3. Blank 51

6. Full Cry 111

7. A Lone Line 139

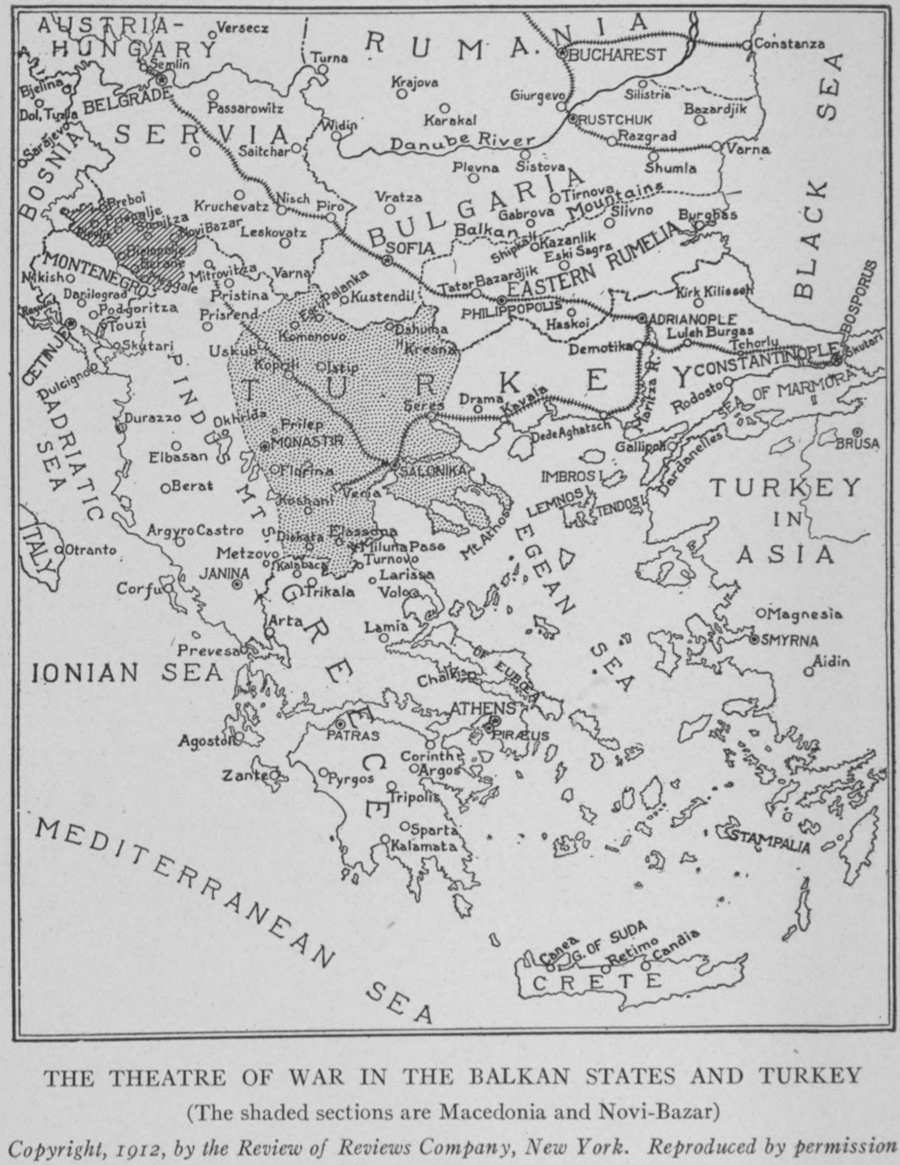

THE THEATRE OF WAR IN THE BALKAN STATES AND TURKEY

(The shaded sections are Macedonia and Novi-Bazar)

Copyright, 1912, by the Review of Reviews Company, New York. Reproduced by permission

THE MEET

THE thirty latter-day adventurers were out for all the journalistic plunder they could lay their hands upon. At the expense of the Ottoman Government they were to be conveyed in a special train to the scene of their depredations. This train was to carry the thirty ruffians who were representing all the great journals of Europe. It was also to carry the thirty odd other ruffians who were their servants, as well as wagon loads of horses and impedimenta. It always takes the station staff in Turkey some time to build up a train. The building up of a train such as this, however, was no ordinary matter, especially as it had to be tacked on to a troop train full of Redifs for the front. It was, therefore, a

![]()

2

great occasion, and the platform of the Stamboul station presented a memorable scene.

The thirty latter-day adventurers themselves were a cohort worth while coming miles to see. The average war correspondent has evolved for himself his own style and fashion in service dress. This is usually a mixture between that of the horse soldier of fiction and the stage villain. In some nationalities, this affectation in dress is more exaggerated than in others. For the most part the British adventurers of experience have toned down the exuberant affectation that marked the dress of the original military journalist. It is now even possible to find some of the more serious adventurers who are content to take the field soberly attired in civilian clothes. The adventurers who were accompanying the Turks, included Englishmen, Russians, Austrians, Frenchmen, Hungarians and one accidental Italian. Each group affected something of a national idiosyncrasy in the general tone of its outfit. That is to say, the Germans only

![]()

3

thinly veiled the fact that they were officers in disguise and strutted the platform with martial step. The Frenchmen, showing sentimental attachment to the cause which they had espoused, had adopted the khaki kalpak of the Turkish Army. The Russians, who are nothing if they are not thorough, had completely equipped themselves for horrid war. The Italian, who had slipped in by mistake, the peace between his country and the Ottoman Empire not yet having been arranged, had essayed the picturesque and was more like a corsair than any of his confreres. The Britishers were ill-sorted. The recruits to the fraternity had evidently seen some one of the old and obsolete type of war correspondent on the lecture platform. They were attired with the straps, watercasks, revolvers, bowie knives, Thermos flasks, Sam Brown belts, and all the other truck which it is the first lesson of active and serious-minded men to learn to discard. The veterans, and there were not many, were less pronounced in their official dress. In

![]()

4

their cases a stout shooting suit usually sufficed. There were, however, exceptions to these, and one gaunt Englishman wore the service uniform of the British army without its distinguishing badges. Another, and it is believed that he was a photographer, had evidently instructed his tailor to dress him on the lines of the boy scouts.

The Turkish General Staff had detailed four officers to have charge of this motley regiment. In reality, five officers were detailed, but the senior, exercising the very subtle wisdom of which he was possessed, selected to remain behind to escort the foreign attaches. The Senior Officer told off to the adventurers was a Bosniak, who had gleaned most of his European ideas in Berlin. When it is understood that this Bosniak shepherd was also an ex-deputy his capabilities can be readily assessed. His subordinates were a bibulous Albanian Bey, whose only noticeable fault was an excess of bonhomie, which on the slightest encouragement became inarticulate affection;

![]()

5

a little Levantine-Moslem lieutenant of the exquisite variety of Young Turk, a type easily confused with a barber's assistant; and a gross brute of a Pera corner-boy disguised for the occasion as a reserve officer of cavalry. If one dispensed with the veneer of politesse Turque, it was easy to see that this little staff of censors resented very much the duties that were thrust upon them. The only compensation really was the probability of being able to add to the daily ration through association with foreigners with means at their command, and likewise to evade the stresses of battle.

But we are getting away from the platform. The adventurers were due to leave Stamboul at five in the afternoon. As the whole world knows Turkish trains never run up to time. There was, therefore, a long wait before the adventurers were fairly under way. It was not an uninteresting period. To begin with, the first portion of the train, as has already been stated, was a troop train. Just at five o'clock, when the adventurers' express should

![]()

6

have steamed out of the station, the Redif battalion which was to accompany them marched on to the platform. It marched on bravely with band and banner. The commanding officer never troubled to dismount from the shaggy pony that served him as a charger, but rode at the head of his regiment right up to the train.

It might have been observed by any of the adventurers or any of their friends who were seeing them off, who, at the moment, had anything but a personal interest in the war, that this Redif battalion marched 600 strong. To control these bearded ruffians, there were only five officers including the commandant. It might also have been observed that the whole of the equipment of the battalion was freshly drawn from store; that the boots were innocent of dubbing or any kind of grease; that at the moment ranks were broken to permit of entraining, the majority of men took off their boots and proceeded to examine their feet. It might also have been observed that while this

---

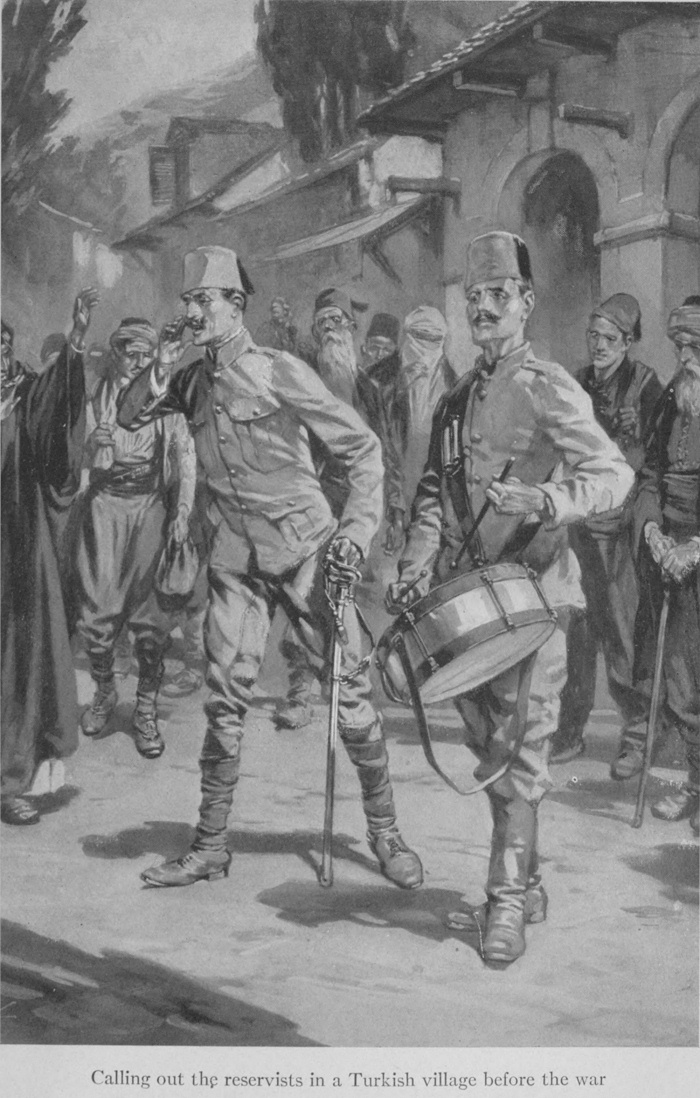

Calling out the reservists in a Turkish village before the war

![]()

7

regiment was being entrained, one of the men in the rear company was taken ill. From the symptoms, it looked as if the man had Asiatic cholera. The medical officer with the battalion, however, did not seem to come to the same diagnosis, and the patient was put into a compartment with his fellows. In parenthesis, it may be said, that he was buried the next morning outside the station, where the train made a long halt.

As soon as the battalion had entrained and the men for the most part had divested themselves of their boots, a little impromptu entertainment was arranged to entice the foreign element present. It was designed to show the enthusiasm and patriotism of the assembled reservists. A company of musicians with knee-fiddles and reed-pipes fell in, and, to the sound of their graceless music, the light-footed of the battalion began a heavy Anatolian dance. In the meantime, the censors moved amongst the adventurers and pointed out the extreme high spirits of those dull danring

![]()

8

soldiers, and invited all and sundry to make mental notes of the spirit stimulating the Turkish army. The adventurers were, however, far too much engaged with their own concerns. It was no mean business to control the amount of baggage that the average inexperienced correspondent considered appropriate to ensure mobility in the field. After some further delay, when the dancing had petered out, the battalion was entrained and the portion of the train reserved for the guests of the Ottoman Government backed into the siding.

It is now time to begin to individualise. To a large extent the story which is about to be told is the adventures which befell one of these latter-day buccaneers. The ordinary subscriber to a newspaper knows little of the difficulties that have to be faced and surmounted to enable him to read, over his breakfast coffee each morning, a true, first-hand, and unvarnished account of the great happenings that grace the pages. It is a little thing to open a

![]()

9

still damp newspaper and to read hurriedly between the mouthfuls of a meal the few descriptive lines that tell of a great battle fought, a victory won, a defeat suffered. It is no concern of the average reader that the appearance in his morning paper of these few descriptive lines is the result, it may be, of infinite resource, of terrible hardship, and perhaps even of desperate danger. He little knows or cares what anxieties have racked the mind of the man who secures the news, or of the expenditure of gold which the paper itself has had to make, to enable its readers to say, as they nod to friends at the railway station, "I see they had another big battle in the Balkans this morning."

