fought against a boundless multitude and generals who had the greatest reputation . . . The Huns, being at a loss, retired slowly from the fortress. Then the Asimuntians rushed out and . . . fell on them by surprise. Though fewer than the Huns opposing them but excelling them in bravery and strength, they made the Hunnish spoils their own . . . killed many Scythians, freed many Romans, and received those who had run away from their enemies . . . [Attila refused to withdraw or make peace] . . . unless the Romans who had escaped to these people should be surrendered, or else ransoms paid for them, and the barbarian prisoners led off by the Asimuntians be given up . . . [The latter request was eventually complied with, but in spite of an order from the Byzantine commander in Thrace to comply also with the former] . . . the Asimuntians . . . swore that the Romans who had fled to them had been sent away free. They swore this even though there were Romans among them; they did not think they had sworn a false oath since it was for the safety of men of their own race. [4]

Such courage is a brave contrast with the general Byzantine policy of attempting to buy off Attila with ever-increasing sums of gold, and the return of deserters and refugees. Even two children, Hun princes and imperial protégés in Constantinople, were ignominiously handed over - to be promptly and publicly crucified.

Even a century and a half later Asemuntian independence and courage remained undimmed. Theophylact Simocattes relates that in 593 the Byzantine general, Peter, brother of the emperor Maurice, was so much impressed by the spirit of its defenders that he decided to draft them into his own army. The citizens protested strongly, producing an exemption from such service, granted them by Justin I. When Peter was obdurate, the soldiers claimed sanctuary in a church and the bishop refused to expel them from the altar. Peter then sent a captain of infantry with his troop to enforce the orders, but the captain, awed by the sanctity of the church and frightened of sacrilege, refused to obey. Peter deprived him of his rank and on the following day sent another officer into the city to bring the recalcitrant bishop to his camp.

![]()

240

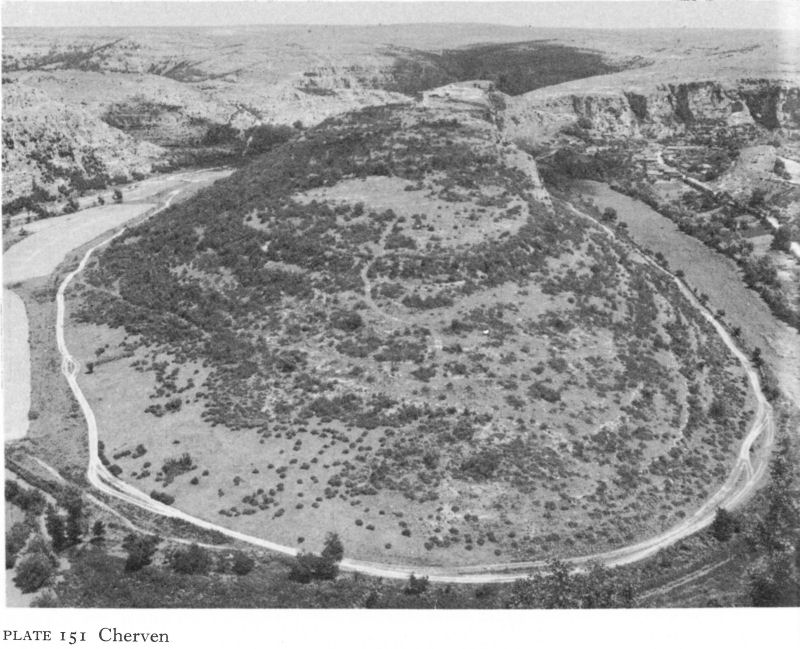

Plate 151 Cherven

The citizens drove the officer away, shut the gates on him, and stood on the walls, loudly praising Maurice and reviling Peter, who beat an ignominious retreat.

Little more than ten years separated the disintegration of the Huns after Attila’s death from the Ostrogothic wars. There is an echo of Ovid’s complaints in Jordanes’ description of the Danube at about this time.

. . . when the wintry cold was at hand, the river Danube was frozen over as usual. For a river like this freezes so hard that it will support like a solid rock an army of foot-soldiers and wagons and sledges and whatsoever vehicles there may be - nor is there need of skiffs and boats. So when Thiudimer, king of the Goths, saw that it was frozen, he led his army across . . . [5]

From 481 until 488, Theodoric the Amal, son of Thiudimer, under a treaty with the emperor Zeno, ruled land which had been within the empire for nearly 500 years; his kingdom covered parts of Moesia Secunda and Dacia Ripensis and his capital was Novae, the old home of Legio I Italica.

Towards the end of the fifth century, large numbers of Isaurian rebels from south-east Anatolia were forcibly resettled in Thracia; it is likely that the depopulated north received many of them. Their presence may explain liturgical

![]()

241

innovations of oriental origin which are reflected in the architecture of some of the churches of this time.

In the sixth century, the policy of defence in depth was intensified. Many Danube fortresses were strengthened and repaired under Anastasius, Justin I, and Justinian, Procopius giving full credit to the last, but increasingly they became isolated outposts. The rapidly diminishing security they could offer spurred the civilian population to depart, a process already begun in the fifth century, especially since they could no longer support themselves by work beyond the walls or by unwanted luxury crafts within them. On fortified hilltop refuges in the Stara Planina and the Ovche hills round Shoumen, existence could be prolonged in conditions of varying comfort or even luxury. In this way, for example, the inhabitants of Sexaginta Prista are said to have evacuated themselves to the naturally defended site of Cherven on the Cherni Lorn river, where below the long-known medieval fortifications, walls of the Early Byzantine period have recently been uncovered (Pl. 151).

Meanwhile, quietly, the Slavs began to fill the deserted northern lands. At first they were probably welcome as a valuable source of agricultural labour and quickly assimilated. Particularly in north-east Bulgaria - at such sites as Nova Cherna, where there was an Early Byzantine fortress, Garvan, and Popina - the many traces of Slav habitation in the sixth century included Christian burials. They were also another source of recruitment; from 530 to 533 a Slav, Hilbud, was a successful commander of the Byzantine forces. But the pressure of numbers became too great to be absorbed and during the second quarter of the century military incursions increased, leading up to a massive invasion in 550 that reached the Aegean coast.

By 586 a new military power, the Avars, described by the Byzantine military historian Michael the Syrian as ‘the accursed barbarians with unkempt hair . . . from the extremities of the Orient’, were established in Pannonia and only held off by annual tribute from invading the empire. Fleeing from their oppression the Slavs surged across the Danube, the border garrisons depleted by wars in Asia. Following the traditions of Byzantine diplomacy, Tiberius II invited the Avars to attack the Slavs from the rear. The Avars came, but not to waste time on the Slavs, with whom they joined forces. John of Ephesus describes the situation:

The accursed people, the Slavs, advanced and invaded the whole of Greece, the environs of Thessalonica and the whole of Thrace. They conquered many towns and fortresses, they ravaged, burned, pillaged and dominated the country, which they inhabited as if it were their own land. This lasted four years, as long as the Basileus [emperor] was making war against the Persians; in this way they had a free run of the country until God drove them out. Their devastations reached as far as the outer walls [of Constantinople]. They took away all the imperial flocks and herds. Now [584] they are still quietly settled in the Roman provinces without anxiety or fear, laying waste, murdering and burning. They grow rich, they possess gold and silver, they possess flocks and horses, and many arms. They have learnt to wage war better than the Byzantines. [6]

The last of the Danubian fortresses fell early in the seventh century. By the middle of the century the hilltop refuges had suffered a similar fate and north

![]()

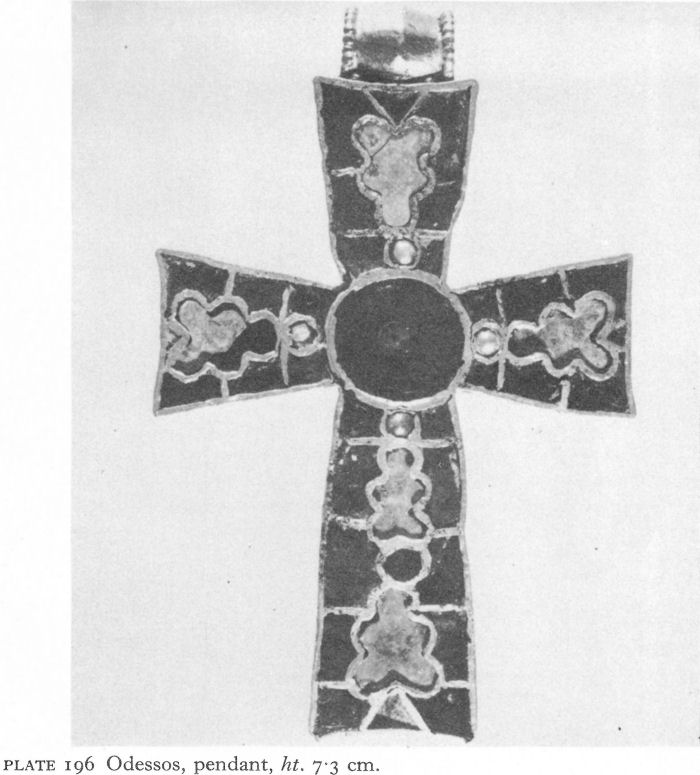

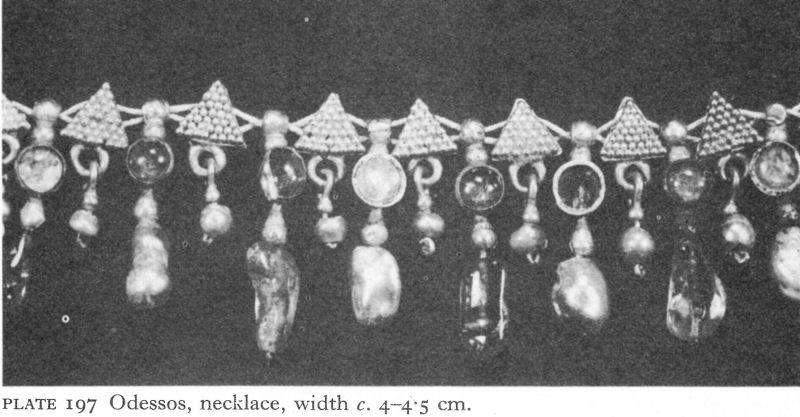

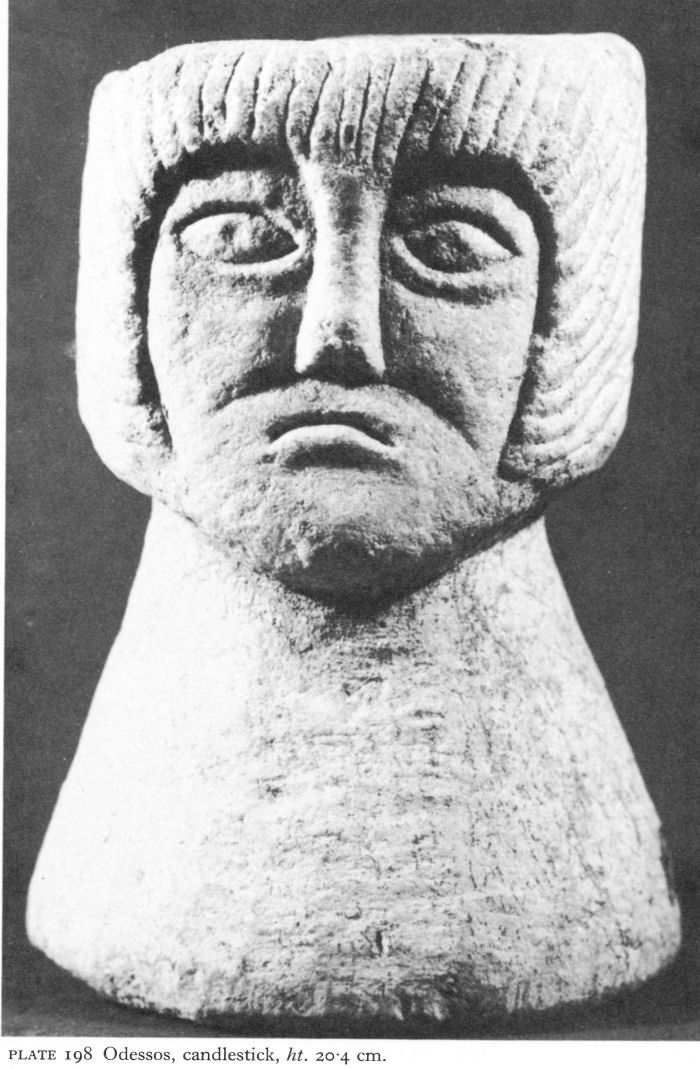

242

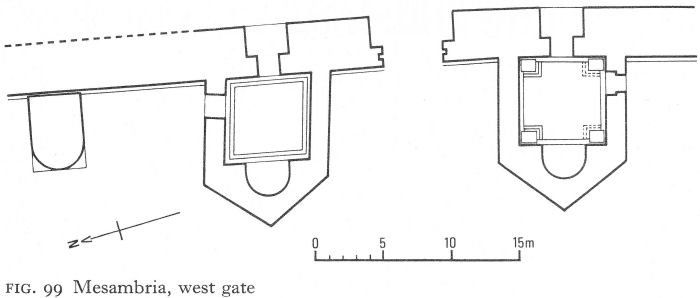

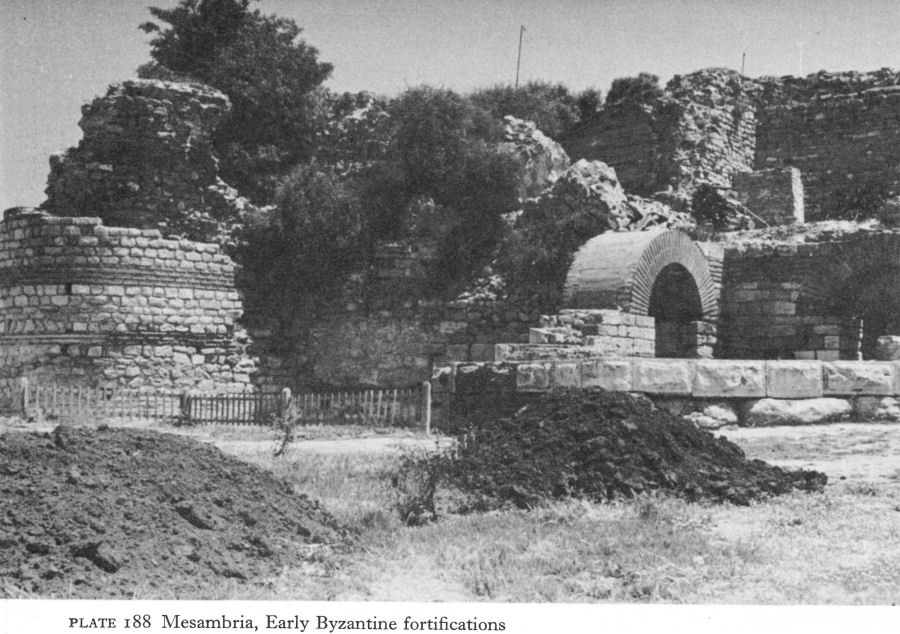

of the Stara Planina only Odessos is known to have remained in Byzantine hands. South of the range there remained Serdica, Philippopolis, Beroe (lost but later retaken), and Mesambria.

