198

CHAPTER XIX. HILMI PASHA, "BONHAM'S BABIES," AND SOME STORIES.

The Viceroy of Macedonia - Major Bonham and the Gendarmerie School - "Bonham's Babies" - The Salonika Explosions - Tales of Greek and Bulgarian "Bands"

HILMI PASHA, the Inspector-General of Macedonia, is one of the most

striking and remarkable of men. He stands between Turkey and the European

Powers. It is his duty to conciliate Europe, but yield as little as possible.

I am sure he has the true interests of Turkey at heart, and would be glad

to see the Macedonian problem settled; but he realises the absolute hopelessness

of the task which his Imperial master has set him.

I was introduced to him by the British Consul-General at Salonika, Mr. R. W. Graves, who has the widest, most acute appreciation of Macedonian affairs possessed by any foreigner. Hilmi Pasha is tall and thin, but with a feverish vitality. He would be thought haggard were it not that the eyes-large, piercing, inquisitorial - are full of fire. They attract and they rivet.

Hilmi is a tremendous worker. He is at his desk at daybreak, sees secretaries, dictates despatches, receives a constant stream of callers, smokes endless

![]()

198

cigarettes, drinks innumerable cups of coffee, never takes exercise, keeps on working till midnight.

He is a nervous man. All the time he is speaking his long fingers are twitching almost convulsively. He speaks rapidly, but never dogmatically; always with an appeal to your intelligence, as a sensible man, that the view he presents is the correct view. If you did not see him in a fez you would imagine him to be a Jew. There is a Semitic touch about his features. He has the Hebraic nose, but he is really an Arab.

Formerly he was Governor in Yemen, and ruled with a rod of iron. Now he rules Macedonia with a skill that is wonderful. Though ever under the eye of foreign representatives, he is never lacking in suavity, whilst constantly guarding the interests of the Sultan.

For three years Hilmi Pasha has been Viceroy in Macedonia. With all the jarring elements, he knows better than anyone how futile have been the endeavours to secure anything in the nature of abiding tranquillity. He would retire from all the brain-racking complications were he not commanded by the Sultan to remain at his post.

Now one of the troubles in Macedonia is that the soldier police, the gendarmerie, are ignorant, illiterate, and so badly and irregularly paid that they must live by blackmail, and that they never find out who commits a crime if it is made worth their while not to do so. To remedy this there has, under foreign pressure, been established at Salonika a Gendarmerie School. It is under the charge of iajor

![]()

199

Bonham, a highly capable officer possessing the rich faculty of persuading the Turks to do what could never have been secured by dictation. The recruits are jocularly known as "Bonham's Babies." He is a genial father to them, and the affection felt for him by the raw, sheepish-looking peasants who are brought in from the mountains to be licked into shape is not without its amusing side.

But Major Bonham has hardly a fair chance. Rarely has he a man under his charge for longer than four months. It is, therefore, little short of amazing how during those four months a hobbledehoy can be straightened up, taught to march in the German style, and have some character put into him. But there is the fear, and indeed the probability, that when such men get back to their villages, and especially under the influence of their soldier associates - who have a contempt for new-fangled European ways - they will speedily relapse into their old dilatory slouch.

I spent a morning at the school. The poor physique of the men impressed me. Yet these were the best that could be picked. Of the last batch of 300 peasants that were brought in, 90 per cent. were rejected because of their lack of staying power.

Though the material is bad, Major Bonham is pleased with the results. The Turkish authorities have no enthusiasm for what is being done at the Gendarmerie School, and it is with reluctance that they provide funds for its maintenance. The men themselves, however, are keen. They are worked hard, but they never get kicked, and they value a kind

![]()

200

word. Major Bonham has established a mess-room for the Turkish officers. Till this big, cheery Englishman came the officers had no place but the cafés in which to spend their spare time. Now they have a large decorated and carpeted room. There are plenty of newspapers. They drink nothing but water, and they devote their evenings to learning French.

It inclines one to smile to go into the classrooms and find between two and three hundred Turkish men learning to read and write - great big fellows laboriously and awkwardly making Turkish pothooks and slowly going through the Turkish equivalent for C-A-T, cat. But they learn quickly, and as soon as they master the simplest words their interest is stimulated by being given stories to read. They take turns to read. Thought and attention are cultivated by someone being called upon to repeat the story from memory. There is mirth at the muddlers. But interest never flags. The more promising men are retained as instructors to the newcomers. The others, at the end of a few months, are drafted to frontier outposts. But I believe the benefits of the school soon ebb and disappear.

These gendarmes - who are distinguished by wearing light blue jackets, in contrast to the dark blue worn by those who have not had European training - reside in districts which are periodically dotted with outrage. Whatever is done will be misrepresented by either Bulgarians or Greeks.

The Salonika explosions will not have faded from public recollection. A number of Bulgarians while

![]()

201

driving past the Ottoman Bank, suddenly threw some bombs at the soldiers and gendarmes employed to watch it. Three soldiers were killed. Three of the conspirators were also killed and three wounded. The Bulgarians fired the bank with dynamite, attempted to destroy the Turkish Post Office, threw bombs in various parts of the town, and put out the gas. It was found that an underground passage had been made from a shop on the other side of the street to the bank, and a mine, loaded with dynamite and connected with the shop by electricity, constructed. It must have taken months to make this passage. The earth was carried away in handkerchiefs and small paper parcels and thrown into the sea or elsewhere at a considerable distance from the spot. A complete plant for the manufacture of bombs was discovered, including thirty-six quarter-pound jars of nitro-glycerine.