The writer, therefore, in following the story of the thirty latter-day adventurers, will confine himself mainly to the adventures of one particular group of British correspondents. He will introduce this group for the first time as they take their places in the compartment allotted to them by the Bosniak Press censor.

![]()

10

It is composed of three adventurers. The first is a robust, hardy looking man who rejoices in the name of the Dumpling, and is renowned amongst London journals as a tempestuous recorder of stirring events. He has not confined his energies to wars alone. If there is a secret to be unravelled, a cause célèbre to be exploited, or a political eruption to be described, he is the man chosen, that the readers of his paper may have moving interest in its strongest lights. He is also experienced in the paths of war. He has followed the drum in South Africa; marched with the Japanese through Manchuria; and mixed with revolutionaries in half a dozen capitals.

Of his two companions in the compartment, one is a man of much the same age, and the other a boy in the first flush of energetic manhood. The former is known to his friends as the Centurion. He has the reputation of having participated in more warfare than any living man of his age. Usually he cloaks the energy and experience thus gained, under a

![]()

11

guise of fatuous levity. On this occasion, however, he is starting his campaign overweighted with a common heritage of a stay in Constantinople. He is suffering from a Levantine form of influenza, that is a type of disease in itself.

The youth is known to the confraternity as Jew's Harp Junior. He is not really a bona fide journalist, but is the brother of the representative of one of the great London dailies, who, owing to a certain nervous affection, and being of a vibratory nature, had earned the sobriquet of the "Jew's Harp."

By the time the adventurers and their baggage had been bundled into the train, and their retainers had been found places, there were many visitors collected to wish them Godspeed. Chief amongst these were some members of the corps of journalists permanently stationed in the Ottoman capital. These gentlemen were generally responsible for the ease and rapidity with which the adventurers had been mobilised at the base.

![]()

12

There were even ladies present to wish the press men adieux, for it would be a poor latter-day adventurer who could not mobilise a heart in the same space of time that it takes to mobilise a caravan. Jew's Harp Junior was a special favourite, and when at last frantic blasts upon the horn suggested that the adventurers were really leaving for the front, fair hands deftly pinned a porte bonheur upon the lapel of his coat.

A moment before the train started there was a rush for the carriage in which our group was installed. "How many are there in here?" said an agitated voice, "three only?" The owner of the agitated voice inserted his head himself, and before the Centurion or the Dumpling realised what was happening, a superfluity of baggage including a loose saddle and bridle were thrown into the compartment. As the train moved off, the owner of this new harness pushed himself in, stumbled over the collective wares, and apologised with true British directness, saying: "I am very

![]()

13

sorry, and I hope that I shall not inconvenience you, but I had to get in somewhere." The Centurion's remarks—his head racked with an influenza headache—will not bear repetition. The Dumpling maintained a diplomatic silence, whilst Jew's Harp Junior was overtly hostile.

The newcomer Was a new recruit, a very new recruit, to the corps of British war correspondents. He was so new that he was unknown to the other occupants of the carriage. He was a fresh, good-looking, soft-spoken youth. From that moment, he was called the "Innocent," and subsequent events were to show how completely the soubriquet described the fresh naivete of the man's delightful character. The Innocent's history requires a little elucidation. Although new to the rougher work of the adventurer's strange lot, the Innocent was no stranger to the paths of journalism. He was the foreign editor of a London daily. The directors of his paper, having determined, late in the day,

![]()

14

to send a representative to the seat of war, had not found a suitable selection ready to hand. They had, therefore, driven forth the Innocent and he had arrived at Constantinople twenty-four hours before the train of adventurers started for the front. He knew nothing of soldiers, less of horses and very little of men. To begin with, he made a bad impression in the coupe that he had selected. He had struck two old soldiers and the brother of a third old soldier. Moreover, the severest of the old soldiers was sick of a distemper.

The train glided slowly out of the station to the clash of the brazen instruments of the Redifs' band, playing discordantly from the depths of an empty luggage van. It was already dark and the lights of Stamboul on either side, were augmented by a firework display from many of the windows neighbouring the line. These displays were ordered to impress the foreign adventurers of the enthusiasm of the people at the state of war. As soon as the sounds of the band subsided and the

---

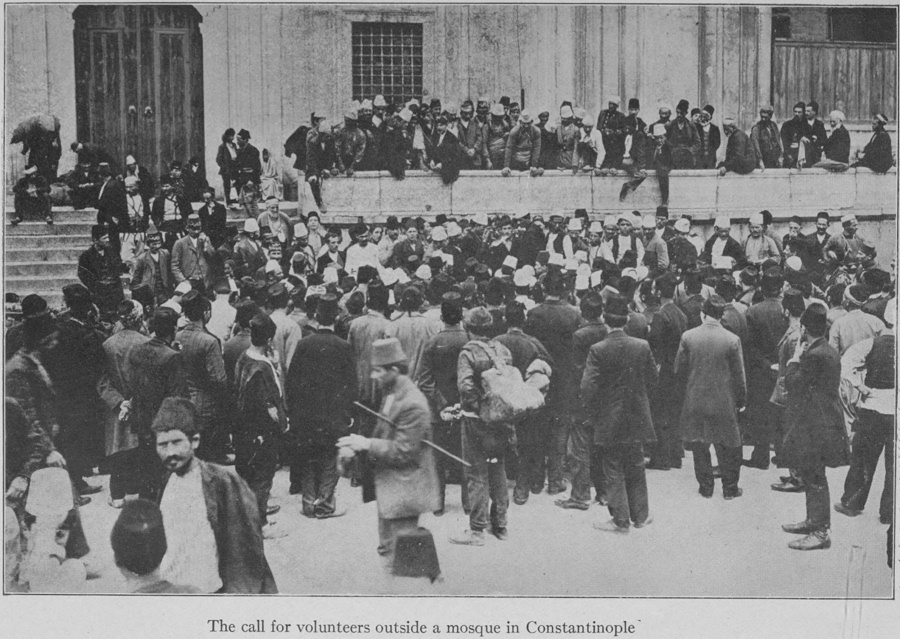

The call for volunteers outside a mosque in Constantinople

![]()

15

occupants of the coupé could make themselves heard, Jew's Harp Junior remarked fatuously: "Well, we are really off."

The Centurion who was trying to disengage himself from the ill-ordered mass of saddlery that had accompanied the Innocent into the carriage, remarked: "We shall be lucky if we get out of this train within three days."

"Three days?" Innocent said, in the midst of an apology he was making to the Dumpling on account of a trunk he was trying to put upon the rack, "Why, I have brought no food with me."

This was too much for an old soldier like the Centurion who was sick in body and ill at ease:

"You don't mean to say that you have come into this carriage without food. Don't you realise what that means? You will have to live on three men who know their business and have brought just sufficient food for themselves. You have no right to come on this kind of business unless you are prepared to

![]()

16

look after yourself. Not only do you come and make yourself a nuisance to other people by forcing yourself into their carriage, but you make it imperative that they keep you as well." Innocent was absolutely knocked out by the sudden and savage attack. He apologised again and offered to leave the compartment at the first stop. The Centurion was somewhat appeased and he sank back upon his own heap of baggage to nurse his headache. Thus the adventurers started for the front.

In order that the reader may appreciate the condition of affairs at which this trainload of correspondents were hoping to assist, it is necessary to give some superficial detail of the Turkish operations as they had so far developed. It must be remembered that this is mainly the story of the Centurion. It does not, therefore, profess to be a history of the Balkan War, or even a comprehensive account of the Turkish operations throughout Macedonia. It is really only a narrative of the Turkish campaign in Thrace, as far as it was

![]()

17

possible for one single correspondent to follow it, and to furnish his newspaper with a consecutive narrative. All the side issues of the campaign and the mire of diplomacy which led up to the outbreak of hostilities against the Montenegrins, Servians, Greeks and whatnots, are affairs apart from this story.

The Turkish General Staff believed that by the date of the outbreak of war they had distributed their armies in sufficient strength in Macedonia to enable them to hold the minor invasions in check until such time as their main army in Thrace was able to defeat the chief Bulgarian force. By this success, which they knew must be gained in Thrace, they trusted to turn the whole scale of battle. It was their intention to march up the valley of the Maritza and by sheer weight of numbers to force the Allies to conform to their advance and thus render any side-advantages that might have been obtained in Macedonia or elsewhere, to be but temporary. The Turks argued that the dislocated invaders would be

![]()

18

forced to come tumbling back to their own countries to defend them from their all-conquering progress. Such was the scheme of the Ottoman General Staff working night and day in the Shereskiet buildings in Stamboul. It was an ambitious plan of campaign, and on paper it read so true that the officers of the General Staff themselves not only believed that it was practicable, but also that it was certain of success. They worried little about those affairs of administration and supply which in all campaigns are the chief essential. In order to carry out this proposed role of the offensive, the Ottoman General Staff intended to have concentrated four army corps on the line Adrianople—Kirk Kilisse. They also intended to prepare an expeditionary force at the port of Media, which, when the main army began its irresistible forward movement, was to have been rapidly transported by way of the Black Sea to some convenient point on the Bulgarian coast line in the vicinity of Varna. The Turks counted on their numbers.

![]()

19

In this they made a similar error to that which we ourselves made in South Africa, when we foolishly counted a man, a rifle and horse, no matter the experience of the man, as a military asset. The Turks relied upon their very excellent method of mobilisation, which they pushed with extreme vigour. The Redifs arrived up in their thousands and were equipped and armed at the arsenals, to be spirited away into Thrace by the trainload.

Competent British observers who saw these happenings at the base, however, shook their heads and said little. They saw units prepared to take the field that were so short of officers, that the majority of the sections were commanded by sergeants. They saw men who had never used anything but sandals in their lives, trying to march in cheap contract boots that hurt the feet; they saw men who were due within thirty-six hours to take their places in the troop train, learning, not only the goose step, but also the mechanism of the rifle

![]()

20

for the first time; they saw horses that had been taken that very morning out of the hackney carriages in the Grande Rue de Pera, turned into gun-teams and driven by drivers who knew nothing of the art. The competent observers saw all these things and shook their heads. Unless there was something that was much better in front of this rabble, the chances of their marching up the valley of the Maritza were very small indeed.

The General Staff, however, were satisfied that all was well. In Kirk Kilisse they had an adequate force sent forward as an advance guard to cover the concentration that was taking place behind. It is true that they had been forced to leave the first initiative to the Bulgarians, but they had good information as to their movements; they knew practically the exact strength of the invasion that was already pouring over the frontier. They were perfectly confident that they would be able to deal with this invasion in due course, when the columns of Bulgarians were entangled in the

![]()

21

mountains north of Kirk Kilisse. For this reason they had only held Mustapha Pasha and the Tundza Passes lightly. They were so confident as to the results of the fighting between the Bulgarian and their own advance guards from October 18th to the 22nd, that they agreed that the moment was ripe to allow their foreign guests to join the army at the front. Kirk Kilisse, therefore, was the destination of this trainload of adventurers with whose fortunes the reader is now identified. As a matter of history, at the very moment that the train was moving out of the station, the Turkish arms were suffering the first of those paralysing disasters which during the earlier weeks of the war, lost to them forever their European provinces.

![]()

22

TO THE FIRST COVERT

TO understand the situation in the middle of which the trainload of latter-day adventurers found themselves at daybreak on the following morning, it is necessary to continue the brief sketch of the early history of the campaign in Thrace. The Turkish armies had been divided into two wings. Of these the right wing was commanded by Mahmud Muktear Pasha, the left was commanded by Abdullah Pasha, the latter reserving to himself the right of Generalissimo provided he ever had 'the opportunity of exercising control, or of communicating with his subordinates. The selection of these two officers was the outcome of a desire to humour German military feeling and the leading sentiment of the Committee of Union and Progress. Abdullah was one of Von der Goltz's swans,

![]()

23

while Mahmud Muktear was a Committee bully. Goodness only knows from where they raked up Abdullah, but Mahmud Muktear was minister of marine when the war broke out, and was transferred hurriedly from the admiralty to a command in the field. Altogether there were supposed to be five corps d'armée composing the army of the offensive in Thrace. These were the First Army commanded by Omar Taver; the Second commanded by Torgad Shevket; the Third commanded by Mahmud Muktear; the Fourth commanded by Ahmed Abouk and the Seventeenth (commander unknown). The Seventeenth Corps was a kind of Colonel Bogie of the Thracian links. Every corps commander in turn was waiting upon it during the most critical moments of battle. No one ever seemed to have seen it, and every defeated general, sooner or later, traced his failure to its non-arrival. If the truth be known the Seventeenth Corps was never really put together. It was to have been composed entirely

![]()

24

from Redif divisions. Such units as should have gone to its credit, even if they were mobilised—which is doubtful—were probably stolen on the railway by the first divisional general who opined that he was short of men and then ran away when battle was joined. Anyway the Seventeeth were the phantom cohorts of Lule Burgas.

