IV. A WEEK OF WEDDINGS IN GALICHNIK

Fetching Water for the Parents for the Last Time 85

The Bride 89

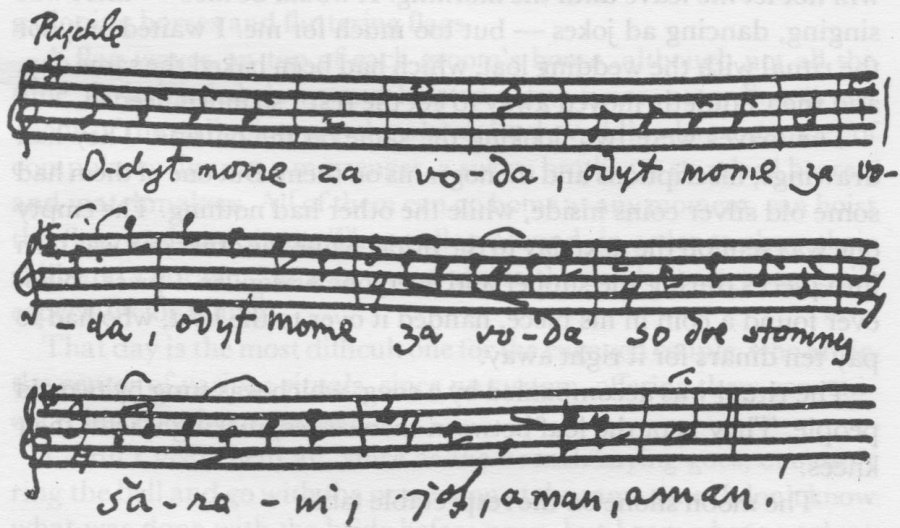

It was the greatest day of the year of Galichnik. And the longest one, as well. Twenty four hours were not enough for it. It started God knows how early, and only God knew how long it continued, since it meant, first of all, that those "on profit" had returned for a very short while, and secondly, that the period of the weddings had begun. The weddings here were made once a year, all at the same time, and each one needed a whole week for itself, both with its prologues and its epilogue. And all this was called St. Peter's day.

These were the best days of the year, the longest and the warmest. For Galichnik, where the last trees grew, it was quite important. There were no farms or gardens here. The high-spirited autumn, with the cheerful gathering of the corn, the wine harvest, and the songs was unknown here. The boisterous festivities, marking the end of the harvest else the farmers could calmly await the winter, were completely missing in Galichnik. Very soon, winds from all directions would start blowing and no one would be delighted by winter, not only because of the snow, which would isolate Galichnik for a long time, but also because winter always meant that the men, who couldn't earn their living here, would have to leave their families for at least a year, to return on some future St. Peter's day.

Maybe that was exactly why all the weddings were held at the same time. The reason was not just the rejoicing and sunny nature, but the coming home as well. Only as an exception could a wedding be held in September, on St. Illiya's day.

Of course, he who knows Galichnik's people, their enterprise and taste for carrying things off with verve, as rich factory owners, might think that the group marriage ceremonies were a result of them. But he would be mistaken. It was true that they had tough standards and

![]()

79

detailed prescripts both for the production of kashkaval (a type of yellow cheese) and for the celebration of their weddings. But economy was the goal only in the first case and not in the second. A man from Galichnik saved all his life, except at his wedding. It went on for a long time and cost more than 20,000 dinars (according to some the sum was as high as 100,000 dinars!). The suspicion that having all the wedding ceremonies at the same time was aimed at bringing down the number of guests was groundless, since they all lived as one family. The houses with weddings were transformed into common dining rooms and all, except the women whose husbands were away, could join the festivities.

The only profit made during the ceremonies was the priest's, but we could not reproach him, since he had to lead as many as forty couples from the low, stuffy church!

During our stay, St. Peter's day was on a Tuesday, and the wedding ceremonies were to be performed on Thursday, so we arrived earlier, on Sunday. But still, we hadn't come on time. The preliminary festivities had started on Thursday at the bridegroom's house, followed by a few different types of invitations. The bridegroom invited his in-laws personally "na stroi", i.e. on horseback; the bride's family invited "na voda" (for water), i.e. when the bride went for the last time to fetch water for her parents, and "na svakiu", i.e. for baking the wedding loaf of bread, which was used when the groom sent matchmakers to ask for the girl.

We received our first impressions of a wedding on Monday morning. We had gone out early and were captured by the town's panorama, which seemed to be collapsing in the precipice of the Galichnik river, all the way down to the Radika valley. The Korab mountain was sticking out behind it, to the west, together with the numerous Albanian mountains. We were comparing all this with our map, when suddenly the air was shaken by powerful blows that were magnified to an incredible roar by the echoing mountains. "Probably a passage from the overwhelming symphony on the World War, "Drumfire", would sound like that", I thought, and wasn't altogether wrong. "The drums have started beating" as a local folk song went. Gypsy orchestras from Kichevo, Gostivar, and Tetovo were playing in front of the houses of grooms, brides, and in-laws. They were composed only of two elements: two or three large drums and two or three oriental clarinets, called "zourla". The drums were beaten with

![]()

80

the greatest possible skill, but also with the greatest possible force. When the sharp and piercing "zourlas" joined in with oriental melodies, I imagined that may be the music from the Old Testament, which had brought the walls of Jericho crumbling down, had sounded like that. The music didn't seem gay, whether the tunes were drawn- out or fast, sad or playful. They were moving, cutting into the soul, and certainly not cheerful. They merged with the surroundings, with the hard, sharp rocks. That alone was astounding.