The Slavs were no longer invaders; they were occupiers who had made the country their own. There was no question of evicting or conquering them. The Byzantine strongholds possessed a trade and cultural function, as well as a military one, but their role was merely defensive.

The emphasis on destruction during the fifth and sixth centuries inevitably limits the archaeological record and most of the survivals of the Danube limes are Roman rather than Early Byzantine. The latest phase was the first to be demolished, whether by enemy action, decay, or for building materials, and, where reconstruction took place, as often occurred in the medieval period, the Roman remains usually provided the more solid foundation, with the exception of some of the fortifications erected in the first half of the sixth century.

Castra Martis and Ratiaria

Castra Martis was captured by the Huns in 408-9, thereby escaping the terror of Attila, but although it was refortified by the Byzantines in the sixth century and substantial remains exist of the fort at Kula, it seems never to have regained its former prominence. Ratiaria, still a large and rich city in the fifth century, suffered heavily during the Hun invasions. Both cities fell to the Avars.

Bononia

Bononia grew in importance during the fifth and sixth centuries, probably superseding Ratiaria after the Hun invasions. Several sections of the fortress wall of this period, including six towers, have been identified. With four sides of unequal length, they enclosed an area of about 23 hectares. Towers at intervals of about 100 metres were connected by curtain walls with foundations 4.30 metres thick. Bononia suffered heavily from both Huns and Ostrogoths, and Procopius speaks of repairs to its defences. It, too, finally succumbed to the Avars, although there is historical evidence for some limited cultural continuity.

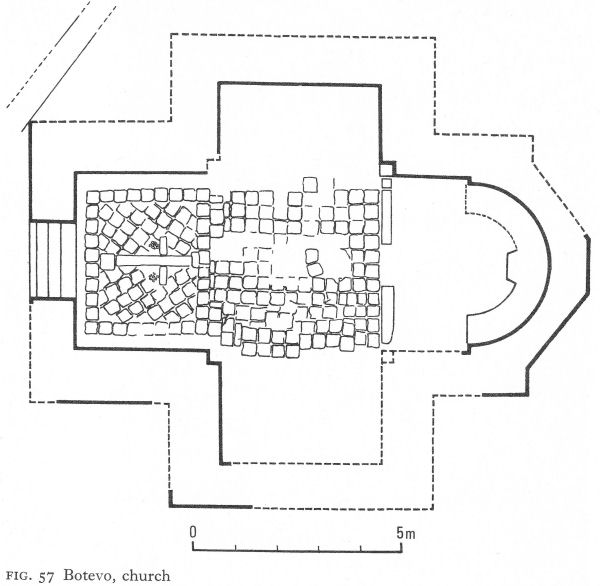

Botevo

Botevo, on the Danube 5 kilometres east of Ratiaria, has archaeological remains indicating a minor settlement or military outpost of the city in the Early Byzantine if not also the Roman period. In 1947 remains were discovered of a small Early Byzantine church of unusual plan - a free cross with arms of slightly unequal length, the eastern terminating in a three-sided apse (Fig. 57). In some places the brick walls were over a metre high; elsewhere only foundations remained. From a west doorway steps led down to a brick floor. Three marble blocks from the altar screen found in situ showed that the sanctuary occupied the whole eastern arm of the cross.

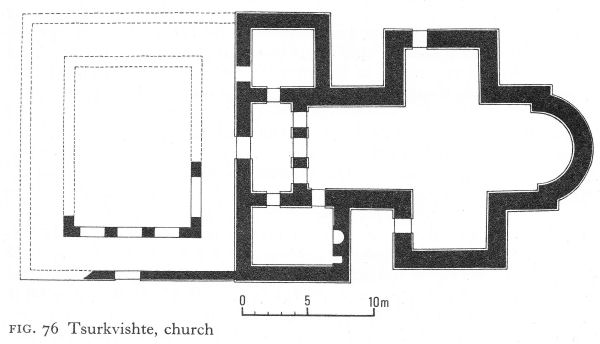

The brick construction and the existence in the debris of sixth-century amphora fragments and Slav pottery suggest a date about the turn of the fifth-sixth centuries. Anastasius’ resettlement of the Isaurian rebels in Thracia at this time might account for the unusual plan. Analogies with the cruciform churches at Tsurkvishte and Ivanyani (p. 279) suggest the possibility of a funerary function.

![]()

243

Fig. 57 Botevo, church

Novae

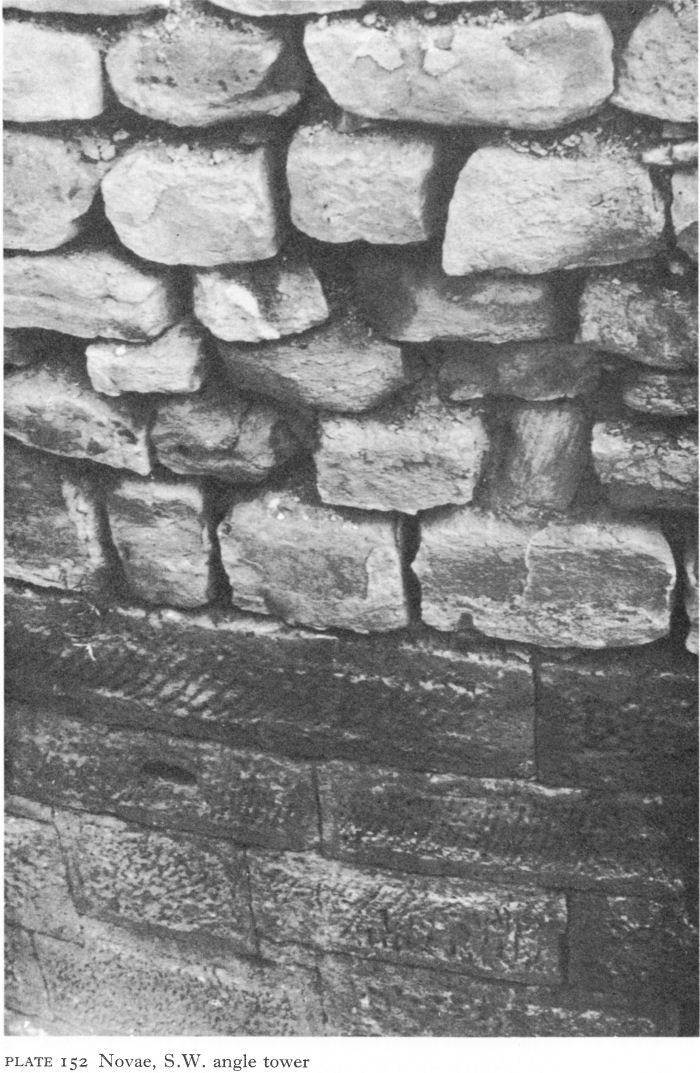

The line of Novae’s original north, south, and west curtain walls and the fourth-century east wall seem generally to have been preserved during the Early Byzantine period, although the inferior building techniques of the later repairs and reconstructions can be clearly detected (Pl. 152). On the east there are signs of one or more walls, in some places inside, in others outside, the main wall excavated (Fig. 21). Some repairs were probably needed following the Hun attacks, but Theodoric’s residence must have preserved Novae from Ostrogothic devastation, and his departure for Ravenna in 488 left it to resume its role as a frontier outpost. Although Procopius mentions some refortification nearby, the city’s defences were apparently sound; no typical sixth-century triangular or pentagonal towers have been uncovered.

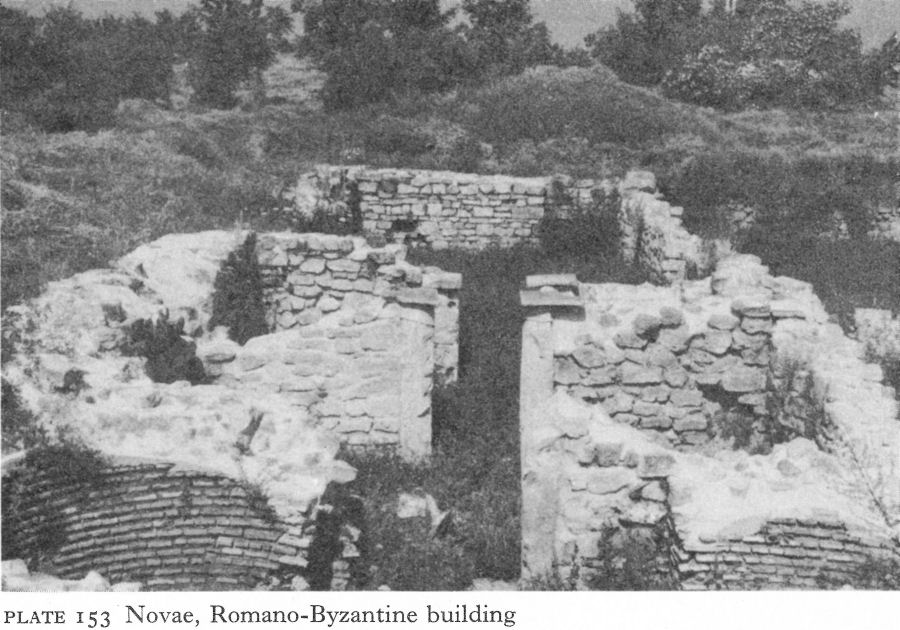

In the north-west sector a large building has been partially excavated.

![]()

244

Plate 152 Novae, S.W. angle tower

![]()

245

Plate 153 Novae, Romano-Byzantine building

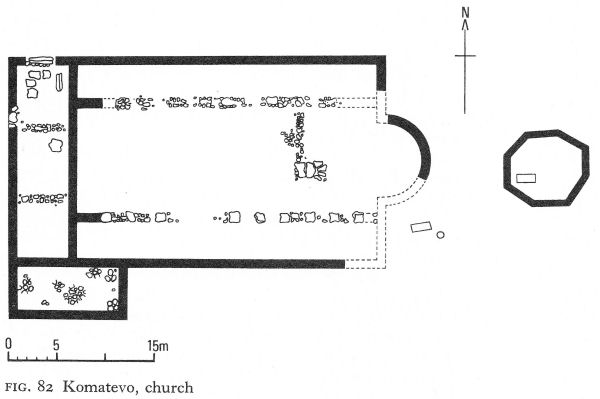

It had a hall with two central piers or columns which led through two narrow rooms to a chamber with two brick-built apses (Pl. 153). The building, its purpose still unclear, was erected during the Roman and reconstructed in the Early Byzantine period.

One church, a much-damaged single-apsed, three-naved basilica, has recently been discovered. Three bishops of Novae, like all others in Moesia Secunda subject to the archbishop of Marcianopolis, are known by name about the mid-fifth century and another, anonymous, is mentioned in 594. The name - and the name only - of one local martyr, St Lupus, has survived through the appearance of Peter, the Byzantine general who fared so ill at Asemus, at Novae on the saint’s feast day; Peter accepted a pressing invitation to remain for the two-day celebrations.

Novae survived into the seventh century but only for a few years.

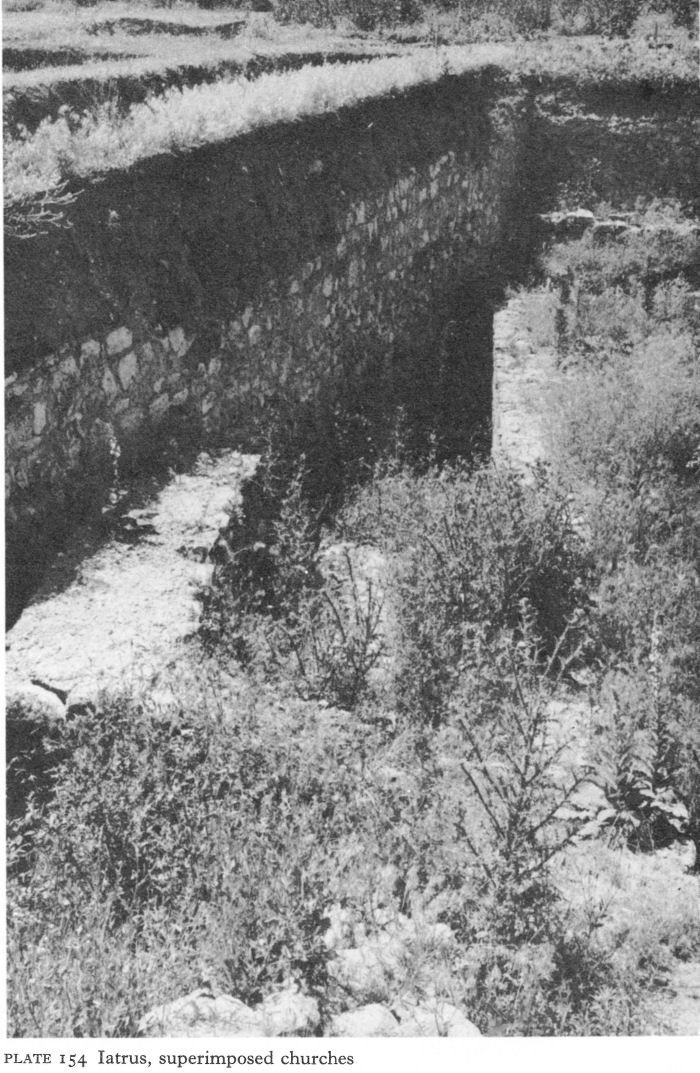

Iatrus

Iatrus, having escaped damage by the Visigoths, was sacked, probably by the Huns, and occupied by the Ostrogoths in the fifth century.

A church (Basilica 1) was built inside the walls, probably in the last years of the fourth century or early in the fifth (Fig. 26). Three-naved with a single semicircular apse and a narthex, it was 22 metres long, including the 4 1/2-metre-deep apse, and 12 metres wide. The floor was brick-paved and the walls, nearly a metre thick, of opus mixtum with several courses of brick. A Mithraic altar was re-used as building material.

The apse, surviving only to the height of a few centimetres above the floor, contained what was probably the remains of a synthronon - seats round the wall for the clergy - constructed of stone and faced with tiles.

![]()

246

Plate 154 Iatrus, superimposed churches

![]()

247

Plate 155 Durostorum, fortress wall

Debris here included fragments of a white marble altar table, its slender columns decorated with stylised acanthus leaves, and a shallow reddish-brown clay dish with a cross stamped in the centre.