The first four corps named above were to have concentrated on the line Adrianople— Kirk Kilisse in the following order from right to left:—Mahmud Muktear, Omar Taver, Torgad Shevket, Ahmed Abouk with the phantom Seventeenth somewhere in the rear on communications. It must not be thought that either of these corps d'armée were up to strength. Most of the Nizam Corps had contributed their quota to the Adrianople Garrison. Some of Torgad Shevket's Second Corps had been left at the Dardanelles while no unit in the whole army was up to the intended war strength. Many in fact were skeleton units padded out with any

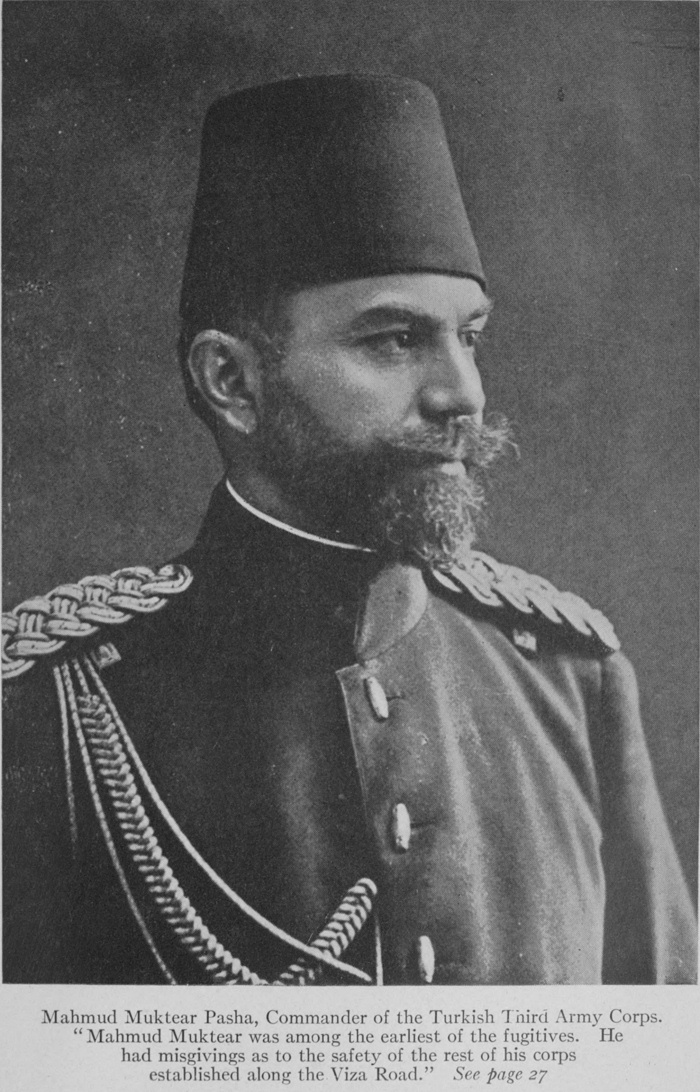

---

Mahmud Muktear Pasha, commander of the Turkish Third Army Corps. "Mahmud Muktear was among the earliest of the fugitives. He had misgivings as to the safety of the rest of his corps established along the Viza Road." See page 27

![]()

25

class of Redif that the mobilisation agents could lay hands upon and hereby hangs the moral of the whole debacle.

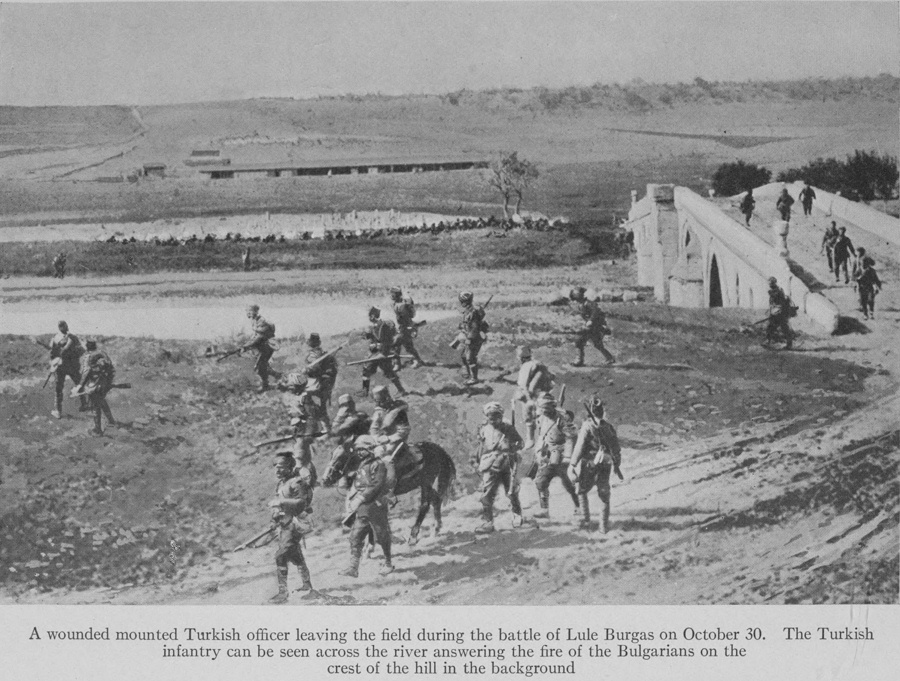

When on October 19, 1912, the Bulgarian invasion had become a very serious affair the Ottoman armies that should have been upon the alignment already indicated were really very much in the following order of chaotic concentration. An advance guard from the Third Corps which was straggling up the Sarai-Viza Road was at Kirk Kilisse. The First Corps was concentrating at Baba Eski preparatory to moving up into the line from which the offensive was to start. The Fourth Corps was collecting at Lule Burgas, while the Second Corps, such as there were of it, had left the railway at Tchorlu or the boat at Rodosto to reach the line of concentration by march route. On October 20th and 21st the Turkish force in Kirk Kilisse seemed to have held up the Bulgarian advance. Mahmud Pasha was here in person. The war ministers' staff at the Shereskiet was fearfully

![]()

26

"bucked." They issued orders for the foreign press correspondents to proceed on the 23rd direct to Kirk Kilisse. The foreign attaches were warned to follow the next day.

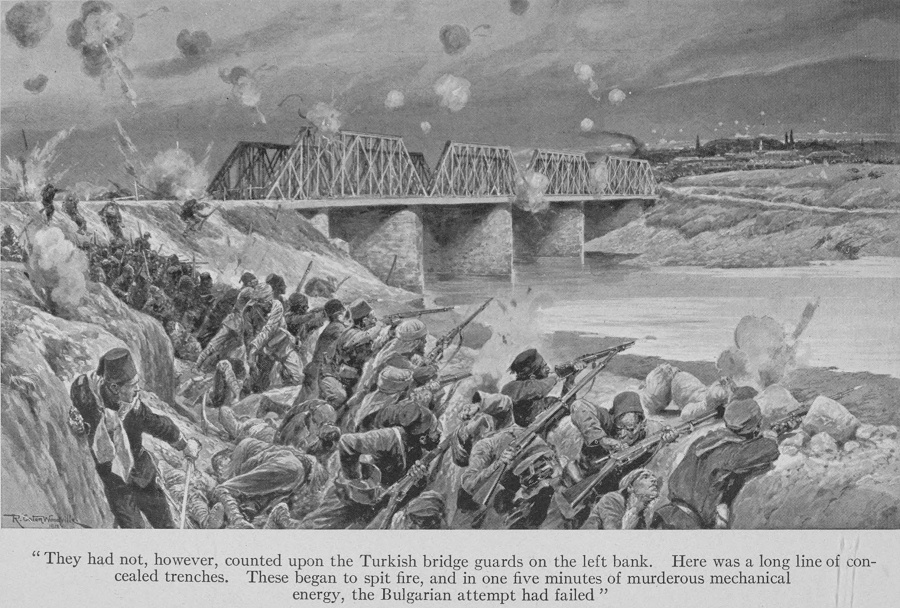

This optimism, however, was doomed to be short-lived, because, before even the order directing the correspondents to proceed to the front could be countermanded, the disaster which was the forerunner of the debacle that befell the Ottoman arms in Thrace, had taken place at Kirk Kilisse. On the night of October 22nd-23rd the Bulgarians rushed the Kirk Kilisse outpost line. The Turkish estimate of night outposts is conceived very much in the same light-hearted spirit as that in which the night watchman in India approaches his duties. That they were rushed in the damp, wet weather that initiated the campaign is not a matter of surprise. It is only astonishing that they have not been more often similarly overthrown. The advance guards billeted in and about the Forty Churches just broke and fled down the Viza Road before the Slav

![]()

27

bayonets. Mahmud Muktear was among the earliest of the fugitives. He had misgivings as to the safety of the rest of his corps established along the Viza Road. The three divisions of the First Corps were the nearest Turkish gros to the scene of the disaster. They were ordered up hot foot to repair the desperate set-back. The three divisions of the First Corps, like the units of the Third Corps, on the Viza Road, were echeloned between the line of concentration and Baba Eski. The Bulgarians, profiting by their initial success, caught the three divisions of the First Corps in detail and severally defeated them at Kavakli, Yenije and Islamkuey. This, however, is another story. The situation, as it concerned the trainload of adventurers on the morning of October 24th was that it was not expedient for the train to proceed to Kirk Kilisse as originally intended.

"Where the blazes are we?" It was broad daylight and the Dumpling had his fat person half out of the window. This remark

![]()

28

was addressed to his companions at large, who, tied up in knots with their baggage and the Innocent's saddlery, were pretending sleep. The Centurion looked a perfect worm and his cough suggested to all within earshot that he had at least one foot in the grave. Dumpling's dragoman now appeared with a tray. He had conjured two cups of Turkish coffee from somewhere. He also had information. The Bosniak Shepherd had been talking over the telephone with someone. That someone had given orders that the train was not to proceed, but was to be side-tracked at Seidler, and there await orders.

This information interested the Centurion. In spite of his influenza he pulled on his leather jerkin and sauntered out. He walked out past the station buildings behind which the Redifs were burying the comrade who had died of cholera during the night. As he cleared the compound the Centurion thrust his hands into his leather pockets and whistled. "What a country for cavalry!" was the

![]()

29

thought uppermost in his mind. As far as eye could reach he was surrounded by an expanse of rolling down-land.

