111

CHAPTER XI. IN THE LAND OF THE TURK.

Adrianople - Mistaken for a Person of Distinction - The Real East - A Mixed Population - The Mosques - A Great Fire - A City of Terror - An Armenian's Adventure - Celebrating the Sultan's Accession - A Turkish Exhibition - Turkish Time - A Visit to the Vali

IN the blackness of the night the train slowed and drew long breaths

at Hermanli. We were still in Bulgaria, and the frontier guard was smart

and alert.

On went the train through the dark. There was a fire on the bank. At attention stood sallow, ill-clad, ill-washed, down-at-heel, and fezzed soldiers. We were in Turkey.

With groans the train pulled up at Mustapha Pasha, ill-lit compared with Hermanli, and the guard slouched on either side of the carriages whilst a search was made for contraband - they crumpled my shirts, and were suspicious about my soap-box and passports were inspected and returned. On again, in the land of the Sultan. At every half-mile, at every culvert and every bridge, blazed a fire, and there was a group of melancholy Turkish soldiers.

Not so long before this the Bulgarian revolutionaries had made an attempt to benefit their friends in Macedonia by blowing up a bridge on this line to Constantinople. Now the Turks were keeping watch.

I was expected at Adrianople. The train had

![]()

111

hardly slowed when I was saluted by a black-whiskered, red-fezzed man. "Sir," said he, "I am the dragoman to the Consulate of his Britannic Majesty." Behind him stood the Consulate kavass, a Circassian, tall and as fair as an Englishman, handsome in his blue uniform and gold-strapped sword, and with the British arms on his fez. There was a scrimmage and a babel among the Turks over passports, and a further inspection of baggage. The officials mistook me for a person of distinction. They saluted and salaamed. I offered my passport. They would not trouble to look at it; the coming of the effendi had been telegraphed from the frontier; also news came a fortnight before from the Turkish representative at Sofia that I was "a great English lord," and must be shown courtesy. Should I open my baggage? The officials would not think of it. I saluted; they salaamed. Soldiers would deliver it. A carriage and pair was waiting.

Adrianople is two miles from the station. The night was pitch. Not a soul was about but the men on guard. They peered at the carriage, but when they saw the kavass they shuffled to attention. Over the cobbles we rattled through that city as of the dead. No lights save dim flickers in the guardhouses.

While the morning was yet fragrant I was out in the narrow, crowded streets. Their meanness was saved by the dome of many a stately mosque, and the graceful and frail tapering of many a lofty minaret piercing the blue vault,

![]()

112

The scenes were very Turkish in their grime and sloth. The people were just a mob in deshabille. All the men seemed half-dressed; all the women were shrouded as though to hide how negligent they had been before their mirrors. The air was cracked with angry shouts, hucksters in the way, mules which would not get out of the way. There was the shrill cry of the vendor of iced lemonade. The glare and the uproar were blinding and deafening.

A wheel to one side and we were in a caravansery. Memory of Haroun al Raschid! - here was the real East. A great yard walled with high buildings, brightly painted, and with arched balconies. The slim limbs of trees spread wide branches, so the pavement was fretted with a mosaic of lights and shadows. In the middle was a fountain of marble, cracked and smeared, but the splash of water in a sunray was coolness itself. On a little platform squatted dignified Turks, their beards henna-dyed, their cloaks falling loose and easy, their turbans snowy-white - save one which was green, indicating a haji who had made the pilgrimage to Mecca. They all puffed slowly, sedately, meditatively, at their narghiles. Here was no vulgar hustle; here was only repose.

Next to the long, dimly-lit tunnels with shops on either side, called bazaars. It was all weird and garish and un-European. Then a look at the wares. That crockery was from Austria; all these iron articles were German; the cheap jewellery was from France; the flaming cottons were from Lancashire; the gramophones shrieking "Ya-ya-ye-a

![]()

113

ah-ah-ah!" to attract, came from America. Nothing was Turkish save the dirt.

The population is a medley of Turk, Greek, Jew, and Armenian. But all the trading, the commerce, and the banking is in the hands of foreigners. The Turk is hopeless as a business man.