Soon after this church was built and before the end of the first quarter of the fifth century, the eastern end of the massive annex in the south-west corner of the fortress wall (p. 134) was demolished to provide space and material for houses. Basilica 1 was burnt down sometime in the fifth century, as well as the two-storeyed rectangular structure and some remaining parts of the south-west annex, when the castellum was sacked.

The wreckage was used as a quarry by the next inhabitants, perhaps Ostrogoths. Fragments of columns, capitals, and bases were used in fifth- or sixth-century houses. One or more were built on top of the church, their stone foundations using its columns and bases but their walls of mud brick. After a time these, too, perished in flames.

Basilica 11, built above the first, was larger and its construction seems to have followed immediately on the destruction of the houses, early in the sixth century. Their debris raised the new floor 1-77 metres above that of the earlier church. Judging by the foundations, which alone remain, the plan was the same as its predecessor’s, an interesting exhibition of conservatism on the part of the inhabitants. Just over 30 metres long without the apse, its substantial walls and stylobates suggest a barrel-vaulted roof.

Iatrus is mentioned by Procopius as a fort repaired in the sixth century, but

![]()

248

its role seems to have changed from that of a military castellum to a fortified refuge for people in the country round about during raids by Avars and Slavs. Excavation has uncovered a group of small, flimsy, single-roomed houses, employing old masonry and architectural fragments but for the most part built of mud bricks, plastered inside with clay. An unusual feature in some of the outer walls was that at about 1-metre intervals the horizontal rows of mud bricks were intersected by a vertical line of similar bricks, apparently performing the function of upright stakes or beams. Wooden beams - some with decorative carving - were, however, used for roofing, covered with reeds or straw and weighted down with heavy tiles. Household goods and tools were relatively primitive.

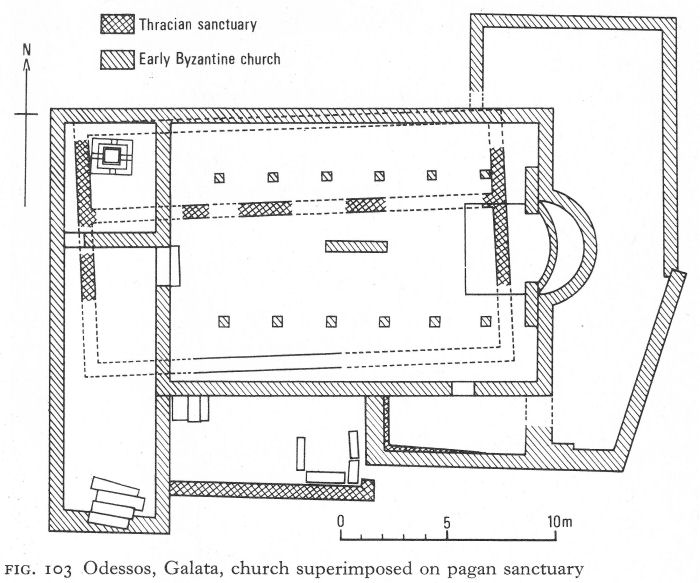

About the year 600, these humble dwellings, together with the fortifications and any other buildings, perished at the hands of Slavs or Avars in a final conflagration so fierce that the excavated mud bricks had almost the appearance of having been fired in a kiln.

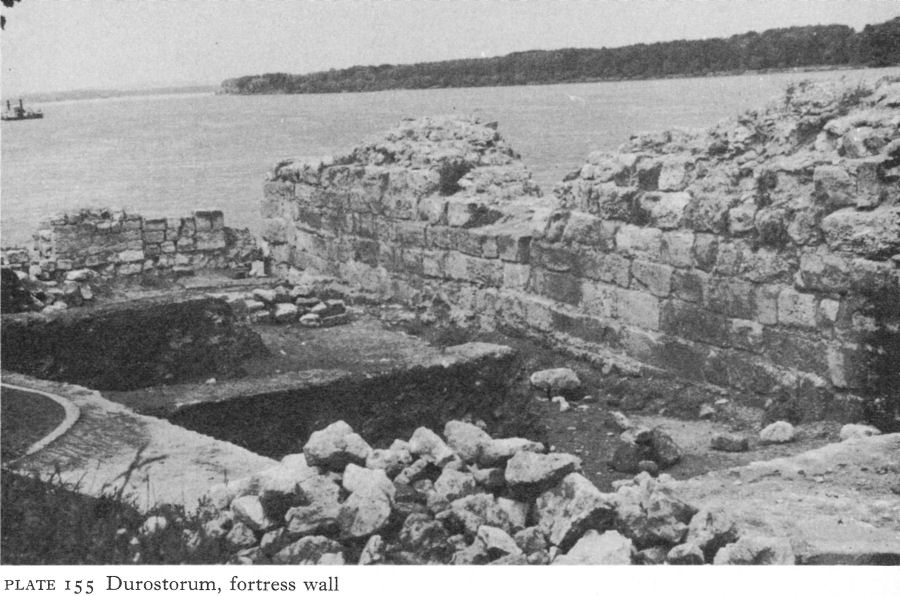

Durostorum

Modern Silistra has far outgrown Durostorum, which remained a rock against which barbarian waves broke in vain until 584 when it fell to the Avars. An inscription suggests that its bishop, Dulcissimus, sought refuge in Odessos, where he died. One of its sons, Aetius, was the imperial general whose victory over Attila in the battle of the Catalaunian plains, near Châlons-sur-Marne, ended the Hun threat to western Europe.

A recent rescue dig in connection with the construction of a new harbour has uncovered parts of an Early Byzantine fortress wall beneath one of the ninth or tenth century [7] (Pl. 155). Otherwise little if anything is known from the Early Byzantine period, but the city seems to have continued some kind of existence until the Bulgar invasion of 681.

NOTES

1. Migne, J. P., Patrologia Graeca, 46, p. 557

2. Priscus, fr. 1b, trans. Gordon, C. D., The Age of Attila, Ann Arbor, 1960, 64, 65.

3. Ibid., fr. 8, 74.

4. Ibid., fr. 5, 67, 68.

5. Jordanes, Getica, LV, 280, trans. Mierow, C. C., Gothic History of Jordanes, Princeton, 1915, 132.

6. Tafrali, O., Thessalonique des origines an XIVe siecle, Paris, 1919, 98, 99.

7. NAG, Arh XII/3, 1970, 81.

11 The Northern Foothills (II)

I. THE CENTRAL SLOPES

Although fortified, the urban centres in the interior of western Moesia Secunda had a fundamentally commercial rather than military function. While they had mainly survived the Visigothic attacks, their economies had been severely disrupted and during and after the Hun and Ostrogothic invasions even survival largely depended on natural defences. If the site was vulnerable, the population, provided they acted in time, moved south to stronger positions in the Stara Planina or beyond.

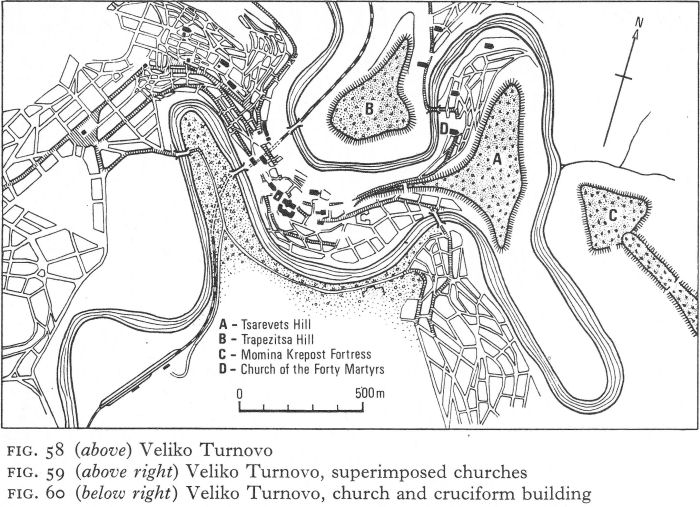

Nicopolis-ad-Istrum and Veliko Turnovo

Until there are results from the new excavations at Nicopolis-ad-Istrum, the city’s existence after the Visigothic wars must remain an enigma. Its fall is not recorded; it is not even listed as a city attacked by the Huns. Procopius mentions the establishment of a fortress of ‘Nicopolis’ by Justinian, but, as remains of an Early Byzantine fort have recently been reported at Danubian Nikopol, [1] the reference may have been to this site. Bishops of Nicopolis-ad-Istrum are, however, mentioned about 458 and 518. At the time of writing, archaeological evidence is limited to the aerial photograph reproduced in Pl. 94. From this the construction may be deduced of a much smaller fifth-sixth-century fort abutting on to and using part of the south wall, but this reading requires confirmation by excavation.

Sometime after the Visigothic invasions, perhaps gradually, the inhabitants of Nicopolis-ad-Istrum left their city for Veliko Turnovo, where the river Yantra twists and turns through a deep gorge to create a chain of steep-cliffed peninsulas. One of them, the Tsarevets hill, was ideally situated for defence (Fig. 58). Coins of Heraclius and Constantine III show that it survived some fifty years after most of the Moesian fortresses, although it, too, finally perished in flames. Fifthor sixth-century fortifications have also been found on another Turnovo hill, the Momina Krepost, across the river from the Tsarevets.

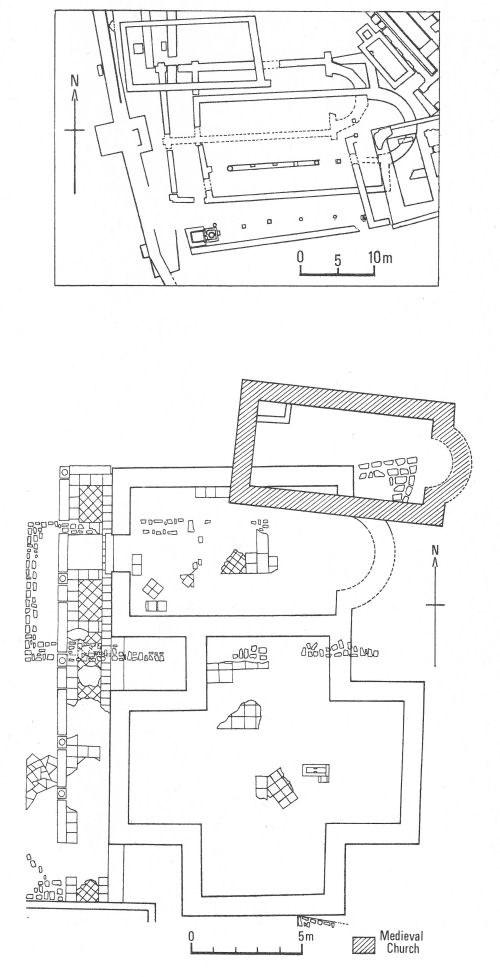

The discovery that Turnovo was an important Early Byzantine city and not merely a strongpoint in the sixth and seventh centuries stems from the unexpected find in 1961 of an Early Byzantine church and annexed buildings beneath the medieval palace complex on the Tsarevets hill. Later excavations have shown that the whole hill was inhabited during this period. A plan of a three-naved basilical church with a single semicircular apse, a narthex, and remains of mosaics and wall painting, superimposed above a smaller single-naved basilica, was published in 1965 (Fig. 59). [2] Further investigation has now identified as many as four superimposed basilicas on this site close to the north gate and the excavation of other buildings provisionally assigned to the reign of Justinian is in progress. [3] Although the fifth- or sixth-century fortifications were probably levelled to serve as foundations for the medieval walls, a contemporary double gate, the outer portcullis divided by a propugnaculum from the inner swing doors, and a triangular tower nearby have been uncovered.

249

![]()

![]()

250

Fig. 58 (above) Veliko Turnovo

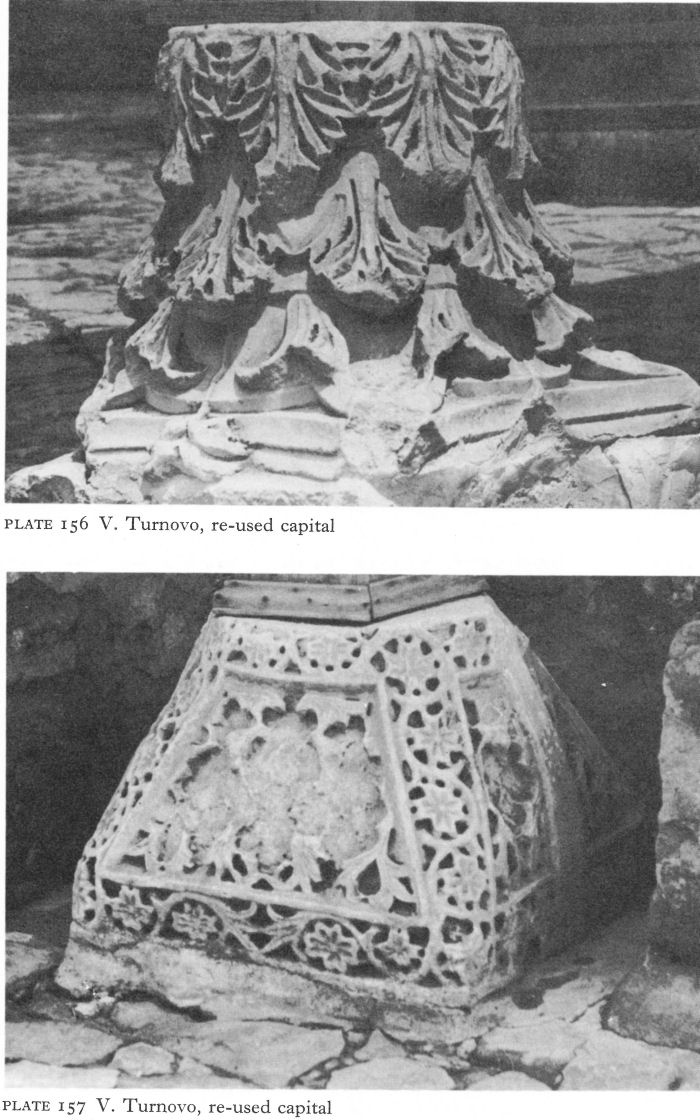

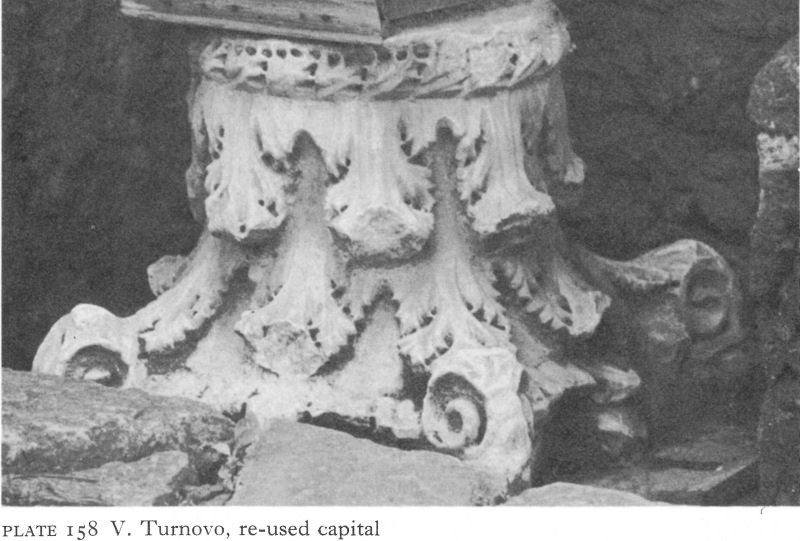

Elsewhere below the palace complex was a small single-naved church attached to a cruciform building with a common portico (Fig. 60). Limestone slabs paved part of the floors of both buildings, but there were also remains of tiling. A colonnade on the west of the portico had unequally spaced columns linked by limestone slabs; one intact column, 2 metres high, was discovered with its base in situ on beaten earth. A Corinthian capital was also found, similar to one of several re-used as bases for a wooden portico when the thirteenth-century church of the Forty Martyrs, below the fortress, was converted into a mosque (Pls. 156-8). The cruciform building has a small two-chambered crypt in its partly destroyed eastern part. The excavator dates it and its annexed church to the sixth century and first half of the seventh; he considers it too large for a martyrium, suggesting some connection with other rooms to the south. Nevertheless, on present evidence it is difficult to see it other than as a shrine, built perhaps to house threatened relics from further north.