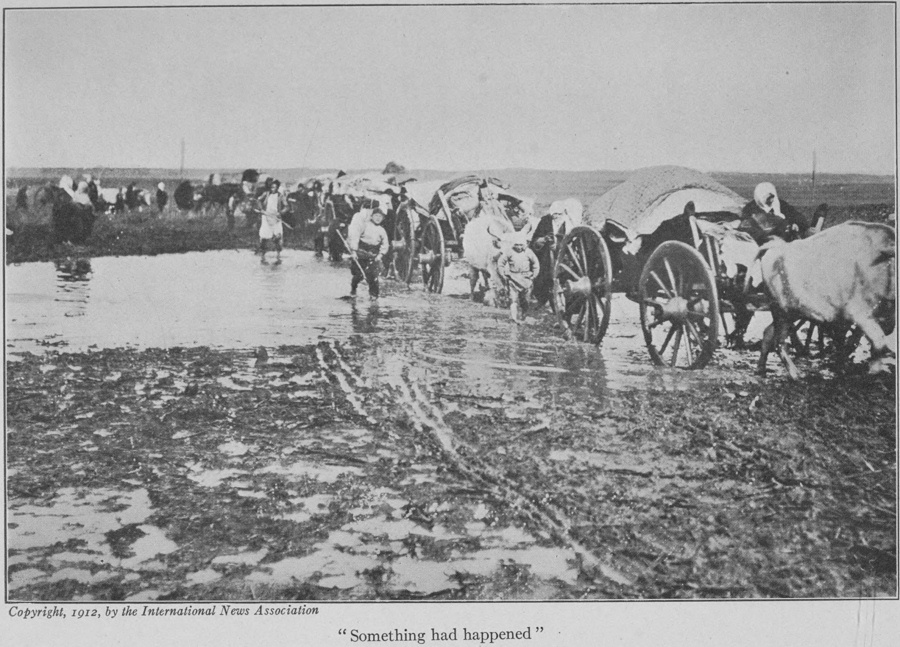

It was a compromise between the high veldt of South Africa and the grassy uplands of Sussex and Hampshire. Then something moving caught the Centurion's trained eye. It looked like transport. A long line of men and animals was coming out of one of those depressions which are peculiar to this kind of country. The Centurion was without his glasses so he sauntered back to the train. By the time he had returned with the glasses the movement from the north had definitely materialised. The whole countryside was full of country wagons. At first the Centurion thought they must be empty transports coming back from the army. The glasses, however, suggested another story. This was no army transport; everything about the movement was civilian. The columns consisted of buffalo wagons, bullock carts and donkey shays. Each conveyance was packed tight

![]()

30

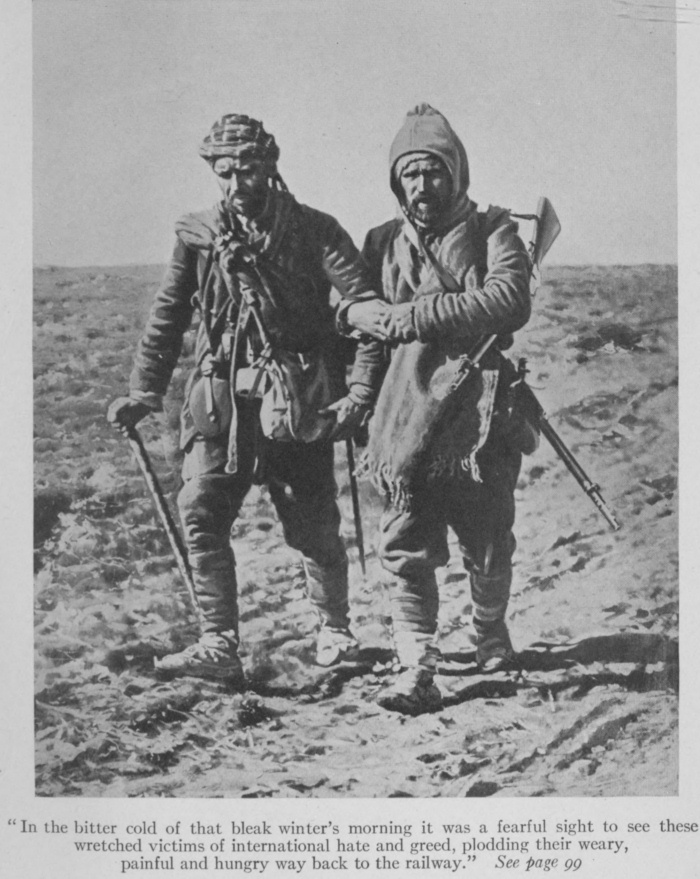

with household goods, women, and children. A crowd of peasants in frenzied haste were urging the animals through the mire. The Centurion put away his glasses and wandered back to the train. Something had happened. Either the Turks had found it necessary to clear the country of the entire civilian populace, or there had been something of the nature of a Turkish disaster up in the north. It was not long before the head of this transport column reached the confines of the station. Then it was possible to see that this was no ordinary clearance of the country. Wild-eyed women with their legs and skirts mired to the knees, were struggling through the morasses that in Turkey pass for roads. Numbers were dragging their children beside them; many were weighted down with crying infants. Old men who had almost reached the perpetual fireside age, already foundered, were clinging to the carts in which tired and distressed animals were toiling under the blows of younger peasants. It was a flight, a

---

"Something had happened"

![]()

31

dishevelled flight of the populace; an exodus brought on by actual terror. It was evident that these wretched peasants had just seized whatever Lares et Penates that came to hand, and had cast them with their infants upon the wagons without waiting to sort out the wheat from the tares. Descendants of a Nomad race they had instinctively taken the road to save themselves from some terror that was behind them. Judging from the state of the animals and the wretched women and children, these fugitives must have been toiling down the mud tracks all through the livelong night. Without doubt such a panic had been caused by events of a serious nature. Of itself the state of these fugitives was a sufficient military reason for the halt that the adventurers' train had made since daybreak.

But what an occasion for the adventurers themselves? As soon as the story went along the train that refugees were arriving, there was a kind of galvanic stampede among the newspaper men in the train. The journalists

![]()

32

were anxiously calling for their dragomen. These later were, with difficulty, unearthed from beneath the horse rugs in the cattle trucks. The photographers and cinematograph artists brought out their cameras and film-engines with such rapidity that the Bosniak Shepherd felt it his patriotic duty to forbid anyone from taking photographs.

Misguided worthy! If a squad of metropolitan policemen have often found it impossible to prevent the Cockney photographic artist from taking pictures in London's Holy of Holies, how much more impossible would it be for the slow-thinking Turk to prevent the same experts from carrying out their instinctive functions when the magic word "refugee" was in the air. This was the first lance that the Bosniak Shepherd splintered with the adventurers. It was not a heavy one, but there was no question as to whom the heralds would have adjudged the success.

The Centurion who was still feeling as if he had been beaten with sticks, retired to his

![]()

33

compartment to study the map. The train was at Seidler Station; that is, it would be about twelve miles from Lule Burgas, the nearest big village, and at least thirty miles from Kirk Kilisse, where on the preceding day the Turkish troops had been said to be holding their own against the Bulgarians. It was perfectly evident, therefore, that something untoward had happened at Kirk Kilisse. As the Centurion argued: If these refugees had travelled at the rate of two miles an hour all night, they would just have made the distance from the environment of Kirk Kilisse to Seidler. Whatever had happened, therefore, must have happened at Kirk Kilisse just 24 hours previous to the arrival of the adventurers at Seidler. The Centurion sent for his dragoman.

This is to introduce John. John was a great man and, as he will appear on several occasions throughout this narrative, it may be just as well formally to introduce him here. John is an Armenian from Broussa. That

![]()

34

will be sufficient for anyone who knows the Levant. To those who are fortunate enough to be ignorant of the Levant, it is necessary to say that John has the flashing eye and the truculent moustache of a desperado and gay Lothario and the heart of a whelk. Nevertheless John has his points; one of which is a great desire to be a British subject. He has tried a good many things. He has done five years in the French Foreign Legion, five years in South Africa and Rhodesia. He has also induced an English school teacher to share his fortunes for better or worse. He had, too, before he took service with the Centurion, an inordinate estimate of his own qualities. Withal the Centurion liked John although it would have been very difficult for anyone who might have seen the two together really to believe this statement.

John of the flashing eye was instructed by the Centurion to interview some of the refugees. Whereupon John, quite understanding what was required of him, strode out into the

![]()

35

most prominent place in the station, summoned four or five of the wretched peasants to his presence and in strident tones proceeded to harangue them. At this moment the Bosniak Shepherd was returning from a futile attempt to coerce the cinematograph mongers. His eye fell upon John. Here at least was a responsive target. The Centurion was watching this from the carriage. He didn't even hear what the Bosniak Shepherd said to John, but in one second the flash went out of the latter's flaming eyes and the heart of a whelk asserted itself. John slunk into obscurity on the far side of the train.

To all intents and purposes, however, the Centurion knew what had happened. A long experience had sharpened his deductive faculties. His colleagues in the compartment, however, were boiling over with excitement. The Innocent, his eyes flaming, came back, and settling a luncheon basket, began to write a despatch. The Dumpling, who was possessed of one of those natures who can never

![]()

36

see another man doing unnecessary and useless work without feeling that he too should be working, began to buzz about the train to find out if there were any means of despatching a telegram.

It is about time to introduce intimately another of the chief actors on this stage. This is the Diplomat. The Diplomat came to take counsel of the Centurion. The Diplomat is one of those charming young men that the Universities from time to time push into journalism. They are a sort of Heaven-sent leaven designed by Providence to save Fleet Street from the level of the Press Club. Hypnotised by the great influence of the journal that employed him, the Diplomat lived only to stoke its foreign department with telegraphic fuel. It mattered little to him whether the fuel he supplied was superior silkstone or disreputable coke; the furnace in London was a gaping maw; the heat there was sufficient to devour coals of all qualities. The Diplomat, moreover, was possessed of that

![]()

37

particular genius of divination, which can always find value in news that the majority of his colleagues, less gifted than he, would reject as worthless. The Diplomat was bound to the Centurion not only in the matter of common sympathies and affection, but in a business relationship in that they were equal partners in a motor car. The Diplomat also was new to the tented field, and he came to the grey head of the Centurion, from time to time, for advice. At this particular moment he was red hot. He began with the magic poison of the word "refugee," which had already permeated his brain. This indeed was fuel of the silkstone brand. He also was possessed of a grievance.

"Look here," he said, addressing the Centurion vehemently. "Do you know what I have just heard? These refugees say that they have come all the way from Kirk Kilisse, and that the Bulgarians took the place yesterday morning. They also say that the Bulgarian cavalry is pursuing them. They say that we

![]()

38

may expect the troopers over those hills at any moment. Also these brutes of Bulgarian cavalry have been committing the most outrageous atrocities on the Mohammedan women and children. That is why these poor people are so terror-struck. Don't you think we ought to get our horses out of the trucks?"

The Centurion slowly took up a bottle of Aspirin, which he had called in to his personal aid and remarked: "There are two things, Diplomat, which contradict each other in your story. Either the Bulgarian cavalry has not been committing any atrocities on the women and children—which from your standpoint would be a pity—and is pursuing, or it has been committing atrocities and is not pursuing. You see the two pastimes do not synchronise. I am speaking now as a cavalryman. It is not, therefore, necessary to unbox the nags. How are you going to get your horses out of these trucks? It requires a platform or a ramp. The equipment of Seidler furnishes neither of these commodities. It is

![]()

39

perfectly certain that something desperate has been happening up Kirk Kilisse way. These people are seeing red and have the fear of God or rather the Bulgarians in their hearts, but I don't think the trouble they fear is quite so close as you imagine it to be. Anyway, we have not heard the sound of a gun yet. It will be time to become anxious when you can hear the guns."

"But there has been desperate fighting up there and we have not seen it," urged the Diplomat.

The Centurion shrugged his shoulders. "One cannot expect to see everything; one must miss something."

"If I only felt sure," said the Diplomat, and here it was that he came down to the real trouble that was agitating his mind, "that Jew's Harp Senior was not getting some special facilities out of this, I would be more than happy. I don't believe a word of this story of his being left behind in Constantinople sick. It is just a plant by which he is going to get

![]()

40

some special facilities. He has got a car and I believe he is going to get up to the front by himself."

"That he was sick when we left yesterday, I know," said the Centurion. "I went to the trouble of ascertaining myself whether he had a temperature or not, so you may dismiss your theory in part. That he will get special facilities is quite possible. Everything is possible in this country if you can make it worth anybody's while to do you a special service. Anyway you are looking for trouble in advance. With the best motor car in the world, and the best will of the Turkish General Staff, Jew's Harp could not be in front of us at this moment. You, Diplomat, are, therefore, much nearer the guns than he is. You, like the natural-born soldier you are, desire to march for the guns. You are quite right, and as soon as you hear the guns, it will be time enough to march to them."

While the adventurers were agitating themselves over the refugees the Bosniak Shepherd

![]()

41

was busily engaged at the station telegraph trying to get orders. As was to be expected it was totally impossible for him to find Head Quarters Staff or anybody in authority who could give him instructions. As a Turk without instructions is always immobile the train also remained immobile. The Bosniak Shepherd would not instruct the station-master to let it go either backwards or forward.