Yet an old-time veneration rests upon Adrianople. Its story goes back to the time of Antinous. It was rebuilt by the Emperor Hadrian. In the fourth century Constantine defeated Licinius out on the plains, and half a century later Valens was defeated by the Goths. But the walls of the city were so strong that they did not capture it. A thousand years later it fell into the hands of the Turks, and it was their capital before Constantinople became the centre of Ottoman rule. Another five centuries, and the Russians, without opposition, marched into Adrianople and compelled the Turks to recognise the independence of Greece. It rose, it became mighty; it has fallen from its great estate.

Solemn is the mosque of the Sultan Selim, rearing its four stately minarets. Beautiful is the minaret of Bourmali Jami, spiral in white marble and red granite. Highest of all is the minaret of Utch Sherifely, with three balconies, where, at the fall of the sun, flushing Adrianople with radiance, stand the priests and cry, echoingly, pathetically, over the tumult of the city: "There is only one God, and Mahomet is His Prophet. Come, all who are faithful, and pray!"

The Turks hate the Christians; the Christians hate each other; the Jew hates both.

![]()

114

I was in Adrianople during the great fire of September, 1905, when sixty thousand persons were rendered homeless. It broke out in the Armenian quarter. "The Turks have done this, or the Jews, who else?" shrieked the Armenians. Armenians all over Turkey believed it was the diabolical act of their enemies. They could not be persuaded to believe anything else. As a matter of fact, the origin of the fire was most ordinary - the upsetting of a lamp. Half a dozen Christian women were taken ill in a narrow street near the British Consulate. "Ah, sir," yelled an Armenian of whom I saw much, "there you have proof of how wicked those devils the Turks are. They poisoned the well." "Yes," I said, "but the well is used by Moslem women, and how is it none of them were poisoned?" The Armenian did not know; but he was not going to sacrifice the conviction that the Turks were the cause of the poisoning of Christians. Everything that happens in Adrianople is ascribed to the religious hatred of somebody else.

Adrianople is a city of terror. Christians, Armenians, whispered into my ear tales of revenge on the cruel Turks. But they did not take place. The Turks were in constant fear of outrages, bombs and the like, from Bulgarians or Armenians. At sundown every Christian must be within doors. Otherwise there is arrest and imprisonment. No light must be burning in a Christian house three hours after sundown, or the soldiers butt the door with their rifles, demand reasons, and under threats

![]()

115

levy blackmail; no Mahommedan can go through the streets after dark without a lantern; no Mahommedan must even be in the streets after ten o'clock without a special permit. The only sound at night is the heavy tread of the patrol.

When the city is wrapped in dark it is like a place in siege. One night I dined at the Austrian Consulate. The table was spread in the little courtyard; the surroundings of the old Turkish house, - the drip of the fountain, the gleam of the moon, gave a touch of romance. The hours sped merrily. But when I was ready to go I found six Turkish soldiers waiting in the porch to be my escort back to the British Consulate. I felt like a prisoner.

One afternoon I accompanied an Armenian to his vineyard on the slopes beyond the city. There, in the cool of the day, we plucked and ate many grapes. The topic of conversation was the savagery of the Turks. I was told of how, a week or two before, several soldiers outraged a Greek woman working in the vineyard. "Didn't you interfere?" I asked. "Interfere! Ah, sir, you do not understand. I would have been beaten to death." "Then did you complain to the authorities?" "What was the good? I am an Armenian. I would have been told, 'You are a liar.' That is all." "Well, but suppose I caught soldiers committing an outrage and I pulled my revolver and shot them dead, what would happen to me?" "Nothing. You are from England. You have your Consul, your Ambassador at Constantinople.

![]()

116

The Turks would hush it all up. You would not even be arrested."

Night had just closed as we got back to the city. My Armenian acquaintance,

who was wearing the fez, was stopped by a soldier at a small bridge. "Why

do you come in the dark?" asked the soldier, raising his rifle. "I have

been to my vineyard," was the reply. "You are a dog," said the soldier,

"and I will shoot you." I am with the efendi," said the Armenian,

turning to me. My clothes and particularly my slouch felt hat proclaimed

I was European. The soldier sulked and let us pass. "Would he have shot

you?" I asked. "No; but I should have been compelled to pay him money,

or he would have arrested me for being out after dark. He would have fired

if I had tried to get away." "And why didn't he make you pay?" "He saw

your hat. You are a European. The Turks are frightened. In your travels

in Turkey never wear the fez; better than an escort will be your hat; always

wear it." And I always did.