Seeing me lost in thought, my companion smiled and said, "This year is nothing special. We have only twelve weddings and only four orchestras came. Other years as many as eight or nine may come. This summer only the grooms have bands, while in other summers the brides do too."

Images of the apocalypse shot through my mind. I imagined that the final call for the Day of Judgment would sound like that.

I was also thinking of the newly weds, or as they were called "The young ones". The bridegroom was called "the just wed', and the bride "the just wed" or "the young one". She was called so for a full year after she had been married. But what did their souls feel? (The young men married not later than the age of twenty two and the young girls not later than eighteen). How did these sounds, resembling thunder and blizzards, affect them.

Wasn't the effect actually suitable for the significance of the moment? Was it not an invitation for a funeral bell-ringing for the lost carefree youth. Was it not an introduction into one's own struggle in life? Wasn't it the moment when one struck a balance of the first period of his life, so that he could enter into the next one with a clean sheet, where the laws of nature (therefore, God's laws as well) made their demands with all their severity and inexorability? Wasn't it a call for the Day of Judgment, albeit a temporary one?

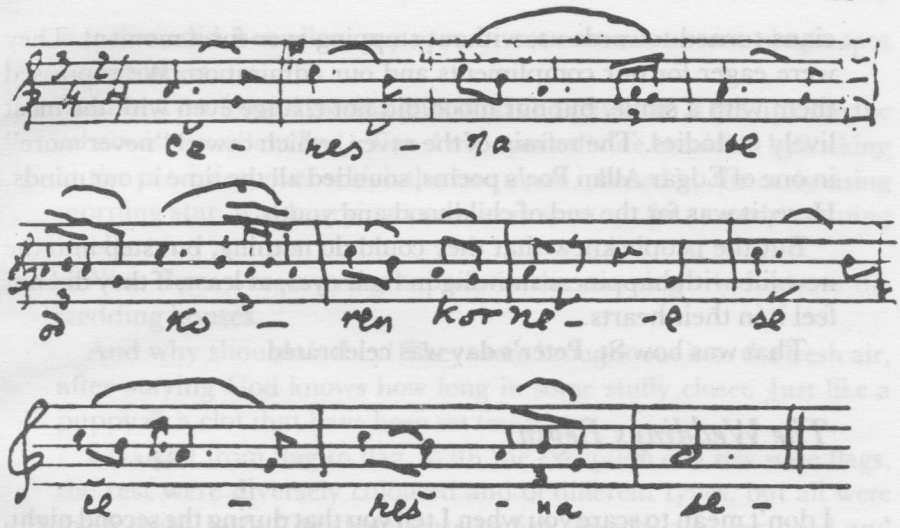

I was reproaching myself for perceiving it all so tragically, but later, when I listened to the women's and girls' chorus, which was accompanying the simple and at the same time grand rituals with archaic singing, like that of a monks' choir, and wrote down the classical tunes, I found out that I had not been mistaken. The creators of the cult, in times long past, had also perceived it as the end of one and the beginning of another period of life, as a fateful turning point, where family branches were broken, as the following song expressed it:

--------

![]()

81

A cherry tree was being uprooted,

A young girl — parting with her home.

The tree was being uprooted,

the girl would not part with her father.

The top of the tree was bending,

the girl would not part with her mother.

The tree's branches were falling,

she would not part with her brother.

Its wide leaves were falling,

she would not part with her sisters.

Yes, that was an ode of grief! It is a song of a parting, but not of a separation. And this is possible in the family tree, in which the whole secret of kinship, as a source of attracting and repelling forces, in their constant, undying struggle, is contained. Such is the content of life, since the eternally repeating themselves attractions and repulsions of separate individuals are nothing but the breathing of mankind as a whole.

We went near the gypsies. The echo was gone and the performance sounded simpler, even though it wasn't quieter. The "zourlas" pierced our ears still more violently. The faces and the necks of the players were about to burst, while the drummers were beating the drums with the most savage movements. We admired their muscles and their chests, but the skins of their drums deserved admiration as well, since both they and the muscles were not yet torn. The musicians

![]()

82

turned towards us, without stopping even for a moment. They were eager for our compliments and our admiration. We expressed them with a smile, but our mood did not change even with the most lively melodies. The refrain of the raven, which cawed "never more" in one of Edgar Allan Poe's poems, sounded all the time in our minds. Here, it was for the end of childhood and youth.

But the people knew that they could do nothing, but step into the new life with happiness showing in their eyes, at least, if they did not feel it in their hearts.

That was how St. Peter's day was celebrated.

I don't mean to scare you when I tell you that during the second night, at four A.M., I was awoken by rapid shots and I remembered at once the stories I had heard from local people, how their region had suffered for a long time after the war from neighbouring Albania, while the Belgrade government flirted with it, for political reasons, the highwayman Kalyosh was able to make frequent raids into Galichnik from the nearby border and to carry away, without being punished (since local residents were not allowed to carry firearms) 15 million in gold. That is why I will quickly add that the shooting was followed not by an Albanian raid, but by a gypsy raid. The drums of the gypsies assisted the guns quite well and together with them prepared the transition to the shrieking "zourlas". So the wedding ceremonies began for us, who were tired and sleepy, not very pleasantly, but quite impressively.