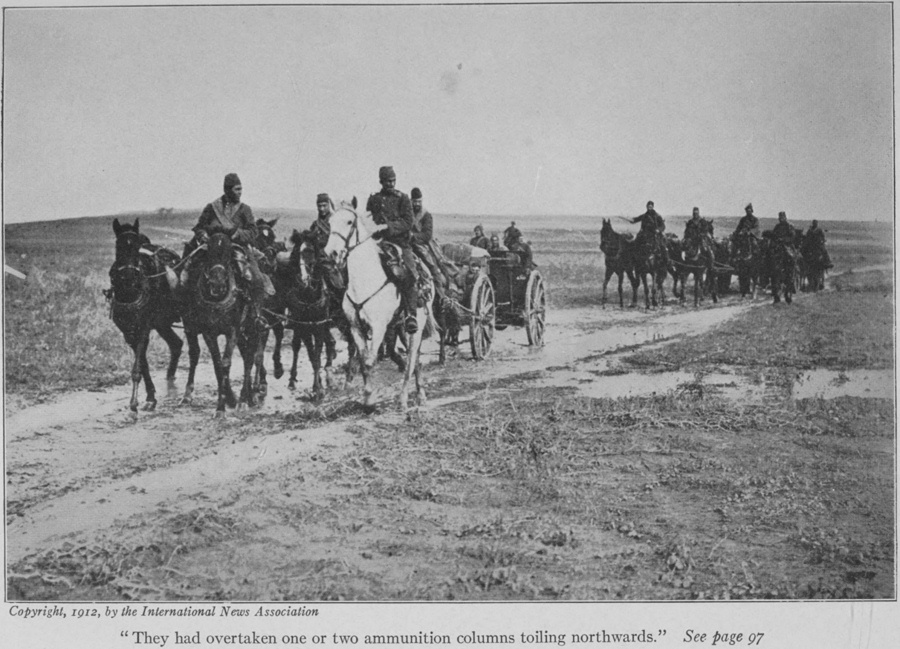

About eight in the morning it was seen that a down train was arriving from Lule Burgas. As it was possible to see this train for at least five miles before it arrived the Centurion wandered up the line as far as the distant signal. There was a water tank here and it seemed probable that the engine would be stopped to take water. As the train arrived it presented the most remarkable sight that the Centurion ever remembered having seen upon a railway line. Not only was the top of every wagon and car crowded with every class of Turkish humanity, but the cow-catcher and plates of the engine were covered with khaki-clad figures

![]()

42

clinging on to the locomotive in the most cramped and dangerous attitudes. At first sight the Centurion thought that there must be some truth in the story of the Bulgarian cavalry being in pursuit and that this train had been furnished with a special guard for purposes of protection; but as the great engine snorted up to the water tank he saw to his amazement that these men clinging to the plates were unarmed.

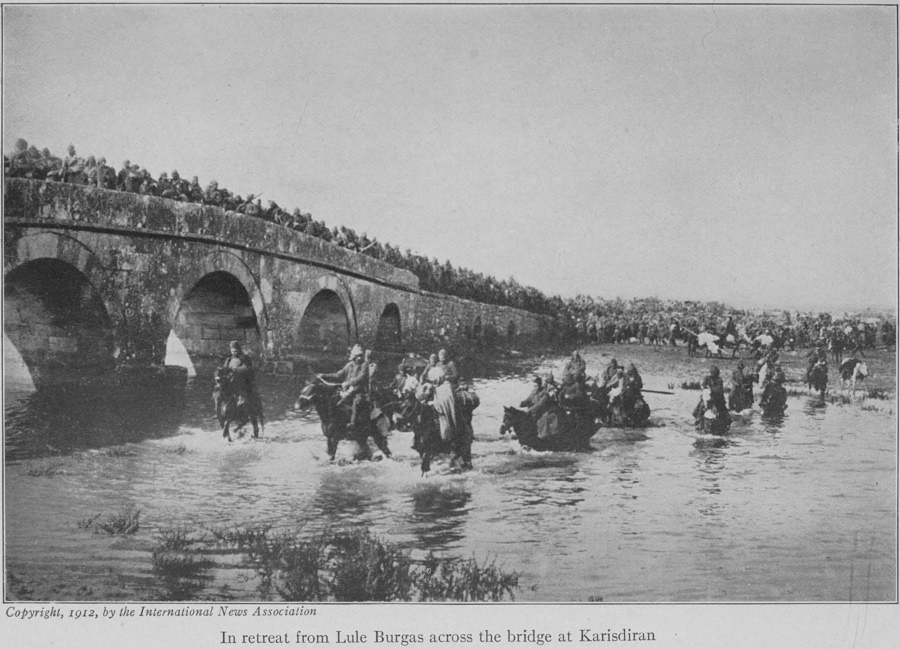

The engine driver was a Greek who spoke French and the Centurion climbed up and joined him on the foot-plate. This train had only come from Lule Burgas, a matter of twelve miles away, yet the engine driver had a most astounding story to tell. He said that the Bulgarians had taken Kirk Kilisse by assault on the previous night: that their success had been made in collusion with a certain section of Turkish Bulgars in the Ottoman Army: that the entire Turkish force at Kirk Kilisse had fled in disorder: and that the fugitives, having thrown away their arms, began to

![]()

43

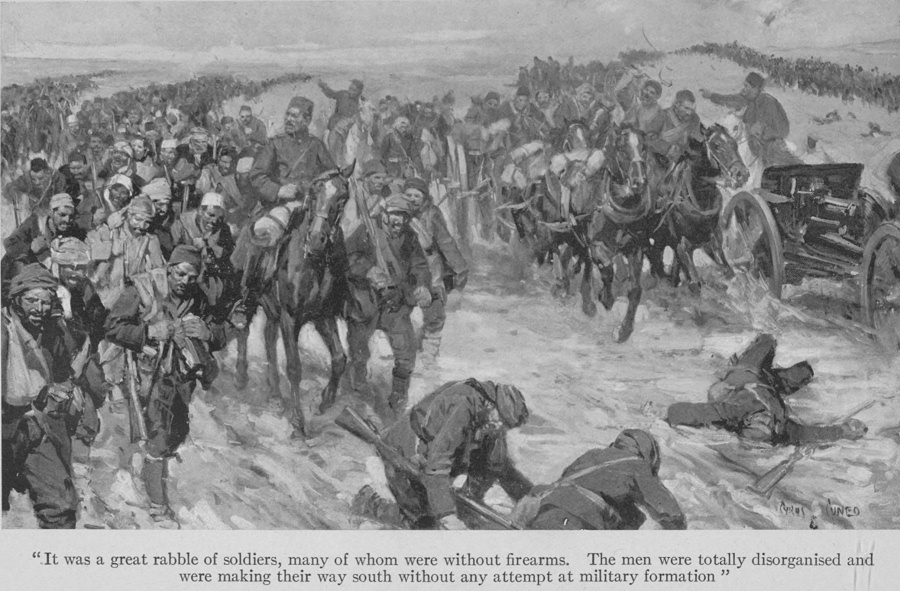

stream into Lule Burgas on the preceding evening. By early morning all the roads leading into Lule Burgas were a seething mass of panic-stricken soldiers, terrified peasants and fleeing ammunition carts. Then, somewhere in the vicinity of the town, people had begun to fire rifles. The cry immediately went up that the Bulgarians were descending on the town. The panic communicated itself to certain Redif troops belonging to the Fourth Army Corps that were camped behind the village. Just as the engine driver had received his line clear the crowd of refugees and fugitive soldiers burst into the station and boarded his train in the manner in which they could now be seen.

A more astounding sight the Centurion had certainly never seen in his whole experience of war. Not only was the train packed with fugitive soldiers, but there were fugitive officers as well. The Centurion tried to get into conversation with one of them. He was of the same type as the majority of the Young Turk

![]()

44

officers,—a young man well under thirty. His eyes were starting out of his head and he babbled confusedly. He was in such a state of mental terror that it was impossible for him to collect his ideas or to speak coherently. Of such a quality is the half-baked soldier in which England pretends to believe.

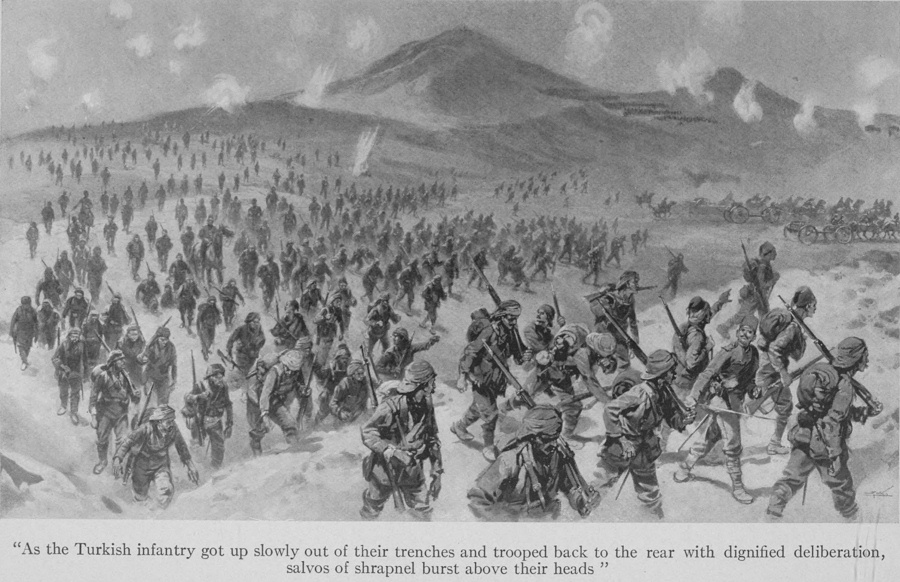

It was evident that a disaster of a very grave nature had overtaken the Turkish arms, but there was one saving clause. The Greek engine driver, who was a man with perfectly clear ideas, said that the panic had only been partial, that the Nizam troops of the Second and Fourth Army Corps in the vicinity of Lule Burgas were unaffected by the stampede and were being moved forward at once to re-establish the Turkish positions.

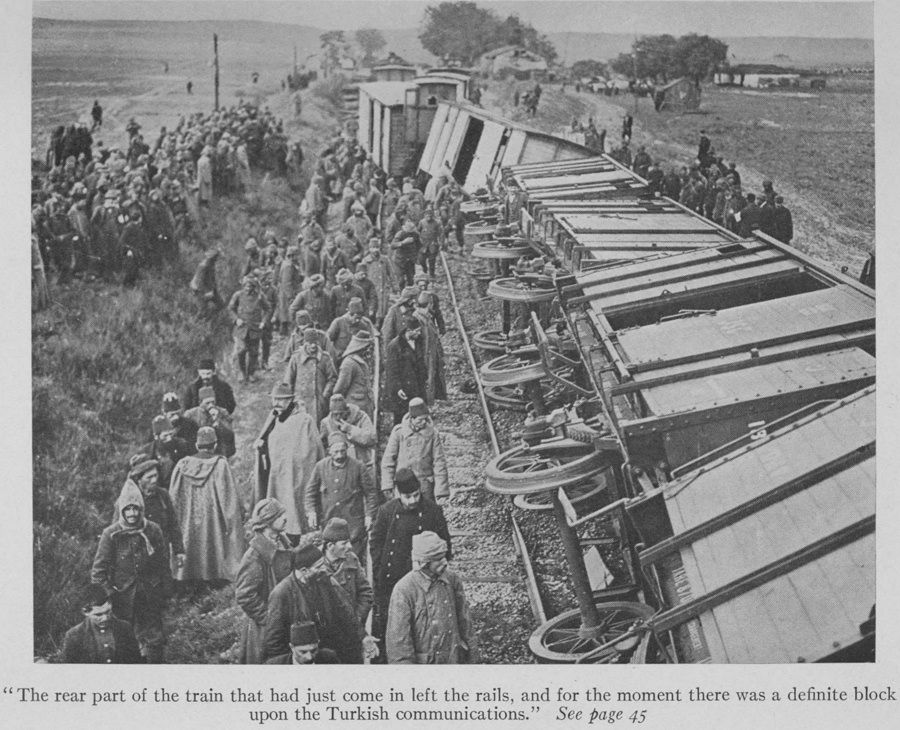

The Centurion returned to the station and was debating in his mind whether it would be possible to find some planks to serve as a gangway by which to detrain his horses. He felt sure that the Bosniak Shepherd would almost immediately receive orders for that portion of

![]()

45

the train containing the adventurers to be sent back in the direction of the base. Providence stepped in, however, to order the immediate adventures of the correspondents. The rear part of the train that had just come in from Lule Burgas on its way south in passing through the station left the rails, and for the moment there was a definite block upon the Turkish communications.

From midday to evening the situation inside the station itself was interesting enough. Added to the mass of fugitives that were passing by road there was this derailed trainload of panic-stricken deserters. The battalion of Redifs that belonged to the adventurers' train, as soon as they fraternised with the refugees, became obstreperous. With their usual improvidence or, should it be said, incapacity for all administration, the authorities at the base had started this battalion from Stamboul without an ounce of bread. Now that their train was apparently held up at Seidler, where there was nothing to be procured, the poor wretched

![]()

46

Redifs had the prospect of a forty-eight hours' fast.

The stories of the fighting which the panic-stricken deserters promulgated amongst them, also, had no very softening effect upon their nerves. The men paraded up and down the length of the train and gazed with longing eyes at the wagons packed with cases of stores which were the property of the Giaours. The panicmongers themselves were also feeling a little hungry.