It was the crack of dawn, and far off was the roll of drums and the heavy, melancholy Turkish music leading troops at quick march. With rattle and rip and the sodden slip-slouch of innumerable feet, soldiers were being marched into Adrianople. This was the anniversary of the accession of Abdul Hamid to the throne of the Caliphate.

The troops massed before the Konak, the official residence of the Vali, the Viceroy. In the grey of the new day there was something weird in the as-

![]()

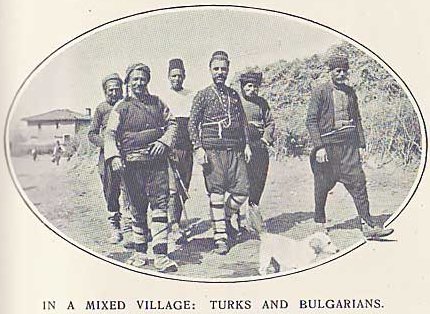

IN A MIXED VILLAGE: TURKS AND BULGARIANS.

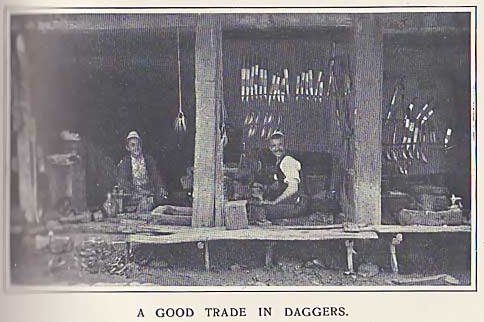

A GOOD TRADE IN DAGGERS.

![]()

117

semblage, the dark blue uniforms, the swarthy faces, the red fezzes. The officers were gay with orders on their breasts. There was the fluttering of the blood-hued flag and crescent; here and there hung the green holy flag. The Vali stood on a balcony. For a moment there was a pause. Then the regimental bands played a stave, minor and sonorous, like the beginning of a noble anthem, and when the brass instruments ceased, the warrior concourse raised the shout, "Patishahim tchok Yacha!" ("Live long the Sultan!"). The effect was magnificent. The band skirled into cheerful banging.

The main streets were decorated - by order. Innumerable pennants fluttered. The red and the green crescent flags waved smartly. There were triumphal arches. The whole thing was rather tinsel - but these things always are.

Where was the cheering populace? There was no cheering. As for the populace, all windows and doors were closed, and those who wanted to see the Vali were forced up side streets and bullied by the soldiers. With the dragoman from the British Consulate as my kindly guide, and the kavass as my protector, I had free passage. Truly I was an individual of importance! Every soldier jumped to the salute as I passed. But such a demonstration, instead of giving me satisfaction, made me feel supremely ridiculous. I wanted to laugh. Only twice before had I ever felt the same sensation: when as a boy I walked on to a, platform to receive a book prize for good conduct, and when I walked

![]()

118

up the aisle of a church to get married. Yet though there was prohibition against peeping, it was easy to catch a glimpse of women behind the casements, whilst on a broad mosque wall were huddled a hundred shrouded creatures, like awkward bundles with eyes.

The Vali was about to open an exhibition of Adrianople products. Turkey had got so far on the road to progress as to have an exhibition. And this was the first exhibition ever held in Turkey. It seemed a sort of miniature Earl's Court. The chief article on sale was cigarettes. The real Turkish damsels who sold them were quite as persistent as the imitation Turkish damsels at West Kensington. The girls were Christian Turks, and their faces were uncovered. Old and fat Turks hung round and leered. There was tobacco in all stages of preparation. There were some very bad pictures. There were passable local woollen goods, and much excellent embroidery. There were farming implements, but these were imported.