I couldn't sleep much, even though I had tried hard to do so. In order to fall asleep, one has to fix his eyes on a certain spot on the ceiling, but I had found out suddenly that my room had no ceiling. I knew, of course, that as a guest I was under a friendly roof. I must add that my bedroom was not called a room, but a "chardak", which meant an open room or gallery, dug into the house. In this cool climate it was not an open room and (he only thing in common that it had with the "chardak" was that it had no ceiling.

I don't deny that the beams (from the roof structure of the rest of the house) offered enough lulling spots, but the dried mutton which hanged from them, and which was the subject of study of the numerous

![]()

83

flies, did not allow my eyes to concentrate on one single spot undisturbed.

After a prolonged tossing (spiritual and physical), I got up from the otherwise excellent bed, offered my eyes a divine breakfast by looking at the precipice, over which the late moon, chased by the early rising morning star, was hurrying away, and went out for an early morning stroll.

Nine flags were waving happily in the morning wind, above the wedding houses.

And why shouldn't they! They were brought out into the fresh air, after staying God knows how long in some stuffy closet. Just like a puppy or a clot that have been set free!

I walked from flag to flag. With the exception of a few state flags, the rest were diversely coloured and of different types, but all were made with taste. On them were stylish, heraldically arranged and drawn figures: a cross with four crescents in the corners, a circle with four crosses around it, etc.

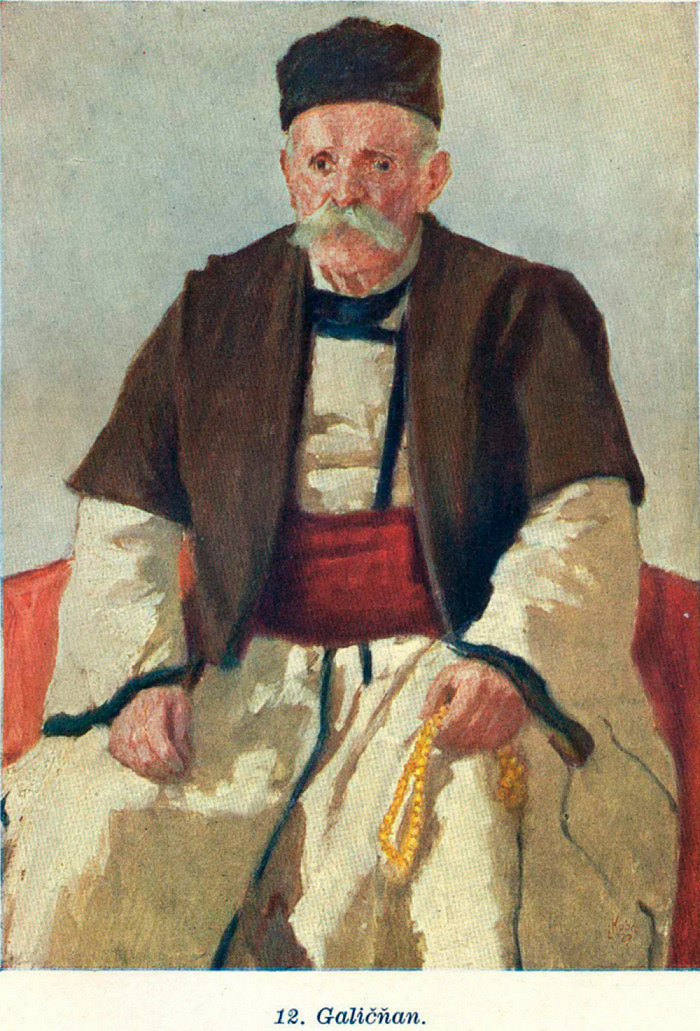

I was pleased that the people stopped to talk to me. I learned that each family had had a family flag once. "We have always been free and independent", they told me proudly. "We are from the Miatsi tribe, neighbours of the Birzatsi" (they pointed to the southwest). "Records of our two tribes date back for more than a thousand years, from the time of the Bulgarian Tsars who had ruled in nearby Ohrid. Tsar Samouil came from our region".

We could speak of the nobleness of the local people, of their way of life and their politeness, if we weren't overwhelmed by their democratic equality, exhibited not only by the Balkan manner of addressing each other with the familiar form "thou", but also with the fact that there were no servants, employed farmhands or beggars. In many respects we were reminded of Montenegro (especially by the bearing and costumes of the Vasoeviches'), but a tendency towards haughty commanding existed there, especially as far as the women were concerned. Their situation there was below human dignity, while here, althouh religious laws subjected them to men, in practice they were their equals.

Our first impression was further strengthened. A ceremony, existing for centuries, was connected with the magnificent women's costume. Only when one knew whom and how to treat, was his conduct free and easy, i.e. rid of any embarassment, just as a train

![]()

84

moved freely only in well embedded and firm rails.

We visited the three married brothers of our host, who lived in the family house. At the entrance we were met by the men, the women, and the children with cordial handshakes and a greeting: "Welcome!", to which we answered: "Well met!". The real welcoming, with the participation of all, took place in the oldest brother's room, and after mutual questions on our health and our families, ratlouk (a pastry) was served first, followed by jam, black coffee and brandy.