It is not quite certain what happened, but the adventurers suddenly heard the voice of their bibulous Bey raised in anger. He was expostulating with the round dozen of Ottoman officers who had come down from Lule Burgas. It is quite evident, that in his more sober moments, the bibulous Bey had the command of very caustic language. If the roundness of the backs of his brother officers as he harangued them is any criterion, the sarcasm was biting in the extreme. Anyway he put some sort of life into the despicable crowd, and

---

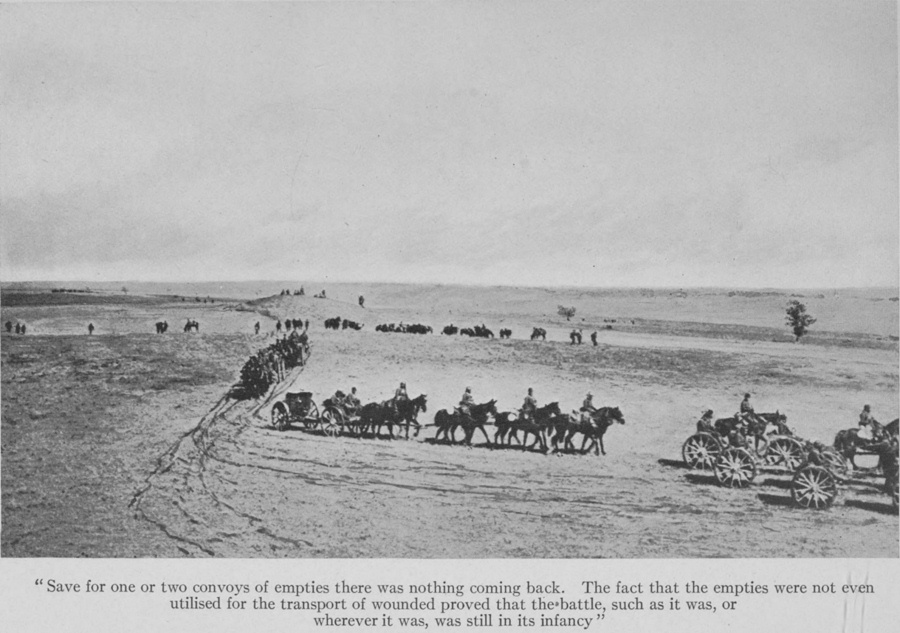

"The rear part of the train that had just come in left the rails, and for the moment there was a definite block upon the Turkish communications." See page 45

![]()

47

a certain number of the panicmongers were arrested and thrown into an outhouse and kept there under guard.

About two o'clock in the afternoon, another train arrived from the direction of Lule Burgas. This brought a breakdown gang with the more assuring news that the panic had only been partial; that it had been localised, and that confidence was re-established. It was observed all the same as a discount to this that there were a certain number of skulking forms in khaki in the train which did not belong to the breakdown gang. The expert with the gang, after he had looked at the wreck, said that it would take him four to five hours to make a deviation that would be practicable. His gang set to work with a rapidity which was quite remarkable in a country where manual labour moves slowly. A new ramp was thrown up beside the embankment, and the whole permanent way was lifted up and pushed bodily on to the new ramp.

As it was certain that the work would not

![]()

48

be effected in the time the expert suggested, the Centurion, finding that it was impracticable to think of detraining the horses, resolved to do a little reconnoissance on foot in the direction of Lule Burgas. A walk of three miles to what appeared to be the top of the ridge separating Seidler from Lule Burgas only produced that sensation of an interminable rise which will be familiar to those who have toiled up the slopes of the South African veldt. There was nothing that could be effected by dismounted reconnoissance, and the Centurion wandered aimlessly about until it was time to return. The events of the day had made a great impression upon him. During his stay in Constantinople, he had come to the conclusion that nothing but very quick and decisive successes could have maintained discipline in the troops he saw mobilised in the capital. Ever since the revolution the officers of the army, with the notable exception of one corps, had divided the attention they should have given to their military duties with political

![]()

49

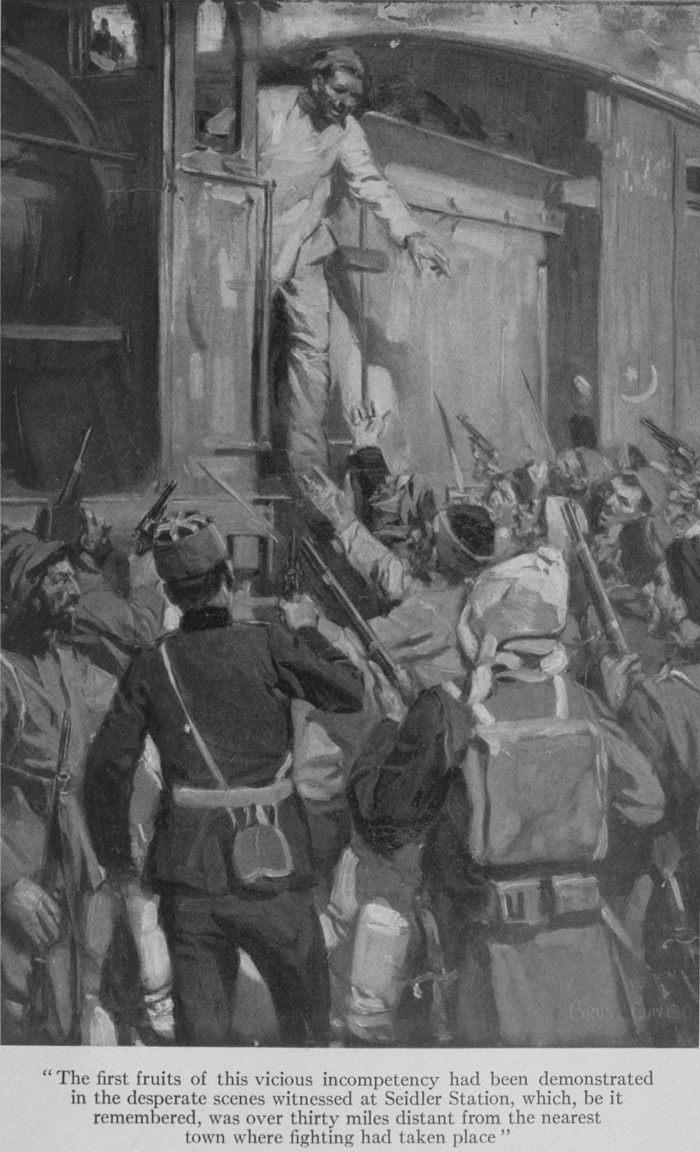

coquetry. The field of action of the politician is not a healthy training-ground for the soldier. The politician's sphere of influence and action is found in cities. The young officer of the Turkish army, therefore, instead of concentrating his mind upon his one essential duty, had fallen away after the flesh pots of political interests. The progress towards real efficiency in the Army which has been advertised by the late Minister of War and the Young Turk propaganda was mere eyewash. It was almost entirely confined to the purchase of material. The purchase of war-like stores meant heavy commissions for those empowered to make them. The Ottoman army, therefore, soon possessed in great quantities the material, arms, and other commodities upon which the highest commissions are paid. There was no real organisation or system of economic administration. The Adjutant General's department under this system was not as profitable as that of the Quarter-Master General's. Therefore it escaped attention.

![]()

50

Moreover the Turkish staff was obsessed with the strange heresy that a half trained Turk was the equal of any Greek or Slav soldier that should take the field. Modern warfare, however, cares little for tradition and martial instincts except as a basis for skilled workmanship. It is to-day a question of handling exquisite machinery. None but skilled workmen can hope to stand the strain. Those who claim otherwise are either knaves or fools. The first fruits of this vicious incompetency had been demonstrated in the desperate scenes witnessed at Seidler Station, which, be it remembered, was over thirty miles distant from the nearest town where fighting had taken place.

---

"The first fruits of this vicious incompetency had been demonstrated in the desperate scenes witnessed at Seidler Station, which, be it remembered, was over thirty miles distant from the nearest town where fighting had taken place"

![]()

51

BLANK

THE Centurion flattered himself that he could exercise control in all circumstances. In fact, he had been heard to say he would sooner be seen dead than for it to be apparent that he had lost his temper. There are, however, the exceptional circumstances which prove the rule. In the early hours of the morning following the events narrated in the last chapter, the train conveying the adventurers arrived at Tchorlu. It will be remembered that the Centurion was suffering from a severe attack of Constantinople influenza. He had been harried by the events of the previous day^ and felt keenly the fact that he had been forced, with the others, to go back instead of forward, when big events were taking place at the front. Now that Tchorlu was reached, the Bosniak Shepherd issued orders

![]()

52

that this was the place where the adventurers would detrain. Things were very uncomfortable that morning. There had been difficulty in getting any food other than canned tongue, the most appalling of nutriments, when it is the basis of four consecutive meals. The Innocent also had been troublesome. Half the night he had been arranging his makeshift table (which was a luncheon basket, not his own, be it remembered) in order to write volumes of copy. His arrangement of the table had interfered with the night's rest of the others. The Centurion dragged himself out of the compartment at Tchorlu to be told by the imperious John that somebody's servant had stolen his (the Centurion's) bridle. At this point he came very nearly forgetting all his principles in the matter of self-control. He told John to lead him to the man who had dared to touch his bridle. It was a pet bridle, a 9th Lancer bit, that he had had for nearly twenty years, and it hurt him to think that some knavish syce had stolen it in the night.

![]()

53

But his troubles did not end here. As he hurried forward to seize the delinquent, his foot caught in a point-rod and he tripped headlong into an ash-pit. Now the Centurion was not seriously hurt, but it was a culminating event in a sequence of trying circumstances. Therefore, when he found his pet bridle adorning the head of a scraggy looking Constantinople pony, he forgot all his precepts, and then there was the devil to pay. Three or four syces ran howling into the wilderness.

The pathetic part of the whole affair was that the master of the thief, who was totally incapable of telling one bridle from another, thinking that all looked like the things that you put into a horse's mouth to stop him with, was persistent in claiming the 9th Lancer bit as his own. However, he saw murder in the Centurion's eye and the matter was at last satisfactorily arranged.

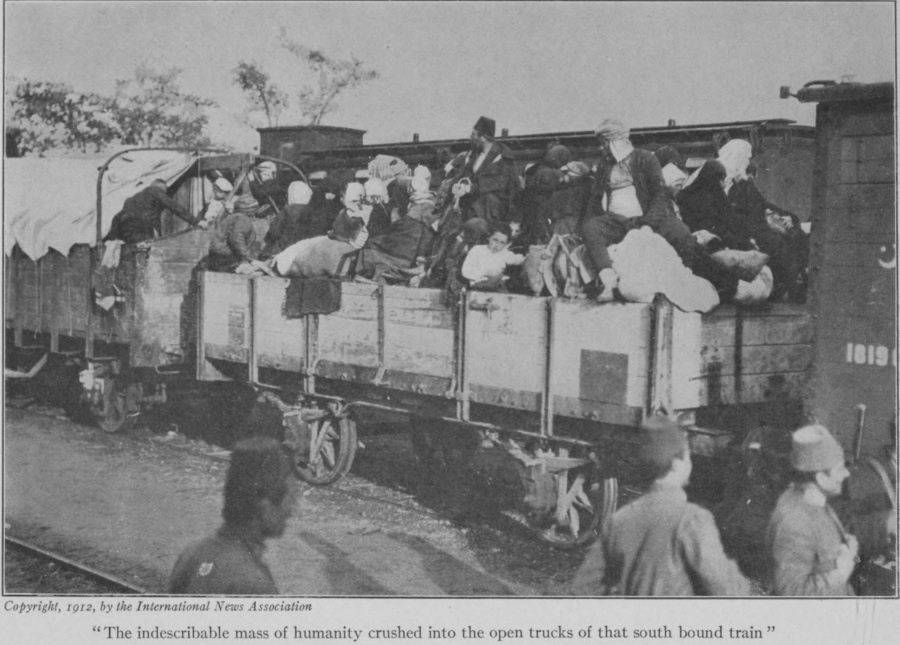

When the Centurion got back to the compartment, the orders were issued for the whole lot to detrain. In the meantime, the Innocent

![]()

54

was to be seen surreptitiously stealing down an adjacent train that was crammed full of refugees. It was said that this train was on the point of starting for Constantinople. The Innocent had a big envelope and a silver medjidie in his hand. With the air of a conspirator he was trying to find one or another amongst the refugees intelligent enough to convey his copious labours of the night before to the British post office in Constantinople. The Innocent was taking his labours very seriously. The Centurion, as he watched him searching amongst the indescribable mass of humanity that was crushed into the open trucks of that south bound train, wondered whether he realised that everybody's letters had gone south the night before.

