CHAPTER XXIV. THE ALBANIANS.

Albanian Ferocity and Chivalry - A High Sense of Honour - Language - Religion - Customs - Lack of Unity - Outrages

THE Albanians may be divided like the Scotch. The Highlands of the

North are inhabited by clans; in the more fertile Lowlands of the South

the clan system disappears.

And as the Scots, centuries ago, whatever their differences were, met on common ground in hatred of the English, so the Albanians find unity in one sentiment - hatred of the Slavs.

The surrounding nations have been so afraid of them - because of their ruling, inextinguishable passion for fighting - that Albanians have been much left to themselves. The absence of roads, the perilous mountain passes, the tribal jealousies have made each little region, clasped in nigh impenetrable mountains, self-contained.

A fierce chivalry is everywhere. A woman can travel safely in Albania because she is weak. The Albanian, however, would no more hesitate to shoot a man for a fancied insult than he would hesitate to shoot a dog that barked at him. There is a stern independence.

The Albanian has no art, no literature, no

![]()

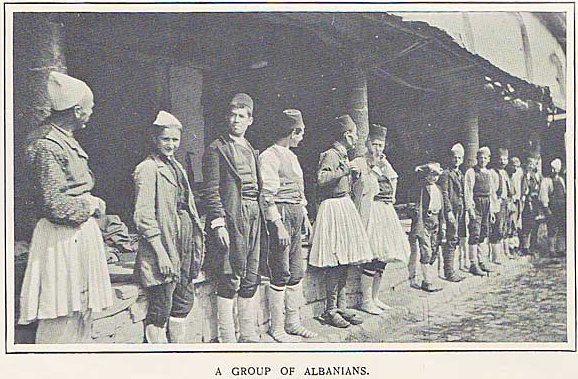

A GROUP OF ALBANIANS.

![]()

257

national politics, no "Albanian cause," no individuality as an Albanian in contradistinction to neighbouring races - except that, above all, his honour is sacred. But within his honour is included much. He is not a thief - though he is entitled to the belongings of the man he kills. He will not take the advantage of robbing a man who is gunless. That touches his honour. He will not touch a woman, for by the law of tradition he is entitled to shoot a man who interferes with his womenkind. So he keeps both his eyes and his hands off the women of others. It is not fear of consequences that makes him moral - the whiz of bullets is no deterrent to the Albanian - but his honour is touched by the reflection that in attacking a woman he is attacking somebody who cannot retaliate.

Again, an Albanian's word is even better than his bond. My experience showed that when an Albanian said "I'll do it," he never failed in the performance. He will lie volubly in endeavouring to obtain the better of a bargain, because he is convinced that you also are lying, and that, therefore, you and he are on equal ground. When the bargain is made he is on his honour, and for his own sake, not for yours, he is honest.

The language is formless and bastard. There is a national alphabet, but it is hardly ever used. In one part of the country Latin characters are employed, whilst in another part Greek characters are common. In some districts much Italian is incorporated into the language, in other districts much Greek, and in others much Slavonic. The conse-

![]()

258

quence is that Albanians living fifty or sixty miles apart have the greatest difficulty in understanding one another. Further, there are marked racial differences between the Gheg Albanians, who live in the wild north, and the Tosk Albanians of the less rugged south. You would conclude they were different nationalities. So they are. Indeed, it would be quite easy to prove that the Albanians are not one people, but half a dozen peoples. They are the children of desperate races, defiant and outlawed, who were neither exterminated nor absorbed by the conquerors, but retained their independence by secluding themselves in the fastnesses of the Albanian mountains.

The tribes of Albania have no common religion. Some are Moslem in faith, and some Christian. There are both faiths to be found in the same clan. The most important of the northern tribes, the Mirdites, is Christian: Roman Catholic. Down south the Albanians are Christian, and, being contiguous to the Greek frontier, favour the Orthodox Church. The Moslem Albanian is influenced by his Christian neighbours. He drinks wine, and is particularly fond of beer - I was able to get bottled lager from Munich - and he swears by the Virgin.

The Albanian is ignorant and superstitious. He believes the hills are inhabited by demons, and is convinced that the foreigners, especially the Italians, only want to push out the Turks to get possession of the country themselves. They hate dominance, and would rather have the purely nominal rule of the Turk than the stringent rule they might expect

![]()

259

from Italy or Austria. The agriculture is poor, and is pursued with no intention further than to supply immediate needs. There are no manufactures, except the little silk-weaving at Elbasan. As for trading, it is not understood.

The customs of the Mirdites and of the Tosks vary considerably. The Mirdites attempt some semblance of government, but all that is done is decided by the chiefs of the more powerful clans. Their laws are Spartan-like, and often cruel. A curious thing is the practice of having adopted brothers. Two men swear to be brothers. The relationship is regarded as so fraternal that the children of either are not allowed to come together in marriage. The Tosks are more industrious than the Mirdites, and some of their Beys rise to comparative wealth.

Though the Albanian would like to throw off even nominal subjection to Turkey, it is this subjection which prevents the whole land becoming a cock-pit of murder and pillage between the clans, and it also keeps off the Italians, who certainly would like to capture the country. So Albania does not count for much in the Balkan problem. Of course, in a general Macedonian uprising the people could and would harry the Turks. But as they cannot combine, they have no political influence.

It would be strange if in so warlike a land there were not outrages. The first consul sent by Servia to Pristina was murdered by the Albanians within six months because he refused to take his departure at their behest. Because of personal dislike they expelled the Turkish governors of Pristina and

![]()

260

Prisrend. The Turkish authorities took no notice. Three noble Albanians

at Nich, after a copious dinner, took their guns, and started firing upon

the farmers. One was killed outright, and another wounded. Some days afterwards

two of them violated the pregnant wife of another farmer. They gathered

the children round a large fire, made them sit down, and then, arming themselves

with shovels, threw the embers upon their arms and legs. Sofia, an Albanian

bandit, chief of a band of ten men, demanded from the Mayor of Doumuntzé

575 francs for the ransom of the village, in default of which the village

would be burnt. Sofia had exacted the same amount of ransom the previous

year. At the same time he invited a rich man whom he had carried off the

year before to pay a second ransom of 575 francs under pain of death. Finally,

the Mayor, under pain of death, had to supply fifty dozen Martini cartridges.

In a vineyard near Uskup a Christian passed by a band of fifteen Albanian

Moslems who were smoking and drinking coffee. Said one of them, "Suppose

we kill him?" The Christian was killed.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]