We thought that the visit to the house, i.e. to the three families had ended. But we were mistaken! The second brother took us to his room, where the ritual and the feast were repeated, and then we went to the youngest brother's room. The only difference had been in the conversations, which had centered on the large family portraits of heroes, fallen in the pre-war battles with the Turks, or died abroad. The wide and spacious rooms, although partly arranged with Western furniture, were basically old fashioned: divans, covered with rugs and pillows were arranged along the walls.

We left the house as if we were leaving a ritual ceremony, but outside we witnessed, and partly participated, in another, and this time real, ritual.

A phantasm was coming towards us, a woman walking in the scorching, blinding sunlight. The bright stips on her yellowish coat alternated with the red and dark-red surface of her heavy tassles, her rich embroidery and the woven apron. A dazzling, colourful, silk scarf, a wide silver belt, and a gold coin added to the magnificence.

The lovely woman, with pink cheeks and a dignified modesty, stopped beside our first companion and handed him the wooden wine vessel, which was hanging on a leather strap from her finger. The flat sides of the vessel were richly painted and it was decorated with a flower and a small coin. It was called karta. The woman said, "Be blessed!"

My friend explained, "She is a caller". She is inviting us "for water", i.e. to a wedding." She handed me a wine vessel, from which only older and more important people could drink. Only "brides" — young women — were chosen to do the inviting. The big silver clasp on her belt, the nizalki (hanging ducats) and the mahmoudii (Turkish silver coins) were lent to her by the groom, in order to show the gifts he had prepared for his bride.

![]()

85

The men drank from the "karta" one by one, saying, "Be blessed" May you be happy and have many children."

The caller took her karta and replied to the married, "May God give them to your house as well", and to the unmarried, "May the day come when you will also have some".

My turn also came. I repeated what was hinted to me. But that was not enough. I had to bear the consequences of my age and had to drink from the vessel.

After that, the woman entered the house in order to continue performing her task.

"Little by little she will invite the whole Galichnik", I sad.

"Of course", was the reply, "we are all one big family!"

When evening came, I had lost the count of the number of weddings I had been invited to.

Fetching Water for the Parents, for the Last Time

Fetching water in the morning and at dusk has been, since ancient times, the beginning and the end of the working day of the young girls and women. It was not only a physical or material necessity, but an inexorable one as well. Therefore it was a law, something supreme, which was indisputable and which one could only obey humbly. He who is humble, says the Bible, he will prosper. That was what had happened. The sould had risen to a height, from which its act had actually looked like a ritual, and from where it could evaluate it morally and artistically. It had made a subject, or at least a motif, for numerous songs of this act. It had lighted it with its art. The people of Galichnik had achieved even more. They had apotheosized it and placed it among their wedding rituals. And they had created two rituals: one as an overture and the other as an epilogue, of a grand opera, with beautiful sets, called a Galichnik wedding.

It had two acts. In the first one the bride was brought on horseback to the groom's home, where until the morning women guarded her. In the second, one the ceremony was performed. In the overture, the bride fetched water for her family, for the last time. In the epilogue (at four thirty A.M. after the wedding) she went to fetch water for the first time, for her new home.

The structure seemed simple, but it was hidden among a week of celebrations, which from the artistic point of view had only one

![]()

86

flaw — that in terms of beauty, the overture was superior to all that followed.

No one was to blame, of course. At first, the groom had not allowed the woman he had chosen to perform any chores in her parents home, even at the last moment. He had lied in waiting for her, had blocked her way, and the bride had been forced to bring her won suite with her, thus ensuring her personal protection. Sometimes, there had been fistfights, for fun or real ones, and sometimes even shooting. Such were the origins of the magnificent processions with burning torches, with songs and dances, which accompanied the brides to the three water fountains, while at the grooms' houses there was eating, drinking and gaiety.

The Galichnik rocky amphitheater with its nine processions in the moonlit night was unimaginable. (The processions were nine, because there were nine weddings).

Four gypsy bands, which shook Galichnik, were invited.

I could have taken part in any of the weddings, but my friends took me to Yordan's. His house, illuminated by a large bonfire, flared high above us. The fitures of the musicians could be seen in front of the bonfire. They were competing with the flames with brisk movements. Some were beating the drums, while others were jumping up and down and playing the zourlas. It was a satanic idyll, an infernal home, in which comfort was represented by a small arbour, prepared for the musicians, where they could eat and rest. It remained a mystery when they used it, though, since the air shook day and night from their drums.

It was a bit of an effort for me to keep up with the others, while going up towards the house. We moved slowly along "the road", which could hardly be called a road. I used a majestic stick, even though I did not look majestic myself. I had frowned when they had made me take it, but when we arrived, deafened by the gypsies' fanfares, I was grateful to it, because by mustering up my last reserves, I was able to walk with the necessary dignity through the sunlit yard, as a Herzog in an opera, passing through the stage. Everything around was a theater and I was an actor. In front of me stood a house almost as big as a palace, with a balcony full of people and with stone steps on which men in official clothes and women in splendid costumes stood. The blazing fire divided the figures into bright lights and dark shadows.

![]()

87

We kissed the groom and after that we were greeted by his mother and the others. We could hear nothing. Our ears were filled with sound, just as our eyes were filled with light.

The house was full of people everywhere: in the corridors, the staircase and the rooms.

The rooms on the first floor were turned into dining rooms, with long, low boards from which tables and shelves had been made in such a way, along the walls and in the center, that one could easily step over them and over everything that was arranged on them. It seemed to be taken right out of a sixteenth century Breughel painting.