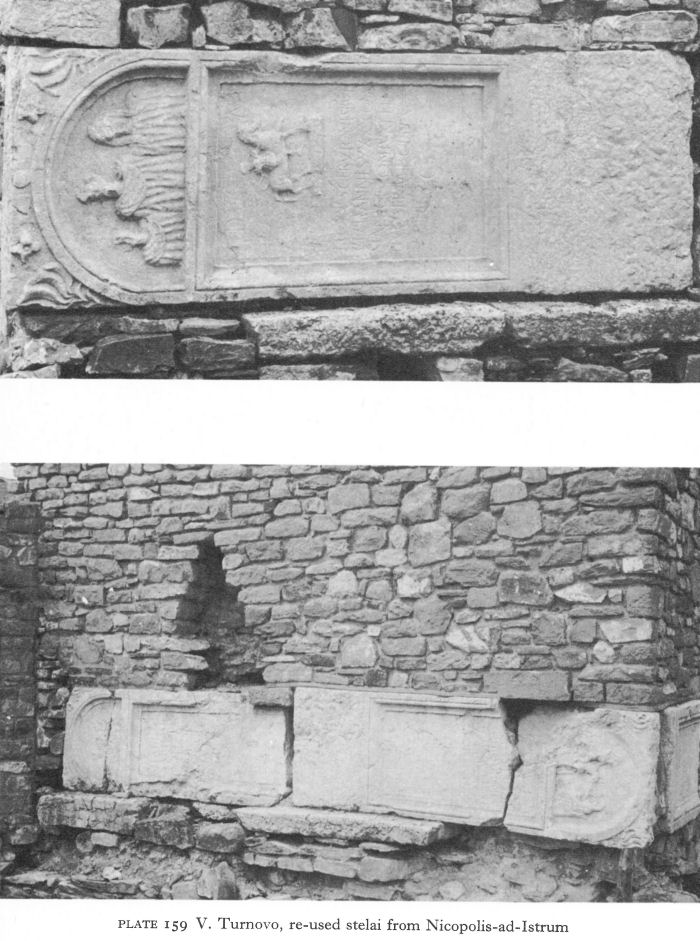

The distance between Nicopolis and Turnovo is only 18 kilometres, close enough for the population to move without difficulty, given time, and bring their household goods and chattels. Nicopolis was even used as a quarry. Three secondand third-century stelai of Hotnitsa limestone, all depicting a Thracian Horseman, and the base of a statue bearing an inscription from the boule and demos of Nicopolis form part of the socle of a tower of the medieval palace (Pl. 159). In this proximity may be an explanation for the continued existence of the bishopric of Nicopolis into the sixth century. The new city may have been regarded as the official successor of the old, retaining, for a while at least, its ancient name and, in so far as was possible, its administrative functions.

![]()

251

Fig. 59 (above right) Veliko Turnovo, superimposed churches

Fig. 60 (below right) Veliko Turnovo, church and cruciform building

![]()

252

Plate 156 V. Turnovo, re-used capital

Plate 157 V. Turnovo, re-used capital

![]()

253

Plate 158 V. Turnovo, re-used capital

Discoduratera

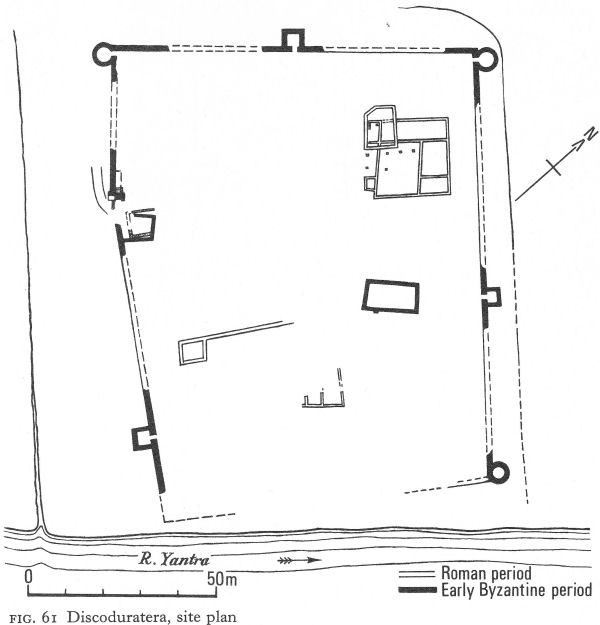

The intrinsic importance of Discoduratera as a trading post on the Beroe-Novae highway persisted as long as traffic continued to pass through it. The merchants returned after the Visigothic wars. Flimsier buildings replaced the porticoed house and its contemporaries, but the outer walls were rebuilt and strengthened. Except where eroded on the south-east by the river Yantra they have survived up to about 1 metre high, through the fortunate chance that they have served as boundaries between peasant properties.

The fortifications took good account of natural advantages. A steep bank down to the Yantra on the south-east, a deep valley to the south-west, marshes to the north-east; only the north-west side was easy of access and here traces of a ditch were found. There were four walls of unequal length, the only gate being on the south-west. External round towers defended the three surviving corners and doubtless the fourth, and single external four-sided towers reinforced each wall (Fig. 61). But Roman precision was gone. The angle towers projected to protect only one, not two, walls, almost as if the builder had heard that round towers were right for corners without understanding why. Yet, although irregular in shape and size, like the rectangular towers they were strongly built. The north tower, partly preserved up to a height of 2.20 metres, is topped by two courses of brick, the remains of a bonding layer.

The much-destroyed gate had inner and outer double swing doors. The openings were over 2 metres wide, large enough to take vehicles, and the propugnaculum about 2 1/2 metres deep. An originally square and free-standing watchtower east of the gate was burnt down and replaced by a rectangular one, built against the outer wall.

![]()

254

Plate 159 V. Turnovo, re-used stelai from Nicopolis-ad-Istrum

![]()

255

Fig. 61 Discoduratera, site plan

Coins of the end of the fourth century and the first quarter of the fifth are much more numerous than those of earlier periods, but also more worn. This points to a decline in local minting and to inflation, due to the general insecurity and impoverishment. The latest coins are of Arcadius and the Western emperor Honorius.

Sixth-century pottery found inside the walls suggests some continuity after the Hun invasion, perhaps even a revival under Justinian, but the emporium - if such it still was - is unlikely to have outlived him and was finally destroyed by fire.

Storgosia

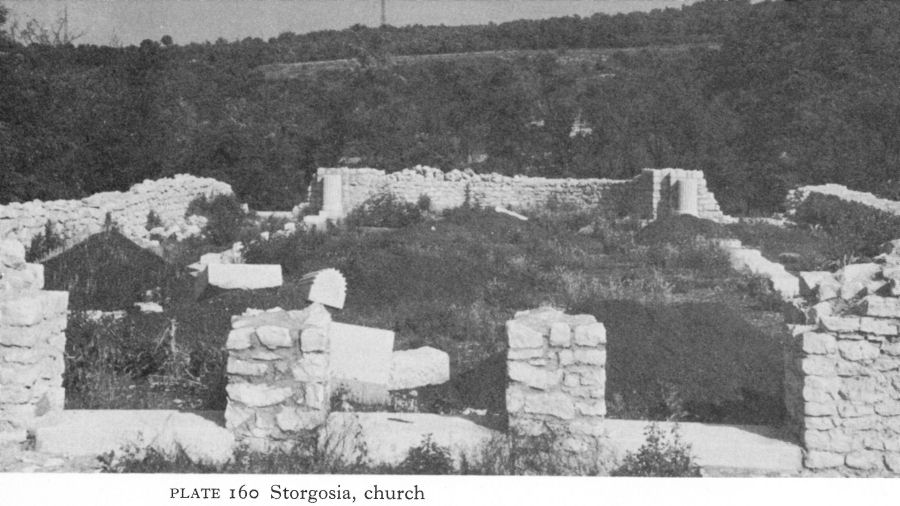

Storgosia (the ‘Kailuka’ gorge near Pleven) is one of the Roman sites which, though less than 50 kilometres from the Danube, now increased in importance owing to its strong natural defences. Such remnants of fortress walls as can be seen today are medieval, but inside them substantial remains of a large Early Byzantine three-naved church, 45 metres long and 28 metres wide, were discovered in 1909 and have now been conserved and partly restored (Pl. 160).

![]()

256

Plate 160 Storgosia, church

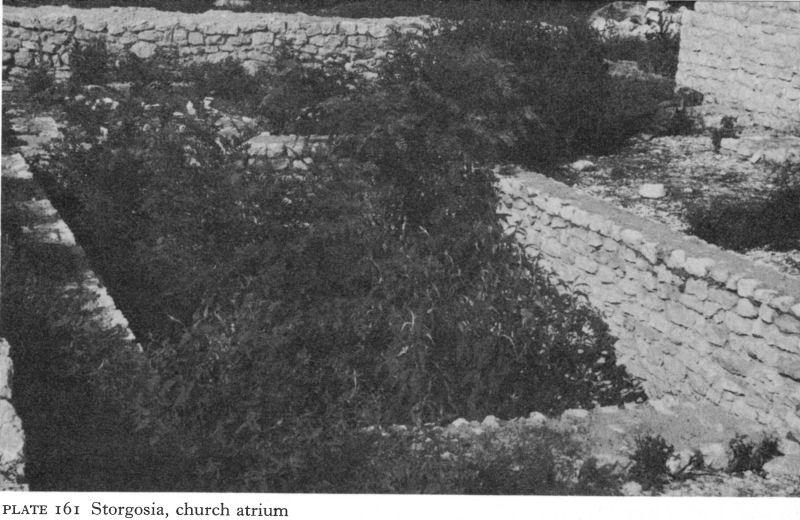

The excavator commented on the unusually wide and thick-walled central apse compared with those terminating the north and south aisles. The impression is given of a single-naved church of the fifth century to which side-apses were later added. A large masonry-lined pit, presumably a pool, of the type found in the sixth-century Episcopal church at Caričin Grad in Serbia, occupied much of the atrium, its edge being so close to the west wall as to preclude entry from this direction (Pl. 161). Not only is this one of the largest Early Byzantine basilicas in Bulgaria, but one with unusual architectural features; it is hoped that the conservation will be followed by new and fuller publication.

A smaller building, thought to be a fourthor early fifth-century church, was found at the foot of the cliff, partly eroded by the river. It seems to have been oriented towards a southern apse. Remains of a mosaic floor, no longer in situ, included intricate geometric designs, fragments of a Latin inscription, and the Constantinian labarum, or standard with the sacred monogram of Christ.

A short distance up the little valley, in a building that was possibly a villa of the Roman period, an octagonal structure contained, in addition to some ten human skeletons, 26 bronze coins of Justinian, testifying to Byzantine occupancy until about the middle of the sixth century.

Sadovets

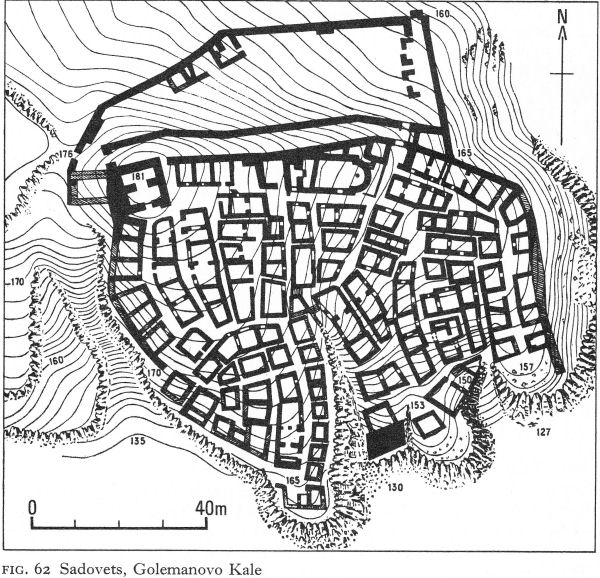

Near Sadovets, south-west of Pleven, the hill-plateau of the Golemanovo Kale overlooks the river Vit in a situation very similar to that of the Kailuka. Inhabited during the Roman period, after destruction in the third or fourth century, it seems to have remained deserted throughout the fifth century and the early part of the sixth.

Coins of Justinian help to date resettlement and the impressive defences (Fig. 62). The southern curve fell vertically from a height of 50 to 70 metres to the river, but the more accessible northern approach was defended by a triple wall. Burnt down once and immediately rebuilt, the fortress survived until its reduction by the Avars about the end of the sixth century, which was followed by permanent abandonment.

![]()

257

Plate 161 Storgosia, church atrium

Fig. 62 Sadovets, Golemanovo Kale

![]()

258

The keystone of the defence system was a strongly built tower about 11 metres square which, with a western bastion, occupied the highest, north-western sector. From here three walls, built on a steep slope, itself a deterrent, extended to a fortified section of the east cliff. Entrances, at the eastern and western ends, were only 1.70 metres wide. The walls, with no foundations and 1 1/2 to 2 metres thick, were built of small rough limestone blocks with a filling of rubble and white mortar, the latter also being used to plaster the outer faces. Brick was not used at all.