The detraining at Tchorlu was a very serious affair. The Bosniak Shepherd and his staff were absolutely without official information. They did not even know what they would do with the thirty-odd ruffians that the train vomited forth, to say nothing of their

---

"The indescribable mass of humanity crushed into the open trucks of that south bound train."

![]()

55

stacks of goods, their horses and retinue of servants. Everything was bundled out on to the roadside. By the mercy of Providence it was not raining. Then came the question of transport. With the exception of the Germans, none had come supplied with transport. The old and wary knew they would be able to hire or purchase transport locally. The new and confiding had believed the promises of the Turkish staff that transport would be supplied them at the expense of the Government.

All things, however, right themselves in the end. Horses were taken from the trucks and hired transport was ultimately found. After about five hours' delay, the Bosniak Shepherd and his staff went out to prospect for ground in which to camp. The village of Tchorlu is some three miles distant from the railway station. The Bosniak Shepherd first reconnoitred in the vicinity of the village. This reconnoissance evidently proved unsatisfactory, as, after a lot of chat, it was decided that the adventurers should pitch their camp on the

![]()

56

side of the hill about half way between the military barracks, which are near the station, and the village.

The troubles of the adventurers endured in getting into that camp will interest few but themselves. The Centurion, who at least knew something about camps and camping, had his tent standing before the rest were unpacked. Then to him came the Corner Boy, the junior of the Bosniak Shepherd's staff. This Beggar-on-horseback seeing that the Centurion's tent was already pitched, came up with the request that it should be moved ten paces to the left. The Centurion, whom the events of the morning had made unapproachable, said something in Egyptian Arabic, which conveyed a sufficiency of meaning to the Corner Boy. His eyes flashed and he said he "issued the order" that the tent should be moved. The reply he got sent him off to the Bosniak Shepherd, livid with rage, to whom he explained that if it had not been for the politesse Turque due to a guest,

![]()

57

the Centurion would have been a dead man.

However, these little difficulties were ultimately settled and an astonishing encampment grew up on the slope of the bleakest and coldest hillside that was ever allotted to amateur soldiers. It was an interesting camp to watch. Fully half of the adventurers had never been in a tent before. They knew nothing of the ways of camping and horses. The tents sprang up in little groups and above each group there fluttered an indication of the nationality of the occupants. Cook-houses, horse lines, servants' quarters, were all indiscriminately arranged in the smallest possible space and it was obvious that if the spot remained a camp for any period, it would soon become so foul as to be untenable.

The several groups of adventurers seemed to reck nothing of this. The French settled down to the, to them, artistic business of adequate feeding, the Englishmen to devise means to work the Censor so as to fulfil the object of their missions, the Austrians and Germans to

![]()

58

make themselves as comfortable as they possibly could without the trouble of mixing themselves up with any dangerous adjuncts of war, the Russians, who are desperate persons, to fill note books with details that would be a joy to the hearts of a German Bench trying an espionage case.

It may be explained here, in parenthesis, that in accepting the assistance of these thirty adventurers, for the purpose of giving to the world a true and faithful history of their successes, the Turks had endeavoured to keep the business of correspondents en régle. They had drawn up a stringent schedule of rules and regulations by which to order and control the corps. The terms of this document were so stringent, that any man who signed them in good faith was, profanely speaking, putting his head in a noose. The old soldiers amongst the English adventurers put their heads together rather than into the noose and decided to draw up a set of conditions of their own, by which they intimated to the Turkish Staff that they

![]()

59

would never agree to the original conditions unless their own were complied with. The smiling head of the Censor's Department in the Shereskiet, who always had an eye to the main chance, and who was never too busy to find time for a fat meal, said, there and then, that the whole thing was a matter of form, and that the old and trusted soldiers amongst the adventurers might make whatsoever conditions they liked. All conditions were agreeable to his department, and so the matter was settled.

Arrived at Tchorlu the correspondents of the English papers were anxious to communicate all that they had seen in the last twenty-four hours to their journals.

The Dumpling took this matter in hand. The Bosniak Shepherd and the smiling head of the Censor's Bureau in Stamboul, however, were not the same person. The Bosniak was devoid of humour and imagination. He produced the official instructions. These insisted that all communications, including even private

![]()

60

letters, must be written in French. It was no use to insist that the Chief Censor had made promises in a diametrically opposite sense. The Bosniak's press formula was his Bible. The Dumpling, though he wrote French as easily as he spoke that language, had visions of the mutilation his best Moliere would undergo at the hands of English subeditors. He spoke his mind openly to the Bosniak on the subject with the result that the latter hardened his heart.

Then all the little world at Tchorlu began to write telegrams in French. Goodness only knows what they wrote about. No one else is likely to know because after twenty-four hours' delay the Bosniak returned all the telegrams with the intimation that, as there was no operator at Tchorlu that could telegraph in Roman, he suggested that the adventurers had better put their messages into Turkish. This was usurping the province of comic opera. The mental condition of the Dumpling gave grave cause for apprehension when he was

---

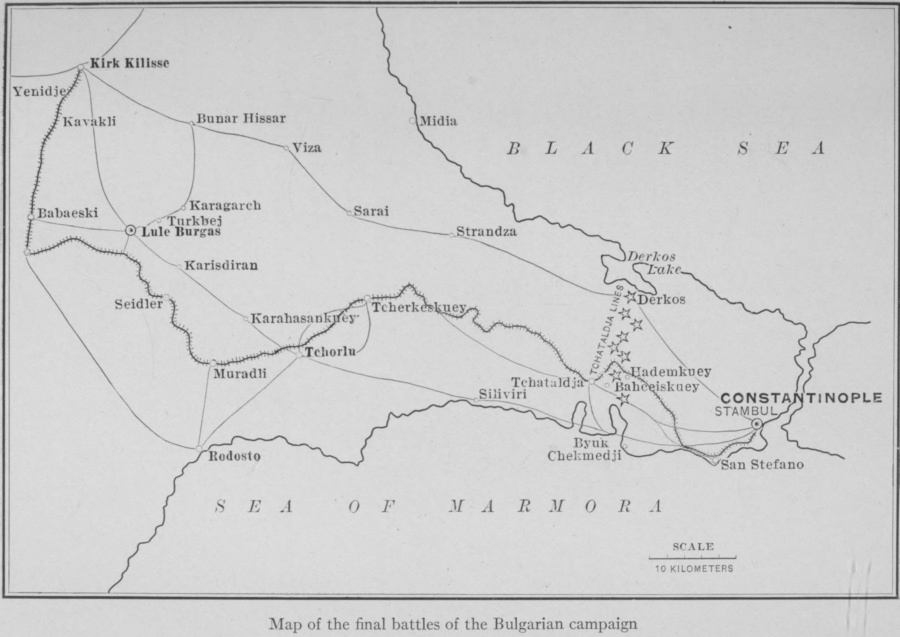

Map of the final battles of the Bulgarian campaign

![]()

61

made to understand that the French tongue was not a sufficiently high test for his paper's sub-editors, but that they would have to be tried in Turkish.

The Centurion only laughed as he intimated all languages were equal to his paper. He did not add that his already established dak was taking messages in English daily to the base. That was no one's affair but his own.

A considerable estrangement grew up at this period between the Bosniak Shepherd and his flock. The flock were now introduced to that exquisite mental torture known as polite Turkish passive resistance. The Bosniak had broken his second lance with his charges, and the heralds gave this bout to him. The Corps of Adventurers was then politely but firmly "gated." Orders were issued that no one was to leave camp without special permission and an escort. The Pera Corner Boy was placed on picket duty at the gates of Tchorlu village and everything living belonging to the adventurers' camp was denied entrance. The Corner

![]()

62

Boy was really "laying" for the Centurion. The latter, however, was not walking into any such foolish trap with his eyes open. He just sulked and nursed his distemper in his tent. The Innocent, however, improved the shining hour by learning to ride a superannuated grey pony and committing Von der Goltz and Yorck von Wartenburg to memory. Nothing but the shortest cut to the complete war correspondent would satisfy his ambition.

Then something happened. No one beyond the parties concerned quite knows what it was, but the Centurion sauntered down to the Bosnians tent. He had evidently conquered his cold. The next thing that was known was that the Corner Boy was seen taking the road for Constantinople. John says that he was not consulted in this affair. For once John spoke the truth.

The adventurers had barely got under canvas when the weather changed. Chill winds blew. This brought up rain and the cold suddenly became arctic in its severity. This

![]()

63

weather is to be expected in Thrace in early winter even as far south as Tchorlu. The snow and frost-steeped winds from the great Russian steppes sweep across the Black Sea and freeze Thrace tight. The weather, however, is rarely settled. To-day it may be arctic with feet of frozen snow, to-morrow the soft zephyrs from the Mediterranean may be sweeping up the Marmora and the snow melting in a heat equivalent to that of an English August.

Old soldiers have an adage to the effect that in winter the worst hut is better than the best tent. The adventurers began to feel this as the driving north wind swept up the slopes of their chill camping ground. There were certain amongst the correspondents who had essayed to make this campaign after the manner of the Spartans. They scorned both tent and bed. The cold, however, found the joint in their Spartan harness, and they joined in a request lodged with the Bosniak, that, if Tchorlu was to be a standing camp, the adventurers

![]()

64

at least might be allowed to take up winter quarters in the village.

It is now time to introduce the Popinjay. He was most remarkable for his independence and the excellence of his servant "Joe." Joe was the most expensive dragoman on the list of Pera knaves that batten on Western curiosity and ignorance. Joe is also the best servant to take into camp that any man could desire. He was eminently suited to the Popinjay, to whom expense was no object when balanced against personal comfort. The Popinjay, however, had that estimable quality of never being really happy and comfortable until he had a wisp of fellows round him to share his creature comforts. Joe had foreseen this cold and had fitted his master's tent with charcoal braziers in scientific profusion. The Popinjay was no niggard in his hospitality. During the cold snap this tent became the club house of the British section. Joe served cordials with lavish hand. His master smiled benignly, and lightened his guests'

![]()

65

pockets through the medium of a game called poker.

The necessity of rallying round the Popinjay's fire induced the British adventurers to bring pressure to bear upon the Bosniak to organise a move. There were other reasons besides the cold. The Tchorlu valley was fast becoming a gigantic concentration camp. Division after division seemed to be marching in. The rough bivouacs of the soldiers were creeping closer and closer to the area in which the adventurers were domiciled. The Anatolian Redif, estimable fellow though he doubtless is in many ways, is not an ideal neighbour in a sanitary sense. This fact was becoming alarmingly apparent to the adventurers, when suddenly the Bosniak sailed down upon them and informed them that they must hold themselves in readiness to strike camp at any moment as Abdullah Pasha had issued instructions that they were to go into standing camp in the village of Tchorlu.

Beyond a rather cryptic statement made officially

![]()

66

by the Bosniak Shepherd to the effect that "the Turkish army of the offensive had found the advanced line of Adrianople—Kirk Kilisse—unsuitable for the concentration, and that it had, therefore, fallen back upon the line Baba Eski—Lule Burgas—Viza," no single word of direct information had been vouchsafed to the adventurers. A smattering of the facts, however, filtered through, and it was realised that Adrianople was already invested and that the Bulgarians and Turkish advance guards were in touch in front of both Lule Burgas and Bunar Hissar. As yet, however, the sounds of the guns were not audible at Tchorlu. The Centurion, who was now almost entirely recovered from his distemper, had set the sound of the guns as the signal at which it would be expedient to break away from the Shepherd's flock.