Everyone offered us a hand. Happiness, that we had come to enjoy ourselves with them, gleamed in everyone's eyes.

The host led me to the corner, where the priest and the elders were sitting, but I asked if I could be taken to the verandah first. The view of Galichnik was enchanting: along the slopes, between the houses, snakes, emitting faint lights, were crawling. The moon appeared suddenly and immersed everything in a silver light.

A young man approached me and handed me a pine splinter, to serve me as a torch. It was time for us to prepare, as well. We lined up in the yard, lit our torches, and started moving, accompanied by the song:

A girl was fetching water in two colourful pitchers.

A wild, young man appeared and broke her pitchers.

The girl started crying; Oh, God what has happened

How am I going to tell my other, Oh, aman, aman!

![]()

88

I was walking as if in a dream. Where was I? At a woodnymphs' fair? Or at a gathering of midnight spirits? I felt that I was one myself. Soon I started stumbling and falling down. Spirits don't stumble. It makes no difference to them whether they are walking on a road or not, while I had to be guided by my friends. The rest walked easily. They were used to it. Buy they had another difficulty. Opposite us, another procession was coming, singing another song:

You can wait, father, for cold water,

wait, and fall asleep by the gate.

You'll have neither a girl, nor cold water,

they have taken away your daughter.

They managed to pass each other on the narrow path and to maintain their balance, but their songs were entangled and it took a long time to untangle them.

I confess that, that night I didn't see a single bride, nor the actual filling of the pitchers with water. For more than an hour I was occupied with protecting my limbs, on the one hand, and trying to absorb as many of the constantly changing images, as I could, on the other.

When we returned to Yordan's house, I felt quite exhausted and when we sat down beside the full tables, they all promised that they will not let me leave until the morning. It would be nice — there was singing, dancing ad jokes — but too much for me. I waited only for the ritual with the wedding loaf, which had been baked the same day, and then I quietly moved away to get the rest I so much needed.

The loaves were two, looking the same on the outside. They had drawings, inscriptions and monograms on them. But one of them had some old silver coins inside, while the other had nothing. The empty one was sent on the next day to the bride, while the other one was torn into pieces during the supper and everyone was given a piece. Whoever found a coin in his piece, handed it over to the host, who had to pay ten dinars for it right away.

The ritual was accompanied by a song, which was sung by two old people. They kept the loaf between themselves, rocking it with their knees:

The moon shone on the respectable table,

but it wasn't the moon.

It was the honest round loaf.

I had no luck with my piece. There was no coin in it. When I got up

![]()

89

to go to bed, the people sitting next to me started laughing and said that I was going away because I hadn't found a coin.

"I did", I answered with a joke, "but I preferred to swallow the coin instead of asking for the money and that is why I can't stay any longer . . ."

Everyone roared with laughter. A number of remarks, which I shall not repeat here, were made.

I started towards home under the full moon. It was light as day. Galichnik seemed to be immersed in a silver bath. I repeated to myself the song "The Silver Moon", which seemed quite appropriate for the moment.

On the next day after St. Peter's day, the day before the weddings, the groom must go and ask for the bride, after which the matchmakers will bring her to his house, but will not hand her over. She will be left locked up in a special room, where she must spend the night with a few women. This is called "repenting".

Such is in short the contents of the busy day, which is marked by galloping horses and fluttering flags.

A flag waves on top of each groom's house, although not all the time. It is hauled down and hoisted a few times, according to the needs of the galloping matchmakers. Each wedding has a number of compulsory figures: a messenger, a sworn brother, a standard bearer, and matchmakers. All of them can go home at any moment, can hoist the flag, and can shoot. They gallop around, in order to show their skill and courage, since in some places the roads seem to be built especially for falling.

That day is the most difficult one for the engaged couple, who are in the center of various rituals, since no custom, offering them convenience, has ever been created.

I didn't visit them all, since as the French saying goes, one can't ring the bell and go with the procession at the same time. I don't know what was done with the bride before noon, but I saw what was done with the groom. They were just going to shave him and give him a haircut, but the poor young man had to endure so much, until they

![]()

90

were finished with him!

They had to look for him for a long time, since he had hidden somewhere. He hadn't done it on purpose (although I wouldn't wonder if he had) but because such was the custom, a memory of times past, when the young men had been shaven and had had their hair cuts for the first time for their weddings. When he was finally brought in, the room was full of people. With some difficulty, I managed to edge my way into the middle of the room, where a couple of girls with a white towel and a brand new bar of soap were standing beside the groom.

The "barber" couldn't be just anybody. He had to be a relative of the groom, and if such a relative couldn't be found, special rules pointed out how to find a substitute.

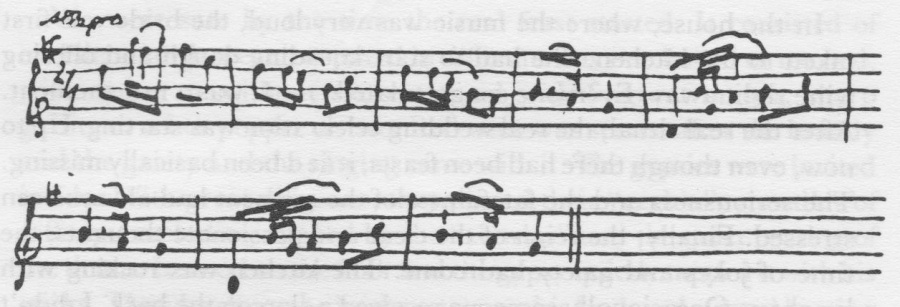

The operation did not begin immediately. The girls' chorus started a song, which explained why the groom had to be absent:

The groom doesn't want to be shaven

until he has parted with his father.