Behind the triple walls densely packed groups of dwellings, roughly built of limestone bound with mud, were separated by narrow alleys. Many houses had two rooms; one was found with a flimsy upper storey. I. Velkov suggests that one room served as living quarters and the other as a stable or byre, with perhaps a barn overhead for grain or fodder. Elsewhere there were separate rows of individual storerooms. Some people lived on an open terrace below the west wall.

Remains of two churches were found, both single-naved, with rounded apses, one on the terrace, the other in the fortress. The latter was oddly placed, its north-western part against the inner north wall, which cut into it at a slant. It was built on such a steep slope that the interior was on three different levels. The west wall of the church abutted on to an internally projecting tower, so that the main entrance had to be at the west end of the south wall. Much of the altar table was in situ; built of stucco-plastered masonry, its hollow interior must have contained relics. The conch of the apse was of unbaked bricks, but the roof is thought to have been a wooden barrel-vault. The building’s anomalies suggest that the inconvenient site was particularly hallowed.

Sadovsko Kale, a nearby fortified settlement on the other side of the Vit, possessed similar types of dwellings and a large workshop making agricultural tools which must have served the surrounding countryside. Both settlements show signs of wealth incongruous with the rough, huddled dwellings, although these had glazed windows. Silver ornaments, including Gothic-type fibulae, were found, and a remarkable number of coins. V. Velkov states that Sadovsko Kale holds first place in the whole of northern Bulgaria for coins of the late antique period. [4] Fifth-century gold coins - of Arcadius and Honorius - numbered only nineteen, but finds of sixth-century coins included: in one building, 54 gold and 50 copper coins; in a clay pot, 128 gold coins; by a wall, 12 gold coins; in a living room, 162 copper coins. The coins were in such good condition that they suggest direct official payments which never went into general circulation.

I. Velkov and G. Bersu have put forward the interesting theory that Gothic foederati were settled here by Justinian as part of the defence system as well as a repopulation measure. Other settlements in the area await excavation and may confirm this hypothesis.

Vicus Trullensium

The natural fortress of Vicus Trullensium (near Kunino), guarding the entrance to an Iskur gorge through which ran the Oescus-Serdica road, has not been excavated, but inscriptions have identified it. One, on an altar dedicated to Jove, was found in the local church, turned upside down to serve as the altar. The vicus cannot have survived the thirdand fourth-century raids,

![]()

259

but the insecurity of the latter half of the fifth century is likely to have increased the importance of so strategic a site. Earlier fortifications were restored and a double wall built to protect the easy, east approach. Perhaps because of a local tradition of stone masonry, defences were not skimped; walls, whether new or repaired, were up to 2 metres thick. Inside them were remains of a sixth-century single-naved church. The vicus was probably finally destroyed by the Avars, although the Slavs seem to have settled for a time in the ruins before abandoning them for the present site of the village of Kunino.

II. THE NORTH-EAST

A number of sites of strategic importance in the fourth century, but more particularly the fifth and sixth centuries, have been found in a shallow crescent-shaped area, roughly centred on Shoumen, in the hilly country about half-way between Abritus and Marcianopolis. Outposts of the latter, these and other fortresses constituted part of the defence in depth protecting the easy routes across the eastern end of the Stara Planina to Constantinople. In several cases, only a few details have been published in archaeological journals; and thus little more than their existence can be recorded. Nevertheless, the various sites are beginning to compose a coherent pattern illuminating the Byzantine defence strategy of the fifth and sixth centuries. Some of these are described below.

Abritus

The fourth-century town house in the centre of Abritus seems to have remained intact until about the end of the sixth, perhaps an indication that Abritus was occupied peacefully by the Ostrogoths under Theodoric. Two Early Byzantine churches have been located. A. Yavashov found the narthex and west end of the nave and two aisles of one, and a recent salvage dig has uncovered its apse, but finds, which include a marble reliquary, have still to be published. The second church, dated to the fifth century, seems originally to have consisted of a single vaulted nave with a round apse and perhaps also a narthex, but to have had later additions.

Procopius mentions Abritus as one of the fortresses restored or strengthened by Justinian. Either at this time or after further damage the north and south gates were walled up (Figs. 30, 31), leaving the battered west gate as the only entrance. The city was burnt by the Avars or Slavs about the close of the sixth century. Probably the inhabitants had had time to remove themselves and their valuables, for the only skeleton found was of a dog, trapped in the town house’s peristyled courtyard. Before long a group of Slavs settled among the ruins.

Voivoda

In the late fourth century Voivoda was severely damaged by the Visigoths, Following this, current excavations have shown that the north-west gateway was strengthened by a new wall (Fig. 33). This began at the angle tower and ran outside the western U-shaped tower. It incorporated a new outer gate, with two pivoted wings; in a guardroom to its south small copper coins of Theodosius, Marcian, and Leo I were found. The old outer - and now inner - gate, which showed signs of a conflagration, was also strengthened, but neither here nor in the walls did the workmanship approach that of the original structure.

![]()

260

Fig. 63 Madara, fortress and detail of gate tower

Layers of ash and charred material suggest that Voivoda also suffered from many of the later Avar and Slav invasions. The last coins found were of Justin II, indicating its existence into the second half of the sixth century. But finally the fortress was taken and razed. Among the ruins Slav pottery and what the excavators have described as ‘early medieval’ dugouts have been found, suggesting that it was probably soon reoccupied, but by the invaders.

Pliska

Ten kilometres south of Voivoda, with the crow flying over gently rolling country, is Pliska, the site of the first Bulgarian capital. Much excavated and restored since its first identification by K. Škorpil, this vast settlement with its outer city and its inner palace-citadel has been the subject of considerable controversy. Generally, Bulgarian archaeologists have considered it to have been built on virgin soil and any earlier materials, including some bricks bearing the ‘Dules’ stamps, to have been brought from Voivoda or elsewhere for re-use in the new city, but some scholars favour a Roman or Byzantine substratum. Resemblances in the plan of the fortifications of the walled inner city to those of the Justinianic period are clear, but this model must have been available for copying all over the Balkans, and in any case the Bulgars probably used Byzantine builders. Controversy centres also around two churches, one the ‘Palatine church’ inside the walls, the other a huge basilica outside the walled city. Both were certainly used by the Christianised Bulgars; current excavations should decide whether they were also sites of earlier churches.

There can be no doubt that most of the monumental inner complex of Pliska was of eighth-tenth-century construction, but insufficient evidence is available to show whether or not some fifth-sixth-century fort or earlier villa rustica had previously existed there. The site itself, in the middle of a flat, open plain, is more typically Bulgarian or Roman than Early Byzantine and far from fulfilling the usual desideratum in the latter period of a natural defensive position.

![]()

261

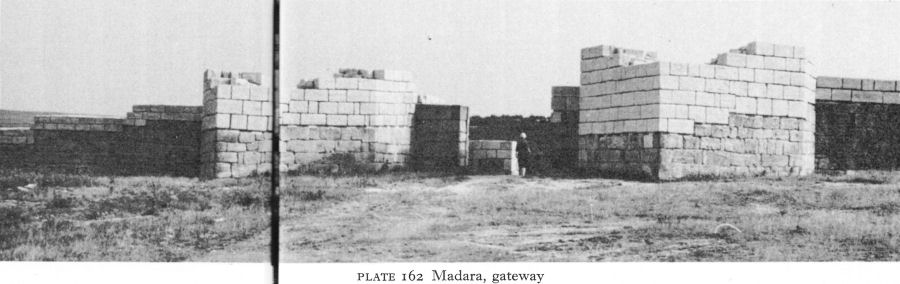

Plate 162 Madara, gateway

Madara

At Madara, about 12 kilometres south of Pliska, the big villa rustica had probably been razed by the Visigoths, but it did not remain deserted. A new complex with five rooms, two exedrae, and heating, all suggesting a baths, was built on the ruins of the wall which had surrounded the pars urbana (Fig. 34). The general plan, the coins, and pottery associated with it date the building to the end of the fourth or the fifth century, but there are signs of habitation until the early sixth, although whether connected with the fort above or with peasants squatting among the ruins is hard to say.

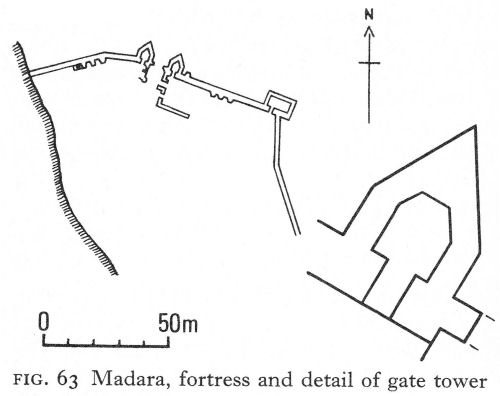

The great cliffs which rise precipitously above the villa are surmounted by a plateau. On its edge, probably in the late fifth or early sixth century, a fortress was constructed (Fig. 63). The sheer cliff on which it stood obviated the need for any walls on the west, and ravines gave some protection on the east and south-east. Only on the north did the open plateau offer no obstruction. This side was defended by a 2.60-metre-thick wall, almost 100 metres long with a projecting rectangular tower at the angle with the east wall. In the centre of the north wall, the fortress gate, flanked by two pentagonal towers (Pl. 162), consisted of an outer portcullis flush with the wall and inner swing doors, with a guardhouse inside. There are remains of several staircases against the inside of the wall.

Almost at the foot of the cliffs a great shallow cave, which had previously been a nymphaeum, was now an auxiliary base, linked to the fort by a staircase of some 400 steps cut in the vertical face of the rock, taking advantage where possible of fissures. Erosion has rendered the route impracticable today. Suitably fortified and itself some way above the plain, the cave provided the garrison with food and water and probably also served as a refuge for the local population and their livestock. Close by in a well-built granary were 11 huge clay dolia, each above a man’s height. Finds showed the granary was in use during the fifth and sixth centuries. Madara was an early and very important Bulgar centre, but there is no evidence when and how Byzantine occupation ceased.

![]()

262

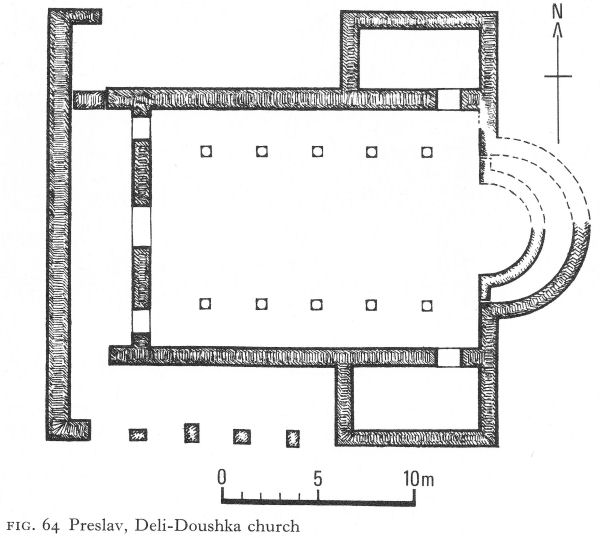

Fig. 64 Preslav, Deli-Doushka church Shoumen

Shoumen

West of Madara is Shoumen, the administrative centre of the region. On a terrace of the high hills dominating the city on the west and looking east and north towards Madara, Pliska, and Voivoda, excavations of a medieval fortress have uncovered some of its earlier history. The preliminary indications are that triangular towers flanked the main entrance to the fortress and were also found at intervals along the curtain wall above older structures. The second - or Early Bulgar - phase is considered to be a restoration of the fourthto sixthcentury structure. Traces of burning everywhere testify to the stormy life led by this fortress.

Long used as a quarry for later buildings, those of earlier periods are naturally much destroyed. However, a large date antique’ complex has recently been discovered and to its west at least three superimposed churches. The earliest, with an overall length of only 10 metres, was single-naved, the walls terminating in a semicircular apse. Only foundations of the western half remained; on the east the superstructure indicated a primitive broken-stone and mud construction, the apse being slightly better built. The simple nature of the building suggests a date in the second half of the fourth century.

Preslav

At Preslav, about 20 kilometres south-west of Shoumen, evidence of late

![]()

263

antique settlement is obscured by the monumental buildings erected when it was the Bulgar capital in the ninth and tenth centuries, and by their subsequent destruction. K. Škorpil, the first excavator of Preslav, said that most of the Roman coins found in the ruins were of the fourth century and that the Early Byzantine period was chiefly represented by those of Justinian, Justin I, and Anastasius. [5]

An exception exists east of the main site, by the Ticha river, at Deli-Doushka, where a fifth-century basilical church has been excavated (Fig. 64). The walls were of mortared uncut stone, with occasional use of dressed blocks to line the entrances; the roof was probably wooden. The wide central nave was separated by rows of five pillars from side-aisles only 2 metres wide. A large single apse corresponded to the width of the nave and contained remains of a synthronon. At the west end three openings led into a narthex, or vestibule possessing liturgical functions. Two rectangular pastophoria or side chambers, entered from the east ends of the two aisles, are of special interest as they must have served as the prothesis and the diaconicon, rooms designed respectively for the preparation of the Eucharist and as a vestry or sacristy in the Eastern Orthodox rite. Coins date the church to the first half of the fifth century, more than a hundred years before the Orthodox rites of oriental, particularly Syrian, origin found official recognition in Constantinople, a fact suggesting strong Eastern influence among the local population, a proportion of whom may have been immigrants.

Preslav is situated where the river Ticha emerges from a gorge into a fertile plain. On a hill commanding the entrance to the gorge, Early Byzantine potsherds were found among the ruins of a Bulgar fort which, roughly oval in shape, had one square and one round tower. It was concluded that this site - an obvious choice - had been fortified in the fifth or the first half of the sixth century.

Draganovets

On a tributary of the Ticha river some 15 kilometres south-west of Preslav, a rescue dig recently uncovered a fortress provisionally dated from the mid-third century to the end of the sixth.

Partial excavation of a church dated to the fifth or sixth century showed a long apsed room annexed to the south side of a three-naved, single-apsed basilica. The excavators’ suggestion of the possibility of a five-naved basilica must be regarded as tentative until more information is available. Stone and mud walls of an earlier building were found beneath the church and were identified by finds of marble votive reliefs as a sanctuary of the Thracian Horseman. A double furnace for brick-making, dated to the fourth or fifth century, was also excavated.