---

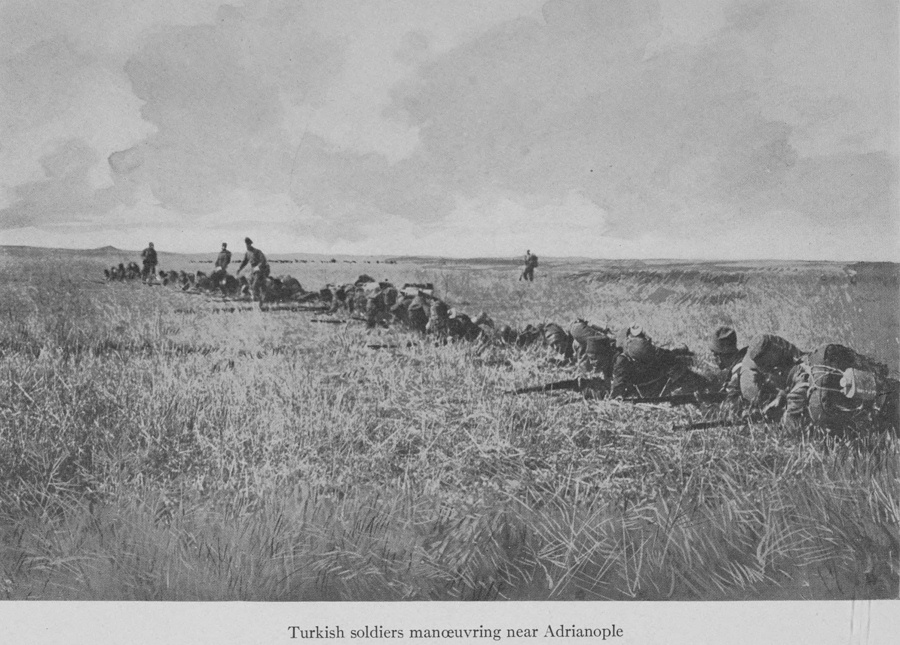

Turkish soldiers manoeuvring near Adrianople

![]()

67

STILL BLANK

THE village of Tchorlu, contrary to the usual run of Turkish hamlets, is built upon a hill, or rather upon the summit of one of the rolling downs which are the features of this portion of the Peninsula. It is a typical Turkish township, with its narrow streets, cobbled roadways and tumble-down, ramshackle, over-hanging houses. For a village, it is of considerable importance, as it taps the three main arteries and commercial roads leading from Adrianople to the Sea of Marmora. It is also a strategic point of considerable military value. In fact, it is understood that Marshal Von der Goltz, the military mentor of the Turkish army, favoured the position of Tchorlu as the most important in the whole Peninsula, Tchataldja included. Although the railway junctions further north covered by

![]()

68

Lule Burgas possibly produce a more artificial strategic value, yet on the merits of purely natural positions plus the possibilities they present of changing from the defensive to the offensive, the Tchorlu terrain has much to commend it. It was also a garrison town, and had been largely used for the purpose of the hurried mobilisation. It had been selected by Abdullah Pasha as the headquarters of the army in the field during the concentration.

The populace, like those of all Thracian townships, was of course mixed. Mingled with the true Turks were Armenians, Jews, Greeks and Bulgarians. It was, however, a prosperous place, and having received the mission to billet the adventurers in the town, the Bosniak Shepherd proceeded to find accommodation. In carrying out these duties, the Shepherd was perfectly sincere and hardworking. Of course, like other Turks, he had not the remotest idea of the nature or character of the accommodation that even the meanest European would require. When he entered

![]()

69

the town to find the billets, he had only two ideas fixed in his head. These were that all it was necessary to give a European was a roof and a bed, and that his two Russian adventurers must sleep under the same roof as himself. It was firmly embedded in the Tartar lining of his brain that the two Russian correspondents were Bulgarian spies. On one or two of the occasions when he had lapsed into confidences, he had been heard to remark that it would be an astounding thing if his Russian guests survived the vicissitudes of the campaign.

The Bosniak Shepherd found the billets for the British adventurers in the chief han in the village. As there may be many who have not had experience of a Turkish han, it will be as well to give some little description of these dingy hostels. The han is really a relic of the posting days. The serais or posting houses were always built as rectangular enclosures. The origin is quite obvious. In the old days the roads were infested with brigands and

![]()

70

footpads. Every caravan was armed, whilst each posting house of necessity had to be a fort. During the night the animals were stabled within the rectangle, whilst the grooms and attendants slept in little receptacles below the banquette of the walls. For travellers of better degree, special rooms were added. Custom or convenience had it that these rooms should be adjacent to the gates. Thus it was that the local architects came to place the guest-rooms above the gates. You will find that this custom survives throughout the East. You may go from Bosnia and Herzegovina right away through Persia and Central Asia until you finally finish in Manchuria, and you will find traces of this old system in most of the local post houses that you patronize.

Of such was the general design of the han in which the British group of adventurers were billeted. The landlord had perhaps half a dozen small cubical rooms on the landing above his entrance gate. Into each of these tiny bandboxes were squeezed two or three

![]()

71

iron framed beds. The beds were so close to each other that there was no space left for anything else in the rooms.

The landlord, a fat, slobbery Greek, received his new guests with every show of delight, and well he might, for a clientele of fifteen or sixteen Englishmen meant wealth to him. The majority of the adventurers just looked at their rooms and at once decided that they would billet themselves. They refused to have anything to do with the filthy han, the beds of which were crawling with vermin, and went out with their dragomans to forage for shelter. A few remained in the han; amongst these was the Centurion, whose knowledge of Turkey dated back some years. He immediately organised his servants and without any reference to the landlord, threw each of the beds, mattresses and all, out of the window into the street. The oily smile died on the Greek patron's face. He essayed to stay the wreck of his beds and the dismantling of his room. The result of his ill-timed interference was

![]()

72

that he was gently dropped down the stairway. As soon as the existing furniture had been cleared from the room, the latter was washed down from ceiling to floor, sprinkled with disinfectant and then furnished with the Centurion's own camp furniture.

In the meantime, mine host had gone weeping to the Bosniak Shepherd. The ex-Deputy of the Turkish Chamber was conducted into the street to the spot where the Turkish soldiery had already begun to make away with the Greek's bedroom furniture. He looked at the wreckage on the ground, then up at the window. It is not often that the Turk will allow any expression betraying feeling to pervade his countenance. Never before had a Turkish officer been seen by the Centurion with such an expression of utter hopelessness as that worn by the Bosniak Shepherd, when he surveyed the wreckage. What he said to the Greek was overheard by John. In one expression he conveyed to the unlucky host that he was unable to cope with the eccentricities of

---

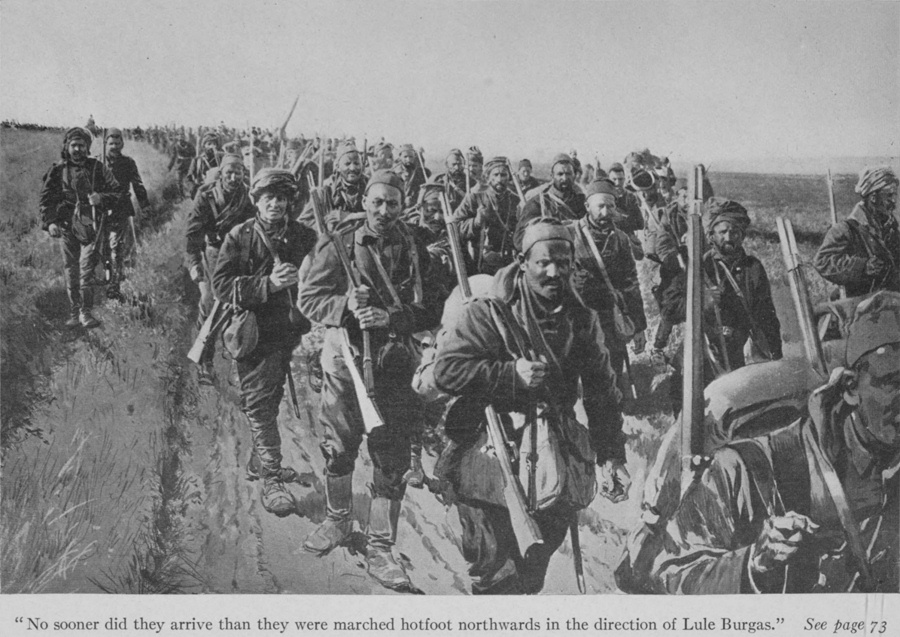

"No sooner did they arrive than they were marched hotfoot northwards in the direction of Lule I-!urgas." See page 73

![]()

73

his charges. His one sentence was: "These Englishmen are inexplicable."

It was no easy matter getting into the village of Tchorlu that morning; the entire valley between the town and the barracks had become one great camp. Battalion after battalion was met marching through the town. The majority of these troops belonged to Torgad Shevket's Second Army Corps, the last divisions of which were being hurried via Siliviri and Rodosto from the Dardanelles and Smyrna. They had no time to allow the mud of Tchorlu to cake on their boots, for no sooner did they arrive than they were marched hotfoot northwards in the direction of Lule Burgas. For the most part they were good-looking troops, Nizam battalions that had been stiffened with first class Redifs. They were not so under-officered as the units that had mustered in the Constantinople area. They had been mobilised for the Italian war.

They were, however, looking a trifle tired and travel-worn, and one would have liked

![]()

74

to have seen them halting for at least a day with the Redif battalions already in camp at Tchorlu. The Turkish arms, however, had need of its first line troops in the neighbourhood of Lule Burgas. How desperate was this need was not yet appreciated in the billets of the adventurers. It will be remembered that October 23rd had been the crucial day of the campaign at Kirk Kilisse. It was now October 28th. Although precise information was not yet available in Tchorlu by this date, two out of three divisions of the First Corps d'Armee, had been defeated by the Bulgarians just south of Kirk Kilisse and were in broken retreat upon Baba Eski.

Amongst the adventurers two groups had provided themselves with motor cars. The Centurion and the Diplomat shared one car, while the Dumpling and the two Jew's Harps were the proud possessors of another. It had been impossible to convey the cars by train and they perforce had to make the journey by road. For some reason, which has never been

![]()

75

clearly explained, the Chief Censor at Constantinople would not allow the cars to start until two days after the train had left. The doctors had advised Jew's Harp Senior to stay behind for a day or two, as he was hardly well enough to take the road.

The two cars arrived at Tchorlu the same day that the adventurers went into their town billets. The Centurion met his car in the street. To his astonishment, he found seated in it a cinematograph operator with all the heavy parts of his picture-catching machine piled about him. The Centurion was speechless. When he had issued his orders before leaving Constantinople, he had impressed upon his chauffeur that every available pound of weight that the car could carry over and above the driver was to be utilised for the carriage of petrol. He had realised that once they were with the army in the field, petrol would be to him of the same value as its measure in gold dust. It must be remembered that petrol is not a commodity to be found in every

![]()

76

Turkish village. It is probable that not more than a few spoonfuls could be bought between Stamboul and Adrianople. It was, therefore, essential that the car should leave its base loaded to the uttermost straw with the precious fluid. The Centurion, biting his lip, took the unlucky passenger to task. He said that he had only done what he had been told by his master who was a passenger in the other car. The cinematograph monger's master proved to be one of those free lance opportunists who invariably arrive at modern theatres of war in the guise of journalists to see what is to be made out of rollicking adventure. They are usually adept in living upon the country. Here was a case in point. The man who ran the cinematograph had so ingratiated himself with the Chief Censor in Constantinople that the latter had offered him, with his operator and material, space in the car of a man to whom every square inch was of vital importance. The Chief Censor is not to be blamed; he could hardly be expected to know much

![]()

77

about the requirements of journalistic enterprise, or he would never have sanctioned the cars at all. But what is one to say of the man who accepted the Censor's offer, and in so doing almost fatally handicapped a legitimate correspondent? His action went within an ace of wrecking the entire fabric of the Centurion's carefully worked out plans.

It had taken the cars exactly three days to reach Tchorlu from Stamboul. The distance is not much more than forty miles. The state of the roads they came through must be seen to be believed,—they came, it must be remembered, by the main Adrianople road, which is reputed to be the best in Turkey. The experiences were entirely desperate. In places bullocks had to be hired to haul the cars out of the mudholes into which they had fallen. Before the cold set in, the weather had been wet. The cars had started when this bad weather had just set in.

There was a considerable flutter in the British dovecots at Tchorlu, when it was found

![]()

78

that Jew's Harp Senior had not come up in his car. The cinematograph-master told a story which added to the general disquiet at the Jew's Harp's non-arrival, and fairly drove the Diplomat into a frenzy of alarm. It appears that Jew's Harp had started in his car in the company of a Turkish officer, who had been specially deputed to convey him to the billets of his colleagues. The second day out from Constantinople, Jew's Harp's car had stuck in the mire in a manner that seemed hopeless. Jew's Harp Senior, as his sobriquet suggests, is a man on wires. It so irked him to stand by while animal draught was employed to drag his conveyance out of the slough, that he suddenly struck off on foot followed by his officer bear-leader. He disappeared into the mists of night, just shouting back to the others to make the best of their way up to Tchorlu, as he was going to discover another and more rapid means of getting to the front.

The Diplomat would not believe a word of it. He argued that all his contentions were

![]()

79