The groom started saying farewell to his family. The drawn out singing was with a small range, but was rich in minor decorations, like the rest of the local ritual melodies, and was moving with its grief. The groom turned pale and we were all stirred.

The confusion which ensued, when the shaving was about to start, took us out of our daydream. The young man bent down his head over the wash basin but the razor went from hand to hand and couldn't find the right one. When it finally did, it turned out it turned out that the barber was not very deft. We were alarmed, since deftness was absolutely necessary. The rules did not allow any foam or hair to fall

![]()

91

on the ground. Everything had to fall on the towel, which was later given to the bride.

There was singing all the time and I wanted to write down the notes of the song. It wasn't easy, not only because writing notes was always difficult, but because the songs, even though they were old, were full of life and their details were gradually changing.

We both heaved a sigh of relief when we were finished: the bridegroom with the shaving and I with the song. He went to change while I went to look elsewhere. In the yard it was very noisy. Two horses were being saddled there. The groom mounted one of them and a young boy the other, with gifts for the bride and her family hanging from it. The gifts were in bags. A sworn brother, carrying bags with bread, wine and meat, was running to and fro with the match makers. He didn't wait for us but hurried with his suite to the bride's house, to announce the arrival of the groom, to hand over the gifts, and to receive gifts in return, as a sign that the groom may enter.

The rest of us, led by the groom, started a little later.

The groom was sitting upright, his right hand, according to tradition, on his belt. His father was walking beside him. We were lucky that some joker hadn't placed and hard or pointed object under the saddle, as it often happened. The horse was calm and the groom could ride with dignity, as the moment dictated.

In the meantime, the sworn brother had galloped wildly around the village with his suite, and we arrived almost immediately after him. On the terrace, a group of young girls was singing like an ancient choir. Their one-part song was for the sworn brother.

The standard bearer was hoisting the flag on the bride's house, while the sworn brother came out of the house and handed a vessel with some of the bride's wine for the groom to drink.

We could all enter now, or at least, as many of us, as the house could accommodate.

The groom kissed the hands of the bride's parents on the doorstep, stepped over it with his father and handed an apple with three old coins (which were later returned to him) and two extra ones to the bride's brother. The bride was nowhere to be seen. According to tradition she was hiding somewhere, still in her everyday clothes, looking at the groom through a ring and saying, "I am looking at you through a ring — you have entered my heart."

A white cloth was placed on the groom's right shoulder and his

![]()

91

friends sang: "Congratulations for the shirt, hero, which the girl has embroidered for you!"

That was all that the groom would receive for the moment. He returned home with his suite, tasted some "sarailia", a ring-shaped cake, with them and repaired to the small room, which would later be occupied by the bride, sitting up all night and "repenting". The matchmakers went to fetch the bride with the groom's horse.

In the meantime, there was a small feast at her house. The brothers brought the bride, who kissed the hands of her future father-in-law and the other guests and they gave her gifts. Over the loafs of bread, which had been brought for the bride, they placed shoes, buckles, veils, etc. Next to them they placed smoked trout, rice, hazelnuts, raisins, sugar, a mirror, a comb, a thimble, brandy, silver threads, a silk scarf. Many stories and jokes were connected with these gifts, since the bride's parents criticized everything. They said of everything that it was not enough or was of poor quality. They picked up the buckles and returned or was of poor quality. They picked up the buckles and returned them disparagingly, saying that they were not golden but just gold-plated. The groom's father swore that he had bought them as pure gold, but that the goldsmith had swindled him.

In the din, a knock on the door leading to the next room, was heard.

There, the bride had changed into formal clothes in the meantime, while the sworn brother was knocking and calling to her to hurry up, so that they could leave.

She appeared on the threshold, dressed in gold, silver, silk, and heavy, woolen clothing. The sworn brother took her by her left hand, her brother by the right one, and accompanied by a sad, girls' chorus, they led her towards the yard, where two horses were neighing. One of them, the groom's, was for her and the other one was for her dowry. The groom's father threw coins and sugar cubes over them.

The mother was afraid to look at her daughter even from the window. Part of the bride's relatives accompanied her for a while. They led her horse and supported her, while she bowed to everyone they met. Her relatives left her when they had passed half the distance to the groom's house.

After that, the groom's relatives guarded her. Some of the women supported her on both sides. Others, carrying water, sprinkled the bride's flowers, so that she could be refreshed in the stuffy heat and the heavy clothing, while some wiped the sweat off her face.

------

![]()

93

It was a magnificent scene, a regal picture. The girl's dignity was increased each time she bowed deeply. Her eyes seemed to be closed all the time and her forehead touched the horse's saddle. The women had to help her raise her head.

The arrival at the new home was also magnificent. Following the enthralling music, the horse stopped in front of the house, walking right up to the carpet, which was laid from the door, since the bride must not step on bare earth. The carpet was immediately rolled up after the bride had passed on it.

With that, her glory came to an end.