Krumovo Kale

At the western end of the Preslav hills, near Turgovishte, a fort known as Krumovo Kale defended the northern end of a pass and commanded a wide view towards Abritus. Enclosing an area of about 15-20 dekas (dekars?), the walls, 2.50 to 2.80 metres thick and still standing up to 3.50 metres high, were built of stones laid in regular courses and a fill of rubble and mortar. Remains of mortar over the stones, with incised vertical and horizontal lines, gave an impression of dressed stonework. The single gate, facing the only easy approach, was 3.70 metres wide and the depth of the curtain wall; it had pivoted wing doors and finds of wedge-shaped bricks show that it was vaulted. U-shaped towers defended the

![]()

264

gate, the south one being 6.80 metres wide and projecting perpendicularly 5.30 metres beyond the wall. The northern, almost identical in size, was angled away from the gate towards the saddle on which the access road is still visible. Both towers were constructionally linked to the wall and remains of stairs suggest an original height of about 12 metres.

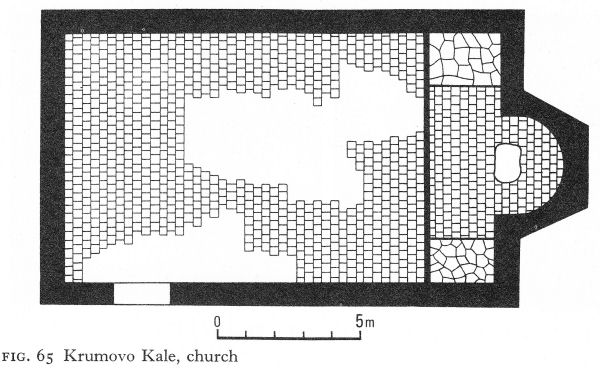

Excavation showed two building phases, both within the Early Byzantine period. Although the plan remained the same, in the second the stonework was much less skilful; there was no longer an attempt at regular courses and large limestone slabs were re-used in the gateway. The U-shaped towers - inferior in size and construction to those of Abritus and Voivoda - suggest a date about the mid-fifth century for their construction. As the culture layer is very thin, the first destroyers may have been the Ostrogoths. Restoration followed quickly, probably in the first half of the sixth century. Supporting evidence comes from the remains of a three-naved church only 2-3 metres inside the walls and closely related to them. The second phase of the church is well dated by coins of Justinian. At this period the church, 28 metres long and almost 16 metres wide, had a single apse, its exterior five-sided and containing a concentric ambulatory behind a synthronon. Columns on stylobates separated the nave and aisles, and the narthex was undivided. Since this church has not been published in any detail, it can only be assumed that, like the walls the second phase was more or less a reconstruction of the first, with a possible remodelling of the apse.

North of the walls fortified outposts served as observation points. Round these a civilian settlement grew up, probably for craftsmen and small traders. It included a single-naved church on the edge of a cliff about 300 metres north of the walls (Fig. 65). The lower parts of its walls were of broken sandstone, the upper of mud brick, probably reinforced by a wooden frame. The sanctuary, an adaptation of the Hellenistic basilica to the Eastern rites which required pastophoria, comprised the apse and 2 1/2 metres of the east end of the nave, partitioned into three and slightly higher than the rest of the church. Because of the steep drop outside, there was no narthex and the entrance was by the west end of the south wall. The church was paved with irregular sandstone blocks in the pastophoria and re-used tiles elsewhere.

Evidence from the walls suggests that this church had also been rebuilt after severe destruction; a chronology according generally with that of the fort seems likely. Coin finds suggest that Krumovo Kale survived well into the second half of the sixth century.

Tsar Krum

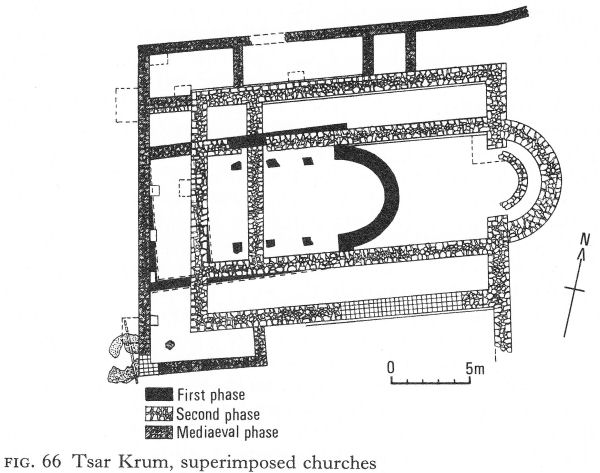

Near the village of Tsar Krum, 10 kilometres south-west of Shoumen and on a slight rise 2 kilometres from the river Kamchiya, excavation of a ninth-century Bulgar fortress unexpectedly uncovered three Early Byzantine churches. Two, superimposed, are just inside the north wall of the fortress, the third a short way away to the south-west.

The lower of the superimposed churches, destroyed by fire and much of its material re-used in the one above, was a small basilica only 9 metres long (Fig. 66). The ovoid apse contained a single-stepped synthronon. The nave was flanked by stylobates, each with three pillars, leaving ‘aisles’ no more than half a metre wide. The narthex, severely damaged, appears to be undivided.

![]()

265

Fig. 65 Krumovo Kale, church

Fig. 66 Tsar Krum, superimposed churches

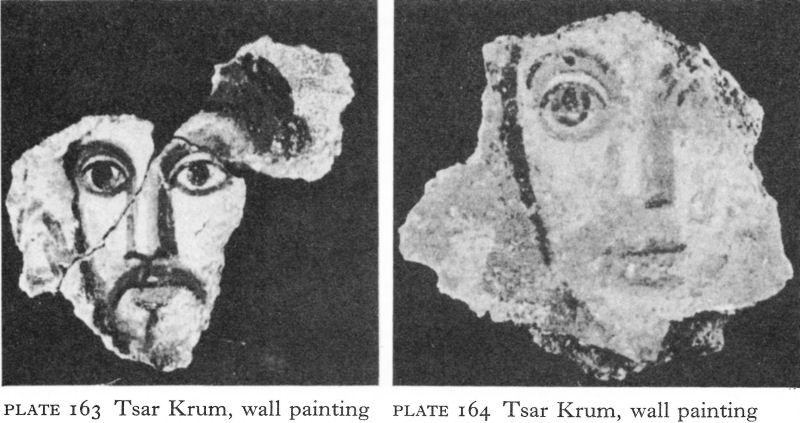

Tiles were found from the roof and the floor was brick. The plan of the church, its relationship with the one above - a depth of 1 metre between the two floor levels - and finds of ceramic and fourth-century bronze coins show this to be one of the earliest churches in Bulgaria. Fragments of wall paintings add to its especial interest.

Most of these fragments, some with three layers of paint, were in the 60-centimetre-thick debris that covered the floor of nave and apse, but others, apparently parts of panels, were in situ at the bases of the walls.

![]()

266

Plate 163 Tsar Krum, wall painting

Plate 164 Tsar Krum, wall painting

Most important were fragments of almost life-size human faces, two nearly complete and the fresh colours extraordinarily well preserved. One shows the head, turning slightly to his right, of a man, perhaps in his forties, with brown hair, a drooping moustache, and a short beard. His large eyes and his nose and mouth are firmly modelled with pinkish-orange and brown strokes. The background is blue and an acanthus leaf can be seen behind the right cheek (Pl. 163). The second head is of a younger, beardless man (Pl. 164).

It is hardly possible that more than fifty years divide these paintings from those in the tomb at Durostorum; they may even be contemporary. The colouring is somewhat similar, but spirit and techniques are quite different. The Durostorum figures are portrayed in a realistic, Roman manner. The spiritual quality of the Tsar Krum heads places them unquestionably in the full tradition of Byzantine sacred art. These recently discovered paintings are important examples of an art of which very little survives from this early period. Relationship with the Hellenistic East seems evident; there are certain resemblances with the earliest - fifth- to seventh-century - icons at Mount Sinai.

According to pottery and building remains, this church lasted until the late fourth century, when it may have been a casualty of the Visigothic wars. V. Antonova has tentatively placed its construction within the first half of the fourth century; it can scarcely be later, given the three identified layers of wall painting.

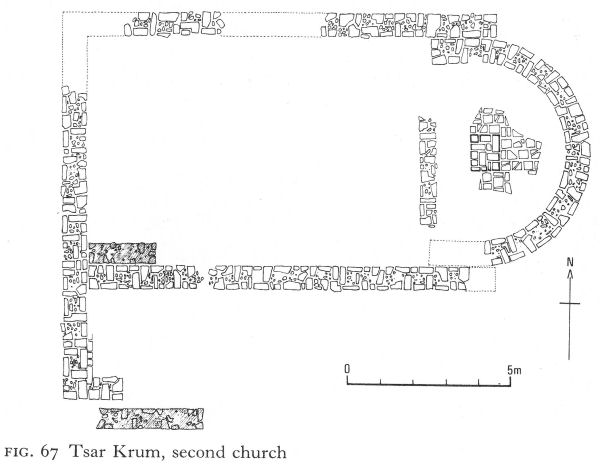

The second church to be built was the one a short distance away, a singlenaved basilica without a narthex (Fig. 67). The apse was unusual in that its slightly horseshoe-shaped ends - an Anatolian feature - extend 2 metres within and alongside the walls of the nave, perhaps to buttress the vault of the apse. The base of an altar screen was found at the beginning of the apse but did not extend across it; the stone base of an altar table stood in the centre of the sanctuary. The floor was of old, often broken, tiles, laid directly on the earth. The west wall continued south and then turned eastward at a right angle, a feature also found in the Deli-Doushka church. It suggests a wooden portico and this is made more

![]()

267

likely by the presence of a south doorway inlo the church. The roof was tiled on a wooden framework. The general plan, pottery finds, and coins of Constantius and Honorius assign this church to the late fourth or early fifth century.

The third church was on top of the first, on almost the same axis (Fig. 66). Although much larger, it was similarly planned, with a relatively wide nave in proportion to the aisles. Its semicircular apse contained a single-stepped synthronon. The nave and aisles were divided by stylobates, but all the columns had been removed. The outer walls, preserved in places up to 1.40 metres, were 1.30 metres thick. A southern extension of the east wall may have been needed as a buttress or been the enclosing wall of a portico. A bonding layer of three courses of yellow brick was found above the stone masonry at one point. The narthex was tripartite, corresponding to the nave and aisles. This essentially Hellenistic basilica is elongated compared with the Deli-Doushka church and lacks its side-chambers. Both churches, as well as the one below, reflect the variety of influences in this region in the fifth century, to which this last church must be dated. The contrast with those at Iatrus is strong.

Although damaged, the stout walls of the third church survived the Slav settlement and even incorporation into the fortress of the pagan Bulgar ruler Omurtag. Its cult purpose was either remembered or later recognised, for towards the end of the ninth or in the tenth century it was restored and enlarged by Christians in the first Bulgar state.

Marcianopolis

Marcianopolis withstood the Visigoths, but their devastations of the surrounding countryside caused the city to undergo a period of decline, reflected in constructions attributed to the late fourth and fifth centuries.

Fig. 67 Tsar Krum, second church

![]()

268

Nevertheless, the state munitions factory is believed to have continued to function until at least the mid-fifth century, and a pottery for making Christian lamps is also dated to this time. The only early - late fourth- or early fifth-century - church so far identified is single-naved with a mosaic floor, although Marcianopolis was an archiepiscopal centre as well as the capital of Moesia Secunda. Two painted tombs from the necropolis with decorations that included garlands and doves may also belong to this period, which came to an end in 447 when the Huns captured and set fire to the city.

The city was to have a brief flowering in the sixth century. According to Procopius, its walls were restored by Justinian, and the remains of four churches have been attributed to this period. One, superimposed on the early single-naved basilica, was three-naved, with a narthex and a rectangular annex, believed to be a baptistery. The nave was separated from the aisles by marble columns, each with a cross carved in relief in the middle, crowned by acanthus capitals, one incorporating an eagle. In the nave, in front of the sanctuary, the mosaic floor was almost completely preserved. Using stone and ceramic tesserae of white, black, brown, orange, and yellow, zones of interlacing flanked geometrically patterned squares in kilim-like fashion.

In the arena of the destroyed amphitheatre another three-naved basilica was erected, using much of the old building material. Perhaps this site was chosen in commemoration of martyrs who had earlier met their deaths there.

So Marcianopolis, a strategic bulwark in the defence of Constantinople, enjoyed prosperity until the second half of the sixth century, when it was taken by the Avars, but probably more plundered than destroyed, since it is mentioned in 595 as a military base visited from Odessos by Peter, brother of Maurice.

The last mention of the archbishopric of Marcianopolis was in the seventh century, after which it seems to have been transferred for a short time to Odessos. The title was resurrected a thousand years later, when Pope Urban VII appointed one Marko Bandulević (perhaps a Bosnian) to the archiepiscopate of the Catholics in north-east Bulgaria and some lands beyond the Danube, and gave him the title of archbishop of Marcianopolis.

NOTES

1. NAC 1970, Arh XII/3, 81.

2. Miyatev, K., Arhitekturata v srednovekovna Bulgariya, Sofia, 1965, fig. 148.

3. BASEE I, 1969, 51, 52.

4. Velkov, V., Gradut v Trakiya i Dakiya prez kusnata antichnost, Sofia, 1959, 164.

5. Škorpil, K., in Bidgariya 1000 Godini, I, Sofia, 1930, 186.

12 Serdica and the West (II)

I. SERDICA AND THE CENTRAL REGION

The fourth-century extension of Serdica’s fortifications was probably destroyed by the Visigoths in the last quarter of the same century, and the fall of the city to Attila’s Huns in 441-42 put an end to any question of its reconstruction. Serdica was sacked and looted; the destruction was less severe than at Naissus, but at a meeting here in 449 between Byzantine and Hun envoys, the latter could still point to the surrounding devastation to illustrate their master’s power.