After the outrage between thirty and forty Bulgarians were killed by the Turks through resistance to arrest or in attempted flight. The participation of a Bulgarian merchant of wealth and position in the outrages proves that it is hardly possible for any Bulgarian of whatever standing to escape the clutches of the Komitaji.

Following the events at Salonika, all the Bulgarian schoolmasters in the province of Dede Aghatch put on deep mourning for forty days.

At the village of Banitsa, near Seres, two "bands" were surrounded by troops, and after severe fighting most of the "bandsmen" were killed, as well as most of the male inhabitants who

![]()

202

were in the village at the time. Some thirty or forty women were violated and most of the houses burnt, only twenty-two out of 170 being left standing. In the sanjak of Seres 1,600 houses were burnt. Of these only 109 were Turkish; all the rest were Bulgarian. At the village of Konski three peasants were tortured by the Turkish officers searching the village for arms. They were stripped, bound, and laid upon their backs on red-hot embers, while a woman was burnt on both arms. All this was by way of retaliation on the Bulgars for the Salonika outrage.

Mr. Consul-General Graves, writing to the British Foreign Office, stated that almost all the crimes committed by the Bulgarians had been provoked by attempts on the part of the Patriarchists (Greeks) to profit from the present misfortunes of the Bulgarians by recapturing schools and churches which had passed into their hands. The Bulgarians, of course, retaliated. Later he wrote that among the documents found on the body of a Bulgarian revolutionary were "half a dozen copies of a petition drawn up in Bulgarian and Turkish to be signed by the inhabitants of Patriarchist villages, asking to be placed under the spiritual jurisdiction of the Bulgarian Exarchate." There were also instructions in cypher as to the means to be employed in forcibly obtaining signatures to these petitions.

In the village of Osnitsani an old man of sixty was decoyed out of his house by a "band" wearing the gendarme uniform. They demanded lodging for the soldiers, who, they said, had just arrived in the

![]()

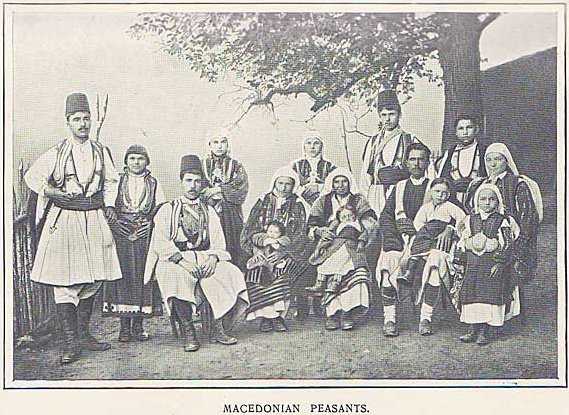

MACEDONIAN PEASANTS.

![]()

203

village. The old man was killed with knives near the church; there were sixty-five wounds on his body. Before killing him the "band" tortured him inhumanly, split his skull, drove the knife through his ears and eyes, and ended by throwing a heavy stone on the head of the victim, already beaten into a shapeless mass. A fortnight before, the poor old man, who was the most learned and most important Christian in the district, had gone to the episcopal chief, his eyes filled with tears, and had stated that agents of the Komitaji had demanded from him, with threats of death, the seal of the village, in order to seal a petition addressed to the Exarch that the village might detach itself from the Patriarchate!

In two villages between Salonika and Yenijé a Bulgarian "band" was called in by the Greek villagers in consequence of the oppressions and exactions of the Albanian guards, shepherds, and other hangers-on of several large Turkish landowners in that district. A fight took place, in which the Albanians lost three killed. "It is, indeed," says Mr. Consul-General Graves in reporting this occurrence, "a curious inversion of the natural order of things by which the insurgent band is called in to punish or avenge the crimes of the nominal protectors of life and property, while the last to appear on the scene are the military and police, who content themselves with reporting the dispersal of the rebels."

Colonel Verand, the chief of the French representatives in Macedonia, has stated that he and his officers were much impressed by the barbarous ruth-

![]()

204

lessness of the Komitajis and by the powerlessness of the Turkish authorities to protect those who had incurred their vengeance.

The Turkish Ambassador in London told Lord Lansdowne at the latter end of 1904: "It was notorious that for some time past 'bands' formed in Greece came to carry out their designs in certain European provinces of the Turkish Empire. The Greek Government... tried to represent the incursions of these 'bands' as reprisals for misdeeds committed by Bulgarians against Greeks." Despite their assurances to Turkey, the Greek Government found themselves unable to take measures to prevent these incursions, and meanwhile a Macedonian Committee founded in Greece openly issued revolutionary proclamations, and fresh "bands" were formed to render the movement more active. Collisions were constantly occurring between the Turkish troops and Greek "bands," while the Bulgarian "bands" made savage reprisals on the Greek. At Vladovo three Patriarchists were murdered by Bulgarians because they would not refuse to pay the hejaz duty (on bringing and selling wood from the forest) as the Bulgarians directed, but continued to bring in wood. A few days later another Bulgarian "band," furious at their loss of four killed and three wounded in a fight with a Greek "band" that day, entered the village of Girchista, and murdered the Greek schoolmistress and six other persons.

These stories are not mere tales brought to my ears. They are all taken

from reports written by British Consuls to the British Foreign Office.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]