Upon entering the house she ceased to be a princess and became a housewife. She was taken to the fireplace, where she touched the cauldron, hanging on a chain over it, with her forehead, in order "never to leave the house". She was handed a bolter, to sift some flour, and some dough to knead it, while the womens' chorus was singing:

The bride knows how to knead dough ....

The bride knows how to twist it . . .

She was handed a glass of wine, in order to treat those present, and the chorus sang:

The bride knows how to obey her mother-in-law ...

The whole family was mentioned in the song.

How it went on I didn't hear. We were shown into a room, where a feast had been prepared. Later, I was told that it had gone on until the morning. I didn't stay that long. I sat exhausted by impressions among the merry wedding guests, where food and drink alternated with music and songs.

When I was leaving, the host came to see me off. I asked where the bride was and could I say good-bye to her.

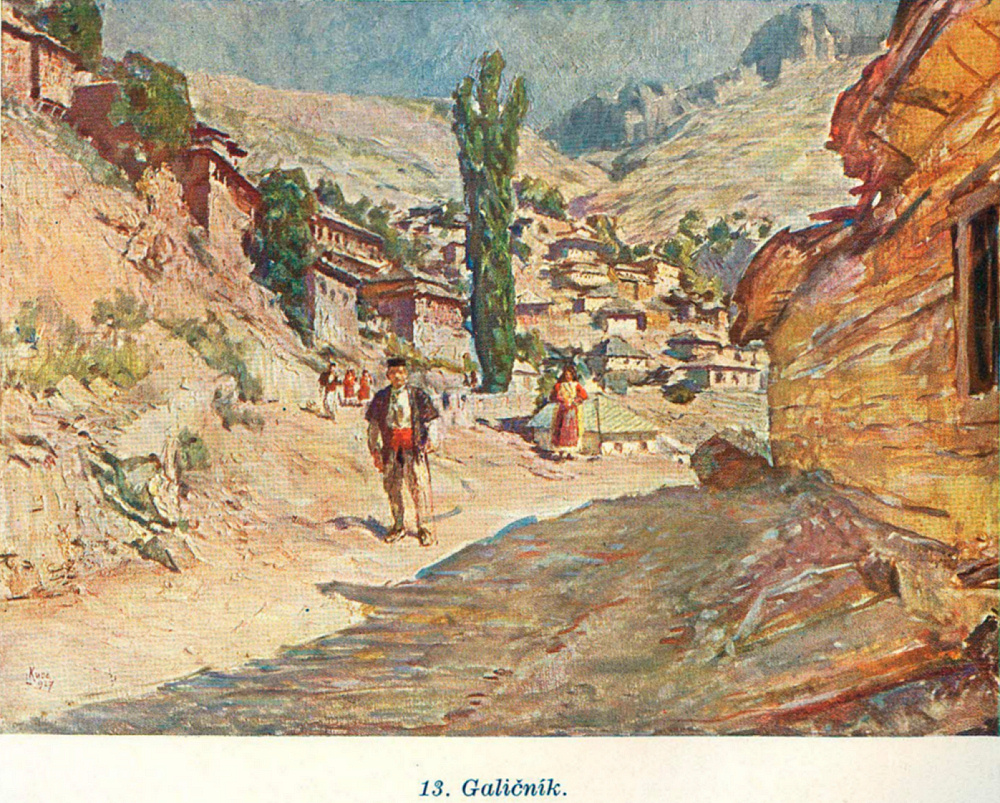

He pointed to the right, to the small room with an open door. To my amazement, I saw an exquisite scene. Among the colourful chaos of the motley rugs, in a fern forest, surrounded by young girls, dressed in her dignified, maybe even too solemn costume, in which the yellow wool contrasted to the brown and bright-red woven apron and the golden sleeveless jacket, the bride stood in the corner, in her dazzling splendour, in a quiet and serious posture, like the Mount Athos' Virgin Mary. Her eyes were still shut, her hands were hidden under the wide, silk, penance belt. "The bride is repenting." She would stay up during the whole her last

![]()

94

girl's night.

It was the end of her girlhood, a night for deep meditation.

Of the Wedding and During the Wedding

The couple started for the wedding ceremony from the groom's house, where the bride had spent the night repenting and fasting. Such a custom was predominant among the Macedonian and Old-Serbian Muslims, with one difference — the Turkish bride was dressed up repulsively, as a loathsome monster.

The couple walked to the church, led by the standard bearer. The man who walked beside him, carried a bag with two loafs of bread, which he divided between himself and the rest of the guests, but not very evenly, since he took one for himself and broke up the other one and handed it around. Along the way they received breakfast: a couple of young men carried around a tray with chick-peas, raisins, and brandy, and a copper wine vessel. Those of the guests that weren't lazy could just stretch their hands and find a glass at the bottom of the vessel, which in that way was always kept clean.

The groom walked in the man's group, after the flag, with a red stripe on his short, round, black hat and a white shirt slung over his shoulder.

The bride walked in the womens' group. She was led, arm in arm, by her brother on her right side and the wife of the sworn brother (who was actually a brother of the groom) on her left side. She could be easily distinguished from the other women by her bowed down head and by her long veil, which hid her face, but was transparent enough to allow her to see everyone whom she had to bow to. Those accompanying her, touched her forehead and helped her straighten up again. The future mother-in-law, carrying a copper vessel full of water, occasionally wet the shirt and sprinkled the bride. The act was supremely ritual, moving, and dignified. In such a way, the train became a real procession, in which the deity was represented by the bride; homage was being paid to future motherhood.