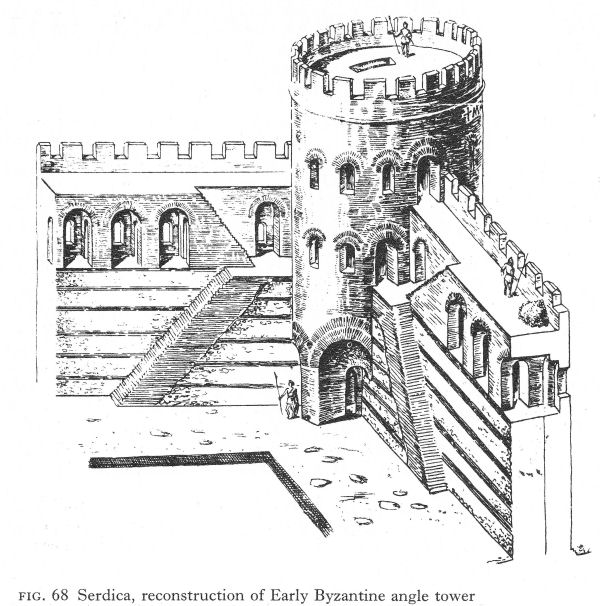

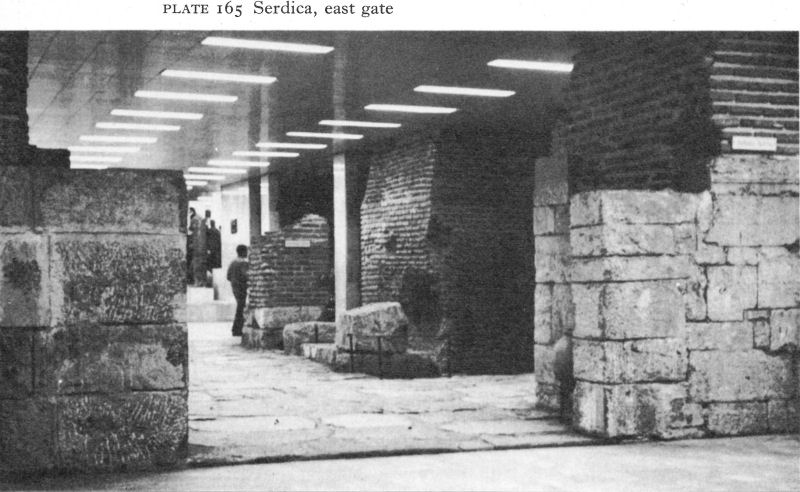

After Attila’s death, Serdica’s walls must have been hurriedly repaired - or else the city would have been defenceless during the ensuing Ostrogothic wars - but the original Aurelian plan was readopted and continued during the sixth century. Then or, it has been suggested, as early as the reigns of Marcian I or Leo I, a massive renovation of the city’s defences was part of the general refortification programme. A new wall was built along the whole outer face of the old one, the socle of which formed part of its base. Like the old wall, it was 2.15 metres thick, except on the south where it was 2.60 metres. The strength of the walls was thus doubled (Fig. 68). Although earlier rounded towers were incorporated in the new curtain wall, triangular and pentagonal towers were added, especially by the two gates, as can be seen by the east gate in the pedestrian underpass (Pl. 165).

There is no evidence how Serdica fared at the hands of the Avars and Slavs, but it appears to have remained in Byzantine hands, reappearing in history at the beginning of the ninth century, when the Bulgars captured it and dismantled the fortifications before retiring.

The insula east of the St George complex underwent little change. Sometime, what had probably been a pagan shrine in the form of an inscribed octagon was converted to Christianity and given a rounded eastern apse. A small single-naved basilica, also with a rounded apse, was attached to it.

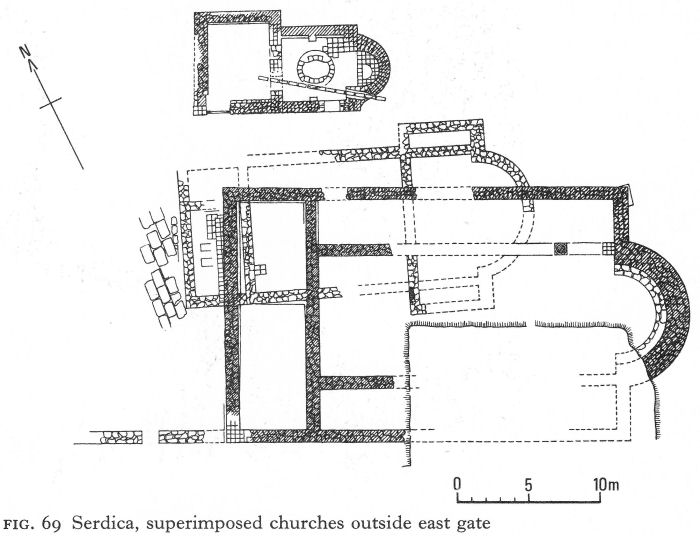

Outside the east gate were two churches, one above the other, a baptistery beside them (Fig. 69). The earlier church, single-naved but with pastophorialike annexes, an apse almost as wide as the nave, and a narthex where a fragment of geometric mural painting has survived, recalls Deli-Doushka. Dated to the fourth century, it was probably destroyed by the Visigoths. Its successor was an early fifth-century type of basilica with walls of opus mixtum, stylobates carrying colonnades, and a massive rounded apse with a single-stepped synthronon. The two-roomed baptistery, 2 1/2 metres from the earlier church and 5 metres from the later, was not precisely aligned with either. East of the piscina, which had three steps at either end, an apse had been bricked up to form a semicircular basin reaching down to the floor, perhaps some kind of stoup for holy water. Although fourth-century coins were found, the baptistery is considered on a variety of grounds to belong to the later church. [1]

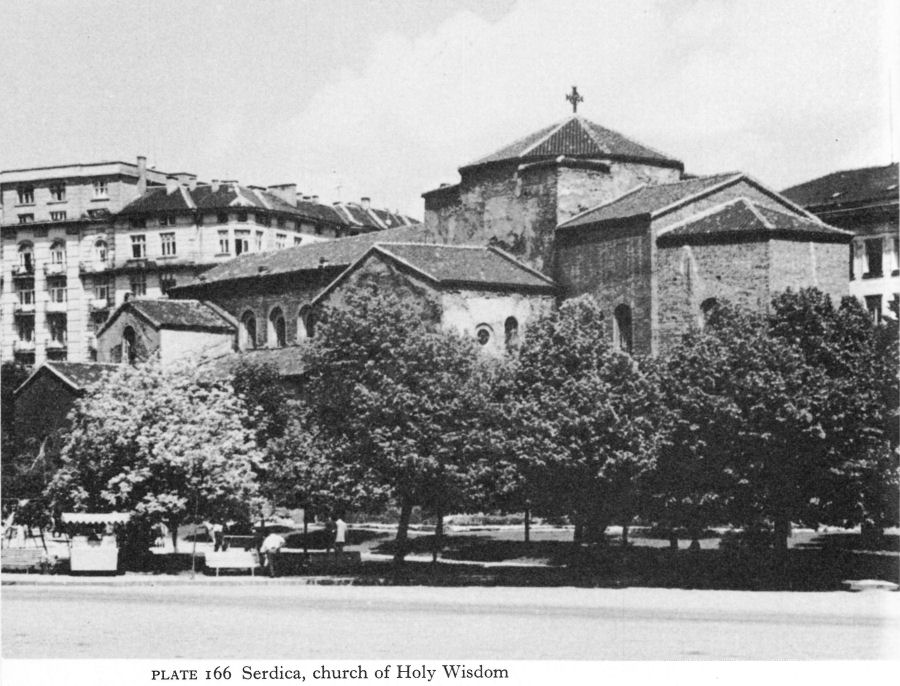

A few hundred metres away along the road to Philippopolis was the city’s main Early Byzantine necropolis, marked today by the church of the Holy Wisdom (Sophia), the fifth church to occupy the site (Pl. 166).

269

![]()

![]()

270

Fig. 68 Serdica, reconstruction of Early Byzantine angle tower

Plate 165 Serdica, east gate

![]()

271

Fig. 69 Serdica, superimposed churches outside east gate

Patched but dignified, this ancient basilica carries its years with a modesty in sharp contrast to the gleaming golden-domed nineteenth-century church of Alexander Nevski standing nearby.

Alongside third-century pagan graves, Christian burials began to take place here in the first half of the fourth century. A concentration, among them tombs with painted vaults, was found under and close to the church of Holy Wisdom, clearly intended to be as near the original church as possible. They are architecturally similar and have the same reddish-orange painted frames round the walls as the contemporary pagan one at Durostorum. Facing birds and tree motifs are common to the paintings of both, but in Serdica the lighted candles flank a labarum. On one vault poppies replace rural scenes.

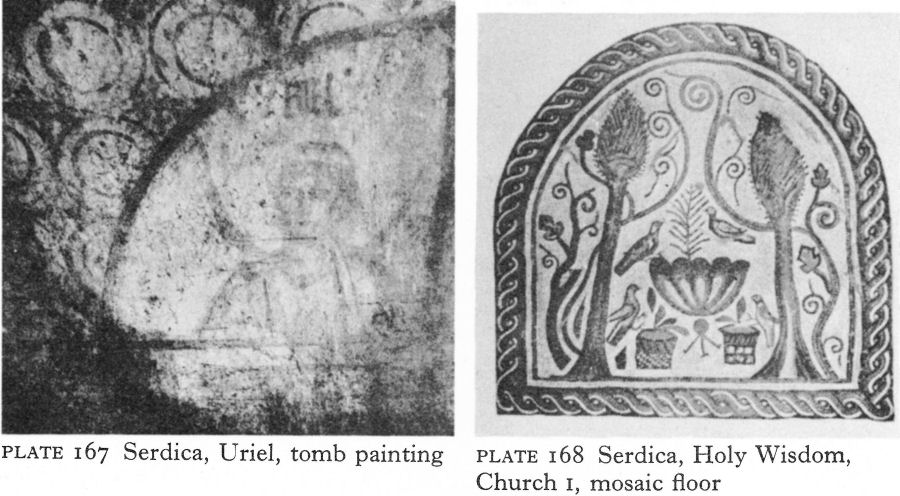

The finest painted tomb here was found in 1909. Brick built and vaulted with a north-south orientation, it had been looted and was badly damaged by damp. The walls were painted to imitate marble revetment. In the centre of the ceiling a green laurel wreath with white fruit enclosed a Latin cross in yellow ochre, outlined with pearls and with white rays radiating from its centre. Busts of the four archangels, named in Latin, occupied each angle of the long sides of the vault. Three were in a very poor condition and only Uriel was photographed before disintegration (Pl. 167). The excavators dated the paintings on stylistic grounds to the fifth or possibly sixth century, but Latin suggests the fourth, and the orientation of the tomb also argues for an earlier dating. [2]

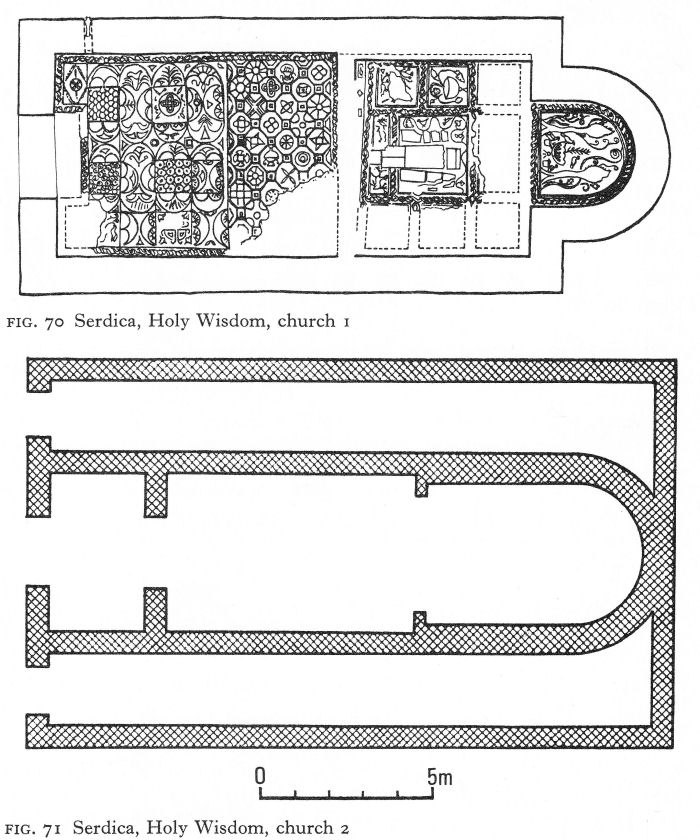

The first church on the site of Holy Wisdom (Fig. 70), single-naved with a rounded apse, occupied an area about 14 metres long and nearly six metres wide under the east part of the present church.

![]()

272

Plate 166 Serdica, church of Holy Wisdom

Plate 167 Serdica, Uriel, tomb painting

Plate 168 Serdica, Holy Wisdom, Church 1, mosaic floor

![]()

273

Fig. 70 Serdica, Holy Wisdom, church 1

Fig. 71 Serdica, Holy Wisdom, church 2

Only mortar foundations of its first pebble mosaic floor remain. The next floor was of multicoloured mosaic tesserae, divided into three zones and probably used during more than one building phase. In the centre of the apse zone, birds perched round a large fluted bowl, plant, and two baskets, were flanked by cypress-like trees and spiralling vines (Pl. 168). The next zone, occupying rather more than the eastern third of the nave, was square, its subdivisions containing such common symbols as the vine, ivy, lambs, and a peacock. Beyond, a single border enclosed the third zone, divided into two parts; the western had complex and luxuriant geometric patterns, with here and there a vase and once a bird, the more schematic and regular eastern part being considered a later repair.

![]()

274

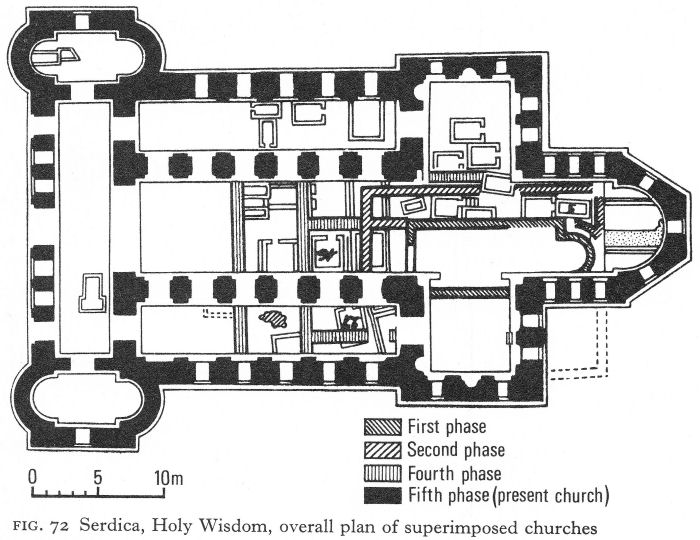

Fig. 72 Serdica, Holy Wisdom, overall plan of superimposed churches

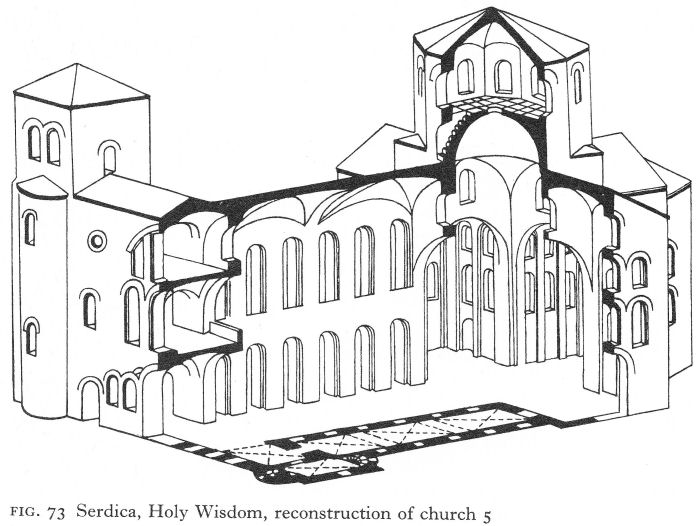

Fig. 73 Serdica, Holy Wisdom, reconstruction of church 5

![]()

275

The nave of the second church was built on the foundations of the first, but with two side-aisles to north and south extending to a new east wall which inscribed the apse, now as wide as the nave. A tripartite narthex was added (Fig. 71). The repaired part of the mosaic floor of the first church may have belonged to its successor or the whole floor may have been common to both buildings.