The place was a swelter of officials, and they were all very fat; all wore gold and silver lace in abundance, and had broad sashes and orders which jostled one another. The greetings were effusive. The salaam is deep; then there is a wave of the right hand to the ground, to the waistcoat, up to the forehead, indicating that feet, heart, head, boots, waistcoat, and fez are yours. When you enter a room everybody does this to you, and you proceed to do it separately to every individual. So in a gathering assembly there is no time for any-

![]()

119

thing but salaaming. I recognised my incompetence to go through the ceremonial towards thirty stout old Turkish gentlemen. I was coward enough to shelter myself behind my nationality. I bowed and shook hands with the one or two that were nearest. After a stately procession we all went into the garden, listened to the band, and ate indifferent ices.

I was settling down to a cosy siesta when rat-tat at the door of the Consulate. A Turkish general in gorgeous garb had arrived. We salaamed. He spoke English, for had he not been attache at Washington years ago? He brought a message. His master, the Vali, Mahomet Arif Pasha, sent his compliments, and would I honour him with a visit in his garden at nine o'clock? Nine o'clock struck me as an extraordinary hour to meet a gentleman in a garden. But then I recollected that nine o'clock Turkish is about four o'clock European.

Oh, the Turkish time! The day begins with sunrise. That is twelve o'clock. But the sun does not rise at the same time every day in Turkey any more than in other places. So the Turk - who happily has much spare time - is constantly twiddling the lever of his cheap Austrian watch to keep it right. It may be the best time-keeper in the world, but the more accurate it is the less does it keep proper time in Turkey. Indeed, a watch that is somewhat vagrant in its moods is more likely to be correct. The consequence is that nobody is ever sure of the time. There or thereabouts is suffici-

![]()

120

ently good for the Turk. The very fact that the Turks are satisfied with a method of recording time which cannot be sure unless all watches are changed every day, shows how they have missed one of the essentials of what we call civilisation.

It was the most radiant crimson-cushioned carriage I could hire in Adrianople in which I rode out, with the Consulate dragoman and my interpreter, to visit the Vali. The garden of the Viceroy is beyond the city. All the country was withered and parched brown; the road was deep in dust; the air panted hot and oven-like. Past the guards. The trees were tall, weedy, and choked with dust. No lawns, but rough tangled ground and tufts of rank grass. (Let Englishmen offer an occasional prayer of thanks for our English lawns, the like of which are not elsewhere in this world.)

Within the shadow of a pretty kiosk, on the shelf of a plantation, and overlooking a tawny little river with parched plain beyond, sat the Vali, surrounded by his staff. He was the least radiant of the throng. A stout, full-faced, lethargic man. His eyes were drowsy, and he talked slowly. Only two small orders did he wear on his breast, whilst the coat fronts of the men about him were dazzling with them.

The first minute or two of conversation was stiff and formal. Then I got a peep of Turkish methods. The Vali knew about me; he knew when I had arrived, where I dined last night; that my interpreter had been sent from Constantinople by Sir

![]()

121

Nicholas O'Conor. I had been watched. The Vali was interested in England, and was anxious to know the difference between the House of Lords and the House of Commons. "Your Excellency should come to England," I said. "Ah," he replied, with a sigh, "I would give that which I wear on my head to visit Europe, but" and he shrugged his shoulders.

Yes, like many another Turk, he would sacrifice his fez, the emblem of his nationality, to get away. High was his position, with an authority only less than that of the Sultan himself. But he was a gilded prisoner, sent by his imperial master to Adrianople, fifteen years before, there to rule, but surrounded by spies. Never, during all those fifteen years, had he been allowed to visit Constantinople, never even to get beyond the sight of Adrianople. He was a sad man.

We talked of many things. Now and then a general or a colonel was signalled to step forward and join in the conversation; but at the first opportunity they stepped back again. In the near wood a band was playing; and all the time refreshments were being provided: cigarettes and coffee, cigarettes and ice cream, cigarettes and caramels, cigarettes and grapes, and then more cigarettes.

At the end of an hour I mentioned what had been in my mind. I wished to travel in the interior. Did his Excellency think it safe? "By the might of the Sultan all the land is tranquil," said the Vali - "which means there are massacres somewhere," was whispered by my interpreter. I made a

![]()

122

courtesy speech on my delight at visiting Adrianople. "Who drinks of the waters of Adrianople visits it seven times," said the Vali. "Then I look forward with delight to my next six visits," I replied.

Bows; salaams; the band plays, and off I go back to Adrianople in a

swelter of dust.

[Previous] [Next]

[Back to Index]