The women's singing also referred to the bride:

![]()

95

The song mentioned everyone in the grooms family.

Only the couple and their closest relatives entered the church. The standard beared and the rest of the guests remained outside. They found some cool shades, spread out their rugs and started eating whatever they had brought or had bought. When a number of weddings gathered, the place looked like; a fair.

The church ritual was not lengthy. With so many weddings, the priest had to obey the laws, valid for any large industry. The best man placed a flower on the while cloth and standing behind the couple, held two crossed, lighted candles over them. After the ritual, the relatives kissed the flower one by one.

The bride came out of the church, standing close to the groom, so that "no one should pass between them".

Again the standard bearer led the procession and the women sang the same song, with a slight but significant amendment:

The procession walked along a different route and at every "corner the bride wanted to run away and return home. The guests had to stop her by force. My friend pointed out that I shouldn't take it seriously. The bride didn't really want to run away, but had to obey the custom. He also said that I shouldn't be misled by her grave expression. It was again according to custom. She was actually very happy to get married.

Her mother-in-law met her in front of the house. She had a bolter and two loaves of bread on her head, and held them steady with her right hand, while in her left hand she held a pitcher of wine. The guests arranged in a circle for a "horo", which was started by the bride's mother-in-law with a few steps. After that she immediately went to congratulate the bride, bowing three times before her in such a way that the bolter touched her forehead. She then took her into the house.

![]()

96

In the house, where the music was very loud, the bride was first taken to the kitchen. She had to start kneading dough and offering wine right away. Everyone congratulated. It was a rare moment. After the real ritual, the real wedding celebration was starting. Up to now, even though there had been feasts, it had been basically missing. The seriousness and the fatefulness of the moment had always been stressed. Finally, the reign of the clear and passionate thoughts, the time of jokes and gaiety had come. The kitchen was rocking with laughter. Occasionally someone received a slap on the back. I didn't know why, but I soon found out, under the accompaniment of a Turkish march, which was playing noisily outside:

My turn came to offer my congratulation; and my friend quickly told me that I must wish the couple a large off pring and immediately point out a specific number.

"You can wish them, for example, five boys and three girls". I was obedient, as in everything else, but a misfortune befell me! My back recoiled from the slaps that it suddenly received.

The first law was in action until all had taken their turn.

A year ago, when they had been engaged, the fiancées had given each other tube of mercury and had always carried it with them, as a sign that they belonged to each other. Now, their contents were poured into one of the tubes and the bride was to take care of it. The best man kissed the flower, which had been consecrated in the church and handed it over to the young couple. With that the official ceremony ended. There was a break, necessary to all (the guests and the cooks), in order to prepare for the evening feast.

The gypsies urged to the feast with all their might. The drums roared and rumbled, while the "zourlas" played a "maane" (a mixture of Turkish songs and marches) ad while we were gathering for the feast, we thought that we were hearing the thunder of guns. But some wonderful things were expecting us. For example, the hors de'ouvres! Table luxuries and delicacies filled the arranged with musical regularity plates and dishes. There was rice pudding, or pilaf, prepared from rice, milk, and sugar, djoufte (a dried meat, smoked on the wind), djigheritsa (roast liver), all types of local sheeps' cheeses, which were all exceptional, wonderful yoghurt, and divine cream. Children were bringing bread and pouring brandy all the time. They took away the half empty glasses and returned them full.

The groom came in. He kissed the hands of the priest and the elders and said good-bye, since he would not feast with us, but with his wife

![]()

97

in a locked room.

We were sate by the time the real feast started. It consisted of excellent lamb meat, prepared in different ways — boiled or roasted, with sauce or without sauce, served with fragrant onions, sharp garlic, or a hot pepper or two. Red wine was served after the brandy and the gaiety and the singing came with it. The gypsies were invited inside. With great diligence, they played their "ezghia", a medley of different melodies, opened by the "zourlas" and the quiet beating of the drum. It stood on the floor and the gypsy quietly tapped it with his sticks. Then he slung the leather strap on his back and started beating the drum, which was on his stomach, with such force that the ceiling trembled and our ears were deafened. The end of the conversations had come — no one could hear a word.

But still, my neighbour was trying to tell me how the feast would end. I could barely hear him. At half past four all would go "for water". At the spring, the bride could wash them. But it wouldn't be so easy, since the girls would be throwing mud on our hands and the fun would be immense.

The important thing was that the bride's work in the new home started with water, just as it had elided with water in the old one. From that moment on, the bride took on the burden of her new duties for her entire life and it was nice that it was done with universal gaiety. The taking on of the burdens, which only death would relieve her of, was made easier so.

The next days also eased the transition from carefree youth to the burdens of life. There were a few more feasts! One was when the groom's parents and the young couple made their first visit to the bride's parents. Another was when the bride for the first time really kneaded dough. The poor girl was the subject of many jokes, at that, "How could you fall so low", they shouted at her teasingly, "Go home! Run away! What are you doing here, anyway?" And when she started kneading dough, she had to hear the mocking song: But there were more or less family holidays. For the community, the wedding had ended on Sunday with a carnival, in which the men had walked from house to house, dressed as women, Turks, Albanians, or otherwise.

On that day, the flags were taken in, the gypsies went away, and silence slowly began to take over Galichnik.

It lasted for a full year, until the next St. Peter's day.