The third church widened the aisles and narthex of its predecessor; the few remains include new fragments of mosaic, also with geometric designs but using larger tesserae with less skill.

The fourth church (in B. Filov’s 1913 excavation report the second) is a puzzle, the first clue being the existence of a floor mosaic above the earlier levels. Including damaged areas, but without borders, which have entirely disappeared, this mosaic covered nearly 144 square metres and paved part of the nave. More was found at the same level in the south-east corner of the south transept. Here was perhaps the beginning of an edge to the floor. In 1913 the plan of the church was impossible to determine. The south aisle of the present building, then in use as a chapel, could not be excavated. Nevertheless, Filov suggested that two parallel north-south walls, running near or under the second and fourth piers (counting from the west), seemed to correspond to the narthex of a single building, and proposed that a similar wall between the north piers supporting the dome might be part of its north wall. The overall plan published after recent conservation (Fig. 72) supports these theories and suggests stylobates along the middle of the present nave and south aisle. Pending fuller publication, no further analysis is possible.

The fifth church, although mutilated by eventful centuries, is in essentials the one standing today. The building has been variously dated between the fifth and twelfth centuries, and described as influenced by Anatolian or Romanesque architecture, or even as having influenced the evolution of the Romanesque, the Crusaders acting as ‘carriers’ in either direction. Some of these theories may be due to the splendid soaring height of the nave which is a familiar sight to the Western eye.

Much larger and more solidly built than its predecessors, the new church was wholly brick. Beginning from the west, the ground plan consisted of an undivided narthex with north and south extensions, a nave and two aisles, a slightly protruding transept, and finally a short choir and an apse with a three-sided exterior. The total length was 46 1/2 metres, of which the nave and aisles occupied only 21 metres. In spatial terms, the church gives less the impression of a three-naved basilica than of a Latin cross with an architecturally integrated narthex and vaulted and galleried side-aisles.

The high vaulted nave is separated from the aisles by massive arched piers, five on each side, spaced only 1-70 metres apart. The openings from narthex and transept are little wider, establishing a great contrast between these relatively shut-in areas and the broad lofty space formed by the integral and apparently uninterrupted unit of the nave, transept, and choir-apse. Separation of aisles from nave is not at all unusual in fifth- and early sixth-century basilicas; but, where a trans ept exists, its arms are normally occupied by the prothesis and diaconicon.

![]()

276

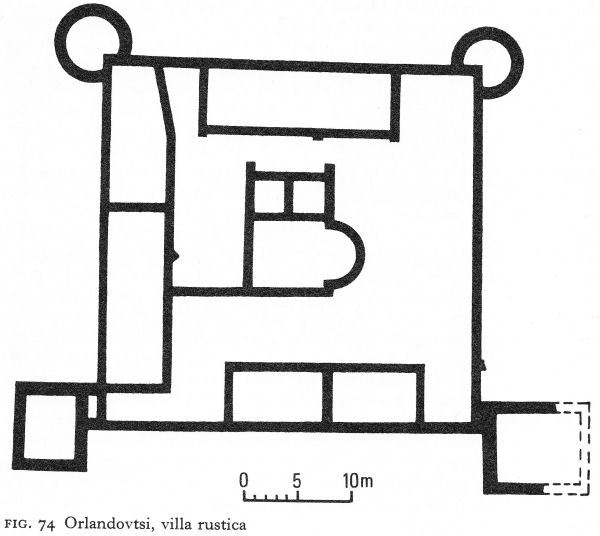

Fig. 74 Orlandovtsi, villa rustica

The plan shows that the transept did not serve this purpose here, consequently the sanctuary consisted of the choir and apse. The funerary church of Holy Wisdom thus provided a suitable position beneath the dome for the deceased during the burial service.

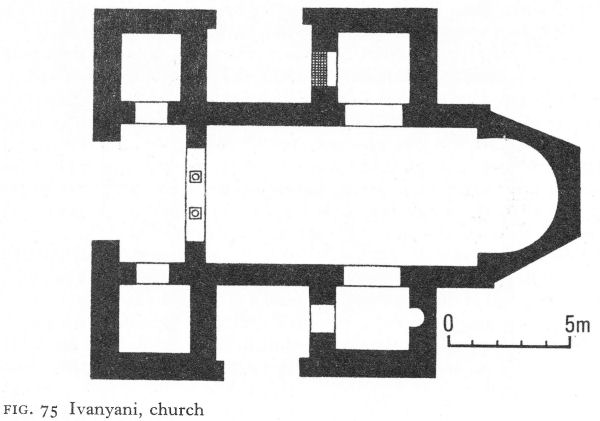

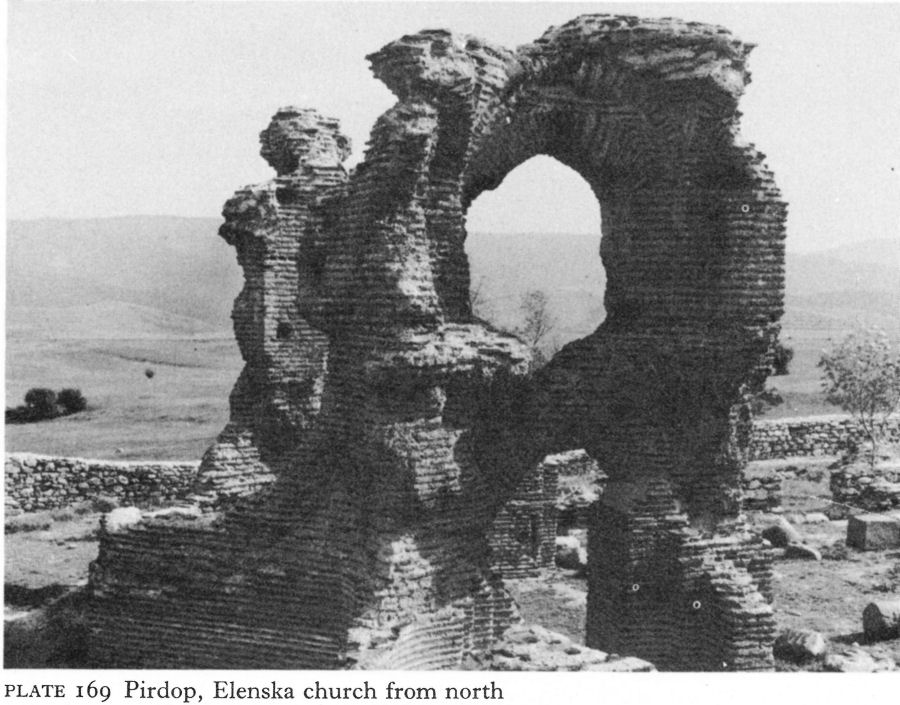

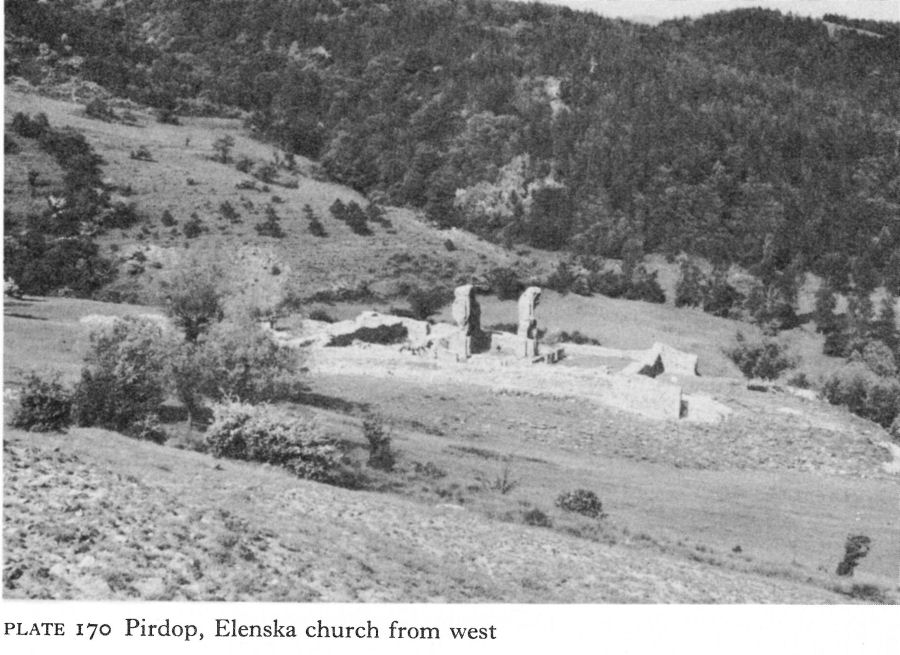

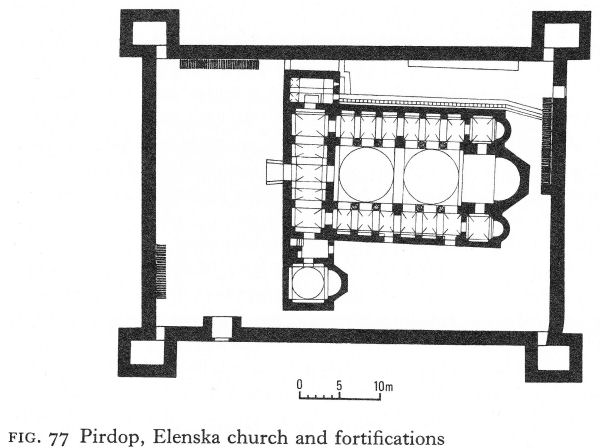

A similar plan was found in another funerary church nearby at Ivanyani. Analogous cruciform churches with a less clearly defined function have been excavated at Tsurkvishte, and at Caričin Grad in Serbia. [3] Possibly Botevo (p. 242) falls within this category. This plan was by no means the sole funerary type; probably of eastern Anatolian origin it occurs in the Balkans only in a relatively small area.

The Holy Wisdom stood, exposed, outside the walls on a site where at least four predecessors had been destroyed within two or three hundred years. There were many graves, perhaps some of martyrs, beneath the floor and the church itself must have contained much of spiritual and material value. Hence its solid construction, calculated to withstand minor raids. Galleries, perhaps for defence as much as for worship, were built above the narthex and transept as well as over the aisles. It is now believed that there was a second storey above the narthex and transept, and that the north and south extensions of the former carried towers (Fig. 83). Cross-groined vaults covered the transept arms and choir, and also formed the ceiling of the nave and aisles. The present dome,

![]()

277

supported on four piers, has no drum, but S. Boyadjiev has proposed that originally a dome on an octagonal drum rose in place of the one visible today. [4]

Finds of 23 coins, ranging from Licinius to Arcadius, between the upper and lower mosaic floors give some help in dating the earlier churches. The first may have been built soon after the Edicts of Toleration - not unlikely if martyrs had been buried there. Historically feasible periods of destruction are the reign of Julian the Apostate, the late fourth-century Visigothic war, and the sack of Serdica by the Huns in 441-42. Julian passed by in 361 on the road from Naissus to Constantinople, where he was proclaimed emperor; his supporters might have razed the church to gain favour. It was an easy target for Visigoths and Huns. Added to these possibilities were natural disasters, such as fires, to necessitate rebuilding, as well as a fashion for new and larger churches. All that can be said with reasonable certainty is that the first four churches were built between the first half of the fourth and the middle of the fifth centuries.

The late fifth century, after the Hun and Ostrogoth devastations, was an unpropitious time for building the present church. Such skilful brick construction - especially in an exposed situation - is most unlikely in the late sixth century, yet the influence of Justinian is not evident in the massive, though noble, simplicity of the interior. On the whole, the first quarter of the sixth century seems most probable.

Even if Serdica remained a Byzantine outpost until the ninth century, a church so far outside the walls is unlikely to have been kept in repair. There is some slight epigraphic evidence for restoration in the late tenth or the eleventh century. Yet its fame grew. A charter granted to the monastery of Dragalevtsi in 1382 refers to the ‘region of the Holy Sophia' and in the course of time Serdica, after being ‘Sredets’ to the Slavs, took the name of its most renowned church.

The necropolis had other churches. The foundations of a single-naved basilica with a round apse and a narthex, in all 16 metres long and 5.60 metres wide, were found 12 metres south of Holy Wisdom. Another, only partly excavated, lay to its west.

Orlandovtsi

The environs of Early Byzantine Serdica were not wholly cimiterial. Villae rusticae of the late fourth and fifth centuries have been uncovered, but the open aspect of more peaceful days has gone. An unusually fortified villa was found in 1935 at Orlandovtsi, 4 or 5 kilometres outside the city. The walls, preserved up to a metre high, formed a rectangle measuring 31 by 34 metres (Fig. 74). Two round angle towers projected at the north-west and north-east corners, whilst the south-west and south-east corners were defended by external rectangular towers. Built of local broken stone and mortar, the walls were 65 to 70 centimetres thick, except at the towers, where they approached 1 metre.

The site had been long under the plough so that, although the plan was clearly discernible, there were few finds in situ to help determine the interior arrangement. Rooms were annexed to the walls on all sides except the east. The west was completely occupied by a rough construction, divided into two parts, probably farm buildings. On the south were two smaller rooms, probably living quarters; they were better built and contained materials apparently brought from Serdica,

![]()

278

Fig. 75 Ivanyani, church

Fig. 76 Tsurkvishte, church

architectural and funerary stele fragments among them. Inside the north wall was a long, undivided room. The largest of a group of three rooms in the centre of the villa had an eastern apse and may have been a chapel.

Few coins were found, the earliest of Maximin Daza (305-13), and more and better-preserved examples from the reigns of Constantine, Constantius, and Theodosius II. On the basis of building techniques, pottery finds, and coins, the excavator dated the villa to about the end of the fourth century, when a chapel would be normal. During this troubled period defence must have been an

![]()

279

essential feature in any building plan, but the Huns probably destroyed it when they attacked Serdica. Similarly fortified villas are believed to have existed at Bistritsa, in the Dupnik area, and also at Radomir in the Chirpan region, but neither has been fully excavated; the Orlandovtsi villa is unique in Bulgaria in its unusual combination of round and square towers.

Ivanyani